Abstract

Feedback is a complex socio-cultural construct, utilising various modalities over the lifespan of a research candidature. This study reports findings from a review of global literature on supervisory feedback to postgraduate research students. Three focus questions guided the review: students’ problems in receiving feedback, perceptions of positive feedback strategies, and potential improvements to the feedback process. The review method combined a systematic search process with explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria applied to literature published over the last decade. A detailed content analysis of 43 articles is reported in a thematically ordered narrative. Findings suggested that problems with feedback were found to be caused by the content, processes involved and the expectations of those involved. Second, feedback strategies that positively impacted learning and teaching capabilities of both students and supervisors were identified as most effective. Third, improvements to the feedback process were canvassed through the three key actors of institutions, supervisors and students, providing insights into the synergistic relationship among these actors. Further research is warranted as feedback processes and products are at the mercy of research supervision, which is increasingly operating in online environments spanning different time zones, with professional, cultural and linguistic diversities impacting feedback processes and products.

Introduction

Providing effective feedback to postgraduate research students is often a challenge for supervisors. Poor feedback leads to a negative supervisory experience for postgraduate research students (Cekiso et al. Citation2019). Unfortunately, inadequate, untimely and unconstructive non-critical feedback to postgraduate research students emerged as a common problem in many studies (Engebretson et al. Citation2008; Lindsay Citation2015; Soumana and Uddin Citation2017). To enhance the learning process, an examination of feedback practices is warranted, particularly so that research supervisors have a better insight into what works and what does not.

Feedback is important at every educational level, and there can be differences in the style and type of feedback provided. Timely, supportive and high-quality feedback is critical for facilitating and supporting doctoral students (Deshpande Citation2017). There are different types of feedback, such as verbal, written, formal, informal, evaluative, descriptive and self-assessed (NSW Government Citation2020). The channel through which feedback is offered could be physical or digital. From a student perspective, feedback is a way of gauging knowledge, skills and understanding to determine their own result (Scott Citation2014). Good feedback practice includes the development of self-reflection, encourages dialogue, clarifies goals, closes the gap between current and desired performance, delivers good quality feedback, offers motivation and provides information to teachers (Juwah et al. Citation2004). Ultimately, feedback should be a two-way process between the assessor and the student to enhance learning. Studies in Australia, Malaysia, the Netherlands and the United States found that supervisor feedback is an important dimension influencing student satisfaction and research students value good-quality feedback (Zhao, Golde, and McCormick Citation2007; Engebretson et al. Citation2008; Mustafa, Noraziah, and Majid Citation2014; Woolderink et al. Citation2015).

Ineffective feedback can create tension in the supervisor-student relationship and impede learning and achievement (East, Bitchener, and Basturkmen Citation2012). Providing feedback to postgraduate research students is a complex issue, with many variables to consider, including the candidate; stage of candidature; type of candidature (part-time, full-time; domestic, international; on-shore, off-shore); course enrolment (Master, PhD, EdD, other Professional PhDs); supervisory position (principal or associate); supervisory team (number, disciplinary mix, relationship/s among the team); and mandatory and optional research tasks. However, as expected in any educational endeavour, it is critical that feedback is learner-centred, focuses on improvements and is actionable.

Our quest for the topic revealed previous reviews (Engebretson et al. Citation2008; McCallin and Nayar Citation2012; Nasiri and Mafakheri Citation2015) on postgraduate research supervision. These reviews did not reveal how the literature was shortlisted nor specifically focus on supervisory feedback. To the best of our knowledge, there appear to be no literature reviews that specifically look at the dimension of supervisory feedback to postgraduate research students. To fill this gap, a qualitative review of global literature was conducted that explored three specific research questions:

RQ 1: What are the problems students encounter in feedback from supervisors?

RQ 2: What are the positive feedback strategies used by supervisors?

RQ 3: What can be done to improve the feedback process?

Hence, this study aims to enrich our understanding of supervisory feedback strategies to inform and improve practice.

Research method and results

This study adopts a narrative style of analysing the extant literature, which typically involves summarising or synthesising information (Green, Johnson, and Adams Citation2006) to provide practitioners up-to-date comprehensive background on a particular topic and further their understanding of the research area (Paré and Kitsiou Citation2016). Narrative literature reviewing is also regarded as an invaluable theory-building technique (Baumeister and Leary Citation1997). To add rigour to the narrative review, the method of identifying and selecting literature as undertaken in a systematic literature review was interweaved with the narrative approach. A systematic review ensured the selection process was explicit, reproducible and met pre-defined eligibility criteria (Higgins et al. Citation2019). Consequently, conducting the review involved searching and identifying the literature, screening for exclusion, assessing eligibility, and extracting the data and analysis (Templier and Paré Citation2015).

In September 2020, a systematic search for the literature was carried out on six online databases [Scopus (Elsevier); ProQuest Central; Education Collection; Social Sciences Citation Index (Web of Science); OneFile (Gale); and ERIC] to identify relevant studies. The database search was conducted through the researchers’ institution’s online library.

The search was limited to peer-reviewed journal articles only, published in the English language. Articles published from 2010 to 2020 were included, enabling us to capture various insights and maintain currency. Studies that dealt with anything to do with feedback to postgraduate research students were included. The perspectives of feedback in the shortlisted papers could be from either students’ or supervisors’ point of view. The articles were reviewed using the inclusion and exclusion criteria, as shown in .

Table 1. Inclusion/exclusion criteria for the selection of articles.

Keywords (and their synonyms) used in the search were: postgraduate, research, feedback, supervisor and student. Boolean operators (and, or, not) were employed to assist in searching for relevant articles. Wildcards and truncation symbols were used to instruct the online databases to search for all forms of the keywords.

The initial search yielded 361 articles. The articles were screened for eligibility by reading their title and abstract. Articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were removed. If difficulty in assessment was encountered, a full-text screening of the articles was conducted. Duplicate articles were also weeded out. A final screening was carried out to ensure the articles addressed some component of feedback to postgraduate research students. This led to 43 articles that were used to inform this review.

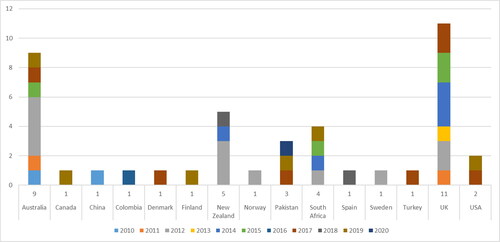

The shortlisted literature about postgraduate research supervision emerged from 15 countries, based on the first author’s institutional affiliation. The United Kingdom is leading the way in consistently producing postgraduate research supervision publications over the last decade (see ). However, the world’s two most populous countries have not been producing research studies in this area, with only one paper emanating from China ten years ago and none from India. This could encourage further research in the postgraduate supervision area from those two countries.

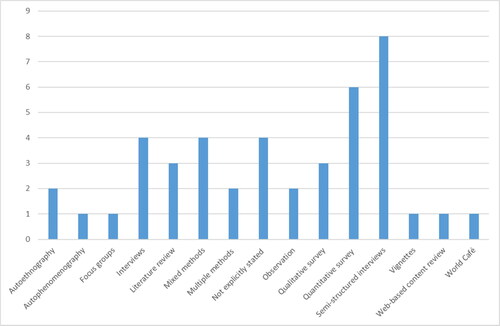

As illustrated in , the included studies used a variety of methods for data collection. Semi-structured interviews, followed by quantitative surveys, were popular research methods in postgraduate research supervision studies. Four studies did not explicitly mention the adopted research method.

The findings are outlined and discussed in the following sections. Before doing so, however, it is important to highlight that most of the papers refer to the supervision style or relationship, instead of the feedback process. Most of the reviewed articles consider feedback as embedded within the relationship, and as such much of the content implies, rather than specifies, relevance to feedback. This clearly shows a scarcity of research that explicitly and specifically focuses on the feedback process. As such, many of the problems, positive feedback strategies and improvement suggestions apply to the supervision relationship and the feedback process embedded in the relationship.

Problems in feedback

The review of the shortlisted literature identified five main problems that students encounter in feedback from their supervisors – these are problems deriving from:

the feedback content (i.e. what feedback is given);

how feedback is given;

the student;

the supervisor; and

divergent expectations.

Problems deriving from the feedback content

Many authors describe problematic feedback as vague, generic, non-specific and unclear (Ding and Devine Citation2018; Ali, Ullah, and Sanauddin Citation2019), which may be a result of the supervisor not (fully) reading the student’s work (Evans and Stevenson Citation2011). Examples of such confusing feedback are the use of question marks and non-directive comments like ‘rewrite this’ (East, Bitchener, and Basturkmen Citation2012; Soumana and Uddin Citation2017), which does not specify how to improve (Basturkmen, East, and Bitchener Citation2014). Such feedback may result in students not understanding or misinterpreting the comments (Baseer et al. Citation2020). This issue is exacerbated for students whose first language is not English, and students from cultural backgrounds where questioning the supervisor (a perceived authority figure) is not common (Basturkmen, East, and Bitchener Citation2014; Soumana and Uddin Citation2017). Language barriers are even higher if supervisors also use English as a second language (Schulze Citation2012).

Some articles discuss the difference between ‘pretty remarks’ (comments on writing style, punctuation, grammar and language) and the arguably more important ‘big picture’ feedback (overall comments on content and organisation) – feedback, which does not include ‘big picture’ comments, is problematic as these comments are crucial for the development of the project (East, Bitchener, and Basturkmen Citation2012; Lindsay Citation2015; Ali, Ullah, and Sanauddin Citation2019). In addition to feedback on performance, students also expect supervisors to provide emotional and moral encouragement (Leong Citation2010).

Olmos-López and Sunderland (Citation2017) show that students can become overwhelmed by the amount of feedback, especially in the case of co-supervision; however, students with only one supervisor may lose out on valuable feedback. Herrmann and Wichmann-Hansen (Citation2017) explain that too much feedback may reduce the student’s ownership of the project, for instance, if students simply accept all comments, thus developing an over-reliance on supervisor input (Nasiri and Mafakheri Citation2015). Feedback is also problematic if supervisors are overly controlling of the project, which may even lead to academic bullying (Yarwood-Ross and Haigh Citation2014), forcing students into directions that they do not wish to go to (Schulze Citation2012), and ‘over-supervision’ where the work ends up being mostly the supervisor’s (Grant, Hackney, and Edgar Citation2014). Ward (Citation2013) refers to this as guidance versus prescription, while Schulze (Citation2012) uses the terms directive and non-directive.

Problems deriving from the way in which the feedback is given

Most articles discuss the options of written and verbal feedback (e.g. Ali, Ullah, and Sanauddin Citation2019), although the potential problems with both of these are not well explored, beyond that written feedback may sound harsher than intended (Maor and Currie Citation2017). Almost all articles assume written feedback to be given electronically, e.g. via the use of track changes (Leggat and Martinez Citation2010; Odena and Burgess Citation2017), with only one article (White and Coetzee Citation2014) referring to hard copy written feedback, which is considered inferior to electronic feedback due to its time-consuming nature, potential reliance on the postal service, and illegibility of hand-written comments. On the other hand, Nasiri and Mafakheri (Citation2015) argue that a lack of digital skills of students and/or supervisors can cause problems.

A key problem in how feedback is given refers to the timeliness of the feedback: most of the shortlisted papers discuss the importance of timely responses to student queries, thus implying that untimely feedback is problematic (Schulze Citation2012). Leggat and Martinez (Citation2010) suggest that technology enables the provision of rapid feedback, typically within one week. Yarwood-Ross and Haigh (Citation2014) outline an even worse situation when supervisors deliberately choose to withhold feedback.

A further key problem is the tone of feedback: some supervisors are too harsh (or even cruel), and may give criticism without suggestions (Doloriert, Sambrook, and Stewart Citation2012; Zeegers and Barron Citation2012) - this can affect students’ confidence and motivation (Odena and Burgess Citation2017; Soumana and Uddin Citation2017) and exacerbate negative behaviours like procrastination or perfectionism (Siltanen et al. Citation2019). Other supervisors are ‘too nice’ and do not provide critical comments, even when necessary, which masks problems in the project (Kiley Citation2019).

Most authors refer to a lack of accessibility of supervisors and infrequent supervision meetings, irrespective of whether these are face-to-face or online (Ezebilo Citation2012; Hemer Citation2012; Soumana and Uddin Citation2017). This may be due to the supervisor’s workload or their lack of interest in the student’s project. The supervisory style and the student-supervisor relationship more broadly have a significant impact on the feedback process: trust, in particular, is a critical component of the relationship, and the literature implies that a lack of trust between student and supervisor can generate problems for students in receiving and accepting feedback (Yarwood-Ross and Haigh Citation2014).

Inconsistent and conflicting feedback is also problematic (Kiley Citation2019). This issue is common in the case of co-supervision (Grossman and Crowther Citation2015; Olmos-López and Sunderland Citation2017), and it may be exacerbated if supervisors come from different backgrounds, as Morris, Pitt, and Manathunga’s (Citation2012) article about supervision teams consisting of academics and industry professionals shows.

Problems deriving from the student

The supervision relationship is a two-way process (Heyns et al. Citation2019), but some students do not proactively seek feedback when needed (Soumana and Uddin Citation2017). In addition, students from cultures where the supervisor is considered a figure of authority may also struggle with feedback as they can be overly dependent on the supervisor (Soumana and Uddin Citation2017) or are unable to question unclear feedback (Yarwood-Ross and Haigh Citation2014).

Focusing on research students who start their research journey after successful careers elsewhere, Feather and McDermott (Citation2014) argue that such experts have brittle personalities and take feedback personally, often becoming defensive or non-responsive. Wang and Li (Citation2011) show that students’ attitudes towards writing and their level of self-esteem affect their emotional reactions to feedback: students with low self-esteem tend to interpret positively intended feedback as negative, and students who consider revising their own writing as a dynamic and iterative process are more likely to be inspired and confident even in the face of criticism.

Problems deriving from the supervisor

Supervisors often do not have the relevant subject knowledge to supervise certain projects (Soumana and Uddin Citation2017), and/or are not keenly interested in the project (Kiley Citation2019), which negatively affects their ability and willingness to provide feedback. Many supervisors also do not have the necessary skills to supervise – this is not limited to the skill of feedback-giving, but also refers to other skills such as relationship-building (Soumana and Uddin Citation2017) and emotional support (Schulze Citation2012).

Hemer (Citation2012) and Cree (Citation2012) argue that supervisors can become overwhelmed with their roles and relationships with students, which may be exacerbated by workload: excessive busyness and over-acceptance of students (including research higher degree students) into universities means that supervisors’ workload often does not allow for extensive feedback (McCallin and Nayar Citation2012; Roumell and Bolliger Citation2017; Siltanen et al. Citation2019).

One way to spread the workload is co-supervision, but this approach adds additional layers of complexity to the supervision process, deriving from political and power plays, fragmented responsibilities, and the previously mentioned conflicting feedback, all of which can generate problems for students (Manathunga Citation2012; Olmos-López and Sunderland Citation2017).

Problems deriving from divergent expectations

Divergent expectations between students and supervisors in terms of feedback (and the relationship more widely) are mentioned regularly in the literature – these may be exacerbated if students study by distance (Roumell and Bolliger Citation2017), or in the case of international students who come from different cultural, linguistic and educational backgrounds (Odena and Burgess Citation2017). This expectation mismatch results in confusion on what constitutes effective feedback, the purpose of feedback, the role of the supervisor and the supervisor’s availability, especially in times of technologically-enabled communication and opportunities for instantaneous and 24/7 availability (Andrew Citation2012; Orellana et al. Citation2016; Baseer, Mahboob, and Degnan Citation2017; Maor and Currie Citation2017).

Many (especially international) students see their supervisor as a directive support person, while many supervisors see their students as independent and self-sufficient individuals (Yarwood-Ross and Haigh Citation2014). The latter may result in a supervision (and thus feedback) style that represents benign neglect as supervisors attempt to train their students to be independent (Schulze Citation2012).

All students and supervisors are different with unique relationships and have differing needs and expectations (Cree Citation2012; Schulze Citation2012). Much literature also argues that the students’ need for and attitude towards feedback changes over the course of their candidature (e.g. East, Bitchener, and Basturkmen Citation2012). This means that problems do not affect all students equally. Therefore, the provision of feedback is a balancing act for the supervisor (Cree Citation2012), but the literature offers a wide variety of positive feedback strategies to support supervisors.

Positive feedback strategies

All students are unique (Schulze Citation2012), and the supervisory relationship as well as the embedded feedback changes throughout the candidature (East, Bitchener, and Basturkmen Citation2012). Thus, when exploring the myriad of strategies reviewed below, it is important to remember that there is not one feedback strategy that works positively for all situations. Instead, the literature argues that supervisors must be flexible and adapt their approaches, including their feedback, to the specific needs and requirements of the situation (McCallin and Nayar Citation2012; Grossman and Crowther Citation2015; Orellana et al. Citation2016). The reviewed literature highlights the following five positive feedback strategies:

manage expectations and negotiate supervision arrangements;

build and maintain a positive supervisory relationship;

awareness of and critical reflection on own practice;

suitable feedback content; and

suitable and balanced ways of giving feedback.

Manage expectations and negotiate supervision arrangements

To avoid diverging or unrealistic feedback expectations, a positive strategy for supervisors is to carefully manage expectations before giving feedback (Siltanen et al. Citation2019). This involves negotiating supervision arrangements, including time frames for submissions and feedback (Nasiri and Mafakheri Citation2015), as well as the setting of boundaries, so students do not expect unrealistically speedy or excessive feedback (Maor and Currie Citation2017). As part of these negotiations, students should be exposed to strategies of how to manage their supervisor(s) (Siltanen et al. Citation2019) while also becoming aware that they need to be open to feedback, including criticism (Nethsinghe and Southcott Citation2015). It is a good strategy for supervisors to view the relationship as a community of shared responsibility, in which student and supervisor(s) willingly learn from one another and in which both parties understand that the supervision is a two-way street (Heyns et al. Citation2019; Lim et al. Citation2019). In the case of international students, supervisors should acculturate together with their students (Ding and Devine Citation2018).

Build and maintain a positive supervisory relationship

Much of the reviewed literature refers to the supervisory relationship as a whole, rather than specifically singling out the feedback embedded within – this implies what East, Bitchener, and Basturkmen (Citation2012) state explicitly: feedback is only effective if the relationship is effective. Thus, it is obvious that a positive feedback strategy is for supervisors to build and maintain a positive relationship with their student(s). This involves the development of mutual trust and respect, built on open communication, humour, enthusiastic demonstration of interest in the project and the student as a person, as well as listening to students and seeking confirmation that students understand the feedback provided (Baseer, Mahboob, and Degnan Citation2017; Odena and Burgess Citation2017; Kiley Citation2019; Lim et al. Citation2019).

A further strategy is to be available, for instance, with virtual office hours (Nasiri and Mafakheri Citation2015). Availability is also shown through a commitment to pre-arranged meetings, which may take place in the ‘supervisor’s territory’ (e.g. their office) or in a neutral environment (e.g. a café) – the latter works for some students as they feel less intimidated, but others consider the feedback given in such location as less serious (Hemer Citation2012).

Awareness of and critical reflection on own practice

Irrespective of whether feedback is given during synchronous meetings or asynchronously, a key strategy is for supervisors to be aware of the effect that their feedback can have on students (Ali, Ullah, and Sanauddin Citation2019), and that receiving feedback can be a highly emotional process (Wang and Li Citation2011). Grossman and Crowther (Citation2015) emphasise that supervisors often base their supervisory style and approaches on their own experience of being supervised; this, however, may not be suitable for their students, and thus requires the supervisors to be aware of this behaviour and to critically reflect upon the best approaches for any given situation.

Suitable feedback content

Different students have different preferences in terms of desired feedback content (East, Bitchener, and Basturkmen Citation2012). Odena and Burgess (Citation2017), in highlighting that student needs change throughout candidature, argue that they often need more detailed feedback at the start of their research journey, while being able to deal with brief suggestions towards the end. East, Bitchener, and Basturkmen (Citation2012) establish that some students, irrespective of whether English is their first language, prefer indirect prompting, while others prefer direct feedback or supervisors to change words and correct grammar. Overall, the authors argue that a good strategy is to balance feedback on language and feedback on the organisation of the writing.

Odena and Burgess (Citation2017) stress the importance of accessible language, and Basturkmen, East, and Bitchener (Citation2014) highlight that complex comments on content need to be well-worded and thought through, rather than spontaneously put on paper while reading the draft. It is important to give feedback on drafts and work-in-progress, not just on finalised pieces of work, and feedback must highlight students’ strengths and weaknesses and help them improve their writing – this can be done through a combination of correcting, revising and editing, as well as more overall comments and collaborative discussions (Baseer, Mahboob, and Degnan Citation2017; González-Ocampo and Castelló Citation2018).

Suitable and balanced ways of giving feedback

The reviewed literature describes effective feedback as suggestive and constructive, brief, frequent and regular, actionable, specific and tailored, explicit, honest but empathetic and tactful, formal, supportive and encouraging, advising, appreciative and respectful but critical (Odena and Burgess Citation2017; Soumana and Uddin Citation2017; Ding and Devine Citation2018; Ali, Ullah, and Sanauddin Citation2019; Heyns et al. Citation2019; Kiley Citation2019; Lim et al. Citation2019; Lonka et al. Citation2019). In the case of co-supervision, feedback also needs to be non-conflicting – the strategy is to either get on the same page with the co-supervisor(s) before any feedback is given (Kiley Citation2019), or to arrange joint meetings with the entire team (Olmos-López and Sunderland Citation2017). While the literature suggests that feedback arising from co-supervision should be non-conflicting, one of the strengths of co-supervision is that it can enable students to handle conflicting opinions, which are typical in academe.

Many authors refer to the supervisor as a ‘critical friend’ who needs to be supportive but give directive and critical feedback where needed, especially if the student is going off-track (Roumell and Bolliger Citation2017). Basturkmen, East, and Bitchener (Citation2014) state that criticism, which can evoke negative emotions and reactions from students, can be softened if presented in an indirect manner, e.g. by phrasing a question; however, it is again important to adapt to the relevant situation because indirect feedback may be too vague for many students (Ali, Ullah, and Sanauddin Citation2019). Diverse supervision teams allow for stern and supportive feedback to be provided at the same time through different supervisors (Odena and Burgess Citation2017).

It is a good strategy to provide feedback on the same document multiple times (Nethsinghe and Southcott Citation2015) and ensure that it is timely (Lim et al. Citation2019). Nethsinghe and Southcott (Citation2015) recommend a variety of approaches, including modelling (the supervisor makes changes to drafts while explaining those) and scaffolding (the supervisor works with the student to accomplish a task). Ding and Devine (Citation2018), while underlining that there is no right way for every student, refer to structured, semi-structured and unstructured supervision; each has their own strengths and weaknesses, and individual students have their own preferences for these.

Positive feedback strategies also include the use of technology, e.g. track changes (Lim et al. Citation2019), or videoconferencing, messaging and email – a combination of synchronous and asynchronous feedback is recommended (Maor and Currie Citation2017; Roumell and Bolliger Citation2017). Nasiri and Mafakheri (Citation2015) suggest text bubbles rather than track changes to reduce the likelihood that students just accept them. The format of feedback again requires adaptation as it depends on what is required, e.g. short quick responses to brief questions, track changes for drafts, and recorded monologues for extensive opinion feedback (Nasiri and Mafakheri Citation2015).

Written feedback and time to digest it are important, as are opportunities to clarify and discuss (Ali, Ullah, and Sanauddin Citation2019), thus suggesting that an important strategy is to offer a combination of written and verbal feedback during regular meetings (White and Coetzee Citation2014; González-Ocampo and Castelló Citation2018). Grant, Hackney, and Edgar (Citation2014) recommend writing a log at the end of each feedback meeting, while Lonka et al. (Citation2019) suggest co-authoring with the student, so they can learn from the supervisor and integrate into the academic community. The latter can also happen by supervisors organising peer feedback sessions for students (Lindsay Citation2015; Siltanen et al. Citation2019), which also helps students become increasingly independent (González-Ocampo and Castelló Citation2018; Lim et al. Citation2019).

Overall, the literature shows that the key strategy for positive feedback is for supervisors to be flexible and adaptable (Orellana et al. Citation2016; Baseer, Mahboob, and Degnan Citation2017), and to use a balance or blend of different feedback styles, instead of attempting to standardise supervision (Feather and McDermott Citation2014; Grant, Hackney, and Edgar Citation2014; Lindsay Citation2015; Nasiri and Mafakheri Citation2015).

Improving the feedback process

The reviewed literature suggests that the following three actors can improve elements of the feedback process and the research supervision journey (Severinsson Citation2012):

institutions;

supervisors; and

students.

Institutions

Institutions need to consider providing administrative support for supervisors and students to de-bureaucratise various processes (Ward Citation2013; Kiley Citation2019; Siltanen et al. Citation2019). Institutions can ensure the appointment of appropriate supervisors (Schulze Citation2012), allocation of appropriate workloads (Soumana and Uddin Citation2017), and effective management of supervisor performance (Kiley Citation2019). In the case of distance supervisors, institutions could support occasional face-to-face meetings between students and supervisors (Roumell and Bolliger Citation2017).

Institutions also need to offer training and personal development opportunities for supervisors and students. For students, this should include research training (Siltanen et al. Citation2019) and language training for international students (Evans and Stevenson Citation2011). For supervisors, mentoring programs are mentioned (Heyns et al. Citation2019), while training could focus on supervision skills (Baseer et al. Citation2020), emotional support (Siltanen et al. Citation2019), and cross-cultural awareness and communication (Evans and Stevenson Citation2011).

Supervisors

Supervisors need to be willing to attend available training (Baseer et al. Citation2020) and reflect on their own experiences and behaviours (Grossman and Crowther Citation2015; Siltanen et al. Citation2019). Kiley (Citation2019) suggests reading material to complement training, while Baseer et al. (Citation2020) recommend that supervisors keep records of feedback. Supervisors and students could discuss and negotiate expectations at the start of their relationship and ensure regular ongoing communications and interactions throughout the process (Lim et al. Citation2019). In co-supervisory relationships, expectation management and allocation of tasks extend to the supervisory team (Grossman and Crowther Citation2015).

Supervisors could also seek input from their students, for instance, by asking whether certain feedback is useful (Lim et al. Citation2019), and seek support from colleagues, for example, in the form of supervision communities (Maor and Currie Citation2017). Supervisors need to make themselves available (Ezebilo Citation2012) and ensure constructive and timely feedback is provided. In the preceding section, positive feedback strategies were outlined, which could be used, e.g. regular meetings, a balance between written and verbal, synchronous and asynchronous feedback, and so forth.

Each supervisory relationship is unique and requires a careful balance of different feedback approaches – supervisors need to be aware of this balance (Odena and Burgess Citation2017; Lim et al. Citation2019) and of the relationship changing over time, which may require renegotiation of expectations. Moreover, supervisors should have cultural awareness if supervising international students so they can provide feedback in culturally sensitive manners (Wang and Li Citation2011).

Given the importance of the overall relationship for effective feedback, staff and students could seek to build a trust-based two-way relationship (Heyns et al. Citation2019), which consists of more than feedback as it also involves the pastoral and emotional side of doing a research higher degree (Roumell and Bolliger Citation2017).

Students

Students need to develop reflective skills and practice to understand their own attitudes, emotions and behaviours, as these affect their readiness to accept feedback (Lonka et al. Citation2019). However, the onus for developing reflective skills cannot be left to the students alone. Professional mentoring programs in which students receive constructive feedback from mentors can help supervisees understand the importance of feedback and enhance their sense-making (Siltanen et al. Citation2019). Furthermore, doctoral students can also benefit from establishing formal and informal social networks that function as a sounding board to clarify and interpret advice from their supervisors and provide further feedback (Lim et al. Citation2019). To this effect, supervisors can assist students in developing formal collaborative networks comprising other advisors, peers and alumni.

Conclusion

This analysis of literature over the past decade in the field of feedback in postgraduate research supervision has identified feedback to be unique to the people involved, their expectations and stage of candidature. Four key problems were identified when giving and receiving feedback: content, process, people, expectations. The nature and amount of content can be problematical, as well as the processes through which it is generated and disseminated. Sometimes, mismatched expectations of students and supervisors together with shifting roles throughout the candidature period were found to impact the feedback process negatively.

Managing expectations before providing feedback was found to be a significant positive strategy. Throughout the life of a candidature, these expectations can be revisited regularly with a clear articulation of shifting expectations among supervisor and student as a research project develops. Further, well-managed feedback contributes to a positive professional supervisory relationship and vice versa. Acknowledging the emotional toll that giving and receiving feedback exerts can also be a positive strategy when shared through deliberate, focused critical reflection between supervisor/s and student. Constantly reviewing the range and balance of feedback content provided in consultation with the student was also a positive strategy identified in the literature.

Three key actors contributed to the success or otherwise of the feedback process: institutions, supervisors and, of course, students. Institutional technical and financial support is essential for all feedback to stand a chance of being effective. If the information technology systems are not of a high standard, then feedback is already impaired. Financial assistance to facilitate feedback, especially when impacted by geographic distance and individual personal financial situations may need support to facilitate engagement with feedback. Supervisors’ role in the feedback process is fundamental to its efficacy, requiring a range and balance of these strategies. However, conscious mobilisation of the student as a key actor in feedback was also found to be important. Here the student is positioned as an active participant, developing agency in their own capabilities to engage critically with feedback as integral to the learning-teaching process. In other words, the student is not a passive recipient of feedback as transmission, but rather a reflexive researcher-to-be learning both with and through the supervisor. Ontologically, this engages feedback deep within the process of becoming a researcher through supervision which is itself reflexive and responsive to project dynamics and institutional vagaries.

Analytically, this review has been conducted through a clearly articulated method involving criteria-determined selection of relevant journal articles. It established a rich data corpus for its thematically driven narrative of findings. Feedback processes are being enacted increasingly in online environments spanning different time zones, with professional, cultural and linguistic diversities. Such contexts impact significantly the feedback product co-produced between supervisors and students.

Further research is warranted, especially in the area of evidence-based practice in feedback through the lifespan of a research candidature. This paper identified significant variables impacting feedback that could be explored through such a candidature lifespan approach. Beneficiaries will initially be students and supervisors; however, those with whom and for whom such research is conducted will be the ultimate beneficiaries.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ali, J., H. Ullah, and N. Sanauddin. 2019. “Postgraduate Research Supervision: Exploring the Lived Experience of Pakistani Postgraduate Students.” FWU Journal of Social Sciences 13 (1): 14–25.

- Andrew, M. 2012. “Supervising Doctorates at a Distance: Three trans-Tasman Stories.” Quality Assurance in Education 20 (1): 42–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/09684881211198239.

- Baseer, N., J. Degnan, M. Moffat, and U. Mahboob. 2020. “Micro-Feedback Skills Workshop Impacts Perceptions and Practices of Doctoral Faculty.” BMC Medical Education 20 (1): 29–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1921-3.

- Baseer, N., U. Mahboob, and J. Degnan. 2017. “Micro-Feedback Training: Learning the Art of Effective Feedback.” Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences 33 (6): 1525–1527. doi:https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.336.13721.

- Basturkmen, H., M. East, and J. Bitchener. 2014. “Supervisors’ on-Script Feedback Comments on Drafts of Dissertations: Socialising Students into the Academic Discourse Community.” Teaching in Higher Education 19 (4): 432–445. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2012.752728.

- Baumeister, R. F., and M. R. Leary. 1997. “Writing Narrative Literature Reviews.” Review of General Psychology 1 (3): 311–320. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.1.3.311.

- Cekiso, M., B. Tshotsho, R. Masha, and T. Saziwa. 2019. “Supervision Experiences of Postgraduate Research Students at One South African Higher Education Institution.” South African Journal of Higher Education 33 (3): 8–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.20853/33-3-2913.

- Cree, V. E. 2012. “‘I’d Like to Call You My Mother.’ Reflections on Supervising International PhD Students in Social Work.” Social Work Education 31 (4): 451–464. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2011.562287.

- Deshpande, A. 2017. “Faculty Best Practices to Support Students in the ‘Virtual Doctoral Land’.” Higher Education for the Future 4 (1): 12–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2347631116681211.

- Ding, Q., and N. Devine. 2018. “Exploring the Supervision Experiences of Chinese Overseas PhD Students in New Zealand.” Knowledge Cultures 6 (1): 62–78.

- Doloriert, C., S. Sambrook, and J. Stewart. 2012. “Power and Emotion in Doctoral Supervision: Implications for HRD.” European Journal of Training and Development 36 (7): 732–750. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/03090591211255566.

- East, M., J. Bitchener, and H. Basturkmen. 2012. “What Constitutes Effective Feedback to Postgraduate Research Students? The Students’ Perspective.” Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice 9 (2): 1–16.

- Engebretson, K., K. Smith, D. McLaughlin, C. Seibold, G. Terrett, and E. Ryan. 2008. “The Changing Reality of Research Education in Australia and Implications for Supervision: A Review of the Literature.” Teaching in Higher Education 13 (1): 1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510701792112.

- Evans, C., and K. Stevenson. 2011. “The Experience of International Nursing Students Studying for a PhD in the U.K: A Qualitative Study.” BMC Nursing 10 (11): 11–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6955-10-11.

- Ezebilo, E. 2012. “Challenges in Postgraduate Studies: Assessments by Doctoral Students in a Swedish University.” Higher Education Studies 2 (4): 49–57. doi:https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v2n4p49.

- Feather, D., and K. E. McDermott. 2014. “The Role of New Doctoral Supervisors in Higher Education - a Reflective View of Literature and Experience Using Two Case Studies.” Research in Post-Compulsory Education 19 (2): 165–176. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13596748.2014.897506.

- González-Ocampo, G., and M. Castelló. 2018. “Writing in Doctoral Programs: Examining Supervisors’ Perspectives.” Higher Education 76 (3): 387–401. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0214-1.

- Grant, K., R. Hackney, and D. Edgar. 2014. “Postgraduate Research Supervision: An ‘Agreed’ Conceptual View of Good Practice through Derived Metaphors.” International Journal of Doctoral Studies 9: 043–060. doi:https://doi.org/10.28945/1952.

- Green, B. N., C. D. Johnson, and A. Adams. 2006. “Writing Narrative Literature Reviews for Peer-Reviewed Journals: Secrets of the Trade.” Journal of Chiropractic Medicine 5 (3): 101–117. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0899-3467(07)60142-6.

- Grossman, E., and N. Crowther. 2015. “Co-Supervision in Postgraduate Training: Ensuring the Right Hand Knows What the Left Hand is Doing.” South African Journal of Science 111 (11/12): 1–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2015/20140305.

- Hemer, S. R. 2012. “Informality, Power and Relationships in Postgraduate Supervision: Supervising PhD Candidates over Coffee.” Higher Education Research & Development 31 (6): 827–839. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.674011.

- Herrmann, K. J., and G. Wichmann-Hansen. 2017. “Validation of the Quality in PhD Processes Questionnaire.” Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education 8 (2): 189–204. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/SGPE-D-17-00017.

- Heyns, T., P. Bresser, T. Buys, I. Coetzee, E. Korkie, Z. White, and B. Mc Cormack. 2019. “Twelve Tips for Supervisors to Move towards Person-Centered Research Supervision in Health Care Sciences.” Medical Teacher 41 (12): 1353–1358. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1533241.

- Higgins, J. P., J. Thomas, J. Chandler, M. Cumpston, T. Li, M. J. Page, and V. A. Welch. 2019. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Glasgow, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Juwah, C., D. Macfarlane-Dick, B. Matthew, D. Nicol, D. Ross, and B. Smith. 2004. “Enhancing Student Learning through Effective Formative Feedback.” The Higher Education Academy 140: 1–40.

- Kiley, M. 2019. “Doctoral Supervisory Quality from the Perspective of Senior Academic Managers.” Australian Universities’ Review 61 (1): 12–21.

- Leggat, P., and K. Martinez. 2010. “Exploring Emerging Issues in Research Higher Degree Supervision of Professional Doctorate Students in the Health Sciences.” Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice 15 (4): 601–608. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-008-9119-1.

- Leong, S. 2010. “Mentoring and Research Supervision in Music Education: Perspectives of Chinese Postgraduate Students.” International Journal of Music Education 28 (2): 145–158. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761410362940.

- Lim, J., D. Covrig, S. Freed, B. De Oliveira, M. Ongo, and I. Newman. 2019. “Strategies to Assist Distance Doctoral Students in Completing Their Dissertations.” International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 20 (5): 192–210.

- Lindsay, S. 2015. “What Works for Doctoral Students in Completing Their Thesis?” Teaching in Higher Education 20 (2): 183–196. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2014.974025.

- Lonka, K., E. Ketonen, J. Vekkaila, M. Cerrato Lara, and K. Pyhältö. 2019. “Doctoral Students’ Writing Profiles and Their Relations to Well-Being and Perceptions of the Academic Environment.” Higher Education 77 (4): 587–602. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0290-x.

- Manathunga, C. 2012. “Supervisors Watching Supervisors: The Deconstructive Possibilities and Tensions of Team Supervision.” Australian Universities’ Review 54 (1): 29–37.

- Maor, D., and J. Currie. 2017. “The Use of Technology in Postgraduate Supervision Pedagogy in Two Australian Universities.” International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 14 (1): 1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-017-0046-1.

- McCallin, A., and S. Nayar. 2012. “Postgraduate Research Supervision: A Critical Review of Current Practice.” Teaching in Higher Education 17 (1): 63–74. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2011.590979.

- Morris, S., R. Pitt, and C. Manathunga. 2012. “Students’ Experiences of Supervision in Academic and Industry Settings: Results of an Australian Study.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 37 (5): 619–636. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2011.557715.

- Mustafa, B. A., A. Noraziah, and M. A. Majid. 2014. “Feedback in Postgraduate Supervisory Communication: An Insight from Educators.” The Online Journal of Quality in Higher Education 1 (3): 12–15.

- Nasiri, F., and F. Mafakheri. 2015. “Postgraduate Research Supervision at a Distance: A Review of Challenges and Strategies.” Studies in Higher Education 40 (10): 1962–1969. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.914906.

- Nethsinghe, R., and J. Southcott. 2015. “A Juggling Act: Supervisor/Candidate Partnership in a Doctoral Thesis by Publication.” International Journal of Doctoral Studies 10: 167–185. doi:https://doi.org/10.28945/2256.

- NSW Government. 2020. "Types of Feedback." Accessed 15 September 2020. https://education.nsw.gov.au/teaching-and-learning/professional-learning/teacher-quality-and-accreditation/strong-start-great-teachers/refining-practice/feedback-to-students/types-of-feedback#Evaluative2.

- Odena, O., and H. Burgess. 2017. “How Doctoral Students and Graduates Describe Facilitating Experiences and Strategies for Their Thesis Writing Learning Process: A Qualitative Approach.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (3): 572–590. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1063598.

- Olmos-López, P., and J. Sunderland. 2017. “Doctoral Supervisors’ and Supervisees’ Responses to Co-Supervision.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 41 (6): 727–740. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2016.1177166.

- Orellana, M. L., A. Darder, A. Perez, and J. Salinas. 2016. “Improving Doctoral Success by Matching PhD Students with Supervisors.” International Journal of Doctoral Studies 11: 087–103. doi:https://doi.org/10.28945/3404.

- Paré, G., and S. Kitsiou. 2016. “Methods for Literature Reviews.” In Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-Based Approach, edited by Francis Lau and Craig Kuziemsky, 157–179. Victoria, BC: University of Victoria.

- Roumell, E. A. L., and D. U. Bolliger. 2017. “Experiences of Faculty with Doctoral Student Supervision in Programs Delivered via Distance.” The Journal of Continuing Higher Education 65 (2): 82–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07377363.2017.1320179.

- Schulze, S. 2012. “Empowering and Disempowering Students in Student-Supervisor Relationships.” Koers - Bulletin for Christian Scholarship 77 (2): 1–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.4102/koers.v77i2.47.

- Scott, S. V. 2014. “Practising What we Preach: Towards a Student-Centred Definition of Feedback.” Teaching in Higher Education 19 (1): 49–57. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2013.827639.

- Severinsson, E. 2012. “Research Supervision: Supervisory Style, Research-Related Tasks, Importance and Quality - Part 1.” Journal of Nursing Management 20 (2): 215–223. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2011.01361.x.

- Siltanen, J., X. Chen, A. Doyle, and A. Shotwell. 2019. “Teaching, Supervising, and Supporting PhD Students: Identifying Issues, Addressing Challenges, Sharing Strategies.” Canadian Review of Sociology = Revue Canadienne de Sociologie 56 (2): 274–291. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/cars.12239.

- Soumana, A. O., and M. R. Uddin. 2017. “Factors Influencing the Degree Progress of International PhD Students from Africa: An Exploratory Study.” Üniversitepark Bülten 6 (1): 79–94. doi:https://doi.org/10.22521/unibulletin.2017.61.7.

- Templier, M., and G. Paré. 2015. “A Framework for Guiding and Evaluating Literature Reviews.” Communications of the Association for Information Systems 37 (6): 112–137. doi:https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.03706.

- Wang, T., and L. Y. Li. 2011. “Tell Me What to Do’ vs. ‘Guide Me through It’: Feedback Experiences of International Doctoral Students.” Active Learning in Higher Education 12 (2): 101–112. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787411402438.

- Ward, A. 2013. “Empirical Study of the Important Elements in the Researcher Development Journey.” Knowledge Management & E-Learning 5 (1): 42–55.

- White, T., and E. Coetzee. 2014. “Postgraduate Supervision: E-Mail as an Alternative.” Africa Education Review 11 (4): 658–673. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/18146627.2014.935010.

- Woolderink, M., K. Putnik, H. van der Boom, and G. Klabbers. 2015. “The Voice of PhD Candidates and PhD Supervisors. A Qualitative Exploratory Study Amongst PhD Candidates and Supervisors to Evaluate the Relational Aspects of PhD Supervision in The Netherlands.” International Journal of Doctoral Studies 10: 217–235. doi:https://doi.org/10.28945/2276.

- Yarwood-Ross, L., and C. Haigh. 2014. “As Others See Us: What PhD Students Say about Supervisors.” Nurse Researcher 22 (1): 38–44. (2014+) doi:https://doi.org/10.7748/nr.22.1.38.e1274.

- Zeegers, M., and D. Barron. 2012. “Pedagogical Concerns in Doctoral Supervision: A Challenge for Pedagogy.” Quality Assurance in Education 20 (1): 20–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/09684881211198211.

- Zhao, C. M., C. M. Golde, and A. C. McCormick. 2007. “More than a Signature: How Advisor Choice and Advisor Behaviour Affect Doctoral Student Satisfaction.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 31 (3): 263–281. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03098770701424983.