Abstract

Although a growing body of research in writing has suggested that females outperform males in many aspects of writing, our understanding of gender differences is still limited. The present study aimed to examine the potential sources of gender differences in writing fluency and text quality across Arabic as a first language (L1) and English as a foreign language (FL). 77 undergraduate Omani students produced two argumentative texts, one in Arabic and one in English. Their English proficiency was assessed using the Oxford Placement Test (OPT). Their writing was recorded and analysed via keystroke logging. The study found that females outperformed males in terms of writing fluency and text quality. Findings also indicated that females’ superiority in writing fluency and text quality is a consequence of their superiority in English proficiency. Furthermore, findings suggested that writing fluency in English is an important explanatory variable that accounted for females’ superiority in text quality. Findings are discussed in light of process-oriented writing research and implications for writing research and teaching are suggested.

Public Interest Statement

Recently more attention has been given to individuals differences in writing. Teaching writing effectively requires an understanding of the individual differences and their effects on writing performance. A broad potential of differences in gender has been identified in writing. These differences have been attributed to different aspects such as motivation and language proficiency. Gender differences have been associated with differences in writing performance; however, the processes by which these differences have their effects have been given relatively little discussion. It is important therefore to examine the factors which mediate the effects of such variable on the written product. For example, the relationships that have been observed between gender and text quality have not been linked directly to writing performance such as writing fluency. A key question here is how, and in what way, gender differences are mediated by cognitive, linguistic and motivational factors, and how these are, in turn, mediated by differences in writing performance?

1. Introduction

Reading and writing are the most important academic practices in helping students to understand and develop their knowledge about their disciplines (Lea & Street, Citation1998). University literacy practices depend to a large extent on formal written language (Thesen, Citation2001). Geiser and Studley (Citation2002) stressed the importance of writing skills at the tertiary level by stating that the ability to write an extended text is one of the best predictors of success in the course and of coping with university life. Similarly Krause (Citation2001) related academic success to writing since the assessment of many disciplinary courses is done through different forms of written texts (e.g., reports, essay exam, research papers, essays, and short answers). Writing is also crucial for disciplinary teachers to evaluate students’ progress, achievement, success and failure (Ellis & Yuan, Citation2004). Recently more attention has been given to individuals differences in writing. There is a range of higher-level differences that have been associated with individual differences in writing performance. Teaching writing effectively requires an understanding of the individual differences and their effects on writing performance (Kormos, Citation2012). Writers vary in terms of cognitive and linguistic abilities, age, gender, interest level in writing, self-efficacy, anxiety and other variables. For example, individuals with different cognitive abilities might approach their writing with varying degrees of efficiency A number of empirical studies revealed that transcription skills, such as spelling and handwriting, compete with other writing processes for cognitive resources (Hayes, Citation2012a, Citation2012b; Hayes & Chenoweth, Citation2006). For example, children might not focus on generating content and organizing their text due to limitation in their transcription abilities; however, as the transcription skills are sufficiently automated over the early school years “more resources should become available for the other processes, such as idea generation and translation” (Hayes, Citation2012b, p, 384). This suggests that processes that have not been adequately automatized are more likely to cause cognitive overload. Consequently, individuals’ efficiency and speed in performing writing processes vary depending on their cognitive abilities (Kormos, Citation2012).

In a similar way, a broad potential of differences in gender has been identified in writing (Beard & Burrell, Citation2010; Berninger & Fuller, Citation1992; Olinghouse, Citation2008; Troia et al., Citation2013). These differences have been attributed to different aspects such as motivation and language proficiency. Gender differences have been associated with differences in writing performance; however, the processes by which these differences have their effects have been given relatively little discussion. It is important therefore to examine the factors which mediate the effects of such variable on the written product. For example, the relationships that have been observed between gender and text quality have not been linked directly to writing performance such as writing fluency. A key question here is how, and in what way, gender differences are mediated by cognitive, linguistic and motivational factors, and how these are, in turn, mediated by differences in writing performance?

The current study aimed to explore whether writing fluency and text quality in Arabic as a first language (L1) and English as a foreign language (FL) writing of 77 Omani College students studying English Language Teaching program (ELT) vary depending on the gender, if yes, the study intended to explore if English language proficiency mediated the effect of gender on writing fluency and text quality. The study contributed to the limited literature that has overlooked the factors that account for gender difference with adult writers in English writing. This helps to understand how males and females approach their writing and if any gender might experience any kind of writing difficulties. This is highly valuable as it enables teachers to consider these difficulties and assist individuals to overcome them.

2. Gender differences in writing fluency and text quality

An important issue that has been hugely overlooked in English as a foreign language (FL) writing, in particular, and it deserves some kind of consideration in writing process research is a gender difference. Having said that, however, gender has been recognised as a large factor in education. The effect of gender on writing performance in First Language (L1) has been studied extensively in recent years. For example, previous research in L1 writing, particularly with children, has provided some evidence that females perform better than males in many aspects of writing, particularly in the UK and America (Adams & Simmons, Citation2019; Berninger & Fuller, Citation1992; Malecki & Jewell, Citation2003; Pajares & Valiante, Citation2001; Zhang et al., Citation2019). As within the cognitive writing perspective, studies have revealed recently that gender is an important predictor of writing performance of children as well as adults, typically favouring females (Adams et al., Citation2015; Beard & Burrell, Citation2010; Berninger & Fuller, Citation1992; Castro & Limpo, Citation2018; Olinghouse, Citation2008; Troia et al., Citation2013; Williams & Larkin, Citation2013). For example, Olinghouse (Citation2008) studied the predictors of third grade students’ narrative writing fluency and text quality. She found that girls were more fluent in writing, as measured by the total number of written words with a time limit, and produced better text in comparison to boys. Similarly, Berninger et al. (Citation1996) revealed that writing fluency and producing better text quality was associated more with girls. However, in contrast to Olinghouse’s (Citation2008) study that revealed that gender remained significant in predicting text quality, in favour of girls, even when compositional fluency was controlled for, Berninger et al. (Citation1996) did not reach a similar conclusion. Their studies provided enough evidence to suggest that when writing fluency was statistically controlled, gender difference became insignificant. The mastery of transcription, the process of converting language strings into written text, is associated with achievement in writing (Bourdin & Fayol, Citation1994, Citation2002; Castro & Limpo, Citation2018; Limpo & Alves, Citation2017). The significant relationship between text quality and the mastery of lower- level transcription skills, e.g., spelling, is consistent in the literature (Adams et al., Citation2015; McCutchen, Citation1996, Citation2000). Girls master these skills earlier and more effectively than boys (Adams et al., Citation2015; McCutchen, Citation1996). This might explain their superiority in writing fluency as well as text quality.

In the same vein, Verhoeven and Van Hell (Citation2008) reported that girls, whose age was 10 years, wrote the longer text and used a variety of lexical items as opposed to boys, in the similar age. Similarly, Beard and Burrell (Citation2010), who investigated writing attainment of year 5 children (9–10 years old) in narrative and persuasive tasks using a standardised test (including rating criteria such as spelling, vocabulary, grammar, purpose and organisation), also reported a significant advantage for girls. Babayiğit (Citation2015) studied English speaking L1 and FL children (about 9 years old) writing. She found that girls outperformed boys in text length, spelling, written vocabulary and text quality in both languages. Although Babayiğit (Citation2015) did not find a significant interaction between language and gender, her study suggests that there was a consistent trend indicating that gender differences were larger in FL, in favour of girls. Furthermore, Zhang et al. (Citation2019) compared the L1 (English) writing processes and text quality of 2,619 middle-school students (grades 6–9) using keystroke logging. Six essays produced by the participants were used to track and compare females’ and males’ writing processes and text quality. Their study reveals that females consistently obtained higher essay scores, composed more fluently, edited their texts more and paused less compared to males.

Different accounts have been offered to explain gender differences in writing. Beside the transcription skills, as explained above, aspects of individual motivation have been also identified in explaining gender disparities in writing. Among these is self-efficacy—individuals’ confidence in their own writing skills—which has been recognized as an important predictor of writing performance (M. Abdel Latif, Citation2009; Castro & Limpo, Citation2018). Research has shown the potential role of self-efficacy in explaining the disparities in gender in writing (Adams & Simmons, Citation2019; Castro & Limpo, Citation2018; Pajares et al., Citation1999; Pajares & Valiante, Citation2001; De Smedt et al., Citation2018; Troia et al., Citation2013). For example, Pajares and Valiante (Citation2001) and Pajares et al. (Citation1999) in their studies of school students, 8–10 years, found that girls hold stronger writing self-efficacy beliefs and scored higher in writing tasks compared to boys, whereas boys tended to be more apprehensive about their writing skills and writing tasks. They also revealed that self-efficacy is a significant predictor of writing performance and text quality. Motivation has been recognized as an important factor that explains differences of individual performance in writing (Castro & Limpo, Citation2018; Hayes, Citation2012b). The motivation aspect was not addressed in the original model of Hayes and Flower (the 1980 s) but was included in Hayes’ model (J. Hayes, Citation1996). Hayes (Citation2012b) argues that motivation is intimately involved in a number of aspects of the writing process, including individuals’ willingness to write, how long they can engage in writing and editing, and how much they are concerned about the quality of their writing.

Studies in gender difference in writing are consistently suggesting that gender difference is more apparent with younger age. However, studies with older students seemed to suggest that there is limited evidence for gender difference. For example, Jones and Myhill (Citation2007) studied adolescents (13–16 years old) and found very limited evidence to suggest that girls performed better than boys in L1 writing. Similarly, Spelman Miller et al. (Citation2008) in her longitudinal study of 17 Swedish high school students (14 years old), revealed no significant effect of gender in FL (English) writing process, i.e., writing fluency, text length, time on task, revision, pause time, pause length, as well as text quality. Furthermore, most of the gender difference research in writing has been exclusively limited to L1 writing with school students, mostly in America and the UK. Gender difference has been rarely studied in English as a foreign language (EFL) writing context with adult writers. The case might be different in EFL adult learners since their linguistic skills in English are less good. One potential difference between genders is language abilities as girls have been found to be linguistically better than boys (Huttenlocher et al., Citation1991; Hyde & Linn, Citation1988; Özçalişkan & Goldin-Meadow, Citation2010). However, research on writing typically has not explicitly dealt with this (language ability and gender differences) as a major issue. Little discussion has been given to how gender differences in cognitive writing might be mediated by linguistic factor. Furthermore, using computer-based tracking methods to observe gender differences in writing processes should be considered, given that most of the previous studies used paper-based tasks and methods. Employing computer-based tools to track writing processes, such as keystrokes, might probe the debate about gender difference further (Zhang et al., Citation2019). This might contribute to our understanding of what underlies gender differences in writing in general and, in turn, advance theory with respect to gender differences in writing processes.

2.1. The Context of the Study

There is, generally, an apparent paucity of this type of research within the Arabic English as a foreign language (EFL) context, particularly within the Gulf State of Oman. In this regard, there is a need to conduct more research in gender differences in writing in the EFL Omani context to determine whether this issue is unique to particular contexts, e.g., Europe and America, or common in other cultural contexts, e.g., Oman. Oman is a Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) state located in the southern part of the Arabian Peninsula with a population of around 4.5 million. Arabic is the official language in Oman. English is a foreign language in Oman and it coexists with Arabic language and other indigenous languages. English is the only means of communication between Omani people and expatriates/foreigners who work, live or visit Oman. It is the only foreign language that taught at government schools from grade one. It is also the primary medium of instruction at most higher education institutions. One might argue that English should be considered as a second language (L2) in Oman since it is widely used in Oman. Therefore, a distinction between the two should be made. Foreign language is where language is taught at schools as a subject and can be used as a means of instruction in most of higher education institutions, but it is not the language of the community that the individual belongs to. On the other hand, second language “is a language that the leaner masters the second best, after his first language” (Punchihetti, Citation2013, p. 5). Second language is widely used by the community where the individual belongs to. Accordingly, the individual is more familiar with and much better in using a second language than a foreign language. Although English is broadly used in a number of sectors such as education and business, the Omani society does not use English as a means of communication in its daily life. Thus, English is considered as a foreign language in Oman.

The current study took place in Rustaq College of Education which is public-funded by the government and affiliated to the Ministry of Higher Education in Oman. It is a state- sector college that offers free education to secondary school graduates based on students’ grades in secondary school and college capacity. It offers a number of educational programs such as English language teaching (ELT), maths and sciences. ELT students are required to achieve a certain level of English language proficiency before commencing their academic study (see 5.1 for more details about the participants). Although, writing and reading in English are given more weight in the students’ timetable, suggesting that these two skills are of great value to students’ academic accomplishment (see, Al-Badwawi, Citation2011), little research on writing has been carried out in Oman.

3. The Current Study

This study aimed to explore if gender differences exist in Arabic and English as a foreign language writing of adult learners and what accounts for this gender difference, e.g., English proficiency. This study focused only on the effect of gender on writing fluency and text quality. By investigating gender difference in writing with adult ELT Omani students, the current study aimed to improve our understanding of gender differences in writing and text quality, taking into account that studies in gender differences in writing, in general, are very limited (Zhang et al., Citation2019), particularly, in the Omani context. The study addressed the following questions:

To what extent, does writing fluency in Arabic and English writing vary depending on gender and is this mediated by FL proficiency?

To what extent, does the text quality of undergraduate Omani students in Arabic and English vary across gender?

What are the main sources of gender differences in text quality?

4. Methodology

4.1. Participants

Seventy-seven ELT undergraduate students (43 male and 34 female) studying at an English medium college in Oman whose age ranged between 20–23 years took part in this study. Arabic is the first language of all of these participants. Furthermore, they all had similar educational experience in learning English as a school subject before joining the College. All pupils in Oman start learning English from grade one at school until grade 12, and the English school curriculum is the same all over the country. The majority of the participants were enrolled in the foundation programme (FP) before starting their major. This is an intensive English language preparation programme that aims to improve students’ language skills and to equip them with the necessary academic skills in order to cope with their academic majors’ requirements. Maths and computer skills are also taught along with language courses. The duration of the FP differs from one student to another depending on their placement test score. The students are either required to study one semester (15 weeks), two semesters, three semesters, or four semesters. After passing the FP, ELT students receive instruction in English language subjects like phonetics, phonology, grammar, reading and vocabulary, essay writing, children’s literature, English literature, listening and speaking, teaching methods, reading in applied linguistics and sociolinguistics. Furthermore, they are regularly required to submit written research, reports, and written assignments in English to fulfil their academic courses’ requirement, and their exams are mostly based on academic essay writing.

Selecting these particular participants contributed to the homogeneity of the current research’s participants. This is because they have similar L1 (Arabic), had similar school curriculum and educational experiences underwent a similar FP and were exposed to the English language every day in studying their disciplines. The number of participants (77) is considered adequate in order to increase the statistical power of the analysis.

The study considered “purposive” sampling (Mackey & Gass, Citation2005) when selecting the participants. For example, the participants were drawn from two different academic years (second and fourth). The rationale of selecting two academic years was based on the assumption that these two groups would have different English language proficiency which is an important factor that is investigated in this study. Thus, it was expected that these two groups would probably perform differently in OPT. On the other hand, participation from each level was done on voluntary bases as participation was welcomed from all of the students within these two academic levels. Students were encouraged by their teachers to take part in the research.

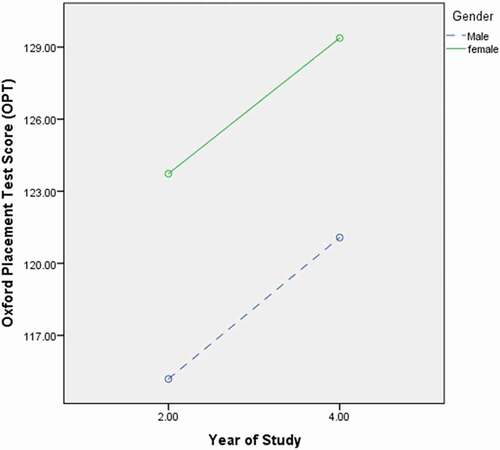

4.2. Instruments for Data Collection

4.2.1. Allen’s (Citation2004) Oxford Placement Test (OPT)

The writers’ FL proficiency was assessed using OPT. The OPT is composed of two parts: listening and grammar. The test consists of 100 multiple-choice items, 50 items in each part. On average, the completion of this test takes one hour, 10 minutes for the listening section and 50 minutes for the grammar part and its total score is 100. The grammatical structures included in the test were chosen from the structures regularly covered by most of the course books and public examinations such as those used by the British Council (M. Abdel Latif, Citation2009a). Allen (Citation2004) mentioned that OPT has been administered to students with different English language levels in 40 nationalities. Allen (Citation2004) maintained that the language used in OPT is controlled and counterbalanced so that the reliability of the test is high. Wistner et al. (Citation2008) compared the reliability of OPT and Michigan English Placement Test (MEPT). Their study which was based on studying 132 university students in Japan showed that the reliability of OPT (Cronbach’s alpha was.809) was higher than that of MEPT (Cronbach’s alpha was .753). The current study revealed a high reliability score for the OPT as Cronbach’s alpha was .806. Based on Allen’s (Citation2004) interpretation of the significance of the OPT scores, the participants of the current study were categorized as “lower—intermediate—modest users” based on their scores in OPT (Mean = 121.61, SD = 10.37). In order to assess how English proficiency varied depending year of study and gender, a two-way analysis of variance, was carried out, with participants’ year of study and gender as between factors, and English language performance (OPT) as the dependent variable. The effect size was evaluated using Cohen’s (Citation1988) criteria which suggest that partial eta square (η2p) values at or above .01, .06, and .14 indicate small, medium and large effect sizes respectively. The analysis indicated that there was a significant main effect of year of study (F(1,73) = 5.35, p = .024, η2p = .07), with students in year 4 (Mean = 123, SD = 11.18) performing better than students in year 2 in OPT (Mean = 120.5, SD = 9.6), and a significant main effect of gender (F(1,73) = 11.41, p = .001, η2p = .13), with females (Mean = 125, SD = 8.6) performing better than males (Mean = 118.9, SD = 10.9). Figure shows the mean scores on OPT as a function of year of study and gender. As can be seen in the figure, females scored higher overall on OPT than males in both years of study. In addition, performance was consistently better in year 4 than year 2, indicating that students’ language performance had improved between year 2 and 4.

In the light of the significant association between gender and English proficiency, subsequent analyses assessed whether any gender differences in performance of the FL writing task were mediated by FL proficiency.

4.2.2. Writing Tasks

The current study used argumentative tasks to encourage writers to engage in problem-solving activity and in incorporating their personal perspectives and experiences. In order to counterbalance the topic effect, the participants were given two general writing topics, which they were comfortable and familiar with (see Appendix A). The decision to present the writing prompt in L1 (Arabic), as well as FL (English), was important for clarity and comprehensibility (Kroll & Reid, Citation1994; Reid & Kroll, Citation1995). Furthermore, by giving the participants the writing prompt in Arabic it was hoped to reduce “the possible effect of varied task comprehension [by students] in the foreign language” (Al Ghamdi, Citation2010, p. 80). Additionally, on the basis that Akyel (Citation1994) suggests specifying the audience and the purpose of the writing is important, and because offering an authentic context and audience might encourage a variety of writing processes, the participants were asked to write an article for an authentic college magazine.

4.2.3. Texts Assessment

The Arabic and English essays were rated holistically, by English language teachers at the College whose first language is Arabic. The texts were evaluated using a 25-point scale based on five different aspects: i) task achievement, ii) organization, iii) grammar usage, iv) punctuation, spelling and mechanics, and v) vocabulary, with each aspect allocated 5 points. Before assessing the participants’ texts, benchmarking, with the presence of the researcher and the assessors, was conducted for a number of reasons. First, it helped to assure that all of the assessors understood the writing criteria and how marking should be carried out. Second, it gave the assessors the opportunity to discuss the marking process, the criteria used in rating the written texts, and the participants’ texts scores with each other. Third, benchmarking helped to increase the consistency of participants’ texts rating. Since the raters were not very familiar with rating Arabic text, a professor of the Arabic language was invited to the benchmarking session and evaluated some Arabic samples. Some discussions regarding rating the Arabic texts took place during the benchmarking with the presence of the professor. This procedure actually helped the raters a lot in assessing the participants’ Arabic text. The same raters rated Arabic and English essays. Each essay was rated by two teachers and the average score was taken. In order to test the degree of agreement between the two assessors’ scores, reliability tests were conducted. The interrater reliability was relatively high for the participants’ overall score and the five criteria scores in English and Arabic texts (Pearson correlation coefficient was .935 and .891 for English and Arabic overall texts scores respectively). Two outliers were found and thus excluded from text quality analysis. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) showed that a single factor could be extracted from the data. The data also showed that the average overall quality and the average of the five quality components in each language (English and Arabic) were strongly correlated indicating that the five quality components present one factor, which is the overall text quality score. Therefore, following the analysis PCA and the bivariate correlations, the overall text quality score was used to measure the effect English language proficiency and gender on the quality of the text produced.

4.2.4. Keystroke Logging Program

Using the computer as a data collection instrument has become an efficient and common practice in research. Thorson (Citation2000) argued that computers enable researchers to collect data from a large sample in a more efficient and reliable way. In addition, it is believed that individuals’ computer skills have increased and many writers are considered proficient computer users who usually write using a word processor (Thorson, Citation2000). In the field of writing, computers have opened new doors for researchers to investigate the writing process and it provides opportunities to observe the real-time writing process. This study used Inputlog 7.0.0.11 downloaded from www.inputlog.net. Keystroke logging enables researchers to address different aspects of the writing process (e.g., the frequency, length, and occurrence of pauses during writing) and to conduct studies on larger scales (Leijten & van Waes, Citation2013). Inputlog is a word processor program with normal text editing functions. The distinctive feature of this research tool is that it “provides an unobtrusive record of the moment-by-moment creation of the text” (Baaijen et al., Citation2012, p. 247). It is installed and activated before the writing session starts, so it does not interfere with the writing activity (M. Abdel Latif, Citation2008; Spelman Miller, Citation2000). The writers can control and use the computer keys as they normally do with any text editor. When the writing session finishes, the recorded logged data is saved as XML files (Van Waes et al., Citation2009). These files provide rich data about the time and the occurrence of different activities like revision, P-bursts, pauses, time, cursor movement, deletions, spacebar … etc. The replay function can be used to elicit writers’ reflections on their own writing after the writing session (Spelman Miller et al., Citation2008; Thorson, Citation2000). This function also allows the researcher to replay the keystroke-recorded writing sessions in which they can study the writing process in more depth. This logged data can be also archived and used by other researchers (Van Waes et al., Citation2009).

4.3. Design and Procedure

The study took place in the spring of 2016 at the computer labs at the College. The head of the English Language Department and some teachers at the department played a very important role in encouraging the students to take part in this research. The researcher also met the students and explained the purposes of the research and encouraged them to participate in the research. The researcher explained to the students that each writing session will take about 40 minutes. They were also told that participating in the research requires reasonable typing proficiency in Arabic and English. The researcher also explained that the setup of the study requires them to complete an English language Test (OPT) that takes one hour. This actually motivated a lot of students to participate, particularly fourth-year students. ELT students in Oman are required to get score 6 in IELTS in order to secure a job in the government sector. Therefore, the ELT students at Rustaq College are looking for chances to practice any English language test that could enable them to practice their English language knowledge. It was noticed that the students were interested to take the OPT and to know how well they performed in the test. The OPT test was administered first to the participants. In order to counterbalance the language and topic effect, the participants were placed into four different groups. Two groups were from the second year (42 students) and the other two were from the fourth year (35 students). For example, the first participant in the first group wrote topic one in Arabic and topic two in English, while the second participant wrote topic two in Arabic and topic one in English. This procedure was followed with the other groups. In order to counterbalance the language effect, two groups (one group from the second year and one from the fourth year) wrote the English task first and then the Arabic task while the other two groups wrote the Arabic task first and then the English one. The setup of the study required each participant to attend two writing sessions in order to write two writing texts, one in Arabic and one in English, on the computer. The sessions were, almost, one week apart from each other. The writers’ writing processes were recorded using Inputlog 7.0.0.11 downloaded from www.inputlog.net (Leijten & van Waes, Citation2013; Van Weijen et al., Citation2009). During each session, the participants were given 40 minutes to finish the writing task, as this is typically the case in writing English text at the College. After distributing the writing prompts, students were instructed to click on the recording button for the keystroke logging software and to start writing. When the participants finished the writing task, they were instructed to click the stop icon.

5. Data Analysis

Prior to analysis extreme outliers, defined as scores three standard deviations above or below the mean, were excluded. The data were screened using normal Quantile-Quantile plot, histogram and test of normality, to check whether the data were normally distributed. Fluency variable was log-transformed to approximate normality. Bivariate correlations were calculated to identify the relationships between the variables. Repeated measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), which combines analysis of variance with multiple linear regression, was carried out to assess the effects of the independent variables on the dependent variables. Language of writing (Arabic and English) was used as a within-subject variable and gender and English language proficiency (OPT) were used as between-subject measures. Each dependent variable was examined separately. Independent variables were examined in sets; main effects, two-way interactions and three way-interactions. Non-significant terms were gradually removed in order to simplify the model. The results of the final simplified model are presented. Complementary analyses using mediation analysis Hayes (Citation2013), were carried out in later stages.

5.1. Writing Fluency

Mean length of P-burst, measured by the number of characters produced between pauses of two seconds or more, was used as an indicator of the participants’ writing fluency (M. Abdel Latif, Citation2013; Chenoweth & Hayes, Citation2001; Révész et al., Citation2017). The decision to use a threshold of 2 seconds was based on a convention in writing process research as most previous research has used the threshold of two seconds or more to measure the length of P-bursts (e.g., Chenoweth & Hayes, Citation2001; Lindgren et al., Citation2008; Spelman Miller et al., Citation2008; Revesz et al., Citation2017), and hence makes it more consistent to compare the results.

Normal Quantile-Quantile plot, histogram and test of normality indicated that the distribution for writing fluency (in Arabic and English) was positively skewed. Therefore, this variable was log-transformed which resulted in a satisfactory approximation to the normal distribution. The values presented in Table are the raw, rather than transformed scores. As can be seen in Table the length of P-bursts in Arabic and English and were moderately to strongly correlated with each other, which may indicate common factors such as the general typing speed of individuals, general language skills or overall writing strategy. In Arabic, the length of P-bursts was not related to either gender or English language proficiency. By contrast, in English the length of P-bursts was significantly correlated with both gender and OPT, indicating that females were able to produce longer P-bursts in English than males and individuals with higher OPT score produced longer P-bursts in English.

Table 1. Means (M) and standard deviation (SD) for each of the continuous variables, along with the bivariate correlations between variables

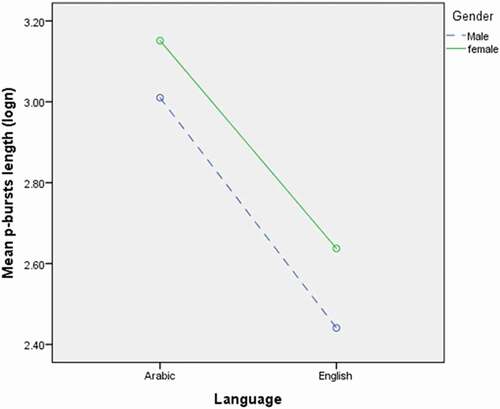

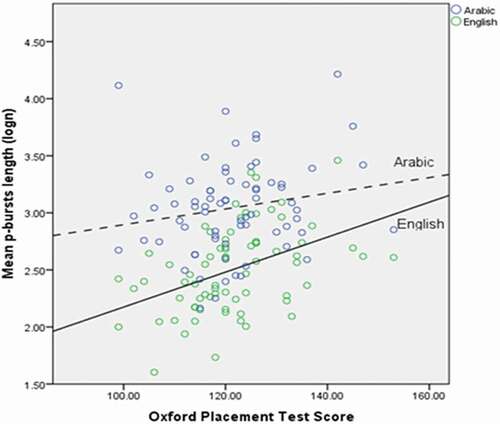

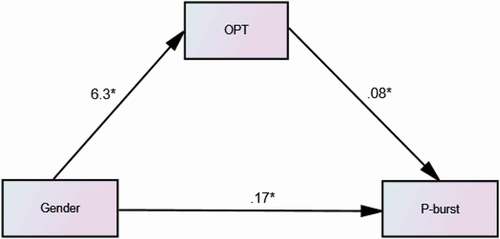

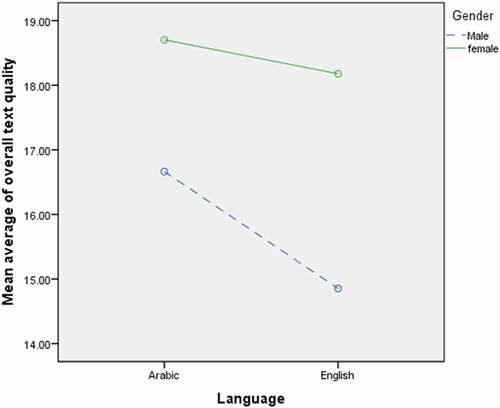

There was evidence that the effects of gender and English proficiency suppressed one another, so two separate regression models were fitted to the data. The first model, including gender but not English proficiency (OPT), showed significant main effects of language of writing (F(1,70) = 10.22, p = .002, η2p = .16), and of gender (F(1,70) = 4.59, p = .039, η2p = .062), but no significant interaction between them. As can be seen in Figure , this reflected the fact that participants produced longer P-bursts when writing in Arabic than in English, and that females produced longer P-bursts than males. The second model, including English proficiency but not gender, showed a significant interaction between language of writing and English proficiency (F(1,70) = 4.10, p = .041, η2p = .07). As can be seen in Figure , this reflected the fact that P-burst length was significantly correlated to English proficiency in English (b = .015, se = .004, p < .0005), but not significantly related to it in L1 (b = .007, se = .004, p = .13). Overall, this had the effect that, although P-burst length was larger in Arabic than English, the size of this difference was reduced for participants with higher English proficiency. The reason that the two alternative models fit the data is because of the significant correlation between gender and English proficiency, see Table . This has the effect that when both variables were included in the regression model at the same time they mutually suppressed one another. Therefore, mediation analysis was carried out to test whether the effect of gender on P-burst is a consequence of females’ superiority in English. Mediation analysis confirmed that the effect of gender on P-burst length in English was significantly mediated by English proficiency (p < .05). The path diagram showing these relationships is presented in Figure . There was no equivalent mediation in Arabic.

5.2. Text Quality

Table shows that the average overall text quality in each language correlated positively with gender. These results indicate that the average overall text quality in both languages was significantly higher for females. Regression analysis revealed a significant main effect of language (F(1,70) = 4.26, p = .043, η2p = .06), indicating that participants scored higher in the overall text quality in Arabic than English. English language proficiency also proved to have a significant main effect (F(1,70) = 15.24, p < .001, η2p = .18), implying that in general participants scored significantly higher in the overall text quality as their English language proficiency improved. Furthermore, gender had a significant main effect (F(1,70) = 20.69, p < .001, η2p = .23), indicating that females in general performed better than males in the overall text quality as demonstrated by Figure .

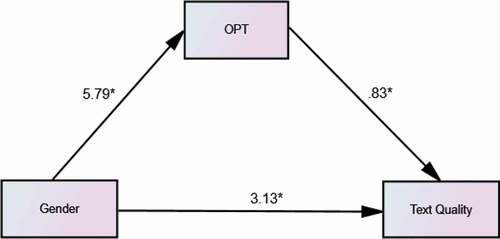

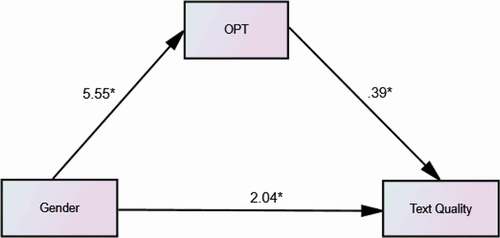

Mediation analysis suggests that gender had both direct and indirect effects on text quality in both languages. As for English task, the direct effect reflected that females produced better text quality than males (b = .3.13, se = .75, p < .0005). The indirect effect reflected the fact that females produced better text quality in English writing was indeed a consequence of their good command in English (b = .83, se = .35, p < .005), see Figure . Similarly, for the L1 task, there was a direct effect of gender (b = 2.04, se = .74, p < .005), indicating that females produced better text quality than males in Arabic. There was also a significant indirect effect through English language proficiency (b = .39, se = .24, p < .005), implying that higher English proficiency of females enabled them to produce better text quality in the Arabic task, see Figure . These results actually confirmed the results obtained from the bivariate correlations that females scored higher in text quality. The key feature of these relationships was that it applied across both languages. This might suggest that OPT captures general language proficiency, in addition to English language proficiency. It also might suggest that females are more motivated than males to produce better text quality.

Figure 6. The relationships between gender, English language proficiency and text quality in English writing (unstandardized coefficient).

Figure 7. The relationships between gender, English language proficiency and text quality in Arabic writing (unstandardized coefficient).

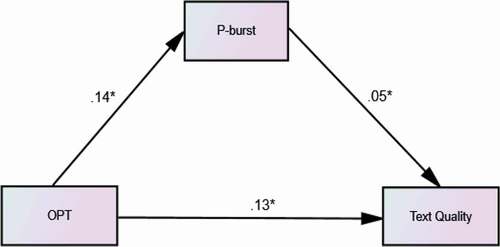

Furthermore, Table clearly shows a clear positive correlation between text quality score and writing fluency in English indicating that high-quality score is associated with writing fluency in English. This might indicate the possibility that females’ superiority in English text quality could partly be explained by their writing fluency advantage. In fact, mediation analysis revealed that the effect of English proficiency on females’ English text quality was significantly mediated by P-burst length in English (b = .05, se = .02, p < .005), as indicated by the path diagram in Figure . This relationship indicates that the females’ writing fluency partially accounted for the effect of English proficiency on text quality in English writing.

6. Discussion

The study was guided by three research questions that will be discussed with reference to the findings of the study and the literature review. The first research question examines if there were gender differences in writing fluency across Arabic and English and if this is mediated by English proficiency. Specifically, females proved to be more fluent than males in both languages and significantly in English. These findings actually replicate previous research’s findings that females are more fluent than males in writing (Babayiğit, Citation2015; Olinghouse, Citation2008b; Pajares & Valiante, Citation2001). However, the mediation analyses demonstrated that the greater linguistic maturity of females in English accounted for their writing fluency. Gender differences in English writing fluency appeared, in this sample at least, to be a consequence of differences in English proficiency rather than because of some other factors. However, the findings of the current study contrast with those of Spelman Miller et al.’s (Citation2008) research who found no effect of gender on writing fluency and text quality, in their study of relatively advanced English as a second language (L2) speakers. One explanation for the difference in findings may be that gender differences in text quality and writing fluency depends on language proficiency. It could be that gender difference is more pronounced at lower levels of language proficiency, and there is no longer gender difference once a certain threshold of language proficiency has been achieved. It is worth mentioning that the participants of the current study had lower-intermediate level of English. It is important to emphasize that these findings are correlational in form and hence that the influence of some other common factors cannot be ruled out. It is possible that the higher levels of motivation in females, for example, could account for their greater linguistic maturity as well as their greater fluency in writing in English. To rule this possibility out, future research would need to measure motivation to write, and control for it in analyses of the effects of other variables.

With regard to the second research question concerning the effects of gender on text quality, the data showed straightforwardly that text quality is related to gender with females producing better text than males (in both languages). This raises a question about where this gender difference came from. For English writing, this has a straightforward interpretation. Better proficiency in English enables one to write better text (M. Abdel Latif, Citation2009a; Al Ghamdi, Citation2010; Sasaki, Citation2004), and since the females in this sample had better English proficiency than males, they produced better text than males. As discussed previously that the effect of gender on writing is quite confusing because the literature has provided inconsistent findings. This study actually provided a clear-cut picture about gender gap and added a new empirical finding to the existing literature in writing in favour of females (Babayiğit, Citation2015; Castro & Limpo, Citation2018; Olinghouse, Citation2008). Furthermore, the fact that the effect of English proficiency on English text quality was mediated by females’ writing fluency indicates that the efficiency of translation process, the process of converting thoughts to language, as reflected by P-burst, in English accounted for the variation in English text quality in this sample. In theory, automaticity for basic writing processes, such as transcription and translation, allows individuals to devote more cognitive resources for high cognitive concerns which consequently results in producing better text quality (McCutchen, Citation1996, Citation2000; Zhang et al., Citation2019). Previous research also found that writing fluency is an important predictor of English as a foreign language text quality (e.g., M. Abdel Latif, Citation2013; Al Ghamdi, Citation2010; Spelman Miller et al., Citation2008).

However, the fact that females also wrote better than males in Arabic, and this was mediated by their language proficiency in English indicated that there is a more general relationship with factors correlated with English proficiency. There are a number of possible explanations for this. First, proficiency in English may reflect more general language proficiency. It is possible that it also reflects linguistic proficiency in Arabic, more weakly but nevertheless significantly so that English proficiency also showed a smaller but significant mediating effect of gender on Arabic text quality. To test this explanation, future research should include a measure of language proficiency in Arabic as well as a measure of language proficiency in English. This would enable one to test whether the two measures were correlated and whether the relationship between Arabic text quality and English proficiency was true because of its correlation with Arabic proficiency. Second, and in addition to, these correlations may reflect a difference in motivation. Females may be more highly motivated than males and hence performed better on both the writing task and OPT. Previous research on gender difference actually found that males are less motivated than females in writing (Pajares & Valiante, Citation2001). This could be controlled for in future research by including a further test of the level of motivation for each task. The advantage of the present study is using a standardized English test to assess participants’ English proficiency. Using such test allows one to specify variation in language proficiency precisely and hence assess the correlation between language proficiency and gender. It enables one to provide a more precise account of the effect of gender on writing product and performance.

7. Conclusions and Implications

Overall, then, the study revealed clear evidence that females generally had better English language proficiency, were more fluent writers and produced better text than males in Arabic and English, in this sample. However, the differences in text quality and writing fluency were more pronounced and could be accounted for by females’ better language proficiency in English. The data also indicates the possibility, however, that gender difference may also be a consequence of the more general difference in language ability and/or difference in motivation. As mentioned previously that gender differences in writing have been problematic because the literature has provided contradictory findings. This study has provided a piece of consistent evidence for a gender difference in the writing performance of the students in this Omani sample. Perhaps more importantly, it has identified some of the features associated with this difference and shown how their effects on text quality are mediated by language ability and writing fluency.

However, when considering this study, the issue of gender differences is quite complicated. This study is clearly showing that what were apparent gender differences could be largely explained by language proficiency. This is important for future research claiming to establish gender differences. Are these difference in writing still related to gender or do they just reflect language ability? In which case, the question becomes, not so much why the females in this sample were better writers, but rather why did they have stronger language proficiency? Other factors might also account for gender differences other than language proficiency. These included a range of possibilities including motivation, topic or researcher effect. For example, being a female researcher might affect male participants’ performance. Males might act differently in the presence of a male researcher. Equally, attitudes towards learning and writing might also account for gender differences (Pajares & Valiante, Citation2001; De Smedit et al., Citation2018; Troia et al., Citation2013). Furthermore, gender differences as revealed by the current study could only be related to the specific writing topics used in the study. More generally, there is the question of how gender roles vary across cultures and how this might affect both attitudes and skill development. The strongest implication of the present study is not so much that there is an intrinsic difference between the genders but rather to emphasize the need to explicitly assess effects of gender and to measure the factors associated with gender. Thus, it may be that the gender difference observed here is specific to this sample or to the Omani cultural context, but the fact that language proficiency has been explicitly measured, and that effects on writing performance have been explicitly identified, means that there is a clear target for future research and instruction. For example, the present study suggests that, for this sample, language proficiency in English was the primary source of gender differences, and therefore that the gender gap might be reduced by improving FL instruction for males. Therefore, in order to improve males’ English writing fluency and text quality to the level of their females’ counterparts, teacher needs to target males’ English proficiency. This may involve giving males extra language classes in English. In other contexts, while there might still be evidence of gender differences, it is possible that these are primarily because of motivation or attitudes towards education, with the implication that should be the target of instruction rather than language proficiency.

The study also found that writing fluency (as reflected by P-burst) is an important variable that also accounted for gender differences in English text quality and this has pedagogical implications. For example, English teachers need to enhance the writing fluency of their English male writers and make it more automatic by teaching them some effective writing strategies. For example, giving the students the opportunities to practice free writing helps some processes such as language encoding and lexical retrieval to be more automatic (Chenoweth & Hayes, Citation2001). The findings of the current study is highly important in FL writing classes as few teachers consider this gender gap in writing instruction. Teachers need to play more positive roles to put into account gender differences through their assessments and feedback. It has been suggested that teachers’ assessments tend to be biased by their perceptions towards the writer’s gender, e.g., they tend to criticized male writers and give them more corrections compared to females writers who usually given higher scores by their teachers (Castro & Limpo, Citation2018). Teacher’s critical feedback to male writers might affect males’ self-efficacy and this in turn might affect negatively their writing skills. Therefore, it is highly important that teacher provide their male writers with more positive and constructive feedback in order to strengthen males’ sense of capability in writing. Teachers also need to avoid creating an impression that writing is a feminine act in their language classes (Ong, Citation2015). This is highly important to motivate male students to engage more and perform better in the writing classes. In addition, a number of strategies can be implemented in writing classes to improve students writing, in general. For example, selecting writing topics that are interesting and appealing to all students might work very well in improving the students’ performance in writing. Another strategy that can be implemented to improve writing is reading. Reading provides models for good writing as students can learn the vocabulary and the features of different genres. Thus, teachers need to provide their students with different reading texts that serve as a good model for writing. They also need to encourage their students to read independently outside the classroom.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Zulaikha Al-Saadi

Dr Zulaikha Al-Saadi I am a lecturer and researcher of Applied Linguistics and TESOL within English Language and Literature Department at Rustaq College of Education in Sultanate of Oman. I am graduate of Sultan Qaboos University (Oman), I hold an MA in Linguistics and English Language Teaching from University of Leeds and a PhD from the University of Southampton. My main research interest is in the cognitive writing process in English as a foreign language (FL). This involves basic research into the cognitive processes involved in writing and the factors affecting these processes (e.g., linguistic and social) using keystroke logging program. Insights from this research are applied into the teaching of writing in FL contexts. I am currently a member of the British Educational Research Association (BERA) and the International Association of English as a Foreign Language (IATEFL). I have presented a number of scholarly papers at a number of international conferences and symposia.

References

- Abdel Latif, M. (2008). A state-of-the-art review of the real-time computer-aided study of the writing process. International Journal of English Studies, 8(1), 29–19.

- Abdel Latif, M. (2009). Egyptian EFL students teachers writing processes and products: The role of linguistic knowledge and writing affect. PhD Thesis. University of Essex.

- Abdel Latif, M. (2013). What do we mean by writing fluency and how can it be validly measured? Applied Linguistics, 34(1), 99–105. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/ams073

- Adams, A., Simmons, F., & Willis, C. (2015). Exploring relationships between working memory and writing: Individual differences associated with gender. Learning and Individual Differences, 40, 101–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2015.04.011

- Adams, A. M., & Simmons, F. R. (2019). Exploring individual and gender differences in early writing performance. Reading and Writing, 32(2), 235–263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-018-9859-0

- Akyel, A. (1994). First language use in EFL writing: Planning in Turkish vs. planning in English. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 4(2), 196. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-4192.1994.tb00062.x

- Al Ghamdi, F. M. (2010). Computer assisted tracking of university student writing in English as a foreign language. PhD Thesis. University of Southampton.

- Al-Badwawi, H. (2011). The perceptions and practices of first year students’ academic writing at the Colleges of Applied Sciences in Oman. Unpublished PhD Thesis. University of Leeds, School of Education.

- Allen, D. (2004). Oxford placement test 2 (New edition). Oxford University Press.

- Baaijen, V., Galbraith, D., & de Glopper, K. (2012). Keystroke analysis: Reflections on procedures and measures. Written Communication, 29(3), 246–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088312451108

- Babayiğit, S. (2015). The dimensions of written expression: Language group and gender differences. Learning and Instruction, 35, 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2014.08.006

- Beard, R., & Burrell, A. (2010). Writing attainment in 9- to 11-year-olds: Some differences between girls and boys in two genres. Language and Education, 24(6), 495–515. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2010.502968

- Berninger, V. W., & Fuller, F. (1992). Gender differences in orthographic, verbal, and compositional fluency: Implications for assessing writing disabilities in primary grade children. Journal of School Psychology, 30(4), 363–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4405(92)90004-O

- Berninger, V. W., Fuller, F., & Whitaker, D. (1996). A process model of writing development across the life span. Educational Psychology Review, 8(3), 193–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01464073

- Bourdin, B., & Fayol, M. (1994). Is written language production more difficult than oral language production? A working memory approach. International Journal of Psychology, 29(5), 591–620. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207599408248175

- Bourdin, B., & Fayol, M. (2002). Even in adults, written production is still more costly than oral production. International Journal of Psychology, 37(4), 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590244000070

- Castro, S. L., & Limpo, T. (2018). Examining potential sources of gender differences in writing: The role of handwriting fluency and self-efficacy beliefs. Written Communication, 35(4), 448–473. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088318788843

- Chenoweth, N., & Hayes, J. (2001). Fluency in writing: Generating text in L1 and L2. Written Communication, 18(1), 80–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088301018001004

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences (2nd ed ed.). Erlbaum.

- De Smedt, F., Merchie, E., Barendse, M., Rosseel, Y., De Naeghel, J., & Van Keer, H. (2018). Cognitive and motivational challenges in writing: Studying the relation wth writing performance across students’ gender and achievement level. Reading Research Quarterly, 53(2), 249–272. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.193

- Ellis, R., & Yuan, F. (2004). The effects of planning on fluency, complexity, and accuracy in second language narrative writing. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 26(1), 59–84. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263104261034

- Geiser, S., & Studley, R. (2002). UC and the SAT: Predictive validity and differential impact of the SAT I and SAT II at the University of California. Educational Assessment, 8(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326977EA0801_01

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). An introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

- Hayes, J. (1996). A new framework for understanding cognition and affect in writing. In M. Levy & S. Ransdell (Eds.), The science of writing: Theories, methods, individual differences and application (pp. 1–27). Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Hayes, J. R. (2012a). Evidence from language bursts, revision, and transcription for translation and its relation to other writing processes. In M. Fayol, D. Alamargot, & V. W. Berninger (Eds.), Translation of thought to written text while composing. Advancing theory, knowledge, research methods, tools, and applications (pp. 15–25). Psychology Press:Taylor & Francis Group: New York.

- Hayes, J. R. (2012b, July). Modeling and remodeling writing. Written Communication, 29(3), 369–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088312451260

- Hayes, J. R., & Chenoweth, N. A. (2006). Is working memory involved in the transcribing and editing of texts? Written Communication, 23(2), 135–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088306286283

- Huttenlocher, J., Haight, W., Bryk, A., Seltzer, M., & Lyons, T. (1991). Early vocabulary growth: Relation to language input and gender. Developmental Psychology, 27(2), 236–248. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.27.2.236

- Hyde, J., & Linn, M. C. (1988). Gender differences in verbal ability: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 104(1), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.104.1.53

- Jones, S., & Myhill, D. (2007). Discourses of difference? Examining gender differences in linguistic characteristics of writing. Canadian Journal of Education/Revue Canadienne De L’éducation, 30(2), 456. https://doi.org/10.2307/20466646

- Kormos, J. (2012). The role of individual differences in L2 writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 21(4), 390–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2012.09.003

- Krause, K.-L. (2001). The university essay writing experience: A pathway for academic integration during transition. Higher Education Research & Development, 20(2), 147–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360123586

- Kroll, B., & Reid, J. (1994). Guidelines for designing writing prompts: Clarifications, caveats, and cautions. Journal of Second Language Writing, 3(3), 231–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/1060-3743(94)90018-3

- Lea, M. R., & Street, B. V. (1998). Student writing in higher education: An academic literacies approach. In Studies in Higher Education, 23(2), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079812331380364

- Leijten, M., & van Waes, L. (2013). Keystroke logging in writing research: Using inputlog to analyze and visualize writing processes. Written Communication, 30(3), 358–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088313491692

- Limpo, T., & Alves, R. A. (2017). Written language bursts mediate the relationship between transcription skills and writing performance. Written Communication, 34(3), 306–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088317714234

- Lindgren, E., Miller, S., & Sullivan, K. (2008). Development of fluency and revision in L1 and L2 writing in Swedish high school years eight and nine. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 156(1), 133–151. https://doi.org/10.2143/ITL.156.0.2034428

- Mackey, A., & Gass, S. (2005). Second language research: Methodology and design. lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Malecki, C. K., & Jewell, J. (2003). Developmental, gender, and practical considerations in scoring curriculum-based measurement writing probes. Psychology in the Schools, 40(4), 379–390. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.10096

- McCutchen, D. (1996). A capacity theory of writing: Working memory in composition. Educational Psychology Review, 8(3), 299–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01464076

- McCutchen, D. (2000). Knowledge, processing, and working memory: Implications for a theory of writing. Educational Psychologist, 35(1), 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3501_3

- Olinghouse, N. G. (2008). Student- and instruction-level predictors of narrative writing in third-grade students. Reading and Writing, 21(1–2), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-007-9062-1

- Ong, J. (2015). Do individual differences matter to learners’ writing ability? The Asian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 2(2), 129–139. http://caes.hku.hk/ajal

- Özçalişkan, Ş., & Goldin-Meadow, S. (2010). Sex differences in language first appear in gesture. Developmental Science, 13(5), 752–760. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00933.x

- Pajares, F., Miller, M. D., & Johnson, M. J. (1999). Gender differences in writing self-beliefs of elementary school students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(1), 50–61. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.91.1.50

- Pajares, F., & Valiante, G. (2001). Gender differences in writing motivation and achievement of middle school students: A function of gender orientation? Contemporary Educational Psychology, 26(3), 366–381. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.2000.1069

- Punchihetti, S. (2013). First, second and foreign language learning: How distinctive are they from one another? The European Conference on Language Learning, 1–16.

- Reid, J., & Kroll, B. (1995). Designing and assessing effective classroom writing assignments for NES and ESL students. Journal of Second Language Writing, 4(1), 17–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/1060-3743(95)90021-7

- Révész, A., Kourtali, N.-E., & Mazgutova, D. (2017). Effects of task complexity on L2 writing behaviors and linguistic complexity. Language Learning, 67(1), 208–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12205

- Sasaki, M. (2004). A Multiple-data analysis of the 3.5-year development of EFL student writers. Language Learning, 54(3), 525–582. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0023-8333.2004.00264.x

- Spelman Miller, K. (2000). Academic writers on-line: Investigating pausing in the production of text. Language Teaching Research, 4(2), 123–148. https://doi.org/10.1191/136216800675510135

- Spelman Miller, K., Lingren, E., & Sullivan, K. (2008). The psycholinguistic dimension in second language writing: Opportunities for research and pedagogy using computer keystroke logging. TESOLQuarterly, 42(3), 433–454. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1545-7249.2008.tb00140.x

- Thesen, L. (2001). Modes, literacies and power: A university case study. Language and Education, 15(2–3), 132–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500780108666806

- Thorson, H. (2000). Using the computer to compare foreign and native language writing processes: A statistical and case study approach. Modern Language Journal, 84(2), 155–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/0026-7902.00059

- Troia, G. A., Harbaugh, A. G., Shankland, R. K., Wolbers, K. A., & Lawrence, A. M. (2013). Relationships between writing motivation, writing activity, and writing performance: Effects of grade, sex, and ability. Reading and Writing, 26(1), 17–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-012-9379-2

- van Waes, L., Leijten, M., & van Weijen, D. (2009). Keystroke logging in writing research: Observing writing process with inputlog. German as a Foreign Language, 2(3), 41–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2009.06.003

- van Weijen, D., van den Bergh, H., Rijlaarsdam, G., & Sanders, T. (2009). L1 use during L2 writing: An empirical study of a complex phenomenon. Journal of Second Language Writing, 18(4), 235–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2009.06.003

- Verhoeven, L., & Van Hell, J. G. (2008). From knowledge representation to writing text: A developmental perspective. Discourse Processes, 45(4–5), 387–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/01638530802145734

- Williams, G., & Larkin, R. (2013). Narrative writing, reading and cognitive processes in middle childhood: What are the links? Learning and Individual Differences, 28, 142–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2012.08.003

- Wistner, B., Hideki, S., & Mariko, A. (2008). An analysis of the oxford placement test and the michigan English placement test as L2 proficiency tests. Journal of Takasaki City, 125(50), 33–44.

- Zhang, M., Bennett, R. E., Deane, P., & Rijn, P. W. (2019). Are there gender differences in how students write their essays? An analysis of writing processes. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 38(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/emip.12249

Appendix A

Writing Topics

Topic one: Write an article to Rustaq Round-up Newsletter about your opinion on this topic. Do you agree or disagree with the following statement? Administrative staff at Rustaq College are always helpful and offer efficient customer services. Support your opinion with example and details.

اكتب مقال موجهة الى (Rustaq Round-up Newsletter) حول رأيك في هذا الموضوع. هل توافق أو لا توافق على العباره التالية: الطاقم الإداري في كلية الرستاق دائما متعاون ويقدم خدمات فعالة. ادعم رأيك بالأمثلة التوضيحية والتفاصيل.

Topic two: Write an article to Rustaq Round-up Newsletter about your opinion on this topic. Do you agree or disagree with the following statement? Co-education is the cause of low academic achievement for many students. Support your opinion with examples and details.

اكتب مقال موجهة الى (Rustaq Round-up Newsletter) حول رأيك في هذا الموضوع. هل توافق أو لا توافق على العباره التالية: التعليم المختلط هو سبب تدني المستوى التحصيلي لدى الكثير من الطلاب. ادعم رأيك بالامثلة التوضيحية والتفاصيل