ABSTRACT

In Sweden, the local schoolboard has the ultimate responsibility for school quality and student knowledge development, and is held responsible if the expected outcomes are not met. Assisting the board is the superintendent who is the Chief Executive Officer. The aim of the study is to investigate the board’s relation to and expectations of the superintendent, and this article is a result of a national investigation in which all schoolboard chairs were surveyed. Two main questions were addressed: 1) what expectations does the local schoolboard have of the superintendent, both in general and in relation to student achievements and 2) which tasks are the superintendents expected to prioritise in carrying out their work? Data have been collected through a web-based survey using both structured and open-ended questions. The results show that the schoolboards’ strongest expectations placed on superintendents are to execute the leadership mission followed by managing the organisation within allocated budget frames. Responsibilities for academic outcomes have a lower ranking. Superintendents have many opportunities to influence the schoolboards’ decisions and thereby affect which goals they should prioritise in the local school organisation. The superintendent is an invisible ruler who in the chain of governance occupies the best position to influence both the schoolboard’s acting policy and the schools’ acting practice. By being aware of the existing asymmetric distribution of power, the schoolboard has the opportunity to exercise control over its official whose legal responsibility is to assist its members in their decision makings.

1. Introduction

Educational activities everywhere are subject to organisational arrangements, but who is ultimately responsible for these arrangements varies (Moos & Paulsen, Citation2014). In Sweden, each municipality constitutes the responsible authority and the municipality appoints a political schoolboard (SFS Citation2010:800, Ch.2 § 2). These schoolboards are accountable for the performance of their schools (Hooge & Honingh, Citation2014). The board members themselves are usually “spare time” politicians, i.e. individuals who fulfil those duties in addition to their regular work. Regardless of board members’ other obligations (“spare time” politicians, etc.), the expectations of what the schoolboard should achieve are high (Honingh et al., Citation2020).

The municipality hires a superintendent as an official with assignment to assist the school board as its Chief Executive Officer (CEO). As CEOs, superintendents play important roles in school organisation and are “key agent[s] in the chain of governance (), where policy, aims and objectives are transmitted from transnational, national and local levels to schools” (Paulsen et al., Citation2014, p. 812; Citation2016).

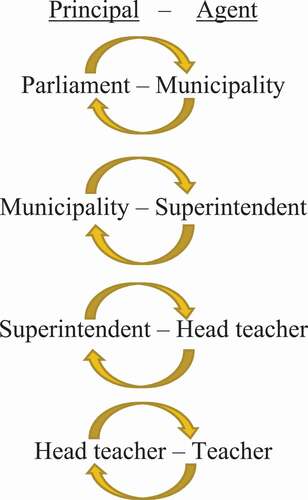

Figure 1. Chain of governance (SOU Citation2015:22)

The school’s main assignment is to deliver teaching and learning activities. The oversight for this rests in the chain of governance (SOU Citation2015:22). On the local level, schoolboards set prerequisites for the schools’ work policies, which means that the effects boards may have are indirect (Honingh et al., Citation2020). Accordingly, schoolboard governance can be seen as a precondition for those who are directly responsible for the teaching (Hooge & Honingh, Citation2014). Superintendents are charged with bridging the gap between national policy, schoolboard political management and the schools’ education activities, and are expected to ensure that education endeavours conform to the school’s regulatory goals and outcomes (Rapp, Citation2011; Rapp et al., Citation2017; Svedberg, Citation2014). This requires good collaboration between superintendents and schoolboards (Hendricks, Citation2013). As a link in the chain of governance, one of the superintendent’s main functions is to mediate between political and administrative managers and educational practitioners, especially school leaders (Paulsen et al., Citation2014), whereas in the school, the principal and teachers have a personal contact with the students and exert more direct leadership (Törnsén & Ärlestig, Citation2014). Hence, leadership is exerted on different levels in the chain of governance; each level has its own focus (Uljens & Ylimäki, Citation2015).

Today, there is a strong focus on student achievements as the most important indicator of educational quality. However, there is little evidence to be found on how schoolboards and educational quality are related, but studies that focus on the dynamics and relation between boards and school leaders do show that the relationship between schoolboards and the superintendent is essential to educational quality (Honingh et al., Citation2020).

Against this background, we note that the superintendent has a central function in the chain of governance and consequently in the management of the schools. Through the position in the chain, the superintendent can act as a “boundary spanner” (Coldren & Spillane, Citation2007), who connects the political level with the school level. In the present study, the aim is to investigate schoolboards’ relation to and expectations of the superintendent. A special interest concerns educational quality, which is represented by the focus on expectations to influence students’ achievement. The research questions guiding this study are:

What expectations does the local schoolboard have of the superintendent both in general and in relation to students’ achievement?

Which tasks are the superintendents expected to prioritise in their work?

To answer these questions, we conducted a survey of all chairs in Swedish municipal local schoolboards.

In the next section, we first review previous researches and then indicate their influences on this study. Afterwards, we discuss the principal-agent theory and the methodological considerations that have been addressed. In the final sections results of the study are reported and the main outcomes are discussed.

2. Previous research and influences on this study

Honingh et al. (Citation2020) note that there are differences between boards within countries as well as between countries and one cannot draw general conclusions or transfer ideas of working methods from one country to another. In Sweden, neither the role of nor the expectations of the superintendent by local schoolboards have been subject to extensive research. Likewise, internationally there are few surveys of local schoolboards’ expectations of their CEOs. Exceptions are the works of Moos and Paulsen (Citation2014) and Moos, Paulsen et al. (Citation2016) who note that the political expectations in Denmark, Norway and Sweden assume that “governance is almost exclusively a matter of management and of the assessment of resources and outcomes” (p. 299).

Johansson and Nihlfors (Citation2014) report that superintendents have identified the 10 most important expectations their schoolboards have. The top three are 1) understanding pedagogical leadership, 2) leading school principals and preschool heads in their pedagogical leadership, and 3) cooperating with the board and the local society. The researchers argue that an interesting question is the extent to which the superintendents’ “administrative work is influenced by local politicians” (p. 378) and they note that “most superintendents did not view politicians as interfering in their work and reported enjoying considerable autonomy” (p. 379).

Internationally, there is extensive research on leadership linked to learning (Leithwood & Seashore Louis, Citation2011; Seashore Louis, Citation2015; Seashore Louis et al., Citation2010). Several studies specifically focus on the superintendent (e.g. Björk, Browne-Ferrigno et al., Citation2014; Björk, Johansson et al., Citation2014; Pyhältö et al., Citation2010; Risku et al., Citation2014), and likewise internationally discussions about local schoolboards and their CEOs are ongoing. For example, Fusarelli (Citation2006) notes that the “superintendent and schoolboard must work together to improve schools and student academic performance” (p. 44). Also, Copich (Citation2013) argues that the “board’s role is extremely important in taking the lead for positive change”. Simultaneously, the superintendent is charged with interpreting board guidance and putting goals into action. Furthermore, Copich argues (with reference to Carver, Citation1997; Eadie, Citation2005; McAdams, Citation2006; Smoley, Citation1999) that “a strong board and superintendent relationship is a crucial component of a successful school district reaching organisational goals” (p. 6). Addi-Raccah (Citation2015) considers the superintendent as the link between the school principal and the local education authorities, e.g. when resources are needed. Rorrer et al. (Citation2008) writes: “Districts are vital institutional actors in systemic educational reform” (p. 308), and Huber (Citation2011) describes the division of responsibility between a municipal council (political matters) and a governing body (educational matters).

Clearly, the connection between the schoolboard and the superintendent is of great importance for successful local school development. To get a better understanding of how such a connection can affect outcomes we turn to theoretical perspectives connected to the schoolboard, the superintendent and the leadership duty.

3. The schoolboard, the superintendent and the principal – agent theory

Organisational systems can simultaneously be both loosely and tightly coupled (Boyd & Crowson, Citation2002; Fuzarelli, Citation2002; Paulsen & Hoyer, Citation2016). In the school organisation, some administrative parts can be tightly coupled, e.g. school bus schedules, while ties between decision, implementation and teaching are more loosely coupled (Meyer, Citation2002; Weick, Citation1982). Communication within the chain of governance is often unclear and does not facilitate goal fulfilment (SOU Citation2015:22). This is confirmed by Johanson et al. (Citation2016) who note “a lack of confidence between different actors and that feedback on work that is functioning well is rare for teachers and school leaders” (p. 140). Even Berg (Citation1992) questions links in the chain of governance and argues that the school system is a prime example of a “loosely connected institution” (Gamoran & Dreeben, Citation1986; Horne, Citation1992; Weick, Citation1976). These weak connections are shown in the following principal-agent model () in which public education is viewed as a series of relationships (Ferris, Citation1992).

In the principal-agent model, power is asymmetrically distributed: the agent is often better informed than the principal and it cannot be taken for granted that the agent always acts in accordance with the principal’s interest (Ferris, Citation1992; Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). In this theory two assumptions are central: 1) goal conflicts exist between the principal and the agent and 2) there is informational asymmetry (Wohlstetter et al., Citation2008). According to this framework, relations in the chain of governance can be viewed as a series of contractual relationships or “webs of contracts” (Wohlstetter et al., Citation2008) in which contracts are often implied and involve different levels of government.

Moos, Paulsen et al. (Citation2016) argue that local schoolboards “seem to cast themselves in the principal role, setting direction and producing aims, and the superintendents in the agent´s role, carrying out the policies”. Furthermore, superintendents “report that they are very autonomous acting more like policymakers than ‘implementers’, as they can influence the decisions of the schoolboard. This is because they have … the power of implementation and are at the same time the most important channel of information to the board … relations between the professional school level and the political level are mediated through the administration and its CEO” (pp. 299–300).

The present paper is about expectations placed upon superintendents especially in terms of influencing students’ results. Using the principal-agent theory we can deepen the understanding of the factors that lie behind expectations of the superintendent as well as better understand the superintendent’s own priorities and opportunities.

4. Methodology

This is a quantitative case study (Stake, Citation1998) in which data has been collected through a web-based survey (SurveyMonkey), using both structured and open-ended questions. Described below are 1) the selection procedures for respondents, 2) the design and investigatory instruments construction, 3) the data collection process, 4) the study’s ethical considerations, and 5) the method by which the empirical material has been processed and analysed.

4.1. Participants and procedure

The target group for the investigation were chairs (Honingh et al., Citation2020, p. 7) in Swedish municipal schoolboards, which are responsible for elementary schools (in total 290 municipalities). In the survey all chairs were questioned and undertaking a complete survey of chairs gave greater reliability and greater confidence in generalising results.

In total 290 questionnaires were distributed, and after two reminders, 264 chairs responded (91%). Thereafter, a missing data analysis was conducted that showed two types of missing data causes: 1) some participants were sent the same questionnaire twice and 2) some participants did not complete the questionnaire. Although no consensus regarding an acceptable percentage of missing data exists, we used 5% as the cut-off point as suggested by Schafer (Citation1999). According to Schafer (Citation1999) a missing rate of 5% or less is inconsequential. In this study mean substitution was used when the missing data were less than a predetermined cut-off rate (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2012), and cases were dropped if the missing data were more than the 5% cut-off rate (Schafer, Citation1999). As a result, 102 questionnaires were excluded, leaving 162 questionnaires for the statistical analysis. Although missing data analyses were carried out in order to obtain information that, as far as possible, represents Swedish local schoolboards’ expectations, the results should nevertheless be interpreted with caution.

These 162 correspond to 61% of the total 290 municipalities. The gender breakdown was 42% (68) women and 58% (94) men. Grouped by age intervals, the age group 60 years and up was the largest, with 37% of respondents. Approximately 51% of the respondents worked in municipalities with less than 15,000 inhabitants, 29% in a municipality with more than 15,000 but less than 40,000 inhabitants and 20% in municipalities with more than 40,000 inhabitants.

Although, as demographic attributes, gender/age diversity of the board of directors and management styles are topics that have been discussed in the literature, there is a lack of consensus among scholars. Several studies showed that women have more democratic, participative and collaborative styles of leading (e.g. Cheung & Halpern, Citation2010), but others did not find significant gender differences (e.g. Pavlovic, Citation2014). In a meta-analytic study on the relative effectiveness of women and men who occupy leadership and managerial roles, Eagly et al. (Citation1995) showed that male and female leaders were equally effective. However, researchers have found that, regarding the congruence of leadership roles and gender, men were more effective in roles that were defined in more masculine terms and women were more effective in roles that were defined in less masculine terms. Similarly, it has been argued that older managers were consulted more widely and favoured more participation in contrast to younger managers (Oshagbemi, Citation2004). On the other hand, there are also studies revealing no significant age/gender differences in using transformational, transactional and passive-avoidance leadership styles (e.g. Mushtaq & Akhtar, Citation2014).

4.2. The design and research quality of the survey

A questionnaire was created on the website host Survey Monkey and consisted of a series of questions. The questions were inspired, among other factors, by the questionnaire used by Moos, Nihlfors et al. (Citation2016). They studied the public education governance in the four Nordic countries: Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. Their study aimed to explore the ways in which influences, decisions and ideas are taken from one level to other levels in the public education sector and how they are interpreted and translated.

The questionnaire consisted of four parts and a total of 76 questions, including the background questions. Respondents answered the questions using a 4 or 5 point Likert-type scale, with 1 meaning “did not agree at all” and 5 meaning “agree totally”. One question allowed for open-ended responses.

The first part consisted of six background questions about the participants’ municipality, age, gender, party affiliation, educational background and the characterisation of their municipality. The second part consisted of 31 questions and concerned the board’s activities and the chair´s role. Questions dealt with types of issues on the agenda, influences over the board’s decisions and the chair’s main information source. The third part contained 16 questions about responsibility for and impact on student results. The goal of these questions was to identify persons/groups having the greatest responsibility and influence on student achievements. The fourth part consisted of 23 questions concerning the superintendent. It addressed questions about communication quality, assessment of competences, management, most important assignments, evaluation, reason for criticism and termination and the level of confidence in the superintendent.

Three questions dealing with the chair’s perception of communication with the superintendent and eleven questions with assessment of the superintendent’s competencies were analysed through a Cronbach’s Alpha reliability analysis. The result for respective dimensions was calculated as α = 0.83 and α = 0.88 and thus shows the instrument worked well in the context and exhibits high internal consistency.

Measures to minimise drop-out were taken, such as creating a simple but overall attractive design and endeavouring to construct clear, well-formulated instructions. The front of the questionnaire gave clear instructions, estimated response time, assurance that answers would be treated confidentially and the deadline for submission.

4.3. Data collection and administration

The web-based inquiry was created using the software programme SurveyMonkey (2018). Data collection was ongoing during the weeks 21 to 27 of 2018. The questionnaire, taking approximately 15 minutes to answer, was sent to the participants through their email addresses. Two reminders were sent to all respondents.

4.4. Research ethics

The Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet, Citation2017) has set guidelines for “good research practice”. Accordingly, the study adhered to those ethical principles in 1) information requirements – all participants were informed about the study’s purpose by email, 2) consent agreements – all participants were able to decide whether to participate and 3) confidentiality – no answers could be associated with a single person in the presentation of results. Participation was voluntary and at any point in the study the respondent was at liberty to decline to answer and/or participate.

4.5. Data processing/analysis

Data were retrieved from Survey Monkey and analysed using IBM Statistics Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS v25). In the first step, a missing data analysis was performed and then the descriptive statistics were used to describe the participant’s answer. Separate one-way ANOVA was conducted to analyse the effects of gender, age, size of municipality, communication with superintendents and judgement of the superintendents’ competences. The open responses (the qualitative data) were subjected to a thematic analysis. Two authors coded the data separately, and after several readings and discussions between the authors, three main themes emerged (inter-rater reliability, Goodwin & Goodwin, Citation1984) (see ).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for communication between the chair and the superintendent

Table 3. Superintendents’ most important assignments

5. Findings

The study’s results reveal that the chairs have great confidence in their superintendents with 73% replying “very good confidence” and 22% “good confidence”. Almost all said they obtain their main knowledge about municipal school activity from the superintendent. The chairs feel that the boards’ expectations are clearly communicated to the superintendents. In 63% of the municipalities, the superintendent receives written instruction from the board, and in 51% the instruction comes from the municipal management. Hence, many superintendents are managed with instructions from more than one level in the chain of governance. Many are governed by oral instructions, though some superintendents have neither written nor oral instructions. A remarkable 95% say it is very unusual for the superintendent’s work to be evaluated and about the same number (just over 94%) answer that no written guidance exists for such evaluations.

The chairs assert that they themselves have the greatest influence on the boards’ decisions. At the same time, they say that the superintendent is the one that, after the chair, has the most influence over political decisions. Indeed, the superintendent’s influence over political decisions is greater than either the board’s working committee or the municipal management. It is from the superintendent that more than 98% of the chairs obtain their main knowledge about municipal school activity.

One-way ANOVA-result, when it comes to gender, age and size of municipality, showed no significant differences in communication between the chair and the superintendent regarding expectations and to what extent these expectations were fulfilled (see ). No such differences existed in the judgement of the superintendent’s competencies (p > 0.05 n.s.).

The study’s focus is on the schoolboard’s expectations of the superintendent, which is presented under two headings: 1) expectations regarding influencing school and student results and 2) expectations regarding prioritisation of duties. The section concludes with a summary of the results.

5.1. Expectations regarding influencing school and student results

The chair is responsible for setting the agenda, but it is the superintendent who suggests its content and hence has an immediate influence on the political agenda. Given eleven alternative responses (scale 1–5), the respondents indicated that the most common agenda item was information from the administration (3.92), next were items about finances (3.77), in third place questions about general quality issues (3.38) and in fourth place questions about student results (2.91). Questions about student results received almost the same value as “decisions about evaluations” (2.80) and “questions about school organisation” (2.80).

The schoolboard receives information about student results preferably from the school level, to a lesser extent from the classroom level and to an even smaller extent from the individual level. The chairs state that responsibility for student results lies first with the principals, then the teachers, and thirdly with the board along with the superintendent. As to which group has greatest influence over student results, the picture is slightly different. Among the 14 response alternatives, the teachers were ranked as number one, followed by the head teachers, then parents in third place, the superintendent in fourth place and, trailing behind, the boards’ working committees ().

Table 2. Superintendent and student results

5.2. Expectations regarding prioritisation of duties

In an open-ended question the chairs were urged to specify the three most important duties of superintendents, and 153 respondents answered that question, with 152 respondents listing the two most important tasks and 146 respondents listing the three most important tasks. In total, the respondents gave 451 answers to what they considered to be the superintendents’ most important tasks.

When the answers were categorised and added up (), it was clear that the superintendents’ most important task was judged to be executing their leadership mission. Overall 111 responses (25%) could be related to the category “leadership”. Examples of responses categorised in this group are “leadership, lead the administration, steer all principals towards our objectives”. The superintendents’ second most important task was perceived as managing the educational tasks within given budget frames (63 answers, 14%). Words associated with this category were “financial responsibility, allocate budget and control, keep track of finances”. The third most important task was being responsible for student results (47 responses, 10%) and this was expressed by such words as “improve the results, goal fulfilment and student results”. In addition to the three categories listed, the further 230 answers could be classified under a number of different categories such as school development, quality work, working environment, recruitment etc. Answers under such categories are reported “other”. The result is summarised in .

Concerning how the leadership task is ranked in comparison to other tasks, the respondents had to rank five alternatives to the question of what could lead to a criticism of the superintendent. The alternatives were 1) exceed allocated budget, 2) unclear leadership, 3) not loyal towards the board, 4) poor student results and 5) other. The chairs also had to answer the question about what factors could lead to the termination of the superintendent. Both questions had the same answer alternatives. The result is summarised in .

Table 4. Superintendent risks being criticised or dismissed

Findings show the superintendent can be criticised if leadership is unclear, if activities do not remain within allocated budget frames, and if the superintendent is not loyal to the political board. Least risky for criticism is weak pupil results. Looking at actions that can lead to termination, the rankings are slightly different. Here, disloyalty is number one, followed by unclear leadership and not keeping activities within budget frames. The least risky aspect is sustaining poor student results. To summarise, unclear leadership together with exceeding budget frames are factors most risky for incurring criticism while weak student results are least risky for being criticised. The riskiest factors leading to termination are disloyalty, unclear leadership or exceeding budget frames. Quality issues in terms of weak student results are least risky even here. The chairs do not expect the superintendent’s primary focus to be student knowledge development.

5.3. Discussion

Each school is a part of a system regulated by national regulations and it is the local political boards’ responsibility to guarantee a training of the highest level. Local schoolboards set directions, produce aims, and the superintendent assists the board. The superintendent’s task is thus to assist the schoolboard and this study focusses on the board’s expectations of its official.

The chairs expressed great confidence in their superintendents and stipulated the expectations they have of them. In what way and to what extent the superintendents fulfil these expectations cannot be discerned because no evaluations of outcomes are done. Despite being the school’s main assignment, chairs seem not to expect the superintendent to put student knowledge development highest on the agenda. Instead, expectations placed on the superintendent are first to lead the local school organisation and secondly not to exceed budget. Ranked third place (with significantly lower numbers) was influencing student results and seemingly there is little risk that a superintendent would be criticised or lose the position if student knowledge and development are not prioritised. When discussing responsibility for student results and school performance the chairs consider principals and teachers to be those with the main responsibility, teachers being the group that can most affect the results. Surprisingly the chairs place parents in third place even though existing research evidence argues that family background is hugely important for school performance (Hattie, Citation2009).

Honingh et al. (Citation2020) argue that schoolboards set prerequisites for the schools’ work policies and Hooge and Honingh (Citation2014) note that the board’s governance is a precondition for those who are directly responsible for the teaching. Honingh et al. (Citation2020) further state that the relationship between schoolboards and the superintendent is essential to educational quality. The present study shows that the relationship between the chair and the superintendent – shown by the confidence accorded – is positive. Schoolboard chairs consider themselves to have greatest influence on the boards’ decisions, although almost all obtain their main information from the superintendent. It means that the boards’ expectations of the superintendents can be derived from the superintendents themselves. Consequently, a schoolboard’s prerequisites for the schools’ work policies may be a result of the superintendent’s impact on the board. The possibilities of officials to influence the political level is supported by Moos, Paulsen et al. (Citation2016) who claim: ”[…] however, the superintendents argue that they can influence the schoolboard’s decisions and therefore consider themselves more as policymakers than implementers” (p. 299). To summarise: the present study reveals that the superintendent has extensive opportunities to influence the elected representatives and thereby impact the politicians’ work and can thus affect the board’s expectations of the superintendent. At the same time the superintendent, as the head of the principals, can also influence work in local schools.

In this section, some of the study’s main results have been presented and problematised. In the next section this discussion is deepened by being contrasted with the principal-agent theory.

6. Implications

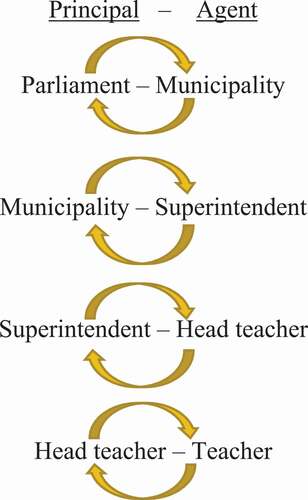

Moos, Paulsen et al. (Citation2016) claim local schoolboards “seem to cast themselves in the principal role, setting direction and producing aims and the superintendents in the agent’s role, carrying out the policies” (p. 299). This ideal typical reasoning is displayed in .

However, by using principal-agent theory, which involves goal conflicts, weaknesses in the governance can become visible, given that the agent often is better informed than the principal and hence shows existing informational asymmetry. Accordingly, a picture that differs from the ideal typical model depicted above can be detected (see ).

The relationship between the schoolboard (the principal) and the superintendent (the agent) can be viewed as a series of “webs of contracts” between levels in the governance chain (Wohlstetter et al., Citation2008). The present study showed that this chain can be either tight or loosely coupled and that there exists an asymmetric distribution of power (Ferris, Citation1992; Wohlstetter et al., Citation2008).

Through the opportunities to affect the chair, there exists a tight coupling between the superintendent and the board and through this connection the superintendent can act in the political arena. However, the study shows no similar tight connection in the other direction (from the board to the superintendent). As principal to the head teachers, the superintendent can influence the performances of the local school leaders and thereby can also influence priorities in local schools. Accordingly, the superintendent can have influence both upwards and downwards in the organisation (Paulsen et al., Citation2016).

In this manner, the superintendent’s (the agent’s) position affords access to a web of contracts both upwards and downwards in the chain of governance. At the same time, the proximity to and trust from the principal (the chair) provide opportunities to influence both the political agenda and the content of the political decisions. Furthermore, it can also be assumed that the agent – through the position in the chain – has insight into power struggles, compromises and expectations on the political level as well as the local school’s teaching and learning. The agent’s position thus provides an information advantage (information asymmetry) that the agent can use in the transformer/mediator role. The position in the chain of governance gives the agents (the superintendents) the opportunity to act as “boundary spanners” connecting the above level – influenced by themselves – with the level below. It means that the agent (the superintendent) has good opportunities to strengthen the loosely coupled chain of governance, especially with regards to the connection between the local schoolboard and the head teacher.

7. Conclusions

The results of the present study reveal that the strongest expectation placed on the CEO is to execute the leadership mission. This was followed by managing the local school organisation within allocated budget frames. Influencing student results has a lower ranking on the lists of expectations but the superintendent has significant opportunities to influence the schoolboard’s work and decisions.

Finally, the study’s main result and its unexpected finding – superintendents themselves can influence the board’s expectations of them and thereby affect what they shall prioritise in the local school organisation – show that the superintendent is an invisible ruler who acts in a non-visible free space with opportunities to influence both the political content and its implementation. That politic is affected by different invisible interests is not unusual and is also described in the literature (e.g. Webb Yackee, Citation2015). What may stand out in this study is that a politically appointed (employed) CEO is given a great possibility to influence both the political agenda and decisions as well as the implementation. The superintendent can act and mediate in parallel on both the local arena for formulation and the arena for realisation. However, the superintendent’s invisible influence over the way the boards act and make decisions appears in line with the rationalistic theory. This unnoticeable influence that imperceptibly affects principals’ (schoolboards’) decisions can be termed as “fraudulent rationalism”.

The new knowledge given with the study is important for the schoolboards’ work. Especially significant is the knowledge of the superintendent’s role as an invisible ruler. By being aware of the asymmetric distribution of power, the schoolboard is given the possibility of taking command of its own expectations of (and thus requirements on) the official whose legal duty is to assist the schoolboard in its decision-making. This knowledge provides valuable information about what can be done to strengthen connections in the governance chain.

7.1. Limitations of the study

This study is about the chair’s expectations of the superintendent and it provides new knowledge about the relation between these two from the chair’s perspective. One can assume that the survey responses would have differed if other board members also had been asked. However, the assumption is that the chair represents the main political group. A chair with divergent opinions is unlikely to be tolerated by the leading group, and thus the assumption that the chair’s answers should be representative of the political majority in the municipality.

The study focuses on the chairs’ expectations that the superintendents’ leadership is connected to taking responsibility for student learning. Exactly where this responsibility lies is somewhat problematic since the board has the ultimate responsibility for student achievements. However, student learning is the schools’ main mission (National Agency for Education, Citation2011) and a reasonable supposition is that the board’s CEO has a responsibility for the student knowledge development.

The position of the superintendent was regulated in the Education Act (Citation2010:800) in January 2019. Accordingly, this post was not legally regulated 2018 when this study was conducted. Even if the regulation in some sense has made the superintendent more explicit, it has not affected the superintendent’s position as an invisible ruler with opportunities to influence both the political content and its implementation in schools.

In this study a quantitative method was employed with the aim to get a general knowledge about Swedish chairs’ expectations of the superintendent. A questionnaire has limitations compared to e.g. interviews. In a meeting, the researcher can continue to ask until the question is “saturated”. However, this quantitative investigation gives a broad base for future, more qualitatively oriented, research which can develop a deeper understanding of what expectations the local school board has of its superintendent.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Addi-Raccah, A. (2015). School principals´ role in the interplay between the superintendents and the local education authorities. Journal of Educational Administration, 53(2), 287–306. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-10-2012-0107

- Berg, G. (1992). Statlig styrning och kommunal skoladministration. En rapport från SLAV-projektet [State Governance and municipal school administration. A report from the SLAV-project]. Uppsala universitet: Pedagogiska institutionen.

- Björk, L. G., Browne-Ferrigno, T., & Kowalski, T. J. (2014). The superintendent and educational reform in the United States of America. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 13(4), 444–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2014.945656

- Björk, L. G., Johansson, O., & Bredeson, P. (2014). International comparison of the influence of educational reform on superintendent leadership. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 13(49), 466–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2014.945658

- Boyd, W. L., & Crowson, R. L. (2002). The guest for a new hierarchy in education: From loose coupling back to tight? Journal of Educational Administration, 40(6), 521–534. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230210446018

- Carver, J. (1997). Boards that make a difference: A new design for leadership in nonprofit and public organizations (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Cheung, F. M., & Halpern, D. F. (2010). Women at the top: Powerful leaders define success as work + family in a culture of gender. American Psychologist, 65(3), 182–193. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017309

- Coldren, A., & Spillane, J. (2007). Making connections to teaching practice: The role of boundary practices in instructional leadership. Educational Policy, 21(2), 369–393. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904805284121

- Copich, C. B. (2013). The role of the local schoolboard in improving student learning. EDAD 9550 Symposium of School Leadership. University of Nebraska at Omaha https://www.unomaha.edu/college-of-education/moec/_files/docs/publications/edad9550-copich-research-spring2013.pdf

- Eadie, D. C. (2005). Five habits of high-impact schoolboards. Rowman & Littlefield Education.

- Eagly, A. H., Karau, S. J., & Makhijani, M. G. (1995). Gender and the effectiveness of leaders: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 117(1), 125–145. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.125

- Ferris, J. M. (1992). School-based decision making: A principal-agent perspective. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 14(4), 333–346. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737014004333

- Fusarelli, B. C. (2006). Schoolboards and superintendent relations. Issues of continuity, conflict, and community. Journal of Cases in Educational Leadership, 9(1), 44–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555458905285011

- Fuzarelli, L. D. (2002). Tightly coupled policy in loosely coupled systems: Institutional capacity and organizational change. Journal of Educational Administration, 40(6), 561–575. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230210446045

- Gamoran, A., & Dreeben, R. (1986). Coupling and control in educational organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 31(4), 612–632. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392966

- Goodwin, L. D., & Goodwin, W. L. (1984). Are validity and reliability “relevant“ in qualitative evaluation research? Evaluation & the Health Professions, 7(4), 413–426. https://doi.org/10.1177/016327878400700403

- Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

- Hendricks, S. (2013). Evaluating the superintendent: The role of the schoolboard. NCPEA Education Leadership Review, 14(3), 62–72. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1105391.pdf

- Honingh, M., Ruiter, M., & van Thiel, S. (2020). Are school boards and educational quality related? Results of an international literature review. Educational Review, 72(2), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2018.1487387

- Hooge, E., & Honingh, M. (2014). Are schoolboards aware of the educational quality of their schools? Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 42(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143213510509

- Horne, S. (1992). Organisation and change within educational systems: Some implications of a loose-coupling model. Educational Management and Administration, 20(2), 88–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/174114329202000204

- Huber, S. G. (2011). School governance in Switzerland: Tensions between new roles and old traditions. Educational Management Administration, 39(4), 469–485. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143211405349

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

- Johanson, O., Nihlfors, E., Jervik Steen, L., & Karlsson, S. (2016). Superintendents in Sweden: Structures, cultural relations and leadership. In L. Moos, E. Nihlfors, & J. M. Paulsen (Eds.), Nordic superintendents: Agents in a broken chain (pp. 139–173). Springer.

- Johansson, O., & Nihlfors, E. (2014). The Swedish superintendent in the policy stream. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 13(4), 362–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2014.945652

- Leithwood, K., & Seashore Louis, K. (2011). Linking leadership to student learning. Jossey Bass.

- McAdams, D. R. (2006). What schoolboards can do: Reform governance for urban schools. Teachers College Press.

- Meyer, H.-D. (2002). From “loose coupling” to “tight management”? Making sense of the changing landscape in management and organization theory. Journal of Educational Administration, 40(6), 515–520. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230210454992

- Moos, L., & Paulsen, J. M. (2014). Comparing Nordic educational governance. In L. Moos & J. M. Paulsen (Eds.), School boards in the governance process (pp. 1–10). Springer.

- Moos, L., Nihlfors, E., & Paulsen, J. M. (2016). Directions for our investigation of the chain of governance and the agents. In L. Moos, E. Nihlfors, & J. M. Paulsen (Eds.), Nordic superintendents: Agents in a broken chain (pp. 1–21). Springer.

- Moos, L., Paulsen, J. M., Johansson, O., & Risku, M. (2016). Governmentality through translation and sense-making. In L. Moos, E. Nihlfors, & J. M. Paulsen (Eds.), Nordic superintendents: Agents in a broken chain (pp. 287–310). Springer.

- Mushtaq, S., & Akhtar, M. S. (2014). A study to investigate the effect of demographic variables on leadership styles used by department heads in universities. Journal of Quality and Technology Management, 10(1), 17–33.

- National Agency for Education. (2011). Läroplan för grundskolan, förskoleklassen och fritidshemmet (revised 2016) [Curriculum for the elementary school, pre-school class and leisure centre]. Skolverket.

- Oshagbemi, T. (2004). Age influences on the leadership styles and behavior of managers. Employee Relations, 26(1), 14–29. https://doi.org/10.1108/01425450410506878

- Paulsen, J. M., Nihlfors, E., Brinkkjaer, U., & Risku, M. (2016). Superintendent leadership in hierarchy and network. In L. Moos, E. Nihlfors, & J. M. Paulsen (Eds.), Nordic superintendents: Agents in a broken chain (pp. 207–231). Springer.

- Paulsen, J. M., & Hoyer, H. C. (2016). External control and professional trust in Norwegian school governing: Synthesis from a Nordic research project. Nordic Studies in Education, 36(2), 86–102. https://doi.org/10.18261/.1891-5949-2016-02-02

- Paulsen, J. M., Johansson, O., Moos, L., Nihlfors, E., & Risku, M. (2014). Superintendent leadership under shifting governance regimes. International Journal of Educational Management, 28(7), 812–822. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-07-2013-0103

- Pavlovic, N. (2014). Effects of gender differences on leadership styles through the impact on school environment. Studia Edukacyjne, 31, 305–322. https://doi.org/10.14746/se.2014.31.17

- Pyhältö, K., Soini, T., & Pietarinen, J. (2010). A systemic perspective oh school reform. Principals´ and chief education officers´ perspectives on school development. Journal of Educational Administration, 49(1), 46–61. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578231111102054

- Rapp, S. (2011). The director of education as a leader of pedagogical issues: A study of leadership in municipal educational sector activities. School Leadership and Management, 31(5), 471–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2011.587405

- Rapp, S., Segolsson, M., & Aktas, V. (2017). The director of education and research-based education. Exploring the tension between policy and what directors actually report. International Journal of Research and Education, 2(4), 1–12. http://onlinejournal.org.uk/index.php/ijre/issue/view/30/showToc

- Risku, M., Kanervio, P., & Björk, L. G. (2014). Finnish superintendents: Leading in a changing education policy context. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 13(4), 383–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2014.945653

- Rorrer, A. K., Skrla, L., & Scheurich, J. J. (2008). Districts as institutional actors in educational reform. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(3), 307–358. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X08318962

- Schafer, J. L. (1999). Multiple imputation: A primer. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 8(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1191/096228099671525676

- Seashore Louis, K. (2015). Linking leadership to learning: State, district and local effects. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 2015(3), 30321. https://doi.org/10.3402/nstep.v1.30321

- Seashore Louis, K., Leithwood, K., Wahlstrom, K. L., & Anderson, S. E. (2010). Learning from leadership project – Investigating the links to improved student learning. The Wallace Foundation.

- SFS. (2010:800). Skollagen [The Swedish Education Act]. Utbildningsdepartementet.

- Smoley, E. R. (1999). Effective schoolboards: Strategies for improving board performance (1st ed.). Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- SOU. (2015:22). Rektorn och styrkedjan. Betänkande av Utredningen om rektorernas arbetssituation inom skolväsendet [The principal and the chain of governance. Report on the working situation for principals in the educational system]. Fritzes.

- Stake, R. E. (1998). Case Studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Strategies of qualitative inquiry (pp. 86–109). SAGE Publications.

- Svedberg, L. (2014). Rektorn, skolchefen och resultaten. Mellan profession och politik [Principal, the superintendent and the results. Between profession and policy]. Gleerups.

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2012). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). MA Pearson.

- Törnsén, M., & Ärlestig, H. (2014). Pedagogiskt ledarskap, mål, process och resultat [Pedagogical leadership, aim, process and results]. In J. Höög & O. Johansson (Eds.), Framgångsrika skolor - mer om struktur, kultur och ledarskap [Successful schools – More about structure, culture and leadership] (pp. 77–99). Studentlitteratur.

- Uljens, M., & Ylimäki, R. (2015). Theory of educational leadership, Didaktik and curriculum studies – A non-affirmative and discursive approach ( No 38). In Educational leadership – theory, research and school development. Report from the Faculty of Education and Welfare Studies, Åbo Akademi University.

- Vetenskapsrådet. (2017). God forskningssed [Good research practice]. Vetenskapsrådet. https://www.vr.se/download/18.2412c5311624176023d25b05/1529480532631/God-forskningssed_VR_2017.pdf

- Webb Yackee, S. (2015). Invisible (and visible) lobbying: The case of state regulatory policymaking. State Politics & Policy Quarterly 2015, 15(3), 322–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532440015588148

- Weick, K. E. (1976). Educational organizations as loosely coupled systems. Administrative Science Quarterly, 21(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/2391875

- Weick, K. E. (1982). Administering education in loosely coupled schools. Phi Delta Kappan, 63(10), 673–676.

- Wohlstetter, P., Datnow, A., & Park, V. (2008). Creating a system for data-driven decision-making: Applying the principal-agent framework. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 19(3), 239–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243450802246376