?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This research investigates students’ transferable skills in an integrating blended learning environment, specifically addressing writing skills. Drawing on Biggs’ application of constructivism theory, the study analyses students’ characteristics, perception of the designed teaching methods, and confidence in their writing skills. The study context was a suite of accounting and finance programmes in the United Kingdom. 164 student participants answered questionnaires, from among whom focus group participants were organised. A mixed research method was adopted to clarify the drivers of the active learning process. The findings reveal that students’ characteristics influence perceptions, and that a well-designed blended learning method can alter their perceptions and improve students’ writing skills. The study contributes to the literature on blended learning by providing evidence of its positive impact on the students’ learning process and performance. The findings encourage accounting educators to develop strategies to improve students’ performance in transferable skills through an appropriate learning design.

1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence, complex platforms, and other significant changes associated with Industry 4.0Footnote1, have increased the demand for a workforce capable of applying an extensive range of transferable skills, including proficient written and oral communication skills (IBA Global Employment Institute, Citation2017). This study focuses specifically on accounting and finance students’ writing skills, considering how deficits might be improved with the application of a blended learning approach. Although in recent decades, transferable skills have become part of the job readiness strategy within higher education (HE) worldwide, there are concerns that graduates from technical programmes continue to struggle to meet the requirements of industry (Kavanagh & Drennan, Citation2008). A review conducted by Riley and Simons (Citation2013), including 100 published articles pertaining to accounting, demonstrated that accounting students, who may assume exhibiting good numeracy and technical knowledge sufficient to guarantee a professional position, generally do not perceive writing skills as important. This assumption is erroneous, since accounting profession is no longer a purely technical domain, as consultancy and advisory roles, which demand excellent communication skills, are now vital (De Villiers, Citation2010; Kermis & Kermis, Citation2010). This ongoing debate concerning writing skills and the future employability of accounting graduates requires higher awareness among accounting educators in shaping modules and teaching approaches that facilitate the acquisition of these particular skills.

Moore and Morton (Citation2017) suggested that the principal aim in writing is not the achievement of an adequate level of basic skill, rather the ability to use those skills dynamically. That is, to express knowledge, reflect on specific topics (Moore & Hough, Citation2005), and develop critical thinking skills (Taylor, Citation2000). Moore and Morton’s (Citation2017) findings address the conceptualisation of ‘writing as a process’ (Flower & Hayes, Citation1981), and describe the critical literacy approach, in which a cognitive view of writing is employed (Luke, Citation2000). Creating a more dynamic approach to writing facilitates students in developing invaluable transferable skills for graduate roles.

Applying Biggs's approach to constructivist theory, this paper investigates the application of a blended learning method, combining teacher-controlled and self-controlled activities to enhance writing skills. Biggs (Citation1999, p. 61) argues that ‘learning is the result of students’ learning-focused activities which are taken by students as a result both of their own perceptions and inputs and of the total teaching context’. The learning process is interactive and ‘the learner brings an accumulation of assumptions, motives, intentions, and previous knowledge that envelopes every teaching/learning situation and determines the course and quality of the learning that may take place’ (Biggs, Citation1996, p. 348).

Additionally, Biggs (Citation1993) clarifies that the teacher context and related activities, i.e. teacher-controlled, peer-controlled, and self-controlled, play a significant role in engaging students and motivating them to learn. Combining these activities is particularly effective in a blended approach, and is supported extensively in the literature, which also demonstrates the positive impact of regular online activity on learning outcomes (for example, Angus & Watson, Citation2009; Gikandi et al., Citation2011; Stull et al., Citation2011). The integrated blended learning environment supports a constructive approach to learning, as ‘the emphasis must shift from assimilating information to constructing meaning and confirming understanding in a community of inquiry’ (Garrison & Kanuka, Citation2004, p. 98).

Based on these assumptions, for this study, a blended learning approach for developing students` writing skills was applied to a first year module (Personal and Professional Development) within the Accounting and Finance Programme. The students’ traits were considered when evaluating the effectiveness of the blended approach, with an emphasis on their pre-existing perceptions of their skills and the teaching context. The data was gathered from 164 first year accounting and finance students using questionnaires and focus groups before and after a blended learning experience. Information regarding the students’ performance, and their learning approach in the integrated blended environment, was also collected via an online educational platform. The analysis reveals that students generally overestimate their abilities. In addition, students’ learner characteristics, work experience, and previous blended learning experiences, affect their perceptions of the teaching method, and their confidence in their writing skills. The findings also illustrate that the students’ levels of confidence in their writing skills and level of performance shifted, demonstrating the value of a well-designed learning process (Biggs, Citation2011).

This study offers a valuable contribution to the existing educational literature. By examining the students’ learner characteristics and their pre-existing perceptions regarding methods for teaching transferable skills, it demonstrates how perceived pre-existing knowledge (writing skills) and teaching activities applied (blended learning) influence their performance. The findings support using a blended learning environment to develop self-controlled activities (Biggs, Citation1996), enhance performance, and clarify students’ perceptions of the skills they have acquired. Evidence is provided of the effectiveness of the blended learning approach as an applicable learning design that can be applied to develop transferable skills in technical programmes. Additionally, this study provides a model for further research into transferable skills, assisting Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) to reformulate or improve related teaching strategies.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a literature review; Section 3 presents the research questions and discusses the methodology and sample; Section 4 analyses the empirical findings; and Section 5 draws conclusions, discusses the limitations of the study, and suggests areas for future research.

2. Literature review

2.1. The writing process

The writing process describes the conscious use of language in a specific context to convey one's ideas (Kelly et al., Citation2004). According to Eves-Bowden (Citation2001), enhancing students’ competence in writing requires a learning process that enables a gradual switch from ‘knowledge telling’ to ‘knowledge transforming’. As Moore and Morton affirmed, this requires the application of a tailored teaching method to facilitate teacher/learner interaction and knowledge construction (Alkhatib, Citation2018). Moore and Morton (Citation2017) called for a switch from the traditional teaching model that considers learning to be a process in which knowledge and skills are accumulated, to a teaching model based on individual students actively constructing their own knowledge and applying it for their own purposes (Biggs, Citation1996).

2.2. Constructivism theory and the Biggs's learning process model

Cognitive constructivism provides a theory of knowledge, which acknowledges that the learner brings prior information and experiences arising from their former cultural and social experiences (Piaget, Citation1971). According to Piaget’s (Citation1953) theory of cognitive development, the learning process is a consequence of exploration and the construction of meaning and processing of information to construct an understanding within a particular environment (Pritchard & Woollard, Citation2010). When applying constructivist theory to enhance the student learning process, Biggs (Citation1993) developed his own theoretical framework, arguing that learning does not occur in a vacuum but is profoundly influenced by the learning environment. Applying Dunkin and Biddle’s (Citation1974) presage-process and product model, Biggs (Citation1993) developed a model of the student learning process that moves linearly from presage to process and product in an interactive system.

2.2.1. Student presage factor

According to the constructivist view, student presage factors can be identified as a combination of ‘personal, academic and social/emotional characteristics that may influence how and what [an individual] learn[s]’ (Kirschner & Drachsler, Citation2012, p. 1743). These characteristics have been widely investigated, in order to understand how students differ according to their personal characteristics, such as demographic factors including socioeconomic status, age, gender, and ethnicity (Lemke et al., Citation2004; OECD, Citation2014); academic characteristics, such as prior knowledge (Elliot & Dweck, Citation1988; Lee et al., Citation2015); and socio-emotional characteristics, such as beliefs and prior experience (Jonassen, Citation2000).

2.2.2. Teaching presage factor

Teaching presage factors relate to the teaching context and include teachers’ personal characteristics and the teaching design applied within the module structure, curriculum content, and methods of teaching and assessment. Biggs (Citation1999) clarifies how ‘good teaching’ relates to understanding which learning related aspects are controllable and devising learning activities that students approach in a manner likely to ensure they achieve the target teaching and learning objectives. Biggs (Citation1999) identifies teaching and learning activities according to whether they are teacher controlled (lectures, tutorials, laboratories, field excursions, etc.), peer dependent (such as groupwork), or self-controlled (independent learning and study actions). Self-controlled activities develop within and in reference to a specific teaching context and therefore teachers must embed students learning/study skills into teaching design (Biggs, Citation1996).

2.2.3. Learning process and the product of learning

The learning process connects student and teaching presage factors with performance. Biggs (Citation1996) identifies two main approaches to learning: deep and surface. A deep approach is task-centred and task-appropriate; i.e. students perform independent activities that are appropriate to handling the task, so a desired outcome is achieved. The surface approach relies on minimisation of student effort to complete the assigned task and obtain a pass. These approaches are not imposed or transmitted by direct instruction but can be supported by training and developing self-controlled activities via an effective teaching context.

Academic performance can be evaluated quantitatively and is typically expressed in grades (Trigwell & Prosser, Citation1996). Affective outcomes refer to students’ feelings about the learning process (Biggs, Citation1996) and are often evaluated by perception of knowledge gained at the end of the course.

2.3. Active teaching and learning process for transferable skills

Biggs’ learning model drives the learning process (Hall, Citation2011), creating continued growth and adjustments in the individual's knowledge and approach (Biggs, Citation1999). The pitfalls of an active learning process are the need for awareness and conscious participation on the part of the learner, as well as previous knowledge and experience (Alkhatib, Citation2018). For a teaching and learning environment to be successful students must exhibit a clear awareness of task demands and how they can be met, and an ability to exert control over their own learning process. Hence, the process of acquiring writing skills at university level is affected by a combination of students’ learner characteristics, their level of perception and motivation, and the teaching method employed. The level of students` perceptions when approaching a new learning environment and process, particularly in the case of first year students, might significantly impact learning outcomes, particularly in terms of written communication skills.

New cohorts of students possess their own perceptions of the skills and knowledge acquired, and the teaching method employed, which may then affect what they expect to gain from future experiences (Beaty et al., Citation1997). In this study, the students are in the initial stages of their university journey, and have their own beliefs about learning, derived from their previous experience (Hall et al., Citation2004). Additionally, as Biggs (Citation1996) notes, the learning process is also influenced by the teaching context. The effectiveness of the active teaching process requires a ‘meeting of awareness’ (Entwistle, Citation2012), in which teachers shape the teaching context so it enhances their students’ learning process. This ‘meeting of awareness’ facilitates the adoption of an appropriate teaching design and context, that can deliver ‘tailored instructions for a target group’ (Kirschner & Drachsler, Citation2012, p. 1743), and can be an efficient, effective, and/or motivating means of developing specific transferable skills, such as writing skills.

The teaching context applied in our study involved interactive creation of a blended learning method, wherein the teacher-controlled activity (face-to-face sessions) was integrated with self-controlled activities, regulated and structured by the teacher via an online learning platform. The aim was to facilitate instructor/student interaction and promote knowledge construction in class activities, in line with constructivist theory (Alkhatib, Citation2018). The learning design sought to promote an in-depth approach to learning (Entwistle & Peterson, Citation2004), developing writing skills, and encouraging student autonomy where high levels of interaction with the tasks assigned are required (Biggs, Citation1999). This is particularly relevant for accounting educators, as previous research has demonstrated that in-depth learning is challenging for accounting students (Ballantine et al., Citation2008; Fox et al., Citation2010).

2.4. The blended learning method and accounting education

Accounting educators are seeking to develop students’ writing skills to meet rising industry expectations. Numerous platforms, such as Blackboard, Whiteboard, Moodle, and online teaching platforms, such as Microsoft Teams, Collaborate, and ZoomFootnote2 (Wong et al., Citation2014), are now available to HEIs, allowing them to design new teaching methods (Grabinski et al., Citation2015). These tools can be employed within various teaching models, such as e-learning, blended learning, distance learning, web-based learning, and hybrid learning (Potter, Citation2015).

In this study, an integrated blended learning method was employed, using Bonk and Graham’s (Citation2005) definition of ‘transforming blends’. In this approach, learners are active participants, constructing knowledge through dynamic interactions that would otherwise only be possible via technology. Within university programmes, there are several benefits to combining face-to-face (in person) and online learning (using self-controlled activities); i.e. to deliver academic programmes efficiently, and to improve students’ technological skills (Gonzalez-Gomez et al., Citation2016; Pellas & Kazandis, Citation2015; Warren et al., Citation2020).

The blended learning approach creates an environment that encourages students to feel responsible for their learning, as the autonomy and flexibility involved means they can choose a convenient place and time for learning (Bernard et al., Citation2014; Chen et al., Citation2014; Potter, Citation2015). The time management benefits, in terms of the flexibility of study hours, are particularly appreciated by students who are combining their studies with paid employment, to obtain the work experience necessary to enhance their curriculum vitae (Hameed et al., Citation2007; Warren et al., Citation2020). Moreover, the blended learning method can boost students’ confidence as independent learners (Venkatesh et al., Citation2003), enhancing their self-assessment abilities by using activities that provide timely, regular feedback, ultimately augmenting learning outcomes (Bernard et al., Citation2014; Gonzalez-Gomez et al., Citation2016).

The application and impact of blended learning in the context of business and accounting education has been widely investigated (Anakwe, Citation2008; Greasley et al., Citation2004; Love & Fry, Citation2006). In their study, Love and Fry (Citation2006) analysed the usefulness and perception of the e-learning environment, conducting focus groups with 36 students. They found accounting students perceived the e-learning environment as having the potential to add value to the learning process. Subsequently, through gathering data from 369 on-campus students, Basioudis and De Lange's study (Citation2009) explored the impact of blended learning activities on the teaching and learning effectiveness of undergraduate accounting students, the results of which reinforce the concept that students are more motivated to learn when taught using interactive and novel approaches.

Previous studies have also explored the implications of learner characteristics on the perception and effectiveness of blended learning in accounting education. For instance, López-Pérez et al. (Citation2013) found that perceived effectiveness of blended learning is country-dependent. They analysed data from 200 questionnaires completed by accounting students in Spain and England; their regression model found that the students based in Spain attached greater importance to the efficacy of blended learning than those in England, although the English students reported higher levels of satisfaction and performance, in terms of skills and knowledge, than their Spanish counterparts.

The literature in this area has reported mixed and inconclusive results concerning the effect of age, gender, and previous educational experience (Stonebraker & Hazeltine, Citation2004). Using data collected from 985 first year students, López-Pérez et al. (Citation2011) found that students’ perceptions of the usefulness of e-learning and their performance were influenced by their previous educational experience, but not by their gender. In another study, conducted with 1,128 students, López-Pérez et al. (Citation2013) investigated learner characteristics, in terms of subject chosen and previous educational experience, and learning approach in terms of the variables affecting performance, such as time spent on activities, and activities completed.

The majority of previous literature has investigated the effects of the blended teaching approach on enhancing transferable skills, such as problem-solving, teamwork, leadership and communication (Jackling & De Lange, Citation2009; So & Brush, Citation2009). However, no previous studies have addressed the use of a blended learning method on accounting courses for writing skills, with the aim of involving students in interactive learning and boosting their perceptions of the teaching methods. The present study sought to address this gap in the literature.

3. The study

3.1. Research design and method

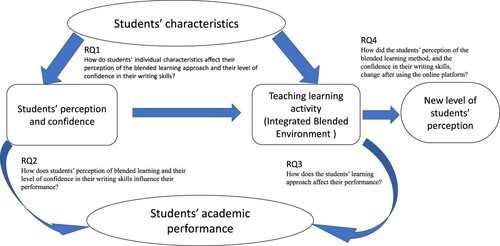

This study explores how individual characteristics can influence students’ beliefs and perceptions of their previous learning experience. We investigate how the latter can influence students’ performances in terms of writing skills. Since the learning process evolves in response to learning experiences, the study examined whether employing a new teaching design and method (blended learning environment including self-controlled activities) enhanced students’ perceptions of their learning experience, engendering a new learning approach. The research is summarised in the conceptual model presented in .

The conceptual model illustrated in prompted four research questions in this study. RQ1 and RQ2 investigate the students’ presage factors, specifically their individual characteristics and their beliefs and motives as measured by their pre-existent confidence in their writing skills, and perceptions of the teaching method employed (blended learning) when they joined the university.

RQ1: How do students’ individual characteristics affect their perception of the blended learning approach and their level of confidence in their writing skills?

RQ2: How does students’ perception of blended learning and their level of confidence in their writing skills influence their performance?

In terms of personal characteristics, previous work experience (Job) was considered to be significant, due to its potential influence on the perceived importance of writing skills for future employability. Meanwhile, academic characteristics, such as familiarity with the teaching method concerned, were assessed according to the students’ previous experience with the blended learning experience, as some previous studies suggest that familiarity with a topic/method is an effective predictor of future skills (Jonassen, Citation2000). Additionally, this study assessed the students’ preferences for a specific programme (Course) when they joined the university, which might then predict their skill level and confidence. The students had the opportunity to join different programmes, according to their secondary school achievements and preferences. Undergraduate accounting and finance programmes offer three different pathways at the same campus. The first is more accounting oriented with professional body accreditation, the second more finance focused, and the third is based on technology.

With regard to the students’ social/emotional characteristics, previous research suggests learners’ epistemic beliefs about topics and problems studied can influence their performance (Phillips, Citation2001; Schommer-Aikins et al., Citation2005). This study therefore investigated the students’ beliefs when they joined the university, using a questionnaire (see Section 3.2) to address their confidence with their writing skills (Confidence), and their perception of the blended learning experience (Perception). RQ3 and RQ4 assumed that the application of a blended learning method that boosted students’ self-controlled activities would influence their approach to learning, their perception of the teaching methods, and their knowledge of the writing process. RQ3 and RQ4 are as follows:

RQ3: How does the students’ learning approach affect their performance?

RQ4: How did the students’ perception of the blended learning method, and the confidence in their writing skills, change after using the online platform?

We focused our attention on time (Time) spent using the online platform for practice, the individual learning pathway designed according to activities assigned (Assneed), and the number of activities not completed (Needstudy) at the end of the module. The appropriate use of online teaching, in terms of time spent working on the platform, and the number of activities completed, were employed as variables to evaluate how the students approached the new learning experience.

RQ4 assumes students’ perceptions are not fixed but are instead subject to change in response to their experience (Hettich, Citation1997). The research question evaluates how the novel teaching context (a blended learning approach) influenced students’ perceptions of their writing skills. For the analysis we applied the affective outcomes from Biggs model (Citation1996) to assess students’ feelings about teaching and learning activities and, in particular, how the student's perception of their writing skills and blended learning had changed by the end of the course.

3.2. Integrated blended learning environment: My Writing Lab

The year one module, ‘Personal and Professional Development’, central to this study, had previously focused for many years on developing academic skills, such as writing skills, with the majority of learning occurring in traditional lectures and tutorials. In recent years, several changes have been made to the curriculum and the module to address academic requirements, and to develop employability skills. As the focus shifted, it was necessary to consider new ways of delivering an effective module offering a positive student experience. Consequently, a proportion of the content was moved online (30% for writing skills), employing a blended learning method to improve student engagement, and encourage opportunities for interaction and feedback (McGee & Reis, Citation2012).

The blended learning method did not reduce face-to-face contact time, rather it ensured it was used more effectively. Blended learning integrated both teaching and student's self-controlled activities in a way in which the lecturer was able to monitor the student's progress (Biggs, Citation1999). The self-controlled activities were repeatedly monitored and stimulated by the teaching staff, through linking in class work and discussion with the platform's activities. The new teaching design enabled the creation of a constructive approach to learning. These face-to-face sessions provided opportunities for feedback and critical discussion, instead of simply delivering information.

After careful consideration, the software MyWritingLab was adopted; it is based on a platform providing an individualised learning pathway to support the needs of each student. MyWritingLab is an online system designed to help students work on grammar, mechanisms, writing, and research skills. It enables students to practice persuasive, logical, and effective writing, and to identify the need for situational writing. It commences with diagnostic pre-tests that enable students to assess their current level of writing skills, providing an indication of which areas require additional work. The software is not designed specifically for accounting students, as the exercises are relatively broad in content.

In 2014, seven themes closely related to the module content were identified. However, two years later this was reduced to five themesFootnote4, with a focus on enhancing students’ critical thinking, and the planning and writing of assignments. It was decided that for each topic, three learning tools would be used: 1) Watch (including short videos); 2) Recall (unlimited access that checks the understanding of the ‘Watch’ tool and provides instant feedback); and 3) Apply, which enables students to assess and improve their writing skills by evaluating their essays and correcting errors; as with ‘Recall’, students are provided with immediate feedback, enhanced by information explaining the principles behind correct answers. Students can only access this tool once, because it is set up as a compulsory summative test.

The writing skills principles are introduced in a lecture setting at the beginning of the module, usually in week three of term one. In this introductory lecture, the online tool is demonstrated to students, who immediately engage with the online system, and explore the tools, ‘Watch’ and ‘Recall’, at home, prior to the following week's tutorial. The pace of practice throughout these two sections is determined by the individual students. In the tutorial, they are given individual and group activities to evaluate their ability to apply specific writing skills in various contexts, over a four-week period. Peer-to-peer feedback is used for individual activities, employing set criteria and marking according to a rubric provided by the tutor. The students learn from one another, and identify areas requiring further development. Student improvement is evaluated using compulsory summative tests presented on the ‘Apply’ section of MyWritingLab and spread across two terms. Upon completion, students can take a diagnostic post-test to evaluate their progress.

3.3. Sample, Instruments and Research Method

Following the receipt of ethical approval to conduct this study, 164 students were invited to participate. We organised two surveys and two forum activities. 137 students participated in survey 1 and 53 students in survey 2, while 46 from the survey 1 cohort and 18 from the survey 2 cohort took part in the two forum activities (see ). All the data was collected over the course of a single academic year, 2017–2018.

Table 1. Number of participants.

This study employed a mixed methods approach, defined as ‘a method of collecting, interpreting and integrating quantitative data and qualitative evidence by using distinct designs that may involve philosophical assumptions and theoretical frameworks’ (Creswell, Citation2014, p. 4). The chief characteristic of this approach is its ability to provide in-depth and systematic analysis of the research problem. The analysis of the data gathered for the present study was based on the results of two questionnaires involving closed–ended questions, and data from the online lab (quantitative). In addition, data was collected from six focus groups, categorised into two forums (qualitative).

The questionnaire employed for this study was developed based on the authors’ expert knowledge of the study environment and the students. Previous studies have applied general questionnaires to evaluate the student learning process from a mechanistic perspective. However, as the analysis conducted investigates a specific context and different aspects of the learning process (Biggs, Citation1999), general questionnaires could deliver inappropriate results (Choy et al., Citation2016). The coherence of the questionnaires relative to the specific context investigated was validated by the teaching team.

The two questionnaires were designed to answer the research questions in groups to indicate the learning process involved. Tailored to the specific context, the questions were employed to collect data concerning the students’ learner characteristics, and their level of perception of the blended learning approach and of their writing skills when joining university, and at the end of the term. The questionnaires were submitted to the participants online while the focus groups were held in class and with the help of a facilitator. The students’ responses were measured using a 5-point Likert response format, in which 5 = strongly agree, 4 = agree, 3 = neutral, 2 = disagree, and 1 = strongly disagree. Their answers were then coded to anonymize the responses after checking the data for accuracy. An inter-rater reliability test was performed, using Cohen's kappa (Citation1960) to improve the precision of the data, regardless of whether the correlation between the variables proved statistically significant. Finally, the specific structures of the surveys were integrated into the students’ discussion during the focus groups to add robustness to the results.

After collecting the data, a score was calculated based on the sum of the values attributed to each question, to capture both the students’ perceptions of their previous blended learning experience and their confidence in their writing skills. The data collected from MyWritingLab was then used to test the students’ performance, and their approach to the new learning experiences, in terms of performance and time. Conclusively, the evolution of the students’ perception of the blended learning approach, and their confidence in their writing skills was triangulated, utilising the student forums that occurred in terms one and two to analyse the changes in the students’ opinions over the course of the year, as their use of the online platform progressed.

According to the work design, the research questions were tested according to the following models:

RQ1

Model 1

Model 2

Models 1 and 2 provided information to answer the first research question, regarding how students’ pre-existing learner characteristics affect their perception of the blended learning method, and their confidence in their writing skills. Perception and confidence are measured by scores based on the students’ responses. Model 1 evaluated how students’ perceptions of the effectiveness of blended learning upon joining the university were affected by learner characteristics, such as gender, previous education, and preference in terms of the programme joined. Additionally, characteristics concerning the specific variables investigated, such as work, and the blended learning experience were assessed. Model 2 investigated whether the students’ levels of confidence, as measured based on their answers, were affected by their individual learner characteristics, i.e. gender, personal preference (such as programme preference), beliefs, and previous countries of education.

‘Perception’ was used to represent the students’ perception of their past experiences, as measured by their responses to the first survey. ‘Course’ indicated the programmes to which the students belonged. ‘Gender’ was used as a dummy variable, identifying alternative gender characteristics. ‘Job’, highlighting whether a student had previous employment, and ‘Blendexp’, identifying previous experience with blending learning and teaching, were both dummy variables. Due to the diverse nature of the cohort, ‘Edu’ was included as an additional dummy variable, scored as 1 if a student's education had previously occurred in the UK, or 0 if elsewhere.

RQ2

Model 3

Model 3 addressed the second research question; it investigated whether the students’ performance related to their perception and confidence. ‘Performance’ described the overall grades achieved by the students in MyWritingLab. ‘Perception’ represented the students’ perception of their former experiences, as measured using their answers to the first survey. ‘Confidence’ represented the students’ confidence in their writing skills.

RQ3

Model 4

Model 4 addressed the third research question, investigating whether the students’ learning approaches (in-depth or surface learning) related to their learning performance. ‘Performance’ described the overall grade achieved by students in MyWritingLab. ‘Time’ captured the amount of time each student spent on the practice. ‘Assneed’ included the items to be studied by the students, as measured by the results for the initial test on MyWritingLab. ‘Needstudy’ showed the items the students had not covered, even where assigned by the system. Definitions and measures for these variables are detailed in .

Table 2. Definitions of the variables used in the analysis.

The four models were supported by the students’ views, which were collected during the focus groups.

RQ4 was addressed by implementing a twofold approach. Firstly, an in-depth discussion of survey responses concerned the students’ change in perception, and therefore in their level of awareness of blended learning and of their writing skills. Secondly, the students’ opinions collected via the focus groups were used to analyse whether an integrated blended learning environment had influenced their beliefs (Lim & Morris, Citation2009), namely their level of perception of the blended learning method and their confidence in their writing skills.

4. Findings and discussion

4.1. RQ1: how do students’ individual characteristics affect their perception of the blended learning approach and their level of confidence in their writing skills?

According to the data collected, it was possible to identify the participants’ different socio-economic characteristics. The cohort consisted of 42% (n = 52) females and 58% (n = 72) males, 71% of whom had previously undertaken either part-time or full-time work experience (n=88). Due to the particular transferrable skills investigated in this study, it was deemed important to understand the participants’ educational experience by country (UK secondary education institution, or a non-UK institution). According to López-Pérez et al. (Citation2013), students’ perception is influenced by country of origin, an observation that may be relevant to the present study, but that we adapted to ‘country of students secondary education’ due to the diversity of the student population in the UK (Penfield & Lee, Citation2010). It can be assumed that the motivation to improve writing skills may be stronger among students who did not complete their secondary education in UK. According to the data, 80% (n= 98) of the participants had previously studied at UK education institutions.

In total, 58% (n = 72) of participants stated that they had experienced a blended learning approach prior to entering university. These students were asked to answer four questions regarding their perceptions of whether using blended learning affected their grades, independence, enjoyment, and confidence. The majority responded ‘Agree’, regarding the usefulness of the method, as indicated in .

Table 3. Perceptions of blended learning.

The students expressed strong positive perceptions regarding the blended learning method, and especially evidenced its positive influence on the level of their grades (80% strongly agreed or agreed), and on independent study (80% strongly agreed or agreed). Concerning their enjoyment when using blended learning, or the influence of the method as a means to improve confidence in their studies, the answers revealed a generally positive perception. However, a high number of participants neither agreed nor disagreed (40% and 30%, respectively) with the statements, evidencing a lack of preference for the different learning methods adopted or a lack of awareness of how the blended learning methods could help them.

The students’ confidence in their writing skills was found to have developed in secondary school and is depicted in .

Table 4. Perception of writing skills.

According to the analysis presented in , approximately 50% of the participants considered themselves very confident, or confident in terms of their writing skills, and a high number of the participants (43%) were very confident or confident that they knew what was required to improve their writing skills. However, the answers also showed 38% and 47% of participants were unaware of the level of their writing skills, or how to improve them.

Firstly, we identified what percentage of males and females had work experience, a UK education and experience of blended learning (see ).

Table 5. Previous experiences by gender.

In the population examined, it was noteworthy that the males had more work experience than the females (18% vs 11%), as well as more experience with blended learning (37% vs 21%), with more also coming from UK educational institutions (46% vs 31%).

Then we identified the total number of male and female students’ choices in terms of Courses, Perception of blended learning and Confidence in their writing skills (see ).

Table 6. Other data collected by gender.

In the overall sample the predominance of males was evident in terms of experience of blended learning, and confidence regarding writing skills, with a frequency of 31%, denoting a high perception of the usefulness of blended learning, and a 52% confidence in their writing skills.

Using the Likert scale results, a score for each student's perceptions of the blended learning method was calculated, and the question of whether the students’ learner characteristics influenced their perceptions was also investigated (see ).

Table 7. Regression results for perception of blended learning.

The results demonstrate that the main factors influencing the students’ perception of their previous blended learning experiences were professional experience, and the flexibility of the learning method encountered. This confirmed that previous work and blended learning experience correlated positively with positive perception of blended learning (Blendexp, 1.37 at the 1% level, and Job, 1.93 at the 1% level). The results highlighted a negative relationship with gender (Gender, – 1.015 at 10% level), and no substantial indication emerged detailing an impact from country of education, contradicting the findings of López-Pérez et al. (Citation2013).

The regression results regarding the influence of the learner characteristic variables on students’ confidence in their writing skills are presented in .

Table 8. Regression results for confidence of blended learning.

There was no correlation observed between the students’ confidence in their writing skills and other key learner characteristics. These findings support those of previous literature that consider the learning process to be ‘an unaware process’ (Chung & Jiang, Citation1998; Frensch & Runger, Citation2003; Reber, Citation1993). The previous two analyses were supported by the students’ comments, collected during the first group forum.

It was interesting to discover that both international and home students initially assumed the writing platform was intended to support international students. Those students who entered HE from a UK educational background assumed their writing skills were adequate, contrasting with the views of lecturers and employers (Brewer et al., Citation2014). The participants’ perceptions of their skill are illustrated in the following quotations:

‘I think it's good for the international students to go through the fundamentals of English, I would say’ (F1, course 3).

‘I feel like people who are not that strong in English and writing, it helps them. For somebody else, where English isn't their first language, and they’re not quite sure how to lay things out, and they’re not quite sure of this and that, I feel like it's better for them.’ (F1, course 1)

Meanwhile, other participants stated that the approach was not beneficial for them. For instance:

‘I think for me personally, I already had those skills at the start, so it didn't really add anything to that, so I didn't find much use for that’ (F1, course 1).

4.2. RQ2: how does students’ perception of the of blended learning and level of confidence in their writing skills influence their performance?

The students’ performance was tested and compared with their perceptions of the blended learning approach, together with various aspects of their level of confidence in their writing skills, prior to using MyWritingLab, to ascertain whether perception correlated with performance (see ). As control variables for the ‘awareness’ dimensions (Perception), previous experience of blended learning/online tools (Blendexp) and UK/non-UK education (Edu) were employed.

Table 9. Regression results on performance.

The results demonstrated a negative correlation between performance and students’ previous perceptions of the blended learning method/online tools (Perception, -.005 at 5% level). In addition, performance was not correlated with confidence about how they acquired their writing skills in secondary school. These results support the findings of previous literature that students’ perceptions are not fixed, but change according to their university experience (Hettich, Citation1997; Marton et al., Citation1993).

4.3. RQ3. How does the students’ learning approach affect their performance?

To analyse the students’ learning approach when engaging in an integrated blended learning environment, data available from the MyWritingLab platform was collected. According to previous literature, students’ perceptions can impede the development of the deep learning approach that is essential for enhancing key skills (Entwistle & Peterson, Citation2004). In the model employed for the present study, the average time spent (Time), assigned study practices (Assneed), and work tasks still requiring completion (Needstudy) were used to verify specific dimensions of the ‘surface or deep approach’ to learning (Biggs, Citation1999). The more ‘time spent’ by the students practicing in MyWritingLab, on ‘assigned need study’, and the low level of ‘still needs to study’, were used as drivers of a deep learning approach from the students’ perspective. The students, who were usually confident in their skills, did not consider ‘practice’ vital to their performance (see ), as they spent less time practising, and were less willing to work on their assigned studies (producing a high ‘still needs work’ result), suggesting a superficial commitment to learning.

Table 10. Regression performance, further results.

The results illustrated that the performance of the students was positively influenced by ‘assigned need study’ (Assneed, 0.36 at 5% level), and negatively by ‘still needs study’ (Needstudy, -.032 at 5% level), implying the need for a ‘deep learning approach’ to influence students’ performance when using an online platform to enhance their writing skills. Here, the students accessed a higher level of awareness regarding the needs associated with their written communication skills. Moreover, the negative correlation between ‘still needs study’ and performance confirmed that students who were more ‘aware’ of the gaps in terms of their written communication skills employed an in-depth approach to completing the high performance tasks assigned.

Additional tests and robustness checks were performed to verify the results, the findings of which (not reported) were fully consistent with those reported in .

4.4. RQ4. How did the students’ perception of the blended learning method, and their writing skills, change after using the online platform?

Considering the results obtained in the previous analysis, it was important to evaluate how the students’ awareness changed over the course of the term, especially after using blended online tools, with a focus on the online tool. This section of the study employed the data collected as part of the second survey, which was answered by approximately 40% (n=53) of the first survey cohort. In terms of gender, 53% of the respondents were male, and 47% female; approximately 36% of the cohort had previous job experience, and 66% had previous experience of a blended learning approach to learning.

The questions and the responses to them are presented as percentages in .

Table 11. Students’ awareness of applying a blended learning approach and enhancing writing skills.

Analysis of the responses found students’ awareness had shifted following their use of an online platform over the university year. The participants’ writing ability was perceived as significant, with 64% responding positively (8% strongly agree, and 58% agree) to the following statement: ‘MyWritingLab improved my understanding of how to reflect upon, and critically analyse information I read, and how to write in a more academic style’. Additionally, 47% strongly agreed that ‘With the use of MyWritingLab, I come to most classes with a greater awareness of my writing skills’, and 38% reported being more confident with engaging in class activities (‘Using MyWritingLab increases my confidence when participating actively in a class discussion’).

These findings illustrate the importance of students understanding that good written communication skills can enhance their employability. They also suggest that software combining subject-specific content with writing skills can positively influence students’ perception of the value of transferable skills, including why they are important for their future profession. The students strongly supported the use of blended learning as part of their learning process, with 13% strongly agreeing, and 58% agreeing with the statement, ‘MyWritingLab allows for flexible learning through its easy platform’. This opinion was supported by responses to other questions concerning the significance of time management. Additionally, the majority of the participants considered their learning experience to be positive when they used the platform at home. In terms of independence and seeking help, it was interesting to note that the majority of the participants (68%) appreciated their lecturers’ assistance when using the platform, and the materials.

Therefore, overall, the students demonstrated good awareness of the blended learning method, and its impact on their learning experience, and in 50% of cases, their perception of blended learning improved following use of MyWritingLab. The students’ higher level of awareness after using MyWritingLab was also apparent in the data collected during the focus groups. As the discussions progressed, the participants increasingly acknowledged other useful outcomes associated with the online platform, in particular highlighting improvements in their writing skills as a result of using MyWritingLab, and when recognising that their writing skills had previously failed to meet academic requirements and potentially those of future employers. Moreover, the students’ reframed their initial impression that writing skills training was only necessary for international students, recognising that using the platform contributed to their own skill set, as the following quotation illustrates:

‘It helps build up your skills. It's quite generalized, as in [it offers] broader skills than you’re trying to learn.’ (F1, course 2)

‘I didn't have any A-levels that were essay-based. I hadn't forgotten how to write essays, but it was good to catch up.’ (F2, course 2)

‘Don't you think it will help just to do it just for our jobs later in life, just to keep up the skills? … … I do … ’ (F1, course 2), and

‘I think it is quite useful. If we want to apply for placements and internships, you have to do all the verbal reasoning tests, and all the tests where you have to gather information from the little bit they give you, and then select the correct answers.’ (F2, course 3)

‘It's very easy to access it. It was very true that you could access it on all platforms, even on your mobile devices, on the go, and stuff like that’. (F2, course 2)

‘I think the videos are very useful, because they just recap on things that you’ve probably forgotten, and what you learned in English.’ (F1, course 2)

5. Conclusion

The study explored the characteristics and evolution of the learning process among students on accounting and finance programmes aiming to evaluate the effectiveness of a blended learning approach in enhancing students written communication skills. Based on constructivist theory, in particular Biggs’ work on ‘student learning’ and teaching and learning enhancement (Biggs, Citation1993, Citation1996 and Citation1999), and on previous literature related to the active learning process, the research investigated how students’ characteristics (personal and academic) shape their level of perception (socio-emotional characteristics) resulting from past educational experience (secondary school), to establish if this perception influences their performance in terms of their writing skills. Additionally, since the learning process evolves relative to learning experience (Biggs, Citation1999), the study examined the effectiveness of implementing a new teaching design and method (integrated blended learning environment) to enhance students’ awareness and engender a deeper learning approach.

The findings support Biggs’ (Citation1999) view that when a student develops awareness of their ‘need to know’ in a favourable learning environment, this can enhance their knowledge and skills arising from their previous experiences and promote an improved learning approach (in-depth learning) and perception.

Our results identified a negative correlation between performance and students’ previous perceptions of the blended learning method/online tools and indicate that performance was not correlated with confidence about how students acquired their writing skills in secondary school.

Additionally, the results show how the effectiveness of the blended learning approach is correlated with the perceived benefit of flexibility and accessibility of the new learning environment and is appreciated by students with different background.

It was interesting to note that over time, the participants’ perceptions concerning the use of online tools as part of a blended learning approach shifted, as their written communication skills developed. Ultimately, therefore, the application of an integrated blended learning environment was effective for upskilling students’ writing ability, affording them an understanding of how different writing genres can improve their future career prospects.

MyWritingLab was successfully adopted with this cohort of accounting and finance students. Moreover, those who engaged with the tool improved their written communication and performed better in other parts of the module. Their success was shared across the faculty, and with transnational education partners in Asia. For other HEIs considering adopting this tool, or other similar tools, it is strongly advised that an approach involving clustering the themes of the module should be employed, in order that deadlines be spaced out, allowing students to plan their study paths in a personalised way.

The findings presented in this study are relevant to different fields of research in accounting education. First, identification of the positive influence of a tailored learning experience, based on an in-depth knowledge of the students’ learner characteristics, contributes to the current debate regarding the transferable skills gap experienced by accounting students specifically, and students on technical skills programmes more generally. Future research may explore the importance of the ‘meeting of awareness’, in which educators tailor their activities according to students’ learner characteristics and needs. Students from Generation Y require a high degree of flexibility and accessibility for learning activities, as well as an approach to learning tailored to their needs. Secondly, this study contributes to the literature regarding innovative accounting teaching designs and methods, and the blended learning approach, demonstrating the positive implications that arise when using an interactive blended learning environment, in which students engage with online learning platforms, achieving greater in-depth learning and improving their performance in summative assessments. Finally, this study contributes to the literature concerning transferable skills, delivering evidence of how the use of these skills in a context such as accounting can change students’ awareness of its significance to their future career. Future research may explore transferable skills further in the context of how new and advanced teaching methods can be tailored to suit students’ learner characteristics. It would also be of interest to analyse whether differences exist between various programmes of study and transnational education offerings. This study assists HEIs in wishing to reformulate, or improve, their teaching strategies in the field of transferable skills, which is especially important in the current Covid-19Footnote5 era, as universities are being forced to pivot in this direction.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 This phenomenon will be the most powerful driver of innovation over the next few decades triggering the next wave of innovation. Thus, the main features related to the Industry 4.0 such as real-time capability, interoperability and the horizontal and vertical integration of production systems through ICT systems, are regarded to be the response to current challenges that companies must face to stay competitive in terms of globalisation and intensification of competitiveness, the volatility of market demands, shortened innovation and product life-cycles and the increasing complexity around products and processes (Kaggermann, Citation2015).

2 Many such products are available; the naming of these as examples does not imply that they are any better than the others.

3 British schools overseas are accredited by the UK government on the basis of UK standards, but it is recognized that they must follow the laws of the country in which they operate.

4 Due to changes in the university's assessment policy.

5 The pandemic 2020 – 2021.

References

- Alkhatib, O. J. (2018). An interactive and blended learning model for engineering education. Journal of Computers in Education, 5(1), 19–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-018-0097-x

- Anakwe, B. (2008). Comparison of student performance in paper-based versus computer-based testing. Journal of Education for Business, 84(1), 13–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.84.1.13-17

- Angus, S. D., & Watson, J. (2009). Does regular online testing enhance student learning in the numerical sciences? Robust evidence from a large data set. British Journal of Educational Technology, 40(2), 255–272. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2008.00916.x

- Ballantine, J., Duff, A., & Larres, P. (2008). Accounting and business students’ approaches to learning: A longitudinal study. Journal of Accounting Education, 26(4), 188–201. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccedu.2009.03.001

- Basioudis, I., & De Lange, P. (2009). An assessment of the learning benefits of using a web-based learning environment when teaching accounting. Advances in Accounting, 25(1), 13–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adiac.2009.02.008

- Beaty, E., Gibbs, G., & Morgan, A. (1997). Learning orientations and study contracts. In F. Marton, D. J. Hounsell, & N. J. Entwistle (Eds.), The experience of learning 2nd ed. (pp. 72–88). Scottish Academic Press.

- Bernard, M. B., Borkhovski, E., Schmid, R. F., Tamin, R. M., & Abrami, P. C. (2014). A meta-analysis of blended learning and technology use in higher education; from general to applied. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 26(1), 87–122. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-013-9077-3

- Biggs, J. B. (1993). From theory to practice: A cognitive systems approach. Higher Education Research and Development, 12(1), 73–85. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436930120107

- Biggs, J. B. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Higher Education, 32(3), 347–364. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00138871

- Biggs, J. B. (1999). What the student does: Teaching for enhanced learning. Higher Education Research and Development, 18(1), 57–75. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436990180105

- Biggs, J. B. (2011). Teaching for quality learning. SRHE and Open University Press.

- Bonk, C., & Graham, C. (2005). Handbook of blended learning: Global perspectives, local designs (4th ed.). Pfeiffer Publishing.

- Brewer, P. C., Sorensen, J. E., & Stout, D. E. (2014). The future of accounting education: Addressing the competency crisis. Strategic Finance, 96(2), 29–38.

- Chen, Y., Wang, Y., & Chen, N. S. (2014). Is FLIP enough? Or should we use the FLIPPED model instead? Computers and Education, 79, 16–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.07.004

- Choy, S. C., Goh, P. S. C., & Sedhu, D. S. (2016). How and why students learn: Development and validation of the learner awareness levels questionnaire for higher education students. International Journal for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 28(1), 94–101.

- Chung, M. M., & Jiang, Y. (1998). Contextual cueing: Implicit learning and memory of visual context guides spatial attention. Cognitive Psychology, 36(1), 28–71. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1006/cogp.1998.0681

- Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/001316446002000104

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (4th ed). Sage Publications Ltd.

- De Villiers, R. (2010). The incorporation of soft skills into accounting curricula: Preparing accounting graduates for their unpredictable futures. Meditari Accountancy Research, 18(2), 1–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/10222529201000007

- Dunkin, M, & Biddle, B. (1974). The study of teaching. Holt: Rinehart and Winston.

- Elliot, E. S., & Dweck, C. S. (1988). Goals: An approach to motivation and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.1.5

- Entwistle, N. J. (2012). The quality of learning at university: Integrative understanding and distinctive ways of thinking. In J. Kirby & M. Lawson (Eds.), Enhancing the quality of learning: Dispositions, instruction, and learning processes (pp. 15–31). Cambridge.

- Entwistle, N. J., & Peterson, E. R. (2004). Conceptions of learning and knowledge in higher education: Relationships with study behaviour and influences of learning environments. International Journal of Education Research, 41(6), 407–428. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2005.08.009

- Eves-Bowden, A. (2001). What basic writers think about writing. Journal of Basic Writing, 20(2), 71–87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.37514/JBW-J.2001.20.2.07

- Flower, L., & Hayes, J. R. (1981). A cognitive process theory of writing. College Composition and Communication, 32(4), 365–387. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/356600

- Fox, A., Stevenson, L., Connelly, P., Duff, A., & Dunlop, A. (2010). Peer-mentoring undergraduate accounting students: The influence on approaches to learning and academic performance. Active Learning in Higher Education, 11(2), 145–156. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787410365650

- Frensch, P. A., & Runger, D. (2003). Implicit learning. Current Direction in Political Science, 12(1), 13–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.01213

- Garrison, D. R., & Kanuka, H. (2004). Blended learning: Uncovering its transformative potential in higher education. Internet and Higher Education, 7(2), 95–105. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2004.02.001

- Gikandi, J. W., Morrow, D., & Davis, N. E. (2011). Online formative assessment in higher education: A review of the literature. Computers & Education, 57(4), 2333–2351. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.06.004

- Gonzalez-Gomez, D., Jeong, J. S., Airado Rodríguez, D., & Canada-Canada, F. (2016). Performance and perception in the flipped learning model: An initial approach to evaluate the effectiveness of a New teaching methodology in a general Science classroom. Journal of Science and Education Technology, 25(3), 450–459. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-016-9605-9

- Grabinski, K., Kedzior, M., & Krasodomska, J. (2015). Blended learning in tertiary accounting education in the CEE region – A Polish perspective. Accounting and Management Information Systems, 14(2), 378–397.

- Greasley, A., Bennett, D., & Greasley, K. (2004). A virtual learning environment for operations management: Assessing the student's perspective. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 24(9/10), 974–993. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570410558030

- Hall, G. (2011). Explaining English Language teaching: Learning in action. Routledge.

- Hall, K., Collins, J., Benjamin, S., Nind, M., & Sheeby, K. (2004). Saturated models of pupildom: Assessment and inclusion/exclusion. British Educational Research Journal, 30(6), 801–817. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192042000279512

- Hameed, S., Mellor, J., Badii, A., & Cullen, A. (2007). Factors mediating the routinisation of E-learning within a traditional university education environment. International Journal of Electronic Business, 5(2), 160–175. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEB.2007.012971

- Hettich, P. (1997). Epistemological approaches to cognitive development in college students. In P. Sutherland (Ed.), Adult learning: A reader (pp. 46–57). Kogan Page.

- Huon, G., Spehar, B., Adam, P., & Rifkin, W. (2007). Resource use and academic performance among first year psychology students. Higher Education, 53(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-005-1727-6

- IBA Global Employment Institute. (2017). Artificial Intelligence and Robotics and Their Impact on the Workplace Licensed under Creative Common Page 628.

- Jacklin, B., & Lange, De. (2009). Do accounting graduates` skills meet the expectations` of employers? A matter of convergence or divergence. Accounting Education, 18(4-5), 369–385. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09639280902719341

- Jonassen, D. H. (2000). Computers as mind tools for schools. Prentice Hall.

- Kaggermann, H.. (2015). Change through digitazation-value creation in the Age of the industry 4.0. In H. Albach, H. Meffert, A. Pinkwart, & R. Reichwald (Eds.), Management of Permanent Change (pp. 23–45). Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Kavanagh, M. H., & Drennan, L. (2008). What skills and attributes does an accounting graduate need? Evidence from student perceptions and employer expectations. Accounting & Finance, 48(2), 279–300. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-629X.2007.00245.x

- Kelly, S. D., Kravitz, C., & Hopkins, M. (2004). Neural correlates of bimodal speech and gesture comprehension. Brain and Language, 89(1), 253–260. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0093-934X(03)00335-3

- Kermis, G., & Kermis, M. (2010). Professional presence and soft skills: A role for accounting education. Journal of Instructional Pedagogies, 3(2), 1–10.

- Kirschner, P. A., & Drachsler, H. (2012). Learner characteristics. In N. Seel (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the sciences of learning (pp. 1743–1745). Springer US.

- Klein, D., & Ware, M. (2003). E-learning: New opportunities in continuing professional development. Learned Publishing, 16(1), 34–46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1087/095315103320995078

- Lee, H. L., Parsons, D., Kwon, G., Kim, J., Petrova, K., Jeong, E., & Ryu, H. (2015). Cooperation begins: Encouraging critical thinking skills through cooperative reciprocity using a mobile learning game. Computers & Education, 97, 97–115. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.03.006

- Lemke, M., Sen, A., Pahlke, E., Partelow, L., Miller, D., Williams, T., & Jocelyn, L. (2004). International outcomes of learning in mathematics literacy and problem-solving: Pisa 2003 results from the US perspective (NCSE 2005–003). US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics.

- Lim, D. H., & Morris, M. L. (2009). Learner and instructional factors influencing learning outcomes within a blended learning environment. Educational Technology & Society, 12(4), 282–293.

- López-Pérez, M. V., Pérez-López, M. C., & Rodŕiguez-Ariza, L. (2011). Blended learning in higher education: Students’ perceptions and their relation to outcome. Computers & Education, 56(3), 818–826. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.10.023

- López-Pérez, M. V., Pérez-López, M. C., & Rodŕiguez-Ariza, L. (2013). The influence of the use of technology on student outcomes in a blended learning context. Educational Technology Research and Development, 61(4), 625–638. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-013-9303-8

- Love, N., & Fry, N. (2006). Accounting students’ perceptions of a virtual learning environment: Springboard or safety net? Accounting Education: an International Journal, 15(2), 151–166. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/06939280600609201

- Luke, C. (2000). Cyber-schooling and technological change: Multiliteraices for new times. In B. Cope, & M. Kalantzis (Eds.), Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and design of social futures (pp. 69–91). Routledge.

- Marton, F., Dall’Alba, G., & Beaty, E. (1993). Conceptions of learning. International Journal of Educational Research, 19(3), 277–300.

- McGee, P., & Reis, A. (2012). Blended course design: A synthesis of best practices. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 16(4), 7–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v16i4.239

- Moore, T., & Hough, B. (2005). The perils of skills: Toward a model of integrating graduate attributes into the disciplines. Paper presented at Language and Academic Skills in Higher Education Conference. Canberra.

- Moore, T., & Morton, J. (2017). The myth of job readiness? Written communication, employability, and the ‘skills gap’ in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 42(3), 591–609. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1067602

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). (2014). PISA 2012 results: creative problem-solving: Students` skills in tackling real-life problems (volume V).

- Pellas, N., & Kazandis, I. (2015). On the value of second life for students` engagement in blended and online courses: A comparative study from the Higher Education in Greece. Journal of Education and Information Technology, 20(3), 445–466. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-013-9294-4

- Penfield, R. D., & Lee, O. (2010). Test-based accountability: Potential benefits and pitfalls of science assessment with student diversity. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 47(1), 6–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20307

- Phillips, F. (2001). A research note on accounting students`epistemological beliefs, study, strategies and unstructured problem-solving performance. Issues in Accounting Education, 16(1), 21–39. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2308/iace.2001.16.1.21

- Piaget, J. (1953). To understand is to invent. Grossman.

- Piaget, J. (1971). Biology and knowledge; an essay on the relations between organic regulations and cognitive processes (B. Walsh, Trans.). University of Chicago Press.

- Potter, J. (2015). Applying a hybrid model: Can it enhance students learning outcomes? Journal of Institutional Pedagogies, 17(11), 1–11.

- Pritchard, A., & Woollard, J. (2010). Psychology for the classroom: Constructivism and social learning. Routledge David Fulton.

- Reber, A. S. (1993). Implicit learning and tacit knowledge: An essay on the cognitive unconscious. Oxford University Press.

- Riley, T. J., & Simons, K. A. (2013). Writing in the accounting curriculum: A review of the literature with conclusions for implementation and future research. Issues in Accounting Education, 28(4), 823–871. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2308/iace-50491

- Schommer-Aikins, M., Duell, O. K., & Hutter, R. (2005). Epistemological beliefs, mathematical problem-solving beliefs, and academic performance of middle school students. The Elementary School Journal, 105(3), 289–304. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/428745

- Smedley, J. K. (2010). Modelling the impact of knowledge management using technology. OR Insight, 23(4), 233–250. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/ori.2010.11

- So, H.-J., & Brush, T. A. (2009). Students perceptions of collaborative learning, social presence and satisfaction in a blended learning environment: Relationships and critical factors. Computers and Education, 51(1), 318–336. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2007.05.009

- Stonebraker, P. W., & Hazeltine, J. E. (2004). Virtual learning effectiveness. The Learning Organization, 11(2/3), 209–225. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/09696470410532987

- Stull, J. C., Varnum, S. J., Ducette, J., Schiller, J., & Bernacki, M. (2011). The effects of formative assessment pre-lecture online chapter quizzes and student-initiated inquiries to the instructor on academic achievement. Educational Research and Evaluation, 17(4), 253–262. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13803611.2011.621756

- Taylor, B. (2000). Reflective practice. Open University Press.

- Trigwell, K., & Prosser, M. (1996). Changing approaches to teaching: A relational perspective. Studies in Higher Education, 21(3), 275–284. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079612331381211

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M., Davis, G., & Davis, F. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/30036540

- Warren, L., Reilly, D., Herdan, A., & Lin, Y. (2020). Self-efficacy, performance and the role of blended learning. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 13(1), 98–111. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-08-2019-0210

- Wong, L., Tatnall, A., & Burgess, S. (2014). A framework for investigating blended learning effectiveness. Education + Training, 56(2/3), 233–251. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-04-2013-0049