?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Although calls for responding to migration-related diversity in education are not novel, few studies have examined linguistic and affective outcomes of diversity-sensitive approaches for vocabulary teaching. This article reports on an intervention study in which beginner English-foreign-language learners (N = 51, Mage = 8.67 years) worked on one textbook unit (five 45-min lessons). Teachers supplemented the unit with translingual scaffolds and encouraged students to draw on and use their linguistic resources (plurilingual group), or stimulated appreciation of plurilingualism and positive language attitudes (motivation group). We assessed language gains through pre-, post-, and follow-up tests, and measured affect after each lesson. Both intervention groups outperformed the control group, which worked only with the textbooks, regarding productive vocabulary learning. Translingual scaffolding was beneficial for sustaining vocabulary gains. The data further indicate that motivational activities stimulate positive affect, but only the plurilingual group showed lower negative affect than the control group. Overall, the data suggest that intervention activities can augment productive vocabulary and support student well-being. We argue that future studies should pay more attention to affective outcomes when exploring ways of addressing migration-related diversity in the classroom.

Introduction

Finding ways of adequately responding to migration-related diversity in the classroom has become a major educational quest across Europe, in which foreign language (FL) education plays a pivotal role. The Companion to the Common European Framework for Languages (Council of Europe Citation2018) underlines the long-term objective to foster appreciative attitudes and form ‘open-minded plurilingual citizens’ (26) specifically stipulating that students should be encouraged ‘to use all their linguistic resources’ in the language classroom and to see and explore ‘similarities and regularities as well as differences between languages and culture’ (27).

However, most European schools’ language policies are assimilationist in nature, and students with migration backgrounds are usually expected to suppress their linguistic identity and knowledge (e.g. Pulinx, van Avermaet, and Agirdag Citation2017). Even in FL education, students’ linguistic resources are rarely activated (Hall and Cook Citation2012; for the situation in German EFL classes, see Göbel and Helmke Citation2010; Göbel and Vieluf Citation2018), which perpetuates already existing hierarchical perceptions of languages (see Busse Citation2017; Liddicoat and Curnow Citation2014). The underlying assumption is that students’ knowledge of family languagesFootnote1 does not advance learning, and that engaging in the school languages(s) is more important.

Research indicates that such assimilative educational practices and their underlying monolingual ideologies and deficit perspectives may hinder multilingual children from reaching their academic potential (e.g. Cummins Citation2000). Allowing children to draw on and use their linguistic resources can be beneficial for language learning, but the bulk of research comes from classrooms in bilingual or diglossic societies (for review, see Cenoz Citation2013). Further studies on how to address migration-related diversity in the FL classroom are therefore essential for advancing research and providing practical guidance. The overall aim of our project is thus to find feasible and salubrious ways of capitalising on linguistic diversity. In this particular study, we examine the effect of two diversity-sensitive teaching approaches, where teachers either encouraged usage of linguistic resources drawing on translanguaging pedagogy or stimulated positive attitudes towards language learning.

Background literature

Why do we need to address migration-related diversity better?

Across Europe, there has been an increase in migratory movements with net migration particularly high in Western Europe (Statista Research Department Citation2020). Currently, almost 40% of German primary school students have a migration background (Statistisches Bundesamt Citation2019). Although many studies situated in diglossic societies or bilingual educational programmes have reported advantages for third language acquisition in bilingual students (e.g. Brophy Citation2001; Cenoz Citation2013; Sanz Citation2000), advantages may not apply to students with migration backgrounds due to differences in the learning circumstances and language proficiency (see also Edele, Kempert, and Schotte Citation2018; Hirosh and Degani Citation2018). Firstly, students with migration backgrounds are often socio-economically disadvantaged and may attend schools where the concentration of disadvantaged students is high contributing to underperformance (e.g. OECD Citation2015). Secondly, students’ linguistic knowledge in dual-immersion classrooms with explicit instruction differs from that of students engaged with migrant languages only at home, limiting proficiency to oral skills. In fact, migrant languages are often less socially accepted and their use is typically restricted compared to minority languages in diglossic societies.

In addition, the degree of overlap between languages plays a role in learning (e.g. Hirosh and Degani Citation2018). Migrant languages (e.g. Arabic, Turkish) are often rather different from FLs taught at school. In a longitudinal study involving German primary school students (9-10-year-olds), Hopp et al. (Citation2019) found students with Turkish migration backgrounds scored lower in English than the monolingual group. However, when controlling for socioeconomic factors, a multilingual advantage emerged for vocabulary and grammar. Vocabulary in the family language was predictive for early learning, but the positive effect of bilingualism declined from grade 3–4, when proficiency in German became more predictive.

Research in German secondary schools tends to report advantages for bi- and multilingual students (Hesse, Göbel, and Hartig Citation2008; Maluch et al. Citation2015) when controlling for socioeconomic status and other relevant factors such as cognitive ability. Maluch et al. (Citation2015), however, found that the strongest predictor for FL learning was proficiency in German, not the migrant language. Edele, Kempert, and Schotte (Citation2018) similarly found that competence in German explained a considerable part of variances in English achievement both for mono- and bilinguals, and that bilingualism itself did not exert an additional effect. Actually, bilinguals with low proficiency levels in both languages or Turkish-dominant students attained lower proficiency than monolinguals. Results thus tie in with numerous other studies that have revealed the importance of the instruction language for academic development (e.g. OECD Citation2015). Additionally, the similarity between German and English can play a role, but possibly also teaching practices that neglect students’ family languages (see Hopp et al. Citation2020).

In summary, studies indicate a multilingual advantage for FL learning, but students with migration backgrounds may not necessarily perform better in the FL classroom. Much depends on students’ socioeconomic background and their proficiency in the language of regular school instruction. Therefore, more effort has to be made to support these learners. The data further indicate that classroom practices can play a role in whether the multilingual advantage can actually come into force.

Translanguaging as a pedagogical approach and translingual scaffolding for early vocabulary teaching

Language classes are usually conducted in the target language to maximise input and time on task and prevent interference of students’ family language(s). However, the idea of teaching exclusively through the target language and thus separating students’ family language(s) from the target language has been called into question (e.g. Cenoz and Gorter Citation2019). Research on bi- and multilinguals suggests that there is an interrelationship between different languages (Cook Citation1992; Grosjean Citation1989), and that outside the classroom, bi- or multilingual children often engage in complex and fluid language practices called translanguaging (e.g. García and Lin Citation2016). Therefore, separating languages in the classroom creates an artificial situation that differs from students’ day-to-day interactions.

Based on these insights, multilingualism researchers have advocated for viewing students as emergent multilingual speakers who use their entire linguistic repertoire for cognition and social engagement and should, therefore, be allowed to do so in the classroom (Cenoz and Gorter Citation2019; Cummins Citation2017). The term translanguaging has come to refer to a pedagogical approach that acknowledges this reality and encourages building connections between languages (e.g. García and Lin Citation2016) thus providing translingual scaffolds for language learning. The approach suggests that teachers prepare instructional settings where students are encouraged to draw on and use all their linguistic resources for implicit or explicit language comparisons (cross-linguistic comparisons) or multilingual discursive tasks (see also Cenoz Citation2019) which may also aid future language learning (see Candelier Citation2017).

Recent studies exploring the usefulness of plurilingual approaches in German EFL grammar teaching indicate that cross-linguistic comparisons can facilitate grammar development in instances where the majority language differs from the target language (Hopp and Thoma Citation2021). However, the data also show the difficulties posed by cross-linguistic grammar comparisons for primary school children with very low levels of proficiency. It may therefore be advisable to introduce the plurilingual approach gradually starting with vocabulary teaching.

It has long been known that vocabulary size and depth of lexical meaning knowledge are predictors of bilingual migrant children’s academic success (e.g. Verhallen and Schoonen Citation1993). Studies on conceptual transfer further suggest that words are linked in the mental lexicon and knowledge of lexical items in one language can influence how children process and produce new words in other languages (Jarvis and Pavlenko Citation2008). Encouraging cross-linguistic comparisons and stimulating positive lexical transfer may therefore help bilingual students expand their vocabulary in a third language (for evidence with graduating students see Agustín-Llach Citation2019). However, studies on translanguaging are often observational (e.g. Durán and Palmer Citation2014), and there are surprisingly few intervention studies systematically measuring the impact of translingual scaffolding as a meaning-making resource for early vocabulary teaching.

Lyster, Quiroga, and Ballinger (Citation2013) explored the effect of biliteracy instruction on morphological awareness in English and French at a French immersion programme in Canada (7-8-year-olds). When assessing language awareness, the experimental group outperformed the control group on derivation and decomposition in French vocabulary. Even when controlling for language dominance in the English measure, English-dominant students in the experimental group performed better than the control group. Translingual scaffolding also proved beneficial in a study by Arteagoitia and Howard (Citation2015) where both English and Spanish were used to teach vocabulary to Spanish- and English-speaking US students (11–14-year-olds). Cognates from the two languages were used to enhance vocabulary and reading comprehension in English. Learning Spanish cognates benefitted English vocabulary and English reading comprehension. A similar study by Leonet, Cenoz, and Gorter (Citation2020) involving Basque-Spanish students (10-11-year-olds) learning English showed that students who studied derivation and compounding with examples from all three languages made more progress on morphological awareness than a control group who received instruction solely in English. However, there were only two family languages involved, so these findings may not apply to classrooms where a plethora of languages are present.

In particular, it is unclear to what extent translingual activities are feasible and effective in language classrooms with high migration-related diversity, as children are neither homogeneous in language background nor language ability. Using children’s whole linguistic repertoires as a didactic asset or ‘translingual scaffold’ in the classroom may thus become time-intensive and could deter progress of the entire learning group which typically consists of both students with and without migration backgrounds. Additionally, teachers’ knowledge of students’ languages is usually limited, which poses obstacles to implementation. More research is thus needed to explore the feasibility of translingual scaffolding in language classrooms where teachers, with little or no knowledge of migrant languages, have to accommodate the needs of diverse students under considerable curricular time constraints (see also Bailey and Marsden Citation2017).

A further limitation of the studies discussed is that affective outcomes are not measured. Engaging with various languages is cognitively demanding and could cause stress in young children, who already suffer from various academic stressors in primary school (Backhaus, Petermann, and Hampel Citation2010). Translingual scaffolding may also trigger unease in students with migration backgrounds in classrooms dominated by a ‘monolingual habitus’ (Gogolin Citation2013). Well-being (or lack thereof) can, in turn, affect general student development and academic outcomes (Taylor et al. Citation2017), but also specifically achievements, acculturation processes, and the general social and psychological development of children with migration backgrounds (Göbel and Frankemölle Citation2020; OECD Citation2015). In particular, first generation students may have lower school satisfaction and social belonging (e.g. Henschel et al. Citation2019) which contribute to performance gaps. Gaps are, in fact, smaller in countries where immigrant students report happiness at school and a high sense of belonging (OECD Citation2015). Both designing diversity-sensitive teaching activities conducive to (all) students’ well-being, which also stimulate appreciative attitudes, and measuring affective outcomes are therefore of paramount importance.

More recently, Busse et al. (Citation2020) reported on linguistic and affective outcomes of an intervention study comprising five 45-minute lessons for third graders (8-10-year-olds) at a German primary school with a high percentage of students with migration backgrounds. Students in the experimental group were encouraged to draw on and use their linguistic resources and engaged in cross-linguistic comparisons. They additionally participated in two motivational activities that stimulated appreciation of plurilingualism and positive language attitudes. Students in the experimental group outperformed the control group in terms of productive and receptive vocabulary learning, and these learning gains were sustained over the retention interval. Students also showed higher positive affect than the control group, particularly during the motivational activities. While results were thus encouraging, it remained unclear to what extent better learning outcomes could be attributed to the activation of linguistic resources rather than to the activation of positive affect. The present study builds on these results and explores the effect of translingual scaffolding in more depth.

Aims and hypotheses of the present study

The particular objective of this study was to explore both linguistic and affective outcomes of diversity-sensitive teaching approaches (with and without translingual scaffolding) and compare them to regular teaching with target language use only. In our study, all students engaged in a textbook learning unit called ‘Body’. Students were encouraged to draw on and use their linguistic resources (plurilingual group) or engaged in activities aimed at stimulating appreciation of plurilingualism and positive attitudes towards language learning (motivation group). The two intervention groups were compared to a control group that only worked with the textbook.

Based on the studies discussed above, we defined two overarching research questions (RQ) and tested the following hypotheses (H).

RQ1: What is the intervention's effect on learning outcomes (productive and receptive vocabulary gains in English) in the target language?

Based on studies discussed previously, one may assume that students remember new words better when elements in the target language are related back to their linguistic repertoires (plurilingual group). Similarly, heightened motivation and well-being may lead to higher task engagement (motivation group). Following this, one could hypothesise that students in the intervention groups outperform students in the control group on post-tests (H1a). However, activities in the intervention groups take 15 min. per lesson, which subtracts from textbook time. Students in the intervention groups may thus perform less well on post- tests than the control group which has more timeFootnote2 to reinforce and consolidate the target language (H1b). In either case, we expect students in the control group to outperform students in the intervention groups on productive vocabulary tests when correct spelling is required (H1c), as intervention groups spend less time reading and writing target words in the textbook. Given the lack of prior research, no hypothesis was formed regarding differences between the plurilingual and motivation groups.

RQ2: To what extent does the intervention influence positive and negative affect?

Materials and methods

Participants

The original sample consisted of six intact groups of primary EFL learners in third grade. Due to the coronavirus outbreak, the sample was reduced to three intact groups with a total of 51 beginner learners at a German primary school (25 girls, 25 boys, one child did not indicate gender) whose ages ranged from 8 to 10 years (M = 8.67; SD = .59).

We implemented a randomised assignation of three intact groups to three conditions: the plurilingual group (n = 18), the motivational group (n = 17), or the control group with regular teaching (n = 16). The three groups had a similar gender distribution (plurilingual: 8 girls, 9 boys, 1 missing; motivation: 9 girls, 8 boys; control: 8 girls, 8 boys). In each group, there were several learners with migration backgrounds (plurilingual: 8; motivation and control: 12 each), who also reported regularly using their family languages at home.Footnote3

A power analysis using G*Power (Faul et al. Citation2007) showed that our sample size was sufficient to ascertain small to medium effects (f = 0.25) in a mixed between-within-subjects design with three groups with an alpha = .05 and power (1-β) = .80, correlations between repeated measures = .50, and three measurement time points.

Design and intervention

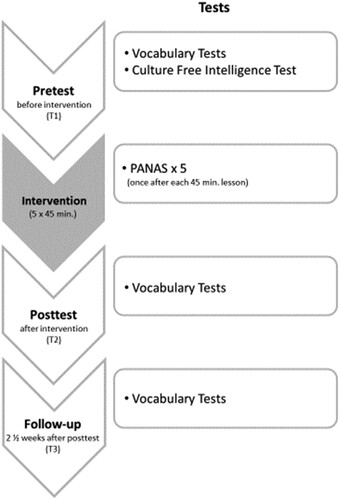

We chose a quasi-experimental intervention study with a pre-, post-, and follow-up design to address the research questions. To ensure ecological validity, the intervention took place in the schools during regular school lessons.

The participating students’ parents received information about the project and gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. In addition, we informed all participants orally about the study and explained the procedures.

Before the intervention (T1), research assistants helped the students complete a short socio-demographic questionnaire to gain information about age, sex, migration background, and languages spoken at home. In addition, we administered the Culture Fair Intelligence Test (Cattell Citation1961; see section Independent Variables) and intervention-based vocabulary tests that assessed productive and receptive vocabulary knowledge in the target language English (see section Dependent Variables).Footnote4

The intervention itself comprised five lessons (45 min each) which were implemented over the course of three weeks (1-2 lessons per week). After three lessons, schools closed due to the coronavirus pandemic; students had a two month break before continuing the unit. Two pre-service teachers implemented the learning unit (one teaching, one assisting) according to a detailed script based on the textbooks in all lessons in all three groups, i.e. all groups were always taught by the same teachers.Footnote5 To increase treatment fidelity, an experienced English-language teacher observed all lessons and ensured teaching script adherence.

Following each lesson, we administered the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson, Clark, and Tellegen Citation1988). After the intervention (T2), we again administered the vocabulary tests. Two and a half weeks later (T3), we administered the language tests a third time as a follow-up (see ).

Materials

Activities conducted by all three groups

The intervention was embedded in a textbook unit ‘Body’ (Becker, Gerngross, and Puchta Citation2013a, 2013b), and all groups worked on the textbook’s unit exercises (Playway 3: Pupil’s Book, p. 34; Playway 3: Activity Book, pp. 28, 31). Activity book exercises (31, nr. 7) included a listening comprehension activity where a monster was described with target words. They listened to this description twice (Lesson 4), wrote a description of a monster based on example sentences from the activity book and read it out loud to the other students (Lesson 5), and participated in three warm-up activities.Footnote6 Due to school closings and the break between Lesson 3 and Lesson 4, Lesson 4 began with a vocabulary review in all groups. The intervention groups engaged in one additional 15-min. timed task per lesson (five tasks/ 75 min. in total). A tabular overview of intervention content is provided in Appendix 1.

Lesson 1 (introductory activity for both intervention groups)

The teacher conducted a treasure chest activity (for details see Busse et al. Citation2020) where students were asked why languages could be considered treasures. Students in the plurilingual group were encouraged to reflect in any language;Footnote7 students in the motivation group were allowed to speak in German in addition to English. Afterwards, the teacher explained to the plurilingual group that they would now use these linguistic resources in their teaching.Footnote8

Lessons 2 (plurilingual group)

The teacher encouraged the students to share body part translations into other languages after introducing target words in English. During these translingual activities, the teacher prompted students to compare pronunciation and phonological similarities between English words and family languages including German (cross-linguistic comparisons).

Lessons 2 (motivation group)

Students were introduced to the language portrait method based on Krumm and Jenkins (Citation2001). The teachers presented two fictional children and read out how they allocated the languages they spoke to their different body parts (e.g. my heart and my belly are Italian). Teachers then read out the characters’ reasonings for allocation (e.g. because I love … food; my mother is from …). Afterward, the teachers gave students a worksheet called ‘my language self’ and prompted the class to associate any language they had some knowledge of with their body parts via colouring a blank body outline. Finally, the children presented their language portraits.

Lesson 3 (plurilingual group)

Students played a game where one student first named body parts in English and then translated them into any other language while throwing a soft ball to the next student (plurilingual body part ball toss game).

Lesson 3 (motivation group)

Teachers presented a video of a 7-year-old plurilingual role model naming body words in three languages (including English). The teachers first asked students to identify the languages.. On a second viewing, the teachers asked which body parts the young girl could name in which language. The teachers showed enthusiasm about becoming plurilingual and stressed that learning different languages is valuable for all students.

Lesson 4 (plurilingual group)

Students in the plurilingual group were additionally encouraged to recall words in family languages. Students then played a memory game (plurilingual body part memory game). Matching pairs consisted of a word card in English (e.g. tooth) and one picture card. Whenever a picture card was turned over, students had to say the word out loud in English and in any other language they were familiar with, including German.

Lesson 4 (motivation group)

The teachers conducted another language portrait activity. Teachers asked students to associate languages they still want to learn with the different body parts which students could see and read on the board. Students then presented their plurilingual future selves to the class. Only English was used to describe body parts.

Lesson 5 (concluding activity for both intervention groups)

The students engaged in an affective-experiential activity, a dream journey(for details see Busse et al. Citation2020). Students in the motivation group heard all the target words in English during the activity; students in the plurilingual group additionally heard some target words in the family languages including German and were encouraged to silently think of translations of the English words into their family languages.

In summary, out of five activities, only four activities (Lessons 2-5) focused on body words. Exercises involved speaking and listening to body words. Reading was only required in Lesson 4, and no writing exercises were conducted. Intervention content differed most in Lessons 2-4.

The two intervention groups did not work on the body unit between post- and follow-up tests, as not to influence results between T2 and T3. In contrast, the control group continued work on the body unit after T2 according to school curriculum.

Control group activities

Students in the control group were allowed to spend more time on the individual text book exercises. That is, during the fifteen min. per lesson where the intervention groups engaged mostly with speaking and listening exercises, the control group was able to spend more time on reading and writing exercises in the textbooks. In addition, the control group had time to play the game Simon Says with body-related phrases introduced in the book (Becker, Gerngross, and Puchta Citation2013b, 35, No. 4) at the end of two lessons. The game uses gestures, which have been found to facilitate vocabulary learning in younger learners (Huang, Kim, and Christianson Citation2019).

Treatment fidelity

We ensured treatment fidelity by providing the whole research team with a detailed teaching guide for each lesson which specified textbook activities to be completed and how they were to be taught. The two pre-service teachers taught the five lessons in all three groups, and the experienced teacher observed all lessons to ensure that all students conducted the same activities with the exception of intervention content. Observation notes show that teachers adhered to the teaching guide and implemented all activities as prescribed.

Dependent variables

Language Tests (administered at t1, t2 and t3)

We used four written tests from a previous study (Busse et al. Citation2020; see also Appendix 3) to assess students’ productive (Tests 1 & 2) and receptive vocabulary (Tests 3 & 4).

Test 1: Body part vocabulary recall based on a visual stimuli (20 body parts; maximum possible score = 20).

In Test 2: Body part translation German to English (20 body parts; maximum possible score = 20).

Test 3: Word comprehension; matching body part on a picture to English words (20 body parts; maximum possible score = 20).

Test 4: Comprehension of description; matching eight written descriptions of a monster (e.g. ‘the monster has got three teeth’) to corresponding pictures based on the monster exercises completed in all groups (eight descriptions; maximum possible score = 8).

In total, a maximum score of 68 points could be achieved. Because correct spelling is not yet a requirement for primary school students, two different scores were calculated in Tests 1 and 2: The first score was for correct spelling, where a point was only awarded if the word was spelled accurately, and the second score where a point was also awarded for phonetically acceptable spelling according to German phonetics (e.g. ‘ni’ for ‘knee’ or ‘ei’ for eye).

PANAS (administered after each lesson)

We measured positive and negative affective outcomes of each lesson by the PANAS (Watson, Clark, and Tellegen Citation1988), which Krohne et al. (Citation1996) adapted for German speakers and Roden et al. (Citation2016) adapted for primary school children. The rating scale for the intensity of each emotional experience ranged from 1 (not at all/very little) to 3 (a lot). Three images of different sized balloons accompanied the scale values to support students’ understanding of them (see Appendix 2). The coefficient Cronbach’s alpha for positive affect was .89 and .85 for negative affect.

Independent Variables

Students completed a short questionnaire asking about socio-demographic details (age, sex, migration background, and languages spoken at home and during their free-time activities). In addition, they completed the German adaptation of Cattell’s Culture Free Intelligence Test (Cattell Citation1961) by Weiß (Citation2006) to measure fluid intelligence (four subtests: series, classifications, matrices, and typologies).

Results

One-way ANOVA comparing the three groups at T1 revealed no differences between groups regarding either cognitive abilities, F(2,47) = 1.57, p = .220, p = . 220, = .06, or language test results, F(2,48) = 0.20, p = .818,

< .01. Thus, groups were considered comparable.

As the experimental design was a 3 × 3 mixed model, with Group (plurilingual; motivation; control) as the between-subject factor and Time (pre-test(T1). post-test(T2), and follow-up(T3)) as the within-subject factor, we conducted two-way mixed (between-within-subjects) ANOVAs to explore the effect of the intervention by using SPSS Version 26. We tested the preconditions for conducting ANOVAs (normality, Box’s M test of equality of covariance matrices, Mauchly’s test of sphericity), and our data did not meet them in all instances, which meant that we reported the relevant statistical adjustments in these cases. In addition to the repeated measures, we conducted a one-way ANOVA to explore the overall effect of the interventions on positive and negative affect (aggregated scores from 5 lessons).

We used an online calculator for effect sizes for paired contrasts (Lenhard and Lenhard Citation2016). For interpreting effect sizes for paired contrasts, we adopted the field-specific benchmarks proposed by Plonsky and Oswald (Citation2014) for within-group contrasts, with 0.60 ≤ d < 1.00 suggesting a small effect, 1.00 ≤ d < 1.40 a medium effect, and d ≥ 1.40 a large effect. For interpreting η²part in ANOVA, we draw on Ellis (Citation2010) cutoff-points of small (.01≤ <.06), medium (.06 ≤

<.14), and large (

≥.14).

RQ1: What is the effect of the intervention on learning outcomes (productive and receptive vocabulary gains in English) in the target language?

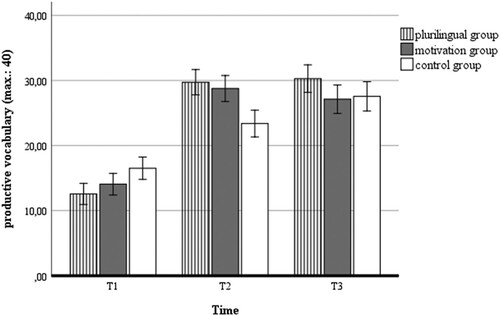

Figure 2. Productive vocabulary at Times 1, 2, and 3 (aggregated mean scores and standard errors from Productive Vocabulary Test 1 and Test 2)

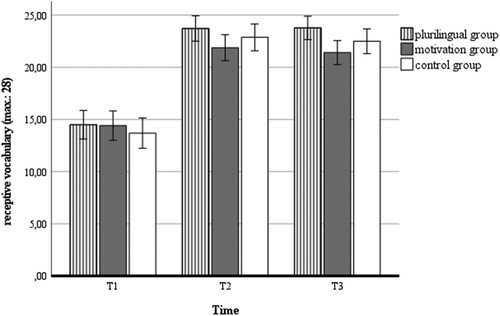

Figure 3. Receptive vocabulary at Times 1, 2, and 3 (aggregated mean scores and standard errors from Receptive Vocabulary Test 3 and Test 4).

Table 1. Performance productive vocabulary tests (max. 40): Means (standard deviations) for three groups at T1, T2, and T3.

Table 2. Performance receptive vocabulary tests (max. 28): Means (standard deviations) for both groups at T1, T2, and T3.

Productive vocabulary

A mixed ANOVA with scores aggregated from the two productive vocabulary tests (with scores given for phonetically correct spelling) across the three times with the Huynh-Feldt correction for violation of the assumption of sphericity revealed a significant large main effect for time, F(1.67,79.97) = 186.19, p < .001, = .76, no effect for group, F(2,48) = 0.23, p = .797,

= .01, but a large interaction effect, F(3.33, 79.97) = 8.32, p < .001,

= .26.

Subsequent pairwise comparisons of means for within subject effects with adjusted alpha level (p = .05/2 = .025) revealed a large effect size for learning progress from T1 to T2 in the plurilingual group, t(17) = −12.38, p < .001, d = 2.16, 95% CI [1.54, 2.78] and the motivation group, t(16) = −12.38, p < .001, d = 1.83, 95% CI [1.34, 2.32]. In the control group, we observed only a small effect size, t(15) = −3.31, p = .005, d = 0.86, 95% CI [0.25, 1.48].

Learning gains were sustained from T2 to T3 in the plurilingual group, t(17) = -.727, p = .451, d = - 0.05, 95% CI [−0.19, 0.09]; the slight decrease in scores between T2 and T3 in the motivation group was also not significant, t(16) = 1.62, p = .124, d = 0.17, 95% CI [−0.04, 0.38]. The increase in the control group was significant but with a small effect size, t(15) = −3.74, p = .002, d = −0.51, 95% CI [−0.80, −0.22].

H1a, students in the intervention groups would outperform students in the control group, was therefore accepted for productive vocabulary. Learning gains in the intervention groups were also sustained. Although intervention groups did not receive any further English lessons between T2 and T3 and the control group received continued education on the body unit, the productive vocabulary scores in the control group did not surpass those of the plurilingual group at T3.

Receptive vocabulary

In contrast to productive vocabulary, the data suggested that all three groups made similar receptive vocabulary gains (see ). A mixed ANOVA, with scores aggregated from the two receptive vocabulary tests across the three test times and with the Huynh-Feldt correction for violation of the assumption of sphericity, revealed a significant large main effect for time, F(1.81,86.99) = 138.30, p < .001, = .74, but neither an effect for group, F(2,48) = .43, p = .650,

= .02, nor for interaction, F(3.63,86.99) = 0.82, p = .508,

= .03.

Subsequent pairwise comparisons of means for within subject effects with adjusted alpha level (p = .05/2 = .025) revealed a large effect size for learning progress from T1 to T2 in the plurilingual group, t(17) = −7.79, p < .001, d = −1.38, 95% CI [−1.86, −0.89]. In the motivation group, we observed a medium effect size, t(16) = −6.78, p < .001, d = −1.25, 95% CI [−1.73, −0.77]. In the control group, we also observed a large effect, t(15) = −8.79, p < .001, d = −2.54, CI [−3.70,−1.38].

Receptive vocabulary scores were sustained and remained almost the same between T2 and T3 in the plurilingual group, t(17) = 0.06, p = .96, d = −0.01, 95% CI [−0.38; 0.36], the motivation group, t(16) = 0.75, p = .46, d = 0.08, 95% CI [−0.13, 0.29], and the control group, t(15) = 0.60, p = .56, d = 0.09, 95% CI [−0.20, 0.38].

H1a and H1b, students in the intervention group would either perform better (1a) or less well (1b) than students in the control, were rejected for receptive vocabulary. There was large learning progress in the plurilingual and the control group and medium learning progress in the motivation group. Learning gains were sustained in all three groups.

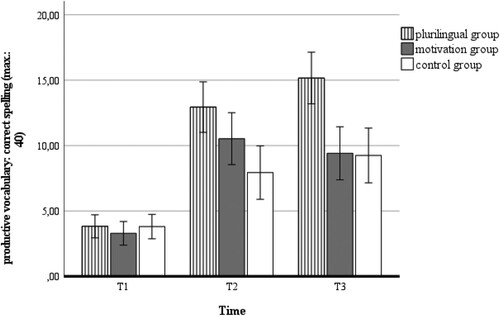

Productive vocabulary – correct spelling

In addition, we explored whether performance for productive vocabulary differed when counting only correctly spelled words (see Dependent Variables section). As we had expected, scores were lower in all groups when we counted correct spelling (see ).

Table 3. Performance productive vocabulary tests with correct spelling (max. 40): Means (standard deviations) for both groups at T1, T2, and T3.

The results further show that students in the intervention groups outperformed the students in the control group. The plurilingual group showed the largest learning progress, which was augmented over the retention interval, while there was a decrease in the motivation group (see ).

Figure 4. Productive vocabulary at Times 1, 2, and 3 (aggregated mean scores and standard errors from Productive Vocabulary Test 1 and Test 2, correct spelling required).

A mixed ANOVA, with scores aggregated from the two productive vocabulary tests, across the three test times and with the Huynh-Feldt correction for violation of the assumption of sphericity revealed a medium main effect for time, F(1.63, 78.01) = 3.80, p < .011, = .14, no effect for group, F(2,48) = 1.59, p = .214,

= .06, but a medium interaction effect, F(3.25, 78.01) = 3.80, p = .011,

= .14.

Subsequent pairwise comparisons of means for within subject effects with adjusted alpha level (p = .05/2 = .025) showed a small effect size for learning progress from T1 to T2 in the plurilingual group, t(17) = −5.92, p < .001, d = −0.96, 95% CI [−1.34, −0.58], the motivation group, t(16) = −3.40, p < .004, d = −0.78, 95% CI [−1.19, −0.37], and the control group, t(15) = 4.94, p < .001, d = −0.78, 95% CI [−1.29, −0.27].

The increase in scores in the plurilingual group between T2 and T3 was not significant given the adjusted alpha level, t(17) = −2.24, p = .039, d = −0.21, 95% CI [−0.39, −0.03]; the slight decrease in the motivation group was also not significant, t(16) = 1.62, p = .125, d = 0.13, 95% CI [−0.03, 0.29]; as was the slight increase in the control group, t(15) = −1.45, p = .166, d = −0.22, 95% CI [−0.52, 0.09].

H1c, students in the intervention groups would perform less well than students in the control group on post-intervention vocabulary tests when correct spelling was required (since the control group spent more time with textbook and thus with reading and writing new words), was therefore not supported.

RQ2: To what extent does the intervention influence positive and negative affect?

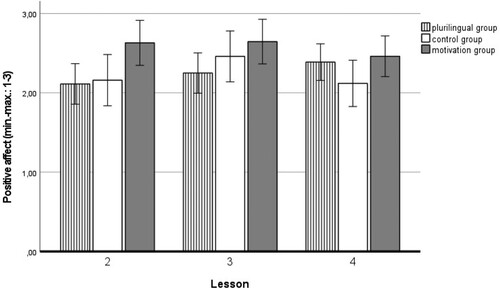

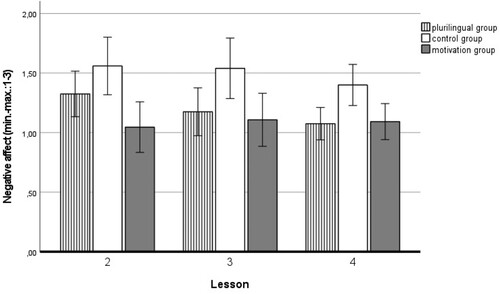

After each of the five lessons, we measured positive and negative affect via the PANAS. All three groups showed high positive affect, in particular the motivation group. Negative affect was lower in the intervention groups than in the control group. provides the scores for the PANAS.

Table 4. Positive and negative affect in the three groups (min. 1/ max.3): Means (standard deviations) from five lessons for the three groups.

One way ANOVA with aggregated scores from all five lessons revealed no significant difference among the groups for positive affect, F(2,48) = 2.35, p = .106, = .09, but there was a significant difference in negative affect, F(2,48) = 3.67, p < .033,

= .13, with a small effect size. Post-hoc tests showed that only the difference between the plurilingual group and the control group was significant, p = .034, i.e. only the plurilingual group showed significantly lower negative affect than the control group.

As intervention content differed most in Lessons 2 - 4 (see also Appendix 1), we additionally compared affect across these three lessons (see for positive affect and for negative affect). The data suggest that positive affect in Lesson 2 and 3 was highest in the motivation group. In Lesson 4, positive affect was higher in both intervention groups than in the control group. A mixed ANOVA revealed a significant main effect for lesson, F(2, 35) = 4.25, p = .022, = .20, with a large effect size. The group effect just failed significance, F(2, 36) = 2.59, p = .089,

= .13, but there was a significant interaction effect with a medium effect size, F(4,70) = 3.02, p = .023,

= .15. Post-hoc tests revealed that the motivation group showed significantly enhanced affect compared to the plurilingual group, p = .047, but the difference between the motivational group and the control group just failed significance, p = .073.

Figure 5. Positive affect during the intervention: Mean scores and standard errors for all groups after Lesson 2, 3 and 4.

Figure 6. Negative affect during the intervention: Mean scores and standard errors for all groups after Lesson 2, 3, and 4.

Regarding negative affect, a mixed ANOVA revealed no significant main effect for lesson, F(2, 35) = 1.77, p = .185, = .09, but the group effect was significant, F(2, 36) = 6.68, p = .003,

= .27, with a large effect size. No significant interaction effect, F(4,72) = 1.33, p = .268,

= .07, was observed. Post-hoc tests revealed that only the plurilingual group showed significantly lower negative affect compared to the control group (p = .025).

H2, students in the motivation group would report more positive affect and less negative affect during the intervention than students in the control and the plurilingual group, was therefore rejected. The motivation group showed higher positive affect than the plurilingual group in Lesson 2 and 3, but only the plurilingual group showed overall significantly less negative affect than the control group.

Discussion

The study aimed at stimulating word acquisition in diversity-sensitive ways. Three groups of primary school learners worked on a textbook unit for five lessons. Plurilingual group students could draw on and use their linguistic resources (including the majority language German) and engage in additional cross-linguistic comparisons. In the motivation group, teachers stimulated appreciation of plurilingualism and positive attitudes towards language learning. The control group focused on the textbook.

Regarding RQ1, our data suggest that the diversity-sensitive approaches were beneficial for augmenting vocabulary. Despite having 15 fewer minutes per lesson on textbook tasks, students in the intervention groups (particularly the plurilingual group), showed higher productive vocabulary scores post intervention than the control group. The control group continued the unit between post-and follow-up tests while the intervention groups received no English lessons during that time; nevertheless, increased vocabulary scores in the control group did not surpass plurilingual group scores in the follow-up tests. Interestingly, when exploring productive vocabulary alongside correct spelling, the intervention groups still showed greater gains than the control group despite having less time writing the new words. The plurilingual group outperformed the control group with notable sustainability, thus activating students’ linguistic resources and stimulating lexical transfer may indeed help students remember words (see also Agustín-Llach Citation2019; Busse et al. Citation2020; Lin Citation2016).

Regarding receptive vocabulary, both the control and the plurilingual group showed great progress, while the motivation group showed medium progress. Progress was sustained in all three groups. In a previous study, Busse et al. (Citation2020) found that the intervention group’s advantage was more pronounced for productive than for receptive vocabulary. While further research should explore whether longer instructional treatments lead to different results, it seems that activating linguistic resources helps augment productive vocabulary in particular.

Regarding RQ2, results showed that students enjoyed lessons as positive affect was high and negative affect was low in all groups. A comparison of individual lessons revealed that students in the motivation group felt higher positive affect towards the beginning of the intervention than students in the plurilingual group. The teachers also observed that students in the plurilingual group felt shy at first to share linguistic resources and needed time and encouragement to get used to translingual scaffolding. Interestingly, however, only the plurilingual group showed significantly lower negative affect than the control group. Therefore, although translingual scaffolding is cognitively demanding and may at first be perceived as unusual, it does not necessarily trigger negative emotions.

Our results are novel and have relevant teaching implications. Firstly, there are few intervention studies which have explored the effect of translingual scaffolding in linguistically diverse classrooms, and it is known that the use of linguistic resources in the classroom is not usually encouraged (e.g. Bailey and Marsden Citation2017; Göbel and Vieluf Citation2018; Hall and Cook Citation2012). In general, many teachers feel ill-prepared to teach in linguistically diverse classes (OECD Citation2015), and they have little guidance about incoporating students’ linguistic resources (see also Bailey and Marsden Citation2017). As opposed to bilingual settings, they have little to no knowledge of students’ languages, and may additionally worry about curricula-imposed time-constraints. Our findings help dispel these worries, at least for teaching new vocabulary in beginners’ classes. The activities we used are easy to implement and do not require teachers to have expanded linguistic repertoires. Additionally, translingual scaffolding activities give students with migration backgrounds an opportunity to deepen their lexical knowledge of the regular instruction language (in our case German), which seems crucial for achievement in the long run (e.g. Edele, Kempert, and Schotte Citation2018).

Secondly, our study is one of the few interventions to measure affective outcomes. Our data are in line with results from a previous study (Busse et al. Citation2020) which suggest that affect plays an important role in early language learning. This ties in with recent calls to look more at emotions in second language research and points to the relevance of emotional engagement for language learning in general (Swain Citation2013) and classroom participation in particular (Philp and Duchesne Citation2016). We propose that interventions need to explore affective alongside linguistic outcomes, and that studies which investigate the usefulness of plurilingual approaches to addressmigration-related diversity (e.g. Hopp and Thoma Citation2021) should in particular not fail to include affective measures. Children with migration backgrounds, especially recently migrated children, often show lower levels of school satisfaction, school belonging, and general well-being which are relevant for (academic, psychological, and social) development (see Göbel and Frankemölle Citation2020; Henschel et al. Citation2019; OECD Citation2015). It can therefore be expected that increasing positive affect can particularly benefit these students. Future studies should continue to explore whether plurilingual approaches increase positive affect of migrant children without adding to existing stress in primary school and whether activities are accepted by the class overall.

It has been proposed that translanguaging has the potential to challenge existing hierarchical perceptions of languages and may empower learners (see also Li Wei Citation2018). Given internalised hierarchies and biases by children (and parents) shaped by the still existing ‘monolingual habitus’ of schools, we would argue that translanguaging in the classroom be gradually introduced and supplemented by activities which specifically stimulate appreciative attitudes. Students with migration backgrounds will otherwise not be open to sharing their linguistic resources with the class which teachers will certainly have to respect (see also Hopp et al. Citation2020), but should foremost strive to create a diversity-sensitive classroom atmosphere.

Although results are encouraging, there are limitations which have to be discussed. Firstly, although quasi-experimental studies have high ecological validity, students are usually nested within school classes which diminishes internal validity. We responded to this limitation by collecting relevant learning prerequisites (prior language knowledge, cognitive abilities), implementing pretest, posttest, and follow-up tests, and following a meticulous standardised procedure. Our particular procedure included two trained graduate students (instead of students’ own teachers) for all three groups (one teaching, one assisting), random assignation of classes to conditions, a standardised teaching script that followed the regular textbooks, observation of classes by the regular teacher to avoid any deviations from the teaching script – confirming that lessons only varied regarding intervention content (15 min. per lesson), and measurement of affective outcomes at the end of each lesson.

Secondly, although the motivation and the plurilingual groups received different intervention content, there was a certain degree of overlap as the plurilingual approach had to be introduced via an activity transmitting appreciation of linguistic diversity. Furthermore, drawing on linguistic diversity may also indicate that students’ linguistic resources are valuable which can influence student motivation.

Thirdly, there was a break between Lesson 3 and Lesson 4 due to school closings during the coronavirus pandemic. However, comparability was still given, as all groups had the same break.

Finally, as the study was conducted with beginner learners, language progress was defined in terms of vocabulary gains and focused on concrete nouns. Future research will have to explore the effect of translingual scaffolding for more complex areas of language acquisition and also investigate possible differences between student groups. We ran additional analyses to compare performance and affective states of students with and without migration background in the intervention groups, and observed no differences. However, studies with larger samples are needed for further exploration.

Conclusion

Our data suggest that our diversity-sensitive approaches are promising. Intervention activities did not decelerate word acquisition and in fact proved useful for learning target words. Translingual scaffolding should be combined with activities to stimulate appreciation of plurilingualism and positive attitudes towards language learning. Overall, the study indicates that teachers may find cognitive and affective benefits in straying from the textbook and dedicating time to productively addressing migration-related diversity.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (800.6 KB)Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers and in particular to our research assistant, Tanne Stephens.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Family languages can be any language spoken in the household (including migrant and minority languages)

2 See the time-on-task hypothesis (Carroll Citation1963).

3 Some of these children were born in another country and had only recently migrated to Germany (plurilingual: 2 (Iraq, Syria); motivation: 5 (Poland, Bulgaria, Romania, Syria); and control: 2 (Syria)). However, only three children (one in each group) indicated that they mostly used a language other than German in their spare time. As these children were evenly distributed across the groups, the class composition can be considered roughly comparable given these characteristics.

4 Data collection at T1 took place on two different days. First, the students completed the Culture Fair Intelligence Test; two days later, the students completed the vocabulary tests. We administered the tests in order of decreasing difficulty. The students could only start a new test page after they had handed in the previous test page to avoid answer revision.

5 The teachers held a master’s degree in English-language education and had been specifically trained for the project.

6 In Lesson 1, the teachers introduced target words orally. Students first repeated the body words in English together in a normal voice; then, they had to repeat words in different ways (loudly, softly). In Lesson 2, the teachers brought a life-sized poster of a child to class and repeated and introduced further target words in English. In Lesson 3, the teachers showed word cards to introduce students to the spelling of words and students engaged in flash reading.

7 Peers served as interpreters when languages other than German were spoken.

8 Although students in the intervention groups did not have any exposure to target words during the intervention time in Lesson 1, this warm-up was necessary to prevent classroom rejection of the plurilingual approach where the L1 is used to understand new words and to convey appreciative attitudes.

References

- Agustín-Llach, M. 2019. “The Impact of Bilingualism on the Acquisition of an Additional Language: Evidence from Lexical Knowledge, Lexical Fluency, and (Lexical) Cross-Linguistic Influence.” International Journal of Bilingualism 23 (5): 888–900. doi:10.1177/1367006917728818.

- Arteagoitia, I., and L. Howard. 2015. “The Role of the Native Language in the Literacy Development of Latino Students in the U.S.” In Multilingual Education: Between Language Learning and Translanguaging, edited by J. Cenoz, and D. Gorter, 61–83. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Backhaus, O., F. Petermann, and P. Hampel. 2010. “Effekte des Anti-Stress-Trainings in der Grundschule [Effects of a Stress Management Training Program in Primary Schools].” Kindheit und Entwicklung 19 (2): 119–128. doi:10.1026/0942-5403/a000015.

- Bailey, E. G., and E. J. Marsden. 2017. “Teachers’ Views on Recognising and Using Home Languages in Predominantly Monolingual Primary Schools.” Language and Education 31 (4): 283–306. doi:10.1080/09500782.2017.1295981.

- Becker, C., G. Gerngross, and H. Puchta. 2013a. Playway 3: Activity Book mit Audio-CD und Übungssoftware [Playway 3: Activity Book with Audio CD and Training Software]. Innsbruck, Austria: Helbling & Klett.

- Becker, C., G. Gerngross, and H. Puchta. 2013b. Playway 3: Pupil’s Book. Innsbruck, Austria: Helbling & Klett.

- Brophy, C. 2001. “Generic and/or Specific Advantages of Bilingualism in a Dynamic Plurilingual Situation: the Case of French as Official L3 in the School of Samedan (Switzerland).” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 4 (1): 38–49. doi:10.1080/13670050108667717.

- Busse, V. 2017. “Plurilingualism in Europe: Exploring Attitudes Towards English and Other European Languages among Adolescents in Bulgaria, Germany, the Netherlands, and Spain.” The Modern Language Journal 101 (3): 566–582. doi:10.1111/modl.12415.

- Busse, V., J. Cenoz, N. Dalmann, and F. Rogge. 2020. “Addressing Linguistic Diversity in the Language Classroom in a Resource-Oriented way: An Intervention Study with Primary School Children.” Language Learning 70: 382–419. doi:10.1111/lang.12382.

- Candelier, M. 2017. “Awakening to Languages and Educational Language Policy.” In Language Awareness and Multilingualism, edited by J. Cenoz, D. Gorter and S. May, 3rd ed., 161–172. Berlin, Germany: Springer.

- Carroll, J. B. 1963. “A Model of School Learning.” Teachers College Record 64 (8): 723–733.

- Cattell, R. B. 1961. Culture Free Intelligence Test, Scale 3. Champaign, IL: Institute for Personality and Ability Testing.

- Cenoz, J. 2013. “The Influence of Bilingualism on Third Language Acquisition: Focus on Multilingualism.” Language Teaching 46 (1): 71–86. doi:10.1017/S0261444811000218.

- Cenoz, J. 2019. “Translanguaging Pedagogies and English as a Lingua Franca.” Language Teaching 52: 71–85. doi:10.1017/S0261444817000246.

- Cenoz, J., and D. Gorter. 2019. “Multilingualism, Translanguaging, and Minority Languages in SLA.” The Modern Language Journal 103 (S1): 130–135. doi:10.1111/modl.12529.

- Cook, V. J. 1992. “Evidence for Multicompetence.” Language Learning 42 (4): 557–591. doi:10.1111/j.1467-1770.1992.tb01044.x.

- Council of Europe. 2018. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment: Companion Volume with new Descriptors. https://rm.coe.int/cefr-companion-volume-with-new-descriptors-2018/1680787989.

- Cummins, J. 2000. Language, Power and Pedagogy. Bilingual Children in the Crossfire. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

- Cummins, J. 2017. “Teaching for Transfer in Multilingual School Contexts.” In Bilingual Education: Encyclopedia of Language and Education, edited by O. García, A. Lin, and S. May, 103–115. Berlin, Germany: Springer.

- Durán, L., and D. Palmer. 2014. “Pluralist Discourses of Bilingualism and Translanguaging Talk in Classrooms.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 14 (3): 367–388. doi:10.1177/1468798413497386.

- Edele, A., S. Kempert, and K. Schotte. 2018. “Does Competent Bilingualism Entail Advantages for the Third Language Learning of Immigrant Students?” Learning and Instruction 58: 232–244. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.07.002.

- Ellis, P. D. 2010. The Essential Guide to Effect Sizes: Statistical Power, Meta-Analysis, and the Interpretation of Research Results. Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Faul, F., E. Erdfelder, A. G. Lang, and A. Buchner. 2007. “G* Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences.” Behavior Research Methods 39: 175–191. doi:10.3758/BF03193146.

- García, O., and A. Lin. 2016. “Translanguaging and Bilingual Education.” In Bilingual and Multilingual Education, edited by O. García, A. Lin, and S. May, 117–130. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

- Göbel, K., and B. Frankemölle. 2020. “Interkulturalität und Wohlbefinden im Schulkontext [Interculturalism and Well-Being in the School Context].” In Handbuch Stress und Kultur [Handbook on Stress and Culture], edited by T. Ringeisen, P. Genkova, and F. T. L. Leong, 1–17. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Göbel, K., and A. Helmke. 2010. “Intercultural Learning in English as a FL Instruction: The Importance of Teachers’ Intercultural Experience and the Usefulness of Precise Instructional Directives.” Teaching and Teacher Education 26 (8): 1571–1582. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2010.05.008.

- Göbel, K., and S. Vieluf. 2018. “Specific Effects of Language Transfer Promoting Teaching and Insights Into the Implementation in EFL-Teaching.” Orbis Scholae 11 (3): 103–122.

- Gogolin, I. 2013. “The “Monolingual Habitus” as the Common Feature in Teaching in the Language of the Majority in Different Countries.” Per Linguam 13 (2): 38–49. doi:10.5785/13-2-187.

- Grosjean, F. 1989. “Neurolinguists, Beware! The Bilingual is not two Monolinguals in one Person.” Brain and Language 36 (1): 3–15. doi:10.1016/0093-934X(89)90048-5.

- Hall, G., and G. Cook. 2012. “Own-language use in Language Teaching and Learning.” Language Teaching 45 (3): 271–308. doi:10.1017/S0261444812000067.

- Henschel, S., B. Heppt, S. Weirich, A. Edele, S. Schipolowski, and P. Stanat. 2019. “Zuwanderungsbezogene Disparitäten.” [Migration-Related Disparities.] In IQB-Bildungstrend 2018. Mathematische und naturwissenschaftliche Kompetenzen am Ende der Sekundarstufe I im zweiten Ländervergleich [IQB Education Trend 2018. Mathematical and Scientific Competences at the end of Lower Secondary Level in a Second State Comparison], edited by P. Stanat, S. Schipolowski, N. Mahler, S. Weirich, and S. Henschel, 295–336. Münster: Waxmann.

- Hesse, H. G., K. Göbel, and J. Hartig. 2008. “Sprachliche Kompetenzen von mehrsprachigen Jugendlichen und Jugendlichen nicht-deutscher Erstsprache.” [Linguistic Competences of Plurilingual Adolescents and Adolescents with a First Language Other Than German.] In Unterricht und Kompetenzerwerb in Deutsch und Englisch. Ergebnisse der DESI-Studie [Education and Skills Acquisition in German and English. Results of the DESI-Survey], edited by E. Klieme, 208–230. Weinheim, Germany: Beltz.

- Hirosh, Z., and T. Degani. 2018. “Direct and Indirect Effects of Multilingualism on Novel Language Learning: An Integrative Review.” Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 25: 892–916. doi:10.3758/s13423-017-1315-7.

- Hopp, H., J. Jakisch, S. Sturm, C. Becker, and D. Thoma. 2020. “Integrating Multilingualism Into the Early FL Classroom: Empirical and Teaching Perspectives.” International Multilingual Research Journal 14 (2): 146–162. doi:10.1080/19313152.2019.1669519.

- Hopp, H., and D. Thoma. 2021. “Effects of Plurilingual Teaching on Grammatical Development in Early Foreign-Language Learning.” The Modern Language Journal, 105: 464–483

- Hopp, H., M. Vogelbacher, T. Kieseier, and D. Thoma. 2019. “Bilingual Advantages in Early FL Learning: Effects of the Minority and the Majority Language.” Learning and Instruction 61: 99–110. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.02.001.

- Huang, X., N. Kim, and K. Christianson. 2019. “Gesture and Vocabulary Learning in a Second Language.” Language Learning 69 (1): 177–197. doi:10.1111/lang.12326.

- Jarvis, S., and A. Pavlenko. 2008. Crosslinguistic Influence in Language and Cognition. New York & London: Routledge.

- Krohne, H. W., B. Egloff, C. W. Kohlmann, and A. Tausch. 1996. “Untersuchungen mit Einer Deutschen Version der “Positive and Negative Affect Schedule” (PANAS) [Investigation with a German Version of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS)].” Diagnostica 42: 139–156.

- Krumm, H. J., and E. M. Jenkins. 2001. Kinder und ihre Sprachen - lebendige Mehrsprachigkeit [Children and their languages: living multilingualism]. Vienna: Eviva.

- Lenhard, W., and A. Lenhard. 2016. Calculation of effect sizes. Dettelbach: Psychometrica. Retrieved from https://www.psychometrica.de/effect_size.html.

- Leonet, O., J. Cenoz, and D. Gorter. 2020. “Developing Morphological Awareness Across Languages: Translanguaging Pedagogies in Third Language Acquisition.” Language Awareness 29 (1): 41–59. doi:10.1080/09658416.2019.1688338.

- Liddicoat, A. J., and T. J. Curnow. 2014. “Students’ Home Languages and the Struggle for Space in the Curriculum.” International Journal of Multilingualism 11 (3): 273–288. doi:10.1080/14790718.2014.921175.

- Lin, A. M. 2016. Language Across the Curriculum & CLIL in English as an Additional Language (EAL) Contexts: Theory and Practice. Singapore: Springer.

- Lyster, R., J. Quiroga, and S. Ballinger. 2013. “The Effects of Biliteracy Instruction on Morphological Awareness.” Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education 1 (2): 169–197. doi:10.1075/jicb.1.2.02lys.

- Maluch, J. T., S. Kempert, M. Neumann, and P. Stanat. 2015. “The Effect of Speaking a Minority Language at Home on FL Learning.” Learning and Instruction 36: 76–85. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2014.12.001.

- OECD. 2015. Immigrant Students at School: Easing the Journey Towards Integration. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Philp, J., and S. Duchesne. 2016. “Exploring Engagement in Tasks in the Language Classroom.” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 36: 50–72. doi:10.1017/S0267190515000094.

- Plonsky, L., and F. Oswald. 2014. “How big is “Big”? Interpreting Effect Sizes in L2 Research.” Language Learning 64 (4): 878–912. doi:10.1111/lang.12079.

- Pulinx, R., P. van Avermaet, and O. Agirdag. 2017. “Silencing Linguistic Diversity: the Extent, the Determinants and Consequences of the Monolingual Beliefs of Flemish Teachers.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 20 (5): 542–556. doi:10.1080/13670050.2015.1102860.

- Roden, I., F. D. Zepf, G. Kreutz, D. Grube, and S. Bongard. 2016. “Effects of Music and Natural Science Training on Aggressive Behavior.” Learning and Instruction 45: 85–92. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.07.002.

- Sanz, C. 2000. “Bilingual Education Enhances Third Language Acquisition: Evidence from Catalonia.” Applied Psycholinguistics 21 (1): 23–44. doi:10.1017/S0142716400001028.

- Statista Research Department. 2020. Topic: Migration in Europe. https://www.statista.com/topics/4046/migration-in-europe/

- Statistisches Bundesamt. 2019. Bevölkerung und Erwerbstätigkeit. Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund - Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus 2018 [Population and employment. Population with a migration background – results of the 2018 micro-census]. Retrieved from https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Migration-Integration/Publikationen/Downloads-Migration/migrationshintergrund-2010220187004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile.

- Swain, M. 2013. “The Inseparability of Cognition and Emotion in Second Language Learning.” Language Teaching 46 (2): 195–207. doi:10.1017/S0261444811000486.

- Taylor, R. D., E. Oberle, J. A. Durlak, and R. P. Weissberg. 2017. “Promoting Positive Youth Development Through School-Based Social and Emotional Learning Interventions: A Meta-Analysis of Follow-up Effects.” Child Development 88 (4): 1156–1171. doi:10.1111/cdev.12864.

- Verhallen, M., and R. Schoonen. 1993. “Lexical Knowledge of Monolingual and Bilingual Children.” Applied Linguistics 14 (4): 344–363. doi:10.1093/applin/14.4.344.

- Watson, D., L. A. Clark, and A. Tellegen. 1988. “Development and Validation of Brief Measures of Positive and Negative Affect: The PANAS Scales.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 54 (6): 1063–1070. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063.

- Wei, L. 2018. “Translanguaging as a Practical Theory of Language.” Applied Linguistics 39: 9–30. doi:10.1093/applin/amx039.

- Weiß, R. H. 2006. CFT 20-R Grundintelligenztest Skala 2 – Revision (CFT 20-R). Göttingen: Hogrefe.