Abstract

Police were utilised in British India to put down resistance to colonial rule. The role of the police varied from region to region. This article discusses the style of policing and police administration designed by the British administrators in the province of erstwhile Northwest Frontier Province (Presently Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province of Pakistan) and tribal areas adjacent to the province. Internal security was enforced by the police within the provinces, supplementing military efforts. Instead of using direct coercion, colonial authorities in the northwest frontier and border regions focused on integrating local populations into the system of regional security and coordinating their interests with those of the ruling class. The analysis in this article is based on the Indian archival records in the British Library London and other primary sources available in archives. This analysis demonstrates the importance of understanding colonial policing and police administration in the erstwhile Northwest Frontier province and tribal region near the border between British India and Afghanistan in particular leading to the postcolonial police administration in the northwestern frontier province of present-day Pakistan.

Police administration and crime control during British colonialism in India

Many scholars who study policing in colonial India tend to concentrate on the policing in various provinces that were directly administered by the British. They mostly have written about colonial policing strategies, the institutional development of the police, the connection between the police forces and more general governance issues, and the relationships between police and local communities (Arnold, Citation1986). But so far, none of the scholars focused and written specifically on police administration in the erstwhile Northwest Frontier Province, abbreviated as NWFP (present Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan) and the tribal areas bordering the British India border with Afghanistan (Fasihuddin, Citation2008; Petzschmann, Citation2010; Ras, Citation2010). However, the colonial administration in South Asia was not consistent in all the countries and within the different administrative units within the country (Naseemullah & Staniland, Citation2014). Within British colonies, colonial police strategies were also different from province to province due to the various locals and the unique social, cultural, and environmental settings. Richard Waller, for instance, in his analysis of policing under the British administration in Kenya, emphasized the need for colonial policing in several regions of heightened activity. As per Waller’s analysis, the policing landscape in Kenya encompassed a spectrum, stretching from ‘policed’ areas characterized by consistent and extensive police coverage to ‘unpoliced’ frontier regions where the presence of law enforcement was more limited, making it difficult to establish and even more challenging to uphold the rule of law (Waller, Citation2010). David Killingray (Citation1986) noted a comparable observation when discussing law and order in British colonial Africa, emphasizing that the understanding of ‘law and order’ varied among individuals and evolved over time.

As Harrison Akins argues, ‘surrounding local social context, geographical location, and various administrative systems also had an impact on how colonial policing operated to uphold British rule in South Asia and how they worked with the military.’ The British administration in India could directly govern provinces that had established administrative structures and were governed by British representatives employed through the Indian Civil Service. The strategically important tribal areas adjacent to Afghanistan’s border were far beyond the British authorities’ control directly but were subject to their claims due to several political and geographic constraints (Akins, Citation2022). To preserve peace and order in such areas, instead of employing a direct method of governance, the colonial government adopted an indirect system to govern them, adopting a strategy involving collaboration between British officials and local elites, sharing legal administrative, and political responsibilities with them. A British official argued that ‘methods used elsewhere may not always be a fitting model’ for controlling and ruling the tribals on the borderline due to differences between the frontier government and the provincial administration.Footnote1

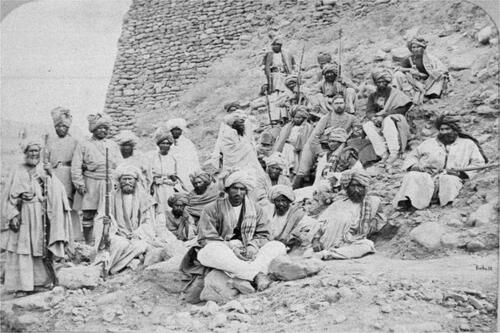

British authorities set up a unique administrative framework in the Indian Subcontinent. Harrison Akins wrote that diverse institutional structures form the basis for the deliberate efforts of British colonial officials to tailor governance approaches to match the prevailing economic, social, and political circumstances. These institutional configurations played pivotal roles in the British authorities’ distinct strategies for governance within each context, especially on the frontiers and in the British Indian provinces (Akins, Citation2022). In the words of David Arnold, who researched the colonial police in Madras, illustrates, ‘the police system in British India represented all aspects of colonial power.’ It is possible to observe how colonial administration’s aims and guiding concepts have been codified and put into practice through the police (Arnold, Citation1986). This paper examines the unique dynamics of colonial police administration in the erstwhile NWFP and the tribal areas adjacent to the province, a subject that, while crucial to understanding the colonial administrative legacy, has received limited attention in the existing literature. Hence by focusing on this region, the paper aims to fill a significant gap, offering new insights into the colonial police administrative system ().

Figure 1. W. H. Allen and Co. Pope, G. U. (1880), Text book of Indian history: Geographical notes, genealogical tables, examination questions, London: W. H. Allen & Co. Pp. vii, 574, 16 maps.Footnote2

The erstwhile Northwest Frontier Province (NWFP)

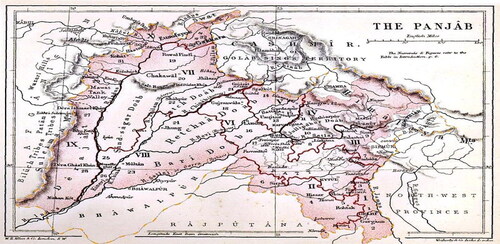

The province bordering Afghanistan in British India was identified as the Northwest Frontier Province and abbreviated as NWFP. This region is now a province of Pakistan and is called Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP). After the Durand Line was created in 1893, the border between the erstwhile North-West Frontier and Afghanistan became official. This boundary was named after Sir Mortimer Durand, who settled its course with the Emir of Afghanistan, with the Afghan Emir, passed through several tribal territories, and incited a great deal of animosity. Soon after, the Afghans rejected the pact (Pollard, Citation1909). As they had done before Sikh control, they continued to claim certain areas of the province as their own. They frequently meddled in tribal issues on the British side of the border in the years that followed to reclaim lost power there ().

Figure 2. A sentry of the Khyber Rifles stands guard on the frontier between British India and Afghanistan, 1946, National army museum number NAM number: 1973-10-40-6, Image number: 93781, (Photograph by Major A G Harfield, Khyber Rifles).Footnote3

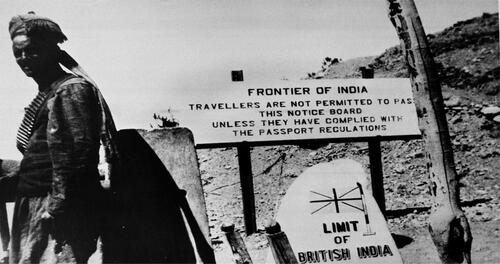

The region has a history of tribal conflict, militant activity, and political instability. The province has experienced significant changes in its political, social, and economic landscape since the partition of India in 1947. These changes have had a profound impact on policing culture in the region, and the effectiveness of police investigation techniques. Immediately following the Second Sikh War (1848–49), the NWFP became part of colonial India (Pollard, Citation1909) ().

Figure 3. Map of the present-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province (green), previously the North-West Frontier; and FATA (purple).Footnote6

Until it was separated from the province of Punjab into the erstwhile NWFP in 1901, this frontier region was a part of a part of Punjab. The larger ethnic group near the erstwhile NWFP was the Pashtuns.Footnote4 They were split up into numerous tribes, many of which were against one another. The intricate tribal system often led to internal rivalries and conflicts among different tribes or even within segments of the same tribe because of tribal blood feuds which continue from generations to generations, land disputes, personal grievances, political rivalries and competition for resources etc. Even the greatest tribes, such as the Waziris and Afridi, were divided into various clans. The tribes were all Muslims and upheld strict traditions of hospitality and honour. They typically supplemented their scanty existence by invading the richer populated areas to the east because their mountain homelands were harsh and desolate. The commerce caravans that travelled to and from Afghanistan were taxed by some tribes that held significant mountain routes, and if they refused to pay, they were robbed ( and ).Footnote5

Research questions

This study examines three significant and interconnected questions whilst India was ruled by the British, (a) What was the policing system and practices in India?, (b) What was the system of police administration in NWFP and tribal regions bordering the Indian-Afghanistan border? and (c) What was the logic of policing in NWFP and Tribal regions?

Methodology

The analysis demonstrates these differentiations in the colonial policing approach within the frontiers and the British Indian provinces. The analysis heavily depends on colonial documents found in the archives of the Indian Office Records at the British Library, London, including Home Department police reports on inside evaluations of security, and numerous policy papers from officials in the British Indian police. This article’s main goal is to understand the logic behind the policing and perceptions of British colonial officials regarding the differences in their methods of colonial policing. The above archival sources illuminate the inside structure of the different police forces in the erstwhile NWFP as well as the rationale and justifications for policing techniques. These sources generally ignore Indian perspectives on these topics, especially the usually oppressive nature of the police, and instead favor the viewpoints of colonial officials. This approach not only enriches the historical narrative but also contributes methodologically to the field by demonstrating the value of integrating diverse sources in colonial studies.

Administration of the NWFP police under the British

Before 1861, the region was ruled by the Sikhs under a system of binding landowners (Maliks and Jigirdars). The disputes were settled by the Panchayats and Jirga (councils of 5 local elders). Two Panchayats were established in each district, one to hear civil cases (limited to 12 years old), the other for police and miscellaneous cases (limited to 3 years old). The president of such Panchayat was to be the most honest and intelligent Indian officer available and the parties at issue were each to select one or two accessors. Appeals were to lie to the district officer.Footnote7

Following the Second Sikh War in 1848–1849 and the East India Company’s subsequent conquest of Punjab, the boundaries extended to the Afghanistan border hills. Hence, it was also necessary to create a police force within the Punjab military police battalions were raised and kept under central control by the Board of Administration and a civil police organization came into being in each district, under the order of the Deputy Commissioner (DC) in his capacity as District Magistrate.Footnote8

The civil police had to report crimes and track and arrest criminals with the help of professional trackers. They also served processes; collected supplies for troops and boats to cross rivers; guarded ferries; and escorted prisoners. Diaries and records were maintained. They were supplemented by village communities; and by city watchmen, paid from the watch and ward tax. There were 7 police battalions by 1850. The whole force was supervised by four British officers styled police captains, with divisional HQ at Lahore, Jhelum, Multan, and Derajat. Each battalion organization.Footnote9

One of the reflections of the existing system was that district officers had to act both as police and magistrateFootnote10, quite apart from their other duties like the collection of revenues. J. P. Grant, Bengal’s Lieutenant Governor, described their competing roles in a minute dated 9 April 1857.

‘If the Magistrate acts as Superintendent of Police, he will likely spend weeks buying spies, trying to influence allies, listening intently to everything they say, and using all of his wits to outwit his rival in the art of detection and will thus unfit himself for dispassionate adjudication on evidence which he has painfully prepared. On the other hand, if he acts only as a criminal judge, the Superintendent of Police then relinquishes all actual concern for the investigation of crimes and the prosecution of all offenders in the majority of cases and leaves this crucial and delicate task, in fact virtually entirely, to his subordinate’.Footnote11

This indicates the employment of the police for political ends is another flaw. When Charles Napier established the Sindh police, he purposefully isolated the police from the military and created a separate organization with its own officers to uphold law and order.

The frontier regions that were allied with Afghanistan were governed by the Punjab before 1901, as was the rest of British India. However, following extensive military operations to stop tribal boundary incursions, Viceroy Lord Curzon established the NWFP province in 1901 to draw attention to the region. There were ‘settled’ and ‘tribal’ regions in the province. An important fact is that a negligibly small British administrative and military machinery consistently and effectively administered this vast geographic area, encouraging the tribes to ‘control’ themselves using a combination of incentives and force. A. F. Pollard noted that the good governance of the people, most of whom have never seen a soldier and care not who their rulers are as long as they themselves are permitted to gather their crops in peace, is the responsibility of a small number of highly trained officials dispersed sparsely around the nation (Pollard, Citation1909).

In a letter to the Governor of the NWFP, Sir Ralph Griffth wrote,

The police force carries on with its ordained task of protecting the lines and properties of the country transducers. Scattered broadcast over the face of the country in lonely Thanas, under-paid, under-manned, overworked, with wonderful initiatives and tact it deals with a multiplicity of problems that would tax the resources of half a dozen departments in any country in Europe. In the Frontier province, the policeman’s lot is emphatically not happy. The normal duties of his calling are beset by obstacles arising from the virility of the Pashtun his cheap appraisement of the value of the human life, his close familiarity with sudden death, and his facile propensity to violence.Footnote12

He further illustrated that the police of the frontier province are frequently asked to carry out military- or semi-military-type tasks, such as the pursuit of raiders or the rounding up of desperate gangs of outlaws who fight with the frenzy of despair when they have nowhere else to turn. Each type of operation invariably exacts its toll on human life and inspires its share of devotional deeds. The Indian colonial police force was designed to keep the region’s law and order, with the primary goal of defending British interests. The British government’s rule consists of both a direct and indirect system of governance. The provincial police force in the British Indian provinces under direct rule by the British government maintained a definite separation from the local populace and served as a forcible authority responsible for upholding colonial order, frequently using repeated acts of violence. Differing from the provincial police, the local tribal police force, referred to as the Khassadari, in the northwest frontier, where the British administration employed an indirect rule approach via local tribal leaders, was not primarily designed as a coercive institution. Noticeably, Frontier policing had the dual goals of incorporating residents into community security structures and balancing tribe members’ interests and welfare with the continuous maintenance of colonial government authority.

The police system in the erstwhile NWFP was made on the colonial model, which was adopted in India in the middle of the 19th century. Colonial rulers established a professional police force for the sake of preserving security situations in the area. The police were responsible for keeping public order, discovering, and stopping crime, and guarding property. In the erstwhile NWFP, the Superintendent of Police (SP) oversaw the police department’s hierarchy. The SP oversaw policing, and he was supposed to report to the Inspector General of Police (IGP) in Punjab who was in charge of policing the entire province before the year 1901 when the erstwhile NWFP was a part of the Punjab province. Each of the districts that make up the erstwhile NWFP is controlled the by Deputy Superintendent of Police (DSP). The DSP was in charge of preserving peace and order in his district and reported to the SP.Footnote13 Only a few Sikhs and Europeans made up most of the police force, which was primarily made up of Muslims and Hindus. The ethnic composition of the force had a big impact on how the police interacted with the predominantly Pashtun locals. The police oversaw conducting criminal investigations and making arrests in erstwhile NWFP. The investigation process adhered to the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC), which India approved in 1861. The code laid out guidelines for conducting investigations and admitting evidence in court. Police have regularly been accused of using excessive force and torturing suspects while conducting investigations. This was a result of the police force’s lack of equipment and instruction. Police were also accused of discriminating against the British and non-Pashtun population.Footnote14

The policing system in the Indian provinces during the colonial period

The police were developed in India as a system ‘designed to support the British rule’ (Arnold, Citation1986). Its role was to serve as ‘the eyes and ears’ of the colonial ruler, gathering and relaying intelligence to the government while simultaneously functioning as a repressive force that might take the place of troops in the suppression of small uprisings. Sir Charles Napier, the head of the British Army in India, took control of Sind to the Presidency of Bombay in 1843 (Sheptycki, Citation1995). Napier established an Irish-style police system in the 1840s in the province of Sind (now the southeastern province of Pakistan). Later, other provinces adopted a like system, and police were set up and armed on a military basis. By emulating the Irish model’s organisational structure, the police became a tool for social control. Napier doesn’t utilise civil workers to administer his new government because they are more expansive and less active than before. Napier decided to use military officials, or ‘Civilian soldiers’, because they were ‘far less expensive and extra active’, to manage his new administration. Napier used the Irish constabulary’s military structure to keep command of the entire force in the hands of a captain of police. However, this method didn’t work since it was far ahead of its time. Everywhere in the nation, the number of crimes, robberies, and killings surged (Burke & Quraishi, Citation1995).

Under the leadership of Mr. M.H. Court, the first police commission was tasked with reviewing the policing arrangements in place in India after the War of Independence in 1857. The commission suggested that a civil police force be established across the Indian subcontinent, organised on a provincial basis, and following the British Constabulary’s organisational model. One of the recommendations made by the commission was to abolish the police commissioner’s authority. Instead, it was suggested that an Inspector General of Police be selected for each province, who would be responsible for overseeing the local police forces and answerable to the provincial government. Their responsibilities should include keeping the peace, preventing, and catching criminals, as well as watching over captives and valuables. The history of the Indo-Pak police starts right here (Singh, Citation1989).

According to the historical background that John Christie collected from old reports and records before trying to set out some details of his grandfather’s career, he wrote that;

The Superintendent of Police (SPs) were all military officers, most of them from native infantry regiments. The bulk of the SPs were civilians, known as un-covenanted officer. They had nearly all previous services in government departments. By the end of April 1861, Punjab police officers were serving in the 27 cis-Indus districts, having taken over the charge of police from the District Magistrates. There were 66 superior police officers, One IG, four DIGs, 27 SPs, and 34 ASPs. The total strength of the Punjab police at the end of 1861 was 13,026. In addition to the superior police officers, there were 63 inspectors, 463 Deputy Inspectors, 1571 Sergeants, and 9102 constables of foot police as well as 278 Sergeants and 1483 Sowars who were mounted. The military police battalions were disbanded in July 1861 except for this on the frontiers. The best men were absorbed into the new police, the rest were discharged with gratuities. The old rank of Subedars, Risaldars, and Jamadars now became the new ranks of Inspectors and Deputy Inspectors.Footnote15

After the revolt of 1857 and the establishment of British Crown power, the British administration sought to establish a centrally coordinated police force to assist civil organizations. This effort was made in various cases to displace and replace distinctive local policing systems to reinforce British political control in India (Piliavsky, Citation2013). A unified police force was established in the British Indian provinces as a result of the Indian Police Act of 1861. The Indian Civil Service (ICS) district magistrates who oversaw provincial police units during the middle of the 1930s claimed that their primary focus was on ‘quelling’ criminal activity to keep peace and order. However, in Delhi during that period, the police often demonstrated a higher level of efficacy in containing minor offenses such as burglary as compared to their performance in handling more grave crimes such as murder, terrorism, and kidnapping.Footnote16

The main reason India’s civil police force was created was to relieve the military of the responsibility of maintaining domestic public order. Consequently, the police were present for political objectives. Beyond tackling criminal activity and preserving the safety and property of the Indian community, its objective was to safeguard the state and uphold colonial rule. As stated by Peter Robb, ‘instead of functioning primarily as a means to identify and eliminate criminal activities, the imperial police functioned for a considerable time as a predominantly symbolic emblem of authority and order, collaborating with other similar instruments in its role’ (Robb, Citation1991). Early in the 20th century, as political agitation within the Indian nationalist movement grew more intense. The chief secretary of the Bengal government observed that the police forces often had to shoulder the responsibility of handling ‘this charged political environment.’Footnote17 According to British government representatives, a rise in petty crime was caused by the reason of police concentration on political work and ignoring their main duty of crime control.Footnote18 As the police turned more and more of their attention to the political task of putting down resistance to colonial authority in the early 20th century, they also turned more and more to violence.

Colonial policing and police investigation in erstwhile NWFP and FATA

The colonial period in the Indian subcontinent was characterized by the imposition of British rule and the establishment of various institutions to retain security in the state. One of these institutions was the colonial police administration, which was established to maintain security in the erstwhile NWFP province and the FATAFootnote19 (Coatman, Citation1931). In 1932, Major-General S. F. Muspratt pointed out that the NWFP and its adjacent tribal route of Khyber Pass within the Afridi Territory lie in an important strategic location (Skeen, Citation1932). He further pointed out that in addition to the Scouts and Militia, the erstwhile NWFP also has postings for the Corps of Frontier Constabulary, whose main responsibility is to deter raiding. The Khassadars are another civil force that is located over the border and is made up entirely of indigenous tribe members. Their primary responsibility is road protection, and because of this, they could be considered a primitive kind of police that is subject to political control through their maliks. They supply their weapons. The NWFP and FATA were regions of British India that were known for their tribal culture and frequent rebellions against British rule. The reason for this is that tribal Pakhtuns areas remain independent even before the arrival of the British and they did not accept any foreign rule. Hence, the British authorities established a colonial policing system in the region to maintain law and order and to quell any resistance to British rule.

Structure

The colonial police administration in erstwhile NWFP and FATA was headed by a British officer known as the IG of police. The police force consisted of both British and Indian personnel, with British officers occupying the higher ranks. The police force was set up according to the district, with an SP of police in charge of each district’s police force. Responsibilities of the District police included tracking down criminals and conducting investigations of crimes to preserve law and order within its purview. The erstwhile NWFP and FATA also had a paramilitary force known as the Frontier Constabulary (FC) in addition to the district police force. About the history of Frontier Constabulary, Muzzafar Khan Bangash, P.S.P. wrote that;

In 1879, a force called the Boarder Military Police came into existence but only for that part of the border which runs along the Swat River Southwards right up to Kohat Pass ending in the Jowaki hill. Another force called the SAMAN RIFLES was similarly raised in 1879 to guard the Samana Rudge between the Kohat District and Orakzai country (Gordon, Citation1968).

Both the Boarder military police and Samana Rifles were a type of Levy and as their work was nothing but satisfactory, they were replaced by the frontier constabulary on 1st April 1913, when both the forces were amalgamated. In 1922, another temporary war corps of the Mohmand Militia in the Shabkadar area was also incorporated with the constabulary. They are drawn from all the trans and cis border tribes of Pakistan’s North-West Frontier. Their life was hard indeed, more often than not, the drinking water supply is from the periods where rainwater collects and is two to four miles away from their posts water is therefore fetched by means of mules.Footnote20

It might be concluded by saying that the colonial police force in the NWFP and adjacent tribal areas made a substantial contribution to the maintenance of colonial rule in the region. But the subject of its legacy is still up for discussion and argument. Relations between the police and the community deteriorated because of officers using excessive force and disrespecting regional traditions and culture. The policing system had a considerable impact on the region’s political and social institutions as well, helping the ruling class solidify its hold while repressing popular movements for social and political change.

Colonial police investigation in erstwhile NWFP

The British common law system served as the foundation for the police investigative system in the NWFP throughout the colonial era. The police had the power to investigate crimes, gather information, and detain people. In addition, they were in charge of maintaining peace and order and preventing crime (Pollard, Citation1909). Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Ralph Griffith (Citation1938), claimed that to accomplish these objectives, a significant corps of Khassadars, or tribal police, were organized, and the security of the routes was handed to them with the assistance of the Scouts.

The two sections of the NWFP police force were the civil police and the military police. The civil police were responsible for maintaining law and order in the settled districts of the NWFP, where the authority of the British and local administration was more firmly established. Their duties were similar to those of police forces in other parts of British India. The military police, on the other hand, were responsible for maintaining law and order in the tribal areas and along the borders with Afghanistan. The police investigation process has several stages. The procedure began with the filling of a complaint. Anyone could visit the police station and file a report if they had been the victim of a crime. The policeman would document the grievance and start an inquiry. The gathering of evidence was the following step. The policeman would go to the crime scene, collect tangible evidence, and speak with witnesses. The police officer would then examine the evidence and attempt to identify the suspect (Griffith, Citation1938).

A police officer would apprehend a suspect after identifying them and take them to the police station. After questioning the suspect, their remarks would be recorded. Additionally, the policeman would work to compile more proof against the suspect. The suspect would be charged with the crime and the case would be made before the court if the police officer felt they had sufficient proof.

Frontier crimes regulations and the northwestern frontier regions

The colonial administrators adopted the policy of limited interference in the tribal regions of the frontiers. In a telegraph from Secretary of State to Viceroy, 13th October 1897, printed on page 26 of C. 8714 of 1898, it stated by the Secretary of the State to Viceroy that ‘to restrict and limit the interference of independent tribes and to avoid any serious involvement in the extension of administrative control over tribal territory’.Footnote21

Alastair MacKeith in his memoir writes that;

The geopolitical situations and culture of the tribal areas on the Afghanistan border sides were different. Each tribe was headed by a tribal head called Malik. Their position and status in their tribe are of great significance. The Malik had authority over their tribes and people used to accept their views and words. Most of the time Malik acts like a Judge as well and their decisions in most of the conflictual issues are final. Maliks are also the heads of the Jirgas as well where disputes of local nature are discussed and resolved. The colonial administrators understand the importance of their position and to control the Maliks means to control the whole tribe and similarly, opposition of Maliks may lead to opposition of the whole tribe. Political Agents (PA) used to be the head of each tribal region/agency. PA is like the District Commissioner, and he was recruited through a competitive examination. Once in a week or month, there was a gathering of all the tribal chiefs/Maliks under the headship of the Political Agent. Tribal Maliks also used to receive a sum of money on a month or annual basis from the PA as well.Footnote22

The British colonial authorities in India sought a practical solution to the north-western region’s crime problem in the middle of the nineteenth century. They decided to create a parallel legal system by seeking to incorporate the traditions of the Pashtun tribes into the legislation since they believed the current legal system was incapable of handling the situation. Clauses from the 1887 Punjab Frontier Crimes Regulation served as the foundation for the 1901 Frontier Crimes Regulation which was promulgated in tribal regions while in the settled areas of NWFP, the legal framework was in line with the rest of British India, Including, Indian Penal Code (IPC), Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), and Civil Procedure Code (CPC).Footnote23

The Tribal Areas of the Northwest Frontier were located on the British side of the Durand Line, and this borderline was established in 1893 to demarcate the border between British India and Afghanistan. In British India, these locations were considered outlying areas outside the purview of municipal law. With increasing British apprehension regarding Pashtun tribes’ incursions into populated areas and their resistance to outsiders on their land, the British government grappled with the task of establishing and maintaining British authority in this border region, despite the limited government presence (Akins, Citation2022).

The British North-West Frontier policy goes through several phases. Following the annexation of Punjab, the government pursued a strategy that became known as the ‘close border’ policy for more than a quarter of a century. The major component of the strategy was to closely monitor the border to minimise attacks and the ensuing military expeditionary retaliation. The policy’s stated goals were non-interference against tribal land and non-aggression in tribal matters. A military organisation known as the Punjab Frontier organisation was established for defense purposes under the absolute command of the Punjabi government, and it was merged with the regular army in 1886. Along the administrative border, new forts were built, and a military road connected some of them, while the old forts were rebuilt. Tribes were required to keep good and peaceful relations with the colonial rulers in exchange for allowances and subsidies under agreements established with them.Footnote24 However, in the late 1990s, during the administrations of Lansdowne (1888–1894) and Elgin (1894–1999), the Indian government implemented new defense procedures by enacting the ‘Forward Policy.’ This proactive approach was used in tribal territory. This policy was implemented out of concern for Russian territorial expansion in Central Asia and her move closer to Afghanistan’s boundaries. To maintain control over the tribal belt, different positions were held, and new militia and levies troops were organised. Kurram, Waziristan, Gilgit, and Malakand agencies were founded in the 1990s final decade.

British Indian military leaders emphasised the value of pursuing ‘a proactive strategy regarding the independent tribes residing in the NWFP’ in the late 19th century. To mobilise our forces and set up their organisation to support offensive action against foreign opponents, they pushed for efforts to get access to their area.Footnote25 The British Indian government issued an order in 1898 stating that to diminish the influence of the army’s existence on the borderline, no additional duty should be taken on the frontier unless it was made essential by actual strategic necessities.Footnote26

In 1901, the British Indian government implemented Frontier Crimes Regulations (FCR) and this replaced the previous system. This was done as part of a political strategy to repress any threats to its dominance in the Tribal Areas. The concept of indirect rule served as the foundation for the executive authority of FCR, whereby the British government formalised the roles of local elites by giving them sway over administrative, judicial, and political issues (Naseemullah & Staniland, Citation2014). The British Indian government’s acknowledgement of the power granted to tribal elders, known as maliks, served as the foundation for the FCR’s administrative framework. The administration and the larger tribe were unified through the government-recognized maliks, who rendered decisions per the Pashtunwali, the tribe’s code of honour, customs, and religious law. The law was said to deny local Tribal Areas citizens the ability to represent themselves in court, the right to provide evidence to support their claims, and the right to challenge a judgment. In the jirga, the maliks were given the power to make decisions on law and order and the general welfare of the tribe without any recourse from other tribal members (Akins, Citation2018).

Hiring individuals from the frontier’s local communities to work in the FCR’s governance institutions and the back of colonial authority was a crucial component of this frontier policy (Tripodi, Citation2014). According to Lord Curzon, the purpose of this framework is to ‘As far as possible, use the tribes themselves to safeguard our military interests and foster local unity’ and ‘recruit the wild but not hostile residents of these areas to the British Government, but in defense of their own country, will foster a spirit of local concord and cooperation.’Footnote27 To link the local communities and their concerns with colonial systems of governance and supervision, British authorities enlisted local Pashtuns in various roles within this administrative framework. This was done to increase political influences and diffusion into the boundary and, eventually, appease the tribes. Due to the vastness of the Punjab province, NWFP was made a commissioner province in 1901.

Recruitment in the tribal police force

Colonial administrators adopted a complex process of recruitment influenced by multiple factors including tribal traditions, local customs, administrative needs, and most importantly their approach to controlling the tribal areas. The colonial authorities recognized the significance of enlisting the local tribal communities for the tribal police force known as ‘khassadari’ under the FCR. This system was different from the police system of the provinces in British India. The police helped the colonial administrators to establish a degree of trust between the police force and residents. Tribal leaders and elders often played a role in the recruitment process. Under the system, tribal elders can recommend individuals from their communities who are seen as trustworthy and capable of maintaining law and order as well as respecting tribal norms and values. Khassadars were operated by British police officers (Akins, Citation2022). The tribal police force’s recruitment criteria were frequently tailored to the distinctive peculiarities of tribal societies. Tracking, terrain navigation, and understanding of local languages were required alongside more traditional policing skills. Individuals chosen for the tribal police force received training to equip them with the required abilities of law enforcement. Training programs were developed in response to the unique challenges and needs of tribal territories. The tribal police uniforms and equipment were occasionally modified to be more culturally sensitive and practical for the local context (Ahmed, Citation1980). The goal of this strategy was to make the police presence less alien and threatening to the tribal populace. Tribal police officers who demonstrated devotion, bravery, and effectiveness in upholding law and order were sometimes rewarded, recognized, and promoted by the British authorities.

A famous Pakistani anthropologist who also remain as a political agent in the tribal area of erstwhile NWFP province, highlighted the significance of a Malik, nothing that a Malik’s reputation is assessed by the amount of Khassadars he can secure from the government. This enhanced his status and position in his tribe and raised the amount of government cash that were dispersed through his hands among his tribal community. Beyond policing, the Khassadari system also aided in local tax collection and the provision of justice in conformity with the tribal customs and traditions. It was a distinctive feature of the system that law enforcement and local government administration performed and dua function (Ahmed, Citation1980).

According to historian Benjamin Hopkins (Citation2020), the tribals of these localities found their violent actions transformed into paid labor within a ‘military labour market’ that had strong connections to the policing of the frontier population. To further promote reliance on British power structures in the Subcontinent and assert British political control within the periphery, the khassadari system served as a means of integrating local tribesmen into the security forces and commodifying their labour. However, because the British administration valued control of the area, the tribal territories continued to be economically and politically reliant on British India despite the residents being classified as ‘independent.’

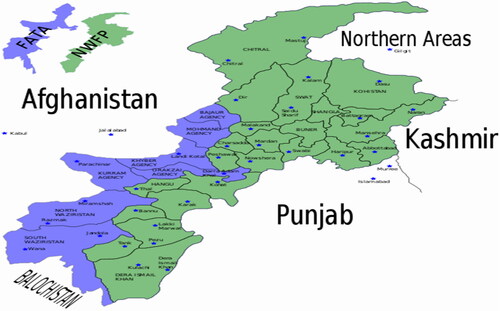

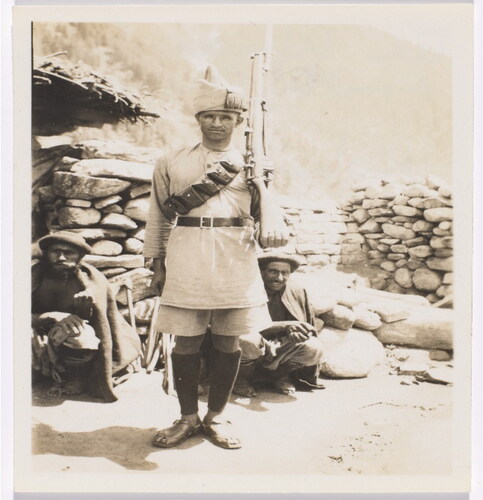

According to a former British military officer in India, the khassadars were known as ‘insurance men’ (Ingall, Citation1988). Another former military officer of British India, although they were given orders by the administration to defend a section of a pass, road, or an officer, the khassadars were acting on behalf of the tribes rather than the government. They were accountable to the tribe and for the tribe; even though they were innocent as individuals, the government might fire the khassadars if the tribe misbehaved. As a means of political pressure to end tribal unrest, the colonial authorities would withhold payment from the khassadari. This not only affected the members’ standing and income but also prevented the inflow of cash into the tribe (Woodruff, Citation1954). This seems to be a sanction against the whole tribe and thus the entire tribe must ensure good behavior to the British authority and hence maintain stability and good character ().

Figure 6. An Afridi sentry of the frontier constabulary with kohistani prisoners, 1934, NATIONAL army museum number: 136247, image number: 136247 (Photograph by Lieutenant L H Landon, Royal Artillery, India, North West Frontier, 1934.).Footnote28

Military and the tribal police force

During the British rule in India, there were distinct law enforcement and military forces, each serving different purposes and operating under separate chains of command. In certain regions of British India, especially in the erstwhile province of NWFP, there were tribal areas where the British established tribal police forces. These areas were inhabited by various tribal groups, and maintaining law and order there was challenging due to their unique social and cultural structures. Three different kinds of militias were used by the regional frontier authority. First, the government established the Frontier Corps, which was made up of paramilitary organizations commanded by British officers and the PA and recruited from local tribesmen. These militias acted as guarantors of justice by administering collective punishment, deterring attacks, watching over prisoners, and escorting convoys in the late 1890s. They also started to take the place of military personnel in providing physical protection for the roadways and important foothill passes. Initially, these groups included the Zhob Militia, Chitral Scouts, the South Waziristan Scouts, the Tochi Scouts, the Khyber Rifles, the Kurram Militia, and the Chagai Militia. They served as the PA’s ‘stick’ and increased the legitimacy of the use of power within the Tribal Areas by enlisting the assistance of local tribesmen. Colonel H.R.C. Pettigrew of South Waziristan claimed that this was the main explanation for their survival.Footnote29 Their use came with some dangers. Desertion, assaults on British personnel, the escalation of tribal mutinies, or blood feuds were perennial concerns for British commanders.Footnote30 Because of this, tribal jirgas provided guarantees for tribesmen serving in the militia.Footnote31 The government would take punitive action by temporarily banning the militia’s enlistment of difficult clans, as the Mehsud of South Waziristan in February 1905. They even disbanded the militias under extreme conditions. For example, to maintain the Khyber Pass after the Third Afghan War in 1919, due to widespread defections, the Khyber Rifles were abandoned by the government in favour of regular military units. The Frontier Corps (FC) was expanded and integrated under the Interior Ministry following Pakistan’s independence in 1947. The British established tribal police forces known as ‘Levies’ in these regions.Footnote32 These Levies were comprised of local tribal members who were responsible for maintaining order within their respective tribal territories. The primary role of these tribal forces was to assist in maintaining peace, controlling local disputes, and enforcing the British government’s authority in these remote and often unruly regions. They were not regular military units but rather a form of paramilitary force.

The British Indian authorities were aware that the local tribal forces such as Khasadars could not act in place of the military in the use of force and that occasionally, tribal disruption went beyond the local forces’ limited capabilities. In these situations, the military was used to quiet the area and put an end to the widespread disturbance on the frontier (Burke & Quraishi, Citation1995).

Important to keep in mind is that tribal police forces were separate from conventional military organisations like the British Indian Army. While both served the British colonial administration, their roles, structures, and deployment areas were different. The tribal police forces were primarily responsible for maintaining order in tribal areas, while the British Indian Army had a broader role in maintaining British rule and defending the interests of the British in India and beyond.

The fundamental approach of the British Indian government for the khassadari was based on its local character and the khassadars’ representation of the local tribe, which was very different from the provincial police’s description. The khassadari, a frontier police force, served as a way of maintaining British authority no less than their counterparts in the provinces, even though British authorities were aware of their many shortcomings and their incapacity to function as a coercive force like the provincial police (Akins, Citation2020). However, the Khassadari mainly succeeded by including local tribesmen in the Tribal Areas’ security system and by linking the needs of the populace to the maintenance of British political dominance.

Conclusion

Numerous important observations were uncovered through a thorough review of historical sources, official records, and scholarly accounts. The paper not only fills a critical gap in the existing literature on colonial policing in British India but also underscores the importance of regional studies in understanding the complexities of colonial administration. The research underscores the importance of understanding the historical context of policing with various complexities in the colonial Northwest Frontier Province and Tribal Area near the British Indian-Afghanistan Borderline (Present day Pakistan-Afghanistan Borderland). The British strategy for colonial law enforcement on the northwest frontier was comparable to that used in other colonial tribal areas and the borderline of the colonial Empire. Due to the perceived instability of the tribal areas, the British Colonial authorities implemented a militaristic police strategy in this area. This militarization has long-lasting implications on the relationship between the state and the native people, as well as on the composition and operation of the police. The goal of policing in this area was not just to keep the peace; rather, it was intricately linked to bigger strategic objectives, such as protecting British interests in Afghanistan and keeping control over the tribal communities. The form of administration and policing was profoundly affected by this strategic perspective. In the British Indian provinces, colonial authorities wanted the police to be independent of the local population and to uphold British rule among the Indian populace, even if that meant using force to maintain internal security. Tribal groups were significantly impacted by colonial policing and administration practices, which resulted in the demise of the indigenous governance framework and the establishment of colonial legal and governmental frameworks. This also led to the establishment of resistance movements and persistent conflicts in the area.

The erstwhile Northwest Frontier Province and adjacent tribal area’s current security environment is still impacted by the historical legacy of colonial police, which has ramifications for modern Pakistan’s efforts to address securities issues and promote peace with tribal groups. To manage the difficulties of modern-day provincial policing and work toward a more peaceful and just future in this historically significant area, it is important to acknowledge the past and learn from it.

Ethical approval

The research underlying the manuscript complies with the ethical standards of scientific research and meets the requirements of the ethics committee of the institution where it was produced.

Acknowledgments

I am thankful to Dr. Zoha Waseem, Assistant Professor of Criminology, University of Warwick, who supervised and guided me during my Postdoctoral research work.

Disclosure statement

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data availability statement

The data used in this research is collected from the archives at the British Library London. The details information about each archive used in the paper is already shared.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 ‘Proposal for deposition of Mir of Hunza on grounds of Kashmir misrule in favour of his and capable heir Mirzada Jamal Khan’, 1945, 8.

2 Figure 1, Image Courtesy of the National Army Museum, London.

3 Figure 2, Pahari Sahib, Pakistan KPK FATA areas with localisation map, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Pakistan_NWFP_FATA_areas_with_localisation_map.svg&redirect=no, 2010.

4 Pashtuns, also known as Pakhtuns, or Pathans, are currently the second largest ethnic group of Pakistan. They are living on both sides of the Pakistan-Afghanistan border.

5 North-West Frontier Province and Constabulary: Sir Ralph Griffith: ‘The North-West Frontier Police’ (nd) Dated as pre-1926.

6 Figure 3, ‘W and A K Johnston’s War Map of the North West Indian Frontier’, 1897.

7 Typescript, ‘The Punjab Police before 1861’ by William Harold Adrian Rich (1908-89), Indian Police, Punjab and the North-West Frontier Province 1928-4.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid, 159.

10 Ibid, 160.

11 Ibid., 6.

12 Ibid., 6.

13 Ibid., 6.

14 Ibid., 6.

15 Ibid., 6.

16 ‘Review of the Police Administration in the Delhi Province for the year 1935’, 1936, File No. 75/14/36. 2-8. Home Department, Police Branch of India. National Archives of India, PR_000005013983.

17 ‘Review on the Police Administration of the town of Calcutta and its suburbs for 1937’. File No. 75/XV/33, Home Department, Police Branch of India. National Archives of India, PR_000004009178.

18 ‘Review of the Police Administration in the Delhi Province for 1932’, 1933, File No. 75/XV/33. 7, 17. Home Department, Police Branch of India, 1932, National Archives of India, PR_0000050131982.

19 East India (North-West Frontier). Papers regarding British Relations with the neighbouring Tribes on the North-west Frontier of India and Punjab Frontier Administration: Presented to both houses of Parliament by Command of his Majesty. Cd. (Great Britain. Parliament); 1901, 496.

20 Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) was a semi-autonomous tribal region in Northwestern Pakistan, that existed from 1947. After the twenty-fifth amendment to the constitution of Pakistan, these areas merged into the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province of Pakistan. The British colonial government controlled these regions through the Frontier Crimes Regulation (FCR). FCR was a special set of laws that was only applicable to the tribal regions during the British rule in India.

21 Ibid 19.

22 Mackeith, ‘Memoirs of a Frontier Policeman in the North-West Frontier Province, Punjab and Sindh 1937-1948’, (Unpublished Memoirs), 1994.

23 Ibid.

24 See. Philip Woodruff, The men who ruled India, The Guardians, pp. 143-9, Also see H. B. Frere, Sind and Punjab Frontier Systems, 22 March 1876. Actually the relative merits and demerits of the ‘close border’ policy on the Punjab frontier had often been compared with another system adopted on the Sind frontier in dealing with the Baluch tribes. Its exponent was Captain Sandeman. In 1877, The Baluchistan Agency was created and Sandeman was appointed the first Agent to the Governor-General in Baluchistan. The policy which Sandeman followed was described as ‘one of the friendly and conciliatory interventions’. He formed a friendship with the Baluch chiefs and made them responsible for the control of the tribes.

25 Edward Henry Hayter Collen, ‘Memorandum on the General Asian Question and Our Future Policy’, 1892, 1.

26 ‘Summary of the Administration of Lord Curzon of Kedleston, Viceroy and Governor General of India, January 1899-November 1905’, 1906, 9.

27 ‘Proposed Formation of a North-West Frontier Agency: Minute by His Excellency the Viceroy on the Administration of the North-West Frontier’, 1900, 17-25.

28 Figure 6, Image Courtesy of the National Army Museum, London.

29 ‘Raids on Bannu and Air Operations Against the Ahmadzai Waziris’, 1938, 32.

30 ‘Proposed Formation of a North-West Frontier Agecncy: Minute by His Excellency the Viceory on the administration of the North-West Frontier’, 1900, 17, 25.

31 ‘Mizz, A Monograph on Governments’ Relations with the Mahsud Tribe, Resident in Waziristan 1924-26’, 1931. 12-23

32 ‘Mahsud Affairs, Desertion of two sepoy of Southern Waziristan with arms and ammunition. Arrest of deserters and recovery of equipment’, 1910.

References

- Ahmed, A. S. (1980). Pukhtun economy and society: Traditional structure and economic development in a tribal society. Routledge.

- Akins, H. (2018). Mashar versus kashar in Pakistan’s FATA: Intra-tribal conflict and the obstacles to reform. Asian Survey, 58(6), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2018.58.6.1136

- Akins, H. (2020). Tribal militias and political legitimacy in British India and Pakistan. Asian Security, 16(3), 304–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/14799855.2019.1672662

- Akins, H. (2022). The strategic logic of policing in British India. Small Wars & Insurgencies, 34(4), 828–852. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2022.2154435

- Alastair, A. M. (1994). Memoirs of a frontier policeman in the North-West Frontier Province, Punjab and Sind 1937-1948. (unpublished memoirs), British Library London, File No. ORW.1993.a.2322.

- Arnold, D. (1986). Police power and colonial rule: Madras, 1859-1947. Oxford University Press.

- Burke, S. M., & Quraishi, A. S. (1995). The British raj in India: An historical review. Oxford University Press.

- Coatman, J. (1931). The north-west frontier province and the trans-border country under the new constitution. Journal of the Royal Central Asian Society, 18(3), 335–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/03068373108725160

- Collen, E. H. H. (1892). Memorandum on the general Asian question and our future policy. Gov. Central Prtg. Off.

- East India (North-West frontier). (1901). (Cd. (Great Britain. Parliament); 496) Papers regarding British relations with the neighbouring tribes on the North-West frontier of India and Punjab Frontier Administration: Presented to both Houses of Parliament by command of His Majesty. Printed for H.M.S.O. by Darling & Son. Indian Office Record, British Library London. File No. W669.

- Edinburgh and London. (1897). W and A K Johnston’s war map of the north west indian frontier (3rd ed.). Edinburgh and London.

- Evelyn, H. (1931). Mizh a monograph on Government’s Relations with the Mahsud Tribe. Oxford University Press. (1979, first published Simla: Government of India Press, 1931), pp.3/4.

- Express Tribune. (2011). Police Act 2011: Baluchistan gets police transfer powers. Express Tribune. https://tribune.com.pk/story/235538/police-act-2011-balochistan-gets-police-transfer-powers

- Fasihuddin. (2008). Identification of potential terrorism: Identification of potential terrorism: The problem and implications for law-enforcement in Pakistan in. International Journal of Criminal Justice Sciences, 3(2), 84–109.

- Gordon, J. E. (1968). The frontier 1839-1947; the story of the north-west frontier of India. Cassel.

- Griffith, R. (1938). The frontier policy of the government of India. Royal United Services Institution Journal, 83(531), 562–580. https://doi.org/10.1080/03071843809419848

- Hopkins, B. D. (2020). Ruling the savage periphery: Frontier governance and the making of the modern state. Harvard University Press.

- Howell, E. B. (1931). Mizh: A monograph on government’s relations with the mahsud tribe. British Library London: Asian and African Studies. File No Mss Eur D696/6.

- Ingall, F. (1988). The last of the Bengal lancers. Preidio Press.

- Javaid, U., & Ramzan, M. (2003). Police order 2002: A critique. Journal of Political Studies, 20(2), 141–160.

- Killingray, D. (1986). The maintenance of law and order in British colonial Africa. African Affairs, 85(340), 411–437. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a097799

- Mahsud Affairs. (1910). Desertion of two sepoys of Southern Waziristan with arms and ammunition. Arrest of deserters and recovery of equipment. Foreign Department, Government of India, National Archives of India, File No 23/26, PR_000004149025.

- Memorandum by H. B. E. (1876). Frere on systems pursued in the administration of the Sind and Punjab frontiers. (22 March NAI, Foreign/Political A/February 1878/nos. 149–156).

- Naseemullah, A., & Staniland, P. (2014). Indirect rule and varieties of governance. Governance, 29(1), 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12129

- North-West Frontier Province and Constabulary. (1940). Papers detailing the history of the Frontier Constabulary to 1940s. India Office Records. British Library London, File No. Mss Eur F161/88.

- North-West Frontier Province and Constabulary. Sir Ralph Griffith: ‘The north-west frontier police’ (nd) dated as pre-1926. Indian Police Collection: British Library, London: File No. Mss Eur F161/95.

- Petzschmann, P. (2010). Pakistan’s police between centralization and devolution (pp. 13). Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/120172/NUPI%20Report%20Petszchmann.pdf

- Philip. (1954). The men who ruled India: The guardians. Jonathan Cape.

- Piliavsky, A. (2013). The moghia menace, or the watch over watchmen in British India. Modern Asian Studies, 47(3), 751–779. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X11000643

- Pollard, A. F. (1909). The British empire: Its past, its present, and its future. League of the Empire.

- Proposals for Deposition of Mir of Hunza on Grounds of Kashmir Misrule in Favour of His and Capable Heir Mirzada Jamal Khan. (1945). File No. 286-C.A. File No. 286-C.A. New Delhi: National Archives of India R_000004001966.

- Proposed Formation of a North-West Frontier Agency. (1900). Minute by his excellency the viceroy on the administration of the north-west frontier. In File No. Vol 37: Foreign Department, Government of India. New Delhi: National Archives of India: R_000004000977.

- Raids on Bannu and Air Operations against the Ahmadzai Waziris. (1939). File No. F-120_38, Home Department, Government of India, National Archives of India, PR_000003037357.

- Ras, J. (2010). Policing the northwest frontier province of Pakistan: Practical remarks from a South African perspective. Pakistan Journal of Criminology, 2(1), 107–122.

- Review of the Police Administration in the Delhi Province for 1932. (1933). 1, file no. 75/XV/33. 7, 17. Home Department, Police Branch of India, 1932, National Archives of India, PR_0000050131982.

- Review of the Police Administration in the Delhi Province for the year 1935. (1936). File no. 75/14/36. 2-8. Home Department, Police Branch of India. National Archives of India, PR_000005013983.

- Review of the Police Administration of the town of Calcutta and its suburbs for 1937. (1938). File No. 75/XV/33, Home Department, Police Branch of India. National Archives of India, PR_000004009178.

- Robb, P. (1991). The ordering of rural india. british control in 19th-century bengal and bihar. In: Anderson, D. M. and Killingray, D, (Eds.), Policing the empire. Government, authority and control, 1830-1940 (pp. 126–150). Manchester University Press.

- Shah, A. S. (2018). KP police reforms: Myths & reality. Daily Times. https://dailytimes.com.pk/274055/kp-police-reforms-myths-reality/

- Sheptycki, J. W. E. (1995). Transnational policing and the makings of a postmodern state. The British Journal of Criminology, 35(4), 613–635. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjc.a048550

- Singh, M. P. (1989). Police problems and dilemmas in India. Mittal Publications.

- Skeen, A. (1932). Passing it on: Short talks on the tribal fighting on the north-west frontier of India. Gale and Polden.

- Summary of the Administration of Lord Curzon of Kedleston, Viceroy and Governor General of India, January 1899-November 1905. (1906). In military department, government of India 72627b–07. National library of Scotland.

- Tripodi, C. (2014). Power and patronage: A comparison of tribal service in Waziristan and South-West Arabia 1919–45. War & Society, 33(3), 172–193. https://doi.org/10.1179/0729247314Z.00000000037

- Typescript by William Harold Adrian Rich (1908-89), Indian Police, Punjab and the North-West Frontier Province 1928-4… India Office Records and Private Papers. British Library London. File. No. Mss Eur D1065/2B, File. No. IOR. Mss Eur D1065/2B Part B "The Punjab Police before 1861.

- Waller, R. (2010). Towards a contextualisation of policing in colonial Kenya. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 4(3), 525–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2010.517421

- Woodruff, P. (1954). The men who ruled India: The guardians. Jonathan Cape.