ABSTRACT

Informal academic conversations constitute a valuable addition to the repertoire of academic development initiatives. This article proposes that a Change Laboratory methodology may enhance the productivity of such conversations. Support for this proposal comes from a detailed analysis of participants’ transformation of conversations on individual problems, into collective and systemic understandings as well as potential solutions in the Change Laboratory. This is achieved through their use of theoretically derived tools from activity theory. Such transformative ability, as well as some participants’ application of the approach in their own research, it is suggested, may indicate the development of transformative agency.

Introduction

This article is inspired by Roxå and Mårtensson’s (Citation2017) call to harness academic conversations about problems in working life in order to create possibilities for transformative action. Although our study is similar to Roxå and Mårtensson’s (Citation2009) research in that it too foregrounds the contradictions with which academics’ work is rife, as well as the idea that within a socio-cultural framework significant conversations have impact, our approach is somewhat different from theirs. We examine an AD initiative that used an innovative methodology, the activity theory-inspired Change Laboratory (CL). A CL is a methodology that generates knowledge by inviting staff to a sequence of workshops (seven in this research), in which they work collaboratively on structured tasks to analyze and reimagine their own practices (Sannino & Engeström, Citation2017). A key tool of the CL is the reframing of experience through an activity theory lens, in which collective dialogue forms a key component, such that new possibilities for action may emerge.

CLs have been used in AD initiatives, though not extensively so. For example, Englund (Citation2018) used the methodology to assist academics in integrating pharmacy modules, and Fang (Citation2016) used it to understand limited service-learning uptake in a research-intensive university. As Bligh and Flood (Citation2015) suggest, CLs may be useful in assisting academics in working with changing circumstances, which may typify academic work.

Academics, in common with some other professionals, increasingly face multiple challenges. These include a globalized academic market, evolving knowledge cultures in the face of globalization and technological change, ever-increasing accountability, regulation frameworks, and public service funding cuts (Clegg, Citation2008; Zukas & Malcolm, Citation2019).

In terms of AD in times of change, Gibbs (Citation2013)identified a trend from individual to larger work group development, and from generic approaches to those more associated with specific disciplines. These trends connect with Trowler and Cooper’s (Citation2002) seminal earlier work, which suggested that development initiatives would need to work with particular disciplinary teaching and learning assumptions and practices if they are to have a positive effect. In addition, Boud and Brew (Citation2013), writing from a practice theory perspective, argued that educational development is best situated within the day-to-day practices of academic departments. Leibowitz et al. (Citation2015) described such collaborative work between academic developers and academics as ‘professional learning’. Here, learning carries with it the sense that academics need to gain a systematic understanding of their own practices within the full ambit of the academic organization in which they operate. Academic staff involved in AD in this way would be more likely to develop agency to confront and work with difficulties related to change, and so promote a more sustainable form of development (Englund & Price, Citation2018).

In response to these trends, Roxå and Mårtensson (Citation2017) suggest academics should talk to one another about their day-to-day work experiences of teaching students, and how this may relate to the constraints and affordances of the university. In this way, there can be a ‘counter-discourse’ to more formal ‘one-size-fits-all’ AD courses and events, which often focus on the attainment of predetermined outcomes, typically prescribed from above. The role of academic developers here is to provide structured and theoretically informed spaces so staff can gain knowledge about what needs to change, and perhaps also how to implement change (Roxå & Mårtensson, Citation2017).

As McCormack and Kennelly (Citation2011), Thomson (Citation2015), and Thomson and Trigwell (Citation2018) observe, relevance to staff’s concerns is a key characteristic of academic conversations, enhancing their potential for productive outcomes. Conversations can thus be described as being within the ambit of informal learning, arising in response to academic’s needs (McLean & McManus, Citation2009). Conversations can also be a means of harnessing practice-based expertise in negotiating and balancing out the complexities of contemporary academic life, and so can help to build academic communities (McGrath, Citation2020).

In addition to relevance and being self-generated by participants, according to Haigh (Citation2005) academic conversations should ideally be characterized as being collaborative, open, and non-threatening fora for sharing ideas. Dorner and Belic (Citation2021), writing in the recently published IJAD special edition ‘Conversations on learning and teaching’, propose that academics’ participation in reflective conversations can provide a pathway for both individual and collective development, in which new possibilities for action may emerge. As Thomson (Citation2015) and Thomson and Trigwell (Citation2018) describe in their analysis of informal teaching talk, these emerging possibilities may lead to new ideas about how to transform existing practices. There are thus ‘outcomes’ emanating from conversations, but these are not pre-determined (Haigh, Citation2005). Furthermore, Bligh and Flood (Citation2015, p. 8) describes how transformative thinking is often preceded by ‘venting’ of difficulties, which provides a platform for academics to connect with one another, and so an important ‘trigger’ for further learning (McCormack & Kennelly, Citation2011, p. 518). Through engaging in this sort of learning, academics may gain a sense of collective ‘self-efficacy’ to promote change from the ‘bottom-up’ (Dorner & Belic, Citation2021, p. 220). McCormack and Kennelly (Citation2011) highlight the usefulness of some form of loose structuring, for example, guiding questions, to improve the development and flow of conversations.

Informal, reflective academic conversations, as described by the above authors, show great potential as AD tools. In this article we argue that a CL methodology can assist academics in transforming difficulties raised in conversations into more systemic understandings and possible solutions to problems, thus enhancing the development potential of such conversations.

Context for the research

The context in which the research was conducted was a recently emerged University of Technology (UoT). At the time, a major disjuncture was becoming apparent within the UoT sector in South Africa. The UoT were created from prior, occupationally-focused technical institutions (‘Technikons’) in 2004. These institutions had a very clear purpose, that of serving industry (Powell & McKenna, Citation2009), but the purpose and distinctiveness of the UoT were and remain less clear. This lack of clarity was summed up by the Chair of the UoT network, when he made the observation that the sector seemed to be suffering from ‘mission drift’ as there was lack of clarity as to the sector’s purpose (Van Staden, Citation2016). Previous research interviews with our academic staff had highlighted this difficulty and their sense of confusion as they struggled to reconcile the competing mandates of education for work on the one hand, and the pressure to gain academic legitimacy on the other (Coleman, Citation2016). Furthermore, as an academic developer, the first author has frequently encountered staff’s need for a more defined purpose for the emerging UoT. The point being raised here is that conversations about the role and function of the UoT exist both nationally and locally, but have not thus far been substantively addressed. In response, the first author of this paper (an AD researcher) developed a project proposal with our National Research Foundation to explore the issue of UoT identity, entitled ‘Re-imagining UoT’. The CL problem-solving approach, as it typically deals with complex, often seemingly intractable problems (Virkkunen & Newnham, Citation2013), appeared to be an ideal methodology for this exploration.

To this end, the first author put out a call within the university for academic staff who had experienced difficulty in negotiating the new identity of becoming a UoT and might be interested in joining the ‘re-imagining’ project. Seven academic staff members drawn from the fields of Design (1), Education (2), Health (1), Hospitality (1) and Academic Development (2) volunteered for the project. Most of the staff on the project had, in one way or another, influence on the practice of AD within their faculties. Thereafter, the first author organized a week long training seminar with this group of volunteers in late 2018, which was delivered by Prof. Virkkunen (University of Helsinki) and focused on carrying out and researching a CL. The expectation was that these staff members would be equipped to conduct CLs that would broadly address issues of ‘reimagining the UoT’ within their own Faculties. However, the participants/volunteers felt unable to do this without further support from the first author, who had more experience in the methodology. To this end, we collectively decided to embark on an expansive learning cycle towards resolving current difficulties within our UoT, which was conducted in 2019.

Methodology

The CL begins with the facilitator presenting different perspectives on the problem of UoT identity by means of video and other documentary material. This acts as a stimulus for open-ended discussion of problems, which are then analysed by means of activity system diagrams as contradictory ‘pushes’ and ‘pulls’. Thereafter, participants are supported in developing new ideas, which can potentially resolve the identified contradictions.

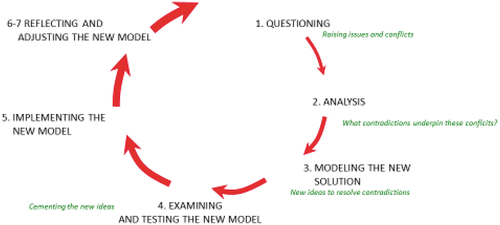

The CL is a collective learning initiative underpinned by the theory of expansive learning (Virkkunen & Newnham, Citation2013). It broadly follows the expansive learning cycle () with its series of learning actions of questioning, analysing, modelling, examining the model, implementing the model, reflecting on the process, and consolidating the new practice.

Figure 1. Expansive learning cycle of actions within a typical CL (after Engeström, Citation2001, p. 152).

As Virkkunen and Newnham (Citation2013) describe, unlike in other problem solving processes, much time and attention are spent on raising and discussing problems with which participants are confronted. This first stimulus is subsequently worked on through provision of secondary stimuli, which assist the participants in moving from heartfelt emotions to more theoretical understandings and reasoning. In this research, the secondary stimuli utilized were activity system diagrams or grids of the present and the past (Virkkunen & Newnham, Citation2013) and zones of proximal development (ZPD) diagrams. In activity theory, the ZPD represents the developmental space between a current problematic situation and a possible, improved future vision. It is typically represented as a four field diagram (), in which the main difficulties emerging in discussion are represented on the X and Y axes and the desirable vision in the top right quadrant (Sannino & Engeström, Citation2017).

Figure 2. Four field/ZPD representing the critical conflicts emerging through dialogue in sessions 1 and 2.

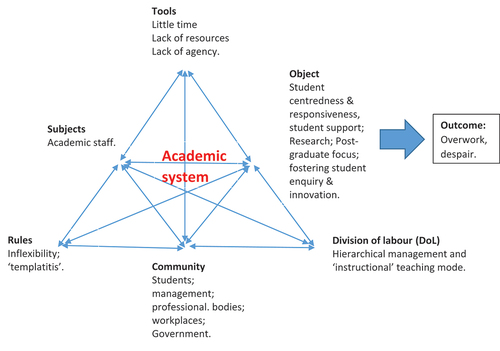

The activity system diagrams (, ) are built successively in the workshops and involve the analysis of difficulties and conflicts both in the present and as they have emerged in the past. The activity system is composed of mutually dependent elements. Briefly, the elements refer to what participants understand they are working on making happen within the university (the object or raw material); what they are using to do this work (tools); who else is involved with working on the object (community); and how the work of the participants (the subjects) is governed by the rules/culture they operate in, how the roles are divided up, and who holds the most authority (division of labour or DoL).

The main function of the activity analysis is to enable participants’ transition from narrative, discursive manifestations of difficulties, to understanding them as systemic contradictions within and between the above elements. Furthermore, through examining what changes have occurred in the different elements of the activity system over time, the nature and origins of the contradictions can be explored in greater depth (Engeström & Sannino, Citation2011). Through gaining such detailed and systematic knowledge, participants are assisted in constructing new, improved activity systems that can potentially overcome these contradictions (Sannino & Engeström, Citation2017).

However, actually generating new systems and ideas as potential solutions to identified problems is only one of the potential outcomes of a CL; this work can also develop participants’ transformative agency. Transformative agency is characterised by participants being able to transform an initial, individually experienced, problematic situation into something that can be collectively worked on through utilizing external tools (Virkkunen & Newnham, Citation2013). Furthermore, such agency manifests itself through participants’ ability to envision new possibilities and plan (and take) actions to change their current situations (Kerosuo et al., Citation2015).

As Bligh and Flood (Citation2015) outline, the nature of the CL itself is somewhat contradictory in that it is both open-ended and structured. It is open-ended in the sense that participants raise their own issues, albeit after directed stimulation from the facilitator. In addition, there is no pre-determined outcome; what emerges depends on how the participants choose to construct new ideas. At the same time, the process follows a number of pre-determined, theoretically informed methodological steps (), although these may be followed in any order. From February to July 2019, with an additional consolidation workshop in October, the first author facilitated seven consecutive 2.5 hour CL workshops under the theme of ‘reimagining a university of technology’ with the above group of academic staff. The results are reported here with reference to the learning actions of the expansive learning cycle in . The workshop setting was a small meeting room, with extensive wall space to record conflicts and ideas as they developed, as well as present analytical tools (activity systems, four field/ZPDs and historical change grids) from the workshops. The records provided continuity between workshops, which was further aided by the facilitator showing videoclips of key movements as these had emerged during conversations in each workshop.

Transforming problems into new possibilities in the CL

What actually transpired in the CL is described against the learning actions in in relation to: 1) questioning and raising of conflicts 2); analysis using ZPD/four fields and activity systems and identifying underpinning systemic contradictions; 3) resolving contradictions to develop a new model for the system; and 4) examining and testing the new model.

Learning action 1: questioning and criticising; expressing difficulties about current working conditions

The difficulties emerged mostly within the first two workshops and fall under the first learning action in , that of questioning/criticising. In subsequent workshops, these difficulties were progressively theorised, leading towards future, improved possibilities.

During workshop seven (preparation for presentation), the group examined the discourse from earlier workshops and identified what they thought were the most significant troubling issues: compliance, including the observation of ‘templatitis’ (this referred to a fixation on following rigid templates) versus innovation; and confusion of purpose and hierarchical decision making.

Compliance and ‘templatitis’

Here participant 3 initiated a discussion, supported by other group members, on how she was trying to source research funds but was confronted by seemingly insurmountable rules and difficulties in doing so:

If only we could predict consequences of actions, it is like a blind spot. It is compliance, I must follow the rules (participant 3).

It is like having a ‘cop in the head’! (participant 4).

It could just be stupidity … (participant 2).

As long as you are stuck on compliance, ‘that’s the rule’, how are you supposed to innovate? We even approach technology in a stuck way. We are trying to be at the forefront of technology education and innovation but we are given an amorphous object and we are trying to figure things out within this framework, that is so rigid. We need a more flexible framework because our identity is supposed to be about technology, innovation and change (participant 3).

Staff are always seeking a template, the first question (with any new task) is ‘can I have a template?’ People are template hunting, what is it, it is ‘templatitis’ (participant 4).

Hierarchies and confusion of purpose

The context is a discussion of the introduction of new more university-equivalent qualifications to replace the old diplomas, which were more occupationally focussed and understood by workplaces. Participants began to question the direction being taken by the university, and where these sorts of decisions were coming from.

We don’t look at the consequences (of introducing new qualifications). The target market is confused; we have confused everybody (participant 3).

So what are we? Are we a university? Where are we headed to? (participant 2).

Who made these decisions about qualification changes? Were you involved? (participant 5).

No! (participant 1, all).

There was some discussion but there was mainly a hierarchical decision from inside the university, ‘this is the route’ … people just make decisions, it is just happening to us (participant 4).

Actually the issue of ‘transformation’ to new qualifications became a key phrase and we just had to accept and not question it (participant 6).

Learning action 2a: analysis into ‘critical conflicts’

The four field/ZPD () was a thinking tool that emerged from participants’ expressions of difficulties. Participants highlighted the discrepancy between the current rigid culture of the university and the need for a future university, which should be more flexible in approach if it was to support innovation. Flexibility was also necessary to help deal with the changing and multiple focuses of the university. These then constituted the ends of a continuum, which the participants collaboratively constructed. A second continuum identified was between the current and historical hierarchical forms of management, and a wished-for, more collaborative way of operating. Activity theory follows a relational stance such that tensions are not seen as separate emergences, but as an integrated part of the system as a whole (Sannino & Engeström, Citation2017). The two continua can thus be represented as X and Y axes on the four field/ZPD. Looked at in this way, lecturers were able to use the four field/ZPD to identify from where the university had emerged, and where, perhaps, they would like to see it in the future. This envisaged future was some form of working which was both collaborative and flexible. This future projection was crystallised in later sessions as a new model for collaborative work, ‘knotworking’ (Engeström, Citation2008).

Learning action 2b: analysis – building the current activity system and highlighting contradictions

In this learning action, participants are presented with the blank activity system diagram () and asked by the facilitator to collectively perform a systems analysis of their academic work at the university. What, for example, do the participants understand to be the object of the UoT (what they think is its main function or purpose)? What tools and resources are available (or not available) to academics to work on this object? Under what sorts of conditions (rules and divisions of labour) does this work occur?

In an activity theory analysis, the system is always object-oriented and the object provides impetus and motivation for lecturers’ work. However, participants raised the problem of the multiplicity of objects lecturers were expected to work towards. There was, firstly, the call from management to develop students who were more than just ‘industry automatons’ but who could problem solve, enquire, be innovative and had a more holistic understanding of society. But, at the same time, lecturers had to deal with students who struggled with university-level learning. Lecturers were also expected to produce innovative research in their field. Where the object is multiple or less clear, as was the case here – what Sannino and Engeström (Citation2017, p. 86) refer to as a ‘vanishing object’ – it may lead to academics experiencing an undesirable outcome of overwork and even despair.

Working with the vanishing object could be partly ameliorated, participants suggested, if academics were to be provided with adequate tools, for example, targeted staff development and time to reflect on the multiple issues with which they were confronted. Furthermore, the divisions of labour in the university may be partly responsible for the multiple objects with which lecturers have to engage – decisions about the purpose and direction of the university are often taken by management without sufficient consultation and feedback from staff on the ground. The participants felt that they lacked ‘agency’ within the university. Furthermore, the teaching culture of the university is described by the participants as one of ‘instruction’ rather than student engagement in problem solving, which would be the more appropriate approach to develop students’ innovative and enquiring capacities. In mapping the system in this way, the original conflicts can now be seen as systemic tensions or contradictions within and between the different elements. These contradictions are relational, aggravating one another, exacerbating difficulties with working on the object.

How, for example, are lecturers expected to work on ideas of ‘enquiry’, ‘innovation’ and responsiveness, or even to develop and conduct their own research under conditions of inflexible rules/policies and form-filling?

Participants also examined the university activity system at different historical junctures. The aim was to identify, through collective reflection, what has changed a lot and what has changed less over time, so indicating the origins of current problems in working life (Virkkunen & Newnham, Citation2013).

What was also becoming clear in the discussions was that the object of the university activity system had changed over time. What was previously a relatively singular object, a ‘work-ready’ student, had now become much more complicated in including multiple and often competing objects (for example, conducting research, fostering enquiry and innovation, and being student centered).

Learning action 3: modelling a new concept

In session 6 the facilitator suggested that the participants revisit the tensions and underlying contradictions identified in order to seek possible resolutions. In response, the participants highlighted the historically-rooted hierarchical system of the university as a major stumbling block to creating and implementing new visions for the emerging UoT:

We currently have departments, faculties, Mancom (the central university management committee of DVCS, senior directors and deans), university council, committees etc., so it is very top down and hierarchical. You look at these levels and ask how you collaborate within these? The university is in an old mould here. Management wants all of these new changes to our work but how are they changing? (participant 4).

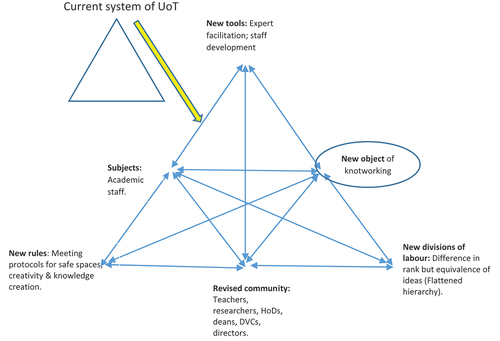

The participants began to develop a working model for addressing hierarchical issues which resembled an egg with a number of concentric circles, each depicting the different hierarchical levels within the university. Cutting across these concentric circles, the participants identified the need for some form of horizontal meeting space in which ‘staff are different in rank but equivalent in the ideas they bring forward’ (participant 2). At this point the facilitator suggested a concept drawn from Engeström’s (Citation2008) work, that of knotworking. The knot is a form of temporary, mixed specialization, issue-based and purpose-driven forum in which hierarchies are flattened and the possibility of new ways of dealing with issues may emerge. The knot may also offer a partial resolution to the conflicts first raised in section 2b on the ZPD/four field diagram (). Furthermore, participants began to think that forming a knot might constitute a significant move towards a new identity for the university, that of working with uncertainty and difficulty and with an ill-defined object.

Learning action 4: examining the knotworking model

In this learning action, the participants then began to think forward as to what sorts of affordances would need to be in place to enable and support the concept of knotworking, and to construct an imaginary activity system of the future (). Participants highlighted the need for more supportive meeting protocols (rules) and a flattening of rank and equivalence of ideas put forward (division of labour or DoL) to support work on the object of knotworking. In addition, staff would need to be capacitated with these new ways of working, and the way facilitation is conducted revisited.

In typical CL work, participants would take the new ideas and develop them further in proposing how they may be implemented (for example, drawing on exemplars of knotworking from other universities), followed by actual experimentation (actions 5–7 in ). As Virkkunen and Newnham (Citation2013) point out, the process does not often get this far, as it usually requires further expansive cycles. Nonetheless, CL work also involves participants in transforming problems into more systemic understandings which may result in novel solutions, thus developing their ‘transformative agency’ (Kerosuo et al., Citation2015). Though this developing agency is illustrated in the above description of the CL process itself, it was also evident in participants’ reflections on their experiences, and their ability to transfer their learnings to new settings.

Reflections on the CL and further developments

The Design participant had perhaps the most succinct description of using tools to transform the problematic situation of the current UoT, and developing aspects of ‘transformative agency’:

As an experienced facilitator I was excited by the marriage of a pragmatic response to change coupled with depth of research in the change lab. The flexible and contextual structure of the activity triangle, when mapped across the dimensions of past, present and future, gives what amounts to a three-dimensional view of complex and focused changes over time. The articulation of problems and identification of themes follows a bottom-up path, from the individual to the emergence of what is shared, from the abstract to the concrete with an expressed utilisation of the psychodynamic aspects of group work, viz the double bind and use of provocations. This engagement with emotion seems to contribute energy to develop new solutions.

In addition, she was facing a sense of despair within her department as they struggled to deal with both changing workplaces and changing student profiles. Over the course of a 6-session CL in late 2019 she and one other of the original participants facilitated the development of a new activity system with her departmental staff, which involved the new object of the ‘heterogeneous student’ and new rules and tools to support this object.

The Health participant believed that benefits accrued from seeing problems differently in the CL, and in recognizing new possibilities for action:

The CL is a good space, a developmental space. I feel we are taking ownership of our important knowledge of a UoT. At this stage all I can say it that it has definitely inspired a new way of thinking about problems and provided a different lens for forming new knowledge and innovative practices in problematic times in Higher Education. Our CL theory and group discussions of Knotworking provided a perspective from which I could recognize Knotworking in action and could understand ethnographically what was happening. (It) has provided me with a lens with which to view knowledge production.

For the Hospitality participant new understandings developed through collective work on university difficulties:

The CL was an eye opener for me. You get to be pushed and engage within the group. You get ideas from other members of the group and something emerges. The UoT difficulties were explored in the workshops and being part of the group to find solutions to the problem was a great experience. The CL work we did helped me grow academically … it gave me an opportunity to utilise the CL knowledge and to share the benefits of the method with my colleagues.

In terms of ‘sharing’, she was able to use the CL methodology to investigate problems in students’ transitions to employment in her department. She conducted a problem-solving CL with recent graduates in late 2019/early 2020, with the assistance of another original CL participant. Using activity system diagrams of the present and past the graduates were able to highlight that recent increasing enrolments were not matched with commensurate practical training resources. The situation was further aggravated by a weakening in employer-university communications and many new students’ understandings of the field.

In Education, the focus was more on using findings from the CL to explore her own research interests:

The CL process supported individual faculty to develop our own projects. My research journey is an attempt to develop personal agency and competence to explore the implementation of change labs as a means to answering my own research questions.

For this participant, the important question to be addressed was that of effectively preparing students as language teachers, in response to difficulties raised by the Faculty. To this end, she has explored ‘preparation’ through utilising the first learning action of questioning and by raising conflicts with stakeholder participants in workshops. Furthermore, she has begun assisting her CL participants in analysing conflicts through using activity system diagrams.

Discussion

The nature of informal, academic conversations has something in common with the CL methodology; there is also a focus on open discussion of locally relevant issues, and a broadly transformative agenda. As the participants report in their reflections, the CL is ‘bottom up’ in that it deals with what staff identify as important and involves moving from individual to collective understandings for change. In addition, the methodology may contribute to making such informal and reflective conversations in AD initiatives even more productive, as described below.

As Haigh (Citation2005, p. 14) notes, issues raised in academic conversations ‘may not linger if there is no record that can be revisited’. A significant benefit of using the expansive cycle in the CL is that it renders learning and change raised in conversations visible to the participants (Kerosuo et al., Citation2015), both immediately and over time. This is accomplished, firstly, through spending much time highlighting and recording (through newsprint and video) conflicts and difficulties, or ‘whingeing’ (Thomson, Citation2015). Thereafter, these difficulties are represented systemically on activity system diagrams so that they can be seen and understood, not just as isolated occurrences, but rather as linked to one another. The systemic representations also provide reflective panes of how things were in the past, how they are now, and what they could possibly be in the future. Secondly, CL participants are provided with conceptual tools – activity systems, history grids and four fields/ZPDs. In using these tools, CL participants are assisted in manifestly linking difficulties raised in conversations to more deep-seated and significant contradictions in working life. Through surfacing these contradictions, new possibilities to resolve the original difficulties may emerge (Sannino & Engeström, Citation2017), which may not have been immediately apparent in the earlier conversations. Furthermore, CL participants may be enabled to transfer the methodology to problematic issues within their own Faculties, a benefit which does not necessarily accrue in relatively unstructured and less visible academic conversations.

However, an incentivising aspect of academic conversations is the control staff have over when they meet, over what time period, and in what manner (Thomson & Trigwell, Citation2018). In conducting CLs, academic developers should be sensitive to allowing as much participant autonomy as possible, without losing the advantages conferred through a more structured and visible process. Further to the structure, CL work involves participants in learning a new theory and language of analysis. In this research, for example, participants were inducted into the methodology through a week-long workshop. Bligh and Flood (Citation2015) comment that some participants may experience this as a daunting task and so resist it, a caveat that researchers should note.

Conclusions

Roxå and Mårtensson (Citation2017, p. 103) highlight the importance of engaging academics in conversations about their daily lives within universities. The role of academic developers is then to scaffold these conversations so that recipient staff may become ‘informed, critical and ultimately transformative’. Through so doing academic staff are able to address seemingly insurmountable problems, and seek through their collective wisdom possibilities for future resolutionary actions. Within the CL reported on here, academics are able to exercise agency in transforming issues and conflicts raised in their initial conversations into more systematic understandings. They are, furthermore, able to transfer these new forms of action towards resolving conflicts in other aspects of the changing university, thus providing further evidence for their developing transformative ability.

Thomson and Barrie (Citation2021), in the recent IJAD special edition on academic conversations, suggest that informal conversations’ productivity may be enhanced when complemented by more formal learning. As a semi-formal yet flexible approach, the CL methodology may help to fulfil this role. We therefore believe that the CL, through stimulating and structuring dialogue about everyday issues, can potentially enhance informal, reflective academic conversations and so contribute productively to AD initiatives.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of National Research Foundation Grant HSD 111835

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

James Garraway

James Garraway is an adjunct professor in the Professional Education Research Unit at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology (CPUT), with a particular interest in activity theory, organizational change and the relationship between university, work, and society.

Xena Cupido

Xena Cupido is director of the Fundani Centre for Higher Education at CPUT. Her research interests include working with students as partners for retention and success, and gender equality for social justice in higher education. She is co-convenor in the Tutor, Mentor and Supplemental Instruction Special Interest Group of the Higher Education Learning and Teaching Association.

Hanlie Dippenaar

Hanlie Dippenaar is a senior lecturer in the Department of English, Faculty of Education, CPUT, Wellington. Her research interests combine community engagement, service learning, and language teaching. She currently explores collaboration between university partners, using activity theory and CLs.

Vuyokazi Mntuyedwa

Vuyokazi Mntuyedwa is an academic literacy lecturer at CPUT. Her interests are in academic literacy and language teaching, and she assists students through running workshops in academic writing.

Ngizimisele Ndlovu

Ngizimisele Ndlovu is a lecturer in Hospitality at the Cape Town Hotel School at CPUT. Her interests are food and beverage management training and research.

Anthea Pinto

Anthea Pinto is teaching and learning coordinator in the Faculty of Health and Wellness Sciences at CPUT. She has a special interest in higher education studies, curriculum development, and policy. She is also a board member of the professional board for optometry and dispensing opticians of the Health Professions Council of South Africa.

Janet Purcell van Graan

Janet Purcell van Graan is a senior lecturer in applied design at CPUT, with a special interest in personal and professional literacies. She also provides executive coaching to academic and corporate leaders.

References

- Bligh, B., & Flood, M. (2015). The Change Laboratory in higher education: Research-intervention using activity theory. In J. Huisman & M. Tight (Eds.), Theory and method in higher education research volume 1 (pp. 141–168). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Boud, D., & Brew, A. (2013). Reconceptualising academic work as professional practice: Implications for academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 18(3), 208–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2012.671771

- Clegg, S. (2008). Academic identities under threat? British Educational Research Journal, 34(3), 329–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920701532269

- Coleman, L. (2016). Asserting academic legitimacy: The influence of the University of Technology sectoral agendas on curriculum decision-making. Teaching in Higher Education, 21(4), 381–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2016.1155548

- Dorner, H., & Belic, J. (2021). From an individual to an institution: Observations about the evolutionary nature of conversations. International Journal for Academic Development, 26(3), 210–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2021.1947295

- Engeström, Y., & Sannino, A. (2011). Discursive manifestations of contradictions in organizational change efforts A methodological framework. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 24(3), 368–387. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534811111132758

- Engeström, Y. (2001). Expansive learning at work: Toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. Journal of Education and Work, 14(1), 133–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080020028747

- Engeström, Y. (2008). From Teams to knots: Activity theoretical studies of collaboration and learning at work. Cambridge University Press.

- Englund, C., & Price, L. (2018). Facilitating agency: The Change Laboratory as an intervention for collaborative sustainable development in higher education. International Journal for Academic Development, 23(3), 192–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2018.1478837

- Englund, C. (2018). Exploring interdisciplinary academic development: The Change Laboratory as an approach to team-based practice. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(4), 698. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1441809

- Fang, Y. (2016). Engaging and empowering academic staff to promote service-learning curriculum in research-intensive universities. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 20(3), 57–78.

- Gibbs, G. (2013). Reflections on the changing nature of educational development, International Journal for Academic Development, 18(1), 4–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2013.751691

- Haigh, N. (2005). Everyday conversation as a context for professional learning and development. International Journal for Academic Development, 10(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13601440500099969

- Kerosuo, H., Mäki, T., & Korpela, J. (2015). Knotworking and visibilization of learning in inter-organizational collaboration of designers in building design. Journal of Workplace Learning, 27(2), 128–141. https://doi.org/10.1108/JWL-10-2013-0092

- Leibowitz, B., Bozalek, V., Van Schalkwyk, S., & Winberg, C. (2015). Institutional context matters: The professional development of academics as teachers in South African higher education. Higher Education, 69(3), 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9777-2

- McCormack, C., & Kennelly, R. (2011). ‘We must get together and really talk … ’. Connection, engagement and safety sustain learning and teaching conversation communities. Reflective Practice, 12(4), 515–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2011.590342

- McGrath, C. (2020). Academic developers as brokers of change: Insights from a research project on change practice and agency. International Journal for Academic Development, 25(2), 94–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2019.1665524

- McLean, J., & McManus, J. (2009). Using workplace learning as a lens to reframe academic development. Paper presented at the 6th International Researching Work and Learning Conference in Roskilde University, June 28 to July 1.

- Powell, P., & McKenna, S. (2009). ‘Only a name change’: The move from Technikon to University of Technology. The Journal of Independent Teaching and Learning, 4, 37–48.

- Roxå, T., & Mårtensson, K. (2009). Significant conversations and significant networks – Exploring the backstage of the teaching arena. Studies in Continuing Education, 34(5), 547–559. doi:10.1080/03075070802597200.

- Roxå, T., & Mårtensson, K. (2017). Agency and structure in academic development practices: Are we liberating academic teachers or are we part of a machinery supressing them? International Journal for Academic Development, 22(2), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2016.1218883

- Sannino, A., & Engeström, Y. (2017). Co-generation of societally impactful knowledge in CLs. Management Learning, 48(1), 80–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507616671285

- Thomson, K., & Barrie, S. (2021). Conversations as a source of professional learning: Exploring the dynamics of camaraderie and common ground amongst university teachers. International Journal for Academic Development, 26(3), 320–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2021.1944160

- Thomson, K., & Trigwell, K. (2018). The role of informal conversations in developing university teaching. Studies in Higher Education, 43(9), 1536–1547. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1265498

- Thomson, K. (2015). Informal conversations about teaching and their relationship to a formal development program: Learning opportunities for novice and midcareer academics. International Journal for Academic Development, 20(2), 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2015.1028066

- Trowler, P., & Cooper, A. (2002). Teaching and learning regimes: Implicit theories and recurrent practices in the enhancement of teaching and learning through educational development programmes. Higher Education Research & Development, 21(3), 221–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436022000020742

- Van Staden, L. (2016). Re-branding ‘second class’ Universities of Technology. University World News, reporter Sharon Dell. https://www.universityworldnews.com/sp-report.php?id=64

- Virkkunen, J., & Newnham, D. S. (2013). The Change Laboratory: A tool for collaborative development of work and education. Sense Publishers.

- Zukas, M., & Malcolm, J. (2019). Reassembling academic work: A sociomaterial investigation of academic learning. Studies in Continuing Education, 41(3), 259. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2018.1482861