ABSTRACT

In this paper, we focus on the professional agency of student teachers in the initial teacher education context. Based on the ecological model of teacher agency, a questionnaire was developed for a self-reported assessment of student teachers agency in three domains: planning of teaching and learning activities, teaching diverse ability students in the same class, using ICT in teaching. Confirmatory Factor Analysis was used to validate the structure of the instrument in all domains using data from 168 student teachers. The findings confirmed that student-teacher agency could be described through three dimensions (iterational, projective, and practical-evaluative) in all studied domains. In addition, we found, using path analysis, that agency in two domains predicted student-teacher commitment to teaching.

Introduction

Teacher workforce is drawing attention internationally. On the one hand, accumulated research knowledge (Hattie & Yates, 2013) and current profound transformations of education purposes and practices have emphasised the key role of teachers in ensuring high quality and equity of education. On the other hand, many countries are struggling to ensure the sufficient number of qualified teachers who are engaged professionally and committed to stay in the teaching profession. Moreover, several countries are experiencing ageing of teacher workforce and need to act very quickly to motivate already working teachers to continue and to attract potential candidates to join the profession (see e.g. OECD Citation2020). One of such countries is Estonia, where state statistics and international comparisons have informed about this situation for nearly a decade but the numbers are becoming even bleaker year by year (average age of teaches is currently 49, several subjects are taught by nearly a third of teachers who are above 60). Additionally, the recent TALIS report (see OECD Citation2020) showed that 41% of Estonian teachers aged 35 and below are considering leaving the profession in the upcoming 5 years. Although Estonia had the highest share of young teachers who indicated a wish to leave, several other countries who are, similarly to Estonia, known for a strong performance-oriented culture in education such as Singapore, England and the United States reported also high percentages (24% and above) of young teachers indicating to leave the profession. This all despite students of these countries often doing very well in international comparison tests such as PISA. The high number of teachers indicating leaving the profession could be seen as a result or side-effect of neoliberal approaches to education, especially when it is related to rising pressure and demands on teachers to be more productive in terms of student performance. Such approaches have been criticised by scholars in different countries (see e.g. Biesta and Säfström Citation2011; Sleeter Citation2008).

An important question for policymakers is how countries such as Estonia could come out from such an unsustainable situation and ensure a high-quality teaching profession. Priestley, Biesta, and Robinson (Citation2015) suggest we need to search for possibilities to ‘(re)turn teacher agency’ (p. 2). In a broad understanding, agency refers to individuals’ active participation in and shaping of realities and is generally recognised as an important condition for learning and successful functioning in a workplace and other spheres of life (Billett Citation2008). Priestley, Biesta, and Robinson (Citation2015) believe that over a longer timeframe, supporting teacher agency at the individual, cultural, and structural levels is the only sustainable way to maintain everything valuable in education, as well as to make improvements in education. The scope of the current study is the formation of student teachers’ agency that in the Estonian context seems especially important. The aim of this paper is to find out how to measure student-teacher agency and whether and how the agency is related to commitment in teaching.

Teacher agency

In line with the above, increasing attention has been paid to the concept of teacher agency in recent years (see Orland-Barak Citation2017; Toom, Pyhältö, and Rust Citation2015 for an overview). Several empirical studies (see, e.g., Erss Citation2018; Eteläpelto, Vähäsantanen, and Hökkä Citation2015; Kauppinen et al. Citation2020; McNicholl Citation2013; Rajala and Kumpulainen Citation2017; Quinn and Carl Citation2015; Ruan, Zheng, and Toom Citation2020; Stillman and Anderson Citation2015; Van der Heijden et al. Citation2015) have focused on understanding and supporting teacher agency in professional settings. Interest has also increased in supporting student teachers’ agency in initial teacher education context (see, e.g., Juutilainen, Metsäpelto, and Poikkeus Citation2018; Soini et al. Citation2015).

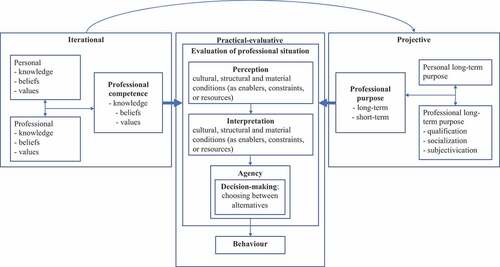

Different studies of student teachers’ agency have utilised different theoretical frameworks. For example, Soini et al. (Citation2015) stress the development of individual student teachers’ abilities which are usually emphasised in the psychological approaches to teacher agency (see. e.g. Bandura Citation2009). Soini and colleagues (ibid) utilised an instrument previously developed for in-service teachers, Teacher’s Sense of Professional Agency survey (TPA) (Pietarinen et al. Citation2013) that focuses on motivation to learn, efficacy beliefs about learning, and intentional acts for facilitating and managing learning in the classroom. Others, e.g. Juutilanen et al. (Citation2018), Lipponen and Kumpulainen (Citation2011) adopt socio-cultural perspective to student-teacher agency development and emphasise mostly the social and contextual factors in developing student teachers’ agency based on their qualitative research studies. Similarly, the ecological model (Leijen, Pedaste, and Lepp Citation2020; Priestley, Biesta, and Robinson Citation2015) adopted in the current study, sees teacher agency primarily as a decision-making process, which is influenced by three dimensions: past histories of the person (iterational dimension), future prospects (projective dimension) and by the cultural, structural and material conditions of a practical situation (practical-evaluative dimension) (see ).

Figure 1. Model of the formation of agency (based on Leijen, Pedaste, and Lepp Citation2020).

What is common in different studies focusing on student teachers (see e.g. Soini et al. Citation2015; Juutilanen et al., Citation2018) is the necessity to address the formation of teacher agency throughout the teacher education programmes (especially with respect to the initial education of teachers) in parallel to their learning of professional knowledge and competences. In other words, as Soini et al. (Citation2015, 642), point out: ‘ … student teachers’ sense of professional agency is not about giving a lecture, organising extra courses or training periods about a certain topic; instead, it needs to be facilitated throughout teacher education, starting from the first days of teacher studies’. This implies that teacher education programs need to have a clear vision and integrated action plan regarding how to support student teachers’ agency throughout their studies. This might entail that in addition to learning content knowledge and pedagogical knowledge and skills, student teachers are also supported to develop self-knowledge (Fairbanks et al. Citation2010), explore the relationship and fit between their professional and personal competences and purposes (Anspal, Leijen, and Löfström Citation2019; Leijen, Kullasepp, and Toompalu Citation2017), and to practice decision-making related to different pedagogical situations which relate directly to their agency development. Moreover, horizontal relations between peers (e.g. fellow teachers at school or students at university) seem to be strong structural facilitators for agency development (see e.g. Juutilainen, Metsäpelto, and Poikkeus Citation2018; Priestley, Biesta, and Robinson Citation2015) and for this reason, peer learning activities could be implemented more readily to support agency development.

Having in mind the important role of the teacher agency in contemporary studies of teacher education, it implies a need for developing of the solid instrument for assessing and monitoring student teachers’ agency dynamics throughout their initial education. Although the concept of agency in teacher education has been explored from different perspectives, there are only limited questionnaires (e.g. Jääskelä et al. Citation2017; Soini et al. Citation2015) currently available for studying teacher agency. Within the ecological approach adopted in the current study, according to our best knowledge, there are no instruments available that could be utilised by teacher educators to monitor student teachers’ agency formation. Consequently, the first aim of this study was to develop a questionnaire for a self-reported assessment of teacher agency in the teacher education context. Moreover, considering the need to support teacher commitment to teaching, the second aim of this study is to find out to what extent student teachers’ agency in different domains could predict their commitment to teaching.

Below we will describe the ecological model of teacher agency, explain how commitment to teaching was operationalised in the current study, and present the research questions of the current study.

Ecological model of teacher agency

Following the ecological model, agency is understood ‘as something individuals or groups can manage to achieve’ (Priestley, Biesta, and Robinson Citation2015, 3). Agency results from ‘the interplay of an individual’s capacities and environment conditions’ (ibid.). The attainment of agency is therefore influenced by individual efforts, resources, and cultural and structural factors and we cannot view agency as mere characteristic or property of an individual (Biesta, Priestley, and Robinson Citation2015). Moreover, the ecological model (Leijen, Pedaste, and Lepp Citation2020; Priestley, Biesta, and Robinson Citation2015) encompasses three dimensions: iterational, projective, and practical-evaluative (see ), which help to understand the achievement of agency. Iterational dimension refers to the activation of accumulated knowledge and experience base from the past. This contains personal life histories of an individual teacher and also knowledge, attitudes, and knowhow resulted from the socialisation to the teaching profession. Related to this dimension, teacher education programs often include assignments that encourage student teachers to integrate their personal and professional identities to be able to feel content, act self-confidently in professional practice and consequently stay longer in teaching profession (Beijaard, Meijer, and Verloop Citation2004; Leijen, Kullasepp, and Toompalu Citation2017). In a way, iterative dimension of agency guards for stability in teacher’s actions. Projective dimension contains short-term and long-term future purposes which allow shaping actions in line with actor’s possible future trajectories. Thus, guarding for potential change in teacher’s actions. Related to this dimension, teacher education programs often include assignments related to formulating professional vision or purpose (Feiman-Nemser Citation2001). Practical-evaluative dimension entails engaging with cultural, structural, and material conditions, which can act as enablers, constraints, or resources for teachers’ actions. Horizontal relations and close ties among teachers as well as student teachers can function as enablers of agency, while performance-oriented culture and hierarchical relations among people can act as constrains for teacher agency (Priestley, Biesta, and Robinson Citation2015). A (student) teacher achieves agency when she/he can consider alternatives and is able to judge which option would be the most appropriate in a given practical situation in light of her/his greater professional purpose. ‘Agency is not present if there are no options for action or if the teacher simply follows routinized patterns of habitual behaviour with no consideration of alternatives’ (ibid., p. 141). The above described also implies that agency is domain-specific. A (student) teacher can have more agency related to some aspects of his/her work and less agency with others.

Commitment to teaching

The commitment to teaching is defined as a psychological attachment or bond to the teaching profession (Coladarci Citation1992; Firestone and Pennell Citation1993) indicating the degree to which the teacher values and feels connected to the profession (see e.g. Berger & Lê Van, Citation2019; Lamote and Engels Citation2010). Increasing interest in this area is motivated by educational policy concerns related to attracting and sustaining high-quality teachers in several countries. Since teachers can feel committed towards different aspects of their profession, Lauermann et al. (Citation2017) advised to consider multiple indicators of commitment such as ‘(1) commitment to teaching as a long-term career (inferred from planned persistence in teaching and career choice satisfaction), (2) interest in professional development as an indicator of professional engagement, and (3) willingness to invest personal time for teaching-related tasks (e.g., to help students)’ (p. 323). They argued that this allows to consider the commitment to teaching as a career as also suggested by Watt and Richardson (Citation2008) and as the willingness to be engaged in professional tasks. Lauermann et al. (Citation2017) utilised this approach in studying commitments to teaching among student teachers who participated in a teacher education programme in the USA. Their sample contained teachers with varying degree of teaching experiences (from no teaching experience to experiences with in-service teaching).

Prior research shows that commitment to teaching is related to different teacher-level variables. For example, teachers with higher self-responsibility and self-efficacy tend to be more strongly committed to their profession (see e.g. Klassen and Chiu Citation2011; Lauermann et al. Citation2017; Ware and Kitsantas Citation2007). Moreover, intrinsic and social utility motivation for teaching are related to commitment to teaching (Watt and Richardson Citation2007; Lauermann et al. Citation2017). Research on school-level variables has indicated that teacher collective efficacy, faculty trust, and participation in professional learning communities are also related to commitments to teaching (Lee, Zhang, and Yin Citation2011). These findings suggest that (student) teacher agency, which is an interplay of individual capabilities and environmental conditions, would be positively related to commitments to teaching.

Current study

Based on the ecological model of agency, a questionnaire (see Appendix 1) was developed to capture student teachers’ agency in three domains: planning of teaching and learning activities, teaching diverse ability students in the same class and using ICT in teaching. These distinct areas were selected because agency is domain-specific and these domains represent different important aspects of today’s teachers’ work. Planning of teaching and learning activities could be understood as traditionally important activity teachers need to carry out. Teaching diverse ability students and utilising ICT in teaching could be understood as recently increasing demands describing teachers’ work in many countries. Firstly, we were interested to evaluate the psychometric properties of the developed questionnaire. Following, the first research question was formulated: Which factors could be empirically specified in characterising the formation of teacher agency according to the ecological model of agency?

Secondly, we were interested to get an overview of the student teachers’ commitment to teaching and their agency in three domains. The second research question directed to find out: How student teachers report their commitment to teaching and agency in three domains and how these related to diverse kind of teaching experience?

Thirdly, we were also interested to find out whether we could predict commitment to teaching based on the student teacher’s agency in the three domains in order to validate the hypothesis that teacher agency is an important condition for the commitment to teaching (Priestley, Biesta, and Robinson Citation2015). Consequently, the third research question was formulated: To what extent could commitments to teaching be predicted based on student teachers’ agency in different domains?

Methods

Data collection and sample

Data were collected electronically from 168 student teachers (72% of a cohort) in one Estonian university. One cohort of teacher education students (233 student teachers in total) who followed a course in teacher education base module was invited to participate in the study which utilised several instruments including agency and commitment to teaching questionnaires. All students of this course were contacted and students who participated in the study received an additional 4% of points of the course result. Participation was voluntary and students who decided not to participate could also receive 100% for their course result. Prior to participation, informed consent was received from the students. Participants’ teaching experience varied from no experience (N = 54) to experiences with in-service teaching (N = 114), experience ranging from 1 month to 28 years. Thirty-nine teachers had experience up to 1 year, 36 teachers between one to 5 years, and 39 teachers six or more years. Although teacher qualification is expected from teachers in Estonia, not all teachers who work at school are qualified to teach. Due to the shortage of teachers, it is possible to hire an unqualified teacher in case there are no qualifying candidates. School leaders can hire unqualified teachers for 1 year, this contract can be prolonged on a yearly basis. Very often such teachers would enrol in initial teacher education programs to earn a master’s degree and teacher qualification. In addition, some student teachers learn for their second degree, for example, if they are qualified as kindergarten teachers or teacher in a particular subject but would like to learn to become a teacher in another subject or educational level. Thirty-seven respondents were bachelor level students and 131 master level students. Thirty-six students studied to become kindergarten teachers, 11 class teachers, 101 subject teachers, and 20 studied to become vocational education teachers. Among student teachers participating in the study, 153 respondents were female and 13 male students.

Measures

Student-teacher agency

A questionnaire (see Appendix 1) was developed to capture student-teacher agency in three domains: planning of teaching and learning activities, teaching diverse ability students in the same class, using ICT in teaching. The questionnaire was developed by the authors of the paper following the ecological model of teacher agency. Questionnaire statements were composed to represent each of the three dimensions of the model. Regarding each dimension, we identified key aspects describing this dimension. In case of iterational dimension, we considered teachers’ knowledge base in the broad sense and highlighted competence, values, and beliefs, in case of projective dimension we focused on professional and personal long- and short-term purposes, and in case of practical-evaluative dimension cultural, structural, and material conditions. In the case of structural conditions, two categories of support were identified. For each key aspect, one statement was formulated. The developed instrument was a self-report questionnaire where respondents had to evaluate agreement with each statement on a 7-point Likert type scale. Psychometric properties of the questionnaire in three domains are reported in the results section. Internal consistency of the scales was high varying from .88 to .91 for the agency scales and from .77 to .91 for the sub-scales of the agency in different domains.

Commitments to teaching

were investigated with two subscales. Firstly, commitment to teaching as a career was assessed by two previously reported items (Lauermann et al. Citation2017; Watt and Richardson Citation2007): How sure are you that you will persist in a teaching career? How satisfied are you with your choice of becoming/being a teacher? Since the scale included only two items, the third item was developed for this study to increase validity of the measure: How sure are you that you want to work as a teacher also in the future? Respondents were asked to rate how much they agree with each statement on a scale from 1 (Not at all) to 7 (Very much). Secondly, willingness to invest personal time (Lauermann et al. Citation2017) that contained the following items: On a scale of 1 (None) to 7 (Most of it), how much of your PERSONAL time are you willing to invest … i) … to work with students?; ii) … to improve your teaching?; iii) … to help students?; iv) … to communicate with parents?; v) … to prepare good lessons? The Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the commitments to teaching scale confirmed the two-factor structure of the theoretical model (χ2/df = 1.83, RMSEA = .070, CFI = .990, TLI = .984, SRMR = .057). Two latent factors were specified – willingness to invest personal time and commitment as a career – that were only moderately correlated (.342). Internal consistency for the scale of willingness to invest personal time was .92 and for the scale of commitment to teaching as a career was .95.

Data analysis

The theoretical model of agency in three domains and commitments to teaching were tested using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). The model was considered acceptable if the fit indices were the following (see Bowen and Guo Citation2011): root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤ .05, comparative fit index (CFI) ≥ .95 and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) ≥.95. We also used Standardised Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) with the suggested value below .08 and the normed chi-square index with an acceptable value below 3 and good value below 2 (see Kline Citation1998; Ullman Citation2001). The comparison of descriptive statistics was done using non-parametric analyses because most of the variables did not have normal distribution according to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Therefore, the paired comparisons of agency in different domains were conducted using Wilcoxon Signed Rank test and comparisons between different groups of students using Kruskal–Wallis test and relations between different variables were found using Spearman Rank Order correlation. Path-analysis was used to predict different factors of commitments to teaching. Path-analysis was conducted using the factor scores of latent variables describing different identified dimensions of agency in three domains. The statistical program Mplus (Version 7.4) was used for testing the multidimensional factor model and running the path analysis.

Results

1. Confirmatory factor analysis of the teacher agency in three domains

The CFA showed that the ecological model of agency can be described through three dimensions as proposed by Leijen, Pedaste, and Lepp (Citation2020) and Priestley, Biesta, and Robinson (Citation2015) – iterational, projective and practical-evaluative (see ) in all three domains. Some correlations were allowed between a few items based on their content (see Appendix 1). Correlations were allowed between items 3 and 4 because these both were based on the actor’s experience. Items 2 and 8 were allowed to correlate because these focused both on the actor’s professional values although from different viewpoints – studies and purpose. Items 8 and 9 were correlated because these were both about organisation culture although in projective and practical-evaluative dimensions, respectively (something is valued in teaching and organisational culture supports it). Two of the items were left out from the model since these did not fit with the model. Item 1 stressed the importance of personal life experiences related to the domain and item 7 stressed the importance of personal aims related to the domain. All other items (see Appendix 1) were formulated more neutrally without the emphasis of personal importance.

Figure 2. Correlated factor models of student teachers agency in three domains: in teaching diverse ability students in the same class (left, χ2/df = 2.09, RMSEA = .081, CFI = .973, TLI = .958, SRMR = .054), in planning of teaching and learning activities (middle, χ2/df = 1.32, RMSEA = .043, CFI = .992, TLI = .988, SRMR = .045), in utilising ICT in teaching (right, χ2/df = 1.57, RMSEA = .058, CFI = .987, TLI = .979, SRMR = .052; v = domain of teaching diverse ability students in the same class, k = domain of planning teaching and learning activities, it = domain of utilising ICT in teaching, iter = iterational, proj = projective, prac = practical-evaluative).

The final models in the domains of planning of teaching and learning activities and utilising ICT in teaching were with very good fit and the model in the domain of teaching diverse ability students was with the close fit (see fit indices in ). Iterational and projective dimension were highly correlated (> .90) in case of all domain-specific models as expected based on the theoretical model.

We also tested if the agency could be described according to a unidimensional, bifactorial or second-order factor model; however, all unidimensional and bi-factor models were with the worse fit. In case of second-order factor models, the fit indices were the same as in case of the correlated factors model but the residual of one factor was negative in case of two out of three dimensions and therefore this model was not confirmed (see comparative table with fit indices of all models in Appendix 2). Therefore, the path-analysis was conducted using the factor scores calculated in correlated factors model distinguishing three factors.

2. Overview of the student teachers’ agency in three domains and commitment to teaching

The descriptive statistics of student teachers’ agency and commitments to teaching are presented in . The results show that student teachers have the highest agency in planning of teaching and learning activities and the lowest in case of teaching diverse ability students in the same class. The domain-specific differences are all also statistically significant (based Wilcoxon signed ranks test). The differences in the level of dimensions on agency seem to be domain-specific. For example, in case of agency in teaching diverse ability students in the same class, student teachers reported a lower level of competency and experience (iterational dimension) as well as the lower level of purposes (projective dimension) compared to the student-teacher evaluation of environmental constraints (practical-evaluative) to teach diverse ability students. In contrast, in case of agency related to utilising ICT in teaching, the students feel themselves competent and experience and they have a supportive environment, but they do not seem to have clear purposes of using ICT in teaching. In case of planning of teaching and learning activities, all three dimensions are nearly on the same level.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of student teachers’ (n = 168) agency and commitments to teachinga.

The commitment of teaching is described only on the level of two dimensions distinguished in the factor analysis because the items in these dimensions are measured on different scales. Indeed, it is notable that student teachers have very high willingness to invest personal time in teaching but do not have so strong vision regarding commitment to teaching as a career (on average 78% and 65% of the maximum score, respectively).

We also analysed if the student teachers with different teaching experience (with no teaching experience, with up to 1 year of experience, with up to 5 years, and with six and more years of experience) had significantly different agency or commitments to teaching. The analysis revealed statistically significant differences in agency in the domain planning of teaching and learning activities (Kruskal–Wallis H = 8.20, Mean rank for student teachers with no experience 78.3, for the ones with up to 1 year of experience 74.5, for the ones with up to 5 years of experience 84.7, and for the ones with six and more year experience 103.0). It shows that the agency in planning might slightly decrease during the first year at school but starts to increase with experience. The analysis of the level of sub-scales revealed that these differences appear in the iterational and projective dimensions of agency but not in the practical-evaluation dimension. For the other two domains of agency, no statistically significant difference was found in relation to experience.

If we looked at the correlation between the number of years of teaching practice and agency, then we found that there is a weak but statistically significant positive correlation between experience and agency in planning of teaching and learning activities (ρ = .168, p < .05). This positive relation was also found in two of the dimensions of planning related agency – in iterational and projective (ρ = .215, p < .01 and ρ = .289, p < .01, respectively). It shows that with experience, teachers improve their competences and purposes related to planning. In the case of utilising ICT in teaching the correlation was negative but only marginally statistically significant (ρ = −.137, p = .077). It shows that the teacher education students who do not have yet any teaching experience tend to have more agency in using ICT for teaching. Correlation between teaching experience and agency in teaching diverse ability students in the same class were very low and not statistically significant (ρ = .059, p > .1) showing that agency in this domain has not been influenced by practice. Interestingly, low but statistically significant correlations were also found between student teachers’ age and agency in planning and utilising ICT in teaching (ρ = −.156, p < .05 and ρ = −.184, p < .05, respectively). In both cases, the older teachers have lower agency. In case of commitments to teaching the only statistically significant relation was found between experience and commitment to teaching as a career (ρ = −.169, p < .05). In this case, the students with teaching experienced had a higher probability to continue working as a teacher although the correlation was quite low.

3. Relationships between teacher agency and commitment to teaching

The path analysis was carried out to understand how teacher agency is related to their commitments to teaching. For this analysis, we used factor scores of agency in three domains. Path analysis was selected because of the rather small sample for a structural equation model with many parameters. We ran two analyses because of the high correlation between the latent variables of iterational and projective dimension of agency. Commitment to teaching was predicted through two dimensions because their correlation was rather low in the CFA. The models predicted variance of willingness to invest personal time by 19% and planned persistence by 16–17%. The results (see ) were rather similar in predicting commitments to teaching in using either iterational and practical-evaluative or projective and practical-evaluative dimensions of agency.

Figure 3. Path analysis models predicting two dimensions of teachers commitment to teaching (time = willingness to invest personal time, career = commitment to teaching as a career) based on factor scores describing dimensions of agency (it = iterational, pro = projective, par = practical-evaluative) in three domains (plan – planning of teaching and learning activities, it = utilising IT in teaching, incl = teaching diverse ability students in the same class).

In the case of agency in planning of teaching and learning activities both iterational and projective dimensions predicted statistically significantly commitment to teaching as a career (regression .222 and .239, respectively). It shows that with increasing competencies and experience in planning as well as in case of clearer professional purpose related to planning the student teachers’ probability to commit to teaching as a career increases. However, a very interesting finding was revealed regarding willingness to invest personal time. The regression of both iterational and projective dimension of planning related agency was negative (−.262 and −.290, respectively). This shows that by increasing agency in planning, the teacher tends to invest less personal time on teaching activities. The practical-evaluative dimension of planning related agency predicted neither of the dimensions of commitment to teaching.

Agency related to teaching diverse ability students in the same class predicted statistically significantly student teachers willingness to invest personal time in teaching-related activities. However, in contrast to planning related agency, this effect was as expected positive. The student teachers with higher agency tend to invest more personal time in teaching-related activities. This relation was at a very similar level in case of all agency dimensions – in iterational (regression .222), projective (regression .220) and in case of one model also practical-evaluative dimension (regression .227).

Finally, the agency in utilising ICT in teaching tended not to have an effect on the commitment to teaching. None of agency dimensions had a statistically significant regression on either willingness to invest personal time on teaching-related activities or commitment to teaching as a career.

Discussion

The results of the study suggest that the developed questionnaire is suitable for studying student-teacher agency in a reliable and valid way since we could confirm previously proposed three dimensions of agency (Leijen, Pedaste, and Lepp Citation2020; Priestley, Biesta, and Robinson Citation2015) in all three investigated domains. The final questionnaire consists of 10 items, three in iterational and projective and four in the practical-evaluative dimension of agency. Each item is assessed on a 7-point Likert type scale. For adapting the questionnaire to different domains items need to be adapted slightly. This gives a high level of flexibility to use the same instrument in many domains. The developed questionnaire is therefore suitable for studying student-teacher agency in the university setting and could be used in other contexts as well as an addition to already existing instruments (e.g. Jääskelä et al. Citation2017; Soini et al. Citation2015).

The results also indicated very interesting findings regarding student-teacher agency in different domains. Students reported the highest agency related to planning of teaching and learning activities, which is expected since it is traditionally (see e.g. Clark & Peterson, Citation1986), but also nowadays one of the core activities of teachers’ work and consequently teacher education programs are paying a lot of attention to this area. We found statistically significant differences between student teachers with different teaching experience, whereas less experienced teachers had lower agency than more experienced teachers. More specifically, we found that gaining teaching experiences is positively related to two dimensions of planning related agency which target accumulated competences and professional purposes. These findings are very well aligned with previous research which shows that in comparison to beginners, experienced teachers are much more confident and competent when planning teaching and learning activities (see e.g. Koni and Krull Citation2018; Lui and Bonner Citation2016). Lowest agency among student teachers was reported regarding teaching diverse ability students in the same class. On a wider perspective, this activity is related to the implementation of inclusive education. As shown by recent TALIS survey, this is an area of concern and needs further professional development in many TALIS countries (OECD Citation2020). Moreover, some countries, including Eastern Europe and former Soviet countries are experiencing bigger challenges (Kivirand et al. Citation2020; Stepaniuk Citation2018). Due to the past histories of educational systems and teacher education programmes in many of these countries, teacher preparation has not paid sufficient attention to how to teach students with special educational needs together with their peers in an inclusive setting. Teacher education programs in Estonia have only recently started to pay more attention to this area; however, the approach is still fragmented. A big challenge for the initial education in Estonian is how to address inclusive education coherently throughout the whole teacher education program. Taken this background into account, it is not surprising that agency in this domain is lower than in two other domains that were in the focus of our study, and it is not surprising that gain of teaching experience is not related to an increased agency in this domain since many teachers in Estonia are not historically used to teach students with special educational needs in their classes. We also investigated teachers’ agency related to using ICT for teaching and learning. Owing to educational policy initiatives in this area and overall ICT-mindedness in Estonian society, we expected that agency in this area is relatively high and younger student teachers who are used with ICT-rich environments have higher agency in this domain. In addition, the latter assumption was based on the findings of the OECD PIAAC study, according to which younger people in Estonia have significantly higher skills to solve problems in ICT rich environment (Halapuu and Valk Citation2013). Although agency in this area was relatively high, student teachers evaluated their competences and environmental conditions higher than their purposes related to using ICT for teaching and learning. This might point to an important shortcoming in their preparation, it seems that they are competent to use ICT and have conditions to do so but have not carefully considered its purposes. This is despite that many scholars and educators have often stressed that pedagogy should always proceed technology while making decisions related to implementing ICT in education (see e.g. Pedaste & Leijen, Citation2018; Stephenson Citation2018 for a recent overview).

Interesting results were also revealed regarding the relationships between agency and commitment to teaching. We found that only planning related agency predicted student teachers’ commitment to teaching as a career. More specifically, a higher agency of two dimensions of planning related agency, competence and purposes, predicted student teachers’ commitment to teaching as a career. This shows that agency in planning teaching and learning activities seems to be more central than the other two other domains while forming a long-term commitment to teaching career. The other area of commitment to teaching, willingness to invest personal time, were predicted by agency related to planning and teaching diverse ability students. However, the directions of the relationships were somewhat unexpected. Across all three dimensions, the higher level of agency related to teaching diverse ability students predicted higher use of personal time, as expected. Contrary, a higher level of competence and purposes related to planning predicted lower willingness to use personal time. These findings are probably mediated by the domain-specific requirements. Teaching diverse ability students might indeed require more time from teachers to carefully prepare and carry out teaching, while better purposes and skills in planning might indeed protect from spending too much personal time for professional activities. In any case, these findings suggest that the two domains of commitment to teaching used in the current study behave differently in different areas of analysis and another instrument might be needed to capture the more universal character of commitment to teaching. This could be a valuable goal for further study.

The results also revealed that agency in three domains predicted commitment to teaching in different degrees, while agency in one area did not predict commitment to teaching at all. Although all of the studied domains are important in different teacher education policy guidelines in many countries they might not have captured the most crucial areas of teachers work in terms of a long-term commitment to teaching. The studied three domains are all mostly related to general pedagogy, further studies should focus on areas related to subject didactics or pedagogical content knowledge as well.

Finally, we would like to pinpoint and discuss some potential limitations of the developed agency questionnaire. Studying student teachers’ agency is a relatively new field of research and within the ecological approach adopted in the current study, there were no instruments previously available. In this context we decided to develop a more general instrument with a robust conceptual framework. We showed that the properties of the questionnaire are acceptable. However, the formulation of items might be somewhat too general making us wonder whether we would get similar findings if items are formulated in a more specific way. For example, in the current version we have a general question about long-term purposes of a teacher, but we do not specify different long-term goals (see, for example, Biesta Citation2009). Therefore, future studies should focus on a comparison between instrument consisted of items formulated at the general level and instrument consisted of items that are formulated in a more specific way.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (23.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Äli Leijen

Äli Leijen is a Professor of Teacher Education, her main research themes are teachers’ professional development, supporting metacognitive processes in different contexts, and using ICT for supporting teaching and learning. ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5708-3837Margus Pedaste is Professor of Educational Technology, his main research themes are educational technology, science education, inquiry-based learning, technology-enhanced learning and instruction, and learning analytics. ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5087-9637

Aleksandar Baucal is Professor of Psychology, his main research topics are development of competences in education and sociocultural studies of learning and development. ORCID ID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7965-7659

References

- Anspal, T., Ä. Leijen, and E. Löfström. 2019. “Tensions and the Teacher’s Role in Student Teacher Identity Development in Primary and Subject Teacher Curricula.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 63 (5): 679–695. doi:10.1080/00313831.2017.1420688.

- Bandura, A. 2009. “Agency.” In Encyclopaedia of the Life Course and Human Development: Volume II Adulthood, edited by D. S. Carr, 8–11, Macmillan Reference.

- Beijaard, D., P. C. Meijer, and N. Verloop. 2004. “Reconsidering Research on Teachers’ Professional Identity.” Teaching and Teacher Education 20 (2): 107–128. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2003.07.001.

- Berger, J.-L., and K. L. Van. 2019. “Teacher Professional Identity as Multidimensional: Mapping Its Components and Examining Their Associations with General Pedagogical Beliefs.” Educational Studies 45 (2): 163–181. doi:10.1080/03055698.2018.1446324.

- Biesta, G. 2009. “Good Education in an Age of Measurement: On the Need to Reconnect with the Question of Purpose in Education.” Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability 21 (1): 33–46. doi:10.1007/s11092-008-9064-9.

- Biesta, G., M. Priestley, and S. Robinson. 2015. “The Role of Beliefs in Teacher Agency.” Teachers and Teaching 21 (6): 624–640. doi:10.1080/13540602.2015.1044325.

- Biesta, G., and C. A. Säfström. 2011. “A Manifesto for Education.” Policy Futures in Education 9 (5): 540–547. doi:10.2304/pfie.2011.9.5.540.

- Billett, S. 2008. “Learning Throughout Working Life: A Relational Interdependence Between Personal And Social Agency.” British Journal of Educational Studies 56 (1): 39–58. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8527.2007.00394.x.

- Bowen, N. K., and S. Guo. 2011. Structural Equation Modeling. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Clark, C.M. and Peterson, P.L. (1986). Teachers’ Thought Processes. In: Wittrock, M.C., Ed., Handbook of Research on Teaching, 3rd Edition, Macmillan, New York, 255-296.

- Coladarci, T. 1992. “Teachers Sense of Efficacy and Commitment to Teaching.” The Journal of Experimental Education 60 (4): 323–337. doi:10.1080/00220973.1992.9943869.

- Erss, M. 2018. “‘Complete Freedom to Choose within Limits’ – Teachers’ Views of Curricular Autonomy, Agency and Control in Estonia, Finland and Germany.” The Curriculum Journal 29 (2): 238–256. doi:10.1080/09585176.2018.1445514.

- Eteläpelto, A., K. Vähäsantanen, and P. Hökkä. 2015. “How Do Novice Teachers in Finland Perceive Their Professional Agency?” Teachers and Teaching 21 (6): 660–680. doi:10.1080/13540602.2015.1044327.

- Fairbanks, C. M., G. G. Duffy, B. S. Faircloth, Y. He, B. Levin, J. Rohr, and C. Stein. 2010. “Beyond Knowledge: Exploring Why Some Teachers are More Thoughtfully Adaptive than Others.” Journal of Teacher Education 61 (1–2): 161–171. doi:10.1177/0022487109347874.

- Feiman-Nemser, S. 2001. “From Preparation to Practice: Designing a Continuum to Strengthen and Sustain Teaching.” Teachers College Record 103 (6): 1013–1055. doi:10.1111/0161-4681.00141.

- Firestone, W. A., and J. R. Pennell. 1993. “Teacher Commitment, Working Conditions, and Differential Incentive Policies.” Review of Educational Research 63 (4): 489–525. doi:10.3102/00346543063004489.

- Halapuu, V., and A. Valk. 2013. Täiskasvanute Oskused Eestis Ja Maailmas: PIAAC Uuringu Esmased Tulemused. Haridus- ja Teadusministeerium [Adult skills in Estonia and in the world: preliminary results of the PIAAC survey. Tartu, Estonia: Ministry of Education and Research].

- Hattie, J., and G. Yates. 2014. Visible Learning and the Science of How We Learn. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315885025.

- Heijden, H. V. D., J. Geldens, D. Beijaard, and H. Popeijus. 2015. “Characteristics of Teachers as Change Agents.” Teachers and Teaching 21 (6): 681–699. doi:10.1080/13540602.2015.1044328.

- Jääskelä, P., A.-M. Poikkeus, K. Vasalampi, U. M. Valleala, and H. Rasku-Puttonen. 2017. “Assessing Agency of University Students: Validation of the AUS Scale.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (11): 2061–2079. doi:10.1080/03075079.2015.1130693.

- Juutilainen, M., R.-L. Metsäpelto, and A.-M. Poikkeus. 2018. “Becoming Agentic Teachers: Experiences of the Home Group Approach as a Resource for Supporting Teacher Students Agency.” Teaching and Teacher Education 76: 116–125. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2018.08.013.

- Kauppinen, M., J. Kainulainen, P. Hökkä, and K. Vähäsantanen. 2020. “Professional Agency and Its Features in Supporting Teachers’ Learning during an In-service Education Programme.” European Journal of Teacher Education 1–21. doi:10.1080/02619768.2020.1746264.

- Kivirand, T., Ä. Leijen, L. Lepp, and L. Malva. 2020. “Kaasava Hariduse Tähendus Ja Tõhusa Rakendamise Tegurid Eesti Kontekstis: Õpetajaid Koolitavate Või Nõustavate Spetsialistide Vaade [The Meaning of Inclusive Education and Factors for Effective Implementation in the Estonian Context: A View of Specialists Who Train or Advise Teachers].” Eesti Haridusteaduste Ajakiri (Estonian Journal of Education) 8 (1): 48–71. doi:10.12697/eha.2020.8.1.03.

- Klassen, R. M., and M. M. Chiu. 2011. “The Occupational Commitment and Intention to Quit of Practicing and Pre-service Teachers: Influence of Self-efficacy, Job Stress, and Teaching Context.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 36 (2): 114–129. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.01.002.

- Kline, R. B. 1998. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York: Guilford Press.

- Koni, I., and E. Krull. 2018. “Differences in Novice and Experienced Teachers’ Perceptions of Planning Activities in Terms of Primary Instructional Tasks.” Teacher Development 22 (4): 464–480. doi:10.1080/13664530.2018.1442876.

- Lamote, C., and N. Engels. 2010. “The Development of Student Teachers’ Professional Identity.” European Journal of Teacher Education 33 (1): 3–18. doi:10.1080/02619760903457735.

- Lauermann, F., S. Karabenick, R. Carpenter, and C. Kuusinen. 2017. “Teacher Motivation and Professional Commitment in the United States: The Role of Motivations for Teaching, Teacher Self-Efficacy and Sense of Professional Responsibility.” In Global Perspectives on Teacher Motivation (Current Perspectives in Social and Behavioral Sciences), edited by H. Watt, P. Richardson, and K. Smith, 297–321. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781316225202.011.

- Lee, J. C.-K., Z. Zhang, and H. Yin. 2011. “A Multilevel Analysis of the Impact of A Professional Learning Community, Faculty Trust in Colleagues and Collective Efficacy on Teacher Commitment to Students.” Teaching and Teacher Education 27 (5): 820–830. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2011.01.006.

- Leijen, Ä., K. Kullasepp, and A. Toompalu. 2017. “Dialogue for Bridging Student Teachers’ Personal and Professional Identity.” In The Dialogical Self Theory in Education: A Multicultural Perspective (Cultural Psychology of Education, edited by F. Meijers and H. Hermans, 97–110. Vol. 5. Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-62861-5_7.

- Leijen, Ä., M. Pedaste, and L. Lepp. 2020. “Teacher Agency Following The Ecological Model: How It Is Achieved And How It Could Be Strengthened By Different Types Of Reflection.” British Journal of Educational Studies 68 (3): 295–310. doi:10.1080/00071005.2019.1672855.

- Lipponen, L., and K. Kumpulainen. 2011. “Acting as Accountable Authors: Creating Interactional Spaces for Agency Work in Teacher Education.” Teaching and Teacher Education 27 (5): 812–819. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2011.01.001.

- Lui, A. M., and S. M. Bonner. 2016. “Preservice and Inservice Teachers Knowledge, Beliefs, and Instructional Planning in Primary School Mathematics.” Teaching and Teacher Education 56: 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2016.01.015.

- McNicholl, J. 2013. “Relational Agency and Teacher Development: A CHAT Analysis of A Collaborative Professional Inquiry Project with Biology Teachers.” European Journal of Teacher Education 36 (2): 218–232. doi:10.1080/02619768.2012.686992.

- OECD. 2020. TALIS 2018 Results (Volume II): Teachers and School Leaders as Valued Professionals. Paris: TALIS, OECD Publishing.

- Orland-Barak, L. 2017. “Learning Teacher Agency in Teacher Education.” In The SAGE Handbook of Research on Teacher Education, edited by D. J. Clandinin and J. Husu, 247–252, Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington DC, Melbourne: Sage.

- Pedaste, M., and Ä. Leijen. 2018. “How Can Advanced Technologies Support the Contemporary Learning Approach?” In IEEE 18th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT), edited by M. Chang, N.-S. Chen, R. Huang, K. K. Moudgalya, S. Murthy, and D. G. Sampson, 21–23. Los Alamitos, California, Washington, Tokyo: IEEE Computer Society.

- Pietarinen, J., K. Pyhältö, T. Soini, and K. Salmela-Aro. 2013. “Reducing Teacher Burnout: A Socio-contextual Approach.” Teaching and Teacher Education 35: 62–72. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2013.05.003.

- Priestley, M., G. Biesta, and S. Robinson. 2015. Teacher Agency: An Ecological Approach. London: Bloomsbury Academic. doi:10.5040/9781474219426.

- Quinn, R., and N. M. Carl. 2015. “Teacher Activist Organizations and the Development of Professional Agency.” Teachers and Teaching 21 (6): 745–758. doi:10.1080/13540602.2015.1044331.

- Rajala, A., and K. Kumpulainen. 2017. “Researching Teachers’ Agentic Orientations to Educational Change in Finnish Schools.” Professional and Practice-Based Learning Agency at Work 20: 311–329. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-60943-0_16.

- Ruan, X., X. Zheng, and A. Toom. 2020. “From Perceived Discrepancies to Intentional Efforts: Understanding English Department Teachers’ Agency in Classroom Instruction in a Changing Curricular Landscape.” Teaching and Teacher Education 92: 103074. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2020.103074.

- Sleeter, C. 2008. “Equity, Democracy, and Neoliberal Assaults on Teacher Education.” Teaching and Teacher Education 24 (8): 1947–1957. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2008.04.003.

- Soini, T., J. Pietarinen, A. Toom, and K. Pyhältö. 2015. “What Contributes to First-year Student Teachers’ Sense of Professional Agency in the Classroom?” Teachers and Teaching 21 (6): 641–659. doi:10.1080/13540602.2015.1044326.

- Stepaniuk, I. 2018. “Inclusive Education in Eastern European Countries: A Current State and Future Directions.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 23 (3): 328–352. doi:10.1080/13603116.2018.1430180.

- Stephenson, J. 2018. Teaching & Learning Online: New Pedagogies for New Technologies. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315042527.

- Stillman, J., and L. Anderson. 2015. “From Accommodation to Appropriation: Teaching, Identity, and Authorship in a Tightly Coupled Policy Context.” Teachers and Teaching 21 (6): 720–744. doi:10.1080/13540602.2015.1044330.

- Toom, A., K. Pyhältö, and F. O. C. Rust. 2015. “Teachers’ Professional Agency in Contradictory Times.” Teachers and Teaching 21 (6): 615–623. doi:10.1080/13540602.2015.1044334.

- Ullman, J. B. 2001. “Structural Equation Modeling.” In Using Multivariate Statistics, edited by B. G. Tabachnick and L. S. Fidell, 653–771. 4th ed. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Ware, H., and A. Kitsantas. 2007. “Teacher and Collective Efficacy Beliefs as Predictors of Professional Commitment.” The Journal of Educational Research 100 (5): 303–310. doi:10.3200/joer.100.5.303-310.

- Watt, H. M., and P. W. Richardson. 2008. “Motivations, Perceptions, and Aspirations Concerning Teaching as a Career for Different Types of Beginning Teachers.” Learning and Instruction 18 (5): 408–428. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2008.06.002.

- Watt, H. M. G., and P. W. Richardson. 2007. “Motivational Factors Influencing Teaching as a Career Choice: Development and Validation of the FIT-Choice Scale.” The Journal of Experimental Education 75 (3): 167–202. doi:10.3200/jexe.75.3.167-202.