Abstract

The aim of this study was to develop and validate a multidimensional open thinking scale (OTS) in order to measure adult learners’ open thinking as a key learning outcome of open educational practices (OEP) through a three-phase process of item generation, theoretical analysis, and psychometric analysis. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses of data from 610 students in 24 countries revealed a clear structure consisting of six constructs of open thinking: openness to multiple perspectives, openness to new learning, openness to collaboration, openness to sharing, openness to change, and openness to diversity and inclusion. Known-groups validity tests showed that the more frequently a learner is exposed to OEP, the higher the OTS scores obtained. Results suggest that OTS could contribute to OEP and research by defining and elaborating on the concept of open thinking, exploring its relationship to learners’ OEP experiences, and measuring and developing students’ open thinking.

Introduction

The rapid adoption of digital and network technologies in higher education has made it possible for educators to adopt open educational practices (OEP) through being able to readily access, utilize, and create open educational resources (OER). Although OEP may take various forms, their most popular form is considered to be the use of OER. OER are, in effect, “teaching, learning and research materials that make use of appropriate tools, such as open licensing, to permit their free reuse, continuous improvement and repurposing by others for educational purposes” (UNESCO, Citation2019, p. 9), and they support educators and learners in collaboratively creating, shaping, and advancing knowledge together by adopting open technologies. As Bonk (Citation2009) rightfully described in his book The World is Open: How Web Technology is Revolutionizing Education, web technology has opened up education so that people can learn anything from each other at any time using online materials created by someone they have never met and often will never meet. OEP draw upon web technology and OER to promote quality teaching and learning and facilitate flexible and open thinking in an open learning environment.

Although several studies have revealed positive outcomes associated with OEP in higher education contexts, they have focused mainly on policy and administrative benefits, and student satisfaction and motivation with OEP experiences. What researchers have failed to address is a new form of learning outcome created by the openness and open pedagogy embedded within an OEP environment (UNESCO, Citation2014). We refer to this new form of learning outcome that challenges closed types of thinking as open thinking. Yet, despite its importance as a possible key learning outcome of OEP and a necessary competency for the 21st century learning, open thinking has not been the subject of OEP research. This study is an attempt to fill a gap in the literature by clarifying the meanings of open thinking and empirically investigating its underlying dimensions through the development and validation of a scale which measures open thinking as a learning outcome of open education.

Outcome studies of OEP

Not surprisingly, the benefits and challenges of OEP using OER have been widely researched (e.g., Hilton, Citation2016; Koseoglu et al., Citation2020; Pawlyshyn et al., Citation2013; Weller et al., Citation2018). Initially, a raft of studies investigated administrative benefits such as accessibility, cost-efficiency, and retention rate of OEP. As main outcomes, they reported improved accessibility to multimedia resources at little or no cost (Afolabi, Citation2017; DeVries, Citation2019; Dutta, Citation2016; Hilton, Citation2016), reaching out to potential learners who are geographically, socially, economically, or otherwise excluded from traditional education (Croft & Brown, Citation2020), together with improved pass rates and learning performance of students (Chiorescu, Citation2017; Colvard et al., Citation2018; Pawlyshyn et al., Citation2013)—all credited to the adoption and widespread use of OER. Another line of studies has examined the perceptions and experiences of university students who experienced OEP using OER and revealed overall satisfaction and high motivation (Sandanayake, Citation2019), favorable views of the course’s open textbook (Illowsky et al., Citation2016), improved self-directed skills and copyright consciousness (Lin, Citation2019), and improved skills to assess the credibility of sources, and analyze arguments, while both asking and answering clarifying and challenging questions (Rahayu & Sapriati, Citation2018).

Open thinking as a critical outcome of OEP

A relatively small, yet critical, body of OEP outcome research concerns what might be termed the openness characteristic of OER and OEP, and subsequent learning outcomes. According to UNESCO (Citation2014), openness is creating a new form of learning outcome that challenges closed communities by instead inviting learners to engage in an open learning community with diverse learners, the world’s best teachers, and distributed knowledge and resources. Croft and Brown (Citation2020) have claimed the openness philosophy embedded in OEP encourages learners to embrace conflicting views, broaden perspectives, value challenging but flexible attitudes, and be aware of equity and inclusion in society. Hug (Citation2017) claimed that openness promotes “not only multi-perspective views, well-reasoned applications of methods and thoughtful thinking but also abilities to become sensitive towards styles, languages and cultures of knowledge and science and to call into question basic assumptions” (p. 81). Gallardo et al. (Citation2017) argued that accommodating different perspectives would be a big challenge in more conventional settings where OER and OEP are not embedded into teaching practices. This new and critical learning outcome of OEP, which can be thought of as open thinking in that it diverges from established closed ways of thinking, has been the subject of little research despite its obvious importance as an OEP learning outcome.

Concepts of open thinking

Although studies to date (e.g., Croft & Brown, Citation2020; Hug, Citation2017; UNESCO, Citation2014) have agreed that a learning outcome related to openness philosophy is one of the most critical learning outcomes of OEP, there still exists conceptual and methodological vagueness around open thinking as a learning outcome of OEP. Little research has pursued the concepts of open thinking or developed an instrument for its measurement. Granted, the concept of open thinking and openness varies depending on the specific context of OEP, and this together with the changing needs of societies and cultures makes it difficult to define precisely (Bozkurt et al., p. 78); nevertheless, there are certain qualities of open thinking that the relevant literature can offer. Below are five distinct but interrelated potential dimensions of open thinking identified from the literature and categorized so as to develop an initial concept of open thinking.

Valuing new perspectives

Researchers have employed the concept of actively open-minded thinking, defined as the disposition to seek evidence and be open to different opinions that may conflict with one’s initial opinions (Svedholm-Häkkinen & Lindeman, Citation2018). Open-minded thinking is closely linked to valuing new and multiple perspectives and accepting changes. Those with open-minded thinking are able to look at issues from multiple perspectives while valuing new perspectives brought by other people and change their beliefs or actions in response to new information or evidence, instead of adhering to their own opinions (Baron, Citation2019; Svedholm-Häkkinen & Lindeman, Citation2018), based on their epistemological belief in multiple truths. A critical competency for those who accept new perspectives is flexible thinking. According to Barak and Levenberg (Citation2016), flexible thinking is a concept closely related to open-minded thinking and plays an important role in seeking different perspectives and options, adapting to new learning environments, and accepting changes. In this regard, we included openness to new perspectives as one of the dimensions of the initial version of the OTS (see Phase 1: Item generation) and considered items from an epistemological questionnaire, a flexibility thinking scale, and open-minded thinking scales in generating items for that dimension.

Fostering different ways of learning

Studies have suggested that open thinking embraces diverse sources and differing ways of learning including self-directed learning. In an early open education study, Lewis (Citation1986) emphasized that the wide range of learning strategies and options available to learners in an open learning environment could lead learners to be more open in accepting multiple formats and different types of learning resources and styles of learning. The Commonwealth of Learning (Citation2000) has also argued that open education allows learners’ choices about media or formats of content, types of resources and support, places and paces of study, and entry and exit and thus possibly advances flexibility in their ways of learning. Flexibility, a concept closely related to an openness to new perspectives, plays an important role in adapting to different ways of learning as well (Barak & Levenberg, Citation2016). It is a quality that can grow through open and online learning experiences (Tseng et al., Citation2020). In the context of OEP using OER, Peter and Deimann (Citation2013), in an attempt to reconstruct the meaning of openness in the context of open education, noted that, historically, student-driven or student-directed learning, self-education, and the right to access knowledge have been manifestations of openness. Bonk et al. (Citation2015) have also found that self-directed learning is essential for success in open education and can be cultivated during the open learning process. Having reflected on the above discussion, we added openness to different ways of learning as another critical dimension of the initial OTS and considered items from self-directed learning scales along with other related scales.

Promoting collaboration

A number of studies have emphasized how openness may facilitate collaboration (Ahn et al., Citation2014; Edwards, Citation2015; Ren, Citation2019). Ahn et al. pointed out two dimensions of openness in education: open production, in which numerous individuals collaborate in creating and revising various forms of knowledge (e.g., source code, content and software); and open appropriation, in which individuals have the freedom to revise, customize, and change materials for their own purpose. Ren argued that collaboration is an essential component of openness in OER creation and adoption, with the example of a large-scale open textbook project conducted in Latin America, which could not be accomplished without collaboration among the instructors and between the instructors and supporting organizations, who eventually developed collaborative learning mindsets and came to believe in the power of collaboration. Taking into account these arguments, we added another dimension, openness to collaboration, to the initial OTS and considered items from a collaborative learning scale in generating items for this dimension.

Promoting sharing

Closely related to the concept of collaboration, sharing is considered as another important feature of openness in OER and OEP (Conole, Citation2013; Edwards, Citation2015; Hegarty, Citation2015; Veletsianos, Citation2015). Edwards noted that openness in today’s networked learning environment may be seen in educational opportunities that open up wider access to education and overcome barriers to such access by supporting connected and collaborative learning, reducing the authoritative power of educational providers (both teachers and institutions) on learning, and promoting peer learning and coproduction and sharing of knowledge. Similarly, Conole and Hegarty saw the concept of sharing ideas and resources as one of the key attributes of open pedagogy and argued that the open process during OER creation and OEP promotes attitudes of sharing as well as collaborative content generation. In addition, Veletsianos identified sharing as a critical attribute of the open research process in which the sharing of data and research materials is practiced. In light of these studies, we added a dimension of openness to sharing to the initial OTS and pondered a scale of measuring attitudes toward sharing resources in generating items to measure this dimension.

Accepting changes

As discussed briefly above, several studies (Barker et al., Citation2018; Baron, Citation2019; Svedholm-Häkkinen & Lindeman, Citation2018) have extended the features of openness to include an attribute of accepting and seeking changes. Those who create and use OER tend to flexibly adapt their thinking (Barak & Levenberg, Citation2016) to revising, repurposing and thus making changes in OER to fit their contexts. Barker et al. claimed that the idea of openness embedded in OEP by using open textbooks reinforces participatory cultures by encouraging people to adopt and adapt new ideas and change their work. Nascimbeni and Burgos (Citation2019) and Tillinghast (Citation2021) noted that the use of OER is related to changes in the technology adoption behaviors of faculty members. In this regard, we added another important dimension, openness to change, to the initial OTS and considered several existing scales of flexibility, acceptance of change, and learning technology acceptance in creating items for the dimension.

Research questions

Among the varied and diverse benefits of OEP, open thinking is one of most crucial learning outcomes, central to the openness philosophy of OEP using OER. However, there exist conceptual and methodological barriers as open thinking is a complex and multifaceted concept. It is, in fact, a meta-construct that is drawn from diverse research used to explain changes in thinking among learners as a result of their participation in OEP. In this regard, the lack of conceptual clarity may have led to the absence of a reliable measurement instrument, which may prove fatal for OEP outcome research and practice improvement. The aim of this study, then, was to develop and validate a multidimensional OTS in order to measure adult learners’ open thinking as a key learning outcome of OEP. To this end, we examined the concept and underlying dimensions of open thinking. Thus, this study was guided by two research questions:

What are the definition and dimensions, constructs, and items of OTS as a learning outcome of OEP?

Is the developed OTS valid to be employed for OEP research and practices?

Method

We conducted, developed, and validated the scale from January to August 2020 in three phases, as suggested by Morgado et al. (Citation2017): (a) item generation, (b) theoretical analysis, and (c) psychometric analysis. The research procedure was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the International Christian University (#2019-43).

Phase 1: Item generation

We deductively generated items based on a literature review and preexisting scales. In this step, we devised an initial definition of open thinking: “an attribute of an individual person that includes, in its scope, a positive disposition toward new ideas or perspectives, new ways of learning, collaboration, change, and sharing as a learning outcome of OEP”. We determined the constructs and created potential items for each one. The initial version of the OTS contained 48 items drawn from these five constructs:

Openness to new perspectives: willingness in accepting and seeking new and changing ideas, content, and values and valuing multiple perspectives and multifaceted realities

Openness to different ways of learning: the desire for various learning opportunities, acceptance of multiple formats and different types of learning resources, beliefs in initiatives and self-directed learning

Openness to collaboration: belief in collaborative learning, peer learning, and coproduction of knowledge

Openness to sharing: willing attitude toward sharing learning resources and content, belief in open distribution

Openness to change: having the confidence and willingness to change, flexibility in adapting to new learning environments, acceptance of change, change-seeking tendencies.

Phase 2: Theoretical analysis

To ensure that the initial item pool properly measured the constructs and subconstructs, thereby obtaining the content validity of the OTS, we collected both quantitative and qualitative opinions from 14 multinational expert judges from nine countries (China, Germany, Japan, Philippines, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Turkey, & the United States of America)—all of whom have between 10 and 40 years’ experience in open and distance education research. Although the average work experience of the expert judges was 19.6 years, we tried to recruit expert judges with balanced work experience, age, gender, ethnicity, and current position so that sampling reflected the diversity of the population. Further, we conducted a pilot test involving seven multinational and multilingual individuals drawn from the target population. Using these two methods—expert review and pilot testing with potential respondents—has been recommended for theoretical analysis (Morgado et al., Citation2017).

In the quantitative questionnaire, we asked each of the 14 expert judges to rate the appropriateness of the definition and dimensions (constructs and subconstructs) of open thinking, as well as the OTS items, using a 4-point Likert scale (very improper, improper, proper, and very proper). Items with a rating of less than 3.0 were deleted, and other items with a small deviation of less than 3.1 were considered for deletion. For the qualitative part, we asked the expert judges to freely provide comments on all the components of the scale, including a definition of open thinking, construct composition, the validity of each construct and items, and overall opinion, which we thematically analyzed by the key constructs and used to refine the item statements during our weekly discussions.

The pilot test required gathering opinions from seven university students, seeking specific feedback on any confusing, complicated, uncomfortable, or inaccurate expressions to ensure that all items were clearly understandable and free of any inherent bias.

The revised version of the OTS consisting of six constructs and their subconstructs is shown in . In the revised version, we included one additional construct—openness to diversity and inclusion: valuing diversity and inclusion in educational contexts, belief in intercultural interactions and collaborations, belief in the learning capability of people with diverse backgrounds.

Table 1. Constructs, subconstructs, number of items, and measures.

This sixth dimension has five subconstructs and 12 items derived from the Miami University Diversity Awareness Scale (Mosley-Howard et al., Citation2011). Additionally, 19 existing items were rephrased, and three others dropped. Moreover, we revised the initial definition of open thinking to “an attribute of an individual person that includes in its scope a positive disposition toward new ideas or perspectives, new ways of learning, collaboration, sharing, change, and diversity and inclusion as a learning outcome of (open) educational practices.” presents the six constructs, subconstructs, and 57 items included in the revised OTS, which used a 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, and strongly disagree) for psychometric analysis.

Table 2. Revised constructs, subconstructs, and items.

Phase 3: Psychometric analysis

To assess construct validity and reliability of the revised scale, we conducted psychometric analyses using exploratory factor analysis (EFA), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and internal consistency calculation.

Employing an online survey system, data from 24 countries (Australia, Canada, China, Cyprus, Egypt, Germany, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Nepal, New Zealand, Philippines, South Africa, South Korea, Switzerland, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States of America, Vietnam, and 2 unspecified) were collected with the help of related academic communities balancing continent composition: 610 adult learners (18 years or older) responded, of whom 65.9% (n = 402) were female. A total of 17.5% were teens (18–19 years old) (n = 107); 56.2% were in their 20s (n = 343); 18.2% were in their 30s (n = 111); and the remaining 8% were over 40 years old.

The 610 responses were divided randomly into two sample sets, which yielded a similar composition of demographics (gender, age, academic year, and study field, and frequency of OER use). The first set, with 283 samples, was used for EFA to identify the factor structure of the OTS using IBM SPSS version 22, and after a preliminary data analysis and screening, based on a set of criteria, a principal component analysis, with direct oblimin rotation assuming correlation between factors, was conducted. The second sample set, with 327 responses, was subjected to CFA in order to verify whether the data fit well with the proposed factors of EFA with IBM SPSS AMOS version 22. The model path coefficients were estimated, using maximum likelihood estimation and the model fit was assessed using a set of fit indices. The convergent validity was verified by calculating the average variance extracted for each factor (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981) and the Cronbach coefficient α was employed in order to establish the internal consistencies of each subscale and of the whole scale to conduct reliability analysis.

Further, known-groups validity was examined to determine whether two distinct groups of OER who used frequency—a group of learners who responded “sometimes”, “rarely”, or “never” to reply to the question “How often do you use open educational resources (OER) for learning?” (n = 216) and a group who responded “very often” or “always” (n = 394)—could be measured by the scale, with an assumption that learners who use OER more frequently have higher OTS scores. A subsequent independent samples t test revealed group differences.

Results

Preliminary data analysis

Preliminarily analysis of data from the first set of 283 samples was conducted in conjunction with the examination both the descriptive statistics and the distributional properties of the items. The data was sifted employing four criteria: (1) items with outlier mean or standard deviation, (2) items with abnormal skewness and kurtosis, (3) items with less than 0.30 inter-item or item-total score correlation, and (4) items that hurt the internal consistency of each scale or whole scale. The results show that no items were excluded based on Criteria 1 or 2; 14 items were deleted due to Criteria 3 (4, 8, 12, 21, 23, 25, 44, 46, 50, 51, 54, 55, 56, and 57), while three items appeared to hurt the whole internal consistency (5, 6, 7), as did nine items for the internal consistency of the subscales (1, 2, 13, 14 for Construct 1; 20, 22, 26 for Construct 2; 31 for Construct 3; and 48 for Construct 6).

EFA

EFA on the 31 items was employed under six constructs. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure (KMO = 0.917) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (χ2 = 4300.4, df = 465, p = 0.000) confirmed the adequacy of the sample for factor analysis. The initial direct oblimin rotation yielded six factors with eigenvalues exceeding 1, which shows in a dramatic slope change of the scree plot at the seventh factor. Two criteria were applied to determine the elimination of items: the first for items with loadings of less than 0.40 in structure matrix or items with loadings of more than 0.40 with more than two factors in pattern matrix; and the second for items with communalities of less than 0.40. Four items (24, 27, 42, and 47) were deleted based on the first criteria, while there were no items with communalities of less than 0.40.

The final version of the scale retained 27 items under six constructs. The mean item level ranged from 3.51 to 4.41 and the standard deviation from 0.68 to 1.06. The six-factor solution was highly interpretable, and the cumulative explanation percentage of the variance was observed at 63.13%. The extracted factors were, on average, moderately intercorrelated (r = 0.282 ∼ 0.683, p < 0.001). The reliability of the whole scale with 27 items was 0.982; 0.725 (4 items), 0.796 (5 items), 0.769 (3 items), 0.860 (5 items), 0.844 (7 items), 0.782 (3 items) for each subscale. shows the refined items and factor loadings after EFA.

Table 3. Factor loadings of 27 items after direct oblimin rotation.

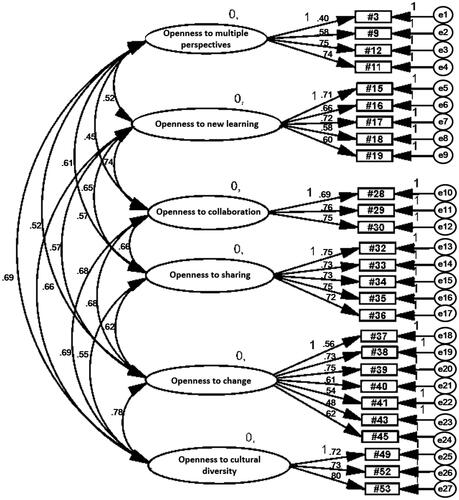

CFA

CFA with a cross-validation subsample (n = 327) was employed on the now 27 items, with 6 constructs, to assess the factorial validity of the final version of the OTS. The CFA results indicated that the six-factor model of the OTS fit the data well with very good to acceptable fit [χ2/df = 1.400; TLI = .962; CFI = .969; NFI = .902; RMSEA = .035 (CI = .027–.043); and SRMR = .047]. The measurement weight loading was all significant between 0.40 and 0.80 (see ). Inter-factor correlations were all below 0.85 (r = 0.45–0.78), indicating acceptable discriminant validity (Kline, Citation2005).

Known-groups validity test

An independent samples t test showed that higher frequency OER users (M = 4.11, SD = 0.45, n = 394) had significantly higher mean scores on the OTS than less frequent OER users (M = 3.85, SD = 0.52, n = 216) [t(608) = −6.68, p < 0.001] with a medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.53).

Discussion

This study aimed at developing and validating an OTS which measures open thinking as a key learning outcome of OEP in higher education. The results obtained supported the proposed conceptualization of open thinking as well as the content validity, construct validity, and reliability of the scale.

Findings from EFA successfully demonstrated a clear six-factor structure of open thinking, as was initially proposed, based on previous literature on openness in open education (e.g., Barak & Levenberg, Citation2016; Hegarty, Citation2015; Hug, Citation2017; Peter & Deimann, Citation2013) and related instruments (e.g., Barak & Levenberg, Citation2016; Ben-Itzhak et al., Citation2014; Mishra et al., Citation2016; Mosley-Howard et al., Citation2011; Schommer, Citation1990).

EFA reduced 57 items to 27 items, eliminating some subconstructs and items, especially in Factors 1, 2, and 6. In Factor 1, openness to new perspectives, of 14 initial items (see ), four items remained in the revised version; items closely related to the recognition of the existence of multiple perspectives and ideas that are not necessarily new or innovative. In view of this, Factor 1 was renamed openness to multiple perspectives. This factor may be promoted by empowering learners to be “knowledge producers or curators” (Baran & AlZoubi, Citation2020, p. 232; DeRosa & Robinson, Citation2017) rather than passive knowledge consumers in OEP, and by encouraging learners to question existing knowledge, explore different truths in reality and seek different meanings in various contexts. The factor, openness to multiple perspectives, can be considered as a critical element for creating connective knowledge via interactions with OER, developed by people who are distributed across a web of individuals (Jung, Citation2019, p. 50). To create connective knowledge, people need to understand and accept different views and features held by individuals in the networked open learning environment. In Factor 2, openness to different ways of learning, from the original 12 items, the five remaining were related to open attitude toward new learning, including both new content and methods. To highlight these features of newness, Factor 2 was renamed as openness to new learning. This factor can be promoted by opening up the learning process enabling learners to take the lead and fully engage in decision-making during their learning (Hegarty, Citation2015). In Factor 6, openness to diversity and inclusion, the original list of 12 items was reduced to three. These items are all related to an appreciation of cultural diversity and desire to learn and interact with different cultures. Considering the features of the remaining items, Factor 6 was renamed openness to cultural diversity. This factor highlights the importance of encouraging learners to engage in intercultural interactions during OEP, as noted in Mosley-Howard et al. (Citation2011). Surprisingly, nine items related to valuing the appreciation of diversity and addressing social justice and inclusion issues were deleted. It may be that open education itself does not help learners reach a particular level of understanding or value on diversity nor the inclusion of social justice and political agenda. Therefore, for certain classes, careful integration of diversity and inclusion of activities in the open learning process could help learners develop an openness to various diversity and inclusion issues beyond cultural diversity.

Factor 5, openness to change, accounted for the largest percentage of variances explaining open thinking at 34.7%: that is, Factor 5 was found to be the most centralized dimension of open thinking. One explanation for this is that OEP have brought about several changes in traditional educational practices, including changes in the roles and relationships of instructors and learners, the introduction of a wide range of sources and types of resources, and the valuing of social learning (Cronin, Citation2017; Sandanayake, Citation2019). And as learning is technology-based in OEP, successful learners are those who adjust quickly and proficiently to changing new learning tools and technologies (Beaudoin et al., Citation2013). Further, because OEP are becoming a primary agent of broader changes, such as technological and pedagogical changes in education, some have observed emerging changes in learner expectations and attitudes toward open learning and learner-centered approaches (e.g., Illowsky et al., Citation2016; Lane & McAndrew, Citation2010).

Findings from CFA support the utility of the OTS as a measure of open thinking, as a learning outcome of OEP in the context of higher education. The OTS accomplishes this aim by gauging college students’ perceptions on their openness to multiple perspectives, new learning, collaboration, sharing, change, and cultural diversity. Factors 1 and 6 are the philosophical dimensions of open thinking, which emphasize learners’ beliefs in multiple realities and diverse perspectives beyond their own cultural boundaries; a concept similar to being "conceptually open," as asserted by Worley (Citation2015). Factors 2 and 5 can be interpreted as dimensions that value the extended learning space, or learning ecology (Siemens, Citation2007), where learners see their learning environment as dynamic, adaptive, alive and evolving (Jackson, Citation2013). Factors 3 and 4 are the two dimensions of open thinking that recognize personal and pedagogical values of collaborative group learning, interactions, and resource sharing.

Known-groups validity tests showed that the more frequently a learner used OER, the higher OTS scores that learner obtained, a finding that strongly supports the argument that open thinking is a learning outcome of OEP which are supported with the use of OER. Although this finding needs to be confirmed in well-designed experiments, it shows the possibility of using OTS as a tool for both educators and learners to reflect on teaching and learning behaviors through the lens of open thinking attributes, and also as a tool for the development of competencies needed to prepare for teaching and learning in an open learning environment.

The OTS may help educators act in support of the open thinking development of their learners by structuring the open learning environment in such a way for learners to exercise open thinking attributes for their learning. For example, learners could develop an openness to multiple perspectives more readily if OER developed with different perspectives, instead of OER with similar perspectives, are introduced into teaching a certain content. It may also be used to measure the effectiveness of OEP in terms of the growth of open thinking in learners. That is, the OTS can be used to assess if OEP are promoting openness in learning and are learner-friendly, especially for those who have limited experiences in open learning environments. In addition, the measure may have the potential to provoke communication among OEP researchers since there has been “no agreed canon of OEP research that all researchers will be familiar with” (Weller et al., Citation2018, p. 121).

Despite this study being carried out in three systematic phases of scale development and validation, with balanced samples from diverse countries, the proposed factor structure of the OTS may require further evaluation across diverse contexts and with different target groups to obtain a broader perspective. Even though the overall discriminant validity was acceptable, not all inter-factor correlations had relevant size, suggesting that the six latent constructs may not be as clearly distinct from each other as supposed. This result may have its cause in wide-ranging values and the overlapping conceptual components of openness in OEP (Havemann, Citation2016; Weller et al., Citation2018). More empirical research using the OTS is needed to clarify the inter-factor correlations.

Conclusion

The results of this study support the original proposed conceptualization of the OTS and establish the scale’s content validity, construct validity and reliability. We hope that the scale will contribute to open education research by defining and elaborating on the concept of open thinking as a key learning outcome of open education. In addition, we hope that our findings of a relationship between OEP and open thinking will help enrich educators' ideas about open thinking, enabling them to better cultivate it in their students and in so doing obtain measurable learning outcomes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was declared by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Insung Jung

Insung Jung is a full professor of education at the International Christian University, Tokyo, Japan. Her research interests include quality assurance of open and distance education, culture in online learning, OER and MOOCs in higher education, and online learner competencies.

Jihyun Lee

Jihyun Lee is an associate professor with the School of Dentistry at the Seoul National University. Her research interests include dental and medical education, model development methodology, MOOC and OER, flipped learning, and technology integration for higher-order thinking.

References

- Afolabi, F. (2017). First year learning experiences of university undergraduates in the use of open educational resources in online learning. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(7). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i7.3167

- Ahn, J., Pellicone, A., & Butler, B. S. (2014). Open badges for education: What are the implications at the intersection of open systems and badging? Research in Learning Technology, 22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v22.23563

- Barak, M., & Levenberg, A. (2016). Flexible thinking in learning: An individual difference measure for learning in technology-enhanced environments. Computers & Education, 99, 39–52. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.04.003

- Baran, E., & AlZoubi, D. (2020). Affordances, challenges, and impact of open pedagogy: Examining students’ voices. Distance Education, 41(2), 230–244. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2020.1757409

- Barker, J., Jeffery, K., Jhangiani, R. S., & Veletsianos, G. (2018). Eight patterns of open textbook adoption in British Columbia. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 19(3). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v19i3.3723

- Baron, J. (2019). Actively open-minded thinking in politics. Cognition, 188, 8–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2018.10.004

- Beaudoin, M., Kurtz, G., Jung, I., Suzuki, K., & Grabowski, B. (2013). Online learner competencies: Knowledge, skills and attitudes for successful learning in online and blended settings. Information Age Publishing.

- Ben-Itzhak, S., Bluvstein, I., & Maor, M. (2014). The Psychological Flexibility Questionnaire (PFQ): Development, reliability and validity. Webmed Central Psychology, 5, 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.9754/journal.wmc.2014.004606

- Bonk, C. J. (2009). The world is open: How web technology is revolutionizing education. Jossey-Bass.

- Bonk, C. J., Lee, M. M., Reeves, T. C., & Reynolds, T. H. (Eds.). (2015). MOOCs and open education around the world. Routledge.

- Bozkurt, A., Koseoglu, S., & Singh, L. (2019). An analysis of peer reviewed publications on openness in education in half a century: Trends and patterns in the open hemisphere. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 35(4), 78–97. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.4252

- Chiorescu, M. (2017). Exploring open educational resources for college algebra. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(4). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i4.3003

- Colvard, N. B., Watson, C. E., & Park, H. (2018). The impact of open educational resources on various student success metrics. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 30(2), 262–276. https://www.isetl.org/ijtlhe/pdf/IJTLHE3386.pdf

- Commonwealth of Learning. (2000). An introduction to open and distance learning. http://oasis.col.org/bitstream/handle/11599/138/ODLIntro.pdf

- Conole, G. (2013). Designing for learning in an open world. Springer.

- Croft, B., & Brown, M. (2020). Inclusive open education: presumptions, principles, and practices. Distance Education, 41(2), 156–170. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2020.1757410

- Cronin, C. (2017). Openness and praxis: Exploring the use of open educational practices in higher education. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(5). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i5.3096

- DeRosa, R., & Robison S. (2017). From OER to open pedagogy: Harnessing the power of open. In R. Jhangiani & R. Biswas-Diener (Eds.), Open: The philosophy and practices that are revolutionizing education and science (pp. 115–124). Ubiquity Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5334/bbc.i

- DeVries, I. J. (2019). Open universities and open educational practices: A content analysis of open university websites. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 20(4). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v20i4.4215

- Di Fabio, A., & Gori, A. (2016). Developing a new instrument for assessing acceptance of change. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, Article 00802. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00802

- Dutta, I. (2016). Open educational resources (OER): Opportunities and challenges for Indian higher education. Turkish Journal of Distance Education, 17(2). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.34669

- Edwards, R. (2015). Knowledge infrastructures and the inscrutability of openness in education. Learning, Media and Technology, 40(3), 251–264. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2015.1006131

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3150980

- Gallardo, M., Heiser, S., & McLaughlin, X. A. (2017). Developing pedagogical expertise in modern language learning and specific learning difficulties through collaborative and open educational practices. The Language Learning Journal, 45(4), 518–529. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2015.1010447

- Grasha, A. F. (1996). Teaching with style: A practical guide to enhancing learning by understanding teaching and learning styles. Alliance Publishers.

- Guglielmino, L. M. (1978). Development of the self-directed learning readiness scale [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Georgia.

- Havemann, L. (2016). Open educational resources. In M. A. Peters (Ed.), Encyclopaedia of educational philosophy and theory. Springer. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-532-7_218-1

- Hegarty, B. (2015). Attributes of open pedagogy: A model for using open educational resources. Educational Technology, 55(4), 3–13. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44430383

- Hilton, J. (2016). Open educational resources and college textbook choices: A review of research on efficacy and perceptions. Educational Technology Research & Development, 64(1), 573–590. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-016-9434-9

- Hug, T. (2017). Openness in education: Claims, concepts, and perspectives for higher education. Seminar.Net, 13(2). https://journals.hioa.no/index.php/seminar/article/view/2308 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7577/seminar.2308

- Illowsky, B., Hilton, J., III, Whiting, J., & Ackerman, J. (2016). Examining student perception of an open statistics book. Open Praxis, 8(3), 265–276. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.8.3.304

- Jackson, N. J. (2013). The concept of learning ecologies. In N. J. Jackson & G. B. Cooper (Eds.), Lifewide learning, education and personal development. Lifewide Education. http://www.lifewideebook.co.uk/conceptual.html

- Jung, I. (2019). Connectivism and networked learning. In I. Jung (Ed.), Open and distance theory revisited: Implications for the digital era (pp. 47–56). Springer. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-7740-2_6

- Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modelling (2nd ed.). Guilford.

- Koseoglu, S., Bozkurt, A., & Havemann, L. (2020). Critical questions for open educational practices. Distance Education, 41(2), 153–155. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2020.1775341

- Lane, A., & McAndrew, P. (2010). Are open educational resources systematic or systemic change agents for teaching practice? British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(6), 952–962. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2010.01119.x

- Lewis, R. (1986). What is open learning? The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 1(2), 5–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0268051860010202

- Lin, H. (2019). Teaching and learning without a textbook: Undergraduate student perceptions of open educational resources. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 20(3). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v20i4.4224

- Mishra, S., Sharma, M., Sharma, R. C., Singh, A., & Thakur, A. (2016). Development of a scale to measure faculty attitude towards open educational resources. Open Praxis, 8(1), 55–69.

- Morgado, F. F. R., Meireles, J. F. F., Neves, C. M., Amaral, A. C. S., & Ferreira, M. E. C. (2017). Scale development: Ten main limitations and recommendations to improve future research practices. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 30(3), 1–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s41155-016-0057-1

- Mosley-Howard, G. S., Witte, R., & Wang, A. (2011). Development and validation of the Miami University Diversity Awareness Scale (MUDAS). Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 4(2), 65–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021505

- Nascimbeni, F., & Burgos, D. (2019). Unveiling the relationship between the use of open educational resources and the adoption of open teaching practices in higher education. Sustainability, MDPI, Open Access Journal, 11(20), 1–11. https://ideas.repec.org/a/gam/jsusta/v11y2019i20p5637-d275931.html https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205637

- Pawlyshyn, N., Braddlee, B., Casper, L., & Miller, H. (2013). Adopting OER: A case study of cross-institutional collaboration and innovation. Educause Review. http://er.educause.edu/articles/2013/11/adopting-oer-a-case-study-of-crossinstitutional-collaboration-and-innovation

- Peter, S., & Deimann, M. (2013). On the role of openness in education: A historical reconstruction. Open Praxis, 5(1), 7–14.

- Rahayu, U., & Sapriati, A. (2018). Open educational resources based online tutorial model for developing critical thinking of higher distance education students. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 19(4), 163–175. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.471914

- Ren, X. (2019). The undefined figure: Instructional designers in the open educational resource (OER) movement in higher education. Education and Information Technologies, 24, 3483–3500. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-019-09940-0

- Sandanayake, T. C. (2019). Promoting open educational resources-based blended learning. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 16(3). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-019-0133-6

- Schommer, M. (1990). Effects of beliefs about the nature of knowledge on comprehension. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(3), 498–504. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.82.3.498

- Siemens, G. (2007). Connectivism: Creating a learning ecology in distributed environments. In T. Hug (Ed.), Didactics of micro-learning: Concepts, discourses and examples (pp. 53–68). Waxman.

- Svedholm-Häkkinen, A. M., & Lindeman, M. (2018). Actively open-minded thinking: Development of a shortened scale and disentangling attitudes towards knowledge and people. Thinking & Reasoning, 24(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13546783.2017.1378723

- Tillinghast. B. (2021). Using a technology acceptance model to analyze faculty adoption and application of open educational resources. International Journal of Open Educational Resources, 4(1). https://www.ijoer.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Using-a-Technology-Acceptance-Model-to-Analyze-Faculty-Adoption-and-Application-of-Open-Educational-Resources.pdf

- Tseng, H., Kuo, Y.-C., & Walsh, E. J., Jr.(2020). Exploring first-time online undergraduate and graduate students’ growth mindsets and flexible thinking and their relations to online learning engagement. Educational Technology Research & Development, 68(5), 2285–2303. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09774-5

- UNESCO. (2014). How openness impacts on higher education (Policy brief). http://iite.unesco.org/pics/publications/en/files/3214734.pdf

- UNESCO. (2019). Guidelines on the development of open educational resources policies. https://www.unesco.de/sites/default/files/2020-01/Guidelines_on_the_Development_of_OER_Policies_2019.pdf

- Veletsianos, G. (2015). A case study of scholars’ open and sharing practices. Open Praxis, 7(3), 199–209. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.7.3.206

- Weller, M., Jordan, K., DeVries, I., & Rolfe, V. (2018). Mapping the open education landscape: Citation network analysis of historical open and distance education research. Open Praxis, 10(2), 109–126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.10.2.822

- Worley, P. (2015). Open thinking, closed questioning: Two kinds of open and closed question. Journal of Philosophy in Schools 2(2), 17–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.21913/JPS.v2i2.1269