?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

There were insufficient studies on the pastoralists’ seasonal migration in the district. This study was the first to provide empirical findings across the community. Thus, the primary purpose of this research is to assess the patterns of pastoralists’ seasonal migration in the study area. The study specifically described the spatial distributions of seasonal migration, assessed the temporal distributions of migration and described the main reasons and features of seasonal migration in the study area. The study used a three-stage sampling technique to choose 100 respondents and areas, focusing on group discussions and a questionnaire survey. The data were summarized using percentage and frequency. About 43% and 57% were nonmigrants and migrants, respectively, in the study area. Moreover, the households have migrated between December–February (41%), March–May (3%), June–August (40%) and September–November (6%) in the study area. Similarly, utilizing resources (19%), cultivating crops (26%), coping with conflict (27%) and evading floods (28%) were the main reasons for seasonal migration in the study area. Thus, the pastoral households have been involved in various migration patterns in the study area. Therefore, the concerned institutions should provide need-based policies to improve the livelihood of pastoralists.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Background

The pastoral communities are frequently relying on pastoral lifestyles for a living in Ethiopia. Numerous pastoral-generating enterprises have emerged as viable human living choices in Ethiopia’s diverse locations. According to Nejimu and Hussein (Citation2016) and Getahun et al. (Citation2010), it currently employs four million people, 14% of them are Ethiopians, throughout 133 districts in Afar, Somalia, Oromia, SNNPR, Benchangul-Gumuze, Dire Dawa and Gambella. The main goals of this work are now widely spread throughout Ethiopia, if not ignored. The pastoral-based livelihood strategy, which prioritizes animal husbandry, livelihood systems, economic activity and lifestyle, is centered on the pastoral regions of the nation (Mohammed, Citation2015).

The pastoral system is integral to Ethiopians’ way of life in many ways. It serves as a dowry and a source of milk and meat (George et al., Citation2011). According to estimates from the pastoral sector (CELEP, Citation2017), 80% of Ethiopia’s yearly milk supplies are produced there. Similar to that, it provided a million animals to both domestic and foreign markets thanks to a sizable livestock trading network that connected regional and international markets to local and cross-border markets (FAO, Citation2018). Additionally, it contributed to 12–16% of Ethiopia’s GDP and 30–35% of the agricultural GDP (Birhanu et al., Citation2015), as well as providing roughly 12–17% of the country’s foreign exchange revenues (Adugna, Citation2012).

However, the livelihood of pastoralists has been threatened by the expanding ecological changes and human interference, which have reduced the amount of land that can be used for grazing (Jebessa & Zelalem, Citation2014). The animal production system was stigmatized by the deplorable, unequal and unbalanced agro-ecological resources (Mohammed, Citation2015). The pastoral communities’ means of subsistence are becoming more and more constrained in a downward spiral of resource depletion and dwindling drought resistance (CSA, Citation2013). These cause farmers and pastoralists to compete fiercely for available pasture and water sources (George et al., Citation2011). As a result, the primary grazing lands and water sources are destroyed for various nonpastoral purposes, which is to blame for the escalating poverty in pastoral areas (Haile, Citation2003). For instance, a failure of wealth status has been reported by about 50% of pastoral households.

So, according to Jebessa and Zelalem (Citation2014), these pastoral populations are less prone to pursue sedentary lifestyles. The ability of pastoral households to manage a variety of risks depends on the freedom of movement of animals on shared grazing pastures across a number of nations (Belete & Aynalem, Citation2017; Dawn & Troy, Citation2015). They regularly manage community grazing pastures through a well-articulated migration cycle in order to respond to seasonal change (Ali, Citation2013; Altai Consulting, Citation2015). To make the most of arid settings, pastoralists today employ a large-scale mobile livestock-keeping technique (Mohammed, Citation2015). To get their animals to better pastures and water sources, they retain a great deal of dry-season mobility (Oxfam, Citation2018; Samuel, Citation2014). According to François (Citation2007) and ECA (Citation2017), they still have a great deal of dry season mobility that allows them to move between their home range, wet season rangelands, dry season rangelands and drought reserve areas. This allows them to access and make use of the varied terrain of the rangelands as well as the temporal and spatial changes brought on by climatic variations (Oxfam, Citation2010).

2. Statement of problem

Political, economic and social exclusion and marginalization constantly put pressure on the pastoral communities to migrate (Becky & Brigitte, Citation2016). The pastoralist seasonal migration system in Ethiopia has received little attention from development policies and plans. Sedentarization is often emphasized in development strategies as a means of escaping poverty; however, this ignores mobility as a means of production in dry regions (Belete & Aynalem, Citation2017). The pastoral people have long been pressured by the various governments to embrace a settled lifestyle, which forces them to practice agriculture instead of migrating (David, Citation2009; François, Citation2007; Samuel, Citation2014). The access to rich rangelands for farming systems may have come under the government’s secretive control (Andry, Citation2017). The pastoralists’ most productive rangeland access points for dry season grazing have been abandoned in favor of agriculture (Jon, Citation2014). These regulations impeded access to vital grazing regions and hindered the movement of cattle along a long, established migration route, all of which lead to forced migration for large-scale land concessions, involuntary settlements and changes in nomadic pathways and patterns (Jeremy et al., Citation2016). For the purpose of carrying out the sedentarization initiative, about 88,000 households have settled along the banks of rivers in the Somali region (Devereux, Citation2006).

This process exacerbates the country’s pastoral households’ suffering and the destruction of its natural resources. The country’s limited resources are easily compensated by population growth in some areas. The proportion of farmers to established pastoralists is increasing, which has led to a fall in opulent vegetation (Clarisse & Augustin, Citation2018) and the spatial fragmentation of the natural vegetation cover of common rangelands (Hussein, Citation2018). By severely limiting access to dry-season pastures, depleting wet-season pastures, and deteriorating rangeland resources, it wreaked havoc on pastoralists’ way of life and caused bush encroachment and declining cattle herds (Solomon, Citation2018). For instance, livestock strain on the remaining grazing area and the practice of traditional transhumance are both being impacted by the conversion of grazing fields to agriculture in the highlands of the Bale Eco Region (BER) (Belete & Aynalem, Citation2017).

The pastoralists move between the two areas on a seasonal basis in the Gambella region in general and the Itang special district in particular. These tribes relocate every season to transfer their herds to pasture and water sources then return the following year when the grasslands have grown to varied sizes. While people who practice mixed agriculture live in permanent settlements, pastoralists wander from one place to another in quest of grazing (Yilebes, Citation2017).

The basic seasonal movement patterns of pastoral households have, however, garnered very little attention from the academic communities. According to several research findings (Belete & Aynalem, Citation2017; Ben & Michael, Citation2002), pastoral movement is a common practice. In contrast, the primary causes and distinctive characteristics of pastoralists’ seasonal migrations were not fully investigated. Additionally, little research has been done on the extensive spatial patterns of seasonal migrations. For instance, some researches (Belete & Aynalem, Citation2017; Wondwosen, Citation2017) have highlighted the pastoralists’ extraordinary rural-rural migration. By the same token, there were no studies conducted into the temporal distributions of seasonal migration in Itang. Therefore, this study had tried to assess the patterns of pastoralists’ seasonal migration in order to provide empirical findings to the existing literature.

3. Objectives and research questions

3.1. Objectives

The main objective is to assess the patterns of pastoral households’ seasonal migration in the study area. The specific objectives of this study are;

To describe the spatial distributions of pastoral households’ seasonal migration

To assess the temporal distributions of pastoral households’ seasonal migration

To describe the reasons and features of pastoral households’ seasonal migration

3.2. Research questions

What are the spatial distributions of pastoral households’ seasonal migration?

What are the temporal distributions of pastoral households’ seasonal migration?

What are the reasons and the features of pastoral households’ seasonal migration?

4. Theoretical foundations

4.1. The concepts

There are many groups around the world who use migration as one of their primary means of subsistence. Migration was defined by Befikadu (Citation2012) as the temporary or permanent movement of people from one geographic region to another. This leads the IOM (Citation2017) to define migrants as people who have moved away from their long-term residence across international borders or within a nation, regardless of the person’s legal status, regardless of whether the location is voluntary or involuntary, regardless of the cause of the movement or regardless of the length of the stay. Seasonal migration, according to Jessica (Citation2008), is when people move away from their home country or region for a few months each year. In terms of the amount of time spent in a specific area (mostly short- and long-term seasonal migrations), Nathaniel (Citation2019) intellectualized the seasonal migration pattern. Seasonal migration in this study refers to the annual movement between two established communities.

Livestock production is the dominant livelihood activity in low-lying or dry-land areas of the world. The activity basically supports the living standard of most households in the dry-land areas. Stidsen (Citation2006) defined pastoralists as persons or communities engaging in the economic system in which they rear, raise and rear a large number of livestock. On the contrary, pastoralists are the people who rely on mobile livestock rearing as the main source of their livelihood (Nori & Gemini, Citation2011). Besides, pastoralists are also people who receive more than 50% of their incomes from livestock and livestock products as demanded from rangeland resources (Buono & G, Citation2016). Therefore, in this study’s perspective, the pastoral households were the households whose main livelihood activity is livestock production in the study area.

4.2. Push-pull theory

The compass for this investigation was the push-pull theory. In the context of this study, it is a crucial explanation for the seasonal movement of pastoral households. According to the theory, migration is dependent on the coexistence of both positive and negative forces from two distinct regions. It was discovered that the decision to immigrate is influenced by personal variables, intervening barriers and factors related to the locations of origin and destination (Hein, Citation2007). Due to the ecological, economic and political circumstances, the pastoral households are constantly moving to new locations. According to the idea, push forces are those that compel people to leave their places of origin, whereas pull factors are those that draw them to their destinations (Linger, Citation2018). For instance, Gunvor (Citation2010) came to the conclusion that one of the causes endangering and compelling people to relocate to a more stable environment is climate change.

4.3. Patterns of migration

The pastoral communities rely on seasonal cattle migration to various locations throughout the world. According to Belete and Aynalem (Citation2017), they are utilizing seasonal migratory patterns that change from year to year across the various nations. Migration is higher in Kenya during the long rainy season than it is during the short rainy season (Dinah, Citation2018). This migration often takes place during the dry season in pastoral communities with large numbers of cattle in search of food and water (Frankenberger & Smith, Citation2015). In Kenya, the long rainy season saw about 62% more pastoral migrants than the short wet season (Dinah, Citation2018). There are two migratory seasons in the Ethiopian Gambella region. The output of pastoralism in the area coincides with the transhumance migration between wet season villages in June and October and dry season camps in November and May (Wondwosen, Citation2017).

The pastoralists from their far homelands are also mesmerized by the diverse geographical patterns of migration. In Northern Kenya, where there are 33% pastoral communities, there is a more long-term shift in the migration flow from rural to urban regions (Dinah, Citation2018). According to Riley et al. (Citation2012), between 8,000 and 9,000 nomadic pastoralists from Tanzania moved to Dar es Salaam in 2012. According to Zoe and Helen (Citation2012), pastoral groups frequently traverse borders with their animals. Due to the drought and environmental change in the Sudano-Guinea region, pastoralists are migrating abroad (Bassett & Turner, Citation2007). The pastoral groups in Ethiopia saw significantly greater rural-rural migration than rural-urban mobility (Jebessa & Zelalem, Citation2014).

Additionally, pastoral populations migrate across African nations on a seasonal basis for a variety of reasons. More obviously, pastoralists frequently migrate in order to deal with seasonal susceptibility. One of the main ways pastoralists have historically managed risk and uncertainty in dry environments on the continent is through cattle migration (Belete & Aynalem, Citation2017). In other regions, pastoral migration is a crucial tactic for balancing the resource disparities between pastoral communities (Hanne, Citation1999). In quest of range resources, 13.3% of Borena and 3.7% of Jijiga pastoralists in Ethiopia have been relocated (USAID, Citation2015). The pastoralists in Ethiopia’s Gambella region go to open forest riverine areas to feed their animals (Wondwosen, Citation2017).

5. Research methodology

5.1. Description of the study area

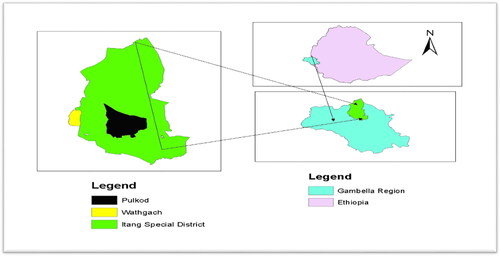

The study was done in Itang woreda which is distanced for about 45 km from Gambella capital city. This area is distinctive for two main reasons. Initially, the district is considered as an autonomous from the region. It is not regarded as a part of three zones. It includes Nuer, Anuak and Oppo as the main indigenous tribes. Similarly, the woreda has 1 urban and 22 rural lowest Ethiopian administrative unit (). Its neighboring zones or regions are the Oromia Region on the north, by the west is situated by Nuer Zone, and by the south and southeast was surrounded by Anyua Zone. Inside the Gambella, it is positioned at 8°15′ N latitude and 34°10′ E longitude.

Then, it is one of the sparsely populated areas in Gambella. The Itang special district has only 42,000 populations (Alemseged & Tamiru, Citation2014). Within these populations, approximately 20,589 are females whereas 21,411 are males. Likewise, 8,213 housing units and an average of 4.8 individuals per household were determined by simultaneously counting 8,744 households in the district. Roads, electricity, telecommunications and social services, primarily the district’s schools and medical facilities, remain inaccessible to these rural settlements. There are still not enough roads linking the Kebele to the other infrastructure services in the district. Throughout the district, there is only one health center and one main asphalt road. Individuals still travel by foot to receive medical attention and educational services from the district in their rural communities.

The pastoral communities prosper in favorable environmental conditions. Pastoralism as a profession is supported by the pastoral setting. The district is home to numerous bodies of water, natural woods, wildlife, fish and bees. Nearby is the Baro-akobo River, which provides a significant amount of water all year round. A little rain falls here occasionally. The beginning of the year is in the late spring or early summer, and it concludes in the fall. Also, from a policy standpoint, the pastoral lands in this district are neglected. In the district’s pastoral areas, project interventions still need to be completed.

The local economy in this pastoral region varies from place to place. In this district, the people practice both animals and crops production. Livestock has formerly constituted the majority of the population’s livelihood. The major productions in pastoral areas include piggery, beekeeping, fishing and animal husbandry. This society has a conventional production method. With their native breeds, pastoralists practice free-range production. People in the Itang district move between two places mainly upland and river bank. This migration is influenced by the environment, the seasons and the possibilities available in their local settlements.

5.2. Research philosophy

When conducting research, many researchers see methodology and the guiding philosophy as two challenges that are inextricably linked (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018). According to Chepp and Gray (Citation2014), this philosophical foundation aids researchers in addressing issues such as what constitutes the social reality ontological base, what it means to understand the social reality epistemological basis and how to investigate the social reality methodological basis. As a result, it is becoming increasingly clear that there is no single research philosophy that predominates in academic research and that composite utilization is instead strongly encouraged.

This study is, therefore, situated within the pragmatic philosophical premise that governs mixed research methodologies where researchers are permitted to depend on both quantitative and qualitative hypotheses. According to Onwuegbuzie and Johnson (Citation2006), pragmatism is results-driven, concerned with understanding the meaning of things and focused on the study’s output (Biesta, Citation2010). Both positivist and interpretivist viewpoints can be used in conjunction with one another (Saunders et al., Citation2009). This distinctive feature of the pragmatic philosophy of research opens the door to the use of multiple methodologies, permitting the application of various worldviews and assumptions as well as varied types of data collection and analysis through the use of qualitative and quantitative procedures (Creswell, Citation2014).

5.3. Sampling procedures and sample size

5.3.1. Sampling techniques

The sampling technique of this study was three stages to choose the study sites and research participants. In the first stage of sampling, the purposive method was used to select the Itang District. Because of its reputation for seasonal migration, the presence of three different tribes there, and the dearth of studies on the seasonal movement of pastoralists, these were the main reasons for choosing the district. Again, the district has an important capacity for cattle rearing across the region. In the second stage of sampling, Pulkod and Wathgach kebeles were selected by a simple random method. This sampling was used to reduce the bias of selection. Last but not least, the simple random sampling process was used to select the households. This was done through the lottery method to give the chance to every participant of the study.

5.3.2. Sample size determination

Mathematical methods were used to choose the sample households for this investigation. Among these methods, the sample size was calculated by using Arsham (Citation2007): at a 95% and a 5% degree of accuracy were utilized.

Where, n = sample size, 0.25 = constant number and = standard error (5%).

This method of sample size determination is used where the dependent variable is categorical.

N = = 100 participants. The sample size was made to be small due to financial and time constraints during data collection. This gap was minimized by employing different methods of data collection. Hence, the study respondents were carefully chosen in proportional to size.

5.4. Data collection methods

The mixed research approach was applied in this study. The various data collected from this study allowed for strong conclusions. Thus, the main types of data for this study were quantitative and qualitative data. These data were used to minimize the limitations of each type of data from the study. Accordingly, the primary and secondary data were acquired for this investigation.

The core information came from first-person narratives that were directly collected from the interviewees. Questionnaire survey method and focus group discussions were used to collect these data. One hundred respondents in the study area completed a written questionnaire as part of the interview schedule, which was used to gather quantitative data. Then, one of the techniques utilized to collect the qualitative data was the focus group discussion. It is a technique for gathering specific information from a group of people by double-checking the data. One group, with five people from each kebele, was involved. This small group was selected to handle the group members without a doubt. The discussion was done with a girl and boy who were between the ages of 7 and 10, women, elder and chairperson.

Furthermore, a literature research or a document analysis was used to obtain the secondary data. These facts are from published records in pastoralist migratory zones. Theses, journal articles, conference papers and official reports from around the world served as the primary data sources.

5.5. Methods of data analysis

Finding pastoralists’ seasonal movement patterns in the studied areas was the main goal of this research. In order to analyze the quantitative data, percentages and frequencies were used. In order to better understand seasonal migration distributions in the studied area, descriptive statistics were used. These are crucial for providing a more thorough summary of the data. Tables were also used to present the data throughout the investigation.

Thematic analysis was used to study the qualitative data on the other hand. Prior to categorizing and organizing the qualitative data into connected themes, focus group conversation transcripts were first converted into a written form. Spatial distributions, temporal distributions, and reasons and features of seasonal migration were the main concerns. The durations, seasons, directions, status, motives and characteristics of seasonal migration were the focus themes in the meantime.

5.6. Ethical considerations and expected results

5.6.1. Ethical considerations

The ethics of scientific research were taken into account in this investigation. The university has given authorization for the data collecting. The participants in the study were also made aware of the article’s goal. Similar to that, it has asked the respondents if they consent to data collecting. The research subjects were informed of the study results’ confidentiality.

5.6.2. Expected results

There are immediate results from this study that would benefit society. The status of seasonal migration was made known. Besides, the directions of seasonal migration were demonstrated. In addition, the time of seasonal migration was brought into the scientific arena. Likewise, the duration of the seasonal migration was justified. Meanwhile, the main reasons for seasonal migration were presented. Finally, the unique features of seasonal migration were demonstrated.

6. Results and discussions

6.1. Spatial distributions of seasonal migration

6.1.1. The status of seasonal migration

One of the key strategies for raising cattle in the Itang special area is seasonal mobility among pastoralists. It is regarded as necessary for almost all communities’ economic survival. According to Adriansen and Nielsen (Citation2002), Africa’s pastoral production methods are known for their mobility. Because of this, the multi-analysis of seasonal migration patterns (MASMP) has acquired special information on the mobility prowess of pastoralists. The pastoralists’ substantial interest in seasonal migration was also clearly noticeable in the districts. More than half (58.7%) of seasonal migrants were located in Pulkod kebele, while 54.1% were discovered in Wathgach kebele, per the assessment ().

Table 1. Migration status of the sample households.

The results of focus group talks show that security concerns among those who live close to communities afflicted by armed conflict are the most important factor for migratory disparities. In fact, a large number of Pulkod natives reside close to Itang town, which is the area of the Gambella region most afflicted by ethnic conflict. Additionally, Wathgach’s nonseasonal migrants now outnumber those from Pulkod kebele. According to the survey, nonseasonal migrants made up 45.9% of pastoralists in Wathgach kebele and 41.3% in Pulkod kebele, respectively (). Sub-Saharan Africa, on the other hand, is becoming more and more marked by migration (Awinia, Citation2020). This variation is due to the two kebele in the research region having different livestock water supply levels. There are numerous pools around pastoral cottages in Wathgach kebele.

6.1.2. Directions of seasonal migration

Pastoralists migrated seasonally in the study area using a variety of different spatial migration patterns. It is not surprising that during the seasons, the pastoral groups in the study region move to other places and travel different routes. The loss of interior and remote regions and the increase in immigrant labor are two significant shifts that have changed the rural environment in recent decades (Nori & López-I-Gelats, Citation2020). As a result, the pastoralists primarily move in the rural-rural, rural-urban and urban-rural directions, covering distances of between 15 and 37 km in each direction. According to a survey, the percentages of pastoralists who have moved from rural to rural, urban to rural and rural to urban areas, respectively, are about 54%, 33% and 13%. Due to the district’s rural and urban living conditions, many pastoral households have moved there. To adjust to shifting economic and social contexts, the households have employed migration techniques (Zhang, Citation2012).

6.1.2.1. Rural-Rural migration

Much of the seasonal mobility of pastoralists is frequently connected to rural life in pastoral areas in these migration patterns. Pastoral families tend to travel to and from far-off places. These pastoralists routinely move between the communities of Wathgach, Makot, Kule and Ngote in the study area. In Pulkod and Wathgach kebeles, respectively, 52.4% and 56.8% of pastoralists shifted seasonally from rural-rural regions during the reference period (). According to Abdelah that supports this conclusion, pastoralists from the Afar region move between Talo, Teru and Megale in times of adversity.

Table 2. Directions of seasonal migration.

People move seasonally from rural to rural in pursuit of grazing land, livestock water sources and field crop gardening, primarily maize and sorghum, in the research area, according to the focus group comments from each kebele. To ensure food supply and pasture sustainability, pastoralists rely on intensive herding (Liao et al., Citation2014). Water and pasture are harder to come by in dry seasons. During dry seasons, pasture and water become scarce in woody places. Wet river banks and rain during rainy seasons cause the pastoralists to produce crops in the study region. In the long run, temperature had a statistically smaller impact on nomadic movement in ancient China than did precipitation (Pei & Zhang, Citation2014).

6.1.2.2. Urban-Rural migration

The challenge of producing animals in cities deters pastoral migration to rural areas. Pastoralist settlements are migrating to farther-flung areas. These pastoralists routinely move from Itang and Tharpam to the isolated Wathgach, Makot, Ngote and Kule villages in the study district. In Pulkod and Wathgach, seasonal migration of pastoralists from urban areas to rural regions was about 31.7% and 35.1%, respectively, last year (). According to Paolo et al. (Citation2018), pastoralists moved from the urban regions of Cameroon to the Mbam and Djerem national parks.

The focus group talks revealed that security and the flood status in the study area are the key motivations for urban-rural migrations. In fact, ethnic conflict, which is common throughout the region, is constantly a threat in the urban areas, especially Itang Town. In China, there are disputes between pastoralists and farmers (Pei & Zhang, Citation2014). In other instances, the area is prone to yearly floods since a large portion of it is constructed on the Baro River banks (BRBs).

6.1.2.3. Rural-Urban migration

The possibility of moving to metropolitan areas within pastoral zones inspires some pastoralists. The seasonal shift of pastoralists to pastoral areas is accelerated by the striking facilities in cities. These communities relocate to the towns of Itang and Tharpam from the rural villages of Wathgach, Makot, Ngote and Kule. Thus, some of the pastoral households involved in migration from rural to urban areas. In Pulkod and Wathgach kebele, respectively, pastoralists have temporarily shifted from rural to urban areas, making up 15.9% and 8.1% of the total (). Pastoralists from Cameroon commonly move to the town of Mayo-Reya division, according to Paolo et al. (Citation2018).

Throughout the course of the year, numerous pastoralists move to various places in the study area for a variety of reasons. In order to raise their standard of living in the nearby towns, one type of pastoralist migrates to urban areas in quest of trading possibilities and livestock veterinarian services, according to the results of a focus group. To benefit economically, individuals’ pastoralists go to the city (Izumi, Citation2017).

6.2. Temporal distributions of seasonal migration

6.2.1. Seasons of migration

6.2.1.1. Winter season

The study area recorded the varying seasonal migration patterns between the two kebeles. Because of this, many households have observed that the main time of year that many pastoralists roam around the Itang special district is winter. In Pulkod and Wathgach kebeles, respectively, seasonal relocating pastoralists made up 47.6% and 56.8% of the population between December and February, according to the survey (). According to Anna and Christian (Citation2013), the winter months are when many Russian pastoralists start their journey.

Table 3. Seasons of migration.

The findings from focus group discussion, therefore, showed that this season’s movement is highly influenced by weeding, harvesting and grain grading. In the study area, the water from the river recedes in December. As a result, pastoral populations relocate to the river banks in the study area to establish cereal crops, primarily different kinds of corn. By January, the wheat crops had reached full maturity in the rural districts. In order to gather the dried products, pastoralists move to the fields. According to Nelson et al. (Citation2020), the pastoralists appear to be moving toward maximum concentrations of 1.47 pastoralists per 1 km2. In the pastoral areas, the grading of already-harvested crops takes place in February. As a result, pastoralists change their practices in order to level grain crops appropriately.

6.2.1.2. Spring season

Some residences with various vistas were temporarily relocated in the Itang special district in the spring of the year. In the territory, people and animals still roam between the marshes and the Baro River. In Pulkod and Wathgach kebele, respectively, between March and May, about 3.2% and 2.7% of pastoralists relocated (). Nathaniel (Citation2019), on the other hand, asserted that some pastoral households in northern Nigeria shift between late February and April. In this context, the focus group discussion connected spring migration with handling of post-harvest crops, looking for water points and grazing pastures across the district.

The most significant activity in the study area during the month of March was the gathering of dried crops from the fields. The districts previously organized cereal goods are gathered and stored throughout this month by the enormous pastoralists who move between the agricultural areas. In the research area, many pastoralists normally relocate in April to thresh and winnow the stored grains. In the meantime, pastoral areas’ grazing and water areas began to dry up in late April and early May. At that time, pastoral people have been daily trekking their cattle to the reserve grazing areas and water sources in the research region. Some of them started moving southward in Tanzania in search of grazing grounds (Izumi, Citation2017).

6.2.1.3. Summer season

Several pastoralists in the Itang special district relocate seasonally throughout the summer. At Pulkod and Wathgach kebele, it was determined during the field survey that between June and August, roughly 42.9% and 35.2% of pastoralists were projected to move (). Anna and Christian (Citation2013) found that around 15 migrant units pass through the region in Russia during the summer. In this context, it was shown through the focus group discussion that migration during this time of year is closely related to the cultivation of wooded area, extreme river overflow and grain storage.

In the district, the rainy season often starts in early June. It encourages family heads in the district to move to woodland area for crop cultivation as a result. Throughout the month of July, the Baro River spills into a number of pastoral rural settlements. At that time, the entire household moves to higher land to avoid the dangerous river water threats. In August, the agricultural crops in the forested areas get drier. The members of the overall pastoralist team walked across the wooded land areas as a result of the harvesting and collection of mature crops in the research location. According to Sulieman and Ahmed (Citation2017), the households spend 77% of their annual cycle producing in the summer regions.

6.2.1.4. Autumn season

Many pastoral dwellings were moved across the area during the fall season. Approximately 6.3% and 5.4% of pastoralists in Pulkod and Wathgach kebele, respectively, relocated between September and November (). According to Nathaniel (Citation2019), agricultural harvesting and the supply of fodder take place in the summer. This implies that the floods and farming tillage are the main reasons of pastoralists to relocate throughout the area, based on the result of group discussion. For instance, the pastoral homelands are severely flooded in early September by the Baro River’s overflow.

As a result, pastoralists frequently sought safety in the study area. The pastoralists leave in October after an unwanted plant takes root in a farm region. From this point on, the household heads relocate to the Baro River to remove the vegetation from the agricultural fields. In November, the banks of the Baro River, which serve as the location for sowing grains, retreated. Subsequently, a few of the pastoralists moved to the Baro River to start farming across district. Tanzania’s Lake Rukwa shore is now home to a pastoral population (Izumi, Citation2017).

6.2.2. Duration of seasonal migration

6.2.2.1. Temporary migration

Due to the short-term migration intervals, some pastoralists have spent less than 2 months throughout seasonal migration. In the research region, between 28.6% and 40.5% of pastoral households had spent a maximum of 1–2 months at the endpoint during seasonal migration (). In distant areas, pastoralists spend anywhere between 25% and 50% of their annual cycle, according to Hussein and Helen (Citation2019) research. According to the focus group discussion, issues that cause pastoral communities to relocate to other locations in 2 months or less include overgrazing, violence, livestock disease and cattle raiding organizations. Participants in the Wathgach kebele claim that diseases and cattle theft by members of the Murle tribe and other individuals force pastoralists to spend a few months temporarily settling in one place. The Pulkod panelists similarly showed that pastoralists frequently move between the two localities throughout the region due to a shortage of suitable grazing areas and security concerns.

Table 4. The sample households’ durations at destination.

In pastoral areas, medium-term migratory episodes have outweighed previous times. Accordingly, 66.7% and 58.8% of pastoralists in the kebeles of Pulkod and Wathgach, respectively, have kept up their seasonal migration for 3–5 months (). Results revealed that the majority of seasonal migrants in the study area spent the duration of their 3- to 5-month move in pastoral homes. According to Suresh and Gupta (Citation2011), 32% of pastoralists in semi-arid Rajasthan temporarily were migrated their sheep. Pastoral communities are able to stay in place for a long time due to security and flood worries with the support of focus group discussions. In actuality, pastoralists are residing in certain locations for longer due to decreased flux and flooding.

6.2.2.2. Permanent migration

Across the study district, some pastoralists spend months at a time in the same area. These families have typically been gone from their homes for 6–12 months. According to a survey, 4.8% and 2.7% of pastoralists have spent 6–12 months in Pulkod and Wathgach, respectively (). Some pastoralists, according to Yonad (Citation2017), do not live according to a seasonal or circular movement pattern.

Then, the result of focus group discussion displayed that pastoralists preferred to stay in one place for several months in order to accomplish other fundamental objectives. The pastoralists who produce crops along the Baro River and woodland are those that stay in one place for longer periods of time, according to the participants. Similar to this, some other pastoralists spend a lot of time fishing and making use of the area’s abundant animal fodder. They moved into a wide, swampy area that had never been settled, where they started a massive farming operation (Izumi, Citation2017). They were able to relocate and farm as needed, thanks to their animals.

6.3. Reasons and features of seasonal migration

6.3.1. The main reasons of seasonal migration

6.3.1.1. Evading floods

The primary aims of pastoralists’ seasonal mobility were described in the study region. The flooding of the Baro River in the research region is a distinctive feature of the seasonal migration of pastoralists. It is especially dangerous when rivers overflow in pastoral areas during the rainy season. Because of this, some pastoralists relocate annually to avoid floods along the Baro River. In Pulkod and Wathgach kebeles, respectively, 22.2% and 37.9% of pastoral households have left to avoid the floods, according to the report (). According to the same source, seasonal floods of the Awash, Wabi-Shabelle, Ganelle and Omo rivers control the movement of Afar, Somali and South Omo pastoralists. The result of discussion showed that the pastoralists relocate to new areas as the Baro River’s water level rises above their homes. The overflow of river water becomes an overwhelming in the study area throughout the summer because of the country’s highlands and lowlands receiving significant rainfall.

Table 5. The reasons of seasonal migration.

6.3.1.2. Cultivating crops

In the study area, crop cultivation drives seasonal movement for pastoral households. In the studied area, many pastoralists cultivate crops at specific seasons. In order to grow crops on a seasonal basis, pastoralists move to various locations. A field survey revealed that in Pulkod and Wathgach kebeles, respectively, over 27% and 24.3% of pastoralists had temporarily shifted to grow crops (). In light of this, Nathaniel’s (Citation2019) research found that the movement patterns of pastoralists are influenced by the locations of farming villages. According to the focus group discussion, pastoralists move about the study area on a regular basis to plant crops around BRB in the dry season and on woodland in rainy season.

6.3.1.3. Utilizing resources

The main objective of seasonal migration in pastoral environments is to maximize resource use. By moving seasonally, pastoralists can benefit from the water and pasture resources. The search for pasture and water resources compelled the pastoralists to travel great distances. The results show that in Pulkod and Wathgach kebeles, respectively, around 14.3% and 27% of pastoral households have moved between the Baro River and woody areas (). Findings from Kuenga et al. (Citation2013) indicated that maintaining grazing areas is the main driver of pastoralist mobility during the winter. During dry seasons, the research area’s grazing pastures and water sources gradually get smaller. These pastoralists relocate according to the seasons to minimize resource depletion in particular regions of the study area. The focus group discussion revealed that the pastoralists move between the two allocated locations to sporadically use the district’s pasture and water resources. The findings indicated that the three primary goals of livestock movement are to obtain grazing land, a market location and salt water (Mersha & Tadesse, Citation2019).

6.3.1.4. Coping with conflict

A resource issue is what drives the district’s seasonal emigration of pastoralists. In the various studied areas, pastoralists seem to be under increased stress due to this tremor. Security is seriously threatened by environment-driven human migration, according to Amusan et al. (Citation2017). As a result, pastoralists move away from the study district on a seasonal basis to avoid conflict. In Pulkod and Wathgach kebele, respectively, about 36.5% and 10.8% of pastoral households have left to flee the unrest in their respective regions (). In the study region, pastoralists are constantly relocating to places where there is less contention over water and grazing resources. Samuel (Citation2016) discovered that when there is instability, pastoralists in the Afar region alter their grazing areas.

Of course, Itang is the only district in the Gambella region where the Nuer, Anuak and Oppo ethnic groups have engaged in the most intense hostilities. The focus group talks revealed that pastoralists frequently move during times of strife. As a result, pastoralists move every season to keep the Itang district peaceful. The households necessary migrate for conflict early warning (Ben & Michael, Citation2002).

6.3.2. The main features of seasonal migration

6.3.2.1. Joint mobility

Migration among pastoralists is a well-organized mechanism in pastoral areas. Pastoralists perform coordinated movements during the seasonal emigration. These pastoralists move in groups during certain seasons in the pastoral areas. In Pulkod and Wathgach kebeles, respectively, 47.6% and 40.6% of pastoralists engaged in joint mobility during the seasonal emigration (). Around 80% of pastoralists travel in groups when shifting to new locations, according to Nathaniel’s (Citation2019) research.

Table 6. The main features of seasonal migration.

The focus group discussion made clear that migrations are planned in groups to take care of people, animals and interpersonal relationships. As a result, in the research region, the chiefs of families and the local authorities plan the daily animal treks as well as the migration of the pastoral communities. The population is moving in order to create herds and have an impact on political leadership (McCabe et al., Citation2014). The children, who may arrive after the entry of livestock safety personnel or who may stay in any event, are the most significant members of the pastoralist families on the routes that leave the other families behind during this time. Women used to frequently travel with their family herds in the past, but today, with the exception of a very small number of women, the majorities stay at home with their kids while the men tend to the herds (Bailey, Citation2012).

6.3.2.2. Joint camp

In pastoral areas, the settlement of pastoralists has long been considered the norm. Pastoral homes assemble in one location, leading in the development of separate communities next to one another. In Pulkod and Wathgach kebeles, respectively, 22.2% and 32.4% of pastoralists have built cooperative camps during seasonal migration (). In pastoral settings, people typically plan various settlements to be adjacent to one another during or after seasonal migration. Pastoralists are migrating in a broad spatiotemporal trend toward the southeast toward the Ethiopian border (Nelson et al., Citation2020). The colonization of these pastoral villages was mostly carried out by clans. During migration, people with the same clan background resided in the same regions of the district. The main intentions of joint camp are to reduce cattle theft and outsider attacks on their entire communities, as well as to create lasting community relationships in the district. In choosing where to set up camp, the herders take camp security into account (Ono & Ishikawa, Citation2020).

6.3.2.3. Communal grazing and watering

Pastoralists combine their resources and use them together throughout their migration routes. The same resources are used by researchers and pastoralists in the study area. For example, pastoralists in the study area coordinate the same grazing and watering of the cattle. During seasonal migration, 19% and 21.6% of pastoralists in the kebeles of Pulkod and Wathgach, respectively, engaged in communal grazing and watering of animals (). Samuel (Citation2016) claimed that pastoralists in the Somali region follow a system where everyone is allowed to use land resources.

As a result, the villagers in the study area herded their cattle into the shared grazing and drinking areas all at once. Despite having an abundance of natural and human resources, some places are struggling, and water stress is making things worse (Nagabhatla et al., Citation2021). So, the mature male households undertake livestock trekking during the winter and spring seasons as a result of the high levels of insecurity and cattle rustling in the study. Most kids and some women regularly take care of small domestic animals including calves, sheep and goats. Gender, family and religious institutions play a significant role in today’s migration difficulties. According to the participants, the major objectives of this feature are to prevent theft, attacks by wild animals and the distribution of range resource pressure among pastoralists throughout the region. Human and animal security underlines the necessity for protection from migration-related challenges to livelihood security, which is still hotly contested (Ibrahim et al., Citation2020).

6.3.2.4. Mutual support

Mutual assistance is frequently given in the district’s rural pastoral areas. Pastoral households have used the traditional means of support during seasonal migration. Pastoral communities in the district have a tradition of assisting one another during migration. In the kebele of Pulkod and Wathgach, respectively, 11.1% and 5.4% of pastoral households engaged in mutual help during seasonal migration (). Accordingly, a study conducted in Afar indicated that pastoral communities build a communal support system, which is a critical component of their success (PFE, IIRR and DF, 2010).

When there are sudden shocks in the area at the moment, this strategy helps pastoral groups. A focus group discussion revealed that pastoralists in Wathgach kebele assist one another in finding lost animals, construct thatched homes and exchange information regarding local animal breeding. When choosing where to set up camp, the herders take into account territorial bonding and commitment to the area (Ono & Ishikawa, Citation2020). Similar to this, the discussants in Pulkod kebele indicated that pastoral households had formed a combined security organization in the study area for the protection of both people and cattle, exchanged food and labor, and transported sick to health centers. Nomadic migration is extremely intentional and focused on reaching particular production or other objectives (Salzman, Citation2002).

6.4. Contributions

This study is the only scientific research conducted at the district, state and nationwide levels. It was not done anywhere in the country. Thus, the results of this study can have many contributions. For example, the study can be a source of information for researchers who want to conduct studies on a similar topic. Likewise, it could provide the knowledge needed by livelihood experts working in pastoral areas. Moreover, it will initiate the design of the interventions in the pastoral areas for the concerned institutions and organizations, thereby improving their living conditions.

7. Conclusions

7.1. Theoretical implications

The theory that was applied in the previous studies does not encompass all aspects of seasonal migration in pastoral households. The push-pull paradigm is used to theoretically explain the pastoral migration (Pei & Zhang, Citation2014). Minorities who live as nomads may migrate due to climate change. The main causes of pastoral migration are then changes in land use and land tenure (Wafula et al., Citation2022). In contrast, the herders control theory explains the migration of pastoralists (Dwyer & Istomin, Citation2008). According to some (Coppolillo, Citation2000; Dwyer & Istomin, Citation2008), nomadic movements are best described as the result of the interaction between animal behavior and the adept behaviors of the herders. By keeping the herd together and avoiding dangers, this can be accomplished. It only took into account nonecological elements with animal behavior and ecological factors with the deft activities of the herders.

Therefore, the comfort zone theory could be considered. This theory encompasses various dimensions of pastoral migration. Hence, pastoral households migrate to find comfort zones for their production and needs. In many different sectors, migration of mobile households is planned to achieve production objectives (Salzman, Citation2002). It is not only used for single production. The pastoral migration aims mainly at crop production, animal rearing and fishing. Similarly, migration maintains political, environmental and social cohesion. The key factors driving pastoralists to migrate are the need for pasture, water supplies and alternate markets (Wafula et al., Citation2022). Moreover, the change in direction of pastoral migration has important implications for mobility. It generates the flexibility of pastoral settlements through the change of spatial distributions.

7.2. Practical implications

The seasonal migration is a well-established practice for cattle husbandry in Itang district. Between the two main settlements, the pastoralists frequently move. At certain times of the year, pastoralists continue to move between the Baro River and woodland. So, in the pastoral regions of the Gambella region, seasonal migration functions as a cultural production strategy that cannot be disregarded. It is a tactic used in pastoralist areas to handle stress and shock in the animal production systems.

Thus, pastoral households have been involved in various migratory patterns. The numerous pastoralists have engaged in different spatial distributions in the study area. It was also common for pastoralists to move throughout the various seasons of the year. For various reasons, pastoralists migrated back and forth in different directions. In other words, the seasonal mobility of pastoralists includes a variety of characteristics. Therefore, the concerned institutions should provide need-based policies to improve the livelihood of pastoralists. The focus should be on awareness creation, diversified policy and social services that support policy in pastoral areas.

7.3. Limitations

This study has some drawbacks. The geographical coverage of this study is minimal. It was done in one district, particularly in the two lowest Ethiopian administrative units. Similarly, the sample size of this study is small. The study was carried out with a limited number of respondents from the selected district, even though different methods were used for cross-checking. Thus, further studies are required to explore the patterns of pastoral seasonal migration, particularly with a larger sample size and broader areas.

About the authors

Chayot Gatdet is PhD candidate in Rural Development and Food Security at University of Gondar. He held his M.Sc. degree in Rural Livelihood and Food Security. His research areas are pastoralism, livelihood, food security, agricultural extension and sustainable development. The author has engaged in different Ethiopia research conferences. He has published nine journal articles and one book from 2021 to 2022.

Kibrom Adino is assistant professor of development studies. He graduated from Addis Ababa University. His research areas are migration, commercialization, impact evaluation, rural development, livelihood and gender and agriculture.

Tigist Petros is PhD candidate at University of Gondar. Her research areas are agricultural extension, food security, gender, environment and livelihood.

Acknowledgment

Thank to district administrator, respondents, enumerators and other participants.

Disclosure statement

The author affirmed that nope conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The availability of facts is restricted by the privacy.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adriansen, K. A., & Nielsen, T. T. (2002). Going where the grass is greener: On the study of pastoral mobility in Ferlo, Senegal. Human Ecology, 30(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015692730088

- Adugna, L. (2012). Trade liberization and change in poverty status in rural Ethiopia: What are the links? International Economic Journal, 26, 609–633.

- Alemseged, N., & Tamiru, W. (2014). Impacts of flooding on households’ settlement of rural Gambella. African Climate Policy Center.

- Ali, J. (2013). People to people diplomacy in the pastoral system: A case from Sudan and South Sudan. Abdalla Pastoralism Research, Policy and Practice, 3, 12.

- Altai Consulting. (2015). Irrigular migration between West Africa, North Africa and Medeterinean. Consulting for IOM.

- Amusan, L., Abegunde, O., & Akinyemi, E., T. (2017). Climate change, pastoral migration, resource governance and security: The Grazing Bill solution to farmer-herder conflict in Nigeria. Environmental Economics, 8(3), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.21511/ee.08(3).2017.04

- Andry, C. (2017). Pathways to resilience in pastoralist areas: A synthesis of research in the Horn of Africa. A Feinstein International Center Publication.

- Anna, D., & Christian, N. (2013). Nenets migration in the lanscape: Impacts of industrial development in Yamal Penisula. Research, Policy and Practice, 3, 15.

- Arsham, H. (2007). Sample size determination. Merrick School of Business, University of Baltimore, Charlesat Mount Royal.

- Awinia, C. S. (2020). The sociology of intra-African pastoralist migration: The case of Tanzania. Frontiers in Sociology, 5, 518797. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2020.518797

- Bailey, J. (2012). Gender dimensions of drought and pastoral mobility among the Maasai (Africa Portal Backgrounder No. 22).

- Bassett, T., & Turner, M. (2007). Sudden shift or migratory drift? FulBE herd movements to the Sudano-Guinean region of West Africa. Human Ecology, 35(1), 33–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-006-9067-4

- Becky, C., & Brigitte, R. (2016). Rapid fragility and migration assessment for Ethiopia: Rapid literature review. GSDRC, University of Birmingham.

- Befikadu, E., Z. (2012). Migration and urban livelihood: A quest for sustainability in Southern Ethiopia. Global Journal of Human-Society Science: Geography Geoscience, Environmental Science and Disaster Management.

- Belete, A., & Aynalem, T. (2017). A review on traditional livestock movement system (Godantu) in bale zone: An implication to utilization of natural resources. Journal of Veterinary Science and Research.

- Ben, W., & Michael, L. (2002). Tracking pastoralists migration: Lesson from Ethiopia Somali regional state. Human Organization, Society for Applied Anthropology, 61, 328–338.

- Biesta, G. (2010). Pragmatism and the philosophical foundations of mixed methods research. Sage Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research, 2, 95–118.

- Birhanu, Z., Birhanu, N., & Ambelu, A. (2015). Rapid appraisal of resilience to the effects of droughts in Borana Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Horn of Africa Resilience Innovation Lab (HoARILab).

- Buono, N., Di Lello, S., Gomarasca, M., Heine, C., Mason, S., Nori, M., Saavedra, R., & Van Troos, K. (2016). Pastoralism, the backbone of the world’s dry lands. Veterinan Sans Frontiers International.

- Central Statistical Agency (CSA). (2013). Population projection of Ethiopian populations for all regions at Woreda level from 2014-2017. Federal Demographic Republic of Ethiopia, Central Statistical Agency.

- Chepp, V., & Gray, C. (2014). Foundations and new directions. Cognitive Interviewing Methodology, 7–14.

- Clarisse, U., & Augustin, A. (2018). Perceived effects of transhumance practices on natural resources management in Southern Mali. Pastoralism: Research, Policy and Practices, 8, 8.

- Coalation of European Lobbies on Eastern African Pastoralism (CELEP). (2017). Recognizing the roles and the values of pastoralism and pastoralists (Policy Brief). Food and Agriculture Organization.

- Coppolillo, P. B. (2000). The landscape ecology of pastoral herding: Spatial analysis of land use and livestock production in East Africa. Human Ecology, 28(4), 527–560. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026435714109

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). A concise introduction to mixed methods research. SAGE Publications.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design (5th ed.). Sage.

- David, O. (2009). Pastoralists’ dropout study in Jijiga, Shinile and Fik zones of Somali region, Ethiopia. Save the children. Kenya Polytechnic College.

- Dawn, C., & Troy, S. (2015). Climate effects on nomadic pastoralist societies: Oman and Mangolia Retley-The modern climatic and social change: Social challenges to mobile pastoral livelihood. Forced Migration Review, (49).

- Devereux, S. (2006). Vulnerable livelihoods in Somali region, Ethiopia (IDS Research Report 57). Institute of Development Studies.

- Dinah, A. (2018). Assessing the fluxes and the impacts of drought induced migration of pastoral communities into urban areas: A case study of marsabit town, northern Kenya. Faculty of Geoinformation Science and Earth Observation [Master’s thesis]. University of Twente.

- Dwyer, J. M., & Istomin, V. K. (2008). Theories of nomadic movement: A new theoretical approach for understanding the movement decisions of Nenets and Komi Reindeer Herders. Human Ecology, 36(4), 521–533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-008-9169-2

- Economic Commission of Africa (ECA). (2017). New fringe pastoralism: Conflict & insecurity and development in the Horn of Africa and Sahel.

- Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO). (2018). Pastoralism in Africa dry land: Reducing risks, addressing vulnerability and enhancing resilience.

- François, P. (2007). Complex development-induced migration in the afar pastoral area (North-East Ethiopia). Paper prepared for the Migration and Refugee Movements in the Middle East and North Africa. The Forced Migration & Refugee Studies Program, The American University in Cairo, Egypt.

- Frankenberger, T., & Smith, L. C. (2015). Ethiopian pastoral areas: resilience improvement and market expansion (PRIME). Project impact evaluation. A baseline survey report. USAID.

- George, K., Bernard, K., & Abdi, Y. (2011). Effects of cattle rustling and households characteristics on migration decisions and herds size among pastoralists in Baringo district in Kenya. Pastoralism: Research, Policy and Practice, 1, 18.

- Getahun, T., Hassen, H., G/Maram, A., Admasu, D., Tadesse, L. B., Seyum, D., & Tessema, A. (2010). Pastoralism and land: Land tenure, administration and use in pastoral areas of Ethiopia. Ethiopian Pastoralism Forum.

- Gunvor, J. (2010). The environmental factors in migration dynamic: A overview of africa case studies. University of Oxford: International Migration Institute, James Martime 21st Century School.

- Haile, G. (2003). Pastoralism in Ethiopia, the Ethiopia Herald, April, 12, 2003.

- Hanne, K. (1999). Pastoral mobility as a response to climate variability in Africa dry lands. Geografisk Tidsskrift, 99(1), 1–10.

- Hein, H. (2007). Migration and development: A theoretical perspectives [Working paper]. Conference on Transhumance Development Toward North-South Perspectives, Center for Internation Research, Bielefela, Germany.

- Hussein, M. (2018). Exploring spatio-temporal processes of communal rangelands grabbings in Sudan. Pastoralism: Research, Policy and Practices, 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13570-018-0117-5

- Hussein, S., & Helen, Y. (2019). Transforming pastoralists mobility in West Darfur: Understanding continuity and change. A Fernstein International Center Publication.

- Ibrahim, S. S., Ozdeser, H., Cavusoglu, B., Shagali, A. A., & Shu’Aibu, M. (2020). Migration drivers, income inequality and rural attachment in deprived remote areas prone to cattle rustling in Nigeria. Migration and Development, 11(3), 958–973. https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2020.1848710

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). (2017). IOM launches migrations: The environment and climate change project in Namibia. International Migration Organization.

- Izumi, N. (2017). Agro-pastoral large-scale farmers in East Africa: A case study of migration and economic changes of the Sukuma in Tanzania. Nilo-Ethiopian Studies, 22, 55–66.

- Jebessa, T., & Zelalem, B. (2014). A literature review report on understanding the context of people transitioning out of pastoralism (TOPs) in Ethiopia. PRIME, Haramaya University.

- Jeremy, L., Rachel, S., Sarah, K., Matteo, C., Abdurehman, E., Deborah, M., & Christopher, O. (2016). Changes in the dry lands of East Africa: Case studies of pastoralists system in the region. Institute of development studies, University of Sussex.

- Jessica, H. (2008). Why do people migrate? A review of theoretical literature. maastrichit graduate school of governance. Munich Personal REPEc Archive (MPRA Paper 28197).

- Jon, H. (2014). Lands of the future: Transforming the pastoral lands and livelihood in eastern Africa (Working paper number 15). Max Plank Institute for Social Anthropology.

- Kuenga, N., Joanne, M., Rosemary, B., & Tashi, S. (2013). Transhumant and agro-pastoralism in Bhutan: Exploring contemporary plan and socio-cultural traditions. Pastoralism: Research, Policy and Practices, 3, 13.

- Liao, C., Morreale, J., S., Kassam, S., K., Sullivan, J., P., & Fei, D. (2014). Following the green: Coupled pastoral migration and vegetation dynamics in the Altay and Tianshan Mountains of Xinjiang, China. Applied Geography, 46, 61–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2013.10.010

- Linger, A. (2018). Temporary rural-rural migration, vulnerability of migrants at destination and it is outcomes on migrants households: Evidence from temporary migrants sending households in Quarit district, North western Ethiopia [doctoral dissertation]. Addis Ababa University.

- McCabe, T. J., Smith, M. N., Leslie, W. P., & Telligman, L. A. (2014). Livelihood diversification through migration among a pastoral people: Contrasting case studies of Maasai in Northern Tanzania. Human Organization, 73(4), 389–400. https://doi.org/10.17730/humo.73.4.vkr10nhr65g18400

- Mersha, T. G., & Tadesse, F., Y. (2019). Mapping of livestock movement routes in Afambo and Teru districts of Afar National Regional State Ethiopia. Spatial Information Research, 27(4), 433–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41324-019-00247-3

- Mohammed, T. (2015). The policy environment and critical constraints. Brief for GSDR. Arbaminch University.

- Nagabhatla, N., Cassidy-Neumiller, M., Francine, N., N., & Maatta, N. (2021). Water, conflicts and migration and the role of regional diplomacy: Lake Chad, Congo Basin, and the Mbororo pastoralist. Environmental Science & Policy, 122, 35–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.03.019

- Nathaniel, O. (2019). Locational analysis of seasonal migration of nomadic pastoralists in a part of northern Nigeria. Geagraphical Bulletin, 605, 5–23.

- Nejimu, B., & Hussein, M. (2016). Pastoralist and antenatal care services utilization in Dubti district, Afar, Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Pastoralism: Research, Policy and Practices, 6, 15.

- Nelson, E. L., Khan, S. A., Thorve, S., & Greenough, P. G. (2020). Modeling pastoralist movement in response to environmental variables and conflict in Somaliland: Combining agent-based modeling and geospatial data. PLoS One, 15(12), e0S244185. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244185

- Nori, M., & López-I-Gelats, F. (2020). Pastoral migrations and generational renewal in the Mediterranean. Economía Agraria y Recursos Naturales, 20(2), 95–118. https://doi.org/10.7201/earn.2020.02.05

- Nori, S., & Gemini, M. (2011). The common agricultural policy vis-a-vis European pastoralists: Principles and practices. Pastoralism: Research, Policy and Practice, 1(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/2041-7136-1-27

- Ono, C., & Ishikawa, M. (2020). Pastoralists’ herding strategies and camp selection in the local commons—A case study of pastoral societies in Mongolia. Land Journal, 9, 496. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9120496

- Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Johnson, R. B. (2006). The validity issue in mixed research. Research in the Schools, 13(1), 48–63.

- Oxfam (Oxford Committee for Famine). (2010). Pastoralism demographics, settlements and services provision in the Horn and east Africa. Transformation and opportunities. Oversees Development Institute.

- Oxfam (Oxford Committee for Famine). (2018). Ethiopian pastoralists communities affected by drought fight for their ancestral livelihood. A relief web report, informing humanitarians worldwide.

- Paolo, M., Thibaud, P., Saidou, M., Kenton, L., Victor, N., Vincent, N., Eran, R., Lan, G., & Barend, M. (2018). Cattle transhumance and agropastoral nomadic herding practices in Central Cameroon. BMC Veterinary Services.

- Pei, Q., & Zhang, D., D. (2014). Long-term relationship between climate change and nomadic migration in historical China. Ecology and Society, 19(2), 68. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-06528-190268

- Riley, E., Olengurumwa, O., & Olesangale, T. (2012). Urban pastoralists: A report on the demographics, standards of living, and employment conditions of migrant Maasai living in Dar es Salaam. LHRC and lIVES.

- Salzman, C. P. (2002). Pastoral nomads: Some general observations based on research in Iran. Journal of Anthropological Research, Summer, 2002, 58(2), 245–264.

- Samuel, G. (2016). Economic linkages between pastoralists and farmers in Ethiopia: Case study evidence from districts in Afar/Amhara and Oromia. Ethiopian Economics Association.

- Samuel, T. (2014). Changes in livestock mobility and grazing patterns among the Hamer in the Southeastern Ethiopia. African study monographs (pp. 99–112). Graduate School of Asian and African Studies, Kyoto University.

- Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2009). Research methods for business students. Pearson Education.

- Solomon, B. (2018). Formally recognizing pastoral community land right in Ethiopia. USAID/LAND.

- Stidsen, S. (2006). The migration world, 2006. IOW GIA.

- Sulieman, S. H., & Ahmed, M. G. A. (2017). Mapping the pastoral migratory patterns under land appropriation in East Sudan: The case of the Lahaween Ethnic Group. The Geographical Journal, 183(4), 386–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12175

- Suresh, A., & Gupta, J. S. (2011). Trends, determinants and constraints of temporary sheep migration in Rajasthan: An economic analysis. Agricultural Economic Resources Review, 24, 255–265.

- Wafula, M. W., Wasonga, V. O., Koech, K. O., & Kibet, S. (2022). Factors influencing migration and settlement of pastoralists in Nairobi City, Kenya. Pastoralism, 12, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13570-021-00204-6

- Wondwosen, M. (2017). The Nuer pastoralists-between large scale agriculture and villagisation: A case study of lare district in the Gambella region of Ethiopia. The Nordic Africa Institute.

- Yilebes, A. (2017). Livelihood strategies and diversification in the western tip pastoral areas of Ethiopia. Pastoralism: Research, Policy and Practice, 7, 9.

- Yonad. (2017). Factors for households exiting agropastoral livelihoods and an assessment of the urban livelihoods opportunities in Borena Zone, Ethiopia. Goal Ethiopia.

- Zhang, Q. (2012). The dilemma of conserving rangeland by means of development: Exploring ecological resettlement in a pastoral township of Inner Mongolia. Nomadic Peoples, 16(1), 88–115. Special Issue: Ecological narratives on grasslands in China: A people-centred view. https://doi.org/10.3167/np.2012.160108

- Zoe, C., & Helen, Y. (2012). Pastoralists in the new border land - Cross-border migration, conflict and peace building.