Abstract

PhD candidates, like all students, learn through engaging with feedback. However, there is limited understanding of how feedback strategies support doctoral candidates. This qualitative framework synthesis of 86 papers analysed rich qualitative data about feedback within PhD supervision. Our synthesis, informed by sociomateriality and a dialogic, sense-making view of feedback, underscores the critical role that feedback plays in doctoral supervision. Supervisors, through their engagement or disengagement with feedback, controlled candidates’ access to tacit and explicit standards. The ephemeral and generative nature of verbal feedback dialogues contrasted with concrete textual comments. While many supervisors aimed for candidates to become less reliant on feedback over time, this did not necessarily translate to practice. Our findings suggest that balancing power dynamics might be achieved through focussing on feedback materials and practices rather than supervisor-candidate relationships.

Introduction

Professional and personal crises are common among doctoral candidates (Katz Citation2018) and experiences with feedback may be part of the problem (Engebretson et al. Citation2008). Feedback is a process that enables university students to gauge their progress, direct their efforts and participate in academic debate. Multiple meta-analyses suggest it has highly positive effects on learning (Hattie and Timperley Citation2007; Wisniewski, Zierer, and Hattie Citation2019). However, while feedback and feedback research holds a prominent position in the higher education literature, its role in the PhD experience is considerably less studied (Chugh, Macht, and Harreveld Citation2021). For many in doctoral education, feedback may be seen as a pedagogical technique that primarily pertains to written work. However, feedback can be defined as a broader process where the learner makes sense of, and acts upon, useful information about their work (Henderson et al. Citation2019). From this perspective, feedback is embedded within doctoral supervision. Feedback strategies may therefore need to take account of the intense interpersonal nature of doctoral studies, where the supervisor-candidate relationships span years rather than months. By examining how feedback manifests within supervisory contexts, which are dynamic, socially bound and intensely interpersonal, we can infer feedback strategies that enhance doctoral supervision.

Many publications examine PhD supervision but feedback tends to be given cursory attention. Indeed, Chugh, Macht, and Harreveld (Citation2021) recent narrative review suggests that feedback is rarely a focus of doctoral studies research. Their analysis focusses on practical feedback strategies for doctoral supervisors such as: developing a ‘positive supervisory relationship’, articulating ‘suitable feedback content’ and finding ‘suitable and balanced ways of giving feedback’ (689). However, doctoral education is equally as enmeshed with interpersonal relationships, institutional strategies and academic power structures as it is with educational practices (Bastalich Citation2017). Indeed, feedback within doctoral supervision can be understood as an entree to broader academic practices (Carless, Jung, and Li Citation2023). Therefore, we build on Chugh, Macht, and Harreveld’s (Citation2021) review by employing a formal qualitative synthesis, which gathers together ‘analytical depth and contextualised detail’ (Pope, Mays, and Popay Citation2007, 78) from qualitative studies, to discern the distinctive nature of feedback practices in PhD supervision within the existing literature.

We adopt two conceptual underpinnings. We regard feedback as primarily a formative development process and therefore emphasise a facilitative and dialogic approach (Evans Citation2013). Boud and Molloy (Citation2013) differentiation of feedback designs—by their focus on teacher or learner—can provide useful insights. In a teacher-focussed design, feedback is concerned with how the teacher constructs messages that are timely, evaluative and help students to better complete the next task. However, this overlooks the need for a student to respond to this information. Student-oriented perspectives of feedback encompass how students access and make meaning of messages (from teacher, self and peers) in order to better complete the next related task. This latter view is exemplified by the definition of feedback as ‘a process in which learners make sense of information about their performance and use it to enhance the quality of their work or learning strategies’ (Henderson et al. Citation2019, 1402).

Our second conceptual frame acknowledges that feedback takes place within the complex social world of doctoral studies. Therefore, we adopt a sociomaterial approach. This perspective regards learning as constituted within situated social interactions but also acknowledges the contributions of materials, including objects and places. A sociomaterial view of feedback encompasses the interactions between the learner, the teacher, the objects they produce and the spaces they inhabit and change (Gravett Citation2020). Thus doctoral supervision can be seen as a dynamic interplay between teachers, learners, objects and places, which emerge across time and space (Fenwick, Nerland, and Jensen Citation2012).

These two frameworks highlight the distinctive nature of this review, which provides an in-depth qualitative analysis to provide insights into the dialogic, relational, contextual and temporal nature of feedback practices in doctoral supervision.

Review aims

The overall aim of this qualitative synthesis is to enhance current approaches to feedback in PhD supervision. The research question for the review is: what feedback practices are described within the PhD supervision literature? A secondary question is: how do these practices influence doctoral candidates?

Methods

Framework-based synthesis methodology

We have adapted a framework-based qualitative synthesis approach (Dixon-Woods Citation2011), a research methodology for both deductively and inductively interrogating qualitative studies through the development of a conceptual framework prior to reviewing the literature. This approach allows review of the literature for feedback practices, which might not be explicitly investigated but could be interpreted from secondary analysis of research.

Conceptual framework development

In accordance with the framework synthesis approach, we inductively derived a conceptual framework, based on the literature and our own research expertise, sensitised by the two orientations outlined in the introduction: a learner-oriented dialogic view of feedback and sociomateriality. Initially, each researcher charted their conceptions of feedback using a series of pre-set questions interrogating the literature as well as beliefs, definitions and experiences about feedback and supervision (see supplementary material S1) to develop our reflexivity. Our literature-based understandings of feedback drew from previous reviews of feedback (Kluger and DeNisi Citation1996; Hattie and Timperley Citation2007; Evans Citation2013; Johnson Citation2016; Bing-You et al. Citation2018). Our conceptualisations drew from contemporary higher education feedback literature (Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick Citation2006; Boud and Molloy Citation2013; Carless and Boud Citation2018; Tai et al. Citation2018). We emphasised the dialogic, where supervisors and candidates enact a ‘dynamic and co-constructive process in a shared social or cultural space’ (Ajjawi and Regehr Citation2019, 652–653).

We held several meetings to discuss and inductively derive an initial framework, clustering concepts within the literature into categories. The framework was broadly set within a sociomaterial perspective, but it also acknowledged the frequently cognitive or sociocultural foundations of much feedback literature. The framework was interrogated against four papers from the dataset selected for their diversity and adjusted through consensus throughout analysis. The final framework categories are presented in the first column of .

Table 1. Conceptual framework for analysis of feedback within the included literature.

Searching the literature

A systematic search was used to identify relevant literature. The search terms supervis* AND (PhD OR doctora*) AND (‘higher education’ or university) were used to search within the title, abstract and keywords for literature indexed in Scopus, ProQuest Central and Ebscohost. The search results were limited to English and scholarly peer-reviewed journals where possible and the final search was conducted on Monday 6 March 2023. We deliberately did not use the word feedback, because we knew there were limited studies on feedback, focused mostly on writing, and we wanted to look for how feedback practices took place within the broader context of supervision.

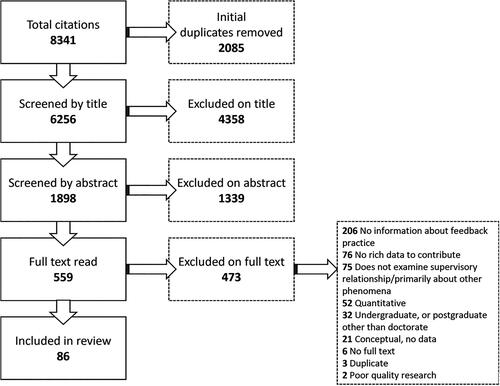

The initial title screening for relevance was completed in EndNote (MB, JT, PM). Records were then imported into Covidence, where MB, JT, EM, MH and PM read the abstracts and subsequently the full text of the article to determine inclusion. The total number of citations at each step and reasons for exclusion at the full text stage are given in .

To be included, papers had to contain participant data which provided a rich description of feedback processes within the supervisor-candidate relationship. This included any process regarding the provision of information about work, including advice, communications, dialogues, coaching and iterative task-setting. Researchers made judgements about the quality of data at this time, including studies that contained thick or rich qualitative data, which makes accessible ‘the meaning and significance of behaviors or events’ (Schultze and Avital Citation2011, 3). To ensure consistency across the research team, we examined in-depth five manuscripts that dealt with borderline characteristics to discuss and explicate the inclusion and exclusion criteria. If there was any uncertainty about an inclusion, the paper was reviewed twice.

Analysis process

The framework was initially applied to 30 papers, which represented a broad selection of the literature from the first search year of 2018. Each paper was then analysed into its salient themes using a coding framework based on the categories in , which collated information about the paper and extracted the relevant data for each of the categories. Each category was thematically analysed (Bearman and Dawson Citation2013). The remaining papers were read in detail (MB, JT or PM) and compared against the current synthesis to develop an extensive thematic analysis (see interim codes within supplementary materials S3 as an audit trail). We considered paper quality when interpreting the papers’ findings, aligning with the questions in Long and Godfrey (Citation2004) qualitative research quality assessment tool around phenomenon, context, ethics and researcher position. In particular, we paid attention to whether data was ‘collected with sufficient detail and depth to provide insight into the meaning and perceptions of informant’ (Long and Godfrey Citation2004, 186) when synthesising across many different papers within a category.

Results

We included 86 qualitative studies in our final synthesis from 23 countries, predominantly Australia (20), the United Kingdom (19), New Zealand (12), USA (5) and Hong Kong (5). Over one-third studied more than one discipline (32), while others were based in the humanities (18), education/psychology (16), science or medical disciplines (9), and business (2). Nine did not specify any discipline. Publications dated from before 2000 (2), 2000–2004 (1), 2005–2009 (14), 2010–2014 (16), 2015–2018 (23) and 2019–2023 (30). All studies used either qualitative or mixed methods. Participants in studies were either candidates (35 studies), supervisors (12 studies), or both parties (39 studies). The studies had various focal phenomena, including supervisory relationships (42 studies); feedback (19 studies); writing (18 studies); intercultural differences (13 studies); supervision models (11 studies); and roles and experience through self-study (13 studies). See supplementary material S2 for a complete listing of all studies and their various research foci.

We now present an analysis describing feedback practices reported within these studies (see for an overview).

Table 2. Overview of thematic analysis.

Supplementary materials S3 provides detailed references associated with each theme and illustrative quotes, as well as audit trail of interim content; only limited citations are provided in the main manuscript.

Contexts of feedback practices

National influences. Feedback in doctoral supervision was informed by the global movement of students, which meant that PhD supervision was frequently an intercultural relationship. However, this could lead to cultural disjunctions in views of feedback, thereby disrupting supervisory relationships (Hu, van Veen, and Corda Citation2016; Nomnian Citation2017; Xu Citation2017; Elliot and Kobayashi Citation2019; Alabdulaziz Citation2020; Alebaikan, Bain, and Cornelius Citation2020; Yang and Yuan Citation2020; Xu, Lin, and Cai Citation2021); less commonly, it could lead to intercultural exchange and mutual learning (Xu, Lin, and Cai Citation2021). Other politico-economic influences included a requirement for income from international students leading to ‘fast supervision’ (Fitzpatrick and Fitzpatrick Citation2015, 52).

Disciplinary influences. Disciplines came with their own tacit values and standards, and feedback practices taught candidates about these (Hasrati Citation2005; Lee Citation2008; Blicblau, McManus, and Prince Citation2009; Sun and Trent Citation2020). As a student from Xu, Lin, and Cai’s Citation2021 study (126) noted about their supervisors: ‘Their feedback is their judgment of my writing against the disciplinary standards’. Feedback comments introduced the language of the discipline. Fullagar, Pavlidis, and Stadler (Citation2017, 35) reported that as a doctoral candidate started to offer comments on a peer’s work, the peer responded ‘whoa, you just sounded like her. That’s EXACTLY what she would say’. While the spaces and tasks of PhDs appeared strongly discipline-specific, this did not appear to be the case with respect to feedback practices. The studies that compared across disciplines did not reveal any particular divergences (e.g. Acker, Hill, and Black (Citation1994)).

Institutional influences. Institutions prescribed the form of PhD supervision and hence influenced feedback. Notable examples included extending the supervisory dyad (Leijen, Lepp, and Remmik Citation2016), or inclusion of supervisors who are not discipline experts (Wisker et al. Citation2003; Chatterjee Padmanabhan and Rossetto Citation2017).

How feedback is enacted

The value of feedback seemed to spring into sharp relief when it was absent or scarce, partly because the boundaries between feedback practices and other aspects of supervision were blurred. For example, the following supervisor actions pertained in some way to feedback: responding to work by providing candidates with exemplars (González-Ocampo and Castelló Citation2018); reviewing a joint paper and providing thoughts and revisions to help frame the work for publication (Li Citation2006); dividing tasks into chunks, as ‘to give feedback on smaller tasks would prevent the students being overwhelmed’ (Catterall et al. Citation2011, 4). Generally, enactments of feedback practices were comprised of talk, text and formal progress reporting processes.

Talk. Face-to-face talk – or dialogue – was an important part of feedback practices, although not all wanted to participate (Odena and Burgess Citation2017). Johnson (Citation2014, 75) proposed that: ‘[t]alking not only helps to clarify thinking, it shifts the student’s role from writer to external reader or observer’. Several studies noted some candidates from second language backgrounds had difficulty in participating in these discussions (Nomnian Citation2017; Elliot and Kobayashi Citation2019; Xu, Lin, and Cai Citation2021). Indeed, talk could be chiding or unsupportive (Barnes and Austin Citation2009). Space was seen as important to some; an informal setting could make it easier for students to handle constructive criticism (Hemer Citation2012) and build a disciplinary identity: ‘We have a cup of coffee, mull over what he’s been reading, talk about his ideas – basically to embed him in the department and give him a sense of belonging’ (Delamont, Parry, and Atkinson Citation1998, 165).

Text. Student writing was strongly associated with feedback practices: ‘students and supervisors nominated feedback as the primary strategy by which students learned to write’ (Aitchison et al. Citation2012, 441). Feedback practices were often prompted by and focussed on particular texts, such as the thesis. Text was sometimes described as best mediated with talk (Chatterjee Padmanabhan and Rossetto Citation2017).

Supervisors’ written responses were also significant. Some noted that candidates preferred supervisors’ textual comments: ‘Students tend to value written feedback as they find verbal feedback difficult to remember and even to understand at the time’ (Backhouse, Ungadi, and Cross Citation2015, 26). The idea of a physical artefact was helpful for some candidates, as ‘you can visit and revisit it many times’ (Odena and Burgess Citation2017, 579). Xu, Lin, and Cai (Citation2021, 128) described a student’s careful consideration of comments: ‘I look at each comment, revise the writing firstly by applying those I understand and agree with, but come back to supervisors to clarify those I don’t understand and argue for those I don’t agree with’.

Supervisors described responding to student writing as a ‘balancing act’ (Jackson, Power, and Usher Citation2021, 1) where comments on a thesis should be developmental and motivating but also critical, precise and conveying appropriate complexity. Certainly, minimal or cryptic comments were not valued (Wei, Carter, and Laurs Citation2019). Some supervisors used feedback comments that took the form of ‘order and obey’ (Li Citation2016, 55) and some candidates followed suit: ‘I just clicked “accept all changes”’(Yang and Yuan Citation2020, 8).

Formal progress-reporting processes. Formal progress milestones, where a student presents their research to a panel of experts, were a particular form of feedback enactment. The limited studies examined did not find value in these: ‘We found, without exception, that students refused to comment on their supervisors’ performance and many participants, including the supervisors themselves, were reluctant to put sensitive information on a progress report’ (Mewburn et al. Citation2014, 517). There were also reports of overprotectiveness, such as supervisors over-contributing to written work for milestones (Jackson, Power, and Usher Citation2021).

Dynamics of feedback relationships

The term feedback relationship describes the interpersonal dynamic that permeates, surrounds, supports and impedes feedback enactments between supervisor and student. This was seen as productive when it was viewed as: collaborative (Cotterall Citation2011; Halbert Citation2015; Fullagar, Pavlidis, and Stadler Citation2017; González-Ocampo and Castelló Citation2018; Xu and Hu Citation2020); respectful, in that there was a measure of trust (Fitzpatrick and Fitzpatrick (Citation2015)) and the supervisor was credible (Al Makhamreh and Kutsyuruba (Citation2021)); and when expectations or styles ‘matched’ (Halbert Citation2015, 34).

There was an overall sense that relationships were developed by feedback and feedback was developed by relationships (Al Makhamreh and Kutsyuruba Citation2021; Xu, Lin, and Cai Citation2021). These feedback relationships shifted and changed over time (Delamont, Parry, and Atkinson Citation1998) but were by no means linear (Clarke and Ryan Citation2006). They had to account for: 1) the considerable institutional authority invested in supervisors; 2) the emotive nature of feedback; and 3) the role of other actors in mediating comments.

Power in feedback relationships. Feedback could be viewed as a power struggle (Aitchison et al. Citation2012; Gunnarsson, Jonasson, and Billhult Citation2013). Several papers suggested the usefulness of candidates’ preparedness to contest supervisor views (Carter and Kumar Citation2017; Inouye, McAlpine, and Practice Citation2017; Ding and Devine Citation2018). However, through feedback, the supervisor implicitly controlled the flow of the information (Acker, Hill, and Black Citation1994) or ‘exercise[d their] authority’(Sun and Trent Citation2020, 9). This could be benign: supervisors often used their authority within feedback processes to encourage candidates to build confidence (Johnson Citation2014) or take more ownership over their work (Lee Citation2008). However, one consequence of the power imbalance was that supervisors could be unaware of candidates’ views of their feedback relationships. In other words, students often pretended to understand when they didn’t (Fullagar, Pavlidis, and Stadler Citation2017; Elliot and Kobayashi Citation2019; Alabdulaziz Citation2020; Xu, Lin, and Cai Citation2021).

Power was exerted by candidates through withholding engagement with feedback (Aitchison et al. Citation2012; Backhouse, Ungadi, and Cross Citation2015) or seeking feedback beyond the supervisory relationship (Mills and Paulson Citation2014; Inouye, McAlpine, and Practice Citation2017). In cases where supervisors were not ‘up to date’ on the candidate’s projects, candidates might doubt comments (Gunnarsson, Jonasson, and Billhult Citation2013, 3). Equally, candidates had views about the credibility of supervisors’ feedback practices (Catterall et al. Citation2011; Cotterall Citation2011; Aitchison et al. Citation2012).

Several studies reported feedback as a form of supervisory power abuse, including ‘screaming’ (Wei, Carter, and Laurs Citation2019, 165), emotional manipulation (Aitchison et al. Citation2012) or unavailability (Ali, Ullah, and Sanauddin Citation2019). The worst instances were manifested by complete withdrawal from meaningful feedback dialogue (Mills and Paulson Citation2014; Li Citation2016; Virtanen, Taina, and Pyhältö Citation2017).

Against this backdrop of supervisory authority, some studies from the last decade emphasised collaboration and co-construction as an effective way to approach supervision and, by extension, feedback (Fullagar, Pavlidis, and Stadler Citation2017; González-Ocampo and Castelló Citation2018; Xu, Lin, and Cai Citation2021). On occasion, within feedback conversations supervisors appeared to ‘downgrad[e their] epistemic primacy, even in cases where we might expect supervisors to “know the answer”’(Nguyen and Mushin Citation2022, 7). While this feedback relationship was dialogic, power had to be exercised carefully in order to ensure that the relationship remained strong and respectful.

Emotional responses. Feelings were intimately entwined with feedback relationships. Candidates repeatedly described strongly negative reactions such as distress when receiving critical feedback; students reported feeling ‘gutted’ (Wei, Carter, and Laurs Citation2019, 162), ‘overwhelm[ed]’(Weise, Aguayo-González, and Castelló Citation2020, 311), and ‘totally deflated’ (Li and Seale Citation2007, 521). On the other hand, complimentary comments could lead to increased motivation (Acker, Hill, and Black Citation1994; Broegaard Citation2018; Kumar and Kaur Citation2019; Weise, Aguayo-González, and Castelló Citation2020; Jackman and Sisson Citation2021). As one candidate noted: ‘I’m like a little kid, I’m so pleased, and then I have renewed impetus’ (Acker, Hill, and Black Citation1994, 487). Students reported self-regulatory behaviours when receiving ‘negative’ constructive criticism and recognised that they could use such information to improve. However, this performance of ‘appearing open’ while feeling the inverse could take a complex emotional toll (Li and Seale Citation2007; Devine and Hunter Citation2017). As one candidate noted, ‘I don’t want to be seen as either defensive or unable to handle criticism’ (Devine and Hunter Citation2017, 340).

Supervisors also reported emotive responses to feedback (Catterall et al. Citation2011; Carter and Kumar Citation2017). These were framed as frustrations when candidates did not respond in the way supervisors wished or, alternatively, as pride in being a good supervisor.

Feedback beyond a supervisor-student dyad. The more recent publications referred to multi-supervisory teams, and co-supervisors could assume different roles with respect to feedback (Odena and Burgess Citation2017; Hopman Citation2021). Additional supervision could lead to more feedback and enhanced motivation (Robertson Citation2017). However, candidates could receive contradictory feedback comments and supervisor disagreement over feedback could have a negative impact on students (McAlpine and McKinnon Citation2013; Olmos-López and Sunderland Citation2017; Blythe Citation2019; Alabdulaziz Citation2020). Supervisors could withhold feedback to avoid conflicting advice (Olmos-López and Sunderland Citation2017) and candidates could wait for supervisors to argue it out (Guerin and Green Citation2015). Peers could also assist in mediating supervisors’ comments (Alabdulaziz Citation2020; Yang and Yuan Citation2020).

What supervisors and candidates bring to feedback practices

Supervisors’ and candidates’ histories and dispositions influenced feedback enactments. From the supervisor’s perspective, there was a sense that many drew from their experiences of feedback as PhD students (Delamont, Parry, and Atkinson Citation1998; Lee Citation2008; Hemer Citation2012; Johnson Citation2014; Robertson Citation2017; Sánchez-Martín and Seloni Citation2019). Supervisors’ beliefs and expectations about candidate’s capabilities and interest in the topic also influenced their feedback processes (Li Citation2006; Johnson Citation2014; Hu, van Veen, and Corda Citation2016).

Candidates had a range of individualised feedback needs. For example, native and second-language speakers had different feedback needs with respect to argumentation and rhetorical representation (Bitchener, Basturkmen, and East Citation2010). Candidates’ histories were less explored, although students must have come to the supervisory relationships with prior experiences of feedback. Inouye, McAlpine, and Practice (Citation2017) directly addressed the issue of previous feedback experiences; a candidate reported highly negative experiences of feedback leading to personal distress in high school, which may have impacted confidence and agency.

Feedback as a temporal practice

It was taken for granted across studies that feedback enactments changed candidates’ study practices and work, as students responded to comments and supervisors in turn were influenced by these student responses. We noted three temporal practices: 1) continuing reflections in response to comments; 2) timing of feedback enactments; and 3) how feedback changed across the candidature.

Reflections prompted by feedback enactments. Feedback in the form of question-asking provided ‘room to think’ and stimulated deeper reflection (Broegaard Citation2018, 29). However, most studies did not explicitly describe any student reflection prompted by feedback; this appeared mostly taken-for-granted or was mentioned in passing (Johnson Citation2014; Mewburn et al. Citation2014). There was some report of supervisors reflecting on the effectiveness of the feedback they provided (Delamont, Parry, and Atkinson Citation1998), while others seemed to avoid reflective practice. For example, a supervisor frustratedly described students ignoring comments as ‘Ground Hog Day’ – with the sense that the supervisor had not examined their own practices as to why this might be so (Carter and Kumar Citation2017, 71).

Timing of comments. Some noted timing of comments was critical: too long and the candidate became disengaged (Acker, Hill, and Black Citation1994) or it became a lost opportunity for improvement (Aitchison et al. Citation2012; Mills and Paulson Citation2014). Particular phase-related tasks, such as preparation of a thesis, drove feedback-seeking behaviours from students (McAlpine and McKinnon Citation2013). Supervisors’ unavailability to comment close to submission could leave students feeling vulnerable or neglected (De Caux Citation2021).

How feedback enactments changed over time. Both supervision and feedback shifted and changed over the lifecycle of candidature (Wisker et al. Citation2003; McAlpine and McKinnon Citation2013). Feedback changed as trust was established, academic skills were developed, and scaffolding was removed (Whitelock, Faulkner, and Miell Citation2008; Blicblau, McManus, and Prince Citation2009; Catterall et al. Citation2011). In Hu, van Veen, and Corda’s (Citation2016) case study of an international student and a supervisor, a growing knowledge of the potential misunderstandings and cultural differences helped the supervisor to change his behaviour and become more explicit about his expectations and feedback comments.

Supervisors deliberately promoted independence through feedback as the candidature progressed (Catterall et al. Citation2011; Inouye, McAlpine, and Practice Citation2017): ‘At first they would offer suggestions, but in the last year would just circle things and expect me to know how to improve’ (Catterall et al. Citation2011, 4). Candidates identified removal of scaffolding as helpful for the development of critical thinking and writing (Odena and Burgess Citation2017) or independence (Hu, Zhao, and van Veen Citation2020; Sun and Trent Citation2020). In one study, a conversational analysis revealed how feedback responses could build independence through orientation to what researchers do in practice: ‘in response to [the candidate’s] solicitation of feedback, instead of addressing her question, [the supervisor] talks about various ways one can make decisions when constructing thesis chapters. In doing so, he is teaching her about what an independent researcher might do under the circumstances to make such decisions’ (Nguyen and Mushin Citation2022, 10). Sometimes, candidates’ engagement with feedback also promoted independence, enhanced by their own active reapplication (Xu, Lin, and Cai Citation2021) or prompted by feelings of disempowerment (Jones and Blass Citation2019).

On the other hand, there were studies suggesting that sometimes the candidate was learning to better read and placate their supervisor, rather than developing independence: ‘Doctoral students spend considerable time and energy trying to interpret, understand and accommodate their supervisors’ standpoints and expectations’ (Backhouse, Ungadi, and Cross Citation2015, 28). Another candidate noted: ‘There was a time where my supervisor was very unhappy with my work… I responded exactly how I thought he wanted me to, since he would be responsible for letters of reference and job opportunities. Since this time, my supervisor has been very happy with all of my work’ (Devine and Hunter Citation2017, 340).

The absence of feedback could lead to early termination of candidature or failure. For example, Leijen, Lepp, and Remmik (Citation2016) argued that lack of clarity and quality of feedback comments were prominent reasons for candidates discontinuing. Mills and Paulson (Citation2014) reported how, in one instance, complete absence of feedback led to distress, humiliation and formal failure.

Discussion

Our analysis demonstrates the centrality of feedback enactments to PhD supervision. Feedback practices built good supervisory relationships and vice versa. Feedback supported candidates coming to know the tacit knowledge practices of the discipline. The ephemeral nature of talk contrasted with the concrete nature of written feedback comments, which were preferred by students but seemed to lack the generative nature of dialogic interactions. While many supervisors emphasised the aspiration that, over time, candidates would become less dependent on feedback, it was unclear when candidates were simply appeasing their supervisors by incorporating their views.

We now explore implications of the results, sensitised by a sociomaterial sensibility and a dialogic, sense-making view of feedback, and drawing from the broader literature on doctoral supervision. We focus particularly on three aspects: 1) feedback as power; 2) the role of talk, text and time in feedback pedagogic practices; and 3) the disjunction between the described practices and current aspirations in the feedback literature.

Feedback as power

Many studies within the review suggest that the supervisory relationship and feedback enactments mutually constituted each other. The inherent power of making judgements about another’s work was magnified by the authority invested in supervisors. This aligns with how Bengsten (Citation2016, 52) describes the structuring nature of power in these types of situations, observing ‘the heaviness and importance of supervisor’s evaluation and judgement and the passive receptiveness of the students’ responses [that] showed their lack of control and power’. We go further to say that supervisors, through their engagement or disengagement with feedback, controlled the progress of candidates. Learning appeared to flourish when feedback relationships were dialogic and co-constructed – where supervisor and candidate remained open to each other’s views. In these instances, ownership of the feedback was between the dyad, not weighted in either direction. This seemed particularly important where candidates and supervisors had different cultural backgrounds.

This review provides the new insight that feedback shapes the power relationship, and the power relationship shapes feedback. The impact of power can be difficult to acknowledge and articulate; however, the materials of the feedback relationship offer concrete traces of these imbalances. They provide a point for scrutiny and reflection for candidates, supervisors and institutions. This insight also assists with the dilemma identified within Bastalich’s (Citation2017) critical review: the need to balance candidate and supervisor input into the research process. We suggest balancing power dynamics can be better achieved through focussing on the objects of feedback rather than the relationship between participants. Feedback cannot take place without the regular exchange of views with opportunities for both parties to speak or write. Documentation of these opportunities can form a point of review. Similarly, the detail and tone of the written comments (and evidence of candidates’ responses) provide opportunities for self or peer review by supervisors (or supervisory teams) of their own feedback practices.

Feedback pedagogic practices: talk, text and time

Interpreting the collected views and experiences of feedback pedagogies as sociomaterial practices reveals the difference between talk and written feedback comments (or text). Talk was a significant means of constituting feedback. In discussion, a candidate’s propositions could be countered, debated or expanded. New ideas could be generated by either party, with suggestions of alternate approaches, readings and sources. In many ways, talk was more focussed on future improvements and less on evaluative comments; the supervisors and students could bend towards each other. This is complex territory: Bengsten (Citation2016) suggests that supervisory conversations consists of multiple simultaneous dialogues, sharing generative thinking processes and more formal critical discussions. Our analysis also suggests that face-to-face conversation provided (apparently rare) opportunities for unacceptable supervisor behaviours. Thus, improvisational and ephemeral talk was most generative; but it also seemed most dependent on collaborative supervisory relationships.

Feedback as text most closely resembled the types of exchanges that occur in coursework, whereby a student produces work and a teacher provides comments on it. Kamler and Thomson (Citation2014) suggest that writing for doctoral candidates is a critical means of developing thinking and positioning oneself in the academic field. Thus, feedback as text may be even more significant for doctoral candidates than for undergraduates. Talking through and with texts appeared to be a highly productive mode of feedback but the complexity of this territory is highlighted by joint publications during candidature, which entangle supervisor’s and candidate’s writing (Aitchison, Kamler, and Lee Citation2010) and blur the line between feedback and joint work. Future research into this textually mediated discussion may offer new insights into feedback overall.

Time was an important but often overlooked factor in feedback practices. Feedback practices shifted depending on the development of the candidate’s independence, but although supervisors expected increasing research independence, and adjusted their feedback processes to account for it, only one paper (Nguyen and Mushin Citation2022) reported orientation to standards of practice (Sadler Citation1989), and this was within generative conversation. This type of purposeful orientation allows future ownership of research practices by the student (Boud and Molloy Citation2013) when they are no longer being supervised. This approach may be useful to disrupt the ritualised appeasement described by some studies and replace it with opportunities for development. Other useful feedback pedagogies that build independence include: discussing standards and goals; asking candidates to find and analyse exemplars; requesting self-assessment; and suggesting the candidate find opportunities to assess others’ work. This recasts the problem of developing candidate independence as a matter of feedback pedagogic strategies. Candidates could use the supervisors’ evaluative comments to track movement over time, supplemented by self and peer evaluations. In this way, while supported, the candidate can come to know standards of practice and how they are enacted.

Based on the review findings (but also drawing from the feedback literature), we propose a series of useful pedagogic approaches for feedback in doctoral education (): 1) drawn directly from the included studies; and 2) from the general feedback literature. In addition to these, we consider that monitoring feedback processes themselves would be a useful addition to the supervisory team repertoire. This might include regular collegiate discussion and assessment of textual comments by supervisor(s), and a regular team assessment of feedback processes.

Table 3. Proposed feedback pedagogical strategies within doctoral supervision.

The challenge of sophisticated feedback practices

Many of the effective supervision and feedback practices described within our results and the broader feedback literature require particular pedagogical expertise. This highlights that we may be asking more of our supervisors than their current educational expertise allows. Similarly, these types of approaches rely on students who understand how to learn in sophisticated ways. This is a challenge for institutions where, as this review of literature suggests, academics already struggle to provide supervision (Fitzpatrick and Fitzpatrick Citation2015; Carter and Kumar Citation2017). provides some implications for institutions in trying to support supervisors which may complement other strategies already in place.

Table 4. Institutional support for supervisors.

Limitations

The framework synthesis approach, like all review approaches, has strengths and weaknesses. The strength is its examination of rich data against an analytical framework derived from theory and practice. A limitation is the reworking of data already selected and presented; hence, we might be magnifying possible misinterpretations. Moreover, we were sensitive that there is a broad range of supervision arrangements across nations. In particular, in some countries the supervisors are also the final assessors and the impact of this arrangement was unclear.

Conclusions

This qualitative synthesis of feedback practices within PhD supervision suggests that while feedback is a critical part of doctoral supervision, it deserves further attention as a means to develop candidates and prevent potential abuses of power. The generative nature of talk as part of feedback is particularly overlooked. Similarly, textual feedback is largely limited in focus to textual components of the thesis, whereas it could also be used to promote other areas of candidature including the development of independent practice by the candidate. Through adopting a sociomaterial approach, this synthesis identifies new means of enhancing feedback processes within supervision teams; in particular, reviewing the materials of feedback as a means of promoting productive relationships and explicitly identifying and utilising feedback pedagogical strategies that promote independent learning. These practices would work best in association with professional development for supervisors around learning-centred feedback models, where the learner sets the agenda, goals for future practice are emphasised, and opportunities are co-generated to build candidates’ judgement of their own work, and that of others in their field.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (263.3 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (133.2 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (91.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

We acknowledge Katie Priestley for her expert research assistance.

Seed funding provided by Monash University.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Margaret Bearman

Margaret Bearman is a Research Professor in the Centre for Research in Assessment and Digital Learning (CRADLE). Her focus is on higher and professional education and her interests include feedback, assessment design, and education for a digital world.

Joanna Tai

Joanna Tai is a Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Research in Assessment and Digital Learning, Deakin University, Australia. She researches student experiences of learning and assessment from university to the workplace, including feedback and assessment literacy, evaluative judgement, and peer learning.

Michael Henderson

Michael Henderson is Professor of Digital Futures and Director of Educational Design and Innovation in the Faculty of Education, Monash University. His research spans adult and higher education through to early childhood, with a special focus on the opportunities and challenges afforded by educational technologies

Rachelle Esterhazy

Rachelle Esterhazy is an Associate Professor at the University of Oslo. Her research interests include feedback and assessment practices in higher education, pedagogical design, learning analytics and collegial approaches to academic development.

Paige Mahoney

Paige Mahoney is a Research Fellow at Deakin University’s Centre for Research in Assessment and Digital Learning (CRADLE). She has worked on a range of projects in higher education research, examining topics such as assessment feedback, feedback literacy, and inclusive assessment.

Elizabeth Molloy

Elizabeth Molloy is Associate Dean, Learning and Teaching, as well as a Professor in the Department of Medical Education in the Faculty Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences, The University of Melbourne. Her research interests include workplace learning, feedback and assessment, interprofessional education and clinical supervisor professional development.

References

- Acker, S., T. Hill, and E. Black. 1994. “Thesis Supervision in the Social Sciences: Managed or Negotiated?” Higher Education 28 (4): 483–498. doi:10.1007/BF01383939.

- Aitchison, C., B. Kamler, and A. Lee. 2010. Publishing Pedagogies for the Doctorate and beyond. London: Routledge.

- Aitchison, C., J. Catterall, P. Ross, and S. Burgin. 2012. “Tough Love and Tears’: Learning Doctoral Writing in the Sciences.” Higher Education Research & Development 31 (4): 435–447. doi:10.1080/07294360.2011.559195.

- Ajjawi, R., and G. Regehr. 2019. “When I Say … Feedback.” Medical Education 53 (7): 652–654. doi:10.1111/medu.13746.

- Al Makhamreh, M., and B. Kutsyuruba. 2021. “The Role of Trust in Doctoral Student - Supervisor Relationships in Canadian Universities: The Students’ Lived Experiences and Perspectives.” Journal of Higher Education Theory & Practice, 21 (2): 124–138. doi:10.33423/jhetp.v21i2.4124.

- Alabdulaziz, M. S. 2020. “Saudi Mathematics Students’ Experiences and Challenges with Their Doctoral Supervisors in UK Universities.” International Journal of Doctoral Studies 15 (1): 237–263. doi:10.28945/4538.

- Alebaikan, R., Y. Bain, and S. Cornelius. 2020. “Experiences of Distance Doctoral Supervision in Cross-Cultural Teams.” Teaching in Higher Education 28 (1): 17–34. doi:10.1080/13562517.2020.1767057.

- Ali, J., H. Ullah, and N. Sanauddin. 2019. “Postgraduate Research Supervision: Exploring the Lived Experience of Pakistani Postgraduate Students.” FWU Journal of Social Sciences, 13 (1): 14–25. http://sbbwu.edu.pk/journal/FWU_Journal_Summer%202013_Summer%202019_Vol_13_No_1/2.%20Postgraduate%20Research%20Supervision%20Exploring%20the%20Lived%20Experience.pdf.

- Backhouse, J., B. A. Ungadi, and M. Cross. 2015. “They Can’t Even Agree!’: Students’ Conversations about Their Supervisors in Constructing Understandings of the Doctorate.” South African Journal of Higher Education 29(4), 14–34. doi:10.20853/29-4-507.

- Barnes, B. J., and A. E. Austin. 2009. “The Role of Doctoral Advisors: A Look at Advising from the Advisor’s Perspective.” Innovative Higher Education 33 (5): 297–315. doi:10.1007/s10755-008-9084-x.

- Bastalich, W. 2017. “Content and Context in Knowledge Production: A Critical Review of Doctoral Supervision Literature.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (7): 1145–1157. doi:10.1080/03075079.2015.1079702.

- Bearman, M., and P. Dawson. 2013. “Qualitative Synthesis and Systematic Review in Health Professions Education.” Medical Education 47 (3): 252–260. doi:10.1111/medu.12092.

- Bengsten, S. S. E. 2016. Doctoral Supervision: Organisation and Dialogue. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

- Bing-You, R., K. Varaklis, V. Hayes, R. Trowbridge, H. Kemp, and D. McKelvy. 2018. “The Feedback Tango: An Integrative Review and Analysis of the Content of the Teacher–Learner Feedback Exchange.” Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges 93 (4): 657–663. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001927.

- Bitchener, J., H. Basturkmen, and M. East. 2010. “The Focus of Supervisor Written Feedback to Thesis/Dissertation Students.” International Journal of English Studies 10 (2): 79–97. doi:10.6018/ijes/2010/2/119201.

- Blicblau, A. S., K. J. McManus, and A. Prince. 2009. “Developing Writing Skills for Graduate Nesbc Students.” The Reading Matrix, 9 (2): 198–210.

- Blythe, S. M. 2019. “Effective Research Supervision.” Journal of European Baptist Studies, 19 (1): 95–110.

- Boud, D., and E. Molloy. 2013. “Rethinking Models of Feedback for Learning: The Challenge of Design.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 38 (6): 698–712. doi:10.1080/02602938.2012.691462.

- Boud, D., R. Ajjawi, P. Dawson, and J. Tai. 2018. Developing Evaluative Judgement in Higher Education: Assessment for Knowing and Producing Quality Work. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Broegaard, R. B. 2018. “PhD Supervision Strategies in a Cross-Cultural Setting: Enriching Learning Opportunities.” Dansk Universitetspædagogisk Tidsskrift 13 (25): 18–36. doi:10.7146/dut.v13i25.104330.

- Butler, D. L., and P. H. Winne. 1995. “Feedback and Self-Regulated Learning: A Theoretical Synthesis.” Review of Educational Research 65 (3): 245–281. doi:10.3102/00346543065003245.

- Carless, D., and D. Boud. 2018. “The Development of Student Feedback Literacy: Enabling Uptake of Feedback.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 43 (8): 1315–1325. doi:10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354.

- Carless, D., J. Jung, and Y. Li. 2023. “Feedback as Socialization in Doctoral Education: Towards the Enactment of Authentic Feedback.” Studies in Higher Education. doi:10.1080/03075079.2023.2242888.

- Carter, S., and V. Kumar. 2017. “Ignoring Me is Part of Learning’: Supervisory Feedback on Doctoral Writing.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 54 (1): 68–75. doi:10.1080/14703297.2015.1123104.

- Catterall, J., P. Ross, C. Aitchison, and S. Burgin. 2011. “Pedagogical Approaches That Facilitate Writing in Postgraduate Research Candidature in Science and Technology.” Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice 8 (2).

- Chatterjee Padmanabhan, M., and L. C. Rossetto. 2017. “Doctoral Writing Advisors Navigating the Supervision Terrain.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 54 (6): 580–589. doi:10.1080/14703297.2017.1348961.

- Chugh, R., S. Macht, and B. Harreveld. 2021. “Supervisory Feedback to Postgraduate Research Students: A Literature Review.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 47 (5): 683–697. doi:10.1080/02602938.2021.1955241.

- Clarke, H., and C. Ryan. 2006. “Changing over a Project Changing over: A Project–Research Supervision as a Conversation.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 19 (4): 477–497. doi:10.1080/09518390600773239.

- Cotterall, S. 2011. “Doctoral Pedagogy: What Do International PhD Students in Australia Think about It.” Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities 19 (2): 521–534. doi:10.1080/13562517.2011.560381.

- De Caux, C. 2021. “Doctoral Candidates Academic Writing Output and Strategies: Navigating the Challenges of Academic Writing during a Global Health Crisis Basil.” International Journal of Doctoral Studies 16: 291–317. doi:10.28945/4755.

- Delamont, S., O. Parry, and P. Atkinson. 1998. “Creating a Delicate Balance: The Doctoral Supervisor’s Dilemmas.” Teaching in Higher Education 3 (2): 157–172. doi:10.1080/1356215980030203.

- Devine, K., and K. H. Hunter. 2017. “PhD Student Emotional Exhaustion: The Role of Supportive Supervision and Self-Presentation Behaviours.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 54 (4): 335–344. doi:10.1080/14703297.2016.1174143.

- Ding, Q., and N. Devine. 2018. “Exploring the Supervision Experiences of Chinese Overseas Phd Students in New Zealand.” Knowledge Cultures, 6 (1): 62–78. doi:10.22381/kc6120186.

- Dixon-Woods, M. 2011. “Using Framework-Based Synthesis for Conducting Reviews of Qualitative Studies.” BMC Medicine 9 (1): 39. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-9-39.

- Elliot, D. L., and S. Kobayashi. 2019. “How Can PhD Supervisors Play a Role in Bridging Academic Cultures?” Teaching in Higher Education 24 (8): 911–929. doi:10.1080/13562517.2018.1517305.

- Engebretson, K., K. Smith, D. McLaughlin, C. Seibold, G. Terrett, and E. Ryan. 2008. “The Changing Reality of Research Education in Australia and Implications for Supervision: A Review of the Literature.” Teaching in Higher Education 13 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1080/13562510701792112.

- Evans, C. 2013. “Making Sense of Assessment Feedback in Higher Education.” Review of Educational Research 83 (1): 70–120. doi:https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654312474350.

- Fenwick, T., M. Nerland, and K. Jensen. 2012. “Sociomaterial Approaches to Conceptualising Professional Learning and Practice.” Journal of Education and Work 25 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1080/13639080.2012.644901.

- Fitzpatrick, E., and K. Fitzpatrick. 2015. “Disturbing the Divide.” Qualitative Inquiry 21 (1): 50–58. doi:10.1177/1077800414542692.

- Fullagar, S., A. Pavlidis, and R. Stadler. 2017. “Critical Moments of (Un)Doing Doctoral Supervision: Collaborative Writing as Rhizomatic Practice.” Knowledge Cultures, 5 (4): 23–41. doi:10.22381/kc5420173.

- González-Ocampo, G., and M. Castelló. 2018. “Writing in Doctoral Programs: Examining Supervisors’ Perspectives.” Higher Education 76 (3): 387–401. doi:10.1007/s10734-017-0214-1.

- Gravett, K. 2020. “Feedback Literacies as Sociomaterial Practice.” Critical Studies in Education 63 (2): 261–274. doi:10.1080/17508487.2020.1747099.

- Guerin, C., and I. Green. 2015. “They’re the Bosses’: Feedback in Team Supervision.” Journal of Further and Higher Education, 39 (3): 320–335. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2013.831039.

- Gunnarsson, R., G. Jonasson, and A. Billhult. 2013. “The Experience of Disagreement between Students and Supervisors in PhD Education: A Qualitative Study.” BMC Medical Education 13 (1): 134. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-13-134.

- Halbert, K. 2015. “Students’ Perceptions of a ‘Quality’ Advisory Relationship.” Quality in Higher Education 21 (1): 26–37. doi:10.1080/13538322.2015.1049439.

- Hasrati, M. 2005. “Legitimate Peripheral Participation and Supervising Ph.D. students.” Studies in Higher Education 30 (5): 557–570. doi:10.1080/03075070500249252.

- Hattie, J., and H. Timperley. 2007. “The Power of Feedback.” Review of Educational Research 77 (1): 81–112. doi:10.3102/003465430298487.

- Hemer, S. R. 2012. “Informality, Power and Relationships in Postgraduate Supervision: Supervising PhD Candidates over Coffee.” Higher Education Research & Development 31 (6): 827–839. doi:10.1080/07294360.2012.674011.

- Henderson, M., M. Phillips, T. Ryan, D. Boud, P. Dawson, E. Molloy, and P. Mahoney. 2019. “Conditions That Enable Effective Feedback.” Higher Education Research & Development 38 (7): 1401–1416. doi:10.1080/07294360.2019.1657807.

- Hopman, J. 2021. “Fieldwork Supervision: Supporting Ethical Reflexivity to Enhance Research Analysis.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 44 (1): 41–52. doi:10.1080/1743727X.2019.1706467.

- Hu, Y., K. van Veen, and A. Corda. 2016. “Pushing Too Little, Praising Too Much? Intercultural Misunderstandings between a Chinese Doctoral Student and a Dutch Supervisor.” Studying Teacher Education 12 (1): 70–87. doi:10.1080/17425964.2015.1111204.

- Hu, Y., X. Zhao, and K. van Veen. 2020. “Unraveling the Implicit Challenges in Fostering Independence: Supervision of Chinese Doctoral Students at Dutch Universities.” Instructional Science 48 (2): 205–221. doi:10.1007/s11251-020-09505-6.

- Inouye, K. S., L. McAlpine, and L. Practice. 2017. “Developing Scholarly Identity: Variation in Agentive Responses to Supervisor Feedback.” Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice 14 (2): 35–54. doi:10.53761/1.14.2.3.

- Jackman, P. C., and K. Sisson. 2021. “Promoting Psychological Well-Being in Doctoral Students: A Qualitative Study Adopting a Positive Psychology Perspective.” Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education 13 (1): 19–35. doi:10.1108/SGPE-11-2020-0073.

- Jackson, D., T. Power, and K. Usher. 2021. “Feedback as a Balancing Act: Qualitative Insights from an Experienced Multi-Cultural Sample of Doctoral Supervisors in Nursing.” Nurse Education in Practice 54: 103125. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103125.

- Johnson, C. E., J. L. Keating, and E. K. Molloy. 2020. “Psychological Safety in Feedback: What Does It Look like and How Can Educators Work with Learners to Foster It?” Medical Education 54 (6): 559–570. doi:10.1111/medu.14154.

- Johnson, E. M. 2014. “Doctorates in the Dark: Threshold Concepts and the Improvement of Doctoral Supervision.” 69–81. doi:10.15663/wje.v19i2.99.

- Johnson, M. 2016. “Feedback Effectiveness in Professional Learning Contexts.” Review of Education 4 (2): 195–229. doi:10.1002/rev3.3061.

- Jones, A., and E. Blass. 2019. “The Impact of Institutional Power on Higher Degree Research Supervision: Implications for the Quality of Doctoral Outcomes.” Universal Journal of Educational Research 7 (7): 1485–1494. doi:10.13189/ujer.2019.070702.

- Kamler, B., and P. Thomson. 2014. Helping Doctoral Students Write: Pedagogies for Supervision. London: Routledge.

- Katz, R. 2018. “Crises in a Doctoral Research Project: A Comparative Study [Report].” International Journal of Doctoral Studies 13: 211–231. https://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/A547630757/AONE?u=deakin&sid=AONE&xid=29ca9766. doi:10.28945/4044.

- Kluger, A. N., and A. DeNisi. 1996. “The Effects of Feedback Interventions on Performance: A Historical Review, a Meta-Analysis, and a Preliminary Feedback Intervention Theory.” Psychological Bulletin, 119 (2): 254–284. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.119.2.254.

- Kumar, V., and A. Kaur. 2019. “Supervisory Practices for Intrinsic Motivation of Doctoral Students: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective.” International Journal of Doctoral Studies 14: 581–595. doi:10.28945/4415.

- Kurtz, S., J. Draper, and J. Silverman. 2005. Teaching and Learning Communication Skills in Medicine. Oxford: Radcliffe publishing.

- Lee, A. 2008. “How Are Doctoral Students Supervised? Concepts of Doctoral Research Supervision.” Studies in Higher Education 33 (3): 267–281. doi:10.1080/03075070802049202.

- Leijen, Ä., L. Lepp, and M. Remmik. 2016. “Why Did I Drop out? Former Students’ Recollections about Their Study Process and Factors Related to Leaving the Doctoral Studies.” Studies in Continuing Education 38 (2): 129–144. doi:10.1080/0158037X.2015.1055463.

- Li, S., and C. Seale. 2007. “Managing Criticism in Ph.D. supervision: A Qualitative Case Study.” Studies in Higher Education 32 (4): 511–526. doi:10.1080/03075070701476225.

- Li, Y. 2006. “A Doctoral Student of Physics Writing for Publication: A Sociopolitically-Oriented Case Study.” English for Specific Purposes 25 (4): 456–478. doi:10.1016/j.esp.2005.12.002.

- Li, Y. 2016. “Publish SCI Papers or No Degree”: Practices of Chinese Doctoral Supervisors in Response to the Publication Pressure on Science Students.” Asia Pacific Journal of Education 36 (4): 545–558. doi:10.1080/02188791.2015.1005050.

- Long, A. F., and M. Godfrey. 2004. “An Evaluation Tool to Assess the Quality of Qualitative Research Studies.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 7 (2): 181–196. doi:10.1080/1364557032000045302.

- Maher, D., L. Seaton, C. McMullen, T. Fitzgerald, E. Otsuji, and A. Lee. 2008. “Becoming and Being Writers’: The Experiences of Doctoral Students in Writing Groups.” Studies in Continuing Education 30 (3): 263–275. doi:10.1080/01580370802439870.

- McAlpine, L., and M. McKinnon. 2013. “Supervision – the Most Variable of Variables: Student Perspectives.” Studies in Continuing Education 35 (3): 265–280. doi:10.1080/0158037X.2012.746227.

- Mewburn, I., E. Tokareva, D. Cuthbert, J. Sinclair, and R. Barnacle. 2014. “These Are Issues That Should Not Be Raised in Black and White’: The Culture of Progress Reporting and the Doctorate.” Higher Education Research & Development 33 (3): 510–522. doi:10.1080/07294360.2013.841649.

- Mills, D., and J. Paulson. 2014. “Making Social Scientists, or Not? Glimpses of the Unmentionable in Doctoral Education.” Learning and Teaching 7 (3): 73–97. doi:10.3167/latiss.2014.070304.

- Molloy, E., and M. Bearman. 2019. “Embracing the Tension between Vulnerability and Credibility: ‘Intellectual Candour’ in Health Professions Education.” Medical Education 53 (1): 32–41. doi:10.1111/medu.13649.

- Nguyen, N. T. B., and I. Mushin. 2022. “Understanding Equivocal Feedback in PhD Supervision Meetings: A Conversation Analysis Approach.” Teaching in Higher Education. doi:10.1080/13562517.2022.2068348.

- Nicol, D. J., and D. Macfarlane-Dick. 2006. “Formative Assessment and Self-Regulated Learning: A Model and Seven Principles of Good Feedback Practice.” Studies in Higher Education 31 (2): 199–218. doi:10.1080/03075070600572090.

- Nomnian, S. 2017. “Thai PhD Students and Their Supervisors at an Australian University: Working Relationship, Communication, and Agency.” PASAA: Journal of Language Teaching and Learning in Thailand 53: 26–58.

- Odena, O., and H. Burgess. 2017. “How Doctoral Students and Graduates Describe Facilitating Experiences and Strategies for Their Thesis Writing Learning Process: A Qualitative Approach.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (3): 572–590. doi:10.1080/03075079.2015.1063598.

- Olmos-López, P., and J. Sunderland. 2017. “Doctoral Supervisors’ and Supervisees’ Responses to co-Supervision.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 41 (6): 727–740. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2016.1177166.

- Pope, C., N. Mays, and J. Popay. 2007. Synthesising Qualitative and Quantitative Health Evidence: A Guide to Methods: A Guide to Methods. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Robertson, M. 2017. “Aspects of Mentorship in Team Supervision of Doctoral Students in Australia.” The Australian Educational Researcher 44 (4–5): 409–424. doi:10.1007/s13384-017-0241-z.

- Sadler, D. R. 1989. “Formative Assessment and the Design of Instructional Systems [Journal Article.” Instructional Science 18 (2): 119–144. doi:10.1007/BF00117714.

- Sánchez-Martín, C., and L. Seloni. 2019. “Transdisciplinary Becoming as a Gendered Activity: A Reflexive Study of Dissertation Mentoring.” Journal of Second Language Writing 43: 24–35. doi:10.1016/j.jslw.2018.06.006.

- Schultze, U., and M. Avital. 2011. “Designing Interviews to Generate Rich Data for Information Systems Research.” Information and Organization 21 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.infoandorg.2010.11.001.

- Steen-Utheim, A., and A. L. Wittek. 2017. “Dialogic Feedback and Potentialities for Student Learning.” Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 15: 18–30. doi:10.1016/j.lcsi.2017.06.002.

- Sun, X., and J. Trent. 2020. “Promoting Agentive Feedback Engagement through Dialogically Minded Approaches in Doctoral Writing Supervision.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 59 (4): 387–397. doi:10.1080/14703297.2020.1861965.

- Tai, J., R. Ajjawi, D. Boud, P. Dawson, and E. Panadero. 2018. “Developing Evaluative Judgement: Enabling Students to Make Decisions about the Quality of Work.” Higher Education 76 (3): 467–481. doi:10.1007/s10734-017-0220-3.

- Virtanen, V., J. Taina, and K. Pyhältö. 2017. “What Disengages Doctoral Students in the Biological and Environmental Sciences from Their Doctoral Studies?” Studies in Continuing Education 39 (1): 71–86. doi:10.1080/0158037X.2016.1250737.

- Watling, C., E. Driessen, C. P. van der Vleuten, M. Vanstone, and L. Lingard. 2013. “Beyond Individualism: Professional Culture and Its Influence on Feedback.” Medical Education 47 (6): 585–594. doi:10.1111/medu.12150.

- Wei, J., S. Carter, and D. Laurs. 2019. “Handling the Loss of Innocence: First-Time Exchange of Writing and Feedback in Doctoral Supervision.” Higher Education Research & Development 38 (1): 157–169. doi:10.1080/07294360.2018.1541074.

- Weise, C., M. Aguayo-González, and M. Castelló. 2020. “Significant Events and the Role of Emotion along Doctoral Researcher Personal Trajectories.” Educational Research 62 (3): 304–323. doi:10.1080/00131881.2020.1794924.

- Whitelock, D., D. Faulkner, and D. Miell. 2008. “Promoting Creativity in PhD Supervision: Tensions and Dilemmas.” Thinking Skills and Creativity, 3 (2): 143–153. doi:10.1016/j.tsc.2008.04.001.

- Wisker, G., G. Robinson, V. Trafford, E. Creighton, and M. Warnes. 2003. “Recognising and Overcoming Dissonance in Postgraduate Student Research.” Studies in Higher Education 28 (1): 91–105. doi:10.1080/03075070309304.

- Wisniewski, B., K. Zierer, and J. Hattie. 2019. “The Power of Feedback Revisited: A Meta-Analysis of Educational Feedback Research.” Frontiers in Psychology 10: 3087. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03087.

- Xu, L. 2017. “Written Feedback in Intercultural Doctoral Supervision: A Case Study.” Teaching in Higher Education 22 (2): 239–255. doi:10.1080/13562517.2016.1237483.

- Xu, L., and J. Hu. 2020. “Language Feedback Responses, Voices and Identity (Re)Construction: Experiences of Chinese International Doctoral Students.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 57 (6): 724–735. doi:10.1080/14703297.2019.1593214.

- Xu, L., S. T. Lin, and J. Cai. 2021. “Feedback Engagement of Chinese International Doctoral Students.” Studies in Continuing Education 43 (1): 119–135. doi:10.1080/0158037X.2020.1718634.

- Yang, M., and R. Yuan. 2020. “Early-Stage Doctoral Students’ Conceptions of Research in Higher Education: Cases from Hong Kong.” Teaching in Higher Education 28 (1): 85–100. doi:10.1080/13562517.2020.1775191.