ABSTRACT

We study gender differences in the selection of traditional universities versus universities of applied sciences in Germany. Do women, due to life and job goals, less often enrol than men in traditional universities and more often enrol at the more practice- and profession-oriented universities of applied sciences? Or are women overrepresented at traditional universities due to prior educational choices and outcomes such as higher school grades and more frequent choice of non-technical fields of study? Our analyses on a national sample of 1st-year students report a 14-percentage point higher likelihood of women than men to enter traditional universities. This gender gap can almost entirely be attributed to educational factors, specifically women’s less frequent choice of engineering majors, and hardly by job goal preferences. That, net of these factors, no gender difference exists indicates that women in Germany do not aim lower or higher than men as to the institution choice.

Introduction

Worldwide, the position of women vis-à-vis men on the educational ladder has changed dramatically. In the 1990s, women were, on average, lower educated than men in most countries of the world. Due to a strong rise in educational level, women nowadays surpass men in average educational attainment in virtually all industrialised countries (DiPrete & Buchmann, Citation2013; Schofer & Meyer, Citation2005) and many non-Western countries (Esteve et al., Citation2012). Yet, there still exists vertical gender segregation in education. Women tend to be underrepresented at the top of the educational distribution, for example, in post-graduate education (UNESCO International Institute for Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean, Citation2021). In our country of focus, Germany, vertical gender segregation also exists at a lower educational level as to higher education enrolment. While women outnumber men in upper secondary education, more frequently attain a qualification for entry into higher education, and obtain higher overall exam grades (Destatis, Citation2021a; Helbig, Citation2010; Lörz et al., Citation2011), there currently only exists parity in the number of men and women in higher tertiary education (Destatis, Citation2021c). German women, therefore, have lower chances than men to enter higher education and relatively more often enter the lower ranked postsecondary vocational training (Hecken, Citation2006; Heine et al., Citation2007; Lörz et al., Citation2011). This pattern seems to differ from most other industrialised countries, where women outnumber men in higher education (Stoet & Geary, Citation2020).Footnote1

Whether women in Germany also “aim lower” than men regarding the type of higher education institution is unknown. In Germany, the two main types of higher tertiary education are traditional university and university of applied sciences. Traditional universities comprise general universities (Universität), technical universities (Technische Universität), and colleges of education (Pädagogische Hochschule). Universities of applied sciences comprise professional colleges (Fachhochschulen) and colleges for applied science (Hochschulen für angewandte Wissenschaften).Footnote2 Traditional universities offer a wide variety of majors, and their programmes are more theory oriented. Universities of applied sciences (Fachhochschulen; FH) provide a more limited number of majors – primarily in engineering, business studies, and social work – and its programmes are more practice oriented and more adapted to the requirements of professional life. While de jure no difference exists in the status of a bachelor’s or master’s degree of the two types of higher education and all programmes at both institutions are open to secondary school leavers with a general qualification to enter higher education (allgemeine Hochschulreife), de facto inequalities arise from the institution choice.Footnote3 University graduates, on average, acquire higher paid jobs and higher lifetime earnings than students graduating from FH (Piopiunik et al., Citation2017; Schmillen & Stüber, Citation2014).Footnote4 The jobs of university graduates also enjoy higher social status than the jobs of FH students (e.g., a social scientist has higher social prestige than a social worker; cf. Treiman, Citation1977). Since gender differences in the choice of the two types of higher education can be a source of further gender segregation, these differences are important to study.

Our study fills in an apparent research gap. Using data from a nationally representative sample of 1st-year students from the National Educational Panel Study (NEPS), this study assesses for the first time for Germany gender differences in the enrolment of higher education institutions (traditional university or university of applied sciences). Prior research for Germany focused on the gender gap in higher education enrolment (Hecken, Citation2006; Heine et al., Citation2007; Lörz et al., Citation2011) and tertiary study field choice (Hägglund & Lörz, Citation2020; Heine et al., Citation2006; Lörz et al., Citation2011; Uunk et al., Citation2019) but did not inspect the gender gap in institution choice.Footnote5 For other countries, the gender gap in the institution choice is not well documented either, so that our study findings are also relevant for a broader context. In addition to describing the gender difference in institution choice, we try to account for the potential gender difference in institution choice. Using a path dependency and a life goal perspective, we assess the role of earlier educational decisions and outcomes (vocational school attendance, secondary-school grades, and study field choices) and of life and job goal preferences for gendered institution choices. These perspectives have also been used to explain gender differences in higher education enrolment and study field choices (Hägglund & Lörz, Citation2020; Lörz et al., Citation2011), though with weaker success for the life goal perspective, and are thus put to a new test.

Theoretical perspectives and hypotheses

Will men or women have higher odds of entering traditional university? We derive hypotheses from two theoretical perspectives.

The first theoretical perspective is a retrospective one and stresses path dependency, specifically the role of earlier school decisions and outcomes for further educational choices (Hägglund & Lörz, Citation2020; Lörz et al., Citation2011).Footnote6 Earlier school decisions and outcomes restrict the set of available higher education options. In part, this point is evident as students who did not qualify for higher education may not enter higher education. But also, among those who are eligible for higher education, particular school decisions and outcomes may affect the institution choice. First, students who qualified for higher education via upper secondary vocational school (Berufliche Schule) may less often enrol at traditional university and more often enrol at FH than children who qualified via the standard Gymnasium route. The majors at traditional universities match less well with their more practice-oriented educational profile.Footnote7 Second, study field choices – which are already being made in secondary school and ultimately upon tertiary education enrolment – may affect the choice of institution. Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) majors – especially engineering studies – are more often found at FH and less often at traditional universities than non-STEM majors, such as humanities and social sciences (see also findings below). Therefore, study field choices restrict the set of available higher education options (cf. Lörz et al., Citation2011).Footnote8 Third, the school performance of students qualifying for higher education may affect the institution choice. For Germany, however, the argument for such a performance effect is not so much about restrictions. There are no grade or test requirements for higher education enrolment except that the overall exam grade needs to be sufficient. Instead, the performance effect may lie in investment and probability considerations. Higher overall secondary school performance – here assessed with the overall exam grade – raises the likelihood of choosing traditional university over FH since one can expect students to want to reap their invested performance effort (as in human capital theory; cf. Becker, Citation1993). Furthermore, higher grades raise the expected probability of study success in high-ranked educational tracks. They give students more confidence to be successful at the academically more challenging programmes at traditional universities (as in rational choice models of educational choices; cf. Erikson & Jonsson, Citation1996; Jonsson, Citation1999; and as in expectancy-value theory; Eccles, Citation2009).

From the path-dependency perspective, one can expect that in Germany women have higher odds than men to enter traditional university rather than FH (Hypothesis [H] 1). First, women less often attend upper secondary vocational school than men (Lörz et al., Citation2011; also see findings below). Second, women in Germany, just as elsewhere, less often choose STEM fields of study than men (cf. Hägglund & Lörz, Citation2020; Heine et al., Citation2006; Lörz et al., Citation2011; Uunk et al., Citation2019). Third, in the most important track sorting into higher education in Germany, the Gymnasium, women receive higher school and graduation grades than men (Helbig, Citation2013). Higher grades may make women more confident to succeed at traditional university than men (Jonsson, Citation1999). This may hold despite a generally somewhat weaker self-assessed competence of women (cf. Correll, Citation2001; Weinhardt, Citation2017).

The second theoretical perspective is a prospective one and stresses the importance of future-oriented life and job goals for current educational choices. The perspective is often used to explain men’s and women’s educational and occupational choices. Due to gendered socialisation, women would acquire distinct life goals regarding family and career and favour family over career more than men (Ceci & Williams, Citation2010; Charles & Bradley, Citation2009; Hakim, Citation2002). Women would therefore be less in need of being educated within the highest educational ranks than men. As to the institution choice in Germany, this implies that women have lower odds than men to enter traditional university rather than FH (H2). The more demanding educational and occupational pathways of and after university may less well be combined with family life (cf. Lörz et al., Citation2011). Also, women’s presumed lower preference for a job with good earnings (Bobbitt-Zeher, Citation2007) implies that women derive less benefit from choosing the generally higher paid university route than men. Programmes at FH, on the other hand, will, according to this perspective, be a more attractive option for women. The less demanding professions resulting from FH can generally better be combined with family life. This is also because FH majors are stronger tied to the exercise of a particular profession (Beruf) than academic majors, reducing uncertainty in job tenure, working hours, leave arrangements, and wage.

We want to stress that, although the two perspectives state different determinants and lead to competing hypotheses on gender and institution choice, the perspectives are not unrelated (cf. Hägglund & Lörz, Citation2020). First, the determinants of the two perspectives covary. Life and job goal preferences affect school performance, school choices, and study field choices (Ceci & Williams, Citation2010), although the effect of life and job goal preferences on study field choices is empirically weak (Lörz et al., Citation2011; Mann & DiPrete, Citation2013). Therefore, the distinct determinants of the institution choice need to be assessed simultaneously. Second, the relevant gender differences in both perspectives – gender differences in school choices, study field choices, grades, and life and job goals – likely originate from the same source. Gendered norms and socialisation contribute to gender differences in grades (Spelke, Citation2005), study field choices (Charles & Bradley, Citation2009), school choices, and life goals (Charles, Citation2017). This implies that the gendered context may affect men’s and women’s higher education choices in opposing ways. On the one hand, the gendered context causes women to have a school grade advantage (e.g., via expectations on self-discipline; cf. Duckworth & Seligman, Citation2006) and a more frequent choice for non-STEM fields (e.g., via comparative advantages in language; cf. Breda & Napp, Citation2019). This may steer women to traditional university more than men. On the other hand, the gendered context causes women to have less career-oriented life and job goals, with the consequence that women less often choose traditional university than men. What the empirical outcome is, higher or lower odds of women than men to enter traditional university, will be sorted out below.

Data, measures, method

Data

To test our hypotheses, we use data from the NEPS Starting Cohort First Year Students (https://doi.org/10.5157/NEPS:SC5:14.0.0; H.-P. Blossfeld & Roßbach, Citation2019). The NEPS is a longitudinal study on educational trajectories in Germany following a multi-cohort sequence design.Footnote9

Starting Cohort First Year Students is a nationally representative panel study of 1st-year undergraduate university students and students of universities of applied sciences who began with their first major in the winter semester of the academic year 2010–2011 and have been interviewed from 2010 up to 2018 (14 waves). Since we are interested in gender differences in the entry of higher education institutions, we use data from the first wave 2010–2011, so our approach is cross-sectional. The study used stratified cluster sampling with a degree programme at a certain college as the cluster and stratification by type of institution to oversample teaching tracks and private universities (Aßmann et al., Citation2011). We apply cross-section weights provided by the NEPS to take account of this sampling design, in specific to correct for the oversampling of teacher educations. Our final sample of analysis comprises 11,896 higher education students, aged 17–25. Due to a post hoc match of job goal preference measures from Wave 3, 24% of the students in the original sample were dropped. This does not affect the prime finding on the gender difference in institution choice and the explanation of this difference by determinants other than job goals (cf. Online Appendix, Tables A2–A3). Less than 3% of cases were dropped because of unknown major choices, grades, or job goal preferences.

Measures

We analyse the dependent variable “traditional university enrolment”, where enrolment in a traditional university is coded as 1 and enrolment in a university of applied sciences is coded as 0. As stated above, we focus on the first (full-time) major chosen in the first academic year.

Central, independent, explanatory variables included in the analyses are:

Gender, where women are coded as 1 and men as 0.

Attendance of an upper secondary vocational school (Berufliche Schule), where attendance is coded as 1 and non-attendance as 0.

Exam grade. Respondents were asked to report their overall grades on their graduation certificates from secondary school. Grades were initially coded in the German scale system from 1 (very good) to 6 (unsatisfactory). Since we analyse students who qualified for higher education, grades higher than 4.0 are not present. For ease of interpretation, we reverse coded grades, where 1 is the worst and 6 the best grade.

Study field orientation. We use the grouping of study majors into 10 fields of study applied by the German statistical office (Destatis). The survey question was what the first subject respondent enrolled for (for students of teaching education: the first teaching subject enrolled for). To have groups that are large enough for analyses (i.e., that are both well enough presented at university and FH), we recoded the grouping into five study fields: (1) “Humanities and arts”; (2) “Social sciences, business, and law”; (3) “Science, math, and computing”; (4) “Health, medicine, and welfare”; (5) “Engineering and manufacturing”.

Job goals. Our data do not contain retrospective or current measures of women’s and men’s life and job goal preferences. Only, in the third wave, a full year after the first wave, questions on job goal preferences were addressed. Students reported whether they found “good remuneration”, “good career chances”, “pleasant working hours”, and “high job security” important (6-point Likert scales, with 1 coded as very unimportant and 6 as very important). We matched these responses post hoc to our data from the first wave (cf. Ochsenfeld, Citation2016). Although a post hoc measure is not ideal, life and job goal preferences are fairly stable from college to midlife (Atherton et al., Citation2021). As an alternative, we considered using data from the NEPS Starting Cohort Grade 9 study. The Grade 9 study comprises a longitudinally followed sample of secondary school students in Grade 9 and includes job and life goal preferences measured before higher education. However, we could not reproduce the gender difference in institution choice we observed with the larger and more representative First Year Students data.Footnote10 Robustness analyses showed a similarly signed (negative) but not significant effect of the job goal “to earn a lot” on the choice of traditional university versus university of applied sciences using the Grade 9 data (Online Appendix, Table A4).

Control variables included in the analyses are age at study entry and parental education. Parental education is the mean of respondent’s parents’ highest school-leaving qualification, measured with the 9-category CASMIN (Comparative Analysis of Social Mobility in Industrial Nations) classification of education (ranging from 1 = no diploma to 9 = university diploma). These variables are relevant to control since they may affect the institution choice (e.g., children from higher educated parents may more often opt for university than other children; P. N. Blossfeld et al., Citation2015; Lörz, Citation2017) and since there may exist gender differences in the distribution of these variables.

lists descriptive statistics of the (independent) variables by gender. We observe that female students at higher education institutions in Germany less often attended vocational school than male students and have obtained better (here coded as higher) overall exam grades at secondary school. The gender difference in exam grades is substantial.Footnote11 As a percentage of the total standard deviation in exam grades (0.64; not shown in table), the male–female difference amounts to (0.20/0.64 * 100% =) 31%. Furthermore, male and female students strongly differ in the choice of the study field, as was observed in prior research (Hägglund & Lörz, Citation2020; Heine et al., Citation2006; Lörz et al., Citation2011; Uunk et al., Citation2019). Female students less often enter STEM fields of study (notably engineering studies; 27 percentage points less) and more often enter non-STEM fields of study (notably humanities and arts; 22 percentage points more). Female students also attach less value to a good remuneration and good career chances than male students and attach greater value to pleasant working hours and high job security. However, the gender differences in these job goal preferences are not as large as for the educational factors, at maximum 21% of a standard deviation (good career chances). Female students are also slightly younger than male students but do not differ in their parental educational level.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of variables by gender.

Method

We use logistic regression models to assess the gender difference in the choice of traditional university over FH and use Fairlie non-linear decomposition to estimate to what extent gender differences in the institution choice can be attributed to background characteristics. The latter method is an extension of the Blinder–Oaxaca decomposition technique for linear dependent variables that is widely used to identify and quantify the separate contributions of group differences in measurable characteristics, such as education, experience, marital status, and geographical differences to racial and gender gaps in outcomes (Fairlie, Citation1999, Citation2005). The Fairlie decomposition method is tailored explicitly for binary outcome variables and obtains its estimates from logit models. It decomposes a difference in outcome between two groups in a part of the (gender) gap that is due to group differences in distributions of independent variables (“endowment part”), and a portion of the (gender) gap due to group differences in unmeasurable or unobserved endowments (“unexplained part”). In other words, with the technique, we can assess to what extent a (potential) gender gap in institution choice is due to gender differences in exam grades, study field choices, job goals, and other background characteristics. For more detailed information and a mathematical specification of the models, we refer to Fairlie (Citation2005) and for model estimation to Jann (Citation2006). Our decomposition analyses use the coefficient estimates from a logistic model pooled for men and women.

Findings

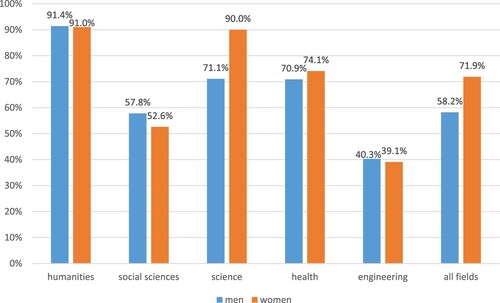

Do women in Germany more often enrol in traditional universities than men (H1) or less frequently (H2)? Our analyses on the NEPS Starting Cohort First Year Students data report a 14 percentage point higher likelihood of women to enter traditional university than men when enrolling in higher education (share is 72% for women and 58% for men; cf. ). This finding is in line with H1 and contrasts H2. The gender difference is statistically significant, as reported in logistic regression Model 1 of . The logit estimate of 0.608 means that women have an (exp[0.633] =) 1.8 higher odds to enter traditional university rather than FH than men (odds of women is 2.55; men 1.40). When we control for age at study entry and parental education, the gender difference decreases somewhat (Model 2, ). Yet, the gender effect is still significant and substantial (an 11 percentage point difference in traditional university enrolment in favour of women).

Table 2. Logistic regressions of the likelihood to enter traditional university rather than university of applied sciences.

Decomposition analyses in display that the initial gender difference in institution choice – a 14 percentage point greater likelihood of women to enter traditional university – can almost entirely be explained by the educational factors vocational school (explained gap is 11%), study field choice (69%), and exam grades (by 10%). These three factors account for 90% of the gender gap in institution choice. The lower share of women in engineering studies can particularly account for women’s higher odds of entering traditional university (by 89%). On the other hand, women’s higher share in “social sciences, business, and law” suppresses the gender effect (by 15%). If women had chosen this field as often as men, women would go even more to traditional university than they currently do. Men’s and women’s job goals, in contrast, hardly account for the gender gap in institution choice (5% in total). Only the goals “good remuneration” and “good career chances” can explain some of the gender gap; yet, note that it was expected that job goal factors would suppress the gender effect rather than reduce it. The control variables age and parental education explain an additional 10% of the gender difference in institution choice, with a larger role for age. In total, the included background characteristics can fully explain the initial gender difference in the institution choice.

Table 3. Percentage of the gender difference in the choice for traditional university versus university of applied sciences explained by background characteristics (Fairlie decomposition).

The logistic regression models underlying the decomposition analyses show that the gender effect on the likelihood of choosing traditional university becomes statistically non-significant when including all covariates (Model 5, ). This change in the gender effect is primarily due to the inclusion of the study field (Model 3). Vocational school attendance and exam grades change the gender effect much less (Model 4), and job goal measures do not change the effect at all (Model 5). Thus, when men and women choose similar study fields, no gender difference in the choice of higher education institution can be observed. This finding again rejects H2 from the life goal perspective. Women do not “aim lower” than men as to the choice of higher education institution at similar study field preferences.

The importance of study field choice for the gender difference in institution choice is illustrated in . The figure plots the observed shares of male and female higher education students choosing traditional university by field of study. While women opt more often for traditional university across all fields than men (a 14 percentage point difference), within most study fields, gender differences in the choice of traditional university are smaller (not larger than a 5 percentage point difference). The exception is the study field of “science, math, and computing”, where women have a 19 percentage point greater likelihood to enter traditional university than men. This exception is not due to gender selectivity of teaching educations in math (robustness analyses without students of teaching educations showed a similar gender difference; cf. Online Appendix, Table A5). Instead, the exception may be due to the distribution of specific majors within the field of “science, math, and computing”. Information Technology (IT) majors, for example, are more often found at FH than traditional university and are traditionally favoured by men.

Figure 1. Share of female and male higher education students choosing traditional university by field of study (observed percentages).

furthermore displays that the effects of the included background characteristics are generally as expected (Model 5). A higher age reduces the odds to enter traditional university, higher parental education increases the odds (cf. P. N. Blossfeld et al., Citation2015), vocational school attendance reduces the odds (cf. Lörz et al., Citation2012), and a higher overall exam grade increases the odds. In addition, compared to the reference group of humanities and arts, enrolling in another study field lowers the odds of entering a traditional university. This especially holds for the fields of social sciences and of engineering (also see ). The effects of the distinguished job goal measures are not in line with our expectations: Attaching more importance to good remuneration and career chances lowers the odds to enter traditional university, and high job security does not affect these odds. Only the importance of agreeable working hours is in the predicted direction (negative effect). Robustness analyses indicated that the above findings do not obscure gender differences in covariate effects, except for a somewhat smaller effect of vocational school attendance, exam grades, and the science/math field for women (Online Appendix, Table A6). Additional analyses using standardised scores also indicated that the effects of the educational factors vocational school attendance, exam grades, and study field on the odds of traditional university entry are much larger than the effects of the job goal measures (Online Appendix, Table A7).

Conclusions and discussion

Even though women have surpassed men in average educational attainment in virtually all advanced industrial countries, vertical gender segregation in education continues to exist. Prior studies observed that women are underrepresented in higher education in Germany relative to women’s share in upper secondary education (Hecken, Citation2006; Heine et al., Citation2007; Lörz et al., Citation2011). Our study finds that the gender difference reverses to the advantage of women within higher education. In the academic year 2010–2011, German women who enrol in higher education have a 14 percentage point higher likelihood (or 1.8 higher odds) than men to choose traditional university rather than university of applied sciences. Gender differences in the institution choice were not known for Germany and are neither well known for other countries but are a potential source of increased or reduced gender segregation.

The female overrepresentation at traditional universities cannot be explained from a gendered life and job goal perspective. From this perspective, one expects women to “aim lower”: to opt for a traditional university less often than men. The reasons are that women would find a successful career less important and a good work–life combination more important than men. Such preferences can presumably better be realised at FH than at a traditional university. Our findings reject that expectation – women are over-, not underrepresented at traditional university – and show that job goal preferences hardly account for the observed gender gap. Although women attach less value to a good remuneration and career chances than men and greater value to pleasant working hours and job security, these differences are not large, and the job goal measures hardly affect the institution choice. Men and women who attach greater value to good remuneration and career chances even less often opt for traditional university than other persons, despite the average wage premium of choosing a traditional university route. Lörz et al. (Citation2011) neither found that job and life goal measures could account for women’s lower chances of entering higher education in Germany. The same was found by Hägglund and Lörz (Citation2020), analysing the female underrepresentation in STEM majors in Germany (cf. Mann & DiPrete, Citation2013, for the US).

The female overrepresentation at traditional universities can much better be explained from a path-dependency perspective. This perspective stresses the role of earlier school decisions and outcomes (vocational school attendance, school performance, and study field choices) for higher education choices. The specific educational factors can explain women’s overrepresentation at traditional universities almost entirely. Women in Germany choose traditional university more often than men because women attend vocational school less often, because women obtain higher overall exam results, and above all because women choose non-STEM fields of study more often than men. Choice of study field is so important because it determines, through the distribution of majors across institutions, the set of higher education alternatives.

The higher odds of women than men of entering traditional university rather than FH, which are primarily caused by a more frequent choice of women for non-STEM fields of study, may give women a slight wage advantage in their occupational career (Piopiunik et al., Citation2017; Schmillen & Stüber, Citation2014). However, this wage advantage of higher traditional university enrolment is more than negatively offset by the wage disadvantage of choosing non-STEM fields of study (Anger et al., Citation2016; Black et al., Citation2008). Gender equality is therefore not reached through German higher education, also because women still have lower odds of entering higher education than men (Lörz et al., Citation2011). On the bright side, the absence of a gender effect on the institution choice net of study field preferences underlines the de jure equality of Germany’s two higher education tracks. Traditional universities and universities of applied sciences are valued equally by men and women at similar study field preferences.

Future studies may want to address women’s representation at traditional universities in other contexts (cf. P. N. Blossfeld et al., Citation2015). For example, women may be less well represented at traditional universities in contexts with weaker societal affluence and less egalitarian gender-role expectations (cf. Stoet & Geary, Citation2020). However, this may be counteracted by an economic need among men and women in these contexts to participate in lucrative educational pathways (cf. Charles, Citation2017). Given these unclarities and the importance of gender differences in higher education for further gender segregation, researching these gender differences remains an essential task for scholars.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (35.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data and code availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi; https://doi.org/10.5157/NEPS:SC5:14.0.0). The data are not publicly available because they could compromise the privacy of research participants, but can be requested at LIfBi.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Wilfred Uunk

Wilfred Uunk is a professor in Sociology (Macro Sociology and Social Inequality) at the University of Innsbruck. His research interests comprise social inequality, sociology of the family (marriage, divorce), ethnicity, and gender. His work has been published in among others Acta Sociologica, European Journal of Population, European Sociological Review, Social Indicators Research, Social Science Research, and Work, Employment & Society.

Magdalena Pratter

Magdalena Pratter (MSc) is a researcher at the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi). Her research interests include gender and education (Competencies, Personality, Learning Environments).

Notes

1 This may partly be due to the German educational system, where vocational education is fully developed, also in postsecondary education (Reimer & Pollak, Citation2010). Nevertheless, for other countries it also remains unclear whether the overrepresentation of women in higher education implies higher odds for women than men to enter higher education.

2 The Federal Statistical Office reports that in the winter semester 2019–2020, 2.9 million students were enrolled at higher education institutions in Germany (Destatis, Citation2021c). Of these, 1.8 million were studying at the 106 traditional universities and 1 million at the 246 universities of applied sciences.

3 In Germany, there are three hierarchically differentiated types of secondary education (Hauptschule, Realschule, Gymnasium), into which pupils are selected at the age of 10 or 12 and which are relatively hard to cross. Only the highest Gymnasium level qualifies for all higher education majors. Students may also enroll in higher education via upper secondary vocational education (Berufliche Schule), yet the share of students who do so is low (cf. Buchholz et al., Citation2016; also see findings below).

4 Whether wages or life-time earnings vary by type of institution and study field is not known, however. Stüber (Citation2016) reports on occupational field differences in wages by level of education, yet does not differentiate traditional university from FH.

5 P. N. Blossfeld et al. (Citation2015) graphically displayed transition rates from upper secondary education to traditional university graduation and FH graduation by gender, cohort, and social origin. Yet, they neither tested gender differences in the institution choice (from the figures, it is hard to detect a gender difference) nor investigated its causes. Destatis (Citation2021c) reports on the share of students at traditional university and at universities of applied sciences and on the share of women among all higher education students, yet not on the two figures combined. The only indication of gender differences in the type of higher education can be obtained from graduation statistics. Destatis’ (Citation2021b) figures display that in the year 2018 the share of women obtaining a traditional university diploma (excluding teaching educations) was 58%, the share of women obtaining a diploma of university of applied sciences was 47%, and the share of women obtaining a diploma of teaching educations was 72%. From this, it seems that women are overrepresented at traditional university and underrepresented at FH. Yet, these figures do not necessarily tell something about gender differences in enrolment rates since there exist gender differences in completion that in addition can be institution specific (Heublein & Schmelzer, Citation2018).

6 In this respect, Lörz et al. (Citation2011) speak of the “scholastic pathway to upper secondary education” (p. 189) and Hägglund and Lörz (Citation2020) of the “previous educational biography” (p. 66).

7 Obtaining a fachgebundene Hochschulreife (qualification entitling holder to study particular subjects at a higher education institution) may be another scholastic factor leading to gendered higher education choices, because men more often acquire this qualification than women (Lörz et al., Citation2011) and because this qualification is likely to lead more often to a choice for FH than for a traditional university. However, including this factor on top of vocational school attendance is not meaningful in our analyses. The fachgebundene Hochschulreife is only frequently obtained by students who attended vocational school (42%) and infrequently obtained among students who did not attend vocational school (2%; among all students the share is 4%). Modelling it would imply estimating the vocational school effect twice. Estimating the fachgebundene Hochschulreife effect for students who attended vocational school is not meaningful either since for two thirds of these students this information is missing. Robustness analyses showed that dropping those with a fachgebundene Hochschulreife did not affect the observed gender difference in institution choice (Online Appendix, Table A1).

8 Since our data lack information on prior study field or interest in secondary education, we use the factual study field in our analyses. Although the study field is part of the study choice process prospective students undertake and could be seen as part of the outcome variable, it is obvious that the unequal distribution of study fields across institutions limits higher education options (Lörz et al., Citation2011). Furthermore, in Germany most prospective students first choose a field of study before choosing a particular higher education institution (Herrmann & Winter, Citation2009). The reverse holds in the North-American educational system due to the differences in prestige across higher education institutions.

9 From 2008 to 2013, NEPS data were collected as part of the Framework Programme for the Promotion of Empirical Educational Research funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). As of 2014, NEPS is carried out by the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi) at the University of Bamberg in cooperation with a nationwide network.

10 In the Grade 9 data, we did not observe a gender difference in institution choice. This may partly be due to tracking pupils in a panel design: Pupils who enter higher education via alternative routes (mainly males who disproportionally end up at FH) may be underrepresented.

11 The gender difference in exam grades is not due to women choosing STEM subjects less often than men. Additional analysis revealed that the gender gap in exam grades could only partly – for one third – be explained by study field choice (from an effect of being female of 0.20 to 0.14; p < 0.01). At similar subjects, women therefore obtain still higher exam grades. Note that our models are multivariate, modelling both the overall exam grade and study field choice, so that the association between study field choice and grades is taken into account.

References

- Anger, C., Koppel, O., & Plünnecke, A. (2016). MINT – Frühjahrsreport [STEM – spring report]. Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft.

- Aßmann, C., Steinhauer, H. W., Kiesl, H., Koch, S., Schönberger, B., Müller-Kuller, A., Rohwer, G., Rässler, S., & Blossfeld, H.-P. (2011). Sampling designs of the National Educational Panel Study: Challenges and solutions. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaften, 14(S2), Article 51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-011-0181-8

- Atherton, O. E., Grijalva, E., Roberts, B. W., & Robins, R. W. (2021). Stability and change in personality traits and major life goals from college to midlife. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 47(5), 841–858. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167220949362

- Becker, G. S. (1993). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education (3rd ed.). The University of Chicago Press.

- Black, D. A., Haviland, A. M., Sanders, S. G., & Taylor, L. J. (2008). Gender wage disparities among the highly educated. Journal of Human Resources, 43(3), 630–659. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.43.3.630

- Blossfeld, H.-P., & Roßbach, H.-G. (2019). Education as a lifelong process: The German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS) (2nd ed.). Springer VS.

- Blossfeld, P. N., Blossfeld, G. J., & Blossfeld, H.-P. (2015). Educational expansion and inequalities in educational opportunity: Long-term changes for East and West Germany. European Sociological Review, 31(2), 144–160. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcv017

- Bobbitt-Zeher, D. (2007). The gender income gap and the role of education. Sociology of Education, 80(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/003804070708000101

- Breda, T., & Napp, C. (2019). Girls’ comparative advantage in reading can largely explain the gender gap in math-related fields. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(31), 15435–15440. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1905779116

- Buchholz, S., Skopek, J., Zielonka, M., Ditton, H., Wohlkinger, F., & Schier, A. (2016). Secondary school differentiation and inequality of educational opportunity in Germany. In H.-P. Blossfeld, S. Buchholz, J. Skopek, & M. Triventi (Eds.), Models of secondary education and social inequality: An international comparison (pp. 79–92). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Ceci, S. J., & Williams, W. M. (2010). Sex differences in math-intensive fields. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(5), 275–279. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721410383241

- Charles, M. (2017). Venus, Mars, and math: Gender, societal affluence, and eighth graders’ aspirations for STEM. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 3, 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023117697179

- Charles, M., & Bradley, K. (2009). Indulging our gendered selves? Sex segregation by field of study in 44 countries. American Journal of Sociology, 114(4), 924–976. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/595942

- Correll, S. J. (2001). Gender and the career choice process: The role of biased self-assessments. American Journal of Sociology, 106(6), 1691–1730. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/321299

- Destatis. (2021a). Graduates/school-leavers by type of qualification. Retrieved October 1, 2021, from https://www.destatis.de/EN/Themes/Society-Environment/Education-Research-Culture/Schools/Tables/liste-graduates-scholl-leavers-qualification.html

- Destatis. (2021b). Groups of examinations, sex and average age. Retrieved October 1, 2020, from https://www.destatis.de/EN/Themes/Society-Environment/Education-Research-Culture/Institutions-Higher-Education/Tables/groups-examinations-sex-average-age.html

- Destatis. (2021c). Students by sex (total and German students). Retrieved October 1, 2021, from https://www.destatis.de/EN/Themes/Society-Environment/Education-Research-Culture/Institutions-Higher-Education/Tables/lrbil01.html

- DiPrete, T. A., & Buchmann, C. (2013). The rise of women: The growing gender gap in education and what it means for American schools. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Duckworth, A. L., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2006). Self-discipline gives girls the edge: Gender in self-discipline, grades, and achievement test scores. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(1), 198–208. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.198

- Eccles, J. S. (2009). Who am I and what am I going to do with my life? Personal and collective identities as motivators of action. Educational Psychologist, 44(2), 78–89. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520902832368

- Erikson, R., & Jonsson, J. O. (1996). Explaining class inequality in education: The Swedish test case. In R. Erikson & J. O. Jonsson (Eds.), Can education be equalized? The Swedish case in comparative perspective (pp. 1–63). Westview Press.

- Esteve, A., García-Román, J., & Permanyer, I. (2012). The gender-gap reversal in education and its effect on union formation: The end of hypergamy? Population and Development Review, 38(3), 535–546. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2012.00515.x

- Fairlie, R. W. (1999). The absence of the African-American owned business: An analysis of the dynamics of self-employment. Journal of Labor Economics, 17(1), 80–108. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/209914

- Fairlie, R. W. (2005). An extension of the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition technique to logit and probit models. Journal of Economic and Social Measurement, 30(4), 305–316. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3233/JEM-2005-0259

- Hägglund, A. E., & Lörz, M. (2020). Warum wählen Männer und Frauen unterschiedliche Studienfächer? [Why do men and women differ in their choice of fields of study?]. Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 49(1), 66–86. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/zfsoz-2020-0005

- Hakim, C. (2002). Lifestyle preferences as determinants of women’s differentiated labor market careers. Work and Occupations, 29(4), 428–459. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888402029004003

- Hecken, A. E. (2006). Bildungsexpansion und Frauenerwerbstätigkeit [Educational expansion and female employment]. In A. Hadjar & R. Becker (Eds.), Die Bildungsexpansion. Erwartete und unerwartete Folgen (pp. 123–155). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Heine, C., Egeln, J., Kerst, C., Müller, E., & Park, S.-M. (2006). Ingenieur- und Naturwissenschaften: Traumfach oder Albtraum? Eine empirische Analyse der Studienfachwahl [Engineering and science: Dream study or nightmare? An empirical analysis of study choice]. Nomos.

- Heine, C., Spangenberg, H., & Lörz, M. (2007). Nachschulische Werdegänge studienberechtigter Schulabgänger/innen [After-school careers of qualifying graduates] (HIS: Forum Hochschule No.11). https://www.dzhw.eu/pdf/pub_fh/fh-200711.pdf

- Helbig, M. (2010). Sind Lehrerinnen für den geringeren Schulerfolg von Jungen verantwortlich? [Are female teachers responsible for the school performance gap between boys and girls?]. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 62(1), 93–111. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-010-0095-0

- Helbig, M. (2013). Geschlechtsspezifischer Bildungserfolg im Wandel. Eine Studie zum Schulverlauf von Mädchen und Jungen an allgemeinbildenden Schulen für die Geburtsjahrgänge 1944–1986 in Deutschland [Trends in gender-specific educational success. A study into the school career of girls and boys in general education for the birth cohorts 1944–1986 in Germany]. Journal for Educational Research Online, 5, 141–183. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.25656/01:8023

- Herrmann, V., & Winter, M. (2009). Studienwahl Ost. Befragung von westdeutschen Studierenden an ostdeutschen Hochschulen [Study choice East. Survey of West-German students in East German higher education institutions] (HoF-Arbeitsbericht No. 2). https://www.hof.uni-halle.de/dateien/ab_2_2009.pdf

- Heublein, U., & Schmelzer, R. (2018). Die Entwicklung der Studienabbruchquoten an den deutschen Hochschulen. Berechnungen auf Basis des Absolventenjahrgangs 2016 [The development of dropout rates in German higher education institutions. Calculations on basis of the graduation cohort 2016] (DZHW Projektbericht No. 7). https://idw-online.de/en/attachmentdata66127.pdf

- Jann, B. (2006). Fairlie: Stata module to generate nonlinear decomposition of binary outcome differentials. https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s456727.html

- Jonsson, J. O. (1999). Explaining sex differences in educational choice: An empirical assessment of a rational choice model. European Sociological Review, 15(4), 391–404. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.esr.a018272

- Lörz, M. (2017). Soziale Ungleichheiten beim Übergang ins Studium und im Studienverlauf [Social inequalities in the transition into and during higher education]. In M. S. Baader & T. Freytag (Eds.), Bildung und Ungleichheit in Deutschland (pp. 311–338). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Lörz, M., Quast, H., & Woisch, A. (2012). Erwartungen, Entscheidungen und Bildungswege. Studienberechtigte 2010 ein halbes Jahr nach Schulabgang [Expectations, decisions, and educational pathway of study entrants in 2010 half a year after graduation] (HIS: Forum Hochschule, No. 5). https://www.uni-heidelberg.de/md/journal/2012/07/fh201205_karriereerwartung.pdf

- Lörz, M., Schindler, S., & Walter, J. G. (2011). Gender inequalities in higher education: Extent, development and mechanisms of gender differences in enrolment and field of study choice. Irish Educational Studies, 30(2), 179–198. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2011.569139

- Mann, A., & DiPrete, T. A. (2013). Trends in gender segregation in the choice of science and engineering majors. Social Science Research, 42(6), 1519–1541. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2013.07.002

- Ochsenfeld, F. (2016). Preferences, constraints, and the process of sex segregation in college majors: A choice analysis. Social Science Research, 56, 117–132. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.12.008

- Piopiunik, M., Kugler, F., & Wößmann, L. (2017). Einkommenserträge von Bildungsabschlüssen im Lebensverlauf: Aktuelle Berechnungen für Deutschland [Income returns of educational qualifications during the life course]. Ifo Schnelldienst, 70(7), 19–30.

- Reimer, D., & Pollak, R. (2010). Educational expansion and its consequences for vertical and horizontal inequalities in access to higher education in West Germany. European Sociological Review, 26(4), 415–430. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcp029

- Schmillen, A., & Stüber, H. (2014). Lebensverdienste nach Qualifikation: Bildung lohnt sich ein Leben lang [Life time incomes by qualification: Education pays off one’s whole life] (IAB-Kurzbericht No. 1). http://doku.iab.de/kurzber/2014/kb0114.pdf

- Schofer, E., & Meyer, J. W. (2005). The worldwide expansion of higher education in the twentieth century. American Sociological Review, 70(6), 898–920. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240507000602

- Spelke, E. S. (2005). Sex differences in intrinsic aptitude for mathematics and science? A critical review. American Psychologist, 60(9), 950–958. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.60.9.950

- Stoet, G., & Geary, D. C. (2020). Gender differences in the pathways to higher education. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(25), 14073–14076. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2002861117

- Stüber, H. (2016). Qualifikation zahlt sich aus [Qualification pays off] (IAB-Kurzbericht No. 17). http://doku.iab.de/kurzber/2016/kb1716.pdf

- Treiman, D. J. (1977). Occupational prestige in comparative perspective. Academic Press.

- UNESCO International Institute for Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean. (2021). Women in higher education: Has the female advantage put an end to gender inequalities? https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000377182

- Uunk, W. J. G., Beier, L., Minello, A., & Blossfeld, H.-P. (2019). Studienfachwahl MINT durch Frauen – Einfluss von Leistung in Mathematik, Lebenszielen und familialem Hintergrund [STEM study choice by women – the influence of mathematics performance, life goals, and family background]. In E. Schlemmer & M. Binder (Eds.), MINT oder Care? Gendersensible Berufsorientierung in Zeiten digitalen und demografischen Wandels (pp. 185–199). Beltz/Juventa.

- Weinhardt, F. (2017). Ursache für Frauenmangel in MINT-Berufen? Mädchen unterschätzen schon in der fünften Klasse ihre Fähigkeiten in Mathematik [Cause of the shortage of women in STEM professions? Girls underestimate their math competencies already in fifth class] (DIW Wochenbericht No. 45). https://www.diw.de/documents/publikationen/73/diw_01.c.568691.de/17-45-1.pdf