ABSTRACT

This exploratory study present findings from semi-structured interviews with 15 Norwegian school principals elaborating on their experiences and learning from the school closures, transition to digital education, and educational leadership in the first six months of the pandemic. Three main themes emerged from the interviews: (1) “We took a quantum leap into the digital world” addressing how the school principals supported and experienced a rapid transformation to digital education; (2) “We tried to be close, even if we could not be” elaborating on worries regarding teachers and children with special needs; and (3) “We had to adjust” elaborating on the unpredictable and constantly changing nature of the situation. These themes are detailed and discussed in the context of research in crisis management, organizational change, role requirements, and leadership responsibilities. In closing, we discuss how the transformative experiences from the pandemic may have implications for educational leadership in future crisis situations.

Introduction

School principals are used to dealing with minor crises, conflicts, daily hassles, and frustration among students, parents, or their own staff. Still, the Covid-19 pandemic was very different, and most school principals have limited experience of handling a protracted and complex crisis (Varela & Fedynich, Citation2020). After the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 a pandemic on 11 March 2020, the usual educational routines, plans, and processes were abruptly challenged and replaced by uncertainty. Schools had to implement new procedures to minimize the risk of infection and ensure safe working practices for students and staff (Bailey & Breslin, Citation2021). When schools closed a rapid transition to digital education took place in Norway and other European countries (Taglietti et al., Citation2021).

The school system is a crucial institution not only for learning and education; it also represents a vital part of modern society (O’Connell & Clarke, Citation2020). In combating the virus, the educational sector played a major role in upholding a sense of normalcy and care for children and families during the pandemic. Still, there were few standard operational procedures on how to manage the schools during a pandemic. School principals had to improvise and find their way with little or no guidance. Previous research on leadership during crises in the educational sector, have mostly focused on school principals’ reactions to acute crisis situations, such as school violence (Pepper et al., Citation2010). Since the literature on crisis management in schools is relatively sparse, we approached the subject with two relatively open questions: How did school principals in Norway experience the pandemic and what were the most significant lessons learned?

The Disruptive Effects of the Pandemic

According to the Education Act, all children in Norway have an obligation and a right to receive ten years of primary school education from the age of six years (Education Act, Citation1998, § 2-1). When the Norwegian government abruptly decided to close 2,500 schools all over Norway in March 2020 to limit the spread of the virus, this decision resulted in more than 600,000 primary school students being transferred to an improvised digital education situation at home (Statistics Norway, Citation2020). In late April, the government decided that the first to fourth grades could return to their schools and, two weeks later, all students were back in their primary schools. In later stages of the pandemic, infection rates and virus mutations resulted in multiple local school closures (Government, Citation2021).

During the pandemic, the school principals were tasked with the challenging responsibility of balancing the students’ academic, social, emotional, and physical needs in response to the health concerns, expectations, and needs of teachers, school authorities, parents, and local stakeholders (Varela & Fedynich, Citation2020). The school closures during the pandemic presented a crisis that had unforeseen consequences when decisions had to be made under conditions of uncertainty and time pressure.

In previous research, Stevens (Citation2004) noted that it is particularly demanding to implement and preserve fundamental structural changes to the school organization. The radical changes in organizational processes and procedures during the pandemic therefore present a rare opportunity to investigate radical educational change and the school principal’s response to the unfolding crisis.

In connection with organizational crises, management is assumed to be crucial to the immediate outcome and long-term viability of the organization (James et al., Citation2011). According to Boin et al. (Citation2013), a comprehensive framework for crisis management depends on several factors. To begin with, an early recognition of the situation and a collective understanding of the nature of the crisis and its potential consequences are crucial to correctly assess the situation. Other critical leadership skills include vertical and horizontal coordination, monitoring of the situation, and communicating and interpreting the situation to increase organizational resilience efforts to manage the crisis (Boin et al., Citation2013).

The pandemic redefined educational processes to emphasize more adaptive and distributed leadership structures based on mutual trust to support individual and organizational resilience (Fernandez & Shaw, Citation2020). Many school principals were left to navigate between responsible guidance, swift decisions, and the need to stay vigilant in a constantly changing environment (Netolicky, Citation2020). The educational system was hardly prepared to face the disruptive effects of the pandemic. Limited resources and an increased demand for high quality distance learning presented significant challenges (Varela & Fedynich, Citation2020). A more effective use of staff skills and an increased need to exercise more emotional leadership emerged as two significant factors (Beauchamp et al., Citation2021). During a protracted crisis there is a significant risk that the long-term strain may exceed individual capacity and available job resources (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2017). In addition, the risk of role overload and work–family conflicts due to working from home emerged as a risk factor for burnout and exhaustion during the pandemic (Kniffin et al., Citation2021).

According to Smawfield (Citation2013), there is a need to gain more empirical knowledge on how the school and educational sector responds to crisis situations, and how school principals cope with protracted crisis situations. In this exploratory study we address this need by exploring how school principals responded to the pandemic and how it shaped and transformed the educational processes and their leadership practices.

Method

Research Design

The study applied a phenomenological hermeneutic design to understand the challenges and lessons learned from the school principals’ own descriptions of the world as it was experienced by them during the pandemic (James et al., Citation2011). The outcome of the research process rests on an iterative process between the school principals’ expressed experiences and the researchers’ interpretations. To clarify and disclose our prior understanding, a brief research proposal was submitted to the Norwegian Center for Research Data (NSD) as part of the approval process. In the proposal we assumed that the school principals would experience emotional stress and conflicts associated with priorities and difficult decisions. We also expected them to be quite well integrated into the local community processes regarding educational issues and challenges during the pandemic. In the analytical process we confronted and modified our own preunderstanding based on the qualitative inquiry until we reached a consensus on a new understanding (Kvale & Brinkmann, Citation2009).

Participants

The study sample consisted of 15 school principals (4 male and 11 female) from primary schools in different geographical areas in the western, eastern, and southern parts of Norway. The school principals were recruited using a purposeful sampling approach to ensure variation in geographic location and school size. All schools in our sample were public schools that accepted children from a defined school district. In general, the 15 schools were quite typical for Norwegian primary schools, with students from diverse socio-economic backgrounds. Following an initial e-mail contact, the principals were approached to obtain an informed consent and decide on a suitable time for the interview. The main reason for declining to take part in the study was time pressure, since the pandemic was still a very time-consuming part of their daily agenda. All principals who participated had extensive experience as teachers and had, on average, served in their current role for 5.5 years before the pandemic. School size varied from 240 to 625 students, and the principals supervised a teaching staff of from 35 to 90 employees.

Data Collection

The first and second author, with the assistance of a coworker, conducted digital interviews with all participants over a six-week period in the autumn of 2020, about 7–8 months into the pandemic. Due to a partial lockdown and the ongoing pandemic, all interviews were conducted via Teams. The interviews involved both video and audio communication to provide a personal connection and to accommodate the mutual dialogue. To ensure confidentiality and research ethics, the informants were advised that only speech was recorded on a separate device and transcribed verbatim within a few days after the interview. Each interview followed a semi-structured format. The introductory question, “Can you please tell us how you experienced the process of leading your school during the pandemic?” was followed by probing questions encouraging them to elaborate on their first encounter with the pandemic. Other questions focused on how they perceived changing role expectations, e.g. whether they had had to face new external demands or an increased need to attend to staff, students, and caregivers. Finally, questions prompted them to discuss the lessons they had learned and to talk about more personal aspects of the situation. The interviews, lasting 40–60 minutes, were audiotaped and transcribed. To conceal the identity of the participants, no names or background data were transcribed and a code was ascribed to each participant.

Analysis

The transcribed data was analyzed according to systematic text condensation (STC), which is a method first described by Giorgi (Citation1985) and later modified by Malterud (Citation2001). STC is a pragmatic method for thematic cross-sectional analysis of qualitative data, which is inductive and iterative, but also detailed and time-consuming to implement (Malterud, Citation2001). The data analysis was carried out by the first and second authors in four steps, as summarized in , inspired by Hauken and Larsen (Citation2019). In the first step, the interviews were read independently by the first and the second authors to obtain a general impression of the data. Following on from this first assessment, six preliminary topics were identified. In the second step, the material was reviewed line by line to identify and classify meaningful units that could be linked to the topics from the first analytical step. In this sequence, NVivo 12 software was used to code and sort the data. In this process, the themes from the first step became code groups that aided the sorting of meaningful units. In the third step, the meaningful units were sorted into groups and subgroups by abstracting the content of the individual meaning-bearing units. This coding process was conducted separately by the first and second authors before they compared and discussed the analytical framework until reaching consensus on the structure of the data. This processing and refinement resulted in three code groups, with two to three sub-themes within each code. In this process, each sub-theme was characterized by a condensate. According to Malterud (Citation2001), the condensate is an artificial quote summarizing and representing the phenomenon that the sub-theme describes. In the fourth and final step, an analytical text was created to elaborate on and detail some of the nuances associated with each condensate. The analytical text was validated by comparing the codes and sub-themes from the analytical process to the interview transcripts. The analytical text produced distinct or typical “gold quotes” that represent results from the study; these will be elaborated on in the results section.

Table 1. Overview of the analytical process in the study.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Norwegian Center for Research Data (NSD), which oversees data management and data protection in Norway (Ref code: NSD- 995280). The participants gave their written consent and were informed that participation in the project was voluntary and they could withdraw at any time. The informants were provided with contact information for a licensed psychologist if they felt the need to discuss more personal or sensitive matters in confidence outside of the interview situation. The researchers followed established guidelines in preserving the anonymity and safe storage and handling of the data.

Results

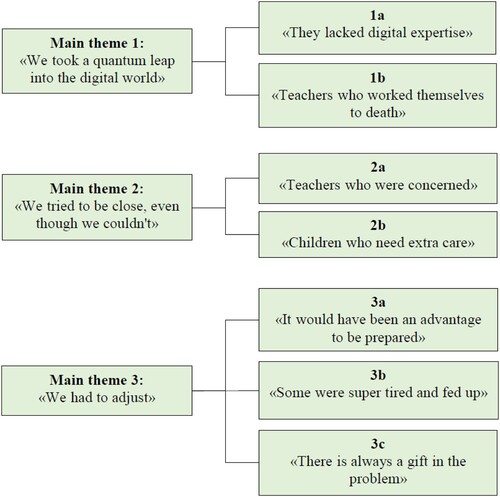

The analysis identified three main themes that captured the school principals’ leadership experiences while they were still actively engaged in dealing with the consequences of the pandemic: “We took a quantum leap into the digital world”, “We tried to be close, even if we could not be”, and “We had to adjust”. Each of these themes was elaborated on further in two or three sub-themes; see for an overview.

“We Took a Quantum Leap into the Digital World”

The first main theme addresses the need to achieve a rapid transition to a digital operational mode and how the school principals supported and experienced this process. This main theme was explored using two sub-themes: “They lacked digital competence” and “Teachers who worked themselves to death”.

Digital Competence

The first sub-theme elaborates on how new and largely unknown it was for the school staff to work and interact almost exclusively by digital media over prolonged time periods when the school was in full or partial lockdown. The digital competence of the staff was very heterogenous and several principals stated that their staff lacked sufficient digital competence. To address this shortcoming, most of the principals arranged for the employees to learn from each other by holding joint meetings and encouraging them to share their experiences with each other. Those with high digital skills came forward and soon started to share tips and advice. This sharing was very welcome and contributed to a steep learning curve for some employees. However, some employees responded by pulling back, becoming less accessible, and working less than they had before. In this way, the pandemic magnified differences between those who handled the digital everyday life and those who did not. Individual differences in competence, motivation, and skills became larger and more visible. Employees who did not deliver on digital teaching, were eventually offered other assignments. A principal described the abrupt transition in this way:

Suddenly we were sitting in each of our home offices. We had never run a school in this way before.

Regulating the Working Hours

The second sub-theme elaborates on how the principals became aware of employees who experienced challenges in regulating their working hours during the lockdown. Several employees informed the principals that their working days at the home office stretched throughout the afternoon and into the evening. Most of the schools managed to establish and maintain a structured daily routine with digital education from 0900 to 1200 pm every day. Then, teaching staff had a daily meeting at 2 pm. However, to keep in touch with parents and caregivers, the teachers needed to allocate more time to follow up. They were in effect teachers around the clock, and this became a very stressful situation. Several employees found balancing the teaching profession with family life challenging; they also identified that it was difficult to find good solutions that enabled them to organize digital education while caring for their own children. Several teachers therefore experienced the home office as a burden. One principal stated that they went from trying to get everyone to log on to trying to get everyone to sign off. Several of the school leaders tried to regulate the work pressure experienced by their staff by establishing a clearer framework and setting realistic expectations for teachers during the closure. Implementing a common core time for the whole school and following up teaching staff with a weekly telephone call were specific examples. However, some employees expressed opposition to aligning the standards and wanted to carry out their role in the way they themselves felt worked best. One principal stated:

My God, how they worked. So, I had to set some boundaries for teachers. I had to go in and say, “you are not allowed to work that much”, and to communicate it to the parents as well. It actually took off a bit, this focus on work, much more than we had thought.

“We tried to be Close, Even Though we Could not be”

The second main theme relates to how the school principals exercised their role as leaders and how they were challenged during the pandemic in terms of dealing with the needs of their employees, the students, and their parents. This main theme was explored under two sub-themes: “Teachers who were worried” and “Children who need extra care”.

Teachers Express Their Worries

The first sub-theme elaborates on how demanding several of the principals found following up and taking care of their employees. Most of the principals described having several members of their teaching staff in high risk groups and their insecurities, worries, or vulnerabilities being expressed in various ways. During the closure, several of the principals found reaching out to and addressing the concerns of these staff members challenging. Some experienced a greater threshold for being contacted digitally and observed that they had to be more sensitive to employee signals in the digital space. One principal expressed how some employees slipped into the background while others needed more attention. Another described concern about losing an overview of their staff. Several of the principals highlighted the reopening as particularly demanding. Reassuring staff that it was safe to come back to school when other businesses were still closed was challenging. Several alluded to logistical challenges concerned with taking care of staff members in high risk groups and described how they tried to reassure such staff by listening to them, keeping them informed of developments, and expressing their understanding of the stressful situation they experienced. One principal stated:

The biggest challenge, it was to reach out and meet everyone where they were, because it was so different.

Children in Need

The second sub-theme elaborates on principals’ concerns about not being able to identify and follow up students at risk and struggling to provide special education for students with learning difficulties. Some of the principles mentioned that the first–fourth-grade students in general needed more teacher supervision than the older students and allowing the younger children to return to school before the older cohort was a welcome development. A notable issue at some schools was that the first- and second-grade students had not yet got their own tablet, so it was a couple of weeks into lockdown before all students were online. Several of the principals said that, from early on, they had a good notion of students they thought would struggle during the lockdown, but they were still concerned about missing out on students who needed help. One principal emphasized that it was difficult to cope with these concerns when leading the school from home. Another felt that the concern was perhaps greatest among the local school authorities that were not in close contact with students. Some teachers expressed concerns about the family issues that emerged when caregivers struggled to make the student assignments and digital education work. The principals described how they had organized the digital education so that the parents would survive in an already tiring time and stated that some children and families in need were given extended support by the school. An example of such support was the provision, some weeks into the lockdown, of a special arrangement for children with special educational needs or children with parents in so-called “critical occupations” (i.e. healthcare, police, fire, and rescue) who needed someone to look after their younger children while they were at work. These groups of students were quite small and, in some cases, the principals also included a few extra children who had difficult domestic or family situations.

However, several principals found that some parents had declined the initial school initiatives to provide support and digital education. They described trying to support and encourage parental involvement in the schools’ digital education efforts by supplying abundant information and engaging in telephone calls with the caregivers. One principal described how this lack of collaboration with certain caregivers could instill a feeling of being an unsuccessful leader:

That’s probably what worries me the most. That is probably the price some children and young people will have to pay.

“We had to Adjust”

The third main theme relates to how the school principals had to constantly change the ways things were done in response to a constantly shifting situation. This main theme was explored under three sub-themes: “It would have been an advantage to be prepared”, “Some were super tired and fed up” and “There is always a gift in the problem”.

On Being Prepared

The first sub-theme elaborates on how most principals experienced being unprepared for the crisis and identifying that they had never imagined such a situation. Several of the principals described being expected to have answers to everything and having to make some decisions based on insufficient knowledge. Several expressed that it was difficult to know how the rules were to be interpreted, and that organizing everyday school life according to the infection control supervisors in practice was very difficult, if not impossible. In that context, several received good support and help from their superiors. However, some school leaders stated that they did not always get clear answers on how to solve things in practice and felt alone with their decisions. Several therefore turned to their principals’ network to gain clarification and take joint decisions for the district. One principal stated:

I notice that we have an enormous responsibility. The consequences can be so great. You think that the consequences could be that someone dies from it … based on the choice I took. That is usually not the case. So, it is obviously something you notice.

A Protracted Effort

The second sub-theme elaborates on how the high level of work pressure over time led to staff feeling extremely stressed. Several principals described their schools being given short deadlines to make changes and identified that rapid shifts during which the schools had to turn completely around were especially demanding. Several principals described trying to spare their employees by removing tasks and reducing their workload. One principal described the difficult balancing act involved in recognizing when it was time to demand more from their employees. Another described the difficulty of finding the spirit to engage in hard work in the autumn term and found that employees were still experiencing mental fatigue at the end of the year. One principal stated:

It’s about taking the pulse of where the staff is. There is no point in whipping them … when there are other things that are more demanding.

Learning from the Pandemic

The third sub-theme elaborates on how the crisis forced the principals to organize their schools in different ways and how doing so may have brought about desirable changes. Many of the principals felt that the new organization of free time, whereby the schoolyard is divided into areas alternating between cohorts, has resulted in fewer conflicts, clearer structures, and the students receiving closer adult follow up during break times. Several students identified having a better classroom environment because they do things together and others reported feeler safer. Several principals stated that some students, who usually struggle to complete a regular school day, finally managed to participate on an equal footing with the other students during digital education. Some students worked better at home than they did at school. They found the confidence to participate and they got to work in peace and quiet. One principal felt that the potential of what has been learnt during the pandemic is not being fully explored:

We have talked about that we must use this [experience] in some way in the future as well and learn from this very special situation.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to gain knowledge about how the Covid-19 pandemic affected the leadership role and behavior of primary school principals. The results from in-depth interviews with 15 principals are summarized here according to three main themes: (1) “We took a quantum leap into the digital world”, (2) “We tried to be close, even if we could not be”, and (3) “We had to adjust”. The findings related to these three main themes and the seven sub-themes are detailed and discussed based on the principals’ experiences and relevant literature. Finally, the study’s methodological strengths and limitations are considered and suggestions for future research offered.

We Took a Quantum Leap into the Digital World

The Covid-19 pandemic proved to have a significant impact on schools’ organization and work processes. The closure forced school principals and staff to work from home over a protracted period. New digital resources had to be implemented to maintain teaching, interact with colleagues, and support students and parents in the educational process. This abrupt and radical change in working conditions set new expectations and role requirements for the principals. In line with the theory of Job Demands and Resources (JD-R; Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2017), this change in role requirements and expectations can lead to a perceived imbalance in job requirements and resources for the school principals. A recent review pointed out that the pandemic, to different degrees, has affected job requirements and resources across industries and occupations (Kniffin et al., Citation2021). Our findings seem to indicate that the school principals experienced the pandemic as a significant stress test applied to the educational system in Norway. The pandemic revealed significant differences in digital competency among staff members. Working remotely and using digital workspaces was, to a large extent, a new and unfamiliar experience. The school principals found that some employees withdrew and became more passive because of their uncertainty and the many challenges associated with mastering the new digital work tools. Perceived role stress may have had a negative impact on work performance (Örtqvist & Wincent, Citation2006) and the passive avoidant coping strategy used by some staff could be seen as a response to cognitive overload and a high level of distress. Research has established that workers need to be properly prepared and trained in order to cope with significant organizational change (Li et al., Citation2020). However, the pandemic hit the educational system so quickly and with such force that the principals had to implement extensive changes with little or no time to prepare. The educational system is usually seen as difficult to change (Stevens, Citation2004). It is therefore a notable observation that the school principals seem to have successfully managed a radical restructuring of the educational system within just a few days during the initial phase of the pandemic.

The rapid transition from physical to digital teaching required an enormous joint transformation of the school organization and educational processes. Other studies of school restructuring during the Covid-19 pandemic have identified the availability of technical resources and inherent socio-economic inequalities as the most significant barriers to a comprehensive response to the effects of the pandemic in the school system (Delcker & Ifenthaler, Citation2021). Our study adds to this by identifying human factor challenges related to organizational, interpersonal, and individual factor barriers to the use and utilization of digital tools. To a large extent, the school principals seem to indicate that the schools and school districts had the necessary infrastructure in place to work remotely and offer distance learning, but that the main challenge was less about equipment and funding and more about organizational and interpersonal issues. A US study of school principals showed that, although some were insecure about the capacity of the school system, most felt confident that they themselves were sufficiently prepared to implement a transition to digital learning (Varela & Fedynich, Citation2020). An interesting finding from our study is that, prior to the pandemic and lockdown, some of the principals had begun to prepare and experiment with digital teaching tools. This may indicate that the educational system was ripe for but had not fully embraced the full potential of digital learning. Although some schools may have had a head start, the pandemic seemed to act as a catalyst in unlocking the potential to move a significant step forward in adopting a digital learning environment.

However, this abrupt transition to a digital workspace came with several disadvantages. Working from home as a teacher became challenging if you also had to care for your own children who were subject to digital education. Poor internet connection, substandard office space, software and hardware issues added to the stress of remote working during the pandemic. This is in line with other studies indicating that working conditions may have deteriorated for many workers during the pandemic (Kniffin et al., Citation2021). Our study complements this picture by highlighting that working from home also presented challenges regarding maintaining a much needed work–family balance during the shutdown. The school principals observed that staff tended to stretch working hours into the afternoon and evening. Thus, the consequence of a protracted work–family imbalance may be employees who struggle with fatigue and exhaustion and over time experience reduced behavioral, cognitive, and emotional functioning (Banks et al., Citation2019). The school principals expressed concern, and with good reason, since several studies have indicated that work–family conflict is negatively associated with well-being and performance (Amstad et al., Citation2011). Highly committed and valued workers may be subject to role overload in situations where they have a direct responsibility for clients or customers (Duxbury et al., Citation2008). The school principals found that several of their staff stayed online and were available to the students far beyond the usual working hours during the first half of the pandemic. In line with other international studies, the school principals in our sample had to address this issue by establishing clearer expectations, shifting from a permissive to a more direct leadership style to protect their staff from work-related burnout (McLeod & Dulsky, Citation2021).

We Tried to be Close, Even if We Could not be

When the Covid-19 pandemic manifested itself, the school principals soon realized the importance of meeting the needs of their staff. It became a priority for them to be able to keep in contact with their staff and to get a sense of their professional and personal situation during the early days of the pandemic. Providing a sense of continuity, task-focused coping, and psychosocial support is an important element of psychosocial crisis management (Gabriel & Aguinis, Citation2022). Still, maintaining an overview and keeping up day-to-day working relations with their staff soon became challenging. This finding may provide a different take on other studies that indicate an increased demand for support and guidance from staff during the pandemic (Beauchamp et al., Citation2021). Although the need for guidance may be higher, it is evidently more demanding to follow up virtual teams (Bell & Kozlowski, Citation2002). The school principals reported that they needed to be more sensitive to their employees’ communications in the digital room. This is consistent with empirical evidence indicating that communication through technology provides fewer social cues, which may complicate communication and interaction on sensitive interpersonal issues (Hinds & Weisband, Citation2003). The dispersed geographical location and lack of physical proximity could therefore restrict supportive interpersonal leadership behaviors (Bell & Kozlowski, Citation2002). One interesting finding was that principals, to a large extent, expressed a preference for an interpersonal and collegiate leadership style, which became much more difficult to practice during the pandemic. The need to practice more flexible leadership styles may be an important lesson learned from the pandemic.

Most of the principals in our study emphasized the need to provide correct and clear information about the pandemic situation, rules, and regulations. This indicates a sound understanding of the importance of maintaining clear, transparent, and reliable communication in effective crisis management (Wooten & James, Citation2008). An interesting finding was that some of the school leaders chose to adjust and adapt the information supplied by the government or local authorities. Such an adjustment and adaptation strategy may be instrumental in avoiding information overload and maintaining a focus on the high priority issues in the situation (Coombs, Citation2015). In this way, it is conceivable that the principals’ leadership behavior may have contributed to reducing some of the uncertainty and unpredictability encountered during the pandemic. This is also in line with other studies that have highlighted information management as an important aspect of caring for employees (Dirani et al., Citation2020).

A common concern for the school principals in this study was the mental health of students and the special needs of children at risk of abuse or neglect at home. In line with Varela and Fedynich (Citation2020), the principals in our study were concerned about whether the school had managed to identify and take care of vulnerable students during the pandemic. In addition to the psychosocial aspects of the pandemic, the Norwegian principals voiced concern for possible adverse long-term effects of the pandemic. In line with international studies, the principals were concerned about a performance gap due to socio-economic inequalities and educational differences resulting from extensive use of digital education (Anger & Plünnecke, Citation2020; Bol, Citation2020).

A growing cause of concern was how the schools could follow up children who did not log on to the digital gatherings in the morning and remained inaccessible over several days without submitting scheduled schoolwork. The principals expressed concern for these children and the difficulties encountered by special needs teachers and social workers in reaching out to these children and families and taking part in physical meetings during the pandemic. These concerns are highly relevant since children who are absent or dropping out of school are more likely to develop long-term problems (Burke & Dempsey, Citation2020; Hancock & Zubrick, Citation2015). An interesting finding from our study may be that the principals underestimated how the parents’ fear of infection may have made it more difficult to convince them to send their children to school even if there were extra services and support available. The school principals realized that they needed to trust their social workers, department heads or contact teachers, who followed up children and families closely, but our study leaves open the issue of trust between parents and the school principals. Thus, one outcome of the pandemic seems to have been a greater emphasis on the interpersonal relations and trust between principals and teachers (Ahlström et al., Citation2020). In this way, the pandemic emphasized the need to build collective trust to achieve organizational stability and accomplish crucial goals during times of crisis (Ahlström et al., Citation2020). Still, the caregivers and parents are very significant agents in digital education and they became much more involved in the children’s schooling. Thus, the implicit and less elaborated on aspect of the narratives from the school principals was that the pandemic empowered the parents as stakeholders and agents in the educational process.

We had to Adjust

The principals emphasized that one of the most immediate effects of the pandemic was that most of the routines, educational plans, and activities had to be cancelled, put on hold, or adapted. The pandemic forced the school principals to change and quickly adapt to a fluid situation in which they had little control (Beauchamp et al., Citation2021).

Several of the principals found organizing everyday life at their school according to the changes in infection control guidelines challenging. The school principals had limited experience with crisis management and protracted crisis situations of this magnitude. Some searched for direction and advice from their superiors in the local municipalities, but there were few clear answers to be found. Finally, the principals turned to their informal, personal network of fellow school principals to assess the situation and make joint decisions for the district. They started to share information and to collaborate informally to establish shared situational awareness and an effective crisis management response (Boin et al., Citation2013). This shift from an individual to a collective crisis response is in line with best practice recommendations for crisis management (Witt & Morgan, Citation2002).

A notable finding from the present study was the constant demand to assess the situation and make decisions on a multitude of issues that emerged because of the disruptive effects of the pandemic. Crisis situations are associated with increased ambiguity, time pressure, and lack of information (Boin et al., Citation2013). It is therefore hardly surprising that several of the principals mentioned the huge sense of responsibility they felt in deciding on how the school should cope with the crisis; they were aware that the outcomes of their decisions could have enormous consequences. Thus, the leadership role of the principals seemed to have become more complex, with higher stakes and less room for error. In combination with limited psychosocial support from the school districts, such complex role requirements may increase the danger of stress-related conditions and burnout (DeMatthews et al., Citation2021). The school principals admitted that the overtime and increased work demands associated with the transformation to remote schooling and a fully digitized educational situation were significant stress factors for both themselves and their staff. The swift pace of change (Kavanagh & Ashkanasy, Citation2006) combined with the loss of well-functioning routines (Stensaker et al., Citation2002) emerged as two notable stress factors in the adaptation process. Close monitoring of how the staff coped with the transition therefore emerged as a priority assignment for the school principals.

Despite the hardships, the pandemic also seemed to have produced new and promising experiences. The profound changes in school structure, routines, and activities gave the principals an opportunity to question the status quo and reflect on the future of the school organization and educational practices. Thus, the pandemic may also have brought an opportunity to challenge existing routines and establish new organizational processes (James & Wooten, Citation2005). In line with McLeod and Dulsky (Citation2021), our study indicates that the lessons learned from the pandemic may point to several possible future changes. One example of this may be the creation of new structures for family involvement in the educational process. Another example is continuously working to integrate technology in the educational sector, as well as understanding and recognizing students’ capacity to adopt self-regulated learning tools. A further example is the new way of organizing out of class time. During the pandemic, the schoolyard was divided into zones that alternated between the cohorts, resulting in less conflict and improved oversight so that students received closer adult supervision in these periods.

An intriguing observation was that some students who had been considered slow learners and had presented learning difficulties at school seemed to work better at home and managed to participate in the same way as other students during the digital education period. Thus, our study can provide indications that the transition to digital education may have given some students greater freedom to work in ways that served them well. These findings contrast with other studies that have indicated that students have struggled to follow up school assignments during digital education (Besser et al., Citation2020; Dhawan, Citation2020). Clearly, this is an area for future research and individual, socio-economic, and cultural factors may need to be considered in establishing an optimal home–school balance.

Another notable finding is that the crisis increased the involvement and cooperation of parents with schools but it also created tension between them. The pandemic and transition to digital education and increased interaction with the parents may offer hope for increased collaboration in the future. Even though the school principals identified several areas for future development, tensions may emerge between crisis management and reorganization now the schools are returning to a new normal (Boin et al., Citation2013). According to McLeod and Dulsky (Citation2021), crisis management will usually focus on minimizing damage and restoring order in the organization. This could eventually have a negative effect in quelling initiative and attempts to inspire innovation and move the organization in a new direction. It is therefore still an open issue whether the pandemic will result in lasting structural changes to the educational system. This will clearly be an issue to explore in future studies.

Implications

The present study contributes to our understanding of educational leadership. Until recently there was limited research on crisis management in the educational sector. Since the Covid-19 pandemic ravaged large parts of the world, there has been a growing interest in lessons learned from managing this unique and protracted crisis. We concur with Harris and Jones’ (Citation2020, p. 246) observation that “a new chapter is being written about school leadership in disruptive times that will possibly overtake and overshadow all that was written on the subject before”. The present study contributes to this end in several ways.

The school principals’ experiences during a protracted crisis underscore that effective crisis management needs to include several managerial tasks such as transparent communication, distributed leadership, learning from an unfolding situation, and decision making under uncertainty. In a long-term situation like the pandemic, the issue of trust emerged as an important factor. Leaders who provided psychosocial support and attended to the needs of staff and children with special needs fulfilled a crucial need during the pandemic. Following from this is the inherent understanding that effective crisis management requires a flexible approach. As the pandemic unfolded, school leaders had to adapt their leadership behavior in response to new external requirements and the internal needs of their staff and students.

Following from this, the role of the school principal became complex and demanding. The loneliness of command in crisis became pronounced, which raises the issue of crisis preparedness and how school organization and command structures in the educational sector can learn and grow as a result of the pandemic. It is therefore interesting to note that, while the pandemic was still ongoing, several of the school principals already seemed to be reflecting on future consequences. Thus, effective crisis management is not limited only to immediate and pressing concerns but also looks to the future as a sign of resilience and hope (Luthans & Broad, Citationin press).

Limitations

As the literature search revealed very few studies on protracted crisis management in the educational sector, an in-depth interview study emerged as the method of choice to explore this issue as it played out during the pandemic. A qualitative method is especially suitable when the research attempts to understand experiences, thoughts, expectations, motives, and attitudes from the individual’s point of view (Malterud, Citation2001). The research tradition seeks to gain access to rich descriptions of a phenomenon so that the essence of these experiences can be identified (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018), keeping in mind that the same phenomenon can be interpreted differently by different people or on different occasions or in different contexts (Langdridge, Citation2007). Although this approach did provide an opportunity to get close to each subject and produced rich transcripts for further analysis, some notable limitations should be observed.

First, the results cannot be generalized to educational leadership in general or across cultures. Our findings will at best provide some indications of relevant topics that could be further corroborated by larger samples and studies from other cultures. Second, the interviews were conducted digitally, mainly as video interviews, because of the increased risk of infection in Norway at the time of data collection. Although necessary at the time, this approach may have limited the creation of knowledge and the interaction between participant and interviewer (Kvale & Brinkmann, Citation2009). Data collection during an ongoing crisis is also challenging due to time pressure, priorities, or concern about personal exposure (Sommer, Howell & Hadley, Citation2016). However, the use of video interviews may have made it easier for school leaders to find time to participate in the study.

A third challenge follows from the fact that the phenomenological research tradition rests heavily on what information the respondents will share and how they have processed and reflected upon their experiences. In-depth interviews may therefore have limitations when it comes to uncovering how the school principals have exercised their leadership from the viewpoint of their staff. A study design combining independent data sources such as focus group interviews, observations or surveys should therefore be considered in follow-up studies.

The principals’ finding that some parents lacked the capacity or motivation to engage in digital schooling indicates that principals’ narratives need to be supplemented by and compared with the perspectives of caregivers and parents. The digital transformation of education rests on an assumption that caregivers are available, motivated, and capable of stepping up as volunteer co-teachers on top of their parenting and work roles. Although they emphasized that they and their teaching staff reached out and helped, it may well be that the school principals’ perspectives on the parent–school relationship are too rose-tinted. The parents’ stories would have been nuanced and thus provided a more sober account. A large nationwide survey of Norwegian parents indicates that unequal access to qualified help at home during the school lockdown may have challenged some of the core ideals of the Nordic model of education – where equal opportunity to learn is a key ambition (Blikstad-Balas et al., Citation2022).

The current study offers a unique opportunity to capture a range of issues and problems the school principals had to address during the onset and first months of the pandemic. In this respect, the present study is unique in providing scientific knowledge about a highly unusual event and describing how relatively unprepared school principals assessed and managed it.

Acknowledgments

We received no financial support for this research. We are grateful for the contribution of Sofie Steinsund in the data collection for and initial preparation of this project.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Ahlström, B., Leo, U., Norqvist, L., & Isling, P. (2020). School leadership as (un)usual. Insights from principals in Sweden during a pandemic. In D. Gurr (Ed.), International studies in educational administration (2nd ed., pp. 35–41). CCEAM.

- Amstad, F. T., Meier, L. L., Fasel, U., Elfering, A., & Semmer, N. K. (2011). A meta-analysis of work-family conflict and various outcomes with a special emphasis on cross-domain versus matching-domain relations. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16(2), 151–169. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022170

- Anger, C., & Plünnecke, A. (2020). Schulische bildung zu zeiten der corona-krise. Perspektiven der Wirtschaftspolitik, 21(4), 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1515/pwp-2020-0055

- Bailey, K., & Breslin, D. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic: What can we learn from past research in organizations and management. International Journal of Management Reviews, 23(1), 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12237

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands-resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000056

- Banks, S., Landon, L. B., Dorrian, J., Waggoner, L. B., Centofanti, S. A., Roma, P. G., & Van Dongen, H. P. (2019). Effects of fatigue on teams and their role in 24/7 operations. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 48, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2019.101216

- Beauchamp, G., Hulme, M., Clarke, L., Hamilton, L., & Harvey, J. A. (2021). ‘People miss people’: A study of school leadership and management in the four nations of the United Kingdom in the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 49(3), 375–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143220987841

- Bell, B. S., & Kozlowski, S. W. (2002). A typology of virtual teams: Implications for effective leadership. Group & Organization Management, 27(1), 14–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601102027001003

- Besser, A., Flett, G. L., & Zeigler-Hill, V. (2020). Adaptability to a sudden transition to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: Understanding the challenges for students. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/stl0000198

- Blikstad-Balas, M., Roe, A., Dalland, C. P., & Klette, K. (2022). Homeschooling in Norway during the pandemic-digital learning with unequal access to qualified help at home and unequal learning opportunities provided by the school. In F. M. Reimers (Ed.), Primary and secondary education during Covid-19 (pp. 177–201). Springer.

- Boin, A., Kuipers, S., & Overdijk, W. (2013). Leadership in times of crisis: A framework for assessment. International Review of Public Administration, 18(1), 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/12294659.2013.10805241

- Bol, T. (2020). Inequality in homeschooling during the Corona crisis in the Netherlands. First results from the LISS Panel. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/hf32q

- Burke, J., & Dempsey, M. (2020). Covid-19 practice in primary schools in Ireland report. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.14091.03369

- Coombs, W. T. (2015). The value of communication during a crisis: Insights from strategic communication research. Business Horizons, 58(2), 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2014.10.003

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 5th ed. Sage Publications.

- Delcker, J., & Ifenthaler, D. (2021). Teachers’ perspective on school development at German vocational schools during the Covid-19 pandemic. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 30(1), 125–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2020.1857826

- DeMatthews, D., Carrola, P., Reyes, P., & Knight, D. (2021). School leadership burnout and job-related stress: Recommendations for district administrators and principals. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 94(4), 159–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.2021.1894083

- Dhawan, S. (2020). Online learning: A panacea in the time of Covid-19 crisis. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 49(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239520934018

- Dirani, K., Abadi, M., Alizadeh, A., Barhate, B., Garza, R., Gunasekara, N., Ibrahim, G., & Majzun, Z. (2020). Leadership competencies and the essential role of human resource development in times of crisis: A response to Covid-19 pandemic. Human Resource Development International, 23(4), 380–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2020.1780078

- Duxbury, L., Lyons, S., & Higgins, C. (2008). Too much to do, and not enough time: An examination of role overload. In K. Karabik, D. S. Lero, & D. L. Whitehead (Eds.), Handbook of work-family integration: Research, theory, and best practices (pp. 125–140). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000062

- Education act. (1998). Act No. 61 of 17 July 1998 relating to primary and secondary education and training. https://lovdata.no/lov/1998-07-17-61

- Fernandez, A. A., & Shaw, G. P. (2020). Academic leadership in a time of crisis: The coronavirus and COVID-19. Journal of Leadership Studies, 14(1), 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/jls.21684

- Gabriel, K. P., & Aguinis, H. (2022). How to prevent and combat employee burnout and create healthier workplaces during crises and beyond. Business Horizons, 65(2), 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2021.02.037

- Giorgi, A. (1985). Sketch of a psychological phenomenological method. In A. Giorgi (Ed.), Phenomenology and psychological research (pp. 8–22). Duquesne University Press.

- Government. (2021, February 1). Tidslinje: myndighetenes håndtering av koronasituasjonen. https://www.regjeringen.no/tema/Koronasituasjonen/tidslinje-koronaviruset/id2692402/

- Hancock, K., & Zubrick, S. (2015). Children and young people at risk of disengagement from school: Literature review. Commissioner for Children and Young People, Western Australia. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281257513

- Harris, A., & Jones, M. (2020). COVID 19 – school leadership in disruptive times. School Leadership & Management, 40(4), 243–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2020.1811479

- Hauken, M. A., & Larsen, T. (2019). Young adult cancer patients’ experiences of private social network support during cancer treatment. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(15–16), 2953–2965. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14899

- Hinds, P. J., & Weisband, S. P. (2003). Knowledge sharing and shared understanding in virtual teams. In C. B. Gibson, & S. G. Cohen (Eds.), Virtual teams that work: Creating conditions for virtual team effectiveness (pp. 21–36). John Wiley & Sons.

- James, E. H., & Wooten, L. P. (2005). Leadership as (un)usual: How to display competence in times of crisis. Organizational Dynamics, 34(2), 141–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2005.03.005

- James, E., Wooten, L., & Dushek, K. (2011). Crisis management: Informing a new leadership research agenda. Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 455–493. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2011.589594

- Kavanagh, M. H., & Ashkanasy, N. M. (2006). The impact of leadership and change management strategy on organizational culture and individual acceptance of change during a merger. British Journal of Management, 17(S1), S81–S103. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2006.00480.x

- Kniffin, K. M., Narayanan, J., Anseel, F., Antonakis, J., Ashford, S. P., Bakker, A. B., Bamberger, P., Bapuji, H., Bhave, D. P., Choi, V. K., Creary, S. J., Demerouti, E., Flynn, F. J., Gelfand, M. J., Greer, L. L., Johns, G., Kesebir, S., Klein, P. G., Lee, S. Y., … Vugt, M. V. (2021). Covid-19 and the workplace: Implications, issues, and insights for future research and action. American Psychologist, 76(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000716

- Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2009). Det kvalitative forskningsintervju. 2nd ed. Gyldendal Akademisk.

- Langdridge, D. (2007). Phenomenological psychology: Theory, research and method. Pearson Education.

- Li, J.-Y., Sun, R., Tao, W., & Lee, Y. (2020). Employee coping with organizational change in the face of a pandemic: The role of transparent internal communication. Public Relations Review, 47(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2020.101984

- Luthans, F., & Broad, J. D. (in press). Positive psychological capital to help combat the mental health fallout from the pandemic and VUCA environment. Organizational Dynamics, 100817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2020.100817

- Malterud, K. (2001). Qualitative research: Standards, challenges, and guidelines. The Lancet, 358(9280), 483–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6

- McLeod, S., & Dulsky, S. (2021). Resilience, reorientation, and reinvention: School leadership during the early months of the Covid-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Education, 6, 70. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.637075

- Netolicky, D. M. (2020). School leadership during a pandemic: Navigating tensions. Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 5(3/4), 391–395. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPCC-05-2020-0017

- O’Connell, A., & Clarke, S. (2020). A school in the grip of Covid-19: Musings from the principal’s office. International Studies in Educational Administration, 48(2), 4–11.

- Örtqvist, D., & Wincent, J. (2006). Prominent consequences of role stress: A meta-analytic review. International Journal of Stress Management, 13(4), 399–422. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.13.4.399

- Pepper, M. J., London, T. D., Dishman, M. L., & Lewis, J. L. (2010). Leading schools during crisis: What school administrators must know. Rowman & Littlefield Education.

- Smawfield, D. (2013). Education and natural disasters: Education as a humanitarian response. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Sommer, S. A., Howell, J. M., & Hadley, C. N. (2016). Keeping positive and building strength: The role of affect and team leadership in developing resilience during an organizational crisis. Group & Organization Management, 41(2), 172–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601115578027

- Statistics Norway. (2020, December 17). Elever i grunnskolen. https://ssb.no/utgrs

- Stensaker, I., Meyer, C. B., Falkenberg, J., & Haueng, A. C. (2002). Excessive change: Coping mechanisms and consequences. Organizational Dynamics, 31(3), 296–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0090-2616(02)00115-8

- Stevens, R. J. (2004). Why do educational innovations come and go? What do we know? What can we do? Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(4), 389–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2004.02.011

- Taglietti, D., Landri, P., & Grimaldi, E. (2021). The big acceleration in digital education in Italy: The COVID-19 pandemic and the blended-school form. European Educational Research Journal, 20(4), 423–441. https://doi.org/10.1177/14749041211021246

- Varela, D. G., & Fedynich, L. (2020). Leading schools from a social distance: Survey south Texas school district leadership during the Covid-19 pandemic. National Forum of Educational Administration and Supervision Journal, 38(4), 1–10.

- Witt, J. L., & Morgan, G. (2002). Stronger in broken places: Nine lessons for turning crisis into triumph. Times Books.

- Wooten, L. P., & James, E. H. (2008). Linking crisis management and leadership competencies: The role of human resource development. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 10(3), 352–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422308316450