ABSTRACT

In a bilingual school, the linguistic and semiotic resources of students who speak one, two or several languages can be used in classroom discourse in order to embrace and strengthen the multiplicity of voices and languages in teaching and learning. In this article, four English language lessons – where the medium of instruction mainly oscillates between Swedish and English, and where Spanish is also used – are analysed with the aim of generating knowledge about how translanguaging is or could be used as a pedagogical resource in the classroom. The data were collected through ethnographic fieldwork in a 5th grade class at a bilingual school in the Stockholm area and consist of recordings of classroom observations, photos and field notes.

Introduction

In a bilingual school, the linguistic and semiotic resources of students who speak what could be conceived as one, two or several languages can be used and exploited in classroom discourse in order to embrace and strengthen the multiplicity of voices and languages in teaching and learning. In this article, four English language lessons – where the medium of instruction mainly oscillates between Swedish and English, and where Spanish is also used – are analysed with the aim of generating knowledge about how translanguaging is or could be used as a pedagogical resource in the classroom.

The research questions are a) how do students and their teacher use linguistic and semiotic resources during English language lessons; b) what opportunities of translanguaging as pedagogy for language learning exist during these lessons; and, finally, c) what can visual aspects of the classroom reveal about language use and translanguaging?

The data were collected through ethnographic fieldwork in a 5th grade classroom at a bilingual school in the Stockholm area and consist of recordings of classroom observations, photos, and field notes.

In bilingual education in Swedish compulsory schools, a language other than Swedish may be used up to 50% of the time for students who use a language other than Swedish with at least one of their guardians daily (Grundskoleförordning Citation1994, 1194; Förordning Citation2003, 306 om försöksverksamhet med tvåspråkig undervisning i grundskolan). In addition, between 2003 and 2011 the Swedish Government allowed bilingual education in English in compulsory schools for trial purposes (Förordning Citation2003, 459 Om försöksverksamhet med engelskspråkig undervisning i grundskolan). In Sweden, monolingual schools are still the norm, but it is becoming increasingly common for schools to portray themselves as ‘international’, which in practice means that English is used alongside Swedish as a medium of instruction. There are also several bilingual schools where Swedish and Finnish are used.

Despite the fact that around 200 languages are spoken in Sweden (The Institute for Language and Folklore Citation2019), and despite different initiatives that have been taken to support the multilingual reality in Sweden, such as the Language Act (Citation2009), monolingual norms still strongly prevail in Swedish society (cf. Blackledge Citation2008). These norms are also present in bilingual schools (e.g. Jonsson Citation2013) where languages are separated following the tenets of ‘parallel monolingualism’ (Heller Citation1999) or ‘separate bilingualism’ (Creese and Blackledge Citation2010), or according to a ‘double monolingualism norm’ (Jørgensen Citation2008). In education, however, it would be possible to opt for a multilingual approach where translanguaging practices could be used for ‘language learning and teaching’ as well as for ‘identity performance’ (Creese and Blackledge Citation2010, 112).

The article begins by introducing the theoretical framework of the study: communicative repertoires (Rymes Citation2010), language norms (Jørgensen Citation2008), translanguaging (García Citation2009; García and Li Citation2014), and translanguaging space (Li Citation2011). Thereafter, the methods and data are briefly described. This is followed by a description of the students’ and the teacher’s communicate repertoires, after which the results and analysis are presented. The article concludes with a discussion.

Communicative repertoires

The notion of communicative repertoires (Rymes Citation2010) as well as Gumperz’ notion of linguistic repertoires (eg. Busch Citation2012) emphasize that people’s linguistic and semiotic funds of knowledge can be seen as a togetherness, or as ‘a whole’ (Busch Citation2012, 521). In doing so, these concepts depart from the view of languages as bounded entities and instead highlight the fluidity between languages. The idea of a repertoire, therefore, fits well with the concept of translanguaging.

Rymes (Citation2010, 528) defines communicative repertoires as ‘the collection of ways individuals use language and literacy and other means of communication (gestures, dress, posture, or accessories) to function effectively in the multiple communities in which they participate’. Dialects, languages, and registers make up a person’s communicative repertoire, together with different multimodal means of expression such as signs and emoticons. In meaning-making, language is entangled with other semiotics (Lin Citation2019, 5, cf. Hawkins and Mori Citation2018, 3). The concept of a repertoire can, according to Blommaert and Backus (Citation2011, 3), be used to describe:

all the “means of speaking” i.e. all those means that people know how to use and why while they communicate, and such means … range from linguistic ones (language varieties) over cultural ones (genres, styles) and social ones (norms for the production and understanding of language). (Italics in original)

As for linguistic competences, these can also include any ‘linguistic features’ (Jørgensen Citation2008) that a person may know. This means that if a person learns a new word in a language that is new to that person, the new word is added to the person’s repertoire. This is in line with Rymes’ (Citation2014, 250) description of a person’s repertoire as ‘something like an accumulation of archeological layers’. She argues that ‘As one moves through life, one accumulates an abundance of experiences and images, and one also selects from those experiences, choosing elements from a repertoire that seem to communicate in the moment’ (p. 250). A person can thus add elements to their repertoire but also choose which elements to preserve and use in their communication with others.

In what follows, the concept of communicative repertoire will be used to refer to all the linguistic, cultural, and social resources described above. The term ‘communicative repertoire’ was selected since it, more directly than ‘linguistic repertoire’, signals that it is not only linguistic elements that make up a person’s repertoire. The term ‘communicative repertoire’ will be used as an umbrella term to also encompass the meaning of ‘linguistic repertoire’.

In relation to translanguaging, Li (Citation2018) writes that ‘Translanguaging is using one’s idiolect, that is one’s linguistic repertoire, without regard for socially and politically defined language names and labels’ (p. 19; cf. the use of idiolects in Otheguy, García, and Reid Citation2015, 289). In this study, I propose that besides acknowledging the repertoires of the individual students and the repertoire of the teacher, the repertoires of the students and teacher can also be seen as a joint repertoire that can be used as a fund of knowledge in translingual classroom discourse.

Language norms

Jørgensen’s (Citation2008) four language norms – the monolingualism norm, the double monolingualism norm, the integrated bilingualism norm, and the polylingualism norm (see also Spindler Møller and Jørgensen Citation2009) – are useful in the discussion of classroom discourse.

As apparent by the labels monolingualism norm and double monolingualism norm, these norms start with the assumption that monolingual linguistic behaviour is the ‘ideal’. Speakers should, according to these norms, use ‘only one language at a time’ (Citation2008, 168; cf. the monolingual bias, Block Citation2003). In bilingual education, double monolingualism norms, ‘parallel monolingualism’ (Heller Citation1999), or ‘separate bilingualism’ (Creese and Blackledge Citation2010) are common.

With respect to the labels integrated bilingualism norm and polylingualism norm, both embrace bilingual language use in suggesting that ‘features from different languages’ (Citation2008, 168) can be used in a more integrated manner. Whereas the integrated bilingualism norm focuses on the ‘two (or three or more) languages which the speaker commands’ (Citation2008, 168), the polylingualism norm includes the use of all languages that a speaker has access to, irrespectively of whether a speaker has mastered the language or merely knows a word or two of it.

In relation to the data analysed in this study, the double monolingualism norm and the integrated bilingualism norm prove particularly relevant.

Translanguaging and translanguaging space

Translanguaging is described by Canagarajah (Citation2011) as ‘the ability of multilingual speakers to shuttle between languages, treating the diverse languages that form their repertoire as an integrated system’. This definition emphasizes the integratedness of speakers’ communicative repertoires. As I have written elsewhere (Jonsson Citation2017), the notion of translanguaging offers several advantages in the description of multilingual language practices. By moving the focus from language(s) to speakers and by moving away from regarding languages as bound and stable entities to viewing languages in a more fluid manner (García Citation2009, 45–47), translanguaging offers the possibility of studying bilingual and multilingual language practices from a perspective that is not monolingual and that recognizes the heteroglossia inherent in bilingual and multilingual dialogue (Jonsson Citation2017). Heteroglossia ensures that:

At any given time, in any given place, there will be a set of conditions – social, historical, meteorological, physiological – that will insure that a word uttered in that place and at that time will have a meaning different than it would have under any other conditions. (Bakhtin Citation1981, 428)

In addition to the aforementioned advantages, translanguaging practices can be used not only to facilitate communication but also to ‘construct deeper understandings’ (García Citation2009, 45). Language practices of multilinguals ‘simply reflect greater choices, a wider range of expression than each monolingual separately can call upon’ (García Citation2009, 47), and include both linguistic and cultural knowledge. By combining both linguistic and cultural knowledge, translanguaging practices offer possibilities ‘to exploit subtle linguistic and cultural nuances both within and across “languages”’ (Jonsson Citation2017, 30). Last but not least, by moving from a monolingual lens to a multilingual lens, translanguaging offers the possibility of contributing to ‘an ideologically significant epistemological change in linguistics’ by ‘resisting and transforming power asymmetries’ (Jonsson Citation2017, 30). In the context of the four English lessons that were analysed to make up the data included in this paper, translanguaging is a useful concept since it is neither easy nor always possible to determine in what language the classroom dialogue is taking place at a certain point in time.

Despite subscribing to a view of languages as ideological constructions (Blommaert and Rampton Citation2011, 4), and adhering to the view that ‘“a language” … may be important as a social construct, but it is not suited as an analytical lens through which to view language practices’ (Blackledge and Creese Citation2014, 1), the labels of different languages – English, Swedish, Spanish – will be used in what follows since such labels are entrenched and used in the school setting, e.g. in schedules, in meetings, in teaching, and in the classroom discourse of students and teachers. However, in the analysis of translanguaging one ‘transcends the named language’ (Otheguy, García, and Reid Citation2015, 297).

In the analysis of translanguaging practices, multimodality also plays a central role since in translanguaging all types of ‘meaning-making modes’ are included (García and Wei Citation2014, 29). Wei (Citation2018) writes that ‘Translanguaging reconceptualizes language as a multilingual, multisemiotic, multisensory, and multimodal resource for sense- and meaning-making’ (p. 22). Lin (Citation2019), on the other hand, makes a distinction between translanguaging and what she refers to as ‘trans-semiotizing’ which includes, for instance, facial expressions, gestures, body movement, and visual images (p. 8, 11). In any case, it is clear that linguistic and semiotic resources are integrated and entangled (Hawkings and Mori Citation2018, 3). In this study, multimodal aspects are entangled with linguistic resources, for instance, in the textbook, in a school desk, and on the board of the classroom.

The practice of translanguaging can create a ‘translanguaging space’ – where the people who communicate can combine ‘different dimensions of their personal history, experience and environment, their attitude, belief and ideology, their cognitive and physical capacity into coordinated and meaningful performance’ (Wei Citation2011, 1223). A translanguaging space is, just like translanguaging itself, ‘transformative in nature’ (Zhu, Li, and Lyons Citation2017, 412) and can therefore encourage and incite ‘new configurations of language practices as well as new subjectivities, understandings and social structures’ (ibid.).

The notion of translanguaging space is useful in the analysis of classroom discourse since a translanguaging space can both be created ‘by and for Translanguaging practices’ (Hua, Wei, and Lyons Citation2017, 412). This is understood here as a twofold process where 1) by using translanguaging practices in a classroom the teachers and students can create a translanguaging space, and where 2) members of the school board, teachers, and students can plan for and create a language policy in the school that opens up for translanguaging practices. According to Garcia and Li (Citation2014), a translanguaging space in education creates the possibility of going between and beyond languages, which, as a result, constitutes a challenge to old educational structures and potentially generates new understandings.

Method and data

The data for this study were collected through ethnographic fieldwork at a bilingual school in the Stockholm area through classroom observations, interviews, focus group discussions, language diaries, field notes, photographs, etc. More specifically, the data were collected during the 2010 fall term and the 2011 spring term, and consist of four English language lessons in a 5th grade class. Three of these four lessons were observed, audio recorded, and later transcribed; one lesson was only observed. There are field notes of all four lessons; some of these include illustrations of drawings that were made on the board. Photos also constitute the data for this study. See : Data.

Table 1. Data

In addition to the primary data mentioned above, an audio-recorded interview of 26 minutes with the teacher Karin, recorded in 2006, is used for background information about one of the participants. This interview was conducted as part of an earlier research project conducted at the same school.Footnote1 Collecting data at the same school in two research projects allowed for a more longitudinal approach. Other data was also accessed in order to give contextual information about the school and to broaden the discussion.

The school and its language policy

The school where the data were collected is a small independent Swedish- and Spanish-medium school in the Stockholm area. At the time of the investigation, the school offered education from pre-school class to fifth grade. The language policy of the school centres on the notion of bilingualism since the school, in addition to the Swedish curriculum, offers classes in Spanish.

Since the school was launched, its language policy has gone through some major changes. For instance, in the beginning it was emphasized that the school was Swedish and that it offered lessons in Spanish. Spanish was referred to as the school’s ‘profile’. However, as time went by, the teachers and the school board started reflecting on whether it was in fact appropriate to refer to Spanish as the school’s profile or if, rather, it was bilingualism in Swedish and Spanish that was the school’s profile. This topic was discussed, and the change into bilingualism as the school’s profile was implemented in the school’s language policy. At the time that this study was conducted, the school portrayed itself as a bilingual and international school (in, for instance, policy documents and in interviews conducted with some of the teachers and members of the school board). On the school’s web page, the school was described as a Swedish compulsory school with a bilingual profile in Swedish and Spanish (web page, accessed November 11th, 2011). The wording ‘Swedish compulsory school’ in the description seems to indicate that the school felt a need to emphasize its status as a Swedish school.

In the independent school where this study was conducted, Spanish was only scheduled to be used during three lessons per week (fall term 2010 – spring term 2001). All in all, Spanish, which is a mother tongue for some students at the school and a foreign language for others, was allotted 245 minutes per week. This figure can be compared to English, which is regarded as a foreign language, and which was allotted 160 minutes per week. The rest of the curriculum was conducted in Swedish.

During the lessons in Spanish, the students work with different subjects, e.g. Mathematics, Science and Social Studies. This means that the Spanish lessons are not Spanish language lessons per se but rather lessons in different subjects taught through the medium of Spanish. This is not the case for Swedish and English, which are both studied through language lessons. In addition to its use during Swedish language lessons, Swedish is also used in all other subjects, e.g. Mathematics, Science, Social Studies, Physical Education, Crafts, Art, Sports, and Music.

At the school, generally, the teachers who teach in Spanish also speak Swedish, whereas the teachers who teach in Swedish do not necessarily speak Spanish (or speak only limited Spanish). This can be seen as a sign of inequality that exists in the school, which reflects the status of Swedish and Spanish in Swedish society as well as the ‘parallel monolingualism’ (Heller Citation1999) or ‘double monolingualism norm’ in the school (Jørgensen Citation2008).

Besides having ideological consequences, such as legitimizing the status of these languages also in the school environment, this can have pedagogical implications. Whereas the teachers of Spanish can use the Swedish language as a pedagogical resource, for instance, to explain the meaning of words, connotations of words, subtle differences between words, etc., the teachers of Swedish cannot, to the same extent, use Spanish as a pedagogical resource. In order to more thoroughly explore the potential of translanguaging as pedagogy for language learning, it is necessary for teachers and students to share communicative repertoires. A teacher at the school told me that, in her opinion, competences in both Spanish and Swedish should be required when recruiting and hiring new teachers at the school (Field notes). Such a policy would contribute to creating a shared communicative repertoire among teachers while, at the same time, signalling that the two languages are equally valued at the school. In a study, Varghese (Citation2004) highlights the importance of discussing the professional roles of bilingual teachers, and of negotiating expectations on bilingual teachers during teacher training. In such discussions, the advantages of a shared communicative repertoire and an understanding of how to compensate for the lack of a shared communicative repertoire could be central themes.

The participants and their communicative repertoires

Out of the 14 students in the 5th grade class who were part of the study, 6 were girls and 8 were boys. The students had different cultural and linguistic backgrounds. Some were born in Sweden; others abroad. The students had Swedish, Spanish or other languages as their first language.

The teacher, Karin, was born in Sweden and reported speaking ‘Swedish, English and very little Spanish’ (Interview). At the time of the interview, she had worked as a teacher for 20 years, 2 of these years at a Scandinavian school in Spain where she used Swedish as the medium of instruction. Before moving to Spain, she did not speak any Spanish but in Spain she attended a beginner’s course in Spanish arranged by the school. Afterward, she attended additional Spanish classes. Karin reported languages being her ‘weak side’ (interview) and defined herself, rather, as a ‘Maths person’ (ibid.). At the time of the interview, she taught Swedish and Math at the school. Later she also added English.

The pseudonyms used in the extracts were chosen by the informants.

The classroom environment

With respect to visual aspects in the classroom, the signs in the classroom were in Swedish and/or Spanish, and sometimes – but less often – in English. In the classroom, signs and other types of texts were rarely produced bilingually in Swedish and Spanish, or what Sebba (Citation2012) calls ‘parallelism’, i.e. using ‘twin texts’ in different languages. Instead, some texts were in Swedish, while others were in Spanish or English. This is what Sebba (Citation2012) refers to as ‘complementarity’. In what follows, I will give a glimpse into the visual aspects of the classroom during one lesson (English language lesson, May 23rd, 2011).

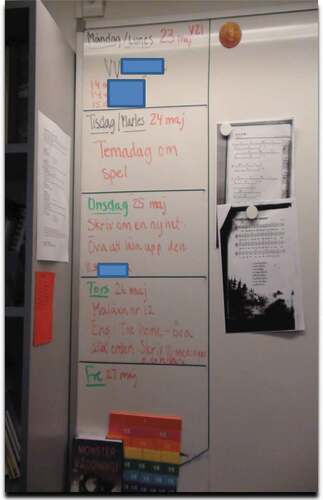

The photo below shows the left part of the classroom board where someone had written the weekdays, first bilingually (Swedish first, followed by Spanish). As time passed, some weekdays in Spanish (Wednesday-Friday) were erased from the board and only the Swedish words/abbreviations for these weekdays remained. When I took this photo, the teacher Karin looked at the board and said that the weekdays had been written in two languages originally and that it was a pity that I took a photo that day when not as much had been written in two languages (Field notes). The photo was taken in Karin’s classroom, and since she had not mastered Spanish it was possible that she might need assistance (e.g. by asking a teacher of Spanish or by using a dictionary) in writing the terms again in Spanish. Perhaps that is why some of the weekdays were left untranslated. Besides two weekdays written in Spanish, and two words in English (‘The home’, which was the chapter in the English textbook that they were working with in class), the rest of the text was in Swedish. Next to the calendar of the week, two papers with music lyrics in Swedish were posted on the board. In this part of the board, languages were kept separate – parallel or complementary. In this classroom context where Karin – the students’ primary teacher – works, the dominant language on the board seems to be Swedish. It is in this classroom that her students spent most of their classroom time .

During the lesson when this photo was taken, Karin drew a big square in the middle of the board, under the heading of ‘My room – home’, to represent a room. As the lesson went on, Karin filled this imagined room by drawing pieces of furniture that the students suggested as part of the exercise. Here the linguistic resources, i.e. the words that the students offered, were transformed into semantic resources, i.e. images on the board.

On the right-hand side of the board, Karin had written an agenda of the day. This agenda was written monolingually, in Swedish, and looked as illustrated below. The multimodal aspects consisted of an underlining of part of the date and a smiley face.

Extract 1:

Mån 23 maj <Mon 23 May>8 30 Sv <Sw>10 Rast <Break>10.20 En Ma12 Lunch/rast <break>12.40 SO <social sciences>14 Slut! <The end>

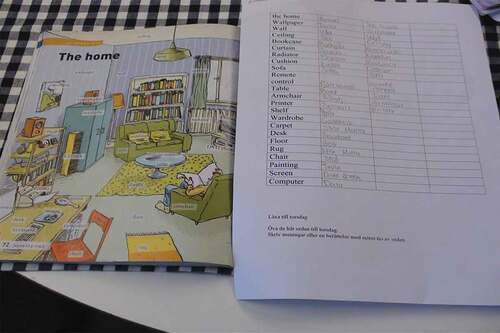

During the lesson, Karin wrote on a big piece of paper (similar to that from a paper roll) attached directly to the wall, on the right-hand side of the board. Under the heading ‘The home’, she wrote a list of English words towards the left side of the paper (‘wallpaper’, ‘wall’, ‘ceiling’ etc.) and then called students by their names and had them suggest Swedish translations that she then wrote towards the right side of the piece of paper. This exercise is one of parallel monolingualisms, emphasizing the separateness of the languages by writing them in different columns.

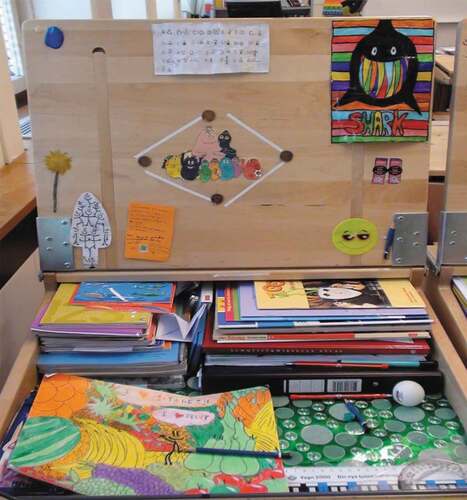

By peeking into some students’ desks that same day, the contents and the decorations provided an indication of how Spanish, Swedish, and English were used by students. One desk contained, for instance, books in two languages: a math book in Swedish and a reading book in Spanish. In the desk in , there were books, papers, and a binder. There was also a drawing in which multimodal resources were used; besides drawings of fruits, vegetables, and a smiling stick figure, letters and hearts were also used, in composing the message ‘I ♥ vegetables’ and ‘I ♥ fruit’. Using a heart in this manner is a way in which to translanguage not only across languages but also with semiotic resources such as symbols (see García & Li Citation2014, 34).

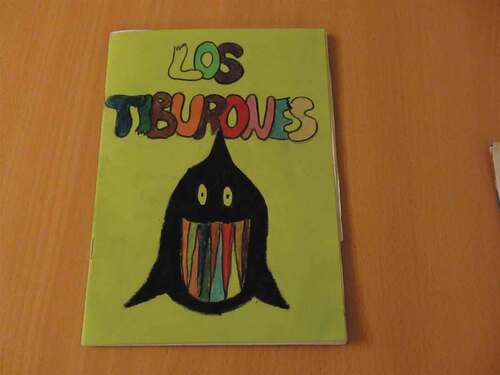

On the lid of the desk, there was a drawing of a shark with the English word ’SHARK’ in capital letters. In other data from this project, there is another almost identical drawing of a shark that this particular student had done for a school project in Spanish. On that drawing, she had written the word ‘LOS TIBURONES’ in Spanish, marking the letters L, I, and E as if they had been bitten by a shark. Linguistic and semiotic resources were entangled in her drawing to create a visual effect. .

On the lid of the desk, there was also a note where the letters of the Swedish alphabet (A-Ö) had been written. In between each letter, there was an emoticon suggesting that this is a secret alphabet where each emoticon stands for a letter.

The desk revealed that languages can be used in parallel as well (if the two images of the shark are included), but also that language resources are used in a creative translanguaging mode, too, as in the messages ‘I ♥ vegetables’ and ‘I ♥ fruit’, as well as in the emoticon alphabet. Thus, there are some differences between the signs that were on the board and the drawings in a student’s desk. The visual aspects of the classroom during this lesson illustrate what could possibly be regarded as missed opportunities for translanguaging, since the translanguaging space that the teachers and the students can and do create together is not visibly expressed in the classroom landscape.

Parallel monolingualisms and translanguaging in English language lessons

The analysis shows that most texts and teaching materials, as well as the teacher’s text on and around the board, were monolingual or written as parallel monolingualisms – cf. monolingualism or double monolingualism norm (Jørgensen Citation2008). The classroom talk, on the other hand, was more translingual in nature, although it also included parallel monolingualisms. Translanguaging was a practice employed continuously by the teacher in which the students were included. As teacher, Karin had the power to decide when and how translanguaging was used, and when it was not used. At times, she used language policing practices (cf. Amir and Musk Citation2013) to make the students use the target language English, e.g. ‘Can’t you say it in English?’ (English language lesson May 23rd, 2011), whereas at other times she allowed for comparisons not only to Swedish, but also to Spanish. This happened, for instance, during an activity in which the students were working with new words in English and the task was to translate these to Swedish, as well as when the teacher turned to a particular student and gently said that he could translate into Spanish ‘och du kan skriva på spanska’ (‘and you can write in Spanish’; English language lesson May 23rd, 2011). Overall the labels of languages, especially ‘Swedish’ and ‘English’, were used frequently during the lessons.

The teacher moved in and out of different linguistic resources as she talked about the monolingually oriented English textbook (which includes, e.g. Swedish glossaries) with the students. She explained the text, and translated and glossed the words. The Four English language lessons were highly textbook dependent. In her lessons, Karin oriented to these legitimized monolingual school texts by using different linguistic and semiotic resources. Thus, translanguaging can be seen as a way in which to ‘unpack the meaning of text’ (Martin Citation1999, 50).

During the observed English language classes, the uses of translanguaging included: translanguaging as translation, translanguaging for explanation, translanguaging to reaffirm focus on the English language, and translanguaging between speakers who use different languages. Overall, languages were used as resources to ensure mutual understanding but also to support the students’ learning by, for instance, encouraging students to make connections between the languages that constitute their linguistic repertoires. The results presented in the sections below illustrate how the teacher attempted in different ways to build on the knowledge that the students already have and that they bring to the class. By using the students’ linguistic and semiotic resources in an entangled and integrated manner in education in order to make connections between the knowledge students already have and the knowledge they are working to obtain, a translanguaging pedagogy builds on, supports, and develops the ‘continuous (rather than binary, discrete), expanding, holistic repertoire of students’ (Lin Citation2019, 12).

Translanguaging as translation

Translanguaging for translation was often used by Karin in the English language class for explanation and clarification. Translations are acts ‘of communication in which an interaction in one code is re-produced in another code’ (Creese, Blackledge, and Hu Citation2018, 842.). Translation, especially according to more recent definitions of the term, can be related to translanguaging in that these are both social practices that ‘stress the permeability of boundaries’ (Creese, Blackledge, and Hu Citation2016, 4–5). Translanguaging and translations also have in common that they emphasize issues of agency as well as the importance of determining ‘what the “code” is through the analysis process rather than assuming it is linguistically determined a priori’ (ibid.).

Extracts 2–3 provide some examples of how translanguaging for translation was used by the teacher. These translations serve the function of offering a chance for everyone to understand what is being said (irrespective of whether or not a student understands the English version) and a chance to hear the message again, i.e. repetition (even if the student understood the English version). The translations hold the potential of giving emphasis to what has just been said, by saying it twice. Repetition is central to all teaching, and here it occurs through the medium of two languages. In Extract 2, Karin, after having sung with the class, wants the students to open the textbook to a certain page.

Extract 2:

Karin: Page seventy-six, sidansjuttiosex allihopa, sidan sjuttiosex <page seventy-six everyone page seventy-six> pageseventy-six, seventy-six (English language lesson, Sept. 20th,2010).Footnote2In Extract 3, Karin first gives information in English and then translates it all to Swedish. This is a frequent strategy that she uses in an attempt to make it possible for all students to understand.

Extract 3:

Karin: In Stockholm, it’s about one million and, if you countwith all the surroundings around Stockholm, then it’s abouttwo million. I Stockholm så bor det en miljon i själva stadenStockholm men om man räknar med alla förorterna runtomkringhela Stockholms län då är det ungefär två miljoner <Onemillion [people] live in Stockholm, in the city of Stockholm, but if you count all the suburbs around Stockholm County, then it is about two million> (English language lesson, Jan. 17th,2011).Translanguaging – building on previous knowledge

Frequently, Karin changed the medium of instruction into Swedish when she wanted to explain something in greater detail. In Extract 4, she first uses translanguaging as translation and then continues using Swedish to explain what she has just said in more detail. Karin explains the difference between Great Britain and the United Kingdom.

Extract 4:

Karin:And take away Northern Ireland and you have GreatBritain. Ta bort, ta bort Norr Nordirland [xxx] då har duGreat Britain <take away, take away Nor Northern Ireland [xxx] then you have Great Britain> Det är lite konstigt att hållareda på två saker, när man säger United Kingdom då menar manalla de där fyra, säger man Great Britain menar man de här tre<It is a bit odd keeping track of two things, when you sayUnited Kingdom then you mean all those four [shows on map], ifyou say Great Britain, then you mean these three> (English languagelesson, Sept. 20th, 2010).In Extract 5, Karin and her class are choral reading new English words when Karin stops to highlight the difference between how the word ‘isles’ is pronounced and how it is spelled. In the middle of her explanation, several students go back to the practice of choral reading when Karin says the word ‘isle’ and ‘isles’.

Extract 5:

Karin: islesClass: islesKarin: det är lite svårt att säga, en ö heter <it is a bit difficult to say, an island is called> isleSeveral students: isleKarin: då det är flera öar blir det <when it is severalislands it becomes> islesSeveral student: islesKarin: men det stavas <but it is spelled> is-les [pronouncesthe word as if it were a Swedish word] ser ni det? <do yousee?> Det där i <That i> [corrects herself] s:et säger maninte utan man säger <s you don’t say but you say> isles(English language lesson, Sept. 20th, 2010).Karin emphasizes to the class that the word ‘isles’ is spelled with a silent ‘s’. In order to make this clearer for the students, she pronounces the word as if it were a Swedish word ‘is-les’, i.e. she uses their knowledge of Swedish as a resource. She then goes back to choral reading the next word on their list.

Translanguaging for literacy skills, such as spelling, is used three times during the choral reading. The two other times, Karin interrupts the choral reading to talk about words (‘English’ and Welsh’) that in English are written with an initial capital letter, whereas this is not the case in Swedish. In Extract 6, the example with Welsh is illustrated.

Extract 6:

Karin: WelshStudents: WelshKarin: alla de här, när man säger att, på svenska ser ni såskriver man med liten bokstav <all these, when you say that,in Swedish you see that one writes with a small letter>[truncated]så om jag säger <so if I say> ’I’m Swedish’ då skriver jag<then I write’> Swedish’ med stort s <with a big [i.e. capital]s>Student: swue, swi [makes different sounds as if trying topronounce the word ‘Swedish’]Karin: I’m SwedishStudent: Sweeeeden [pronounces ‘Sweden’ in an exaggerated manner with a (stereo)typical Swedish accent of English]Karin: men på svenska skriver man bara ’jag’ med stort fördet är första ordet, jag är svensk men det är med stor bokstavpå engelska <but in Swedish one only writes ’I’ with a big[letter] because it is the first word, I am Swedish but it iswith a big letter in English> (English language lesson, Sept.20th, 2010).Extracts 5 and 6 both show how the teacher used translanguaging to make comparisons between spelling in the two languages. This is a way in which to build new knowledge of English on at least parts of the linguistic knowledge that (some of) the students have, as part of their communicative repertoires, and bring to the class. This is one way to build on the students’ ‘expanding, holistic repertoire’ (Lin Citation2019, 12). In extract 6, we also see an interesting example of translanguaging where a student jokingly pronounces ‘Sweeeeden’ in an exaggerated manner with a (stereo)typical Swedish accent of English. This can be seen as a creative and critical way of using linguistic resources. Creativity and criticality are two aspects that are interrelated and inherent in translanguaging (Wei Citation2011, 1223).

The teacher as learner and the student as expert

Karin regularly used her limited knowledge of Spanish to address and include students. For instance, in Extract 7, she addresses a particular student in Spanish in order to show that the information she is sharing also concerns him. Before this comment, she had been informing the class in a serious manner of the rules of what they were or were not allowed to do during short breaks when they had to stay inside (during longer breaks, they all played outside). The rules included, for instance, not running in the corridor and not unlocking toilet doors when someone was in the toilet. These rules were to be followed by all students, and Karin turns to a particular student here and says ‘es para tu también’ (it is for you also), whereupon another student corrects her Spanish, since the correct usage in Spanish would be ‘es para ti también’ – after a preposition such as ‘para’, the form ‘ti’ is required.

Extract 7:

Karin: es para tu también <it is for you also>Juan: ti <you> (English language lesson Sept. 20th, 2010).Karin’s choice of Spanish here is an efficient way of addressing this particular student and of also possibly drawing his attention to the matter that is being discussed, but by using a language she has not mastered Karin exposes herself to corrections such as these. This affects the teacher-student relationship where the teacher, typically seen as the expert, becomes the learner. At the same time, the teacher also shows the students that learning a language is a complex process in which all people make errors. She thus puts herself in the same situation as the students in this particular class, who all are learning English, as well as with some students who are learning Spanish or Swedish. By correcting the teacher’s Spanish, Juan can be regarded as an expert, who through his knowledge is able to correct and guide the teacher in her learning of Spanish.

After being corrected, Karin turned to the student that she was addressing and asked him in Spanish if he understood – ‘entiendes?’ (‘do you understand?’). She then turned to the class and asked if someone could say the same thing in Spanish. Edward, seemingly jokingly, began to saying something in Italian, but then Eric, whose first language was Spanish, translated her words as ‘no puedes abrir los baños cuando alguien está en el baño’ (‘you can’t open the bathrooms when someone is in the bathroom’). The student being addressed by the translation sensed that he was being accused of having committed this offense and said in Spanish ‘no fui yo’ (‘it wasn’t me), which was later found to be true. In this case, the matter that was being discussed had nothing to do with learning English but dealt with a disciplinary issue. Translanguaging and translations were used in order to ensure that a mutual understanding was reached. In asking the students to translate, the teacher was calling upon their knowledge, yet again making them experts in the matter and changing the dynamics of teacher-student relationship. Before starting on the topic of the day, Karin turned to me and commented that it was difficult for the students to not know Swedish and that she believed it to be an advantage to learn English through Swedish (Field notes). The books used in the English language class were written in such a manner that English is learned through Swedish. While Karin said that she believed this to be an advantage, she regularly used Spanish to scaffold her lessons.

Moving on to another example in the activity illustrated in Extract 9, the teacher asks the students how to say the word ‘printer’ in Spanish, thus attempting to use a language that she does not master as a pedagogical resource in her teaching. This example differs from the examples above in that, here, the students are invited to draw more actively on their different linguistic resources. Whereas in Extracts 2–3 it was the teacher who offered translations, here it is the students who are asked to produce translations. This also has possible consequences for levelling the teacher-student relationship.

The activity illustrated in Extract 9, builds on a page in the English textbook, Image 4 (to the left) and a teacher-produced exercise (, to the right). The exercise is based on a list of English words that the students were supposed to translate to Swedish and then back to English, and finally back to Swedish again. The idea is that the paper should be folded so that the students cannot see their previous translations. At the bottom of the paper, some instructions to the students are written in Swedish. These instructions can be translated as follows:

Extract 8:

Homework until ThursdayPractice these words until Thursday.Write sentences or a story with at least ten of the words. (my translation)In the lesson from which Extract 9 was taken, Karin had a list of words in English that she wanted the students to translate into Swedish. In addition to Karin, Gabriela, Juan, Christian, Matthew, Messi, Edward, and some unidentified students participated in the discussion. Karin asked the students for a translation of the word ‘printer’ into Swedish. As the interaction progressed, she decided to also ask for the translation into Spanish. The transcript below is a truncated version of a slightly longer version.

Extract 9a:

Karin: Printer [says the name of a student]Juan: Vad sa du? <What did you say?>Karin: Printer? … [truncated]Karin: Vet du vad en printer är, på svenska? <Do you know what a printer is, in Swedish?>Juan: mmKarin: Print, du vet ju på datorn står det print. < Print, you knowon the computer it says print.>Juan: (xxx) Vad är det man ska? <What is it that one issupposed to [do]?>Matthew: Skrivare <Printer>Karin: Skrivare! <Printer!> [sounds cheerful] heter det, vadheter det på spanska då? <that is what it is called, what is it called in Spanish?>In Extract 9a, the teacher introduces the word ‘printer’ and asks the students how to say the word in Swedish. When Matthew comes up with the Swedish translation, the teacher asks for the word in Spanish. In doing so, she opens up the teaching space for Spanish, another of the young people’s linguistic resources.

Extract 9b:

Student: öh < eh>Christian: Escribítor [makes up a word that sounds likeSpanish and pronounces it with an accent]Student: nej <no>Karin: escri[], escritor <wri[], writer > [laughs]Student: (xxx)Juan?: Ja, escritorio <yes, desk> Karin: [laughs] escritorio <desk> Christian: Det var nära, escribítor <That was close, escribítor> [says made-up word again]In Extract 9b, Christian plays with languages and creatively makes up a Spanish-sounding word. Christian was born in Sweden and speaks Greek, Spanish, Swedish, and English. He mainly uses Greek and Swedish at home, whereas Spanish and English are his school languages. (Interview February 25th, 2011). Later in the extract, Juan provides the term for ‘desk’ in Spanish, which Karin correctly models. However, Christian appears to evaluate Karin’s ‘escritorio’ by insisting on his made-up word.

Extract 9c:

Gabriela: Vadå? <What?>Karin: Jaa <Yees>Karin: men escritorio är väl skri[], författare va? <but desk isn’t that writ[e], author, right?>Student: Ja <Yes> Gabriela: Vadå? Vad? <What? What?> Student: För att skriva <To write> Gabriela: Nej! Det heter inte så. <No! That’s not what it’s called.>Student: (xxx) Student: kan vi bara fortsätta? <can we just continue?>In Extract 9c, Gabriela gets involved by questioning the ongoing discussion. Some of the students appear annoyed and insist on moving on with the translations from English into Swedish. It is Gabriela who not only lets Karin know that she has been provided with an incorrect word but also eventually comes up with the correct Spanish translation for ‘printer’.

Extract 9d:

Karin: Skriva är escribir <Write is write>Student: MmKarin: Och skriv-a-re <and print-er [write-er]>Student: Den som skriver <The one who writes>Messi: Escritorio! Escritorio. <Desk! Desk.>Karin: Escritorio <Desk > mmGabriela: Nej <No>Karin: På datorn när man får ut papper <On the computer whenone gets out paper>Juan?: Jaha! Nej. <Oh! No.>Gabriela: Nej.<No.>Student: (xxx)Student: Esa maquina … <That machine … > (xxx)Gabriela: IMPRESORA! <PRINTER!>Karin: Vad hette det sa du? <What did you say it was called?>Gabriela: Impresora.<Printer>Karin: Impresora heter det ju för det står ju impri[], imprim[] <Of course, it’s called printer because it sayspri[],prin[]>Student: Imprimir <print>Karin: Imprimir står det ju, skriva ut. Det är skrivare. <Itsays print, to print. That is printer.>Student: Dom trodde det var skrivarpapper <They thought it waspaper to print on>Student: ShelfKarin: Shelf då, vet du vad det är? <What about shelf, do youknow what that is?>(English language lesson May 23rd, 2011).In Extract 9d, Karin attempts to guide the students to the Spanish translation by comparing the Swedish and Spanish words for ‘write’, since in Swedish the word for ‘printer’ (‘skrivare’) comes from the Swedish word ‘write’ (‘skriv’). This however, is not the case for the Spanish word for ‘printer’ and the comparison sets the students on the wrong track. One of the students provides the term ‘maquina’ before Gabriella – whose first language is Spanish (Interview) – finally shouts out the correct Spanish translation ‘impresora’. The teacher then concludes the discussion by linking the Spanish term for ‘printer’ (‘impresora’) with the Spanish verb ‘to print’ (‘imprimir’) before moving on to the next term.

In this context, the teacher becomes the learner, as she asks the students to translate to a language she herself has not mastered. Thus, she becomes dependent on the students’ linguistic knowledge and on their translations. The teacher places trust in Messi’s translation, most likely because Spanish is his mother tongue. However, Messi’s translation is wrong. It is possible that Messi, who has recently started learning Swedish, misinterprets the word in Swedish, which results in an erroneous translation.

Despite the difficulties in finding the correct translation for ‘printer’ in Spanish, the teacher yet again embarks on a similar journey by asking the students to translate the next word on their list – ‘shelf’ – to Spanish. Someone suggest ‘biblioteca’ (‘library’), which is immediately rejected and identified as an incorrect translation by the teacher and some students. A boy then suggests ‘madera’ to the friends sitting near him, and since this provokes laughter among his friends, he jokingly adds ‘voy a comprarme una madera’ (‘I’m going to buy myself a piece of wood).

Despite her linguistic limitations in Spanish, Karin attempts to include the students’ knowledge of Spanish as a linguistic resource in the classroom. On an ideological level, her attempts to use both Swedish and Spanish as pedagogical resources are important. Using Spanish during an English lesson serves as a way to wipe out (at least, temporarily) status differences between the languages that are used and to recognize and legitimize Spanish, which is the mother tongue of several students in the class. It may also serve the purpose of scaffolding. However, when the teacher lacks knowledge in Spanish, the possibilities to use the language for scaffolding purposes are limited and often result in parallel monolingualisms rather than spontaneous translanguaging ‘flows’ (see Lin Citation2019, 8).

The task of finding a Spanish translation for an English word stirs interest among the students and results in linguistic negotiations and the use of and development of metasemantic skills as the students reject translations before settling on the most appropriate one. There is a good deal of interest in the infinitive forms of verbs (‘write’, ‘print’, ‘imprimir’, ‘skriva’, ‘escribir’) and how these serve to shape other words. The teacher and her students attempt to do this across languages – not always successfully and not always willingly. However, they show an awareness of what is to be shared across their languages even when engaged in a pedagogic activity that does not relate in easy translations from one word to another.

Creese and Blackledge (Citation2010) write that teachers can use ‘flexible bilingualism’ (or translanguaging) ‘as an instructional strategy to make links for classroom participants between the social, cultural, community, and linguistic domains of their lives’ (p. 112). Otheguy, García, and Reid (Citation2015) suggest that translanguaging in education ‘invites speakers to deploy all their linguistic resources’ (p. 304) in a free manner. They argue that it is ‘unfair and inaccurate’ to use only monolingual approaches in the teaching and assessment of bilingual students. Instead, they suggest that a translanguaging approach offers ‘the potential to expand and free up all the learners’ linguistic and semiotic resources’. As a result, translanguaging in education and assessment ‘evens the playing field, giving bilingual students the same opportunity that monolinguals have always had’ (p. 305), i.e. being able to use all their linguistic resources. By levelling the playing field, translanguaging contributes to the contestation of linguistic hierarchies, monolingual norms, and power relations, and therefore has the potential to contribute to social justice in education.

Discussion

In the school observed here, languages are kept separate as parallel monolingualisms in planning and in the schedule (cf. double monolingualism norm, Jørgensen Citation2008). Also the language competences of the teachers at the school are at times ‘separated’ in the sense that teachers who use Spanish as their main medium of instruction are expected to understand and speak Swedish, whereas the teachers of Swedish and other subjects are not expected to understand or speak Spanish. This imbalance has consequences for language use in the classroom as well as in meetings among the teachers and with parents.

Despite this language separation, the analysis of English language lessons shows how languages are used in a more integrated manner in the everyday practices in the classroom, at times in line with the integrated bilingualism norm (Jørgensen Citation2008). Translanguaging is a practice employed both by the teacher and the students. These practices, however, are used seemingly without reflection and are not made explicit in the language classroom. Since translanguaging practices form part of bilinguals’ everyday language practices, there could be many pedagogical gains associated with making implicit the explicit by discussing how translanguaging practices can be used as resources in education. Such discussions could be encouraged both in class, among teachers and students, and at a school level, among teachers and members of the school board. As Hornberger and Link (Citation2012) write, translanguaging practices ‘offer possibilities for teachers and learners to access academic content through the linguistic resources and communicative repertoires they bring to the classroom while simultaneously acquiring new ones’ (p. 268). The teacher in this study is clearly trying to help students access the lesson content by translanguaging – in line with Hornberger and Link’s line of argument – but she also legitimizes English as the key language for the lessons and gives English a higher value (cf. Lin Citation1996).

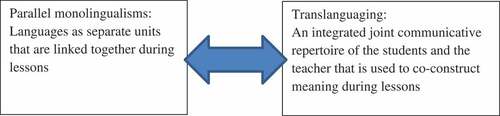

The results here show how there is a struggle between translanguaging in classroom discourse and parallel monolingualisms. On the one hand, translanguaging practices accentuate that the students and the teacher together share a joint communicative repertoire that can be seen integrated, as a whole and as a common resource. This is used to co-construct meaning through and beyond the linguistic and semiotic resources that constitute their communicative repertoires. On the other hand, emphasis is often on separating the students’ and the teacher’s communicative repertoires into different labelled languages during the lessons. This is particularly apparent in the teacher’s repeated use of labels such as ‘English’ and ‘Swedish’.

The joint communicative repertoire that the students and teacher share can be used as a resource to move across and beyond languages and to acquire and co-construct knowledge and competences in new languages. Together the students and the teacher negotiate linguistic and semiotic resources, making links between and across these, integrating and entangling them (cf. Hawkins and Mori Citation2018, 3). Interestingly however, instances of translanguaging – which accentuate the integratedness of language practices and communicative repertoires (according to the integrated bilingualism norm) – often include references to different languages, thus reinforcing a view of languages as separate units. This suggests that languages are ‘real’ for the participants, especially for the teacher who continuously talks about languages as separate units. On the basis of this, I suggest that we can view the two-fold process that takes place in the translanguaging space of the classroom as a continuum on which there is a tension or struggle between parallel monolingualisms and translanguaging

The study highlights several opportunities of translanguaging as pedagogy, but also some of the problems that may arise when teachers attempt to use languages they do not master as pedagogical resources in their teaching. On the whole, however, teachers’ attempts to incorporate languages that form part of the students’ linguistic repertoires in their teaching are ideologically important since such attempts signal that these are regarded as valuable assets at school and in society. By using the resources that students bring to class in order to make connections between the knowledge students already have and the knowledge they are working to obtain, a translanguaging pedagogy builds on, supports, and develops the ‘continuous (rather than binary, discrete), expanding, holistic repertoire of students’ (Lin Citation2019, 12).

Finally, the study also shows the power of teachers to decide when to translanguage and when to not do so. However, students can contest power relations and exercise agency by taking initiatives to be creative and by playing with words (as in the case of ‘madera’). The translanguaging space that is being created in the classroom can therefore be seen as negotiable, and as work in progress.

Transcription Conventions

| Plain Font: | = | Swedish and English |

| <Plain Font>: | = | English translation for Swedish (my translations) |

| Italics: | = | Spanish |

| <Italics>: | = | English translation for Spanish (my translations) |

| [ ]: | = | Contextual detail |

| (xxx): | = | Unintelligible speech |

| CAPITAL LETTERS: | = | emphasized words or parts of words |

Acknowledgements

A shorter version of this article was published in Naldic Quarterly (2012, vol 10, nr 1). The data for this study was collected as part of the transnational research project ‘Investigating Discourses of Inheritance and Identity in Four Multilingual European Settings’, funded by the European Science Foundation via HERA - Humanities in the European Research Area (2010-2012). The research team comprised of Adrian Blackledge, Jan Blommaert, Angela Creese, Liva Hyttel-Sørensen, Carla Jonsson, Jens Normann Jørgensen, Kasper Juffermans, Sjaak Kroon, Jarmo Lainio, Jinling Li, Marilyn Martin-Jones, Anu Muhonen, Lamies Nassri, and Jaspreet Kaur Takhi. I wish to express my gratitude to Emeritus Professor Marilyn Martin-Jones for sharing her expertize by reading and commenting upon a draft version of this article, and to the anonymous reviewers for valuable comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Carla Jonsson

Carla Jonsson is Associate Professor in bilingualism at the Centre for Research on Bilingualism at The Department of Swedish Language and Multilingualism at Stockholm University. Her research interests include multilingualism, literacies, translanguaging, identities, language ideologies, and language policies in education and work life.

Notes

1. ‘Intercultural Pedagogy and Intercultural Learning in Language Education’, funded by The Swedish Research Council (2007-//-2011).

2. For transcription conventions, see separate section below.

References

- Amir, A., and N. Musk. 2013. “Language Policing: Micro-Level Language Policy-In-Process in the Foreign Language Classroom.” Classroom Discourse 4: 151–167. doi:10.1080/19463014.2013.783500.

- Bakhtin, M. M. 1981. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays by M. M. Bakhtin, ed C. Emerson, M. Holquist, and M. Holquist. Austin & London: University of Texas Press.

- Blackledge, A. 2008. “Language Ecology and Language Ideology.” In Encyclopedia of Language and Education, Vol 9. Ecology of Language, edited by A. Creese, P. Martin, and N. Hornberger, 27–40. New York: Springer.

- Blackledge, A. and A. Creese. 2014. Heteroglossia as Practice and Pedagogy. In: A Blackledge and A Creese (eds). Heteroglossia as Practice and Pedagogy. New York: Springer, 1-20.

- Block, D. 2003. The Social Turn in Second Language Acquisition. Edinburgh: Edinburg University Press.

- Blommaert, J., and B. Rampton. 2011. “Language and Superdiversity.” Diversities 13 (2): 1–21.

- Busch, B. 2012. “The Linguistic Repertoire Revisited.” Applied Linguistics 33: 503–523. doi:10.1093/applin/ams056.

- Canagarajah, A. S. 2011. “Codemeshing in Academic Writing: Identifying Teachable Strategies of Translanguaging.” Modern Language Journal 95: 401–407. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01207.x.

- Creese, A., and A. Blackledge. 2010. “Translanguaging in the Bilingual Classroom: A Pedagogy for Learning and Teaching?” The Modern Language Journal 94: 103–115. doi:10.1111/modl.2010.94.issue-1.

- Creese, A., A. Blackledge, and H. Rachel. 2016. “Noticing and Commenting on Social Difference: A Translanguaging and Translation Perspective.” Working Papers in Translanguaging and Translation (WP. 10). (http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/generic/tlang/index.aspx)

- Creese, A., A. Blackledge, and H. Rachel. 2018. “Translanguaging and Translation: The Construction of Social Difference across City Spaces.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 21: 841–852. doi:10.1080/13670050.2017.1323445.

- Förordning. 2003. 459. Om försöksverksamhet med engelskspråkig undervisning i grundskolan. Svensk författningssamling. Stockholm: Sveriges Riksdag.

- Förordning. 2003. 306. Om försöksverksamhet med tvåspråkig undervisning i grundskolan. Svensk författningssamling. Stockholm: Sveriges Riksdag

- García, O 2009. Bilingual Education in the 21st Century: A Global Perspective. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

- García, O., and L. Wei. 2014. Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Grundskoleförordning. 1994. 1194. Svensk Författningssamling. Stockholm: Sveriges Riksdag.

- Hawkins, M. R., and J. Mori. 2018. “Considering ‘Trans-’ Perspectives in Language Theories and Practices.” Applied Linguistics 39: 1–8. doi:10.1093/applin/amx056.

- Heller, M. 1999. Linguistic Minorities and Modernity: A Sociolinguistic Ethnography. London: Longman.

- Hornberger, N., and H. Link. 2012. “Translanguaging and Transnational Literacies in Multilingual Classrooms: A Biliteracy Lens.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 15: 261–278. doi:10.1080/13670050.2012.658016.

- Hua, Z., L. Wei, and A. Lyons. 2017. “Polish Shop(Ping) as Translanguaging Space.” Social Semiotics 27: 411–433. doi:10.1080/10350330.2017.1334390.

- Jonsson, C. 2013. “Translanguaging and Multilingual Literacies: Diary-Based Case Studies of Adolescents in an International School.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 2013 (224): 85–117. doi:10.1515/ijsl-2013-0057.

- Jonsson, C. 2017. “Translanguaging and Ideology: Moving Away from a Monolingual Norm.” In New Perspectives on Translanguaging and Education, edited by B. Paulsrud, J. Rosén, B. Straszer, and Å. Wedin, 20–37. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Jørgensen, J. N. 2008. “Polylingual Languaging around and among Children and Adolescents.” International Journal of Multilingualism 5 (3): 161–176. doi:10.1080/14790710802387562.

- Language Act. 2009:600. Ministry of Culture. Government Offices of Sweden.

- Lin, A. M. Y. 1996. “Bilingualism or Linguistic Segregation? Symbolic Domination, Resistance and Codeswitching in Hong Kong Schools.” Linguistics and Education 8: 49–84. doi:10.1016/S0898-5898(96)90006-6.

- Lin, A. M. Y. 2019. “Theories of Trans/Languaging and Trans-Semiotizing: Implications for Content-Based Education Classrooms.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 22: 5–16. doi:10.1080/13670050.2018.1515175.

- Martin, P. 1999. “Bilingual Unpacking of Monolingual Texts in Two Primary Classrooms in Brunei Darussalam.” Language and Education 13: 38–58. doi:10.1080/09500789908666758.

- Møller Janus, S., and J. N. Jørgensen. 2009. “From Language to Languaging: Changing Relations between Humans and Linguistic Features.” Acta Linguistica Hafniensia 41 (1): 143–166. doi:10.1080/03740460903364185.

- Otheguy, R., O. García, and W. Reid. 2015. “Clarifying Translanguaging and Deconstructing Named Languages: A Perspective from Linguistics.” Applied Linguistics Review 6: 281–307. doi:10.1515/applirev-2015-0014.

- Rymes, B. 2010. “Classroom Discourse Analysis: A Focus on Communicative Repertoires.” In Sociolinguistics and Language Education, edited by N. H. Hornberger and S. L. McKay, 528–546. New York: Multilingual Matters.

- Rymes, B. 2014. “Communicative Repertoire.” In The Routledge Companion to English Studies, edited by C. Leung and B. V. Street, 248–259. New York: Routledge.

- Sebba, M. 2012. “Researching and Theorizing Multilingual Texts.” In Language Mixing and Code-Switching in Writing: Approaches to Mixed-Language Written Discourse, edited by M. Sebba, S. Mahootian, and C. Jonsson, 1–26. New York: Routledge.

- The Institute for Language and Folklore. Accessed 19 February 2019. https://www.sprakochfolkminnen.se/om-oss/for-dig-i-skolan/sprak-for-dig-i-skolan/spraken-i-sverige.html

- Varghese, M. 2004. “Professional Development for Bilingual Teachers in the United States: A Site for Articulating and Contesting Professional Roles.” In Bilingualism and Language Pedagogy, edited by J. Brutt-Griffler and M. M. Varghese, 130–145. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Wei, L. 2011. “Moment Analysis and Translanguaging Space: Discursive Construction of Identities by Multilingual Chinese Youth in Britain.” Journal of Pragmatics 43: 1222–1235. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2010.07.035.

- Wei, L. 2018. “Translanguaging as a Practical Theory of Language.” Applied Linguistics 39: 9–30. doi:10.1093/applin/amx039.