Abstract

Background: Previous studies have demonstrated that student ratings of a teachers’ performance do not incentivize clinical teachers to reflect critically and generate plans to improve their teaching. Peer group reflection might offer a solution in mediating this change.

Aim: To investigate: (a) to which extent clinical teachers perceive self-evaluation, student ratings and peer group reflection effective; and (b) whether additional peer group reflection fosters critical reflection and the translation of feedback into concrete plans of action.

Method: We conducted a quasi-experiment, inviting two groups of 10 clinical teachers each (1) to complete a self-evaluation and (2) subsequently examine their student ratings. One group participated in (3) an additional peer group reflection meeting. All participants were finally requested to define plans for improvement and evaluate each activity’s effectiveness.

Results: Participants perceived all three activities to be effective. Levels of reflection did not differ across the two groups. However, participation in peer group reflection did result in generating more concrete plans to change clinical teaching.

Conclusions: Peer group reflection on student ratings shows promise as tool to assist clinical teachers in generating plans for improvement. Future research should focus on whether teaching indeed improves with the introduction of peer group reflection.

Introduction

Feedback has been conceptualized as “information provided by an agent (e.g. teacher, peer, book, parent, self, and experience) regarding aspects of one’s performance or understanding” (Hattie and Timperley Citation2007, p. 81). Without it, most physicians, cannot determine their own strengths and weaknesses (Holmboe et al. Citation2011), making feedback essential to learning and practice improvement (Sargeant et al. Citation2009; Sluijsmans et al. Citation2013). Ramani (Citation2006) advocates that providing feedback on supervisory skills of clinical teachers is key in faculty development. However, feedback by itself may not have the power to initiate further action or change teaching (Beijaard and Vries Citation1997; Steinert et al. Citation2006). Therefore, we might question the mere providing of student ratings to clinical teachers with regard to stimulating them to critically reflect on their performance as well as encouraging them to generate concrete plans for improvement of their clinical teaching.

Earlier Hattie and Timperley (Citation2007) proposed a model of feedback to enhance learning. In this model, effective feedback should provide an answer to three questions: (1) where am I going (feed up); (2) how am I going (feedback); and (3) where to next (feed forward). They conclude that being able to answer the feed-forward question can have some of the most powerful effects on learning. In the current literature, however, it is still under debate how to best facilitate answering this feed-forward question. Several authors have explored the use of self-assessment, reflection on and dialog about feedback in this regard (Boerboom et al. Citation2015; Ramani Citation2015). In the following paragraph, we will explore these concepts and their role in the feedback process in more detail.

Reflection has been defined as a meta-cognitive process that creates greater understanding of self and situations to inform future actions (Sandars Citation2009). It is a deliberate process whereby the learner develops an understanding of a situation so that future actions can be informed. Self-assessment has been referred to by Eva and Regehr (Citation2008) as “a personal, unguided reflection on performance for the purposes of generating an individually derived summary of one’s own level of knowledge, skill and understanding in a particular area” (p. 15). Eva and Regehr (Citation2008) concluded that self-assessment does not provide the information sufficient to guide performance improvement effectively. Sargeant et al. (Citation2008) proposed that it is important to integrate self-assessment with external feedback to enable its use for practice improvement. Stalmeijer et al. (Citation2010) demonstrated that self-assessment combined with student feedback might at least provide faculty with an incentive to commit to change and seek support when they observed discrepancies between their own ratings and those of their students. Next, Boerboom et al. (Citation2015) demonstrated in their review of the literature on the feedback process that dialog with peers could help clinical teachers to interpret student feedback, engage in critical reflection and translate feedback into concrete plans of action. Steinert et al. (Citation2006) described in their study of the literature on faculty development initiatives designed to improve teaching effectiveness in medical education, the value of peers as role models and the mutual exchange of information and ideas. Several authors indicated as well that peers can be viewed as instructional resources for one another, sharing learning intentions and criteria for success (Black and Wiliam Citation2009; Sluijsmans et al. Citation2013). Tigelaar et al. (Citation2008) demonstrated for instance that peer group reflection, which can be seen as a special structured and guided form of dialog with peers, was a promising tool to promote learning by teachers and to enhance the quality of reflections by teachers. Boerboom et al. (Citation2011) found as well that a strategy consisting of self-assessment, student feedback, including peer group reflection helped veterinary clinical teachers to critically reflect on their clinical teaching. Most participants in this study experienced that peer group reflection helped them to translate student feedback into concrete alternatives for their teaching practice by elaborating on their student feedback with their peers. However, some participants in this study experienced that joining in a peer group reflection meeting was time consuming and did not help them to reflect because their peers were just facing the same problems.

To conclude, reflection is key in the feedback process, in answering the feed-forward question and fundamental in closing the feedback loop (Hattie and Timperley Citation2007; Ramani Citation2015). There is an indication that peer group reflection appears to be a promising facilitator in the feedback process by enhancing reflection quality. Participation in peer group reflection could as such provide an opportunity for clinical teachers to answer the feed-forward question, i.e. to stimulate the generation of concrete plans for improvement (Boerboom et al. Citation2015) and increase the quality of clinical teaching at the workplace. It is important to provide more evidence for the value of peer group reflection in the feedback process for clinical teachers in different contexts since these meetings are usually costly and time consuming with the result that acceptance and funding for this type of faculty development can be challenging.

Hence, the purpose of this study is to investigate whether peer group reflection facilitates the feedback process for clinical teachers in undergraduate medical education after having received their student ratings. We were particularly interested in knowing whether participation in peer group reflection promoted critical reflection and the generation of alternative plans to improve clinical teaching. Based on these criteria, we formulated the following research questions:

To which extent do clinical teachers perceive self-evaluation, student ratings and peer group reflection effective as tools to reflect on student feedback?

To what extent does additional peer group reflection foster critical reflection and the translation of feedback into concrete plans of action?

Methods

Design

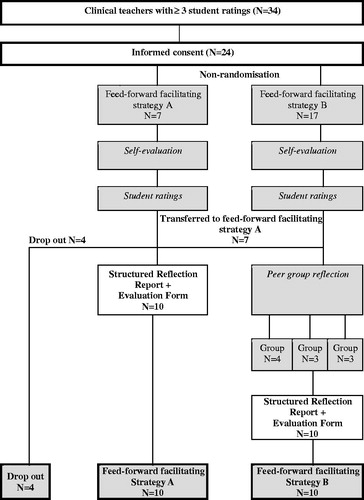

Based on findings from the literature (Stalmeijer et al. Citation2010; Boerboom et al. Citation2011; Boerboom et al. Citation2015) we developed a feed-forward facilitating strategy for clinical teachers. The strategy that resulted had three components: (1) self-evaluation; (2) providing teachers with feedback about their teaching performance based on student ratings; and (3) participation in peer group reflection. We designed a quasi-experiment in which we assigned two groups to feed-forward facilitating strategies A or B, both consisting of (1) online self-evaluation questionnaire followed by (2) a report of their student ratings. Strategy B, however, also included (3) participation in a peer group reflection meeting where participants discussed their self-evaluation and student ratings with peers. At the end of each strategy, all participants filled in a structured reflection report and an evaluation form (). Clinical teachers who consented to participate in this study could indicate their preference for one of the strategies.

Context

We conducted this study at Maastricht University (UM), the Netherlands, during the integrated clinical rotation in General Practice and Social Medicine between October and November 2015. This rotation has been offered in its current form as one of the five core rotations in the Master’s in Medicine since January 2015. The curriculum of this master’s program is organized into integrated, longitudinal clinical rotations with continuity of care and supervision as their organizing principles (Hirsh et al. Citation2007). During their eight-week stay in the general practice workplace, medical students have the opportunity to work side by side with a single general practitioner (GP) in an authentic learning environment and participate in a healthcare team. This supervising GP regularly observes the medical student during patient encounters or patient examinations. One of the supervisor’s tasks is to help students hone their competencies by providing them with meaningful narrative feedback.

Participants

We invited 34 GPs (hereinafter referred to as clinical teachers) involved in clinical teaching in the general practice workplace to participate in this study. The criterion for including them was that at least three students who had done their rotation in the clinical teacher’s workplace had evaluated them in the period between January and November 2015. The clinical teachers had had no previous reflective experiences on their own student ratings since these evaluation data were never made available to them before.

Instruments

Online self-evaluation questionnaire

For general quality improvement purposes, students used to fill in a paper based evaluation questionnaire at the end of each rotation to rate the teachers’ clinical teaching performance. This questionnaire was based on the continuity principles of longitudinal integrated clerkships and experience-based learning in a community of practice (Dornan et al. Citation2007; Hirsh et al. Citation2007; Dornan et al. Citation2014). It consisted of 19 Likert-type questions (1 = fully disagree; 5 = fully agree) about the rotation in the clinical teacher’s workplace, distributed over four themes: (1) introduction in the workplace and arrangements; (2) supervision; (3) patient consultations and other activities; and (4) the workplace in general. Four additional questions asked for an overall rating of the organization, supervision, instructiveness and learning climate in the workplace (score of 1–10: 1 = very poor; 6 = sufficient; 10 = excellent). At the end students were requested as well to give narrative feedback on strengths and weaknesses of the clinical teacher.

The online self-evaluation questionnaire for participants in this study was similar to the student rating form, the only difference being that the questions were written from a teachers’ perspective (Supplementary Appendix 1). It ended with two open-ended questions about own perceived strengths and weaknesses in clinical teaching. The same online self-evaluation questionnaire was also used to collect data on age, gender, type of practice (independent or shared with one or more GPs), prior experience as a clinical teacher and medical doctor in years and on past attendance of faculty development programs.

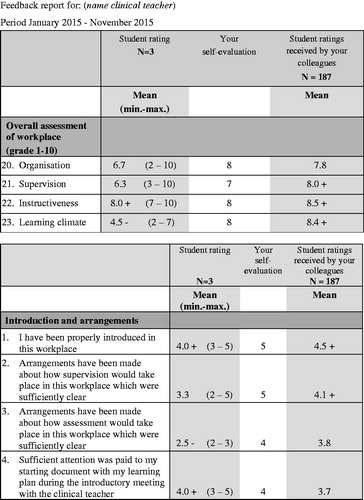

Student ratings

The clinical teachers in both groups received their student ratings by post as soon as they returned the online self-evaluation questionnaire. This report contained average student ratings of their performance, in addition to their self-evaluation ratings and the mean ratings of all clinical teachers in this rotation (). Narrative comments of both students and the clinical teacher him/herself drawn from the individual evaluations were also included.

Peer group reflection meeting

The participants assigned to strategy B attended a reflection meeting in groups of three to four peers which lasted about 1.5 h. A staff member (GP) of the department of General Practice at Maastricht University, the Netherlands, moderated the meeting. The principal investigator (MvL) trained moderators in facilitating a peer group reflection meeting using the Quick-Scan Method (Hendriksen Citation2009) (Supplementary Appendix 2), a method especially suited for small group sessions that have limited time available. Participants were asked to formulate one personal learning question, based on the student ratings they had received, and to bring this forward during the peer group reflection meeting. Moderators, in turn, used these personal learning questions to guide the group discussion. Participants elaborated with each other on the learning questions raised, presented alternative perspectives to their peers and offered them suggestions for clinical teaching. At the end of the meeting participants shared their key learning points.

Structured reflection report

At the end of the last activity of each group, we asked participants to reflect on the student ratings they had received. In other words, group-A participants wrote down their reflections immediately after perusal of the student ratings, while group-B participants did so upon conclusion of the peer group reflection meeting (). The questions posed to participants were adapted from the structured reflection report developed by Boerboom et al. (Citation2011) who used it to investigate how peer group reflection helped clinical teachers to critically reflect on feedback. Their questions were based on a model of structured reflection coined ALACT, which stands for action, looking back on the action, awareness of essential aspects, creating alternative methods of action, and trial (Korthagen and Vasalos Citation2005). Supplementary Appendix 3 presents the questions contained in our structured reflection report which we used to determine the level of reflection and the extent to which participants generated plans for improvement.

Evaluation form

In the final part of this quasi-experiment all participants filled in an evaluation form measuring the perceived effectiveness of the different activities they participated in. Items in the evaluation form were scored on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (fully disagree) to 5 (fully agree). The items about the overall effectiveness were rated on a 10-point scale, ranging from 1 (very poor) to 10 (excellent). Participants were also asked to describe their positive and negative experiences with each activity they participated in.

Analysis

We first analyzed the evaluation forms in order to establish the perceived effectiveness of the three activities by computing means and SDs for all items using SPSS 21. For each activity, that is, doing a self-evaluation, examining the student ratings, and participating in a peer group reflection meeting, we aggregated scores of perceived effectiveness. A score below 3.0 on a 5-point Likert scale was considered to be insufficient, a score of 4.0 or higher as good and a score in between as sufficient. The score for the overall effectiveness of each activity was considered sufficient when 7.0 on a 10-point scale.

Next, we analyzed the structured reflection reports to determine the level of reflection using the criteria set by Boerboom et al. (Citation2011) to investigate the effect of peer group reflection on critical reflection on feedback. These were drawn from a summary of the framework developed by Hatton and Smith (Citation1995) and later adapted by Pee et al. (Citation2002) and essentially represent four levels of reflection in ascending order: (1) descriptive writing: the clinical teacher is merely reporting events with no attempt to provide reasons; (2) descriptive reflection: the clinical teacher provides reasons, but only in a reporting way; (3) dialogic reflection: the clinical teacher demonstrates a form of discourse with him/herself and explores alternative methods of action; and (4) critical reflection: the clinical teacher takes account of the context in which the events take place and decisions are made. In terms of level of reflection, we considered the final two levels (dialogic and critical reflection) as the most successful outcomes of the feed-forward facilitating strategy clinical teachers participated in.

Lastly, we assessed the extent to which participants generated alternative methods of action, representing phase 4 of the ALACT model of structured reflection previously mentioned (Korthagen and Vasalos Citation2005), by again analyzing the structured reflection reports following Boerboom et al.’s (Citation2011) example. They distinguished between four levels of alternative methods of action in ascending order: (1) no alternative methods of action; (2) aspects in need of improvement: teacher provides no alternatives but does indicate areas that require improvement; (3) alternative methods: alternatives are provided, but no concrete plan; and (4) alternative methods and plan: both achievable alternatives and an action plan are provided. We qualified level 4 as the best attainable outcome of the feed-forward facilitating strategy.

The principal investigator (MvL) and a second researcher (LJ) independently performed the analysis for each individual reflection report as described above. The answers in the structured reflection reports could not be traced to the group clinical teachers participated in and were rendered anonymous. After the first round, we computed the percentage of interrater agreement on the level of reflection and level of alternative methods of action of each individual participant. Concerning the level of reflection, the interrater agreement amounted to 35%. The percentage of interrater agreement on the level of alternative methods of action was 80%. In a second round, both raters discussed the structured reflection reports that they did not agree upon to jointly determine the level of reflection and level of alternative methods of action. We used descriptive statistics to analyze the results.

Ethical issues

Participants received an email invitation in which we explained all research aims and procedures and asked for informed consent before sending the digital self-evaluation questionnaire. Participation was voluntary and participants had the possibility to opt out any time during the study. Since the principal investigator, as one of the rotation’s coordinators, had a professional relationship with participants, we emphasized in the email that the decision to participate in the study or not would not affect this relationship in any way whatsoever, nor students’ future allocation to any specific workplace. Before sending the student ratings to participants, we removed any information that could be traced to an individual student. Participants had no access to each other’s student feedback, nor did the moderators of the peer group reflection meeting have access to the student ratings of participants. The ethical review board of the Netherlands Association for Medical Education (NVMO) approved the study (ERB dossier number 552).

Results

Of the 34 GPs we invited, 24 (70%) agreed to participate. Initially, seven participants indicated their preference for strategy A, which consisted of an online self-evaluation combined with the receipt of their student ratings. The remaining 17 participants opted for strategy B, which, in addition to the two activities of strategy A, also included participation in peer group reflection. Mostly due to time constraints, seven clinical teachers eventually did not manage to participate in the additional peer group reflection meeting they had initially signed up for. These participants were transferred to strategy A. Next to this, a total of four participants in strategy A did not complete the structured reflection report and the evaluation form, despite our reminder to do so (). As a result, finally ten participants completed strategy A and another ten participants completed strategy B.

Almost all participants (95%) were male clinical teachers. The majority of participants were aged 50 years or above (55%), had worked as a GP for more than five years (85%) and had been active as a clinical teacher for over 5 years (70%). Participants in the additional peer group reflection meeting (part of strategy B) were older (70% ≥ 50 years) and all of them had participated in a general training for clinical teachers before. The mean score for the four questions which asked for an overall rating of the organization, supervision, instructiveness and learning climate in the workplace, as provided in the student ratings, was 8.3 (SD 1.43) for participants in strategy A. For participants in the additional peer group reflection meeting (part of strategy B) this score was 7.7 (SD 1.38).

Perceived effectiveness of self-evaluation, student ratings and peer group reflection

In we present aggregated scores (means and SDs) for the perceived effectiveness of self-evaluation, student ratings and peer group reflection. As regards the first activity, self-evaluation, participants rated its use for reflection on student feedback 3.9 on a 5-point Likert scale (SD 1.0). The scores for the items about its instructiveness, potential to encourage reflection on clinical teaching and the creation of alternative methods varied between 3.1 and 3.8 (SD 0.9 – 1.0), whereas the item about encouragement of changes in one’s clinical teaching was valued 2.9 (SD 0.9). The overall effectiveness of self-evaluation was rated 7.0 on a scale of 1–10 (SD 1.5).

Table 1. Perceived effectiveness of self-evaluation, student ratings and peer group reflection.

The usefulness of student ratings for reflection was rated 4.0 on a 5-point Likert scale (SD 1.0). Scores for the remaining five items dealing with specific aspects of effectiveness ranged from 3.4 to 3.9 (SD 0.7–1.1). The overall effectiveness of student ratings was rated 7.5 on a 10-point scale (SD 1.4). Finally, the value of peer group reflection for reflection on student feedback was rated 4.0 on a 5-point Likert scale (SD 0.8); ratings for the remaining five items varied between 3.8 and 4.2 (SD 0.6–0.9). The overall effectiveness of peer group reflection was rated 7.4 on a scale of 1 to 10 (SD 1.5).

Experiences with self-evaluation, student ratings and peer group reflection

Participants reported a total of 46 positive and 25 negative experiences with the different activities: there were 17 positive and 13 negative experiences (N = 20) with self-evaluation; 20 positive and 10 negative experiences (N = 20) with the student ratings; and 9 positive and 2 negative experiences (N = 10) with peer group reflection. lists some of these positive and negative experiences. Considering the positives, what participants appreciated about the self-evaluation was that it helped them to look at their own clinical teaching in a structured way and to realize what working in practice preferably should offer the student. The student ratings were valued because it afforded participants insight into aspects of their clinical teaching in a structured, instructive manner, which was confronting at times but at the same time it was perceived to encourage them to move their clinical teaching forward. Positive aspects of the peer group reflection meeting were the opportunity to learn from peers, have interaction and dialog with peers and the stimulus it provided to reflect on one’s own clinical teaching. During the peer group reflection meetings, learning questions like “How do other clinical teachers discuss illness-related issues with the student during consultation hours?” and “What is meaningful feedback and how do I provide this to the student?” were raised.

Table 2. Some examples of positive and negative experiences.

Most of the negative experiences participants reported concerned the self-evaluation and sprang from the time investment in relation to its perceived limited effectiveness. A negative point raised about the student ratings was that it was based on too few student evaluations (i.e. three students only). The peer group reflection meeting received only two negative remarks, specifically that the meeting started at an inconvenient time and that the moderator followed the rules too strictly which one participant did not appreciate.

Levels of reflection

Descriptive writing or descriptive reflection was observed in 40% of the reflection reports (). The results indicated further that the majority of participants exhibited dialogic or critical reflection (60%), which percentage was the same for both groups.

Table 3. Levels of reflection and alternative methods of action of participants, based on the answers given in the completed reflection reports.

The following quote from the reflection report shows an example of dialogic reflection (level 3) of a participant (group A): “…. It was also indicated by a student that he/she would be more encouraged by me if I put forward more questions. I initially had the idea that students are able to self-direct their learning, however I probably need to offer more coaching or support to them.”

Levels of alternative methods of action

We finally concurred that: 15% of all participants formulated no alternative methods (level 1), 20% were able to create alternative methods of action (level 3), while 65% worked out alternative methods and plans (level 4). The clinical teachers who had participated in the additional peer group reflection meeting (strategy B) all presented the highest level of alternative methods of action (100%; level 4). A mere of 30% of the clinical teachers who did not participate in peer group reflection (strategy A) exhibited level 4, whereas 40% of them obtained level 3.

The following quote from the reflection report shows an example of the highest level of alternative methods and plans of a participant: “Introductory question (ask the student at the start of the clerkship): how do you want to get feedback?; I will make a planning for the period of eight weeks and distribute the cases along the weeks”

Discussion

In this study, we sought to investigate how clinical teachers evaluate a self-evaluation, combined with student ratings and peer group reflection as tools to reflect on their performance as clinical teacher in undergraduate medical education. We also gauged clinical teachers’ levels of reflection and alternative methods of action based on the structured reflection reports they filled in after having participated in one of two feed-forward facilitating strategies: (A) a self-evaluation combined with student ratings; and (B) a peer group reflection meeting in addition to the two activities of strategy A.

Participants perceived all three activities as sufficiently effective steps in reflecting on their performance as clinical teacher. Especially the student ratings and the peer group reflection received positive scores, particularly in terms of their instructiveness and ability to encourage reflection on clinical teaching, while those for the self-evaluation were more moderate. The latter finding is in line with the study of Eva and Regehr (Citation2008). Of the three activities, peer group reflection was considered as having a high level of potential to encourage reflection and the generation of alternative methods of action given the positive scores on perceived effectiveness. Participation in peer group reflection was appreciated most for the opportunity it offered to engage in dialog with peers, which is in line with the study of Boerboom et al. (Citation2011) who demonstrated that participating in peer group reflection helped clinical teachers to take different perspectives. Major negative experiences with peer group reflection, e.g. the fact that it is time consuming for participants, were not reported in our study. The observed positive experience in our study with self-evaluation echoes earlier findings from the study by Stalmeijer et al. (Citation2010) in which they observed that combined student ratings and self-assessment helped clinical teachers to better understand the quality standards for the rotation.

With respect to the levels of reflection, we established that the majority of participants in this quasi-experiment demonstrated either dialogic (level 3) or critical reflection (level 4). Additional participation in peer group reflection did not result in a higher level of reflection, which finding contrasts with those reported earlier by Boerboom et al. (Citation2011) that adding peer group reflection to a self-evaluation and feedback report helps clinical teachers to critically reflect on their teaching. However, this study also demonstrates that the majority of all participants formulated alternative methods and plans to improve clinical teaching, which we qualified as the highest level of alternative methods of action (level 4). Clinical teachers who participated in the additional peer group reflection meeting were apparently best able to work out alternative methods and plans for clinical teaching. This finding is in line with the conclusion by Boerboom et al. (Citation2011) that adding peer group reflection to a self-evaluation and student ratings does result in more concrete plans for improvement of clinical teaching. Meeting with peers to reflect on student ratings afforded participants the opportunity to guide/direct each other, and propose and explore alternatives, as the study of Tigelaar et al. (Citation2008) revealed as well. Boerboom et al. (Citation2011) made a similar conclusion, being that participation in peer group reflection, by presenting different perspectives, helped clinical teachers to translate student ratings into plans to alter their teaching.

In conclusion, self-evaluation, student ratings and peer group reflection are effective tools for helping clinical teachers in undergraduate medical education to reflect on their performance as clinical teacher. A combination of the described activities used in this study promoted dialogic and critical reflection in clinical teachers on their performance as clinical teacher. Additional participation in peer group reflection had added value in that it enhanced participants to generate concrete plans to improve clinical teaching. Participants in peer group reflection experienced that peers often encountered similar problems, which helped them to reflect on their student ratings and elaborate on ways how to improve clinical teaching. As such, structured peer group reflection, moderated by trained faculty, in which the participants had to address learning questions raised by peers and based on student ratings, affords clinical teachers an opportunity to answer the feed-forward question. Answering this feed forward question can have a powerful impact on learning (Hattie and Timperley Citation2007) and this may boost clinical teachers’ professional development (Boerboom et al. Citation2015).

This study has some limitations, of which the first and most important one is that time-on-task differed in both feed-forward facilitating strategies we studied. Failing to take the time-on-task into account is one of the common pitfalls of experimental research (van Loon et al. Citation2013). Consequently, we may have overestimated the differences between both groups especially in the levels of alternative methods and plans. The small sample size of this quasi-experiment is a second limitation. We could only include a small number of participants, mainly due to the fact that there were not yet sufficient clinical teachers available which we could provide with feedback based on enough student ratings, since the clinical rotation in its current form only started in January 2015. We therefore had to decide not to follow Dolmans and Ginns’ (Citation2005) recommendation to preferably use at least six student ratings per teacher or more as did Boerboom et al. (Citation2011) in their study on the effect of peer group reflection. Instead we used at least three student ratings. Some participants experienced the use of limited student ratings for this reason as negative which could have had an effect on the outcomes of this study. A third limitation is that participants, possibly due to time constraints, wrote relatively short sentences and sometimes only a few words in their reflection reports. This made it difficult to come to a consensus on the level of reflection proven the low interrater agreement after the first round. A fourth limitation is that the teachers within the two groups differed in their mean overall student performance score (8.3 for strategy A and 7.7 for strategy B), due to which it could be possible that the teachers in strategy B had more room for generating plans to improve as compared to those involved in strategy A.

Practical implications of this study encompass the possible role of peer group reflection on student ratings in faculty development. Based on this study and supported as well by the study of Boerboom et al. (Citation2011) we demonstrated that peers can be viewed as instructional resources for one another, sharing criteria for success as advocated by Black and Wiliam (Citation2009). Since time and commitment is required to accomplish this type of peer group reflection, we might consider as a next step to conduct a kind of peer group reflection via a digital modality, like for example a webinar, in order to decrease time commitment for busy clinical supervisors.

In this study, we did not investigate whether the proposed plans to improve clinical teaching were actually implemented by the clinical teacher and whether this leads to better performance in clinical teaching as observed by students in the workplace of the particular clinical teacher. We welcome therefore future research into the question of whether the quality of clinical teaching actually improves in practice as a result of the improvement plans generated in dialog with peers about student ratings during peer group reflection meetings as proposed in this study. We suggest as well more qualitative studies, delving into the experiences of clinical teachers with peer group reflection, finding out more about the role of the moderator and how clinical teachers interact with each other during peer group reflection and to which extent this enhances setting goals for improvement.

Notes on contributors

Marion van Lierop, MD, MHPE, GP, Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands

Laury de Jonge, MD, PhD candidate, GP, Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands

Job Metsemakers, MD, PhD, GP, Professor of Family Medicine, Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands

Diana Dolmans, PhD, Professor of Innovative Learning Arrangements, School of Health Professions Education, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands

Supplementary_appendices.pdf

Download PDF (93 KB)Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the clinical teachers who participated and moderators of the peer group reflection meetings for dedicating their time and effort to this study. The authors are also grateful to Diana Riksen for providing the student evaluation data used in this study, Marlies Noevers for her support in facilitating the peer group reflection meetings, Renée Stalmeijer for her feedback on the research proposal, Tobias Boerboom for supplying the principal researcher with the outlines of the structured reflection report used in his research and Ineke Wolfhagen for her feedback on the draft of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Beijaard D, Vries YD. 1997. Building expertise: a process perspective on the development or change of teachers’ beliefs. Eur J Teach Educ. 20:243–255.

- Black P, Wiliam D. 2009. Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educ Asse Eval Acc. 21:5–31.

- Boerboom TB, Jaarsma D, Dolmans DH, Scherpbier AJ, Mastenbroek NJ, van Beukelen P. 2011. Peer group reflection helps clinical teachers to critically reflect on their teaching. Med Teach. 33:615–623.

- Boerboom TBB, Stalmeijer RE, Dolmans DHJM, Jaarsma DADC. 2015. How feedback can foster professional growth of teachers in the clinical workplace: a review of the literature. Stud Educ Eval. 46:47–52.

- Dolmans DH, Ginns P. 2005. A short questionnaire to evaluate the effectiveness of tutors in PBL: validity and reliability. Med Teach. 27:534–538.

- Dornan T, Boshuizen H, King N, Scherpbier A. 2007. Experience-based learning: a model linking the processes and outcomes of medical students' workplace learning. Med Educ. 41:84–91.

- Dornan T, Tan N, Boshuizen H, Gick R, Isba R, Mann K, Scherpbier A, Spencer J, Timmins E. 2014. How and what do medical students learn in clerkships? Experience based learning (ExBL). Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 19:721–749.

- Eva KW, Regehr G. 2008. “I’ll never play professional football” and other fallacies of self-assessment. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 28:14–19.

- Hattie J, Timperley H. 2007. The power of feedback. Rev Educ Res. 77:81–112.

- Hatton N, Smith D. 1995. Reflection in teacher education: towards definition and implementation. Teach Educ. 11:33–49.

- Hendriksen J. 2009. Handboek intervisie [a guide to peer coaching]. Amsterdam: Boom/Nelissen.

- Hirsh DA, Ogur B, Thibault GE, Cox M. 2007. “Continuity” as an organizing principle for clinical education reform. N Engl J Med. 356:858–866.

- Holmboe ES, Ward DS, Reznick RK, Katsufrakis PJ, Leslie KM, Patel VL, Ray DD, Nelson EA. 2011. Faculty development in assessment: the missing link in competency-based medical education. Acad Med. 86:460–467.

- Korthagen F, Vasalos A. 2005. Levels in reflection: core reflection as a means to enhance professional growth. Teachers Teach Theor Pract. 11:47–71.

- van Loon MH, Kok EM, Kamp RJ, Carbonell KB, Beckers J, Frambach JM, de Bruin AB. 2013. AM last page: avoiding five common pitfalls of experimental research in medical education. Acad Med. 88:1588.

- Pee B, Woodman T, Fry H, Davenport ES. 2002. Appraising and assessing reflection in students' writing on a structured worksheet. Med Educ. 36:575–585.

- Ramani S. 2006. Twelve tips to promote excellence in medical teaching. Med Teach. 28:19–23.

- Ramani S. 2015. Reflections on feedback: closing the loop. Med Teach. 38:206–207.

- Sandars J. 2009. The use of reflection in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 44. Med Teach. 31:685–695.

- Sargeant J, Mann K, van der Vleuten C, Metsemakers J. 2008. “Directed” self-assessment: practice and feedback within a social context. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 28:47–54.

- Sargeant JM, Mann KV, van der Vleuten CP, Metsemakers JF. 2009. Reflection: a link between receiving and using assessment feedback. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 14:399–410.

- Sluijsmans D, Joosten-ten Brinke D, van der Vleuten C. 2013. Toetsen met leerwaarde: Een reviewstudie naar de effectieve kenmerken van formatief toetsen. [Assessment with learning value: a systematic review of effective characteristics of formative assessment] Maastricht (the Netherlands): Reviewstudie uitgevoerd in opdracht van en gesubsidieerd door NWO-PROO. Projectnummer: 411-11-697. [Systematic review conducted on behalf of and funded by the Dutch Programme Council for Educational Research (PROO) of the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). Project number: 411-11-697]. Dutch.

- Stalmeijer RE, Dolmans DH, Wolfhagen IH, Peters WG, van Coppenolle L, Scherpbier AJ. 2010. Combined student ratings and self-assessment provide useful feedback for clinical teachers. Adv Health Sci Educ. 15:315–328.

- Steinert Y, Mann K, Centeno A, Dolmans D, Spencer J, Gelula M, Prideaux D. 2006. A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to improve teaching effectiveness in medical education: BEME Guide No. 8. Med Teach. 28:497–526.

- Tigelaar DE, Dolmans DH, Meijer PC, de Grave WS, van der Vleuten CP. 2008. Teachers’ interactions and their collaborative reflection processes during peer meetings. Adv in Health Sci Educ. 13:289–308.