Abstract

This study explored the function of school leading in the implementation process of education for sustainable development (ESD) in five Swedish schools employing a whole school approach (WSA). A follow-up study design was used, in which schools that had initiated an ESD project in 2016 were subsequently visited twice for interviews with principals during the project and after it was finalized. The theory of practice architectures in combination with the concept of school improvement capacity was used as the theoretical framework in the analysis. The study showed how school leading should be about enhancing the local school’s capacity to improve. It also showed how specific practice architectures prefigured a WSA to ESD and how school leading in this context was about arranging—or orchestrating—practice architectures in ways that enabled such an approach. The issues of time and endurance were pivotal. Based on the empirical results from this study and school improvement theory, guidelines were developed that can be used to drive a WSA to ESD process forward through three different school improvement phases: initiation, implementation, and institutionalization. The limitations and suggestions for further research are also discussed.

1. Introduction

There is a widespread understanding that schools play a pivotal role in protecting and preserving biological, social, and material resources, as education is a well-proven strategy for fostering the coming generations and empowering individuals to think and perform in wise and respectful ways (Vare, Lausselet, and Rieckmann Citation2022). However, this requires a certain kind of education that supports shared responsibility and promotes competences in collaboration and critical and creative thinking (Eilam and Trop Citation2010). This approach, which in both policy (United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2017) and research (Öhman Citation2008; Vare and Scott Citation2007) has been denoted education for sustainable development (ESD), is a response to the need to educate students to cope with the complex challenges associated with sustainable development and future societies (Mogren Citation2019). This is an approach that to some degree challenges traditional schooling, as it does not focus on single school subjects and short-term goals. ESD calls for an education that empowers students, both in the long and short terms, by enhancing their action competences and their awareness of how to contribute to positive sustainable changes.

An important way to introduce ESD at local schools is to acknowledge that school organizations and school leaders are essential factors in mobilizing commitment among both students and staff by supporting continuous sense-making activities that lead to a deeper understanding of ESD (Gan Citation2021; Müller, Lude, and Hancock Citation2020). Hence, school leadership is an important aspect of a holistic whole school approach (WSA) to ESD that engages all stakeholders in schools (e.g. students, teachers, and school leaders) in a collaborative quest with stakeholders in society for ESD and, in the long run, sustainability (Gericke Citation2022; Mathie and Wals Citation2022). As a dominant part of research on school leadership focuses on leaders as individuals, this study focused on the actual practices conducted: so-called school leading. According to Verhelst et al. (Citation2020), there is a need for increased research on facilitating roles within the school organization. This gap was filled by illuminating the function of school leading in implementing ESD in local school organizations. In this study, local school organizations were perceived as systems of human beings relating to social life on a structural level (Blossing et al. Citation2015).

The background section that follows provides an overview of current fields of knowledge, leading to the aim of this study, to illuminate the function of school leading in the implementation process of ESD. Next, the four theoretical frameworks used to analyze this specific ESD project are introduced. The method section describes how the researchers returned to the schools twice to follow up on the project that was launched in 2016 (Gericke and Torbjörnsson Citation2022a, Citation2022b), conducting interviews with the participating principals. The results are presented in the form of narratives, with five cases addressing the first research question. The second research question is addressed in the form of descriptions and explanations of why things turned out the way they did in the implementation process. In the concluding discussion, guidance and advice are provided for leading WSA to ESD improvement processes in local schools, with a focus on the school leading function. The guidance and advice are categorized and concretized by referring to existing school improvement phases: initiation, implementation, and institutionalization.

2. Background

ESD is an approach to teaching and organizing education that reviews of research (Eilam and Trop Citation2010; Vare and Scott Citation2007) and policy have identified as a transformative approach and a key enabler of all the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), with the purpose of transforming society in a more sustainable direction. The UNESCO roadmap for ESD states the following:

ESD is a lifelong learning process and an integral part of quality education that enhances cognitive, social and emotional and behavioral dimensions of learning. It is holistic and transformational and encompasses learning content and outcomes, pedagogy and the learning environment itself. (United Nations Educational and Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Citation2020, p. 8)

As a major part of research on school leadership focuses on leaders as individuals or leading teams, the focus on school leading as a practice draws attention away from individuals to the actual work of leadership: the so-called happeningness of school leading (Wilkinson and Kemmis Citation2015). According to Wilkinson (Citation2019), this is not to deny the agency of individuals but to draw attention to the specific conditions that create particular practices. This study emphasizes the importance of this work institutionalizing ESD through organizational practices, instead of depending on so-called souls of fire, committed individuals who, in the literature, have been found to be a common driver for ESD implementation at local schools (Wickenberg Citation2013). In such cases, ESD is not anchored within the routines and structures of the school organization, so its implementation is vulnerable if these souls of fire leave the organization (Mogren and Gericke Citation2019). It is thus of great importance to identify practices and routines for leading schools in achieving and institutionalizing ESD in accordance with a WSA.

Based on previous school improvement studies (Forssten Seiser and Blossing Citation2020; Harris Citation2001; Hopkins Citation2007), efforts aimed at local schools’ infrastructure and overall capacity to practice school improvement (Blossing et al. Citation2015) are of interest within the ESD field. Such efforts motivated this multidisciplinary study, which involved a WSA to ESD, school leading, and school improvement. School leading and school improvement are both established research fields within leading and development; therefore, it is wise to use the knowledge that is available within these two fields on how to lead and implement improvements in school organizations. A multidisciplinary approach contributes through knowledge regarding the implementation of socially and educationally sustainable qualities (Forssten Seiser and Blossing Citation2020; Hopkins Citation2007). A WSA involves all parts of the school organization, and in this study, it contributes to a comprehensive perspective by emphasizing connections between school leading, local school organizations, and ESD implementation. Finally, a practice-informed approach provides valuable insights by investigating principals’ leading and its preconditions in terms of the practice architectures enabling or constraining the realization of a WSA to ESD. Practice architectures exist in a dialectical relationship with the practices that they prefigure, in that they both constitute and are constituted by practice (Kemmis et al. Citation2014).

3. Aim and research questions

The overall aim of the follow-up study reported here was to illuminate the function of school leading in the implementation process oof ESD over time. This was explored in relation to identified leading actions in the different phases of a school improvement process. Undertaking this work required an examination of what happened when ESD was implemented in local school over a period of time. In order to do this, the researcher returned to five schools in a municipality that had initiated an ESD project in 2016, interviewing principals in 2018 and then again in 2020. The interviews explored whether (or not) the local preconditions had developed into practice architectures (Kemmis et al. Citation2014) that facilitated ESD. The research questions were as follows: (1) How did the implementation processes of ESD appear at the local schools from a leading perspective? (2) What practice architecture enabled and constrained a WSA to ESD?

4. Theoretical framework

This section provides a presentation of the theories and concepts that were used to frame the study. A combination of frameworks from different disciplines enabled the illumination of school leading in the implementation of ESD in the five school. More precisely, the theory of practice architectures (Kemmis et al. Citation2014) was used for identifying what happened (sayings, doings, and relatings) in practice during the ESD implementation processes according to the principals and what characterized these processes. In addition, the theory of practice architectures allowed for an exploration of the prerequisites—or practice architectures—that enabled or constrained the ESD processes in the five participating schools by revealing how the ESD processes were prefigured by the practice architectures present at, or brought into, the schools. Certain ESD implementation criteria (Mogren Citation2019) facilitated a detailed analysis of the principals’ descriptions and enabled an assessment of the ESD implementation processes. The focus on a WSA (Mathie and Wals Citation2022) contributed through an ideal that includes a societal perspective, as well as by providing a comprehensive approach linking school leading, school organization, and ESD. The final theoretical framework, school improvement capacity (Blossing et al. Citation2015), was used for categorizing the implementation processes and assessing whether or not a WSA to ESD had been institutionalized in the five participating schools. The four theoretical frames are outlined under the following headings.

4.1. Theory of practice architectures

The theory of practice architectures provided a practical lens to explore how the implementation processes of ESD appeared from a leading perspective. According to this theory, a practice is understood as a socially established cooperative human activity constituted by the sayings, doings, and relatings that hang together in the project of a specific practice (Kemmis et al. Citation2014):

The notion of the project of the practice refers to the intentions of those involved in the practice, but it also refers, in part, to things taken for granted by participants and things that exist in the intersubjective spaces in which we encounter one another in any particular site (in language in semantic space; in activities and work in the material world of physical space–time; and in relationships pf power and solidarity in social space (Kemmis et al. Citation2014, p. 14).

Fundamental to the theory of practice architectures is the attention given to the arrangements that enable or constrain specific practices in a specific site. This means that a practice is prefigured by the practice architectures that are present or brought into the site of the practice. Practice architectures are the particular arrangements that together shape, and are shaped by, the practice (Kemmis et al. Citation2014; Mahon et al. Citation2017). Therefore, to understand why the ESD implementation processes unfolded as they did, the intersubjective spaces where they took place have to be considered. The practice architectures that enabled or constrained a WSA in the ESD implementation processes were thus of interest in this study.

To understand why the ESD implementation processes unfolded as they did in the five schools, the intersubjective spaces where they took place have to be considered. The three intersubjective spaces where practice architectures appear are the semantic, physical, and social spaces connected to a specific practice, which in this case was the ESD implementation process. In the semantic space, cultural–discursive arrangements emerged through the language and speech surrounding the ESD processes. In the social space, social–political arrangements revealed how people related to one another as well as to artefacts inside and outside the ESD implementation processes. In the physical space, material–economic arrangements became visible in the actions and work that took place within the implementation processes (Kemmis et al. Citation2014). It is important to remember that practice architectures can exist beyond the intentional actions of individuals. The theory maintains that practices are human-made and socially established; therefore, it highlights the role of the participant in the practice and in the shaping of the practice (Kaukko and Wilkinson Citation2020).

4.2. ESD implementation criteria

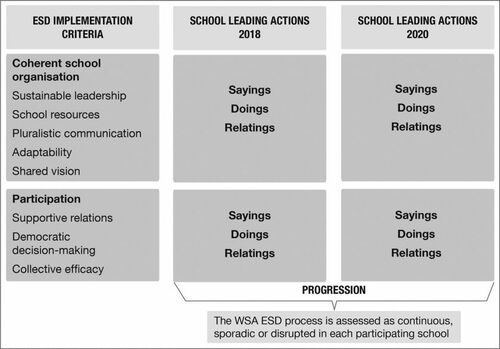

To explore the implementation process in detail in each of the participating schools, the following ESD implementation criteria were used: coherent school organizations, participation, and progression (Mogren Citation2019). The decision to look at the five schools individually was motivated by practice theory, which emphasizes that practices must be examined in the specific sites where they occur (Nicolini Citation2012). These ESD implementation criteria are based on empirical studies on the quality criteria and ESD implementation strategies of the most successful ESD implementations in schools in Sweden (Mogren and Gericke Citation2017a, Citation2017b).

In accordance with the research of Verhelst et al. (Citation2020), the first two implementation criteria (coherent school organizations and participation) were operationalized into school leading actions using ESD-effective school characteristics: sustainable leadership, school resources, pluralistic communication, supportive relations, democratic decision-making, shared vision, adaptability, and collective efficacy. A review of each of these ESD-effective school characteristics revealed how a sustainable leadership is operationalized into a holistic leading that involves an integrated view of the past, present, and future. This involves the competence to adapt leading to a specific situation, time, and context. Leading connected to school resources and pluralistic communication involves the ability to organize the school’s infrastructure to facilitate ESD. In this case, time management, setting up communication channels, allowing cross-curricular activities, and organizing teachers in teams promoting cross-curricular activities were leading actions that supported ESD. Issues related to the implementation of ESD are easier to overcome with collaboration and supportive relations. The latter refers to relations both within the local school and between schools. It also refers to supportive networks between school leaders and outside partners. Inevitably, democratic decision-making requires that those effected by the ESD improvement work are involved in the decision-making process through a shared understanding of what it means and what the expectations are. For this reason, a shared vision is vital for success. Regarding the final two ESD-effective school characteristics, adaptability refers to the local school’s competences for responding to internal and external demands in ways that facilitate ESD. Collective efficacy refers to the local school organization’s conviction that ESD will have a positive effect on its students’ outcomes, including high expectations of what they can achieve (Verhelst et al. Citation2020).

Turning to Mogren’s (Citation2019) third criterion, progression, the ESD process is assessed as sporadic, continuous, or disrupted. Continuous refers to an organizational process showing a steady improvement; sporadic refers to a process that shifts back and forth in relation to the ESD implementation criteria; and disrupted refers to an organizational process that has come to a halt. Continuous participation has a specific content and is regular over time; sporadic participation is random in terms of content and time; and disrupted means that participation has ended (Miles, Huberman, and Salda Citation2014).

4.3. A whole school approach

A WSA was the ideal in the ESD project explored in this study. A WSA to ESD embraces a holistic and participatory educational philosophy that aims to enhance the potential of the school environment to function as an authentic and meaningful learning place with a sustainable future (Gericke Citation2022). It has been suggested that a WSA to ESD should involve all stakeholders within a school and focus the teaching on authentic problems in wider society, thereby transforming the school itself into an agent of change with a sustainable trajectory (Henderson and Tilbury Citation2004). Hence, a WSA to ESD can be considered as a conception of educational change in the direction of ESD, holding characteristic features that enable the idealized direction of ESD to take place. Through a WSA, a school organization can attempt to ensure the relevance of education for a sustainable society (Sterling Citation2010). From this perspective, a WSA to ESD is seen as a continuation of ESD in the direction of authentic sustainability with respect to the wider society (Mathar Citation2015).

From a theoretical perspective, Mogren, Gericke, and Scherp (Citation2019) described a model of a school organization that could accomplish just that. First, the organization needs to have a common vision: ESD. That vision needs to be negotiated and agreed at all levels of the school, as well as with stakeholders outside the school with whom the school forms partnerships and community links. In this way, the vison can become a holistic idea within the school. Second, this vision needs to be implemented and integrated into the routines and organizational structures within the school organization. Third, the internal organization needs to involve reciprocal exchange with the wider society and respond to changes in and demands from society through professional knowledge creation. If these spaces are in tune and balance one another, the teaching and learning (ESD) at the school will be facilitated by a WSA (Mogren, Gericke, and Scherp Citation2019). In the overall school improvement project, this model was the guiding principle for the WSA.

4.4. School improvement capacity

School improvement studies have identified and categorized prerequisites for successful school improvement (Blossing et al. Citation2015; Fullan Citation2001), constituting a theoretical framework called school improvement capacity (Blossing et al. Citation2015). In this study, this framework was used to analyze and categorize the ESD implementation processes in the five participating schools. This framework also formed the basis for the design of one of the interview guides. Four empirically established themes constitute school improvement capacity: improvement processes, improvement roles, improvement history, and infrastructure (Blossing et al. Citation2015). These themes are used in this study.

The first theme (improvement processes) focuses on the different phases in a school improvement process. There is a dilemma when school leaders (and teachers) perceive the first phase as the whole improvement process, seeing the process as already complete after one semester, as this is a process that can last from 5 to 8 years. In this study, this theme played a pivotal role, as these phases were used to categorize the participating schools’ focus on school leading actions (e.g. organizing cross-curricular activities and teachers’ multidisciplinary collaboration; see Section 4.2) driving forward the WSA to ESD. The phases were also used as a complement to the ESD implementation criteria for assessing the WSA to ESD process. The phases in question were as follows: initiation, implementation, and institutionalization. Events in the first phase (normally 0.5–1.5 years) mainly focus on learning and understanding the WSA to ESD. In the second phase, the initial learning is transformed into practical work. This implementation phase is the most critical phase, as it often means conducting teaching differently within new organizational settings. If the teachers and school leaders overcome the resistance in the implementation phase and persist in working in accordance with the WSA to ESD for 3–5 years, the improvement process eventually moves into an institutionalization phase. The WSA to ESD is assessed as institutionalized when it has become routine and is a norm in the daily work of the school. At this point, it is described as the way we do things at our school.

The second theme (improvement roles) deals with what roles it is possible to take on in school improvement work and how these roles vary in importance during the improvement processes. The different roles are understood as aspects of an extended leadership for change, and they are used to analyze the function of different leading functions in an ESD project. In the initiation phase, the visionary role has the central function of communicating the aim of ESD, thereby creating an essential understanding among the staff. In the implementation phase, when concrete action is required, the inventor role is important in communicating how to put ESD into practice at the local school. These are examples of two roles that are necessary in school improvement processes. It is essential that the principal ensure that the roles that are needed in the different improvement phases are represented at the local school.

The third theme (improvement history) focuses on school improvement as a long process, which motivates the need to keep the local school improvement history alive through documentation and communication. In this way, the school will be able to adapt to new improvement work. The fourth theme (infrastructure) indicates that the local school’s daily life on a structural level is shaped by and shapes the work of students, teachers, and principals. Organizing the school’s infrastructure is a task that falls within a principal’s leading (Forssten Seiser Citation2020). It is about improving the interpersonal relationships in a school.

5. Method

The research design of this study was a follow-up study (Cohen, Manion, and Morrison Citation2007). This meant that the researchers followed the ESD implementation based on a WSA over time during a 3-year school improvement project. Interviews were conducted with school leaders twice: During the project and after the project was finalized, questions about the schools’ improvement histories and infrastructures were asked in interviews in both 2018 and 2020. The theoretical frameworks that are presented in the previous section have their roots in different fields of knowledge. They are united not only through this study’s focus on school improvement and ESD but also by its interest in changes in education and practice. At the same time, their combined use in the analysis of this study provided two different perspectives that together support the possibility of novel findings relating to a WSA to ESD. As mentioned, the theory of practice architectures enabled the researchers to identify what happened in the form of different leading actions. Based on the ESD implementation criteria, a more in-depth analysis and assessment of the processes in the five schools was made possible. The WSA contributed through its holistic approach, including a societal perspective, while school improvement capacity was used for assessing and categorizing the findings.

5.1. Context of the study

The project took place in five schools in a mid-sized municipality in western Sweden and was initiated by the school authority in the municipality. In brief, ESD was introduced in 2016, and the school administration supported and managed the work for 3 years. The WSA was a central focus. The school improvement work was organized and described as regular professional development, including all levels of the school organization and involving and integrating all teaching subjects. It included the greening of the schools and the schools’ connection to the wider society. The participating schools were selected based on dissimilar premises and conditions: Two volunteered based on their interest in the project, two based on their underperformance and low results, and one based on the local school authority’s judgement that the school required more progressive teaching. The five schools (A–E) together covered the compulsory (grades 1–9, students aged 7–16 years old) and upper secondary (grades 10–12, students aged 17–19 years old) school system in Sweden. A project leader and an assistant project leader were appointed to lead the processes in the municipality. They organized network meetings and founded ESD conferences that included all participants regularly (each semester) during the project. In the conferences, different ESD experts from Non-Government Organizations (NGOs) and universities were invited to speak, elaborating on what ESD is and how it can be taught and implemented in schools. In the participating schools, local ESD facilitators were selected, with the overarching task of supporting their teacher colleagues in developing actions for ESD in the schools. These facilitators, one or two in each school, were appointed on the basis of 10–20% of their working hours being allocated for this duty at their school, and they met the teachers at each local school every month during the project.

Another important strategy was engaging the school principals, encouraging them to participate in the work and take the lead along with the local facilitators. In the beginning, the project leaders met all the facilitators jointly, but during the process, due to the schools’ different organizational settings and dissimilar conditions, these meetings changed and became divided based on the type of school. The project leaders regularly met the participating principals in a network in which the principals could exchange experiences and support one another in leading ESD. The project leaders provided research and acted as the principals’ critical friends. A critical friendship includes a personal relationship involving confidence and belief in the professional competence of the critical friend, expectations of personal integrity, and basic trust in the good intentions of the critical friend (Handal Citation1999). Dilemmas arose during the process: For example, few of the principals remained at their schools, and there were almost no immediate handovers between the resigning and newly appointed principals. Another challenge was that there was resistance to work on ESD in some of the schools, both from the teachers and from a new principal.

5.2. Participants and data collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted twice, first in 2018 and again in 2020. In the first round of interviews, ESD was still being monitored by the school authority in the municipality, but this was no longer the case in 2020. Two of the authors carried out the interviews. The author who was responsible for the interviews in 2018 was a researcher in ESD, while school improvement and school leadership were special interests of the author who conducted the interviews in 2020 (). In 2018, the interview guide was based on school improvement and leadership actions applicable to ESD (Mogren and Gericke Citation2017a, Citation2017b). In 2020, this interview guide was supplemented by a focus on school improvement capacity (Blossing et al. Citation2015), enabling a closer examination of each school’s infrastructure. The interview guides can be found in Supplementary 1.

Except for the principal in School B, all the school leaders were interviewed twice. The concept of school leader was used as a common concept to describe the roles of school intendent (the principals’ immediate manager), assistant principal, and principal. The total length of the seven interviews conducted in 2018 was 3 hours and 21 minutes. In 2020, the total length of the eight interviews amounted to 6 hours and 36 minutes. It should be noted that in some schools, the leaders included more than one principal. One of the principals in School E ended the assignment 2 months before the last interview, but as their experience was of relevance for this study, they were included in the second round of interviews nonetheless.

5.3. Data analysis

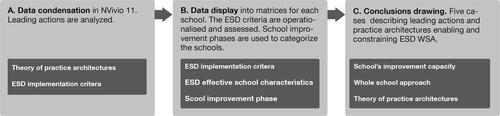

The recordings from the interviews were transcribed and analyzed by the authors. In the analysis, the methodology provided by Miles, Huberman, and Salda (Citation2014) was used: data condensation, data display, and conclusion drawing. is a schematic description of the analysis process, illustrating how the theoretical framework was used to derive data concerning school leading in the implementation of ESD. The analysis process is pictured in and described in detail in the following sections.

In the first analytical step, data condensation (Step A in ), leading actions (sayings, doings, and relatings) were identified through the use of the theory of practice architectures (Kemmis et al. Citation2014). For a more detailed analysis, the actions were coded in line with the ESD implementation criteria (coherent school organizations, participation, and progression; Mogren Citation2019). This step was conducted using the NVivo 11 data program, and all transcripts were analyzed and coded separately and chronologically for each school. To make the coding sharper, the researchers individually coded the same data and then compared and discussed the coding.

The second analytical step, data display (Step B in ), involved compressing the data into matrices and visualizing similarities and dissimilarities between the schools. Two of the ESD implementation criteria (coherent school organizations and participation) were operationalized using the ESD-effective school characteristics: sustainable leadership, school resources, pluralistic communication, supportive relations, democratic decision-making, shared vision, adaptability, and collective efficacy (Verhelst et al. Citation2020). For further information on the operationalization process, see Section 4.2. Progression was the third and final ESD implementation criterion that was used in the analysis. This was assessed as continuous, sporadic, or disrupted (Forssten Seiser and Blossing Citation2020; Miles, Huberman, and Salda Citation2014) in terms of a WSA. In addition, the school improvement phases (initiation, implementation, and institutionalization) were assessed in each of the participating schools. zooms in on the data display.

An abbreviated version of one of the matrices constructed in the data display can be seen in Supplementary Table 1, using school A as an example. The original matrices consisted of between four and seven pages.

Table 1. Respondents.

These matrices were then used as foundations for the third analytical step, conclusion drawing (Step C in ), where thick descriptions (Yin Citation2012) were constructed in the form of five cases, one for each participating school. These cases were categorized based on each school’s improvement capacity (Blossing et al. Citation2015), with a focus on their improvement phase. The cases unfolded whether or not a WSA to ESD had become institutionalized in the schools’ daily work. Once again, the theory of practice architectures was used (Kemmis et al. Citation2014), focusing on the leading actions and practice architectures that appeared as substantial in terms of enabling or constraining the achievement of a WSA to ESD. The three intersubjective spaces in which practice architectures appeared were used to frame prominent arrangements. In terms of semantic space (Sayings), different cultural–discursive arrangements were identified through the language and concepts used in the interviews, which were then examined as enabling or constraining in relation to the WSA to ESD processes. In terms of physical space, material–economic arrangements became visible in the leading actions and work that had been conducted in the local schools (Doings). In terms of social space, social–political arrangements were identified through descriptions revealing how different functions and roles related to one another (Relatings). These actions were explored and evaluated. Authentic quotations from the interviews have been added to provide evidence for the results (See Section C in and Supplementary Table 1). Interviews conducted in 2018 are marked with ‘(1)’ after the citation, while ‘(2)’ refers to interviews conducted in 2020.

6. Results

The following section consists of five cases addressing the first research question: How did the implementation processes of ESD appear at the local schools from a leading perspective? The theory of practice architectures (Kemmis et al. Citation2014) was used to unfold what happened in the local school’s ESD implementation process. The focus was on school improvement capacity (Blossing et al. Citation2015), with an emphasis on descriptions concerning improvement roles, improvement history, and infrastructure. Another focus of the study was school leading, so leading actions were placed in the foreground.

The cases were categorized into three categories based on how the school’s WSA to ESD implementation process was assessed. As described in the theoretical section, this assessing procedure was carried out using a combination of the ESD implementation criteria (Mogren Citation2019) and school improvement capacity (Blossing et al. Citation2015). More specifically, the progression in the five schools was assessed in three steps (continuous, sporadic, or disrupted) while the framework describing improvement phases (initiation, implementation, and institutionalization) facilitated the assessment of the process at the end of the study in 2020. An overall picture of the assessments can be found in .

Table 2. Assessment of the implementation processes in the five schools.

The cases are presented in a ranking order, starting with the schools that were analyzed and assessed as the most successful schools in relation to the implementation of a WSA to ESD. The cases are followed by a description of the practice architectures that were identified as enabling or constraining a WSA to ESD.

6.1. Continuous progression and institutionalized ESD

Two of the five schools in the study showed such signs of improvement, both in the local school organization and in the degree of participation facilitating ESD, that the progression was assessed as continuous (Mogren Citation2019). In both of these schools, ESD had become routine and institutionalized (Blossing et al. Citation2015), even if there were significant differences between Schools A and B.

6.1.1. School A

In this school, the principal was involved and engaged in ESD. The principal described how ESD permeated everything that was going on at the school every single day. According to the principal, every leading action undertaken had ESD as a starting point. The school was characterized by a high degree of participation and commitment among both staff and students. The principal described how small but strategic actions rendered big improvements. One example was how everyone seeking employment at School A was informed about ESD. If the applicant was critically inclined or doubtful, it was recommended that they apply to another school. ‘At job interviews, I talk about a holistic focus and how our work is based on ESD and inform them that this is how you should work if you want to work in our school’ (2). One activity provided an example of how students were included: ‘Our leisure time center has been plastic-sanitized, and the children have been involved in the whole process, right from the beginning’ (2). The principal was employed by the school in 2018. At this time, the ESD project was already running, and the school had an organization that was coherent with ESD. As the principal had earlier worked as a principal in a participating preschool, they were well informed about the project, and it was easy for them to get involved in the ongoing ESD process.

Already in 2018, the local ESD facilitators emerged as having a very important role due to the function of the school’s ESD group. The ESD group decided what theme would be the focus of the upcoming 4 to 6 weeks. This group expanded, and by 2020, it included the leisure-time center, which was a vision expressed in 2018. Another development was that the number of facilitators had increased, and by 2020, all teacher teams were represented in the group, which resulted in higher participation. Students’ thoughts and ideas were expressed through the student council.

In 2018, the principal emphasized the importance of the project leader, who had a deep knowledge of ESD, and was concerned about what would happen when they no longer had access to this person. But this did not seem to become a problem, and in 2020, the whole staff was committed to ESD, including those responsible for school meals:

The chef is not using any semi-finished products but cooking all from the scratch. Everything is taken care of; almost no food is wasted. Locally produced products and fruit that the local shop can no longer sell are used for making smoothies. They make lunchboxes from leftovers and sell them to the teachers. In this way, nothing gets wasted. (2)

6.1.2. School B

In School B, the principal was hired in 2019 and entered the process late. For them, ESD represented a new way of organizing and understanding education and teaching. The local ESD facilitators were described as skilled and as an important leading resource. In 2020, ESD had developed into a routine in the form of cross-curricular themes that were repeated each semester and included in the annual schedule: ‘It runs by itself now’ (2). Commenting on ESD, the principal talked about sustainability for the individual, the community, and the planet, as well as about societal development with a focus on equality, health, and well-being. They talked about teachers challenging and motivating students to reflect on equality, how equality was connected to health, and how this was put into practice in the form of assignments.

The principal’s confidence in the facilitator had resulted in delegated ESD leading: ‘I find it important to have someone responsible to lead this [ESD] at the school’ (2). As the school was relatively small, it required a slim organization to keep ESD running. One facilitator using 10% of their working hours was, according to the principal, sufficient. The fact that the facilitator was the same person over time seemed to have had an important impact on the improvements that were made. Their cooperation was mostly delimited to organizing time, including themes in the yearly agenda, and ensuring that both students and teachers had time in their schedules for working in themes. The principal was operative when problems or dilemmas arose: ‘Sometimes I have to organize time and perhaps manage teachers who are not collaborating or so on. must deal with things like that’ (2). The facilitators had organized ESD so that all teachers were invited to discuss and decide the upcoming theme. This was often done in the form of workshops. The themes were cross-curricular and organized in periods of 2 weeks for each grade. It was up to the teachers to decide if they wanted to join the themes, so long as their absence did not disadvantage the students. The rest of the teaching time was conducted traditionally in subjects.

6.2. Sporadic progression and a re-implemented ESD

One of the five schools in the study, School C, showed signs that the ESD process had slowed down and faded but that energy and resources had once again been invested. The most significant sign of this was new funding that had been used to increase the number of facilitators. In 2018, all teachers were expected to participate in the project, but when resistance grew among the teachers, the process changed, and in 2020, it was up to the teachers to decide whether or not they wanted to join the ESD work. The progression in School C was assessed as sporadic. It was interesting that despite this regression, the school leaders appeared to be equally committed in 2020 compared to in 2018. The SDGs were mentioned by all school leaders in 2020 and described as the foundation for how the teachers should teach and select cross-curricular themes.

6.2.1. School C

In 2018, the school was managed by one principal and three assistants. The latter were those who were interviewed in 2018. The assistants described the school as performing well, with skilled teachers and motivated students, which was still the case in 2020, despite the school undergoing an extensive organizational change where two upper secondary schools were becoming one large one. This organizational transformation contained fundamental changes in the form of new school buildings with architecture offering big open spaces were students could collaborate. Another essential change was that teachers teaching the same educational program were sharing workspaces. This change was promoting a student-focused approach and stimulating collaboration and cross-curricular activities among the teachers: ‘When you visited the school in 2018, the organization was completely different. The teachers were organized in subject institutions. Today, they are organized around the students’ (2). This organizational change corresponded well with ESD. In 2018, two of the three assistant principals had worked for several years in the school, and in 2020, all three were still there, even if there had been some changes in their formal assignments. Two of the former assistant principals had been appointed principals, and the third was now the school intendent, which meant that they were managing the overall school organization.

When the school leaders were asked in 2020 to describe how ESD could be seen in practice, they described how students had organized a clothes-swap day and how an active student council had achieved changes in school lunches, resulting in a sharp reduction of meat dishes and a significant increase in vegetarian dishes.

Even if the school leaders in 2018 were critical of the top-down management of ESD, they found it important, as the vision was to develop change and move ‘from lessons to learning’ (1). The forthcoming organizational change was a focus of the first interviews, and it was obvious that the school leaders were looking forward to this. In 2020, the school leaders were still positive about the new organization but expressed how the transition had been a challenge. There were traditions and a resistance to change among some of the teachers, emerging in the form of confrontations and conflicts. The traditional way of working was individually, with a strong focus on subjects. ‘The teachers don’t like to share their workspaces, and we have endless discussions of this kind’ (2).

There were teachers who resisted working in a cross-curricular and collegial way, and this was mentioned as one explanation of why the ESD process had slowed down in 2020. Another explanation was a decline in resources. At one point, there was only one ESD facilitator in the new school organization. Thanks to new funding, applied for by the school leaders, the number of facilitators had increased, and in 2020, there was one in each teacher team. The ESD facilitators were responsible for planning and organizing regular cross-curricular themes using the 17 SDGs (United Nations Educational and Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Citation2017) as the basis, and 10% of the facilitators’ working time was dedicated to this assignment. However, it was a challenge to get all the teachers engaged: ‘It is difficult to get more than two or three subjects involved, and they do this for a short period, and it is linked to individual teachers’ (2). The facilitators had meetings with the relevant principal, but there was variation in how often they met. The principal who more frequently met with the facilitators saw their task as to support the facilitators, as they were the ones who had to handle teachers’ resistance to this new way of working. They advocated shared leading as a necessary strategy to change the top-down school management: ‘I don’t know the answer. We must do this together. If I had the answer, we should already be working this way. We need to build this together’ (2). Two of the school leaders claimed that some of the themes had been institutionalized, but the third was critical of the fact that ESD had not performed as expected: ‘I find it hard to get ESD to an extent … we are still not there’ (2).

The expectations for ESD were expressed in terms of sustainable learning and sustainable development. There was a consensus among the school leaders that it included students’ knowledge and development: ‘They [students] should conduct studies in a way that is sustainable for themselves. You want the students to become citizens who think and act sustainably’ (2). There was also consensus on cross-curricular methods, collegial cooperation, and ‘sustainability in all aspects: economic, social, and ecological’ (2).

6.3. Disrupted progression and an expired WSA to ESD

In two of the participating schools, ESD had slowly faded, and there were only weak signs of the process remaining in the schools. Neither of these schools entered the project of their own free will, as they were regarded as underperforming, and ESD was used as a strategy to improve their results. The two schools had both similarities and differences in their processes, which are made visible in the following case descriptions.

6.3.1. School D

This school had been struggling with a bad reputation, which had resulted in principals coming and going, and it was a challenge to find skilled teachers. The municipality decided that the school should participate in ESD due to its status as a low-performing school. In 2018, the interviewed principal had just replaced the former principal as a consequence of an inspection conducted by the Swedish School Inspectorate. In the inspection, several serious deficiencies were identified, which resulted in negative media attention. The school inspectorate advocated that the interviewed principal, who had been an assistant during the inspection, take on the assignment. As a result of this, in combination with the municipality promising all necessary resources, the principal decided to take on the challenge: ‘I would not have applied for the assignment if I hadn’t already noticed the things that the inspectorate stressed’ (1). Later, the promise from the municipality turned out to be mostly empty words, according to the principal.

As a consequence of high mobility among the principals, the school had participated in many different projects, few of which had become institutionalized. Another consequence was that teachers were not used to sharing responsibility and leading, according to the principal. The principal had been regarded as a solitary leader, which was now being challenged by the new principal: ‘We must work together, and we have to link everything we do to our goals in school and in the world’ (1). Teachers not comfortable with this change were encouraged to apply to other schools, which had happened by 2020. A collaborative culture and shared responsibility were also promoted by the inspectorate, which corresponded well with ESD.

But what happened was that the ESD project became outcompeted by a new project that arrived at the school. This project, founded by the Swedish government, was carried out under the acronym SBS (Samverkan Bästa Skola [collaboration for the best school]). This new SBS project was related to an inspection that had recently been conducted, and as the main focus was to pass the next inspection, it received all the attention. The ESD facilitators turned into SBS process leaders, and their assignments transformed to focus on assessment for learning and other strategies to correct the deficiencies identified by the inspectorate. By 2020, SBS had become the main school improvement project. The work was described as so successful that all other inspection-related topics had become less urgent. The principal saw themselves as a gatekeeper, protecting and retaining the focus on SBS. According to the principal, no one was talking about ESD any longer. When the principal reflected on what had happened, they expressed how many things had become transformed at the expense of ESD, although one part of the work in the new project could be seen as a remnant of ESD: ‘On the surface, one could say that we are not a part of that project or we have nothing left of it. On the other hand, everything is actually a product of sustainability’ (2). The fact is that the school organization was in some minor aspects coherent with ESD, but this did not apply for all subsystems in the school’s infrastructure. The general pattern was that the school organization and the school leaders were no longer facilitating ESD in the necessary manner for it to continue.

6.3.2. School E

There were striking similarities between School E and School D. Both were low-performing and struggling with bad reputations and newly conducted inspections. Moreover, both had been requested to join the ESD project as a strategy to improve their outcomes. Both schools had a history of high staff turnover, and leaders in both schools were engaged in the new governmental project SBS, resulting in low engagement with ESD. ‘If anybody had asked me if we wanted to participate in ESD in autumn 2016, then I would have answered no, we don’t want that. But the question was never raised’ (2). However, the schools differed in location and in the composition of their students. School E was multicultural, with approximately 40 languages spoken, and the majority of students had a mother tongue other than Swedish. The school’s two principals spoke of this in positive terms but said that it led to some complications. One was that parents and students sometimes chose other schools; another was that ‘both students and teachers have lowered their expectations and settled on a fairly low level’ (1). The teachers were organized in teams around subjects, and there was a dominating individualistic culture among the staff. In 2018, the school’s only ESD facilitator initiated cross-curricular theme weeks focusing on language development with regard to the school’s multicultural composition.

In the same way as School D, School E had a history of many projects, which could explain why ESD had not been popular when it was presented to the teachers: ‘At that time, there had been a new project almost every six months, so just the word project made people scream’ (1). Moreover, in the same way as in School D, the two principals in School E saw themselves as gatekeepers. They explained that in 2018, when they were newly employed, they actually did not know that ESD was running, as no one had informed them about it, and it was not visible in practice.

When the principals in School E described what was most urgent to improve in their school, they pinpointed the need to provide their students with the same possibilities as other students in the municipality. Sustainability was described as a sustainable education: ‘It is the teaching that needs to be sustainable. Expectations are also connected with sustainable learning’ (1). In 2020, one of the principals had left the school for a new assignment, and the other one would leave at the end of the semester. In addition, the ESD facilitator had left, and no new facilitator has been assigned. Instead, there were process leaders connected to SBS, as at School D. According to the principal who had resigned, this had been a positive change, as the ESD facilitator had never succeeded in engaging the teachers: ‘Instead, ESD became a theme that we talked about in different arenas but never actually implemented in practice’ (2). The principals did not think that ESD was a wise strategy, as it was not compatible with their authentic needs. Furthermore, they were critical of how it was initiated: ‘The design did not suit us. We were very different compared to the other [participating] schools … here there was so much resistance, so we had to transform it’ (2). As in School D, there were signs of a pattern that was compatible with ESD, in the form of making education more relevant for students, but this was not to such a degree that the progression could be assessed as continuous or sporadic. The pattern was that the ESD process had slowly slowed down and then more or less vanished.

6.4. Enabling practice architectures

The function of leading practices was of interest in this study. But leading practices include more than actions conducted by school leaders. They also include the practice architectures that prefigure school leading. In this section, the ESD implementation criteria (Mogren Citation2019) are used as categories to respond to the second research question exploring the practice architectures that enabled and constrained progression in the WSA to ESD processes.

6.4.1. Coherent school organization

ESD-effective schools show that sustainable leadership, school resources, pluralistic communication, and adaptability are important features (Verhelst et al. Citation2020), which was confirmed in this study. In the schools where WSA to ESD had become routine (Schools A and B), enabling practice architectures were identified in the form of grouping systems (doings; a material–economic arrangement) that supported cross-curricular activities and continuous or scheduled recurring themes. There were also clear communication systems (sayings; a cultural–discursive arrangement), promoting a WSA to ESD and spreading the SDGs. This supported the development of a shared vision and helped create engagement and awareness among both staff and students. Shared leading (School A) and delegated leading (School B) were examples of strategies within the social space in the form of social–political arrangements that confronted the idea of a solitary leader and secured sustainable leading by sharing knowledge and demonstrating the ability to integrate the past with the present. Many leading actions challenged individualistic traditions and norms, and by 2020, these schools had a collegial norms system that was enhancing collaboration among staff and students. The financial gains that were to be seen in School A were a noteworthy example of adaptability, illustrating how ESD can be used as a material–economic arrangement and as a strategy within the physical intersubjective space for using school resources wisely and sustainably. Leading actions had over time slowly turned into practice architectures in the form of coherent school organizations that by 2020 were helping the school leaders in School A and School B to overcome situations that could threaten the WSA to ESD.

By contrast, the schools with high mobility among the principals and where teachers worked mostly individually, organized only around their subjects, were examples of practice architectures that in the best case rendered only a sporadic ESD progression. However, as seen in School C, sporadic progression was not enough to overcome the likely resistance (relatings; a social–political arrangement) in the implementation stage. If this occurs, school leaders must have the competence and strength to once again introduce initiation strategies or other arrangements, adding new energy to the work. Lack of engagement and participation will lead to a progression that stops, and ESD will vanish from the local school, perhaps outcompeted by a new project, as at Schools D and E.

6.4.2. Participation

Research on ESD-effective schools (Verhelst et al. Citation2020) has shown that supportive relations, democratic decision-making, a shared vision, and collective efficacy are characteristics of a successful ESD process and examples of enabling arrangements. In this study, these characteristics were used for analyzing how people encountered one another as social beings in relationships and through participation in various facilitating social–political arrangements (relatings). Collective efficacy emerged as high in the schools with a continuous progression (School A and School B). This was made apparent in the positive language and ideas describing ESD. It was also apparent in the outspoken conviction that ESD was having a positive impact on students’ outcomes and learning (sayings). These were two examples of the identified enabling cultural–discursive arrangements within an intersubjective semantic space. Furthermore, there was collegial collaboration that included professions other than teachers. Students were included in the schools’ democratic decision-making systems and involved in choosing themes. The school cultures were characterized by trustful and supportive relations, which also extended beyond the schools. The individuals’ actions and relations with one another within an intersubjective social space were examples of the social–political arrangements (relatings) that were identified. Finally, the ESD vison (sayings; a cultural–discursive arrangement) was shared by many, and there was a common understanding and joint commitment connected to how the work should be conducted. Leading activities promoting participation had over time transformed into flourishing environments, in the form of practice architectures enabling the WSA to ESD.

In the schools where the progression was disrupted (School D and School E), low expectations and low engagement characterized the speech about ESD, if there was any communication on this at all. Neither of these schools had entered the ESD project voluntarily. Such factors (sayings; cultural–discursive arrangements) emerged through the language and speech surrounding the ESD processes in both schools, as well as in how people related to one another and to the ESD implementation processes (relatings; social–political arrangements). The pattern was that by 2020, almost no one was mentioning ESD. The schools had traditionally bad reputations, which complicated collaboration and trustful relations with others, not only outside the schools but also within the schools. The teachers wanted a solitary school leader, and they were not keen on distributed leadership or shared responsibility. Bad reputations and low performance had resulted in organizations with low self-esteem. External pressure to deliver high outcomes and high mobility among the school leaders had contributed to the creation of many new projects and the fact that ESD no longer existed at these schools.

7. Discussion and implications

Literature on a WSA to ESD often lacks a foundation in educational theory on how a school works as an organization (Gericke Citation2022). Therefore, in this study, applied theories from the field of school improvement research were used to study a WSA toward sustainability. The study showed how successful leading involved conducting suitable actions and adapting appropriate leading based on the specific contexts for supporting the continuous progression of a WSA to ESD. The majority of the strategies used by the school authority in the municipality were general or even identical: the same project leaders, attendance at the same conferences, listening to the same ESD experts, and local ESD facilitators. Despite the many similarities, the results showed significant difference in the participating schools. Therefore, in accordance with Verhelst et al. (Citation2020) and Gan (2021), this study emphasizes the importance of not only the local school organization but also the surrounding arrangements (practice architectures) affecting the local school, as well as awareness of how the transition from leading actions to practice architectures is a slow and conscious process. In another study of the current project, similar results were found at the teacher level (Gericke and Torbjörnsson Citation2022a, Citation2022b). By interviewing teachers, it was found that local preconditions exerted an external pressure on the ESD implementation processes in some of the schools and that the continuous school improvement projects lacked mechanisms—or practice architectures—enabling the evolution of the school improvement processes (Gericke and Torbjörnsson Citation2022a). Therefore, in line with Müller, Lude, and Hancock (Citation2020) and Burns, Diamond-Vaught, and Bauman (Citation2015), this study emphasizes the need for school leading that promotes new ways of thinking and expressing (sayings) on how to organize education, as well as new ways of conducting actions (doings), leading, and building new kinds of relationships (relatings) between all those who inhabit or affect schools’ daily lives as they strive to realize a WSA to ESD.

One aim of all school leading should be enhancing the local school’s capacity to improve (Blossing et al. Citation2015). The results from School A revealed how a well-known improvement history enabled the progression of a WSA to ESD despite mobility among the school leaders. The new principal was well informed and could continue a process that was already running. This is a central conclusion in times when principals’ mobility in Sweden is higher than ever before (Thelin Citation2020). A well-known, and hopefully well-documented, improvement history promotes knowledge and awareness of the whole organization, which supports sustainable leadership. Schools’ capacity to improve also includes awareness of how an improvement process runs in different phases.

7.1. Developing guidelines for a WSA to ESD

Based on the empirical results from this study, and by connecting them to theories of school improvement research (Blossing et al. Citation2015; Forssten Seiser and Blossing Citation2020; Harris Citation2001; Hopkins Citation2007), this section contains certain guidelines that have been constructed that can drive a WSA to ESD process forward. The guidelines are outlined under the respective school improvement phases, emphasizing that these do not follow one another in a straight line but rather overlap. Building on the empirical results from this study, and with the support of practice theory (theory of practice architectures; Kemmis et al. Citation2014) and theory from school improvement research (school improvement capacity; Blossing et al. Citation2015), the guidelines address how schools function as organizations and provide practical insights into how to lead and implement WSA to ESD processes in local schools. Included in each stage are examples of the functions of different improvement roles. The study demonstrates how the infrastructure model can be used as a tool for leading improvement processes. Finally, a well-known and well-documented school improvement history is understood as a necessary prerequisite for planning, designing, and leading the process.

This study builds on the school leaders’ experiences and takes a novel process perspective from developed theories within school improvement research to suggest how a WSA to ESD can be implemented in a school over time. The theories and their implications are accompanied and compared with empirical findings from this study to further elaborate on the practical implications for local school reforms promoting a WSA to ESD.

7.1.1. Initiation of a WSA to ESD

In terms of time, activities in the initiation phase can last from half a year to up to 1 year, depending on the school and the context (Blossing et al. Citation2015). The aim in this phase is to create curiosity and an interest in ESD. In the current project, this was done by arranging ESD conferences for all participants, inviting ESD experts to give speeches, arranging study visits to ESD-effective schools, and organizing workshops. These are good examples of leading activities in the initiation phase, with the aim of orchestrating practice architectures for facilitating the process (Wilkinson Citation2019).

In the initiation phase, the role of the visionary is necessary. In the current study, the project leaders took on this role, promoting knowledge and a common understanding of ESD in the schools. The project leaders were external change agents with special ESD knowledge. This is a suitable strategy when the general level of knowledge of ESD—as well as the school’s capacity to improve—is low. However, this strategy implies that the external change agents should be slowly removed and that the leading should be consciously handed over to the local school (Blossing et al. Citation2015; Hopkins Citation2007), as in Schools A and B, where the principals and the facilitators were by 2020 the ones leading the ESD work.

In the initiation, there will be progressive teachers who want to put ESD into practice at an early stage, operating as inventors and early appliers, who can be compared to Wickenberg’s (Citation2013) souls of fire. These should be encouraged and given support, as they are likely to become the school’s internal ESD experts or facilitators. This is what happened in the schools with a continuous progression (Schools A and B)—and also to some degree in School C, where the progression was disrupted. But these teachers cannot implement ESD on their own; instead, a facilitating organization and supportive leading actions (Mogaji and Newton Citation2020) are essential to drive the ESD process forward.

Activities that promote the development of shared ESD leading within the intersubjective social space are advantageous due to the fact that the next phase in the process is critical and often conflict-filled. It is often then that the progression starts to shift back and forth, so a united and committed school leadership team is a prerequisite for a continued progression (Mogaji and Newton Citation2020).

7.1.2. Implementation of a WSA to ESD

The transition to the implementation phase means that all that was taught in the initiation phase should now be put into practice. This phase needs endurance, as research has shown (Blossing et al. Citation2015; Hopkins Citation2007) that it can last up to 7 years.

In this phase, it is no longer enough if only progressive teachers have an ESD approach in their professional work. Every teacher must now begin to work in line with ESD. This clarifies why the implementation phase is often conflict-filled, as some teachers are not yet prepared to change how they conduct their teaching. If being an expert in a subject is still the prevailing norm (as in School C), this will constrain the progression. This means that there is a resistance to working collegially on cross-curricular themes. The role of the driver is necessary when defense mechanisms are starting to work (Blossing et al. Citation2015). The driver’s function is to ensure that everyone is starting (or at least trying) to work according to ESD. From a leading perspective, it is important to stick to what has been learned in the initiation phase. This involves organizing teachers in cross-curricular teams. Cooperative activities need to be promoted by school leaders, and regular professional development in the form of seminars, conferences, and similar activities needs to continue. The aim is to develop a collaborative culture, challenge individual norms within the social intersubjective space, and reflect on how people relate to one another and to ESD.

Some of the conflicts will eventually transfer to the teacher teams, with the consequence that a large responsibility falls on the local ESD facilitators. This means that school resources need to be used to appoint enough facilitators to handle and overcome these kinds of conflicts (Verhelst et al. Citation2020). Being a facilitator is an exposed position, as it means challenging your own colleagues (Blossing et al. Citation2015). A sign to pay attention to within the semantic intersubjective space is when teachers argue that ESD is not anything new but the way they have always worked. This could be an indication of ESD turning into window dressing, meaning that things that may look like ESD (e.g. decorating walls with SDGs) are not necessarily the same as conducting ESD, a point often referred to by teachers in some of the schools in this project (Gericke Citation2022). Similarly, in another study of the teachers in the project, it was found that a focus on language education was used as window dressing for ESD (Gericke and Torbjörnsson Citation2022a). Therefore, it is important that the facilitators and the principal meet regularly for joint reflection and analysis. It is also essential that there should be a leading community that provides mutual guidance on how to act wisely. Operative and engaged principals in the actual work that takes place, like the principal in School A, are endorsed by this study. A democratic decision-making system is a wise strategy for establishing trustful relations, as it ensures that individuals know that they can influence the work that is performed. A professional confidence in the organization and the ability to mobilize adaptability to respond to external demands that may threaten the WSA to ESD (Gericke and Torbjörnsson Citation2022a, Citation2022b) are vital for the process.

Empirically, it can be seen that time issues, as a material–economic arrangement, are central when investigating teaching practices in the same schools (Boeve-de Pauw et al. Citation2022). From another study using questionnaire data, it was seen that teachers’ self-efficacy in terms of practicing ESD first increased but then fell back when the teachers in their regular professional development recognized the complexity of ESD and the changes needed to implement it (Gericke and Torbjörnsson Citation2022a, Citation2022b). Moreover, the teaching practices were only starting to be changed by the end of a 3-year project (Boeve-de Pauw et al. Citation2022). These results, in combination with the results of this study, show the need for long-term horizons when implementing ESD in accordance with a WSA.

7.1.3. Institutionalization of a WSA to ESD

If and when the actions and the work in the implementation phase develop into routines that are described as how we do things around here, the WSA ESD process is regarded as successful (Blossing et al. Citation2015) in practice (i.e. in terms of sayings, doings, and relatings). This is what had happened in Schools A and B. The WSA to ESD was no longer new, and it was not regarded as a project. In School A, the WSA to ESD included the whole staff, the students, and others from outside the school, such as the local grocery shop.

From a school leading perspective, even if the WSA to ESD has reached the institutionalization phase, there is no time to relax, as local schools are constantly exposed to external demands. Leading activities promoting regular professional development, collegial collaboration, and cross-curricular activities still need to be in focus, as new projects are always a competitive factor, as in Schools D and E. Accountability, marketization, and quality are arrangements that have been brought into the Swedish school system, turning school outcomes into competitive factors (Forssten Seiser Citation2021). High quality is often measured and described in the form of student outcomes, and school leaders need to be able to meet demands in the form of quick results and proposals for new projects that are seen as magical solutions.

This individual focus contrasts to a collective perspective and, in some ways, to the formation of future citizens. Based on this study, it is claimed that a WSA to ESD can resolve contradictions such as these by providing a conceptual foundation that includes both perspectives: the interests of each student and the interests of society. However, to reach success in an ESD process, schools need the capacity to improve (Gericke Citation2022) and shared leading that has the ability to integrate the present with the past, while at the same time keeping a focus on the future.

This study has shown how practice architectures prefigure practices by facilitating and constraining a WSA to ESD. Moreover, it has been able to identify specific enabling practice architectures. The results revealed how school leading was about arranging—or orchestrating—practice architectures in ways that enabled a WSA to ESD, where the overall aim was the transition of schools into authentic and meaningful learning places contributing to a sustainable future. The study also showed that to accomplish this, issues of time and endurance were pivotal. Most studies on ESD implementation involve case studies of short projects. However, the researchers consider that a period of 3 years, as in this study, should be the minimum; indeed, a time perspective as long as 7 or 8 years may be needed for institutionalizing ESD if schools’ surrounding practice architectures are unfavorable.

8. Concluding remarks

To conclude, this study has contributed through practical guidelines on how to lead and implement WSA to ESD processes in local schools, moving from initiation to implementation and, finally, institutionalization. However, this was a longitudinal follow-up study including five schools, and there may be many aspects of this process not shown in the current study. Therefore, there is a need for further research on how to institutionalize a WSA to ESD in such a way that it becomes the way people do things here. The researchers advocate multidisciplinary studies contributing through new perspectives and findings with a focus on the functions involved in leading a WSA to ESD in school organizations. A limitation of this study is that no interviews were conducted with the ESD facilitators or the teachers, with the empirical data solely consisting of the principals’ statements. To fully comprehend the WSA to ESD perspective, these actors should also be investigated. Thus, the researchers advocate further research involving ESD facilitators, teachers, and students, as well as studies involving observations.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (1,012.6 KB)Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anette Forssten Seiser

Dr. Anette Forssten Seiser is a senior lecturer in Educational Work at the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, at the department of Pedagogical Studies and the leader of SOL (School development, Organization, Leadership) research at Karlstad University. Her research is in the fields of school leadership and school improvement, conducted at local schools as well as in governments projects, often with a focus on the role and function of school leaders in different teaching research initiatives. She is frequently involved in action research.

Anna Mogren

Dr. Anna Mogren is a lecturer in the field of Educational Work at the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, at the department of Pedagogical Studies at Karlstad University. Her research interest is School Improvement and Education for Sustainable Development, ESD. She is a member of the research group SMEER https://www.kau.se/smeer and SOL https://www.kau.se/sol/forskargruppen-sol. She has a long experience of practical school improvement in ESD and collaborate with national school authorities as an expert in the field.

Niklas Gericke

Dr. Niklas Gericke is Professor in Science Education at the department of Environmental and Life Sciences, and Director of the SMEER (Science, Mathematics and Engineering Education Research) research Centre at Karlstad University in Sweden and visiting professor at NTNU in Trondheim, Norway. His main research interests are biology education and sustainability education from conceptual, teaching as well as implementation perspectives.

Teresa Berglund

Dr. Teresa Berglund is a senior lecturer in biology and environmental and sustainability education at the Department of Environmental and Life Sciences, Karlstad University in Sweden. Her research area is education for sustainable development, with a focus on teaching, learning and implementation perspectives.

Daniel Olsson

Daniel Olsson is a PhD in biology education and a senior lecturer in biology, environmental and sustainability education at the Institution of Environmental and Life Sciences, Karlstad University Sweden. His research interest includes young people’s perceptions of environmental and sustainability issues and how education can be improved and developed in schools to empower environmental citizenship and action competence for sustainability among people.

References

- Blossing, U., T. Nyen, Å. Söderström, and A. Hagen Tønder. 2015. Local Drivers for Improvement Capacity: Six Types of School Organisations. Cham: Springer.

- Boeve-de Pauw, J., D. Olsson, T. Berglund, and N. Gericke. 2022. “Teachers’ ESD Self-Efficacy and Practices: A Longitudinal Study on the Impact of Teacher Professional Development.” Environmental Education Research 28 (6): 867–885. doi:10.1080/13504622.2022.2042206

- Burns, H., H. Diamond-Vaught, and C. Bauman. 2015. “Leadership for Sustainability: Theoretical Foundations and Pedagogical Practices That Foster Change.” International Journal of Leadership Studies 9 (1): 88–100.

- Cohen, L., L. Manion, and K. Morrison. 2007. Research Methods in Education (6th ed.). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Diamond, J. B., and J. P. Spillane. 2016. “School Leadership and Management from a Distributed Perspective: A 2016 Retrospective and Prospective.” Management in Education 30 (4): 147–154. doi:10.1177/0892020616665938

- Eilam, E., and T. Trop. 2010. “ESD Pedagogy: A Guide for the Perplexed.” The Journal of Environmental Education 42 (1): 43–64. doi:10.1080/00958961003674665

- Forssten Seiser, A. 2021. “When the Demand for Educational Research Meet Practice – A Swedish Example.” Research in Educational Administration & Leadership 6 (2): 348–376. doi:10.30828/real/2021.2.1