Abstract

Cooperation and competition often coexist in policy networks, and network actors may simultaneously trust and distrust one another. By considering these two pairs of coexistence, this study explores the patterns and drivers behind two paradoxes: the trustful competitor and the distrustful cooperator. Based on a survey and interviews with nuclear-related public institutions in South Korea, the study highlights two major points. First, the differing ways in which nuclear policy network actors assess situations (i.e. the assessment gap) may lead to trust in competition and also to distrust in cooperation. Second, it is not the mere presence of an assessment gap or bias between network actors that matters in coopetition within the policy network, but rather when, where, and how much such a gap exists, as it can be either beneficial or harmful to coopetition. The study concludes by suggesting vigilant and realistic assessments on self- and environment as the conditions for trustworthy coopetition.

1. Introduction

A policy network is the primary mechanism used to coordinate efforts towards achieving common policy objectives and addressing complex decision-making challenges related to sustainability (Loorbach, Citation2010). Thus, individual organizations may come and go, but networks of these organizations for policy making and implementation can endure, as long as the policy domain is sustained through interorganizational interactions. When it comes to dynamics among policy network actors, there are two pairs of ambivalent relationships: competition and cooperation (known as coopetition), and trust and distrust. Therefore, the sustaining policy networks can be likened to a platform where various organizations continually cooperate and compete with one another (O’Reilly, Citation2011), navigating both trustful and distrustful relationships (Lee, Citation2021). And the interplays of trust and distrust may vary in coopetitive relationships (Kostis & Näsholm, Citation2020; Lascaux, Citation2020; Raza-Ullah & Kostis, Citation2020). Considering the complex relationships within policy networks, this study explores: (1) how two ambivalently paired values—competition versus cooperation, and trust versus distrust—may be paradoxically combined to form trustful competition and distrustful cooperation; and (2) how such paradoxical dualities are influenced by the network actors’ perceptions of the situation.

In specific, competition and cooperation often co-exist in interorganizational networks (Czakon et al., Citation2020), as well as in policy networks (Lee et al., Citation2012). Many scholars have pointed out that such “coopetition” might be a universal relationship in which various organizations cooperate and also compete with one another to benefit their own and mutual interests. In short, organizations cooperate for market (or value) creation, and at the same time, also compete for market (or value) allocation and utilization (Brandenburger & Nalebuff, Citation1996; Dagnino, Citation2009; Kim, Citation2018; Lavie, Citation2008; Ritala et al., Citation2009). The co-existence of cooperation and competition in policy networks is often observed in public-private contracts (Fotaki, Citation2011; Lenferink et al., Citation2013; Marques & Berg, Citation2011; Rubery et al., Citation2013) and also among public service providers (Ménard, Citation2004; Osipovič et al., Citation2016). Besides the universality of coopetition in policy networks, another set of values that co-exist is trust and distrust. Trust and distrust may also coexist in any pair-relations in policy networks because each of two concepts, trust and distrust, points to a different dimension in the dyadic relationship (Lee & Lee, Citation2018).

As the coexistence of cooperation and competition, and also of trust and distrust is inevitable in policy networks, how then can we make such ambivalent relationships more reliable and trustful? Competitors might be more likely to be distrusted than other stakeholders, and cooperators should be more trusted than others. However, beyond this common sense idea, competitors need to be trusted for fair and constructive competition, while cooperators should remain cautious to prevent naivety and the risks of opportunism. Therefore, this study focuses more on another set of relationships: trustful competition and distrustful cooperation. While acknowledging the need for multidimensional approaches that consider the unique combinations of the ambivalent pairs (i.e., trust in competition and distrust in cooperation) together, this study explores: (1) how the two paradoxical relationships occur within policy networks; and (2) what factors may help explaining these relationships. Among the many potential explanatory variables, we investigate whether disparities between network members’ perspectives (on policy stance, attribution of policy issues, power structure, and contribution to policy issues) influence their trust in competitors and distrust in cooperators, and whether there are any similarities or differences between these explanatory variables.

To answer these questions, we used the data collected through surveys with the nuclear-related organizations in South Korea. The recent situation in the field of nuclear science and engineering in South Korea can be described as coopetition among nuclear-related ministries and institutions in three domains that include denuclearization, nuclear waste disposal, and nuclear industry development. Thus, it is presumed that the organizations in the nuclear policy network in South Korea may have experienced the paradoxical relationships in coopetition, and thereby, could provide some clues regarding the explanatory variables of such relationships. The following section will present the theoretical background behind the research questions and models.

2. Theory and research questions

2.1. Trust and distrust

This study explores the explanatory variables of the two response variables: trustful competition, and distrustful cooperation. Many studies on policy networks have been conducted with regard to the trust-based collaboration that exists among network actors (Ansell & Gash, Citation2007; Calò et al., Citation2018; Emerson et al., Citation2012; Hatmaker & Rethemeyer, Citation2008; Lundin, Citation2007; Rethemeyer & Hatmaker, Citation2008; Willem & Lucidarme, Citation2014).

In detail, trust refers to an actor’s willingness to become vulnerable based on positive expectations of the other’s conduct (Lewicki et al., Citation1998). Regarding the various functions of trust in the networks, trust may reduce transaction costs based on the confidence of information reliability (Berardo & Scholz, Citation2010; Leifeld & Schneider, Citation2012). Further, trust helps reduce uncertainty of decisions, facilitate information flows, and lead to a virtuous cycle of collaboration (Calanni et al., Citation2014; Ingold et al., Citation2017; Leach & Sabatier, Citation2005; Ostrom, Citation1998). Therefore, trust may determine how network actors form the network structures for effective decision-making and management (Park & Rethemeyer, Citation2014).

On the other hand, in many cases, distrust may be regarded as just an absence of trust, so they are mutually exclusive (Barber, Citation1983; Deutsch, Citation1958; Rotter, Citation1971, Citation1980; Stack, Citation1988; Tardy, Citation1988; Worchel, Citation1979). However, the difference between trust and distrust has recently received more attention (Lewicki, Citation2006; Lewicki et al., Citation1998; McEvily et al., Citation2012; Rousseau et al., Citation1998; Sitkin & Roth, Citation1993). To some scholars, the absence of trust does not necessarily mean the presence of distrust, and vice-versa (Ullmann-Margalit, Citation2004). Similarly, “low distrust is not the same as high trust, and high distrust is not the same as low trust” (Lewicki et al., Citation1998, p. 444). Specifically, trust is the “belief in a person’s competence to perform a specific task under a specific circumstances”, whereas distrust is the “belief that a person’s values or motives will lead them to approach all in an unacceptable manner” (Sitkin & Roth, Citation1993, p. 373). In summary, trust is more about hope, vulnerability, assuring and initiating, while distrust concerns fear, and being skeptical and vigilant (Lewicki, Citation2006).

Considering the different meanings of trust and distrust that exist in different dimensions or continua, distrust and trust are separate constructs, and therefore, they may be not mutually exclusive (Cho, Citation2006; Lewicki, Citation2006; Lewicki et al., Citation1998; Lumineau, Citation2017; McEvily et al., Citation2012; Sitkin & Roth, Citation1993; Ullmann-Margalit, Citation2004; Wales et al., Citation2013). In other words, distrust and trust can coexist and further co-move in the same directions, toward the same focal objects (Otnes et al., Citation1997; Priester & Petty, Citation1996; Thompson et al., Citation1995). Still, trust and distrust serve different roles at various stages of a relationship, each through distinct paths and mechanisms (Czakon et al., Citation2022; Nielsen, Citation2004).

2.2. Trustful competitor, distrustful cooperator

Then, why does trust and distrust matter in coopetition? Playing various positive roles at different levels and phases of coopetition (Chai et al., Citation2020; Czernek & Czakon, Citation2016), trust is not only an outcome but also an antecedent and driver of coopetition (Kostis & Näsholm, Citation2020). In specific, trust matters in competition because trust in a competitor may signify that the competition is fair, transparent and therefore, is sustainably beneficial to all competing actors. Thus, trust helps to mitigate uncertainty and risks in decision and information exchange (Muthusamy & White, Citation2005; Putnam, Citation2001), and promotes collaboration in networks (Ansell & Gash, Citation2007; Berardo, Citation2008; Calanni et al., Citation2014; Chen, Citation2010; Emerson et al., Citation2012; Imperial, Citation2005; Rethemeyer & Hatmaker, Citation2008; Vangen & Huxham, Citation2003). On the other hand, cooperators may harbor distrust towards each other due to self-serving or opportunistic motives and actions. It’s essential to address distrust stemming from opportunism (Guo et al., Citation2017), as it can jeopardize and undermine cooperative sustainability. Yet, a complete absence of distrust can also introduce vulnerabilities. Excessive trust, coupled with minimal distrust, can lead to complacency, especially within an imbalanced power dynamic (Raza-Ullah, Citation2021; Raza-Ullah & Kostis, Citation2020; Schiffling et al., Citation2020). In essence, trust and distrust coexist, each influencing organizational dynamics and the overarching coopetition relationship in distinct ways.

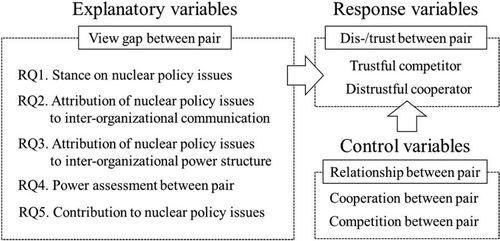

Still, despite the plethora of previous studies exploring the multidimensional aspects of coopetition, trust, and distrust, the two coexisting and ambivalent pairs (i.e., ambivalent behavior such as competition and cooperation, and ambivalent attitude/mindset such as trust and distrust) have not been expressively synthesized into two paradoxical relationships, namely trustful competition and distrustful cooperation. Therefore, this study employs trustful competition and distrustful cooperation as the two paradoxical relationships in coopetition, using them as response variables (see Figure for all variables and research questions).

2.3. Explanatory variables of (Dis)trustworthy coopetition: view gap between pair

Coopetition is linked to both individual organizational performance and dyadic relationships characterized by trust and distrust (Czakon et al., Citation2020; Lascaux, Citation2020). In terms of the antecedents and drivers that contribute to trustful relationships, numerous factors have been identified. These include internal factors such as intention, capability, and prediction, as well as external factors like third-party legitimation (Czakon & Czernek-Marszałek, Citation2016). Among various dimensions and types of possible explanatory variables for the trustworthy coopetition, we focus more on how each organization in policy network views the internal and external environment, and how such views differ in dyadic relationship and how this influences trust and distrust in each other. Such a view of internal/external environments is a kind of frame or framing which has various types, such as substantive, outcome, aspiration, process, identity, characterization, and loss—gain frames (Gray, Citation1997).

The impacts of views or frames on trust or distrust have been studied by many. For instance, trust is built in various contexts that include economic/calculus-based and social/knowledge-based ones (Castaldo & Dagnino, Citation2009). And distrust can be driven by category (Kramer, Citation1999), stereotype or prejudice (Devine, Citation1989; Dovidio et al., Citation2008; Kramer, Citation2004; Lewicki et al., Citation2007; Lumineau, Citation2017; Russell & Russell, Citation2010), characterization framing (Gray, Citation1997), and also by whether to be out-group or not (Brewer, Citation1979, Citation1999; Brewer & Kramer, Citation1985). Further, a network actor’s perception of other actors is significant, as the actor’s mindset will influence how they identify other actors—either as mere competitors or as collaborators—through the lens of coopetition (Czakon & Czernek-Marszałek, Citation2021). Besides the impacts of the frame on trust, distrust, and coopetition, even the gap of frames or views in a dyadic relationship may matter. For instance, distrust can be driven by view gap or frame mismatch (Kaufman & Smith, Citation1999; Kaufman et al., Citation2003; Lee, Citation2021; Lewicki et al., Citation2007). In short, trust and distrust between the network actors can be generated and reinforced by (1) how an actor forms his or her point of view on the situation from various perspectives; and (2) how an actor’s point of view corresponds to (matches or does not match) other actor’s. So, the gap of the network actors’ points of view (i.e., view gap) may work as an explanatory variable of their mutual trust and distrust in coopetition relationship.

In relation to devising research questions and models framed around policy network actors, this study delved into the variation in perspectives within dyadic relationships. These relationships served as explanatory variables spanning four sequential criteria pivotal to organizational decision-making and activities: (1) “What values do we pursue?” (stance on policy issues: e.g., Dagnino, Citation2009; Lewicki, Citation2006); (2) “What are the causes of the policy issues we face?” (attribution of policy issues to inter-organizational communication and power structure: e.g., Mandell et al., Citation2017; Waardenburg et al., Citation2020); (3) “What resources do we have to handle the policy issues?” (power assessment: e.g., Kang & Eun Park, Citation2017; Park & Rethemeyer, Citation2014); and (4) “What do we do for the policy issues?” (contribution to policy issues: e.g., Lee et al., Citation2016; Veenstra, Citation2002).

In addition, since there is limited literature or theoretical framework that clearly supports the arguments about the two paradoxical relationships in a network—trustful cooperation and distrustful competition—it becomes challenging to predict the directions and magnitudes of associations between variables. In a situation like this, where it’s difficult to formulate specific directional hypotheses due to the complex nature of the subject, research questions may be formed in an open-ended format (Lee et al., Citation2022). Therefore, this study took an exploratory approach, adopting an open-ended format for the research questions rather than presenting structured hypotheses, as follows.

2.4. View gap between pair in the stance on policy issues

The first set of explanatory variables is the view gap between a pair in terms of the stance on policy issues. Interest or goal incongruence between or among actors is one of the drivers of coopetition (Dagnino, Citation2009). Further, having the same identity or having a compatible mission enhances trustworthiness (Schindler-Rainman, Citation1981; Williams, Citation2001). On the contrary, incongruence between network actors in terms of values, interests, or goals may engender distrust (Hardin, Citation2004; Larson, Citation2004; Lewicki, Citation2006; Sitkin & Roth, Citation1993; Ullmann-Margalit, Citation2004). In this study, the stance in-/congruence is assessed in three domains: (1) nuclear risk management; (2) gains from nuclear development; (3) national strategy of nuclear development.

RQ1.

How does the dyadic gap of the stance on nuclear policy issues (i.e., dyadic gap of assessments on nuclear risk management, gains from nuclear development, and national strategy of nuclear development) influence the relationship outcomes—trustful competition and distrustful cooperation?

2.5. View gap between pair in the attribution of policy issues to inter-organizational communication

Since Heider (Citation1958) began to systematically build attribution theory, the problem of attribution has been widely studied in order to explain individual and social phenomena (Crandall et al., Citation2007; Kwan & Chiu, Citation2014). According to the theory, a problem can be attributed to internal factors (e.g., effort, ability) or external ones (e.g., situation, social pressure), but such attribution can be biased. In this regard, attribution fallacy (Kramer, Citation1994) or bounded rationality (Lewicki et al., Citation1998) is thought to be a driver of dis-/trust. Also, considering the three components of trustworthiness—ability, benevolent, and integrity (Mayer et al., Citation1995), what a network actor attributes policy issues to may represent the actor’s reasoning ability and traits. Therefore, the view gap of attribution of policy issues is presumed to influence trust or distrust in a dyadic relationship. When it comes to the objects of attribution in networks, we can think of multi-organizational process of communication and decision making that may influence the network dynamics (Head, Citation2008; Mandell et al., Citation2017). In this study, two kinds of attribution to inter-organizational communication are examined: (1) policy communications; and (2) rationality of policy decisions.

RQ2.

How would the dyadic gap of the attribution of nuclear policy issues to inter-organizational communication (i.e., dyadic gap of assessments on policy communication, and rationality of policy decisions) influence the relationship outcomes—trustful competition and distrustful cooperation?

2.6. View gap between pair in the attribution of policy issues to inter-organizational power structure

As another object of attribution in network, power structure among multiple organizations (i.e., governance and inter-organizational influences) plays an important role in collaborative network (Poocharoen & Ting, Citation2015; Waardenburg et al., Citation2020). Therefore this study examines the attribution to three levels of political and governing structure: (1) politics in ministries, which oversee the public organizations studied in this research; (2) political influence on focal organization; and (3) ministry influence on focal organization.

RQ3.

How would the dyadic gap of the attribution of nuclear policy issues to inter-organizational power structure (i.e., dyadic gap of assessments on politics in ministries, political influence on focal organization, and ministry influence on focal organization) influence the relationship outcomes—trustful competition and distrustful cooperation?

2.7. View gap between pair in the power assessment

Reciprocity is one of the keys to trust in networks (Park & Rethemeyer, Citation2014; Rethemeyer & Hatmaker, Citation2008). In this regard, power symmetry between organizations enhance interdependence and reciprocal relationships (Baur et al., Citation2010). On the other hand, in a transactional relationship between network actors, an actor with more power has less incentive to reciprocate the counterpart (Hardin, Citation2004; Kramer, Citation1998). So, power asymmetry may lead to lessened trust (Hurley, Citation2006; Kramer, Citation1999) or even distrust (Hardin, Citation2004; Kang & Eun Park, Citation2017; Kramer & Wei, Citation1999). In short, status heterogeneity discourages collaboration, but a similarity of status enhances trust (Soekijad & De’joode, Citation2009). In this study, the impacts of two kinds of power assessment gap are explored: (1) dyadic gap of self-assessments by focal and partner organization and (2) the gap between focal organization’s self-assessment and partner organization’s assessment of focal organization.

RQ4.

How does the dyadic gap of the power assessment between pair (i.e., dyadic gap of self-assessments by focal and partner organization, and the gap of focal organization’s self-assessment and partner organization’s assessment of focal organization) influence the relationship outcomes—trustful competition and distrustful cooperation?

2.8. View gap between pair in the contribution to policy issues

Degrees of participation in collective tasks influence the propensity to trust (Lee et al., Citation2016; Shah, Citation1998; Stolle, Citation1998; Veenstra, Citation2002). On the contrary, exploitive behavior is one of the drivers of distrust (Triandis et al., Citation1975). In this study, the dyadic gap of assessments are examined in two domains: (1) participation in policy process and (2) cooperation with other peer organizations in the network.

RQ5.

How would the dyadic gap of the contribution to nuclear policy issues (i.e., dyadic gap of assessments on participation in policy process, and cooperation with other peer organizations in the network) influence the relationship outcomes—trustful competition and distrustful cooperation?

2.9. Besides the explanatory variables: relationship between pair—competition, cooperation

In studying factors behind trust (or distrust), the causality between dis-/trust and the arguable drivers may be not always clear, so the reverse causality is not totally excluded (Klijn et al., Citation2010). In exploring the drivers of trustful competition and distrustful cooperation, we know that we can trust competitors simply because we are also cooperating with them. And we can distrust cooperators because we also compete with them (Gamson, Citation1968; Triandis et al., Citation1975). Thus, to better answer the research questions by accounting for the naturally competing and cooperating environments (i.e., coopetition), we need to extract the distinct features of cooperative relationships among competitors and competitive relationships among cooperators. Accordingly, our research questions can be succinctly rephrased as follows: What factors influence our trust in competitors, regardless of whether we cooperate with them? What factors influence our distrust in cooperators, regardless of whether we compete with them? In this context, this study controls for the degree of cooperation to identify the explanatory variables for trust in competitors. Likewise, we control for the degree of competition when exploring the factors that drive distrust in cooperators.

3. Methods

3.1. Case

The research questions were addressed by examining the nuclear policy network in South Korea. This network is characterized by the relationships among stakeholders seeking to influence the South Korean government’s decisions on the design and implementation of nuclear energy policy. Since the 1970s, the Korean government has consistently prioritized nuclear technology development and policy, leading to the construction of nuclear power plants. Even with growing concerns about safety and sustainability, by the 2000s, Korea emerged as a predominantly nuclear-dependent country, with nearly 30% of its electric power sourced from nuclear energy. Presently, stakeholders within the nuclear policy network engage in coopetition, focusing on three primary issues: denuclearization, nuclear waste disposal, and the development of the nuclear industry.

The first major issue is denuclearization and nuclear power safety. Like many other countries, the 2011 Fukushima disaster sparked a fierce discussion regarding denuclearization in South Korea. Since then, nuclear safety and reliability has become a top priority. Thus, multiple institutions in the private and public sector have joined together for two purposes: to further research, educate, train and advance system maintenance; and also to enhance citizens’ awareness of the problem.

The second major issue is nuclear waste disposal. There are various kinds of radioactive waste, such as low, middle, and high level radioactive and radioisotope waste, and there are a variety of causes and disposal methods for each type of waste. Radioisotope waste is generated by around 7,473 domestic organizations that include hospitals, research institutes, educational institutes and general companies. This waste is collected and managed by a few public institutions. When it comes to high level radioactive waste management, which has more serious risks, there is a high degree of cooperative effort by government agencies and public institutions to conduct research for radioactive waste and also to encourage the general public to participate in the policy process for conflict resolution.

The third issue of nuclear policy is the development and export of the Korean nuclear reactor. Although the international market of nuclear power plants used to be led by a few private companies before the 2000’s, the market became a competition among states since the turn of the century. In South Korea, many organizations in the private and public sector cooperate and also compete for the development and export of plants, components and services, and also include small reactors and research reactors.

In summary, the nuclear-related public institutions researched in this article share some common ground: (1) each of them is a semi-independent institution under the influence of different government ministries that are in a coopetition relationship (e.g., Ministry of Science and ICT; Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy); (2) they cooperate and compete with one another over shared or conflicting interests in terms of the environment and the economy.

3.2. Data collection and analysis

We employed purposive sampling method, through which organizations that meet the predetermined criteria can be identified and selected (Palinkas et al., Citation2015). In detail, sampling was conducted using the four steps known as the “realist” approach to network boundary specification (Laumann et al., Citation1989). First, we referenced the administrative categories of the Korea Industrial Forum and constructed a sampling frame that included three categories of nuclear-related organizations: (1) public institutions established and funded by the government; (2) central and local government agencies; and (3) academic or non-governmental organizations. Second, in order to set the boundary of a policy network based on the well-informed reviewers’ judgment (Lee & Lee, Citation2023; Rethemeyer, Citation2007), we conducted in-depth interviews with experts in nuclear policies. As a result, employing the “criterion-i” strategy which is to select all cases that meet a predetermined criterion of importance, the first category (i.e., public institutions established and funded by government) was chosen as research subjects because the institutions in this category more intimately interact with one another than those in the other two categories. Third, based on these interviews with experts who can help applying the “typical case” strategy for purposive sampling, we prioritized and chose the top 17 institutions according to their degrees of influence in the nuclear-related policy process (see Table ). The functions of the chosen organizations include service provision, research and technical support, internal and external communication, and safety and environmental advocacy. Fourth, between May and June in 2018, we contacted and surveyed the mid-career staff from each institution who are in charge of public relations or planning because they can best represent their own institutions’ interest and stance.

Table 1. Organizations surveyed in this study

Interviews with the staff were conducted based on informed consent. The staff we approached were posed a mix of structured and open-ended questions. As outlined in Table , respondents assessed response variables, specifically the “trustful competition” and “distrustful cooperation”, which encompass: (1) degrees of trust in competitive relationships and (2) degrees of distrust in cooperative relationships among their peer organizations (i.e., the 17 institutions) within the nuclear policy network. For the explanatory variables, which highlight assessment gaps among networked organizations, respondents used a five-point Likert scale to express their organizations’ perspectives on: (1) stance on nuclear policy issues (including risk management, nuclear-related benefits, and national strategy); (2) attribution of nuclear policy issues to inter-organizational communication; (3) attribution of nuclear policy issues to inter-organizational power structure; (4) power of both their own organization and peer organizations within the network; and (5) contribution to nuclear policy issues. Each of the variables is a composite of multiple sub-items which can represent the various aspects of the concept as presented in Table where the Cronbach alpha notifies the reliability of measurement.

Table 2. Variables and measures

Using the collected data, the response variables were further processed by calculating the assessment gap between the dyadic pairs of organizations. As the data mainly consists of dyadic relationships and peer evaluations among the 17 institutions, the sample size is 272 (i.e., 17 × 16) which represents the number of pair (i.e., focal and partner organization) in the network. Based on the data processed, we ran two models to examine the explanatory variables’ impacts on the two response variables (i.e., trustful competition; distrustful cooperation). The models were analyzed using ordinary least squares regression (OLS) with fixed effects, allowing us to discern potential unique and consistent patterns in each organization’s responses. Having the highly correlated explanatory variables separate into different models, six models were formulated and run as Table shows. In addition, to further examine the unique associations between the variables, we controlled for degrees of competition in models with “trustful competition” as the response variable, and for degrees of cooperation in models with “distrustful cooperation” as the response variable (see Table for the variables’ descriptive statistics).

Table 3. Descriptive statistics and correlations between variables

4. Results

How does the assessment bias or gap between policy network organizations influence their trust or distrust in the context of coopetition? The analysis results are presented in Table and answer the research question. Before explaining the analysis results in detail, the role of the control variables should be reminded of. Focusing on the unique explanatory variables of trustful competition and distrustful cooperation, we should control the possibility that competitors are trusted just because they are also cooperated with, and cooperators are distrusted just because they are also competed. With this in mind, the statistics for the control variables can be explained as predicted: (1) the more cooperation, the more likely trustful a competitor (0.57***, 0.62*** and 0.64*** in model 1, 2 and 3 respectively); (2) the more competition, the more likely there is a distrustful cooperation (0.73***, 0.69*** and 0.59*** for model 4, 5 and 6 respectively). As the two kinds of relationship—cooperation and competition—usually co-exist in dyadic association, these results seem to be common sense.

Table 4. Models on the explanatory variables of trustful competition and distrustful cooperation

Considering the impacts of control variables, as we focus more on the paradoxical phenomena—trustful competition and distrustful cooperation, we utilized two methods: (1) the degree of competition and cooperation were controlled for and (2) we used the dyadic relations in fairly high competition and cooperation, that is, we used the data whose values that were above a threshold [mean—standard deviation] for competition and cooperation, respectively.

Table presents the statistics as the clues to the five research questions. For the first question, “How would the dyadic gap of the stance on nuclear policy issues (i.e., dyadic gap of assessments on nuclear risk management, gains from nuclear development, and national strategy of nuclear development) influence the response variables?” The response variables being trustful competition and distrustful cooperation, there are three sub-items. When it comes to the “view gap of nuclear risk management”, it turns out that a focal organization, even if it is a competitor, is more trusted when it has a positive view on nuclear risk management, so the view gap is more positive (0.14** in model 1). Ironically, a focal organization, even if it is a cooperator, is more distrusted also when it has a more positive view on nuclear risk management, so the view gap has a positive value (0.12*** in model 4). In short, a focal organization is considered to be more trustful and also more distrustful when it has a more confident view on nuclear risk management. For another sub-item of the “view gap of nuclear national strategy”, a focal organization is more distrusted when it has a more positive view on nuclear development so the view gap has a positive value (0.30*** in model 6).

Interpreting the aforementioned findings, the public institutions in the nuclear policy network have two ambivalences: (1) for the assessment of risk management, they trust the more confident partners even in competitive relationships, and at the same time distrust the less cautious partners, even in cooperative relationships; (2) for the assessment of nuclear national strategy, they distrust the more enterprising partners for the promotion of nuclear energy and industry, which is understandable because almost organizations in the nuclear network may pursue the nuclear energy domain’s prosperity, however, they also feared their vulnerability under the denuclearization policy orientation during the former President Moon’s administration. Such pervasive perception of vulnerability under political influence may also appear in the subsequent findings for the research question 2 and 3.

As for the second research question, “How would the dyadic gap of the attribution of nuclear policy issues to inter-organizational communication (i.e., dyadic gap of assessments on policy communication, and rationality of policy decisions) influence the response variables, which are trustful competition and distrustful cooperation?”, the statistical results reveal another interesting patterns of the explanatory variables. When it comes to the view gap of policy communication, a focal organization is more trusted and also more distrusted when it has a more positive view on the policy communications in terms of diversity, ease to join, transparency and fairness of communication channels in the policy process (0.67*** in model 1; 0.14** in model 4), i.e. “Yes, the policy communication channels are diverse, easy to join, transparent and fair”.

On the other hand, for another explanatory variable (the view gap of rationality of policy decisions), the responses have a more clear pattern: A focal organization in competition is more trusted when it has a positive view on the rationality of policy decisions in terms of scientific and economic considerations (0.45*** in model 2; 0.45*** in model 3), i.e., “Yes, the nuclear policies are made rationally”; a focal organization in cooperation is more distrusted when it has a more negative view (−0.12*** in model 5; −0.13*** in model 6), i.e. “No, the nuclear policies are made irrationally”.

For the third research question, “How would the dyadic gap of the attribution of nuclear policy issues to inter-organizational power structure (i.e., dyadic gap of assessments on politics in ministries, political influence on focal organization, and ministry influence on focal organization) influence the response variables—trustful competition and distrustful cooperation?”, the analysis results show that a competitor is more trusted when: (1) it has a more critical view on politics in government ministries which oversee the public institutions (0.32** in model 1; 0.74*** in model 2; 0.66*** in model 3), i.e., “Yes, the government ministries that oversee my organization are much influenced by political interests”; (2) it has a more negative view on political influence on the focal organization (−1.13*** in model 1; −1.99*** in model 2; −1.97*** in model 3), i.e., “No, my organization is not seriously influenced by national politics”. On the other hand, a cooperator seems to be more distrusted when: (1) it has a less critical view on politics in government ministries that oversee the public institutions (−0.62*** in model 4; −0.97*** in model 5; −1.01*** in model 6), i.e. “No, the government ministries that oversee my organization are unlikely influenced by political interests”; (2) it has a more positive view on political influence on the focal organization (0.40*** in model 5; 0.36** in model 6), i.e., “Yes, my organization is seriously influenced by national politics”; (3) it has a more positive view on ministry influence (1.29*** in model 4; 1.46*** in model 5; 1.24*** in model 6), i.e. “Yes, my organization is seriously influenced by ministries that oversee us”.

A common thing in the findings for research question 2 and 3 is that external attribution (i.e., accusing external factors such as inter-organizational communication and political influences) has a positive association with distrustfulness, while internal attribution having a positive association with trustfulness. In detail, a more trusted competitor tends to take external influences less seriously, while still realistically assessing its overseer (government ministry) being influenced by external political forces. The attribution pattern is the opposite for a more distrusted cooperator that takes and accuses external influences more seriously.

Regarding the fourth research question, which is: How would the dyadic gap of the power assessment between pair (i.e., dyadic gap of self-assessments by focal and partner organization, and gap of focal organization’s self-assessment and partner organization’s assessment of focal organization) influence the response variables that are trustful competition and distrustful cooperation?, the analysis reveals two major findings. First, when the view gap of power between the focal and partner organization is more negative (−0.36*** in model 6) (i.e., a focal organization is considered less powerful than a partner one), the focal organization is more distrusted, even in cooperation. Second, when the gap between the focal organization’s self-assessment of power and partner organization’s assessment of focal organization’s power is more negative (−0.31*** in model 5) (i.e., a focal organization considers itself to be less influential than a partner considers the focal organization), the focal organization is more distrusted, even in cooperation.

As for the last research question, “How would the dyadic gap of the contribution to nuclear policy issues (i.e., dyadic gap of assessments on participation in policy process, and cooperation with other peer organizations in the network) influence the response variables—trustful competition and distrustful cooperation?”, the analysis results provide two answers. First, when the view gap of participation in the policy process is more negative (−0.45*** in model 2; −0.43*** in model 3) (i.e., a focal organization considers itself to have participated in a policy process less actively than a partner one), the focal organization is more trusted by the partner one in competition. On the contrary, the focal organization is more distrusted, even in cooperation when it considered itself to be more actively participating in the policy process than a partner organization (0.40*** in model 5; 0.45*** in model 6). Second, when the view gap of cooperation with other organizations in a network is more negative (i.e., a focal organization has an underestimation of its contribution to the policy network than a partner one), the focal organization is more trusted in competition (−1.22*** in model 1).

5. Discussion and conclusion

Coopetition might be prevalent in policy networks in which multiple organizations cooperate and compete with one another. The analysis in this study reveals the uniqueness of the nuclear-related policy network in South Korea where organizations within these networks hold varied interests in the public goods market: (1) needs for cooperation for market expansion, (2) needs for competition over market allocation, and (3) needs for compliance with diverse political influences in the hierarchical governance. In addition to the behavioral ambivalence (competition and cooperation), the ambivalent attitude and mindset (trust and distrust) is also observable in the policy network (Czakon et al., Citation2020; Kostis & Näsholm, Citation2020; Lascaux, Citation2020; Schiffling et al., Citation2020), where trust and distrust are built and interact in diverse ways according to the different levels and phases of network relationship (Chai et al., Citation2020; Czakon & Czernek-Marszałek, Citation2016; Czakon et al., Citation2022; Nielsen, Citation2004). So, with these ambivalent interactions in policy networks, it would be natural to think of the presence of two paradoxical relationships: trustful competition and distrustful cooperation.

However, the combinations of the two ambivalent pairs—competition and cooperation, and trust and distrust—such as trustful competition and distrustful cooperation, warranted deeper examination. Concurrently, the impacts of policy network actors’ perceptions on their paradoxically ambivalent relationships have not yet received due attention. In this regard, this study explored how the gap between policy network actors’ points of view influences the two paradoxical relationships (trustful competition and distrustful cooperation).

The results of this study imply two major points. First, the degrees of the assessment gap between nuclear-related organizations in South Korea may lead to trust in competition and also to distrust in cooperation. Second, as the view gaps beget trust in competition, as well as distrust in cooperation, what matters in coopetition in policy network is not whether there is a gap between the network actors’ points of view, but when, where and how much such a gap exists so that it can be beneficial or harmful to the coopetition.

In detail, as summarized in Table , it turned out there are similarities and differences in the explanatory variables of trust and distrust in coopetition. And such, the findings of this study imply several points for “trustworthy coopetition” in policy network in terms of self- and environment-assessments. To begin with, there are several characteristics of a focal organization that is more trusted by its competitor. When compared to their partner organizations in competition, the “trustful competitors” are: (1) more cautious of technological risks, (2) more introspective, because they are less likely attributing policy problems to external environments (i.e., policy communication channels, rationality of policy decisions in policy network, and political influence on focal organizations), and (3) having a more realistic and humble assessment of their contributions to policy problems. And the “distrustful cooperators” tend to have the opposite characteristics.

Table 5. Conditions of trustworthy Coopetitor

In practice, some public organizations within South Korea’s nuclear policy network have garnered greater trust by investing significantly in introspective self-innovation. This trend is now further amplified by a national system that requires public organizations to undergo an annual performance evaluation designed to measure and enhance process and performance quality. Based on the organizational categorization in Table , organizations with functions in “communications” and “safety and environmental advocacy” tend to foster more trustful relationships, nurtured by an open and receptive environment. In contrast, organizations focused on “service provision” and “research and technical support”, where differing and entrenched opinions on technical standards might conflict, often find themselves in more distrustful relationships.

Besides the divergent explanatory variables of trust and distrust, there are also common elements. Specifically, the likelihood of becoming a trustful competitor and distrustful cooperator has risen together in two cases: (1) when a focal organization assesses the current nuclear risk management more positively than a partner organization, and (2) when a focal organization assesses the current policy communication channels more positively than a partner organization. In such cases (i.e., positive assessment on risk management and policy communication), ambivalence of trust and distrust became more noticeable. Such ambivalent perception may stem from the unique context of the nuclear policy network. As for the risk management, the technological risk of nuclear energy requires an extremely high level of attention. Therefore, being well prepared for risk control and thereby having a confidence on the risk management is a good thing, however, even a high level of confidence would be regarded as “not enough” and rather might be viewed as an overconfidence or laxness by the network stakeholders. When it comes to the policy communication, having a positive assessment on the current communication could be admired as “not making an excuse” for the unreasonable policy decision making, but it might be also criticized for having an unrealistic attribution of policy problems.

In summary, the paradoxical duality of ambivalent pairs (trustful competition and distrustful cooperation) within coopetitive policy networks suggest several theoretical and practical implications. First, the idea that a competitor can be trustworthy suggests the possibility of a positive relationship even amidst competition. Although inter-organizational competition might be somewhat unavoidable, these competing relationships can—and should—be collaborative for mutual prosperity (Czakon & Czernek-Marszałek, Citation2021). Further, trust plays various roles such as antecedent and moderator between coopetitive relationship and the network’s outcomes (Chai et al., Citation2020; Kostis & Näsholm, Citation2020; Nielsen, Citation2004). Therefore, the real challenge lies in sidestepping destructive competition and nurturing a constructive and trustful counterpart. Second, the notion that a cooperator might be distrustful underscores the importance of vigilance, even in partnerships. Merely superficial cooperation between organizations doesn’t ensure a lasting, positive relationship. Hidden agendas behind such cooperations might foster adverse relations if triggered. This perspective aligns with the argument that distrust has a place in coopetition; it serves as a protective mechanism against the uncertainties inherent in these dual-natured relationships (Raza-Ullah, Citation2021; Raza-Ullah & Kostis, Citation2020; Schiffling et al., Citation2020). Third, the findings of this study suggest common factors that can promote trustful competition and prevent distrustful cooperation, namely, the policy network actors’ realistic assessments of the situation. In other words, a trustworthy participant in the policy network tends to demonstrate an introspective (not making excuses) and grounded confidence (not being overconfident) in terms of risk management, attribution of policy problems, and contribution to those problems.

6. Limitations and future research

Beyond the findings and implications of this study, there are some points that need to be addressed further. Regarding what leads to certain patterns of inter-organizational relationship, the relationship between organizations can be defined and determined by various sources. For instance, inter-organizational relationship might be influenced by official relationship (e.g., contract, transaction, legal oversight) or unofficial one (e.g., sense of homogeneity based on organizational similarities and differences in the network; interpersonal relationships between boundary spanners). Among the various explanatory variables, the significance of interpersonal relationships in inter-organizational trust merits deeper exploration. A foundational assumption of this study is that both response and explanatory variables rely on respondents’ perceptions. This suggests opportunities for future research that might utilize factors beyond mere perceptions. The inherent nature of perception-based data further underscores the necessity for continued investigation. While this study crafted its sampling methods to ensure the representativeness of respondents regarding inter-organizational relationship evaluations, there remains the potential for perceptional biases influenced by individual interpersonal experiences. Consequently, differentiating between inter-organizational and interpersonal relationships could emerge as a critical area for subsequent research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ansell, C., & Gash, A. (2007). Collaborative governance in Theory and practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(4), 543–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum032

- Barber, B. (1983). The logic and limits of trust. The Rutgers University Press.

- Baur, V. E., Arnold, H. G., Elteren, V., Nierse, C. J., & Abma, T. A. (2010). Dealing with distrust and power dynamics: Asymmetric relations among stakeholders in responsive evaluation. Evaluation, 16(3), 233–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389010370251

- Berardo, R. (2008). Generalized trust in multi-organizational policy arenas: Studying its emergence from a network perspective. Political Research Quarterly, 62(1), 178–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912907312982

- Berardo, R., & Scholz, J. T. (2010). Self-organizing policy networks: Risk, partner selection, and cooperation in estuaries. American Journal of Political Science, 54(3), 632–649. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00451.x

- Brandenburger, A. M., & Nalebuff, B. J. (1996). Co-optition. Currency and Doubleday.

- Brewer, M. B. (1979). In-group bias in the minimal intergroup situation: A cognitive-motivational analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 86(2), 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.86.2.307

- Brewer, M. B. (1999). The Psychology of prejudice: Ingroup love and outgroup hate? Journal of Social Issues, 55(3), 429–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00126

- Brewer, M. B., & Kramer, R. (1985). The Psychology of intergroup attitudes and behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 36(1), 219–243. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.36.020185.001251

- Calanni, J. C., Siddiki, S. N., Weible, C. M., & Leach, W. D. (2014). Explaining coordination in collaborative partnerships and clarifying the scope of the belief homophily hypothesis. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 25(3), 901–927. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mut080

- Calò, F., Teasdale, S., Donaldson, C., Roy, M. J., & Baglioni, S. (2018). Collaborator or competitor: Assessing the evidence supporting the role of social enterprise in health and social care. Public Management Review, 20(12), 1790–1814. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1417467

- Castaldo, S., & Dagnino, G. B. (2009). Trust and coopetition: The strategic role of trust in interfirm coopetitive dynamics. In G. B. Dagnino & E. Rocco (Eds.), Coopetition strategy: Theory, experiments and cases (pp. 74–100). Routledge.

- Chai, L., Li, J., Tangpong, C., & Clauss, T. (2020). The interplays of coopetition, conflicts, trust, and efficiency process innovation in vertical B2B relationships. Industrial Marketing Management, 85, 269–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.11.004

- Chen, B. (2010). Antecedents or processes? Determinants of perceived effectiveness of interorganizational Collaborations for Public service delivery. International Public Management Journal, 13(4), 381–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2010.524836

- Cho, J. (2006). The mechanism of trust and distrust formation and their relational outcomes. Journal of Retailing, 82(1), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2005.11.002

- Crandall, C. S., Silvia, P. J., N’Gbala, A. N., Tsang, J. A., & Dawson, K. (2007). Balance theory, unit relations, and attribution: The underlying integrity of heiderian theory. Review of General Psychology, 11(1), 12–30. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.11.1.12

- Czakon, W., & Czernek-Marszałek, K. (2016). The role of trust-building mechanisms in entering into network coopetition: The case of tourism networks in Poland. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.05.010

- Czakon, W., & Czernek-Marszałek, K. (2021). Competitor perceptions in tourism coopetition. Journal of Travel Research, 60(2), 312–335. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519896011

- Czakon, W., Jedynak, P., & Konopka-Cupiał, G. (2022). Trust-and distrust-building mechanisms in academic spin-off relationships with a parent university. Studies in Higher Education, 47(10), 2056–2070. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2022.2122659

- Czakon, W., Klimas, P., & Mariani, M. (2020). Behavioral antecedents of coopetition: A synthesis and measurement scale. Long Range Planning, 53(1), 101875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2019.03.001

- Czakon, W., Srivastava, M. K., Le Roy, F., & Gnyawali, D. (2020). Coopetition strategies: Critical issues and research directions. Long Range Planning, 53(1), 101948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2019.101948

- Czernek, K., & Czakon, W. (2016). Trust-building processes in tourist coopetition: The case of a Polish region. Tourism Management, 52, 380–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.07.009

- Dagnino, G. B. (2009). Coopetition strategy: A new kind of interfirm dynamics for value creation. In G. B. Dagnino & E. Rocco (Eds.), Coopetition strategy: Theory, experiments and cases (pp. 25–43). Routledge.

- Deutsch, M. (1958). Trust and suspicion. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2(4), 265–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/002200275800200401

- Devine, P. G. (1989). Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.1.5

- Dovidio, J. F., Penner, L. A., Albrecht, T. L., Norton, W. E., Gaertner, S. L., & Shelton, J. N. (2008). Disparities and distrust: The implications of psychological processes for understanding racial disparities in health and health care. Disparities and Distrust: The Implications of Psychological Processes for Understanding Racial Disparities in Health and Health Care Social Science and Medicine, 67(3), 478–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.019

- Emerson, K., Nabatchi, T., & Balogh, S. (2012). An integrative framework for collaborative governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 22(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mur011

- Fotaki, M. (2011). Towards developing new partnerships in Public services: Users as consumers, Citizens and/or co-producers in Health and Social care in England and Sweden. Public Administration, 89(3), 933–955. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2010.01879.x

- Gamson, W. A. (1968). Power and discontent (Vol. 124). Dorsey Press.

- Gray, B. (1997). Framing and reframing of intractable environmental disputes. In L. Roy, B. Robert, & B. Sheppard (Eds.), Research on negotiations in organizations (pp. 163–188). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Guo, S., Lumineau, F., & Lewicki, R. J. (2017). Revisiting the Foundations of organizational distrust. Foundations and Trends in Management, 1(1), 1–88. https://doi.org/10.1561/3400000001

- Hardin, R. (2004). Distrust: Manifestations and Management. In R. Hardin (Ed.), Distrust (pp. 3–33). Russell Sage Foundation.

- Hatmaker, D. M., & Rethemeyer, R. K. (2008). Mobile trust, enacted relationships: Social capital in a state-level policy network. International Public Management Journal, 11(4), 426–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967490802494867

- Head, B. W. (2008). Assessing network-based collaborations: Effectiveness for whom? Public Management Review, 10(6), 733–749. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030802423087

- Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. Wiley.

- Hurley, R. F. (2006, September). The decision to trust. Harvard Business Review, 84(9), 55–62.

- Imperial, M. T. (2005). Using collaboration as a governance strategy: Lessons from six watershed Management programs. Administration and Society, 37(3), 281–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399705276111

- Ingold, K., Fischer, M., & Cairney, P. (2017). Drivers for policy agreement in nascent subsystems: An application of the advocacy Coalition framework to fracking policy in Switzerland and the UK. Policy Studies Journal, 45(3), 442–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12173

- Kang, M., & Eun Park, Y. (2017). Exploring trust and distrust as conceptually and empirically distinct constructs: Association with symmetrical communication and Public engagement across four pairings of trust and distrust. Journal of Public Relations Research, 29(2–3), 114–135. Routledge https://doi.org/10.1080/1062726X.2017.1337579

- Kaufman, S., Elliott, M., & Shmueli, D. (2003). Frames, framing and reframing. Retrieved from http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/framing.

- Kaufman, S., & Smith, J. (1999). Framing and reframing in land use change conflicts. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, 16(2), 164–180.

- Kim, K. (2018). Coopetition: Complexity of cooperation and competition in dyadic and triadic relationships. Organizational Dynamics, 49(2), 100683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2018.09.005

- Klijn, E. H., Edelenbos, J., & Steijn, B. (2010). Trust in governance networks: Its impacts on outcomes. Administration and Society, 42(2), 193–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399710362716

- Kostis, A., & Näsholm, M. H. (2020). Towards a research agenda on how, when and why trust and distrust matter to coopetition. Journal of Trust Research, 10(1), 66–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/21515581.2019.1692664

- Kramer, R. M. (1994). The sinister attribution error: Paranoid cognition and collective distrust in organizations. Motivation and Emotion, 18(2), 199–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02249399

- Kramer, R. M. (1998). Paranoid cognition in Social systems: Thinking and acting in the Shadow of Doubt. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2(4), 251–275. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0204_3

- Kramer, R. M. (1999). Trust and distrust in organizations: Emerging perspectives, enduring questions. Annual Review of Psychology, 50(1), 569–598. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.569

- Kramer, R. M. (2004). Collective paranoia: Distrust between Social groups. In R. Hardin (Ed.), Distrust (pp. 136–166). Russell Sage Foundation.

- Kramer, R. M., & Wei, J. (1999). Social uncertainty and the problem of trust in Social groups: The Social self in Doubt. In T. R. Tyler, R. M. Kramer, & O. P. John (Eds.), The psychology of the social self (pp. 145–168). Erlbaum.

- Kwan, L. Y., & Chiu, C. (2014). Holistic versus analytic thinking explains collective culpability attribution. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 36(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2013.856790

- Larson, D. W. (2004). Prudent, if not always wise. In R. Hardin (Ed.), Distrust (pp. 34–59). Russell Sage Foundation.

- Lascaux, A. (2020). Coopetition and trust: What we know, where to go next. Industrial Marketing Management, 84, 2–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.05.015

- Laumann, E., Marsden, P. V., & Prensky, D. (1989). The boundary specification problem in Social network analysis. In C. Linton, D. Freeman, R. White, & A. K. Romney (Eds.), Applied Network Analysis: A methodological introduction (pp. 18–34). Sage Publications.

- Lavie, D. (2008). Capturing Value from Alliance Portfolios. Organizational Dynamics, 38(1), 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2008.04.008

- Leach, W. D., & Sabatier, P. A. (2005). To trust an adversary: Integrating rational and psychological models of collaborative policymaking. American Political Science Review, 99(4), 491–503. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000305540505183X

- Lee, J. (2021). When illusion met illusion: How interacting biases affect (dis)trust within coopetitive policy networks. Public Administration Review, 81(5), 962–972. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13351

- Lee, I., Felock, R. C., & Lee, R. (2012). Competitors and cooperators: A micro-level analysis of regional economic development collaboration networks. Public Administration Review, 72(2), 253–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02501.x

- Lee, J., Kim, S., & Lee, J. (2022). Public vs. Public: Balancing the competing Public values of Participatory Budgeting. Public Administration Quarterly, 46(1), 39–66. https://doi.org/10.37808/paq.46.1.3

- Lee, J., & Lee, J. (2018). When you trust and distrust the other side: The roles of asymmetric power in a policy network. Annual conference of Academy of Management (AoM), Chicago, IL.

- Lee, J., & Lee, J. (2023). Compatibility of the incompatible: How does asymmetric power lead to coexistence of trust and distrust in adversarial policy networks? International Journal of Public Administration, 1–16. In press. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2022.2094410

- Lee, H., Robertson, P. J., Lewis, L., Sloane, D., Galloway-Gilliam, L., & Nomachi, J. (2016). Trust in a cross-sectoral interorganizational network: An empirical investigation of antecedents. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(4), 609–631. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764011414435

- Leifeld, P., & Schneider, V. (2012). Information exchange in policy networks. American Journal of Political Science, 56(3), 731–744. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00580.x

- Lenferink, S., Tillema, T., & Arts, J. (2013). Public-private interaction in contracting: Governance strategies in the competitive dialogue of Dutch infrastructure projects. Public Administration, 91(4), 928–946. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12033

- Lewicki, R. J. (2006). Trust and Distrust. In A. K. Schneider, & C. Honeyman (Eds.), The Negotiator’s fieldbook (pp. 191–202). American Bar Association.

- Lewicki, R. J., Barry, B., & Saunders, D. M. (2007). Essentials of negotiation. McGraw-Hill.

- Lewicki, R. J., McAllister, D. J., & Bies, R. I. (1998). Trust and distrust: New relationships and realities. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 438–458. https://doi.org/10.2307/259288

- Loorbach, D. (2010). Transition Management for sustainable development: A prescriptive, complexity-based governance framework. Governance, 23(1), 161–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2009.01471.x

- Lumineau, F. (2017). How contracts influence trust and distrust. Journal of Management, 43(5), 1553–1577. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314556656

- Lundin, M. (2007). Explaining cooperation: How resource interdependence, goal congruence, and trust affect joint actions in policy implementation. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 17(4), 651–672. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mul025

- Mandell, M., Keast, R., & Chamberlain, D. (2017). Collaborative networks and the need for a new management language. Public Management Review, 19(3), 326–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2016.1209232

- Marques, R. C., & Berg, S. (2011). Public-private partnership contracts: A tale of two cities with different contractual arrangements. Public Administration, 89(4), 1585–1603. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2011.01944.x

- Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, D. F. (1995). An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734. https://doi.org/10.2307/258792

- McEvily, B., Radzevick, J. R., & Weber, R. A. (2012). Whom do you distrust and how much does it cost? An experiment on the measurement of trust. Games and Economic Behavior, 74(1), 285–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geb.2011.06.011

- Ménard, C. (2004). The Economics of hybrid organizations. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 160(3), 345–376. https://doi.org/10.1628/0932456041960605

- Muthusamy, S. K., & White, M. A. (2005). Learning and knowledge transfer in strategic alliances: A Social exchange View. Organization Studies, 26(3), 415–441. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840605050874

- Nielsen, B. B. (2004). The role of trust in collaborative relationships: A multi-dimensional approach. Management, 7(3), 239–256. https://doi.org/10.3917/mana.073.0239

- O’Reilly, T. (2011). Government as a platform. Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization, 6(1), 13–40. https://doi.org/10.1162/INOV_a_00056

- Osipovič, D., Allen, P., Shepherd, E., Coleman, A., Perkins, N., Williams, L., Sanderson, M., & Checkland, K. (2016). Interrogating institutional change: Actors’ attitudes to competition and cooperation in Commissioning Health services in England. Public Administration, 94(3), 823–838. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12268

- Ostrom, E. (1998). A behavioral approach to the rational choice theory of collective action: Presidential address, American political Science association, 1997. The American Political Science Review, 92(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/2585925

- Otnes, C., Lowrey, T. M., & Shrum, L. J. (1997). Toward an understanding of consumer ambivalence. Journal of Consumer Research, 24(1), 80–93. https://doi.org/10.1086/209495

- Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(5), 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

- Park, H. H., & Rethemeyer, R. K. (2014). The politics of connections: Assessing the determinants of Social structure in policy networks. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 24(2), 349–379. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mus021

- Poocharoen, O., & Ting, B. (2015). Collaboration, co-production, networks: Convergence of theories. Public Management Review, 17(4), 587–614. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.866479

- Priester, J. R., & Petty, R. E. (1996). The gradual threshold model of ambivalence: Relating the positive and negative bases of attitudes to subjective ambivalence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(3), 431–449. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.3.431

- Putnam, R. D. (2001). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Touchstone Books by Simon & Schuster.

- Raza-Ullah, T. (2021). When does (not) a coopetitive relationship matter to performance? An empirical investigation of the role of multidimensional trust and distrust. Industrial Marketing Management, 96, 86–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2021.03.004

- Raza-Ullah, T., & Kostis, A. (2020). Do trust and distrust in coopetition matter to performance? European Management Journal, 38(3), 367–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2019.10.004

- Rethemeyer, R. K. (2007). Policymaking in the Age of Internet: Is the Internet Tending to make policy networks more or less inclusive? Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 17(2), 259–284. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mul001

- Rethemeyer, R. K., & Hatmaker, D. M. (2008). Network Management reconsidered: An inquiry into Management of network structures in Public Sector service provision. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(4), 617–646. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum027

- Ritala, P., Valimaki, K., Blomqvist, K., & Henttonen, K. (2009). Intrafirm coopetition, knowledge creation and innovativeness. In G. B. Dagnino & E. Rocco (Eds.), Coopetition strategy: Theory, experiments and cases (pp. 64–73). Routledge.

- Rotter, J. B. (1971). Generalized Expectancies for Interpersonal Trust. American Psychologist, 26(5), 443–452. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0031464

- Rotter, J. B. (1980). Interpersonal trust, trustworthiness, and gullibility. American Psychologist, 35(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.35.1.1

- Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 393–404. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1998.926617

- Rubery, J., Grimshaw, D., & Hebson, G. (2013). Exploring the limits to Local Authority Social care Commissioning: Competing pressures, variable practices, and unresponsive providers. Public Administration, 91(2), 419–437. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2012.02066.x

- Russell, C. A., & Russell, D. W. (2010). Guilty by stereotypic association: Country animosity and brand prejudice and discrimination. Marketing Letters, 21(4), 413–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-009-9097-y

- Schiffling, S., Hannibal, C., Fan, Y., & Tickle, M. (2020). Coopetition in temporary contexts: Examining swift trust and swift distrust in humanitarian operations. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 40(9), 1449–1473. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-12-2019-0800

- Schindler-Rainman, E. (1981). Toward collaboration—risks we need to take. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 10(3–4), 120–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/089976408101000310

- Shah, D. V. (1998). Civic engagement, interpersonal trust, and television use: An individual level assessment of social capital. Political Psychology, 19(3), 469–496. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00114

- Sitkin, S. B., & Roth, N. L. (1993). Explaining the limited effectiveness of legalistic ‘remedies’ for trust/distrust. Organization Science, 4(3), 367–392. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.4.3.367

- Soekijad, M., & De’joode, R. V. (2009). Coping with coopetition in knowledge-intensive multiparty alliances: Two case studies. In G. B. Dagnino & E. Rocco (Eds.), Coopetition strategy: Theory, experiments and cases (pp. 146–165). Routledge.

- Stack, L. C. (1988). Trust. In H. London & J. E. Exner (Eds.), Dimensionality of personality (pp. 561–599). Wiley.

- Stolle, D. (1998). Bowling together, bowling alone: The development of generalized trust in voluntary associations. Political Psychology, 19(3), 497–525. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00115

- Tardy, C. H. (1988). Interpersonal evaluations: Measuring attraction and trust. In C. H. Tardy (Ed.), A handbook for the study of human communication (pp. 269–283). Ablex Publishing.

- Thompson, M. M., Zanna, M. P., & Griffin, D. W. (1995). No, Let’s not be indifferent about ‘attitudinal’ ambivalence. In R. E. Petty & J. A. Krosnick (Eds.), Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences (pp. 361–386). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Triandis, H. C., Feldman, J. M., Weldon, D. E., & Harvey, W. M. (1975). Ecosystem distrust and the hard-to-employ. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60(1), 44–56. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0076349

- Ullmann-Margalit, E. (2004). Trust, distrust, and in between. In R. Hardin (Ed.), Distrust (pp. 60–82). Russell Sage Foundation.

- Vangen, S., & Huxham, C. (2003). Nurturing collaborative relations building trust in interorganizational collaboration. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 39(1), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886303039001001

- Veenstra, G. (2002). Explicating social capital: Trust and participation in the civil space. Canadian Journal of Sociology / Cahiers Canadiens de Sociologie, 27(4), 547–572. https://doi.org/10.2307/3341590

- Waardenburg, M., Groenleer, M., de Jong, J., & Keijser, B. (2020). Paradoxes of collaborative governance: Investigating the real-life dynamics of multi-agency collaborations using a quasi-experimental action-research approach. Public Management Review, 22(3), 386–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1599056

- Wales, W. J., Parida, V., & Patel, P. C. (2013). Too much of a good thing? Absorptive capacity, firm performance, and the moderating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Strategic Management Journal, 34(5), 622–633. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2026

- Willem, A., & Lucidarme, S. (2014). Pitfalls and challenges for trust and effectiveness in collaborative networks. Public Management Review, 16(5), 733–760. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2012.744426

- Williams, M. (2001). In whom we trust: Group membership as an affective context for trust development. The Academy of Management Review, 26(3), 377–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/259183

- Worchel, P. (1979). Trust and Distrust. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The Social Psychology of Intergroup (pp. 174–187). Brooks Cole Publishing.