Abstract

COVID-19 has caused severe economic crises, unemployment, and disruptions to the global tourism industry. This study aims to establish the current body of knowledge on crisis management in tourism published from to 2001–2021, with the objective of providing research avenues on how to manage crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The study shows that crisis management in tourism is based on the survival strategies of the tourism subsectors in Europe, Asia, the USA, and Australia. A universal approach is limited, indicating the immaturity of the research in this area. There is a need to expand the analysis including approaches in Africa and strategies of the tourism subsectors during the COVID-19 pandemic. This knowledge of the local tourism subsectors that focus need to be put upon are limited. The literature is fragmented, lacks precision, and is a common approach that the tourism industry should follow during uncertain situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The absence of a theoretical framework on crisis management that is inclusive of what tourism could rely on during such situations is a concern. This study contributes to the framework that tourism researchers, policymakers, and practitioners could rely upon when dealing with crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

IMPACT STATEMENT

COVID-19 has caused severe economic crisis, unemployment, and disruptions for the tourism industry globally. This study aims to establish the current body of knowledge on crisis management in tourism published from 2001-2021, with objective to provide research avenues on how to manage crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

The study shows that crisis management in the tourism is based on survival strategies of the tourism subsectors in the context of Europe, Asia, USA, and Australia. A universal approach is limited, indicating the immaturity of research in the area. There is need to expand the analysis including approaches in Africa and strategies of tourism subsectors during the COVID-19 pandemic. This knowledge of the local tourism subsectors that focus need to be put upon are limited. The study contributes with a framework that the tourism researchers, policy makers and practioners could rely upon when dealing with crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

On December 31, 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) was informed of cases of pneumonia caused by a virus, referred to as the COVID-19 pandemic (WHO, Citation2020). It provides striking lessons to the tourism industry, policymakers, and researchers regarding the effects of global change (Gössling, Scott, & Hall, Citation2020). There is little doubt that the COVID-19 pandemic is an exemplar of contemporary crises, unparalleled in its magnitude, bringing tourism flows to a halt throughout 2020 and into 2021 (Cheer et al., Citation2021). The situation forced destinations to seized operating following lockdowns, travel bans, bookings cancelations, and limited logistics (Fotiadis et al., Citation2021). Vaccine certificates and negative PCR tests have boosted hope for recovery, but challenges continue to remain (Mills & Rüttenauer, Citation2021; OECD, Citation2020).

A Crisis is not new to the tourism industry; however, its capability and ability to deal with complex and critical situations are limited (Santana, Citation2004). For instance, the threat of COVID-19 to tourism, is perceived as having more far-reaching consequences than previous crises (Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2020). Its impact on tourism is sustained, and its response is increasingly recognized (Chang & Wu, Citation2021). Two years after the COVID-19 pandemic, countries continue to struggle with the fifth and sixth waves with new variants, and varying degrees of success in vaccinating their populations (Gössling & Schweiggart, Citation2022). Signals regarding the next wave continues globally, most visibly in incidence in France (+74%), Great Britain (+58%), Germany (+25%), and the U.S (+16%) (Sheresheva & Oborin, Citation2022).

Although previous studies are valuable in terms of crisis preparation, recent studies have questioned the efficacy of practices that cannot cover all the stages of a crisis (Huang et al., Citation2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has wreaked havoc on the tourism industry like never before, resulting in massive losses of revenue and jobs worldwide, which exacerbated the sustainability challenges of the tourism industry (Seabra & Bhatt, Citation2022).

Crisis management is a tool for implementing strategies and, responses to recovery, learning and long-term resilience actions (Ritchie & Jiang, Citation2019). At the time of writing no known common approach was available to tackle crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous research conducted on tourism crises, includes how destinations should respond proactively, develop strategies to avoid or cope with crises, and mitigate their impact on destinations (Faulkner, Citation2001; Ritchie, Citation2004; Ritchie & Jiang, Citation2019). This situation is recognized as an opportunity to build a more resilient and sustainable industry in the post pandemic era (Ost & Saleh, Citation2021). Scholars suggest that experience can shape crisis responses in two basic ways: as a way of repeating former routines (Roux-Dufort & Vidaillet, Citation2003: 130) or as a precondition for improvisation and flexibility (Weick, Citation1993).

Considering the significance of tourism in the global economy, investigating how it can be made sustainable in a dramatically changed situation is not only timely but also essential (Chang et al., Citation2020). The challenge is to collectively learn from global trade and accelerate the transformation of tourism (Gössling et al., Citation2020). It is crucial to learn from past crises as a useful reference for dealing with future crises (Chen & Chen, Citation2022).

However, few systematic literature reviews (SLR) have been conducted in the field (Faulkner, Citation2001), which is an objective and, reproducible method for finding answers to a certain research question, by collecting available studies in the area, reviewing, and analyzing their results (Ahn & Kang, Citation2018). Researchers, such as Mair et al. (Citation2016), reviewed 64 articles concerning post-disaster and post-crisis recovery related to destinations and tourist flow; Jiang et al. (Citation2019) on tourism crisis research explored network structures using bibliometric analysis; Ritchie and Jiang (Citation2019) reviewed 142 articles on tourism crisis and disaster management using a narrative synthesis approach, discussing critiques of the existing literature, including a lack of conceptual and theoretical foundation, framework testing, and unbalanced research themes (Leta & Chan, Citation2021). Towards a similar objective, 249 academic publications produced in the first year of the pandemic through January 11, 2021, were reviewed (Yang et al., Citation2021), and evaluated following the systematic review method.

An earlier systematic review on COVID-19 research in tourism and hospitality showed that half of the studies investigated themes such as impacts, psychological effects, sustainability, and creating resilience (Yang et al., Citation2020). Although such reviews on crisis management in tourism have occurred, they have limitations in terms of scope and depth (Ritchie & Jiang, Citation2019). To establish the current body of knowledge in this area, it is essential to conduct a systematic literature review (SLR) to identify, selects and critically appraise research that will help answer questions on the topic (Dewey & Drahota, Citation2016).

This approach will potentially provide significant improvements in the state of the art that could be useful in the building of valid theories (Meredith, Citation1993 in Durst & Zieba, Citation2020), linking to a variety of challenges (Durst & Zieba, Citation2020), which includes exploring the appropriate research tool to obtain a comprehensive summary of the literature (Confente, Citation2015). The aim of this study is to establish the current body of knowledge on crisis management in tourism, with the objective of suggesting avenues for future research that could help tourism handle crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Such a study is important as it contributes to the academic literature on what is known, and what is not yet known about the topic, often to a greater extent than the findings of a single study (Cook et al., Citation1997).

Multiple research studies will be collected and summarized to answer the research questions using a rigorous method (Gough et al., Citation2017). This study will be useful in identifying challenges and new insights for future research on managing crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic in the tourism industry. It aimed to answer the following questions:

RQ1. What research has been conducted in the context of crisis management in the tourism industry during the period 2001–2021?

RQ2. What research methodological approaches, operationalization, research settings, collaboration and communities, and levels of analysis have been conducted in the context of crisis management in the tourism industry during the period 2001–2021?

The literature is outlined, followed by a presentation and description of the research method employed. The findings, discussion and conclusions are presented, along with the implications of the study. It provides insights into the procedures applied to identify the extant research and current knowledge, including the methods and theories used, findings, and gaps in the litetrature. This study contributes to the current knowledge that could be useful to practitioners, policymakers and researchers when dealing with crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Theoretical framework

A crisis is a term that is generally applicable to a variety of situations characterized by unpredictability and unwanted uncertainty that causes disbelief (Stern & Sundelius, Citation2003). A crisis involves a periodic discontinuity, a situation in which the core values of the organisation/systems are under threat and requires critical decision-making (Zamoum & Serra-Gorpe, Citation2017). It is often an unexpected event that poses threats to an organisation, society, or business environment. Events that negatively affect destinations are termed crisis events, and publications discussing the impact of such crisis events on destinations have increased significantly over the years (Goh & Law, Citation2002). For instance, the COVID-19 pandemic is an example of a crisis that presented unprecedented circumstances before the fragile tourism industry, was highly infectious that thwarted the sector, and raised serious questions about the present and future survival of the sector (Kaushal & Srivastava, Citation2021).

Several studies are dedicated to crisis management in tourism, including Meyers (Citation1986) Managing the Nine Crises of Business, Murphy, and Bayley’s (1989) Destination Crisis Management, and Seymour and Moore (Citation2000) Study on Effective Crisis Management. Many studies have focused on resilience in tourism (Filimonau & De Coteau, Citation2020; Prayaq, Citation2018) and risks caused by natural and man-made disasters in tourist destinations (Berdychevsky & Gibson, Citation2015; Ruan, Li & Liu, Citation2017), addressing how destinations can recover from crises (Ritchie, Citation2004; Ritchie & Jiang, Citation2019; Slater, Citation1984).

Most of the research focuses on strategy and planning, including, Booth’s (Citation1993) crisis management strategy and changes in modern enterprises, Drabek’s (Citation1995) tourism disaster planning; Cassedy’s (Citation1991) crisis management planning in travel and tourism, Smith’s (Citation1990) looking beyond contingency planning, Pottorff and Neal (Citation1994) planning and mitigation; Young and Montgomery (Citation1998) crisis management process and planning, and Heath’s (Citation1998) crisis management for managers.

Interest in crisis management in tourism seems to have increased during periods when the demand for travel is highly susceptible to numerous shocks, such as wars, outbreaks of contagious diseases, terrorism, economic fluctuations, currency instability, and energy crises (Maditinos & Vassiliadis, Citation2008). The literature has grown since 2001 with many of the research dedicated to crisis management in tourism joining the conversation (e.g. Henderson, Citation2003; Israeli & Reichel, Citation2003; Hosie & Smith, Citation2004; Henderson & Ng, Citation2004; Ritchie, Citation2004; Evans & Elphick, Citation2005; Andersson, Citation2006; De Sausmarez, Citation2007; Hystad & Keller, Citation2008; Walters & Mair, Citation2012; Orchiston, Citation2012; Paraskevas & Altinay, Citation2013; Calgaro et al., Citation2014; Lew, Citation2014; Avraham, Citation2016; Mair et al., Citation2016; Liu-Lastres et al., Citation2018; Cahyanto et al., Citation2016; Gunter, Citation2016; Avraham & Ketter, Citation2017; Guo et al., Citation2018; Çakar, Citation2018; Novelli et al., Citation2018; Ritchie & Jiang, Citation2019). Much research in this area is concerned with terrorist attacks, natural disasters such as tsunamis and earthquakes, or crises in general (Gani & Singh, Citation2019).

Most research describing the COVID-19 pandemic and its consequences in specific regions, theorizing, and relating it to crisis management remains limited (Nasir et al., Citation2020). Conceptual models for the implementation of creativity- and innovation-based crisis strategies are scarce (Broshi-Chen & Mansfeld, Citation2021). At the time of writing, during the second half of 2021 and mid-2022, threats to the COVID-19 pandemic continue to cause disruptions, especially in the tourism industry. In such critical situations, managers used multiple and, to some extent, unique strategies for decision-making and crisis control (Shamshiri et al., Citation2022). There is a need to review the literature on crisis management in tourism in a ‘systematic’ rigorous process to establish the current body of knowledge including what research methods and theories are used, and findings to help provide the research gap and directions for future research on crisis management that would be useful for policy makers and researchers when dealing with crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Research methodology of the literature review

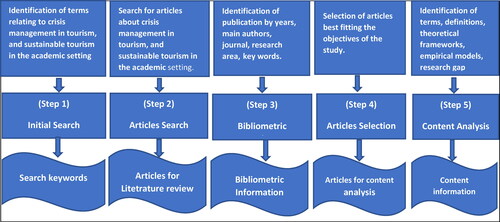

There are many different study designs that could be useful for investigating the research topic; however, a systematic literature review (SLR) is unique for this type of study. SLR identifies, selects, and critically appraises research to answer a clearly formulated question (Dewey & Drahota, Citation2016). The method chosen for this study is inspired by the commonly applied research methods proposed by Jesson et al. (Citation2011), McNulty et al. (Citation2013), Dumay et al. (Citation2016), and Schmitz et al. (Citation2017). The five steps for SLR proposed by Jesson et al. (Citation2011) guided the SLR method applied in this study. The next step was to establish the review protocol ().

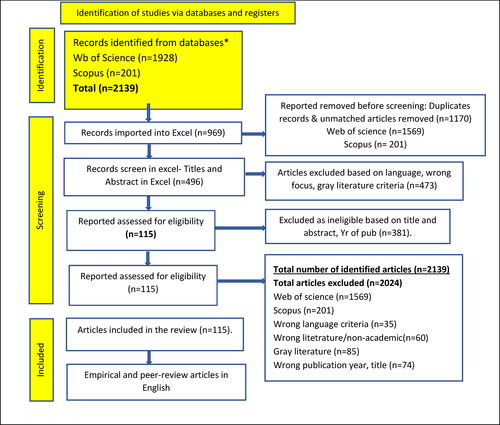

shows the research plan, mapping out the field through a scoping of the articles on the research topic. The inclusion criteria were empirical and peer-reviewed papers published in English, the predominant language in international peer-reviewed academic publishing (Kristjánsdóttir et al., Citation2017). Research on tourism impact, gray literature such as reports and non-academic research, opinion papers, book reviews, letters, and papers published in other languages were excluded from the analysis.

Scientific research built on previous studies and scientifically proven knowledge is widely accessible owing to digitalized publications, extensive citation coverage, and several literature databases (Kumpulainen & Seppänen, Citation2022). Traditionally, the Web of Science, Scopus and Google Scholar databases have been widely used databases (Singh et al., Citation2021). Other scholarly databases such as Microsoft Academic Search, and Dimensions could also be an alternative to Web of Science and Scopus databases (Thelwell, Citation2018), which are the leading scientific citation index platforms that contain literature, including journal articles, books, and conference proceedings, and were selected to extract the relevant articles (Zhu & Liu, Citation2020).

The available databases and citation indices contain a vast amount of literature with varying coverage of citation indices, depending on the scientific domain (Kumpulainen & Seppänen, Citation2022). To identify relevant articles, keywords were searched in titles and abstracts (Li et al., Citation2018), applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Kristjánsdóttir et al., Citation2017).

The search command was administered in Web of Science, as well as in Scopus with the following keywords (TS= (crisis* AND tourism AND sustainable tourism*) AND LANGUAGE: (English) AND DOCUMENT TYPES: (Article), including empirical research; peer-reviewed articles on the searched keywords published between 2001–2021. Before 2001, only a few studies on crisis management related to impacts on the tourism industry were conducted in the early years (Blake & Sinclair, Citation2003).

Strings of chosen keywords were searched in titles and abstracts and administered in April 2021, and subsequently in July 2021. Although both the Web of Science and Scopus databases covers a vast number of scientific domains, most of the articles that fulfilled the inclusion criterion of this paper were more visible in Web of Science, with 1,928 articles published between 2001–2021, while Scopus generated 201 articles published from to 2014–2021. The reason for the low number of articles on the research topic retrieved might be that Scopus was created as late as 2004 (Singh et al., Citation2021), and not as old as the Web of Science which is the oldest research publication and citation database created since 1964 was thus chosen (Birkle et al., Citation2019).

Selection process

Eligible articles retrieved from the Web of Science were 1,928, and from Scopus 201 articles, 2,129 were retrieved from databases. These were exported to an excel spreadsheet. The next step was to assess the articles by selecting those that were screened through the research titles and abstracts of empirical research articles and peer-reviewed papers published in English (Kristjánsdóttir et al., Citation2017). Duplicate and non-English articles were removed, and the remaining papers were identified at the title and abstract levels in accordance with the inclusion criteria. The excluded articles were checked against the inclusion criteria before removal. This process resulted in the inclusion of 115 eligible articles in this systematic literature review, which formed the basis for analysis. The inclusion and exclusion processes are shown in the PRIZMA chart (Moher et al., Citation2009) in .

Figure 2. Inclusion and exclusion process chart. Adopted from Moher et al. (Citation2009).

(The aim of the PRISMA Statement is to help authors improve the reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Moher et al., Citation2009). After removing duplicates and unmatched articles from the total number of hits, including the Web of Science and Scopus (n = 2139), 969 articles were accepted, and after the exclusion of the ineligible articles (n = 854), 115 articles were analyzed at the title and abstract levels based on the set inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Step five carried out the synthesis, comprising the extracted data to show what is known and provide the basis for establishing the unknown in line with McNulty et al. (Citation2013). This is followed by a presentation of the findings, discussions and conclusion, research implications for academia and industry, and areas for future research.

Results of the systematic literature review

The identified data guiding the analysis of the 115 reviewed articles are presented in : date of publication of the articles, research settings, authors’ institution and affiliated country, size of the research team, journals of publication, topics, research methods, theoretical aim of the articles, research settings, research methods, number of research methods, level of analysis, and conceptualization of the articles (McNulty et al., Citation2013).

Table 1. Criteria used to analyse research on previous crises faced by the tourism industry.

The findings are obtained from qualitative insights, synthesized from the articles, including graphic data illustrating details that would have been long textual information (Verdinelli & Scagnoli, Citation2013). The tables and figures were thus used to easily navigate the data descriptively. The analysis is followed by a discussion and conclusion, and finally the limitations of the paper.

illustrates the data that are useful for presenting the findings of the study from the perspective of crisis management in the tourism industry, including operationalization, research methodologies used, research teams and settings, topics, research aim, and levels of analysis of the research area under investigation, illustrating concepts, assumptions, expectations, beliefs, and theories applied around the topic (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994).

Date of publications 2001–2021

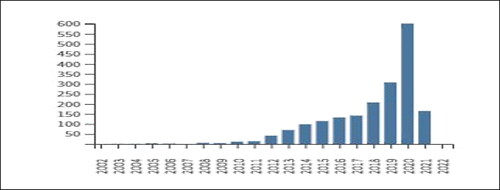

The articles found in the Web of Science Database published between 2001 and 2021 were more relevant for this study generating a total of 1,928 publications.

shows the number of articles retrieved from the Web of Science discussing crisis management in tourism published before the emergence of the COVID-19 crisis. Research interest in crisis management in tourism increased from 2005 to 2019, and gradually from the beginning of 2020. Such research is event-driven and is often conducted promptly following a particular crisis (Duan et al., Citation2021). An increase in research in this area from 2020 might have been encouraged by the COVID-19 pandemic. Before this period, the topic was barely covered in the literature (Wang, Kunasekaran, & Rasoolimanesh, Citation2021). To guide future research, this study explores research settings in which studies on these phenomena have been predominant.

Research setting and number of research settings

Forty-six articles (40%) were conducted in Europe, with Spain accounting for ten articles (9%), followed by 26 papers (23%) from Asia, and China leading with eight articles (7%). Australia follows with twenty-four articles (21%), and North America with 12 articles (10%). Only one study (0.8%) was conducted in Africa in the area. This finding seems to agree with Wut et al. (Citation2021), suggesting that, at the continental level, Asia is the most studied region followed by Europe, with no mention of Africa regarding crisis management in tourism. There is limited literature on crisis management in developing countries (Adam, Citation2015). Test of prospective crisis management models in the tourism industry in such countries is limited (Novelli et al., Citation2018). The inadequacy of research in this field agrees with that of Faulkner (Citation2001).

Country of the author’s institution

The authors’ affiliated institutions were coded to determine where the current body of knowledge on crisis management in tourism has been prominent (McNulty et al.,Citation2013). Findings show that research between institutions is more represented in Europe with 24 articles (21%), followed by Asia with 14 articles (12%), Australia with 10 articles (9%), North America with 7 articles (6%), and with Africa 1 article (0.1%). Research affiliation was higher among Australian institutions accounting for most of the articles from a single country’s perspective.

Size of research team

Collaboration and cooperation between researchers are increasingly common features of scholarly research (Zehrer & Benckendorff, Citation2013a) allowing the sharing of resources, such as research data sets (Fan et al., Citation2020). This can strengthen the competence base of the researchers and research communities. Forty-four articles (38%) were produced by three authors and above, followed by 39 articles (34%), then 32 articles (28%) from single authors. Most articles were produced by three or more authors, with research collaboration conducted within national boundaries and continental levels among European researchers.

Disciplines and number of disciplines

The field of crisis management in tourism can be characterized as multidisciplinary, with numerous disciplines contributing to its understanding over the past several decades (Weiler, Moyle & Moyle 2012). To determine where the current body of knowledge is contained, the study coded for research in Business Management, Tourism Development, Business Administration, Marketing, Geography, and Finance. Approximately 24% of the conversations are found within business management, followed by the tourism development field and business administration communities. The theoretical approaches in this field are illustrated in .

Table 2. Approaches.

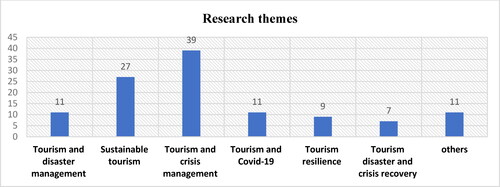

illustrates the theoretical approaches applied in the reviewed articles describing themes relating to the phenomena. Core components of the reviewed articles relates to Tourism disaster management, Sustainable tourism, Tourism and Crisis Management, Tourism and Covid-19, Tourism Resilience, Tourism disaster and crisis recovery, and others in addressing the field. Most of the papers are focused on Tourism crisis Management, followed by Sustainable Tourism. To facilitate an accurate synthesis of crisis management in tourism, topics, themes, scope, aims and objectives of the reviewed articles were explored.

Research topics

Previous research has focused on the effects of natural disasters or political turmoil on tourism destinations (Saha & Yap, Citation2014) and the operational handling of disruptions as they occur, mainly described as chaotic and unstructured (Öberg, Citation2020; Ritchie, Citation2004; Sönmez, Citation1998). The emergence of topics in the reviewed articles and the preferences of the authors are included in the discussion. illustrates the various research themes in the literature.

Each crisis is unique and affects tourism in various ways; therefore, it is difficult to search for a simple crisis management solution (Laws et al., Citation2007:2). Publications have been dedicated to resilience in tourism (Prayaq, Citation2018; Filimonau and De Coteau, Citation2020), and risks caused by natural and man-made disasters in tourist destinations (Ruan et al., Citation2017).

Around 33% of the reviewed papers are focused on crisis management in tourism, 24% on sustainable tourism, 11% on tourism disaster management, tourism, and Covid-19 crisis 10%) tourism resilience 9%), and tourism disaster and emergency recovery 6%). Other themes related to sustainable tourism are 7%. The literature provides individual strategic approaches to crisis management (Martens et al., Citation2016) including a focus on recovery (Ritchie & Jiang, Citation2019). As illustrated in regarding research approaches, shows that crisis management is the most discussed theme in the litetrature, followed by sustainable tourism.

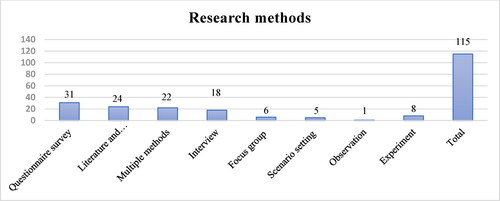

Research methods

This study coded the research approach and instruments used to collect data from the reviewed articles. Seventy (61%) of the articles were exploratory, while thirty-seven (32%) were conceptual papers, and the remaining eight (7%) are focused on elaborating or testing theories. This information contributes to determining the preferred research approach (i.e. quantitative vs. qualitative). illustrates the research methods used in the reviewed studies.

The questionnaire survey, thirty-one articles (27%), was the most frequently used type of data collection, followed by literature review and documentation used in 24 articles (21%), then the multiple methods used in 22 articles (19%), followed by the interview method used in 18 articles (16%). The rest of the articles applied focus groups in six articles (5%), scenario setting in five articles (4%), observations in one article (0.8%), and experiments in eight articles (7%).

Data collection instruments were coded. Among these, a total of 93 articles (81%) were based on a mono-method approach, whilst 22 articles (19%) used a multiple-method approach, including literature reviews, questionnaire surveys, interviews, focus group discussions, scenario settings, observations, and experimental methods.

Qualitative approaches are used more frequently than quantitative one. The use of mixed methods, including qualitative and quantitative methods, is popular in this research area. This study explored the unit of analysis used in the reviewed articles, which provided ideas regarding the object from which they collected data.

Level of analysis

Different levels of analysis constrain different levels, and researchers at each level need to develop theories that are consistent and require multiple levels of analysis (Cicchett and Dawson (Citation2002). Therefore, it was essential to explore the level of analysis of the articles reviewed in this study. Forty-six articles (40%) were based on a multi-level framework involving national and continental levels of analysis within Western countries. Furthermore, 60% of the articles were based on the individual levels of analysis, 38 articles (33%) on organizational level, followed by national levels of analysis in 13 articles (11,3%).

There were Ten articles (9%) based on group level, while eight articles (7%) were based on firm-level of analysis. Several studies have suggested useful crisis management practices for the industry, as well as strategies designed to mitigate the negative impacts of the crisis (Permatasari & Mahyuni, Citation2022). Although Asia is the most studied area of crisis management in tourism at the continental level, the extant literature addresses specific geographical locations as the unit of their analysis, with a focus on the country-level context. The analysis suggests that the current crisis management in tourism is more focused on management strategies of the tourism subsectors (Ruan et al., Citation2017; Prayaq, Citation2018; Filimonau & De Coteau, Citation2020) geared towards survival strategies for their businesses during challenging situations.

Need for conceptualization of crisis management in the tourism industry

Despite the presence of different approaches, it remains a difficult task for scholars to clearly articulate a common ground on crisis management that can be applied in the tourism industry, during crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. At the time of writing, there is no common crisis management model to describe cases of high uncertainty, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, where management techniques can be applied (Foss, Citation2020).

The pandemic served as a test for the established crisis mitigation approaches, demonstrating that the world was not fully ready to meet uncertainties and catastrophes of a magnitude commensurate to them (Tarbujaru & Stanca, Citation2022). Scholars have noted a lack of integration in crisis management research across disciplines and perspectives (Jaques, Citation2010), which might be due to the assumption that the field is poorly defined in various disciplines (sociology of catastrophe, public administration, political sciences and international relations, political and organizational psychology, and technical specialists such as computer scientists or epidemiologists) (Milašinović and Kešetović, 2008).

The literature is disjointed, lacks precision, and is a common approach that the tourism industry should follow during uncertain situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic. There is a need to organize and present these fragmented frameworks on the phenomena and suggest a framework that could guide future research with a common ground to rely upon to serve as critical elements in the steps towards crisis management for tourism during crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The models identified in the literature seem to encourage the involvement and participation of stakeholders in mitigating and managing crises that affect their operations (Johnson et al., Citation2006; Johnston, Citation2014; Mao et al., Citation2009; Waligo et al., Citation2013). This includes the state, emergency services, tourism organizations and representatives, experts/technical advisors, government officials, airport and port operators, utility operators (gas, electricity, and water), interest groups, and media (Ural, Citation2016).

At the at national level, current approaches in the tourism industry concern survival strategies of the tourism subsectors, with a focus on local and national situations. Crisis management theory appears to be the core component of the reviewed articles, focusing on the survival strategies of tourism subsectors at the national level dealing with situations affecting the tourism industry in Europe, Asia, the USA, and Australia. Concepts, assumptions, expectations, beliefs, and theories applied around the topic seem to be inadequate partly due to the levels of analysis often at national levels focusing on local issues, mostly in the context of countries in Africa underrepresented. Little research has tested prospective crisis management models for tourism in in the context of African countries (Novelli et al., Citation2018).

There are also limitations in research collaboration and cooperation between authors beyond the local, regional, and western country contexts. Governments from different countries have also adopted different policies and achieved different anti-epidemic effects (Zhou et al., Citation2022). A recent study including four countries, Sweden, China, France, and Japan compared to identify the critical institutional and cultural determinants of national response strategy, showing various responses regarding the same threat are dependent on the distinctive institutional arrangements and cultural orientation of each country, suggesting no one-size-fits all strategy (Yan et al., Citation2020).

A proposed framework of crisis management in tourism

Crisis management is a scientific management method adopted by tourism destinations to take preventive or elimination measures against risk factors that may arise in the process of tourism development and operation, and to take remedial measures after the occurrence of risks (Yang et al., Citation2021). From an academic point of view, it should be a multifaceted analysis including a historical, cultural, and anthropological one, to determine the course of evolution and consequences of the crisis (Zamoum & Gorpe, Citation2018).

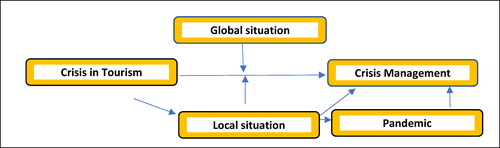

Everyone has their own resilience capabilities that need to be enforced and deployed in a crisis (ESRIF Final Report, 2009:112). Such instances appear to have been more acute during the COVID-19 pandemic. To mitigate the impact of such a crisis, there is a need to create a common ground on which researchers can rely to explore, test theories, and concepts needed for managing crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. illustrates relationships between the key findings of this study and maps how such variables are connected to each other.

‘Crisis management’ and ‘Crisis in tourism’ are central to this research along with their relationship to global and local crisis including pandemics situations as illustrated in . These themes provide a basis for generalizing patterns that shape conclusions to be applied to problem-solving, forecasting, planning, and management (Wacker, Citation1998).

Current strategies focus more on the survival strategies of tourism subsectors during crises that affect the tourism industry in Europe, Asia, the USA, and Australia. Increasing attention is being given to approaches that make room for local actors to collaborate with professional emergency services and contribute to the crisis management process (Boersma et al., Citation2022; Boersma & Wolbers, Citation2021). The tourism industry in most countries in most Africa countries often acts on the directives of tourist suppliers in industrialized countries, and this might also be the case during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings highlight limitations in research settings and, missing opportunities that could encourage multiple approaches and analyses beyond Western countries’ perspectives (Ritchie & Jiang, Citation2019).

Extending the research analysis on crisis management in tourism to include geographical settings such as the African context, could contribute to new knowledge in the field. It is an important way of thinking about some forms of contemporary social change (Bergman-Rosamond et al., Citation2022; Walby, Citation2015; Citation2022). In some critical situations managers used multiple and, to some extent, unique strategies for decision-making and crisis control (Shamshiri et al., Citation2022). The findings show that crisis management in the tourism industry is based on the survival strategies of tourism subsectors for survival during a crisis. Their understanding of the local situation and embeddedness in local networks are key assets in creating inclusive crisis responses (Boersma et al., Citation2022). This knowledge of the local tourism subsectors needs to be put upon to provide a common ground for a crisis management framework in tourism.

Various studies have shown that a wide variety of local stakeholders including community organizations, citizen networks, and spontaneous volunteers, provide aid during disasters and crises (Boersma et al., Citation2022; Ferguson et al., Citation2018). Considering the importance of the management strategies of the local tourism subsectors during crises, it is essential to integrate their strategies into mainstream crisis management in response to both local and global crises within a common framework upon which the industry can rely. This chosen criterion will capture the influence of the national cultural setting on research activities (Durst & Zieba Citation2020), and will encourage combination, integration, depth understanding and corroboration (Creswell, Citation2012). An inclusive approach linking crisis management strategies of local tourism subsectors to global levels using crisis management theories in the literature (prevention, preparation, response, and recovery) that expands the analysis to situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic is needed.

Discussions and conclusion

There is no representation that provides a clear idea of the pandemic situation, tourism sector, its economic activities, and the mitigation of losses (Bhuiyan et al., Citation2021). This study conducted a systematic review of previous research and presented the current body of knowledge on crisis management in tourism. It presents research gaps and directions for future research avenues that could be useful for tourism research on crisis management after post pandemic-era. Current methods cannot cope with such unexpected crises (Henderson, Citation2003) and are not prepared for such a pandemic, given their limited resemblance to previous crises (Bhaskara & Filimonau, Citation2021).

Little information is found in the literature about successful recovery strategies and prospects for businesses hit by the COVID-19 outbreak (Tarbujaru & Stanca, Citation2022). Key elements found to be useful in this analysis include exploring the research settings on the topic, authors’ institutions, affiliated countries, levels of analysis, theoretical frameworks used and findings in 115 articles published between 2001 and 2021 relevant to this study. The litetrature shows a narrow focus on the survival strategies of the tourism subsectors at the national levels, addressing local crises covering Europe, Asia, the USA, and Australia.

Research collaboration between authors in the field is confined within national boundaries and continental levels and mostly among Western researchers with limited representation of African scholars in such communities. The benefits of collaboration among researchers can provide opportunities for multidisciplinary research, development of new methods, knowledge sharing, and extension of their networks (Dusdal & Powell, Citation2021). This study suggests an expansion of research analysis in the field to include African countries. The endeavor could have a profound impact not only on Western nations regarding scientific ways to address the implications of crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, but also on developing countries with scarcity of resources for research, innovation, and development.

The findings highlight limitations in research settings, missing the opportunities of mixed methods that could encourage multiple approaches and analyses beyond Western countries’ perspectives (Ritchie & Jiang, Citation2019). Empirical research focusing on testing theories has been limited. The literature is fragmented, lacks precision, and is a common approach that the tourism industry should follow during uncertain situations, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The absence of a theoretical framework on crisis management that is inclusive of what tourism could rely on during such situations is a concern.

Therefore, this paper contributes to the literature by organizing and presenting the fragmented theoretical frameworks on the phenomena and suggests a framework that could guide future research with a common ground to rely upon to provide directions for research that could serve as critical elements in the steps towards crisis management for tourism during crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Research implications

This study is descriptive and provides insights into both the theoretical and practical implications. The gaps identified suggest possible future research avenues that will contribute to the scientific literature with new insights to expand discussions on crisis management in tourism. It provides a framework from the fragmented literature upon which future research can rely. This study reveals that current crisis management practices in tourism are based on management strategies of the tourism subsectors, which could be useful for practitioners to rely on during crises. The study could contribute to novel ideas that supports one of UNs’ identified tools to increase the economic benefits to Small Island developing States and least developed countries’ ‘by 2030, as comprised in Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) target. Furthermore, this suggests the need for future research to investigate the following:

What crisis management approaches have been adopted in the tourism industry in Africa; and precisely how have they handled the COVID-19 pandemic?

To Explore crisis management strategies of tourism subsectors in the Africa.

To explore the assumption that crisis management approaches in the tourism industry are based on the survival strategies of the tourism subsectors that the industry should adopt as a framework for crisis management.

Constructing a framework that the tourism industry can rely on to manage crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic is need.

Public interest.docx

Download MS Word (13 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The author confirms that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. The available data the study relied on are secondary data listed in the bibliography. No Restrictions are applied to the material used in this study.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Foday Yaya Drammeh

Foday Yaya Drammeh received his licentiate degree in Business Administration from Gothenburg, Sweden and currently a PhD researcher in Business Administration and Innovation Science at Halmstad University, Sweden. Foday has over 25 years of professional work experience in travel and tourism industry in Africa and Europe, with research interest in sustainable tourism in Least Developed Countries (LDCs), Small Tourism Business Enterprises and entrepreneurship, and Sustainable Innovation in relation to tourism.

References

- Adam, I. (2015). Backpackers’ risk perceptions and risk reduction strategies in Ghana. Tourism Management, 49, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.02.016

- Ahn, E., & Kang, H. (2018). Introduction to systematic review and meta-analysis. Korean Journal of Anesthesiology, 71(2), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.4097/kjae.2018.71.2.103

- Andersson, B. A. (2006). Crisis management in the Australian tourism industry: Preparedness, personnel and postscript. Tourism Management, 27(6), 1290–1297.

- António, N., & Rita, P, NOVA Information Management School (NOVA IMS), Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal. (2021). COVID 19: The catalyst for digital transformation in the Hospitality industry? Tourism & Management Studies, 17(2), 41–46. https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2021.170204

- Avraham, E. (2016). Destination marketing and image repair during tourism crises: The case of Egypt. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 28, 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2016.04.004

- Avraham, E., & Ketter, E. (2017). Destination Marketing during and following crisis: Combating negative images in Asia. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 34(6), 709–718. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2016.1237926

- Berdychevsky, L., & Gibson, H. J. (2015). Sex and risk in young women’s tourist experiences: Context, likelihood, and consequences. Tourism Management, 51, 78–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.04.009

- Bergman-Rosamond, A., Gammeltoft- Hansen, T., Hamza, M., Hearn, J., Ramasar, V., & Rydstrom, H. (2022). The case for Interdisciplinary Crisis Studies. Global Discourse, 12(3-4) , 465–486. https://doi.org/10.1332/204378920X15802967811683

- Bhaskara, G. I., & Filimonau, V. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic and organisational learning for disaster planning and management: A perspective of tourism businesses from a destination prone to consecutive disasters. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 46, 364–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.01.011

- Bhuiyan, M. A., Crovella, T., Paiano, A., & Alves, H. (2021). A review of research on tourism industry, economic crisis and mitigation process of the loss: analysis on pre, during and post pandemic situation. Sustainability, 13(18), 10314. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810314

- Birkle, C., Pendlebury, D. A., Schnell, J., & Adams, J. (2019). Web of Science as a data source for research on scientific and scholarly activity. Qualitative Science Studies, 1(1), 363–376. https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00018

- Blake, A., & Sinclair, M. T. (2003). Tourism crisis management–US response to September 11., V30 N4, 813–832. Annals of Tourism Research, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2013.06.002

- Boersma, K., & Wolbers, J. (2021). Foundations of Responsive Crisis Management: Institutional Design and Information. Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Politics. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1610

- Boersma, K., Berg, R., Rijbroek, J., Ardai, P., Azarhoosh, F., Forozesh, F., de Kort, S., van Scheepstal, A. J., Bos, J., et. al. (2022). Exploring the potential of local stakeholders’ involvement in crisis management. The living lab approach in a case study from Amsterdam. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 79, 103179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103179

- Booth, S. (1993). Crisis Management Strategy. Routledge.

- Broshi-Chen, O., & Mansfeld, Y. (2021). A wasted invitation to innovate? Creativity and Innovation in tourism crisis management: QC & IM approaches. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 46, 272–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.01.003

- Cahyanto, I., Wiblishauser, M., Pennington-Gray, L., & Schroeder, A. (2016). The dynamics of travel avoidance: The case of Ebola in the U.S. Tourism Management Perspectives, 20, 195–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2016.09.004

- Çakar, K. (2018). Critical success factors for tourist destination governance in times of crisis: a case study of Antalya, Turkey. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 35(6), 786–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2017.1421495

- Calgaro, E., Lloyd, K., & Dominey-Howes, D. (2014). From vulnerability to transformation: A framework for assessing the vulnerability and resilience of tourism destinations. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22(3), 341–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2013.826229

- Cassedy, K. (1991). Crisis management planning in the travel and tourism industry: A study of the three destinations and a crisis management planning manual. PATA.

- Chang, C.-L., McAleer, M., & Ramos, V. (2020). A charter for sustainable tourism after COVID-19. Sustainability, 12(9), 3671. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093671

- Chang, D. S., & Wu, W. D. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the tourism industry: applying TRIZ and DEMATEL to construct a decision-making model. Sustainability, 13(14), 7610. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147610

- Cheer, M. C., Lapointe, D., Mostafanezhad, M., & Jamal, T. (2021). Global tourism in crisis: conceptual frameworks for research and practice. Journal of Tourism Futures, 7(3), 278–294. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-09-2021-227

- Chen, J. M., & Chen, Y. Q. (2022). China can prepare to end its zero-COVID policy. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01794-3

- Cicchett, D., & Dawson, G. (2002). Editorial: Multiple levels of analysis. Development and Psychopathology, 14(3), 417–420. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579402003012

- Confente, I. (2015). Twenty-five years of word of mouth studies: A critical review of tourism research. International Journal of Tourism Research, 17N6 (6), 613–624. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2029

- Cook, D. J., Mulrow, C., & Haynes, R. B. (1997). Systematic reviews: Synthesis of best evidence for clinical decisions. Annals of Internal Medicine, 126(5), 376–380. 376-80 https://doi.org/10.7326/0003?4819?126?5?199703010?00006

- Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating Quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed.). Pearson.

- De Sausmarez, N. (2007). Crisis management, tourism and sustainability: The role of indicators. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 15(6), 700–714. https://doi.org/10.2167/jost653.0

- Dewey, A., & Drahota, A. (2016). Introduction to systematic reviews: online learning module Cochrane Training. http://training.cochrane.org/path/introduction-systematic-reviewspathway/

- Drabek, T. (1995). Disaster planning and response by tourist business executives. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 36(3), 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-8804(95)96941-9

- Duan, J., Xie, C., & Morrison, A. (2021). Tourism Crises and Impacts on Destinations: A Systematic Review of the Tourism and Hospitality Literature. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 46(4), 667–695. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348021994194

- Dumay, J. C., Bernardi, C., Guthrie, J., & Demartini, P. (2016). Integrated reporting: A structured literature review. Accounting Forum, 40(3), 166–185. N3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2016.06.001

- Durst, S., & Zieba, M. (2020). Knowledge risks inherent in business sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 251, 119670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119670

- Dusdal, J., & Powell, J. J. W. (2021). Benefits, motivations, and challenges of international collaborative research: A sociology of science case study. Science and Public Policy, 48(2), 235–245. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scab010

- Evans, S., & Elphick, S. (2005). Models of crisis management: An evaluation of their value for strategic planning in the international travel industry. International Journal of Tourism Research, 7(3), 135–150. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.527

- Fan, W., Li, G., & Law, R. (2020). Analyzing co-authoring communities of tourism research Collaboration. Tourism Management Perspective, V33, 100607.

- Faulkner, B. (2001). Towards a framework for tourism disaster management. Tourism Management, 22 (2), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00048-0

- Ferguson, J., Schmidt, A., & Boersma, K. (2018). Citizens in crisis and disaster management: Understanding barriers and opportunities for inclusion. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 26(3), 326–328. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12236

- Filimonau, V., & De Coteau, D. (2020). Tourism resilience in the context of integrated destination and disaster management (DM2). International Journal of Tourism Research, 22(2), 202–222. John Wiley and Sons Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2329

- Foss, N. (2020). Behavioral Strategy and the COVID-19 Disruption. Journal of Management, 46(8), 1322–1329. N8, https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206320945015

- Fotiadis, A., Polyzos, S., & Huan, T. C. (2021). The good, the bad and the ugly on COVID-19 tourism recovery. Annals of Tourism Research, 87, 103117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.103117

- Gani, A., & Singh, R. (2019). Managing disaster and crisis in tourism: A critique of research and a fresh research agenda. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 8(4)

- Goh, C., & Law, B. (2002). Modeling and forecasting tourism demand for arrivals with Stochastic nonstationary seasonality and intervention. Tourism Management, 23 (5), 499–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(02)00009-2

- Gough, D., Oliver, S., & Thomas, J. (2017). An Introduction to Systematic Reviews. SAGE Publishing.

- Gunter, Y. (2016). Returning to paradise: Investigating issues of tourism crisis and disaster recovery on the island of Bali. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, V28, pp11–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2016.04.007

- Guo, J., Zhang, C., Wu, Y., Li, H., & Liu, Y. (2018). Examining the determinants and outcomes of netizens’ participation behaviors on government social media profiles. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 70(4), 306–325. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-07-2017-0157

- Gössling, S., & Schweiggart, N. (2022). Two years of COVID-19 and tourism: what we learned, and what should be learned. The Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(4), 915–931. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2029872

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2020). Pandemics, tourism, and global change: a rapid assessment of COVID-19. The Journal of Sustainable Tourism., 29(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2020). Pandemics, tourism, and global change: a rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism., 29(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708

- Heath, R. (1998). Crisis Management for Managers and Executives. Financial Times, Pitman Publishing.

- Henderson, J. C. (2003). Communicating in a crisis: flight SQ 006. Tourism Management, 24 (3), 279–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(02)00070-5

- Henderson, J. C., & Ng, A. (2004). Responding to crisis: severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Hotels in Singapore. International Journal of Tourism Research, 6(6), 411–419. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.505

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2020). Socialising tourism for social and ecological justice after COVID-19. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 610–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1757748

- Hosie, P., & Smith, C. (2004). Preparing for crisis: Online security management education. Research and Practice in Human Resource Management, 12(2), 90–127.

- Huang, C., Wang, Y., Li, X., & Ren, L. (2020). Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5

- Hystad, P. W., & Keller, C. P. (2008). Towards a destination tourism disaster management Framework: Long-term lessons learned from a forest fire disaster. Tourism Management, 29(1), 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.02.017

- Israeli, A., & Reichel, A. (2003). Hospitality crisis management practices: The Israeli case. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 22(4), 353–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0278-4319(03)00070-7

- Jaques, T. (2010). Reshaping Crisis Management: The Challenge for Organizational Design. Organizational Development Journal, 28(1), 9–17.

- Jesson, J., Matheson, L., & Lacy, F. (2011). Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional AndSystematic Techniques. SAGE Publications.

- Jiang, Y., Ritchie, B., & Benckendorff, P. (2019). Bibliometric visualisation: an application in tourism crisis and disaster management research. Current Issues in Tourism, Taylor and Francis Journals, 22(16), 1925–1957. October. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1408574

- Johnson, G., Scholes, K., & Whittington, R. (2006). Exploring corporate strategy (7th ed.). Prentice hall, Financial Times.

- Johnston, A. (2014). Preventing the Next Financial Crisis? Regulating Bankers’ Pay in Europe. Journal of Law and Society, 41(1), 6–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6478.2014.00654.x

- Kaushal, V., & Srivastava, S. (2021). Hospitality and tourism industry amid COVID-19 pandemic: Perspectives on challenges and learnings from India. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 92, 102707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102707

- Kristjánsdóttir, K. R., Ólafsdóttir, R., & Ragnarsdóttir, K. V. (2017). Reviewing integrated sustainability indicators for tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(4), 583–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1364741

- Kumpulainen, M., & Seppänen, M. (2022). Combining Web of Science and Scopus datasets in citation-based literature study. Scientometrics, 127(10), 5613–5631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-022-04475-7

- Laws, E., Prideaux, B., & Chon, K. (2007). Crisis management in tourism: Challenges for managers and researchers. In Laws, E., Prideaux, B. and Chon, K. (Eds.), Crisis Management in Tourism. Wallingford.

- Leta, S. D., & Chan, I. C. C. (2021). Learn from the past and prepare for the future: A critical assessment of crisis management research in hospitality. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 95, 102915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102915

- Lew, A. (2014). Scale, change and resilience in community tourism planning. Tourism Geographies, 16(1), 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2013.864325

- Li, K., Rollins, J., & Yan, E. (2018). Web of Science use in published research and review papers 1997– 2017: A selective, dynamic, cross-domain, content-based analysis. Scientometrics, 115(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2622-5

- Liu-Lastres, B., Schroeder, A., & Pennington-Gray, L. (2018). Cruise line customers’ responses to risk and crisis communication Messages: An application of the risk perception attitude framework. Journal of Travel Research, 58(5), 849–865. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287518778148

- Maditinos, Z., & Vassiliadis, C. (2008). Crises and Disasters in Tourism Industry: Happen locally–Affect globally. Department of Business Administration University of Macedonia Thessaloniki.

- Mair, J., Ritchie, B. W., & Walters, G. (2016). Towards a research agenda for post-disaster and post-crisis recovery strategies for tourist destinations: a narrative review. Current Issues in Tourism., 19(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2014.932758

- Mao, C. K., Cherng, G., & Lee, H. Y. (2009). Post-SARS tourist arrival recovery patterns: An analysis based on catastrophe theory. Tourism Management, 31(6), 855–861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.09.003

- Martens, H., Feldesz, K., & Merten, P. (2016). Crisis management in tourism – a literature based approach on the proactive prediction of a crisis and the implementation of prevention measures. Athens Journal of Tourism, 3(2), 89–101. https://doi.org/10.30958/ajt.3-2-1

- McNulty, T., Zattoni, A., & Douglas, T. J. (2013). Developing Corporate governance research through qualitative methods: A review of previous studies. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 21(2), 183–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12016

- Meredith, J. (1993). Theory building through conceptual methods. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 13(5), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443579310028120

- Meyers, G. G. (1986). Wien if hits the fan: Managing the nine crises of business. Houghton Mifflin.

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). SAGE.

- Mills, M. C., & Rüttenauer, T. (2021). The effect of mandatory COVID-19 Certificates on vaccine Uptake: Synthetic-control modelling of six countries. The Lancet. Public Health, 7(1), e15–e22. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00273-5

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 339(jul21 1), b2700–b2535. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

- Nasir, A., Shaukat, K., Hameed, I. A., Luo, S., Mahboob, T., & Iqbal, F. (2020). A bibliometric analysis of Corona pandemic in social sciences: a review of influential aspects and conceptual structure. IEEE Access: practical Innovations, Open Solutions, 8, 133377–133402. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3008733

- Novelli, M., Burgess, L. G., Jones, A., & Ritchie, B. W. (2018). ‘No Ebola… still doomed’–The Ebola-induced tourism crisis. Annals of Tourism Research, 70, 76–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.03.006

- Orchiston, C. (2012). Tourism business preparedness, resilience and disaster planning in a region of high seismic risk: the case of the Southern Alps, New Zealand. Current Issues in Tourism, 16(5), 477–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2012.741115

- Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (2020). Rebuilding tourism for the future: COVID-19 policy responses and recovery. www.oecd.org/coronavirus/en/

- Ost, C., & Saleh, R. (2021). Cultural and creative sectors at a crossroad: from a mainstream process towards an active engagement. Built Heritage, 5(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/s43238-021-00032-y

- Paraskevas, A., & Altinay, L. (2013). Signal detection as the first line of defence in tourism crisis management. Tourism Management, 34, 158–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.04.007

- Permatasari, M. G., & Mahyuni, L. P. (2022). Crisis management practices during the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of a newly-opened hotel in Bali. Journal of General Management, 47(3), 180–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/03063070211063717

- Pottorff, S. M & Neal, D. M. (1994). Marketing Implications for Post-Disaster Tourism Destinations. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 3(1), 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v03n01_08

- Prayaq, G. (2018). Symbiotic relationship or not? Understanding resilience and crisis management in tourism. Tourism Management Perspectives, 25, 133–135.

- Ritchie, B. W. (2004). Chaos, crises, and disasters: a strategic approach to crisis management in the tourism industry. Tourism Management, 25(6), 669–683. pp. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2003.09.004

- Ritchie, B. W., & Jiang, Y. (2019). A review of research on tourism risk, crisis, and disaster§ management: Launching the annals of tourism research curated collection on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management. Annals of Tourism Research, 79, 102812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102812

- Roux-Dufort, C., & Vidaillet, B. (2003). Difficulties in Improving in a Crisis Situation: A Case Study. International Studies of Management & Organization, V33, 86–115.

- Ruan, W. Q., Li, Y. Q., & C. H. S. Liu. (2017). Measuring tourism risk impacts on destination image. Sustainability, 9 (9), 1501–1516. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091501

- Saha, S., & Yap, G. (2014). The moderation effects of political instability and terrorism on tourism development. Journal of Travel Research, 53(4), 509–521. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513496472

- Santana, G. (2004). Crisis management and tourism. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 15 (4), 299–321. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v15n04_05

- Schmitz, A., Urbano, D., Dandolini, G. A., de Souza, J. A., & Guerrero, M. (2017). Innovation and entrepreneurship in the academic setting: a systematic literature review. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 13(2), 369–395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-016-0401-z

- Seabra, C., & Bhatt, K. (2022). Tourism Sustainability and COVID-19 Pandemic: Is There a Positive Side? Sustainability, 14(14), 8723. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148723

- Seymour, M., & Moore, S. (2000). Effective crisis management: worldwide principles a Practice. Cassell.

- Shamshiri, M., Ajri-Khameslou, M., Dashti-Kalantar, R., & Och Molaei, B. (2022). Management Strategies During the COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis: The Experiences of Health Managers from Iran, Ardabil Province. Cambridge University Press. 04 March 2022

- Sheresheva, M. Y., & Oborin, M. (2022). Coronavirus and tourism: There is light at the end of the tunnel? Population and Economics, 6(4), 43–61. https://doi.org/10.3897/popecon.6.e90708

- Singh, V. K., Singh, P., Karmakar, M., Leta, J., & Mayr, P. (2021). Journal coverage of Web of Science, Scopus and Dimensions: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics, 126(6), 5113–5142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-03948-5

- Slater, T. R. (1984). Preservation, conservation, and planning in historic towns. The Geographical Journal, 150(3), 322–334. https://doi.org/10.2307/634327

- Smith, S. (1990). A Test of Plog’s allocentric/psychocentric model: Evidence from the seven nations. Journal of Travel Research, 28(4), 40–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759002800409

- Stern, E. K., & Sundelius, B. (2003). Crisis Management Europe: An Integrated Regional Research and Training Program. International Studies Perspectives, 3 (1), 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/1528-3577.00080

- Sönmez, S. F. (1998). Unk Tourism, terrorism, and political instability. Annals of Tourism Research, 25(2)pp., 416–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(97)00093-5

- Tarbujaru, T., & Stanca, P. I. (2022). Crisis management: What Covid-19 taught the world. Logos universality mentality education novelty. Logos Universality Mentality Education Novelty: Economics & Administrative Sciences, 7(1), 01–18. https://doi.org/10.18662/lumeneas/7.1/32

- Thelwell, J. P. (2018). Democratizing knowledge: A report on the scholarly publisher Elsevier, online. Education International. https://bit.ly/2PPjwRK

- Ural, M. (2016). Risk management for sustainable tourism. European Journal of Tourism, Hospitality and Recreation, V 7Issue(1) , 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1515/ejthr-2016-0007

- Verdinelli, S., & Scagnoli, N. I. (2013). Data display in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 12(1), 359–381. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691301200117

- Wacker, J. G. (1998). Definition of theory: Research guidelines for different theory-building research methods in operations management. Journal of Operations Management, 16(4), 361–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-6963(98)00019-9

- Walby, S. (2015). Crisis. Polity Press.

- Walby, S. (2022). Crisis and society: Developing a theory of crises in the context of COVID-19. Bristol University Press. https://doi.org/10.1332/204378921X16348228772103

- Waligo, V. M., Clarke, J., & Hawkins, R. (2013). Implementing sustainable tourism: A multi- stakeholder involvement management framework. Tourism Management, 36, 342–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.10.008

- Walters, G., & Mair, J. (2012). The effectiveness of post-disaster recovery marketing messages. The Case of the 2009 Australian Bushfires. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 29(1), 87–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2012.638565

- Wang, M., Kunasekaran, P., & Rasoolimanesh, S. M. (2021). What influences people willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine for international travel? Current Issues in Tourism, 25 1-(2), 192–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1929874

- Weick, K. E. (1993). The collapse of sensemaking in organizations: the mann gulch disaster. Administrative Science Quarterly, 38 (4), 628–652. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393339

- Weiler, B., Moyle, B., & McLennan, C-l. (2012). Disciplines That influence tourism doctoral research: The United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(3), 1425–1445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.02.009

- WHO. (2020). Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Situation Report – January 1- 21, 2020. 20200121-sitrep-1-2019-ncov.pdf (who.int)

- Wut, T. M., Xu, B. Z., & Wong, S. M. (2021). Crisis management research (1985-2020) in the hospitality and tourism industry: A review and research agenda. Tourism Management, 85, 104307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104307

- Wut, X Wong. (2021). Crisis management research (1985–2020) in the hospitality and tourism industry: A review and research agenda. Tourism Management, 85, 104307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104307

- Yan, B., Zhang, X., & Chen, B. (2020). Why do countries respond differently to COVID-19? A comparative study of Sweden, China, France, and Japan. The American Review of Public Administration, 50Issue(6-7) , 762–769. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074020942445

- Yang, J., Li, W., & Wei, H. (2021). Review of the Literature on Crisis Management Tourism [Paper presentation]. Proceedings of the 2021 2nd International Conference on Modern Education Management, Innovation and Entrepreneurship and Social Science (MEMIESS 2021). https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.210728.013

- Yang, S., Carlson, J. R., & Chen, S. (2020). How augmented reality affects advertising effectiveness: The mediating effects of curiosity and attention toward the ad. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 54, 102020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.102020

- Yang, Y., Zhang, C. X., & Rickly, J. M. (2021). A review of early COVID-19 research in tourism: Launching the Annals of Tourism Research’s Curated Collection on coronavirus and tourism1. Annals of Tourism Research, 91, 103313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103313

- Young, W. B., & Montgomery, R. J. (1998). Crisis management and its impact on destination marketing: A guide for convention and visitors bureaus. Journal of Convention & Exhibition Management, 1(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1300/J143v01n01_02

- Zamoum, K., & Gorpe, T. S. (2018). Crisis management: Historical and conceptual approach for a better understanding of today’s crises. In K. Holla, M. Titko, J. Ristvej (Eds.), Crisis Management Theory and Practice. Intech Open Limited.

- Zamoum, K., & Serra-Gorpe, T. (2017). Crisis Management: A Historical and Conceptual Approach for a Better Understanding of Today’s Crises. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.76198

- Zehrer, A., & Benckendorff, P. (2013a). Career and collaboration patterns in tourism research. Current Issues In Tourism, 19(14), 1386–1404. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2014.896320

- Zehrer, A., & Benckendorff, P. (2013b). Determinants and perceived outcomes of tourism research collaboration. Tourism Analysis, 18(4), 355–370. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354213X13736372325830

- Zhou, Y., Rahman, M. M., & Khanam, R. (2022). Impact of the government response on pandemic control in the long run—A dynamic empirical analysis based on COVID-19. PloS One, 17(5), e0267232. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0267232

- Zhu, J., & Liu, W. S. (2020). A tale of two databases: The use of Web of Science and Scopus in academic papers. Scientometrics, 123(1), 321–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03387-8

- Öberg, C. (2020). Disruptive and paradoxical roles in the sharing economies. International Journal of Innovation Management, 25(04), 2150045. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1363919621500456