Abstract

Background

To ensure high qualification standards in medical institutions, a questionnaire has been developed to evaluate the postgraduate medical education in Switzerland.

Aim

This article describes the development and longitudinal analysis of a questionnaire using eight scales to assess the quality of postgraduate medical education.

Method

The questionnaire has been administered to all residents every year since 2003. In 2020, 8,745 residents returned the questionnaire, resulting in a response rate of 70%. In addition, a survey is conducted annually among the directors of medical institutions.

Results

We present results of the directors’ survey and the resident evaluation from 2020, as well as longitudinal data over 16 years. The mean values of the eight scales remained stable or increased slightly over the years. The decision-making culture scale is generally rated best by the residents, while the evidence-based medicine scale is rated as the least good. The most important drivers of residents’ satisfaction with a training site are the work environment and leadership culture scales. The directors perceive the evaluation to be fair and useful.

Conclusions

The questionnaire represents a reliable and useful tool for the quality control in postgraduate medical training. It provides yearly feedback to the directors regarding how the residents perceive their training giving insights for improvments.

1. Introduction

Reliable quality control in postgraduate medical education is important in ensuring high qualification standards in postgraduate training. In the Swiss context, an instrument has been developed to evaluate the quality of postgraduate medical education. This instrument exists since 2003. The results are used by the Swiss Institute for Medical Education to identify training sites that do not perform well, and the results are used by its directors to improve postgraduate education at their training sites.

Practice points

The quality of the postgraduate medical education is measured using eight scales.

The directors of medical institutions can initiate improvements in their training based on the annual feedback.

The results of the evaluation help in identifying those training sites that do not perform well, and the results are also used by residents to select a medical institution.

The easiest way to measure the quality of postgraduate medical institutions is through a questionnaire that junior doctors use to evaluate the training at their medical institution. There have already been efforts to develop such questionnaires in some countries (e.g. Boor et al. Citation2011; Da Dalt et al. Citation2013; Roff et al. Citation2005). In the Netherlands, for example, Boor et al. (Citation2011) developed and validated a questionnaire with 50 items and eleven subscales to measure the learning climate of residency programs (Dutch Residency Educational Climate Test D-RECT). This questionnaire is partly utilized in hospitals in the Netherlands with various specialties (Lombarts et al. Citation2014; Silkens et al. Citation2018; van Vendeloo et al. Citation2018) and has already been revised once by Silkens et al. (Citation2016). An instrument that also contains the evaluation of the learning climate is the PHEEM (Postgraduate Hospital Educational Environment Measure) questionnaire (Roff et al. Citation2005). This questionnaire has been applied in England, Scotland, and Denmark at hospitals of various specialties (Aspegren et al. Citation2007; Clapham et al. Citation2007) and also in some countries outside Europe (Binsaleh et al. Citation2015; Ezomike et al. Citation2020). Another example is the Resident Assessment Questionnaire, which was administered to pediatric doctors in Italy (Da Dalt et al. Citation2013). Nevertheless, these questionnaires are not regularly used in a nationwide context and only cover some aspects of postgraduate medical education.

The aim of the instrument described in the present paper is to evaluate all important aspects of postgraduate medical education and provide feedback to the directors of the medical training sites regarding how the residents perceive their training. The questionnaire has been administered to all residents in Switzerland every year since 2003 (Siegrist and Giger Citation2006; van der Horst et al. Citation2010, Citation2011). It is an important instrument for evaluating and securing the qualification standard of the Swiss postgraduate medical institutions. This article describes the development of this questionnaire; provides results of the directors’ survey, as well as the results of the resident evaluation from 2020; and shows longitudinal data over 16 years. Furthermore, we examined which factors most strongly influence the overall satisfaction with postgraduate medical institutions.

2. Methods

2.1. Setting

In Switzerland, medical students receive their medical diploma after 6 years of undergraduate study and passing the Federal Licensing Examination. Afterward, they can attend postgraduate medical training programs in a Swiss hospital or another medical institution in order to receive one of the 45 specialist titles. The postgraduate training programs for residents last between 5 and 6 years on average. Residents have to change hospitals or rotate within the medical institution to different positions in other specialties during their postgraduate training. We use the term ‘resident’ to refer to a junior doctor who is undertaking such specialty training. In Switzerland, every medical institution requires specific accreditation as a postgraduate medical training site to be allowed to educate residents (MedBG Citation2004). Accreditations are applied for by the directors of the training sites and issued by the Swiss Institute for Medical Education. It is mandatory for medical training institutions to take part in an annual evaluation to assess the quality of these training sites (Giger and Siegrist Citation2003a). The yearly evaluation consists of two parts: first, the directors of the medical training sites receive an online survey in which they indicate, among other things, how many residents are currently enrolled in their medical training program. Secondly, based on this information, the number of questionnaires needed for the yearly survey among residents will be sent to the directors. The residents fill out this questionnaire in order to evaluate the postgraduate training received at their respective institutions. At the end of the year, each medical training site receives an individual report containing the results of the survey on how their training was evaluated. The aggregated results for each medical training site are transparent and publicly accessible (SIWF Citation2020). Postgraduate medical training sites that do not meet a certain threshold regarding the evaluation are reported to the Swiss Institute for Medical Education, and if necessary, on-site visits can be ordered to control the teaching situation in such institutions. If the postgraduate medical training in an institution does not meet the required quality criteria, the accredition of a training site can be changed to provisional, or as ultima ratio, the accredition may be withdrawn.

2.2. The resident questionnaire

2.2.1. Development

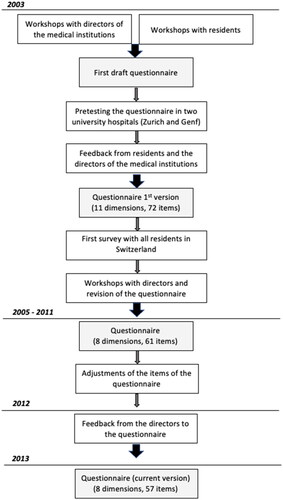

shows the flowchart depicting the process of developing the questionnaire used to evaluate the quality of Swiss postgraduate medical education.

In 2003, the initial topic areas (hereinafter called scales) and items of the resident questionnaire were developed in two workshops, one with directors of the medical training sites and one with representatives of the residents. Thus, all stakeholders were able to contribute to the selection of the criteria that should be used for measuring the quality of Swiss postgraduate medical education. In a next phase, the questionnaire was pretested with residents from the University Hospitals of Zurich and Geneva. The new questionnaire was positively evaluated, and the scope of the questionnaire was found to be acceptable (Giger and Siegrist Citation2003a). At this stage, the questionnaire included nine scales (topic areas). The questionnaire was distributed to all Swiss residents in summer 2003, and 67% of the residents filled out the questionnaire (N = 5,361) (Giger and Siegrist Citation2003b). Subsequently, another round of workshops was held with selected directors of the medical training sites, and the questionnaire was revised again. From 2005 to 2011, small adjustments were made to some items on the questionnaire each year. In 2012, the questionnaire was slightly modified based on the input received from the stakeholders. Since then, the questionnaire has remained in its current version (see Table A1 in the Supplementary Materials).

2.2.2. Measurements

The questionnaire consists of various questions related to the training site, the working conditions, and personal details regarding the resident. In addition, each year, the questionnaire contains some ad hoc questions that cover current topics in postgraduate medical education.

The quality of the postgraduate medical education is measured with 57 items that can be divided into the following eight scales: overall assessment, professional competencies, leadership culture, incident reporting, work environment, learning culture, decision-making culture, and evidence-based medicine. For answering the questions, a 6-point Likert Scale is used, where 1 = does not apply at all and 6 = fully applies. Furthermore, the scale professional competencies also includes a not-applicable option. The final score for each scale is the mean value of the associated items. The questionnaire, with the items, can be found in Table A1, in the Supplementary Materials.

2.2.3. Data collection

The questionnaire is in a paper-and-pencil format and is available in German, Italian, or French to cover the main spoken national languages of Switzerland. The residents return the questionnaires directly via mail and anonymously to ETH Zurich. Participation is voluntary for residents.

The total number of residents enrolled in medical training programs has steadily risen over the years since the first survey in 2003. While, in 2003, 8,001 residents were reported by the directors, the number of postgraduate medical positions has increased to 12,475 in 2020. The number of respondents to the annual resident evaluation has increased to the same extent, resulting in a response rate of between 65 and 70% every year. In 2020, 8,745 (56% women, 44% men) residents returned the completed questionnaire, which represents a response rate of 70%.

This response rate is high for a voluntary evaluation. Comparatively, other national surveys with surgical residents achieved a response rate of 43.2% on average (Yarger et al. Citation2013).

2.3. The directors survey

In addition to the yearly resident evaluation, a survey (available in German or French) among the directors of the medical training sites has also been conducted every year since 2004 prior to the resident evaluation. The directors survey consists of two parts: first, the directors are asked about the current number of residents enrolled in their postgraduate medical training program. The second part comprises an annually changing set of specific questions on current topics in postgraduate medical education. The survey is mandatory for directors, resulting in a response rate of approximately 95%. In 2020, a total of 1,629 medical training institutions existed in Switzerland, and all of their directors were addressed.

2.4. Data analysis

All analyses were conducted in SPSS 26.0. We used Pearson’s correlation analyses to quantify the associations between the variables. The mean values and standard deviations of the scales were calculated for the most recent year, 2020, and for each year from 2005 onward to allow for a long-term comparison. Cronbach’s alpha from 2020 was calculated to indicate the reliability of the scales. To examine the influence of the seven other scales on the overall assessment scale, we performed a multiple linear regression analysis for the entire sample using the most recent data, from 2020. To investigate how the training sites that did not perform well in 2019 improved in 2020, the mean values of the overall score of these training sites were calculated.

3. Results

3.1. Results of the resident survey

3.1.1. Results from 2020

The Cronbach’s alpha values of the eight scales range between 0.78 and 0.96, indicating high reliability of the scales (see ). The decision-making culture was assessed most positively overall (M = 5.10, SD = 0.87), followed by work environment (M = 4.96, SD = 1.05), incident reporting (M = 4.95, SD = 0.93), professional competencies (M = 4.88, SD = 0.76), learning culture (M = 4.83, SD = 0.95), overall assessment (M = 4.83, SD = 1.15), leadership culture (M = 4.82, SD = 1.09), and, finally, evidence-based medicine (M = 4.48, SD = 1.09). Overall, the scales have relatively high mean values. Nevertheless, evidence-based medicine still has potential for improvement.

Table 1. Data of the eight scales from the survey year 2020. Valid cases (N), mean values (M), standard deviations (SD), and Cronbach’s alpha.

Table 2. Results of the linear regression analysisa with overall assessment as the dependent variable for the overall sampleb.

Additional analyses showed that the ratings of the scales differ depending on how long a person has been in postgraduate training. We found that the duration of postgraduate medical training is positively associated with the evaluation of the scales professional competencies (Pearson r = .11, p < .001), learning culture (r = .07, p < .001), leadership culture (r = .03, p < .01), incident reporting (r = .07, p < .001), decision-making culture (r = .04, p < .01), and evidence-based medicine (r = .12, p < .001). Overall, the correlation coefficients are rather small. No significant correlation was found for the overall assessment and the work environment scale.

3.1.2. Regression model – Predictors of overall assessment

The scale overall assessment summarizes residents’ total satisfaction with their medical training site. We wanted to better understand which factors most strongly influence overall assessment, and therefore conducted a linear regression analysis. The analysis was performed for the entire sample (N = 8,745). The model was significant (F (7,7828) = 3998.03, p < .001) and explained 78% of the variance. The results are shown in . The highest standardized regression weights were observed for work environment and leadership culture. Residents who were more content with their work environment or the leadership culture of their supervisors reported higher satisfaction with their medical training site as compared with residents who were less content. The third and fourth most important predictors of overall assessment were professional competencies and learning culture. The regression weights for decision-making culture and evidence-based medicine were very low. The effect of incident reporting was not significant. The results indicate that ‘soft factors’, such as work environment, have a much stronger influence on the overall satisfaction of the residents with their medical training site as compared to the knowledge they are taught in terms of technical skills, such as professional competencies or evidence-based medicine.

The regression analysis was also run separately for the seven largest specialties in Switzerland (general internal medicine, anaesthesia, surgery, gynaecology and obstetrics, paediatrics and adolescent medicine, psychiatry and orthopaedic surgery), and this analysis led to the same results.

3.1.3. Long-term data

Comparing the data longitudinally from 2005 onward, it can be seen in that the mean values of the eight scales have remained stable or increased very slightly. For example, the mean value of the overall assessment scale has remained consistently high over the years, varying between 4.74 (the lowest value, in 2011) and 4.87 (the highest value, in 2018). The resident ratings of professional competencies increased the most over the years (min (2007): 4.58; max (2019): 4.88), as did those of evidence-based medicine (min (2011): 4.28; max (2019): 4.49). Nevertheless, evidence-based medicine has the lowest average value not only in 2020 but also on a longitudinal basis. However, the values of the eight scales are all clearly above the scale mean of 3.5.

Table 3. Mean values (M) of the eight scales since 2005. .

In conclusion, the consistently high ratings of the eight scales show that the qualification standards of postgraduate medical education could be maintained at a high level over a long period of time.

3.1.4. Training sites with a poor evaluation

Postgraduate medical training sites with an overall score of less then 3.5 are selected for on-site visits to control the teaching situation. The overall score is calculated by averaging all eight scales (with the overall assessment and professional competencies scales weighted twice, as they are considered most important by directors and residents). Overall, the number of training sites with insufficient overall scores has decreased each year (2013: 28 training sites, 2020: 19 training sites), even tough the total number of training sites with an accreditation has increased each year. Further, training sites with a low overall score each improved significantly in the following year (e.g. M2019= 2.95, M2020= 4.74; t(18) = −6.69, p < .001). This suggests that external encouragements pointing on the training quality may have had a positive influence on the training sites.

3.2. Results of the directors survey

3.2.1. Impact of the resident evaluation on postgraduate medical training 2005–2009

The directors of the medical institutions were asked whether the results of the survey had an impact on their training program and how fairly they perceived the residents’ evaluation. These data were only collected between 2005 and 2009. The data show that more than half of the directors perceived the residents’ evaluation of their medical training site to be fair (see ). A minority, 8.4–15.2%, of the directors were convinced that their training site had not been evaluated fairly (does not apply (at all)). Furthermore, between 39.5 and 44.1% of directors indicated that the results of the evaluation had caused them to think about their postgraduate education (see ). Moreover, the results motivated 34.1–38.1% of the directors to initiate concrete changes in their education programs (see ). In terms of numbers, this applies to 300 to 400 directors in Switzerland who are willing to reconsider their training program and who are even motivated to apply changes on their education. In addition, the data show that these 300 to 400 directors manage larger medical training sites with more residents on average. A high correlation indicated that directors who are willing to rethink their postgraduate training are also motivated to initiate changes (2009: Pearson r = .64. p < .001).

Table 4. Percentages of directors’ responses to the statement ‘The results of our medical training site were fair’ 2005–2009.

Table 5. Percentage of directors’ responses to the statement ‘The results of the survey made me rethink our postgraduate training‘ 2005–2009.

Table 6. Percentage of directors’ responses to the statement ‘Feedback from the survey have motivated me to initiate changes‘ 2005–2009.

In 2020, the directors were asked again whether they perceived the residents’ evaluation of their medical training site in the previous year to be fair, and 87.7% of directors agreed (fully). In addition, 62.9% stated that the results (rather) positively influenced their motivation for the survey.

These results demonstrate that the annual evaluation among residents is a useful instrument to initiate improvements in postgraduate training based on the results, and the evaluation is also supported by a large majority of the directors of the medical training sites. Furthermore, the results demonstrate that a large majority of directors are open to feedback and change.

4. Discussion

Since 2003, the Swiss Institute for Medical Education evaluates the quality of Swiss postgraduate medical institutions based on an annual survey among residents who attend such training sites to obtain specialist titles. The evaluation is conducted using a paper-and-pencil questionnaire which contains questions about the training site and the working conditions. The content of the questionnaire was developed together with directors of the medical institutions and residents.

The aim of the project is to provide yearly feedback to directors of the medical institutions regarding how the residents perceive their postgraduate training. These reports are of importance for the directors of medical institutions in Switzerland because training sites that do not meet a certain threshold are selected for on-site visits from experts, who evaluate the site in detail.

The present article reports the mean values of the eight scales of the questionnaire from the most recent survey year, 2020, as well as on the long-term data since 2005. According to the data, the values remained stable or increased slightly over the years. This might be due to the application of the questionnaire, as the annual feedback could have led to improvements within the different medical training sites. In terms of the different scales, the decision-making culture scale is usually rated highest by the residents, and the evidence-based medicine scale receives the lowest average rating per year and thus shows potential for improvement. The eight scales are also characterized by high reliability, as shown by the calculation of Cronbach’s alpha for 2020.

We identified the most important drivers of residents’ satisfaction with a training site. The results suggest that the work environment and leadership culture scales are the two most important predictors, indicating that residents with higher contentment regarding these two scales report higher overall satisfaction with their medical training site. These findings suggest that ‘soft factors’, such as work environment, have a stronger influence on the overall satisfaction of the residents than the professional knowledge imparted, such as the professional competencies scale. Other studies have reached similar conclusions; for example, Lu et al. (Citation2019) indicated that work environment was significantly related to the job satisfaction among nurses, and a study in the United States of surgical residents showed that job satisfaction was significantly predicted by workplace climate directly (Appelbaum et al. Citation2019).

The results of the directors’ survey from 2005 to 2009, presented in this article, show that the resident questionnaire and its evaluation were supported by a large majority of the directors. Furthermore, about 40% of the directors reported that they have rethought their postgraduate education training based on the results of the evaluation, and more than one-third wanted to initiate changes in their postgraduate medical education.

Some limitations need to be mentioned. First, the survey questions are formulated in general terms, so that they can be answered by all residents from different specialities. Therefore, some aspects of quality control cannot be covered such as the measurement of specific interventions or operations. Secondly, due to the anonymity granted to the residents, the answers cannot be linked to a specific person and their current achievements or grades of the residents. Accordingly, a direct external validation of the survey results is not possible. Nevertheless, the questionnaire covers a wide variety of important aspects related to the quality of postgraduate medical education in accordance with the literature (e.g. leadership culture and work environment (Sharok Citation2018)).

We are convinced that the survey instrument we present in this article is a reliable and useful tool for quality control in postgraduate medical training and serves the overall purpose of maintaining the high level of qualification standards of postgraduate medical education in Switzerland. Although the requirements and framework conditions of postgraduate medical education have changed over the years, our data indicate that its quality is still perceived to be high. Furthermore, the results of the evaluation not only help the Swiss Institute of Medical Education to identify training sites that do not perform well but also help residents to select a medical institution for their postgraduate education. Finally, our data show that the directors of the institutions perceive the evaluation to be fair and that it provides useful information for improving their postgraduate medical training.

Ethics

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of ETH Zurich (EK 2021-N-93).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (63.2 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the residents and directors who participated in the annual surveys. Moreover, we thank Prof. Heinz Gutscher for providing valuable input throughout the development of the assessment tool.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Larissa Luchsinger

Larissa Luchsinger, MA, is researcher in Consumer Behavior at ETH Zurich.

Anne Berthold

Anne Berthold, PhD, is researcher in Consumer Behavior at ETH Zurich.

Monika Brodmann Maeder

Monika Brodmann, MD, MME, is president of the Swiss Institute of Medical Education.

Max Giger

Max Giger, MD, is former president of the Swiss Institute of Medical Education.

Werner Bauer

Werner Bauer, MD, is former president of the Swiss Institute of Medical Education.

Michael Siegrist

Michael Siegrist, PhD, is professor in Consumer Behavior at ETH Zurich.

References

- Appelbaum NP, Lee N, Amendola M, Dodson K, Kaplan B. 2019. Surgical resident burnout and job satisfaction: the role of workplace climate and perceived support. J Surg Res. 234:20–25.

- Aspegren K, Bastholt L, Bested KM, Bonnesen T, Ejlersen E, Fog I, Hertel T, Kodal J, Lund J, Madsen JS, et al. 2007. Validation of the PHEEM instrument in a danish hospital setting. Med Teach. 29(5):498–500.

- Binsaleh S, Babaeer A, Alkhayal A, Madbouly K. 2015. Evaluation of the learning environment of urology residency training using the postgraduate hospital educational environment measure inventory. Adv Med Educ Pract. 6(6):271–277.

- Boor K, Van Der Vleuten C, Teunissen P, Scherpbier A, Scheele F. 2011. Development and analysis of D-RECT, an instrument measuring residents’ learning climate. Med Teach. 33(10):820–827.

- Clapham M, Wall D, Batchelor A. 2007. Educational environment in intensive care medicine—use of Postgraduate Hospital Educational Environment Measure (PHEEM). Med Teach. 29(6):184–191.

- Da Dalt L, Anselmi P, Bressan S, Carraro S, Baraldi E, Robusto E, Perilongo G. 2013. A short questionnaire to assess pediatric resident’s competencies: the validation process. Ital J Pediatr. 39(1):1–8.

- Ezomike UO, Udeh EL, Ugwu EO, Nwangwu EL, Nwosu NI, Ughasoro MD, Ezomike NE, Ekenze SO. 2020. Evaluation of postgraduate educational environment in a nigerian teaching hospital. Niger J Clin Pract. 23(11):1583.

- Giger M, Siegrist M. 2003a. Ein neuer Fragebogen zur Beurteilung der Weiterbildungsstätten – was soll das? [A new questionnaire to evaluate postgraduate medical institutions – What’s the point?]. SAEZ. 84:nr 31.

- Giger M, Siegrist M. 2003b. Ärztliche Weiterbildung auf dem Prüfstand [Postgraduate medical training under test]. SAEZ. 84(50):2655–2657.

- Lombarts KM, Heineman MJ, Scherpbier AJ, Arah OA. 2014. Effect of the learning climate of residency programs on faculty’s teaching performance as evaluated by residents. PLoS One. 9(1):e86512.

- Lu H, Zhao Y, While A. 2019. Job satisfaction among hospital nurses: a literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 94:21–31.

- MedBG Medizinalberufegesetz. Weiterbildungsgänge § 25. 2004.

- Roff S, McAleer S, Skinner A. 2005. Development and validation of an instrument to measure the postgraduate clinical learning and teaching educational environment for hospital-based junior doctors in the UK. Med Teach. 27(4):326–331.

- Sharok V. 2 018. Role of socio-psychological factors of satisfaction with education in the quality assessment of university. Int J Qual Res. 12(2):281–296.

- Siegrist M, Giger M. 2006. A Swiss survey on teaching evidence-based medicine. Swiss Med Wkly. 136(47–48):776–778.

- Silkens ME, Smirnova A, Stalmeijer RE, Arah OA, Scherpbier AJ, Van Der Vleuten CP, Lombarts KM. 2016. Revisiting the D-RECT tool: validation of an instrument measuring residents’ learning climate perceptions. Med Teach. 38(5):476–481.

- Silkens ME, Chahine S, Lombarts KM, Arah OA. 2018. From good to excellent: improving clinical departments’ learning climate in residency training. Med Teach. 40(3):237–243.

- SIWF Umfrage Weiterbildungsqualität. 2020. Bern: SIWF [accessed 2022 Jan 28]. https://siwf.ch/siwf-umfrage-weiterbildungsqualitaet/2020/.

- Van der Horst K, Siegrist M, Orlow P, Giger M. 2010. Residents’ reasons for specialty choice: influence of gender, time, patient and career. Med Educ. 44(6):595–602.

- Van der Horst K, Giger M, Siegrist M. 2011. Attitudes toward shared decision-making and risk communication practices in residents and their teachers. Med Teach. 33(7):e358–e36.

- Van Vendeloo SN, Brand PL, Kollen BJ, Verheyen CC. 2018. Changes in perceived supervision quality after introduction of competency-based orthopedic residency training: a national 6-year follow-up study. J Surg Educ. 75(6):1624–1629.

- Yarger JB, James TA, Ashikaga T, Hayanga AM, Takyi V, Lum Y, Kaiser H, Mammen J. 2013. Characteristics in response rates for surveys administered to surgery residents. Surgery. 154(1):38–45.