Abstract

In this article, we introduce active supervision as a simple, feasible strategy for teachers and families to increase student engagement as well as decrease off-task and disruptive behaviors across a range of contexts. We provide step-by-step guidance to illustrate how active supervision can be used by teachers in in-person and virtual learning environments as well as how families can incorporate active supervision into daily routines at home.

Teacher: Mr. Smith is a ninth-grade social studies teacher at Garza High School, a school implementing a Comprehensive, Integrated, Three-tiered (Ci3T) model of prevention (see Box 1; see Lane, Oakes, & Menzies, Citation2023 this issue). In alignment with his Ci3T Implementation Manual, Mr. Smith uses his school’s expectation matrix to teach the three school-wide expectations: be respectful, be responsible, and be safe. He begins each semester by explicitly teaching expectations to the students in each of his six classes, including modeling and practicing. Mr. Smith provides students opportunities to practice these expected behaviors throughout his instructional blocks. He acknowledges his students when they meet expectations by reinforcing their behaviors using their school-wide tickets (ROAR tickets) paired with behavior-specific praise, so they know what is expected in his class from start to finish. He also uses ROAR tickets to acknowledge students who are using the skills taught in the social and emotional well-being curriculum: Connect with Kids ®. He recognizes the importance of monitoring student engagement, work completion, and on-task behavior throughout the school year and supporting his students’ parents in utilizing these skills outside of the school day.

Student: Sarah Jane, a student in Mr. Smith’s third period class, receives special education services for a specific learning disability for reading with attention to fluency and comprehension. Sarah Jane knows about Mr. Smith’s expectations regarding homework completion but continues to struggle with turning in her homework. Sarah Jane’s social studies grade on her progress report has been low for two consecutive grading periods.

Family: Sarah’s Jane’s mother, Kennedy, has reviewed the school’s Ci3T Implementation Manual and regularly participates in family engagement at the school. She is familiar with the expectations in Mr. Smith’s social studies class and wants to make sure to support her daughter in completing required assignments, including homework.

In the most general sense, supervision is an integral part of school and home life, as it supports the well-being and safety of children. For example, teachers supervise students to ensure safety while interacting in the classroom, moving through hallways, and enjoying social time. During instruction, supervision is also important to ensure students are engaged academically in a host of activities, including independent and group work. Likewise, parents supervise their children to ensure safety within and outside the home setting, as parental supervision is linked to a decrease in likelihood of childhood injury (Morrongiello et al., Citation2004). For example, caregivers may direct their children to stay in a certain space at the park within eyesight of the caregiver. In addition to safety and well-being, educators and families also want environments to be rich in developmental opportunities to foster growth academically, behaviorally, and socially for children. In an academic context for example, teachers and families supervise children to support their success while varying the type of supervision as children and youth progress from preschool through high school.

Educators at schools implementing Comprehensive, Integrated, Three-tiered (Ci3T) models strategically use low-intensity strategies to support the creation and maintenance of positive, productive learning environments, including the use of active supervision. Active supervision is an effective, efficient strategy for use with students from preschool through high school, and in various settings at school (e.g., classroom, hallways) and home (e.g., when doing homework, enjoying time with friends, doing chores, and getting ready for school; Allen et al., Citation2020a). A key benefit of active supervision is that it allows adults to interact with students and children before challenges arise (Colvin et al., Citation1997). When actively supervising, adults use the eight-step process (see Lane et al., Citation2015 and ) to identify activities or transitions that may benefit from active supervision. Active supervision involves teaching expectations (or ensuring that the routine for the activity is well-established and familiar to students), scanning and monitoring the area during the activity, reinforcing rule-abiding behavior, providing private, corrective feedback as necessary, and ensuring children also have the opportunity to give feedback.

According to research as early as 1970, preventing behavior problems is a key proponent of maintaining a positive, productive classroom environment and just as important as how teachers respond to challenging behavior (Kounin, Citation1970). When teachers supervise students by regularly monitoring and placing themselves where they can see all students, the classroom environment benefits greatly in terms of safety and student engagement. Students know their teacher is aware of their actions during class time. Likewise, parents and other caregivers can accomplish a similar level of safety and engagement outside of the school building when utilizing active supervision. As educators navigate the COVID era in which instruction may take place virtually, in-person, or through a hybrid of in-person and remote, it is particularly important for teachers and families to be empowered with strategies not only to support engagement and minimize disruption, but also to keep everyone safe as the responsibility of teaching is largely shared between families and educators.

Purpose

In this article, we introduce active supervision as an easy-to-use strategy that can be implemented in various settings (e.g., in-person instruction, remote instruction, at home) and by various stakeholders (e.g., teachers, parents). In short, active supervision is the scanning and monitoring of student behavior in a specific setting after a direction with behavior expectations is given. Active supervision is designed and implemented to prevent problem behavior and promote desired behavior (Colvin et al., Citation1997). Active supervision is often used in tandem with precorrection, (i.e., giving of verbal and/or visual prompts and supports to students to prevent problem behavior) to increase the effectiveness of active supervision (Lane et al., Citation2015). In this article, we highlight how to use active supervision at the high school level.

Introduction to active supervision

What is active supervision?

Active supervision is when the adult, following giving a direction or cue with behavior expectations for a specific context, moves around the specific setting (e.g., playground, room) to scan and monitor and respond effectively to behaviors (Colvin et al., Citation1997). The scanning is followed by reinforcement for desired behaviors and, if needed, corrections to support students in enacting desired behaviors. For active supervision to be successful, routines and procedures need to first be established with sufficient directions and/or cues taught to the learner prior to implementing active supervision. Furthermore, teachers need to communicate “with-it-ness” (an adults’ ability to communicate to students they are aware of what is going on and that they have things under control) and “overlappingness” (an adult’s ability to pay attention to more than one thing at a time; Kounin, Citation1970; Menzies et al., Citation2018).

Two essential components of active supervision are proximity and reinforcement (Cooper et al., Citation2020). Proximity refers to the physical closeness of the adult to the adolescent and is an effective reminder to students that the adult (teacher or family member) is observing their behavior. However, it is important to remember children and adolescents can sometimes be uncomfortable with adult proximity, especially in times of conflict or high emotion. Therefore, proximity should be used proactively—to help remind students—rather than reactively redirecting students. Another essential component of active supervision is reinforcement. Reinforcement refers to providing students with acknowledgement for reaching desired behaviors. Reinforcement can help at the onset of teaching expectations to support students in reaching desired behaviors and likewise to internalize the expectations and to maintain existing expectations. When adults are using active supervision and constantly scanning and monitoring while communicating their sense of “with-it-ness” and “overlappingness”, they can easily provide reinforcement for children who they notice are meeting the desired behavior (Menzies et al., Citation2018).

What is the research behind active supervision?

There is a strong evidence base for the effectiveness of active supervision to achieve student outcomes. Allen et al. (Citation2020a) conducted a systematic literature review of active supervision in traditional K-12 settings using the Standards for Evidence-Based Practices in Special Education (Cook et al., Citation2014) to learn more about how well the implementation of active supervision worked for different students (e.g., students with and without disabilities) across different settings (e.g., classrooms, non-instructional settings in K-12 schools). Allen et al. identified seven articles examining active supervision in a variety of school settings (e.g., classroom, grade level, school-wide) and school levels (i.e., elementary, middle, high school). Allen and colleagues then read each article and applied an 80% weighted criterion for high methodological quality. This 80% weighted criterion is an adapted approach, giving partial credit for studies that include some—but not all—quality indicators. All seven studies met this 80% weighted criterion. Authors found active supervision to be a potentially evidence-based practice, largely due to the small number of studies showing positive effects (i.e., only three single case design studies). However, the literature review found a variety of articles which demonstrates the efficacy and flexibility of the active supervision strategy in school settings. Next, we highlight three studies showing how active supervision has been effective in a range of settings.

Colvin et al. (Citation1997) investigated the impact of active supervision and precorrection on problem behavior when students entered school, the cafeteria, and exited school. Researchers used a multiple-baseline design where the researchers first looked at baseline student behaviors across all settings, and then introduced the intervention in one setting at a time to determine the impact of the intervention in each given context. Participants were 475 students in kindergarten through fifth grade at a rural/suburban school in the Pacific Northwest. Paraprofessionals, classroom teachers, and the principal delivered the intervention, using precorrection prior to students beginning the transition by reminding them of schoolwide behavior expectations, and active supervision to move around, look around, and interact with students as they transitioned to each space in the school. Researchers found problem behavior decreased in all areas after the introduction of active supervision and precorrection.

De Pry and Sugai (Citation2002) studied the impact of an active supervision, precorrection, and daily data review package on students’ minor behavioral incidents (e.g., passing notes, engaging in off-task behavior). The study design was an A-B-A-B withdrawal design, where the intervention was first withheld to understand baseline student behavior, then introduced to the students, briefly taken away, and then introduced a second time. Participants were 26 sixth grade students in a general education classroom in a rural elementary school. An experienced sixth grade teacher delivered the intervention, with researchers meeting with the teacher daily to review data on how students responded to the intervention. De Pry and Sugai (Citation2002) found a decrease in minor behavioral incidence after the introduction of the intervention package.

Johnson-Gros et al. (Citation2008) examined how active supervision impacted student tardies. Researchers used a multiple-baseline design across two different periods. Participants included about 450 high school students in ninth through twelfth grade. High school staff (i.e., 36 teachers) implemented the active supervision strategy by spreading out throughout the school and interacting with students to encourage them to go to class or physically escorting them. Researchers found a reduction in office discipline referrals (ODRs) for tardies after the introduction of the intervention.

Haydon et al. (Citation2012) examined how the combination of active supervision and precorrection impacted the success of a teacher’s redirection and the number of minutes between a class transition. The researchers used an ABCBC single case research design. Participants were one teacher and her class of 20 7th graders. The research team found the combination of these two strategies (active supervision and precorrection) and the use of a timing procedure explicitly taught to students decreased the frequency of teacher redirections and the time to transition between classes. At the conclusion of the study, the teacher also completed a 4-point, Likert-type social validity survey in which she indicated the training was helpful and the intervention was useful and easy to implement.

Active supervision has a robust evidence base demonstrating its effectiveness (Allen et al., Citation2020a). Active supervision can be implemented in a variety of settings, including schoolwide (Colvin et al., Citation1997) and classroom settings (De Pry & Sugai, Citation2002). A variety of behaviors can be targeted for support, including tardiness (Johnson-Gros et al., Citation2008), off-task class behavior (De Pry & Sugai, Citation2002), transitions between classes (Haydon et al., Citation2012) and problem behaviors at arrival and dismissal (Colvin et al., Citation1997). In summary, active supervision is an effective and flexible strategy useful for supporting student behavior and safety across the grade span in schools (Allen et al., Citation2020a). Likewise, supervising young children at home is linked to a decrease in childhood injury, which is a favorable outcome for those studying pediatrics (Morrongiello et al., Citation2004).

Step-by-step procedures and illustrations for incorporating active supervision

Given active supervision is a potentially evidence-based practice, we offer step-by-step guidance and illustrations for general and special education teachers to use active supervision during in-person instruction and during remote instruction, followed by guidance and an illustration for families to use active supervision in the home setting (see Menzies et al., Citation2018 for additional illustrations for using active supervision in person). In , we provide a summary of steps for use in schools (in-person and remote) and home settings.

Table 1. Active supervision: implementation checklist.

School: in-person instruction

Active supervision is effective and efficient in increasing engagement and reducing disruption in the classroom and can be used within in schools implementing tiered systems (e.g., Ci3T) as well as schools not yet implementing such systems. To implement active supervision successfully, ensuring the active ingredients (e.g., implementation steps) are in place is imperative. Below, we provide an example of the steps for implementing active supervision in an in-person setting at the high school level (see for steps for using active supervision in-person with students).

Step 1. Mr. Smith knows that his students sometimes need extra support staying on-task during group work, so he identifies that portion of class as a time when he will execute active supervision. In particular, he notices in his grade book that many students in his fifth-period class have several missing assignments.

Step 2. Mr. Smith uses direct instruction prior to completion of group work outlining the expectations.

Step 3. Mr. Smith then assigns the groups for group work, gives the groups the assignment for the day, and asks the groups to begin working.

Step 4. Mr. Smith makes sure to visit with each group as they work to ensure groups are on-task and answer any questions they may have.

Step 5. Mr. Smith moves closer to a group that begins to talk about weekend plans, and the group quickly gets back on-task.

Step 6. When one group continues to talk about weekend plans, Mr. Smith goes over to the group and verbally reminds the group of the task at-hand. Once the group has been on-task for an acceptable amount of time, Mr. Smith verbally praises the group.

Step 7. Before the end of the class period, Mr. Smith does “shout-outs” for groups who worked the entire time or were particularly productive in accomplishing their work.

Step 8. As students are packing up for the next period, Mr. Smith asks students to write on a post-it note what they enjoyed about the group work and what they would like to change for next time.

School: remote instruction

Active supervision has been studied and determined to be a potentially evidence-based practice in the in-person classroom setting (Allen et al., Citation2020a). However, it is reasonable to extend active supervision to the virtual learning environment as well (Allen et al., Citation2020b). In fact, given that students often have access to many features with virtual learning platforms on their technology devices, active supervision may be very important to ensuring on-task behavior and academic success for students in the virtual learning context. Here we illustrate how active supervision can be executed in a remote learning environment, as many educators utilized during the COVID-19 pandemic and on a more consistent basis in full-time virtual schools.

As Mr. Smith began instruction in March 2020 on the school’s provided virtual learning platform, he wanted to ensure his students were still getting to participate in group activities as well as independent work time as both had been large components of instruction in his in-person class. Mr. Smith also utilized active supervision often in his classroom especially during group activities and independent work time to ensure students were on-task and meeting expectations for the various assignments. Mr. Smith knew he would need to continue using active supervision during group and independent activities in the virtual setting as well.

Step one: Identify the virtual activity or transition that would benefit most from active supervision

First, Mr. Smith thought about the structure of his virtual class. He considered what virtual activities would benefit from active supervision. Just like his in-person class, group activities and independent work time would be important times to actively supervise students. He would be utilizing breakout rooms for group activities, so Mr. Smith made a plan.

Step two: Ensure that the routine for the target activity is familiar and understood by students. If not, virtual learning routines and expectations must be established

Mr. Smith remembered that routines for online remote settings must be established just as they need to be for in-person settings. He established the routine for breakout rooms by explicitly teaching his expectation matrix for the specific setting of breakout rooms and checking for understanding to ensure the routine was understood by students.

Step three: Provide the cue or prompt to begin the activity

Mr. Smith made sure to share his screen with the breakout room expectation matrix as a prompt/cue when he gave directions for the beginning of a group or independent activity.

Step four: As the activity unfolds, scan across the virtual environment (e.g., video call, chat, collaborative document) and continue to monitor their verbal and non-verbal responses (e.g., written words, virtual responses such as thumbs up or down)

Mr. Smith assigned Sarah Jane and two other students to a breakout room to work on a group activity. After assigning the breakout rooms, he visited each room to actively supervise and answer any questions. Mr. Smith varied the order of which rooms he visited so that students in the group he visited last did not anticipate a longer gap of unsupervised time after each return to breakout rooms.

Step five: Signal your awareness of students’ actions through virtual non-verbal cues, verbal acknowledgements, chat communications, and prompting as needed

Mr. Smith acknowledged students who were on-task in breakout rooms by typing in the chat and verbally praising students when appropriate (e.g., “Sarah Jane, thank you for contributing to the conversation so far by responding to your peers in the chat!”). Mr. Smith also gave prompts as needed to students with questions, both in chat communication and in verbal conversation.

Step six: Manage infractions and off-task behavior efficiently, privately, and discretely and with opportunities for positive interactions

Upon closing the breakout rooms and inviting students back to the main room, he noticed Sarah Jane was no longer present on the virtual meeting (her camera was off, and she was not responding to chat messages). He sent a private message to Sarah Jane upon her return reminding her of the requirement of attendance for the full class period. The message was sent privately to ensure only Sarah Jane received the feedback unbeknownst to other students. Mr. Smith remembered the importance of taking an instructional approach to supporting behavior even in remote settings to ensure students understand and can perform the behavior.

Step seven: At appropriate intervals and at the end of the activity or transition, reinforce students’ behaviors meeting the virtual learning environment expectations using positive comments, gestures, and virtual reactions

Now, in the main room, Mr. Smith provides some verbal acknowledgements of groups who were meeting expectations while working in breakout rooms (e.g., “Sarah Jane’s group followed the expectation of listening actively to one another by responding to each other’s ideas both in the chat and verbally!”). When students began working independently from the main room, Mr. Smith typed notes of behavior-specific praise in chat either to the whole group or through private messages depending on the needs of the student.

Step eight: Provide students with an opportunity to give feedback

Finally, at the end of the class period, Mr. Smith created a poll through his school’s provided virtual learning platform in which students were able to give feedback anonymously and offer their perspectives on the class that day. Overall, students seemed to like the breakout rooms and structures of the class as well as the intermittent feedback and support from Mr. Smith, so Mr. Smith decided to continue incorporating breakout rooms and actively supervising to support student success in the virtual context.

Home: a guide for families

As mentioned, active supervision requires proximity, reinforcement, and feedback. Like all instructional techniques, active supervision is most successful when implemented as planned. As such, we recommend first being intentional about when, where, and how to implement. In the following example, we highlight a mother of a high schooler supporting her child with homework completion by implementing active supervision.

Sarah Jane’s mother, Kennedy, noticed a low grade in social studies. Her mother called Mr. Smith explaining that she was having a difficult time encouraging Sarah Jane to do her social studies homework. Mr. Smith thought Kennedy could support Sarah Jane by implementing active supervision at home to support Sarah Jane in completing her homework and bringing her grade up. Kennedy reflected on Sarah Jane’s school performance and decided that homework completion would benefit the most from this active supervision support. Mr. Smith and Kennedy talked through the steps for implementing active supervision, so Kennedy could start trying this at home right away (see for steps for implementing active supervision in the home setting).

Step 1. The next weekend, Kennedy talked with Sarah Jane about her social studies grades. Sarah Jane was familiar with the content and the procedures for completing her homework; she just needed a little support with completing the tasks.

Step 2. They made a plan to support Sarah Jane: she would work on her homework right away when she got home before engaging in other activities after school each day

Step 3. When Sarah Jane arrived home from school Monday, Kennedy reminded her of the expectation to complete her homework now before she could call or text or meet up with friends

Step 4. Kennedy decided to clean in the living room while Sarah Jane completed her homework in the next room over, at the kitchen table.

Step 5. Kennedy periodically walked into the kitchen and checked in with Sarah Jane. She checked on Sarah Jane’s work and praised her when she was on-task.

Step 6. At one point, Sarah Jane began to check her cell phone. Her mom politely asked her if she had already completed her homework. When Sarah Jane responded that she had not yet finished, her mom reminded her of the plan they had made.

Step 7. Sarah Jane put her cell phone away and continued working on her homework. Kennedy thanked Sarah Jane for upholding their plan and returning to her homework. When Sarah Jane finishes her homework, her mom praised her for completing her work and refraining from engaging in off task behaviors like texting friends.

Step 8. Sarah Jane left the kitchen and went to her room to text with her friends. Kennedy stopped by later in the afternoon to ask Sarah Jane if she liked having this plan to support her homework completion. Sarah Jane said that it was nice to have her homework done so she did not have to worry about it all evening, and that she would appreciate her mom’s support with other homework activities.

Kennedy continued to implement active supervision at home to support Sarah Jane in homework completion for social studies class. Over time, Sarah Jane began to initiate homework completion on her own, and Mr. Smith was pleased to see Sarah Jane’s homework turned in daily. Eventually, Sarah Jane’s progress report grades began to reflect her hard work. Active supervision is a simple strategy and can give students like Sarah Jane the support they need to complete tasks and remain engaged in and out of the school setting—skills that will ultimately support their life-long success.

Moving forward with active supervision

By incorporating active supervision into daily instruction (in-person, remote, hybrid) and into the daily activities at home, educators and caregivers alike can support students in making safe, productive choices and avoid problematic behaviors. Educators and caregivers committed to supporting students with a wide variety of needs through an integrated system of support seek professional learning opportunities to enhance their skill levels in delivering low-intensity strategies, such as active supervision, behavior-specific praise, instructional choice, and precorrection (Lane et al., Citation2015). The skills gained in these professional learning experiences can help educators and caregivers achieve goals of keeping students safe and supporting students in reaching their full academic and social potential.

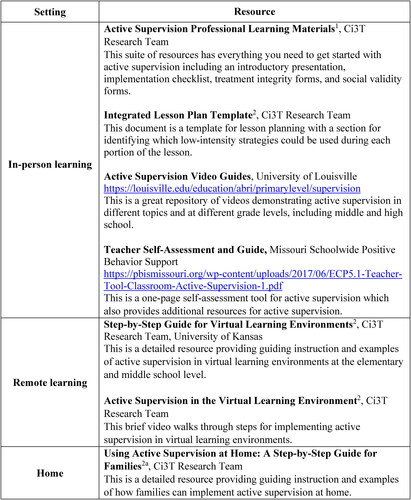

Schools implementing Ci3T have received professional learning on integrated lesson planning. With integrated lesson planning, teachers prepare to address academic objectives as well as support social or behavioral objectives and simultaneously utilize low intensity strategies throughout each component of the lesson. For example, a calculus teacher may plan an opening activity to be completed on students’ phones and want to ensure they pay extra attention to students’ level of on-task behavior during this portion of the lesson when cell phones are being used. The teacher may write in their integrated lesson plan how and when they will utilize active supervision to ensure this activity goes as planned. Perhaps the educator could couple active supervision with behavior-specific praise acknowledging students for meeting expectations the educator is closely monitoring while actively supervising. While active supervision fits well within a schoolwide system of support such as Ci3T, this low-intensity support can also be implemented effectively by individual educators working in schools that do not yet have a tiered system of support in place, as well as by families. Likewise, families could do the same when incorporating active supervision in certain at-home activities, providing behavior-specific praise for their children when they notice safe, productive behaviors. In we provide a few resources to guide implementation of active supervision in different contexts and grade levels.

Summary

In this article, we introduced active supervision as an easy-to-use strategy that can be implemented by teachers during instructional and non-instructional times (in person, virtual, and hybrid), as well as at home with families. Active supervision is designed and implemented to prevent problem behavior and promote desired behavior (Colvin et al., Citation1997). We illustrated implementation of active supervision by teachers during instruction (e.g., during group work) and by families implementing active supervision at home (e.g., during homework completion). The examples of active supervision implementation provided (both of teachers and families) emphasize its feasibility and effectiveness.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Katherine S. Austin, M.Ed. is a doctoral student in the department of special education at University of Kansas. She earned her bachelor of arts degree in communication with a minor in international studies from Auburn University. She then moved to Nashville, Tennessee where she received her master’s degree in instructional practice in education with an endorsement in English language learners from Lipscomb University. She taught third and fourth grade general education for seven years and also served as an administrator for one year. Her interests include comprehensive, integrated, three-tiered (Ci3T) models of prevention, teacher preparation and in-service professional learning and coaching, low-intensity strategies and evidence-based practices to support students in reading and writing, and positive behavioral interventions and supports (PBIS).

Grant Edmund Allen, Ph.D. is an assistant professor of special education at University of Wisconsin-Stout in Menomonie, Wisconsin. He earned his bachelor’s degree in social science education from Saint Cloud State University in Saint Cloud, Minnesota, his master’s degree in special education from Fort Hays State University in Hays, Kansas, and his doctorate in special education from University of Kansas. He taught for five years in southwest Kansas as an inclusive special education teacher in math, English, social studies, and science classrooms. His interests include building, implementing, and evaluating tiered models, including comprehensive, integrated, three-tiered (Ci3T) models of prevention, low-intensity behavior support strategies, and social validity of Tier 1 practices within tiered models.

Nelson C. Brunsting, Ph.D. serves as the Director of Center for Research on Abroad and International Student Engagement and is a Research Associate Professor of International Studies at Wake Forest University. Nelson earned his MA in Classics at Victoria University in Wellington, New Zealand, and his Ph.D. in Educational Psychology at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His research is focused on understanding and enhancing social-emotional outcomes of diverse populations in educational contexts. Within Ci3T, Nelson is interested in understanding how teachers fare with respect to effectiveness, self-efficacy, and burnout while implementing Ci3T models of prevention. Other lines of inquiry include relationships between working conditions of special educators serving students with EBD and their burnout over time, and exploring social-contextual factors associated with international students’ adjustment to U.S. universities.

Eric Alan Common, Ph.D., BCBA-D, LBA (MI) is an assistant professor at University of Michigan-Flint. His research explores the active role schools play in whole-child development. More specifically, his research explores the delivery of academic, behavioral, and social-emotional prevention and interventions delivered through Comprehensive, Integrated, Three-tiered (Ci3T) models and school-based applied behavior analysis services.

Kathleen Lynne Lane, Ph.D., BCBA-D, CF-L2 is a Roy A. Roberts Distinguished Professor in the Department of Special Education at the University of Kansas and Associate Vice Chancellor for Research. Her research interests focus on designing, implementing, and evaluating Comprehensive, Integrated, Three-tiered (Ci3T) models of prevention to (a) prevent the development of learning and behavior challenges and (b) respond to existing instances, with an emphasis on systematic screening. She is the co-editor of Remedial and Special Education. Dr. Lane has co-authored or edited 14 books and published 235 refereed journal articles and 56 book chapters.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allen, G. E., Common, E. A., Germer, K. A., Lane, K. L., Buckman, M. M., Oakes, W. P., & Menzies, H. M. (2020a). A systematic review of the evidence base for active supervision in Pre-K–12 settings. Behavioral Disorders, 45(3), 167–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/0198742919837646

- Allen, G. E., Lane, K. S., Austin, K. S., Pérez-Clark, P., Lane, K. L., Oakes, W. P., Menzies, H. M. (2020b). Active supervision: A step-by-step guide for virtual learning environments. Ci3T Strategic Leadership Team. www.ci3t.org

- Colvin, G., Sugai, G., Good, R. H., III, & Lee, Y. Y. (1997). Using active supervision and precorrection to improve transition behaviors in an elementary school. School Psychology Quarterly, 12(4), 344–363. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0088967

- Cook, B., Buysse, V., Klingner, J., Landrum, T., McWilliam, R., Tankersley, M., & Test, D. (2014). Council for exceptional children: Standards for evidence-based practices in special education. Teaching Exceptional Children, 46(6), 206–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0040059914531389

- Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2020). Applied behavior analysis (3rd ed.) Merrill.

- De Pry, R. L., & Sugai, G. (2002). The effect of active supervision and pre-correction on minor behavioral incidents in a sixth grade general education classroom. Journal of Behavioral Education, 11(4), 255–267. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021162906622

- Haydon, T., DeGreg, J., Maheady, L., & Hunter, W. (2012). Using active supervision and precorrection to improve transition behaviors in a middle school classroom. Journal of Evidence-Based Practices for Schools, 13(1), 81–94.

- Johnson-Gros, K. N., Lyons, E. A., & Griffin, J. R. (2008). Active supervision: An intervention to reduce high school tardiness. Education and Treatment of Children, 31(1), 39–53. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.0.0012

- Kounin, J. S. (1970). Discipline and group management in classrooms. Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- Lane, K. L., Menzies, H. M., Ennis, R. P., & Oakes, W. P. (2015). Supporting behavior for school success: A step-by-step guide to key strategies. Guilford Press.

- Lane, K. L., Oakes, W. P., Allen, G. E. (2020). Using active supervision at home: A step-by-step guide for families. Ci3T Strategic Leadership Team. www.ci3t.org

- Lane, K. L., Oakes, W. P., & Menzies, H. M. (2023). Using low-intensity strategies to support engagement: Practical applications in remote learning environments for teachers and families. Preventing School Failure, 67(2), 79–82.

- Menzies, H. M., Lane, K. L., Oakes, W. P., Ruth, K., Cantwell, E. D., & Smith-Menzies, L. (2018). Active supervision: An effective, efficient, low-intensity strategy to support student success. Beyond Behavior, 27(3), 153–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074295618799343

- Morrongiello, B. A., Ondejko, L., & Littlejohn, A. (2004). Understanding toddlers’ in-home injuries. II. Examining parental strategies, and their efficacy, for managing child injury risk. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 29(6), 433–446. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsh047