ABSTRACT

We investigated whether primary-school teachers’ beliefs towards early-English education are related to the type of English education they are involved in (early- or later-English schools), their English language skills and whether they teach English. Ninety-nine Dutch teachers filled in a questionnaire with 25 statements about early-English education, and assessed their own English speaking proficiency. Their beliefs were based on the effects of three distinct components: Communicative scope, Disadvantaged learning, and their own skills for teaching English. Regression analyses showed that teachers working at an early-English school generally hold more positive beliefs about the effects of early-English education than teachers working at a later-English school. Furthermore, teachers who taught English lessons themselves and teachers who assessed their own English speaking proficiency at a higher level, showed less negative beliefs about the effects of early-English education for Disadvantaged learning, and had more positive beliefs about their own English teaching skills. Teachers with a higher self-rated speaking proficiency showed more positive beliefs about the effects of early-English education on Communicative scope development. This study shows that teachers’ beliefs and skills concerning English education are related to each other. Pre- and in-service training on providing English lessons should thus pay attention to both.

Introduction

Since the turn of the century, the number of European primary schools that provide early foreign language education is rapidly growing (Enever et al. Citation2011). In the Netherlands, almost one in five primary schools provides a foreign language from kindergarten onwards, instead of starting in the penultimate grade (Nuffic Citation2017). In more than 90% of the cases, English is that foreign language (Jenniskens et al. Citation2017; Nuffic Citation2017). In 85% of these schools, the regular class teacher teaches these lessons. Otherwise, the regular class teacher co-teaches with a native-speaker specialist teacher (approximately 10%), or lessons are provided by a native-speaker specialist teacher only (<3%) (Jenniskens et al. Citation2017). This is the common situation in other European countries too (Nikolov and Djigunovic Citation2011).

These numbers show that generalist class teachers are heavily involved in early foreign language education. Given the governmental stimulations of foreign language learning programmes in early primary school (Enever et al. Citation2011; Nuffic Citation2020), even more teachers will be involved in this educational innovation in the near future. Since the generalist teachers are mainly providing the lessons, successful implementation of early foreign language education depends to a great deal on them. Educational innovations such as this one will only be successful when teachers are positive about it, and feel involved in its implementation (Vähäsantanen Citation2015). This study investigated teachers’ beliefs about early-English education, how they assess their own language teaching skills, and whether these skills are related to their beliefs.

Early-English education in the Netherlands

Since 1986 primary-school pupils in Dutch mainstream schools receive lessons in English as a foreign language from the penultimate grade onwards (Thijs et al. Citation2011a). Pupils are then about 11 years old. An increasing number of schools started providing English lessons from the middle of primary school onwards, or even from the moment children enter kindergarten at the age of four (Nuffic Citation2017). Both early-English schools and mainstream schools (later-English schools) usually provide 45–60 minutes of English per week (Dutch Inspectorate of Education Citation2019; Jenniskens et al. Citation2017). Contrary to Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL), English lessons in Dutch primary schools are often stand-alone lessons. Only sometimes (less than 20% of the time) English is integrated within other subjects, like arts and crafts or gymnastics (Dutch Inspectorate of Education Citation2019; Jenniskens et al. Citation2017). Despite the fact that practices differ from school to school and from teacher to teacher, English lessons – whether in later- or early-English schools – are mainly focused on speaking skills, listening skills, and vocabulary knowledge (Dutch Inspectorate of Education Citation2019). To provide English lessons for young children, teachers are assumed to follow in-service training on English language use in the classroom. Teachers’ level of English should also at least be intermediate: for speaking, listening and reading it should be at B2-level of the Common European Reference Framework for Languages. For writing, B1-level is deemed sufficient (Council of Europe Citation2018; Nuffic Citationn.d.). These requirements are comparable to those in most other European countries (Enever Citation2014).

Beliefs

Teachers’ beliefs can be defined as a cluster of conceptual representations, which are given, true, or trustworthy to their beholder, and teachers may rely on these clusters in their personal thoughts and actions (Fang Citation2006; Gao Citation2014). Importantly, however, beliefs do not necessarily need to be true, as they need not to be based on objective information (Gao Citation2014).

Teachers’ beliefs may be explicit (and teachers may articulate their beliefs) as well as implicit (in which case teachers do not want or are not able to articulate their beliefs) (Borg Citation2001). Beliefs may become visible in teachers’ expectations about students’ learning, or their theories about learning and teaching. Teachers’ beliefs may thus affect their classroom practices, and thereby students’ learning (Fang Citation2006).

Teachers’ beliefs about benefits of early-English education for children, and about their own skills in teaching English

Several studies have investigated early-English teachers’ beliefs about the effects of early-English education. Teachers often reported positive beliefs. These positive beliefs relate to pupils’ development, but also to teachers’ own professional skills and development. In a questionnaire administered among Dutch teachers, for example, 92% of the respondents thought early-English lessons are important and appealing to pupils, and it is fun to teach those lessons (Thijs, Tuin, and Trimbos Citation2011b). A more recent but small-scale study from a pilot with 11 teachers from the Netherlands teaching 50% of the lessons in English shows that teachers like to teach in English, and they believe pupils have fun learning English (Jenniskens et al. Citation2020). Data from other countries mirror those findings. Italian CLIL teachers, for example, said to believe that CLIL is effective for pupils’ development of English, and that it improves their own teaching practices (Infante, Benvenuto, and Lastrucci Citation2009). Research among teachers in Poland showed that teachers experienced satisfaction from providing bilingual education (Czura, Papaja, and Urbaniak Citation2009). Finally, early-English teachers from Spain reported that they believe that young pupils learn a language more effectively than older pupils (Pena Diaz and Porto Requejo Citation2008).

Yet, teachers in those previous studies were not only positive about English education for young children. Dutch teachers thought that early-English education is disadvantageous rather than beneficial to several groups of pupils, such as pupils with dyslexia or pupils who did not speak the majority language at home. They believed that for these pupils, learning activities in Dutch are already difficult enough (Thijs, Tuin, and Trimbos Citation2011b). Another study showed that Dutch teachers sometimes believe Dutch children find lessons in English difficult, and that bilingual education is not beneficial for all children (Jenniskens et al. Citation2020). Spanish teachers also sometimes believed early-English education does not meet the needs of pupils who struggle with learning difficulties (Pena Diaz and Porto Requejo Citation2008). In addition, teachers were often concerned about pupils’ Spanish language development, and they sometimes even believed that pupils’ first language (L1) development would be negatively influenced by early-English education (Pena Diaz and Porto Requejo Citation2008). In line with these findings, research with pre- and in-service teachers from Poland, Greece, and Cyprus showed that especially Polish and Cypriot teachers believed themselves not to be well prepared to include dyslexic learners in their English lessons. This held even more for teachers teaching young children than for teachers teaching in secondary school or higher education (Nijakowska, Tsagari, and Spanoudis Citation2018). In a study among German primary school teachers, teachers reported to believe that including pupils with special educational needs in English lessons would be especially non-beneficial to those pupils’ subject knowledge (Porsch and Wilden Citation2021).

With respect to their own didactical (teaching) practices, teachers often reported negative beliefs. In the Dutch questionnaire study (Thijs et al. Citation2011a), almost 50% of the participating early-English teachers felt insufficiently equipped to select appropriate learning materials and sources for their English lessons. In addition, 76% reported having insufficient knowledge of didactical approaches for English education, which they blame on the lack of instruction during teacher training (Thijs et al. Citation2011a). Research from Spain and Poland yielded similar results, with teachers reporting feeling insecure about the specific knowledge of bilingual teaching methodology (Pena Diaz and Porto Requejo Citation2008), and lacking specific training in providing English lessons to young children (Czura, Papaja, and Urbaniak Citation2009).

And finally, regarding their own English language skills, teachers often report negative beliefs, too. In the Spanish questionnaire study, for example, 80% of the respondents believed their English proficiency level was too low to teach English. Only 50% of the teachers indicated using English all the time, and 30% reported using English only half of the time. In general, teachers felt insecure about their general level of English and their fluency in that language in particular (Pena Diaz and Porto Requejo Citation2008). Questionnaire data from Dutch early-English teachers yielded a somewhat more positive picture. Still, 12% of the respondents felt their language proficiency was not sufficient to use English as the language of instruction, and 29% thought their English proficiency was lower than the required B2 level (Thijs, Tuin, and Trimbos Citation2011b). Later studies among Dutch teachers have confirmed these findings (Dutch Inspectorate of Education Citation2019; Jenniskens et al. Citation2017).

Teachers’ negative beliefs about their English language and teaching skills, as well as their actual language skills, may in turn negatively influence pupils’ knowledge of English. Research showed that kindergarten pupils who were educated by a teacher with an English proficiency level at B-level only, scored significantly lower on English vocabulary and grammar tests than their peers educated by teachers with a proficiency at C-level, even when controlling for the amount of instruction time in English (Unsworth et al. Citation2015). In addition, research has shown that teachers’ negative beliefs about their competencies may influence their classroom practices. Enever (Citation2014), for example, investigated teacher beliefs in four cases: two teachers from Italy, and two from Sweden. Three of these teachers believed their own language competency was substandard, and they experienced anxiety with regard to their language competency. Classroom observations showed that these teachers were inclined to use the L1 more often than necessary, and in an unplanned an inessential way. Furthermore, they lacked the expertise to offer interaction tasks in a structured way necessary to maximize foreign language production. Judicious use of the L1 can benefit pupils’ English learning (Shin, Dixon, and Choi Citation2020), but rich English input is also needed for pupils to improve their English skills (De Graaff and Costache Citation2020; Enever Citation2014).

In summary, previous research has shown that despite the fact that teachers are generally fairly positive about the concept of early-English education, they also see certain downsides and they often report being insecure about their own language and didactical competencies with regard to English teaching. These previous studies were however mainly based on small numbers of respondents, and concentrated on teachers who were already involved in early-English teachers – with the study of Thijs et al. (Citation2011a) being the exception. Furthermore, previous studies investigated teachers’ self-ratings of their language proficiency, didactical competences, and beliefs about early-English education, but did not investigate the relation between these variables.

Early-English education has not always proved effective, with mainstream pupils obtaining similar or higher scores on English vocabulary (Goriot et al. Citation2018) and speech perception (Goriot et al. Citation2020) tests. A variety of factors may account for this lack of effectiveness. Dutch people generally have a good command of English (EPI Citation2018). English is very present in Dutch society (Kuppens Citation2010) and children may also acquire English without formal schooling (De Wilde, Brysbaert, and Eyckmans Citation2020; Puimège and Peters Citation2019). Next to that, teachers’ proficiency level (Unsworth et al. Citation2015), and didactical expertise (Enever Citation2014) may play a role too.

This questionnaire study provides a first attempt to link teachers’ beliefs about their didactical skills and English language proficiency, to their beliefs about early-English education. In contrast to previous studies, both teachers from early-English and later-English schools were included. The study focuses on three components that have been frequently mentioned in the literature: positive effects on pupils’ communicative development, negative effects for pupils with learning difficulties, and positive effects on teachers’ teaching skills. Our hypothesis was that teachers from early-English schools would be more positive than teachers from later-English schools on all three components, such that they are more positive about the effects on pupils’ communicative development, less negative about downsides of early-English education for pupils with learning difficulties, and more positive about the effects on their own teaching’ skills. At the same time, teachers (1) who are more proficient in English and/or (2) who are actually teaching English, may have more positive beliefs about the effects of early-English. We, therefore, investigated these two factors in relation to the factor of teaching at an early-English versus later-English school. We also investigated whether teachers’ beliefs about pupils’ communicative development and Disadvantaged learning are related and whether this relation is moderated by teachers’ language proficiency, actual English teaching, or type of school they are teaching at.

The results of this study provide insight in how teachers’ assess their own English teaching skills, and how these relate to their beliefs about early-English education. This may in turn provide input for pre- and in-service training and support for teachers who are involved in (early-)English education.

Materials and method

Participants

Participants were 99 general classroom teachers, 10 (10.1%) were male and 89 (89.9%) female. This is representative for the ratio between male and female teachers in Dutch primary education. Teachers were responsible for teaching all subjects (thus not only English) to children. Approximately half of the teachers (n = 48; 48.5%) worked at an early-English school. On average, participants were 40.4 years old (SD = 12.6), and had 14.7 years of experience (SD = 11.8). 91.7% (n = 44) of early-English teachers used English in their classroom. That was the case for only 22 teachers (43.1%) working at later-English schools. contains the descriptive statistics for both groups. 14 additional participants filled in the questionnaire. These were primary-school directors that did not teach any classes. They were not included in our analyses.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for early- and later-English teachers

Teacher questionnaire

A questionnaire was constructed (Appendix 1), for the largest part based on a previously used questionnaire (Thijs et al. Citation2011a), and supplemented with new questions based on the literature review outlined in the introduction. The questionnaire consisted of three parts.

Background information

The first part contained seven questions in which teachers were asked about their gender, age, in which province their school was located, in which grade English lessons started at their school, their years of experience as a primary-school teacher, and whether they provided English lessons.

Beliefs related to early-English education

The second part consisted of 25 statements. Part of the statements concerned effects of early-English education such as ‘I think English lessons from kindergarten onwards increase pupils’ opportunities in the future’. Others concerned teachers’ skills, like ‘I think teaching in English is difficult’. It was emphasized that teachers should answer regardless of whether they provided English lessons themselves. Teachers could answer on 7-point scales, ranging from ‘(1) I completely disagree’ to ‘(7) I completely agree’.

Speaking proficiency

Teachers were asked to rate their speaking proficiency in English according to the six statements of the Common European Reference Framework, like ‘I can use simple phrases and sentences to describe where I live and people I know.’ (Council of Europe Citation2018). Statements were presented one-by-one in increasing order of difficulty, and teachers had to choose between the following three answers: ‘I am able to do this’, ‘I am not able to do this’, or ‘I do not know whether I am able to do this’. The highest-ranking statement of ability was taken as the teacher's self-rated level of English speaking proficiency. Speaking proficiency scores could thus range from 0 (not able to perform any of the reference statements, proficiency below A1-level) to 6 (able to perform the most difficult statement, proficiency at C2-level).

Procedure

The online questionnaire was designed using Qualtrics software, and spread via email amongst schools in all over the Netherlands. The questionnaire was also spread via social media. Teachers participated voluntarily. Participants were told that they were about to fill in a questionnaire about their beliefs on English lessons, and gave informed consent.

Results

Teachers’ beliefs regarding early-English education: three components

shows the mean score, standard deviation and range of scores for each of the 25 statements on teachers’ beliefs regarding early-English education. For every statement, the whole range of answer possibilities was used: some participants completely disagreed with a statement whereas others completely agreed with it. The highest mean score was obtained on ‘I think English is an important subject in primary school’ (M = 5.96). The lowest mean score (M = 2.64) was obtained on ‘I think differences between pupils are too large to provide English lessons from kindergarten onwards’.

A factor analysis with varimax rotation was conducted to examine whether teachers’ beliefs were related to different aspects of early-English education. Three components with an Eigenvalue greater than one were revealed. A scree plot confirmed the three-factor solution. Together, these factors explained 67.36% of the variance. The three factors could be related to the three components mentioned in the literature and thus implemented in our questionnaire. A loading needs to have a value of above .512 to be significant for a sample of about 100 (see Stevens Citation2002). In addition, a loading should be less than .400 to draw the conclusion not to interpret it (see Stevens Citation2002). Five items did not meet this criterion. They were not typical enough for only one of the factors and were not included in the analyses. Of the remaining 20 items, seven loaded on the first factor, labelled ‘Communicative scope’. This factor includes favourable developmental effects of early-English education for both pupils and teachers, in the near and far future. Six items loaded on the second factor, labelled as ‘Disadvantaged learning’. This factor is comprised of items describing potential negative effects of early-English education, particularly because of children having learning problems and differences in children's language background. The third factor, ‘Teaching skills’ comprises seven items that relate to the teacher's ability to use English during lessons, and the teacher's knowledge of pedagogical and didactical methods to teach English to young children. Cronbach's alpha coefficients were high, .919, .897, and .896, respectively. For each scale we computed an average score on the set of items loading on that scale. shows the descriptive statistics for the factors. Overall, teachers are positive about the effects on Communicative scope (M = 5.11, SD = 1.40) and about their own Teaching skills (M = 4.73, SD = 1.51), but they rejected Disadvantaged learning effects (M = 3.04, SD = 1.39).

Table 2. Factor Loadings on three factors of beliefs regarding Early-English Education. Factor loadings larger than .500 are in bold.

Teachers’ speaking proficiency

Teachers’ speaking proficiency in English varies widely. Five teachers (5.1% of all participants) say they are not proficient in English at all, whereas 36 (36.4%) teachers rate their proficiency as comparable to a native speaker's. Of the 64 teachers who actually teach English only 37 (57.8%) report having at least B2 proficiency in speaking English.

A division was made between teachers with a self-rated English speaking proficiency of B1 or lower (n = 46), and teachers with a self-rated speaking proficiency of at least B2 (n = 53), because B2 is the required level of English proficiency for providing English lessons. Furthermore, a division was made according to ‘teacher type’: teachers who provided English lessons (n = 66) and teachers who did not (n = 33). shows the final groups.

Table 3. Division of teachers according to Teacher Type, School Type, and Speaking proficiency.

School type, speaking proficiency, and teaching English as predictors of the beliefs

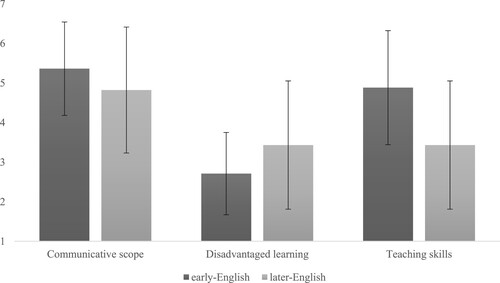

shows the mean scores on the three factors for teachers from early-English and later-English schools.

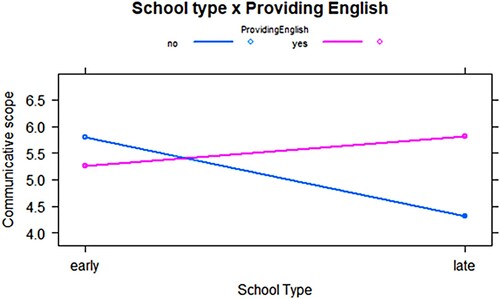

School Type, Speaking Proficiency, and Teacher Type were submitted to backwards regression analyses with ‘Communicative scope’, ‘Disadvantaged learning’ and ‘Teacher skills’ as the respective three factors or predictors. The full model contained all main, 2-way, and 3-way interaction effects. After running this model, non-significant effects were removed one by one, starting with the interaction effects. Model comparison was done to investigate which model was the most parsimonious one. The final model () for ‘Communicative scope’ shows that early-English teachers are more positive about the possible developmental effects than later-English teachers. Teachers with a self-rated English-speaking proficiency of B2 or higher, are more positive than teachers with a speaking proficiency of B1 or lower. Finally, there was a significant interaction effect between School Type and Teacher Type, showing that teachers working at an ‘English early’ school were rather positive about the developmental effects of early-English education, regardless of whether they provided English themselves, whereas for teachers working at later-English schools, those who provided English lessons were more positive than those who did not provide English lessons ().

Table 4. Backwards Regression Models for ‘Communicative scope’, ‘Disadvantaged learning’, ‘Teaching Skills’

For ‘Disadvantaged learning’ effects, the final model showed only significant main effects, both for Speaking Proficiency, and for Teacher Type. Teachers with a higher self-perceived speaking proficiency and teachers who provided English themselves had lower scores on the scale of ‘Disadvantaged learning’ than teachers with a lower self-perceived speaking proficiency and teachers who did not provide English themselves. For ‘Teaching skills’, finally, the final model also showed main effects of Speaking Proficiency and Providing English. Teachers who provided English themselves and teachers with higher self-rated speaking skills had higher scores on the factor ‘Teaching skills’ than teachers who did not provide English themselves and teachers who had lower self-rated English speaking skills.

The relation between Communicative scope and Disadvantaged learning

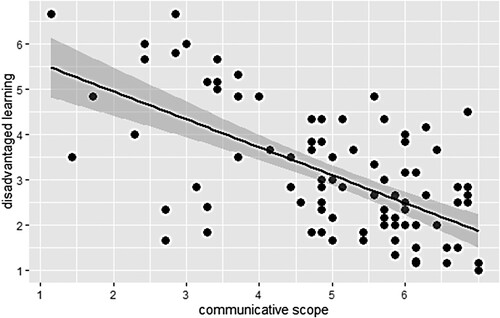

The correlation (r = −.613, p <.001) between Communicative scope and Disadvantaged learning is substantial. In general, teachers who have high scores on ‘Communicative scope’, have lower scores on ‘Disadvantaged learning effects’, but some teachers have relatively high or low scores on both components (see ). We examined whether the relation between beliefs about Communicative scope and Disadvantaged learning was moderated by School Type, Teacher Type, or Speaking Proficiency, but non-significant interaction effects between Disadvantaged learning and any of the predictors (p >.05) showed this was not the case.

Discussion and conclusion

In this study, we investigated primary-school teachers’ beliefs about early-English education, and their beliefs about their own English teaching skills and language proficiency. The aim was to investigate whether beliefs differed according to teachers’ professional backgrounds and self-rated English proficiency skills. The type of school (starting with English in the lower or higher grades) teachers worked at, whether they provided English themselves or not, and their self-rated speaking proficiency were all related to teachers’ beliefs.

The results partly confirmed our hypothesis that teachers from early-English schools would be more positive about the effects of early-English education on Communicative scope development, less negative about Disadvantaged learning effects, and more positive about their own teaching skills than teachers from later-English schools. Teachers from early-English schools indeed showed more positive beliefs about the effects of early-English education on Communicative scope than teachers from later-English schools. In addition, the ‘early’ group believed less in possible Disadvantaged learning effects than the later-English group. However, the two groups did not differ in their beliefs about their own English teaching skills. Our results corroborate with those of previous studies: while teachers are generally positive about early-English lessons, they also notice possible negative effects such as for the development of pupils’ L1 (Czura, Papaja, and Urbaniak Citation2009; Infante, Benvenuto, and Lastrucci Citation2009; Pena Diaz and Porto Requejo Citation2008; Thijs, Tuin, and Trimbos Citation2011b). This study adds to those studies by showing that variation in teachers’ beliefs is related to the school teachers work at. It may be the case that teachers who have more positive beliefs about early-English education deliberately chose to work at a school where this type of education is provided. Alternatively, teachers who work at an early-English school may gradually overcome their negative beliefs, because they do not encounter the possible negative side-effects of early-English education. In other words, teachers may thus initially hold beliefs that later on appear not to be true.

That the two groups of teachers did not differ in their beliefs about their English teaching skills, may have to do with the context in which this study was carried out. English is very present in everyday society in the Netherlands, and children are able to acquire some English before formal schooling starts (De Wilde, Brysbaert, and Eyckmans Citation2020; Kuppens Citation2010; Puimège and Peters Citation2019). In general, Dutch people have a relatively good command of English (EPI Citation2018). Therefore, both teachers from early-start and late-start schools may rate their English speaking skills at a relatively high, and comparable level. At least three of the six statements that measured beliefs about teaching skills directly asked about English proficiency. It may be that teachers’ beliefs about their skills actually reflected their beliefs about their language proficiency rather than their didactical skills for teaching English to young children.

We also investigated the relation between teachers’ self-rated English speaking skills and their beliefs. Teachers’ proficiency showed a positive relation with their beliefs about early-English education: teachers who rated their speaking proficiency at B2-level or higher, had more positive beliefs about their own English teaching skills and about the effects of early-English education on Communicative scope, and held less strong beliefs about the Disadvantaged learning effects of early-English education than teachers who rated their English speaking skills at B1-level or lower. These outcomes again confirm the outcomes of previous studies on teachers’ beliefs about the effects of early-English education, and of studies showing that teachers do not always believe their teaching skills for providing English to young children are at a sufficient level (Czura, Papaja, and Urbaniak Citation2009; Pena Diaz and Porto Requejo Citation2008; Thijs, Tuin, and Trimbos Citation2011b). This study also extends those previous results by showing that teachers’ beliefs are related to their perceptions about their proficiency level in English. Previous research already showed that teachers with a lower English proficiency level relied more on use of the L1 during English lessons, and lack the didactical skills to maximize pupils’ foreign language production (Enever Citation2014). Our study shows that teachers who have a lower English language proficiency, are aware of their lack of didactical skills and language skills for providing English education. It may be that teachers who rated their English proficiency at a lower level show less belief in the Communicative scope and more belief in the Disadvantaged learning effects of early-English education than teachers who rated their proficiency at a higher level, because teachers with a lower proficiency (unconsciously) adjust their beliefs about early-English education to their beliefs about their proficiency. This adjustment phenomenon, described in the cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger Citation1957; Harmon-Jones and Harmon-Jones Citation2007), can be explained by a discrepancy between beliefs – in this case, beliefs about skills necessary for early-English education and beliefs about the effects of early-English education. This misfit between beliefs leads to an unpleasant tension, that can be resolved by bringing beliefs in line with each other.

We chose to assess teachers’ English proficiency by means of self-ratings on CEFR-scales, to guarantee anonymity. The CEFR-scale was developed as a general measurement of language ability in second-language learners (Council of Europe Citation2018). Since classroom interaction with child second-language learners calls for the specific use of that language, it may be that these scales do not capture teachers’ English proficiency needed for teaching. Furthermore, teachers’ self-perceptions may not reflect their actual language level or their language proficiency as shown during class. Nevertheless, previous research that used both self-ratings and native-speaker assessments to investigate primary-school teachers’ proficiency concluded that correlations between the two measures were high and self-ratings were therefore likely to be reliable (Unsworth et al. Citation2015).

We also investigated differences in beliefs between teachers who provided English themselves and teachers who did not. We found that teachers who provide English lessons themselves, regardless of the type of school they worked at, are more positive about their English teaching skills than teachers who do not provide such lessons. It may be that teachers deliberately chose to provide English since their English proficiency is at a level at which they feel comfortable to provide those lessons. Alternatively, they did not opt for it voluntarily (e.g. because it is just part of the job), but were provided with in-service training on how to provide English lessons. Finally, it is possible that teachers ‘learn by doing’: the longer teachers provide English lessons, the more skilled teachers may become (Dewaele Citation2020). Their proficiency and didactical experience might grow over the years.

Finally, it appeared that teachers who held more positive beliefs about the effects of early-English education on Communicative scope, held less negative beliefs about Disadvantaged learning. We investigated whether this relation was moderated by school type (early-English or later-English), teacher type, or teachers’ proficiency. This appeared not to be the case. It thus seems that beliefs about the positive effects of early-English education (in this case Communicative scope) generally do not so much exist next to beliefs about probable negative effects (here: Disadvantaged learning), but stand in relation to each other. Due to the nature of the study, causal relations between teachers’ experiences and proficiency and their beliefs cannot be drawn. Previous research suggests that teachers who have more experience with including pupils with special educational needs in the English classroom, have more positive beliefs about including such pupils (Nijakowska, Tsagari, and Spanoudis Citation2018; Porsch and Wilden Citation2021). This suggests that more experience with a certain situation may lead to more positive attitudes. From our study, it is unclear whether teachers deliberately chose to work at a certain type of school, or whether teachers’ beliefs changed when they had more experience with a certain type of education. Moreover, the small groups prevent us from drawing firm conclusions. A longitudinal study with larger groups would allow for investigating the relations found in this study more thoroughly.

The fact that we used a questionnaire to investigate beliefs, may have had the result that we were capable to capture only rather explicit beliefs, and that teachers may have responded in a socially desirable way (Borg Citation2001). Furthermore, the questionnaire we constructed was not formally validated, and therefore we cannot finally ascertain that it really measured the intended constructs. However, the questionnaire was based on a previously used questionnaire and covered all relevant topics mentioned in the literature. Reassuringly, our findings were consistent with previous findings with Dutch teachers (Thijs et al. Citation2011a).

This study shows that teachers’ beliefs about early-English education differ along teachers’ experiences with English education and their English proficiency. At least part of the Dutch primary-school teachers feels not sufficiently prepared to teach English, and have relatively negative beliefs about the effects of early-English education. Almost half of the participating teachers rated their own English speaking skills at a level lower than the required B2-level, and more than 50% of these teachers provided English lessons themselves. Regardless of whether it is the cause or the consequence of their low English proficiency level, it seems that especially those teachers tend to have more negative beliefs about the effects of early-English education, even if research has failed to provide evidence for such negative effects. So far, research has, for example, not found any negative effects of providing bilingual pupils with English lessons. Yet, teachers’ responses on such statements (e.g. ‘early-English lessons are rather detrimental than beneficial to pupils who speak another non-European language at home’) varied greatly: some teachers showed a clear belief that this statement was true, others showed a clear disbelief.

Previous research already acknowledged the lack of pre- and in-service training on teaching English to young learners (Jenniskens et al. Citation2020; Pérez-Cañado Citation2012; Thijs, Tuin, and Trimbos Citation2011b). This gap in teacher education may account for the fact that part of the teachers seem to feel ill-prepared to provide English. Our study shows that there is need for specific training and support for teachers on English education. Such training should not only be aimed at enhancing teachers’ English language skills and didactical skills, but also on providing teachers with knowledge on the goal and expected effects of (early-)English education.

In summary, this study shows that primary-school teachers vary in their beliefs about the effects of early-English education, as well as in the extent to which they believe they meet the requirements to provide English. These beliefs do not stand on their own, but are related to teachers’ professional background and their perceptions about their English proficiency.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Claire Goriot

Claire Goriot worked as a postdoc researcher at the Centre for Language Studies of Radboud University Nijmegen, Nijmegen. Her research focuses on educational processes, foreign language learning, and child bilingualism. Currently, she works at a teacher training institute for primary-school teachers, where she carries out research on various topics, including interaction processes in education, the use of wordless picture books, and CLIL.

Roeland van Hout

Roeland van Hout is an emeritus professor of Applied and Variational Linguistics at the Center for Language Studies of Radboud University Nijmegen. His work focuses on language variation and change and second language acquisition, from an interdisciplinary perspective (sociology, linguistics, psychology). He also publishes the application of statistics in language research.

References

- Borg, M. 2001. “Teachers’ Beliefs.” ELT Journal 55 (2): 186–187.

- Council of Europe. 2018. Global Scale – Table-1 (CEFR 3.3): Common Reference Levels. https://www.coe.int/en/web/common-european-framework-reference-languages/table-1-cefr-3.3-common-reference-levels-global-scale.

- Czura, A., K. Papaja, and M. Urbaniak. 2009. “Bilingual Education and the Emergence of CLIL in Poland.” CLIL Practice: Perspectives from the Field 172: 178.

- De Graaff, R., and O. Costache. 2020. “Current Developments in Bilingual Primary Education in the Netherlands.” In Child Bilingualism and Second Language Learning: Multidisciplinary Perspectives, edited by F. Li, K. E. Pollock, and R. Gibb, 137–165. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN: 9789027207999.

- Dewaele, J.M. (2020) What Psychological, Linguistic and Sociobiographical Variables Power EFL/ESL Teachers’ Motivation? In The Emotional Rollercoaster of Language Teaching, edited by C. Gkonou, J. M. Dewaele, and J. King, 269–287. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters. ISBN 9781788928342.

- De Wilde, V., M. Brysbaert, and J. Eyckmans. 2020. “Learning English Through out-of-School Exposure. Which Levels of Language Proficiency are Attained and Which Types of Input are Important?” Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 23 (1): 171–185. doi:10.1017/S1366728918001062.

- Dutch Inspectorate of Education. 2019. Peil.Engels Einde basisonderwijs 2017-2018 [Level.English End of primary education 2017-2018]. Dutch Inspectorate of Education.

- Enever, J. 2014. “Primary English Teacher Education in Europe.” ELT Journal 68: 231–242. doi:10.1093/elt/cct079.

- Enever, J., E. Krikhaar, E. Lindgren, L. Lopriore, G. Lundberg, J. Mihaljevic Djigunovic, C. Munoz, M. Szpotowicz, and E. Tragant Mestres. 2011. ELLiE: Early Language Learning in Europe. Edited by J. Enever. United Kingdom: British Council.

- EPI, E. 2018. English Proficiency Index. https://www.ef.com/wwen/epi/.

- Fang, Z. 2006. “A Review of Research on Teacher Beliefs and Practices.” Educational Research 38 (1): 47–65. doi:10.1080/0013188960380104.

- Festinger, L. 1957. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Gao, Y. 2014. “Language Teacher Beliefs and Practices: A Historical Review.” Journal of English as an International Language 9 (2): 40–56.

- Goriot, C., M. Broersma, J. M. McQueen, S. Unsworth, and R. van Hout. 2018. “Language Balance and Switching Ability in Children Acquiring English as a Second Language.” Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 173: 168–186. doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2018.03.019.

- Goriot, C., J. M. McQueen, S. Unsworth, R. van Hout, M. Broersma, and S. Sulpizio. 2020. “Perception of English Phonetic Contrasts by Dutch Children: How Bilingual are Early-English Learners?” PLOS ONE 15 (3): e0229902. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0229902.

- Harmon-Jones, E., and C. Harmon-Jones. 2007. “Cognitive Dissonance Theory After 50 Years of Development.” Zeitschrift Für Sozialpsychologie 38 (1): 7–16. doi:10.1024/0044-3514.38.1.7.

- Infante, D., G. Benvenuto, and E. Lastrucci. 2009. “The Effects of CLIL from the Perspective of Experienced Teachers.” In CLIL Practice: Perspectives from the Field, edited by D. Marsh, P. Mehisto, D. Wolff, T. Aliage, T. Asikainen, and M. J. Frigols-Martin, 156–163. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä.

- Jenniskens, T., B. Leest, M. Wolbers, M. Bruggink, C. Dood, and E. Krikhaar. 2017. Zicht op vroeg vreemdetalenonderwijs [Insight into Early Foreign Language Education]. Nijmegen, the Netherlands: KBA Nijmegen.

- Jenniskens, T., B. Leest, M. Wolbers, M. Bruggink, E. Krikhaar, R. de Graaff, S. Spätgens, and S. Unsworth. 2020. Evaluatie pilot Tweetalig Primair Onderwijs. Vervolgmeting schooljaar 2018/2019 [Evaluation Pilot Bilingual Primary Education. Follow-up Measurement Schoolyear 2018/2019]. the Netherlands, Nijmegen: KBA Nijmegen.

- Kuppens, A. H. 2010. “Incidental Foreign Language Acquisition from Media Exposure.” Learning, Media and Technology 35: 65–85. doi:10.1080/17439880903561876.

- Nijakowska, J., D. Tsagari, and G. Spanoudis. 2018. “English as a Foreign Language Teacher Training Needs and Perceived Preparedness to Include Dyslexic Learners: The Case of Greece, Cyprus, and Poland.” Dyslexia 24 (4): 357–379. doi:10.1002/dys.1598.

- Nikolov, M., and J. M. Djigunovic. 2011. “All Shades of Every Color: An Overview of Early Teaching and Learning of Foreign Languages.” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 31: 95–119.

- Nuffic. 2017. Locaties vvto-scholen [Locations Early Foreign Language Schools]. https://www.nuffic.nl/primair-onderwijs/talenonderwijs/vroeg-vreemdetalenonderwijs-vvto/locaties-vvto-scholen.

- Nuffic. 2020. Tweetalig primair onderwijs (tpo) [Bilingual Primary Education (bpe)]. https://www.nuffic.nl/onderwerpen/tweetalig-primair-onderwijs/tweetalig-primair-onderwijs-tpo.

- Nuffic. n.d. Standaard vroeg vreemdetalenonderwijs Engels [Standard Early Foreign Language Education English]. Accessed 15 September 2022. https://www.nuffic.nl/sites/default/files/2020-08/standaard-vroeg-vreemdetalenonderwijs-engels.pdf

- Pena Diaz, C., and M. D. Porto Requejo. 2008. “Teacher Beliefs in a CLIL Education Project.” Porta Linguarum 10: 151–161.

- Pérez-Cañado, M. L. 2012. “CLIL Research in Europe: Past, Present, and Future.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 15: 315–341. doi:10.1080/13670050.2011.630064.

- Porsch, R., and E. Wilden. 2021. “Teaching English in the Inclusive Primary Classroom: An Additional Professional Challenge for Out-of-Field Teachers?” European Journal of Applied Linguistics and TEFL 10 (2): 201–220.

- Puimège, E., and E. Peters. 2019. “Learners’ English Vocabulary Knowledge Prior to Formal Instruction: The Role of Learner-Related and Word-Related Variables.” Language Learning 69 (4): 943–977. doi:10.1111/lang.12364.

- Shin, J. Y., L. Q. Dixon, and Y. Choi. 2020. “An Updated Review on use of L1 in Foreign Language Classrooms.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 41 (5): 406–419. doi:10.1080/01434632.2019.1684928.

- Stevens, J. 2002. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences. 4th ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Thijs, A., B. Trimbos, D. Tuin, M. Bodde, and R. de Graaff. 2011a. Engels in het basisonderwijs [English in Primary Education]. Enschede, the Netherlands: SLO (nationaal expertisecentrum leerplanontwikkeling) [National Expertise Centre Learning Plan Development].

- Thijs, A., D. Tuin, and B. Trimbos. 2011b. Engels in het basisonderwijs: verkenning van de stand van zaken [English in Primary Education: An Exploration of the Current Situation]. Enschede, the Netherlands: SLO (nationaal expertisecentrum leerplanontwikkeling) [National Expertise Centre Learning Plan Development].

- Unsworth, S., L. Persson, T. Prins, and K. de Bot. 2015. “An Investigation of Factors Affecting Early Foreign Language Learning in the Netherlands.” Applied Linguistics 36: 527–548. doi:10.1093/applin/amt052.

- Vähäsantanen, K. 2015. “Professional Agency in the Stream of Change: Understanding Educational Change and Teachers’ Professional Identities.” Teaching and Teacher Education 47: 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2014.11.006.

Appendix 1. Questionnaire

Background information

The following questions relate to your personal characteristics. We only use your answers as background information.

1. What is your age?______________________________________________

2. What is your gender? Female/male/other

3. What is your function? (multiple answers possible)

□ Generalist classroom teacher

□ Native speaker specialist teacher

□ Internal supervisor (for educational and behavioural remediation)

□ Director

□ Other, namely _________________________________________

4. Do you teach in the lower grades, the upper grades, or both? Lower/upper/both

5. How many years have you been working in primary education?_________

6. In which grade do English lessons start at your schools? _______________

7. Do you teach English yourself in your class? Yes/no

8. In which province is your school located?_ __________________________

English in primary school

Regardless of whether you provide English lessons, please indicate to what extent you agree with the following statements. For each statement, you can choose one answer.

26. How do you rate your own speaking proficiency in English? For the following statements, please indicate whether you are or are not able to perform that statement. The statements are placed in increasing order of difficulty.

Appendix 2. Descriptive statistics for 25 statements on early-English education in the questionnaire.

*Numbers refer to the numbers in .