ABSTRACT

In early 2020, Initial Teacher Education providers were forced to reimagine many long-established practices due to pandemic restrictions. One post-primary concurrent Initial Teacher Education programme in the Republic of Ireland responded by conceptualising and developing an initiative to engage pre-service teachers in an authentic assessment task through the preparation of a classroom-based assessment from the perspective of the pupil. They then engaged in peer review and peer feedback on these classroom-based assessments and partook in a Subject Learning and Assessment Review meeting. This required the professional development of assessment literacies on the part of pre-service teachers, as well as disturbing their personal assessment beliefs at a cognitive and affective level. This paper finds that the collaborative assignment experience challenged pre-service teachers’ previous conceptions about the purposes of assessment while providing them with insight and preparation for formative assessment processes in use throughout Irish post-primary schools.

Introduction

In March 2020, Initial Teacher Education (ITE) providers around the world were presented with a momentous challenge of reconceptualising many of their long-established practices with regard to teaching, learning, and assessment, as a result of the implications and rapidly imposed restrictions arising from the global COVID-19 pandemic (Mutton Citation2020). Darling-Hammond offers three critical components of Initial Teacher Education programmes:

tight coherence and integration among courses and between coursework and clinical work in schools, extensive and intensely supervised clinical work integrated with course work using pedagogies that link theory and practice, and closer, proactive relationships with schools that serve diverse learners effectively and develop and model good teaching

The Irish context

The professional education of pre-service teachers in Ireland can be undertaken through two routes. The first option is a concurrent undergraduate ITE programme, which generally takes 4 years. The second option is to complete a level eight undergraduate degree and then follow this by completing a postgraduate degree, called the Professional Master of Education (PME). The PME takes 2 years. The focus of this paper is on the first option and the preparation of the pre-service teachers in their role as assessors for post-primary (secondary) schools where pupils generally range in age from 12 to 19. Assessment in Ireland at lower secondary level has undergone a huge transformation from a focus on a very high stake summative assessment called the ‘Junior Certificate’, which was marked and set by a government agency called the ‘State Examination Commission’ (SEC), to the integration of a dualistic approach, both formative and summative (NCCA Citation2015). The move to formative assessment is captured in the work of Birenbaum et al. (Citation2015) who map the emergence and implications of formative assessment in countries across the globe. In Ireland, the role of the teacher as assessor had been in flux since the introduction of a new framework for lower secondary education called the ‘Junior Cycle’ (NCCA Citation2012). This framework sets out not only a new pedagogical approach to teaching and learning but also presented teachers with a number of changes to assessment. This challenged the traditional role of the State Examinations Commission (SEC) as the sole assessor of state examinations. One of the new assessment components is called the classroom-based assessment (CBA) to be marked using four standards that describe performance and a set of Features of Quality and examples of students’ work at the different levels. The CBA was originally a construct of Michael Scriven’s (Citation1967) work but is recently defined by Lewkowicz and Leung as ‘any teacher-led classroom activity designed to find out about students’ performance on curriculum tasks that would yield information regarding their understanding as well as their need for further support and scaffolding with reference to their situated learning needs’ (2001 48). The CBA was to be reported not as a grade but as a separate set of descriptors on the student’s report called the ‘Junior Cycle Profile of Achievement’ (NCCA Citation2021).

Furthermore, the experience of the cancellation of the senior cycle terminal examination (Leaving Certificate Examination) in 2020 and 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic thrust Irish teachers into an assessment arena that they had fought hard to oppose. The Leaving Certificate Calculated Grades 2020 and Leaving Certificate Accredited Grades 2021 compelled teachers into marking and ranking their students for the high stakes state examinations at senior cycle (Doyle, Lysaght, and O’Leary Citation2021). The Senior Cycle Review (NCCA Citation2019) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Review of Senior Cycle in Ireland (Citation2020) highlighted the ongoing challenge of how assessment drives teaching, learning, and curriculum reform. The OECD warned that this ‘impact is such that any changes made to the senior cycle will have limited possibilities to succeed if the current assessment approaches are not reviewed accordingly’ (OECD Citation2020, 2). From the perspective of the teacher educator, it was clear that a new era of teachers’ engagement with assessment was emerging and the role of ITE should prepare the pre-service teacher to engage critically in these changes. Pre-service teachers’ own past experience of formative assessment was very limited due to the Leaving Certificate experience (A. MacPhail, Halbert, and O’Neill Citation2018). It was therefore important for ITE to disturb their summative approach to assessment in the present and expand their knowledge, craft, and art (Pollard Citation2010) in the forms of assessment offered by the new curriculum called ‘The Junior Cycle Framework’ at lower secondary. It was also our intent to prime pre-service teachers for future senior cycle assessment reform.

Teacher assessment identity

Any attempt to define teacher identity immediately runs into major difficulties as it is a highly contested and complex space. It draws from a multiplicity of disciplines: sociology, philosophy, psychology, anthropology, and education, and has evolved over a very long timeframe (Biesta Citation2015; Cooley Citation1902; Erikson Citation1959; Jenlink Citation2021; Mockler Citation2011; Thomas and Beauchamp Citation2007; Vygotsky Citation1986). In planning for the development of pre-service teachers’ identity, our focus was on the advice from Beijaard, Meijer, and Verloop (Citation2004) who highlighted the ongoing process of evolution in a teacher’s understanding of their teacher identity. It emerges through the interplay between a teacher’s personal ethnography and past narrative, their professional experience, their relationships and socio-cultural context (Kelchtermans Citation2009; Marschall Citation2022). Time takes on a cyclical dimension as their future career as a teacher is impacted by their past and present narratives. Pishgadam, Golzar, and Miri (Citation2022) expands this understanding and explains that we have moved from a core, inner, fixed linear construct to a dynamic, multifaceted, context-dependent, dialogical, and intrinsically related phenomenon.

Literature offers multiple frameworks which try to capture this complex emergence of teacher identity, and many focus on the importance of the personal histories and narratives that a teacher brings with them to Initial Teacher Education (Marschall Citation2022). Pre-service teachers are immersed in learning about being a teacher and how professionalism works in various different sites of practice (Kelchtermans Citation2009). The socio-cultural contexts of the university, school, and classroom interplay with the personal and professional and engage the pre-service teacher with a confrontation about their beliefs and feelings about education and pedagogy. Olsen’s definition of teacher identity as ‘a complex mélange of influences and effects in which macro- and micro-social histories, contexts, and positionings combine with the uniqueness of any person to create a situated, ever-developing self that both guides and results from experience’ (2001 259) aligns with our understanding in this paper.

One area of teacher identity that has moved on the fringes of teacher education is the role of the teacher as assessor (Stiggins Citation1988; Young, MacPhail, and Tannehill Citation2022). In many ITE programmes, the focus is often on developing the pedagogy of teaching, and knowledge and understanding of assessment can be limited (Atjonen et al. Citation2022). Over the years, literature has offered many different models that assist in understanding the complexities involved in developing teacher assessment identity. Herppich et al. offer a competence-oriented conceptual model and define competences to be ‘context-specific, learnable cognitive dispositions that are needed to successfully cope with specific situations’ (Citation2018, 181). They highlight the importance of incorporating into their model, research on assessment products (i.e. judgements), on assessment processes and practices, as well as their quantification. Whilst this model offers excellent insights for the teacher educator, it focuses mainly on cognitive dispositions that are specifically related to assessment. We favoured a model that also integrated the affective and ontological aspects of assessment identity (Pryor and Crossouard Citation2010) and therefore drew on Looney et al.’s conceptions of assessment which supports the inclusion of not only knowledge and skills but also beliefs and feelings in ‘a dynamic and interactive teacher assessment identity’ (Citation2018, 14). Looney et al. (Citation2018) argue that teachers may have knowledge and confidence but do not believe that assessment processes are effective. Teachers can also have mixed feelings about assessment and may consider some processes or interactions as not part of their role. Their model draws from the framework proffered by Xu and Brown (Citation2016) which proposes a hierarchy of seven components of building the teacher as assessor: The knowledge Base; Interpretive and Guiding Framework; Teacher Conceptions of Assessment; Macro socio-cultural and micro-institutional contexts; Teacher Assessment Literacy in Practice; Teacher Learning; and Assessor Identity (Re)construction. Xu and Brown (Citation2016) argue that the cognitive dimension denotes what teachers believe to be true about assessment: teachers will respond to new knowledge if it is consistent with their current conceptions and reject the ones that are not. The affective dimension denotes the feelings or emotional disposition that teachers have about various aspects of assessment and its uses. These feelings can be deeply held by the teacher and have been charged by previous experience (Lutovac and Assunção Flores Citation2022). Xu and Brown explain that ‘the emotional dimension of conceptions may make conceptual change difficult, leading to less effective learning about assessment and reduced effectiveness in implementing new assessment policies’ (Citation2016, 21). They also highlight the collective and individualised nature of teachers’ conceptions about assessment and the importance of engaging with both beliefs and feelings throughout their professional development.

Whilst Xu and Brown (Citation2016) clarified important considerations for our approach to assessment, such as the knowledge base and the combination of teacher conceptions of assessment and putting this into practice, we considered that the re-conceptualisation of Teacher Assessment Identity (TAI) by Looney et al. (Citation2018) supported the multifaceted and dynamic interplay between the cognitive and affective dimensions of the role of the assessor that we were trying to achieve. TAI is modelled less on a pyramid style (Yueting and Brown Citation2016) and more on the confluence of a number of significant conceptions. Looney et al. (Citation2018) highlight the importance of assessment literacy under the heading of ‘I know’. Under ‘I feel’ they wish to integrate the degree to which teachers’ feel in control of their assessment practice in a particular school system at any point in time (Douwe, Meijer, and Verloop Citation2004). Under the ‘My role’ - what is it that I do as an assessor – they draw on the complexity of the agency of the teacher in their role as assessor and the multiple judgements, perspectives, and interpretations that are encountered. They also suggest that the beliefs of a teacher, ‘I believe’, have been developed from their past experiences of assessment and shape their present dispositions. Finally, they identify self-efficacy – ‘I am confident’ -as connecting to classroom actions by drawing from Dellinger, Bobbett, and Ellett who define it as ‘individual beliefs in their capabilities to perform specific teaching tasks at a specified level of quality in a specified situation’ (Citation2008, 4). Looney et al. (Citation2018) posit that teachers’ identity as professionals, beliefs about assessment, disposition towards enacting assessment, and perceptions of their role as assessors are all significant for their assessment work. Each of these components intertwines and overlaps each other, and it is from this interplay that teacher assessment identity emerges.

It is our contention that when teachers assess more is in play than simply knowledge and skills. They may have knowledge of what is deemed effective practice, but not be confident in their enactment of such practice. They may have knowledge, and have confidence, but not believe that assessment processes are effective. Most importantly, based on their prior experiences and their context, they may consider that some assessment processes should not be a part of their role as teachers and in interactions with students. Teachers can, quite literally, have mixed feelings about assessment.

Re-imagining a more authentic assessment for pre-service teachers

This paper maps how staff of one post-primary concurrent ITE programme in the Republic of Ireland offered a multifaceted authentic or real-life assessment (Villarroel et al. Citation2018) for pre-service teachers to assist them in developing their teacher assessment identity. This authentic assessment was part of their response to the lack of sites of practice for their pre-service teachers during COVID-19 restrictions. The team conceptualised and developed TOP, the Teaching Online Programme, an initiative to introduce PSTs to the theory and practice of synchronous and asynchronous online teaching, learning, and assessment, via a structured and tutor-supported online peer-teaching experience (Enda et al. Citation2022). Underpinning TOP was the decision to prioritise the development of the PST’s identity as assessors (Doyle, Lysaght, and O’Leary Citation2021). A core objective of TOP was to place assessment in a central position of what it meant to be an effective and professional teacher and an intrinsic part of teaching and learning. The team recognised the complexity of its task to foster the development of teachers who not only had a developed assessment literacy (Yueting and Brown Citation2016) but who were committed cognitively and affectively to making judgements and decisions to improve student learning (Looney et al. Citation2018). The programme did not just wish to fill the gap of sites of practice for PSTs but to take the opportunity to realise the integration of teacher assessment identity as a significant component in the development of the teacher (Smith Citation2016).

The team, drawing on the re-conceptualisation of teacher assessment identity proposed by Looney et al. (Citation2018), looked at the recent changes to assessment philosophy, processes, and practices proposed by the new Junior Cycle curriculum at lower secondary. We noted that the Teaching Council (Citation2020a), the regulatory body for the teaching profession in the Republic of Ireland, had observed the need of the PST to be exposed, where feasible, to engaging classes in the completion of the classroom-based assessment. The PST rarely had the opportunity to engage with this type of assessment on their school placement. Now with COVID-19 restrictions, they had no possibility of getting that opportunity. This opened us up a new threshold of entry to integrating the role of the assessor into our programme.

Teaching Online Programme (TOP)

In TOP, the PST prepared units of learning (previously named schemes of work), which included synchronous and asynchronous lessons, on the learning outcomes underpinning a Junior Cycle CBA in Religious Education (RE). The Religious Education CBA asks a second-year lower secondary student to research and report on a person of commitment whose religious beliefs or worldview have had a positive impact on the world, past and present. An intensive programme was developed (TOP EdTech) for PSTs to develop the technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge (Punya and Koehler Citation2006) necessary for teaching and engaging in online settings; see Donlon et al. (Citation2022) and Doyle et al. (Citation2021) for further details. The current paper is focussed on how the setting of an assignment in semester one on the Religious Education CBA scaffolded and modelled learning for the PST so that their beliefs and feelings about formative and summative assessment and how it works within their classroom were disturbed and challenged to view assessment as more than certification (Herppich et al. Citation2018).

The authentic assessment

Part 1: designing a CBA from the perspective of post-primary second-year students

In collaborative groups of six, PSTs took on the role of second-year lower secondary pupils and responded to the Religious Education CBA by designing a report on a person of commitment. This report could be in any media form. The skill of working as a team and building a professional community of learning (Turner et al. Citation2018) was encouraged so that they would experience first-hand the power of learning in a collaborative group but also experience the challenges of teamwork. Each group had to decide on what person of commitment they would research and how they would present their report. They were given the four descriptors (Exceptional; Above Expectations; In line with expectations; Yet to meet expectations) and the Features of Quality as success criteria for the task. Through their engagement in the process, each PST built their understanding of the challenges a student encounters in choosing a person of commitment, dividing the workload with their group and keeping to deadlines. They experienced insights into the scaffolding and support needed to progress and expand the students’ ability to enquire, explore, reflect and research. They were challenged to rethink the importance of how the CBA allows for diverse interpretations, inclusion of all students, and how to build a universal design for learning (Rose and Meyer Citation2002).

Part 2: peer-evaluation of the CBA

Each group uploaded their report to the university’s Virtual Learning Environment (VLE). They were now asked to switch roles to that of teacher and to individually mark four of the uploaded CBAs using the descriptors and features of quality. They were supported in this through lectures and workshops on understanding the standards necessary for each descriptor and how to engage in giving feedback from the Quality Criteria and rubrics. The focus for the PST was to put aside bias (Allal Citation2013) and to grade the learning that had taken place in this CBA. These individual judgements of standards were then uploaded to the VLE, along with feedback on each CBA.

Part 3: the subject learning and assessment review meeting

While still in teacher roles, each group now convened together in what is called an SLAR (Subject Learning and Assessment Review) meeting. Each group video recorded their meeting as they discussed the four CBAs and the standards they had offered as individual teachers. Importantly, they also had to discuss the learning that was needed in order to carry out this CBA and the scaffolding that would be offered by the teacher in their future teaching of this unit of learning. They were asked to come to an ‘on balance’ judgement based on the features of quality of that piece of work. The group then prepared further formative feedback on the CBAs they had assessed. Marks were adjusted accordingly.

Part 4: self-evaluation and reflection

PSTs were asked to write a 500-word reflection on the learning they had gained through the assignment and how it would impact their approach to developing their units of learning for TOP. They were asked to consider the formative and summative assessment checkpoints needed during the 4 weeks of teaching synchronous and asynchronous lessons.

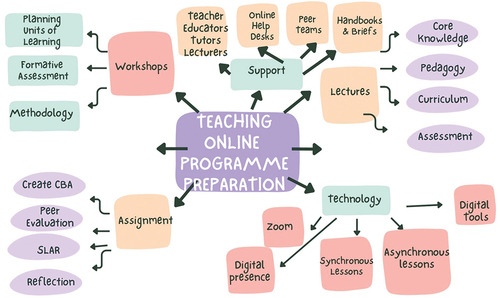

highlights the different support offered to the PST for TOP and where the authentic assignment sits into the overall programme.

Methodology

Our focus was to challenge PSTs’ previous thinking about assessment and cause them to revisit their pre-existing beliefs and feelings about the purposes of assessment while providing them with insight and preparation for formative assessment processes. On foot of approval from the University’s Research Ethics Committee (DCUREC/2021/008) data were collected from third-year PSTs. As the empirical component of this study took place during heightened national restrictions around travel and congregation due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the preferred methods for data collection (questionnaires and focus groups) were enacted via online means. Phase one of data collection began with students invited via an open email invitation to participate in an online questionnaire, which contained both open and closed questions. Online questionnaires have been noted for their ability to reach participants from a wide geographical area and for achieving quick returns (Lefever, Dal, and Matthíasdóttir Citation2007) which proved attractive in the light of ongoing pandemic restrictions at the time. Forty-nine responses were received from the cohort of 86 PSTs that were invited to participate. At the end of the online survey, participants were invited to click on a web link and enter their contact details in a separate form (thus preserving the anonymity in place for the online survey) if they were willing to engage in phase two of the study; this resulted in 12 students volunteering to partake in focus group interviews. The sample did not take account of demographic variables such as gender or age; the only common factor was that all were third-year students on the undergraduate ITE programme in question. Focus groups were chosen as a data collection method for their acknowledged ability to elicit a range of views, perspectives, or understandings of an issue, and because the interactions between participants can give rise to elaborated and detailed accounts (Braun and Clarke Citation2013). These focus groups were conducted using Zoom, an approach for undertaking qualitative research which has seen much utilisation and favourable experience during the pandemic (Wallace, Goodyear-Grant, and Bittner Citation2021). Following Lobe’s (Citation2017) advice to keep synchronous online focus groups relatively small in size, PST participants were divided into three groups of four participants. Participants were assigned a pseudonym at the outset (e.g. FG3C) and used these throughout the interviews, with each focus group interview lasting between 45 and 60 min. Respondent validation (member checking) was utilised through sharing of the anonymised focus group transcripts with the group participants (Birt et al. Citation2016) prior to analysis.

The resultant transcripts from the focus groups and the open-ended responses from the online surveys were then imported into NVivo for analysis. Data analysis was conducted by one member of the team in order to enhance consistency across the full dataset, and thus while inter-coder reliability was not required (C. MacPhail et al. Citation2016) a number of cross-checks of samples and decisions around coding took place as part of a weekly meeting of the project team with a view to contributing to trustworthiness. Data were coded using Thematic Analysis, which was chosen for its acknowledged suitability in identifying patterns across a dataset which can include data obtained from multiple methods – in our case, focus groups (Braun and Clarke Citation2013) and open-ended responses as part of online surveys (Braun et al. Citation2021). The first round of coding identified two overarching themes within the data: (1) ‘professional identity’ (students developing their professional identity) and (2) ‘the module’ (comments around the module). These were then sub-divided into sub-themes through two further rounds of coding. For instance, the initial theme of ‘professional identity’ gave rise to 14 sub-themes which included ‘teaching methods’, ‘professional identity as assessor’, and ‘planning for student learning’. In some cases, these sub-themes were further devolved into more specific sub-themes – see (below) for a snapshot of this for theme 1 (professional identity) and sub-theme 1.1 (teaching methods), taken from the project codebook:

Table 1. Sample of themes and sub-themes, extracted from project codebook.

For illustrative purposes, one example of data coded as ‘1.1.2 Collaborative Assessment (SLAR)’ is as follows:

FG3D:[18:23] As 3A said, it was different working as part of the groups and would give you an idea of the SLAR meeting. Also, it would help to provide justification and I found that when looking back one of my justifications was a bit weak compared to others. So, it gave me a better understanding of how I should be kind of approaching it

Trustworthiness of the research was enhanced through member-checking the focus group transcripts, the use of NVivo for analysis of the data, the use of multiple sources of data for triangulation, regular project meetings, and the careful compilation of a research audit trail (Elo et al. Citation2014).

Findings

In our promotion of a collaborative authentic assessment, across data from the focus groups and questionnaires, it was clear that engagement with a CBA is a complex process made up of a multiplicity of components. One pre-service teacher captured the voices of their classmates when they stated that ‘having a better understanding and knowledge of it has made me more confident in assessing it because I now know the required components of the CBA (Pre-service Teacher Questionnaire’ (PSTQ). Participants spoke about the CBA task itself and how it ‘put me in the mindset of the student completing a CBA’ (PSTQ). It helped them understand how they could support their students’ learning throughout the process: ‘I did feel like that was beneficial to get a student’s perspective and then into the teachers’ role’ (PSTQ). Data confirmed that through engagement in the CBA process, the pre-service teacher recognised the importance of what they were learning for their students, and it constantly placed them in the shoes of their students so that they began to ask questions such as ‘what did I learn from that’? (PSTQ). Initially, not all pre-service teachers welcomed the assignment and it challenged their beliefs and feelings about what this assessment was trying to do:

At the time, I thought it was irrelevant to make us do one because of how busy we were with all of our modules and preparation but it actually helped me immensely in regards to teaching placement

The CBA task

The CBA task challenged the pre-service teacher’s knowledge and understanding:

… .and it was only really when you got into working it and doing it, that a lot of what we were being asked to do made sense. It was hard because we had no conception of it beforehand and to really understand what they were asking us to do, it was only as you went through the process

The participants noted that in the roll out of the new Junior Cycle, this was the first time that any teacher in Ireland had engaged with the Religious Education CBA, and thus it was new territory for both pre-service teachers, teacher educators, and teachers. The assignment allowed them to recognise the intricacy of the CBA task and the challenge ‘in terms of building an understanding of what was required actually, because I think you can miss things yourself and then to hear somebody else’s voice that really kind of helps your understanding’ (FG3B). There was an acknowledgement that engaging with the task assisted with building the self-efficacy of the PST through knowledge and understanding, but also gaining an insight into the roles played by the teacher and student in an assessment process: ‘it has made me intimately aware of the process involved, the workload of students and teachers and the assessment format’ (PSTQ).

PSTs recognised that traditional sites of teacher placement would not have offered the chance to ‘delve into the CBAs in as much detail’ (FG3E) and ‘because now I know the full inside and out of how I would do a CBA’ (FG3F), and so they know ‘how to guide students through this process’ (PSTQ). There was a growing awareness amongst the pre-service teachers that this assessment process demanded the development of many skills and competences that they had not previously thought about: ‘I think this year it has really sunk in just how many skills are required, how many ways of thinking on different fronts are needed at the same time’ (FG3G).

Within the CBA process, pre-service teachers highlighted how the task challenged their understanding of how to present a report beyond pen and paper. They discovered how ‘the use of technology and the different approaches that can be used, with a large variety available’ (PSTQ), can open up more creative and innovative experiences of learning. The introduction to the complexity of assessing creativity and the skills that underpin it gave one pre-service teacher pause to think about the unpredictability of what a student might produce in the CBA:

I think the creativity side of it … how do you teach creativity? How do you assess creativity? But it’s actually such a skill that is developed throughout your life, you know, and I think to be doing it early on with students, you don’t know what they’re going to come out with, do you know what I mean?…So, I think bringing all those strengths together I think is a really powerful kind of side, the CBA that’s not tested in a summative approach

Evaluating the CBA

PSTs had to individually evaluate four CBA reports using Features of Quality and apply a descriptor to the report. They described how working through the Features of Quality offered them the opportunity to gain insight into the process of evaluating a piece of work: ‘it has shown me there are different ways in approaching a CBA and that the four features of quality are a good guideline in relation to being an assessor’ (FG3D).

One PST’s questionnaire response captured their surprise that Features of Quality even existed:

Yeah, it definitely built my understanding a bit more in terms of there’s a prescribed template that you have to work towards instead of just looking at a piece of work and then going based solely on your own opinion, you know your own intuition or viewpoint of what is good, bad or indifferent … I didn’t really realise that at the start. So, I thought they were good to have these as a base

However, the process of evaluating brought many challenges to the fore, and they highlighted the difficulty of bias, standards, and concerns about the fallout in their relationships. In relation to bias, the participants noted that ‘I think it did help to awaken if you had a bias because it was not your preference but if they had done the job well’ (PSTQ). The fact that they knew the people they were evaluating, some of whom were their friends, encouraged them to address these feelings and work to put these aside and focus on the assignment. They will have to do a similar movement with marking students’ assignments in the future and bring their focus away from the affective side to the actual assignment alone.

I was questioning the idea of … because I knew some of the people who actually made the CBAs and you know you can get your heart strings pulled because you’re like, ‘oh I don’t want to give that person a particular mark’ or ‘I feel weird if I give them a very high mark because I know them and I don’t want to be biased’ but …

Pre-service teachers recognised that

it would be the same in a classroom if you get on particularly well with a student and you think well, I know they worked really hard but at the end of the day have they actually met the criteria

I found that was actually the biggest challenge for me. I didn’t mind working in the groups but having to assess each other you know you were putting yourself out on the line there even with your own group

The real question of whether this assessment might affect their future relationships because ‘you’re good friends with these people and you don’t want to … judge’ (FG3C) brought them right into the complexity of feelings in relation to assessing those you have a relationship with. For others, they had a different perspective and reported ‘It was actually quite fun in that sense because nobody was taking anything personally and it was very much focused on the work and I thought it was a great experience’ (FG3G).

There was evidence in data that there was an awakening understanding of standards and at times the complexity of applying these levels.

I think for me actually conducting the CBA made me think more about what I would expect from my students or any CBA that I was assessing, the kind of level that I would expect them to have in each aspect of it in order to receive each descriptor

At times, they found the four Features of Quality not detailed enough, and they had to contemplate what criteria made up each descriptor:

One thing that we did find as a whole group was kind of how broad the grading rubric was … .but just in general trying to use it was quite difficult because there’s three sections for each descriptor and you might have a CBA that meets a broad expectation in terms of their research but then their reflection doesn’t even meet ‘In line with expectations’. We struggled to kind of decide where does that fall, do you have to bring it the whole way down to ‘In line with expectations’ or can you put it somewhere in between

The question of standards also came into play in relation to the fact that the CBAs were examples of Third Level pre-service teachers’ work. Some of the participants found this challenging at first as they expected the standard of the work to be very high: ‘we had 3rd level examples of the CBAs and it was hard to evaluate how that would actually correlate to second year students, what should be expected from them’. Despite the expectation that they had that their peers’ CBA reports would all meet ‘Above Expectations’ or ‘Exceptional’, and ‘are going to be good, and everybody should have met a decent level in their CBA’ (FG3E), this was not the reality and many were evaluated at ‘In line with expectations’. The process of evaluating highlighted to the pre-service teachers’ components in the task that they had not observed or focussed on:

I found that there were things that we missed as a group and that didn’t appear … .but you could see it was great to have made a few mistakes because then you could go back and show students, look, this is a CBA example but there’s stuff missing

The Subject Learning and Assessment Review Meeting (SLAR)

The recorded SLAR meeting was reported by pre-service teachers to be the most beneficial to them in their role as assessors.

The process of evaluating the CBAs as a team at the SLAR meeting, based on the descriptors, was very helpful in understanding how to measure the success of the work in meeting the descriptors. It helped to identify the areas we missed as a team in producing a CBA and therefore fed into the understanding of the process for teaching

One of the highlights for them was being able to understand where your standards were in relation to others in the group: ‘the SLAR meeting element really helped with the assessment in the sense that it helped you to gauge yourself against other people and how they assess’ (FG3G). The whole process of being part of a group and assessing as a group was particularly helpful for participants who thought it was:

quite complex in nature because people are giving their opinions and you need to respect their opinions when they are grading the piece. To absorb that idea of like, will I compromise to a certain degree and that use of teamwork was quite good and also to see actually how CBAs are graded for when we were going into school, I thought that was quite beneficial

Added to this, pre-service teachers reported that listening to others, hearing different arguments for different selections of levels, and having to contribute to the discussion assisted in helping each person ‘keep in line with what I was missing’ (PSTQ) and ‘fed into the understanding of the process for teaching’ (PSTQ). Some of the discussions were ‘heated’ (PSTQ) as the group were ‘very opinionated’ (PSTQ) but most groups agreed that they were ‘able to come to a fair and concise decision on each CBA’ (PSTQ) and ‘it was a good experience to do because we were teachers in a semi-live situation’ (PSTQ).

Repeatedly, participants were noticing the application of this assignment to their practice in the classroom and this encouraged them to be able to justify their descriptor decisions:

It would help to provide justification and I found that when looking back one of my justifications was a bit weak compared to others. So, it gave me a better understanding of how I should be approaching it or what details I should be looking out for when correcting it along with following the guidelines

The SLAR meeting also gave participants insights as to how it ‘was just helpful to understand the way people approach CBAs’ (PSTQ) and the influence of areas of interest such as their elective subjects in the reports. They emphasised that their students would be able to tap into their own interests and allow them a freedom that summative assessment would not usually allow:

So, it really did pull upon strengths in terms of, if you’re into art and you focus on the aesthetics side in CBA and you were putting in visuals … .So, I think bringing all those strengths together I think is a really powerful kind of side of the CBA that’s not tested in a summative approach

Working in a team

The support of the group for the pre-service teacher in this time of isolation (as a result of COVID-19 restrictions) was notable:

The most rewarding aspect was probably having a very supportive and encouraging group to work with. As we are all working from home and not seeing our peers or any students, it was always nice to have the assigned group to touch base with them

One difficulty described was working with a team that was clearly ‘unmotivated, disinterested and doing the bare minimum to get by’ (PSTQ) and this ‘made the hard worker extremely frustrated’ (PSTQ). Another comment portrays the clear purposes of assessment held by some pre-service teachers who value an assignment by the grade they will receive: ‘there were members of my group who weren’t interested in creating the CBA as it was “not worth any marks”. This left me with a huge workload and didn’t allow us to properly experience the process’ (PSTQ). For the first iteration of this assignment, the pre-service teacher did not receive a standalone grade for this assignment, but it was included in the overall mark for their placement. The TOP team wished to disturb their valuing of what is measured alone. However, over the following years, the team recognised the significant work that the pre-service teachers put into this assignment and its ongoing merits, and thus now 20% of their grade for TOP is given to this assignment. Finding time to meet on Zoom, other work pressures, coping in one’s own life, and working with opinionated people all added to the challenge of teamwork.

Reflection

Pre-service teachers reflected on the learning this assignment had offered them. Interestingly, they had little to report on this element of the assignment and as one pre-service teacher argued: ‘reflecting on the CBA can be difficult when you are working by yourself in an online space’ (PSTQ). From the assignment, it was evident that they found reflection on their learning difficult to navigate and will need further scaffolding in the future. Some of their reflections commented on how ‘it has allowed me to develop my critical thinking skills and has given me experience in grading CBAs’ (PSTQ) and another PST reported:

The CBA process, in relation to being an assessor, has greatly contributed to my teaching career. Having an active and practical assignment here, allowed me to see what it is going to be like when I have to grade real CBAs. It also showed me how to work when in a SLAR meeting, how to get points across, analyse other teachers’ decisions, working as a team, etc

It helped them realise the complexity of assessing in relation to the workload, the format of the assessment, and even the development of the multiple skills for both teacher and students. It also challenged many of the pre-service teachers’ thoughts, beliefs, and feelings about assessment:

So, I think the role of the teacher and we were always being told how important it is, but I think this year it has really sunk in just how many skills are required, how many thinking on different fronts at the same time

One important insight gained from this assignment was the recognition of what the formative assessment process entailed in engaging with the CBA and the support and scaffolding it offers each student: ‘it allows for formative feedback to be given on a daily or weekly basis, so each student is constantly improving in all types of standards. It is also inclusive’ (PSTQ).

Discussion

The findings above offer many important insights on the complexity of developing a pre-service teacher’s assessment identity and in particular challenging their beliefs and feelings about assessment. TAI is a continuum of growth, affected by not only policies and the various sites of practice for the pre-service teacher but by personal experiences both past and present (Day et al. Citation2006). Connelly and Clandinin (Citation1999) describe this identity as the narratives that teachers create to explain themselves and their work. The challenge that ITE providers face is to create a space whereby the narratives that the pre-service teacher tells themselves about effective teaching and learning include the integration of the importance of assessment and its purposes. To take on this challenge, the current paper argues that:

The centralising of assessment, alongside teaching and learning, within the ITE programme assists in comprehending the complexity of the purposes of assessment.

Authentic assessment assignments offer a process for disrupting and problematising assessment beliefs and feelings of pre-service teachers.

Peer collaboration is an important tenet in developing TAI.

These are now discussed further.

The centralising of assessment

Initial Teacher Educators across the world confront many opportunities and challenges in relation to building a programme that encourages the emergence of a professional teacher whose focus is on students’ education (Biesta Citation2014) and achievement (Steinmayr et al. Citation2014). Amidst the multiplicity of influences, the importance of comprehending the significance of TAI (Looney et al. Citation2018) is emerging as an essential component of PSTs’ development. The centralising of TAI encourages the deciphering of not only the purposes of assessment (Young, MacPhail, and Tannehill Citation2022) and assessment literacy (Yueting and Brown Citation2016), but also (and especially) how the beliefs and feelings of teachers function in making pedagogical judgements and decisions in the classroom (DeLuca et al. Citation2013). Recent research has highlighted the need for teacher educators themselves to upskill their assessment literacy (Young, MacPhail, and Tannehill Citation2022). ITE programmes must also recognise that beyond assessment literacy, PSTs’ experiences of assessment are complex and need a space to be problematised and disrupted, a space where they can re(discover) and re(experience) the power of assessment as a support for learning (Black and Wiliam Citation1998). Such a space may allow the PST to develop TAI that works in favour of their students and have an appreciation of how opposing purposes of assessment can cause them tension (Hopfenbeck Citation2018).

One of the dominant discourses about assessment, which views the purpose of assessment as one of the measurement of learning (Boud Citation2022; Price et al. Citation2008) was evident in the findings of this study. PSTs at times only valued what could be measured and discounted anything that did not offer them a mark that contributed to their certification (Knight Citation2002). The bigger picture of how a particular assignment or piece of work can contribute to their overall personal learning and development was viewed as a ‘waste of time’. For some PSTs, the nature of assessment was reduced to evaluation. Yambi and Yambi (Citation2020) define the purpose of an evaluation as judging the merit or quality of a process against a standard. Assessment values the support a teacher offers a student in providing quality feedback that will move learning forwards in the future. TOP desired to offer PSTs the importance of both approaches but to recognise that whilst both evaluation and assessment collect ‘data about a performance or work product, what is done with these data in each process is substantially different and invokes a very different mindset’ (Yambi and Yambi Citation2020, 1). The evaluation approach encourages students to compare each other based on a mark or number and juxtaposing one thing in relation to another and thus something is defined through what it is not (Colebrook Citation2002). This type of evaluation on its own favours a static understanding rather than seeing a student in the process of change, flux, and becoming. Engaging with the process of formative assessment embraces the uniqueness of the student’s learning and celebrates what the philosophers Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987) conceive as ‘difference in kind’ rather than ‘difference in degree’. Assessment is viewed not as a final definition of who the student is but creates the space for disturbing the acceptance of that final grade as if that was the only way things could be for a student. Formative assessment opens a dimension of possibility, mystery, and unpredictability.

An authentic assignment

Preparing a PST for this unpredictability and diversity in the classroom demands a new approach to assignments in teacher education (Darling-Hammond Citation2000). Villarroel et al. (Citation2018) propose a transformation from a culture of objective and standardised tests that are focused on measuring portions of atomised knowledge, towards a more complex and comprehensive assessment of knowledge and higher-order skills. The authentic assessment integrates realism, contextualisation, and problematisation. It is defined as ‘a form of assessment in which students are asked to perform real world tasks that demonstrate meaningful application of essential knowledge and skills’ (Mueller Citation2005, 1). The PSTs asserted that engagement with this assignment highlighted the complex process that was involved in engaging with a CBA and the many skills it drew upon to ensure that students were able to explore, explain, and reflect on further action. The application of this learning to their classroom was one of the strongest benefits of this task, and the need to draw on Learning Outcomes, scaffold learning further for students through success criteria, rubrics, and clarity around descriptors, formed their comprehension around such assessment practices.

Building TAI through peer collaboration

The engagement with a more ‘authentic’ assessment assignment offered PSTs the benefits of working in a diverse group of peers and expanding their learning (Bohemia and Davison Citation2012). The collaborative groups engaged in problematising the real world problem of the CBA, which assisted with their critical and social skills, becoming autonomous learners, and engaging in the very diversity of each other’s perception development (Boud Citation1995; Gayo-Avello and Fernández-Cuervo Citation2003). In Ireland, the Teaching Council’s vision for school placement is ‘underpinned by a shared professional understanding that collaborative engagement with school placement provides professional learning opportunities for all involved’ (Citation2020b, 17). Collaborative assignments help to prepare the PST for engagement in professional learning communities. The findings also highlighted the difficulties of engaging in teamwork in ITE and the human problems of those who are unmotivated and do not engage. The study evidenced that peer assessment assisted in challenging previous feelings and beliefs about assessment purposes and standards when the team were willing to engage in truthful dialogue and discussion. The climate or culture of the group to take this risk was an important insight into the findings for both ITE and for their engagement with future teacher collaborative groups in schools. With this openness to listen, learn, and liaise, the PST can develop an expanded learning not only of their assessment literacy but also of their conceptions around the CBA and formative assessment.

Conclusion

During Covid-19, the TOP team re-envisioned the centrality of assessment in their ITE programme. This study focussed on how one assignment tried to interrupt and challenge PSTs’ previous beliefs and feelings about assessment and build their assessment identity (Yueting and Brown Citation2016). It evidenced through the four components of the assignment that PSTs furthered their experience in how both formative and summative assessments might work together in support of not only their own learning but that of their students. The authentic assignment expanded assessment literacy through peer collaboration but also demonstrated the importance of understanding the multiple purposes and functions of assessment. Challenging the assessment beliefs and feelings of PSTs through the assignment cannot be a once-off experience but works on a continuum of learning (Lysaght and O’Leary Citation2013). Teacher educators

may need to include in the curriculum scenarios that are both cognitively challenging and emotionally appealing (e.g., how do you assess a hard-working student whose work is poor quality and a lazy student whose work is high quality) so that PSTs will reflect upon their own conceptions and practices of assessment

The findings from the current study reinforce this idea and propose that the development of TAI is highly complex and therefore its many components need to be endorsed throughout the ITE programme.

Notwithstanding these generally positive findings, a number of study limitations and areas for further research arise from the current paper. First, this paper has focused solely on the voices of PSTs, and there is merit in undertaking a similar analysis of the perceptions and experiences of tutors that engaged in TOP. Second, further investigation should be undertaken with regard to the use and role of digital technologies for the assessment and collaborative processes explored in the current paper and the potentials this may bring for these activities as we move into post-pandemic times. The process of reflective practice for PSTs needs further scaffolding and thought. Finally, an exploration of how to further connect the online component of TOP with school-based settings should be undertaken with a view to further preparing these PSTs for the classrooms that await them.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Audrey Doyle

Audrey Doyle is an Assistant Professor in the School of Policy and Practice at DCU. Her area of interest is curriculum and the agency of teachers in becoming curriculum makers and assessors.

Enda Donlon

Enda Donlon is an Associate Professor in the school of STEM Education, Innovation and Global Studies at the Institute of Education, Dublin City University. His research interests include digital learning and teacher education, with a particular emphasis on where the two intersect.

Marie Conroy Johnson

Marie Conroy Johnson is an Assistant Professor and Director of School Placement in the School of Policy and Practice at the Institute of Education at Dublin City University. Her research interests include Initial Teacher Education, School Placement, Leadership and Management in Education, Education and the Law, and Faith-Based Identity in Religious Schools.

Elaine McDonald

Elaine McDonald is an Assistant Professor in the School of Policy and Practice at the DCU Institute of Education. She lectures in the areas of professional development, teacher identity, and teaching methodology.

PJ Sexton

P. J. Sexton is an Assistant Professor in the School of Policy and Practice at the DCU Institute of Education and is currently the Director of CREATE21 (Centre for Collaborative Research Across Teacher Education for the twenty-first Century). His research interests include teacher education, reflective practice, mentoring, supervision, religious education, and lifelong learning.

References

- Allal, L. 2013. “Teachers’ Professional Judgement in Assessment: A Cognitive Act and a Socially Situated Practice.” Assessment in Education Principles, Policy & Practice 20 (1): 20–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594x.2012.736364.

- Atjonen, P., S. Pöntinen, S. Kontkanen, and P. Ruotsalainen. 2022. “In Enhancing Preservice Teachers’ Assessment Literacy: Focus on Knowledge Base, Conceptions of Assessment, and Teacher Learning.” Frontiers in Education 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.891391.

- Biesta, G. J. J. 2014. Beautiful Risk of Education. Colorado: Paradigm.

- Biesta, G. J. J. 2015. “What Is Education For? On Good Education, Teacher Judgement, and Educational Professionalism.” European Journal of Education 50 (1): 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12109.

- Birenbaum, M., C. DeLuca, L. Earl, M. Heritage, V. Klenowski, A. Looney, K. Smith, H. Timperley, L. Volante, and C. Wyatt-Smith. 2015. “International Trends in the Implementation of Assessment for Learning: Implications for Policy and Practice.” Policy Futures in Education 13 (1): 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210314566733.

- Birt, L., S. Scott, D. Cavers, C. Campbell, and F. Walter. 2016. “Member Checking: A Tool to Enhance Trustworthiness or Merely a Nod to Validation?” Qualitative Health Research 26 (13): 1802–1811. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316654.

- Black, P., and D. Wiliam. 1998. “Assessment and Classroom Learning.” Assessment in Education Principles, Policy & Practice 5 (1): 7–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969595980050102.

- Bohemia, E., and G. Davison. 2012. “Authentic Learning: The Gift Project.” International Journal of Technology and Design Education 17 (2): 49–62. https://ojs.lboro.ac.uk/DATE/article/download/1731/1643.

- Boud, D. 1995. Enhancing Learning Through Self-Assessment. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Boud, D. 2022. “Assessment for Future Needs: Emerging Directions for Assessment Change.” Keynote presentation at International Assessment in Higher Education Conference Manchester, June 22-24.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2013. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. London: SAGE.

- Braun, V., V. Clarke, E. Boulton, L. Davey, and C. McEvoy. 2021. “The Online Survey as a Qualitative Research Tool.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 24 (6): 641–654. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2020.1805550.

- Colebrook, C. 2002. Understanding Deleuze. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Connelly, M. F., and D. J. Clandinin. 1999. Shaping a Professional Identity: Stories of Educational Practice. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Cooley, C. H. 1902. Human Nature and the Social Order. New York: Scribner.

- Darling-Hammond, L. 2000. “How Teacher Education Matters.” Journal of Teacher Education 51 (3): 166–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487100051003002.

- Darling-Hammond, L. 2006. “Constructing 21st-Century Teacher Education.” Journal of Teacher Education 57 (3): 300–314. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487105285962.

- Day, C., A. Kington, G. Stobart, and P. Sammons. 2006. “The Personal and Professional Selves of Teachers: Stable and Unstable Identities.” British Educational Research Journal 32 (4): 601–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920600775316.

- Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Dellinger, A. B., J. J. Bobbett, D. F. Olivier, and C. D. Ellett. 2008. “Measuring teachers’ Self-Efficacy Beliefs: Development and Use of the TEBS-Self.” Teaching and Teacher Education 24 (3): 751–766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2007.02.010.

- DeLuca, C., T. Chavez, A. Bellara, and C. Cao. 2013. “Pedagogies for Pre-Service Assessment Education: Supporting Teacher Candidates. Assessment Literacy Development.” The Teacher Educator 48 (2): 128–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/08878730.2012.760024.

- Douwe, B., P. C. Meijer, and N. Verloop. 2004. “Reconsidering Research on teachers’ Professional Identity.” Teaching and Teacher Education 20 (2): 107–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2003.07.001.

- Doyle, A., M. Conroy Johnson, E. Donlon, E. McDonald, and P. J. Sexton. 2021. “The Role of the Teacher As Assessor: Developing Student Teachers’ Assessment Identity.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 46 (12): 52–68. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2021v46n12.4.

- Doyle, A., Z. Lysaght, and M. O’Leary. 2021. “High Stakes Assessment Policy Implementation in the Time of COVID-19: The Case of Calculated Grades in Ireland.” Irish Educational Studies 40 (2): 385–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2021.1916565.

- Elo, S., M. Kääriäinen, O. Kanste, T. Pölkki, K. Utriainen, and H. Kyngäs. 2014. “Qualitative Content Analysis: A Focus on Trustworthiness.” SAGE Open 4 (1): 2158244014522633. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014522633.

- Enda, D., M. Conroy Johnson, A. Doyle, E. McDonald, and P. J. Sexton. 2022. “Presence Accounted For? Student-Teachers Establishing and Experiencing Presence in Synchronous Online Teaching Environments.” Irish Educational Studies 41 (1): 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2021.2022520.

- Erikson, E. 1959. Identity and the Life Cycle. New York: International Universities Press.

- Gayo-Avello, D., and H. Fernández-Cuervo. 2003. “Online Self-Assessment As a Learning Method.” In Proceedings 3rd IEEE International Conference on Advanced Technologies 254–255. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICALT.2003.1215070.

- Herppich, S., A.-K. Praetorius, N. Forster, I. Glogger-Frey, K. Karst, D. Leutner, L. Behrmann, et al. 2018. “Teachers’ Assessment Competence: Integrating Knowledge-, Process-, and Product-Oriented Approaches into a Competence-Oriented Conceptual Model.” Teaching and Teacher Education 76:181–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.12.001.

- Hopfenbeck, T. N. 2018. “Classroom Assessment, Pedagogy and Learning – Twenty Years After Black and Wiliam 1998.” Assessment in Education Principles, Policy & Practice 25 (6): 545–550. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2018.1553695.

- Jenlink, P. M., Ed. 2021. Understanding Teacher Identity: The Complexities of Forming an Identity As Professional Teacher. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Kelchtermans, G. 2009. “Who I Am in How I Teach Is the Message: Self-Understanding, Vulnerability and Reflection.” Teachers & Teaching 15 (2): 257–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600902875332.

- Knight, P. T. 2002. “The Achilles’ Heel of Quality: The Assessment of Student Learning.” Quality in Higher Education 8 (1): 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538320220127506.

- Lefever, S., M. Dal, and Á. Matthíasdóttir. 2007. “Online Data Collection in Academic Research: Advantages and Limitations.” British Journal of Educational Technology 38 (4): 574–582. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2006.00638.x.

- Lobe, B. 2017. “Best Practices for Synchronous Online Focus Groups.” In A New Era in Focus Group Research: Challenges, Innovation and Practice, edited by R. S. Barbour and D. L. Morgan, 227–250. London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-58614-8_11.

- Looney, A., J. Cumming, F. van Der Kleij, and K. Harris. 2018. “Reconceptualising the Role of Teachers As Assessors: Teacher Assessment Identity.” Assessment in Education Principles, Policy & Practice 25 (5): 442–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2016.1268090.

- Lutovac, S., and M. Assunção Flores. 2022. “Conceptions of Assessment in Pre-Service Teachers’ Narratives of Students’ Failure.” Cambridge Journal of Education 52 (1): 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764x.2021.1935736.

- Lysaght, Z., and M. O’Leary. 2013. “An Instrument to Audit Teachers’ Use of Assessment for Learning.” Irish Educational Studies 32 (2): 217–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2013.784636.

- MacPhail, A., J. Halbert, and H. O’Neill. 2018. “The Development of Assessment Policy in Ireland: A Story of Junior Cycle Reform.” Assessment in Education Principles, Policy & Practice 25 (3): 310–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594x.2018.1441125.

- MacPhail, C., N. Khoza, L. Abler, and M. Ranganathan. 2016. “Process Guidelines for Establishing Intercoder Reliability in Qualitative Studies.” Qualitative Research 16 (2): 198–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794115577012.

- Marschall, G. 2022. “The Role of Teacher Identity in Teacher Self-Efficacy Development: The Case of Katie.” Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education 25 (6): 725–747. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10857-021-09515-2.

- Mockler, N. 2011. “Beyond ‘What Works’: Understanding Teacher Identity As a Practical and Political Tool.” Teachers & Teaching 17 (5): 517–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2011.602059.

- Mueller, J. 2005. “The Authentic Assessment Toolbox: Enhancing Student Learning Through Online Faculty Development.” Journal of Online Learning and Teaching/merlot 1 (1): 1–7. http://jolt.merlot.org/documents/VOL1No1mueller.pdf.

- Mutton, T. 2020. “Teacher Education and Covid-19: Responses and Opportunities for New Pedagogical Initiatives.” Journal of Education for Teaching 46 (4): 439–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2020.1805189.

- NCCA. 2012. Framework for Junior Cycle. Dublin: NCCA Publishing.

- NCCA. 2015. Framework for Junior Cycle. Dublin: NCCA Publishing.

- NCCA. 2019. “Senior Cycle Review: Draft Public Consultation Report”. Dublin: NCCA Publishing.

- NCCA. 2021. Reporting. https://ncca.ie/en/junior-cycle/assessment-and-reporting/reporting/.

- OECD. 2020. Implementing Education Policies Education in Ireland: An OECD Assessment of the Senior Cycle Review. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/636bc6c1-en.

- Pishgadam, R., J. Golzar, and M. A. Miri. 2022. “A New Conceptual Framework for Teacher Identity Development.” Frontiers in Psychology 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.876395.

- Pollard, A. edited by 2010. “Professionalism and Pedagogy: A Contemporary Opportunity.” A Commentary by the Teaching and Learning Research Programme and the General Teaching Council for England, London:TLRP. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/4160558.pdf.

- Price, M., B. O’Donovan, C. Rust, and J. Carroll. 2008. “Assessment Standards: A Manifesto for Change.” Brookes eJournal of Learning and Teaching 2 (3): 1–2.

- Pryor, J., and B. Crossouard. 2010. “Challenging Formative Assessment: Disciplinary Spaces and Identities.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 35 (3): 265–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930903512891.

- Punya, M., and M. J. Koehler. 2006. “Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge: A Framework for Teacher Knowledge.” Teachers College Record 108 (6): 1017–1054. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00684.x.

- Rose, D. H., and A. Meyer. 2002. Teaching Every Student in the Digital Age: Universal Design for Learning. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED466086.

- Scriven, M. 1967. “The Methodology of Evaluation.” In Perspectives of Curriculum Evaluation, edited by R. W. Tyler, R. M. Gagné, and M. Scriven, 39–83. Chicago: Rand McNally.

- Smith, K. 2016. “Functions of Assessment in Teacher Education.” In International Handbook of Teacher Education: Volume 2, edited by J. Loughran and M. L. Hamilton, 405–428. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-0369-1_12.

- Steinmayr, R., A. Meißner, A. Weidinger, and L. Wirthwein. 2014. “Academic Achievement.” Oxford Bibliographies. https://doi.org/10.1093/obo/9780199756810-0108.

- Stiggins, R. J. 1988. “Revitalizing Classroom Assessment: The Highest Instructional Priority.” Phi Delta Kappan 69 (5): 363–368. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20403636.

- The Teaching Council. 2020a. Céim: Standards for Initial Teacher Education. Maynooth: The Teaching Council. https://www.teachingcouncil.ie/en/news-events/latest-news/ceim-standards-for-initial-teacher-education.pdf.

- The Teaching Council. 2020b. Guidance Note for School Placement 2020-2021. Maynooth: The Teaching Council. https://www.teachingcouncil.ie/en/news-events/latest-news/10-08-2020-guidance-note-for-school-placement-2020_.pdf.

- Thomas, L., and C. Beauchamp. 2007. “Learning to Live Well As Teachers in a Changing World: Insights into Developing a Professional Identity in Teacher Education.” The Journal of Educational Thought 41 (3): 229–243. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23765520.

- Turner, J. C., A. Christensen, H. Z. Kackar-Cam, S. M. Fulmer, and M. Trucano. 2018. “The Development of Professional Learning Communities and Their Teacher Leaders: An Activity Systems Analysis.” Journal of the Learning Sciences 27 (1): 49–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2017.1381962.

- Villarroel, V., S. Bloxham, D. Bruna, C. Bruna, and C. Herrera-Seda. 2018. “Authentic Assessment: Creating a Blueprint for Course Design.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 43 (5): 840–854. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2017.1412396.

- Vygotsky, L. 1986. Thought and Language. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Wallace, R., E. Goodyear-Grant, and A. Bittner. 2021. “Harnessing Technologies in Focus Group Research.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 54 (2): 335–355. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423921000226.

- White, I., and M. McSharry. 2021. “Pre-Service Teachers’ Experiences of Pandemic Related School Closures: Anti-Structure, Liminality and Communitas.” Irish Educational Studies 40 (2): 319–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2021.1916562.

- Yambi, T., and C. Yambi. 2020. “Assessment and Evaluation in Education.” Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342918149_ASSESSMENT_AND_EVALUATION_IN_EDUCATION.

- Young, A.-M., A. MacPhail, and D. Tannehill. 2022. “Teacher Educators’ Engagement with School-Based Assessments Across Irish Teacher Education Programmes.” Irish Educational Studies 43 (2): 189–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2022.2061562.

- Yueting, X., and G. T. L. Brown. 2016. “Teacher Assessment Literacy in Practice: A Reconceptualization.” Teaching and Teacher Education 58:149–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.05.010.