Abstract

This paper explores the practices of division in operation in primary schools in England in response to the pressures of high stakes tests at age 10/11, known as SATs. Using data from interviews with 20 primary headteachers and information from a survey of nearly 300 primary heads, we argue that the organisation of pupils in preparation for SATs involves 1) the use of grouping by ‘ability’ in sets, despite the increasing evidence of the disadvantages; 2) forms of educational triage, where borderline or ‘cusp’ children are prioritised, and more complex forms of ‘double triage’; and 3) the growth of ‘intervention culture’ where some children are withdrawn from normal lessons to resolve ‘gaps’ in their learning. In this article these practices are understood through a Foucauldian lens as micropractices of power which label and categorise pupils within an accountability system that seeks to classify pupils on a norm/Other binary.

Introduction

The accountability system in primary schools in England is extensive, with statutory assessments taking place in five of the seven year groups (age 4–11). The most significant of these are the formal tests taken at the end of the final year of primary education (Year 6) in Mathematics, Reading, and Spelling, Punctuation and Grammar (SPaG), known as SATs. The results of these tests and the linked teacher assessments in writingFootnote 1 form the basis of league tables which rank schools by their performance, in a marketized neoliberal education system (Ball Citation2017). While SATs have been in place since the 1990s, their form and content have altered with the policy decisions of successive governments, including a revised, ‘tougher’ set of tests introduced in 2016 by the Conservative government. This was part of a package of educational reforms, associated with the Secretary of State Michael Gove, which also included changes to inspection regimes, increased and accelerated Academisation,Footnote 2 the removal of standardised National Curriculum levels for assessment, and changes to how headteachers are supported. While there has been extensive research internationally on the impact of high stakes testing (see for example, Au Citation2011; Hursh Citation2013; Lewis and Hardy Citation2015; Lingard and Sellar Citation2013), there has been little exploration in England of the impact of SATs in their current form on schools, and none which focuses on the views of headteachers, whose careers depend on their SATs results. This research explored the impact of the current iteration of these tests on schools through in-depth interviews with 20 headteachers at a range of schools around England, and a survey of 288 heads conducted online. This paper focuses specifically on the findings related to schools’ policies relating to classroom practices, and particularly schools’ use of grouping by ‘ability’,Footnote 3 educational triage and interventions, which are characterised as ‘dividing practices’ or ‘practices of division’ (after Foucault Citation1967).

Through exploring these practices of division, which we take to mean systems where children are separated, either physically or nominally, based on a view of their ability or potential, the aim is to examine how the pressure from high stakes testing can translate into differential experiences for children. The findings from the headteacher survey and interviews suggest that there are three main practices arising from SATs: 1) the use of grouping by ‘ability’ in sets, despite the increasing evidence of the disadvantages; 2) forms of educational triage (Gillborn and Youdell Citation2000), where borderline or ‘cusp’ children are prioritised, including some more complex examples of what we term ‘double triage’; and 3) the growth of ‘intervention culture’ where some children are withdrawn from normal lessons to resolve ‘gaps’ in their learning. Our discussion of these findings follows an explanation of the accountability regime and SATs, our theoretical framework, and details of the research study.

SATs and the accountability regime in England

The primary education system in England is dominated by a range of statutory assessments in Reception and Years 1, 2, 4, 6 (ages 4/5, 5/6, 6/7, 8/9 and 10/11 years). These assessments, of which the Key Stage 2 SATs in Year 6 are the most significant, are used to assess the education provided by the primary school within a neoliberal marketized, accountability-driven system, as has been well-documented (Ball Citation2017; Keddie Citation2017; Simkins et al. Citation2018). The Key Stage 2 SATs have been used since the 1990s, but they have evolved with different governments’ priorities and preoccupations, such as the aim of requiring schools to teach grammar formally. The current assessments in place since 2016 include test papers in Spelling, Punctuation and Grammar (SPaG), Reading, and Mathematics (an arithmetic and reasoning paper and a further reasoning paper). These assessments take place over one week in June, known as ‘SATs week’. There are also teacher assessments in writing and science (STA 2018). Papers are marked externally and pupils are awarded scaled scores of between 80 and 120, converted from their raw marks. These scaled scores translate into three categories:

working towards age-related expectation

meeting age-related expectation (ARE)

working at greater depth (GD).

If a pupil reaches ARE or the higher level of GD, they are described as ‘reaching the expected level’. In 2019, 65% of pupils in England reached the expected level in reading, writing and maths (DfE Citation2019a)Footnote 4 – known as ‘Combined ARE’. In the same year, if we look at individual subjects, 21% of children were designated as not reaching the expected standard (working towards ARE) in Maths, 27% in Reading, 22% in Writing, and 21% in SPaG. As such this is a system which labels a significant proportion of children as ‘behind’ where they should be at age 11, while also designating schools and by implication headteachers as ‘failing’ if they do not produce appropriate results.

Since the new assessments were introduced, results overall have gradually improved as schools adapted their practice to the new papers. There remain differences in results by pupil characteristics: the expected level benchmark was reached by 60% of boys and 70% of girls in 2019; and by 47% of pupils on free school meals (FSM) compared to 68% of all other pupils (UK Government Citation2020). There are marked differences apparent in the published data by ethnic group: the highest attaining group are Chinese students with 80% reaching the expected level, while the equivalent figure for the White British majority is 65%%. When groups are split into FSM and non-FSM, it is also apparent that figures for the Black Caribbean, Mixed White/Black Caribbean, White British and White Other groups on FSM are below 50%. For these groups, the majority of pupils are labelled as not meeting ARE as they leave primary school. Of the children designated as having special educational needs (SEN) only 22% attain Combined ARE, compared to 74% of pupils without this label (DfE 2019a).

These tests matter to schools immensely as the results are a key part of the inspection process, as well as providing information for performance (league) tables. Poor or declining results are a trigger for an Ofsted inspection, leading one headteacher in the study to declare ‘I’m only as good as the last set of my results’ (HT School P). Headteachers’ jobs and salaries are dependent on these results, and there is also a risk that a poor inspection may result in academisation within a Multi-Academy Trust (MAT) (Simkins et al. Citation2018). While overall the process of academisation has been slower in the primary sector, with 67% of primaries remaining in local authority (LA) control compared to 24% of secondaries in 2019 (DfE Citation2019b), press reports suggest over 300 primaries have been removed from LA control after inadequate Ofsted judgements in the last three years (McIntyre and Weale Citation2019). SATs results are truly ‘high stakes’ for the headteachers we interviewed in this study, and this has an impact on practice.

The relationship between assessment and pedagogic practice

International research on high stakes testing has suggested a variety of impacts on all areas of schooling, from teacher professionalism and subjectivities, to pedagogy and practice (Bibby Citation2009; Booher-Jennings Citation2008; Hall et al. Citation2004; Keddie Citation2016; Reay and Wiliam Citation1999; Torrance Citation2017; Ward and Quennerstedt Citation2019). A variety of effects has been noted relating to how teachers organise and teach children in their classrooms over the last nearly three decades of national curriculum assessments in England. High stakes testing encourages a narrowing of the curriculum, with a focus on the subjects to be assessed (Boyle and Bragg Citation2006; Hall et al. Citation2004), and more rote-learning and use of practice questions or past papers (Harlen and Crick Citation2002; Reay and Wiliam Citation1999). There is more instruction, rather than problem-solving (Johnston and McClune Citation2000). Similar effects have been found in other countries and areas which use high stakes tests, such as some states of the US (Lauen and Gaddis Citation2016), and in research detailing the impact of newly introduced assessments on some schools in Sweden (Löfgren, Löfgren, and Pérez Prieto Citation2018; see also Silfver et al. Citation2020), among others.

Most relevant here, is the evidence that testing encourages grouping by ‘ability’, in various forms. Towers et al. (Citation2019) found that, in their case study primary schools, different grouping practices were deployed for year groups with tests (Year 1, 2 and 6) due to accountability pressures. Furthermore, the use of grouping in Year 6 was affected by the ‘status’ of the school; they comment that ‘In high achieving schools the pressure to achieve beyond the expected level of attainment was evident in their practices’ (2019, 32). [Author] (2018) noted that the pressures of the Phonics Screening Check, the statutory test in Year 1 (age 5/6), resulted in children being grouped at this age and younger by their level of phonics knowledge. This grouping included some examples of educational triage, where the ‘borderline’ children who were close to meeting the expected standard were the teacher’s focus. This prioritisation, first described in relation to secondary education in England (Gillborn and Youdell Citation2000), has also been found in relation to another statutory assessment, the Early Years Foundation Stage, in Reception (Roberts-Holmes Citation2015), as well as in international studies of the impact of high stakes tests (Booher-Jennings Citation2005; Lauen and Gaddis Citation2016; Neal and Schanzenbach Citation2010). In a detailed case study of the use of educational triage in preparation for mathematics SATs in one primary school, Marks (Citation2014) found that there were gains in attainment for the small group of ‘cusp’ children, but not for the children in the ‘lowest’ set. This ‘lower’ group of children were not given a regular classroom space and moved frequently, and were taught by a teacher some of the week and a Higher Level Teaching Assistant (HLTA) for the rest, suggesting their low value in a context where the priority is improving results. Similar relations between testing and practices of setting and streaming have also been found in secondary education (Francis, Taylor, and Tereshchenko Citation2019)

Internationally, high stakes tests are seen as having particularly significant effects on children from disadvantaged backgrounds and those from minority ethnic groups (Hamre, Morin, and Ydesen Citation2018; Jennings and Sohn Citation2014). Grouping practices are similarly seen as particularly detrimental to these students, as lower expectations results in mis-placement in groups and lower self-esteem (Archer et al. Citation2018; Campbell Citation2015; Francis et al. Citation2020; Hargreaves, Quick, and Buchanan Citation2019; McGillicuddy and Devine Citation2020).

McGillicuddy and Devine, in reference to primary classrooms in Ireland, describe:the fixity of failure among those pupils assigned to lower ability groups (girls, African and Traveller children) who, over the course of four years, became entrapped within a socially constructed matrix of space characterised by lower social and academic status (Citation2020, 569).

This is what Archer et al. (Citation2018) call the ‘symbolic violence’ of grouping, which disproportionately affects already marginalised groups in what Francis, Taylor, and Tereshchenko (Citation2019) term a ‘double disadvantage’. Those in lower sets, they found, were more likely to be taught by teachers without a degree in the subject, and these students’ self-confidence decreases over time (Francis, Taylor, and Tereshchenko Citation2019). This leads them to label the practice as ‘socially unjust’.

Theoretical perspectives on the organisation of pupils

Within this analysis, grouping practices – be they formal or informal – are understood through a Foucauldian lens as manifestations of disciplinary power (Foucault Citation1977), that is power that operates on the individual, through positioning, sorting, ranking and classifying, for example. This is power that is not obvious, but pervasive, which has produces individuals as particular subjects. Discipline ‘breaks down’ individuals (as well as other things) so that ‘they can be seen, on the one hand, and modified on the other’ (Foucault Citation2009, 56).

Gore’s discussion of ‘micropractices of power’ within the classroom provides a schema for thinking about the diffuse and unstable operation of disciplinary power in this context. This is done optimistically; Gore argues ‘the Foucauldian approach enables us to document that which causes us to be what we are in schools and hence, potentially, to change what we are’ (2001, 185). In the classroom, power is exercised in the form of: classification, which is the use of ‘truths’ about children to distinguish between them; distribution, which is the use of these truths to physically separate or organise people within a space; and exclusion, which is the use of truths to define the boundaries of normality and abnormality (Gor). Grouping involves classification and distribution most obviously, but also forms of exclusion, in that some children are defined by their group as unlikely to achieve a benchmark, or as in need of additional help to ‘catch up’. As I discuss further below, the use of definitions such as ‘ARE’ creates a binary of acceptable/unacceptable which further excludes some children from acceptability. This approach builds on previous use of Foucault’s work to explore how children can be labelled as unintelligible or ‘impossible’ learners (Youdell 2006) and how discipline works in education through ‘hierarchical observation’ and ‘normalising judgements’ to define children with SEN in relation to a norm (Allan Citation1996).

In this paper, we use ‘practices of division’, after Foucault’s (Citation1967) term ‘dividing practices’, but with an awareness of the more complex relation to objectification in his use of the phrase. Here, we use ‘practices of division’ to mean the spatial and nominal separation of all children as they are classified and distributed, as well as perhaps being excluded (to use Gore’s terminology) within the space of the classroom or school.

The research study

This research project explored the views of headteachers of primary schools on Key Stage 2 SATs tests through a mixed methods approach involving a nationwide survey and interviews with 20 headteachers. It was funded by the More than a Score coalition of teachers’ and parents’ groups but conducted independently (for full report see Bradbury Citation2019a).

The survey was compiled using Opinio software, and was distributed via the researchers’’ networks, social media and the National Education Union (a teachers’ union), with a specific request for headteachers to respond. It was completed by 288 respondents who were headteachers or executive headteachers in the period March-June 2019 (ending shortly after the week when SATs were completed by Year 6 pupils). The respondents were leaders at Community Primary Schools, Faith Schools, Academies and other schools, with a range of Ofsted ratings (though ‘Good’ was the most common). Respondents had been headteachers for varying lengths of time (approximately 30% each from under 5 years, 5–9 years, and 10–19 years, and 5% over 20 years). Respondents were asked a series of questions about the impact of SATs, and were also asked to identify different areas of school life that they thought were affected by SATs (such as extra-curricular clubs, the organisation of the school year and staffing). They were also asked if they strongly agreed, agreed, neither agreed or disagreed, disagreed or strongly disagreed with a number of statements, which were based on existing literature and material related to SATs. In the following findings section, written survey comments are denoted by a W.

Interviews were conducted with 20 headteachers at primary schools in various regions of England. Purposive sampling was used to ensure that the headteachers represented different types of school as well as different geographic areas. Contact was made through the existing professional networks of the research team and through survey respondents who volunteered to be interviewed. A priority of the sampling strategy was to explore regional and local variation. The inclusion of schools that are Academies, both recent and longer-standing converters, and part of both large and local MATs, was also a key aim. Headteachers in the sample varied by gender (nine female and 11 male), age and length of time as a head.

Headteachers were interviewed using standard interview schedules by a member of the research team. Interviews were recorded and transcribed professionally for analysis. Qualitative data analysis focused on the themes generated by the research questions, and then identified significant sub-themes through thematic coding. The research was conducted within the ethical guidelines provided by the British Educational Research Association.

Thematic analysis of the data was guided by the theoretical tools offered by policy sociology and policy enactment (Stephen Ball, Maguire, and Braun Citation2012; Braun, Maguire, and Ball Citation2010), Gore’s work influenced by Foucault on micropractices of power (2001), and the existing literature on grouping (Marks Citation2014; Bradbury Citation2018) – as discussed above. Several conclusions were drawn on the topic of classroom practices, and we focus here on the impact on how children are organised physically within school spaces and across the school day. Although there was wide variation in practice, often related to context, some distinct themes emerged which we outline here.

Other key findings relating to the impact of SATs on headteachers, pupils and staff; the reduced curriculum; and the impact on the wider school were detailed in a report published in 2019 (Bradbury Citation2019a).

Findings

Findings 1: the use of grouping by ‘ability’

First, the research data suggested that, in some schools, SATs tests justified ‘setting’, which is a form of grouping by ‘ability’ where whole classes are rearranged for one subject on the basis of attainment. Under a system of ‘setting’, children move from their normal class to different rooms and teachers for either Maths or English, or both, based on each child’s attainment or assessed potential.

We do set in Year 5 and 6, just for maths. (HT School N)

We do it [set] in Maths so that we can move those children on and it can be at a greater depth. Then, we build up the other children so that they can go at a slower pace, but not [in] English. (HT School M)

… a lot of schools would [claim not to set]. So, they would say, ‘Oh, no, we’re mixed ability at this school and all our learners learn together and everyone’s happy.’ But then they get to Year 6 and they stream them. (HT School I)

Data from the survey suggested that setting was by no means universal, but was used by a proportion of schools as a direct response to SATs. The survey responses to the statements ‘SATs mean we have to group pupils by ability in English’ and ‘SATs mean we have to group pupils by ability in Maths’, indicated variations in perspectives (n = 183 and n = 188 respectively) are detailed in .

Table 1. Survey responses to the statement ‘SATs mean we have to group pupils by ability in English/Maths’.

Notably, the proportions agreeing and disagreeing overall for English, (35% agreed while 44% disagreed) are reversed for Maths with 47% agreeing and 35% disagreeing. As suggested by previous research (Marks Citation2014), the use of grouping remains more acceptable in Maths than in English subjects, though the variety of different lessons that now come under the term English may confuse matters here.

These practices of setting operate despite the increasing awareness of the disadvantages of setting, as presented in recent research projects (Francis, Taylor, and Tereshchenko Citation2019; George Citation2019; Hargreaves, Quick, and Buchanan Citation2019), and despite teachers’ reluctance to use setting, as found in studies on grouping in Key Stage 1 and early years (Bradbury Citation2018). Several headteachers expressed their concerns about setting in interviews, relating it to their moral stance on education:on a sort of moral level, I’m opposed to setting, although that’s exactly what I have in Year 6, but not just two or three sets, on a daily basis there might be six sets. I’m not a fan of it, but it [SATs] definitely encourages setting and I know that lots and lots of schools set from Year 3, 4 onwards. (HT School J)

… if it’s that strict and that regimented and there is not a lot of flexibility and not a lot of movement, pupils get into a psyche of failure because they’ve always been in the bottom set. […] You’re just written off. That isn’t, in my view, right or fair. (HT School B)in order to stand a chance of children being able to cope under pressure we do set them from Feb onwards particularly for maths. I worry about the effect this has on children’s maths mindsets and it goes against everything I believe in. (W)

As discussed, there is extensive evidence of the problems associated with grouping by ability or attainment (Campbell Citation2015; Francis, Taylor, and Tereshchenko Citation2019; Hargreaves, Quick, and Buchanan Citation2019; McGillicuddy and Devine Citation2020), which are reflected in these headteachers’ concerns about children being ‘written off’ and the impact on their ‘mindsets’. Several headteachers referred to the research in this area; for example the head at School C commented ‘research shows that that’s not always effective’.

For those using setting, there were particular concerns raised about the practice in relation to English:

For Writing, we’ve always said that if you split for Writing, those lower achieving children don’t hear that rich vocabulary that they then could use in their writing. So, you’re really putting a ceiling on their writing by not surrounding them with all that higher level thinking. The same with Reading, I suppose, if they don’t ever get to hear that higher level thinking then they’re never going to use it. (HT School M)

These concerns led to some attempts to alleviate the effects, such as having ‘mixed’ sets to prevent children having lower self-esteem:in Year 6 we have more sets but again, we try and have a bit of a mix in those sets. We don’t just have a bottom set because if you’re in the bottom set then in terms of mental wellbeing, you constantly think you’re bottom. (HT School B)

As suggested in other research (Bradbury Citation2019b; Marks Citation2013), teachers did not blindly follow grouping practices without an understanding of the research and the negative effects. However, there were pressures on these teachers will led to them using grouping by ‘ability’ despite their concerns. It should be noted that in a small number of cases, there had been a rejection of setting or streaming and the headteacher was critical about past practice; in others, there was an outright rejection of any form of grouping, suggesting a wide range of practice across schools.

Setting was one form of grouping by ability which resulted from SATs: there were also examples of streaming, where children are put permanently in classes based on ability; setting within year groups throughout the school for Maths; and use of in-class ability groups (based on tables). For example, one headteacher explained that ‘after Easter, then we have some SPaG groups, so they’ll be set according to ability’ (HT School G).

All of these practices of division were driven by an assumed need to push each child as far as possible in order to maximise SATs results. The need to ensure each child was ‘moving on’ resulted in a desire to tailor teaching to different levels by simply dividing children into different rooms, despite the clear concern about the impact on their self-esteem and attitudes to learning.

Findings 2: the use of educational triage

As discussed, ‘educational triage’ describes a system children are organised according to their potential to gain a benchmark grade, into a ‘safe’ group likely to attain the benchmark; a ‘worth working on’ target group who might reach the benchmark if additional resources are deployed; and a ‘hopeless’ group who are seen as unlikely to attain the benchmark. Triage is a practice seen in a range of age groups in England (Bradbury Citation2018; Gillborn and Youdell Citation2000; Marks Citation2014; Roberts-Holmes and Bradbury Citation2016) and internationally, where there is pressure from high stakes tests (Booher-Jennings Citation2005; Lauen and Gaddis Citation2016).

In the primary schools in our study, ‘booster’ groups aimed at children nearly reaching ARE were commonplace. These children were described as ‘borderline’ or on the ‘cusp’ of the all-important benchmark. For example:

It’s very much driven by the data and resources are very much targeted at children who are borderline; in other words, children who might get it or we might get them across the line with some intensive interventions and so, those children are very much targeted (HT School W)

It’s the cusp, to get them to age related expectation (HT School A)

Most of them [booster groups] would be for the children who were – there would be a level of identifying gaps. Most of them would be, I suppose, we would call them the cusp children – the fragile children. (HT School E)

Intervention groups are focussed on the children that are borderline to pass the tests at the expense of other children. (W)

These children are defined and labelled based on their potential to achieve ARE and therefore improve the school’s standing. This targeting of cusp children only makes sense if other children are not cusp children, either because they are seen as very likely to achieve ARE or because they are seen as unlikely to do so. This triaging of resources to the most valuable children in terms of data is a logical response to the pressures imposed by SATs, but remains a potentially damaging system which allow some children to be given less attention.

While the use of triage is well-established, the findings here suggest a new variant derived from the increasing complexity of school league tables. Since 2016 the primary tables have also included data on the proportion of children reaching ‘Greater Depth’ (GD), the higher benchmark. Our data suggest that, as a result, schools have begun to use booster groups focused on children on the cusp of GD to improve their standing on this indicator. For example:

[Booster group] is very much targeted at cusp children, be they cusp of getting expected to greater depth or getting just almost getting to expected, and we just need that extra very small group (HT School S)

[Group is taught by] a qualified teacher and she takes out some cusp children. So, she’s got a group of cusp and a group of children that need to be great at it. (HT School M)

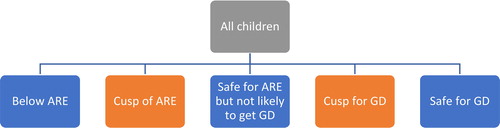

This suggests that triage strategies may operate in more complex forms, in response to changes in the reporting of attainment. Here, the usual three-way division is replaced with a more complex split – what we might call ‘double triage’ (see ).

In this system, the children in both cusp groups are the target for interventions and also for booster sessions, such as those held before school and during holidays. There are two borderlines of success and failure here – reaching ARE and reaching GD – because these two pieces of information are included in performance tables. Thus there are also two groups of cusp children, and some children who would previously have been seen as ‘safe’ for ARE are now targeted because they are ‘cusp’ for GD. Another group of children are positioned as important, simply because of the change in reporting of results. This is an example of how assessment produces increasingly elaborate systems of calculation and calibration; practices of division as micropractices of power are bound up in external definitions and categorisations, subject to change at any point.

This increasing strategic complexity was reflected in headteachers’ comments on the staffing required for these groups (and also the related interventions, discussed below). For example, one headteacher commented ‘We put the children into small groups which means taking support staff and leadership away from other parts of the school’ (W). Headteachers reported taking groups themselves, leaving them with less time for leadership responsibilities, and a general repurposing of all staff to allow for several small groups to be taught. The resulting problems with staffing were explained by the head at School E, where they had decided against using booster groups:the booster used to be huge because it wasn’t just like within the Year 6 team […], because frankly, the whole bloody school was teaching the kids – assistant heads, [deputy], me. I mean, practically everyone apart from the cleaning lady, to be quite honest, would be sitting with small groups of kids in various corners just trying to get them prepared for the SATs. (HT School E)

This explanation highlights the whole school impact of SATs, and the at times desperate measures taken to ‘boost’ children to higher grades.

Focusing interventions on ‘cusp’ children and organising groups around this criterion are common strategies aimed specifically at improving SATs results. In other research this prioritisation strategy has been associated with the perpetuation of disparities in attainment, through the selection of who is deemed to be ‘borderline’ (Gillborn and Youdell Citation2000). It is not clear if this is the case here where children are identified using data, but given the existing research on the connections between grouping selection and marginalised groups (Archer et al. Citation2018; Campbell Citation2015), these findings raise further questions about how grouping for SATs might exacerbate inequalities.

Findings 3: the use of interventions

A third, related finding, and perhaps the most significant from the data from headteachers, revealed the growth of what we term ‘intervention culture’. This is the prevalence of systems where children are removed from normal lessons, assemblies or playtimes, usually in small groups, on the basis of needing to rectify ‘gaps’ in their learning or being ‘behind’ in one area. These interventions, sometimes based on bought-in schemes, are often taught by a member of staff other than the class teacher. Following previous work (Bradbury Citation2018), we consider interventions as a form of grouping. Interventions may be one-off events, or may happen regularly for several weeks or months, and thus they are a far more flexible form of grouping than setting, for example. Interventions are distinct from triage in that they do not involve all the children in a system of categorisation, but instead relate to a small number of specific children, and usually a specific subject area, skill, or topic. The systematic use of interventions represents as significant a practice as setting or in-class grouping, with similar potential impact on children, and indeed staff.

Data from headteachers suggested that there was an increased use of interventions in preparation for SATs, and a shift in focus from helping children ‘catch up’ present in earlier year groups to an attempt to resolve ‘gaps’ in learning:

We hold many intervention groups and booster groups start now with Year 5 after SATs and through to Year 6 SATs. (W)

After Christmas we start to try to plug the gaps in time for SATs (HT School A)

So they tend to be all in the class together, in the mornings for maths, English and reading lessons but then in the afternoons, they miss a lot of the non-curriculum for intervention work. (HT School O)

… the teachers can keep some children in assembly to do same day intervention. (HT School L)

In terms of SATs interventions, we had a group of girls that were struggling around confidence, so twice a week, for an hour a week, in the lesson before lunchtime, I did a top-up group for those. (HT School R)

Here the basis for selecting children for intervention is directly related to SATs: this is a practice of division whereby children are removed from their classroom or miss out on other school events because they are deemed to have ‘gaps’ or, in one case above, struggle with confidence (notably a gendered phenomenon in the quote above). The discourse around intervention suggests these children have deficiencies that need to be ‘fixed’ through targeted action. At times, this was a day-by-day strategy: children who were seen as not having understood in the morning were subject to interventions in the afternoons or in assembly time. Children are being ‘fixed’ or ‘topped up’ in the short-term, as well in the longer term through repeated intervention sessions. The spatial aspect of this grouping system, which involves physical removal from the majority of the class, is significant, given ‘how sociospatial practices in the primary school shape children’s learning experiences’, generating awareness of hierarchy and feelings of shame (McGillicuddy and Devine Citation2020, 556).

Previous research has shown how interventions can be used as a way of demonstrating that schools are fully aware of pupils’ attainment data (Bradbury and Roberts-Holmes Citation2017); a teacher in this study explained that ‘any intervention’ would be noted down in pupil progress meetings so that the school could demonstrate to Ofsted that they were responding to the data. She explained: ‘we have to have something on this bit of paper so that when it doesn’t, we can show that we at least did something’. This is not how interventions are used in relation to SATs, however, as the motivation is not the performative recording of responses to data for Ofsted, but the production of better test scores. These different types of intervention culture are an area worthy of further research, as they indicate the competing priorities and pressures teachers experience and how they result in different practices.

There were also examples in our dataset of headteachers who saw interventions as having a partly pastoral role: this head explained these ‘support groups’:

It’s supporting those kids educationally, emotionally, being an integral part of their pastoral care of those kids as well as it is maths. Making sure that they like maths and feel comfortable. So, I mean, they are targeted for assessments, of course. I mean, we’d be stupid not to: that’s just good teaching. But I wouldn’t… Yes, just more holistic than just that. (HT School H)

For this school leader, the additional group work has a dual function of making children ‘feel comfortable’, but is also ‘targeted for assessments’. This latter element is taken for granted as a purpose – ‘we’d be stupid not to’ – but the headteacher also wishes to emphasise the more holistic side of the group work. This suggests that SATs not only encourage grouping for academic purposes, but grouping is also seen as enabling children to cope with the emotional impact of the assessments.

Interventions in preparation for SATs are a practice of division that: classifies children as in need of additional help; distributes them physically into another room or corridor; and excludes them from assembly time or other lessons, to focus on their ‘gaps’ in English and Maths, or to emotionally prepare them. The selection of children is based on the need to improve results, and to resolve perceived deficiencies in children’s knowledge or understanding. As such, though they differ from traditional forms of grouping such as setting and in-class grouping, interventions remain part of a suite of grouping practices with similar effects, and represent a similar expression of disciplinary power in the classroom. This consideration of intervention culture is a necessary focus on the ‘mundane and meticulous’ forms of power, ‘in small points of control and minute specifications’ (Stephen Ball Citation2013, 31), as well as the more obvious forms of grouping.

Discussion

We have analysed these systems of pupil organisation as ‘practices of division’ (after Foucault 1965, Citation1977) which classify, distribute and exclude children (Gor), on the basis of their value in relation to SATs tests. This is a system which regularly sorts children on the basis of their usefulness within the testing regime, or their perceived ‘gaps’ in learning. We argue that these forms of disciplinary power are encouraged by the disciplinary function of SATs themselves, which place pressure on headteachers to prioritise results over the broader purposes of education. The inclusion of SATs data in league tables fosters competition between schools and creates a constant sense of threat for these headteachers, who fear one ‘bad’ set of results which will trigger an Ofsted inspection (Bradbury Citation2019a). Furthermore, it is important to remember that the tests themselves are seen as detrimental to children, and especially those children with lower past attainment and those who are otherwise marginalised. Headteachers commented:

So there is a big effect negatively on some children. I fear that that’s often the prior low attainers or the more vulnerable children. (HT School C)

pupils from deprived backgrounds e.g. pupil premium: lots of social issues. We’ve had children take SATs who have been made homeless the night before or who haven’t slept or are using foodbanks (W)

The disproportionate impact on these children of SATs in general has to be taken into account in discussion of the consequences of the tests for grouping; it may be that grouping is part of a range of impacts of SATs which collectively disadvantage some children.

The SATs assessments are in themselves, ultimately, a practice of division, designating children as at Age Related Expectation (ARE) or not. This binary between success and failure, passing or failing, is a brutal division of children at age 11. There are of course further levels of division too, such as those that are given ARE but do not reach GD, who may also feel like they have failed. This division of children was a source of concern for some headteachers:

I think to brand children as failures, in Year 6, I think it goes against everything that we come into teaching for, really. (HT School O)

They made things even harder, which means… The first year, what was it? 54% of children reached ARE combined? Now, psychologically, 46% of children then felt like failures. […] Did it make it better? What, telling everyone they’re failing? (HT School H)

It is emotional when you have to give the children their results. That is a very emotional day for a headteacher I think because you know that you are handing over complete disappointment to some children and families. (HT School A)

For these headteachers, the language of not reaching ARE is equivalent to designating children as ‘failures’, with emotional consequences. As seen above, the fact that these judgments are given to parents and children results in ‘complete disappointment’ for some. Furthermore, SATs results are passed on to secondary schools, where they form the basis of an expected ‘flightpath’ through to GCSE exams, based on the calculations used in the Progress 8 measure of secondary school success.Footnote 5 But, as indicated in the discussion of ‘double triage’ above, the division created by SATs is in fact not a binary, but a tripartite split into not ARE/ARE/GD. This divides children into failing/acceptable/successful (and in turn, their schools into similar categories). This is a biopolitical function of the assessments, which drives the disciplinary operation of practices of division in the classroom. Without SATs, the divisions would not disappear entirely, but they might be replaced by more nuanced ways of understanding a child’s attainment, and the practices which are necessitated by the tests would disappear. There can be no triage or ‘cusp’ children if there is no benchmark to judge them by.

Conclusion

The findings from this study presented here reinforce existing literature on the relationship between high stakes testing and pedagogic practices, and specifically those relating to grouping. This research demonstrates how this connection operates in relation to the statutory tests at the end of primary schools, SATs, in their revised form in the late 2010s. The pressure to improve SATs results means that schools group or set children in English and particularly in Maths, with all the attendant impacts on self-esteem and confidence (Archer et al. Citation2018; Campbell Citation2015; Francis et al. Citation2020; Hargreaves, Quick, and Buchanan Citation2019; McGillicuddy and Devine Citation2020). They also use systems of triage, which prioritise children who might achieve the benchmark of ARE given extra help, and in some cases, a more complex version of ‘double triage’ which focuses on children on both the cusp of ARE and the cusp of GD. This development emphasises how increasing complexity in systems of measurement and reporting have consequences in classrooms. There is also strong evidence in our study of what we have called ‘intervention culture’; the practice of using small group sessions which take place in school hours to ‘plug gaps’ in learning, or boost the attainment of particular children. Intervention culture involves the physical exclusion of children from assembly or other non-Maths or Literacy lessons, and as such demonstrates all three of Gore’s micropractices of power – classification, distribution and exclusion – which we have used to examine these practices of division. Again, we argue that interventions need to be seen as part of systems of grouping by ‘ability’, in preparation for SATs or otherwise, as they remain a key form of dividing children on the basis of perceived or expected attainment.

This study was conducted in what was the last ‘normal’ year of SATs testing for a while: the tests were abandoned in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the results for 2021 will be seen as affected by school closures. The accountability system has however been an important part of discussion about how education should change, post-pandemic. The More than a Score coalition of educational and parent groups, for example, organised a campaign titled #DropSats2021, and the controversy over the downgrading of A Level results in August 2020 provided further reason to question the accountability system (Benn Citation2020; Dunford Citation2020). Early evidence from teachers suggests that there is a strong desire for change following the crisis, including the removal of testing (Moss et al. Citation2020). What the evidence presented here demonstrates is that part of the conversation about the impact of high stakes testing should be focused on how it fosters practices of division – grouping by ‘ability’, interventions and triage – and the consequences for primary school children.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Teacher assessments in writing use a framework provided by the Standards and Testing Authority (STA), and there is no formal test of writing.

2 Academisation refers to the transfer of control of schools from the local authority to central government. Schools that become Academies are no longer part of local authorities but accountable instead to central government. Many Academies are part of Multi-Academy Trusts (MATs) which are confederations of schools.

3 ‘Ability’ is used in quotation marks in recognition of the contested nature of the term; the idea of ‘ability’ used in forming groups regards ability as measurable and/or innate.

4 The SATs were not conducted in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

5 The Progress 8 measure uses pupils’ Key Stage 2 SATs data in comparison with GCSE results in eight subjects at age 16 to measure the ‘value added’ by the school based on prior attainment (DfE Citation2016). The eight subjects included are English and Maths (which are double weighted), combined science, history or geography and a language, plus the three highest scoring additional subjects for each student. The use of progress measures is seen as problematic as it suggests predictions of attainment and therefore caps on expectations (Taylor-Mullings Citation2018), and there is some evidence that it advantages schools with intakes with higher prior attainment (Leckie and Goldstein Citation2019).

References

- Allan, J. 1996. “Foucault and Special Educational Needs: A ‘Box of Tools’ for Analysing Children’s Experiences of Mainstreaming.” Disability & Society 11 (2): 219–234. doi:10.1080/09687599650023245.

- Archer, L. , B. Francis, S. Miller, B. Taylor, A. Tereshchenko, A. Mazenod, D. Pepper, et al. 2018. “The Symbolic Violence of Setting: A Bourdieusian Analysis of Mixed Methods Data on Secondary Students’ Views about Setting.” British Educational Research Journal 44 (1): 119–140. doi:10.1002/berj.3321.

- Au, W. 2011. “Teaching under the New Taylorism: high‐Stakes Testing and the Standardization of the 21st Century Curriculum.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 43 (1): 25–45. doi:10.1080/00220272.2010.521261.

- Ball, S. 2013. Foucault, Power and Education . Abingdon: Routledge.

- Ball, S. , M. Maguire, and A. Braun. 2012. How Schools Do Policy: policy Enactments in Secondary Schools . Abingdon: Routledge.

- Ball, S. J. 2017. The Education Debate. 3rd ed. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Benn, M. 2020. “England’s exam results fiasco has exposed its flawed education system.” Accessed 14 August 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/aug/11/england-results-exams-fiasco-ofqual-inequality

- Bibby, T. 2009. “How Do Children Understand Themselves as Learners? Towards a Redefinition of Pedagogy.” Pedagogy, Culture and Society 17 (1): 41–55. doi:10.1080/14681360902742852.

- Booher-Jennings, J. 2005. “Below the Bubble: ‘Educational Triage’ and the Texas Accountability System.” American Educational Research Journal 42 (2): 231–268. doi:10.3102/00028312042002231.

- Booher-Jennings, J. 2008. “Learning to Label: Socialisation, Gender, and the Hidden Curriculum of High Stakes Testing.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 29 (2): 149–160.

- Boyle, B. , and J. Bragg. 2006. “A Curriculum without Foundation.” British Educational Research Journal 32 (4): 569–582. doi:10.1080/01411920600775225.

- Bradbury, A. 2018. “The Impact of the Phonics Screening Check on Grouping by Ability: A ‘Necessary Evil’ amid the Policy Storm.” British Educational Research Journal 44 (4): 539–556. doi:10.1002/berj.3449.

- Bradbury, A. 2019a. “Pressure, Anxiety and Collateral Damage: The Headteachers’ Verdict on SATs.” Retrieved 7 June 2020. https://www.morethanascore.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/SATs-research.pdf.

- Bradbury, A. 2019b. “Rethinking ‘Fixed Ability Thinking’ and Grouping Practices: Questions, Disruptions and Barriers to Change in Primary and Early Years Education.” FORUM 61 (1): 41–52. doi:10.15730/forum.2019.61.1.41.

- Bradbury, A. , and G. Roberts-Holmes. 2017. Grouping in Early Years and Key Stage 1: A ‘Necessary Evil’? London: National Education Union.

- Braun, A. , M. Maguire, and S. Ball. 2010. “Policy Enactments in the UK Secondary School: Examining Policy, Practice and School Positioning.” Journal of Education Policy 25 (4): 547–560. doi:10.1080/02680931003698544.

- Campbell, T. 2015. “Stereotyped at Seven? Biases in Teacher Judgement of Pupils’ Ability and Attainment.” Journal of Social Policy 44 (3): 517–547. doi:10.1017/S0047279415000227.

- DfE . 2016. “Progress 8: How Progress 8 and Attainment 8 measures are calculated.” Accessed 6 July 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/561021/Progress_8_and_Attainment_8_how_measures_are_calculated.pdf

- DfE . 2019a. “National Curriculum Assessments at Key Stage 2 in England, 2019.” Accessed 15 December 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/851798/KS2_Revised_publication_text_2019_v3.pdf

- DfE . 2019b. “Open academies, free schools, studio schools and UTCs.” Accessed 23 July 2019. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/open-academies-and-academy-projects-in-development

- Dunford, J. 2020. “It’s exam-only assessment that has led us to this mess.” Accessed 14 August 2020. https://www.tes.com/news/its-exam-only-assessment-has-led-us-mess

- Foucault, M. 1967. Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason . London: Tavistock Publications.

- Foucault, M. 1977. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison . London: Allen Lane.

- Foucault, M. 2009. Security, Territory, Population: lectures at the Collège de France, 1977–1978 . New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Francis, B. , N. Craig, J. Hodgen, B. Taylor, A. Tereshchenko, P. Connolly, and L. Archer. 2020. “The Impact of Tracking by Attainment on Pupil Self-Confidence over Time: Demonstrating the Accumulative Impact of Self-Fulfilling Prophecy.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 41 (5): 626–642.

- Francis, B. , B. Taylor, and A. Tereshchenko. 2019. Reassessing ‘Ability’ Grouping: Improving Practice for Equity and Attainment . Abingdon: Routledge.

- George, M. 2019. “Setting would not exist in an ideal world, says leading academic.” Accessed 8 July 2019. https://www.tes.com/news/setting-would-not-exist-ideal-world-says-leading-academic

- Gillborn, D. , and D. Youdell. 2000. Rationing Education: policy, Practice, Reform and Equity . Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Gore, J. M. 2001. Disciplining bodies: On the continuity of power relations in pedagogy. In Paechter, C. (Ed.). (2001). Learning, space and identity London: Paul Chapman167–181.

- Hall, K. , J. Collins, S. Benjamin, M. Nind, and K. Sheehy. 2004. “SATurated Models of Pupildom: Assessment and Inclusion/Exclusion.” British Educational Research Journal 30 (6): 801–817. doi:10.1080/0141192042000279512.

- Hamre, B. , A. Morin, and C. Ydesen. 2018. Testing and Inclusive Schooling: International Challenges and Opportunities . Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hargreaves, E. , L. Quick, and D. Buchanan. 2019. “I Got Rejected’: Investigating the Status of ‘Low-Attaining’ Children in Primary-Schooling.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society 29 1: 79–97.

- Harlen, W. , and R. D. Crick. 2002. A Systematic Review of the Impact of Summative Assessment and Tests on Students’ Motivation for Learning . London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education.

- Hursh, D. 2013. “Raising the Stakes: High-Stakes Testing and the Attack on Public Education in New York.” Journal of Education Policy 28 (5): 574–588. doi:10.1080/02680939.2012.758829.

- Jennings, J. , and H. Sohn. 2014. “Measure for Measure: How Proficiency-Based Accountability Systems Affect Inequality in Academic Achievement.” Sociology of Education 87 (2): 125–141. doi:10.1177/0038040714525787.

- Johnston, J. , and W. McClune. 2000. Pupil motivation and attitudes. Research paper for the effects of the selective system of secondary education in Northern Ireland report. Belfast: DENI.

- Keddie, A. 2016. “Children of the Market: Performativity, Neoliberal Responsibilisation and the Construction of Student Identities.” Oxford Review of Education 42 (1): 108–122. doi:10.1080/03054985.2016.1142865.

- Keddie, A. 2017. “Primary School Leadership in England: Performativity and Matters of Professionalism.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 38 (8): 1245–1257. doi:10.1080/01425692.2016.1273758.

- Lauen, D. L. , and S. M. Gaddis. 2016. “Accountability Pressure, Academic Standards, and Educational Triage.” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 38 (1): 127–147. doi:10.3102/0162373715598577.

- Leckie, G. , and H. Goldstein. 2019. “The Importance of Adjusting for Pupil Background in School Value‐Added Models: A Study of Progress 8 and School Accountability in England.” British Educational Research Journal 45 (3): 518–537. doi:10.1002/berj.3511.

- Lewis, S. , and I. Hardy. 2015. “Funding, Reputation and Targets: The Discursive Logics of High-Stakes Testing.” Cambridge Journal of Education 45 (2): 245–264. doi:10.1080/0305764X.2014.936826.

- Lingard, B. , and S. Sellar. 2013. “Catalyst Data’: Perverse Systemic Effects of Audit and Accountability in Australian Schooling.” Journal of Education Policy 28 (5): 634–656. doi:10.1080/02680939.2012.758815.

- Löfgren, H. , R. Löfgren, and H. Pérez Prieto. 2018. “Pupils’ Enactments of a Policy for Equivalence: Stories about Different Conditions When Preparing for National Tests.” European Educational Research Journal 17 (5): 676–695. doi:10.1177/1474904118757238.

- Marks, R. 2013. “The Blue Table Means You Don’t Have a Clue: The Persistence of Fixed-Ability Thinking and Practices in Primary Mathematics in English Schools.” Forum 55 (1): 31–44.

- Marks, R. 2014. “Educational Triage and Ability-Grouping in Primary Mathematics: A Case-Study of the Impacts on Low-Attaining Pupils.” Research in Mathematics Education 16 (1): 38–53. doi:10.1080/14794802.2013.874095.

- McGillicuddy, D. , and D. Devine. 2020. “You Feel Ashamed That You Are Not in the Higher Group’—Children’s Psychosocial Response to Ability Grouping in Primary School.” British Educational Research Journal 46 (3): 553–573. doi:10.1002/berj.3595.

- McIntyre, N. , and S. Weale. 2019. “More than 300 English primary schools forced to become academies.” Accessed 23 July 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2019/jul/11/more-than-300-english-primary-schools-forced-to-become-academies

- Moss, G. , R. Allen, A. Bradbury, S. Duncan, S. Harmey, and R. Levy. 2020. Primary Teachers’ Experience of the COVID-19 Lockdown – Eight Key Messages for Policymakers Going Forward . London: UCL Institute of Education.

- Neal, D. , and D. W. Schanzenbach. 2010. “Left behind by Design: Proficiency Counts and Test-Based Accountability.” Review of Economics and Statistics 92 (2): 263–283. doi:10.1162/rest.2010.12318.

- Reay, D. , and D. Wiliam. 1999. “I’ll Be a Nothing’: Structure, Agency and the Construction of Identity through Assessment.” British Educational Research Journal 25 (3): 343–354. doi:10.1080/0141192990250305.

- Roberts-Holmes, G. 2015. “The ‘Datafication’ of Early Years Pedagogy: ‘If the Teaching Is Good, the Data Should Be Good and If There’s Bad Teaching, There is Bad Data.” Journal of Education Policy 30 (3): 302–315. doi:10.1080/02680939.2014.924561.

- Roberts-Holmes, G. , and A. Bradbury. 2016. “The Datafication of Early Years Education and Its Impact upon Pedagogy.” Improving Schools 19 (2): 119–128. doi:10.1177/1365480216651519.

- Silfver, E. , M. Jacobsson, L. Arnell, H. Bertilsdotter-Rosqvist, M. Härgestam, M. Sjöberg, U. Widding, et al. 2020. “Classroom Bodies: Affect, Body Language, and Discourse When Schoolchildren Encounter National Tests in Mathematics.” Gender and Education 32 (5): 682–696. doi:10.1080/09540253.2018.1473557.

- Simkins, T. , J. Coldron, M. Crawford, and B. Maxwell. 2018. “Emerging schooling landscapes in England: How primary system leaders are responding to new school groupings.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 47 (3), 331–348.

- Taylor-Mullings, N. 2018. “Race, Education and the Status Quo.” Unpublished PhD thesis, University College London.

- Torrance, H. 2017. “Blaming the Victim: Assessment, Examinations, and the Responsibilisation of Students and Teachers in Neo-Liberal Governance.” Discourse: studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 38 (1): 83–96.

- Towers, E. , B. Taylor, A. Tereshchenko, and A. Mazenod. 2019. “The Reality is Complex’: Teachers’ and School Leaders’ Accounts and Justifications of Grouping Practices in the English Key Stage 2 Classroom.” Education 48 (1): 22–36.

- UK Government . 2020. “Ethnicity facts and figures: Reading, writing and maths results for 10 to 11 year olds.” Accessed 5 July 2020. https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/education-skills-and-training/7-to-11-years-old/reading-writing-and-maths-attainments-for-children-aged-7-to-11-key-stage-2/latest

- Ward, G. , and M. Quennerstedt. 2019. “Curiosity Killed by SATs: An Investigation of Mathematics Lessons within an English Primary School.” Education 47 (3): 3–13, 261–276.