Abstract

Peer-led assessment (PLA) has gained increasing prominence within health professions education as an effective means of engaging learners in the process of assessment writing and practice. Involving students in various stages of the assessment lifecycle, including item writing, quality assurance, and feedback, not only facilitates the creation of high-quality item banks with minimal faculty input but also promotes the development of students’ assessment literacy and fosters their growth as teachers. The advantages of involving students in the generation of assessments are evident from a pedagogical standpoint, benefiting both students and faculty. However, faculty members may face uncertainty when it comes to implementing such approaches effectively. To address this concern, this paper presents twelve tips that offer guidance on important considerations for the successful implementation of peer-led assessment schemes in the context of health professions education.

Introduction

Peer-led assessment (PLA) is increasingly used across health professions education to actively involve learners in assessment writing and practice. PLA schemes range in subjects from life support to multiple choice questions (MCQs) and can encompass all stages of the assessment lifecycle, from item writing to response feedback across healthcare disciplines (Harvey et al. Citation2012; Harris et al. Citation2015; Xavier et al. Citation2023). By engaging in PLA, learners contribute to the creation of a comprehensive, peer-generated item bank that facilitates not only their own, but their peers’ learning. Furthermore, learners also acquire a deeper understanding of assessment principles and practices, nurturing their development as future educators (Burgess and McGregor Citation2018). Institutions stand to benefit from the availability of a substantial bank of peer-generated materials that can be utilised as a formative or summative resource for current and future students.

While the pedagogical advantages of involving students in the generation of assessments are evident for learners and faculty members, implementation of such approaches may pose challenges for faculty members. These tips explore important considerations for the successful implementation of PLA for health professions educators, who are keen to harness the benefits of learner-sourcing. Although this article draws upon the authors’ experiences within undergraduate medicine, the tips have been intentionally designed to be transferable to various health professions education contexts and for all types of assessment items, ranging from knowledge-based to clinical skills assessments.

Tip 1

Define the aims of the scheme

Prior to the implementation of any PLA scheme, it is imperative to have a clear understanding of its objectives and desired outcomes, for both faculty members and the targeted learner audience. Although the existing literature on PLA in health professions education is limited, it does offer valuable insights into the benefits associated with introducing such an educational initiative, which can inform these aims.

For learners, engaging in PLA activities has demonstrated positive effects on future assessment performance (Heinke et al. Citation2013; Walsh et al. Citation2016; Walsh et al. Citation2018; Mushtaq et al. Citation2020). This improvement can be attributed to the process of crafting questions for peers as well as the repeated practice of answering questions from the item bank, which aids in identifying areas of misunderstanding or knowledge gaps.

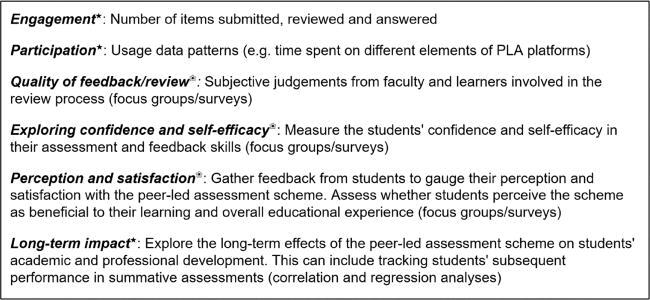

Metrics that can be employed to gauge the effectiveness of components within PLA writing schemes (❀qualitative approach, ★quantitative approach)

Additionally, PLA activities facilitate the development of crucial 21st-century learning skills, commonly known as the “4Cs”: communication, collaboration, creativity, and critical thinking (Thornhill-Miller et al. Citation2023). By actively participating in question writing, reviewing, and answering, learners enhance their own assessment literacy. This is particularly important given the established positive correlation between deeper comprehension of the assessment process and enhanced assessment outcomes (Price et al. Citation2010).

From a faculty perspective, the availability of a cost-effective yet potentially extensive formative item bank generated by learners can help address institutional resource and staffing constraints, while also fulfilling students’ ongoing demand for additional learning and assessment materials. Furthermore, involving a diverse cohort of students in PLA schemes allows for the generation of varied assessment content that might otherwise be overlooked. In establishing these potential aims, it is helpful to determine appropriate metrics for evaluating success, as exemplified in Box 1.

Tip 2

Co-design with stakeholders

When developing an educational project, it is crucial to engage in early consultation with all relevant stakeholders to cultivate a sense of ownership and foster engagement, thereby enhancing the project’s likelihood of success. Ideally, the integration of peer-led writing schemes should be aligned with the institution’s educational strategy and curricula, as outlined in Tip 3. Consequently, the organisers should collaborate with faculty colleagues to establish the scheme’s objectives, format, and intended delivery approaches.

In the context of health professions education, the optimisation of inter-professional learning opportunities should be a priority (Thistlethwaite Citation2012). Thus, it is important to consider involving colleagues from disciplines beyond the immediate course or program, exploring collaborative approaches wherein learners from different backgrounds contribute to a shared section of the item bank.

Understanding the perspectives of the target end-audience is paramount. Therefore, consider consultation exercises, including needs assessments, with learners to assess their interests, needs, and perceived challenges. Insights can then inform the design and implementation of the scheme. Furthermore, engaging learners during the design phase can enhance their motivation and commitment to the initiative once implemented.

Depending on the design of the peer-led assessment scheme, stakeholders may also include colleagues from administration, professional support teams, and eLearning services. During these discussions, it is essential to identify resource requirements and consider strategies to address potential resource limitations effectively. Additionally, exploring the possibility of involving patients and the public can ensure that the scheme maintains a patient-centred approach and minimises the potential for introducing biases or misalignments.

Tip 3

Align with the learners’ educational journey

The implementation of PLA schemes should be approached in a manner that harmonises with learners’ educational journey and aligns with the pedagogic philosophy of the institution. It is essential to establish the focus of the approach, such as whether the scheme will revolve around a specific assessment type (e.g. multiple-choice questions or Objective Structured Clinical Examinations) and whether it will be applicable to a particular module, unit, or extend across multiple year groups. Moreover, exploring the potential for interprofessional learning is crucial to facilitate collaboration and knowledge exchange among students from different disciplines.

Constructive alignment, a well-recognised principle in education, is a fundamental framework for any educational initiative, wherein intended learning outcomes (ILOs), teaching activities, and assessment tasks are interconnected. Therefore, in PLA schemes, the process of assessment item writing should be conducted in close conjunction with the program’s ILOs and teaching approach. Participants should have access to ILO curriculum maps and assessment blueprints to guide their writing efforts, ensuring that the generated items closely align with the formal curriculum and other formative and summative assessment activities already implemented in the program.

In the medium to long term, participation in PLA schemes could cultivate an interest in medical education as a discipline. Therefore, faculty members should consider providing opportunities for participants to share their experiences, enabling them to explore the underlying pedagogy of the scheme and its broader implications for educational principles and practice.

Tip 4

Implement quality assurance processes

Quality control and assurance are paramount in addressing concerns among staff and students regarding peer-generated content (Abdulghani et al. Citation2017). To achieve this, it is crucial to conduct initial pilot testing of the scheme with a small user group to identify issues and areas for improvement. This can then be used to inform final implementation.

A key approach to quality assurance of PLA schemes is to ensure that the items themselves are carefully scrutinised prior to their inclusion in the question bank. Assessment drives learning (Wormald et al. Citation2009) and therefore it is imperative that even formative questions are accurate and reflect current knowledge and practice. Consequently, item review assumes a critical role in ensuring validity of submitted questions, while also aligning them with established formats and house-style conventions. This role of item review is discussed further in Tip 6.

Once items are made available in the bank, performance data can be generated and analysed. Poorly functioning items, such as those with excessively high or low facility levels or poor discrimination, should undergo further review. The review decision may involve modifying the item to improve its quality, retiring the item, or allowing the item to remain if it tests core knowledge. As clinical practice evolves, mechanisms should be in place for users to highlight items that may become outdated or contrary to current practice, triggering a review process. Lastly, the role of training and supporting item writers and reviewers cannot be overstated in terms of quality assurance, so much so that these are afforded tips of their own.

Tip 5

Guide and support writers

Item writing encompasses both art and science. A skilled writer must employ creative thinking and strive for originality while adhering to standardised guidelines and considering the assessment’s level of complexity. To facilitate item construction, learners can be provided with an item writing guide including standards of item format including structure, content, language, tone and any word limits. These templates can be created de novo or adapted from existing guides (EBMA Citation2016; Walsh et al. Citation2017).

The writing guide can prompt the author to write their item to the desired level of performance according to Miller’s pyramid. For instance, single-best answer questions typically aim to assess the application of knowledge rather than simple rote recall. Furthermore, authors can be encouraged to incorporate higher-order thinking skills by designing questions that require multiple steps of reasoning. For instance, a question might prompt the responder to identify a likely diagnosis based on a clinical scenario before commenting on the optimal management approach.

When developing clinically-oriented questions, authors should consult up-to-date guidelines to ensure accuracy and alignment with everyday medical practice. Copyright issues, particularly regarding the use of images, should be clearly addressed to prevent occurrence.

Regardless of the item type, authors should craft their questions to eliminate irrelevant details and avoid including ‘clues’ that could be identified by testwise candidates. In single-best answer questions, care should be taken to ensure that the correct answer is not significantly longer than the distractors, and in OSCE (Objective Structured Clinical Examination) scripts, the use of vocabulary that strongly suggests a specific diagnosis should be avoided. Providing authors with a list of common test wise flaws can be beneficial in minimising the introduction of such issues into the questions (Walsh et al. Citation2017).

Although item writing is typically an individual endeavour, we recommend conducting item-writing workshops where learners can write, discuss and share items. This collaborative approach helps build confidence and skills in item-writing. Specialist platforms and artificial intelligence tools can aid in collaboration and distractor generation (as discussed in Tip 9).

Tip 6

Provide training and assistance to reviewers

Reviewing assessment items is helpful in enhancing their quality (Malau-Aduli and Zimitat Citation2012; Harris et al. Citation2015). The objectives of item review include verifying factual accuracy, addressing formatting, grammar, and syntax issues, eliminating unnecessary information, and identifying technical flaws that may inadvertently aid the test wise candidate or introduce unwarranted difficulty (Billings et al. Citation2020). Consistent with our recommendation for item authors, we advocate the use of a review template to facilitate such systematic critique and ensure generated items align with curriculum and author goals (Walsh et al. Citation2016). This template can be provided by the faculty in line with house style for different assessment types.

The use of fellow students as peer reviewers offers a useful approach to achieve these aims, and it has demonstrated efficacy in enhancing the quality of PLA items (Best et al. Citation2016). Peer review can potentially relieve faculty members of the burden of reviewing all submitted items. Recruiting students from more senior year groups, other disciplines, or post-graduate training programs to review items can help introduce essential expertise. Faculty-led training sessions and accompanying handbooks with tips on how to deliver and receive both positive and negative feedback to student peers are a helpful training approach before and throughout a PLA. More senior students who have acted as reviewers previously can help in running such events. We suggest at least one such session should be conducted at the start of the PLA, with more sessions planned depending on the length of the scheme. Involving faculty colleagues as final reviewers can provide a valuable last check before item publication. The combination of peer and expert review has demonstrated the ability to generate MCQs of comparable quality to those found in summative examinations (Harris et al. Citation2015).

Similar to item writing, item reviewing can be conducted individually or in group settings, wherein the review process itself serves as a valuable learning experience for all participants. Employing an iterative and multi-stage review approach can be advantageous. This approach involves sequential peer reviews conducted by students, followed by a senior review, ultimately leading to the acceptance of a formative item.

Tip 7

Facilitate effective feedback

Feedback plays a crucial role in the learning process; however, it is often underutilised (Hattie and Timperley Citation2007). In the context of PLA, feedback on item quality can originate from either peers or faculty members, facilitating improvements in the quality of assessments and promoting learning. Feedback can be provided during the review stage before the items are included in the item bank, as well as during ongoing interactions among users as questions are answered. This feedback can take the form of free-text comments for the item author and/or be expressed through rating scales. A checklist can be helpful to direct students as to what to look out for. For instance in MCQs, this could involve vigilance around avoiding negative questions and making sure the answers are ordered alphabetically (evaluation of the PLA scheme and its output is covered in detail in Tip 12).

Research has demonstrated that peers engaged in assessment activities can offer feedback that is at least as valuable as that provided by expert faculty members (Reiter et al. Citation2004). However, other work has also indicated that students may exhibit hesitancy in providing honest feedback due to apprehensions about jeopardising their relationships with peers (Biesma et al. Citation2019). Consequently, a preponderance of mainly positive feedback tends to prevail (Hussain et al. Citation2020). The incorporation of anonymisation techniques in the feedback process presents a viable approach to Encourage more comprehensive and candid feedback. Care should be exercised to avoid excessively negative feedback, given its negative impact on students’ motivation and self-esteem (Murdoch-Eaton and Sargeant Citation2012). Accordingly, learners need guidance to cultivate their skills in exchanging and utilising constructive feedback with their peers (Lerchenfeldt and Taylor Citation2020).

Tip 8

Motivate engagement

Learner motivation encompasses both intrinsic and extrinsic drivers, which play significant roles in shaping their engagement. Within the context of PLA, the desire to enhance academic performance typically serves as the primary intrinsic motivator (Harris et al. Citation2015). Additionally, other intrinsic motivators may include assisting peers through the contribution of cohort-generated content and the aspiration to gain early insights into the field of medical education.

Extrinsic motivators can be fostered through the integration of gamification elements into the PLA scheme. Gamification involves incorporating game-design principles into non-gaming contexts to enhance user engagement and enjoyment. In the context of PLA, examples of gamification elements encompass:

Leaderboards: Displaying rankings of top authors based on the number of submitted items or ratings received, as well as top reviewers based on the number of items reviewed.

Performance graphs: Visual representations illustrating individual performance on items, which can be displayed according to discipline or type.

Badges, Certificates, Prizes: Offering rewards based on the aforementioned metrics to recognise and incentivise participants.

The incorporation of gamification elements can cultivate healthy competition among peers, stimulating their involvement in the PLA scheme. However, caution must be exercised to avoid demotivating learners who are already struggling (see Tip 11). Therefore, the focus of gamification should emphasise individual development and collaboration. Anonymity for users within the PLA scheme can also be beneficial in mitigating potential risks.

Tip 9

Select the most appropriate implementation strategy

A balance must be struck between the cost of implementing a technical solution versus in-person/physical solutions when implementing PLA schemes. Factors to be considered include ease of implementation, the long and short term cost-saving implications (e.g. construction of a secure item database) and additional tools in-built to ease assessment generation.

In-person approaches are valuable when resources are limited. One successful example involves students creating OCSE scenarios with faculty review. Students used these to conduct mock OSCE examinations, where different year groups serve as examiners, examinees, and standardised patients, garnering positive feedback from all stakeholders (Lee et al. Citation2018). Further, in-person review of MCQs in student study groups has also been effective (Harris et al. Citation2015). However, scalability of the PLA scheme is likely limited.

Several technological solutions facilitate PLA schemes, including PeerWise, PeerGrade, and SmashMedicine. PeerWise, a free website managed by the University of Auckland, enables students to create questions for their peers to answer and engage in discussions through individual question boards. However, concerns exist about demotivational student trolling and perceived question quality (Walsh et al. Citation2018), as well as the possibility of inaccurate material persisting without a robust review mechanism. Licensed solutions also exist to support PLA schemes. PeerGrade allows students to submit various assignment formats, such as essays and videos, for peer review. SmashMedicine focuses on MCQ generation to foster active learning. Using gamified incentives, students are encouraged to write questions followed by a two-stage review process. Initially, fellow students, either from the same course or of higher academic years, review and critique submitted questions. Subsequently, faculty staff conduct a final review to ensure the quality and relevance of the MCQs.

This enables the efficient production of a substantial volume of high-quality MCQs with minimal administrative input. Moreover, the platform fosters collaboration not only within courses but also across different educational institutions. By capitalising on its machine learning capabilities, SmashMedicine efficiently streamlines the process of generating distractors, thereby mitigating users’ time burden. These tools enhance scalability, collaboration, secure item bank generation and novel ways for learners to encounter new information.

Tip 10

Enable learners to use the resource effectively

It is important that learners are provided with guidance on how best to use PLA schemes, while also highlighting potential challenges and pitfalls. In order to foster active engagement, learners must develop an appreciation for the ways in which their involvement can enhance their own learning experiences. This can be achieved by emphasising the benefits of participating in various stages of the PLA lifecycle, rather than solely focusing on item completion. Actively writing and reviewing items for their peers can provide valuable learning opportunities. By understanding how and when to incorporate PLA as a complementary component, learners can maximise the benefits derived from the scheme. For instance, they can selectively choose items aligned with the current teaching focus to supplement their learning.

Moreover, learners should be encouraged to recognise that PLA extends beyond mere preparation for summative assessments. Emphasising the importance of spaced learning, whereby learners engage in consistent efforts over time, rather than resorting to cramming for summative assessments, can promote long-term retention of knowledge (Pumilia et al. Citation2020). Additionally, it is crucial to remind learners that the ultimate goal of learning is not limited to achieving high exam scores but rather to enhance their future performance in clinical practice.

Lastly, learners need to acknowledge that, as a peer-curated resource, the review process may not eliminate all inaccuracies. They should be prepared to verify the content by consulting additional resources as an integral part of the learning process.

Tip 11

Identify students in need of support

The prevalence of struggling medical students has been found to be as high as 10% to 15%, posing a significant risk of academic failure (Yates and James Citation2006); yet students are often hesitant to seek assistance despite facing difficulties (DeVoe et al. Citation2007). Consequently, health educators have a responsibility to identify struggling students (Frellsen et al. Citation2008), because early identification enables the provision of support for successful remediation (Kalet and Chou Citation2014). The implementation of PLA schemes presents a valuable approach to identifying such struggling learners.

The extent to which students engage with PLA schemes, as evidenced by metrics such as the number of questions submitted, reviewed, or answered, may offer insights into their overall engagement. However, since participation in these schemes is typically voluntary, the correlation between engagement metrics and academic performance is questionable. Analysing student performance on identified questions can also highlight underachieving individuals. Faculty members can then meet with these students, potentially uncovering underlying welfare or pastoral issues, as well as academic struggles, with the aim of devising action plans and referring students to additional support services (Evans et al. Citation2010). Early detection of struggling learners is crucial to successful remediation, and PLA schemes can provide an additional chance to identify these individuals and an opportunity to step in before high-stakes assessments (Rumack et al. Citation2017).

In PLA, peer-to-peer feedback, including commenting and rating each other’s contributions, can also help create a mutually supportive environment for all learners involved in the scheme. This environment can potentially provide isolated students with a support network. However, it is important to acknowledge that poor quality or critical peer feedback also carries the risk of demoralising struggling students further. Therefore, faculty should establish mechanisms for moderating feedback while simultaneously utilising them as indicators to identify learners who may be experiencing difficulties.

Tip 12

Evaluate, review and develop

Evaluation of the PLA scheme is recommended after each cycle. Revisit scheme goals and integrate stakeholder directions (outlined in Tip 2). It is likely the purpose of the scheme will align with the well-described benefits of PLA, which include improving student knowledge and reasoning skills, developing learners as teachers and creating a formative item bank (Thampy et al. Citation2023). The evaluation, review and development of the scheme must therefore be sculpted on the perceived importance of objectives.

A combination of both quantitative and qualitative measures may be helpful (Box 1). For example, if the primary aim of the scheme is to improve students’ academic performance, a correlation between scheme engagement, specifically the number of questions written, reviewed, and answered with summative examination results might be helpful. Longitudinal monitoring over a number of years of the course and career progression might also yield valuable insights. Qualitative assessment through surveys and focus groups gauging academic confidence, sense of community and increased faculty empathy are worthwhile. Additionally, this approach offers learners a chance to express the advantages or challenges they encountered when using the scheme which can be addressed in the next iteration. Overall, a major common driver of faculties implementing these schemes is to generate a formative bank, so the size of this can be assessed. Further, the performance of the PLA items in summative and formative tests can be assessed by item analysis, in particular discriminatory and distractor analysis.

It should be noted that all benefits of PLA schemes may take time to manifest, but it is helpful to work out how much time and effort the peer-produced item bank itself has saved the faculty. This is particularly relevant given that the cost of writing just one satisfactory MCQ has been estimated to be typically greater than $2400 (Wainer and Feinberg Citation2015). Such cost-benefit analysis can help illustrate the value of the scheme for key stakeholders and safeguard the scheme for future years.

Conclusion

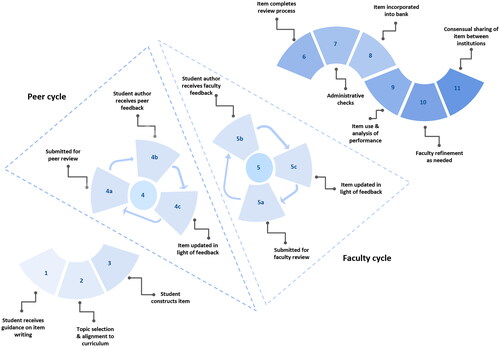

PLA schemes can significantly augment the academic journey of learners, allowing them to solidify their knowledge while simultaneously boosting their development as teachers and assessors. Institutions also gain in a number of ways including amassing a vast and continuously growing repository of peer-reviewed items for formative practice. Indeed, a suggested lifecycle which can create a high-quality PLA item is outlined in .

We hope these tips described will assist educators in effectively deploying this mutually beneficial educational strategy in both undergraduate and postgraduate settings. More widely, we believe this approach can foster an increased sense of community as whole within and across year groups and institutions.

Acknowledgments

BH would like to thank (1) EIT Health who have supported projects that have informed insights shared in this article, (2) Austin Lee who helped conceptualise the figure and with proofreading the manuscript (3) all students and staff who have worked on PLA schemes in which the authors have been involved.

Disclosure statement

BH, SH, JW have developed the online platform SmashMedicine, an educational website based on the concepts of peer-to-peer learning and gamification. This platform has been commended globally, including winning the Vice-Chancellor's Education Award from the University of Oxford.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Benjamin H. L. Harris

Benjamin H. L. Harris, MBBCh (Hons), MSc, DPhil, MRCP (UK) Fellow, HEA FacadMEd OA, is a doctor with a specialist interest in oncology, having a Masters and DPhil in this subject from the University of Oxford. He is a multi-award winning educationalist and lecturer at St. Catherine’s College, Oxford. He is particularly passionate about improving education for health professionals through evidence-based approaches and giving patients an increasing voice in curricula. He currently holds the prestigious Thouron Scholarship at the University of Pennsylvania.

Samuel R. L. Harris

Samuel R. L. Harris, BSc (Hons), is experienced in educational innovation and neuroscience. He holds an interest in cognitive science, specifically around how students learn, and connecting it to the practical implications for scalable teaching approaches. He has particular expertise in using peer-to-peer learning to enhance the quality of healthcare education.

Jason L. Walsh

Jason L. Walsh, BSc (Hons), MSc, MBBCh (Hons), MRCP (UK), is an interventional cardiology fellow at the John Radcliffe Hospital and a doctoral candidate at the University of Oxford. He has a keen interest in clinical teaching with a particular emphasis on small group teaching and peer-assisted learning.

Christopher Pereira

Christopher Pereira, BSc, MBBS PGCert (Merit), MRCP, MD(Res), is a hospital-based NHS doctor in Acute Internal Medicine and Geriatric Medicine. He is passionate about driving educational improvements for medical students, doctors, and the multi-disciplinary team.

Susannah M. Black

Susannah M. Black, BA (Oxon), BMBCh trained at the University of Oxford, is currently undertaking a Clinical Fellowship in Emergency Medicine in Jersey, Channel Islands.

Vincent E. S. Allott

Vincent E. S. Allott, BA (Hons) (Oxon), is a medical student at the University of Oxford. He has a burgeoning interest in improving the student learning experience through innovative approaches.

Ashok Handa

Ashok Handa, MA, FRCS FRCS(Ed), is Professor of Vascular Surgery at University of Oxford and Honorary Consultant Vascular Surgeon at the John Radcliffe Hospital. He has been the Director for Surgical Education for Oxford University since 2001. He is Director of the Collaborating Centre for Values-Based Practice in Health and Social Care based at St Catherine’s College and responsible for leading on education and research for the centre. He is Fellow in Clinical Medicine and Tutor for Graduates at St Catherine’s College. He has over 200 publications in vascular surgery, surgical education, patient safety and many on the topic of values-based practice, shared decision making and consent. He is the Principle Investigator of the OxAAA and OxPVD studies in vascular surgery. He is Co-PI of the Oxford University Global Surgery Research Group.

Harish Thampy

Harish Thampy, BSc (Hons), MB ChB (Hons), FRCGP, DFRSH, DRCOG, MSc (Med Ed), PFHEA, FacadMEd, is a Professor of Medical Education at the University of Manchester Medical School and is the MB ChB Associate Programme Director for Assessments. He has particular interests in professional identity as a clinical teacher, near-peer, and peer-assisted learning and clinical reasoning assessments.

References

- Abdulghani HM, Irshad M, Haque S, Ahmad T, Sattar K, Khalil MS. 2017. Effectiveness of longitudinal faculty development programs on MCQs items writing skills: a follow-up study. PloS One. 12(10):e0185895. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185895.

- Best RR, Walsh JL, Denny P, Harris BHL. 2016. “Peer Review: a Valuable Strategy for Improving the Quality of Student-Written Questions.” In. https://www.medicaleducators.org/write/MediaManager/Abstract_Book_2016.pdf.

- Biesma R, Kennedy M, Pawlikowska T, Brugha R, Conroy R, Doyle F. 2019. Peer assessment to improve medical student’s contributions to team-based projects: randomised controlled trial and qualitative follow-up. BMC Med Educ. 19(1):371. doi:10.1186/s12909-019-1783-8.

- Billings MS, DeRuchie K, Hussie K, Kulesher A, Merrell J, Morales A, Paniagua MA, Sherlock J, Swygert KA, Tyson J. 2020. NBME ITEM-WRITING GUIDE: constructing Written Test Questions for the Health Sciences. National Board of Medical Examiners. https://www.nbme.org/item-writing-guide.

- Burgess A, McGregor D. 2018. Peer teacher training for health professional students: a systematic review of formal programs. BMC Med Educ. 18(1):263. doi:10.1186/s12909-018-1356-2.

- Chou CL, Kalet A, Costa MJ, Cleland J, Winston K. 2019. Guidelines: the dos, don’ts and don’t knows of remediation in medical education. Perspect Med Educ. 8(6):322–338. doi:10.1007/s40037-019-00544-5.

- Cushing A, Abbott S, Lothian D, Hall A, Westwood OMR. 2011. Peer feedback as an aid to learning – what do we want? Feedback. When do we want it? Now!. Med Teach. 33(2):e105-12–e112. doi:10.3109/0142159x.2011.542522.

- DeVoe P, Niles C, Andrews N, Benjamin A, Blacklock L, Brainard A, Colombo E, Dudley B, Koinis C, Osgood M. 2007. Lessons learned from a study-group pilot program for medical students perceived to be ‘at risk. Med Teach. 29(2-3):e37–40–e40. doi:10.1080/01421590601034688.

- EBMA. Guidelines for item writing. 2016. Accessed July 27, 2023 https://www.ebma.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/EBMA-guidelines-for-item-writing-version-2017_3.pdf.

- Evans DE, Alstead EM, Brown J. 2010. Applying your clinical skills to students and trainees in academic difficulty. Clin Teach. 7(4):230–235. doi:10.1111/j.1743-498X.2010.00411.x.

- Frellsen SL, Baker EA, Papp KK, Durning SJ. 2008. Medical school policies regarding struggling medical students during the internal medicine clerkships: results of a national survey. Acad Med. 83(9):876–881. doi:10.1097/acm.0b013e318181da98.

- Harris BL, Walsh JL, Tayyaba S, Harris DA, Wilson DJ, Smith PE. 2015. A novel student-led approach to multiple-choice question generation and online database creation, with targeted clinician input. Teach Learn Med. 27(2):182–188. doi:10.1080/10401334.2015.1011651.

- Harvey PR, Higenbottam CV, Owen A, Hulme J, Bion JF. 2012. Peer-led training and assessment in basic life support for healthcare students: synthesis of literature review and fifteen years practical experience. Resuscitation. 83(7):894–899. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.01.013.

- Hattie J, Timperley H. 2007. The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research. 77(1):81–112. doi:10.3102/003465430298487.

- Heinke W, Rotzoll D, Hempel G, Zupanic M, Stumpp P, Kaisers UX, Fischer MR. 2013. Students benefit from developing their own emergency medicine OSCE stations: a comparative study using the matched-pair method. BMC Med Educ. 13(1):138. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-13-138.

- Hussain I, Mubashar A, Singh H. 2020. Final year medical students’ perspective on the use of peer assessments in the training of future doctors to obtain and provide quality feedback [Letter]. Adv Med Educ Pract. 11(11):693–694. doi:10.2147/amep.s283085.

- Kalet A, Chou CL. 2014. Remediation in Medical Education. New York: Springer.

- Lee CB, Madrazo L, Khan U, Thangarasa T, McConnell M, Khamisa K. 2018. A student-initiated objective structured clinical examination as a sustainable cost-effective learning experience. Med Educ Online. 23(1):1440111. doi:10.1080/10872981.2018.1440111.

- Lerchenfeldt S, Taylor TAH. 2020. Best practices in peer assessment: training tomorrow’s physicians to obtain and provide quality feedback [Response to Letter]. Adv Med Educ Pract. 11:851–852. doi:10.2147/amep.s289790.

- Maher BM, Hynes H, Sweeney C, Khashan AS, O’Rourke M, Doran K, Harris A, O’ Flynn S. 2013. Medical school attrition-beyond the statistics a ten year retrospective study. BMC Med Educ. 13(1):13. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-13-13.

- Malau-Aduli BS, Zimitat C. 2012. Peer review improves the quality of MCQ examinations. Assess Eval Higher Educ. 37(8):919–931. doi:10.1080/02602938.2011.586991.

- Murdoch-Eaton D, Sargeant J. 2012. Maturational differences in undergraduate medical students’ perceptions about feedback. Med Educ. 46(7):711–721. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04291.

- Mushtaq M, Mateen MA, Haider KH. 2020. Student-generated formative assessment and its impact on final assessment in a problem-based learning curriculum. Saudi J Health Sci. 9(2):77. doi:10.4103/sjhs.sjhs_98_20.

- Nemec EC, Welch B. 2016. The impact of a faculty development seminar on the quality of multiple-choice questions. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 8(2):160–163. doi:10.1016/j.cptl.2015.12.008.

- O’Neill LD, Morcke AM, Eika B. 2016. The validity of student tutors’ judgments in early detection of struggling in medical school. A prospective cohort study. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 21(5):1061–1079. doi:10.1007/s10459-016-9677-6.

- Price M, Carroll J, O’Donovan B, Rust C. 2010. If I was going there I wouldn’t start from here: a critical commentary on current assessment practice. Assess Eval Higher Educ. 36(4):479–492. doi:10.1080/02602930903512883.

- Pumilia CA, Lessans S, Harris D. 2020. An evidence-based guide for medical students: how to optimize the use of expanded-retrieval Platforms. Cureus. 12(9):e10372. doi:10.7759/cureus.10372.

- Reiter HI, Rosenfeld J, Nandagopal K, Eva KW. 2004. Do clinical clerks provide candidates with adequate formative assessment during objective structured clinical examinations? Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 9(3):189–199. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/b:ahse.0000038172.97337.d5.

- Rumack CM, Guerrasio J, Christensen A, Aagaard EM. 2017. Academic remediation. Acad Radiol. 24(6):730–733. doi:10.1016/j.acra.2016.12.022.

- Thampy H, Walsh JL, Harris BHL. 2023. Playing the game: the educational role of gamified peer-led assessment. Clin Teach. 20(4):e13594. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.13594.

- Thistlethwaite J. 2012. Interprofessional education: a review of context, learning and the research agenda. Med Educ. 46(1):58–70. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04143.x.

- Thornhill-Miller B, Camarda A, Mercier M, Burkhardt J-M, Morisseau T, Bourgeois-Bougrine S, Vinchon F, El Hayek S, Augereau-Landais M, Mourey F, et al. 2023. Creativity, critical thinking, communication, and collaboration: assessment, certification, and promotion of 21st century skills for the future of work and education. J Intell. 11(3):54. doi:10.3390/jintelligence11030054.

- Van Duzer E, McMartin F. 2000. Methods to improve the validity and sensitivity of a self/peer assessment instrument. IEEE Trans Educ. 43(2):153–158. doi:10.1109/13.848067.

- Wainer H, Feinberg R. 2015. For want of a nail: why unnecessarily long tests may be impeding the progress of western civilisation. Significance. 12(1):16–21. doi:10.1111/j.1740-9713.2015.00797.x.

- Walsh JL, Harris BHL, Denny P, Smith PE. 2018. Formative student-authored question bank: perceptions, question quality and association with summative performance. Postgrad Med J. 94(1108):97–103. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2017-135018.

- Walsh JL, Harris BHL, Smith PE. 2017. Single best answer question-writing tips for clinicians. Postgrad Med J. 93(1096):76–81. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133893.

- Walsh JL, Harris BHL, Tayyaba S, Harris D, Smith PE. 2016. Student-written single-best answer questions predict performance in finals. Clin Teach. 13(5):352–356. doi:10.1111/tct.12445.

- Wormald BW, Schoeman S, Somasunderam A, Penn M. 2009. Assessment drives learning: an unavoidable truth? Anat Sci Educ. 2(5):199–204. doi:10.1002/ase.102.

- Xavier C, Howard ML, Shah K, Guilbeau B, Richardson A. 2023. Influence of a peer-led mock osce on student performance and student and peer tutor perceptions. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 87(8):100323. doi:10.1016/j.ajpe.2023.100323.

- Yates J, James D. 2006. Predicting the ‘strugglers’: a case-control study of students atottinghamm university medical school. BMJ. 332(7548):1009–1013. doi:10.1136/bmj.38730.678310.63.