Abstract

Three approaches have characterized the study of news translation, but none have given a satisfactory account of the role of culture. The first, drawn from political economy, asks how and where news travels. The second, from linguistics, asks how journalists deal with lexical or stylistic concerns. The third, from sociology and cultural studies, asks how journalists understand their role in society. All three, however, employ terms such as ‘culture’, not to mention ‘news’ and ‘translation’, differently. This article proposes an approach grounded in a materialist philosophy of language that clarifies the relationship between political economy, linguistics, and sociology/cultural studies, by locating culture in the tension between the political economic world of exchange and negotiation, the social world of shared meaning, and the subjective world of individual expression.

Introduction: culture and news translation

What is the role of culture in news translation? I ask the question simply, but it is not a simple question. ‘Culture’, as Williams (Citation1983) famously observed, is one of the most complicated words in the English language. ‘News’ raises questions of genre – are we concerned with hard news? Soft news or human-interest stories? Analysis of current events? Opinion? ‘Translation’ is no better. Often with news translation, there is no source text, as we have long understood the concept. So what exactly is translated?

In the past four decades, I contend, three approaches have characterized the study of news translation. Each responds to a different set of questions, and each relies on different ideas about culture, news, and translation. The political economic approach, as I see it, asks how and where news travels. The linguistic approach asks how journalists handle lexical or stylistic concerns. And the cultural studies or sociological approach asks how journalists understand their role in society.

But they are like the blind men describing parts of the same elephant. What I want to do here is try to describe the elephant itself, at least from one angle.Footnote1 (We cannot see metaphorical elephants from all angles at once any more than real elephants!) Of course, the study of news translation has matured to the point that there have been other attempts to do this. For instance, van Doorslaer (Citation2010a, Citation2010b) asserts that our interest in news has extended the possibilities of the modes and degrees of translation by moving beyond commonsense notions of interlinguistic transfer and troubling notions of source and target texts. Schäffner (Citation2012), for her part, asks whether we need new concepts (such as ‘transediting’) to describe the work journalists do, or whether ‘translation’ already encompasses the editorial roles they play.

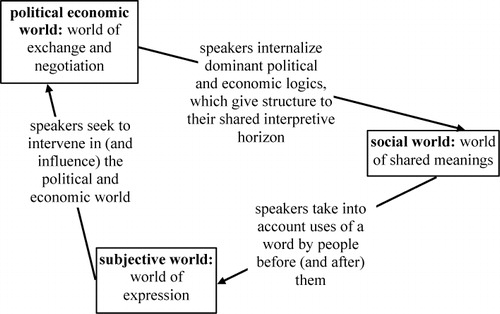

In contrast to them, I focus squarely on culture. I contend that an approach drawn from materialist philosophies of language, such as in Vološinov’s (Citation1929/Citation1986) Marxism and the Philosophy of Language, offers a necessary perspective by describing the dynamic system in which the other approaches take part. This approach begins with three assumptions: (1) The political and economic worlds give structure to the social. (2) The social world gives structure to our subjective worlds. (3) As acting subjects, we shape the economic, political, and social worlds. We find culture – the set of shared assumptions that structure how members of a community make sense of the world – in the tension between the political economic, social, and subjective worlds. The three approaches that have characterized news translation research all reveal different facets of this tension. If they are a leg, trunk, and tail, then a materialist approach reveals how they fit together to produce an elephant.

The three approaches

If we want to examine news translation research, what do the three approaches – from political economy, linguistics, and sociology and cultural studies – reveal? describes the questions each can answer, as well as the notions of culture, news, and translation they employ.Footnote2

Table 1. Three approaches to news translation and their respective meanings of ‘culture’, ‘news’, and ‘translation’.

But this table requires two preliminary notes. First, it puts approaches in distinct boxes and appears to suggest the lines between them are clear. In that respect, it is misleading. Instead, it is a view from above – a conceptual map – and it makes the compromise every map makes: it reveals broad patterns, but it sacrifices fine-grain details. I follow Carey (Citation1988) here when he says, ‘the purpose of representation is to express not the possible complexity of things but their simplicity’ (p. 28). I am imposing distinctions that scholars do not respect in practice (why should they?); my point is not to classify individual works as such but the ideas that underpin them. In other words, these distinctions are heuristic. The studies I cite use these ideas, but few fall exclusively into one category. Furthermore, these categories are not internally consistent. Recent work (e.g., Bielsa & Bassnett, Citation2009) frequently stands in dialectical tension with earlier work; sometimes it even draws the very premises of the approach upon which it builds into question.

Second, this table describes what has been done, not what could be done. Countless approaches remain unexplored. In the area of linguistics, for instance, we could ask how journalists negotiate relationships of power by observing their language use at a discursive or pragmatic level, rather than a syntactic level, thus linking concerns of linguistics with those of political economy. But what I present here is a more modest description of the state of the question.

Although researchers only rarely define the basic terms that interest us here, they still use them in predictable ways. ‘Culture’, to begin, tends to mean one of three things: (1) the set of shared, unspoken assumptions that structure how a community makes sense of the world, (2) the artifacts that a community invests with meaning, where those assumptions become manifest, and (3) the community itself. The first sense is the most abstract, but a visual metaphor, that of an ‘interpretive horizon’, helps clarify what I mean. In our visual field, we do not always see the horizon, but it is nonetheless the background against which objects become distinct. In the same way, the unspoken assumptions shared by a community go largely unnoticed, but it is against them that objects become meaningful. Television scholar Collins (Citation1990) calls this idea of culture ‘anthropological culture’, and he calls the second idea ‘symbolic culture’ (p. 35), a shorthand I adopt here, with the addition of ‘culture as community’ to describe the third.

‘News’, as I suggest above, tends to refer to a range of texts broken down by genre: informative news (or ‘hard news’) is intended to be factual and perspective-free; human interest (or ‘soft news’) focuses not on events but their effects on individuals; analysis interprets events by putting them in context; and opinion makes a case for one course of action over another.Footnote3 Finally, ‘translation’, at one end of the spectrum, describes linguistic re-expression or, at the other end, interpretation and adaptation to meet the expectations of readers, listeners, or viewers.

Political economy

The best-established approach is that of political economy, which is concerned with the flow of news. It continues a long tradition in communication studies of asking how events become stories and how stories move from one place to another (e.g., Boyd-Barrett, Citation1980; Dahlgren & Chakrapani, Citation1982; see Bielsa & Bassnett, Citation2009, for an overview).

Much of the early work on news translation focused on news agencies such as the Associated Press (based in the United States), Reuters (based in Britain), and Kyodo (based in Japan) (Chu, Citation1985; Henningham, Citation1979; Lee-Reoma, Citation1978). Researchers began by looking at informative stories translated either partially or, more rarely, in their entirety. They asked how the political relationships between the countries where agencies were based and those where events took place influenced which stories the agencies offered to subscribers (and which ones subscribers published). They performed their research during the time when UNESCO’s International Commission for the Study of Communication Problems (Citation1980) was preparing its report (commonly known as the MacBride report, in reference to the commission’s chair, Sean MacBride). It investigated the concern that ‘certain powerful and technologically advanced States’ – namely the United States and the countries of western Europe – ‘exploit their advantages to exercise a form of cultural and ideological domination which jeopardizes the national identity of other countries’ (International Commission for the Study of Communication Problems, Citation1980, p. 37). Communication research in the 1980s appeared to confirm this fear, as did research into news translation. Scholars concluded that military power and economic dominance allowed powerful countries to consolidate their political influence, which in turn allowed them to build their economies and militaries. This relationship shaped the flow of news and introduced distortions into the translation process.

Of course, scholars did not limit themselves to a macro-level view. They also examined news flows by looking at how specific people, especially editors, acted as gatekeepers. Akio Fujii (Citation1988) noted that Japanese journalists did more than choose which stories are published or not; they also transformed texts by shortening them or by making assumptions explicit when they were unlikely to be shared by the readers of the translated text.Footnote4 Similarly, Wilke and Rosenberger (Citation1994) focused on the ‘slotters’ in German service of the Associated Press who screened articles, passed them on to writers, and then reviewed them again before they were sent out for distribution.

More recent work on news agencies continues in this vein but brings a more sophisticated set of tools to bear on the effects of distribution on content. The most sustained study is that of Bielsa and Bassnett (Citation2009) in Translation in Global News, which examines news flows while exceeding political economy’s historical bounds. They argue that translation’s role in globalization has been overlooked and that it is in fact ‘central for an understanding of the material conditions that make possible global connectedness […]’ (p. 18). With respect to news, they write:

the news editor has the specific skills required for the elaboration of such translations, and that the organization of the news agency has been conceived in order to facilitate communication flows between different linguistic communities so as to reach global publics with maximum speed and efficiency. (p. 58)

An integral part of this facilitation is the localization process, and at the heart of localization is a consideration for a community’s shared process of meaning-making. In other words, with Bielsa and Bassnett (Citation2009), the political economic approach has arrived at the question of anthropological culture, in contrast to its early years, when its practitioners used ‘culture’ to describe a community but made an abstraction of the beliefs they shared. Early research, such as what followed the MacBride report, reflected a fear that media from more powerful countries caused communities in poorer countries to become like the United States or the West. Scholars treated media flows from wealthy to poorer countries as a form of cultural imperialism, but they stopped short of examining the actual beliefs of the people consuming the media.

Linguistics

A more recent approach drawn from linguistics expands the range of definitions of ‘culture’, but it is not as well developed as the political economic approach. Here, scholars ask about journalists’ lexical choices when translating stories.

Articles that compare an original story with its translation exist (e.g. Abdel-Hafiz, Citation2002), but they are relatively rare because such source-target pairs are rare: journalists are more likely to draw from multiple sources than translate stories in their entirety (van Doorslaer, Citation2010a). Instead, this approach is more concerned with the strategies journalists adopt when they create new texts: they make additions or deletions, they make details explicit or more general, they substitute one reference for another, and so on (Bani, Citation2006). When researchers do focus on word choice, they ask questions such as how languages that lack explicit lexical cues to mark complimentary or derogatory usage (such as English) translate those that have them (such as Chinese) (Sorby, Citation2006). Or they examine political metaphors and the connotations they carry, such as the racial designations ‘black’ and ‘white’ in English and their equivalents in Turkish (Bulut, Citation2012). In this micro-level analysis, where the focus is on journalists’ choices, ‘culture’ tends to describe both communities and the interpretive horizon they share. Journalists are concerned with the communities they are addressing, but researchers go further. Ideas about what is complimentary or derogatory are rooted in the values people share, which form part of their horizon. Similarly, political metaphors resonate differently in contexts where the assumptions people make about the world diverge.

Macro-level linguistic research is more rare. It has been pursued most productively by McLaughlin (Citation2011), who uses corpus analysis to ask not about journalists’ choices as such, but about the effects of their choices on the languages into which they translate. In Syntactic Borrowing in Contemporary French, she examines a corpus of news stories to ask how English syntax is influencing French, but she touches only tangentially on questions of culture. More useful here is her study of English loan-words in French news, where linguistic change becomes an index of cultural change, which is to say, where new words indicate a change in the receiving community’s interpretive horizon. She points, for example, to the use of ‘proactive’ in French to argue that

The translation of international news could contribute to the circulation of both the term […] and the ideological positioning that accompanies it: its rhetorical function […] is to make it very difficult for the EU [described as ‘proactive’ in the example she gives] to respond negatively because of the value currently associated with proactive policies. (McLaughlin, Citation2015)

Thus the use of ‘culture’ here diverges from the uses above. In those examples, journalists took the interpretive horizon of their community of readers into account when choosing one word over another. Here, the concern is less with the choice itself than its effect on that community. In fact, we might take this a step further: what happens when there is no choice to make, such as when journalists report on political agreements between different linguistic communities, where official translations of key terms are already established? Do such lexical pairs circulate differently in each community, evoking different meanings in each context? With questions such as this, we come to sociological and cultural studies approaches to news translation.

Sociology and cultural studies

The approaches I group together here are all concerned with social influences on journalists and, in some cases, the influence of news on society. Some adopt methods drawn from sociology, such as participant observation (e.g. Davier, Citation2014), while some rely more heavily on carefully situated textual analysis (e.g. Conway, Citation2011). They all draw on a wider range of notions of culture, news, and translation than what I describe above.

At a micro-level, that of the journalist in the newsroom, these approaches ask what it is exactly that journalists do to produce what scholars call ‘news translation’. How do they understand their roles in the newsroom? In one widely cited paper, Stetting (Citation1989) notes similarities between what editors and translators do, especially those who deal with practical texts as opposed to cultural texts. Both write with their audience in mind and perform acts of ‘transediting’ to ‘improve clarity, relevance, and adherence to the conventions of the textual type in question’ (p. 372). The role of the transeditor is that of a ‘“midwife” [who sees] to it that the original intentions are reborn in a new and better shape in the target language’ (p. 376). The idea is popular among news translation scholars because it captures the messiness of the process, but as Schäffner (Citation2012), argues, ‘transediting’ is most useful when it draws our attention to the way translation and editing are intertwined – most translation studies scholars already recognize editing as part of the translation process. At this micro-level, scholars have a secondary focus, too. What effect, they ask, do audiences’ expectations of journalists – and journalists’ expectations of themselves – have on the visibility of the translation process? How, if at all, do they draw attention to the fact that something they write or say was originally expressed in another language (Conway, Citation2011; Gagnon, Citation2012)? Do the agencies they work for even recognize translation as part of their work, or is it invisible there, too (Davier, Citation2014)? ‘Culture’ in these micro-level examples refers both to a community’s interpretive horizon and the community itself. Transediting is a form of localization (see Pym, Citation2004), and its practitioners create texts that respond to target communities’ cultural expectations, in the anthropological sense of the word.

Finally, a macro-level sociological or cultural studies approach expands these categories still further. Cultural studies is grounded in ideas derived from Marx, as can be seen in the analytical models proposed by Hall (Citation1980) and D’Acci (Citation2004), and it examines the dynamic relationship between political actors, journalists, and the public as they negotiate questions of identity and shared meaning. This approach treats translation as a type of mediation or negotiation that goes beyond the rewriting of texts. When journalists explain to their audiences how another community sees the world, they make editorial choices, as the other approaches demonstrate, but they also take an active role in the tug-and-pull over what words mean. Thus, whereas political economy and linguistics look mostly at informative news stories, cultural studies also looks at human interest stories and editorials, whose authors try to persuade rather than merely inform. More so than other approaches, cultural studies takes interest in symbolic culture by asking how members of a given community come to invest meaning in the objects (or texts) they circulate among themselves. How do journalists decide when they should inform, explain, or persuade? What forces privilege certain meanings over others?

This approach gives insight into complex situations of intercultural contact, such as the debates in Canada in the 1990s about the constitution and the place of the French-speaking province of Quebec. Canada’s leaders negotiated a series of accords that would have recognized Quebec as a ‘distinct society’ or ‘société distincte’, but the terms circulated in such a way that they evoked different ideas for Anglophones and Francophones. Journalists on the national broadcaster performed paradoxical acts of translation, in the broad sense of the word: they tried to explain how each linguistic group saw the accords, but they ended up confirming viewers’ pre-existing assumptions rather than challenging them (Conway, Citation2011). This approach can also address non-verbal symbols. To give one example, journalists in Spain have tried to explain what the niqab or Muslim face veil means (Vaskivska, Conway, & Shafer, Citation2013), a form of intersemiotic translation (Jakobson, Citation1959/Citation2004) where the meaning of the object in question is rooted in people’s shared sense of identity.

Thus, these three approaches use ‘culture’, ‘news’, and ‘translation’ to describe a set of overlapping, occasionally contradictory ideas. To answer the question that I pose in the introduction, we must take a step back to see the relationships from which the competing senses of these words derive.

The philosophical foundations of a materialist approach

Underlying the questions I have posed about news translation is a vexing puzzle, which a materialist approach to the philosophy of language helps unravel. What is the status of something – language in a narrow sense, meaning-making in a broader sense – that is both private and shared? Here I consider people associated with the Bakhtin Circle, including Mikhail Bakhtin and his associate Valentin Vološinov,Footnote5 and their philosophy of language. I clarify the materialist roots of their thought by bringing it back to Marx, and I expand it to translation by linking it to the critical and hermeneutic work of Walter Benjamin and Paul de Man.

In Marxism and the Philosophy of Language, Vološinov (Citation1929/Citation1986) contends that as subjects who act within and through language, we know the world only through a founding act of symbolic violence, the imposition of order upon a world in flux. That is, we see the world as ordered, where we can distinguish one object from the next because they belong to different categories. But these categories are not a natural product of the world; instead, they are a convention arrived at and maintained by the communities to which we belong.

So we might think language is something we own, a means of self-expression or of bringing out our interior worlds. But the words by which we come to know the world are above all social. When we speak, we must respond to people who spoke before us. We take their words – where and when they used them, the ends to which they put them – into account (Vološinov, Citation1929/Citation1986). They are others’ words that we try to make our own, but our need to tame them reveals their stubborn foreignness. We also anticipate how others will respond to us, and we try to preempt their objections:

When constructing my utterance, I try actively to determine this response. Moreover, I try to act in accordance with the response I anticipate, so this anticipated response, in turn, exerts an active influence on my utterance (I parry objections that I foresee, I make all kinds of provisos, and so forth). (Bakhtin, Citation1986, p. 95)

We always use words of the other, but we in turn become the other’s other.

Through this ongoing process of account-taking, of keeping past uses of a word in mind, words acquire something akin to memory. Over time, certain uses become more frequent. They become regular, even expected. They map out a structure of associations shared by a community of speakers, which form their interpretive horizon: to make sense of an object or event, they read it in the context of those associations. To talk about these associations, Benjamin (Citation1923/Citation1997) speaks of ‘intention’:

it is necessary to distinguish, within intention, the intended object from the mode of its intention. In ‘Brot’ and ‘pain’ the intended object is the same, but the mode of intention differs. It is because of their modes of intention that the two words signify something different to a German or a Frenchman, that they are not regarded as interchangeable, and in fact ultimately seek to exclude one another […]. (pp. 156–157)

De Man (Citation1986) explains Benjamin’s assertion by observing that translation reveals ‘a fundamental discrepancy between the intent to name Brot and the word Brot in its materiality, as a device of meaning’ (p. 87). Again, what is at stake here is the connotative or associative level of meaning. Brot makes de Man think of Friedrich Hölderlin (who figures prominently in Benjamin’s essay) and his elegy to Demeter and Dionysus, ‘Brot und Wein’. But in French, pain et vin is something trivial, not weighty: it ‘is what you get for free in […] a cheap restaurant where it is still included, so pain et vin has very different connotations from Brot und Wein. It brings to mind the pain français, baguette, ficelle, bâtard, all those things’ (p. 87). We might intend one thing when we say a word, but the word, because of its socially arrived at associations, always intends more.Footnote6

The idea that the social takes primacy over the subjective is part of what makes my approach materialist. It is one of the three assumptions upon which the approach is based, as I write in the introduction. The others are that the political and economic take primacy over the social and that as subjects, we can influence the political and economic. maps these relationships.

This schema derives, of course, from Marx’s dialectical materialism, but it does not follow Marx in presupposing an end-point at which the dialectic will arrive. We need not assume that the contradictions between the political economic, social, and subjective worlds will resolve themselves in some sort of workers’ utopia – it is enough to see that the structures that shape our subjective experience come from outside ourselves. Consider the political economic world, that of negotiation and exchange. Capital gives people the ability to influence political decisions. That ability grows stronger when the logic of capital comes to appear as common sense and people see it as part of the natural way of things. In that way, capital comes to shape the social world, that of shared meanings. In the realm of news translation, we see this effect in the treatment of news as a commodity: journalists know their stories must sell newspapers or attract viewers, and to do that, they must appeal to audiences’ commonsense ideas about the world.

But the political economic world does not determine the social world as, say, one might program a computer. Nor does the social world determine the subjective world. As Marx (Citation1852/Citation1994) says in the Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, as acting subjects, we make history, but not in conditions of our own making. Similarly, where language (as part of a broader interpretive system) is concerned, we intervene in the political economic world. We also seek to change the social world, both directly, through our strategic use of language, and indirectly, through our efforts to influence politics and economics. In this way, meaning is open to negotiation. Because it is shared, it remains relatively stable, but we can try to change others’ minds through persuasion or through broader processes of structural change that reconfigure the assumptions that form our interpretive horizon.

A materialist approach to culture and news translation

Let us return to the question that opens this essay. If we adopt this materialist approach, what is the role of culture in news translation? ‘Culture’, through this lens, is to be found in the tension between the political economic, social, and subjective worlds that makes language (and other sign systems) both private and shared. Anthropological culture, symbolic culture, and culture as community are all categories produced by this tension. Culture as community takes analytical precedence over the other forms, for which it is the logical precondition: without a community of speakers, we have no one to address or respond to. Or, from a temporal point of view, we are all born into a community of speakers with a history of exchanges – the ones we come to account for as we learn to speak – that predate us. Symbolic culture, of which the news is one example, is the means by which a community produces and maintains its interpretive horizon. None of this is to say that communities are monolithic, or that the boundaries people draw between them are fixed. They are relatively stable, but contact between communities (for instance, when journalists from one report about members of another) can lead to change in people’s perception of who belongs or who does not.

News, then, is part of symbolic culture, an artifact that a community invests with meaning. It is also an utterance, a turn taken in the ongoing conversation that shapes the relationship between the social and subjective worlds. Admittedly, it is a complex turn, one that encompasses conversations of its own (for instance, between reporters and the people they interview), but it is marked by ‘an absolute beginning and an absolute end: its beginning is preceded by the utterances of others, and its end is followed by the responsive utterances of others’ (Bakhtin, Citation1986, p. 71).

Genre is a set of conventions shaping news as an utterance, a tacit agreement between journalists and audiences about how form should relate to content.Footnote7 Ideas about whether a story should be informative, for instance, come from their shared expectations about the role news should play in society (should it be balanced?) and how it should play that role (has the reporter spoken to ‘both sides’?). They expect opinion in some places (such as a newspaper’s editorial page) but not others (the front page, at least in US news). Those expectations shape how journalists take into account the words of others – stories by other journalists, political debates about the topic at hand, etc. – as they anticipate responses and try to elicit agreement or head off accusations of bias.

Finally, translation, as seen through this materialist lens, is a mode of account-taking, one that involves members of different cultural communities. When journalists decide how to render speech in another language (where ‘speech’ ranges from individual statements to entire stories), they take into consideration two sets of assumptions, those that shape how the speech circulated in the community where it originated, and those that are likely to shape it in the community that includes their audience. They assess the situation in each community as they work within the conventions of genre. Their decision-making process – what others have described as gatekeeping and transediting – involves a range of contingencies, and they make decisions based on a complex mix of professional training and intuition.

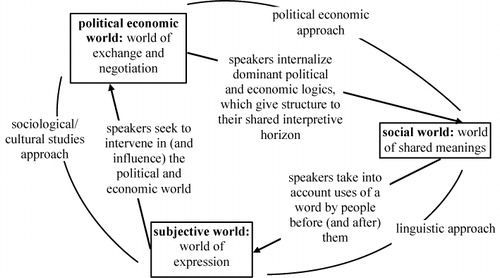

We can also reread previous research through this materialist lens. We can map the three approaches onto the materialist approach, as I describe in . What distinguishes one from another is where they put their emphasis. The political economic approach focuses – not surprisingly – on the political economic world, that of exchange and negotiation. Or, to be more precise, in its concern for news flows and gatekeeping, it focuses on the influence of the world of exchange on that of shared meanings. The political and economic logics that shape audiences’ interpretive horizons also shape journalists’ perceptions of what is important. Moreover, they shape audiences’ priorities and journalists’ impressions of what audiences want, and when journalists make choices about what to cover, they influence the range of ideas to which audiences are exposed.

The linguistic approach, in its focus on word choice and broader lexical change, shifts attention to the influence of the social world on the subjective world. One important influence on word choice is journalists’ assessment of how a word in one language has been used and how its translation in another is likely to be received. We can see the result of journalists’ assessment of single words or phrases by looking at specific word choices, and we can see the impact of their collective assessments over time in the results revealed by corpus analysis.

Finally, the sociological or cultural studies approach, especially in its macro-level analyses of social change, asks about the effect of the subjective world on the political and economic world. It is concerned with different actors’ efforts to influence the broader relationships between themselves and people they perceive as ‘other’. These relationships are inherently political, both in a narrow sense (when they reflect different states’ dealings with each other) and in a broad sense (when they reflect efforts by members of a community to shape how their compatriots interact with cultural ‘others’).

The value of the materialist approach is that it draws attention to aspects previous approaches had not examined. For instance, even if a linguistic analysis focuses on the social and subjective worlds (as suggests), it cannot make a complete abstraction of the political economic world: one way subjects influence the social world is by intervening in the world of politics and economy. Likewise, a political economic analysis cannot ignore the subjective world: the meanings shared in the social world find expression in subjects’ words and actions, which form the raw materials for the world of politics and economy.

The materialist approach also brings to light the limitations of news translation as a form of intercultural communication. Words and their translations circulate differently in their respective communities, and as a result, the past uses speakers take into account differ, too. What is at stake is what Benjamin called ‘intention’ above. Uses accumulate in the minds of speakers, so that words evoke more than a referent in the world: they also evoke other words by association, which in turn evoke still others, and so on. When journalists try to explain one community to another, there is a limit to what they can achieve because of the difference in each word’s intention. They may try to explain what an object or event means for a community their audiences find foreign, but they cannot capture this play of associations – this movement from word to word – in any exhaustive way. Their explanations are always necessarily partial (Conway, Citation2010).

Conclusion: implications of culture in news translation

One value of the materialist approach I am proposing is that it gives us new tools to examine certain truisms about news translation. For instance, the idea that journalists tailor their translations, such as they are, to their audiences has been well established. The approach I have proposed should cause us to ask about audiences themselves. What do they make of news translation? Do they recognize when translation in its various forms takes place? Does exposure to other points of view prompt them to examine their own assumptions about the world, or do journalists’ efforts to localize news result in stories where what was foreign becomes indistinguishable from what audiences already know?

In this way, a materialist approach opens new avenues of investigation. It provides a dynamic model for examining the role news translation plays in intercultural contact. On one hand, news translation holds the potential to introduce new ideas into a community’s collective discourse by giving speakers new uses of words they must take into account. On the other, it also holds the opposite potential: audiences might find new ideas so foreign that the ideas cause them to affirm that what they have always believed is still true. Of course, news translation does not exist in a vacuum: people are exposed to cultural ‘others’ through a range of media, including drama and comedy, in addition to news (not to mention interpersonal contact). A materialist approach draws our attention to the dynamic relationships between these media and the various worlds where they are produced and consumed.

In the introduction, I made two points to which I now want to return. First, I said the question of culture in news translation is not simple. Part of its complexity came from the fact that key terms have often gone unexamined. I hope now that I have begun to sort them out by identifying researchers’ unspoken assumptions and by showing how uses in the context of previous approaches are symptomatic of a broader tension between politics, economics, society, and individuals. The way we make meaning of the world is complex, and consequently, so is the way journalists go about explaining how cultural ‘others’ are like us or not. In my experience, journalists have an earnest desire to serve their audiences, and a materialist approach to news translation gives us another set of tools to evaluate how well they succeed.

Second, with respect to metaphor of the elephant and the blind men, I said I wanted to see the whole elephant, but I was still limited to one angle. There are other angles worth exploring. For instance, post-structural approaches, such as those that derive from Derrida’s (Citation1985) ideas of deconstruction, have helped translation studies scholars ask about the semantic slippage that occurs not only between languages but also within them. But no one has yet used these approaches to inquire into news translation. The same is true for narrative theory, which communication scholars have also used to look at news (e.g., Hartley, Citation1982). My materialist approach has grown out of the synthesis and further development of the published work on news translation, but that is only a narrow sliver of translation studies. Ultimately, the study of news translation can only benefit from the application of a wider range of theoretical tools.

Notes on contributor

Kyle Conway joined the University of Ottawa in 2015, where he is an assistant professor in communication. His books include Everyone Says No: Public Service Broadcasting and the Failure of Translation (McGill-Queen’s, 2011) and Beyond the Border: Tensions across the Forty-ninth Parallel in the Great Plains and Prairies (co-edited with Timothy Pasch, McGill-Queen’s, 2013).

Notes

1. This article is a theoretical counterpart to a methodological argument I make elsewhere (Conway, Citation2008).

2. describes approaches that focus on the production and circulation of news. It neglects two recent lines of inquiry, audience studies and historiography, about which work has only just begun to be produced (e.g. Valdeón, Citation2012).

3. The terms ‘hard news’ and ‘soft news’ come from the United States. Although they are current elsewhere, too, I have chosen not to use them because they developed in the specific context of US newsrooms, where they grew out of journalists’ routine for finding and writing stories (see Tuchman, Citation1978).

4. The literature since Fujii’s (Citation1988) article has consistently demonstrated that news translation involves more forms of transformation than linguistic re-expression.

5. The authorship of Vološinov’s work is disputed, and some people attribute his major work, Marxism and the Philosophy of Language, to Bakhtin. See the translators’ note in Vološinov (Citation1929/Citation1986).

6. No matter how conscientious and careful translators are, they must always contend with such slippage in the transfer from one language (or sign system) to another.

7. My notion of genre comes from media studies, rather than translation studies. Efforts in translation studies to understand ‘text type’ (e.g. Trosbord, Citation1997) have produced wide-ranging results, but they presume we can speak of ‘source’ and ‘target’ texts. In news translation, these terms are rarely applicable. Media studies treats genre differently, as ‘a property and function of discourse’ and asks how ‘various forms of communication work to constitute generic definitions and meanings’ (Mittell, Citation2001, p. 8). Ideas of what constitutes news develop in tandem with journalists’ work habits and their efforts to manage audiences’ expectations (Schudson, Citation2011; Tuchman, Citation1978). The way journalists act on those ideas shapes the texts they produce; hence the idea of genre as a tacit agreement between journalists and audiences.

References

- Abdel-Hafiz, A.-S. (2002). Translating English journalistic texts into Arabic: Examples from the Arabic version of Newsweek. International Journal of Translation, 14(1), 79–103.

- Bakhtin, M. M. (1986). Speech genres and other late essays. (V. W. McGee, Trans.). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

- Bani, S. (2006). An analysis of press translation process. In K. Conway & S. Bassnett (Eds.), Translation in global news proceedings of the conference held at the University of Warwick, 23 June 2006 (pp. 35–45). Coventry: University of Warwick Centre for Translation and Comparative Cultural Studies.

- Benjamin, W. (1923/1997). The translator’s task. (S. Rendall, Trans.). TTR: Traduction, Terminologie, Rédaction, 10(2), 151–165. doi:10.7202/037302ar

- Bielsa, E., & Bassnett, S. (2009). Translation in global news. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Boyd-Barrett, O. (1980). The international news agencies. London: Sage.

- Bulut, A. (2012). Translating political metaphors: Conflict potential of zenci [negro] in Turkish-English. Meta, 57(4), 909–923. doi:10.7202/1021224ar

- Carey, J. W. (1988). Communication as culture: Essays on media and society. Cambridge, MA: Unwin Hyman.

- Chu, L. (1985). Translation as a source of distortions in international news flow. Third Channel, 1(1), 41–51.

- Collins, R. (1990). Culture, communication, and national identity: The case of Canadian television. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Conway, K. (2008). A cultural studies approach to semantic instability: The case of news translation. Linguistica Antverpiensia (New Series), 7, 29–43.

- Conway, K. (2010). News translation and cultural resistance. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 3(3), 187–205. doi:10.1080/17513057.2010.487219

- Conway, K. (2011). Everyone says no: Public service broadcasting and the failure of translation. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- D’Acci, J. (2004). Cultural studies, television studies, and the crisis in the humanities. In L. Spigel & J. Olsson (Eds.), Television after TV: Essays on a medium in transition. Durham, NC: Duke University Press 418–445.

- Dahlgren, P., & Chakrapani, S. (1982). The third world on TV news: Western ways of seeing the ‘other’. In W. Adams (Ed.), Television coverage of international affairs (pp. 45–65). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

- Davier, L. (2014). The paradoxical invisibility of translation in the highly multilingual context of news agencies. Global Media and Communication, 10(1), 53–72. doi:10.1177/1742766513513196

- de Man, P. (1986). The resistance to theory. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Derrida, J. (1985). Des tours de Babel [Towers/Tours of Babel]. In J. F. Graham (Ed.), Difference in translation (pp. 209–248). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Fujii, A. (1988). News translation in Japan. Meta, 33(1), 32–37. doi:10.7202/002778ar

- Gagnon, C. (2012). La visibilité de la traduction au Canada en journalisme politique: mythe ou réalité? [Translation’s visibility in Canadian political journalism: Myth or reality?]. Meta, 57, 943–959. doi:10.7202/1021226ar

- Hall, S. (1980). Encoding/decoding. In S. Hall, D. Hobson, A. Lowe & P. Willis (Eds.), Culture, media, language (pp. 128–138). London: Hutchinson.

- Hartley, J. (1982). Understanding news. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Henningham, J. P. (1979). Kyodo Gate-keepers: A study of Japanese news flow. Gazette, 25, 23–30. doi:10.1177/001654927902500103

- International Commission for the Study of Communication Problems. (1980). Many voices, one world: Towards a new, more just and more efficient world information and communication order. Paris: UNESCO.

- Jakobson, R. (1959/2004). On linguistic aspects of translation. In L. Venuti (Ed.), The translation studies reader (2nd ed., pp. 138–143). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Lee-Reoma, S.-C. (1978). The translation gap and the flow of news. WACC Journal, 25(1), 13–17.

- Marx, K. (1852/1994). Eighteenth brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (E.F. Trans & Emil F. Teichert). New York: International Publishers.

- McLaughlin, M. (2011). Syntactic borrowing in contemporary French: A linguistic analysis of news translation. Oxford: Legenda.

- McLaughlin, M. (2015). News translation past and present: silent witness and invisible intruder. Perspectives. Advance online publication. 23(4). doi:10.1080/0907676X.2015.1015578

- Mittell, J. (2001). A cultural approach to television genre theory. Cinema Journal, 40(3), 3–24. doi:10.1353/cj.2001.0009

- Pym, A. (2004). The moving text: Localization, translation, and distribution. Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins.

- Schäffner, C. (2012). Rethinking transediting. Meta, 57(4), 866–883. doi:10.7202/1021222ar

- Schudson, M. (2011). The sociology of news (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Norton.

- Sorby, S. (2006). Translating news from English to Chinese: Complimentary and derogatory language usage. In K. Conway & S. Bassnett (Eds.), Translation in global news proceedings of the conference held at the University of Warwick, 23 June 2006 (pp. 113–126). Coventry: University of Warwick Centre for Translation and Comparative Cultural Studies.

- Stetting, K. (1989). Transediting—a new term for coping with the grey area between editing and translating. In G. Caie, K. Haastrup, A. Jacobsen, J. Nielson, J. Sevaldsen, H. Specht & A. Zettersten (Eds.), Proceedings from the fourth Nordic conference for English studies (pp. 171–182). Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen.

- Trosbord, A. (Ed.). (1997). Text typology and translation. Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins.

- Tuchman, G. (1978). Making news: A study in the construction of reality. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Valdeón, R. A. (2012). From the Dutch corantos to convergence journalism: The role of translation in news production. Meta, 57(4), 850–865. doi:10.7202/1021221ar

- van Doorslaer, L. (2010a). The double extension of translation in the journalistic field. Across Languages and Cultures, 11, 175–188. doi:10.1556/Acr.11.2010.2.3

- van Doorslaer, L. (2010b). Journalism and translation. In Y. Gambier & L. van Doorslaer (Eds.), Handbook of translation studies (Vol. 1). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Retrieved from https://benjamins.com/online/hts/

- Vaskivska, T., Conway, K., & Shafer, R. (2013). Journalists as agents of cultural translation: A case study of Spanish newspaper coverage of bans on tradition head coverings for Muslim women. Journal of Development Communication, 24(1), 51–69.

- Vološinov, V. N. (1929/1986). Marxism and the philosophy of language. (L. Matejka & I. R. Titunik, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wilke, J., & Rosenberger, B. (1994). Importing foreign news: A case study of the German service of the Associated Press. Journalism Quarterly, 71(2), 421–432. doi:10.1177/107769909407100215

- Williams, R. (1983). Keywords. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.