Abstract

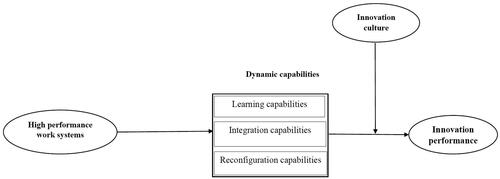

In this study, we develop and test a framework that theorizes how high-performance work systems (HPWS)—a set of interrelated HR practices—build dynamic capabilities (i.e. learning, integration, and reconfiguration capabilities), which in turn lead to innovation performance. We also hypothesize that organizations with a stronger innovation culture, where employees share a common understanding of the value and importance of innovation, will be better able to convert capabilities into innovation performance. We test our hypotheses using time-lagged, multisource data from 173 companies in the Iranian pharmaceutical industry, a knowledge-intensive, high-velocity environment highly dependent on HRs to innovate. Our results show that the relationship between HPWS and innovation performance is mediated by dynamic capabilities (DCs). Further, alongside finding support for the moderating effect of innovation culture in the relationship between DCs and innovation performance, we find that innovation culture moderates the indirect effect of HPWS on innovation performance via DCs such that innovation culture strengthens the mediated relationship. The theoretical and practical implications of our findings are discussed.

Introduction

Organizations in emerging economies operate in a dynamic and uncertain environment where technological changes, ever-changing regulations, increased competition, and entrepreneurial actions occur with amplified frequency To generate value and achieve a sustainable competitive advantage in such environments, organizations must be able to adapt and innovate quickly (Subramaniam & Youndt, Citation2005). The resource-based view (RBV) of the firm argues that employees are an important resource that enable organizations to adapt in dynamic environments and achieve a competitive advantage (Barney, Citation1991; Barney et al., Citation2001). Indeed, extensive research confirms that the strategic use of HRs such as high-performance work systems (HPWS) positively contribute to an organization’s ability to achieve a competitive advantage. HPWS are defined as bundles of HR practices designed to enhance the abilities, motivation, and opportunities of an organization’s workforce (Boxall, Citation2012; Hung et al., Citation2010; Ogbonnaya & Valizade, Citation2018; Way et al., Citation2015).

While several mechanisms have been proposed linking HPWS to organizational performance in general and innovation in particular (Gahan et al., Citation2021; Jiang et al., Citation2012; Wei & Lau, Citation2010), researchers continue to call for additional theoretical development and empirical evidence, particularly with the specific outcomes studied (Saridakis et al., Citation2017). In response to these calls, researchers have linked HPWS to organizational outcomes through various types of organizational capabilities, such as learning (Jerez-Gómez et al., Citation2019), ambidexterity (Patel et al., Citation2013), adaptive capability (Wei & Lau, Citation2010), and absorptive capacity (Soo et al., Citation2017). These studies have operationalized organizational capabilities from different views and in different contexts in terms of industry type and environmental conditions, leading to tenuous conclusions. Consequently, this area remains somewhat fragmented in terms of the types of capabilities developed by HPWS and how those capabilities link to innovation performance, highlighting the need for more research on how HPWS contribute to innovation performance through organizational capabilities (Shipton et al., Citation2006, Citation2017).

In the current study, we posit that HPWS foster organizational innovation in part through the development of dynamic capabilities (DCs). Dynamic capabilities are defined as ‘a firm’s ability to integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments’ (Teece et al., Citation1997, p. 516). While DCs are viewed as an important source of innovation and value creation in dynamic environments, the understanding of how organizations develop DCs is less clear. In this regard, we argue that HPWS, consisting of HR practices designed to enhance employees’ abilities, motivation, and opportunity (AMO) (Appelbaum et al., Citation2000), help build the three core dimensions of DCs (i.e. learning, integration, and reconfiguration capabilities), which in turn enable firms to learn from within and outside the firm, integrate acquired resources, and properly reconfigure themselves in response to external changes. Although previous research recognizes that HR systems are related to the development of capabilities (e.g. Lin & Wu, Citation2014; Wei & Lau, Citation2010), we propose that DCs are a more robust, yet parsimonious, mechanism for understanding the link between HPWS and innovation performance.

In addition to examining the mediating role of DCs between HPWS and innovation performance, we also consider how the organizational context influences the ability of firms to translate HPWS and DCs into innovation performance. The organizational context influences how employees interpret and perceive phenomena in organizations, which in turn, affect attitudes and behaviours (Ferris et al., Citation1998; Johns, Citation2006). When a workforce has a common understanding of the purpose and practices associated with HR systems, it can strengthen the relationship between the system and firm outcomes (Bowen & Ostroff, Citation2004). Although a wide range of contextual factors potentially link HPWS, capabilities, and innovation performance such as psychological safety (Rasheed et al., Citation2017), voice opportunity (Shahzad et al., Citation2019), organizational engagement (Gahan et al., Citation2021), and transformational leadership (Chen et al., Citation2012), innovation culture is a broader contextual factor addressing both an organization’s infrastructure conducive for innovation, as well as the goals and values oriented towards creativity and innovation (Martín-de Castro et al., Citation2013). A firm’s innovation culture shapes the mindset of a workforce and directs employees’ efforts, behaviours, and interactions towards the common goal of innovation performance (Dodge et al., Citation2017). Hence, we examine how an organization’s innovation culture fosters an organization’s activities and capabilities towards the introduction of new ideas, processes, or products.

Overall, the current study makes several contributions to the literature. First, there is both theoretical and practical value in examining how DCs, as firm-level capabilities, link HPWS to innovation performance. Although some researchers have assumed such a relationship exists or test only one type of capability, we provide empirical evidence of the role of HPWS in building DCs (i.e. learning, integration, and reconfiguration) and, in turn, increased innovation performance. Second, we examine how a firm’s innovation culture affects the ability of firms to direct DCs towards innovation performance. When firms develop a culture in which employees can safely express new ideas, offer constructive feedback on others’ ideas, and take risks without fear of punishment, the organization will be more likely to translate its resources and capabilities into innovation. Further, we explore whether innovation culture moderates the indirect effect of HPWS on innovation performance through DCs. This approach adds new insights on the importance of innovation culture in understanding how HPWS convert resources into capabilities for innovation.

Finally, we test our model in a knowledge-intensive, high-velocity environment (i.e. Iranian pharmaceutical industry) that is highly dependent on HRs to innovate (Farzaneh et al., Citation2021) and achieve organizational outcomes (Hess & Rothaermel, Citation2011). This setting is novel to the HPWS literature and particularly relevant to DCs and innovation (Tasavori et al., Citation2021). Iranian firms face numerous unexpected environmental changes due to economic sanctions against the country, and they inevitably struggle to procure needed materials and maintain operations (Mehralian et al., Citation2017). HPWS provide a more flexible approach to HRM than control-based approaches, enabling firms to reconfigure existing resources in the face of environmental constraints. Hence, we extend the generalisability and applicability of SHRM theories to a Middle Eastern country marked by political and economic uncertainty.

Theory and hypothesis development

Over the last several decades, the RBV has been used as a foundation to explain how HR practices can be a source of competitive advantage and innovation performance. This theory conceptualizes firms as bundles of resources and suggests that the possession of inimitable resources can facilitate the achievement of competitive advantages, leading to outstanding performance. Drawing on the RBV, scholars have emphasized the role of HPWS in creating organizational-level capabilities, such as DCs, and their contribution to organizational performance (Beltrán-Martín et al., Citation2008; Chadwick & Flinchbaugh, Citation2021; Seeck & Diehl, Citation2017). The DCs perspective, as an extension of the RBV, emphasizes that the evolution, reconfiguration, and renewal of the firm’s resources and capabilities must occur for firms to survive in dynamic environments (Baía & Ferreira, Citation2019; Farzaneh et al., Citation2022). More specifically, DCs are highly patterned, repetitive organizational routines that lead to changes in the firm’s available resource base (Eisenhardt & Martin, Citation2000; Teece et al., Citation1997), and consist of three activities/routines for generating innovation and sustaining competitiveness: learning, integration, and reconfiguration (Teece, Citation2007). Consequently, as displayed in , we argue that DCs (i.e. learning, integration, and reconfiguration capabilities) mediate the relationship between HPWS and innovation performance at the organization level of analysis.

HPWS and dynamic capabilities

HPWS involve a set of HR practices that exhibit interrelationships and mutual reinforcement (Kehoe & Wright, Citation2013), and when aligned, they form HPWS (Jiang et al., Citation2012; Lepak et al., Citation2006). While each individual HR practice targets a specific aspect of the individual or team experience, it is widely recognized that bundles of practices create a stronger HR system that builds synergies within an organization and can accumulate to influence organizational effectiveness (Bowen & Ostroff, Citation2004). For example, some researchers view HPWS as having three main dimensions, namely practices that enhance employees’ abilities, motivation, and opportunities (AMO) (Appelbaum et al., Citation2000; Boxall & Macky, Citation2009; Lepak et al., Citation2006). Ability-enhancing practices are designed to improve employees’ knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs) through activities such as rigorous recruitment and selection processes, and training (Obeidat et al., Citation2016). Motivational practices, such as linking performance with appraisal systems and rewards, help increase employee motivation and performance management (Katou & Budhwar, Citation2010). Finally, opportunity-enhancing practices emphasize employee involvement and collaboration through a wide range of activities such as flexible workplace design and work schedules, team-based work, information sharing, and employee participation in decision-making (Jiang et al., Citation2012). In this paper, we use the AMO framework to understand how organizations build the three dimensions of DCs: learning, integration, and reconfiguration.

Of the three dimensions of DCs, learning capabilities have been most closely linked to HR practices. Learning capabilities help organizations avoid repeating mistakes from past experiences (Yalcinkaya et al., Citation2007) and are necessary for organizations to respond to rapid changes in the marketplace. Learning capabilities depend on the organization’s ability to accumulate experience, as well as the development of knowledge articulation and codification activities (Zollo & Winter, Citation2002). In terms of the accumulation of experience, HPWS help manage the inflow of new knowledge both by attracting and selecting employees who bring in distinct KSAs (Kang et al., Citation2007; Wang & Zatzick, Citation2019), and by supporting and encouraging learning via extensive training. Indeed, researchers report that HPWS have a significant impact on organizational learning by providing employees with a wide range of learning and training opportunities (Collins & Smith, Citation2006; Jerez-Gómez et al., Citation2019). Further, HPWS enhance knowledge articulation and codification through opportunity-enhancing practices designed to increase communication, transparency, and employee involvement (Mehralian et al., Citation2021). Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 1: HPWS are positively related to learning capabilities.

In line with the microfoundations view of strategic HRM practices, we argue that HPWS build the necessary routines and work activities needed for the development of collective knowledge at the organizational level, leading to integration capabilities (Minbaeva, Citation2013). For example, HPWS use teams and information sharing to build intra-organizational networks, which enable organizations to connect diverse knowledge and experiences across its workforce (Hansen & Nohria, Citation2004; Lin & Chen, Citation2006; Song et al., Citation2018). Team-based work also strengthens relationships between employees, which further contributes to the development of integration capabilities within an organization (Dixon et al., Citation2014). Finally, opportunity-enhancing practices allow employees to engage in decision-making and problem-solving, which can improve the flow of information and increase collaboration, both of which are needed for integration (Bowen & Ostroff, Citation2004). Taken together, HPWS help organizations improve their ability to integrate internal and external knowledge (Minbaeva, Citation2005). Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2: HPWS are positively related to integration capabilities.

In summary, HPWS not only help organizations learn from both inside and outside the organization and integrate newly acquired knowledge with existing knowledge, but they also help organizations reconfigure themselves in response to changing external conditions (Lin & Wu, Citation2014). Therefore, we posit the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: HPWS are positively related to reconfiguration capabilities.

Linking HPWS to innovation performance through DCs

Prior research identifies HPWS as an important factor influencing organizational innovation. HPWS build employee KSAs, encourage collaboration, and create opportunities for employee involvement, all of which contribute to employee creativity and, in turn, organizational innovation (Camps & Luna-Arocas, Citation2012; Sung & Choi, Citation2018). Further, HPWS focus on the enrichment of work by increasing the skill variety, autonomy, and responsibility in jobs, all of which increase internal work motivation, an important precursor of employee creativity (Hackman & Oldham, Citation1976). Finally, when organizations have open communication and provide team-based compensation, the generation, development, and implementation of innovative ideas is more likely (De Spiegelaere et al., Citation2018). Hence, prior research argues that HPWS help build a sustainable competitive advantage for organizations, in part through the ability to innovate.

It is widely discussed, however, that HR practices do not directly lead to organizational innovation, but are first converted to organizational capabilities to give organizations more opportunities to meet market needs effectively (Lin & Wu, Citation2014; Shahzad et al., Citation2019). With respect to DCs, innovation requires active resource orchestration via high-level routines. The role of employees is central to the DCs viewpoint, as much of the DCs literature is concerned with changing behaviour, as well as with building and reconfiguring internal and external competencies (Teece et al., Citation1997). As Zollo and Winter (Citation2002) note, a fundamental challenge in building DCs involves changing the resource base (Helfat & Peteraf, Citation2009), as well as the routines, behaviours, and work patterns (Eisenhardt & Martin, Citation2000; Zollo & Winter, Citation2002).

Consequently, we argue that the relationship between HPWS and innovation performance develops through DCs. Prior research is suggestive of this mediated relationship in various contexts. For example, Patel et al. (Citation2013) report that HPWS generate flexibility in the form of ‘organizational ambidexterity’, which allows organizations to adapt and innovate in response to environmental changes. In addition, Zahra and George (Citation2002) found that, when properly developed, integration capabilities can enable firms to combine new and existing knowledge to generate new ideas. Likewise, Wei and Lau (Citation2010) reported that adaptability mediates the relationship between HPWS and organizational innovation performance. Finally, research has shown that the development of DCs can improve radical innovation in established firms (Chiu et al., Citation2016). The underlying rationale of these studies is that DCs are an important mechanism that explains how organizational resources are translated to innovation performance. Moreover, in the context of our study, organizations in developing economies and knowledge-based industries rely more heavily on DCs than organizations in other contexts due to rapidly changing environmental conditions (Fainshmidt et al., Citation2016). Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 4: The positive relationship between HPWS and innovation performance is mediated by DCs.

The moderating role of innovation culture

From a social context perspective, an organization’s environment is critical for understanding the effect of HR practices on the organizational outcomes (Ferris et al., Citation1998). One overarching aspect of the social context is an organization’s culture, which encompasses the shared values, beliefs, and assumptions of organizational members, and offers the guiding principles that direct behaviours towards achieving organizational goals. In particular, an organization’s innovation culture is viewed as an important contextual factor capable of influencing innovation performance (Martín-de Castro et al., Citation2013). An innovation-oriented culture values open-mindedness, learning, and creativity such that employees share an understanding of how HR practices work together towards a firms’ innovation goals (Tian et al., Citation2018). A stronger innovation culture develops when organizations encourage employees to take more risks, increase the psychological safety for employees to express new ideas, and provide resources to increase employees’ willingness to embrace new challenges (Ireland et al., Citation2003; Van Esch et al., Citation2018). Therefore, innovation culture shapes employees’ mindset and behaviour as they participate in and carryout the activities within an organization.

In the current study, we argue that a strong innovation culture helps translate organizational capabilities towards innovation performance (Ali & Park, Citation2016; Chen et al., Citation2012; Tian et al., Citation2018). Although DCs alone can increase innovation performance, we expect organizations with a stronger innovation culture will be better able to direct DCs towards innovation performance. In a strong innovation culture, the routines and activities associated with DCs will be carried out by employees who hold a common understanding that new and creative ideas are valued and taking risks towards this goal is supported (Shalley & Gilson, Citation2004). For example, while an organization’s reconfiguration capabilities inherently involve routines and activities that make it possible to combine diverse resources, a stronger innovation culture will provide a strategic focus and frame of reference supportive of creativity and innovation. In contrast, in organizations with weaker innovation cultures, employees carrying out these activities may be concerned about taking risks or offering new ideas beyond organizationally sanctioned approaches to the reconfiguration process. Furthermore, when an organization’s culture is oriented towards other outcomes such as efficiency, employees may carry out the activities around integration or reconfiguration with the express intent of finding savings rather than on developing new and/or improved products. Thus, when DCs operate in an organizational context that encourages and supports innovation, the positive effect of DCs on innovation performance will be enhanced. In formal terms, we predict:

Hypothesis 5: The positive relationship between DCs and innovation performance is stronger in organizations with a stronger, as compared to a weaker, innovation culture.

Method

Research setting

The data for the present study were collected from organizations in the Iranian pharmaceutical industry. The pharmaceutical industry has grown rapidly in recent decades in terms of market value and the number of new products launched. Approximately 75% of the market value belongs to local manufacturing firms, most of which are involved in international collaborations with foreign firms for co-development and co-marketing of products (Ghasemzadeh et al., Citation2021). The pharmaceutical industry is well suited to test our hypotheses for several reasons. First, as illustrated by the COVID-19 pandemic, firms in this industry must respond quickly to market needs, be able to reconfigure internal resources, and be responsive to social concerns (Droppert & Bennett, Citation2015). Secondly, they are not only competing with leading pharmaceutical companies but also with companies that produce generic drugs around the world. Thus, they have to meet both local and international standards and regulations in order to obtain marketing approval (Khanna, Citation2012). This creates a dynamic and competitive environment where innovation is critical. Finally, given the central role of HR in the pharmaceutical industry (Hess & Rothaermel, Citation2011), most firms invest in HRM practices and are concerned about the extent to which these practices affect their business performance.

Sample and procedure

The Iranian pharmaceutical industry consists of approximately 200 companies that produce finished drugs, active pharmaceutical components, and pharmaceutical grade packaging. The study spanned two years between September 2015 and September 2017. Because HPWS take several years to develop (Patel et al., Citation2013), we first invited those firms with at least three years of experience to participate in our study. To this end, we sent an email to the CEO of each company explaining the main research objectives and ethical considerations. A total of 183 companies agreed to participate in our study.

To reduce concerns about common method bias, data were collected from multiple respondents. In addition, to control for cross-sectional biases, innovation performance was assessed with objective data collected approximately one year after the survey. At time 1, three different sources were used to collect data: senior HR managers (one per company) reported on HPWS, CEOs assessed dynamic capabilities, and middle managers (approximately 4 per company) reported on innovation culture. A total of 176, 184, and 671 completed questionnaires were provided by CEOs, HR managers, and middle managers, respectively, representing a response rate of approximately 88%. A face-to-face survey was conducted with the CEOs to increase the accuracy of the responses, whereas the remaining surveys were distributed via email. Finally, we collected objective data in 2017 (described below) regarding innovation performance from government records. After data cleaning and matching, we received completed questionnaires from 173 firms, representing a response rate of 85%. Approximately 88% of the respondents reported having a master’s degree and the other 12% a doctorate. This shows that most of the respondents were highly skilled workers who were in a good position to report on our key variables. The average tenure of the respondents was 7.5 years. The age of the firm ranged from 5 to 63 years, and the firm’s size ranged from 60 to 1200 employees.

Measurement

In order to test the proposed model and hypotheses, a questionnaire was prepared. To ensure the quality of the translation into Persian and that no critical elements of the original questionnaire were lost in translation, it was translated back into English (Brislin, Citation1970). A pretest of 11 personal interviews with both scholars and HR managers of the pharmaceutical companies was carried out to ensure that the questionnaire made sense in this context (i.e. face validity). Unless otherwise noted, all questions were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). shows all the items as part of the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

Table 1. Confirmatory factor analyses, item loadings, and scale reliability.

High performance work systems (HR managers) were measured using the existing scales for the AMO framework (Li-Yun et al., Citation2007; Prieto & Santana, Citation2012). A total of 29 items were used to measure the three dimensions of HPWS (Appelbaum et al., Citation2000; Chowhan, Citation2016): ability-enhancing (10 items), motivation-enhancing (9 items), and opportunity-enhancing (10 items) practices. Consistent with prior research, HPWS were treated as a multidimensional, second-order construct consisting of three first-order constructs (i.e. ability, motivation, and opportunity), with composite reliability of 0.89 (see for items and factor loadings).

To measure dynamic capabilities (CEOs), we asked CEOs to indicate the degree of each component in their organizations at time 1. The learning (5 items), integration (4 items), and reconfiguration (4 items) components were assessed using existing scales (Lin & Wu, Citation2014). Dynamic capabilities were treated as a multidimensional construct, and to test H4, we created a second-order construct consisting of the three first-order constructs of learning, integration, and reconfiguration capabilities, with composite reliability of 0.86 (see for items and factor loadings).

Innovation culture (middle managers) was measured using 12 items consistent with existing scales (O’Cass & Ngo, Citation2007; Park et al., Citation2016). Middle managers of each firm were asked to indicate the level of innovation culture in their respective firms. Then, the innovation culture scores were calculated at the firm level by averaging the innovation culture scores of all participating middle managers in each firm. In order to aggregate the data at a higher level of analysis, interclass correlations (ICC) were calculated; the use of ICC1 (0.08) and ICC2 (0.44) aimed to represent the variance mapped for group membership and the reliability of the group mean. In addition, the multiple-item rwg(j) was used to illustrate the aggregation of the data at the individual level and showed a mean of 0.75. All statistics showed adequate validity in accordance with the recommended levels of agreement (Bliese, Citation2000; see for items, factor loadings, and reliabilities).

Innovation performance was collected from publicly available archival sources provided by the Ministry of Health and Medical Education (IFDA, Citation2017). These records consist of data on the number of new products and patents filed by each pharmaceutical company with the Ministry of Health and Medical Education. Therefore, innovation performance was assessed using a 1-year lagged objective measure of innovation.

We controlled for several factors that could potentially affect our results. The firm’s age and size are likely to be related to both HRM practice implementation (Guthrie, Citation2001) and innovation performance (Wu et al., Citation2016). Further, we collected information on prior year innovation performance from government records to account for a baseline level of innovation within a firm.

Data analysis

A second-order factor analysis was conducted for the measures of HPWS and dynamic capabilities. The criteria used to select the factors were in accordance with those proposed by Kaiser (Citation1958), including an eigenvalue >1 along with an absolute loading factor value >0.5. As shown in , Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for all the variables are above the acceptable value of 0.7, which supports the reliability of our constructs (Hahn, Citation1962; Kaiser, Citation1958). Convergent validity is achieved through high scores of factor loading and average variance extracted (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). According to , all scores of average variance extracted are greater than 0.5, and all factor loadings are equal and greater than 0.63, reaching the acceptable level (Marin-Garcia & Tomas, Citation2016). Discriminant validity was evaluated using Fornell and Larcker’s approach (1981). The results showed discriminant validity across all latent variables. We then used AMOS maximum likelihood estimation (Arbuckle & Wothke, Citation1999) to establish the measurement properties of the latent variables. We tested a series of CFA models.

As shows, to test the goodness-of-fit of the measurement model, we first analyzed a three-factor CFA model in which HPWS, DCs, and innovation culture were entered to ensure that sufficient convergent and discriminant validity existed between all the constructs. The model provided an acceptable fit to the data: χ2 (165) = 745.814, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.06; CFI = 0.93 (Browne & Cudeck, Citation1992). Several two-factor models also were conducted where we combined two of the factors (e.g. HPWS and DCs) as one factor along with a third factor (e.g. innovation culture). For the one-factor model, all three constructs were combined. By comparing the three-factor model with the two- and one-factor models, we found that the three-factor model has a better fit than the alternative models, resulting in sufficient discriminant validity of the constructs.

Table 2. Confirmatory factor analyses fit statistics.

We used hierarchical regression to test Hypotheses 1–3 and 5, and the PROCESS macro bootstrapping method using SPSS (version 25.0) to test the mediating effect proposed in Hypothesis 4.

Results

shows the descriptive statistics of means and correlations. HPWS was positively correlated with innovation performance (r = 0.65, p < 0.01). Additionally, firm age (r = −0.11, p < 0.01) is negatively correlated with HPWS, indicating that younger firms had more extensive HR systems. The correlations in our study are moderately high but do not exceed the commonly accepted threshold of 0.70, for when multicollinearity concerns arise (Kline, Citation2016). Additionally, we conducted variance inflation factor (VIF) tests and found no evidence of multicollinearity, as the VIF was less than 2.05 in all our models (Gujarati, Citation2009).

Table 3. Means, standard deviations, and correlations.

In , the three dimensions of DCs were considered separate dependent variables in order to examine the links between HPWS and each DCs. In the first regression model (M1), the control variables were introduced into the analysis, after which HPWS was added as an independent variable (M2, M4, and M6). The results showed that HPWS was significantly and positively related to each dimension of DCs: learning (β = 0.39, p < 0.01), integration (β = 0.33, p < 0.01), and reconfiguration (β = 0.41, p < 0.01). Thus, our results support Hypotheses 1 − 3.

Table 4. Results of regression analysis predicting dynamic capabilities and innovation performance.

further shows regression results for the mediated relationship between HPWS and innovation performance.Footnote1 HPWS (M8: β = 0.43, p < 0.01) and DCs (M8: β = 0.39, p < 0.01) are positively and significantly related to innovation performance. We used the PROCESS macro bootstrapping method (PROCESS model 4) for the analysis of mediated effects (Hayes, 2012). With 5000 times resampling, the indirect effect of HPWS on innovation performance (β = 0.407, CI = 95%, [0.341, 0.516]) through DCs was significant (confidence interval does not include zero), indicating support for Hypothesis 4.

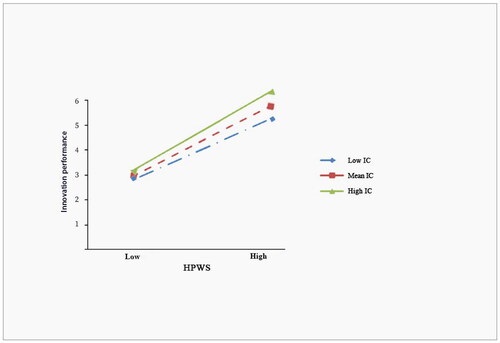

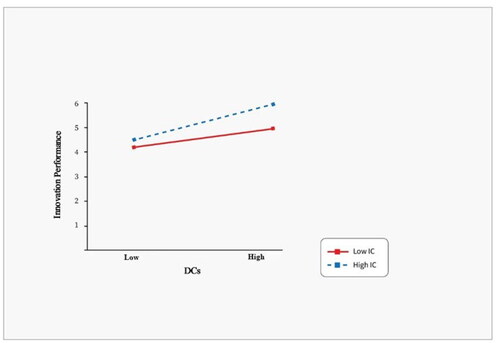

To test the moderating effect of innovation culture (H5), we sequentially added innovation culture and the interaction term to the regression analyses. As shown in , when innovation culture was added, DCs still exert a positive influence on innovation performance (M9: β = 0.35, p < 0.01). Finally, the interaction term (DCs*innovation culture) was positive and significant (M10: β = 0.26, p < 0.01), indicating that the relationship between DCs and innovation performance is stronger at higher levels of innovation culture, consistent with Hypothesis 5. As shown in , the change in R2 from the interaction term (DCs*innovation culture) was significant. To interpret the interaction results, we graphed the moderation effect at one standard deviation above and below the mean for DCs and innovation culture (see ).

Figure 2. Moderating effect of innovation culture on the relationship between dynamic capabilities and innovation performance. Note. DCs: dynamic capabilities; IC: innovation culture.

An alternative model

Thus far, our findings indicate that DCs mediate the relationship between HPWS and firm innovation, and innovation culture moderates the relationship between DCs and innovation performance. It is also possible that innovation culture, as an overarching contextual factor, plays a bigger role in influencing the relationships in our model.Footnote2 Scholars have argued that the social context can constrain or amplify relations between variables, indicating a moderating role of context for shaping attitudes and behaviour (Bamberger, Citation2008; Johns, Citation2018). In line with these arguments, an organization with a stronger innovation culture will develop a workforce that holds a common understanding that new and creative ideas are valued and risk-taking towards innovation performance is supported. The shared mindset associated with a strong innovation culture is likely to influence how employees understand and carryout the HR activities associated with HPWS and the development of DCs (Ferris et al., Citation1998; van Esch et al., Citation2018). In other words, a stronger innovation culture stimulates a consistent line of sight from HPWS to innovation performance through DCs, whereas in organizations with a weaker innovation culture there will be more variability in how and when employees will strive for innovation performance through the capabilities developed in a HPWS. Consequently, although we did not originally hypothesize a first stage moderated mediation relationship, social context theory suggests the possibility of innovation culture moderating both the relationship between HPWS and DCs, and the indirect effect of HPWS on innovation performance through DCs.

To test this alternative model, we utilized the PROCESS macro in SPSS (PROCESS model 7).Footnote3 The results show that the indirect effects of HPWS through DCs on innovation performance were statistically significant at low (β = 0.124, [0.017, 0.141]), mean (β = 0.204, [0.028, 0.243]), and high (β = 0.284, [0.102, 0.323]) levels of innovation culture. Further, the index of moderation mediation was significant (β = 0.112, [0.055, 0.283]), which indicates stronger indirect effects at high (+1SD) as compared to low (−1SD) levels of innovation culture. illustrates the conditional indirect effects for this alternative model.

Discussion

Given the central role of HRM practices in achieving organizational outcomes, this study developed and empirically tested a conceptual model of how HPWS influence firms’ innovation through the development of dynamic capabilities. We provide arguments for how HPWS build the dynamic capabilities of learning, integration, and reconfiguration towards improved innovation performance. HPWS encompass practices that allow organizations to acquire and develop a highly skilled workforce, ensure open communication both horizontally and vertically to share knowledge, and provide autonomy and decision-making opportunities (Jiang et al., Citation2012). Further, we propose and find evidence that an organization’s innovation culture can direct DCs towards innovation performance. A strong innovation culture ensures that employees have a common understanding that creativity and innovation are valued and expected, which helps firms translate HPWS into DCs and, in turn, innovation performance. The implications of these findings are discussed below.

Implications for research

Our study makes several contributions to the literature. First, this study builds on the DCs view of the firm (Teece et al., Citation1997) by proposing and empirically validating HPWS as a means for organizations to shape their HRs to meet the challenges of a dynamic environment through the dynamic capabilities of learning, integration, and reconfiguration. In dynamic environments, timely recognition and response to opportunities and changes are paramount to remaining competitive (Teece et al., Citation2016). While prior studies have proposed various organizational capabilities resulting from HPWS including, ambidexterity (e.g. Patel et al., Citation2013), adaptability (Wei & Lau, Citation2010), and absorptive capacity (Soo et al., Citation2017), we propose that DCs provide a more robust framework for understanding how HPWS contribute to an organization’s competitive advantage when operating in a dynamic environment. Therefore, we provide theory and empirical evidence for the relationship between HPWS and the three dimensions of DCs.

Second, this study underscores the role of innovation culture as a facilitator in converting HPWS and dynamic capabilities into innovation performance (e.g. Shipton et al., Citation2017; Wei et al., Citation2011). Although some studies view HPWS and DCs as direct catalysts for innovation performance, we provide support for the idea that firms also need to create a context conducive to employees’ creativity in order to fully capture the benefits of both HPWS and dynamic capabilities. This is consistent with the social context theory of HRM (Ferris et al., Citation1998) where the shared understanding of the HR system influences a firm’s ability to translate HR practices and subsequent developed capabilities into performance (Bowen & Ostroff, Citation2004; Van Esch et al., Citation2018). Our findings, both hypothesized and exploratory, augment social context theory by showing that innovation culture, as a contextual factor, can indirectly facilitate the effect of HR systems and organizational capabilities on innovation performance. Likewise, the inclusion of innovation culture into dynamic capabilities research suggests some future research directions. For example, recent studies emphasizing how dynamic capabilities interact with business strategies in general, and entrepreneurial activities more specifically (Teece, Citation2018; Teece et al., Citation2016) may benefit from understanding a firm’s innovation culture as well. When employees share a common mindset around innovation, they will likely view organizational strategies and goals through a similar lens, and therefore may understand and implement the strategy in a way that enhances both capability development and innovation performance.

Third, as ample evidence in the literature suggests, HR practices should first be transformed into organizational-level capabilities like organizational ambidexterity to improve organizational performance (Collins & Smith, Citation2006; Lin & Wu, Citation2014; Wei & Lau, Citation2010; Wu, Citation2007). The results of this study confirm that HPWS play a key role in the formation and development of DCs at the organizational level, which in turn leads to higher innovation performance. Therefore, our results support the theory that by implementing HPWS, organizations can transform organizational resources into DCs to improve innovation performance. As future research continues to explore the ‘black box’ between HPWS and organizational outcomes the role of DCs will move from a theoretical perspective to become more prominent in the empirical tests of these relationships.

Implications for practice

Our findings have important implications for managers in general and those working in pharmaceutical companies, in particular. In the face of frequent regulatory and technological changes (Narayanan et al., Citation2009), as well as environmental shocks (e.g. Covid-19 pandemic) and demands from multiple stakeholders (e.g. patients, regulators, shareholders, etc…), pharmaceutical firms need to develop capabilities that allow them to access and absorb external knowledge, as well as integrate it with existing knowledge. In this vein, our findings provide insights for pharmaceutical managers to direct investments beyond only R&D to benefit from their HR systems, thereby developing DCs and improving innovation. HPWS provide a more flexible approach to HRM than control-based approaches, enabling firms to reconfigure existing resources in the face of environmental constraints. Hence, managers working in contexts similar to those examined in this study should consider how their HR systems support the development of organizational capabilities.

In addition, the development of a stronger innovation culture facilitates the activities needed for innovation within an organization. Managers should promote an organizational culture that fits its goals and meets the demands of the organization’s competitive environment. When innovation performance is imperative to the organization, successful firms enact cultural norms to strengthen their innovation capability (Boada-Cuerva et al., Citation2019). Leaders can develop a strong innovation culture by encouraging risk-taking within a psychologically safe environment where employees feel comfortable offering new ideas and giving and receiving constructive feedback. Constructive dialogue within teams would assist individuals in integrating different pools of knowledge in search of innovative solutions (Park et al., Citation2019). Given the dynamic nature of the pharmaceutical industry (Min et al., Citation2017), creating a collaborative atmosphere can be extremely influential in motivating employees to generate new ideas and be more creative.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that warrant additional discussion. First, although we assessed the perceptions of executives and managers, we did not measure lower-level employees’ perspectives on the effectiveness of HPWS. Therefore, a potential area for future research may be to examine employees’ perceptions of HPWS, and how such perceptions relate to DCs within different organizational cultures. Second, we tested our hypotheses in the Iranian pharmaceutical industry. To increase the generalizability of the results, future studies could be conducted in other settings. For example, the highly skilled workforce in these firms can be a good fit for the implementation of HPWS. Future studies should examine the value of HPWS in organizations that rely more on efficiency and less on innovation to survive, such as companies in more stable industries. It is unclear whether the value of DCs translates in industries that are less volatile. Third, future research is needed to understand how the interconnectedness of learning, integration, and reconfiguration capabilities influences organizational outcomes. This is particularly important in relation to innovation, as many empirical studies utilizing dynamic capabilities theory have examined only one type of capability, and it would be valuable to understand whether these capabilities are not only distinct but also potentially substitutable for one another. Finally, this study occurred in the context of significant political and economic instability within Iran. While this context is certainly appropriate for testing the development and value of dynamic capabilities towards innovation performance, future research is needed to confirm our findings in other contexts not hampered by such instability.

Conclusion

Despite the existing literature on HRM and organizational outcomes, few studies have analyzed how HPWS, as a bundle of ability-, motivation-, and opportunity-enhancing practices, can improve organizational innovation performance. This study integrates the DCs perspective to discern how HR practices influence innovation performance in a knowledge-based environment. Further, this study highlights the contribution of innovation culture as a contextual factor that influence the links between HPWS, DCs, and innovation performance. Our results highlight the importance of having a shared understanding that supports how HR policies and practices are implemented toward the development of capabilities and innovation goals, and may explain why some firms outperform their peers in terms of innovation performance. Finally, this study provides insights into the role of HRM in the knowledge-intensive context of the pharmaceutical industry.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because they contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Notes

1 Consistent with the theory that DCs are stronger when all three facets are strong (relative to competitors) in an organization (Teece, Citation2018), we combined the three capabilities into a single measure of dynamic capabilities in our mediation tests. In analyses available from the authors, we examined mediation tests using each of the three dimensions of DCs separately and found significant indirect effects for each dimension.

2 We thank two anonymous reviewers and the Action Editor for this suggestion.

3 We also tested for a moderated mediation relationship using the second-stage (PROCESS model 14) moderation. The results were consistent across both models, indicating the importance of innovation culture as an overarching contextual factor. The results of the alternative models are available from the authors.

References

- Appelbaum, E., Bailey, T. A., Berg, P. B., Kalleberg, A. L., & Bailey, T. A. (2000). Manufacturing advantage: Why high-performance work systems pay off (Vol. 18). Cornell University Press.

- Arbuckle, J., & Wothke, W. (1999). Amos 4.0 user’s guide. Citeseer.

- Baía, E. P., & Ferreira, J. J. M. (2019). Dynamic capabilities and performance: How has the relationship been assessed? Journal of Management & Organization, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2019.88

- Bamberger, P. (2008). From the editors beyond contextualization: Using context theories to narrow the micro-macro gap in management research. Academy of Management Journal, 51(5), 839–846. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2008.34789630

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

- Barney, J., Wright, M., & Ketchen, D. J. (2001). The resource-based view of the firm: Ten years after 1991. Journal of Management, 27(6), 625–641. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630102700601

- Beltrán-Martín, I., Roca-Puig, V., Escrig-Tena, A., & Bou-Llusar, J. C. (2008). Human resource flexibility as a mediating variable between high performance work systems and performance. Journal of Management, 34(5), 1009–1044. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308318616

- Bliese, P. D. (2000). Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In K. J. Klein & S. W. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations (pp. 349–381). Jossey-Bass.

- Boada-Cuerva, M., Trullen, J., & Valverde, M. (2019). Top management: The missing stakeholder in the HRM literature. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(1), 63–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2018.1479878

- Bowen, D. E., & Ostroff, C. (2004). Understanding HRM-firm performance linkages: The role of the “strength” of the HRM system. Academy of Management Review, 29(2), 203–221.

- Boxall, P. (2012). High-performance work systems: What, why, how and for whom? Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 50(2), 169–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7941.2011.00012.x

- Boxall, P., & Macky, K. (2009). Research and theory on high-performance work systems: Progressing the high-involvement stream. Human Resource Management Journal, 19(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2008.00082.x

- Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910457000100301

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research, 21(2), 230–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124192021002005

- Camps, J., & Luna-Arocas, R. (2012). A matter of learning: How human resources affect organizational performance. British Journal of Management, 23(1), 1–21.

- Chadwick, C., & Flinchbaugh, C. (2021). Searching for competitive advantage in the HRM-firm performance relationship. Academy of Management Perspectives, 35(2), 181–207. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2018.0065

- Chen, M. Y. C., Lin, C. Y. Y., Lin, H. E., & McDonough, E. F. (2012). Does transformational leadership facilitate technological innovation? The moderating roles of innovative culture and incentive compensation. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 29(2), 239–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-012-9285-9

- Chiu, W. H., Chi, H. R., Chang, Y. C., & Chen, M. H. (2016). Dynamic capabilities and radical innovation performance in established firms: A structural model. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 28(8), 965–978. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2016.1181735

- Chowhan, J. (2016). Unpacking the black box: Understanding the relationship between strategy, HRM practices, innovation and organizational performance. Human Resource Management Journal, 26(2), 112–133. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12097

- Collins, C. J., & Smith, K. G. (2006). Knowledge exchange and combination: The role of human resource practices in the performance of high-technology firms. Academy of Management Journal, 49(3), 544–560. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.21794671

- De Spiegelaere, S., Van Gyes, G., & Van Hootegem, G. (2018). Innovative work behaviour and performance-related pay: Rewarding the individual or the collective? International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(12), 1900–1919. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1216873

- Dixon, S., Meyer, K., & Day, M. (2014). Building dynamic capabilities of adaptation and innovation: A study of micro-foundations in a transition economy. Long Range Planning, 47(4), 186–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2013.08.011

- Dodge, R., Dwyer, J., Witzeman, S., Neylon, S., & Taylor, S. (2017). The role of leadership in innovation. Research-Technology Management, 60(3), 22–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/08956308.2017.1301000

- Droppert, H., & Bennett, S. (2015). Corporate social responsibility in global health: An exploratory study of multinational pharmaceutical firms. Globalization and Health, 11(1), 15–18.

- Eisenhardt, K. M., Furr, N. R., & Bingham, C. B. (2010). CROSSROADS—Microfoundations of performance: Balancing efficiency and flexibility in dynamic environments. Organization Science, 21(6), 1263–1273. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0564

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Martin, J. A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal, 21(10–11), 1105–1121. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0266(200010/11)21:10/11<1105::AID-SMJ133>3.0.CO;2-E

- Fainshmidt, S., Pezeshkan, A., Lance Frazier, M., Nair, A., & Markowski, E. (2016). Dynamic capabilities and organizational performance: A meta-analytic evaluation and extension. Journal of Management Studies, 53(8), 1348–1380. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12213

- Farzaneh, M., Ghasemzadeh, P., Nazari, J. A., & Mehralian, G. (2021). Contributory role of dynamic capabilities in the relationship between organizational learning and innovation performance. European Journal of Innovation Management, 24(3), 655–676. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-12-2019-0355

- Farzaneh, M., Wilden, R., Afshari, L., & Mehralian, G. (2022). Dynamic capabilities and innovation ambidexterity: The roles of intellectual capital and innovation orientation. Journal of Business Research, 148, 47–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.04.030

- Ferris, G. R., Arthur, M. M., Berkson, H. M., Kaplan, D. M., Harrell-Cook, G., & Frink, D. D. (1998). Toward a social context theory of the human resource management-organization effectiveness relationship. Human Resource Management Review, 8(3), 235–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-4822(98)90004-3

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Gahan, P., Theilacker, M., Adamovic, M., Choi, D., Harley, B., Healy, J., & Olsen, J. E. (2021). Between fit and flexibility? The benefits of high‐performance work practices and leadership capability for innovation outcomes. Human Resource Management Journal, 31(2), 414–437. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12316

- Ghasemzadeh, P., Rezayat Sorkhabadi, S. M., Kebriaeezadeh, A., Nazari, J. A., Farzaneh, M., & Mehralian, G. (2021). How does organizational learning contribute to corporate social responsibility and innovation performance? The dynamic capability view. Journal of Knowledge Management, https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-01-2021-0069

- Gujarati, D. N. & Porter, D. (2009). Basic Econometrics. Mc Graw-Hill International Edition.

- Guthrie, J. P. (2001). High-involvement work practices, turnover, and productivity: Evidence from New Zealand. Academy of Management Journal, 44(1), 180–190. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069345

- Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 16(2), 250–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(76)90016-7

- Hahn, W. A. (1962). Applied business research. IRE Transactions on Engineering Management, EM-9(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1109/IRET-EM.1962.5007643

- Hansen, M. T., & Nohria, N. (2004). How to build collaborative advantage. MIT Sloan Management Review, 46(1), 46105.

- Helfat, C. E., & Peteraf, M. A. (2009). Understanding dynamic capabilities: Progress along a developmental path. Strategic Organization, 7(1), 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127008100133

- Hess, A. M., & Rothaermel, F. T. (2011). When are assets complementary? star scientists, strategic alliances, and innovation in the pharmaceutical industry. Strategic Management Journal, 32(8), 895–909. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.916

- Hung, R. Y. Y., Yang, B., Lien, B. Y. H., McLean, G. N., & Kuo, Y. M. (2010). Dynamic capability: Impact of process alignment and organizational learning culture on performance. Journal of World Business, 45(3), 285–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2009.09.003

- IFDA. (2017). Iran medicine records. Ministry of Health and Medical Education. https://www.fda.gov.ir/

- Ireland, R. D., Hitt, M. A., & Sirmon, D. G. (2003). A model of strategic entrepreneurship: The construct and its dimensions. Journal of Management, 29(6), 963–989. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2063(03)00086-2

- Jerez-Gómez, P., Céspedes-Lorente, J., & Pérez-Valls, M. (2019). Do high-performance human resource practices work? The mediating role of organizational learning capability. Journal of Management & Organization, 25(2), 189–210. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2017.55

- Jiang, K., Lepak, D. P., Hu, J., & Baer, J. C. (2012). How does human resource management influence organizational outcomes? A meta-analytic investigation of mediating mechanisms. Academy of Management Journal, 55(6), 1264–1294. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0088

- Johns, G. (2006). The essential impact of context on organizational behavior. Academy of Management Review, 31(2), 386–408. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.20208687

- Johns, G. (2018). Advances in the treatment of context in organizational research. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 21–46. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104406

- Kaiser, H. F. (1958). The varimax criterion for analytic rotation in factor analysis. Psychometrika, 23(3), 187–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02289233

- Kang, S. C., Morris, S. S., & Snell, S. A. (2007). Relational archetypes, organizational learning, and value creation: Extending the human resource architecture. Academy of Management Review, 32(1), 236–256. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.23464060

- Katou, A. A., & Budhwar, P. S. (2010). Causal relationship between HRM policies and organisational performance: Evidence from the Greek manufacturing sector. European Management Journal, 28(1), 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2009.06.001

- Kehoe, R. R., & Wright, P. M. (2013). The impact of high-performance human resource practices on employees’ attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Management, 39(2), 366–391. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310365901

- Khanna, I. (2012). Drug discovery in pharmaceutical industry: Productivity challenges and trends. Drug Discovery Today, 17(19–20), 1088–1102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2012.05.007

- Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. (4th ed.). Guilford Press.

- Lepak, D. P., Liao, H., Chung, Y., & Harden, E. E. (2006). A conceptual review of human resource management systems in strategic human resource management research. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 25(6), 217–271.

- Lin, B.-W., & Chen, C.-J. (2006). Fostering product innovation in industry networks: The mediating role of knowledge integration. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17(1), 155–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190500367472

- Lin, Y., & Wu, L.-Y Y. (2014). Exploring the role of dynamic capabilities in firm performance under the resource-based view framework. Journal of Business Research, 67(3), 407–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.12.019

- Li-Yun, S., Aryee, S., Law, K. S., Sun, L., Aryee, S., & Law, K. S. (2007). High-performance human resource practices, citizenship behavior, and organizational performance: A relational perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 50(3), 558–577.

- Marin-Garcia, J. A., & Tomas, J. M. (2016). Deconstructing AMO framework: A systematic review. Intangible Capital, 12(4), 1040–1087. https://doi.org/10.3926/ic.838

- Martín-de Castro, G., Delgado-Verde, M., Navas-López,, J. E., & Cruz-González, J. (2013). The moderating role of innovation culture in the relationship between knowledge assets and product innovation. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 80(2), 351–363.

- Mehralian, G., Moosivand, A., Emadi, S., & Asgharian, R. (2017). Developing a coordination framework for pharmaceutical supply chain: Using analytical hierarchy process. International Journal of Logistics Systems and Management, 26(3), 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJLSM.2017.081961

- Mehralian, G., Moradi, M., & Babapour, J. (2021). How do high-performance work systems affect innovation performance? The organizational learning perspective. Personnel Review. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-08-2020-0617

- Min, M., Desmoulins-Lebeault, F., & Esposito, M. (2017). Should pharmaceutical companies engage in corporate social responsibility? Journal of Management Development, 36(1), 58–70. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-09-2014-0103

- Minbaeva, D. B. (2005). HRM practices and MNC knowledge transfer. Personnel Review, 34(1), 125–144. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480510571914

- Minbaeva, D. B. (2013). Strategic HRM in building micro-foundations of organizational knowledge-based performance. Human Resource Management Review, 23(4), 378–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2012.10.001

- Narayanan, V. K., Colwell, K., & Douglas, F. L. (2009). Building organizational and scientific platforms in the pharmaceutical industry: A process perspective on the development of dynamic capabilities. British Journal of Management, 20, S25–S40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2008.00611.x

- O’Cass, A., & Ngo, L. V. (2007). Market orientation versus innovative culture: Two routes to superior brand performance. European Journal of Marketing, 41(7–8), 868–887.

- O’Reilly, C. A., & Tushman, M. L. (2008). Ambidexterity as a dynamic capability: Resolving the innovator’s dilemma. Research in Organizational Behavior, 28, 185–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2008.06.002

- Obeidat, S. M., Mitchell, R., & Bray, M. (2016). The link between high performance work practices and organizational performance: Empirically validating the conceptualization of HPWP according to the AMO model. Employee Relations, 38(4), 578–595. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-08-2015-0163

- Ogbonnaya, C., & Valizade, D. (2018). High performance work practices, employee outcomes and organizational performance: A 2-1-2 multilevel mediation analysis. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(2), 239–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1146320

- Park, J., Lee, K. H., & Kim, P. S. (2016). Participative management and perceived organizational performance: The moderating effects of innovative organizational culture. Public Performance & Management Review, 39(2), 316–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2015.1108773

- Park, O., Bae, J., & Hong, W. (2019). High-commitment HRM system, HR capability, and ambidextrous technological innovation. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(9), 1526–1548. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1296880

- Patel, P. C., Messersmith, J. G., & Lepak, D. P. (2013). Walking the tightrope: An assessment of the relationship between high-performance work systems and organizational ambidexterity. Academy of Management Journal, 56(5), 1420–1442. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0255

- Porrini, P. (2004). Can a previous alliance between an acquirer and a target affect acquisition performance? Journal of Management, 30(4), 545–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jm.2004.02.003

- Prieto, I. M., & Santana, P. P. M. (2012). Building ambidexterity: The role of human resource practices in the performance of firms from Spain. Human Resource Management, 51(2), 189–211. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21463

- Rasheed, M. A., Shahzad, K., Conroy, C., Nadeem, S., & Siddique, M. U. (2017). Exploring the role of employee voice between high-performance work system and organizational innovation in small and medium enterprises. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 24(4), 670–688. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-11-2016-0185

- Saridakis, G., Lai, Y., & Cooper, C. L. (2017). Exploring the relationship between HRM and firm performance: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Human Resource Management Review, 27(1), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2016.09.005

- Seeck, H., & Diehl, M. R. (2017). A literature review on HRM and innovation–taking stock and future directions. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(6), 913–944. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1143862

- Shahzad, K., Arenius, P., Muller, A., Rasheed, M. A., & Bajwa, S. U. (2019). Unpacking the relationship between high-performance work systems and innovation performance in SMEs. Personnel Review, 48(4), 977–1000. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-10-2016-0271

- Shalley, C. E., & Gilson, L. L. (2004). What leaders need to know: A review of social and contextual factors that can foster or hinder creativity. Leadership Quarterly, 15(1), 33–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2003.12.004

- Shipton, H., Sparrow, P., Budhwar, P., & Brown, A. (2017). HRM and innovation: Looking across levels. Human Resource Management Journal, 27(2), 246–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12102

- Shipton, H., West, M. A., Dawson, J., Birdi, K., & Patterson, M. (2006). HRM as a predictor of innovation. Human Resource Management Journal, 16(1), 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2006.00002.x

- Song, W., Yu, H., & Qu, Q. (2018). High involvement work systems and organizational performance: The role of knowledge combination capability and interaction orientation. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(7), 1–25.

- Soo, C., Tian, A. W., Teo, S. T. T., & Cordery, J. (2017). Intellectual capital-enhancing HR, absorptive capacity, and innovation. Human Resource Management, 56(3), 431–454. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21783

- Subramaniam, M., & Youndt, M. A. (2005). The influence of intellectual capital on the types of innovative capabilities. Academy of Management Journal, 48(3), 450–463. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2005.17407911

- Sung, S. Y., & Choi, J. N. (2018). Effects of training and development on employee outcomes and firm innovative performance: Moderating roles of voluntary participation and evaluation. Human Resource Management, 57(6), 1339–1353. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21909

- Tasavori, M., Eftekhar, N., Mohammadi Elyasi, G., & Zaefarian, R. (2021). Human resource capabilities in uncertain environments. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(17), 1–27.

- Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(13), 1319–1350. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.640

- Teece, D. J. (2018). Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Planning, 51(1), 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2017.06.007

- Teece, D. J., Peteraf, M., & Leih, S. (2016). Uncertainty, innovation, and dynamic capabilities: An introduction. California Management Review, 58(4), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2016.58.4.5

- Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199708)18:7<509::AID-SMJ882>3.0.CO;2-Z

- Teece, D., Peteraf, M., & Leih, S. (2016). Dynamic capabilities and organizational agility: Risk, uncertainty, and strategy in the innovation economy. California Management Review, 58(4), 13–35. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2016.58.4.13

- Tian, M., Deng, P., Zhang, Y., & Salmador, M. P. (2018). How does culture influence innovation? A systematic literature review. Management Decision, 56(5), 1088–1107. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-05-2017-0462

- Van Esch, E., Wei, L. Q., & Chiang, F. F. T. (2018). High-performance human resource practices and firm performance: The mediating role of employees’ competencies and the moderating role of climate for creativity. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(10), 1683–1708. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1206031

- Wang, T., & Zatzick, C. D. (2019). Human capital acquisition and organizational innovation: A temporal perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 62(1), 99–116. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2017.0114

- Way, S. A., Tracey, J. B., Fay, C. H., Wright, P. M., Snell, S. A., Chang, S., & Gong, Y. (2015). Validation of a multidimensional HR flexibility measure. Journal of Management, 41(4), 1098–1131. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312463940

- Wei, L.-Q., & Lau, C.-M. (2010). High performance work systems and performance: The role of adaptive capability. Human Relations, 63(10), 1487–1511. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709359720

- Wei, L.-Q., Liu, J., & Herndon, N. C. (2011). SHRM and product innovation: Testing the moderating effects of organizational culture and structure in Chinese firms. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.538965

- Wilden, R., Devinney, T. M., & Dowling, G. R. (2016). The architecture of dynamic capability research identifying the building blocks of a configurational approach. Academy of Management Annals, 10(1), 997–1076. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2016.1161966

- Wu, H., Chen, J., & Jiao, H. (2016). Dynamic capabilities as a mediator linking international diversification and innovation performance of firms in an emerging economy. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 2678–2686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.11.003

- Wu, L. Y. (2007). Entrepreneurial resources, dynamic capabilities and start-up performance of Taiwan’s high-tech firms. Journal of Business Research, 60(5), 549–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.01.007

- Yalcinkaya, G., Calantone, R. J., & Griffith, D. A. (2007). An examination of exploration and exploitation capabilities: Implications for product innovation and market performance. Journal of International Marketing, 15(4), 63–93. https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.15.4.63

- Zahra, S. A., & George, G. (2002). The net-enabled business innovation cycle and the evolution of dynamic capabilities. Information Systems Research, 13(2), 147–150.

- Zhou, K. Z., & Wu, F. (2009). Technological capability, strategic flexibility, and product innovation. Strategic Management Journal, 31(5), 547–561.

- Zollo, M., & Winter, S. G. (2002). Deliberate learning and the evolution of dynamic capabilities. Organization Science, 13(3), 339–351. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.13.3.339.2780