ABSTRACT

In primary-level German writing instruction, spelling discussions (German: Rechtschreibgespräche) have become a well-established interactional method of teaching orthography, prompting the children to exchange their hypotheses about orthographic features of written words. Focusing on spellings of ambisyllabic consonants, this conversation-analytic paper reports about teacher-led and small-group spelling discussions of fourth-graders in a German school in Spain. As the data show, the students and the teacher approach and accomplish the task of accounting for the spellings of pre-selected words in various ways: by drawing on vowel quantity, by comparing phonetic minimal pairs, by applying morphologic extension, and by employing oral syllabifying as well as syllable scooping. The findings indicate that spelling discussions provide opportunities for teachers and students to negotiate their understanding of orthographic rules while displaying metalinguistic knowledge and practicing communicative skills. Illuminating how theoretic-didactic approaches to spelling instruction are put into practice in the classroom, the data reveal that the participants do not strictly adhere to one single approach, but creatively draw on various operations to account for a specific spelling. From these observations we derive insights for the training of (future) L1 and L2 German teachers.

Introduction

Quite a substantial body of research exists on the development of writing and text composition skills in German-speaking children (e.g., Weinhold Citation2009; Hüttis-Graff and Jantzen Citation2012), but rather little is known about the development of writing competencies in multilingual children (e.g., Becker Citation2011). Some studies have investigated how learners conjointly compose a text (e.g., Pelchat Citation2017), but considerably less attention has been devoted to the teaching and learning of German orthography in the classroom, i.e., to how the students interact with each other and with the teacher when they learn about, discover and discuss spelling conventions. Although so-called spelling discussions (German: Rechtschreibgespräche) have become a well-established interactional method of teaching orthography in the primary German classroom, hardly any research into the actual conversations that unfold during spelling discussions exists to date. Accordingly, little is known about how children express, share and negotiate their metalinguistic knowledge that forms the basis of grasping German spelling rules. The present paper wants to contribute to closing this gap by providing insights gained from spelling discussions in a German primary school in Spain that were recorded in the context of a larger research project on spelling discussions (Geist Citation2017). Prompting the learners to jointly reflect about spellings and their underlying rules, spelling discussions allow for a focus on form context for language learning (Kunitz and Skogmyr Marian Citation2017, 518). By targeting the spellings of ambisyllabic consonants in German, this paper explores how teachers and students account for specific spellings by implicitly or explicitly drawing on various phonographic, syllabic and morphological operations. After introducing the teaching method of spelling discussions and reviewing interactional studies of orthographic learning, we will provide the linguistic and didactic background on (teaching) German ambisyllabic consonants that we believe is necessary to understand our analyses and findings. We will then present extracts of spelling discussions and our analyses, starting with teacher-led whole-class interactions followed by small group interactions. The paper concludes with implications of our findings for language teacher education.

Spelling discussions

The didactic method of spelling discussions (Rechtschreibgespräche) arose in Germany and is based on the fact that German has a comparatively consistent or ‘shallow’ orthography. This means that a large portion of German spellings can be explained based on phoneme-grapheme correspondencies (predictable letter-sound relationships), which makes German orthography much more regular than that of e.g. English (Seymour, Aro, and Erskine Citation2003). In addition, German orthography is characterized by phonographic, syllabic and morpho-syntactic regularities (e.g., umlaut spellings, silent syllable-initial <h>,Footnote1 ambisyllabic consonantsFootnote2) whose underlying rules have to be consciously learned (by both L1 and L2 speakers). These morphological regularities present potential stumbling blocks to learners, and spelling discussions are one way of addressing them in the classroom. In the course of a spelling discussion, the learners are provided with the written representation of a word that contains the spelling phenomena in question, and invited to verbalize their observations and hypotheses about the orthographic features they see (Leßmann Citation2014; Schröder Citation2014). Thus, spelling discussions are designed to give students the opportunity to explain spellings and to reflect about spellings in a cooperative arrangement.

Spelling discussion are assumed to have quite some potential to foster orthographic learning in various ways (Budde, Riegler, and Wiprächtiger-Geppert Citation2011). Since they encourage the learners to explain their knowledge of regularities and their strategies for spelling words and thus promote language awareness (Müller Citation2010, 89), spelling discussions are understood as problem-solving conversational situations that challenge the children to be actively involved in the conjoint creation of explanations. In addition, it is assumed that this format truly benefits from the heterogeneity within a class (Leßmann Citation2014, 47) as each child can contribute their own competences and knowledge to the task at hand. Spelling discussions are one way of teaching children how to systematically approach the production, checking, and revision of spellings (Schröder Citation2014, 24). What is more, the discussions necessitate (and potentially foster) a high level of communicative competence in the children and can thus also fulfil a conversational-didactic function (Geist Citation2017). By extension, this implies that they pose a certain challenge to the teacher as a role model (Schröder Citation2014, 24) in communicating about and explaining spellings. Accordingly, spelling discussions require high levels of conversational, subject-matter and didactic skills in the teacher, for instance in dealing not only with the correspondencies but also with the discrepancies between spoken and written language and in imparting the respective knowledge adequately to the learners.

Interactional studies on orthographic learning in German (second) language teaching

Despite the above benefits attributed to this teaching method, neither student-student nor student-teacher interaction during spelling discussions has been investigated from a conversation-analytic perspective to date. A very small number of studies exist that have chosen an interactional framework for the analysis of orthographic learning, which are briefly reviewed here. Due to the specific relevance of morphologically, syntactically and syllabically motivated German spelling rules (see above), we will mainly focus on research into German orthographic learning, although we are aware of interactional studies examining spelling practices for other target languages. English spelling, for instance, has been the focus of studies by Čekaite (Citation2009) and Musk (Citation2016), who investigated Swedish EFL learners’ interactions revolving around the use of computer software to manage spelling problems. Stoewer (Citation2018) analysed spelling instruction in English mother tongue classes with a focus on the multimodal organization of spelling rounds and problems arising out of the low phoneme-grapheme-correspondency of English (such as silent letters). Kunitz and Skogmyr Marian (Citation2017) report about doing spelling as a form-focused activity in a writing task in small-group work in an English as a foreign language class in a Swedish junior high school, analyzing how three students deal with the spelling of the word disgusting during their poster creation task. As the (unsolved) spelling trouble is still present in their presentation a few days later, the authors show how a spelling issue ‘becomes a moral and not just a learning matter’ (529), thereby underlining the importance of spelling instruction for overall academic achievement.

With respect to our study’s focus on German spelling discussions, we will now review interactional studies on teaching and learning German orthography. Kotthoff (Citation2009) analyses how the spelling of ambisyllabic consonants, which are usually realized by double letters, is treated in a mother tongue German lesson in Germany. She shows that the phenomenon is not adequately explained based on its phonographic and morphological characteristics, but rather that the analysis is reduced to the simple task of finding double consonant letters in a text. In doing so, the teacher ascribes to the language material an explanatory function which it clearly cannot fulfil. She concludes: ‘A systematic approach is relinquished in favour of a focus on simple occurrences’ (132, translation by authors). But far from framing this as a criticism of the teacher, Kotthoff analyses the complex interaction situation of the lesson, in which the task (finding double letters) is pushed to the foreground, thereby obfuscating the actual aim of generating a systematic understanding of the phenomenon in question. Based on the children’s non-academic but quite apt metaphoric labelling of the ambisyllabic consonant’s effect on the vowel as Quetschen (‘squashing’), she concludes that explanations of language phenomena should not be focused on precise linguistic terminology, but rather on the attentive, joint observation and discovery of the language material – a condition which spelling discussions meet quite well.

Mehlem and Lingnau (Citation2012) as well as Lingnau and Mehlem (Citation2012) report about the interactive construction of spellings in teacher-student as well as student-student-interactions in a German classroom in Germany with a focus on children whose first language is not German. Their data show how the teacher’s and peers’ advice to resort to the phonological plane and to write what they hear (‘keep saying it, keep listening,’ Mehlem and Lingnau Citation2012, 137) is unsuccessful for post-vocalic <r> (as in Stern, ‘star’) as it is realized phonetically as the vowel /ɐ/. Likewise, the strategy chosen by an L1 German peer to read out phonetically the L2 learners’ incorrect spelling <Pfesik> of Pfirsich (‘peach’) did not yield the desired effect as the L2 speaker had not yet mastered the targetlike pronunciation of this word and thus was unable to hear her errors. These data are thus indicative of problems that arise when teachers are not aware of the specific challenges L2 learners may face. In English foreign language didactics, for example, the establishment of the ‘meaning-pronunciation-spelling triangle’ has been identified as crucial in introducing new lexical matter (Glaser Citation2018, 157). Similarly, Mehlem and Lingnau (Citation2012, 149) suggest for German orthography the exploration of instructional procedures which include prosodic information as well.

Lingnau and Mehlem (Citation2012)’s study corroborates the importance of phonetic and prosodic awareness in teaching German orthography, especially when instructing L2 speakers. Their data show how the teacher, in her desire to make the children hear each phonetic segment in a range of (partly unfamiliar) target words, over-articulates the schwa in unstressed syllables to the point of overriding the trochaic word stress and thus the standard pronunciation. With regard to the word Reifen /ˈʁaɪfən/ (‘tyre’), the authors document in detail how this causes a learner to not only imitate the non-targetlike pronunciation, but also to add a final /t/ to the second syllable (resulting in /ˈʁaɪˈfɛnt/) because she had erroneously perceived this in the teacher’s distorted pronunciation. It takes several correction rounds before the teacher succeeds in making the learner realize her segmental error. At the same time, the teacher’s subsequent attentive and motivating interaction with this student shows how the learner eventually succeeds in imitating the teacher’s target-like pronunciation. The authors conclude that such a collaboration shows the students that the effort they invest into their spelling is recognized and appreciated by the teacher. In addition, Lingnau and Mehlem discuss possible benefits of providing the children (especially L2 German learners) with an additional phonemic spelling for each word. Also, they suggest that most learners would profit from a more systematic conjoint discovery of the spelling patterns of the schwa /ə/ in the unstressed second syllable of many German words.

That German teachers tend to change their articulation and stress patterns when determining syllable structures has also been shown by Kern (Citation2018) and by Buttlar and Weiser-Zurmühlen (Citation2019). Kern (Citation2018) analysed small-group interactions of one teacher and two to three first-grade students with regard to how the teacher and children use clapping-while-speaking to determine the syllable structure of individual words. Her data show how some words are ‘prosodically emphasized in a variety of ways… chang[ing] the words’ standard prosody dramatically’ (Kern Citation2018, 39). With regard to a word with an ambisyllabic consonant (Kanne, ‘pot’), Kern shows how the teacher speaks and claps the first syllable /kan/, then produces a noticeable break and starts the second syllable with a second /n/, which is not part of the standard articulation, thus transferring the graphematic syllables Kan-ne into a phonological form. In addition, she changes the schwa /ə/ in the second, unstressed syllable to the full vowel /ɛ/, thereby changing the regular trochaic rhythm of the word. Kern’s data also reveal how the children’s synchronizing their clapping behaviour with their teachers’ is (mis)interpreted as a displayed understanding of syllabification when in fact they simply synchronize their bodily conduct with that of the teacher. In a similar vein, Buttlar and Weiser-Zurmühlen (Citation2019) show in their analysis of the classroom interaction of a German lesson in Germany how the teacher changes the standard pronunciation of springen (‘to jump’) from /ˈʃpʁɪŋən/ to /’ʃpʁɪŋ’gɛn;/ in attemtping to help a learner struggling with the correct spelling <ng> of the nasal /ŋ/. By inserting a /g/-sound into her oral production of the word and stressing the second, unstressed syllable, the teacher also resorts to overriding the word’s trochaic structure; in addition, she fails to consider <ng> as a digraph representing the ambisyllabic consonant and thus only one sound.

Ambisyllabic consonants in German language teaching

The data analysed in the present study revolve around spelling discussions of double consonant letters, more specifically ambisyllabic consonants. Since we feel that a basic understanding of this orthographic phenomenon as well as of the approaches that have been suggested to teach it is an essential prerequisite for our analysis section, this section serves to provide the necessary linguistic and didactic background. An ambisyllabic consonant is a consonant that is shared by two syllables, simultaneously forming the coda of the first and the onset of the second syllable, as in kommen /ˈkɔmən/ (‘to come’). Accordingly, in German ‘a phonological syllable boundary may lie within a constituent, quite in contrast to a graphematic one’ (Primus Citation2003, 36, translation by authors). Because of its hinge-like function, an ambisyllabic consonant is also commonly referred to as syllable joint (German: Silbengelenk). Syllable joints give rise to a closed first syllable and a CV(C) second, a phenomenon which German speakers produce in their regular speech flow but are usually not consciously aware of. The vowel in the pre-jointFootnote3 syllable is always lax.

MostFootnote4 German ambisyllabic consonants are realized as double letters, such as <mm>, <ff>, <pp> etc., which, due to the principle of morphemic consistency (Morphemkonstanz), are also retained in inflected monosyllabic forms (as in the imperative komm). In terms of spelling challenges, the double letters contrast with (and are a potential source of confusion with) single letters, which usually follow tense vowels and do not constitute syllable joints, as the contrast pair hassen /’hasən/ (‘to hate’) and Hasen /’hɑ:.sən/ (‘rabbits’) illustrates. Accordingly, German spelling didactics is, among other things, concerned with the question of how to teach best whether to use a single or double consonant letters following a vowel. Interestingly, so far the literature has not suggested any differences in the teaching of orthography in the L1 versus the L2 classroom; rather, all of the following approaches are used in both L1 and L2 (or L3) classrooms.

One approach to help children learn these (and other) spellings is the graphematic approach, also known as Syllable-Analytic Method, which on principle does not explain the spellings on the basis of their pronunciation but orients exclusively to the written form. The goal of this approach is to build a systematic syllabic concept in the learner (Röber Citation2009) by providing graphic representations of a word’s morpheme structure such as word stems and endings, based on the typical trochaic structure of two-syllable words in German as well as on morphemic consistency (Bredel, Fuhrhop, and Noack Citation2011). In a recent intervention study with 364 fifth-graders, Bangel and Müller (Citation2018) showed that the learners taught with this approach displayed a significantly greater learning progress in their spelling abilities than the controls, whose instruction did not feature a systematic syllabic concept, and that especially children with poor spelling competences benefited from this analytic method. What remains a desideratum, however, is empirical research from an interactional perspective that investigates how teachers discuss spellings with their students in this approach (but note that one case is shown in Geist Citation2018).

An alternative didactic approach is the phonographic perspective, which stands in quite some contrast to the graphematic perspective since phonographic approaches explain spellings based on pronunciations and thus based on an intuitive rather than a systematic syllabic concept. One of these phonographic approaches explains double consonants spellings with the laxness of the vowel in the pre-joint syllable, i.e., on the basis of vowel quantity. This view is rooted in the authoritative reference book on German orthography, the Duden, which explains double consonant spellings as follows: ‘If a stressed lax stem vowel is followed by a single consonant, this vowel laxness is characterized by a doubling of the consonant letter.’ (Duden Citation2006, 1163, own translation). This ‘official’ perspective has been adopted in a range of teaching approaches that ask the students to indicate vowel length (lax or tense, usually dubbed ‘short’ or ‘long’) in given (rhyme) words featuring single or double consonant letters. It has also been adopted as a rule for written production, advising children that they are to write a double letter if they hear the preceding vowel as ‘short’. However, this transfer of the authoritative explanation into didactic approaches is not entirely unproblematic as it does not prove helpful to all children,Footnote5 fueling the long-standing debate on how to explain and teach the spelling of ambisyllabic consonants best (Primus Citation2003; Ossner Citation2016).

A second phonographic approach tries to explain spellings based on their pronunciation via Mitsprechen (Speak-Along) and can be summed up by its catchphrase Schreib wie du sprichst, aber sprich deutlich! (‘Write as you speak, but speak clearly.’). This approach is rooted in the relatively high phoneme-grapheme correspondency of German, and seeks to also apply this sound-letter fit to areas where the orthography is based on syllabic rather than phonemic regularities – such as ambisyllabic consonants. Examples of teaching materials featuring this approach are Sommer-Stumpenhorst’s (Citation2015) Rechtschreibwerkstatt (‘Orthography Workshop‘) and the Freiburger Rechtschreibschule FRESCH (‘Freiburg School of Orthography‘) (Brezing et al. Citation2018). The latter has been adopted quite widely in German primary schools, especially its problem-solving operations of morphologic extension (Verlängern, symbolized by an arrow attached to a scoop),Footnote6 recourse to root (Ableiten aus dem Wortstamm, symbol: lightning bolt)Footnote7 and oral syllabifying (Sprechschwingen or Sprechschreiben, symbol: two connected scoops), which is a carefully enunciated syllabic speaking intended to hear the syllable boundaries clearly (also labelled pilot speech (Pilotsprache), e.g. Lingnau and Mehlem Citation2012). The latter is often accompanied by a visual reproduction of this acoustically identified syllable pattern by drawing syllable scoops underneath the word.Footnote8

Proponents of this approach claim that double consonant letters can be made audible by means of an oral syllabifying that features a clear pause at the syllable boundary, resulting in a reduplication of the joint consonant (Reuter-Liehr Citation2008), very similar to how the teacher in Kern (Citation2018) adapted her pronunciation of Kanne to obtain a duplicate consonant at the joint. However, research suggests that such an oral syllabication is triggered by orthographic knowledge rather than the other way round: Pre-school children and first graders have been shown to close the pre-joint syllable only irregularly, producing an open syllable instead (Hanke Citation2002; Huneke Citation2002; Pröll, Freienstein, and Ernst Citation2016). Likewise, some children produced syllable joints in control items that had none (Risel Citation1999), such as the tense-vowel word Stufe /’ʃtu:fə/ (‘stair’), which was spelled as <Stuffe> and pronounced as /’ʃtu:fəfə/ (Eckert and Stein Citation2004). The further children advance in the school system and become familiar with orthographic rules, however, the more their syllabic speaking contains duplicate consonants, thus mimicking the orthographic representation (Risel Citation2002). Accordingly, it cannot be assumed that children possess an intuitive grasp of the syllabic structure of words but rather that this develops as a result of their literacy training (Risel Citation2002).

However, what all of the reviewed approaches have in common is that they require some sort of linguistic awareness (Ossner Citation2013), and that the knowledge they aim to impart can only be tapped and acquired if it is negotiated in the interaction with others, e.g. in spelling discussions. What is more, the heterogeneity with which children approach ambisyllabic consonants presents a great challenge to teachers, who have to identify the various patterns and adjust their instruction accordingly. Yet, to date hardly any interactional research has been carried out to investigate how teachers and learners invoke spelling rules during classroom discourse. In order to help close this gap, the present study analyses spelling discussions in the German L2 classroom that revolve around ambisyllabic consonants, aiming to show how the controversial phenomenon of ambisyllabic consonants is dealt with by the pupils and the teacher. By addressing this research question, we seek to provide new insights into the interactional intricacies of teaching and learning orthography in the L2 German classroom and hope to derive new impulses for (L2) German teacher education.

Materials and methods

Methodological background: conversation analysis, interactional linguistics, and CA-for-SLA

The present analysis draws upon Conversation Analysis (CA) (Hutchby and Wooffitt Citation1998; Sidnell Citation2010), Interactional Linguistics (Couper-Kuhlen and Selting Citation2018; Barth-Weingarten, Citation2008), and CA-for-SLA (Kasper and Wagner Citation2011; Markee and Kunitz Citation2015). CA analyses spoken interaction in its sequential nature as shaped by the participants in their social context and thus aims to identify conversation patterns as they emerge from the data (Walsh and Li Citation2016, 494). It is based on the premise that the interactional context is constantly being constituted and reconstituted by the specific actions and practices of the interactants. As an extension of this approach, Interactional Linguistics investigates ‘two sorts of questions which implicate language: (i) what linguistic resources are used to articulate particular conversational structures and fulfil interactional functions? and (ii) what interactional function or conversational structure is furthered by particular linguistic forms and ways of using them?’ (Couper-Kuhlen and Selting Citation2001, 3). Thus, we draw on the sequential analysis of a collection from spelling discussions (see details below) to investigate the linguistic, i.e. phonetic and prosodic, resources that participants deploy for achieving specific actions, e.g. doing oral syllabifying. Since our data feature L2 learners of German, our study is further in line with a CA-for-SLA approach. ‘CA‐for‐SLA/CA‐SLA is a form of ethnomethodological conversation analysis that unpacks second language user‐learners’ common sense understandings of their own and their interlocutors’ real time, embodied language learning behaviors.’ (Markee and Kunitz Citation2015, 426). With respect to language learning in the classroom, this view takes into consideration that the participants constantly display their orientation towards institutional structures and norms in their communicative actions, thereby constituting institutional interaction as such (Heritage Citation1984, Citation2004). We believe that analysing spelling discussions from a CA-for-SLA perspective provides the opportunity to explore ‘how user‐learners orient to doing language learning behaviour in their own terms’ (Markee and Kunitz Citation2015, 430), and, by extension, how language teachers can support the learners in those endeavours.

Data

The data were collected in a fourth grade classroom in a German primary school in Spain. All students at this school acquire Spanish as (a) first language, and German is learned in school (for most pupils starting as early as kindergarten). Some of the children have also learned German in the home. All of the participants in our study were advanced learners of German and their phonetic realizations were near-native-like. At the school, the subjects German and Spanish are taught in the respective language; of the other subjects, some are taught in Spanish and some in German alternatingly between the school years.Footnote9 All students are required to speak only German during German lessons, in the context of which the spelling discussions took place.

The spelling discussions were carried out by a preservice primary school teacher with German as her main subject in the framework of her Master’s Thesis. She had been introduced to the method of spelling discussion as well as to the procedure and materials (see below), and potentially difficult spellings had been discussed with her thesis advisor before. She had observed the children’s German lessons several times prior to the discussions and asked the regular teacher about her didactic approaches to and materials used for spelling instruction. These materials were the online resource Rechtschreibwerkstatt (Sommer-Stumpenhorst Citation2015, see above) and the text book der-die-das (Jeuk, Sinemus, and Strozyk Citation2012), which is designed for multilingual classrooms in Germany. The book introduces the learners to the two operations of morphological extension and recourse to root. In terms of ambisyllabic consonants, the exercises in the book ask the students to mark the pre-joint vowel as either short (.) or long (_). We can thus conclude that by and large the textbook subscribes to a phonographic approach. In the spelling discussions analysed here, the goal was to encourage the children to talk about spellings but not to confront them with new didactic approaches to the orthographic phenomena.

Data were collected in spring of 2017 with an overall duration of about seven hours. In the fourth grade investigated here, 20 children (9–10 years old, 7 boys, 13 girls) took part in four spelling discussions that were carried out once a week during the regular German lessons and targeted one word with one or more double consonants at a time. While the former two were conducted by the preservice primary school teacher (henceforth: teacher) as teacher-led discussions, the latter two took place in small groups. Complex compound nouns containing several potential stumbling blocks were chosen to ensure that many children could participate in the discussions.

The first and second data sets analysed here were taken from the first and second session and thus from teacher-led discussions (target word 1, extracts 1a and 1b: Wäscheklammerkorb ‘clothes peg basket’, 32:44 min; target word 2, extract 2: Schlittschuhlaufbahn ‘ice-skating rink’, 35:53 min). The third data set stems from a small-group conversation among three students (two girls and a boy) during the third session (target word 3, extracts 3a, 3b, and 3c: Unterwasserkorallenriff ‘underwater coral reef’, 20:06 min). Although the data contain discussions of various spelling phenomena, in this paper we focus on the discussions of the double consonant spellings, namely <mm> and <tt> in the teacher-led discussions, and <ll> and <ff> in the small-group discussion. Spelling discussions had not been practiced in the class prior to the data collection and were explicitly introduced to the pupils as a university project with a focus on learning orthography. Accordingly, a factor that was taken into account during the analysis was that the participants were likely to orient to this overall framework and to conjointly accomplish the communicative task doing spelling of difficult words, producing their activities for each other and at the same time for the recording (Mondada Citation2006).

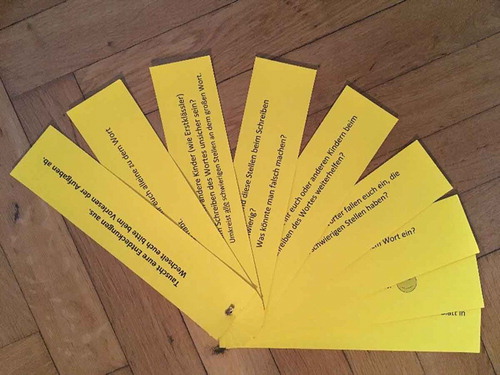

In both the teacher-led and the small-group condition, every spelling discussion started with a silent phase during which the children were asked to view a visual representation of the target word on a small card and to identify spots they found difficult. Accordingly, the students were not required to come up with possible spellings of the word on their own but asked to explain the correct spelling. The subsequent discussion proceeded in nine steps based on Schröder (Citation2014), which were introduced to the children in the form of a ‘question fan deck’ (Geist Citation2017), which, similar to a colour fan deck, presented each step on an individual strip (see Appendix 1 for details). Our analysis is based on a collection of cases of step 5, in which the children provided explanations for potential stumbling blocks (here: double consonant spellings), which they had identified themselves in step 3. The verbatim instructions on the strip read: ‘How can you help each other and other children to spell this word correctly?’ By step 5, the students had also been given a worksheet and asked to indicate the stumbling blocks they identified as well as the operations and explanations they employed during their discussion.

The corpus consists of audio recordings of face-to-face-interaction, as permission for video-recordings was not obtained (informed consent was obtained for the audio recordings from the teacher and all the students’ parents). We acknowledge the restrictions inherent in this type of data: How semiotic resources other than verbal and vocal resources are employed by participants cannot be analysed; also, how teaching media such as whiteboard, work sheets etc. are used can only be analysed when there is explicit reference or auditory evidence in the data (e.g. audible writing on the whiteboard). However, despite these constraints, we believe that the data yield important insights into the teaching and negotiation of orthography in spelling discussions. The data were transcribed according to the GAT 2 transcription system (Couper-Kuhlen and Barth-Weingarten Citation2011, see Appendix 2) and complemented by IPA symbols where we found it important to note phonetic variation. All participants’ names in the transcripts are pseudonyms.

Results

Our data show that a great deal of the spelling discussions revolved around agreeing on the operations that were relevant in the accounting for a specific spelling. We will first analyse how, in the teacher-led discussion, both the teacher and the students draw on a number of operations and perform them in more or less systematic ways. Subsequently, we will look at how the students invoke these operations implicitly and explicitly during their group work.

Teacher-led classroom interaction on the ambisyllabic consonant spellings <mm> and <tt>

The extracts from the teacher-led discussion presented here centre mostly on possible explanations of the double consonant spelling <mm> in the Klammer (‘peg’) section of Wäscheklammerkorb (‘clothes peg basket’, extracts 1a and 1b, in chronological order) in session 1, supplemented by data from the discussion of Schlittschuhlaufbahn below (extract 2) in session 2. Extract 1a illustrates how the teacher reintroduces the potentially problematic <mm>-spot in Klammer and attempts to elicit explanations:

Extract 1a: Wäscheklammerkorb_mm_vowel quantity

After pointing to the potentially problematic double <m> (line 235), the teacher refers to a previous student contribution (line 237) that had been provided by Carolina a few minutes earlier (if it’s a double consonant then it would be a short vowel, not shown), and mentions a crucial phenomenon, the vowel (line 239), rephrased in the school-grammar term Selbstlaut in line 241. The teacher allocates the turn to a student (line 245), who characterizes the vowel quantity as short (line 246). This is taken up by the teacher (line 247) by repeating the student’s word choice (repairing the case error along the way by substituting den for der) and adding the confirmation token genau/exactly (lines 247). Thus in this extract 1a, the student’s invoking of vowel quantity is accepted by the teacher as a helpful reason for the double consonant spelling.

The next extract (1b) shows the subsequent sequential unfolding, where the teacher introduces a further operation, viz. syllable scooping:

Extract 1b: Wäscheklammerkorb_mm_syllabifying

The teacher starts off a question (line 249), then pauses and repairs her previous turn-constructional unit (TCU) by changing it into an assertion that ends with a question tag (line 251). She thereby introduces another strategy for explaining the spelling of the word, viz. drawing syllable scoops below each syllable.

The teacher then checks with Carlos whether her assumption that the students have already employed syllable scoops is correct (lines 254 to 258). Carlos agrees and elaborates on this by introducing syllabic speaking, or oral syllabifying, as a further idea (in contrast to vowel quantity) (line 260): this uhm another idea might be !{↑´KLA!(.)`Mɐ}. The utterance’s prosodic-phonetic realization is noteworthy: the noun phrase (eine andere (i)dee) is produced in a legato way, so is the predicate (kann sein) after the inbreath. The subsequent micro pause disconnects the next part of the utterance, viz. the syllabification {KLA (.) Mɐ}, which is produced in staccato with two accents, and in a hyperarticulated manner. There is a micro pause after the vowel; the first syllable is produced as an open syllable, realized with a pitch step up and a flat contour, whereas the second syllable, after the micro pause, has a falling contour. It is the prosodic design of the utterance, especially the change from legato to staccato when the target item is realized, that contextualizes doing oral syllabifying (Lingnau and Mehlem Citation2012; Kern Citation2018).

By repeating the target item, the teacher joins in the doing oral syllabifying by also producing the item with two accented syllables, thereby ratifying Carlos’ suggestion (line 262). With regard to the phonetic realization, however, the teacher’s repetition differs to some extent from Carlos’ production: The plosive is voiced; the first syllable ends with a nasal consonant, and the second syllable starts with a nasal. Thus, on the prosodic level, the teacher’s utterance features parameters quite similar to Carlos’ – parameters that seem to be decisive for utterances to be marked (and heard) as doing oral syllabifying. On a phonetic level, however, we find variation, revealing the teacher’s orientation to the orthographic norm of closed written syllables. The fact that Carlos produces the first syllable as an open syllable is noteworthy here as it is in line with the research reviewed above that children frequently do not close the pre-joint syllable.

By producing a ratification and an evaluation (line 263), the teacher treats this sequence as (possibly) closed. Carlos, however, seeks to elaborate further (wenn du/if you (unintelligible)) (line 265), which is taken up by the teacher with a similar syntactic construction (wenn man/if you) and used to explicate the operation Carlos and herself have been employing in prior turns: enunciating clearly (line 267). The teacher claims that enunciating clearly results in closing the first syllable with a nasal /m/ and starting the second syllable with the same consonant. In line 271, she makes the concession that only one /m/ is heard in regular speech, and exemplifies this in line 272 by producing the item in standard pronunciation, i.e., with the stress on the first syllable and no lengthening. Her final rising intonation can be interpreted as a turn holding signal, as the teacher subsequently continues by reorienting to the syllabifying of Klammer (line 274). Once again, the item is produced with strong accentuation and pitch movement on both syllables, in this case with hyperarticulated final syllable (this time with ʁ realization), which contributes to the joint action of doing oral syllabifying. In lines 277–278, she repeats her previous assertion that the /m/ closes the first syllable and opens the second one.

In line 280 the teacher ties back to the initially invoked criterion of vowel quantity. In 281, however, she displays an orientation to the graphematic perspective: Based on the correct spelling, she explains that because the syllable is closed, the vowel is short. She then explicates this by drawing syllable scoops below the word (lines 283f). In 287, she immediately returns to doing oral syllabifying, repeating Klammer again with an accent and strong pitch movement on each syllable, this time, however, with a 0.9s pause in between the syllables, reinforcing the impression of two segments. Here, she starts to combine the graphic operation of drawing syllable scoops and the oral operation of syllabifying, which hitherto have been separate (note how in lines 251–279 Carlos and later the teacher follow up on the teacher’s mention of syllable scooping by doing oral syllabifying only instead of scooping). This specific prosodic-phonetic design allows the teacher to ‘embed’ this utterance into her explanation of syllable boundaries as an illustration (lines 285 to 290). Subsequently, she adds another explicative aspect through weil/because (line 292) and returns to the criterion of vowel quantity. She illustrates this by producing the item with a non-target-like tense vowel and hyperarticulated final syllable (with ʁ realization) (line 294), which she subsequently contrasts with the standard realization (line 295), before closing this sequence in line 297. This time, however, she turns the argument around: Because the vowel is short, the syllable is closed with /m/, and the next syllable starts with /m/ as well.

Extract 1b contains four student realizations of the target item (lines 260, 269, 275 and 296), none of which is produced with a /m/ closing the first syllable. While Carlos’ oral syllabifying in line 260 is taken up and repaired by the teacher in line 262, the other three are produced by unidentifiable speakers in overlap with the teacher’s turns. We assume that the teacher manages to hear and discriminate those realizations since she orients to them throughout her explication. As the data further show, the recast produced by the teacher (line 262) does not result in an uptake of the enunciation pattern featuring two /m/ /’klam.mɐ/ by any of the students.

It has become obvious in the above examples from the teacher-led discussions (extracts 1a and 1b) how several operations are drawn on by the teacher and the students to explain the spelling of Klammer: the relevance of vowel quantity (lines 237 through 247, lines 292–296), the explanation based on the written form (lines 208f), the drawing of syllable scoops (lines 249 through 258, 283–290), and oral syllabifying (lines 260 through 278 and 287), whose constitutive prosodic-phonetic parameters we have described and which is explicitly labelled as enunciating clearly by the participants (line 267). This enunciating clearly, however, does not lead to a consistent way of producing the target item. On the contrary, we observed various prosodic-phonetic realizations of the two syllables. At the same time, we can observe that there is an overall orientation to a phonographic approach, accounting for spelling through the spoken form, except for interactional moments where the vowel quantity is explained and syllable scoops are drawn based on the written form (lines 280f). The data thus show that teachers and students negotiate in the course of the spelling discussion how to account for the targeted spellings of ambisyllabic consonants by drawing on more than one operation.

Our corpus contains further instances of the teacher’s combining of operations, including unsystematic syllabifying. The extract below is an example from the teacher-led discussion in session 2 concerning the <tt> in Schlitt in the compound noun Schlittschuhlaufbahn (‘ice-skating rink’, extract 2). Before the extract starts, a student extends Schlitt to Schlitten, and the students take up oral syllabifying, producing the first syllable as an open syllable: sch:lI(.)ttEn or sch:lI:(.)ttEn. Then a student (David) explains the double consonant on the basis of vowel quantity, which is ratified by the teacher before she adds the two operations ‘drawing syllable scoops’ and ‘syllabifying’:

Extract 2: Schlittschulaufbahn_tt_syllabifying

As before with Klammer, in this teacher-led discussion the students also draw on the relevance of vowel quantity to account for the spelling of the double consonant <tt> as well as on morphologic extension (prior to the extract). The teacher herself invokes the operation of drawing syllable scoops below the written word (line 374) as well as oral syllabifying (line 372 and 379), thereby combining both a graphematic and a phonographic didactic approach. Moreover, as in extract 1b, we observe rather unsystematic phonetic realizations: While in the first instance of Schlitten (line 372) the teacher closes the first stressed syllable with a /t/, making a 1.07s pause and starting the second unstressed syllable with the same consonant, in the second instance (line 379) she varies the production (with an open unstressed first syllable, a shorter pause and a stressed second syllable).

Small-group interaction on double consonant spellings in unterwasserkorallenriff

In the following three extracts from a group work session (extracts 3a, 3b and 3c), we will show how students in one group (Juan, Carolina and Lucía) achieve the task of accounting for the correct spelling of double consonants in the word Unterwasserkorallenriff by making use of various operations without any intervention by the teacher.

Extract 3a: Unterwasserkorallenriff_i

In this extract, we can observe how the students invoke the argument of vowel quantity in order to account for the double-f spelling. Juan makes this explicit (line 108) by referring to both the double f and the vowel quantity. The incorrect use of the article (das instead of der) is not treated as problematic by the participants. Juan concludes that vowel quantity must be remembered when explaining the spelling (line 110). The use of the generic pronoun man (‘one’) is suggestive of academic language use and turns this utterance into a rather depersonalized account. Taking up the idea of a short vowel /i/, Lucía exemplifies this standard pronunciation (line 112). However, there seems to be some disagreement as to whether Juan’s explanation is sufficient (shown by the negation token ?hm_hm; in line 113), so Carolina, Juan and Lucía start producing variants of the target item with contrasting vowel quantities (lines 115–119). Interestingly, producing the target item with a lengthened vowel leads to a pun realized by Lucía in line 120: She turns the target item ʀɪf into ʀi:f, which is the preterit of rufen (‘to shout’), and continues by producing loud sounds, mimicking shouting. This pun reveals Lucía’s implicit metalinguistic knowledge that vowel length is phonematically distinctive in German. This pun is, however, not oriented to by Juan, who twice starts off an explicit explanation instead (line 121), this time relating the hearing of a short vowel (line 122) to the double-f spelling (line 123) based on vowel quantity (line 124). In this extract, the students experiment with vowel quantity in a playful way. By contrasting variants, they show their ability to produce and hear tense and lax vowels, and it is Juan who makes the explicit connection to the spelling rule.

In the following extract (3b), the subsequent exchange between the three students about Korallen (‘corals’) is also contextualized as playful through the use of minimal pairs:

Extract 3b: Unterwasserkorallenriff_ll

The students produce varying prosodic-phonetic forms of Korallen. Lucía explicitly labels the <a> as a crucial vowel (line 238), which leads to Juan’s epistemic stance marker and agreement (line 241), and his production of a standard-like Korallen (line 242) so as to exemplify the vowel quantity of the <a > . The other students join in this orientation to vowel quantity by producing variants of Korallen with lengthening of the first (line 244), the second (lines 245–247) or the third syllable (line 249). It is noteworthy that no explicit reference to a spelling rule is made; the verbalization of contrasting vowel quantities seems to be sufficient for all three students to jointly account for the spelling <ll>.

In the following extract (3c), the students bring together ‘loose ends’ of their previous group work: They jointly establish syllabic speaking of <riffe> in ways that account for the spelling <ff>.

Extract 3c: Unterwasserkorallenriff_riffe

Juan orients to the item Riff (line 397), which had previously been introduced by Carolina (line 370). By producing ´RI(.)`FFE; he shows his ability to apply morphologic extension to monosyllabic nouns, and his ability to do oral syllabifying. He is even able to self-correct his production to ´RIF (-) `FE; (line 399), indicating that he recognizes that the first <f> closes the first syllable and that the second <f> starts the second syllable. Lucía orients to this production by repeating it correctly (line 401). It is noteworthy that she, like in extract 3a, playfully embeds the target item in another word: tene:RIF[(.)fe; (line 403), which indicates her metalinguistic knowledge of building composite nouns. This time, Juan and Lucía agree on how to note their explanation for the spelling on the worksheet (lines 404–409). Again, as in extract 3b, none of the students draws an explicit connection between the spelling and their playful experimenting with vowel quantity and syllables. From the students’ worksheet (), we can derive that the connection between the phonetic design and the graphematic realization is clear as the children have marked vowel laxness underneath the vowels by means of the dots they know from their der-die-das textbook. The worksheet is an ethnographic artefact that provides insights into the students’ graphic word markings: The syllable scoops drawn below <ss> and <ff> as well as the arrow for morphologic extension below <ff> are written indicators of the operations that the students have agreed on during their interaction.

It is noteworthy that here that the syllable scoops used by the students are a reproduction of the symbol for oral syllabification they know from their textbooks, and thus do not constitute graphematic markers of syllable boundaries as they are only drawn below the letters instead of entire syllables. They do, however, visualize that the phonographic operation of oral syllabifying was drawn on during the spelling discussions. This is a contrast to the teacher-led discussion, where the teacher had used syllable scoops both phonographically and graphematically to mark syllable boundaries on the written word.

As the extracts 3a through 3c have shown, in the interactional unfolding of the group work session, the children employ only the phonographic operations of contrasting vowel quantity, morphologic extension and oral syllabifying, i.e., the children account for written language exclusively on the basis of spoken language. Performing these operations seems to be sufficient for the students to achieve their task, as explicit references to spelling rules occur only once (in 3a). The data show how the students make use of these operations by playfully contrasting vowels and ably doing oral syllabifying, and one student (Lucía) shows her metalinguistic skills by producing phonetic puns. The students achieve the orthographic task, and they complete their worksheet cooperatively. As our data show, the spelling discussions demand joint communicative action on the part of the learners: Agreeing on how to account for spellings forces the students to draw on their communicative skills as well as to use and foster their language competences and awareness.

Discussion and conclusion

We will now summarize our findings and discuss them in light of the current debate on teaching ambisyllabic consonant spellings. We further seek to derive implications for teacher education from our data by discussing what we believe (prospective) (L2) German teachers need to know about a) German orthography and approaches to teaching it, and b) interactional and verbal-vocal phenomena of spelling instruction. We are aware that such seemingly normative conclusions stand in some contrast to the conversation-analytic orientation of this paper. We do believe, however, that the findings of this kind of empirical work have a great potential to improve the professionalization of language teachers and should thus be transferred over into (L2) teacher education (Huth et al. this issue; Buttlar and Weiser-Zurmühlen Citation2019).

In our data, we observed that the students and the teacher approach and jointly accomplish the task of accounting for the spellings of pre-selected words by employing various operations: drawing on vowel quantity, applying morphological extension, doing oral syllabifying, comparing phonetic minimal pairs, and marking syllable scoops. From a language didactic perspective, the operations employed are, for the most part, indicative of an orientation to the phonographic approach of accounting for spellings through the spoken form, except for a few interactional moments where the teacher exhibits her knowledge of the graphematic approach by explaining vowel quantity with syllable scoops that are based on the written form. Thus, in the spelling discussions analysed, all three didactic approaches introduced in the background section of our paper (Syllable-Analytic Method, vowel quantity and Speak-Along) are used by the teacher to account for spellings. However, none of the approaches is being explicitly oriented to or made transparent by the teacher.

We further show that the children in the group work sessions do not use syllable scoops in the graphematic sense as initiated by the teacher in Klammer; instead, they employ the scoop symbol to document their oral syllabifying. In our data, the students exclusively draw on phonographic operations (contrasting vowel quantity, morphologic extension, and oral syllabifying) to account for the spelling of words, which may be a result of the teacher’s lack of making the different approaches explicit. Our study thus sheds light on the interactional intricacies of spelling discussions, showing how the boundaries between approaches can easily blur in the course of accounting for a spelling.

Working explicitly with different didactic approaches in the teaching of orthography is assumed to support differentiating instruction as it helps establish the best fit for each student depending on their individual linguistic and orthographic abilities (Hanke Citation2002). However, the question of which problem-solving operation from which didactic approach suits which learner best has yet to be answered (ibid.). What we have observed in our data of the group-work sessions is that the students quite skillfully and even playfully draw on various operations, thereby revealing their linguistic and (meta)linguistic knowledge of L2 German orthography, phonology, morphology and semantics. Furthermore, they constantly practice their communicative skills by invoking specific operations as accounts for a spelling and by working towards agreement on the respective accounts. Based on these observations, we suggest that spelling discussions may serve as a valuable diagnostic tool for L2 teachers to tap the students’ L2 knowledge (as revealed in e.g., playing with minimal pairs, syllabic speaking or providing metalinguistic explanations). At the same time, spelling discussions may provide insights into individual students’ communicative competencies in terms of explaining or making a case for something. Prospective teachers’ diagnostic awareness of these aspects may be raised in teacher education by working with recorded instances of classroom interaction such as those shown in our data.

Another major observation in our data were the intricacies of doing oral syllabifying. We observed various prosodic-phonetic realization of the items Klammer, Schlitten, and Riffe by the participants. From the variation in the teacher’s and students’ productions, we can see that enunciating clearly is not realized in a systematic way. The basic idea of spelling discussions is, however, to use structured material to deepen the learners’ knowledge of orthographic regularities, assuming that this is most helpful for learning. The data exemplify how difficult it can be for the teacher to perceive and respond to the individual syllabifications of the children. What is more, the teacher’s syllabifications deviated from the learner’s intuitive syllabifying, with her recasts not resulting in an uptake of the targeted enunciation pattern by the students. All of these observations raise the question of whether oral syllabifying, which tries to ‘force’ features of the written language onto its oral realization, is indeed helpful – both for L1 learners’ literacy instruction in primary school (Ossner Citation2016, 150) and for L2 learners. Although the teacher-led discussions were intended to provide the learners with a model for their small-group discussions, the teacher’s prosodic and phonetic variation is unlikely to have provided suitable orientation for all learners. This is a relevant finding for orthography teaching in Germany, where most primary classrooms are rather heterogeneous with regard to the learners’ phonetic awareness (e.g., Walkenhorst and Kern Citation2017) – both in L1 and L2. In the data, we observed that some students were able to explain the double consonant spellings on the basis of vowel quantity and to build minimal pairs, but this does not mean that the phonographic approach was suitable for all of the learners.Footnote10 As Eckert and Stein (Citation2004)’s overgeneralizations of double consonant spellings (e.g. <Stuffe> for <Stufe>) showed, oral syllabifying of ambisyllabic consonants does not provide guidance in written text production/revision to all children since those who struggle with spelling also tend to syllabify unsystematically. Accordingly, in line with Buttlar and Weiser-Zurmühlen (Citation2019), extracts such as ours could be used in teacher training to help (prospective) teachers reflect on similarities and differences between spoken and written language as well as on teachers’ and students’ approaches to interactive negotiations of (meta)linguistic knowledge, ideally transferring this knowledge over into their own instruction (e.g., by playfully employing minimal pairs etc.). Our extracts from the teacher-led discussions illustrate the challenges inherent in communicating about spellings, especially when there is a discrepancy between spoken and written language, as is the case in ambisyllabic consonants. Furthermore, we suggest that dealing with extracts such as ours can help teachers reflect on the various communicative skills required for conducting spelling discussions successfully, such as asking open-ended questions to invite the children to formulate their own explanations and thus complex utterances, providing and demanding a suitable use of terminology, and reacting appropriately and flexibly to student utterances (Geist Citation2018).

In addition, we believe our findings serve to inform the theoretical-didactic debate on the effectiveness of the various approaches to teaching orthography, whose empirical basis has, for the most part, consisted in longitudinal evaluation studies of learner writing samples rather than in analyses of actual goings-on in the class (e.g., Weinhold Citation2009; Bangel and Müller Citation2018; for a meta-analysis see Funke Citation2014). Per contrast, our research, along with the interactional studies reviewed above (Kern Citation2018; Kotthoff Citation2009; Lingnau and Mehlem Citation2012; Mehlem and Lingnau Citation2012; Buttlar and Weiser-Zurmühlen Citation2019), shows how teachers and students interactively account for (their understandings of) spellings, and thus adds a valuable classroom-informed perspective to the spelling debate. Yet, further research is needed into the question of which didactic approach proves helpful for which learner. Analyzing in more detail how students orient to one approach or another in spelling discussions after having been explicitly introduced to them would be a first step into this direction.

Spelling discussions are considered problem-solving conversations about potentially challenging spellings (e.g., Budde, Riegler, and Wiprächtiger-Geppert Citation2011, 128). Our findings suggest that spelling discussions do have orthographic-didactic as well as conversation-didactic potential as they bring to the fore students’ metalinguistic competencies and provide opportunities for students’ negotiation of operations in small-group situations. However, we have also shown the interactional and prosodic-phonetic intricacies this method affords, e.g., when it comes to ((un)systematic) oral syllabifying. We therefore believe that this kind of empirical research crucially advances our knowledge of effective spelling instruction in language teaching by fruitfully complementing intervention studies such as Bangel and Müller’s (Citation2018). Further interactional research into orthography teaching should take into account more systematically the spelling competences of the students, explore further orthographic phenomena (e.g. umlaut spellings), and expand ours and Kern’s work (Citation2018) by investigating more systematically the multimodal resources used by the teacher and the students.

In conclusion, in order for teachers to be able to explain spellings, they not only need an adequate knowledge of the subject matter (Kotthoff Citation2009, 142), but also an awareness of how this subject matter can and should be imparted in classroom interaction. With regard to the spelling of ambisyllabic consonants (and various other German spelling phenomena), this means that knowledge of orthography, phonology and morphology needs to be complemented by knowledge of the various approaches to teaching orthography, including their respective linguistic foundations. Language teacher professionalization further needs to foster the teachers’ mindfulness of the interactional and verbal-vocal affordances that accompany both the introduction of specific spelling operations and their use by students in spelling discussions. We believe that it holds vital benefits for language teacher education to allow for pre-service and in-service teachers to explore – based on data such as ours – the interactional and linguistic phenomena that are inherent in teaching methods such as spelling discussions, thereby fostering the teachers’ ability to reflect on their own (possibly video-recorded) teaching practices.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their thanks to the student teacher and the students who took part in this study as well as to Leonore Fischer, Christl Langer, and Sophie Päßler for their help with the transcriptions. Furthermore, the authors would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Barbara Geist

Barbara Geist is Junior Professor of German as a Second Language at University of Leipzig, Germany. She received her PhD in German Language Teaching, with a thesis on the language diagnostic competences in primary school teachers. One of her current research interests is orthographic learning and interaction during spelling discussions.

Maxi Kupetz

Maxi Kupetz is Junior Professor of Intercultural Communication and Teacher Training in the German Department at Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, Germany. Her current work focuses on research on interactional phenomena of teaching and learning German as a Second Language in multilingual and multicultural learning settings and on case-based teacher training.

Karen Glaser

Karen Glaser is Junior Professor of TEFL in Primary School at University of Leipzig, Germany. Her research interests include teaching young learners, classroom discourse and pragmatics. She is the author of the monograph Inductive or Deductive? The Impact of Method of Instruction on the Acquisition of Pragmatic Competence in EFL.

Notes

1. A syllable-initial <h> graphematically marks the onset of a non-initial syllable, but it is not realized phonetically, as in gehen /ˈɡeːən/ (‘to go’).

2. These are consonants that simultaneously belong to two syllables and thus function as a kind of hinge between them as they form the coda of the first and the onset of the second – see below for a more detailed explanation.

3. As ambisyllabic consonants are not restricted to disyllabic words, the syllable preceding the syllable joint is not necessarily the first syllable in a word, e.g. Koralle (‘coral’).

4. Exceptions are <ck> instead of /kk/ for /k/ as in backen /ˈbakən/ (‘to bake’) as a fixed rule, and <sch>, <ch>, <ng> instead of <schsch>, <chch>, <ngng> as in Flasche /ˈflaʃə/ (‘bottle’), lachen /ˈlaxən/ (’to laugh’) or springen /ˈʃpʁɪŋən/ (‘to jump’) since di- and tri-graphs are by default not doubled.

5. As e.g. Walkenhorst and Kern (Citation2017) show with L1 and L2 German first graders, the correct spelling of double consonants is not directly related to the ability to discriminate lax and tense vowels but rather to the learners’ overall morphophonological awareness.

6. This operation features the ‘extension’ of a word whose final consonant spelling is not phonetically transparent (e.g. through final devoicing as in lieb /liːp/ ‘nice, kind’) through the addition of an inflectional morpheme (such as the plural with nouns or the comparative with adjectives) to yield a related word whose pronunciation reflects the spelling (as in lieber /ˈliːbɐ/ ‘nicer, kinder’).

7. This operation is used to deal with potentially problematic umlaut spellings in inflected words by using the root as orientation. For instance the plural Bäume (‘trees’) is traced back to the singular Baum, which tells the learner that the correct spelling must be <Bäume>, not <Beume>, both of which would be realized phonetically as [ˈbɔɪ̯mə].

8. The drawing of syllable scoops is also occasionally employed in the graphematic Syllable-Analytic Method, where, however, in contrast to the phonographic Speak-Along Method it exclusively serves to visualize systematic syllable patterns and is never accompanied by syllabic speaking (Bangel and Müller Citation2018).

9. Due to this situation, we decided to speak of a German as a Second Language instead of a German as Foreign Language setting.

10. The students start to take up the oral syllabifying with a closed first syllable in Riffe in session 3, but they did not do this in either session 1 (Klammer) or session 2 (Schlitten). One possible reason could be the growing familiarity with this way of pronouncing syllables, another the difference in the consonants (Pröll, Freienstein and Ernst Citation2016).

References

- Bangel, M., and A. Müller. 2018. “Strukturorientiertes Rechtschreiblernen. Ergebnisse einer Interventionsstudie zur Wortschreibung in Klasse 5 mit Blick auf schwache Lerner/-innen.” Didaktik Deutsch 45: 29–49.

- Barth-Weingarten, D. 2008. “Interactional Linguistics.” In Handbook of Applied Linguistics. Vol. 2: Interpersonal Communication, edited by G. Antos, E. Ventola, and T. Weber, 77–105. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Becker, T. 2011. Schriftspracherwerb in der Zweitsprache. Baltmannsweiler: Schneider Verlag Hohengehren.

- Bredel, U., N. Fuhrhop, and C. Noack. 2011. Wie Kinder schreiben lernen. Tübingen: Narr.

- Brezing, H., D. Maisenbacher, G. J. Renk, B. Rinderle, and M. Wehrle. 2018. FRESCH - Freiburger Rechtschreibschule: Grundlagen, Diagnosemöglichkeiten, LRS-Förderung in der Schule. Hamburg: AOL-Verlag.

- Budde, M., S. Riegler, and M. Wiprächtiger-Geppert. 2011. Sprachdidaktik. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

- Čekaite, A. 2009. “Collaborative Corrections with Spelling Control: Digital Resources and Peer Assistance.” Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning 4: 319–341. doi:10.1007/s11412-009-9067-7.

- Buttlar, A., and K. Weiser-Zurmühlen. 2019. “(Fach-)Unterricht untersuchen und (fach-) didaktisch reflektieren. Der Beitrag der Gesprächsanalyse zur Professionalisierung von Lehramtsstudierenden”. Herausforderungen LehrerInnenbildung (HLZ) 2 (2): 20–37. [Special Issue: Professionalisierung im Fach – Forschendes Lernen in der fachdidaktischen Lehramtsausbildung, edited by F. Kern and B. StöVesand]

- Couper-Kuhlen, E., and M. Selting. 2001. “Introducing Interactional Linguistics.” In Studies in Interactional Linguistics, edited by M. Selting and E. Couper-Kuhlen, 1–22. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Couper-Kuhlen, E., and D. Barth-Weingarten. 2011. “A System for Transcribing Talk-In-Interaction: GAT 2, Translated and Adapted for English.” Gesprächsforschung - Online-Zeitschrift zur verbalen Interaktion 12: 1–51.

- Couper-Kuhlen, E., and M. Selting. 2018. Interactional Linguistics: Studying Language in Social Interaction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Duden. 2006. Die deutsche Rechtschreibung. 24th ed. Mannheim: Dudenverlag.

- Eckert, T., and M. Stein. 2004. “Ergebnisse aus einer Untersuchung zum orthographischen Wissen von HauptschülerInnen.” In Schriftspracherwerb und Orthographie, edited by U. Bredel, G. Siebert-Ott, and T. Thelen, 123–161. Baltmannsweiler: Schneider Hohengehren.

- Funke, R. 2014. “Erstunterricht nach der Methode ‘Lesen durch Schreiben’ und Ergebnisse schriftsprachlichen Lernens: Eine metaanalytische Bestandsaufnahme.” Didaktik Deutsch 19 (36): 20–41.

- Geist, B. 2017. “Kinder in Rechtschreibgesprächen zum Austausch über Schreibungen herausfordern.” In Unterrichten als Gegenstand und Aufgabe in Forschung und Lehrerbildung, Beispiele aus der (fach)didaktischen Forschungspraxis, edited by M. Hallitzky and C. Hempel, 33–51. Leipzig: Universitätsverlag.

- Geist, B. 2018. “Wie Kinder in Rechtschreibgesprächen Schreibungen erklären und wie die Lehrperson sie darin unterstützt.” In Rechtschreiben unterrichten, Lehrerforschung in der Orthographiedidaktik, edited by S. Riegler and S. Weinhold, 111–130. Berlin: Erich Schmidt Verlag.

- Glaser, K. 2018. “Digitaler Mehrwert im Englischunterricht der Grundschule: Wortschatzerwerb mit dem TING-Hörstift.” In Lernen digital: Fachliche Lernprozesse im Elementar- und Primarbereich anregen, edited by H. Dausend and B. Brandt, 151–178. Münster: Waxmann.

- Hanke, P. 2002. “Interdisziplinäre Betrachtungen zur Bedeutung sprachlicher Strukturen beim Schriftspracherwerb.” In Schärfungsschreibung im Fokus, edited by D. Tophinke and C. Röber-Siekmeyer, 56–70. Baltmannsweiler: Schneider Verlag.

- Heritage, J. 1984. Garfinkel and Ethnomethodology. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Heritage, J. 2004. “Conversation Analysis and Institutional Talk.” In Handbook of Language and Social Interaction, edited by R. Sanders and K. Fitch, 103–147. Mahwah: Erlbaum.

- Huneke, H. 2002. “Intuitiver Zugang von Vorschulkindern zum Silbengelenk – Eine Grundlage für den Erwerb der Schärfungsschreibung?” In Schärfungsschreibung im Fokus, edited by D. Tophinke and C. Röber-Siekmeyer, 85–104. Baltmannsweiler: Schneider Verlag.

- Hutchby, I., and R. Wooffitt. 1998. Conversation Analysis: Principles, Practices and Applications. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Hüttis-Graff, P., and C. Jantzen. 2012. Überarbeiten lernen – Überarbeiten als Lernen. Freiburg: Fillibach Verlag.

- Jeuk, S., A. Sinemus, and K. Strozyk. 2012. der-die-das, Sprache und Lesen 3. Berlin: Cornelsen.

- Kasper, G., and J. Wagner. 2011. “A Conversation-Analytic Approach to Second Language Acquisition.” In Alternative Approaches to Second Language Acquisition, edited by D. Atkinson, 117–142. London: Routledge.

- Kern, F. 2018. “Clapping Hands with the Teacher. What Synchronization Reveals about Learning.” Journal of Pragmatics 125: 28–42. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2017.12.006.

- Kotthoff, H. 2009. “Erklärende Aktivitätstypen in Alltags- und Unterrichtskontexten.” In Erklären im Kontext, Neue Perspektiven aus der Gesprächs- und Unterrichtsforschung, edited by J. Spreckels, 120–146. Baltmannsweiler: Schneider Verlag.

- Kunitz, S., and K. Skogmyr Marian. 2017. “Tracking Immanent Language Learning Behavior over Time in Task-Based Classroom Work.” TESOL Quarterly 51 (3): 507–535. doi:10.1002/tesq.2017.51.issue-3.

- Leßmann, B. 2014. “Individuelle und gemeinsame Lernwege im Rechtschreiben.” Grundschulzeitschrift 28 (271): 44–47.

- Lingnau, B., and U. Mehlem. 2012. “Interaktive Entstehung von Wortschreibungen mehrsprachiger Kinder im ersten Schuljahr.” In Orthographie- und Schriftspracherwerb bei mehrsprachigen Kindern, edited by W. Grießhaber and Z. Kalkavan, 143–161. Freiburg: Fillibach.

- Markee, N., and S. Kunitz. 2015. “CA-for-SLA Studies of Classroom Interaction: Quo Vadis?” In The Handbook of Classroom Discourse and Interaction, edited by N. Markee, 425–439. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

- Mehlem, U., and B. Lingnau. 2012. “„Ah daaaaaaaaaaaa kommt ein ÄH“ – Vermittlung basaler Schreibkompetenzen in der Zweitsprache Deutsch im Unterricht der Schuleingangsstufe.” In Sprachstand erheben – Spracherwerb erforschen, edited by B. Ahrenholz and W. Knapp, 131–154. Freiburg: Fillibach.

- Mondada, L. 2006. “Video Recording as the Reflexive Preservation and Configuration of Phenomenal Features for Analysis.” In Video-Analysis: Methodology and Methods, Qualitative Audiovisual Data Analysis in Sociology, edited by H. Knoblauch, B. Schnettler, J. Raab, and H. Soeffner, 51–67. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

- Müller, A. 2010. Rechtschreiben lernen, die Schriftstruktur entdecken – Grundlagen und Übungsvorschläge. Seelze: Kallmeyer.

- Musk, N. 2016. “Correcting Spellings in Second Language Learners’ Computer-Assisted Collaborative Writing.” Classroom Discourse 7: 36–57. doi:10.1080/19463014.2015.1095106.

- Ossner, J. 2013. “Strategien im Rechtschreibunterricht kennen und anwenden.” In Deutsch, Didaktik für die Grundschule, edited by U. Abraham and J. Knopf, 97–110. Berlin: Cornelsen Scriptor.

- Ossner, J. 2016. “Didaktische Konstrukte und Konstruktvalidität in der Deutschdidaktik.” In Denkrahmen der Deutschdidatik, Die Identität der Disziplin in der Diskussion, edited by C. Bräuer, 147–167. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

- Pelchat, L. 2017. “„das wissen wir doch!“ – Analyse einer Lerner-Lerner-Interaktion zum kollaborativen Schreiben.” In Interaktion im Fremdsprachenunterricht. Beiträge aus der empirischen Forschung, edited by G. Schwab, S. Hoffmann, and A. Schön, 133–149. Berlin: LIT Verlag.

- Primus, B. 2003. “Zum Silbenbegriff in der Schrift-, Laut- und Gebärdensprache, Versuch einer mediumübergreifenden Fundierung.” Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft 23 (1): 3–55.

- Pröll, S., J. Freienstein, and O. Ernst. 2016. “Exemplarbasierte Annäherungen an das Silbengelenk.” Zeitschrift für Germanistische Linguistik 44 (2): 149–171. doi:10.1515/zgl-2016-0009.

- Reuter-Liehr, C. 2008. Lautgetreue Lese-Rechtschreibförderung, Band 1. Bochum: Verlag Dr. Dieter Winkler.

- Risel, H. 1999. “Können Kinder Wörter problemlos in Silben gliedern?” Der Deutschunterricht 4: 87–90.

- Risel, H. 2002. “Zur Silbierkompetenz von Grundschulkindern.” In Schärfungsschreibung im Fokus, edited by D. Tophinke and C. Röber-Siekmeyer, 71–84. Baltmannsweiler: Schneider Verlag.

- Röber, C. 2009. Die Leistungen der Kinder beim Lesen- und Schreibenlernen, Grundlagen der Silbenanalytischen Methode. Baltmannsweiler: Schneider Verlag.

- Schröder, E. 2014. “Über Fehler sprechen, Schreibungen untersuchen lernen.” Praxis Deutsch 248: 24–30.

- Seymour, P. H. K., M. Aro, and J. M. Erskine. 2003. “Foundation Literacy Acquisition in European Orthographies.” British Journal of Psychology 94 (2): 143–174. doi:10.1348/000712603321661859.

- Sidnell, J. 2010. Conversation Analysis. An Introduction. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Sommer-Stumpenhorst, N. 2015. Rechtschreibwerkstatt. Accessed 22 March 2019. http://www.rechtschreib-werkstatt.de/rsw/html/haus.html

- Stoewer, K. 2018. English Hemspråk. Language in Interaction in English Mother Tongue Instruction in Sweden. Linköping: Linköping University Electronic Press. http://liu.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1265350&dswid=−7205

- Walkenhorst, A., and F. Kern. 2017. “Auditive Wahrnehmung und Schreibentwicklung bei ein- und mehrsprachigen Kindern.” In Der Erwerb schriftsprachlicher Kompetenzen, Empirische Befunde–Didaktische Konsequenzen–Förderperspektiven, edited by I. Rautenberg and S. Helms, 198–226. Baltmannsweiler: Schneider Verlag.

- Walsh, S., and L. Li. 2016. “Classroom Talk, Interaction and Collaboration.” In The Routledge Handbook of English Language Teaching, edited by G. Hall, 486–498. New York: Routledge.

- Weinhold, S. 2009. “Effekte fachdidaktischer Ansätze auf den Schriftspracherwerb in der Grundschule.” Didaktik Deutsch 27: 52–75.

Appendix 1.

Question fan deck

Table A1. Instructions provided in the question fan deck.