ABSTRACT

This paper develops the notion of epistemic exclusion as a way of exploring the different types of silence and silencing that happen in English medium Rwandan classrooms. By focusing on classroom observationsof teachers’ pedagogic practices and the ways in which girls interact in the classrooms, we demonstrate how experiences of epistemic exclusion intersect with other mechanisms of marginalisation, in this case related to gendered norms and expected behaviours. Through thematic analysis of dual classroom observation schedules and video transcriptions from 32 Primary Six and Secondary Three lessons in four government schools, we have identified examples where learners’ engagement in the co-construction of language and subject knowledge was limited by classroom practices. Silence, and silencing, of girls was particularly observed in Secondary Three where reluctance to speak in class and respond to teachers’ questions, combined with lack of confidence as evidenced through body language, deprived girls from participating in spontaneous classroom talk. Conclusions discuss how silencing limits girls’ epistemic inclusion.

Introduction

In the research literature on the use of an unfamiliar language of learning and teaching (LoLT), such as English, in basic education, there is persistent evidence of quiet classrooms. These involve learners who are silent, reluctant to speak and who are constrained by the type of talk in which they can engage (Brock-Utne Citation2007; McKinney et al. Citation2015; Vuzo Citation2010). However, there is a need for a stronger theoretical basis for understanding how different forms of silence and silencing relate to broader learning processes and structural inequalities for multilingual children. In this paper, we draw on and extend Kiramba’s (Citation2018) idea of epistemic exclusion and argue that it allows a nuanced understanding of classroom silence and silencing for girls in English medium education (EME).

We focus on girls because, despite the significant evidence base for the detrimental impact of an unfamiliar LoLT for children across Sub-Saharan Africa (Milligan, Desai, and Benson Citation2020), there has been a paucity of research that has focused particularly on girls’ experiences. This is perhaps surprising given the girls’ education focus in global and national education agenda, for example, related to Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 4 and 5. As the literature in this area (e.g. Adamson Citation2022; Akyeampong et al. Citation2018; Carter et al. Citation2020; Mjaaland Citation2018) demonstrates, despite efforts to increase school enrolments for girls there are still complex sociocultural inequalities that put girls at risk of poor engagement and dropout.

Our previous analysis of trends between girls’ English results in the 2018 Primary 6 (P6) and Secondary 3 (S3) National Examinations and contextual statistics of gender equality, such as community gendered attitudes and girls’ educational attendance and transition, suggested that language may contribute to inequalities and play an important role in girls’ learning outcomes. We showed that most girls and boys just about pass their English P6 examinations but that at S3 level, there are higher rates of failure among girls in every district of Rwanda (Uworwabayeho, Milligan, and Kuchah Citation2021). This calls for research which explores why most children are only just passing their English examinations at the end of primary schooling and why more than half of girls are failing by the end of lower secondary schooling. In this paper, we focus on P6 and S3 girls’ talk and silence to understand the relationship between an unfamiliar LoLT and girls’ classroom experiences. Our analysis is situated in Rwandan basic education where children learn in English from the first day of primary school despite significant evidence to suggest this acts as a barrier to learning (Sibomana Citation2017). Our conclusions suggest that this has significant implications for gender equity and inclusion in Rwanda, with resonances further afield.

Literature review

In Rwandan basic education, as in many contexts globally, students and teachers are engaged in two, parallel learning processes. The first is the requirement to engage with academic content related to the subject being studied; the second is to simultaneously develop English language proficiency since it is the language through which content is officially taught and assessed (Barrett and Bainton Citation2016). The use of an unfamiliar LoLT is associated with quiet classrooms where students are reluctant to speak, give very limited responses, or are silent (Brock-Utne Citation2007; McKinney et al. Citation2015; Ngwaru Citation2011; Vuzo Citation2010; Webb and Mkongo Citation2013). In fact, based on her study of Grade 4 students in Kenya when the LoLT shifts to the sole use of English, Kiramba (Citation2018, 307) argues that this monoglossic LoLT policy results in ‘extensive silencing’. These observations about restrictions on students’ ability and willingness to speak are particularly important because classroom talk plays a key role in the learning process. Vuzo (Citation2010, 5) writes that

classroom dialogue through an understandable language has a significant role to play in learning … [since] it is through interactions … that teachers and students work together to create intellectual and practical activities that shape both the form and content of the target subject as well as the processes and outcomes of individual development.

However, when the LoLT is not familiar and well-understood, this places dramatic limitations on the types of talk that are possible.

To fully appreciate the impact of the LoLT on classroom talk, it is necessary to go beyond the dichotomy of silence-talk, to explore the ways that children are ‘silenced’ even when they may be involved in limited talk. The concept of ‘safe-talk’, whereby children respond in single words or phrases in repetition or by completing a teacher’s sentence is particularly useful here (Hornberger and Chick Citation2001; Rubagumya Citation2003). While these children may not be silent, the prevalence of this type of talk positions learners as ‘mere recipients of information from the teacher’ (Kiramba Citation2018, 306) and restricts them from ‘producing their own meanings’ (Guzula, McKinney, and Tyler Citation2016, 3). It also provides minimal opportunity to practise the LoLT.

By contrast, many language scholars highlight the importance of classroom dialogue and different forms of talk in the learning process (Hardman and Abd-Kadir Citation2010; Webb and Mkongo Citation2013). Where this process is happening both in an unfamiliar language and in a specific discipline, complete with its own terminologies, Barrett and Bainton (Citation2016, 397) suggest that students are both ‘learning from talk’ and ‘learning to talk and write’ in the required language and register. In education systems where the official LoLT is different to the familiar language(s) of learners, the end goal will be that students can demonstrate their understanding in the LoLT. However, while developing that understanding, several writers highlight the value of using familiar languages for activities that encourage exploratory talk, enabling students to engage with subject content and negotiate meaning using their full language repertoire (Probyn Citation2015; Simasiku Citation2016). If students are precluded from opportunities to engage in a range of language activities and in different types of talk, either because of the language being used or types of pedagogy, their learning journeys will be ‘incomplete’ (Setati et al Citation2002, 139). It will also be ‘impossible’ (Qorro Citation2009, 71) for students to engage in critical thinking and inquiry-based learning, skills that are emphasised in curricula in most African countries (Mkimbili Citation2019; Ogunniyi and Rollnick Citation2015).

Arguing that pedagogy is too often neglected in global discussions of education priorities, Schweisfurth (Citation2015, 259) writes that ‘classroom interactions are at the heart of pedagogy’. The types of pedagogies used in the classroom play a fundamental role in the types of interaction, or talk, that can happen. For example, Webb and Mkongo (Citation2013, 149) note that the forms of dialogue that are ‘critical to quality learning … may be limited … in classrooms where teachers dominate discussion and where questions do not prompt higher-order thinking’. Classroom pedagogies are shaped by a range of factors, including policy and curriculum prescription; constraints such as class size and pressure to cover high volumes of content (Clegg and Afitska Citation2011); the sociocultural context (Vavrus Citation2009); and the teacher's proficiency in the LoLT (McCoy Citation2017; Nel and Müller Citation2010). Teachers’ individual beliefs about inclusion and exclusion, and their judgements about who is a ‘good’ or ‘weak’ student have also been shown to influence who gets to speak. This is through selective attention in turn taking and the types of feedback students receive, and unequal access to learning resources (Opoku-Amankwa Citation2009; Walker Citation2020). If some learners are perceived as more legitimate knowers (Kerfoot Citation2020), it follows that they will have more opportunities to partake in full-class talk, such as responding to teachers’ open questions and asking questions themselves.

While differences between children from different ethnic and language backgrounds and perceived academic ability are occasionally observed in the literature discussed thus far, we note the very limited reference to potential differences in talk and silence between girls and boys. The wider literature on girls’ classroom practice in Ghana (Akyeampong et al. Citation2018), Kenya (Lewin and Sabates Citation2011) and Tanzania (Adamson Citation2022) suggests girls may be called on less and be more reticent to speak. This may relate to their confidence in the LoLT (Alidou and Brock-Utne Citation2011). An important contribution here comes from Julé (Citation2004), who in an ethnographic longitudinal study of classroom practices of a female English language teacher in a Canadian Punjab Sikh School, found evidence of gendered use of linguistic space and gendered speech patterns which restrict girls’ participation in the classroom by limiting their sense of validation and legitimacy as participants. She again highlights the ways that the teacher can be a ‘powerful force in governing participation’ and argues that gender needs to be recognised as ‘a serious variable in speech production’ (154). In this paper, we particularly focus on girls’ experiences of classroom talk and the different mechanisms through which they are included and/or excluded from meaningful learning.

Conceptual framework

Kiramba's discussion of epistemic exclusion is a useful starting point for exploring the ways in which learning in an unfamiliar language, specifically English, can prevent children from gaining basic curricular content and participating in talk-based meaning-making activities. However, while Kiramba (Citation2018) discusses some of these in relation to epistemic exclusion, the term itself is not explicitly defined. We believe that a clear definition and shared understanding of the concept of epistemic exclusion enables analysis of classroom interaction that better illuminates the distinctions between different forms of silencing and their relationship to broader learning processes and structural inequalities.

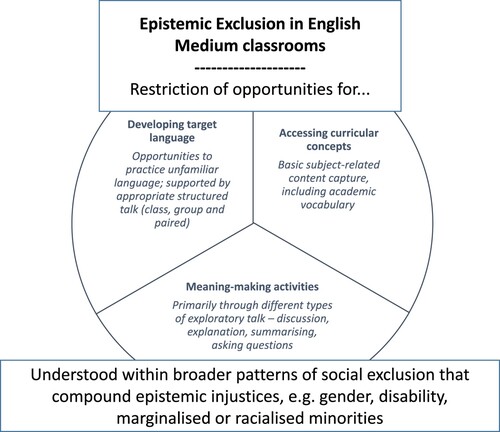

We define epistemic exclusion in English medium classrooms as the processes by which children are prevented from accessing new curricular concepts in the LoLT, given few opportunities for language development particularly through structured talk, and precluded from sustained engagement in meaning-making activities that require exploration through language (see ).

In this paper, we focus on meaning-making which can be defined as the processes by which understanding is enabled, or what Barnes (Citation1992, 123) describes as ‘working-on-understanding’. Drawing on observations of science classroom practice in South Africa, Tyler (Citation2018) identifies three strands of meaning-making: constrained, guided and spontaneous. The first refers to activities in which learners ‘submit to the authority of the teacher or other text in terms of topic and register choice’ (Citation2018, 60); in a classroom, this may refer to teacher questions with very limited responses, often repeating what is on the board or in the textbook. Guided meaning-making refers to activities that are set up by the teacher but that learners have some freedom in how they respond, such as exploratory talk about a particular topic, and summarising topics in their own words. Spontaneous meaning-making is when a child engages without external stimulus. Examples could include children taking risks and asking questions unprompted. In our consideration of epistemic exclusion, we are particularly concerned with guided and spontaneous meaning-making since these also suggest broader opportunities for learners to bring their own experiences and knowledges to their learning in the classroom.

This final point positions our understanding of epistemic exclusion within a broader framework of epistemic injustice (e.g. Fricker Citation2007; Anderson Citation2012; Masaka Citation2019; Balarin et al. Citation2021). For Fricker (Citation2007) and Anderson (Citation2012), a central tenet of enabling epistemic justice is participation in meaning-making activities, something that is often denied to individuals through their marginalisation as knowers and through the ways that they are (not) heard. In the context of EME in sub-Saharan Africa, the discussion of epistemic exclusion necessitates a broader analysis of the ‘Anglonormative’ (McKinney Citation2016) postcolonial condition where some knowledges hold higher value, usually those ‘locked up in foreign language forts’ (Qorro Citation2009).

From a sociocultural perspective, meaning-making includes both private and dialogic processes (Tyler Citation2018). In our consideration of epistemic exclusion, we particularly attend to the dialogic processes of talk. We focus on both silence and silencing to look beyond binaries of talk-silence to identify exclusion from the specific types of talk that could enable content acquisition, language development and meaning-making. While we are focused on talk, we note that this is just one way that children can both practise English and take part in meaning-making activities. There is scope for further research into the ways that these are restricted in monolingual writing and reading practices (see Makalela Citation2015).

It is also important to explore which characteristics and attributes put children at greater or lesser risk of epistemic exclusion, and how these relate to experiences of other forms of educational and social exclusion. We follow recent authors who have highlighted the ways that epistemic injustice interrelates with other structural injustices (Milligan et al. Citation2020; Cin and Mkwananzi Citation2021) and focus particularly on the interrelationship for girls. We argue that while issues relating to LoLT restrict opportunities for meaning-making for both girls and boys, in line with students’ English language abilities, when these are brought together with gendered behavioural expectations and patterns of interaction, girls’ epistemic exclusion is compounded. This is something that we have further theorised as a ‘double-burden’ (Milligan et al. CitationForthcoming).

The Rwandan context

In this paper, we focus on P6 and S3 classrooms in four schools in four districts from across Rwanda. These are the final and assessment years of primary and lower secondary education. Since 2019, children have learnt in English from the first year of primary school (MINEDUC Citation2019), representing a shift from previous policy for Kinyarwanda to be used in the first three years. This most recent LoLT policy shift continues a series of changes – from French to Kinyarwanda to English – in the postcolonial era (Sibomana Citation2017). Throughout the basic education cycle, children learn the competence-based curriculum, introduced in 2015. Some of the key competences include critical thinking, problem-solving and cooperation alongside cross-cutting themes such as peace and sustainability (Nsengimana et al. Citation2020). Another aspect of the new competence-based curriculum is the inclusion of gender as a cross-cutting issue that is expected to be catered for in each lesson. Communication in English is one of the generic competencies that all teachers irrespective of their specific subjects should equip learners with. Learners are expected therefore to effectively communicate in English through explanations, arguments, and drawing relevant conclusions (Rwanda Education Board Citation2015). However, this relies on high levels of language proficiency and confidence in the LoLT for both teachers and learners (Roussel et al. Citation2017) which, as research in Rwanda shows, is not yet the case (Sibomana Citation2017).

Rwanda has taken great strides in achieving gender parity in terms of access to and completion of both primary and lower secondary schools. According to the 2020/2021 Education Statistics YearBook (MINEDUC Citation2022), the number of learners across all levels of education was 4,033,046 with more girls (51%) than boys. The participation rate of learners aged between 7 and 12 years (primary age) and 13–18 years (secondary age) respectively stands at 99.3% and 76.4%. For both groups the percentage of girls is higher than boys. However, research on gender-related issues still advocates for education quality improvement, particularly related to girls’ learning outcomes (e.g. Janvier and Andala Citation2021).

We are not aware of any research that has focused on girls’ language use and talk within Rwandan classrooms nor its relationship to girls’ broader educational and social experiences. However, based on USAID gender analysis through LEARN project report (2014), some of the most influential factors that hinder girls’ achievement and advancement include the gendered norm of female responsibility for household tasks that diverts time and attention from school/teaching, unplanned pregnancy which leads to increasing childcare responsibilities, and environments that discourage the participation of girls. Additionally, we note some of the cultural norms that may add particular contextualisation and may resonate to other classroom settings. Here, we are minded of two Kinyarwanda proverbs. The first – nta nkokokazi ibika isake ihari (no hen can shout when the rooster is around) implies that it would be unusual for a girl or woman to speak at social events if a man is there. The second – umugore arabyina ntahamiriza! (women can dance but cannot make hero's dance like men) suggests that women should act gently as opposed to men's energetic action. Based on the lived experiences of Dorimana, Uwizemariya and Uworwabayeho, we suggest these may still influence some girls’ behaviours, particularly their freedom and confidence to speak in public.

Methodology

The data analysed for this article is part of the qualitative component of a sequential mixed-methods exploratory case study (Leech and Onwuegbuzie Citation2009) of girls’ educational experiences and outcomes in Rwandan EME basic education (see Uworwabayeho, Milligan, and Kuchah Citation2021 for the first phase of the study). In the qualitative component of the wider study, data was collected through dual classroom observations, narrative interviews with a total of 48 Primary six (P6) and Secondary three (S3), girls and individual interviews with 32 teachers from four districts in the country, to enable depth of understanding of girls’ experiences, both inside and outside the classroom. The data presented and discussed in this paper is drawn from 32 lesson observations across eight P6 and S3 classrooms, undertaken by Dorimana and Uwizemariya who separately observed (i) teacher's pedagogic practice, language use and topic coverage and (ii) the actions of girls in each classroom (including when they talked, how they followed the content and their engagement in classroom activities). The lessons in P6 covered subject areas such as Mathematics, Science & Elementary Technology, Social & Religious Studies and English Language and each lasted between 40 and 50 min. S3 subjects included Biology, Chemistry, Geography & Environment, History & Citizenship and Mathematics and lasted between 50 min and 1 h. After each lesson, Dorimana and Uwizemariya reflected on how ‘engaged’ and ‘active’ girls were at different points in the lesson and these reflections guided our identification of epistemic moments which we use to illustrate our findings below. By focusing on girls, we saw different types of silence and silencing throughout the classroom and the differential forms of meaning-making available to them.

We analysed the observation schedules, the text from the videoed lessons, transcribed by Adamson, and the videos themselves for non-verbal incidents. Rather than conducting content or discourse analysis of the whole class, we focused on ‘epistemic moments’, the instances of student talk or silence which pointed to their epistemic inclusion and/or exclusion. Drawing on Wragg's (Citation1994) critical incident approach to observation analysis, we focused on moments that related to different forms of talk and silence. This was important so that we could account for girls who spoke very little or perhaps had a single instance of speaking, or trying to speak, in the observed lessons. All six authors were involved in the data analysis and interpretation, drawing on our different linguistic, cultural and pedagogical understandings to identify and reflect on the ‘epistemic moments’ discussed in the following section (see, for example, Dorimana and Uwizemariya Citation2022 for how their experiences as Rwanda women informed our analysis).

The research underwent ethical appraisal at both the University of Bath, UK and the University of Rwanda where the formal aspects of the project were reviewed before data generation began. Alongside this, we undertook a contextualised and dialogic approach to ethical research practice (Oyinloye Citation2021; McMahon and Milligan Citation2021), prioritising what research approach we all deemed ethical in the context of the pandemic and the associated social, economic and educational inequalities that accompanied it.

Findings

Primary 6

Performative participation

Overall, classroom observation data in all four districts revealed no consistent gendered differences in P6. However, lesson observations revealed a kind of performative participation. Classrooms were generally lively with learners raising their hands, clicking their fingers and calling the teacher's attention to respond to questions. However, learner participation was restricted to safe talk through one-word answers to closed questions or completing teacher-led sentences. These were generally modelled by the teacher to enable learners to memorise basic content and/or vocabulary linked with assessment. This example of one-word (choral) responses comes from a Science and Elementary Technology lesson on ‘Magnetic and non-magnetic materials’ in Kihere:

Is the coin attracted or not attracted?

Attracted

Is the paper attracted or not attracted?

Not attracted

The same teacher attempted to initiate collaborative work, by asking learners to find other examples of magnetic and non-magnetic materials in their groups, but this proved futile. Students continued to stare at her even after she had explained to them that group meant ‘with your seatmate’. After several attempts to encourage group work, she reformulated her question in a pattern they were familiar with: ‘Substance attracted by magnet are made by … Who can find, who can find?’ Many learners raised their hands to respond. The teacher repeated: ‘Made by … ’ and a girl responded in one word, ‘metal’. Then the teacher asked the whole class, ‘by … ’ and they responded in chorus, ‘metal’.

Safe talk was a very common strategy for generating classroom participation as in the following example from a P6 Social and Religious Sciences lesson at Kirehe:

‘Today, our lesson is about Latitude and longitude; lati …

Latitude

and Longi

Longitude

[…] Yes, thank you. […] the middle line of the latitude is the Equa …

Equator.

[…] it divides the earth into two pa …

Parts.

Safe talk and silencing

There were also examples of teacher practices which more actively silenced students. For example, in a maths lesson in Nyarugenge, the teacher did not allow students to answer questions even when they raised their hands, instead preferring to control the response himself. He had posed the question: ‘Think of a number, add 5 to it and the answer is 11. What is the number?’ All learners raised their hands enthusiastically to answer but the teacher wrote he word ‘solution’ on the board and continued:

Let the number be … Let the number be Y for example, okay?

Yes

Y + Five is equal ele … ?

Eleven

Y plus Five, what is the reverse of Five?

Is equal to Six

Reverse of Five!

[after some hesitation] 4

No [appoints another learner]

Negative 5

Yes, negative 5. Subtract 5, yes?

Yes

Y plus 5, subtract 5 equal eleven minus fi …

Five

The excerpt above is also an example of the teacher dismissing an incorrect answer and moving to appoint another student, without commenting on why Student 1's answer was wrong. This practice was frequently observed in P6 lessons and there were no instances, in the observed lessons, of the teacher giving or eliciting clear explanations why student answers were correct or wrong.

As stated earlier, there were no visible gendered patterns which might suggest that girls were being excluded in these classrooms. In fact, there were some examples of teachers explicitly encouraging girls and some lessons were characterised by greater participation from girls than boys, although this was often only a small number of girls. However, there was a consistent lack of opportunities for guided or spontaneous meaning-making even for those children who were called upon by the teacher.

Secondary 3

Reluctance, low self-confidence and silence

In contrast to P6, classroom observation in S3 revealed stark gendered patterns with girls appearing to be both silent and silenced. Teachers tended to appoint only students who raised their hands to respond to questions so students who did not volunteer were mostly silent and frequently disengaged from the lesson. In all S3 classes, girls demonstrated reluctance to raise their hands or respond to teacher questions. Their participation was therefore less frequent than boys, despite there being more girls in all classes. In a Geography lesson in Ruhango, for example, with 16 boys and 29 girls, only one girl consistently raised her hand, despite the teacher making some attempt to include other girls. Silence, in this case, cannot be solely attributed to the language barrier because the teacher consistently shifted from English to Kinyarwanda and encouraged students to respond in Kinyarwanda whenever he found that it was hard for them to respond in English. This use of both languages was observed in other lessons, sometimes in different ways, for example, the Mathematics teacher in Nyarugenge used English when speaking to the whole class but used Kinyarwanda to support small groups and individual students. However, despite being offered opportunities to use Kinyarwanda in some lessons, most girls rarely volunteered to speak.

Girls’ reluctance to participate in plenary activities was evidenced through their non-verbal and verbal demonstration of low self-confidence. In a History lesson in Nyarugenge, we observed that boys were more willing to take risks, even when they did not know the full answers to the teacher's questions. In an epistemic moment from a whole-class activity to write an introductory paragraph for the question ‘Explain the causes of the 2nd World War’, a boy volunteered to come to the board even though he did not know what he was expected to do as illustrated in our observation notes below:

The teacher then models to the student how he should start the introduction indicating that he should write, and he starts to do so. He writes, ‘The 2nd world war’ and then stops writing and turns round and says, ‘was the greatest war in our world’. The teacher responds, ‘The greatest, most destructive war in the whole world … aha?’ Student: ‘It took place … ’ Teacher: ‘MmmHmm? … It is starting when and ending when?’ The student turns back round to the board as if to write something but doesn’t yet and says, ‘It started in 1939’ (he is still hovering with the chalk next to the board as if unsure). Teacher: ‘1939 … up to?’ Students respond in chorus, ‘1945’. The teacher instructs the student standing at the board, ‘Write! Write there’.

The teacher looks around for a few seconds before calling a girl by name who has not raised her hand and she is giving the correct answers as the teacher repeats, ‘Allied powers and? … Axis powers’. The teacher then says, ‘Flowers’ and students respond with the hand gesture to praise the girl!

Girls’ reluctance to participate in whole class activities was also seen in their delayed and quiet responses to teacher questions. In Nyarugenge, some girls were observed bending over to hide their faces to avoid being called upon by the Geography teacher. Across the lessons observed, apart from one lesson where a boy was inaudible, each time the teacher asked a student to speak louder, it was a girl. Even when girls took the initiative to respond to teacher questions, reluctance was often suggested by their body language. The Geography lesson in Kirehe offers examples that were repeated across other lessons. When a question was posed by the teacher about Minerals, the first girl to raise her hand responded while still leaning over the desk and sat down even before she had finished speaking. This action, which suggests low self-confidence was remarkably different from boys who often stood up straight even if their responses were not often correct.

There was also evidence to suggest that LoLT may influence girls’ confidence to speak in class. In a History lesson on ‘The French Revolution’ in Ruhango, the teacher was eliciting a description of the taxation system in France from students and shifted from English to Kinyarwanda but including key vocabulary like ‘taxation’. Then he appointed one girl who stood up, leaning over, and spoke inaudibly, then quickly sat down. The teacher spoke to her in Kinyarwanda and she stood up again and explained her point in Kinyarwanda. She had been leaning on her desk but at the end of her point in Kinyarwanda she stood up straighter than before. The teacher then repeated her point still in Kinyarwanda, using intonation to encourage students to join in on certain words. This epistemic moment in the lesson suggests that there could be a link between girls’ confidence and a potential for guided meaning-making when a familiar language is used.

Pedagogies of silencing

Like in P6, lessons at S3 were mostly teacher-fronted with little opportunity for collaborative work which could aid engagement in guided and/or spontaneous meaning-making. Pedagogic practices also tended to focus on whether student responses were correct or not. As a result, students did not engage in meaning-making through exploring missing knowledge or misunderstandings. For example, in a Biology lesson in Ruhango, the teacher appointed a girl to respond to a question on the board:

She starts writing her answer but looks unsure about her answer and erases it with her hand. She writes another answer and is not quite finished when the teacher says, ‘[name of student], read!’ She turns round to look at the teacher who asks, ‘What you are write?’ She reads aloud what she has written, and the teacher says, ‘I thank you because you tried. It is not correct’ and she calls on another student.

This is an epistemic moment where students were not only restricted to constrained meaning-making activities such as reproducing previously learned knowledge but were not helped to transition to an understanding of the correct knowledge through engaging with their mistakes. What is more, in classrooms like those observed, where boys dominate classroom participation despite being in the minority, there is a danger of girls being further silenced by such practices.

Classroom observations also revealed wider classroom practices that contributed to silencing girls. Although some teachers made conscious effort to encourage girls to speak, this did not always result in inclusive practice. In the Biology lesson in Nyarugenge, when the teacher explicitly invited girls to speak, it was only after no-one had volunteered to answer her question. Focusing attention on girls at this point, when it already seemed clear that most otherwise active students did not understand, seemed likely to result in embarrassment rather than create a genuine space for girls’ participation. Even where girls volunteered to speak, as in the Geography lesson on ‘Climate in Africa’ in Ruhango, teacher feedback either highlighted their mistake without giving them an opportunity to self-correct or simply interrupted them and completed the answer. Such teacher practices with girls who are already grappling with wider gendered behavioural expectations and patterns of interaction can silence their potential contributions. However, in this class we also see one of the only examples of spontaneous meaning-making from girls, with one girl, following questions from two boys, asking a question rather than responding to the teacher's question. It is interesting to note that in the following extract, it is a girl (Sa) who asks the question and another girl (Sb) who volunteers to answer it and gets interrupted by the teacher:

I have a question teacher

uhum?

What's the relationship between … vegetation … and climate?’

The relationship between vegetation and Clima … ?

Climate

Who can tell us the relationship between vegetation and climate?’ [pointing to a girl who has raised her hand]

The vegetation are related between … The vegetation are related to climate … ’

How?’

… because when … when you have climate in good condition the plant can make grow … .

[interrupts and continues to explain the difference]

There was, however, some evidence of promising inclusive practice to support the participation of girls. In Nyarugenge, a female Geography teacher asked students to summarise the lesson in their own words, thus offering the opportunity to engage in guided meaning-making. A few boys raised their hands, and some girls were visibly hiding from the teacher's view. The teacher then loudly said several times, ‘I want a girl now’, and picked two girls seemingly randomly to come to the front and complete the task. The teacher helped the girls to do this, offering prompts where needed, and praised them when they were finished. This approach was quite different to the boys who had volunteered for the same task. They summarised the lesson more confidently but were not praised by the teacher. This example shows the teacher's awareness of a gender gap and explicit attempt to bridge this. It also suggests that where the teacher is less responsive to the gendered context of learning and this additional support is not offered, girls might remain silent.

Discussion

So far, we have provided examples of epistemic moments from P6 and S3 classrooms highlighting practices which restrict student talk in the LOLT and limits their classroom engagement in subject knowledge development. While we found no evidence of silence or gendered patterns in P6, there was evidence at S3 of girls being both silent and silenced. Silence was manifested in their general reluctance to speak and their verbal and non-verbal demonstration of low self-confidence. Apart from the very small number of girls who were active, the majority of S3 girls observed may be described as silent – those who did not volunteer to speak, were not called upon by the teacher and were visibly disengaged. While several factors might account for this, we suggest that ethno-cultural norms such as those expressed in the Rwandan proverbs cited above may limit girls’ freedom to speak in public. This is consistent with research by Adamson (Citation2022) which highlights the prevalence of fear and shame amongst Tanzanian secondary school girls, preventing them from fully participating in classroom interactions and thus, epistemically excluding them from opportunities to learn. Our findings also confirm previous research evidence (Brock-Utne Citation2007; McKinney et al. Citation2015) that for many students, the use of an unfamiliar LoLT such as English may lead to limited student responses, reluctance to speak or silence.

Through our analysis of classroom observations, it is evident that learning in English adds significant constraints to the ways that students talk in class. Kiramba (Citation2018, 304) concludes from classroom observations in a Kenyan primary school, that the LoLT and prevalence of teacher-controlled talk means that ‘whatever students might otherwise have said, all of those other possibilities were suppressed, silenced, de-legitimated’. In the context of the Rwandan classrooms described here, we see further evidence that silence happens not only in the ways that children do not speak, but also in the ways that when they do speak, it is often in repetition and chorusing so that their own voices and contributions are silenced (Brock-Utne Citation2007; Guzula, McKinney, and Tyler Citation2016; McKinney et al. Citation2015; Vuzo Citation2010). Exclusion through silencing was observed in P6 and S3 in the ways in which teacher-dominated talk constrained students to mainly repetition of memorised words or concepts and a reliance on safe talk (Rubagumya Citation2003) which restricts meaning-making and the chance to practice English. Studies in Kenya (e.g. Kiramba and Smith Citation2019; McCoy Citation2017) have suggested that teachers’ implicit authority and limited proficiency in the LoLT, may mean that they regulate classroom discourse in ways that limit spontaneous meaning making in the EME classroom. While this is not the focus of this paper, we suggest that the low pass rates obtained by most Rwandan girls and boys in their P6 English examinations (Uworwabayeho, Milligan, and Kuchah Citation2021), may be a result of limited opportunities to practice language. This raises significant concerns about how all learners transition to the secondary curriculum, especially for girls for whom the increased language demands may intersect with heightened gendered influences on their propensity to talk in the classroom (Akyeampong et al. Citation2018; Lewin and Sabates Citation2011).

At secondary level, where boys outperform girls throughout the country in English (Uworwabayeho, Milligan, and Kuchah Citation2021), we saw a broader range in the types of talk and silencing in the classroom. Silencing at S3 was further observed to emanate from pedagogic practices such as dismissing girls’ responses without giving them the opportunity to self-correct, interrupting and completing responses for them and putting girls at risk of embarrassment and humiliation. There were girls who may volunteer but were consistently not selected to answer a question, who only spoke in response to closed questions and may have been discouraged to speak because of real or anticipated teacher or peer reproachment (Adamson Citation2022). We would argue that the result for these girls is similar in terms of their epistemic exclusion from bringing their own views, questions and understandings to the learning process. By S3 level, EME is a clear contributing factor to girl's epistemic exclusion through the ways that they are not able to engage with new curricular concepts and practise English. Talk is integral to language development (Vuzo Citation2010) and to accessing new curricular concepts (Barrett and Bainton Citation2016). Therefore, the links between silence, silencing and these areas are clear. Regarding meaning-making, we see students engaged in a range of different constrained (a lot), guided (less) and spontaneous (very few) activities. In , we outline the main types specifically related to talk.

Table 1. Observed types of meaning-making through talk.

It is important to note that in each of the S3 classes observed, there were no more than three girls that were regularly called upon by the teachers and who engaged in a range of mainly constrained and guided meaning-making activities. Although we did not conduct an analysis that directly compared girls with boys, we do note that in S3 classrooms, a higher proportion of boys regularly partook in guided and spontaneous meaning-making activities. We particularly noted moments when boys asked spontaneous questions of the teacher in English. By contrast, there were no observable examples of girls developing their own arguments in English or drawing on their own experiences. Therefore, while there were some girls that did talk, there is more research needed about how they may be encouraged to partake in more sustained talk, particularly in relation to the sorts of spontaneous meaning-making that will support their engagement with the more cognitively and linguistically demanding Secondary curriculum.

Conclusion

This paper has provided evidence of classroom practices that limit learners’ engagement in guided and spontaneous meaning making activities in English medium schools in Rwanda and has argued that while there are no specific gendered patterns at primary level, there are significant gendered differences at S3 which show how girls are both silent and silenced. By focusing on girls’ experiences, we do not suggest that the issue of epistemic exclusion in EME classrooms only impacts girls. In fact, our findings support the overwhelming evidence that an unfamiliar LoLT is an exclusionary mechanism for most learners. While there are certainly many Rwandan boys that are silent and epistemically excluded, our research questions and data generation methods did not allow for in-depth analysis of these boys’ experiences. Our approach focused on girls’ classroom practice, enabling rich insights into the gendered dimension of learning in an unfamiliar LoLT. These rich insights were enabled by our research design which combined dual observations focused on girls’ learning experiences and an analysis of epistemic moments in lessons. By focusing on the quality of talk, we have gone beyond a talk-silence dichotomy to contribute new evidence of the impact of learning in an unfamiliar LoLT on learners’ participation (Kerfoot Citation2020). Cin and Mkwananzi (Citation2021, 6) write that ‘creating epistemically just processes and communities requires unsettling the prejudices and power hierarchies embedded in the social, economic and political structures that shape unjust practices and experiences’. Our findings suggest that in the context of Rwanda, both language and gender-based prejudices and power hierarchies shape unjust learning experiences for the girls in this study. It appears that the silencing effect of negative emotions might be amplified for girls when combined with gendered behavioural and interactional patters and greater exploration of these patterns is required.

In developing the concept of epistemic exclusion, we have shown that discussions of quality education need to go beyond access and physical presence to include ways in which teaching and learning processes provide opportunities for girls to engage in different types of meaning-making without being constrained by both societal and classroom practices that may silence them. The focus in this paper has been gendered experiences of epistemic exclusion. However, we believe that our epistemic exclusion framework, and particularly the ways that it relates to broader contextual forms of exclusion, makes it relevant as an analytical framework for exploring how other groups experience EME. While there has not been space in this article to explore in detail the wider cultural and socioeconomic inequalities that may explain these differences, there is scope for significant work that explores, for example, how an urban or rural context influences different types of exclusion.

Our conclusions have significant implications for the enactment of the Competence-based Curriculum in Rwanda, particularly in the ways that girls could be supported to engage with learning and effectively communicate in English. Without sustained support and time to practice English, we suggest that learners cannot talk, listen, read or write well enough to make meaning of learning activities. There are, therefore, lessons to be learnt here for girls’ education in Rwanda and more broadly for the fulfilment of SDG 4 and 5, in the sense that gender parity must not be limited to access to education. Rather, we need education systems in which girls are supported through primary and secondary education to achieve quality learning through epistemic inclusion for all.

Acknowledgements

The research reported in this paper received funding under the ESRC New Investigator scheme (ES/S001972/1) for which we are indebted. We would also like to thank the students and teachers who gave us permission to observe their classes and the two reviewers of this article for their very useful comments and suggestions..

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

We are in the process of making our data available on the UK data service and this will be available as soon as possible

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adamson, L. 2022. “Fear and Shame: Students’ Experiences in English-Medium Secondary Classrooms in Tanzania.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–16. doi:10.1080/01434632.2022.2093357

- Akyeampong, K., E. Carter, S. Higgins, P. Rose, and R. Sabates. 2018. Understanding Complementary Basic Education in Ghana: Investigation of the Experiences and Achievements of Children After Transitioning into Public Schools. Report for Department of International Development (DFID) Ghana office (November 2018), REAL Centre, University of Cambridge (2019). https://www.educ.cam.ac.uk/centres/real/downloads/Policy%20papers/CBE%20-%20Final%20Impact%20Evaluation%20-%20REAL%20RP_V2.pdf.

- Alidou, H., and B. Brock-Utne. 2011. “Teaching Practices – Teaching in a Familiar Language.” In Optimising Learning, Education and Publishing in Africa: The Language Factor. A Review and Analysis of Theory and Practice in Mother-Tongue and Bilingual Education in sub-Saharan Africa, edited by A. Ouane and C. Glanz, 157–185. Hamburg and Tunis Belvédère: UIL and ADEA.

- Anderson, E. 2012. “Epistemic Justice as a Virtue of Social Institutions.” Social Epistemology 26 (2): 163–173. doi:10.1080/02691728.2011.652211.

- Balarin, M., M. Paudel, P. Sarmiento, G. B. Singh, and R. Wilder. 2021. “Exploring Epistemic Justice in Educational Research.” Zenodo, doi:10.5281/zenodo.5502143.

- Barnes, D. 1992. “The Role of Talk in Learning.” In Thinking Voices, edited by K. Norman, 123–128. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

- Barrett, A. M., and D. Bainton. 2016. “Re-interpreting Relevant Learning: An Evaluative Framework for Secondary Education in a Global Language.” Comparative Education 52 (3): 392–407. doi:10.1080/03050068.2016.1185271.

- Brock-Utne, B. 2007. “Learning Through a Familiar Language Versus Learning Through a Foreign Language – A Look into Some Secondary School Classrooms in Tanzania.” International Journal of Educational Development 27 (5): 487–498. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2006.10.004.

- Carter, E., P. Rose, R. Sabates, and K. Akyeampong. 2020. “Trapped in Low Performance? Tracking the Learning Trajectory of Disadvantaged Girls and Boys in the Complementary Basic Education Programme in Ghana.” International Journal of Educational Research 100 (101541): 1–11.

- Cin, F. M., and F. Mkwananzi. 2021. “Participatory Arts for Social and Epistemic Justice.” In Post-Conflict Participatory Arts, 15–29,. edited by F. Mkwananzi & F. M. Cin London: Routledge.

- Clegg, J., and O. Afitska. 2011. “Teaching and Learning in Two Languages in African Classrooms.” Comparative Education 47 (1): 61–77. doi:10.1080/03050068.2011.541677

- Dorimana, A., and A. Uwizeyemariya. 2022. “Personal Reflections on Researching Language of Instruction and Girls’ Education in Rwanda.” In Girls Education and Language of Instruction: An Extended Policy Brief, edited by L.O. Milligan and L. Adamson, 16–17 University of Bath, UK.

- Fricker, M. 2007. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Guzula, X., C. McKinney, and R. Tyler. 2016. “Lang Aging-for-Learning: Legitimising Translanguaging and Enabling Multimodal Practices in Third Spaces.” Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 34 (3): 211–226. DOI: 10.2989/16073614.2016.1250360.

- Hardman, F., and J. Abd-Kadir. 2010. “Classroom Discourse: Towards a Dialogic Pedagogy.” In The Routledge International Handbook of English, Language and Literacy Teaching, xxiv, 556, edited by R. Andrews, D. Wyse, R. Andrews, J. V. Hoffman, A. N. Burn, A. Franks, C. Jewitt, G. R. Kress, and G. Moss. London: Routledge.

- Hornberger, N. H., and J. K. Chick. 2001. “Co-Constructing School Safetime: Safe Talk Practices in Peruvian and South African Classrooms.” In Voices of Authority: Education and Linguistic Difference, edited by M. Heller and M. Martin-Jones, 31–56. London: Ablex.

- Janvier, T., and H. O. Andala. 2021. “The Relationship Between Female Girls Education Policies and Academic Performance of Female Students in Rwanda.” Journal of Education 4 (6): 62–81. doi:10.53819/81018102t5016.

- Julé, A. 2004. Gender, Participation and Silence in the Language Classroom: Sh-Shushing the Girls. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kerfoot, C. 2020, March. “Towards Epistemic Justice: Constructing Knowers in Multilingual Classrooms.” In 2020 Conference of the American Association for Applied Linguistics (AAAL). AAAL.

- Kiramba, L. K. 2018. “Language Ideologies and Epistemic Exclusion.” Language and Education 32 (4): 291–312. doi:10.1080/09500782.2018.1438469.

- Kiramba, L. K., and P. H. Smith. 2019. “Her Sentence is Correct, Isn’t It? Regulative Discourse in English Medium Classrooms.” Teaching and Teacher Education 85: 105–114. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2019.06.011.

- Leech, N. L., and A. J. Onwuegbuzie. 2009. “A Typology of Mixed Methods Research Designs.” Quality & Quantity 43: 265–275. doi:10.1007/s11135-007-9105-3.

- Lewin, K. M., and R. Sabates. 2011. “Changing Patterns of Access to Education in Anglophone and Francophone Countries in Sub Saharan Africa: Is Education for All Pro-Poor?” CREATE Pathways to Access. Research Monograph 52.

- Makalela, L. 2015. “Translanguaging as a Vehicle for Epistemic Access: Cases for Reading Comprehension and Multilingual Interactions.” Per Linguam: A Journal of Language Learning = Per Linguam: Tydskrif vir Taalaanleer 31 (1): 15–29.

- Masaka, D. 2019. “Attaining Epistemic Justice Through Transformation and Decolonisation of Education Curriculum in Africa.” African Identities 17 (3-4): 298–309.

- McCoy, B. 2017. “Education in an Unfamiliar Language: Impact of Teachers’ Limited Language Proficiency on Pedagogy, a Situational Analysis of Upper Primary Schools in Kenya.” The Journal of Pan African Studies 10 (7): 178–196.

- McKinney, C. 2016. Language and Power in Post-Colonial Schooling: Ideologies in Practice. London: Routledge.

- McKinney, C., H. Carrim, A. Marshall, and L. Layton. 2015. “What Counts as Language in South African Schooling? Monoglossic Ideologies and Children’s Participation.” AILA Review 28 (1): 103–126. doi:10.1075/aila.28.05mck.

- McMahon, E., and L. O. Milligan. 2021. “A Framework for Ethical Research in International and Comparative Education.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 1–17. doi:10.1080/03057925.2021.1876553.

- Milligan, L. O. 2020. “Towards a Social and Epistemic Justice Approach for Exploring the Injustices of English as a Medium of Instruction in Basic Education.” Educational Review, 74(5): 927–941.

- Milligan, L.O., A. Dorimana, A. Uwizeyemariya, T. Sprague, A. Uworwabayeho, and K. Kuchah Forthcoming. The Differential Burden of Learning in English Medium Education for Rwandan girls. To be Submitted to: Comparative Education.

- Milligan, L. O., Z. Desai, and C. Benson. 2020. “A Critical Exploration of How Language-of-Instruction Choices Affect Educational Equity.” In Grading Goal Four: Tensions, threats and opportunities in the sustainable development goal on quality education, edited by A. Wulff, 116–134. Leiden: Brill.

- MINEDUC. 2019. “Communique: MINEDUC Endorses the Use of English as a Medium of Instruction in Lower Primary.” Retrieved from Communiqué: MINEDUC Endorses the Use of English Language as a Medium of Instruction in Lower Primary.

- MINEDUC. 2022. 2020/21 Education Statistical YearBook. Republic of Rwanda, February 2022.

- Mjaaland, T. 2018. “Negotiating Gender Norms in the Context of Equal Access to Education in North-Western Tigray, Ethiopia.” Gender and Education 30 (2): 139–155.

- Mkimbili, S. T. 2019. “Meaningful Science Learning by the Use of an Additional Language: A Tanzanian Perspective. African Journal of Research in Mathematics.” Science and Technology Education 23 (3): 265–275.

- Nel, N., and H. Müller. 2010. “The Impact of Teachers’ Limited English Proficiency on English Second Language Learners in South African Schools.” South African Journal of Education 30: 635–650. doi:10.15700/saje.v30n4a393

- Ngwaru, J. M. 2011. “Transforming Classroom Discourse and Pedagogy in Rural Zimbabwe Classrooms: The Place of Local Culture and Mother Tongue use.” Language, Culture and Curriculum 24 (3): 221–240. doi:10.1080/07908318.2011.609624.

- Nsengimana, T., L. Mugabo, H. Ozawa, and P. Nkundabakura. 2020. “Reflection on Science Competence-Based Curriculum Implementation in Sub-Saharan African Countries.” International Journal of Science Education, Part B: 1–14. doi:10.1080/21548455.2020.1778210.

- Ogunniyi, M., and M. Rollnick. 2015. “Pre-Service Science Teacher Education in Africa: Prospects and Challenges.” Journal of Science Teacher Education 26 (1): 65–79. doi:10.1007/s10972-014-9415-y.

- Opoku-Amankwa, K. 2009. “‘Teacher Only Calls Her Pets’: Teacher’s Selective Attention and the Invisible Life of a Diverse Classroom in Ghana.” Language and Education 23 (3): 249–262. DOI: 10.1080/09500780802582539.

- Oyinloye, B. 2021. “Towards an Ọmọlúàbí Code of Research Ethics: Applying a Situated, Participant-Centred Virtue Ethics Framework to Fieldwork with Disadvantaged Populations in Diverse Cultural Settings.” Research Ethics 17 (4): 401–422. doi:10.1177/17470161211010863.

- Probyn, M. 2015. “Pedagogical Translanguaging: Bridging Discourses in South African Science Classrooms.” Language and Education 29 (3): 218–234. doi:10.1080/09500782.2014.994525.

- Qorro, M. A. S. 2009. “Parents’ and Policy Makers’ Insistence on Foreign Languages as Media of Education in Africa: Restricting Access to Quality Education – for Whose Benefit?” In Languages and Education in Africa: A Comparative and Transdisciplinary Analysis, edited by B. Brock-Utne and I. Skattum, 57–82. Oxford: Symposium Books.

- Roussel, S., D. Joulia, A. Tricot, and J. Sweller. 2017. “Learning Subject Content Through a Foreign Language Should not Ignore Human Cognitive Architecture: A Cognitive Load Theory Approach.” Learning and Instruction 52: 69-79. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2017.04.007

- Rubagumya, C. M. 2003. “English-Medium Primary Schools in Tanzania: A New ‘Linguistic Market’ in Education?” In Language of Instruction in Tanzania and South Africa.. Edited by B. Brock-Utne, Z. Desai and M. Qorro, 149–169. Dar-es-Salaam: E & D Ltd.

- Rwanda Education Board. 2015. Competence-Based Curriculum. Curriculum Framework Pre-Primary to Upper Secondary. Kigali:: Rwanda Education Board.

- Schweisfurth, M. 2015. “Learner-Centred Pedagogy: Towards a Post-2015 Agenda for Teaching and Learning.” International Journal of Educational Development 40: 259–266. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2014.10.011.

- Setati, M., J. Adler, Y. Reed, and A. Bapoo. 2002. “Incomplete Journeys: Code Switching and Other Language Practices in Mathematics, Science and English Language Classrooms in South Africa.” Language and Education 16 (2): 128–149.

- Sibomana, E. 2017. “A Reflection on Linguistic Knowledge for Teachers of English in Multilingual Contexts.” Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 35 (1): 93–104. doi:10.2989/16073614.2017.1302351.

- Simasiku, L. 2016. “The Impact of Code Switching on Learners' Participation During Classroom Practice.” Studies in English Language Teaching 4 (4): 157–167.

- Tyler, R. L. 2018. “Semiotic Repertoires in Bilingual Science Learning: A Study of Learners-Meaning-Making Practices in Two Sites in a Cape Town High School.” Doctoral Thesis, University of Cape Town.

- Uworwabayeho, A., L. O. Milligan, and K. Kuchah. 2021. “Mapping the Emergence of a Gender Gap in English in Rwandan Primary and Secondary Schools.” Issues in Educational Research 31 (4): 1312–1329.

- Vavrus, F. 2009. “The Cultural Politics of Constructivist Pedagogies: Teacher Education Reform in the United Republic of Tanzania.” International Journal of Educational Development 29 (3): 303–311. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2008.05.002.

- Vuzo, M. 2010. “Exclusion Through Language: A Reflection on Classroom Discourse in Tanzanian Secondary Schools.” Papers in Education and Development 29: 14–36.

- Walker, L. B. 2020. “Inclusion in Practice: An Explanatory Study of How Patterns of Classroom Discourse Shape Processes of Educational Inclusion in Tanzanian Secondary School Classrooms.” Doctoral Thesis, Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge. doi:10.17863/CAM.51659.

- Webb, T., and S. Mkongo. 2013. “Classroom Discourse.” In Teaching in Tension: International Pedagogies, National Policies, and Teachers’ Practices in Tanzania, edited by F. Vavrus and L. Bartlett, 149–168. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Wragg, E. 1994. An Introduction to Classroom Observation. London: Routledge.