ABSTRACT

Throughout the customer journey, the employee-customer interaction drives customer responses. The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically influenced shopping behavior with face masks playing a major role. This research investigates how consumer behavior has changed and how frontline employee (FLE) non-verbal (emotional facial expressions) and verbal cues (verbal expertise) influence customer responses dependent on whether FLEs wear a face mask or not. Semi-structured interviews among consumers, an open association study among students and an experimental study using Panel data were conducted. Findings of these online studies with German-speaking consumers show that face masks do not exclusively cause negative feelings and problems; they also reduce the perceived risk of a COVID-19 infection. Importantly, customers can correctly decode FLE smiling even when wearing face masks; however, the relevance of verbal expertise increases compared to FLE emotion displays. This state-of-the-art research during COVID-19 provides novel insights into dyadic service interactions for research and management.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the lives of almost every single person around the world. While at some point in time during the pandemic, many governments had to fully lock down public life, including shopping, hospitality or recreation environments, a number of countries are emerging from lockdown. To keep COVID-19 infection rates at a minimum, however, individuals are asked to restrict face-to-face-interactions by keeping social distance and/or wearing face masks in public (Gray, Citation2020; Mehta et al., Citation2020; Spitzer, Citation2020). In many countries (e.g. Austria, Germany, UK; Medinlive, Citation2020; Rigby, Citation2020), individuals are forced or at least suggested to wear face masks in shopping environments. Consumer behavior has dramatically changed since the COVID-19 pandemic has started (Scott et al., Citation2020), since consumers often shop less frequently, reduce the shopping time to an absolute minimum and are more goal-oriented in their shopping endeavors. These changed behaviors can be due to the individuals’ fear of being infected and/or the discomfort associated with face masks, hygiene restrictions, etc. (Accenture, Citation2020). While the news is full of headlines regarding COVID-19 and macro-environmental consequences, specifically, the economic breakdown, not much is known on the micro-environmental consequences at the individual level along the customer journey and experience (Lemon & Verhoef, Citation2016). Our first research question is thus, how has the shopping behavior of the individual consumer changed in times of the COVID-19 pandemic and which role do face masks play in service industries?

In dyadic service interactions, as in any other face-to-face interaction, mimicry and emotional facial expressions are one of the major drivers of successful interactions (de la Rosa et al., Citation2018; Gabbott & Hogg, Citation2001). Frontline employee (FLE) emotional facial expressions, sometimes also labeled as emotion display or displayed affect (Marinova et al., Citation2018), are shown to play an important role for customer satisfaction (Grandey et al., Citation2005) and related outcomes such as quality perception (Pugh, Citation2001), word-of-mouth communication (WOM; White, Citation2010) or willingness to pay (Chi et al., Citation2011). Practice (Fortin, Citation2020; Simon, Citation2020) and research (Carbon, Citation2020; Mehta et al., Citation2020; Spitzer, Citation2020) claim that wearing face masks inhibits interactants to correctly identify emotions of each other since the face as a major means to express emotions is covered (Maeck, Citation2020; Spitzer, Citation2020). Thus, an important driver of the success of dyadic service interactions, such as customer satisfaction (Marinova et al., Citation2018) or social rapport (Hennig-Thurau et al., Citation2006), would be missing in case interactants are wearing face masks. However, there is no consensus yet, on whether face masks really inhibit interactants to correctly identify each other’s emotions. In Asian cultures, that are much more used to wearing face masks (DW, Citation2020) compared to Western cultures, management advices FLEs to show a ‘deep’ smile even when wearing face masks (Ahgz, Citation2020) because recipients can recognize this smile. Such an authentic smile is called a Duchenne smile (Chartrand & Gosselin, Citation2005; Del Giudice & Colle, Citation2007; Ekman et al., Citation2002), which cheers up the whole face by not only lifting the corners of the mouth but also raising the cheeks resulting in crows’ feet wrinkles around the eye (Ekman et al., Citation2002; Lechner & Paul, Citation2019) which play a superior role for the identification of an authentic smile (Ekman et al., Citation2002). Because the eye area is not covered through a face mask, such a smile can be recognized even when wearing a face mask.

If a recipient perceives and decodes the sender’s facially expressed emotions, for example, his or her smiling, this usually leads to an emotional reaction such as the recipient’s positive emotional state (Elfenbein, Citation2014; Hennig-Thurau et al., Citation2006; Pugh, Citation2001). In dyadic service interactions, this means that the FLE smile leads to positive customer emotions. Drawing on emotional labor theory (Hochschild, Citation2006), the FLE is asked to smile rather than showing neutral or negative faces (Ashforth & Humphrey, Citation1993; Walsh & Bartikowski, Citation2013) to elicit positive emotions as well as positive cognitive and behavioral responses in the customer (Delcourt et al., Citation2016; Grandey et al., Citation2005; Lin et al., Citation2008; Pugh, Citation2001). An important question, and our second research question, therefore, is to investigate whether face masks (a) really inhibit the customer to correctly identify FLE emotions and, consequently, (b) impede its effects on positive customer emotions and cognitive and behavioral customer responses. In terms of the latter, customer advice taking, understood as the consistency between the consumer’s decision and the advisor’s recommendation (Bonaccio & Dalal, Citation2006), is a relevant aspect of service interactions (Agnihotri et al., Citation2016) as well as social rapport which is defined as ‘a customer’s perception of having an enjoyable interaction with a service provider employee, characterized by a personal connection between the two interactants’ (Hennig-Thurau et al., Citation2006, p. 60). Customer satisfaction, that is, customer’s post-encounter evaluation of a service company’s performance (Fornell et al., Citation1996) and word-of-mouth (WOM), which is described as ‘[…] informal, person-to-person communication between a perceived noncommercial communicator and a recipient regarding a brand, a product, an organization, or a service’ (Harrison-Walker, Citation2001, p. 63) are further customer responses (success metrics) that are investigated.

Communication success and positive customer responses in dyadic service interactions are not only driven by FLE emotion display and the transfer of emotions, but also by FLE verbal cues, that is, FLE verbal expertise. The literature on FLE problem-solving effectiveness and associated with this customer satisfaction suggests that FLE verbal cues in such dyadic service interactions play a major role for interaction success since these verbal cues are indicators of FLE knowledge, skills and expertise (Marinova et al., Citation2018; Wood et al., Citation2008). While some suggest that verbal communication is more difficult when wearing face masks (Luximon et al., Citation2016; Mehta et al., Citation2020; Spitzer, Citation2020; Wolfe et al., Citation2020), we do not expect verbal expertise to decrease in relevance when wearing face masks, but rather increase in importance since face masks only slightly exacerbate, but do not hinder the verbal communication between interactants (Luximon et al., Citation2016; Spitzer, Citation2020; Thomas et al., Citation2011). This leads to our third research question, that is, does the relevance of non-verbal cues in the form of FLE emotion display and verbal cues in the form of FLE verbal expertise change for positive customer responses if the FLE is wearing a face mask?

To sum up, this research makes a number of contributions to the literature. First, by investigating consumer behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic and the specific role face masks play, it contributes to consumer behavior in times of crises (Carbon, Citation2020; Spitzer, Citation2020). Second, this research clearly makes a contribution to emotional labor theory (Hochschild, Citation2006) and previous service management studies in this field (Grandey et al., Citation2005; Lin et al., Citation2008; Pugh, Citation2001) which have not yet considered face masks’ specific role. Third, this research contributes to the literature on FLE expertise (Marinova et al., Citation2018; Wood et al., Citation2008) by considering face masks’ role for and impact on FLE verbal communication (e.g. Luximon et al., Citation2016; Spitzer, Citation2020; Thomas et al., Citation2011).

The paper is structured as follows. The next part deals with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on consumer shopping behavior with a specific focus on face masks’ impact (Studies 1 and 2). Then, the paper examines face masks’ role for a correct identification of FLE emotions and its potential hindering effect on the influence of FLE emotions on customer emotions and responses. Related to that, the possible changing relevance of FLE verbal expertise dependent on wearing a face mask or not is investigated (Study 3). Following a multi-method approach, the three studies comprehensively address these research objectives and benefit from a holistic perspective consisting of qualitative and quantitative research methods. Similar to previous research (Kuehnl et al., Citation2019), a qualitative approach provides initial insights into this relatively new field of research, followed by a quantitative study that aims at testing proposed relationships.

Conceptual background and hypotheses development

The perception and decoding of FLE emotion displays

Following discrete emotion theory (Ekman, Citation1992), emotions which are facially expressed through prototypical patterns, can easily be identified independent of culture, cognition and context. The perception of human faces is a relatively fast process focusing on typical characteristics of the face such as the eyes and the nose (Carbon et al., Citation2013) enabling recipients to use the human face as a rich source of information about the sender, and specifically, the sender’s emotional state (de la Rosa et al., Citation2018; Spitzer, Citation2020). While research generally confirms customers’ ability to decode FLE emotions which further influence customer emotions (Barger & Grandey, Citation2006; Du et al., Citation2011; Lechner & Paul, Citation2019), the literature provides mixed results regarding the impact of face masks on the decoding process. On the one hand, with the help of Ekman et al.’s (Citation2002) action units (AUs) of muscular activity used to categorize facially expressed emotions, evidence is given that a non-smiling face without muscular activity compared to a smiling face represented by the activation of AU#6 (i.e. cheek raiser leading to crows’ feet wrinkles in the eye area) and AU#12 (i.e. lip corner puller according to the Facial Action Coding System; FACS) can be decoded, even when an individual is wearing a face mask. Thus, recipients (e.g. customers) classify an FLE neutral face as such based on the non-existence of muscular activity, while they categorize a face as smiling given AU#12 and AU#6, for example, are shown. To identify a smile, the area around the eyes plays an important role, since an authentic smile (i.e. a Duchenne smile), includes the activation of AU#6 (Ekman et al., Citation2002; Lechner & Paul, Citation2019) which is not covered by the face mask leading to recipients being able to easily distinguish between different smiles which include or do not include the activation of AU#6 (Fernandez-Dols & Ruiz-Belda, Citation1995). Previous research even confirms that recipients merely focus on AU#6 to classify a facial expression as smiling (Chartrand & Gosselin, Citation2005; Del Giudice & Colle, Citation2007). On the other hand, recent research related to emotion detection during the COVID-19 pandemic proposes that decoding of emotion displays is hindered by face masks because important parts (i.e. the area around the mouth) of the face are covered (Maeck, Citation2020; Spitzer, Citation2020) resulting in less accurate judgments on the displayed emotion. Smiling faces, for example, were identified as neutral (Carbon, Citation2020). This finding emphasizes the high importance of the eye area for the correct decoding of smiling which might be more difficult given only AU#12 is activated (Fernandez-Dols & Ruiz-Belda, Citation1995). Similarly, research found the area around the eye to be one of the most informative areas for non-verbal communication (Spitzer, Citation2020). To sum up, face masks might hinder customers from correctly decoding FLE smiling, but only when AU#6 is not active, which is not the case for an authentic smile. We therefore hypothesize:

H1: Customers can decode FLE emotion displays both when the FLE (a) is not wearing a face mask and (b) wearing a face mask.

The role of FLE emotion displays for customer responses

Drawing on emotional labor theory, customers expect FLEs to show positive emotions (Hochschild, Citation2006), which further affect success metrics such as customer quality perception or loyalty intentions (Hennig-Thurau et al., Citation2006; Pugh, Citation2001), advice taking (Kopelman et al., Citation2006), social rapport (Hennig-Thurau et al., Citation2006), and customer satisfaction (Marinova et al., Citation2018). Accordingly, the FLE is asked to display specific emotions in line with organizationally introduced display rules (Hochschild, Citation2006), that is, guidelines on expected emotion displays in service interactions (e.g. Walsh & Bartikowski, Citation2013) to affect customer emotions and thus, desired customer responses. The display of positive emotions is most effective to retain customers and to increase positive customer responses since they help to build a warm relationship between the FLE and the customer (Hennig-Thurau et al., Citation2006). That is, FLE emotion displays need to meet customer emotional needs in order to result in positive customer responses (Delcourt et al., Citation2016). And indeed, research found that FLE emotion displays are related to customer quality perception (Pugh, Citation2001), loyalty (Grandey et al., Citation2005), word-of-mouth communication (WOM; White, Citation2010), willingness to pay (Chi et al., Citation2011), social rapport (Hennig-Thurau et al., Citation2006) and satisfaction (Grandey et al., Citation2005; Marinova et al., Citation2018). In this research, we investigate the relationship of FLE emotion displays on FLE-related outcomes (i.e. advice taking and social rapport) and company-related outcomes (i.e. customer satisfaction and WOM).

Since customers expect positive emotion displays (Hochschild, Citation2006) with more intense and more authentic smiling leading to more positive results (Hennig-Thurau et al., Citation2006), the opposite is expected for non-smiling FLEs. In general, customers do not want to be confronted with a non-smiling FLE, which is also not in line with emotional display rules that ask to increase the expression of positive emotion displays and avoid neutral or negative facial expressions (Ashforth & Humphrey, Citation1993; Hochschild, Citation2006; Zapf et al., Citation2005). We expect customers to be able to correctly decode FLE smiling (Fernandez-Dols & Ruiz-Belda, Citation1995) even under the condition of the FLE wearing a face mask because the decoding of a smiling face with active AU#6 (Ekman et al., Citation2002a) is not covered by the face mask. Moreover, the area around the eye (i.e. active AU#6) is shown to be a rich source of information when it comes to communication (Spitzer, Citation2020). By contrast, for a non-smiling face, the face mask helps to cover and hide (Maeck, Citation2020) the unwished and unexpected FLE non-smiling facial expressions (Ashforth & Humphrey, Citation1993; Hochschild, Citation2006; Zapf et al., Citation2005). Thus, the face mask is proposed to downsize the negative effect arising from a FLE non-smiling facial expression, similar to emotional masks which help to cover the expression of societally non-tolerated emotions (Gosselin et al., Citation2010). Thus, we propose:

H2: A FLE smile positively influences customer responses in terms of (a) advice taking, (b) social rapport, (c) overall satisfaction, and (d) WOM both if the FLE is not wearing a face mask and wearing a face mask, however, (e) if the FLE does not smile, the effect on customer responses is less negative when s/he is wearing a face mask (vs. not wearing a face mask).

The role of FLE verbal expertise for customer responses

For a rewarding service interaction, FLEs need to take on a specific job role (Giebelhausen et al., Citation2014; Plouffe et al., Citation2016) with their abilities and behavior being crucial (Benbasat & Wang, Citation2005; Plouffe et al., Citation2016). In addition to FLE emotion displays as non-verbal cues, FLE problem solving using verbal cues that prove expertise and competence (Li et al., Citation2009; Marinova et al., Citation2018), are relevant for the evaluation of a satisfying customer experience (Wood et al., Citation2008). Typical FLE job requirements are thus not only in the area of positive emotion displays (Hochschild, Citation2006) but also in the area of professional verbal expertise to create superior service interactions (Agnihotri et al., Citation2016; Benbasat & Wang, Citation2005; Li et al., Citation2009; Plouffe et al., Citation2016). The basis of advanced professional expertise is the ability to understand customer needs in order to being able to offer them a solution that satisfies those needs (Agnihotri et al., Citation2016). As a consequence, FLE verbal expertise is highly linked to customer quality perception (Brady & Cronin Jr, Citation2001), advice acceptance (White, Citation2005), social rapport (Gremler & Gwinner, Citation2008), satisfaction (Coelho & Augusto, Citation2008) and word-of-mouth communication (Ou et al., Citation2012) with higher levels of expertise having a more positive impact (Bonaccio & Dalal, Citation2006; Sniezek & Van Swol, Citation2001). While the high relevance of FLE verbal expertise is undoubtable, the question arises which role face masks play for the impact of FLE verbal expertise on customer responses.

Referring to Marinova and colleague’s (Citation2018) classification of expertise as verbal cue, compared to emotion display as non-verbal cue, the literature provides mixed results regarding face masks’ role. On the one hand, FLEs seem not only to suffer from wearing face masks due to their discomfort but are also restricted in their verbal communication as it is more difficult to speak clearly (Mehta et al., Citation2020; Spitzer, Citation2020; Wolfe et al., Citation2020). On the other hand, even though the mask requires more effort from the FLE, in contrast to the facially expressed emotion display, verbal communication is still possible and appreciated (Luximon et al., Citation2016; Spitzer, Citation2020). Research in the medical context supports these results by stating that verbal communication is still accurately understood by interactants with a few exceptions, such as radio communication and noisy environments (Thomas et al., Citation2011). Consequently, in a tranquil fashion retail context, we expect the face mask not to impede FLE verbally communicated expertise, which is believed to be an important driver of customer responses independent of FLEs wearing a face mask or not. We propose:

H3: FLE high (vs. low) verbal expertise positively influences customer responses in terms of (a) advice taking, (b) social rapport, (c) overall satisfaction, and (d) WOM both if the FLE is not wearing a face mask and wearing a face mask.

The mediating role of customer emotions

The underlying process of the impact of FLE emotion display on customer responses can be described by customer’s perception of the shown emotion displays, followed by its decoding and appraisal and finally leading to an emotional reaction (Elfenbein, Citation2014). This process of emotional contagion is formally defined as ‘the tendency to automatically mimic and synchronize expressions, vocalizations, postures, and movements with those of another person and, consequently, to converge emotionally’ (Hatfield et al., Citation1992, pp. 153–154). Simply put, during service interactions, it can be described as a transfer of emotions from the FLE to the customer (Hennig-Thurau et al., Citation2006) leading to an immediate change in customer emotions (Hennig-Thurau et al., Citation2006; Niedenthal et al., Citation2000; Pugh, Citation2001). This emotional transfer effect is widely acknowledged in the service research literature and is shown to play a crucial role for customer responses (Barger & Grandey, Citation2006; Du et al., Citation2011; Lechner & Paul, Citation2019) as customer emotions determine their resultant attitudes and behavior (Lin et al., Citation2008). FLE smiling (Hennig-Thurau et al., Citation2006; Lin et al., Citation2008) thus has a positive impact on customer emotions which further affect customer responses such as quality perception, whereby a greater extent of FLE smiling and a more authentic smiling lead to more positive emotional reactions (Hennig-Thurau et al., Citation2006). Taken together, literature has provided evidence for the mediating effect of customer emotions in the link between FLE emotion displays and customer responses (e.g. Du et al., Citation2011; Pugh, Citation2001) with customers’ emotional change being a valid measure for customer emotions (Hennig-Thurau et al., Citation2006; Niedenthal et al., Citation2000).

However, we do not only consider FLE emotion display, which is a sign of non-verbal communication, but also verbal communication as an indicator of FLE expertise (Marinova et al., Citation2018). Indeed, both – verbal expertise and emotion display – are considered to be necessary job requirements (Hochschild, Citation2006; Li et al., Citation2009). Thus, in addition to FLE emotion displays as non-verbal cues of competence, her/his verbally communicated expertise is important in service interactions (Coelho & Augusto, Citation2008; Marinova et al., Citation2018; Wood et al., Citation2008). When speaking of verbal communication, we follow Marinova and colleagues (Citation2018), who define verbal cues as a sign of FLE competence (e.g. knowledge and skills) which is in line with Ericsson and Smith (Citation1991) who understand expertise as task-specific knowledge. Generally, FLE verbal communication and competence (Coelho & Augusto, Citation2008; Jain et al., Citation2009) have an impact on customer responses during service interactions with high levels of expertise increasing customer satisfaction (Coelho & Augusto, Citation2008). Moreover, FLE high verbal expertise has been shown to drive customer emotions (Lee et al., Citation2011) since customers experience feelings of delight, pleasantness and comfort when interacting with a knowledgeable and competent FLE, while low levels of verbal expertise lead to an increase in negative emotions. Contrarily, feelings of anger are experienced given customers interact with a less knowledgeable and incompetent person (Lee & Dubinsky, Citation2003; Meyer et al., Citation2017).

Based on these results, both FLE emotion display as non-verbal cue and expertise as verbal cue are highly relevant for service interactions by increasing customer perceived FLE credibility and affecting customer emotions and responses (Giebelhausen et al., Citation2014; Jain et al., Citation2009; Marinova et al., Citation2018; Wood et al., Citation2008). Generally, literature agrees that in dyadic service interactions non-verbal cues compared to verbal cues have a stronger impact on customer responses. Mistakes related to FLE non-verbal communication are thus more difficult to offset or overcome to guarantee communication success (Wood et al., Citation2008). The question arises if the relevance of FLE emotion display compared to expertise changes with the FLE wearing a face mask. As the verbal communication (i.e. expertise) compared to the non-verbal communication (i.e. emotion displays) is less hindered by the face mask (Thomas et al., Citation2011) one could expect an increase in verbal expertise’s relevance while the importance of FLE emotion display might stay stable or decrease since the activation of AU#6 cannot be decoded, but decoding of AU#12 is still possible. Thus, we hypothesize:

H4: FLE emotion displays (non-smiling vs. smiling) and verbal expertise (low vs. high) are relevant for customer (a) emotional change which further drives (b) advice taking, (c) social rapport, (d) overall satisfaction, and (e) WOM with FLE verbal expertise compared to emotion display increasing in relevance when the FLE is wearing a face mask.

Overview

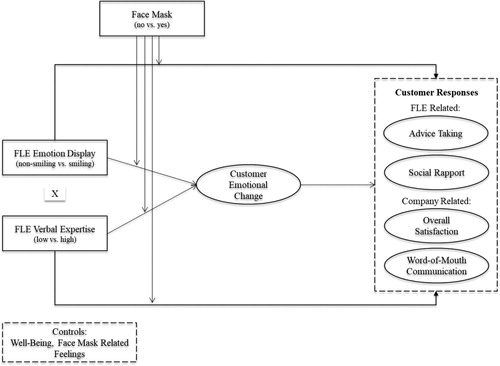

To answer the research questions and test the proposed hypotheses, three empirical studies were carried out. Hereby, we applied both qualitative and quantitative techniques for a holistic perspective and followed the theoretical logic of the customer journey (Lemon & Verhoef, Citation2016). Related to the pre-encounter and encounter stages, in Studies 1 and 2 we examined how shopping behavior has changed during the COVID-19 pandemic (Scott et al., Citation2020) and which role wearing face masks plays in this regard (i.e. research question one). Second, going more into detail and focusing on the encounter and post-encounter stages, Study 3 aims at investigating whether face masks inhibit customers to correctly decode FLE emotion displays which further affect customer emotions and attitudinal responses (i.e. research question two). Finally, changes in the relevance of FLE verbal expertise and emotion displays for customer responses were examined given the FLE is wearing a face mask or not (i.e. research question three). In order to investigate the first research objective, twelve qualitative semi-structured interviews among fashion industry-consumers (Study 1) were conducted followed by an open association study among students (Study 2). A quantitative study (Study 3) using Panel data and applying an experimental design was applied to investigate the second and third research objectives, that is, the effect of FLE emotion displays and expertise on customer responses represented by FLE-related outcomes in terms of advice taking and social rapport and company-related outcomes in terms of overall satisfaction and WOM dependent on the FLE wearing a face mask or not. Customer well-being and face mask related feelings were integrated as control variables. shows the conceptual model of Study 3.

Study 1

Research design, procedure and sample

The qualitative study involved twelve semi-structured interviews. Following Mayring (Citation2015), a case-by-case basis was chosen, meaning that the individual beliefs and opinions of interviewees were central. Thus, nine narrative questions covering topics such as attitude towards and reasons for wearing face masks, change in purchasing behavior due to the COVID-19 pandemic or prospects for the future, as well as several follow up questions were stated in order to get a better understanding of interviewees’ perspectives and individual experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Those functional assisting questions follow the theoretical logic of the customer journey (Lemon & Verhoef, Citation2016). Supportive questions that are meant to guide the interviewees and encourage them to share deeper insights were also used. Depending on how much information was provided by the interviewees, a maximum of 48 open questions – nine narrative and 39 follow-up or supportive questions – were asked. The interviews lasted from ten to 28 min. Please refer to Appendix 1 for an overview of the interview questions.

Data were collected from individuals who were selected based on predefined criteria: representative age distribution, almost equal gender distribution and involvement in some fashion shopping within the last months (Robinson, Citation2014). Data were collected up to a ‘theoretical saturation point’, that is, no additional interviews were considered after no new information was found (Guest et al., Citation2006). After the participants were interviewed, transcripts were prepared and analyzed following the qualitative content analysis in this deductive approach. We applied a systematic rule-based procedure for the analysis, where an a-priori defined category system based on the interview questions was at the center of the analysis as a major instrument of interpretation and the text was subdivided into units of analysis. To increase validity, the following quality criteria (Mayring, Citation2015) were used. First, procedure documentation was ensured from the beginning on by keeping differentiated and explicit records of the procedure. Second, during the interviews, the interviewers made sure that interviewees have been correctly understood by summarizing their claims and directly enquiring into issues where misunderstandings could occur; communicative validation was thus given. Third, the rule-led approach ensured that the quality of the interpretation was secured through a gradual procedure including systematically carried out and previously determined steps of analysis (Echterhoff et al., Citation2013; Mayring, Citation2015). The interviews were analyzed proceeding iteratively by moving back and forth between theory and data (Miles & Huberman, Citation1999).

The sample consisted of twelve recorded interviews with seven females and five males between 22 and 76 years with a mean age of 38.00 (SD=18.53) years. Eleven interviewees were from Germany, one from Austria. They came from various professions ranging from students, over different technical and medical areas to a housewife and a retiree. All interviewees were consumers in the fashion industry and were confronted with the obligation of wearing a face mask in public.

Results

The process outlined above resulted in nine main categories, derived from the narrative questions, and 22 sub-categories, inspired by the follow-up questions. Following Lemon and Verhoef (Citation2016), the first three categories are part of the pre-encounter stage and the following three of the encounter stage. The remaining three cannot be directly related to the stages of the customer journey, but they make up a third important category, dealing with well-being and thoughts about the future. The entire categorization and results including anchor examples (i.e. direct quotes from the interviews) are outlined in . In a last step, relevant sections of all interviews were assigned to those categories and final results were obtained by paraphrasing and summarizing the interviewees’ answers. Counting the summarized and similar statements ensured quantifiability of the interviewees’ answers (Mayring, Citation2015).

Table 1. Study 1 – categorization and result summary.

Regarding main category #1 ‘attitude toward wearing face masks’, the interviewees have contrasting opinions as six have a rather negative attitude, whereas the other six are positive-minded. Of those having a negative attitude, three believe wearing masks is risky because people tend to be more careless or wear the masks wrong. However, the six, who named positive attitudes, mentioned the reduction of risk of droplet infection and increased freedom. All interviewees agree that wearing face masks is quite uncomfortable.

Related to category #2 ‘face mask obligation in public places’, eight believe the obligation to be highly reasonable and important, the remaining four are afraid that possible negative effects, for instance, reduced distance, will be predominant. Correspondingly, half of the interviewees are in favor of immediate abolition while the other half want the duty to be maintained. Half of the interviewees do not experience any personal disadvantages.

Related to category #3 ‘reasons for wearing face masks’, findings show that in general, a face mask is worn wherever it is obligated, as only four claim to be wearing the mask voluntarily. Interviewees are aware that face masks mainly protect others and not themselves. Nevertheless, seven out of twelve wear a face mask daily, some of them several hours, due to obligations in public areas or due to work.

The influence of wearing face masks on shopping behavior in the service encounter stage is discussed in category #4 ‘change in purchasing behavior due to the COVID-19 pandemic.’ Results show that eleven out of the twelve interviewees hardly go shopping anymore and instead buy much more online.

Focusing on category #5 ‘shopping experience during the COVID-19 pandemic’, eight interviewees explicitly mention negative feelings, for example, face mask bothers them and they are annoyed by long queues in front of stores. Nine interviewees report that verbal and non-verbal communication have become more difficult and people are perceived as less friendly due to the face mask covering most facial expressions with emotions being harder to transmit. Only three still enjoy shopping, but even those do not undertake long shopping trips anymore due to the inconvenience of the face mask.

Category #6 ‘influence of wearing face masks on relationship with others in the shopping context’ reveals the following. Altered communication is observed by all interviewees, who speak of highly difficult verbal communication due to acoustical problems caused by face masks resulting in shorter interactions. Nine interviewees say that the absence of mimicry is an additional hurdle as important non-verbal communication is missing and emotions can hardly be transmitted and perceived. One interviewee states:

One does not see the facial expressions or does not even know what kind of person is behind the mask. That's why I don't think that this is an optimal prerequisite because I would assume that emotional and human factors play a role in a sales consultation. (Interviewee 3)

You can see the mimicry a little bit when looking at the eyes. Especially when one laughs you can see it if you concentrate on it. (Interviewee 10)

The COVID-19 pandemic does not only have an impact on the shopping behavior but also on the well-being of every individual. This is covered in main category #7 ‘well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic.’ There is an overall agreement that the sentiment has altered, whichever way. These partly radical changes sometimes lead to changes in everybody’s way of life. Eleven interviewees talked about spending more time outdoor, doing things you have always wanted to do and having discovered new interests. Nonetheless, four interviewees also described disruptive experiences, for example, a loss of job.

The two final categories are #8 ‘prospects for the future’ and #9 ‘long-term influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on shopping behavior.’ Nine interviewees estimated the period of mask obligation for at least until the end of this year, possibly even longer, until a vaccine is available. Regarding the accustoming to face masks, the opinions differ widely. Half of the interviewees said that getting used to the masks was not a problem, but for the other half, it is an ongoing challenge. Concerning a long-term perspective, eleven interviewees claim to go shopping in brick-and-mortar stores again, as they enjoy the whole experience, including window-shopping and spending time with friends.

Study 2

Research design, procedure and sample

Study 1 showed that the COVID-19 pandemic dramatically changed the customer journey. The attitudes toward face masks differed widely from negative to positive. No consensus was further found on changes in verbal and non-verbal communication due to interactants wearing face masks in service interactions. To better understand these initial findings, dissolve disagreements and get deeper insights, we conducted an open association study (Study 2) among 281 German-speaking participants (Mage=25.42, SDage=7.93, 71.10% female) who were recruited via the e-mail distributor of a central European University. The majority of students taking part in the association study were from Austria, followed by Germany and the German-speaking part of Italy. In total, five open questions with a required minimum of three associations per question and two questions rated on a semantic differential scale from 1 (=negative) to 7 (=positive) framed the study. A filter question identified participants who had already gone shopping during the COVID-19 pandemic aside from food shopping. The socio-demographic data and an additional question which determined how many hours per week the participants are wearing face masks completed the questionnaire.

The analysis of the open association study followed a deductive evaluation system by assigning the mentioned associations to theory-driven categories based on the interview guideline’s questions (Mayring, Citation2000). Five a priori formulated categories were grounded on the approach of the customer journey by Lemon and Verhoef (Citation2016) defining three encounter stages. The first category which is ‘attitude towards face masks’ referred to the pre-encounter stage, followed by three categories which are ‘shopping behavior’, ‘interaction’, and ‘emotions’ focusing on the encounter stage. As in Study 1, ‘well-being’ could not be ascribed to any stage of the customer journey and therefore, made up its own category. Second, this structured content analysis was followed by a method of summary content analysis in which additional subcategories evolved following an inductive approach by summarizing and systematically reducing data resulting in sub-categories (Mayring, Citation2000). In a last step, the number of answers per subcategory and the overall number of responses per category were calculated thus, quantified, in order to draw further conclusions from the qualitative data (Mayring, Citation2000). provides an overview of the categories, the number of namings per category and the percentage of share, which is the number of answers per subcategory compared to the total number of responses per category.

Table 2. Study 2 – categorization and result summary.

Results

Overall, the analysis of the pre-encounter stage (Lemon & Verhoef, Citation2016) shows that participants rate their general attitude towards the obligation of wearing face masks rather positive (M=4.47, SD=2.34). In line with these results, the calculated percentage of share per sub-category showed that the underlying reasons contain slightly more associations in the positive (50.53%; e.g. protection, reduces the risk of contagion, reasonable, does not bother) than in the negative sub-category (42.71%; e.g. uncomfortable, useless, physical restrictions, benefit uncertain). A total of 6.67% of references are undefined.

Regarding the encounter stage (Lemon & Verhoef, Citation2016), participants first indicate at least three aspects of how the obligation to wear a face mask changed their shopping behavior. Consistent with our initial results from the qualitative interviews, participants describe a changed shopping behavior while wearing a face mask. Almost one-third (38.38%) of the associations show that consumers shop faster, less frequently and more targeted. Furthermore, they associate negative feelings with shopping and only buy the most necessary. Next, a filter question determined how many participants went shopping during the COVID-19 crisis, apart from food shopping, followed by an open listing of associations on how they perceived the interaction with the FLE during their shopping trip. A total of 44.21% of the participants had gone shopping apart from food shopping (e.g. fashion) during the COVID-19 pandemic. Those participants relate negative (24.12%; e.g. impersonal, less friendly, stressful) as well as positive impressions (16.47%; e.g. extremely polite, still very friendly, increased attention) to their interaction with the FLE, despite a more difficult verbal (12.64%) and non-verbal communication (9.12%). When thinking about their emotions during the interactions with the FLE, 46.77% of the feelings mentioned by the participants contain negative emotions, such as not feeling well (22.26%; e.g. do not feel well, strange, constricted) and feelings of anger (20.32%; e.g. annoyed, stressed out). However, positive emotions were also mentioned (26.45%), mainly concerning a sense of well-being with the mask (e.g. feeling well, good, relaxed). Overall, participants seem to be rather indifferent about their feelings while wearing a mask (M=3.36, SD=1.90 with 1=very negative to 7=very positive).

In a last step and in addition to the customer journey categorization (Lemon & Verhoef, Citation2016), participants listed up to five bullet points on their changes in mood and well-being while wearing a mask in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. In total, 73.21% of the mentioned associations are related to negative aspects and primarily concern them personally like ‘annoyance’ and ‘physical restrictions.’ The third most frequent complaint is the lack of non-verbal communication during interactions. In contrast to that, only 21.85% of the references contain positive associations like ‘more flexibility’ and ‘feeling of safety.’ The last question showed that on average, participants wear a face mask for 5.50 h per week with a minimum of zero and a maximum of 40 h (M=5.50, SD=6.56).

Overall, Study 2 confirms our initial results of Study 1 and deepens our understanding of important aspects. While in Study 1, half of the interviewees reported positive, and the other half negative attitudes toward wearing face masks, respondents in Study 2 also listed about 50% positive associations, and about 43% negative ones. Inspecting these associations provides rich insights into these attitudes. Similar further insights are gained on aspects, such as changed shopping behavior and altered communication. shows the detailed results of Study 2.

Study 3

Sample

To tackle research questions two and three, we conducted an experimental study, which also aimed at testing the relationships proposed in hypothesis 1 to hypothesis 4. The total sample consists of 340 participants (57.40% male, 42.10% female) with an average age of 38.25 (SD=12.41) years, which corresponds well to the German population (Rudnicka, Citation2020). A total of 50.90% of the participants are employed, 20.00% are self-employed, 13.20% are students, 4.70% are seeking work, 3.80% still go to school, 3.50% are retired, 1.20% are civil servants and 2.60% marked ‘other.’ During the data collection and the time of the COVID-19 lockdown, all participants resided in Germany. Participants wore a face mask on average 10.77 (SD=15.14) hours per week during the last eight weeks and have slightly positive face mask related feelings (M=3.83, SD=1.52). Asked for their well-being during the last weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic, participants felt rather well (M=4.27, SD=1.25).

Procedure

We ran an online laboratory experiment using a 2 (emotion displays: non-smiling vs. smiling) x 2 (verbal expertise: low vs. high) x 2 (face mask: no vs. yes) between-subjects factorial design. For this data collection, we used the online panel ‘Clickworker’ as done in previous research (Schroll et al., Citation2018). Participants were provided with a scenario which asked them to imagine being a customer at a fictive fashion retailer. In a first step, participants were told they entered the retail store ‘DressMe’ and were served by the shown FLE. In a second step, they were randomly assigned to one of the eight conditions; they were either advised by a scarcely competent, informed and knowledgeable (i.e. low verbal expertise condition) or a very competent, informed and knowledgeable FLE (i.e. high verbal expertise condition; Ericsson & Smith, Citation1991). The FLE was either smiling or non-smiling FLE (manipulation of FLE emotion display) and either wore a face mask or did not wear a face mask. Photographs were used for these manipulations as commonly done in this field of research (Lechner & Paul, Citation2019) and manipulations of FLE emotion display were based on the FACS (Ekman et al., Citation2002). A certified FACS-coder thus evaluated and rated the facial expressions to ensure that the non-smiling face is a face without muscular activity, while the smiling face shows a Duchenne smile including the activation of AU#6 and AU#12. All photographs were taken in a real retail environment with a real salesperson. To ensure complete comparability of the photographs, they were further edited in terms of brightness, size, saturation and sharpness using Adobe Indesign and Adobe Photoshop (see Appendix 2). In the conditions in which the salesperson was shown with a face mask, the customer was told to imagine wearing a face mask, too. All stimuli were shown for 20 s, which was perceived as an adequate time frame as a pre-test among a small group of people indicated. Before being exposed to the stimulus, participants were asked to answer questions on their current emotional state. Afterward, participants answered a questionnaire (all items randomized) containing manipulation checks, emotional state after looking at the stimulus, advice taking, social rapport, WOM, overall satisfaction, well-being and face mask related feelings as well as sociodemographic data.

Measures

The manipulation of the FLE emotion display was tested with three items from Chang et al. (Citation2014; e.g. ‘The FLE smiles.’) and face mask with one item (‘The FLE wore a face mask.’). Furthermore, the manipulation of FLE verbal expertise was checked with four items adapted from Brady and Cronin (Citation2001; e.g. ‘The FLE understands that I rely on his knowledge to meet my needs’) and Wang et al. (Citation2010; e.g. ‘The FLE has the knowledge to answer my questions.’). Advice taking was assessed with four items from White (Citation2005; e.g. ‘It is very likely that I follow the fashion FLE’s recommendation.’) and See et al. (Citation2011; e.g. ‘I will consider the advice of the FLE when making my decision.’). Social rapport was measured using four items from Hennig-Thurau et al. (Citation2006; e.g. ‘In thinking about my relationship with this person, I enjoyed interacting with this FLE.’) and WOM by using three items adapted from Zeithaml et al. (Citation1996; e.g. ‘I will say positive things about DressMee to other people.’). Customer overall satisfaction was assessed with three items from Hennig-Thurau et al. (Citation2002; e.g. ‘My decision to visit the fashion store DressMe was a wise one.’). Five items were chosen to measure customer well-being (World Health Organization, Citation1998; e.g. ‘Over the last two weeks I have felt calm and relaxed.’); face mask related feelings were assessed with three items derived from the results of the qualitative interviews (‘I feel comfortable wearing a face mask.’). Customer emotions (before and after being exposed to the stimulus) were measured with three items focusing on positive emotions (Howard & Gengler, Citation2001; e.g. ‘I was happy.’). All construct items were measured using seven-point Likert scales ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7).

Customer emotional change was calculated as a difference score between customer emotional state after being exposed to the stimulus minus their emotional state before being exposed to the stimulus. Thus, the emotional change score shows whether customer positive emotions increase or decrease after having been treated to the stimulus. While a negative change (less positive emotions ‘after’ compared to ‘before the interaction’) is characterized by a negative sign, a positive change is represented by a positive sign. For example, given a participant has a positive emotion-value of 5.00 on a seven-point Likert Scale before and one of 5.80 after being exposed to the stimulus, the resulting emotional change is .80 indicating that positive emotions have increased. Contrarily, given the positive emotion-value is 4.50 afterward, the change is –.50 which shows that positive emotions decreased after the interaction.

Results

Reliability and validity assessment of all study constructs was satisfactory. Outlier detection using Mahalanobis distance did not reveal any outliers (Rousseeuw & Van Zomeren, Citation1990). Means, standard deviations and correlations are shown in .

Table 3. Correlations.

Manipulation checks were successful using an independent samples t-test. Participants correctly identified FLE emotion displays since those in the smiling condition (n=170) compared to the non-smiling condition (n=170) agree that the FLE smiles (Mnon-smiling=2.55 vs. Msmiling=6.06, t(338)=−20.40, p<.001). Moreover, there is a significant difference between the low (n=175) vs. high (n=165) verbal expertise group. Those in the low expertise group do not rate the verbal expertise of the FLE as high (M=2.29), which is the case for the high expertise group (M=6.02, t(338) =−28.75, p<.001). Finally, participants correctly assess whether the FLE did not wear a face mask (i.e. condition without face mask; n=160) or wore one (i.e. condition with face mask, n=180; Mno face mask=1.29 vs. Mface mask=6.90, t(338)=−60.89, p<.001).

To test hypothesis 1, that is, to examine whether customers correctly decode FLE emotion display in both the group with face mask and that without face mask, an independent samples t-test was run. Participants who were exposed to a smiling FLE who was not wearing a face mask, agree that the FLE smiled (M=6.52) compared to those in the non-smiling condition who disagree on that question (M=1.97, t(158)=−20.30, p<.001). Similarly, those in the smiling condition rate the facial expression as positive, which is not the case for those in the non-smiling condition (Msmiling=6.10 vs. Mnon-smiling=2.66, t(158)=−14.62, p<.001). These results are quite similar for those participants who were exposed to an FLE wearing a face mask. Those in the smiling condition confirm the service FLE to smile (M=5.64), which is not the case for their counterparts in the non-smiling condition (M=3.04, t(178)=−10.90, p<.001). Similarly, those in the smiling condition regard the FLE facial expression as positive (M=5.65) compared to the non-smiling condition (M=2.88, t(178)=−8.92, p<.001). Thus, based on these results, hypothesis 1 can be confirmed.

To test hypotheses 2 and 3, that is, to investigate whether the effect of FLE emotion display and verbal expertise on customer responses depend on the FLE is wearing a face mask or not, we applied several three-way ANCOVAs with FLE emotion display, verbal expertise and face mask as independent variables and customer well-being and face mask related feelings as covariates. Hypothesis 2 examines the direct effect of FLE non-smiling vs. smiling on customer responses dependent on whether the FLE is wearing a face mask or not. The results show that the interaction effect of FLE emotion display and face mask (no vs. yes) is significant for customer advice taking (F(1, 330) = 4.93, p<.05, η2=.02) and marginally significant for social rapport (F(1, 330) = 2.85, p<.10, η2=.01) and overall satisfaction (F(1, 330) = 3.00, p<.10, η2=.01). No significant interaction effect exists for WOM (F(1, 330) = 1.82, p>.10, η2=.00). The effects are in the hypothesized direction as post-hoc tests using multiple comparisons show that there is no difference regarding customer responses between smiling FLEs wearing a face mask and those not wearing a face mask (p>.10). Hypothesis 2a, b, and c can be supported for advice taking, social rapport and overall satisfaction; hypothesis 2d has to be rejected for WOM. However, under the condition of a non-smiling FLE, the face mask becomes relevant. Customer advice taking is higher given the FLE is wearing a face mask (Mwithout_face mask=3.13 vs. Mwith_mask=3.75, p<.05). Similarly, social rapport (Mwithout_face mask=3.02 vs. Mwith_mask=3.66, p<.001) and overall satisfaction are higher (Mwithout_face mask=3.25 vs. Mwith_mask=3.86, p<.05), providing support for hypothesis 2e. Both covariates do not play a significant role. When the face mask comes into play, FLE smiling does not differently affect customer responses; however, for non-smiling FLEs advice taking, social rapport and overall satisfaction are higher when the FLE is wearing a face mask. Hypothesis 3 examines the direct effect of FLE verbal expertise on customer responses dependent on wearing a face mask or not. The findings show that FLE verbal expertise has a significant impact on customer advice taking (F(1, 330) = 345.93, p<.001, η2=.51), social rapport (F(1, 330) = 177.65, p<.001, η2=.35), overall satisfaction (F(1, 330) = 304.07, p<.001, η2=.48), and WOM (F(1, 330) = 273.88, p<.001, η2=.45) both if the FLE is wearing a face mask or not since the interaction effects between FLE verbal expertise and face mask are not significant (p>.10). Furthermore, the effects are in the proposed direction since customer advice taking is higher given FLEs are experts in verbal communication (Mlow_expertise=2.60 vs. Mhigh_expertise=4.98, p<.001). The same applies to social rapport (Mlow_expertise=3.09 vs. Mhigh_expertise=4.97, p<.001), overall satisfaction (Mlow_expertise=2.48 vs. Mhigh_expertise=2.87, p<.001) and WOM (Mlow_expertise=2.58 vs. Mhigh_expertise=4.79, p<.001). Thus, hypothesis 3 can be confirmed. provides an overview of the means by the experimental conditions.

Table 4. Mean comparisons by experimental conditions.

To inspect the mediating role of customer emotional change in the link between FLE emotion display and verbal expertise on customer responses, and to do so dependent on the FLE wearing a face mask or not, we ran Process Modell 8 (Hayes, Citation2018; bootstrap=5000). We separately did do so for the face mask vs. no face mask condition with FLE emotion displays (non-smiling=0 vs. smiling=1) being used as independent variable and verbal expertise (low=0 vs. high=1) as moderator to test hypothesis 4. Customer emotional change was integrated as mediator and their well-being and face mask related feelings were considered as covariates.

Under the condition that the FLE is not wearing a face mask, the following results are found. First, FLE verbal expertise has a positive impact on customer emotional change (B=1.19, p<.001, CI95[.62 … . 1.77], R²=.31). Moreover, their emotion display has a marginally significant effect on this variable (B=.55, p<.10, CI95[−.03 … . 1.11], R²=.31). Having a closer look at this, it becomes evident that customer emotional change is positive under the condition of a FLE who is high in verbal expertise (M=.12). Contrarily, an FLE who is low in verbal expertise results in a negative emotional change (M=−1.33, p<.001). For FLE emotion display, customer change is more negative when being exposed to a non-smiling FLE compared to a smiling one (Mnon_smiling=−1.03 vs. Msmiling=−.22, p<.001). Customer emotional change further drives their advice taking (B=.37, p<.001, CI95[.24 … . .51], R²=.63), social rapport (B=.46, p<.001, CI95[.32 … . .60], R²=.61), overall satisfaction (B=.41, p<.001, CI95[.27 … . .54], R²=.59) and WOM (B=.40, p<.001, CI95[.26 … . .54], R²=.57). Thus, when not wearing a face mask both FLE emotion display and verbal expertise are relevant, with verbal expertise being more relevant for customer positive emotional change. We find support for a partial mediation of customer emotional change since the direct effects of FLE emotion display and verbal expertise remain significant (p<.05).

Given the FLE is wearing a face mask, the results show the following. While FLE emotion display does not have a significant impact on customer emotional change (B=.41, p> .10, CI95[−.11 … . .93], R²=.30), their verbal expertise does do so (B=1.57, p<.001, CI95[1.05 … . 2.10], R²=.30). A comparison of means confirms this. Customer emotional change in this case is not differently affected by a non-smiling (M=−.66) vs. smiling (M=−.27, p>.05) FLE. By contrast, customer emotional change is positive (M=.34) when being exposed to a verbal expert compared to a non-expert FLE (M=−1.23, p<.001). Furthermore, customer emotional change has a positive impact on customer advice taking (B=.33, p<.001, CI95[.21 … . .46], R²=.60), social rapport (B=.39, p<.001, CI95[.25 … . .52], R²=.57), overall satisfaction (B=.35, p<.001, CI95[.23 … . .46], R²=.65) and WOM (B=.36, p<.001, CI95[.23 … . .48], R²=.60). Customer well-being is a significant control in these models. Thus, customer emotional change partially mediates the impact of FLE verbal expertise on customer responses as the direct effect of verbal expertise on customer responses remains significant (p<.05), while under the condition of wearing a face mask, FLE emotion display is only relevant for social rapport, but does not drive customer emotional change. Hypothesis 4 can therefore be supported.

General discussion

Summary

This research provides new insights into the change of shopping behavior in times of the COVID-19 pandemic, and specifically, into the role of face masks in dyadic service interactions. Study 1 shows that shopping in stationary commerce has decreased and online shopping increased due to inconveniences caused by COVID-19. Overall, consumers are indifferent regarding their attitude toward wearing face masks; one half of the interviewees named positive while the other half reported negative attitudes. Besides others, face mask obligation entails some difficulties as the face mask disturbs customers both on a personal and interpersonal level. In service interactions, verbal and non-verbal communication becomes problematic, acoustically and due to the reduced possibility of showing facial expressions. This is a challenge for FLEs, as both verbal expertise and emotion display are of importance for successful service interactions.

Study 2 confirms Study 1’s results and further reveals that consumers both express negative associations with the face mask, their well-being and service interactions and positive associations, such as being in favor of an obligation to wear face masks. Even though consumers tend to limit their shopping to a minimum in time and frequency, almost half of the participants had already gone shopping apart from food shopping during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Study 3 specifically focuses on the questions whether face masks hinder customers to correctly identify FLE emotion displays, and consequently, their impact on customer emotional change and success metrics. Linked to this question, this research also investigates if FLE verbal expertise becomes more important compared to emotion displays when FLEs are wearing a face mask. In support of hypothesis 1, the results show that customers are able to correctly decode FLE emotion display. Furthermore, customer advice taking, social rapport and overall satisfaction are highest when FLEs are smiling both with and without face masks. Given a non-smiling FLE, customer responses are more positive when s/he is wearing a face mask, providing evidence that customers expect FLEs to smile, but when the face mask covers the FLE’s face, mixed results exist, in favor of hypothesis 2a-c and 2e. For WOM (hypothesis 2d) no effect is found which might be explained by the fact, that advice taking, social rapport and satisfaction are timely-related to the specific interaction, while WOM might develop afterward, that is, later in the post-encounter stage. Considering FLE verbal expertise, the findings show that its direct effect on customer responses is independent of the face mask as proposed by hypothesis 3. However, when simultaneously considering FLE emotion display, verbal expertise and face mask, the findings show that both verbal expertise and emotion display are relevant drivers of emotional change when the FLE is not wearing a face mask. By contrast, when wearing a face mask, only verbal expertise constitutes the decisive factor. In both cases, customer emotional change significantly influences customer responses providing evidence for a mediation effect. Thus, hypothesis 4 can be supported, too.

Theoretical implications

This research makes a number of contributions to theory. First, and most generally, this research responds to the need of investigating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic as well as related restrictions and hurdles on the individual shopping experience (Scott et al., Citation2020) by considering FLE emotion display and verbal expertise as drivers of customer responses (Marinova et al., Citation2018), and more importantly, to do so dependent on FLEs wearing a face mask or not. It thus contributes to the concepts of the customer journey and customer experience (Lemon & Verhoef, Citation2016).

Second, this paper contributes to the literature on emotions (Ekman, Citation1992) by investigating the role of face masks for the decoding of FLE emotion displays. In contrast to current assumptions (Carbon, Citation2020; Maeck, Citation2020; Spitzer, Citation2020), customers can correctly identify FLE emotion display even when wearing a face mask, which is possible based on the muscular activity in the face (i.e. the activation of specific AUs; Ekman et al., Citation2002). Thus, this result also supports previous research which claims that recipients merely focus on the area around the eyes (i.e. AU#6; Ekman et al., Citation2002) when identifying a Duchenne smile (Chartrand & Gosselin, Citation2005; Del Giudice & Colle, Citation2007; Lechner & Paul, Citation2019; Spitzer, Citation2020), and additionally shows that this even holds when FLEs are wearing a face mask.

Third, going one step further, and focusing on the impact of FLE emotion display on customer responses, this research contributes to the emotional labor literature (Hochschild, Citation2006). The results are in line with previous research on the impact of FLE emotion displays on customer responses by showing that customers expect FLEs to display positive emotions (Hennig-Thurau et al., Citation2006; Hochschild, Citation2006) and avoid negative or neutral ones (Ashforth & Humphrey, Citation1993; Zapf et al., Citation2005). Interestingly, the face mask helps to cover these unexpected non-smiling facial expressions and thus reduces its negative effect, which shows that face masks might increase positive outcomes in addition to the reduction of infection rates (Gray, Citation2020). By doing so, this research does not support the notion that face masks increase the perception of negative emotions (Spitzer, Citation2020). This research, therefore, extends the current knowledge of the impact of FLE emotional labor on customer responses (e.g. Hochschild, Citation2006) by taking the role of face masks into account.

Fourth, considering FLE expertise as verbal cue, this study adds to the literature on FLE problem solving (Marinova et al., Citation2018) and confirms the common opinion that verbally communicated competence and expertise are relevant to create superior service interactions (Agnihotri et al., Citation2016; Benbasat & Wang, Citation2005; Li et al., Citation2009; Marinova et al., Citation2018; Wood et al., Citation2008). However, in contrast to previous research, this study does not reveal that face masks hinder FLE verbal communication (Luximon et al., Citation2016). FLE verbally communicated expertise becomes even more relevant when wearing a face mask.

Managerial implications

The findings of three studies provide a sound basis for managerial implications. Regarding our first research question, we found that the shopping behavior of the individual consumer has noticeably changed in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Consumers shop even more online than before, but, interestingly, many of them still regularly use brick-and-mortar stores and want to do so in the future as well. Here, however, they shop faster, less frequently, more targeted, and buy only the most necessary. For management, this implies that it is especially important that the shopping experience during COVID-19 restrictions is improved as much and wherever possible. Retailers, therefore, need to enhance the offline customer experience to exceed the COVID-19 hurdles and retain customers. Shopping is a social experience; enjoyable interactions and a personal connection to the FLE are key to developing a relationship in service contexts (Hennig-Thurau et al., Citation2002). Thus, a personal and friendly relationship with the FLE is more important than ever. FLEs should maintain personal contact with their customers and create a form of social rapport. Private shopping times and personal in-store advice are also conceivable to give the customer a sense of appreciation and thereby improve the customer experience.

As long as stationary commerce is limited and online shopping is preferred by the customers, curated shopping and virtual experts might be a solution as they can positively change the customer experience (Parise et al., Citation2016; Sebald & Jacob, Citation2018). From live experts in video conferences to augmented reality technology, many approaches are possible. While smaller shops might offer personal video chats for their customers, bigger retailers could introduce new virtual expert technologies to their websites. Especially in such online service interactions the relevance of FLE verbal expertise and emotion display thus even increases for the creation of a superior customer experience.

All studies show that face masks and other safety features have played an important role in dyadic service interactions during the COVID-19 pandemic. While the studies demonstrate that many individuals have a rather positive general attitude towards the obligation to wear face masks, a number of negative associations appear, such as discomfort and physical restrictions. Additionally, the qualitative studies reveal that wearing face masks in dyadic service interactions induces some difficulties in verbal and non-verbal communication. The quantitative study, however, provides evidence that face masks do not inhibit the customer to correctly identify FLE emotions and thus, under certain conditions, positive effects on customer emotions and company success can be reported. FLEs must be trained well in three ways. First, to enhance verbal expertise, a proper pronunciation of words and concise sentences could improve understanding. From clinical research, we can learn that tailoring information and regularly checking on the customer’s understanding represent key tasks for good verbal communication (Maguire & Pitceathly, Citation2002). Second, since face masks cover the lower half of the face, FLEs need to learn how to ‘smile with their eyes.’ Positive emotion displays such as a smile must be deep and authentic since these smiles (i.e. a Duchenne smile) can be recognized by looking at the eyes and generally lead to more positive customer responses (Hennig-Thurau et al., Citation2006; Lechner & Paul, Citation2019). Third, as face masks make you seem less friendly, FLEs must be able to create a feeling of warmth in the personal interaction with the customer. This can, for instance, be achieved by showing interest in as well as acceptance and approval of customers (Sundaram & Webster, Citation2000). To fulfill all these requirements in verbal and non-verbal communication, FLEs can be trained by communication coaches.

While the findings propose that face masks do not inhibit the correct decoding of FLE emotion displays, we also see that face masks do not play a crucial role for customer responses when FLEs are smiling, however, when they do not smile, a face mask leads to better results compared to the FLE not wearing one. Thus, service management especially needs to know two points from these findings: First, face masks do not reduce the relevance and impact of FLE emotional labor in the sense of smiling. Even when FLEs are supposed to wear face masks, they need to focus on an authentic smile because this leads to superior outcomes in terms of advice taking, social rapport and overall satisfaction. Second, when FLEs are not able to smile, a face mask helps to offset the negative effects arising from the non-smiling facial expression which does not meet customer expectations in terms of emotional labor (Hochschild, Citation2006).

The quantitative study further suggests that FLE verbal expertise gains relevance when the FLE is wearing a face mask. That is, although customers can correctly decode FLE emotion displays which have an impact on customer emotional change and responses, considering FLE verbal expertise shows that high levels of expertise help to increase customer positive emotions, especially when wearing a face mask. Therefore, service management necessarily needs to focus on knowledgeable and competent FLEs who know their job and know how to create successful service interactions. As a result, personnel development programs might help to anchor smiling facial expressions and verbal expertise as job requirements even under stressful conditions (e.g. the obligation to wear a face mask).

Limitations and future research

Although this research provides state-of-the-art knowledge on changes in shopping behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic with a special focus on the effects of face masks, there are a number of interesting avenues for future research. While our quantitative study considered FLE emotion display and verbal expertise when wearing a face mask versus not wearing a face mask as drivers of customer emotions and resultant responses, further research could look into the relevance of other verbal and nonverbal factors, such as the tone of the voice or the FLE gestures. Even though experimental studies are usually unproblematic in terms of common-method bias (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003), a reversed mediator-dependent variable relationship could be further investigated. Additionally, a validation of our findings in other service contexts would be valuable, for example, those that are high in involvement such as healthcare services or those that are low in involvement such as short quick-and-collect service interactions. Moreover, a field study in a retail store could add additional insights since people might show different behavior in the actual field compared to an experimental condition. Thus, to increase external validity, a validation of our results through a field study would be desirable. Of course, COVID-19 restrictions and time limitations provide large hurdles for doing so.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Accenture. (2020, April 28). Accenture COVID-19 consumer research. Retrieved July 16, 2020 from: https://www.accenture.com/sk-en/insights/consumer-goods-services/coronavirus-consumer-behavior-research

- Agnihotri, R., Vieira, V. A., Senra, K. B., & Gabler, C. B. (2016). Examining the impact of salesperson interpersonal mentalizing skills on performance: The role of attachment anxiety and subjective happiness. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 36(2), 174–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/08853134.2016.1178071

- Ahgz. (2020, June 6). Das Lächeln hinter der Maske. [Smiling behind the face mask]. Retrieved July 17, 2020 from: https://www.ahgz.de/news/mitarbeiter-das-laecheln-hinter-der-maske,200012262942.html

- Ashforth, B. E., & Humphrey, R. H. (1993). Emotional labor in service roles: The influence of identity. Academy of Management Review, 18(1), 88–115. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1993.3997508

- Barger, P. B., & Grandey, A. A. (2006). Service with a smile and encounter satisfaction: Emotional contagion and appraisal mechanisms. Academy of Management Journal, 49(6), 1229–1238. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.23478695

- Benbasat, I., & Wang, W. (2005). Trust in and adoption of online recommendation agents. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 6(3), 72. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00065

- Bonaccio, S., & Dalal, R. S. (2006). Advice taking and decision-making: An integrative literature review, and implications for the organizational sciences. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 101(2), 127–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.07.001

- Brady, M. K., & Cronin Jr, J. J. (2001). Some new thoughts on conceptualizing perceived service quality: A hierarchical approach. Journal of Marketing, 65(3), 34–49. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.65.3.34.18334

- Carbon, C. C. (2020). Wearing face masks strongly confuses counterparts in reading emotions. Preprint: 10.31234/osf.io/sd5mj.

- Carbon, C. C., Grüter, M., & Grüter, T. (2013). Age-dependent face detection and face categorization performance. PLoS One, 8(10), e79164. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0079164

- Chang, C. H., Lin, P. C., Kuan, T. W., Chen, J. M., Lin, Y. C., Wang, J. F., & Tsai, A. C. (2014, September 20–23). Multi-level smile intensity measuring based on mouth-corner features for happiness detection. 2014 International conference on orange technologies (pp. 181–184). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICOT.2014.6956629

- Chartrand, J., & Gosselin, P. (2005). Jugement de l'authenticité des sourires et détection des indices faciaux. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology/Revue Canadienne de Psychologie Expérimentale, 59(3), 179. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0087473

- Chi, N. W., Grandey, A. A., Diamond, J. A., & Krimmel, K. R. (2011). Want a tip? Service performance as a function of emotion regulation and extraversion. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(6), 1337. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022884

- Coelho, F., & Augusto, M. (2008). Organizational factors associated with job characteristics: Evidence from frontline service employees. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 16(2), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/09652540801981595

- de la Rosa, S., Fademrecht, L., Bülthoff, H. H., Giese, M. A., & Curio, C. (2018). Two ways to facial expression recognition? Motor and visual information have different effects on facial expression recognition. Psychological Science, 29(8), 1257–1269. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797618765477

- Delcourt, C., Gremler, D. D., van Riel, A. C., & Van Birgelen, M. J. (2016). Employee emotional competence: Construct conceptualization and validation of a customer-based measure. Journal of Service Research, 19(1), 72–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670515590776

- Del Giudice, M., & Colle, L. (2007). Differences between children and adults in the recognition of enjoyment smiles. Developmental Psychology, 43(3), 796. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.796

- Du, J., Fan, X., & Feng, T. (2011). Multiple emotional contagions in service encounters. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(3), 449–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-010-0210-9

- DW. (2020, May 19). Lächeln mit Mundschutz - Schau mir in die Augen: Wie Verständigung trotz Corona-Maske funktioniert. [Smile with face mask – How communication works with face mask]. Retrieved July 17, 2020 from: https://www.dw.com/de/schau-mir-in-die-augen-wie-verst%C3%A4ndigung-trotz-corona-maske-funktioniert/a-53486869

- Echterhoff, G., Schreier, M., & Hussy, W. (2013). Forschungsmethoden in Psychologie und Sozialwissenschaften für Bachelor [Research methods in psychology and social science for Bachelor students], 2., überarbeitete Auflage. Inprint Springer, Berlin & Heidelberg.

- Ekman, P. (1992). Are there basic emotions. Psychological Review, 99(3), 550–553. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.99.3.550

- Ekman, P., Friesen, W. V., & Hager, J. C. (2002). Facial action coding system – Investigator’s guide, eBook for pdf Readers. Network Information Research Corporation.

- Elfenbein, H. A. (2014). The many faces of emotional contagion: An affective process theory of affective linkage. Organizational Psychology Review, 4(4), 326–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041386614542889

- Ericsson, K. A., & Smith, J. (1991). Toward a general theory of expertise: Prospects and limits. Cambridge University Press.

- Fernandez-Dols, J. M., & Ruiz-Belda, M. A. (1995). Are smiles a sign of happiness? Gold medal winners at the Olympic Games. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(6), 1113. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.6.1113

- Fornell, C., Johnson, M. D., Anderson, E. W., Cha, J., & Bryant, B. E. (1996). The American customer satisfaction index: Nature, purpose, and findings. Journal of Marketing, 60(4), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299606000403

- Fortin, J. (2020, June 23). Masks keep us safe. They also hide our smiles. Retrieved July 16, 2020 from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/23/style/face-mask-emotion-coronavirus.html

- Gabbott, M., & Hogg, G. (2001). The role of non-verbal communication in service encounters: A conceptual framework. Journal of Marketing Management, 17(1-2), 5–26. https://doi.org/10.1362/0267257012571401

- Giebelhausen, M., Robinson, S. G., Sirianni, N. J., & Brady, M. K. (2014). Touch versus tech: When technology functions as a barrier or a benefit to service encounters. Journal of Marketing, 78(4), 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.13.0056

- Gosselin, P., Perron, M., & Beaupré, M. (2010). The voluntary control of facial action units in adults. Emotion, 10(2), 266. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017748

- Grandey, A. A., Fisk, G. M., Mattila, A. S., Jansen, K. J., & Sideman, L. A. (2005). Is service “with a amile” enough? Authenticity of emotion displays during service encounters. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 96(1), 38–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2004.08.002

- Gray, R. (2020, July 2). Why we should all be wearing face masks. Retrieved July 16, 2020 from: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200504-coronavirus-what-is-the-best-kind-of-face-mask

- Gremler, D. D., & Gwinner, K. P. (2008). Rapport-building behaviors used by retail employees. Journal of Retailing, 84(3), 308–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2008.07.001

- Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903

- Harrison-Walker, L. J. (2001). The measurement of word-of-mouth communication and an investigation of service quality and customer commitment as potential antecedents. Journal of Service Research, 4(1), 60–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/109467050141006