ABSTRACT

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the immediate and longer-term effects of school closures and ongoing interruptions on children’s learning have been a source of considerable apprehension to many. In an attempt to anticipate and mitigate the effect of school closures, researchers and policymakers have turned to the learning loss literature, research that estimates the effect of summer holidays on academic achievement. However, school closures due to COVID-19 have taken place under very different conditions, making the utility of such a literature debatable. Instead, this study is based on a rapid evidence assessment of research on learning disruption – extended and unplanned periods of school closure following unprecedented events, such as SARs or weather-related events. We argue that this literature provides clearer evidence on what helps children return to learning under similar conditions, and in this sense has more direct relevance for schools after COVID-19. A narrative synthesis of key recommendations is presented. Key findings are as follows: (i) that school leaders’ local knowledge is pivotal in leading a return to school, (ii) the curriculum needs to be responsive to children’s needs and (iii) that schools are essential in supporting the mental health of students. A discussion of the applicability and utility of these findings is provided in light of emerging evidence of challenges faced by schools in the context of an ongoing global pandemic and the disruption to education it continues to create.

COVID-19 has had an unprecedented impact on education in many countries. In spring 2020, at the height of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, over 1.5 billion young people were impacted by the closure of schools and universities (UNESCO, Citation2020a). In November 2020, UNESCO (Citation2020a) estimated that 12.8% of enrolled learners worldwide were still out of school due to closures. This estimation does not account for the many nations that have partially reopened schools or moved to online learning; and pupils who are temporarily self-isolating or off sick. This level of disruption to education is unprecedented.

To date, the long-term effects on children’s academic achievement and social and emotional well-being are unclear. There is evidence to suggest that academic achievement has been impacted (Blainey & Hannay, Citation2021; Education Endowment Foundation, Citation2021), however, although losses equated to less than two months and reduced over time. Other researchers have found that the impact is not as detrimental as was predicted earlier in the pandemic (Johnson et al., Citation2021). What is clear, however, is that home learning has been challenging and children of higher-income parents are more likely to have better access to technology and spend more time on home learning (Andrew et al., Citation2020). That being said the major disruption has led to some innovation with upskilling of education personnel in digital pedagogies (Moss et al., Citation2021) and increased levels of contact between school and home (UNESCO, Citation2020b).

As the education community grapples with how best to return to “normality” in the context of an ongoing global pandemic, two contrasting literatures offer possible sources of relevant evidence: a literature on learning loss, based on quantifying the probable effects of time out from school; and a literature on learning disruption, based on studies of how schools have responded when faced with unplanned and extended periods of closure. The relevance of the answers that these two different literatures provide is the subject of this paper. We argue that the methodology used to quantify learning losses, while attractive to policymakers seeking to allocate funds for recovery (DfE, Citation2020a), is of far less direct use to schools, and may indeed lead to an over-emphasis on the need to “catch up fast” that a closer look at the research evidence does not warrant. Learning disruption literature, in contrast, focuses on how systems have responded to other unprecedented events like natural disasters. While these events are not directly parallel situations to the COVID-19 pandemic, we suggest they may provide key learning at this time and thus are the impetus for conducting this review.

Assessing the relevance of learning loss literature

The largest body of research concerned with learning loss emanates from the United States and is based on studying how time in school affects the educational achievement of different groups of children, given variations between states in the length of the summer holiday break. The literature estimates learning loss by looking at differences in test scores either side of the holiday and then calculates whether the effects it finds can be minimised by reducing the period out of school. The calculations focus on academic achievement and do not consider the wider social, organisational and disruptive issues that are characteristic of other unplanned school closures due to extreme events. As such the relevance of this literature to the extended and intermittent disruption to education that COVID-19 has caused, with the additional stresses and strains it has brought to families, requires careful consideration.

Calculating learning loss: some methodological issues

To assess the relevance of the learning loss literature, we identified five substantial reviews of the literature, published ahead of COVID-19 (Cooper et al., Citation1996, Citation2003, Citation2010; Patell et al., Citation2010; Fitzpatrick, Citation2018). Studies focus on issues that range from the effect of summer holidays (Cooper et al., Citation1996), to modifying the school year by shortening the summer break (Cooper et al., Citation2003) or extending the time pupils spend in school in other ways (Cooper et al., Citation2010; Patell et al., Citation2010; Fitzpatrick, Citation2018). The findings from these reviews reveal the limited consensus on the impact of more or less time spent out of school. The literature is also contested (cf. von Hippel, (Citation2019a), Is summer learning loss real?, Alexander’s (Citation2019) rejoinder Summer learning loss sure is real and von Hippel’s (Citation2019b) response Summer learning: key findings fail to replicate, but programs have promise in Education Next).

Estimations of learning loss are variable

In their narrative and meta-analytic review, Cooper et al. (Citation1996) concluded that summer learning loss could be calculated as equal to a loss of “one-tenth of standard deviation relative to spring test scores” (p. 264). In sum, the likely effects were variable to small. In terms of measuring growth, Von Hippel and Hamrock (Citation2019) suggested that research on learning loss and gaps are subject to measurement artefacts. First that children are taking different tests in spring and summer (the latter may be (a) harder and (b) scaled differently). They found in a study of summer learning programmes using modern adaptive testing methods that learning might be better described as slowed down versus lost. Indeed, the Education Endowment Foundation (Citation2020) commented on this body of work “there is little consideration of the nature of learning entailed and whether it is lost or has merely become rusty with disuse” (p. 7).

In this context, it is useful to consider whether learning is best understood in terms of a steady linear progression that time out may significantly disrupt, or rather moves at different rates and paces over time. Kuhfeld and Soland (Citation2020) argue that the assumption that learning growth is linear is “tenuous at best” (p. 24) and often faulty. In a study of two years of longitudinal data on reading achievement in state-mandated tests, Kuhfeld (Citation2019) found that, by looking at two results, collected at either side of the summer, many students appear to “lose” learning. However, using data from more points in time, results are more variable than the learning loss literature would suggest: up to 38% of students gain during time out of school. Counterintuitively, socio-economic status explained only 1% of the variability in these results. The study also showed that the amount gained during the previous academic year was the best predictor of summer loss, and those who lost most regained fastest. This supports the learning theories such as those proposed by Thelen and Smith (Citation1994), and Siegler (Citation1996) who both suggested that learning is best characterised by overlapping waves of progressions and regressions over time. This leads to a different analysis of the likely impact of the COVID-19 disruption on children’s learning. Indeed, in more recent research that has been carried out since the pandemic began, Kuhfeld et al., (Citation2020) have calculated that the most likely impact of disruption to learning during COVID-19 is to increase the range of attainment in any class with the consequent need for teachers to address this in their practice.

Taken together these key issues with studies into learning loss, and their inherent assumptions about the nature of growth in learning, suggest they are not the most relevant point of comparison when reflecting on the impact of COVID-19 on pupils during a period of unplanned closure. It is worth noting that in their rapid evidence assessment of reviews on summer learning loss, the Education Endowment Foundation (Citation2020) could only estimate that the gap between disadvantaged children and their peers might widen somewhere between the range of 11–75%. It is not clear how useful this information is for schools.

Assessing the relevance of the literature on learning disruption

Because sudden, forced closures are more disruptive than a planned summer holiday break and are recognised as bringing in their wake significant impacts for whole communities, we suggest that the literature on unplanned learning disruption is a more useful reference point. It takes into account not only impacts on academic achievement but also impacts on children’s social and emotional well-being. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the circumstances under which schools closed and subsequently reopened are more akin to the conditions under which education had to operate during other pandemics (e.g. SARS) or weather-related events, such as Hurricane Katrina or the Christchurch earthquakes (see Harmey & Moss, Citation2021). As with COVID-19, these closures were sudden and unplanned; communities were put under immense pressure by the events themselves, and the return to school was characterised by further “aftershocks” in the form of ongoing local outbreaks and public health restrictions.

The purpose of conducting a rapid evidence assessment of research on learning disruption was to assess the utility of this body of evidence for helping schools recover after COVID-19 or indeed, future learning disruptions, taking into account the very similar dilemmas posed for schools during ongoing periods of learning disruption. The following research question guided our enquiry:

What does the research identify as the key issues and recommendations that follow for schools as they reopen following unplanned and extended closures previously?

We defined unplanned closures as closures which followed from Seeger et al.’s (Citation1998) description of a crisis as; “a specific and non-routine event or series of events that create high levels of uncertainty and threaten or are perceived to threaten life and property or general well-being” (p. 233). To fit the circumstances in which the global COVID-19 pandemic arose and the resultant lockdowns and school closures that took place, we prioritised unplanned closures due to weather or health-related events. Here we first present a narrative synthesis of key recommendations, followed by a discussion of these recommendations, which is presented as a framework for recommendations for policy and practice post-COVID-19.

Methods

Our review of eligible studies of unplanned closures focused on the evidence of impact, key issues, and recommendations described. We followed Greenhalgh et al.’s (Citation2005) meta-narrative review technique following the recommended process of planning the literature search, searching the literature, mapping, appraisal, synthesis, and recommendations stepping from the review. In the following section, we describe our method in detail.

Planning and searching

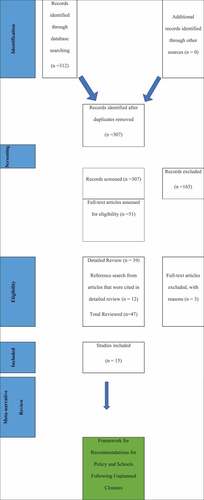

A full search of the literature was planned, using a systematic approach. Search terms, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and databases are set out in .

Table 1. Literature review search parameters

As the final step in our search we searched the reference lists of articles selected for full review to identify any further pertinent articles.

Each search was recorded in an excel file, which documented the following: search number, database, search terms, number of articles returned after search, number of articles kept after scanning, titles kept for review, study title, abstract, status (excluded, included, excluded as repeated). We used an excel spreadsheet to map our review noting the following: study title, year, author, country, event, type of study, design, study quality comments, recommendations related to achievement, social and emotional needs, technology, contingency, and any key relevant quotes.

The result of the search is documented in .

Appraisal

Our review of eligible studies of unplanned closures focused on the evidence of impact, key issues, and recommendations described. We appraised each study for its validity, quality and relevance to the research question. To find studies within the review scope, we identified studies that were (a) conducted in the context of an unplanned event (b) resulted in temporary and at times extended school closure for all pupils and (c) provided a clear description of the data sources used and analytic steps adopted. We noted what issues were examined and any recommendations from the researchers in response to the findings. We excluded from this review events such as school shootings or mass violence. We concluded these are traumatic events of a substantially different kind that raise important issues in their own right, but provide less strong parallels with COVID-19 because they do not result in extended school closure.

From this subset, we excluded studies that documented permanent school closures or student displacement from home as we were interested in the return to schooling. For example, after Hurricane Katrina there were many schools which never reopened. Studies focused on the effects of students permanently dislocated from their previous school by closure or by moving home were deemed less relevant to this review, even though there is a significant body of literature about this. We also did not include studies, that examined the impact of substantial changes to the physical infrastructure of schools (like building collapses during earthquakes). Again, these focused on issues of less immediate relevance to COVID-19.

In addition to the relevance of the paper to our research questions, studies were appraised for validity and quality of evidence (Gough et al., Citation2017). We did not exclude on study design. The majority of studies we located were qualitative. As Mutch (Citation2016) described, the literature around schools and unplanned events is “not large and includes mainly first-hand or reported accounts of how schools coped with unexpected disasters” (p. 117). In addition, we identified and included one editorial piece from Harvard Educational Review that identified lessons for the United States post Hurricanes Katrina and Rita from the international literature on schooling and displacement (Harvard Educational Review, Citation2005). Given the focus of our review we concluded this to be appropriate as we were interested in the wider policy and social impacts of school closures.

Given the predominance of qualitative studies, we followed the suggestion from Dixon-Woods et al. (Citation2014), that the studies be evaluated by considering if (a) researchers provided a clear account of the process they employed, (b) had enough data to support their conclusion, (c) used appropriate methods of analysis, and (d) that the claims were warranted given method (see also Gough et al., Citation2017).

Synthesis

Having appraised studies for relevance and quality we included 15 papers for full review in an attempt to synthesise across findings. The studies were read carefully and the key recommendations on reopening schools or reflections of participants in the studies were noted in the excel file. Each study was read and memos were taken as well as key quotes from the studies in an attempt to familiarise ourselves with the studies (Gough et al., Citation2017). We used Gough et al.’s (Citation2017) suggestion of codes “being short phrases that summarised content” and themes being “higher level concepts” to theorise groups of codes (p. 191) (see ). An initial set of codes were developed based on the emerging evidence and the studies were reread and coded by the lead author with regular team discussions to ensure reliability. Finally, the codes were grouped together into three key themes.

Table 2. Studies, themes and codes

Findings

This section reports the findings from the literature related to unplanned school closures caused by crisis events, with a focus on what were the key issues and recommendations from those that experienced similar events to the COVID-19 pandemic at the point of reopening. The three themes are School Leadership; Curricular Foci; and Mental Health and Care. Next, we provide a detailed summary of our findings under each theme with supporting detail from individual studies.

School leadership

Leaders’ local knowledge was essential in responding to the needs of the community

A key theme in 11 studies that documented unplanned school closures caused by crisis was the understanding that schools play an Nova Techsetl role in the communities in which they are located. In this literature, schools are treated as sites of safety and support at times of crisis, with school leadership playing a pivotal role in developing appropriate support (Mutch, Citation2015). For example, Fletcher and Nicholas (Citation2016) conducted a study examining the role of principals in supporting students’ learning during and after natural disaster. Using semi-structured interviews they found that school leaders know the community well and this allows them to play a pivotal role in ensuring social cohesion. Mutch (Citation2015) conducted an exploratory study with school teams using semi-structured interviews and focus groups with teachers and arts-based methods with students in four schools in Christchurch following an earthquake. She found that school leaders know their school communities best – they are aware of the nuances of the context, the relationships and the school community and that this knowledge matters for recovery. Stuart et al. (Citation2013) in case studies conducted both 6 and 36 months after major snowstorms found that school leaders have specific local knowledge, which is key in examining how schools managed temporary school closures and the consequences of these closures. O’Connor and Takahashi (Citation2014) conducted two case studies in New Zealand and Japan comparing the responses of schools post disaster. Through a series of semi-structured interviews with the school community they concluded that school leaders are best placed to see the actual needs of the community more clearly (O’Connor & Takahashi, Citation2014). These studies emphasised that extraordinary events like this brought out the best in communities while highlighting their vulnerabilities. As Stuart et al. (Citation2013) stated:

social and emotional strain comes with any event but social cohesion can intensify in times of a shared experience of an event … . [even if] social vulnerabilities are exacerbated. (p. 28-29)

In summary, the findings across studies pointed to the notion that the local knowledge of school leaders was essential in coping with the crisis and, if anything, there was a sense that leadership saw this as vital in recovery.

Learning from the experience of the event was vital in feeding into future contingency plans

In eight of the studies we reviewed, we noticed that participants and authors reflected that the event had “taught” them about the need to be prepared to communicate information effectively and clearly with the larger school community in the case of any future the event. For example, Howat et al. (Citation2012) in an ethnographic study that used both interviews and focus groups in schools following reopening after Hurricane Katrina found that issues regarding communication caused significant tension in schools and communities. Stuart et al. (Citation2013) also found that diffuse leadership and a lack of clear lines of responsibility caused tension. An implication of this is that school leadership would benefit from considering how effective communications were during the event and what can be learnt from the past for future events. Communication is particularly important, given the need to keep the school community informed about what, in effect, may be a wide range of decisions made quickly (Mutch, Citation2015). Mutch (Citation2016), conducted 25 semi-structured interviews of both individuals and groups focusing on school communities and the role of community in recovery post-crisis. Using a constant-comparative method to examine the data collected she recommended that communication must be maintained, be timely, and contain accurate information. She concluded that professional development in crisis event management and planning was also desirable.

Curricular foci

In contrast to the narrative of “catch up” and the need to account for lost learning we only found one study that examined academic achievement following a crisis event (Lamb et al., Citation2013). They examined mathematics achievement in Mississippi post-event and found negative changes for some subgroups but not all, particularly younger age groups. Harvard Education Review (Citation2005) commented on the unhelpfulness of a restrictive testing regime following hurricane Katrina. In contrast, one third of the studies included in our review focused on the role of curriculum to (a) educate about the event and (b) reflect on the event.

Children needed to be educated about the event

Schools can play a pivotal role in educating children about the event. Johnson et al. (Citation2014) conducted focus group interviews with teachers about a disaster preparedness curriculum that was implemented after the Christchurch earthquake of 2011. Findings suggested that schools can play a pivotal role in addressing misinformation, dispelling rumours and providing education about what happened and potential future events. To that end, Mutch (Citation2016) suggested that school management and school personnel would need professional development on how to utilise appropriate strategies to support response and recovery.

The curriculum can provide a means for children to express themselves

We found three studies that focused on how curriculum can be used as a vehicle to support children’s return to normalcy. For example, Johnson et al. (Citation2014) recommended changing the curriculum to respond to the event through literature and writing. Alvarez (Citation2010) conducted an enthnographic study, investigating how Hurricane Katrina impacted teaching practices in English and the role of writing and storytelling. She found that providing time and space to write was a positive pedagogical practice in these circumstances. Indeed she suggested, “teaching in these circumstances demands both a change of pace and content and an opportunity for children to both tell their stories and listen to others” (p. 37). O’Connor and Takashi (Citation2014) also commented on the use of storytelling, writing, and play and the power of the “use of curriculum to make sense of their present” (p. 47). Taken together, these findings emphasise the need to leverage curriculum at an appropriate pace to support children and to use content areas like literacy to support children to talk and write to tell their stories and express their thoughts and feelings in relation to the event.

Mental health and care

The strongest recurring theme in our review was the effect of unplanned events on the mental health of the entire school community and the role of school leadership in supporting these needs. Twelve of the 15 studies we reviewed alluded to this in their findings and recommendations.

Unplanned closures can affect the mental health of students

Schools can have a positive influence on the mental health of the school community following an unplanned event if teachers are prepared to deal with distress (Barrett et al., Citation2012). In an ethnographic study of children in schools following Hurricane Katrina, Barrett et al. (Citation2012) found that many students had difficulty with concentration. Many studies emphasised the need to equip teachers to be able to recognise and deal with the effects of trauma (Johnson et al., Citation2014; Ward et al., Citation2008). For example, Ward et al. (Citation2008) conducted a survey post-Katrina and then held a conference for discussion of the findings with survey participants. Their participants reported a need to be equipped to provide psychological support. O’Connor and Takahashi’s (Citation2014) case study of children in both New Zealand and Japan found that children’s responses to events may not manifest for months as they begin to adjust to school, process events and become more willing to talk about something distressing.

O’Connor and Takahashi (Citation2014) described how, when children returned to school following earthquakes in New Zealand and Japan, children enjoyed the distraction of school and the opportunities to play with their peers. Indeed, they stated that schools following these events can “keep children safe, support learning, support staff and family, and manage anxiety” (p. 48). As Mutch (Citation2016) suggested: schools can become a locus for supporting the community to come together, to learn to self-advocate and, indeed, celebrate successes.

School leaders play a vital role in caring for the social and emotional needs of staff

A strong theme in all the literature we reviewed was a focus on the social and emotional well-being of staff as well as students following closures due to unplanned events. Teachers may have compromised well-being after a stressful event is over and school leaders have a role to play in supporting staff (Direen, Citation2016). Returning to school is returning to normality (Howat et al., Citation2012). However, that the unplanned event may have had significant impacts on the social, emotional, physical, and economic well-being of the school community needs to be acknowledged. Both the unplanned event and the return to school may be a source of anxiety. Mutch (Citation2017) found in her study of school closures post-earthquake in Canterbury that making changes soon after the event was viewed as unhelpful. In other words, returning staff may well be under stress and creating school normalcy should be the priority (Howat et al., Citation2012; Ward et al., Citation2008).

Discussion

As governments and policymakers grapple with the implications of the learning disruption that COVID-19 has brought, they have almost exclusively drawn on learning loss literature. This literature, as we have discussed, provides estimates of predicted learning loss and how this varies according to demographics. But, as our review of the literature demonstrated, it is difficult to accurately estimate this loss and the literature on learning disruption may be more helpful. In this section, we discuss our findings in light of our review of the literature, and emerging research on the COVID-19 pandemic. Recent data collected during the COVID-19 pandemic run counter to intuition and even sophisticated statistical predictions. For example, Liu (Citation2020), in an examination of standardised testing of nearly 4.4 million students in grades 3 to 8 in the United States during Fall 2020 found that student achievement was “on average, 5 to 10 percentile points lower in maths, but similar in reading” (p. 32). Given the uncertainty in the predictions and the difficulty of knowing whether they really hold good over time, drawing on learning disruption literature, based on circumstances which are more similar to the current crisis, provides a far more useful basis for decision-making over ways forward. For policymakers, it points to where funding is needed and how it should be spent. For schools, it provides useful recommendations about potential difficulties and how support can best target the whole school community.

It is notable that research on educational systems that faced events similar to the COVID-19 pandemic rarely referred to learning loss – and when they did it was in relation to mathematics. They were more concerned with the role of leadership, using the curriculum to support children, and addressing children’s mental health and well-being. In this discussion, we consider what that means in the context of the current COVID-19 pandemic.

The extraordinary and unplanned events documented in our review highlighted the vital role of school leaders in supporting their communities, developing contingency plans, and caring for the social and emotional needs of staff. School leaders played central roles in recognising and responding to the needs of their community, particularly the most vulnerable, because of their local knowledge. This fits with emerging research conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Moss et al. (Citation2020) found that during the first COVID-19 lockdown in England, headteachers and teachers were primarily engaged in supporting the community and the health and welfare of families. As Harris (Citation2020) suggested “the current situation demands messy, trial-and-error, butterflies-in-the stomach leadership” (p. 324) – but that headteachers are well placed to respond appropriately to the needs of their communities. It follows that they will know where funds are needed.

Our findings also suggested that, as schools reopened following unplanned events they identified that they needed or would have liked time to reflect on their response to closures and subsequent reopening to develop contingency plans with a particular focus on lines of communication (Mutch, Citation2016). Emergency preparedness plans are designed to address these issues in the case of natural disasters (see Johnson & Ronan, Citation2014). While certainly, school closures related to the COVID-19 pandemic were different to closure due to an earthquake there are several similarities in terms of the challenges it posed for school leadership. School leaders need time and support to develop contingency plans to respond to sudden demands to close and reopen schools while continuing to teach online, as required by the English Department of Education (DfE, Citation2020b).

In the context of other unplanned events staff mental health was a key concern. Recent evidence in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic (Niedzwiedz et al., Citation2020) suggests an increase in mental distress in the general population. In terms of the teaching profession, Allen, Jerrim and Sims (Citation2020) in a survey of 8,000 teachers and headteachers, found that work-related anxiety rose for headteachers, particularly on school reopening. This fits with our findings and may indicate that some staff, particularly leaders themselves, will be returning to school under stress and creating school normalcy should be a priority (Howat et al., Citation2012; Ward et al., Citation2008). This suggests that leadership must be both supported themselves but also equipped to deal with this.

As schools reopened after previous unplanned events like hurricane Katrina or SARS, our findings highlighted the need to appropriately pace and leverage curriculum to support a return to normality (Alvarez, Citation2010). There were three dimensions to this finding. First, in terms of learning, children needed more time and flexible opportunities to learn. This finding runs counter to the idea of “catch-up” which is a logical response to the notion of lost learning. Given, however, the increase in childhood anxiety, the disproportionate impacts on vulnerable children, and lack of access to services that occurred during other crisis events (see Alvarez, Citation2010) and, indeed, that has occurred in the context of COVID-19 (see Gilleard et al., Citation2020) perhaps a different approach is needed. Gilleard et al’s (Citation2020) suggestion of a “gentle, phased approach” (p. 16) characterised by reassurance and routine fits with the recommendations of educators who experienced similar unplanned events (e.g. O’Connor & Takahashi, Citation2014).

The second dimension of this finding was the need to leverage curriculum to support children to learn about the event and respond to the event. Our findings suggested that the arts and literature could be used imaginatively to support children’s expression. First, children need to be taught about the event. For example, in New Zealand a child-friendly curriculum about disaster preparedness was implemented (see Johnson et al., Citation2014). Focusing on supporting the well-being of children during COVID-19 is particularly important. Finally, our findings suggest that literacy (including reading, writing, and oral language) all provided opportunities for students to reflect on their experiences, providing social and cultural context for introducing and talking about events (Alvarez, Citation2010).

There have been substantial changes to how schools and society operate to mitigate public health risks, like wearing masks and social distancing. In addition to this, children may have experienced illness themselves or of close relatives or friends. Pearcey et al. (Citation2020), in a survey of over 10,000 parents and carers found that parents were most commonly concerned with the social and emotional health of their children returning to school, their ability to understand COVID-19, and the necessary precautions that would need to be adhered to in order to prevent transmission. It seems sensible, therefore, to provide all children with specific lessons about COVID-19 and reflecting on their own experiences that are age appropriate, which might in turn reduce anxiety around the issue.

Mental health

Perhaps the most compelling finding from our assessment of the literature about previous learning disruptions is the need to attend to mental health needs of both staff and students. This finding permeates the findings provided previously about curriculum and the role of leadership. As the current pandemic continues, children may have experienced illness, food poverty, and prolonged absence from a wider family network and, indeed, their friends, and may have suffered or be suffering from trauma. Jeffrey et al. (Citation2021) reported an increased prevalence of anxiety and depression in young people with those with pre-existing mental or physical effects being at increased risk of mental health issues due to stress and isolation. In our review, we noticed how teachers reported that they often felt ill-equipped to deal with the acute mental health issues that increased following an unplanned event and expressed a desire for training to deal with trauma (e.g. Ward & Shelley, Citation2008) and crisis planning (e.g. Mutch, Citation2016). This fits with Gilleard et al.’s (Citation2020) summary of the emerging evidence about the negative effects of COVID-19 and children’s mental health and recommendation that there was a strong need to prioritise mental health and well-being.

Recommendations and conclusions

In line with Greenhalgh et al.’s (Citation2005) suggested structure for a meta-narrative review, we take our synthesis forward to form recommendations for educators, policymakers and researchers. As we emerge from an ongoing global pandemic there is no doubt that we will learn a lot about the effects of this unplanned event on children both in terms of academic achievement and social and emotional well-being. Given the unprecedented nature of the event, the research community has drawn primarily on a body of literature about learning loss which sends us “down a path” which focuses solely on academic achievement where time in school equals learning. Drawing on a body of literature of comparable events our findings are mirroring the emerging evidence about the effects of COVID-19 on schools and children. We suggest that our recommendations below, stemming from our findings, may well provide a more useful framework for teachers and policymakers in terms of the specific measures and support that school leaders, teachers and children need.

Based on our review, we provide six recommendations:

Recommendation 1: Given the vital role local knowledge played in supporting the school community we suggest providing school leadership with the autonomy to use funds as they see fit.

Recommendation 2: The need to develop contingency plans is essential. Provide school leadership with the time and support to reflect on the experience of the event and to develop a clear contingency plan that would account for (a) communication systems (b) chains of information and (c) the needs of the community.

Recommendation 3: The mental health of children and school personnel was a central concern post-unplanned event. We advise providing school leadership with the necessary resources to support their own, employees’ and children’s mental health.

Recommendation 4: Return to normal with an acknowledgement that children need more time and flexible opportunities to learn, focusing on content that will provide a vehicle for children to express themselves through the arts and literature.

Recommendation 5: Provide learning materials that will educate children about the facts about COVID-19 and opportunity to reflect on the events.

Recommendation 6: Conduct research that moves beyond calculating learning loss and documents the reflections of the school community on the experience of educating during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Like any study, there are limitations to this research. We drew on a small body of studies to synthesise our findings and this limits the generalisability of our findings. That being said, we aimed to provide a review of literature that documents, as far as is possible, events similar to the COVID-19 pandemic. As the world moves towards recovery from an unprecedented pandemic, our hope is that this study provides a clear review of two bodies of literature and their utility to consider the next best steps for the education system as a whole.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alexander. (2019). Summer learning loss sure is real. https://www.educationnext.org/summer-learning-loss-sure-is-real-response/

- Allen, R., Jerrim, J., & Sims, S. (2020). How did the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic affect teacher wellbeing? (CEPEO Working Paper Series 20–15). Centre for Education Policy and Equalising Opportunities, UCL Institute of Education. (revised Sep 2020).

- #Alvarez, D. (2010). “I had to teach hard”: Traumatic conditions and teachers in Post-Katrina classrooms. The High School Journal, 94(1), 28–39. https://doi.org/10.1353/hsj.2010.0007

- Andrew, A., Cattan, S., Costa-Dias, M., Farquharson, C., Kraftman, L., Krutikova, S., Phimister, A., & Sevilla, A. (2020). Learning from lockdown: Real-time data on children’s experiences during home learning (IFS Briefing Note BN288). Insitute for Fiscal Studies. https://www.ifs.org.uk/uploads/Edited_Final-BN288%20Learning%20during%20the%20lockdown.pdf

- #Barrett, E. J., Ausbrooks, C. Y. B., & Martinez-Cosio, M. (2012). The tempering effect of schools on students experiencing a life-changing event: Teenagers and the Hurricane Katrina evacuation. Urban Education, 47(1), 7–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085911416011

- Blainey, K., & Hannay, T. (2021). The impact of school closures on autumn 2020 attainment. RS Assessment and School Dash. https://www.risingstars-uk.com/media/Rising-Stars/Assessment/RS_Assessment_white_paper_2021_impact_of_school_closures_on_autumn_2020_attainment.pdf

- Cooper, H., Allen, A. B., Patall, E. A., & Dent, A. L. (2010). Effects of full-day kindergarten on academic achievement and social development. Review of Educational Research, 80(1), 34–70. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654309359185

- Cooper, H., Nye, B., Charlton, K., Lindsay, J., & Greathouse, S. (1996). The effects of summer vacation on achievement test scores: A narrative and meta-analytic review. Review of Educational Research, 66(3), 227–268. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1170523.

- Cooper, H., Valentine, J., Charlton, K., & Melson, A. (2003). The effects of modified school calendars on student achievement and on school and community attitudes. Review of Educational Research, 73(1), 1–52. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3516042.

- #Direen, G. (2016). My head is always full! Principals as leaders in a post disaster setting: Experiences in greater Christchurch since 2010 and 2011 earthquakes. Unpublished manuscript. https://www.educationalleaders.govt.nz/Leading-change/Leading-and-managing-change/Principals-as-leaders-in-a-post-disaster-setting

- Department for Education. (2020a). COVID-19 catch up plans. Retrieved December 16, 2020, from https://www.gov.uk/government/news/billion-pound-COVID-19-catch-up-plan-to-tackle-impact-of-lost-teaching-time

- Department for Education. (2020b). Get help with remote education. http://www.gov.uk/guidance/get-help-with-remote-education

- Dixon-Woods, M., Baker, R., Charles, K., Dawson, J., Jerzembe, K. G., Martin, G., McCarthy, I., McKee, L., Minion, J., Ozieranski, P., Willars, J., Wilkie, P., & West, M. (2014). Culture and behaviour in the English National Health Service: Overview of lessons from a large multimethod study. BMJ Quality & Safety, 23(2), 106–115. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001947

- Education Endowment Foundation. (2020). Impact of school closures on the attainment gap: Rapid evidence assessment.

- Education Endowment Foundation. (2021). Best evidence on impact of COVID-19 on pupil attainment. https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/eef-support-for-schools/covid-19-resources/best-evidence-on-impact-of-school-closures-on-the-attainment-gap/

- Fitzpatrick, D. (2018). Meta-analytic evidence for year-round education’s effect on science and social studies achievement. Middle Grades Research Journal, 12(1), 1–8.

- #Fletcher, J., & Nicholas, K. (2016). What can school principals do to support students and their learning during and after natural disasters? Educational Review, 68(3), 358–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2015.1114467

- Gilleard, A., Lereya, S. T., Tait, N., Edbrooke-Childs, J., Deighton, J., & Cortina, M. A. (2020). Emerging evidence (Issue 3): Coronavirus and children and young people’s mental health. Evidence Based Practice Unit.

- Gough, D., Oliver, S., & Thomas, J. (2017). An introduction to systematic reviews. SAGE.

- Greenhalgh, T., Robert, G., Macfarlane, F., Bate, P., Kyriakidou, O., & Peacock, R. (2005). Storylines of research in diffusion of innovation: A meta-narrative approach to systematic review. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 61(2), 417–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.001

- Harmey, S., & Moss, G. (2021). CIE0570: Written evidence submitted by the International literacy centre to the education select committee Inquiry into the impact of COVID-19 on education and children’s services. UCL Institute of Education. https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/12497/pdf/

- Harris, A. (2020). COVID-19 – School leadership in crisis? Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 5(3/4), 321–326. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JPCC-06-2020-0045/full/html#sec003

- #Harvard Educational Review. (2005). Katrina and Rita: What can the United States learn from international experiences with education in displacement? Harvard Educational Review, 75(4), 357–363.

- #Howat, H., Curtis, N., Landry, S., Farmer, K., Kroll, T., & Douglass, J. (2012). Lessons from crisis recovery in schools: how hurricanes impacted schools, families and the community. School Leadership & Management, 32(5), 487–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2012.723613

- Jeffrey, M., Lereya, T., Edbrooke-Childs, J., Deighton, J., Tait, N., & Cortina, M. (2021). Emerging evidence: Coronavirus and children and young people's mental health. Issue 7 Research Bulletin. Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families: Evidence Based Practice Unit. https://www.annafreud.org/media/13549/emergingevidence7.pdf

- Johnson, B., Kuhfeld, M., & Tarasawa, B. (2021). How did students fare relative to the COVID-19 learning loss projections? Sage Perspectives. https://perspectivesblog.sagepub.com/blog/research/how-did-students-fare-relative-to-the-COVID-19-learning-loss-projections

- #Johnson, V. A., & Ronan, K. R. (2014). Classroom responses of New Zealand school teachers following the 2011 Christchurch earthquake. Natural Hazards (Dordrecht), 72(2), 1075–1092. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-014-1053-3

- Kuhfeld, M. (2019). Surprising new evidence on summer learning loss. Phi Delta Kappan, 101(1), 25–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721719871560

- Kuhfeld, M., & Soland, J. (2020). The learning curve: Revisiting the assumption of linear growth across the school year (EdWorkingPaper: 20–214). Retrieved from Annenberg Institute at Brown University. https://doi.org/10.26300/bvg0-8g17

- Kuhfeld, M., Soland, J., Tarasawa, B., Johnson, A., Ruzek, E., & Liu, J. (2020). Projecting the potential impacts of COVID-19 school closures on academic achievement (EdWorkingPaper: 20–226). Retrieved from Annenberg Institute at Brown University. https://doi.org/10.26300/cdrv-yw05

- #Lamb, J., Lewis, M., & Gross, S. (2013). The Hurricane Katrina effect on mathematics achievement in Mississippi. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/ssm.12003.

- Liu, J. (2020). Projecting the impact of the COVID-19 spring school closures on student learning. University of Maryland College of Education. https://mldscenter.maryland.gov/egov/Publications/ResearchSeries/2020/JingLiu_Dec2020.pdf

- Moss, G., Allen, R., Bradbury, A., Duncan, S., Harmey, S., & Levy, R. (2020). Primary teachers experience of the COVID-19 lockdown: Eight key messages for policy-makers going forward. UCL Institute of Education. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10103669/1/Moss_DCDT%20Report%201%20Final.pdf

- Moss, G., Webster, R., Bradbury, A., & Harmey, S. (2021). Unsung heroes: The role of teaching assistants and classroom assistants in keeping schools functioning during lockdown. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10125467/

- #Mutch, C. (2015). Leadership in times of crisis: Dispositional, relational and contextual factors influencing school principals’ actions. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 14(2), 186–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2015.06.005

- #Mutch, C. (2016). Schools as communities and for communities: Learning from the 2010-2011 New Zealand Earthquakes. The School Community Journal, 26(1), 115.

- #Mutch, C. (2017). Winners and losers: School closures in post-earthquake Canterbury and the dissolution of community. Waikato Journal of Education, 22(1), 73–95. https://doi.org/10.15663/wje.v22i1.543

- Niedzwiedz, C. L., Green, M. J., Benzeval, M., Campbell, D., Craig, P., Demou, E., Leyland, A., Pearce, A., Thomson, R., Whitley, E., & Katikireddi, S. V. 2020. Mental health and health behaviours before and during the initial phase of the COVID-19 lockdown: Longitudinal analyses of the UK Household Longitudinal Study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 75(3), 224-231. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2020-215060.

- #O’Connor, P., & Takahashi, N. (2014). From caring about to caring for: Case studies of New Zealand and Japanese schools post disaster. Pastoral Care in Education: The Place of Pastoral Care in Disaster Contexts, 32(1), 42–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2013.875584

- Patall, E., Cooper, H., & Allen, A. (2010). Extending the school day or school year: A systematic review of research (1985–2009). Review of Educational Research, 80(3), 401–436. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654310377086

- Pearcey, S., Shum, A., Waite, P., Patalay, P., & Creswell, C. (2020). Report 05: Changes in children and young people’s mental health symptoms and ‘caseness’ during lockdown and patterns associated with key demographic factors. Co-SPACE study; University of Oxford.

- Seeger, M. W., Sellnow, T. L., & Ulmer, R. R. (1998). Communication, organization and crisis. In M. E. Roloff (Ed.), Communication Yearbook (pp. 21). Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Siegler, R. S. (1996). Emerging minds: The process of change in children’s thinking. Oxford University Press.

- #Stuart, K. L., Patterson, L. G., Johnston, D. M., & Peace, R. (2013). Managing temporary school closure due to environmental hazard: Lessons from New Zealand. Management in Education, 27(1), 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020612468928

- Thelen, E., & Smith, L. B. (1994). MIT Press/Bradford book series in cognitive psychology. A dynamic systems approach to the development of cognition and action. The MIT Press.

- #Tsai, V., Khan, N. M., Shi, J., Rainey, J., Gao, H., & Zheteyeva, Y. (2017). Evaluation of unintended social and economic consequences of an unplanned school closure in rural Illinois. Journal of School Health, 87(7), 546–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12525

- UNESCO. (2020a). COVID-19 impact on education. Retrieved December 16, 2020, from https://en.unesco.org/COVID-1919/educationresponse

- UNESCO. (2020b). COVID-19: 10 recommendations to plan distance learning solutions. https://en.unesco.org/news/COVID-19-10-recommendations-plan-distance-learning-solutions

- UNESCO. (2021). Ulster University Northern Ireland parent surveys: Experiences of supporting children’s home learning during COVID-19. https://www.ulster.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/597969/UU-School-survey-Report-web.pdf

- von Hippel, P., & Hamrock, C. (2019). Do test score gaps grow before, during, or between the school years? Measurement artifacts and what we can know in spite of them. Sociological Science, 6, 43–80. https://doi.org/10.15195/v6.a3

- Von Hippel, P. T. (2019a). Is summer learning loss real? How I lost faith in one of education research’s classic results. Education Next, 19(4), 8–14.

- Von Hippel, P. T. (2019b). Summer learning: Key findings fail to replicate, but programs have promise. Education Next. https://ed.codeandsilver.com/summer-learning-key-findings-fail-replicate-but-programs-still-promise/

- #Ward, M. E., & Shelley, K. (2008). Hurricane Katrina’s impact on students and staff members in the Schools of Mississippi. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk (JESPAR), 13(2–3), 335–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/10824660802350474