ABSTRACT

This study analyzed the effect of initial inoculum proportions on Listeria monocytogenes growth when cocultured with two different Weissella viridescens strains. W. viridescens C1 had a strong antimicrobial effect on L. monocytogenes which may be due to the acid, H2O2 and proteinaceous nature of its antimicrobial compounds. W. viridescens C2 had no antimicrobial properties. In liquid coculture, W. viridescens C1 inhibited L. monocytogenes growth, while W. viridescens C2 did not. Thus, L. monocytogenes showed the same growth in the W. viridescens C2 coculture as in the monoculture. Coculturing with W. viridescens at different initial inoculum proportions in laboratory media had no effect on L. monocytogenes growth. This study may help to characterize the interactions between L. monocytogenes and W. viridescens.

RESUMEN

El presente estudio analizó el efecto que ciertas proporciones iniciales del inóculo tienen en el crecimiento de Listeria monocytogenes en cocultivo con dos cepas distintas de Weissella viridescens. W. viridescens C1 mostró un fuerte efecto antimicrobiano en L. monocytogenes, debido posiblemente al ácido H2O2 y la naturaleza proteínica de sus compuestos antimicrobianos. Por el contrario, W. viridescens C2 no mostró propiedades antimicrobianas. En cocultivo líquido, W. viridescens C1 inhibió el crecimiento de L. monocytogenes, mientras que W. viridescens C2 no lo hizo. Esto permitió constatar que L. monocytogenes experimenta el mismo crecimiento en el cocultivo con W. viridescens C2 que en el monocultivo. En medios de laboratorio y en cocultivo con W. viridescens a distintas proporciones iniciales del inóculo, ésta no tuvo efecto alguno en el crecimiento de L. monocytogenes. El presente estudio puede ayudar a caracterizar las interacciones que pueden establecerse entre L. monocytogenes y W. viridescens.

Introduction

Predicting bacterial growth to summarize microbial kinetics is very important in microbial risk assessment (Dong et al., Citation2015). The typical experimental system for bacterial growth measures growth under actual food conditions. However, the true potential of application of food microbial predictive models is often unknown because most models do not consider microbial interactions in food. Therefore, predictive models for the pathogen of interest must consider the presence of organisms that can spoil food to more accurately describe the bacteria of interest (Brul, Gerwen, & Zwietering, Citation2007; Malakar, Barker, Zwietering, & Van’t Riet, Citation2003). Therefore, the microbial interaction between the background microorganism and the pathogen need to be first studied to confirm whether the background microorganism had the effect on the growth of the pathogen. Listeria monocytogenes threatens the food industry and is a concern to public health (Oxaran et al., Citation2017). Risk assessment is important for controlling L. monocytogenes in food, and bacterial growth predictions must accurately estimate L. monocytogenes concentrations in food at the time of consumption (McMeekin et al., Citation2008).

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are naturally found in food and dominate the microbiota of many foods, such as meat and meat products (Castellano, Holzapfel, & Vignolo, Citation2004; Chenoll, Macián & Elizaquível, Citation2007; Han et al., Citation2011; Jiang et al., Citation2010; Samelis, Kakour & Rementzis, Citation2000; Yost & Nattress, Citation2000). In recent years, LAB have received attention for their ability to inhibit foodborne pathogens through various antimicrobial compounds, such as lactic acid, hydrogen peroxide, and bacteriocins. Data in the literature have described some Weissella species, including Weissella viridescens, Weissella halotolerans, and Weissella hellenica, which are reported to be predominant microbiota in meat and meat products (Han et al., Citation2011; Hu, Zhou, Xu, Li, & Han, Citation2009; Santos et al., Citation2005). Some authors have studied predictive models of these predominant microbiota (Gimenez & Dalgaard, Citation2004; Le Marc, Valík & Medvedová, Citation2009; Liu, Guo, Li, Citation2006; Møller et al., Citation2013). Cornu, Billoir, Bergis, Beaufort, and Zuliani (Citation2011) studied the microbial competition models of L. monocytogenes behavior and LAB in pork meat products.

However, different strains and their different environments may affect the growth of the pathogenic bacteria of interest. Mellefont, McMeekin, and Ross (Citation2008) studied the effect of relative inoculum concentrations on the growth kinetics of L. monocytogenes in coculture, and found that the Jameson effect is often seen in food, particularly those in which LAB dominate. In another case, Coleman, Tamplin, Phillips, and Marmer (Citation2003) showed that the effects of agitation, initial density, pH, and strain were significant for growth kinetics near the boundaries of the growth/no growth interface for E. coli O157:H7. In predictive microbiology, typical experimental systems for growth studies measure the growth of the microorganism of interest under specific conditions, including initial inoculum, background microbiota, and bacterial strains. In this study, two W. viridescens strains with different bacteriocinogenic characteristics were isolated from meat and meat products, and coculture experiments of L. monocytogenes and W. viridescens in liquid media were designed to address two factors that may bias microbial predictive models for L. monocytogenes growth: strains and initial inoculum proportions.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains

Bacterial strains used in this study were either obtained from the culture collection center or isolated from meat products. The two W. viridescens strains labeled as C1 and C2, were originally isolated from meat products. In the subsequent section of this experiment, it was shown that the W. viridescens C1 strain was bacteriocinogenic, whereas the W. viridescens C2 strain was non-bacteriocinogenic. L. monocytogenes ATCC 19115 was a standard strain purchased from the China Center of Industrial Culture Collection (Beijing, China).

Inoculum preparation

All strains were stored at −80°C in a frozen storage medium with glycerol. Before inoculation, strains were activated and purified. The cultures of W. viridescens were incubated at 37°C for 15 h in MRS broth (de Man, Rogosa and Sharpe, OXOID, London, UK). The indicator strain L. monocytogenes was cultivated in TSB-YE Broth (Trypticase soy-yeast extract broth, Luqiao Co., Beijing, China) at 37°C for 15 h. The final concentrations were approximately 108~109 CFU/mL per strain, subsequently diluted to give the desired cell numbers before use.

Antilisterial activity of W. viridescens

The antilisterial activity of W. viridescens was analyzed by the agar disk diffusion assay (Ribeiro et al., Citation2014; Zeng et al., Citation2014). The L. monocytogenes ATCC 19115 suspensions used as the indicator strains were diluted to 0.1 OD, then plated by spreading them onto BHI agar (Brain-Heart Infusion agar, Luqiao Co., Beijing, China). The cell-free supernatants (CFS) of W. viridescens were obtained by centrifugation at 8000 g for 20 min, then filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane filter. In total, 200 μL of the CFS was added to four wells (6 mm diameter), then added to the plate containing L. monocytogenes. The plates were incubated at 4°C for 4 h for diffusion, then incubated at 37°C for at least 24 h to give a well-defined inhibition zone. Inhibition zone diameters were measured by Vernier calipers. The results represented the average of three trials.

Screening of bacteriocin-producing features

To validate W. viridescens inhibition, the inhibition effect under different conditions was performed as follows. (1) The CFS fluid was adjusted to pH 6.5 with 0.1 mol·L−1 NaOH to suppress the acid’s effect. (2) The above CFS fluid was then treated with 1 mg·mL−1 catalase (Solarbio, Beijing, China) and placed at 37°C for 4 h in a water-bath to suppress the effect of H2O2. (3) Then the CFS fluid was treated with 2 mg·mL−1 pepsin (Solarbio, Beijing, China) and 2 mg·mL−1 trypsin (Solarbio, Beijing, China) and placed in the water-bath. The CFS fluid pH was adjusted to the initial pH to suppress the bacteriocin effect. All the above treated CFS fluids were used for the antibacterial activity experiments. All measurements were conducted in duplicate.

Growth characteristics and acid-producing abilities

The growth characteristics and acid-producing ability of two W. viridescens strains were tested. W. viridescens strain C1 was shown to be bacteriocinogenic, while strain C2 was non-bacteriocinogenic. Each W. viridescens strain was incubated at 37°C for 24 h in MRS broth and detected once an hour to obtain the OD600 value by spectrophotometer. The culture pH was monitored every two hours. Non-inoculated W. viridescens in MRS broth was the control.

Mixed culture of W. viridescens with L. monocytogenes

The two W. viridescens strains and the L. monocytogenes strains at different concentrations were prepared for the coculture experiment. In total, 200 mL of Lysogeny Broth medium (Luqiao Co., Beijing, China) was divided into three groups to prepare for the monoculture and coculture experiments as follows: (1) inoculated with both L. monocytogenes strain (final concentration of approximately 103 CFU·mL−1) and the W. viridescens strain (concentration of approximately 106 CFU·mL−1), (2) inoculated with L. monocytogenes (final concentration of approximately 103 CFU·mL−1), and (3) inoculated with the W. viridescens strain (final concentration of approximately 106 CFU·mL−1). The flasks were incubated at 4°C, and monitored daily. Each experiment was conducted in triplicate.

Experimental designs based on different initial inoculum proportions

The experimental design assessed the effect of initial inoculum proportions of L. monocytogenes and W. viridescens on bacterial growth in the cocultures. Three combinations of initial inoculum proportions were assessed including a high concentration group (final concentration of approximately 105 CFU·mL−1) and a low concentration group (final concentration of approximately 103 CFU·mL−1). All coculture experiments had either L. monocytogenes at a high concentration, L. monocytogenes at a low concentration or had equal concentrations of L. monocytogenes and W. viridescens. The monoculture of each species was the control. All flasks with Lysogeny Broth medium (Luqiao Co., Beijing, China) were incubated at 4°C. Each trial was repeated three times.

Microbiological analysis and pH measurement

The cultures at different time intervals were serially diluted, then plated on PALCAM agar (Luqiao, Beijing, China) for L. monocytogenes counts and on MRS agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) for W. viridescens counts. The average CFU·mL−1 of two plates was recorded. Simultaneously, 4 mL aliquots were removed from the inoculated test samples daily to determine the pH value, using a pH meter (METTLER TOLEDO, Switzerland).

Statistical analyses

The data were analyzed in Microsoft Excel (Version 2013). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were applied to determine the differences at a 95% confidence level (α = 0.05) by SPSS 18.0.

Results

Characterization of antimicrobial activity of W. viridescens

Effects of pH and enzyme treatment on CFS antimicrobial activity of the two W. viridescens strains on L. monocytogenes are summarized in . The original W. viridescens C1 CFS at room temperature exhibited a strong antimicrobial activity on L. monocytogenes (the inhibition zone diameter was 17.97 ± 1.03 mm). The NaOH treatment (adjusted to pH 6.5) and treatment with catalase and pepsin reduced the CFS antimicrobial activity, where the inhibition decreased significantly in each treated CFS (P < 0.05). However, the CFS after all antimicrobial activity treatments remained within detectable levels.

Table 1. Effect of pH, catalase, pepsin and trypsin on the CFS of two W. viridescens isolates against L. monocytogenes (n = 3).

Tabla 1. efecto de pH, catalasa, pepsina y tripsina en el CFS de dos aislados de W. viridescens versus L. monocytogenes (n = 3).

Growth characteristics and acid-producing ability of two W. viridescens strains

Studies on bacterial growth and acid production can provide a basis for their inhibitory effects. Therefore, the growth and acid production of two W. viridescens strains were monitored at 37°C over a 24 h culture period. shows that both W. viridescens strains had strong growth abilities, and each bacteria grew quickly after a three hour lag period, then entered the stationary phase after 14 h. also shows pH changes in the culture medium of each strain during the 24 h growth. After 4 h in the culture, the pH rapidly decreased from 6 to below 4.5, indicating that both W. viridescens strains could produce acid after the lag, thus inhibiting the other microorganism in the coculture. Compared with the results of two W. viridescens strains, there were no obvious differences in the growth and acid production abilities in the monoculture.

Figure 1. Growth curves and acid production of two W. viridescens isolates at 37°C within 24 h. W. C1-OD600: the OD600 value in W. viridescens C1 culture; W. C2-OD600: the OD600 value in W. viridescens C2 culture; W. C1-pH: the pH value in W. viridescens C1 culture; W. C2-pH: the pH value in W. viridescens C2 culture.

Figura 1. Curvas de crecimiento y producción de ácido de dos aislados de W. viridescens a 37°C en un lapso menor a 24 h. W. C1-OD600: el valor OD600 en el cultivo de W. viridescens C1; W. C2-OD600: el valor OD600 en el cultivo de W. viridescens C2; W. C1-pH: el valor de pH en el cultivo de W. viridescens C1; W. C2-pH: el valor de pH en el cultivo de W. viridescens C2.

Characterization of antimicrobial activity of W. viridescens

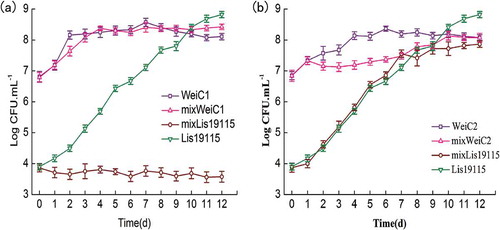

To further understand the inhibitory effect of the two W. viridescens strains on L. monocytogenes growth, coculture experiments were performed, and the results are shown in . In the monoculture, W. viridescens C1 inhibited L. monocytogenes growth, where L. monocytogenes was always in the initial numbers during the entire coculture period. However, L. monocytogenes in the coculture with W. viridescens C2 showed the same growth as that of the monoculture, and W. viridescens C2 was inhibited from Day 2 to Day 9.

Figure 2. Growth of L. monocytogenes and W. viridescens in monoculture or coculture during 4°C storage, respectively (n = 3). (a): Growth of L. monocytogenes and W. viridescens C1 in monoculture or coculture during 4°C storage; (b): Growth of L. monocytogenes and W. viridescens C2 in monoculture or coculture during 4°C storage. WeiC1: the number of W. viridescens C1 in monoculture; WeiC2: the number of W. viridescens C2 in monoculture; Lis19115: the number of L. monocytogenes in monoculture; mixWeiC1: the number of W. viridescens C1 when cocultured with L. monocytogenes; mixWeiC2: the number of W. viridescens C2 when cocultured with L. monocytogenes; mixLis19115: the number of L. monocytogenes when cocultured with W. viridescens.

Figura 2. Crecimiento de L. monocytogenes y W. viridescens en monocultivo o cocultivo, almacenados a 4°C, respectivamente (n = 3). (a): Crecimiento de L. monocytogenes y W. viridescens C1 en monocultivo o cocultivo, almacenados a 4°C; (b): Crecimiento de L. monocytogenes y W. viridescens C2 en monocultivo o cocultivo, almacenados a 4°C. WeiC1: el número de W. viridescens C1 en monocultivo; WeiC2: el número de W. viridescens C2 en monocultivo; Lis19115: el número de L. monocytogenes en monocultivo; mixWeiC1: el número de W. viridescens C1 en cocultivo con L. monocytogenes; mixWeiC2: el número de W. viridescens C2 en cocultivo con L. monocytogenes; mixLis19115: el número de L. monocytogenes en cocultivo con W. viridescens.

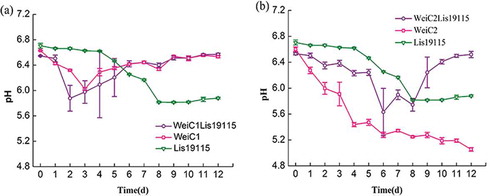

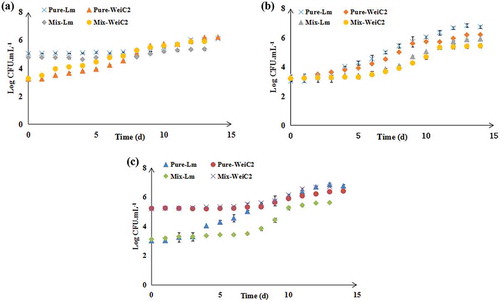

Effect of different relative inoculum proportions on L. monocytogenes growth when cocultured with two W. viridescens strains

Three groups, including the high concentration group (final concentration of approximately 105 CFU·mL−1 of L. monocytogenes and final concentration of approximately 103 CFU·mL−1 of W. viridescens), equal concentration group (final concentration of approximately 103 CFU·mL−1in both L. monocytogenes and W. viridescens) and low concentration group (final concentration of approximately 103 CFU·mL−1 of L. monocytogenes and final concentration of approximately 105 CFU·mL−1 of W. viridescens) were prepared to study the effect of different relative inoculum proportions on L. monocytogenes growth in cocultures with two W. viridescens strains. As shown in , W. viridescens C1 suppressed L. monocytogenes growth in each concentration group, particularly when W. viridescens C1 began growing. Regardless of the relative inoculum proportions of L. monocytogenes and W. viridescens C2 (), it was evident that W. viridescens C2 did not affect L. monocytogenes growth, as it had the same growth process as that in its monoculture. This indicated that the relative inoculum proportion did not inhibit L. monocytogenes when cocultured with W. viridescens.

Figure 3. Effect of different relative inoculum proportions on the growth of L. monocytogenes and W. viridescens C1 in monoculture and coculture during 4°C storage (n = 3). (a) L. monocytogenes at “high” concentration and W. viridescens C1 at “low” concentration group; (b) “Equal” concentrations of L. monocytogenes and W. viridescens C1; (c) L. monocytogenes at “low” concentration and W. viridescens C1 at “high” concentration group. Pure-Lm: the number of L. monocytogenes in the monoculture; Pure-WeiC1: the number of W. viridescens C1 in the monoculture; Mix-Lm: the number of L. monocytogenes when cocultured with W. viridescens C1; Mix-WeiC1: the number of W. viridescens C1 when cocultured with L. monocytogenes.

Figura 3. Efecto de distintas proporciones relativas del inóculo en el crecimiento de L. monocytogenes y W. viridescens C1 en monocultivo y cocultivo, almacenados a 4°C (n = 3). (a) L. monocytogenes en “alta” concentración y W. viridescens C1 en “baja” concentración; (b) Concentraciones “iguales” de L. monocytogenes y W. viridescens C1; (c) L. monocytogenes en “baja” concentración y W. viridescens C1 en “alta concentración”. Pure-Lm: el número de L. monocytogenes en el monocultivo; Pure-WeiC1: el número de W. viridescens C1 en el monocultivo; Mix-Lm: el número de L. monocytogenes en cocultivo con W. viridescens C1; Mix-WeiC1: el número de W. viridescens C1 en cocultivo con L. monocytogenes.

Figure 4. Effect of different relative inoculum proportions on the growth of L. monocytogenes and W. viridescens C2 in monoculture and coculture during 4°C storage (n = 3). (a) L. monocytogenes at “high” concentration and W. viridescens C2 at “low” concentration group; (b) “Equal” concentrations of L. monocytogenes and W. viridescens C2; (c) L. monocytogenes at “low” concentration and W. viridescens C2 at “high” concentration group. Pure-Lm: the number of L. monocytogenes in the monoculture; Pure-WeiC2: the number of W. viridescens C2 in the monoculture; Mix-Lm: the number of L. monocytogenes when cocultured with W. viridescens C2; Mix-WeiC2: the number of W. viridescens C2 when cocultured with L. monocytogenes.

Figura 4. Efecto de distintas proporciones relativas del inóculo en el crecimiento de L. monocytogenes y W. viridescens C2 en monocultivo y cocultivo, almacenados a 4°C (n = 3). (a) L. monocytogenes en “alta” concentración y W. viridescens C2 en baja concentración; (b) Concentraciones “iguales” de L. monocytogenes y W. viridescens C2; (c) L. monocytogenes en “baja” concentración y W. viridescens C2 en “alta” concentración. Pure-Lm: el número de L. monocytogenes en el monocultivo; Pure-WeiC2: el número de W. viridescens C2 en el monocultivo; Mix-Lm: el número de L. monocytogenes en cocultivo con W. viridescens C2; Mix-WeiC2: el número de W. viridescens C2 en cocucltivo con L. monocytogenes.

Discussion

In this study, two W. viridescens strains were evaluated for their effect on L. monocytogenes growth. In previous studies, several LAB metabolites, such as acid, hydrogen peroxide and bacteriocins, were considered as factors affecting antimicrobial activity (Hadji-Sfaxi et al., Citation2011). Inhibition zones of the different treated CFS in this study suggested that acid, H2O2 and the proteinaceous nature of antimicrobial compounds are involved in the antimicrobial activity of W. viridescens C1 on L. monocytogenes. For W. viridescens C2, no antimicrobial properties were detected in its CFS. Therefore, two W. viridescens with different characteristics, C1 and C2, were used for follow-up tests. Bacterial characteristics of the two W. viridescens strains indicated that acid was not a factor on W. viridescens C1 inhibiting L. monocytogenes. Several studies previously found that other factors, such as bacteriocin-like substances, quorum-sensing signaling molecules and competition for nutrients, may contribute to this inhibition (Cruz, Graham, Gagliano, Lorenz, & Garsin, Citation2013; Huang, Ye, Yu, Wang, & Zhou, Citation2016; Park et al., Citation2014). For example, Benkerroum et al. (Citation2002) and Han, Lee, Choi, and Paik (Citation2013) showed that LAB could produce various metabolic products, such as bacteriocin, during the stationary period. Stratakos et al. (Citation2016) found that the protective culture of W. viridescens in lower pH was able to gradually reduce the L. monocytogenes counts during storage. Therefore, it is important to understand their growth characteristics to analyze their metabolic production.

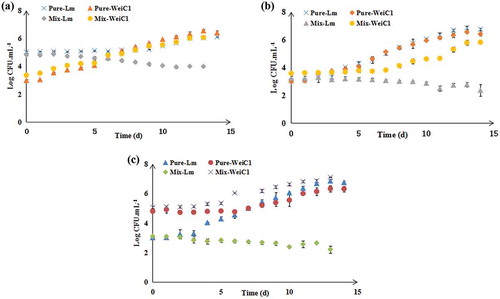

Coculture experiments had similar findings to the experiments on their antimicrobial activity. LAB dominate the spoilage bacterial population in meat and meat products, and W. viridescens is one of the species in this group (Comi & Iacumin, Citation2012; Hu et al., Citation2009; Samelis, Kakouriet & Rementzis, Citation2000). When meat and meat products were contaminated with L. monocytogenes, both species interacted and affected microbial growth predictions. This result was also seen in strains selected for bio-protective cultures. This study found that bacteriocinogenic W. viridescens C1 affected L. monocytogenes growth in coculture, while non-bacteriocinogenic W. viridescens C2 did not. Previous studies demonstrated that the bacteriocin-producing LAB strains isolated from foods significantly inhibited pathogen growth. In this study, different strains of W. viridescens had different effects on L. monocytogenes growth. shows that the pH did not change in either coculture. However, W. viridescens C2 had a strong acid-producing ability at low temperatures in the monoculture, but not in the coculture. This may be due to the interaction between L. monocytogenes and W. viridescens C2.

Figure 5. Change of pH in different culture conditions during storage at 4°C (n = 3). (a): Change of pH in the coculture of W. viridescens C1 and L. monocytogenes; (b): Change of pH in the coculture of W. viridescens C2 and L. monocytogenes. WeiC1: the pH value in W. viridescens C1 monoculture; WeiC2: the pH value in W. viridescens C2 monoculture; Lis19115: the pH value in L. monocytogenes monoculture; WeiC1Lis19115: the pH value in the coculture of W. viridescens C1 and L. monocytogenes; WeiC2Lis19115: the pH value in the coculture of W. viridescens C2 and L. monocytogenes.

Figura 5. Cambio de pH en distintas condiciones de cultivo, almacenado a 4°C (n = 3). (a): Cambio de pH en el cocultivo de W. viridescens C1 y L. monocytogenes; (b): Cambio de pH en el cocultivo de W. viridescens C2 y L. monocytogenes. WeiC1: el valor de pH en el monocultivo C1 de W. viridescens; WeiC2: el valor de pH en el monocultivo C2 de W. viridescens; Lis19115: el valor de pH en el monocultivo de L. monocytogenes; WeiC1Lis19115: el valor de pH en el cocultivo de W. viridescens C1 y L. monocytogenes; WeiC2Lis19115: el valor de pH en el cocultivo de W. viridescens C2 y L. monocytogenes.

W. viridescens strains with different characteristics had different inhibitory actions on L. monocytogenes growth. This differed from the results of Coleman et al. (Citation2003) and Mellefont et al. (Citation2008), where L. monocytogenes was suppressed by all other strains when its inoculum level was lower. Conversely, when L. monocytogenes was initially present at a higher concentration, other bacterial growth was suppressed. These inconsistent results may be due to the different inhibitory mechanisms of different bacteria. Therefore, this study evaluated their effect on L. monocytogenes growth, to obtain an accurate growth prediction for L. monocytogenes in coculture.

In conclusion, this study indicates that W. viridescens C1 exhibited strong antimicrobial activity against L. monocytogenes, while W. viridescens C2 had no antimicrobial properties. H2O2 and the proteinaceous nature of antimicrobial compounds play a part in the antimicrobial activity of W. viridescens C1 on L. monocytogenes. Effects of initial inoculum proportions for L. monocytogenes and W. viridescens were similar for the growth/no growth of L. monocytogenes when cocultured with W. viridescens C1/C2 in laboratory media. This study may provide microbial interaction information for interspecific predictive models. Furthermore, validating predictive microbiological models generated in food matrices should consider background microorganisms for microbial foodborne hazards.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant Project 31401558; the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities under Grant Number [KJQN201548]; and the China Agriculture Research System under Grant Number [CARS-36-11B].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Benkerroum, N., Ghouati, Y., Ghalfi, H., Elmejdoub, T., Roblain, D., Jacques, P., & Thonart, P. (2002). Biocontrol of Listeria monocytogenes in a model cultured milk (lben) by in situ bacteriocin production from Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis. International Journal of Dairy Technology, 55(3), 145–151. doi:10.1046/j.1471-0307.2002.00053.x

- Brul, S., Gerwen, S., & Zwietering, M. (Eds.). (2007). Modelling microorganisms in food. Boca Raton Boston, NY:CRC Press.

- Castellano, P. H., Holzapfel, W. H., & Vignolo, G. M. (2004). The control of Listeria innocua and Lactobacillus sakei in broth and meat slurry with the bacteriocinogenic strain Lactobacillus casei CRL705. Food Microbiology, 21, 291–298. doi:10.1016/j.fm.2003.08.007

- Chenoll, E., Macián, M. C., Elizaquível, P., & Aznar, R. (2007). Lactic acid bacteria associated with vacuum-packed cooked meat product spoilage: Population analysis by rDNA-based methods. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 102, 498–508. doi:10.1111/jam.2007.102.issue-2

- Coleman, M. E., Tamplin, M. L., Phillips, J. G., & Marmer, B. S. (2003). Influence of agitation, inoculum density, pH, and strain on the growth parameters of Escherichia coli O157: H7-relevance to risk assessment. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 83, 147–160. doi:10.1016/S0168-1605(02)00367-7

- Comi, G., & Iacumin, L. (2012). Identification and process origin of bacteria responsible for cavities and volatile off-flavour compounds in artisan cooked ham. International Journal of Food Science & Technology, 47, 114–121. doi:10.1111/ifs.2011.47.issue-1

- Cornu, M., Billoir, E., Bergis, H., Beaufort, A., & Zuliani, V. (2011). Modeling microbial competition in food: Application to the behavior of Listeria monocytogenes and lactic acid flora in pork meat products. Food Microbiology, 28, 639–647. doi:10.1016/j.fm.2010.08.007

- Cruz, M. R., Graham, C. E., Gagliano, B. C., Lorenz, M. C., & Garsin, D. A. (2013). Enterococcus faecalis inhibits hyphal morphogenesis and virulence of Candida albicans. Infection and Immunity, 81(1), 189–200. doi:10.1128/IAI.00914-12

- Dong, Q. L., Barker, G. C., Gorrisc, L. G. M., Tian, M. S., Song, X. Y., & Malakar, P. K. (2015). Status and future of Quantitative Microbiological Risk Assessment in China. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 42, 70–80. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2014.12.003

- Gimenez, B., & Dalgaard, P. (2004). Modelling and predicting the simultaneous growth of Listeria monocytogenes and spoilage microorganisms in cold-smoked salmon. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 96, 96–109. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.02137.x

- Hadji-Sfaxi, I., El-Ghaish, S., Ahmadova, A., Batdorj, B., Le Blay-Laliberté, G., Barbier, G., … Chobert, J.-M. (2011). Antimicrobial activity and safety of use of Enterococcus faecium PC4.1 isolated from Mongol yogurt. Food Control, 22(12), 2020–2027. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2011.05.023

- Han, E. J., Lee, N.-K., Choi, S. Y., & Paik, H.-D. (2013). Short communication: Bacteriocin KC24 produced by Lactococcus lactis KC24 from kimchi and its antilisterial effect in UHT milk. Journal of Dairy Science, 96(1), 101–104. doi:10.3168/jds.2012-5884

- Han, Y., Jiang, Y., Xu, X., Sun, X., Xu, B., & Zhou, G. (2011). Effect of high pressure treatment on microbial populations of sliced vacuum-packed cooked ham. Meat Science, 88(4), 682–688. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2011.02.029

- Hu, P., Zhou, G. H., Xu, X. L., Li, C. B., & Han, Y. Q. (2009). Characterization of the predominant spoilage bacteria in sliced vacuum-packed cooked ham based on 16S rDNA DGGE. Food Control, 20, 99–104. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2008.02.007

- Huang, Y., Ye, K. P., Yu, K. Q., Wang, K., & Zhou, G. H. (2016). The potential influence of two Enterococcus faecium on the growth of Listeria monocytogenes. Food Control, 67, 18–24. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.02.009

- Jiang, Y., Gao, F., Xu, X. L., Su, Y., Ye, K. P., & Zhou, G. H. (2010). Changes in the bacterial communities of vacuum-packaged pork during chilled storage analyzed by PCR–DGGE. Meat Science, 86, 889–895. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2010.05.021

- Le Marc, Y., Valík, L., & Medveďová, A. (2009). Modelling the effect of the starter culture on the growth of Staphylococcus aureus in milk. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 129, 306–311. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.12.015

- Liu, F., Guo, Y.-Z., & Li, Y.-F. (2006). Interactions of microorganisms during natural spoilage of pork at 5°C. Journal of Food Engineering, 72, 24–29. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2004.11.015

- Malakar, P. K., Barker, G. C., Zwietering, M. H., & Van’t Riet, K. (2003). Relevance of microbial interactions to predictive microbiology. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 84, 263–272. doi:10.1016/S0168-1605(02)00424-5

- McMeekin, T., Bowman, J., McQuestin, O., Mellefont, L., Ross, T., & Tamplin, M. (2008). The future of predictive microbiology: Strategic research, innovative applications and great expectations. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 128(1), 2–9. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.06.026

- Mellefont, L. A., McMeekin, T. A., & Ross, T. (2008). Effect of relative inoculum concentration on Listeria monocytogenes growth in co-culture. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 121, 157–168. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.10.010

- Møller, C. O. A., Ilgb, Y., Aabo, S., Christensen, B. B., Dalgaard, P., & Hansen, T. B. (2013). Effect of natural microbiota on growth of Salmonella spp. in fresh pork – A predictive microbiology approach. Food Microbiology, 34(2), 284–295. doi:10.1016/j.fm.2012.10.010

- Oxaran, V., Lee, S. H. I., Chaul, L. T., Corassin, C. H., Barancelli, G. V., Alves, V. F., … De Martinis, E. C. P. (2017). Listeria monocytogenes incidence changes and diversity in some Brazilian dairy industries and retail products. Food Microbiology, 68, 16–23. doi:10.1016/j.fm.2017.06.012

- Park, H., Yeo, S., Ji, Y., Lee, J., Yang, J., Park, S., … Holzapfel, W. (2014). Autoinducer-2 associated inhibition by Lactobacillus sakei NR28 reduces virulence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Food Control, 45, 62–69. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.04.024

- Ribeiro, S. C., Coelho, M. C., Todorov, S. D., Franco, B. D. G. M., Dapkevicius, M. L. E., & Silva, C. C. G. (2014). Technological properties of bacteriocin-producing lactic acid bacteria isolated from Pico cheese an artisanal cow’s milk cheese. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 116, 573–585. doi:10.1111/jam.2014.116.issue-3

- Samelis, J., Kakouri, A., & Rementzis, J. (2000). Selective effect of the product type and the packaging conditions on the species of lactic acid bacteria dominating the spoilage microbial association of cooked meats at 4°C. Food Microbiology, 17, 329–340. doi:10.1006/fmic.1999.0316

- Santos, E. M., Jaime, I., Rovira, J., Lyhs, U., Korkeala, H., & Björkroth, J. (2005). Characterization and identification of lactic acid bacteria in “morcilla de Burgos”. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 97, 285–296. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.04.021

- Stratakos, A. C., Linton, M., Tessema, G. T., Skjerdal, T., Patterson, M. F., & Koidis, A. (2016). Effect of high pressure processing in combination with Weissella viridescens as a protective culture against Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat salads of different pH. Food Control, 61, 6–12. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2015.09.020

- Yost, C. K., & Nattress, F. M. (2000). The use of multiplex PCR reactions to characterize populations of lactic acid bacteria associated with meat spoilage. Letters in Applied Microbiology, 31, 129–133. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.00776.x

- Zeng, X. F., Xia, W. S., Wang, J. S., Jiang, Q. X., Xu, Y. S., Qiu, Y., & Wang, H. Y. (2014). Technological properties of Lactobacillus plantarum strains isolated from Chinese traditional low salt fermented whole fish. Food Control, 40, 351–358. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.11.048