Abstract

Refutation texts seem to be a promising approach to counter misconceptions. They provoke a cognitive conflict by explicitly naming a misconception and correcting it with a scientific explanation. However, the literature reports mixed findings about their effectiveness, underlining the need to examine potential moderators. For example, when presenting preservice teachers a refutation text to combat an educational myth, the instructed reading goal might be of importance because reading goals can affect how readers process a text. In this study, we examined whether reading goals influence the effect of refutation texts and facilitate belief change about an educational myth in preservice teachers. The preregistered experiment (N = 168) followed a 2 × 2 × 2 mixed design with the between-participants factors text type (refutation vs. traditional) and reading goal (explanation vs. entertainment), and the within-participants factor time (before vs. after reading). Participants who had read a refutation text rather than a traditional text were more likely to change their false belief. However, the refutation effect was independent of participants’ reading goals. These results strengthen existing evidence that refutation texts are better suited for addressing misconceptions than traditional textbooks. However, we still require a better understanding of the conditions that increase refutation text effectiveness.

Introduction

Misconceptions—beliefs that contradict the state of research—threaten political, societal, and private decisions in various domains, such as climate change, vaccination, nutrition, or education (Ecker et al., Citation2022; Kendeou et al., Citation2019; Roozenbeek et al., Citation2023). However, refuting misconceptions is challenging because they are often widespread and resistant to change (Ecker et al., Citation2022; Sinatra & Jacobson, Citation2019). According to conceptual change and knowledge revision research, belief change can be initiated most likely by explicitly stating that a certain belief is false and by presenting a scientific explanation that refutes the myth (Rousseau, Citation2021; Tippett, Citation2010; Zengilowski et al., Citation2021). This is the idea underlying so-called refutation text interventions. Several studies have indicated that refutation texts are a promising means of countering misconceptions in various domains. However, their effectiveness has been shown to vary considerably, ranging from null effects to large effects (Guzzetti et al., Citation1993; Kendeou et al., Citation2014; Zengilowski et al., Citation2021).

Therefore, it is crucial to better understand the conditions under which refutation texts successfully mitigate misconceptions and to shed light on potential moderators (Tippett, Citation2010; Zengilowski et al., Citation2021). In particular, reading goals might be important because they can affect the amount of time and effort readers invest in reading and understanding the text (Latini et al., Citation2019; McCrudden & Schraw, Citation2007). In fact, reading goals are considered one of the most important factors in research on text processing (Linderholm, Citation2006; McCrudden & Schraw, Citation2007). However, despite their relevance, the role of reading goals has not been sufficiently addressed in research on refutation texts. We suggest that refutation texts may more likely induce a cognitive conflict if a specific reading goal promotes better understanding and deeper processing and, thus, foster the integration of new, accurate information.

In this study, we address this research gap and investigate whether the instruction of different reading goals can influence the effectiveness of a refutation text. The present contribution expands our knowledge about the conditions under which refutation texts are more likely to promote conceptual change. We examine the effect of reading goals on a refutation intervention using an educational topic as an example. Research shows that a large variety of myths related to learning and teaching are prevalent in the general public, as well as among preservice and active teachers (Asberger et al., Citation2021; Deibl & Zumbach, Citation2023; Dekker et al., Citation2012). For example, in several surveys, a worrying large proportion of teachers indicated to believe that differences in hemispheric dominance can help explain individual differences between learners (Dersch et al., Citation2022; Hughes et al., Citation2021; Prinz et al., Citation2022). Believing in educational myths can have a negative effect as early as during initial teacher education and, thus, on preservice teachers’ learning processes during their studies and their future teaching practice (Blanchette Sarrasin et al., Citation2019; Grospietsch & Lins, Citation2021; Hughes et al., Citation2021). Our study can help improve the use of refutation texts in teacher education to combat educational myths among preservice teachers. Below, we explain the effects of refutation texts on conceptual change and why reading goals potentially moderate their effectiveness.

Promoting conceptual change with refutation texts

Research about conceptual change examines the ways in which individuals may change their personal yet inadequate conceptions or assumptions while learning scientifically correct information (Chi, Citation2008; Vosniadou, Citation2013). Research shows that conceptual change is not easy to achieve, as confrontation with information that contradicts one’s own beliefs can trigger defensive reactions, such as biased interpretation of the information or even devaluating science (Chinn & Brewer, Citation1993; Futterleib et al., Citation2022; Sinatra & Pintrich, Citation2003; Thomm et al., Citation2021). Hence, conceptual change interventions frequently do not lead to full belief change. However, conceptual change interventions may at least initiate a reduction in a person’s confidence in their misconceptions (Hughes et al., Citation2013; Taylor & Kowalski, Citation2004).

Refutation texts are a promising approach to eliciting conceptual change. They explicitly point out misconceptions and correct them immediately with a scientific explanation (Tippett, Citation2010; Zengilowski et al., Citation2021). The typical structure of refutation texts consists of three components: (1) explicit statement of a frequently held misconception, (2) explicit refutation of this misconception, and (3) presentation of a scientific and understandable explanation of why it is a misconception (Tippett, Citation2010; Zengilowski et al., Citation2021). According to the underlying theory, refutation texts can initiate conceptual change because they cause cognitive conflict when a person is confronted with information that reveals their personal assumptions to be false or questionable (Kendeou & O'Brien, Citation2014; Sinatra & Pintrich, Citation2003; Tippett, Citation2010). In contrast, traditional texts often merely describe the correct state of research on a topic without explicitly addressing specific misconceptions.

The Knowledge Revision Components framework (KReC; Kendeou & O'Brien, Citation2014) provides a more comprehensive theoretical model that explains the cognitive processes that occur while reading refutation texts based on five key principles: (1) encoding of new correct information, (2) passive activation of related information in long-term memory, (3) coactivation of new correct information and old incorrect assumptions, (4) integration of new information in the existing network of beliefs, and (5) competing activation of old and new information. Conceptual change occurs when the activation of the new correct information increases, while the activation of the old incorrect information is reduced or even eliminated. Refutation texts foster this by eliciting the coactivation of incorrect assumptions and scientifically based explanations—the necessary first step in the knowledge revision process (Kendeou & O'Brien, Citation2014).

Evidence of the effectiveness of refutation texts is promising and mixed at the same time (Guzzetti et al., Citation1993; Tippett, Citation2010; Zengilowski et al., Citation2021). Many studies show that refutation texts can induce conceptual change in a variety of topics; however, the effect sizes vary considerably (e.g., Broughton et al., Citation2011; Kendeou et al., Citation2019; Thacker et al., Citation2020; Trevors & Kendeou, Citation2020): whereas some studies reported on large effects, others yielded quite small ones, or even null effects (e.g., Aguilar et al., Citation2019; Ariasi & Mason, Citation2014; Ferrero et al., Citation2020; Menz et al., Citation2020; Prinz et al., Citation2019; Södervik et al., Citation2015). Thus far, there is little evidence to explain this heterogeneity. Zengilowski et al. (Citation2021) consider the theory of refutation texts to be still “fragile” (p. 3), as long as relevant moderators are unknown. Therefore, researchers have advocated for more research illuminating the conditions that promote conceptual change through refutation texts (Tippett, Citation2010; Trevors & Muis, Citation2015; Zengilowski et al., Citation2021). The present study tied to this research gap by investigating the role of different reading goals when people read a refutation text compared to a traditional text.

The role of reading goals in the refutation effect

Reading goals influence how people interact with a text and, therefore, may be a game changer for whether refutation texts have the intended effect on conceptual change. That is, because readers align their cognitive activities and resources with their goals, goals shape the reading process and its outcomes (Latini et al., Citation2019; McCrudden & Schraw, Citation2007; Rouet et al., Citation2017). Therefore, reading goals have been considered a critical factor in research on text processing (Britt et al., Citation2022; Chinn et al., Citation2014; McCrudden & Schraw, Citation2007). For example, it can make a great difference in the way readers process a text, whether they read it to learn specific information (e.g., to get an explanation or to learn something in an educational context) or to entertain themselves. Indeed, research on reading goals has frequently contrasted reading for learning with reading for entertainment because both goals are common in students’ everyday lives (Latini et al., Citation2019; Linderholm & van den Broek, Citation2002; Yeari et al., Citation2015). Several experiments have shown that asking students to imagine themselves reading for study purposes (e.g., to prepare for an exam or to find an explanation) leads to better comprehension and recall, as compared to reading for entertainment (Bråten & Strømsø, Citation2009; McCrudden & Schraw, Citation2007; Narvaez et al., Citation1999). One reason might be that reading for study may foster slower, more thorough reading and deeper elaboration of the text’s content (van den Broek et al., Citation2001). In contrast, when reading for entertainment, individuals read faster and less attentively, and therefore process the text only superficially (Linderholm, Citation2006). In addition, individuals who read for entertainment articulate more opinions about the text, make more connections to information unrelated to the text, and remember less content (Linderholm & van den Broek, Citation2002; van den Broek et al., Citation2001).

Based on these findings, we suggest that a reading goal that promotes deeper and more attentive reading will foster the refutation effect because it enhances the encoding of text information, including a scientifically correct explanation (KReC Principle 1). As reading for explanation promotes attentive and deep reading, readers also integrate the correct information into their belief system (KReC Principle 4). As a consequence, the chance for correct information to win the competition of activation increases (KReC Principle 5). According to these assumptions, reading a refutation text for an explanation may foster conceptual change. By contrast, as reading for entertainment is associated with superficial reading, encoding (KReC Principle 1) and integrating new information into the belief system (KReC Pinciple 4) are impeded. Instead, when reading for entertainment, more connections are made to information unrelated to the text. Therefore, previous misconceptions are more likely to be activated (KReC Principle 2) rather than attention being drawn to the new, correct text information. Accordingly, the scientific explanation in the refutation text should be less likely to win the competition for activation (KReC Principle 5). Thus, reading a refutation text for entertainment might mitigate the refutation effect.

Despite their importance, the existing research on refutation texts has paid little attention to the impact of reading goals. Frequently, studies did not provide participants with any explicit reason for why they shall read a text or about what to do with the read information (e.g., Aguilar et al., Citation2019; Butterfuss & Kendeou, Citation2020; Lassonde et al., Citation2016; Mason et al., Citation2008). Thus, the formation of a reading goal was left to the reader. So far, only a few studies have specified reading goals, such as understanding the text (Kendeou et al., Citation2019; Kendeou & van den Broek, Citation2007; Prinz et al., Citation2019; Thacker et al., Citation2020) or writing a test afterwards (Kowalski & Taylor, Citation2009; McCrudden, Citation2012; Prinz et al., Citation2021). Still, the effects of such instructions on the conceptual change process are not yet well understood. To our knowledge, only one study has explicitly addressed reading goals in the context of refutation texts. Trevors and Muis (Citation2015) instructed undergraduates either to make sure they understood what they read (general comprehension) or to read the text in order to give an explanation to a friend afterwards (elaborative interrogation). Next, participants read either a refutation text or a traditional text about the topic of evolution. Participants in the general comprehension condition articulated more elaborative inferences during a think-aloud task while reading the text. In contrast, participants in the elaborative interrogation condition showed more text-based inferences and better conceptual understanding in the post-reading essay task.

The present study

This study aimed to investigate whether different reading goals moderate the effect of a refutation text on preservice teachers’ conceptual change about an educational topic. More precisely, we examined the ways in which text type (refutation vs. traditional text) and reading goal (for an explanation vs. for entertainment) interact and affect participants’ conceptual change. We selected these reading goals based on their relevance in previous work on text processing (Linderholm & van den Broek, Citation2002; Narvaez et al., Citation1999; van den Broek et al., Citation2001). Moreover, as argued above, these reading goals are quite different and allow qualitative differences in text processing to be expected. As a text topic, we chose the alleged role of hemispheric dominance on learning, a well-known neuromyth that is highly prevalent in both pre- and in-service teachers (see Materials; Dekker et al., Citation2012; Ferrero et al., Citation2016; Krammer et al., Citation2020).

As mentioned above, conceptual change can be reflected in a person’s total agreement with a claim (i.e., belief change) or in a reduction of a person’s confidence in a misconception (Hughes et al., Citation2013; Taylor & Kowalski, Citation2004). Confidence accuracy indicates how appropriate a person’s confidence judgment is with regard to their belief correctness. A total belief change toward a correct belief as well as a reduction of the confidence judgment in a misconception lead to an improvement of a person’s confidence accuracy. Looking at confidence accuracy as additional dependent variable allowed us to determine whether participants’ confidence in the misconception was at least shaken, even if they might not overcome it completely. In addition, to obtain a deeper understanding of participant’s correct or incorrect beliefs, we assessed participants’ belief justifications in a writing task.

Specifically, we hypothesized that participants who hold a misconception about hemispheric dominance are more likely to change their beliefs when reading a refutation text rather than a traditional text (H1a). We assumed this effect to be stronger when participants’ reading goal was to get an explanation rather than to read for entertainment (H1b). Similarly, we hypothesized that participants who hold a misconception about hemispheric dominance show a higher increase in confidence accuracy after reading a refutation text about hemispheric dominance rather than a traditional text (H2a). We assumed this effect to be stronger when participants’ reading goal was to obtain an explanation rather than an entertainment (H2b).

Before data collection, we preregistered these hypotheses, as well as details of the study design, measures, and analytic procedures (https://osf.io/3wgqp). Next to the confirmatory test of the stated hypotheses, we explored whether text type and reading goals influenced whether participants used misconceptions when eventually justifying their beliefs.

Methods

Data and complete study materials are available on the OSF site (https://osf.io/kwh9d/).

Design and participants

The randomized online experiment followed a 2 × 2 × 2 mixed design with the between-participants factors text type (refutation vs. traditional) and reading goal (explanation vs. entertainment) as well as the within-participants factor time (before vs. after reading the text). The dependent variables were participants’ belief change in the misconception of hemispheric dominance and change in their confidence judgment.

We recruited preservice teachers enrolled in German teacher education programs via mailing lists or, whenever possible, via personal recruiting in university lectures. Participants could enter a lottery of vouchers as an incentive for participation. Based on an a priori power analysis, we aimed at a sample size of N = 176 participants with a misconception about hemispheric dominance to have sufficient statistical power of 90% for detecting effects of medium size with a significance level of α ≤ 0.05. Because we needed to exclude participants who did not hold the misconception at t1 to examine the refutation effect, and because online surveys often have high exclusion and dropout rates (Galesic, Citation2006), we recruited a total of N = 326 participants. According to the preregistered exclusion criteria, participants’ data were excluded when they did not finish the experiment (n = 118), could not be clearly assigned to one condition due to technical error (n = 2), and did not pass the seriousness check (n = 3). Finally, out of the N = 203 remaining preservice teachers, 35 participants who did not endorse the misconception about hemispheric dominance were excluded from the analyses. The final sample size included data of N = 168 participants and still provided sufficient statistical power (89%). There were 48% teacher students enrolled in a bachelor’s program, 48% in a master’s program, and 4% in a state examination program not distinguishing between the bachelor’s and master’s phases of study. On average, the participants studied in their third study year (SD = 1.43). The majority (87%) of participants were female (13% male, 0% non-binary). This gender distribution results from the majority of participants aiming to become teachers at elementary school (81%)—a school type that is dominated by female teachers.

We followed the American Psychology Association’s (American Psychological Association, Citation2017) ethical principles, including voluntary participation based on informed consent. The university’s internal review board confirmed that the study was of negligible risk.

Materials

The text materials addressed the neuromyth of hemispheric dominance. According to this misconception, differences in hemispheric dominance can explain individual differences in learners and should be taken into account in teaching (Dekker et al., Citation2012; Ferrero et al., Citation2016; Hughes et al., Citation2021). There is a large body of literature refuting this misconception by pointing out that its underlying assumptions are a gross oversimplification of brain functioning and learning (De Bruyckere et al., Citation2015; Holmes, Citation2016; Lilienfeld et al., Citation2011). Nevertheless, it is still one of the most widespread educational myths among teachers (Dekker et al., Citation2012).

We created two texts about hemispheric dominance: a refutation text (177 words) and a traditional text (182 words). The main body of both texts was taken from a textbook on educational psychology (Woolfolk, Citation2014), and both texts contained information inconsistent with the hemispheric dominance myth. Adhering to refutation text principles, the refutation text began by explicitly stating that hemispheric dominance is a myth and provided a direct refutation (“It is a common assumption that differences in hemispheric dominance can help explain individual differences between learners. However, this assumption is incorrect.”). To ensure that both texts had approximately the same length, we added two neutral introductory sentences to the traditional text (“In teacher studies or in the media, you may have heard of the term hemisphere dominance. The following text explains what the term means and what role hemisphere dominance has in learning.”). Except for these differences, the texts were identical. In a pilot study, participants confirmed the high comprehensibility and credibility of the texts on a seven-point Likert scale.

To manipulate reading goals, we adapted two instructions from prior research (Latini et al., Citation2019; Linderholm & van den Broek, Citation2002; Narvaez et al., Citation1999; van den Broek et al., Citation2001): reading for an explanation (“Imagine you are sitting in a study course reading a text about the role of hemisphere dominance for learning. You read the text to get an explanation of how hemisphere dominance should be considered in learning.”) and reading for entertainment (“Imagine you are sitting relaxed at home and scrolling through the timeline of your social media account. There, you find a text about the role of hemisphere dominance in learning. You read the text for entertainment.”).

Measures

Topic beliefs and belief changes

For measuring the prevalence of the false belief about hemispheric dominance, we used an established item with a forced-choice answer format (Bensley et al., Citation2014; Pieschl et al., Citation2021; Taylor & Kowalski, Citation2012): participants had to decide which of two statements about hemispheric dominance they agreed with (correct belief: “Differences in hemispheric dominance (leftbrain, rightbrain) cannot help explain individual differences among learners”; misconception: “Differences in hemispheric dominance (leftbrain, rightbrain) can help explain individual differences among learners”). To assess potential belief changes, participants answered this question before and after reading the text. As aforementioned, only participants endorsing the misconception at t1 were included in the study. When choosing the correct statement after the intervention, belief change was coded as “Yes”, whereas when choosing the incorrect statement after the intervention, belief change was coded as “No”.

Confidence accuracy

To assess how confident participants were in their belief about hemispheric dominance, we adapted an item on metacognitive judgment (Menz et al., Citation2024; Pieschl et al., Citation2021; Taylor & Kowalski, Citation2004). Participants rated their confidence in their belief on a scale from 50% (I guessed) to 100% (I am 100% certain) (cf. Pieschl et al., Citation2021). The 50% rating reflects complete uncertainty about which of the two respective belief statements on hemispheric dominance is true and, thus, assigning each of them a 50% confidence (“guessing”; Koriat, Citation2018; Pieschl et al., Citation2021). Because confidence ratings cannot be interpreted without considering the correctness of the forced-choice answer, we computed a confidence accuracy score (Fleming & Lau, Citation2014; Schraw, Citation2009). Confidence accuracy is a metacognitive measure reflecting the discrepancy between a person’s knowledge and their confidence in that knowledge (Barenberg & Dutke, Citation2013; Fleming & Lau, Citation2014; Schraw, Citation2009). For example, agreeing with the misconception and being highly confident in that belief results in low confidence accuracy (Fleming & Lau, Citation2014; Schraw, Citation2009).

We computed the confidence accuracy score as follows (cf. Schraw, Citation2009): For participants who chose the correct statement about hemispheric dominance, confidence accuracy was equal to the confidence judgment. For participants choosing the incorrect statement, confidence accuracy is 100 minus the confidence judgment value. This computation results in a scale ranging from 0 to 100, with low values indicating inappropriate confidence in a misconception (small confidence accuracy) and high values indicating appropriate confidence in a correct belief (high confidence accuracy).

Belief justification

In an open response task, we asked participants to write a short justification for why they thought that hemispheric dominance can or cannot explain individual differences in learning. On average, participants wrote 36 (SD = 24) words.

Procedure

The welcome page informed participants that the study aimed to investigate their beliefs about the role of hemispheric dominance in learning and that they were asked to read a short text about this topic. After giving informed consent, in a seriousness check (Aust et al., Citation2013), the participants answered whether they intended to complete the survey conscientiously or not (i.e., only wanting to browse it for curiosity). They then reported relevant demographic information (i.e., type of study program, study progress, gender). Next, participants indicated whether they believed in the importance of considering the role of hemispheric dominance in learning and assessed their confidence in their belief. Subsequently, reading goals were manipulated by instructing participants to read a text to receive either an explanation about the topic or for entertainment. This manipulation followed typical procedures in reading goal research (Latini et al., Citation2019). After having read either a traditional or a refutation text in the respective experimental conditions, participants reassessed their belief in the role of hemispheric dominance as well as their confidence in this belief. Finally, participants justified their judgment in an open response task.

To control for order effects, we randomized the order of agreement/confidence task and the open response task. Moreover, we examined whether participants remembered the instruction for their reading goal at the end of the questionnaire. We asked which of the two instructions they had received before and let them choose between the two original instructions (explanation vs. entertainment). Afterwards, we asked how attentively they had read the text (attentively and carefully or just skimmed the text). Overall, 74% of the participants remembered their reading goal instruction correctly, and 71% indicated attentive text reading. On average, participation took about 10 min (SD = 6).

Analyses

To predict the probability of belief change at t2 (H1a, b), we computed two hierarchical binary logistic regression models and compared them using a χ2-test (Field et al., Citation2012; Jaccard, Citation2001). In Model 1, text type and reading goals served as predictors of belief change. In Model 2, we added their interaction term. Note that because the coefficients of a binary logistic model with categorical predictors are conditioned on the other predictor variable being zero, the odds ratios cannot be interpreted as if they represent a nonconditioned main effect. Therefore, we followed Jaccard’s (Citation2001) recommendation to run Model 2 in four different versions, recoding the dummy variables for reading goal and text type to systematically vary the respective reference group. The tests of the interaction and of the overall model fit are not affected by this rescoring (Jaccard, Citation2001). Changes in participants’ confidence accuracy (H2a, b) were tested by a three-way mixed ANOVA with the between-participants factors text type and reading goal and the within-participants factor time.

In a further exploratory step, we analyzed participants’ written justifications of their beliefs to assess whether they still reported misconceptions after reading. For this purpose, we coded whether participants reported a misconception (code 0) or provided correct assumptions (code 1) in their essays about the topic. Some justifications could not be clearly classified and were not considered in the analysis (code NA). In addition to the text by Woolfolk (Citation2014), reviews of the myth of hemispheric dominance by De Bruyckere et al. (Citation2015), Holmes (Citation2016), and Lilienfeld et al. (Citation2011) served as the basis for assessing the correctness of the participants’ justifications. Texts were coded by two independent raters (initial Cohen’s Kappa = 0.63), and disagreements were resolved by discussion. Similar to the analysis of H1, we ran two hierarchical binary logistic regression models to predict the probability of correct justification and compared them with a χ2-test.

All quantitative analyses were conducted using R version 4.2.1. We used package rstatix (V. 0.7.2; Kassambara, Citation2023) for the ANOVA.

Results

Preliminary analyses

To rule out any impact of the participants’ characteristics on the results, we tested their distributions across experimental conditions. As can be expected per random assignment, χ2-tests and t-tests showed that text type groups did not differ significantly by type of teacher education programme (χ2(4) = 5.33, p = .255, V = 0.18), study degree (χ2(2) = 0.45, p = .798, V = 0.05), and study progress (t(150) = 0.23, p = .815, d = 0.04). The same was true for the reading goal groups: type of teacher education programme (χ2(4) = 5.34, p = .254, V = 0.18), study degree (χ2(2) = 1.53, p = .465, V = 0.10) and study progress (t(150) = 1.02, p = .311, d = 0.17).

We conducted a cognitive pretest using think-aloud protocols to examine the comprehensibility of the instructions and tasks. The participants did not express any problems. Preparatory analyses with the present data showed no effects of task order on belief change (χ2(1) = 0.09, p = .763, V = 0.02), confidence accuracy (t(166) = 0.36, p = .720, d = 0.06), or correctness of written justifications (χ2(2) = 2.60, p = .272, V = 0.13).

Effects on belief change

Descriptive statistics for the proportion of participants who changed their beliefs are reported in . Results from the logistic regression showed that, overall, Model 1 significantly predicted belief change (). Adding the interaction of text type x reading goal did not significantly improve the model fit, Δχ2(1) = 0.17, p =.683. Therefore, Model 1 is considered the final model. Coefficients for the four versions of Model 2 are available in online supplement S1. Results from Model 1 showed that, as hypothesized, text type was a significant predictor of belief change (H1a). The odds of participants changing their beliefs were 3.40 times higher when they had read a refutation text than when they had read a traditional text. In addition, there was an unexpected effect of reading goal that was not part of our hypotheses. Participants were 2.27 less likely to change their belief if they had read for explanation rather than for entertainment.Footnote1 However, since adding the interaction of text type x reading goal did not significantly improve the model fit, the expected interaction of text type x reading goal was not supported by the data (H1b). That is, the effect of the refutation text did not differ significantly between participants who had read for either explanation or for entertainment.

Table 1. Number and percentage of participants in each condition who changed their misconception to true belief from t1 to t2.

Table 2. Final logistic regression models of belief change and misconceptions in written justifications.

Effects on confidence accuracy

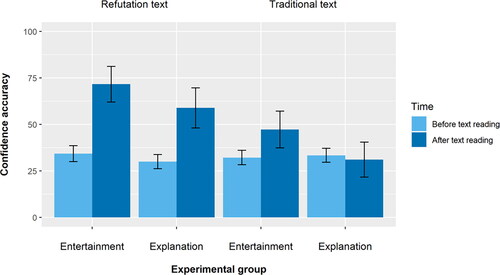

displays confidence accuracy before and after reading the text for each condition. Below, we present the findings on our main hypotheses. As expected, the three-way mixed ANOVAFootnote2 revealed a significant interaction of text type and time (H2a) (). We conducted Bonferroni-adjusted post-hoc tests that compared (a) the confidence accuracy of both refutation groups (refutation-entertainment and refutation-explanation) at t1 with both refutation groups at t2, and (b) the confidence accuracy of both traditional groups (traditional–entertainment and traditional–explanation) at t1 with both traditional groups at t2. These tests indicated that only participants who had read the refutation text showed a significant increase in confidence accuracy from t1 (M = 31.96, SD = 12.45) to t2 (M = 64.78, SD = 32.38), t(99.30) = 8.36, p <.001, d = 1.34 [0.99, 1.69]. By contrast, participants who had read the traditional text did not improve in their confidence accuracy from t1 (M = 32.75, SD = 12.56) to t2 (M = 39.53, SD = 33.08), t(114.37) = 1.82, p =.088, d = 0.26 [−0.04, 0.55]. However, in contrast to H2b, reading goals did not moderate this effect, as indicated by the statistically non-significant three-way interaction of text type, reading goal, and time.

Figure 1. Confidence accuracy before and after reading by condition. Note. Mean confidence accuracy scores before and after reading the text are shown for different text types and reading goals. Small confidence accuracy values indicate inappropriate confidence in a misconception, and high values indicate appropriate confidence in a correct belief. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals.

Table 3. Three-way ANOVA statistics for confidence accuracy.

Though not part of our hypotheses, the data showed an interaction of reading goal and time (). We conducted further Bonferroni tests that compared the confidence accuracy of both entertainment groups (refutation-entertainment and traditional-entertainment) with both explanation groups (refutation–explanation and traditional–explanation) at both measurement time points. Whereas the entertainment group (M = 33.09, SD = 12.72) and explanation group (M = 31.69, SD = 12.27) did not differ at t1 regarding confidence accuracy (t(164.15) = 0.73, p =.470, d = 0.11 [−0.19, 0.42]), participants who read for entertainment (M = 57.84, SD = 33.56) showed higher confidence accuracy at t2 than participants who read for explanation (M = 44.82, SD = 35.40; t(165.86) = 2.45, p =.016). However, the effect size was small: d = 0.38 [0.07, 0.68].Footnote3

Effects of mentioning misconceptions in written justifications (exploratory)

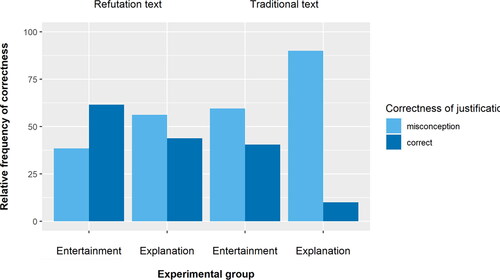

Findings from the qualitative analysis of the written justifications underscored the quantitative results. Overall, N = 147 participants provided justifications for their belief about hemispheric dominance at t2. Out of all justifications, 80 texts (54%) still contained a misconception, 50 (34%) were correct, and 17 (12%) texts could not be evaluated conclusively (e.g., because justifications were too vague to evaluate the correctness). Comparing participants’ beliefs after the intervention with the correctness of their justifications, we found that 22% of the participants who had chosen the correct statement in t2 still reported misconceptions regarding hemispheric dominance in their open response. Conversely, out of the participants who had shown a misconception in t2, 7% wrote justifications with correct explanations about hemispheric dominance. presents exemplary quotations for each code. displays how misconceptions and correct answers in the justifications are distributed in the experimental conditions.

Figure 2. Relative frequency of misconceptions and correct answers in participants’ written justifications.

Table 4. Exemplary quotations from participants’ justifications.

The results of the logistic regression showed that, overall, Model 1 significantly predicted the correctness of the belief justification (). Adding the interaction of text type x reading goal did not significantly improve the model fit, Δχ2(1) = 1.65, p = .199 (see S3). Therefore, we present the results of Model 1 (). Text type predicted the likelihood of a correct justification. The odds of writing a correct justification were 3.57 times higher when participants had read a refutation text as compared to a traditional text. Again, there was an unexpected effect of reading goals that was not part of our hypotheses. Participants were 3.23 less likely to change their belief if they had read for explanation rather than for entertainment. Again, adding the interaction of text type x reading goal did not significantly improve the model fit. Consequently, the expected interaction between text type and reading goal was not supported by the data. That is, the effect of the refutation text did not differ significantly between participants who had read either for explanation or for entertainment.

In sum, the qualitative data partially supported the quantitative results: Participants were more likely to write correct justifications after reading a refutation text and when reading for entertainment. However, reading goals did not moderate the refutation effect, as indicated by the nonsignificant model comparison.Footnote4

Discussion

Refutation texts have been found effective in reducing misconceptions in several domains, but so far, it remains an open question which factors explain the considerable differences found in these effects (Tippett, Citation2010; Trevors & Muis, Citation2015; Zengilowski et al., Citation2021). The present study addressed this research gap by examining whether reading goals moderate the effect of refutation texts when countering preservice teachers’ misconceptions about educational myths. To study conceptual change in participants, we looked at both belief revision and change in confidence accuracy and analyzed indications of misconceptions in their written belief justifications. There were two main findings: First, our data replicate prior results that refutation texts can have strong effects on conceptual change (Kendeou et al., Citation2014; Tippett, Citation2010; Zengilowski et al., Citation2021); and second, contrary to expectations, we found no indication that participants’ reading goals affected the effectiveness of refutation texts on initiating conceptual change.

Refutation texts change misconceptions successfully…

As hypothesized in H1a, we found that preservice teachers holding misconceptions about hemispheric dominance were more likely to change their beliefs after reading a refutation text compared to a traditional textbook. The same result pattern pertains to a change in confidence accuracy. According to H2a, preservice teachers who read a refutation text became much better at assessing the correctness of their belief. That is, even if participants retained their incorrect beliefs after having read conflicting information, they were less certain in this belief after reading a refutation text. Hence, the refutation text did a better job of at least shaking their misconceptions and, possibly, breaking the ground for later conceptual change. Conversely, preservice teachers who changed their false beliefs were also more confident in the correctness of their true beliefs in the refutation text condition. Hence, in accordance with the KReC framework, the refutation texts seem to have succeeded in making the correct information win the competition of activation, thus facilitating conceptual change. The refutation text elicits the coactivation of both the misconception and the correct information while unmasking the misconception and enhancing the activation of the newly learned correct information (Kendeou & O'Brien, Citation2014). This should not be taken as discrediting or discouraging the use of textbooks, which can have an important curricular function. However, faculty should bear in mind that textbook readings may be insufficient to address misconceptions held by students.

This pattern of results was reflected in the participants’ written justifications, but only after reading a refutation text to get an explanation. In this experimental group, preservice teachers were mostly able to justify their beliefs without drawing on false or questionable assumptions. In contrast, preservice teachers who read a traditional textbook to obtain an explanation retained more of their incorrect prior assumptions, even though the text also provided information disproving the myth. However, more than 20% of the participants who indicated that they had changed their misconceptions still drew on false explanations in their justifications. This seeming inconsistency is expected, as according to the KReC framework, old incorrect information and new correct information are coactivated. Therefore, although the new correct assumptions might win the competition of activation, the old assumptions may still remain in a person’s belief system (Kendeou & O'Brien, Citation2014; cf. Chi, Citation2008).

… Regardless of reading goal

Concerning the supposed moderating role of reading goals, contrary to expectations, we found no evidence that reading for entertainment versus reading for obtaining an explanation made a difference for the refutation effect. The respective interaction effects were consistently non-significant for all investigated outcomes (i.e., belief change, confidence assessment, and correctness of written justifications), rejecting H1b and H2b. This result is surprising, given the emphasis on the importance of reading goals in the literature on text processing (Chinn et al., Citation2014; Linderholm, Citation2006; McCrudden & Schraw, Citation2007), begging the question for putative reasons. We would like to offer three potential explanations. First, of course, it is conceivable that the stated moderation hypothesis is truly false: even though reading goals may affect text processing in general (McCrudden & Schraw, Citation2007), they may be of less impact for whether and how refutation texts trigger knowledge revision processes. Notwithstanding this possibility, conceptual change requires motivation and effort on behalf of learners (Sinatra & Mason, Citation2008) and, thus, it seems unlikely that reading goals are completely irrelevant. Hence, it may be worthwhile to consider alternative reasons.

A second potential explanation may lie in the specific selection of reading goals investigated in this study (i.e., learning vs. entertainment). Even though these goals have been contrasted frequently in previous research (Latini et al., Citation2019; Linderholm & van den Broek, Citation2002; Narvaez et al., Citation1999; van den Broek et al., Citation2001), the differences they imply for text processing might be of less relevance for how a refutation text induces a cognitive conflict in the reader. These reading goals may have left participants with enough freedom to avoid cognitive conflict. Potentially, other goals—such as finding out what is most likely true regarding an issue—might be more prone to induce a cognitive conflict through refutation texts. Therefore, future studies might instruct other reading goals and potentially assess participants’ experiences of cognitive conflict as a mediating variable.

Third, although research has shown that reading goals are sensitive to task instructions (Maier & Richter, Citation2013; McCrudden & Schraw, Citation2007), there is no guarantee that participants adhered to their instructed goals throughout the course of the experiment. Even though our manipulation check showed that most participants remembered the instructed goal correctly at the end of the experiment, their reading goals might have shifted during the experiment (cf. Chinn et al., Citation2014; van den Broek et al., Citation2011). Possibly, interaction with the contents of the refutation text might have led the participants to change the instructed reading goal (van den Broek et al., Citation2011). As aforementioned, refutation texts are designed to elicit cognitive conflict via the statement and direct refutation of a misconception (Sinatra & Pintrich, Citation2003; Tippett, Citation2010). They may induce the goal to find an explanation for this conflict, thus overriding a previously instructed reading goal, such as entertainment. Hence, investigating potential shifts in readers’ predominant reading goals, though challenging, seems worthwhile in its own right. In the present study, we deliberately omitted adding another manipulation check question directly after text reading, because such intermittent questioning may interfere with the studied treatment effect (Hauser et al., Citation2018).

In summary, even though the stated moderation hypotheses found no empirical support, we maintain that the potential role of reading goals for refutation text processing and its effects on conceptual change warrant further investigation—because of their mentioned central role in reading research—at the least (Britt et al., Citation2014; McCrudden & Schraw, Citation2007). Similarly, the identified exploratory reading goal effects hint that reading goals may indeed influence conceptual change, even though this study revealed no interaction with text type. As suggested above, future research should examine the role of further reading goals, such as preparing for an exam or reading goals that focus on finding the truth. These goals may motivate readers to search for true knowledge and thus provoke a cognitive conflict when confronted with belief-disconfirming evidence. Future experiments could also test the effectiveness of more intensive reading goal interventions in which learners have a more active part in which they are more encouraged to actively apply the reading goal, for example, through an additional writing task. Moreover, future studies on refutation texts should systematically instruct reading goals for participants, for example, by setting fixed reading goals for everyone. Doing so could contribute to reducing the extraneous variance introduced by potential heterogeneity in the goals with which participants may approach an experimental reading task. Thus, such instructions may advance the causal attribution of the resulting effects to the refutation manipulation. As discussed above, doing so has frequently been omitted from refutation text research. Instructing specific goals, first, helps standardize the purpose with which participants approach the text. Second, doing so would also enable future meta-analyses on refutation texts to use this variable as a moderator of effect heterogeneity.

(Why) is conceptual change more likely when reading for entertainment?

One implication of our results that may be cause for concern is that the condition that best resembled the typical learning scenario in teacher education consistently showed the most disappointing results: Preservice teachers with the goal of finding an explanation about the role of hemispheric dominance were least likely to change their misconceptions. This is also related to the surprising effects showing that reading for entertainment was more likely to induce conceptual change than reading for learning. Although this exploratory finding needs to be replicated, we would like to address some potential reasons. One explanation could be that instructing participants to read for an explanation might have set overly high expectations in some participants regarding the texts’ comprehensiveness. Even though the text’s explanative quality was good in the sense that it covered the most important facts and arguments, these participants’ expectations might have been disappointed given its scope. Consequently, participants might not have perceived the text as convincing enough to change their beliefs. A second potential explanation could be that participants might have perceived the instruction to read for an explanation as an illegitimate attempt at persuasion, especially when the text went against their previous belief, thus raising reactance. Indeed, research shows that people frequently react defensively when facing belief-disconfirming information (Chinn & Brewer, Citation1993; Futterleib et al., Citation2022; Lewandowsky et al., Citation2012). Reading for entertainment, on the other hand, may trigger a new perspective on the text that makes the reader more open to new, even belief-disconfirming, information. Third, the instruction to read for entertainment might have been more successful for conceptual change because of the context we asked the participants to imagine—that is—finding the text when scrolling through their social media account for entertainment. There is evidence that consumers regard information on social media as especially trustworthy and convincing because it was shared by someone they can relate to (Anspach & Carlson, Citation2020; Sterrett et al., Citation2019; Wagner & Boczkowski, Citation2019). To our knowledge, so far, there is no evidence of whether such findings apply to preservice teachers’ information behavior regarding educational topics. However, there is evidence that they tend to prefer experiential over scientifically based knowledge (Bråten & Ferguson, Citation2015). Nevertheless, from the perspective of teacher education, it would be disturbing if they rated information from social media as more trustworthy than information from study lectures.

Limitations and conclusion

Beyond the points mentioned above, we would like to acknowledge several limitations of our study. First, as our text material covered only one topic, the results of the study cannot be generalized to other educational myths not related to neuroscience. Neuromyths, such as the role of hemispheric dominance in learning, often have a particularly scientific appearance (OECD, Citation2007). This could have influenced participants’ expectations regarding the text, especially in combination with an explanation-reading goal, as outlined above. Hence, it could be worthwhile to reexamine the influence of reading goals on the refutation effect with other educational myths not related to neuroscience (De Bruyckere et al., Citation2015). Second, only 74% of the participants remembered their reading goal instruction. One potential explanation may lie in the relatively brief nature of the intervention, which aligns with existing reading goal research. Another potential reason is that the respective question was placed at the end of the survey, so that the intermittent tasks the participants engaged in (i.e., the questionnaire and the essay task) might have interfered with the recall. Third, the interrater reliability for coding participants’ justifications was low. A conservative approach to resolving disagreements resulted in 12% of the texts not being included in the analyses. It is conceivable that the calculated effects therefore tended to be smaller. However, we consider this unlikely because the results of the justification analyses are consistent with the results of the other two measures (i.e., belief change and confidence accuracy). Finally, even though we found a large refutation effect, we do not know how sustainable the resulting belief change is. However, previous studies have observed that the refutation effect on conceptual change can also persist after weeks, even though long-term effects tend to be smaller and diminishing (Kowalski & Taylor, Citation2017; Lithander et al., Citation2021; Rousseau, Citation2021).

Notwithstanding these limitations, we believe that this study contributes to recent research increasingly clarifying the boundary conditions of the effectiveness of refutation texts (Tippett, Citation2010; Zengilowski et al., Citation2021). Based on our and others’ findings, we recommend that teacher educators make more use of refutation texts to address their students’ misconceptions. Despite the observed differences in effect sizes, it seems safe to say that refutation texts are an effective tool for debunking misconceptions. Nevertheless, the question of potential factors that influence whether a refutation intervention is effective remains unanswered and warrants further investigation.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (197.8 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (549.5 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (198.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

This study was registered with the OSF. The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the OSF.

Notes

1 When considering only participants who correctly remembered their reading goal, the results were consistent in terms of the direction of the effects but slightly different in terms of statistical significance (S2). We found an effect of text type on belief change but there was no effect of reading goals on belief change. These differences are likely due to the reduced power of the smaller sample.

2 Because normality and homoscedasticity assumptions for ANOVA were not met, we performed an additional robust ANOVA to check the robustness of our results. Results from the robust ANOVA did not differ substantially from the ANOVA reported here (see OSF for analyses and results).

3 When considering only participants who correctly remembered their reading goal, we found no interaction of reading goal and time (S2). This is probably due to the reduced statistical power.

4 When considering only participants who correctly remembered their reading goal, the results were similar (S2).

References

- Aguilar, S. J., Polikoff, M. S., & Sinatra, G. M. (2019). Refutation texts: A new approach to changing public misconceptions about education policy. Educational Researcher, 48(5), 263–272. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X19849416

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/index.html.

- Anspach, N. M., & Carlson, T. N. (2020). What to believe? Social media commentary and belief in misinformation. Political Behavior, 42(3), 697–718. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-9515-z

- Ariasi, N., & Mason, L. (2014). From covert processes to overt outcomes of refutation text reading: The interplay of science text structure and working memory capacity through eye fixations. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 12(3), 493–523. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-013-9494-9

- Asberger, J., Thomm, E., & Bauer, J. (2021). On predictors of misconceptions about educational topics: A case of topic specificity. PLOS One, 16(12), e0259878. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259878

- Aust, F., Diedenhofen, B., Ullrich, S., & Musch, J. (2013). Seriousness checks are useful to improve data validity in online research. Behavior Research Methods, 45(2), 527–535. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-012-0265-2

- Barenberg, J., & Dutke, S. (2013). Metacognitive monitoring in university classes: Anticipating a graded vs. a pass-fail test affects monitoring accuracy. Metacognition and Learning, 8(2), 121–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-013-9098-3

- Bensley, D. A., Lilienfeld, S. O., & Powell, L. A. (2014). A new measure of psychological misconceptions: Relations with academic background, critical thinking, and acceptance of paranormal and pseudoscientific claims. Learning and Individual Differences, 36, 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2014.07.009

- Blanchette Sarrasin, J., Riopel, M., & Masson, S. (2019). Neuromyths and their origin among teachers in Quebec. Mind, Brain, and Education, 13(2), 100–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/mbe.12193

- Bråten, I., & Ferguson, L. E. (2015). Beliefs about sources of knowledge predict motivation for learning in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 50, 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.04.003

- Bråten, I., & Strømsø, H. I. (2009). Effects of task instruction and personal epistemology on the understanding of multiple texts about climate change. Discourse Processes, 47(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/01638530902959646

- Britt, M. A., Durik, A., & Rouet, J. F. (2022). Reading contexts, goals, and decisions: Text comprehension as a situated activity. Discourse Processes, 59(5–6), 361–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2022.2068345

- Britt, M. A., Richter, T., & Rouet, J. F. (2014). Scientific literacy: The role of goal-directed reading and evaluation in understanding scientific information. Educational Psychologist, 49(2), 104–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2014.916217

- Broughton, S. H., Sinatra, G. M., & Nussbaum, E. M. (2011). “Pluto has been a planet my whole life!” Emotions, attitudes, and conceptual change in elementary students’ learning about Pluto’s reclassification. Research in Science Education, 43(2), 529–550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-011-9274-x

- Butterfuss, R., & Kendeou, P. (2020). Reducing interference from misconceptions: The role of inhibition in knowledge revision. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(4), 782–794. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000385

- Chi, M. T. H. (2008). Three types of conceptual change: Belief revision, mental model transformation, and categorical shift. In S. Vosniadou (Ed.), Handbook of research on conceptual change (pp. 61–82). Erlbaum.

- Chinn, C. A., & Brewer, W. F. (1993). The role of anomalous data in knowledge acquisition: A theoretical framework and implications for science instruction. Review of Educational Research, 63(1), 1–49. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543063001001

- Chinn, C. A., Rinehart, R. W., & Buckland, L. A. (2014). Epistemic cognition and evaluating information: Applying the AIR model of epistemic cognition. In D. N. Rapp & J. L. G. Braasch (Eds.), Processing inaccurate information: Theoretical and applied perspectives from cognitive science and the educational sciences (pp. 425–453). MIT Press.

- De Bruyckere, P., Kirschner, P. A., & Hulshof, C. D. (2015). Urban myths about learning and education. Academic Press.

- Deibl, I., & Zumbach, J. (2023). Pre-service teachers’ beliefs about neuroscience and education—do freshmen and advanced students differ in their ability to identify myths? Psychology Learning & Teaching, 22(1), 74–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475725722114664

- Dekker, S., Lee, N. C., Howard-Jones, P., & Jolles, J. (2012). Neuromyths in education: Prevalence and predictors of misconceptions among teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 429. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00429

- Dersch, A.-S., Renkl, A., & Eitel, A. (2022). Personalized refutation texts best stimulate teachers’ conceptual change about multimedia learning. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 38(4), 977–992. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12671

- Ecker, U. K. H., Lewandowsky, S., Cook, J., Schmid, P., Fazio, L. K., Brashier, N., Kendeou, P., Vraga, E. K., & Amazeen, M. A. (2022). The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1(1), 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-021-00006-y

- Ferrero, M., Garaizar, P., & Vadillo, M. A. (2016). Neuromyths in education: Prevalence among Spanish teachers and an exploration of cross-cultural variation. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10, 496. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2016.00496/full https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2016.00496

- Ferrero, M., Konstantinidis, E., & Vadillo, M. A. (2020). An attempt to correct erroneous ideas among teacher education students: The effectiveness of refutation texts. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 577738. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577738

- Field, A., Miles, J., & Field, Z. (2012). Discovering statistics using R. Sage publications.

- Fleming, S. M., & Lau, H. C. (2014). How to measure metacognition. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 443. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00443/full https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00443

- Futterleib, H., Thomm, E., & Bauer, J. (2022). The scientific impotence excuse in education—disentangling potency and pertinence assessments of educational research. Frontiers in Education, 7, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.1006766

- Galesic, M. (2006). Dropouts on the web: Effects of interest and burden experienced during an online survey. Journal of Official Statistics, 22(2), 313–328.

- Grospietsch, F., & Lins, I. (2021). Review on the prevalence and persistence of neuromyths in education—where we stand and what is still needed. Frontiers in Education, 6, 665752. https://doi.org/10.17170/kobra-202110014837

- Guzzetti, B. J., Snyder, T. E., Glass, G. V., & Gamas, W. S. (1993). Promoting conceptual change in science: A comparative meta-analysis of instructional interventions from reading education and science education. Reading Research Quarterly, 28(2), 116–159. https://doi.org/10.2307/747886

- Hauser, D. J., Ellsworth, P. C., & Gonzalez, R. (2018). Are manipulation checks necessary? Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 998. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00998

- Holmes, J. D. (2016). Great myths of education and learning. John Wiley & Sons.

- Hughes, B., Sullivan, K. A., & Gilmore, L. (2021). Neuromyths about learning: Future directions from a critical review of a decade of research in school education. Prospects, 52(1–2), 189–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-021-09567-5

- Hughes, S., Lyddy, F., & Lambe, S. (2013). Misconceptions about psychological science: A review. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 12(1), 20–31. https://doi.org/10.2304/plat.2013.12.1.20

- Jaccard, J. (2001). Interaction effects in logistic regression, Quantitative applications in the social sciences (vol. 135). SAGE.

- Kassambara, A. (2023). Package ‘rstatix’ (version 0.7.2) [R package]. https://rpkgs.datanovia.com/rstatix/.

- Kendeou, P., Butterfuss, R., Kim, J., & Van Boekel, M. (2019). Knowledge revision through the lenses of the three-pronged approach. Memory & Cognition, 47(1), 33–46. https://link.springer.com/article/10.3758/s13421-018-0848-y https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-018-0848-y

- Kendeou, P., & O'Brien, E. J. (2014). The Knowledge Revision Components (KReC) framework: Processes and mechanisms. In D. N. Rapp & J. L. G. Braasch (Eds.), Processing inaccurate information: Theoretical and applied perspectives from cognitive science and the educational sciences (pp. 353–377). The MIT Press.

- Kendeou, P., Robinson, D. H., & McCrudden, M. T. (Eds.). (2019). Misinformation and fake news in education. IAP.

- Kendeou, P., Walsh, E. K., Smith, E. R., & O'Brien, E. J. (2014). Knowledge revision processes in refutation texts. Discourse Processes, 51(5–6), 374–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2014.913961

- Kendeou, P., & van den Broek, P. (2007). The effects of prior knowledge and text structure on comprehension processes during reading of scientific texts. Memory & Cognition, 35(7), 1567–1577. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193491

- Koriat, A. (2018). When reality is out of focus: Can people tell whether their beliefs and judgments are correct or wrong? Journal of Experimental Psychology-General, 147(5), 613–631. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000397

- Kowalski, P., & Taylor, A. K. (2009). The effect of refuting misconceptions in the introductory psychology class. Teaching of Psychology, 36(3), 153–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/00986280902959986

- Kowalski, P., & Taylor, A. K. (2017). Reducing students’ misconceptions with refutational teaching: For long-term retention, comprehension matters. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 3(2), 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/stl0000082

- Krammer, G., Vogel, S. E., & Grabner, R. H. (2020). Believing in neuromyths makes neither a bad nor good student‐teacher: The relationship between neuromyths and academic achievement in teacher education. Mind, Brain, and Education, 15(1), 54–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/mbe.12266

- Lassonde, K. A., Kendeou, P., & O'Brien, E. J. (2016). Refutation texts: Overcoming psychology misconceptions that are resistant to change. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 2(1), 62–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/stl0000054

- Latini, N., Bråten, I., Anmarkrud, Ø., & Salmerón, L. (2019). Investigating effects of reading medium and reading purpose on behavioral engagement and textual integration in a multiple text context. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 59, 101797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.101797

- Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and its correction: Continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13(3), 106–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612451018

- Lilienfeld, S. O., Lynn, S. J., Ruscio, J., & Beyerstein, B. L. (2011). 50 Great myths of popular psychology: Shattering widespread misconceptions about human behavior. John Wiley & Sons.

- Linderholm, T. (2006). Reading with purpose. Journal of College Reading and Learning, 36(2), 70–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790195.2006.10850189

- Linderholm, T., & van den Broek, P. (2002). The effects of reading purpose and working memory capacity on the processing of expository text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(4), 778–784. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.94.4.778

- Lithander, M. P., Geraci, L., Karaca, M., & Rydberg, J. (2021). Correcting neuromyths: A comparison of different types of refutations. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 10(4), 577–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2021.03.006

- Maier, J., & Richter, T. (2013). How nonexperts understand conflicting information on social science issues. Journal of Media Psychology, 25(1), 14–26. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000078

- Mason, L., Gava, M., & Boldrin, A. (2008). On warm conceptual change: The interplay of text, epistemological beliefs, and topic interest. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(2), 291–309. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.100.2.291

- McCrudden, M. T. (2012). Readers’ use of online discrepancy resolution strategies. Discourse Processes, 49(2), 107–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2011.647618

- McCrudden, M. T., & Schraw, G. (2007). Relevance and goal-focusing in text processing. Educational Psychology Review, 19(2), 113–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-006-9010-7

- Menz, C., Spinath, B., Hendriks, F., & Seifried, E. (2024). Reducing educational psychological misconceptions: How effective are standard lectures, refutation lectures, and instruction in information evaluation strategies? Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 10(1), 56–75. https://doi.org/10.1037/stl0000269

- Menz, C., Spinath, B., & Seifried, E. (2020). Misconceptions die hard: Prevalence and reduction of wrong beliefs in topics from educational psychology among preservice teachers. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 36(2), 477–494. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-020-00474-5

- Narvaez, D., van den Broek, P., & Ruiz, A. B. (1999). The influence of reading purpose on inference generation and comprehension in reading. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(3), 488–496. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.91.3.488

- OECD. (2007). Understanding the brain: The birth of a learning science. OECD Publications.

- Pieschl, S., Budd, J., Thomm, E., & Archer, J. (2021). Effects of raising student teachers’ metacognitive awareness of their educational psychological misconceptions. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 20(2), 214–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/147572572199622

- Prinz, A., Golke, S., & Wittwer, J. (2019). Refutation texts compensate for detrimental effects of misconceptions on comprehension and metacomprehension accuracy and support transfer. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(6), 957–981. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000329

- Prinz, A., Golke, S., & Wittwer, J. (2021). Counteracting detrimental effects of misconceptions on learning and metacomprehension accuracy: The utility of refutation texts and think sheets. Instructional Science, 49(2), 165–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-021-09535-8

- Prinz, A., Kollmer, J., Flick, L., Renkl, A., & Eitel, A. (2022). Refuting student teachers’ misconceptions about multimedia learning. Instructional Science, 50(1), 89–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-021-09568-z

- Roozenbeek, J., Culloty, E., & Suiter, J. (2023). Countering misinformation: Evidence, knowledge gaps, and implications of current interventions. European Psychologist, 28(3), 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000492

- Rouet, J. F., Britt, M. A., & Durik, A. M. (2017). RESOLV: Readers’ representation of reading contexts and tasks. Educational Psychologist, 52(3), 200–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2017.1329015

- Rousseau, L. (2021). Interventions to dispel neuromyths in educational settings—a review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 719692. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.719692

- Schraw, G. (2009). A conceptual analysis of five measures of metacognitive monitoring. Metacognition and Learning, 4(1), 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-008-9031-3

- Sinatra, G. M., & Jacobson, N. (2019). Zombie concepts in education: Why they won’t die and why you can’t kill them. In P. Kendeou, D. H. Robinson & M.T. McCrudden (Eds.), Misinformation and fake news in education (pp. 7–27). IAP.

- Sinatra, G. M., & Mason, L. (2008). Beyond knowledge: Learner characteristics influencing conceptual change. In S. Vosniadou (Ed.), International handbook of research on conceptual change (pp. 377–394). Routledge.

- Sinatra, G. M., & Pintrich, P. R. (2003). The role of intentions in conceptual change learning. In G. M. Sinatra & P. R. Pintrich (Eds.), Intentional conceptual change (pp. 10–26). Routledge.

- Södervik, I., Virtanen, V., & Mikkilä-Erdmann, M. (2015). Challenges in understanding photosynthesis in a university introductory biosciences class. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 13(4), 733–750. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-014-9571-8

- Sterrett, D., Malato, D., Benz, J., Kantor, L., Tompson, T., Rosenstiel, T., Sonderman, J., & Loker, K. (2019). Who shared it? Deciding what news to trust on social media. Digital Journalism, 7(6), 783–801. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1623702

- Taylor, A. K., & Kowalski, P. (2004). Naïve psychological science: The prevalence, strength, and sources of misconceptions. The Psychological Record, 54(1), 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03395459

- Taylor, A. K., & Kowalski, P. (2012). Students’ misconceptions in psychology: How you ask matters… sometimes. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 12(3), 62–77. https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/josotl/article/view/2150.

- Thacker, I., Sinatra, G. M., Muis, K. R., Danielson, R. W., Pekrun, R., Winne, P. H., & Chevrier, M. (2020). Using persuasive refutation texts to prompt attitudinal and conceptual change. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(6), 1085–1099. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000434

- Thomm, E., Gold, B., Betsch, T., & Bauer, J. (2021). When preservice teachers’ prior beliefs contradict evidence from educational research. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(3), 1055–1072. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12407

- Tippett, C. D. (2010). Refutation text in science education: A review of two decades of research. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 8(6), 951–970. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-010-9203-x

- Trevors, G., & Kendeou, P. (2020). The effects of positive and negative emotional text content on knowledge revision. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 73(9), 1326–1339. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747021820913816

- Trevors, G., & Muis, K. R. (2015). Effects of text structure, reading goals and epistemic beliefs on conceptual change. Journal of Research in Reading, 38(4), 361–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9817.12031

- van den Broek, P., Bohn-Gettler, C. M., Kendeou, P., Carlson, S., & White, M. J. (2011). When a reader meets a text: The role of standards of coherence in reading comprehension. In M. T. McCrudden, J. P. Magliano & G. Schraw (Eds.), Text relevance and learning from text (pp. 123–139). IAP.

- van den Broek, P., Lorch, R. F., Linderholm, T., & Gustafson, M. (2001). The effects of readers’ goals on inference generation and memory for texts. Memory & Cognition, 29(8), 1081–1087. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03206376

- Vosniadou, S. (2013). International handbook of conceptual change (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Wagner, M. C., & Boczkowski, P. J. (2019). The reception of fake news: The interpretations and practices that shape the consumption of perceived misinformation. Digital Journalism, 7(7), 870–885. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1653208

- Woolfolk, A. (2014). Pädagogische Psychologie [Educational psychology] (12th ed.). Pearson.

- Yeari, M., van den Broek, P., & Oudega, M. (2015). Processing and memory of central versus peripheral information as a function of reading goals: Evidence from eye-movements. Reading and Writing, 28(8), 1071–1097. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-015-9561-4

- Zengilowski, A., Schuetze, B. A., Nash, B. L., & Schallert, D. L. (2021). A critical review of the refutation text literature: Methodological confounds, theoretical problems, and possible solutions. Educational Psychologist, 56(3), 175–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2020.1861948