ABSTRACT

In its COVID-19 Statement of April 2020, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child recommended that States Parties explore alternative and creative solutions for children to enjoy their rights to rest, leisure, recreation, and cultural and artistic activities – rights, which along with the right to play, are encompassed in Article 31 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). This paper reflects on play in times of crisis, giving particular focus to the experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Three narratives of play and crisis are introduced – play in crisis; the threat to play in times of crisis; and play as a remedy to crisis. Progressive responses to support play during COVID-19 are appraised. Against a backdrop of innovation and a stimulus to research in play, concerns persist that children’s right to play is not foregrounded, and that the ‘everydayness of play’ is not adequately facilitated.

Introduction: three narratives of crisis and play

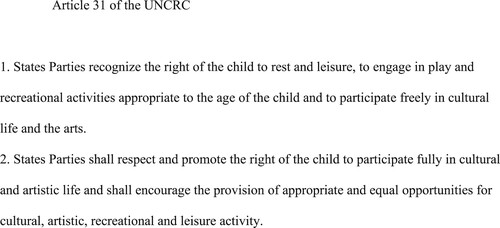

The right to rest, recreation, play and cultural activities – asserted within Article 31 in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) – is more than just the articulation of another children’s right (). To paraphrase the title of Robin Moore’s seminal text, the articulation of this right is uniquely important as play is widely considered to be childhood’s domain.Footnote1 Lothar Krappmann would agree: when writing as a member of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, he asserted that, ‘it is the bundle of rights under article 31, which very much determines whether children can recognise themselves as active subjects’.Footnote2 Play is of fundamental importance to the child, children and childhood.

The distinct nature of play within the context of Article 31 of the UNCRC (which addresses rest, leisure, play, cultural life and the arts) is set out within the legal analysis provided by the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child in General Comment No. 17Footnote3, in which it is explained that play is,

… any behaviour, activity or process initiated, controlled and structured by children themselves; it takes place whenever and wherever opportunities arise. Caregivers may contribute to the creation of environments in which play takes place, but play itself is non-compulsory, driven by intrinsic motivation and undertaken for its own sake, rather than as a means to an end. Play involves the exercise of autonomy, physical, mental or emotional activity, and has the potential to take infinite forms, either in groups or alone. These forms will change and be adapted throughout the course of childhood. The key characteristics of play are fun, uncertainty, challenge, flexibility and non-productivity. Together, these factors contribute to the enjoyment it produces and the consequent incentive to continue to play. While play is often considered non-essential, the Committee reaffirms that it is a fundamental and vital dimension of the pleasure of childhood, as well as an essential component of physical, social, cognitive, emotional and spiritual development.

Play also tends only to be associated with good times, fun and positivity. Although it is not our intention to traduce play or add to the complexity surrounding its understanding, we contend that play should also be considered in relation to crisis. More precisely, we describe three narratives of crisis and play. First, our understanding of everyday play is increasingly troubled (play itself is viewed as being in crisis). Second, play is threatened in times of crisis. These crises for play render it more difficult to realise this fundamental right. In contrast, we also find evidence of a third positioning: play as remedy to crisis, which can be evidenced during the recent COVID-19 crisis (as well as other contemporary crises). Although central to our argument, our treatment of the crises for play is less extensive than our analysis of play as a remedy to crisis, which is the primary focus of this paper. We appraise the tools that promote a rights-based case for play, before concluding on children’s play, rights, and crisis.

Our departure for engagement is the independent Children’s Rights Impact Assessment (CRIA) in Scotland,Footnote13 which drew on emerging evidence, and was undertaken in Scotland in May and June 2020. Published by the Children and Young People’s Commissioner, Scotland and undertaken by the Observatory of Children’s Human Rights Scotland, the independent CRIA analysed the impact on the human rights of children and young people in Scotland of the emergency laws and policies passed during the COVID-19 pandemic. The independent CRIA is framed by the eleven recommendations made by the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child in their statement of 8 April 2020, which warned of the ‘grave physical, emotional and psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on children, particularly those in situations of vulnerability’. The second of these recommendations highlighted the need to ‘explore alternative and creative solutions for children to enjoy their rights to rest, leisure, recreation and cultural and artistic activities’.Footnote14

The issues we consider are of significance beyond Scotland and the immediate timeframe in which the CRIA took place, and we also draw on research and evidence from further afield. We consider the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on the integrity of play and appraise the potential of play-based interventions to mitigate harm in the present and longer-term. This offers an opportunity to reaffirm and strengthen the status of play as a fundamental and inalienable human right.

Recognition of children’s right to play

The path to recognition for the right to play was not straightforward. A right to rest and leisure but not play was laid down in Article 24 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) in 1948.Footnote15 The right to play first emerged in the Declaration of the Rights of the Child (DRC) in 1959,Footnote16 Article 7 of which states,

The child shall have full opportunity for play and recreation, which should be directed to the same purposes as education; society and the public authorities shall endeavour to promote the enjoyment of this right.

Children’s right to play as asserted in Article 31 of the UNCRCFootnote19 is now more than three decades old and should be widely understood and well established in practice. However, actions and policy were insufficient to realise children’s right to playFootnote20 with the International Play Association, remarking that Article 31 was, ‘one of the least known, least understood and least recognised rights of children, and therefore one of the most consistently ignored, disdained and violated rights in the world today’.Footnote21 FronczekFootnote22 referred to it as the ‘forgotten right’, a view re-affirmed by Doek,Footnote23 who served as the Chair of the Committee on the Rights of the Child from 2001 to 2007,

Despite this international consensus on the importance of the right to engage in play, the attention given to the implementation of these rights in the reports States Parties submitted to the CRC Committee is very limited and often completely lacking. The same often applies for the reports submitted by Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO’s) and UN agencies.

The objectives of General Comment No. 17 were to: (i) enhance understanding of the importance of Article 31; (ii) promote respect for the rights articulated under Article 31; and (iii) outline the obligations of agents (including governments) under the UNCRC. It was described by Brooker and WoodheadFootnote25 as perhaps ‘the most urgent contribution to this complex field’. Nevertheless, as we approach one decade further on, there is evidence that further advocacy and leadership is required to make progress on implementation. Janot and Rico’sFootnote26 analysis of reports submitted by European Union member countries to the UN Committee and the final recommendations (concluding observations) by the Committee to each State Party, found that only seven of the of 19 European Union States Parties to report in the study period even mentioned children’s right to play. Of the 23 States Parties receiving recommendations from the UN Committee, only six received recommendations related to the right to play.Footnote27

Thus, children’s right to play – while acknowledged – was not being sufficiently realised in practice. This is the context against which to set the restrictions imposed on play as part of the process to manage public health during the COVID-19 crisis.

Everyday play in crisis

Paradoxically, the strengthening of proclamations of children’s right to play has coincided with a growing sense of everyday play in crisis. In General Comment No. 17 concern was expressed over access to play for some groups of children, including girls, poor children, disabled children, indigenous children, and children belonging to minorities. Ordinary, everyday opportunities to play, in and around the spaces children inhabit daily, at home, on the street, in school and in the wider community, have been threatened, despite acknowledgement of their value,Footnote28 and despite interventions to try and recover time-spaces for play.Footnote29

In many ways, twentieth century progress has had unintended and adverse consequences for everyday play. In the UK for example, mid-late twentieth century area regeneration improved housing amenity, replacing overcrowded homes in densely populated neighbourhoods with better equipped and more spacious housing set in estates with public space and amenity. Although public spaces afforded potential to support play, through time more liveable domestic spaces have facilitated more private lives, inadvertently reducing play in the public realm.Footnote30 Higher levels of car ownership offer freedom and flexibility, but at the high cost of play affordance on urban streets.Footnote31 Societal expectations of childhood have also changed: previously understood as being a time before work, it now tends to be viewed as a time for intensive preparation and positioning for the world of work, with an increased focus on concerted cultivation and formal education.Footnote32 Time previously given over to incidental and everyday play becomes a resource to be used more gainfully. There has been a growing aversion to risk,Footnote33 with once familiar and celebrated forms of play being recast as dangers from which children must be protected.Footnote34 Technology- and equipment- rich play has provided further incentive to induce children’s withdrawal from public space into the domestic realm.Footnote35 There has also been a shift away from incidental play to play as an event, with children increasingly being accompanied by adults to ‘play dates’ or commercial centres which sell play experiences.Footnote36 The net result of these inter-related changes is growing concern among advocates of play over the lack of outdoor play,Footnote37 independent mobility of children to access play,Footnote38 active playFootnote39 and social interaction through play.Footnote40

Observations on other pre-pandemic developments signposted some of the challenges that could have been predicted at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Without statutory obligation, many local authorities in the UK disinvested from play when adjusting to the adverse financial settlement of Austerity that was initiated in 2010,Footnote41 decision-making that was fuelled by a lack of understanding of play and its value. More positively, there is growing recognition that play may be one solution to some of the problems that contemporary living presents in advanced economies, with the instrumental benefits of play promoted, for example, within education,Footnote42 physical health (to tackle obesity),Footnote43 mental health,Footnote44 and urban planning and design.Footnote45 In effect, these campaigns and initiatives seek to recover the ‘everydayness’ of play in children’s lives. However, from a children’s rights perspective, it is also important to look beyond the instrumental value of play: play matters simply because children enjoy it, a point made in General Comment No. 17 which acknowledges that as well as being an essential component of physical, social, cognitive, emotional and spiritual development for children, play is ‘a fundamental and vital dimension of the pleasure of childhood’.

Reflecting on play in crisis situations

In times of crisis – natural disasters, manufactured disasters, and complex emergencies – children’s right to play is threatened. The barriers to everyday play are exacerbated, and the enablers of play are jeopardised, as access to space, time and permission for play is impeded. However, children’s basic developmental, health and wellbeing needs do not disappear during crisis. The importance of enjoying childhood remains. Perhaps more than ever, children still need to move, use their imaginations, laugh, interact, and experience what Lester and Russell refer to as the ‘everyday magic’ of play.Footnote46

Arguably, the greatest global threat to play is in the challenges presented by the scale of forced displacement. Children are over-represented among the 82.4 million people who were forcibly displaced from home in 2020 (42% of whom are children, far in excess of their 30% share of the world’s population).Footnote47 The challenges that present in sustaining play in transit, and in temporary accommodation, are significant.Footnote48 Although the focus of this paper is on the challenges to play that present in the unique circumstances of the global COVID-19 pandemic, there is learning to be gleaned from previous work that has considered play in the midst of humanitarian crisis.

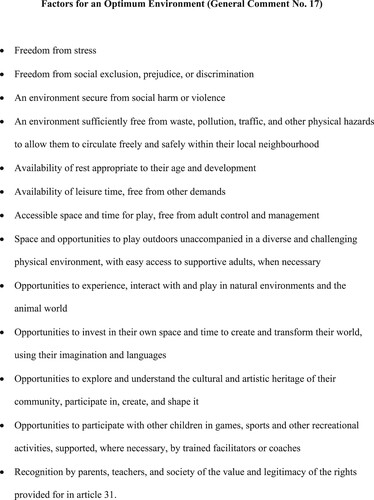

On one level, it might be argued that children need very little in the way of material resources to play, and as WardFootnote49 demonstrated in his seminal studies of play in the UK, children’s play can appear anywhere and everywhere. In theory, there may appear to be no reason why play cannot flourish amidst crises. However, Lester and RussellFootnote50 are among those who emphasise that the conditions which facilitate play extend beyond material resource. Although the potential exists to play in times of crisis, the necessary conditions are not always present to facilitate it. General Comment No. 17 specifies thirteen factors for an optimum environment (for the realisation of Article 31), providing both a reference point to assess prevailing conditions and a signposting to areas which should be considered to uphold children’s right to play in times of crisis, and beyond (). These could be reduced to a necessity for space (where they feel relaxed and safe enough to play), time (which is free of other demands), some resources (materials, things to play with) and permission (an atmosphere of at least tolerance for play or absence of severe restrictions). Rather than requiring a specific designated location, a play space is created through children’s shifting and dynamic interactions with each other and the materials and symbols present in any space; children’s performance of play both takes and makes place.Footnote51

ReviewsFootnote52 have drawn from exemplar case studiesFootnote53 to impart understandings of play amid crises. While crisis alters the conditions for play, it might be argued that crisis situations also create demand and heighten the importance of play. Cohen et al.Footnote54 have argued that playfulness can bolster resilience and provide a sense of normality for children in and after crisis situations, while Tonkin and Whitaker have argued that play and playfulness can mitigate the impact of COVID-19.Footnote55 Play is also spontaneous and adaptive to circumstance. Others have observedFootnote56 the emergence of what is known as posttraumatic play – that with a serious, driven, and morbid quality – through which children play to work out their understanding of adverse life experiences, including violence to which they have been exposed. Such play can be characterised by repetitive unresolved themes, increased aggressiveness and/or withdrawal, fantasies linked with rescue or revenge, reduced symbolisation, and concrete thinking.Footnote57 Engagement in playFootnote58 and psychosocial sports and play programmesFootnote59 indicate the benefits for social wellbeing and psychological health, and children’s ability to recover from adversity and enable them to come to terms with life experiences.Footnote60

Thus, although play is challenged by crisis, play persists, albeit taking forms that reflect the particularities of the life situations and life experiences that children have encountered.

Play in the COVID-19 crisis

In theory, the public health responses to the COVID-19 pandemic could have favoured play in the sense that more leisure time (defined as free or unobligated time that does not involve formal education, work, or home responsibilities) was available for some to relax, have fun and pursue hobbies. However, childhood is not experienced in the same way by all children. For young carersFootnote61 and many girls,Footnote62 the domestic realm is associated with family and caring responsibilities. Vulnerable childrenFootnote63 – those who lack oversight from caring adults – may rely more on dedicated times and spaces for play outside the home. And the specialist support and facilities for play that are provided by professionals working with disabled childrenFootnote64 and pre-school childrenFootnote65 may be a more significant loss than what is gained in opportunities within the home.

Public health responses to COVID-19 take different forms, each of which impacts on play (). First, there is quarantine, in which those with the virus physically isolate to recover and to protect others from infection. Given the dependent status of children, isolation may have resulted from the infection of their parents or carers, in addition to self-infection. Second, there is lockdown, in which public interaction is limited to essential exercise or granted only to those with ‘key worker’ status. As with quarantine, children may have been physically well, but prevented from outdoor play during this period. Third, there is the spectrum of conditions post-lockdown under which restrictions are eased, and public health protection measures remain in place. Finally, there is the total removal of restrictions and public health protective measures. Although this final example is ‘post-virus’, the legacy of COVID-19 times – expressed in a wariness of public interaction – might be expected to persist for the early part of this period.

Table 1. COVID-19 public health management: overview of impact on children’s play.

The lockdown which came into force in the UK in March 2020 brought about a significant and sudden change in conditions for children and young people to play, which may have been traumatic in themselves.Footnote66 It impinged on children’s right to play, curtailing those coping mechanisms that are derived through play and the removing the senses of autonomy and freedom that are associated with it. The public health imperative, while of paramount importance, does not preclude us from asking how measures to contain the spread of COVID-19 impacted on children’s ability to exercise their rights under Article 31, and to ask what could reasonably be done about that.

In its COVID-19 Statement of April 2020, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child drew attention to the fact that, ‘many children are gravely affected physically, emotionally and psychologically, especially in countries that have declared states of emergencies and mandatory lockdowns’.Footnote67 The statement explicitly recognised children and young people’s Article 31 rights, highlighted in their second recommendation, which called on States to explore alternative and creative solutions for children to enjoy their rights to rest, leisure, recreation and cultural and artistic activities.

The Scottish Government’s initial response to the UNFootnote68 relied heavily on digital and online solutions. Undoubtably, COVID-19 provided a stimulus to extend the range of online opportunities for play, created for and with children and young people. These developments benefitted many, will have strengthened the prospects for digital play after lockdown, and have contributed to the blurring of boundaries across digital and non-digital play.Footnote69 For some children, digital platforms enable their rights under Article 31 to be realised. At the same time, it must be acknowledged that digital play is not equally accessible to all, notably, children from low-income families, disabled children, children with additional support needs, and refugee and migrant children.Footnote70 It is also important to take a rounded perspective. Prior to the pre-COVID-19 pandemic, children and young people were encouraged to seek a healthy balance in daily screen time and were warned of the risks of spending too much time online and on screens;Footnote71 yet in the COVID-19 times, children and young people were positively encouraged to spend increasing amount of time online for educationFootnote72 as well as for play.

Evidence accumulated from civil society in Scotland that demonstrated adverse impact on play for children and young people. SurveysFootnote73 and research over the following months would demonstrate how this would particularly affect children living in poverty, in inadequate housing, and those with little access to physical space or to online communities. The impact on 10 to 17-year-olds in Scotland was summarised well by Public Health Scotland, which noted, ‘whether positive or negative, it is likely that these impacts will not be equally distributed and may widen existing inequalities’.Footnote74 Children and young people living in a home without adequate indoor space, a garden, access to outside space, or safe open space nearby would have found it particularly difficult to meet needs for physically activity play.

As the pandemic has progressed, the evidence base on play accumulated, albeit largely from advanced economies. A wide range of aspects of play have been considered including indoor play,Footnote75 digital play and hybrid online-offline play,Footnote76 access to outdoor play and impact of regulations on play,Footnote77 development of a child lockdown Index (comparison across nations of weeks of restricted access to play space),Footnote78 parents’ attitudes to play,Footnote79 experience of play in adventure playgrounds,Footnote80speculations on how particular play time-spaces might be central to recovery,Footnote81 and return to play after infection.Footnote82 Some positive experiences have been reported such as online play helped prepare young people to re-engage when restrictions were being eased,Footnote83 families were discovering new play opportunities,Footnote84 teachers in early education were imparting advice on play strategies to parents,Footnote85 streets were being used more extensively as a playspace,Footnote86 and the potential for streets to be used more intensively to promote child health,Footnote87 led to many reporting children had more imaginative play.Footnote88 However, more typically, research has identified pressures on play including less time spent outdoors,Footnote89 reduced opportunities for co-operative play,Footnote90 laments of the loss of play with friends or non-resident family members,Footnote91 reduction in attendees at adventure playgrounds,Footnote92 reduction in young people meeting physical activity guidelines,Footnote93 and heightened parental stress for those managing play with young children in the home.Footnote94

Understanding the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on children and young people’s experience of play has also been enhanced by wider studies on children’s pandemic experiences. Concerns have been expressed over social isolation and loneliness among children and young people as the peer interaction which occurs through play decreases, with evidence suggesting an increase of approximately 50% in loneliness compared to pre-pandemic levels.Footnote95 Worryingly, in the COVID-19 context, it is the duration of loneliness, rather than its intensity, which is most strongly related to poor outcomes. Although the British Psychological SocietyFootnote96 reported that some children may have coped well during the school closures, they stressed that others may have experienced considerable trauma, loss, and hardship. It is observed that restrictions on social, leisure and learning opportunities may have increased children’s sense of powerlessness and for some this will have been an isolating and unpleasant experience.

Against this backdrop, it is perhaps not surprising that the Commissioner for Children and Young People, Scotland felt it necessary to point out in the independent CRIA that the rights protected by Article 31 of the UNCRC are ‘not optional extras, they are necessary to protect the unique and evolving nature of childhood’. The independent CRIA found that restrictions (such as limits on time outdoors and physical distancing) and closures (of playgrounds, schools, cultural and public spaces) had significant negative implications for children and young people’s access to rest, leisure, recreation and cultural and artistic activities (UNCRC Article 31) and, closely associated with Article 31, freedom of expression (Article 13 CRC, Article 10 ECHR), to freedom of association and peaceful assembly (UNCRC Article 15, Article 11 ECHR), to children’s right to exercise choice in what is described a form of ‘everyday participation’ and disabled children’s fundamental freedoms enshrined in Article 7 (UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRCPD)) and right to play in UNCRPD Article 30. These restrictions, though experienced differently by children in different circumstances, overall led to significant and sudden changes for almost all children and young people, hastening a retreat from the public realm into their homes.

The balance of evidence reaffirms that children and young people’s play has been curtailed and weakened in the COVID-19 crisis. Rights to play have been overlooked. It need not be so, and there are exemplars of organisations that have striven to protect and promote the right to play through the crisis.

The global project to promote the right to play in a crisis

Six months after the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared COVID-19 a global pandemic, the International Play Association sought submissions for a special award to recognise innovation that supported play during the pandemic. Projects had to be replicable and fully or partially implemented at the time of submission. Twenty-three from 14 countries were judged to have demonstrated that they protected, promoted, or improved children’s right to play during COVID-19 (). Implemented in the early stages of the pandemic, some required significant agility from the organisers to adapt to changing local conditions and restrictions.

Table 2. Exemplars of Promoting Play in COVID-19 Times (International Play Association).

As reports, most projects supported play at home, (using online platforms, and/or providing material resources), although some innovations created new play spaces or presented play sessions. Most were from Europe (13) or Central and East Asia (7), with four countries accounting for more than one-half of the exemplars (Scotland, India, New Zealand/Aotearoa, and Portugal). No examples were included from the Americas. A common approach was to enable adults to support children’s play, acknowledging the crucial role of parents and carers in facilitating play for young children. Many of the initiatives targeted younger children, although examples of those targeting teenage children were also celebrated.

The scale and reach of the projects varied. Some were highly localised, such as the adventure playground in Chiba (Japan), introduced following playworkers’ observations that children ‘desperately needed somewhere to be’. In contrast, Apalam Chapalam, (across India) reached more than 200,000 children through their social media channels, in a collaborative effort with 60 NGOs and 40 storytellers. Collaborative initiatives – including a coming together of community groups, foodbanks, schools and other institutions, involving storytellers, writers, artists, drama pedagogues, playworkers and play specialists – can be contrasted to others such as that in Chiba that are the work of one professional grouping.

In reflecting on play in earlier crises, Chatterjee describes how the presence of supportive adults, spaces with rich environmental affordances, and fewer restrictions on children’s time facilitated access to play. Under these conditions ‘play emerged as a living resource and not a commodified product, a resource that allowed children to regain and retain normality under the most difficult and challenging living conditions’.Footnote97 Most of the projects (nineteen) in this IPA awards programme were implemented by third sector organisations (non-governmental and not-for-profit organisations and associations, including charities, social enterprises, voluntary and community groups); only one was implemented by a national government department and three by local government.

Governments are guided by the UNCRC to develop a dedicated plan, policy, or framework for Article 31 or to incorporate the right to play in an overall national plan to implement the Convention. The experience of the pandemic points to significant shortcomings in these national action plans, impacting on children of all age groups, but especially so for children in marginalised groups and communities. The independent CRIA in Scotland recognised that, despite the efforts of parents and carers, opportunities to play, to socialise with friends, and to express creativity and imagination have all been limited, and some groups of children (those who live in poverty, in inadequate housing, and with little access to physical space or to an online community) have been particularly affected. At the time of its writing, the return to school was proposed as an opportunity for children to play and rebuild relationships, with the Children and Young People’s Commissioner, Scotland urging Scottish Government and local authorities to fund and support options such as outdoor and play-based learning.Footnote98 We would contend that realising the right to play need not wait for a return to school: as evidenced in , many means are available to reach many thousands of children in local, digital, non-digital and hybrid play-space.

It is important to recognise that other new web-based resources have emerged to support play at home, some of which were implemented or adapted quickly by Government – Let’s Play Ireland website Footnote99, Scotland’s Parent ClubFootnote100, and Playful ChildhoodsFootnote101 in Wales. A shared sense of collective purpose was also evidenced by resource sharing and translation of resources into local languages, and a concern to disseminate knowledge to parents and carers.Footnote102

Conclusion: rethinking play, rights, and crisis

We identified three narratives of play and crisis: the sense of play in crisis, a belief that crisis curtails play, and a re-appraisal that positions play as a remedy to (some of the) problems of crisis situations.

The COVID-19 pandemic afforded an opportunity to reappraise the status of play as a fundamental right of the child through the lens of play in crisis. However, children’s right to play was curtailed as it became collateral damage when managing the threat to public health.Footnote103 Although those wedded to a fundamentalist view of the right to play may be critical of the curtailment of opportunity for play in public and commercial realms, many would understand the imperative of public health management.Footnote104 More telling is that the staged lifting of restrictions highlighted the standing of play relative to other human rights, with the desire to facilitate return to work, children’s education and adult leisure being prioritised over facilitating opportunities for children’s play. Although it would be an overstatement to claim that play was totally ignored –for example, the Scottish Government supported organised outdoor play as part of its Get Into SummerFootnote105 investment in 2021 – it was not a universal priority or concern and it has been left to stakeholders and independent analysts to assess impact of children’s loss of play.Footnote106 Rather than a global project, efforts to sustain the right to play were concentrated in pockets of action, some local, some national, in disparate parts of the world.

From a children’s rights perspective, it is also significant that play was often placed in the orbit of adult control, even by those seeking to facilitate it in the COVID times, with a heightened focus on play in the domestic realm. This might be viewed as regressive in that the close presence of significant adults perhaps implies less autonomy and freedom within play, and of course the restriction to the domestic realm removes opportunities for play. On the other hand, the greater time spent in the home space during lockdown may have strengthened the home as a time–space for play and there may now be a stronger inclination to embrace digital play. It may also be speculated whether the stresses of parenting in lockdown have heightened awareness of the adverse impact of over-parenting, and the value for society of affording children more opportunities and earlier opportunities to exert autonomy and freedom through play.

Although there is evidence of governments intervening to support play in the COVID-19 pandemic, there remains a need for better understanding of the importance of play, and more robust and wide-ranging actions, not least to meet their obligations under Article 31 of the UNCRC. If anything, the COVID-19 crisis has highlighted the critical importance of play in children’s lives. Although grassroots organisations and ‘bottom-up’ initiatives often provide rich opportunity that is grounded in an understanding of the wider significance of play, play is too important to be left to the vagaries and chance of what local groups and small NGOs may or may not be able to support.

There are also now many examples of promising – if not fully evidenced – practice of supporting play in crisis situations, to complement the bank of evidence that already exists on the instrumental value of play. While, sadly, the concerns expressed in the independent CRIA over the potential negative impact of COVID-19 measures on children and their right to play were subsequently borne out, the COVID-19 pandemic has also stimulated interest in understanding the nature of play in children’s lives and has resulted in new insights from, and engagement with play, from many researchers across many disciplines.

In this crisis, may be the seeds of opportunity to sustain and strengthen our support for children’s right to play and to work toward restoring the everydayness of play for all children, in crisis or not.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Theresa Casey

Theresa Casey served as President of the International Play Association: Promoting the Child's Right to Play (IPA) from 2008-2017. With the IPA Board and Council she coordinated the initiatives leading to the publication of General Comment No. 17 on the right of the child to rest, leisure, play, recreational activities, cultural life and the arts (article 31 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child). In her final term as president (2014-17), Theresa led IPA's thematic work on Children's Rights and the Environment and Access to Play in Crisis. This formed the foundation for IPA's response to coronavirus in the Play in Crisis for Parents and Carers resources 2020, rapidly translated into a number of languages and updated in 2022 in response to new crises impacting on children's rights. In 2013, she drafted the Scottish Government's Play Strategy Action Plan and took up the role of vice-chair of the implementation group. She has an honours degree in painting and a post-graduate certificate in playwork. Her playwork practice began in an adventure playground in Scotland and led to play development in Thailand where she worked for three years. Theresa is a freelance consultant and writer on play, inclusion and children's rights and frequent presenter at conferences in Scotland and internationally. She was the article 31 lead for the Independent Children's Rights Impact Assessment (Children and Young People's Commissioner Scotland and the Observatory of Children's Human Rights Scotland, 2020). Other recent publications include Play provision: realising disabled children's rights (Play Wales, 2021) Free to Play: a guide to creating accessible and inclusive public play spaces (Inspiring Scotland, 2018); Loose Parts Play Toolkit (2018, Inspiring Scotland), Play Types: bringing more play into the school day (Play Scotland, 2017), Inclusive Play Space Guide: championing better and more inclusive play spaces in Hong Kong (PlayRight Child's Play Association & UNICEF, 2016).

John H. McKendrick

John H. McKendrick is Professor & Co-Director of the Scottish Poverty and Inequality Research Unit in the Glasgow School for Business and Society at Glasgow Caledonian University in Glasgow, Scotland. John’s research interests span the studies of the provision of environments for children, children’s use of space, children’s play, and child poverty. He was on the Board of Directors of Play Scotland from 2007-2017, writing several research reports including School Grounds in Scotland (2005), Local Authority Play Provision in Scotland (2007), Developing Play in Scotland (2008) and the Scottish National Play Barometer (2013). His earliest work in the field of play was The Business of Children’s Play, an examination of the commercial provision of play space for young children in the UK (funded by the Economic and Social Research Council). He has delivered keynote addresses to conferences convened by PlayBoard Northern Ireland, Play Scotland, Skillsactive, Yorkshire Play, Children’s Play Council, European Cities for Children, Generation Youth, European Child in the City and Play Education. He has experience with presenting research findings to a wide range of user groups and is committed to applied research. In 2019, he edited a collection of papers on play and education in Scotland (Scottish Educational Review); in 2018, he co-edited a collection of papers on “The Playway to the Entrepreneurial City” for the Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation. He has also edited two collections of papers examining the impact of Austerity on playwork (Journal of Playwork Practice, 2014) and playspace provision (International Journal of Play, 2015) and an earlier collection of papers on “Children's Playgrounds in the Built Environment,” a 1999 special edition of Built Environment. More importantly, he is dad to Lauren (32), Corrie (27) and Morven (12) and granddad to Finn (6) and Shay (3).

Notes

1 Robin C. Moore, Childhood’s Domain: Play and Place in Child Development (London: Croom Helm, 1986).

2 Lothar Krappmann, ‘An Inalienable Human Right: Finally, a General Comment on the Right to Play’, IPA PlayRights Magazine 1, no. 13 (2013): 26–9 and 38.

3 United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, General Comment No. 17 on the Right of the Child to Rest, Leisure, Play, Recreational Activities, Cultural Life, and the Arts (art. 31) CRC/C/GC/17 (UNCRC, 2013) para. 14c

4 Pat Kane, The Play Ethic: A Manifesto for a Different Way of Living (London: Pan Macmillan, 2005).

5 Tim Hawkes, ‘Home Work or Home Play: A Case for Homework’, Australian Educational Leader 28, no. 4 (2006): 24–5.

6 Peter Blatchford, ‘Taking Pupils Seriously: Recent Research and Initiatives on Breaktime in Schools’, Education 3–13 24, no. 3 (1996): 60–5.

7 John H. McKendrick, ‘Playgrounds in the Built Environment’, Built Environment 25, no. 1 (1999): 4–10.

8 Colin Ward, The Child in the City (London: Architectural Press, 1978).

9 John H. McKendrick and others, ‘Bursting the Bubble or Opening the Door? Appraising the Impact of Austerity on Playwork and Playwork Practitioners in the UK’, Journal of Playwork Practice 1, no. 1 (2014): 61–9.

10 Stephen Dobson and John H. McKendrick, ‘Intrapreneurial Spaces to Entrepreneurial Cities: Making Sense of Play and Playfulness’, The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 19, no. 2 (2018): 75–80.

11 Hana Haiat and others, ‘The World of the Child: A World of Play Even in the Hospital’, Journal of Paediatric Nursing 18, no. 3 (2003): 209–14.

12 Charmian Hobbs and others, Children’s Right to Play. (Leicester: Division of Educational and Child Psychology Position Paper, British Psychological Society, 2019).

13 Children and Young People’s Commissioner Scotland and the Observatory of Children’s Human Rights Scotland, Independent Children’s Rights Impact Assessment (Edinburgh: CYPCS and OCHRS, 2020).

14 United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, ‘The CRC Warns of the Grave Physical Emotional and Psychological Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children and Calls on States to Protect the Rights of Children’ in Compilation of Statements by Human Rights Treaty Bodies in the Context of COVID-19 (OHCRG, 2020): 34–36.

15 United Nations, Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, 1948).

16 United Nations, Declaration of the Rights of the Child (United Nations, 1959).

17 International Play Association (IPA), IPA Declaration of the Child’s Right to Play [online article] (1979). http://ipaworld.org/about-us/declaration/ipa-declaration-of-the-childs-right-to-play/

18 UNICEF, Implementation Handbook for the Convention on the Rights of the Child, Fully Revised Third Edition (United Nations Children’s Fund, 2007).

19 United Nations, Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations, 1989).

20 Paulo David, A Commentary on the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, Article 31: The Right to Leisure, Play and Culture (Leiden: Brill, 2006).

21 A coalition of international associations first wrote to Ms Yanghee Lee, chair of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child on 6th May 2008 requesting the Committee organise a Day of Discussion and/or a General Comment on article 31.

22 Valerie Fronczek, ‘Article 31: A Forgotten Article of the UNCRC’, Early Childhood Matters (Realising the Rights of Young Children: Progress and Challenges) 113 (2009): 24–8.

23 Jacob Doek, ‘Children and the Right to Play’ (paper presented at the International Play Association 17th Triennial Conference “Play in a Changing World”, Hong Kong, January 2008).

24 Ciara Davey and Laura Lundy, ‘Towards Greater Recognition of the Right to Play: An Analysis of Article 31 of the UNCRC’, Children & Society 25, no. 1 (2011): 3–14.

25 Liz Brooker and Martin Woodhead, editors, The Right to Play. Early Childhood in Focus 9 (The Hague, Bernard van Leer Foundation, 2003).

26 Jaume Bantulà Janot and Andrés Payà Rico, ‘The Right of the Child to Play in the National Reports Submitted to the Committee on the Rights of the Child’, International Journal of Play 9, no. 4 (2020): 400–13.

27 The six States Parties that received recommendations are: Belgium, Croatia, Denmark, Spain, Latvia, and United Kingdom and Northern Ireland.

28 David Whitebread, and others, The Importance of Play: A Report on the Value of Children’s play with a Series of Policy Recommendations (Brussels: Toy Industries of Europe, 2012).

29 Alice Ferguson and Angie Page, ‘Supporting Healthy Street Play on a Budget: A Winner from Every Perspective’, International Journal of Play 4, no. 3 (2015): 266–9.

30 Susan Elsley, ‘Children's Experience of Public Space’, Children & Society 18, no. 2 (2004): 155–64.

31 Paul Tranter and John W. Doyle, ‘Reclaiming the Residential Street as Play Space’, International Play Journal 4 (1996): 91–7.

32 Sarah Irwin and Sharon Elley, ‘Concerted Cultivation? Parenting Values, Education and Class Diversity’, Sociology 45, no. 3 (2011): 480–95.

33 Tim Gill, No Fear Growing up in a Risk Averse Society (London: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, 2000).

34 Mariana Brussoni and others, ‘What is the Relationship Between Risky Outdoor Play and Health in Children? A Systematic Review’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 12, no. 6 (2015): 6423–54.

35 Rhoda Clements, ‘An Investigation of the Status of Outdoor Play’, Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 5, no. 1 (2004): 68–80.

36 John H. McKendrick and others, ‘Kid Customer? Commercialization of Playspace and the Commodification of Childhood’, Childhood 7, no. 3 (2000): 295–314.

37 Peter Gray, ‘The Decline of Play and the Rise of Psychopathology in Children and Adolescents’, American Journal of Play 3, no. 4 (2011): 443–63.

38 Stephanie Schoeppe and others, ‘Associations between Children’s Independent Mobility and Physical Activity’, BMC Public Health 14, no. 1 (2014): 1–9.

39 Karen Witten and others, ‘New Zealand Parents' Understandings of the Intergenerational Decline in Children's Independent Outdoor Play and Active Travel’, Children's Geographies 11, no. 2 (2013): 215–29.

40 Amine Moulay and others, ‘Legibility of Neighborhood Parks as a Predicator for Enhanced Social Interaction Towards Social Sustainability’, Cities 61 (2017): 58–64.

41 Paul Hocker, ‘A Play Space to Beat All’, Journal of Playwork Practice, 1, no. 1 (2014): 104–8.

42 John H. McKendrick, ‘Shall the Twain Meet? Prospects for a Playfully Play-full Scottish Education’, Scottish Educational Review 51, no. 2 (2019): 3–13.

43 Avril Johnstone and others, ‘Utilising Active Play Interventions to Promote Physical Activity and Improve Fundamental Movement Skills in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis’, BMC Public Health 18, no. 1 (2018): 1–12.

44 David Whitebread, ‘Free Play and Children's Mental Health’, The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health 1, no. 3 (2017): 167–9.

45 Valerie Wright and others, ‘Planning for Play: Seventy Years of Ineffective Public Policy? The Example of Glasgow, Scotland’, Planning Perspectives 34, no. 2 (2019): 243–63.

46 Stuart Lester and Wendy Russell, Play for a Change (London: Play England, 2008).

47 UNHCR, ‘Figures at a glance’, [online article] (2021) https://www.unhcr.org/uk/figures-at-a-glance.html

48 Marit Heldal, ‘Perspectives on Children's Play in a Refugee Camp’, Interchange 52 (2021): 433–45.

49 Colin Ward, ‘The Child in the City’, see note 8.

50 Stuart Lester and Wendy Russell, Children’s Right to Play: An Examination of the Importance of Play in the Lives of Children Worldwide (The Hague: Bernard van Leer Foundation, 2010).

51 Lester and Russell, ‘Children’s Right to Play’, see note 50.

52 Sudeshna Chatterjee, Access to Play for Children in Situations of Crisis: Synthesis of Research in Six Countries (International Play Association, 2017).

53 Helen Woolley and Isami Kinoshita, ‘Space, People, Interventions and Time (SPIT): A Model for Understanding Children’s Outdoor Play in Post-Disaster Contexts Based on a Case Study from the Triple Disaster Area of Tohoku in North-East Japan’, Children & Society 29, no. 5 (2014): 434–50.

54 Esther Cohen and others, ‘Making Room for Play: An Innovative Intervention for Toddlers and Families Under Rocket Fire’, Clinical Social Work Journal 42 (2014): 336–45.

55 Alison Tonkin and Julia Whitaker, ‘Play and Playfulness for Health and Wellbeing: A Panacea for Mitigating the Impact of Coronavirus (COVID 19)’, Social Sciences & Humanities Open 4, no. 1 (2021): 100142.

56 Ted Varkas, ‘Childhood Trauma and Posttraumatic Play: A Literature Review and Case Study’, Journal of Analytic Social Work 5, no. 3 (1998): 29–50.

57 Esther Cohen and others, ‘Posttraumatic Play in Young Children Exposed to Terrorism: An Empirical Study’, Infant Mental Health Journal 31 (2010): 159–81.

58 Lester and Russell, ‘Play for a Change’, see note 46.

59 Robert Henley and others, ‘How Psychosocial Sport & Play Programs Help Youth Manage Adversity: A Review of What We Know & What We Should Research’, International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation 12 (2007): 51–8.

60 Maggie Fearn and Justine Howard, ‘Play as a Resource for Children Facing Adversity: An Exploration of Indicative Case Studies’, Children & Society 26 (2012): 456–68.

61 Carers Trust Scotland, 2020 Vision: Hear Me, See Me, Support Me and Don’t Forget Me: The Impact of Coronavirus on Young and Young Adult Carers in Scotland, and What They Want You to do Next (London: Carers Trust, 2020).

62 Girlguiding, Girlguiding Research Briefing: Early Findings on the Impact of COVID-19 on Girls and Young Women (London: Girlguiding, 2020).

63 Children’s Commissioner for England, Tackling the Disadvantage Gap During the Covid-19 Crisis (London: Children’s Commissioner for England, 2020).

64 Family Fund, The Impact of COVID-19 - A Year in the Life of Families Raising Disabled and Seriously Ill Young Children. Scotland Findings – March 2021 (York: Family Fund, 2020).

65 Megan Watson and others, COVID-19 Early Years Resilience and Impact Survey (CEYRIS). How Did COVID-19 Affect Children in Scotland? Report 2 – Play and Learning, Outdoors and Social Interactions (Edinburgh: Public Health Scotland, 2020).

66 Neil Chanchlani and others, ‘Addressing the Indirect Effects of COVID-19 on the Health of Children and Young People’, Canadian Medical Association Journal 192, no. 32 (2020): E921–7.

67 United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, see note 14.

68 Scottish Government, UN Committee on the Rights of the Child: COVID-19 Statement (Edinburgh: Scottish Government, 2020). This is a response to each of the eleven recommendations of the UNCRC.

69 Kate Cowan and others, ‘Children’s Digital Play during the COVID 19 Pandemic: Insights from the Play Observatory’, Journal of e-Learning and Knowledge Society 17 (2021): 8–17.

70 Together (Scottish Alliance for Children’s Rights), Analysis of Scottish Government’s Response to UN Committee’s 11 recommendations (Edinburgh: Together, 2020).

71 Sally C Davies and others, ‘United Kingdom Chief Medical Officers’ Commentary on ‘Screen-based Activities and Children and Young People’s Mental Health and Psychosocial Wellbeing: A Systematic Map of Reviews’ (London: Office of the Chief Medical Officer, Department of Health and Social Care, 2019).

72 Daniel Kardefelt Winther and Jasmina Byrne, ‘Rethinking Screen-Time in the Time of COVID-19. How Can Families Make the Most of Increased Reliance on Screens — Which are Helping to Maintain a Sense of Normalcy During Lockdown?, [online article] Office of Global Insight and Policy, UNICEF, https://www.unicef.org/globalinsight/stories/rethinking-screen-time-time-covid-19 (accessed November 11, 2021).

73 Children’s Parliament, How Are You Doing? Survey Report (Edinburgh: Children’s Parliament, 2020); Girlguiding, Girlguiding Research Briefing: Early Findings on the Impact of COVID-19 on Girls and Young Women (London: Girlguiding, 2020); Young Scot, Lockdown Lowdown Breakdown of Key Findings (Edinburgh: Young Scot, 2020).

74 Public Health Scotland, The Impact of COVID-19 on Children and Young People in Scotland: 10–17 Years-Olds (Edinburgh: Public Health Scotland, 2021); Public Health Scotland, The Impact of COVID-19 on Children and Young People in Scotland: 2–4 Year-Olds (Edinburgh: Public Health Scotland, 2021).

75 Carol Barron and others, ‘Indoor Play During a Global Pandemic: Commonalities and Diversities During a Unique Snapshot in Time’, International Journal of Play (2021): DOI: 10.1080/21594937.2021.2005396.

76 Kate Cowan and John Potter, ‘Children’s Digital Play During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Insights from the Play Observatory’, Journal of e-Learning and Knowledge Society 17, no. 3 (2021): 8–17.

77 Louise de Lannoy and others, ‘Regional Differences in Access to the Outdoors and Outdoor Play of Canadian Children and Youth During the COVID-19 Outbreak’, Canadian Journal of Public Health 111, no. 6 (2020): 988–94.

78 Tim Gill and Robyn M. Miller, Play in Lockdown: An International Study of Government and Civil Society Responses and their Impact on Children’s Play and Mobility (International Play Association, 2020).

79 Gülçin Karadeniz and Çakmakcı Kahyaoğlu, ‘Turkish Fathers' Play Attitude with Children During Covid-19 Lockdown’, European Journal of Education Studies 8, no. 2 (2021).

80 Pete King, ‘How have Adventure Playgrounds in the United Kingdom Adapted post-March Lockdown in 2020?’, International Journal of Playwork Practice 2, no. 1 (2021).

81 Lauren McNamara, ‘School Recess and Pandemic Recovery Efforts: Ensuring a Climate that Supports Positive Social Connection and Meaningful Play’, Facets 6, no. 1 (2020): 1814–30.

82 Lindsay A. Thompson and Maria Kelly, ‘Return to Play After COVID-19 Infection in Children’, JAMA Pediatrics 175, no. 8 (2021): 875–5.

83 Steven Holiday, ‘Where do the Children Play … in a Pandemic?’, Journal of Children and Media 15, no. 1 (2021): 81–4.

84 Sarah A. Moore and others, ‘Impact of the COVID-19 Virus Outbreak on Movement and Play Behaviours of Canadian Children and Youth: A National Survey’, International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 17, no. 1 (2020): 1–11.

85 Christina O’Keeffe and Sinead McNally, ‘‘Uncharted territory’: Teachers’ Perspectives on Play in Early Childhood Classrooms in Ireland during the Pandemic’, European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 29, no. 1 (2021): 79–95.

86 Wendy Russell and Alison Stenning, ‘Beyond Active Travel: Children, Play and Community on Streets During and After the Coronavirus Lockdown’, Cities & Health (2020): DOI: 10.1080/23748834.2020.1795386.

87 Hannah Wright and Mitchell Reardon, ‘COVID-19: A Chance to Reallocate Street Space to the Benefit of Children’s Health? Cities & Health (2021): DOI: 10.1080/23748834.2021.1912571.

88 Public Health Scotland, see note 74.

89 de Lannoy and others, 2020, see note 77.

90 Barron and others, 2021, see note 75.

91 Great Ormond Street Hospital, The Power of Play (London, GOSH, 2020).

92 King, 2021, see note 80.

93 Moore and others, 2021, see note 84.

94 Monika Szpunar and others, ‘Children and Parents’ Perspectives of the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Ontario Children’s Physical Activity, Play, and Sport Behaviours’, BMC Public Health 21, no. 1 (2021): 1–17.

95 Sam Cartwright-Hatton and others, Play First: Supporting Children’s Social and Emotional Wellbeing During and After Lockdown (Brighton: Play First, 2020).

96 British Psychological Society, Back to School: Using Psychological Perspectives to Support Re-Engagement and Recovery (Leicester: British Psychological Society, 2020).

97 Sudeshna Chatterjee, see note 52.

98 Children and Young People’s Commissioner, Scotland, p8-9, see note 13.

99 Let’s Play Ireland, https://www.gov.ie/en/campaigns/lets-play-ireland/.

100 Parent Club, https://www.parentclub.scot/.

101 Playful Childhoods, www.playfulchildhoodswales.

102 International Play Association, For Parents and Carers: Play in Crisis, https://ipaworld.org/resources/for-parents-and-carers-play-in-crisis (accessed November 11, 2021). These ten leaflets were translated by local partners.

103 Tim Gill and Robyn Monro Miller, Play in Lockdown (International Play Association, 2020).

104 Amnesty International UK, Briefing – Coronavirus (Extension and Expiry) (Scotland) Bill (London, Amnesty International UK: 2021).

105 A Scottish Government Fund to help charities who facilitate outdoor play for children and their families during COVID-19.

106 Play Scotland, Play and Childcare Settings: The Impact of COVID-19 (Edinburgh: Play Scotland, 2020).