Abstract

Brand placements are a widely used advertising technique in entertainment media such as movies or TV shows. Yet, the presented brand placements do not always portray real brands. In media content like comedies, brand placements are occasionally spoof brands, which humorously mimic the real brand in their name and logo. Yet, how spoof brand placements might spill over to the referenced real brand and how viewers process spoof brand placements has never been tested. We recruited 200 participants between the ages of 16 to 66 to take part in an empirical examination. With a one-factorial experimental design (no brand references vs. real brand placement vs. spoof placement), we examined the effects of spoof placements on brand recall, activation of conceptual persuasion knowledge, and brand evaluation. We found that spoof brands significantly affect explicit brand memory of the referenced, real brand; however, they do not activate conceptual persuasion knowledge to the same extent as real brand placements do. We did not find an effect of our three conditions on brand evaluation of the real brand.

Introduction

In the movie ‘The Flintstones,’ Fred and his family eat their burgers at Roc Donald’s. Shrek can grab a coffee at Farbucks, while the Simpsons family visits the Mapple Store and listens to music on their MyPods. All of these brand or product placements (Balasubramanian, Karrh, and Patwardhan Citation2006) use the signifying fonts and color schemes of the referenced brands, but slightly change the name or designation to fit the scenery of the series ore movie (Naderer, Matthes, and Spielvogel Citation2019). This type of mimicry brand integration is commonly referred to as a spoof (Sutherland et al. Citation2011). Spoofs are, on the one hand, an instrument of parody that mimics the real world in a humorous manner. On the other hand, spoofs allow the referencing of real brands in settings where embedded advertising is restricted. The European Union, for instance, has clear regulations on how brands are allowed to be integrated in audiovisual and audio content and what kind of programs should be free from such advertising messages. Accordingly, broadcasters are not allowed to display brand placements in the designated children’s programs or news programs (Audiovisual Media Services Directive (AVMSD) Citation2010). However, to the authors’ knowledge, brand creations, like fake brands (e.g. Bertie Bott's Beans in ‘Harry Potter’) or spoofs, are not explicitly included in this regulation nor in any other embedded advertising regulations. Thus, integrating spoofs in content that is strictly regulated with regard to real brand placements is certainly not off limits. Moreover, while the referenced brands are never explicitly portrayed in spoof placements, the question remains whether these brand presentations can have an impact on brand outcomes for the referenced, real brand.

With the present study, we want to tackle this research gap and examine how spoof placements impact brand memory and the assessment of a real brand. Furthermore, as spoof placements are often created in a humorous, parodying manner, spoofs might not be processed like traditional brand placements. This is because humor can have a distracting impact, which diverts viewers’ attention from recognizing the persuasive intent (see, for instance, Strick et al. Citation2012). Hence, spoofs might not trigger an activation of conceptual persuasion knowledge as commonly shown for prominent brand placements of real brands (Matthes and Naderer Citation2016; van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2015).

With the present study, we examine the role of spoof placements with an experimental design, comparing a real brand placement, a spoof placement, and the same stimulus showing no brand references. We investigate the impact of the placement presentations on brand recall of the real, respectively referenced spoof brand, the activation of conceptual persuasion knowledge, and the brand evaluation of the real, respectively referenced brand.

Effects of brand placements

Brand or product placements typically describe the advertising technique of embedding existing brands in entertaining content such as movies, TV series, or computer games (Balasubramanian, Karrh, and Patwardhan Citation2006; van Reijmersdal Citation2009). Depending on the type of brand presentations, four possible outcomes of product placements have been identified and examined (Yang and Roskos-Ewoldsen Citation2007): memory traces for the embedded brand (e.g. Gupta and Lord Citation1998), recognition of the persuasive intent of the brand placements (i.e. activation of conceptual persuasion knowledge; van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2015), effects regarding the evaluation of the inserted brand (e.g. Kamleitner and Jyote Citation2013), and conative outcomes (e.g. Auty and Lewis Citation2004). In the following, we will discuss memory traces, activation of persuasion knowledge, and brand evaluation effects in more detail.

Brand placement effects on brand memory

The existing body of literature indicates that brand placements can affect brand memory (e.g. Gupta and Lord Citation1998; Kamleitner and Jyote Citation2013; Russell Citation2002). Memory traces for brand placements are especially likely if a brand is integrated prominently (see Balasubramanian, Karrh, and Patwardhan Citation2006; Matthes, Schemer, and Wirth Citation2007; van Reijmersdal Citation2009). Memory traces for less-obtrusive brand presentation are far less likely. However, this does not mean that these types of placements do not affect other brand-related outcomes (for a more thorough discussion on this matter, see Matthes et al. Citation2012).

In fact, prominent brand placements (defined as being frequently placed, clearly noticeable, or shown in interaction with a character; see Gupta and Lord Citation1998) have been continuously shown to generate a relatively high level of brand recall. Hence, under the premises that a brand placement is embedded in a prominent way, it can be assumed that viewers will be able to recall the integrated brand (Gupta and Lord Citation1998; Kamleitner and Jyote Citation2013; Matthes and Naderer Citation2016; Naderer, Matthes, and Zeller Citation2018b; Russell Citation2002):

H1: If a real brand placement is presented prominently, viewers will be able to recall the embedded real brand name to a higher extent compared to viewers in the control condition, who did not see a brand placement.

Until now, we, however, lack insights into whether spoof brands, which mimic the real brand’s name and presentation style, might elicit similar memory effects as the real brand placement. Spoof brands are usually built on references for brands that are already very popular (Sutherland et al. Citation2011) but are not building a reputation for themselves as brands created for the purpose of a movie or series, like for instance Duff Beer from ‘The Simpsons’ (Muzellec, Lynn, and Lambkin Citation2012). Therefore, building on priming theory, one might assume that spoof placements serve as a prime for the referenced, real brand (Balasubramanian, Karrh, and Patwardhan Citation2006). Hence, the presentation of a spoof makes memory traces for the existing brand more available, and subsequently heightens the audience’s explicit memory for the referenced, real brand. We assume that viewers might build on the familiarity with the existing brands and consequently recall the referenced brands’ names rather than being able to indicate the spoof name. As there is no empirical evidence for this fact until now, we refrain from formulating a hypothesis and instead ask:

RQ1: How do spoof placements affect brand recall for the referenced brand relative to the real brand and no brand placement conditions?

Brand placement effects on conceptual persuasion knowledge

In addition to creating awareness for the brand name, existing research points to the fact that viewers’ identification of a brand increases their awareness of the persuasive attempt (e.g. Matthes and Naderer Citation2016). This awareness is typically connected to the activation of conceptual persuasion knowledge. Following the Persuasion Knowledge Model (PKM) by Friestad and Wright (Citation1994), persuasion knowledge is described as a specific processing of a persuasive message. In particular, persuasion knowledge can be distinguished in two responses: attitudinal and conceptual persuasion knowledge (Boerman, van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2012). Attitudinal persuasion knowledge refers to the perception of trustworthiness of a persuasive message, e.g. a brand presentation. Conceptual persuasion knowledge assesses the extent to which a persuasive message like a brand placement is actually seen as advertising (Ham, Nelson, and Das Citation2015). In our study, we are particularly interested in the realization of viewers that a brand placement is advertising. Consequently, we focus on the activation of conceptual persuasion knowledge (Wright, Friestad, and Boush Citation2005).

If adult viewers are confronted with prominent brand placements of real brands, the existing body of literature commonly indicates that viewers activate their conceptual persuasion knowledge, as the prominence serves as an indicator of the persuasive intent (e.g. Matthes and Naderer Citation2016; van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2015). We would therefore assume that a prominent placement of a real brand would activate viewers’ conceptual persuasion knowledge to a higher extent compared to no brand references:

H2: If a real brand placement is presented prominently, viewers will activate their conceptual persuasion knowledge to a higher extent compared to viewers in the control condition, who did not see a brand placement.

Spoof brand placements compared to real brand placements are typically created in a humorous, parodying manner (Sutherland et al. Citation2011). However, while the motivation behind spoof placements can be an entertaining presentation of an existing brand planned by writers of a show or movie (e.g. the Mapple Universe as a parody of Apple in ‘The Simpsons’ series, Watercutter Citation2014), it can also be part of a full-fledged marketing strategy. The example of ‘The Flintstones’ presentation of McDonald’s as Roc Donald’s in the introduction was actually part of a marketing campaign by McDonald’s (Yeshin Citation1998). Hence, even though the brand itself was not accurately presented in the movie, McDonald’s in fact sponsored the humorous placement of the brand as a Stone-Age version of the fast-food restaurant.

Whether it is a creator’s decision or a marketing campaign, the brand is presented as a non-accurate version of itself, but in one case, this parody was purchased in order to appear this way (‘The Flintstones’); in the other, it was not (‘The Simpsons’). From the consumers’ point of view, however, it is nearly impossible to tell the difference. While it is already assumed that it is rather challenging to recognize real brand placements as the marketing strategy they pose (e.g. Hudson, Hudson, and Peloza Citation2008), recognizing spoof placements as advertising might be even more difficult. It is unclear how viewers will deal with spoof placements in their processing of the placement presentation. One might assume that due to the close proximity to the real brand and the often very prominent integration (Naderer, Matthes, and Spielvogel Citation2019), spoof placements are treated in the same way as a real, obtrusive brand placement (Matthes, Schemer, and Wirth Citation2007; van Reijmersdal Citation2009). Hence, conceptual persuasion knowledge might be triggered (Friestad and Wright Citation1994). One might, however, also assume that due to the humorous manner of brand presentations, and the perceived mimicry of a real brand, spoof placements are not actually seen as a persuasive message, and do not activate viewers’ conceptual persuasion knowledge. This assumption is in part based on the premise that humor is able to reduce our defenses and can therefore break our resistance to persuasive messages (Strick et al. Citation2012). As we do not have any indications so far on how spoof placements might be processed by viewers, we ask:

RQ2: How do spoof placements affect conceptual persuasion knowledge relative to the real brand and no brand placement conditions?

Brand placement effects on brand evaluation

Furthermore, studies suggest that brand placements may have attitudinal consequences, which are characterized by changes in brand evaluations and purchase intentions (e.g. Kamleitner and Jyote Citation2013; Knoll et al. Citation2015; Matthes, Schemer, and Wirth Citation2007) as well as conative outcomes, which are gauged through actual brand choice or product consumption (e.g. Auty and Lewis Citation2004; Beaufort Citation2019; Naderer et al. Citation2018a, Naderer, Matthes, and Zeller Citation2018b). The essential goal of marketing techniques like brand placement is to positively influence brand evaluations and to achieve an increase in sales. Whether all brand placements are equally successful in doing so is still under investigation.

Some studies have indicated that brand placements can have positive attitudinal consequences (e.g. Kamleitner and Jyote Citation2013; Knoll et al. Citation2015). These positive brand outcomes are commonly explained by emotional conditioning theory (e.g. Kroeber-Riel Citation1984). The theory posits that the effects of an entertaining content or context can be transmitted onto embedded persuasive messages (Balachander and Ghose Citation2003). Thus, it is assumed that the enjoyment of entertaining content such as a movie or TV series can positively affect the evaluation of the presented brand. This is why brand placements are often found in comedies (Naderer, Matthes, and Spielvogel Citation2019; Sutherland et al. Citation2011). Similar to the emotional conditioning process, placements that are presented prominently, for instance, by being presented in an interaction with a character, have been shown to create a meaning transfer from the character to the brand. Therefore, likeable characters can transmit their positive connotations to the brand. This mechanism is based on the theory of evaluative conditioning (De Houwer, Thomas, and Baeyens Citation2001; Knoll et al. Citation2015; Schemer et al. Citation2008; Sweldens, Van Osselaer, and Janiszewski Citation2010). Yet, the question is raised whether placement prominence, while typically beneficial for brand memory, is also always best for brand evaluation as this might also elicit negative effects (van Reijmersdal Citation2009). For instance, Dens et al. (Citation2012) indicated that brand placements are most effective if they are highly integrated into the plot but in a rather subtle manner. This is based on the assumption that too much focus on the brand may draw attention away from the message of the content and consequently raise the viewers’ suspicions (Bhatnagar, Aksoy, and Malkoc Citation2003). In addition, building on the mere exposure explanation (Zajonc Citation1968), frequent but subtle brand presentations might be particularly successful in building positive brand evaluations, while overly prominent placements might deteriorate these positive effects (Matthes et al. Citation2012). Developing a negative evaluation of the placed brand due to a prominent integration may furthermore depend on how familiar the viewers are with a character who is presenting a brand (Verhellen, Dens, and De Pelsmacker Citation2013) and how familiar viewers are with the presented brand itself (Verhellen, Dens, and De Pelsmacker Citation2016).

The existing body of literature, therefore, points to positive as well as negative evaluation effects of brand placement presentations (e.g. Kamleitner and Jyote Citation2013). The context of the content, the type of presentation and integration, the related characters, and viewers’ individual characteristics determine whether the presented brand is evaluated positively or negatively. Based on the complexity of assessing brand evaluation effects, we refrain from formulating a hypothesis and instead pose the following research question:

RQ3: How do real brand placements affect brand evaluations relative to the no brand placement condition?

As there is no research to date investigating the effects of spoof placements on brand evaluations, we furthermore ask:

RQ4: How do spoof placements affect brand evaluations relative to the real brand and no brand placement conditions?

Extant research has also indicated that an increase in conceptual persuasion knowledge may diminish potential positive marketing outcomes (Boerman, van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2012; Matthes, Schemer, and Wirth Citation2007; van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2015). It is assumed that, due to the activated conceptual persuasion knowledge, a disapproving processing of the persuasive content might be initiated. Previous research has shown that the conceptualization of a message as advertising is associated with triggering negative attitudes and annoyance (e.g. Mittal Citation1994; Moriarty and Everett Citation1994). Furthermore, Friestad and Wright (Citation1994) pointed out that realizing the persuasive intent results in a change of meaning of a message, which in turn has been frequently connected to negative effects on brand evaluations (Evans et al. Citation2017; Hwang and Jeong Citation2016; Liljander, Gummerus, and Söderlund Citation2015).

In other words, the mentioned negative association of categorizing a message as advertising might translate into a decline of the brand evaluation. However, research results have been inconsistent on whether that actually is always the case. Many studies examining the relationship of conceptual persuasion knowledge and the following assessments of the promoted brands have found that understanding the persuasive intent on a conceptual level does not automatically lead to a more critical assessment of the presented brand (e.g. Avramova, De Pelsmacker, and Dens Citation2018; Matthes and Naderer Citation2016; Wei, Fischer, and Main Citation2008).

With our study, we want to examine both the direct impact of the brand placements on brand evaluation (RQ3, 4) as well as the potential indirect path via conceptual persuasion knowledge. Based on what is known from extant research on the depictions of real brand placements compared to no placement depictions on the increase of persuasion knowledge (e.g. Matthes and Naderer Citation2016; van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2015), we assume that the real brand activates conceptual persuasion knowledge. Conceptual persuasion knowledge, in turn, could mediate the effect of real brand placement on brand evaluation and thus lead to a change in the brand evaluation of a real brand. As the direction of this change is not clear from extant research, we ask:

RQ5: Is the effect of the real brand relative to the control condition on brand evaluation mediated by activation of conceptual persuasion knowledge?

Furthermore, as there is no research to date investigating spoof placements and how they impact conceptual persuasion knowledge and brand assessments, we ask:

RQ6: Is the effect of the spoof brand relative to the real brand and the control condition on brand evaluation mediated by activation of conceptual persuasion knowledge?

Method

We conducted a 3 × 1 online-survey experiment with a convenience sample of N = 200 participants in Austria between the age of 16 to 66 (M = 26.84 years; SD = 6.28). Of the participants, 61% (n = 122) were female and 54.5% (n = 109) had obtained a college degree. In our study, we manipulated the type of brand placement, presenting either a real brand (n = 72), a spoof of this real brand (n = 63), or no brand (n = 65).

Stimulus

As a stimulus, we used an existing episode of ‘The Simpsons’ (season 21, episode 11). This episode contained a prominent spoof placement of Funtendo Zii. This placement referenced the Nintentdo Wii console. Within the episode, the product was presented several times and was interacted with, showing its features. A professional programmer reworked the existing episode to create three different versions of the stimulus. The participants in the spoof condition saw a shortened version (approximately 6 min.) of the original ‘The Simpsons’ episode. In the real brand condition, the images of the spoof were replaced with images of the referenced brand, Nintendo Wii. Other than that, participants saw the exact same shortened version of the ‘The Simpsons’ episode. The same procedure was employed for the control condition; however, here, the images of the spoof were replaced with a sign reading ‘Fit Konsole.’ Instead of providing a brand, a generic product description was presented to the viewers.

Pretest

We conducted a pretest (n = 45) of the stimulus to ensure that all three creations were perceived at the same level of professionalism and authenticity. We asked participants to rate the stimulus material with three statements on a six-point semantic scale (e.g. I think the episode I just saw… would not be aired like that on TV = 1—would definitely be aired like this on TV = 6; Cronbach’s Alpha = .76; M = 4.57; SD = 1.02). The pretest indicated that viewers perceived all three versions of the movie to be equally professional and realistic (F (2, 42) = 0.63; p = .537). Hence, we deemed this material to be appropriate to employ in the main study.

Measures

Subsequent to stimulus exposure, we measured participants’ brand recall as our first dependent variable. Participants were asked to freely indicate any brand names they saw in the stimulus. We assessed the brand recall of the target brand, Nintendo, within the conditions. We dummy-coded all responses that named Wii, Nintendo Wii, or Nintendo as = 1, whereas all other answers were coded as = 0. As our mediator, we measured participants’ conceptual persuasion knowledge (four statements: ‘I was under the impression that “The Simpsons” episode was sponsored by brands;’ ‘Presumably, the episode’s goal was to raise awareness for brands;’ ‘Brands apparently played an important role in this episode:’ ‘The producers tried to integrate brands into the story plot of the episode;’ 1 = I don’t agree; 6 = I completely agree; Cronbach’s Alpha = .84; M = 4.05; SD = 1.15; Matthes and Naderer Citation2016). As our dependent variable, we assessed participants’ brand evaluation of the brand Nintendo (five statements on a semantic differential scale; e.g., Would you assess Nintendo to be…; 1 = negative, unattractive, uninteresting, dislikeable, unpleasant; 6 = positive, attractive, interesting, likeable, pleasant; Cronbach’s Alpha = .92; M = 4.47; SD = 1.09; Matthes and Naderer Citation2016). The scales were one-dimensional based on Principal Component Analysis (see Carpenter, Citation2018).

As other relevant variables, we wanted to examine in a randomization check, we assessed the liking of the stimulus and familiarity with the presented stimulus and brand. We measured participants’ liking of the stimulus with four statements on a semantic differential scale (e.g., Would you say the episode you just saw was… 1 = humorless, boring, uninteresting, monotonous; 6 = funny, entertaining, interesting, varied; Cronbach’s Alpha = .91; M = 4.25; SD = 1.09). Familiarity with the specific ‘The Simpsons’ episode was measured with a binomial variable (0= not familiar, 1 = familiar). Results indicate that 30% (n = 60) were already familiar with the specific episode we employed for our study. In addition, we asked about their personal familiarity with Nintendo by asking if they owned a console and if so, what kind of console they owned. We recoded their indications as 0 = other or no console (85.5%, n = 171) or 1 = Nintendo console (14.5%, n = 29).

Results

Randomization check

A randomization check for gender (χ2 = 2.39, df = 2, N = 200, Φ = .11, p = .302), age (F (2, 197) = 0.47; p = .626), liking of the stimulus (F (2, 197) = 0.43; p = .701), familiarity with the presented episode (χ2 = 2.29, df = 2, N = 200, Φ = .11, p = .318), and familiarity with Nintendo (χ2 = 3.39, df = 2, N = 200, Φ = .13, p = .184) indicated no differences for these variables between our three conditions. Hence, our randomization check was deemed successful.

Hypotheses tests

Analysis

We tested our proposed hypotheses and research questions by looking into the potential main effects of the conditions on our outcome variables. Thus, we conducted a chi-square analysis and logistic regression analysis to examine the effects on brand recall (hypothesis 1 and research question 1). To examine the main effects on our mediator conceptual persuasion knowledge (hypothesis 2 and research question 2) and our dependent variable brand evaluation (research questions 3 and 4), we conducted ANOVAs. To test the proposed mediation process of research questions 5 and 6, we furthermore used the SPSS Macro PROCESS, Model 4 involving 1,000 bootstrap samples (Hayes Citation2018).

Main effect on brand recall

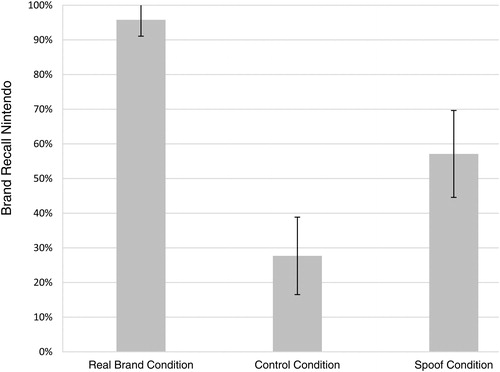

We examined the main effects of the experimental conditions on the participants’ recall of the target/referenced brand, Nintendo. Over half of the sample, 61% (n = 122) recalled the brand Nintendo. The overall difference in the recall of the groups was significant (χ2 = 67.73, df = 2, N = 200, Φ = .58, p < .001). In the real brand condition, 95.8% (n = 69) of all participants correctly recalled Nintendo. The remaining 4.2% (n = 3) could not recall any brand or named a brand that was not displayed (i.e., Apple). In the spoof condition that presented the spoof reference of Nintendo, also 57.1% (n = 36) of our participants recalled Nintendo even though they had actually seen Funtendo Zii. In comparison, only 33.3% (n = 21) of the participants in the spoof condition indicated the spoof name, and 9.5% (n = 6) indicated no fitting brand name or no brand at all. For the control group, still 27.7% (n = 18) of our participants recalled Nintendo. This considerable number of recall in the control group speaks to the fact that even a generic product description as given in the control group (the product was labeled ‘Fit Konsole’) seems to be able to awaken some kind of association with a real brand. When we examined the results in detail, we found that 38.5% (n = 25) named the product indication they had actually seen (i.e. ‘Fit Konsole’) The remaining 33.8% (n = 22) of the participants in the control condition indicated no fitting brand name or no brand at all. For an overview of the descriptive results of brand recall for the real brand name, Nintendo Wii, see .

We conducted a logistic regression analysis to examine the differences between the conditions further. In line with our hypothesis 1, real brand references elicited a significantly higher brand recall for the real brand Nintendo compared to the control condition (b = 4.10, SE = .65; Wald χ2 = 39.49, p < .001). Answering research question 1, we furthermore found that spoof placements elicited significantly lower levels of brand recall of the referenced brand compared to the real brand condition (b = −2.85, SE = .64; Wald χ2 = 19.65, p < .001), however, also significantly higher levels of brand recall compared to the control condition (b = 1.25, SE = .38; Wald χ2 = 10.99, p = .001). This indicates that spoof placements have a likelihood to create brand memory in a free association test for over half the viewers, and hence they can be evaluated as a successful tool to create brand awareness for real brands.

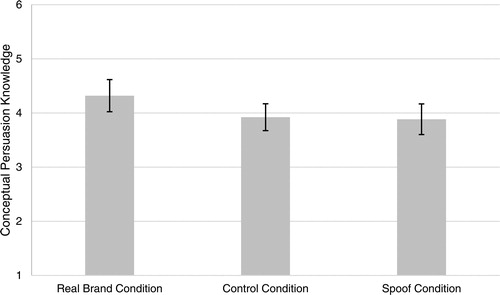

Main effect on persuasion knowledge

To examine our hypothesis 2 and our research question 2, we analyzed our mediator variable conceptual persuasion knowledge. We found a significant difference between the conditions (F (2, 197) = 3.08; p = .048). Lending support to hypothesis 2, participants in the real brand condition activated their conceptual persuasion knowledge significantly more (M = 4.32; SD = 1.26) compared to the control group (M = 3.92; SD = 1.00; p = .043). In addition, we found that the conceptual persuasion knowledge of participants in the real brand condition was significantly higher compared to the spoof condition (M = 3.89; SD = 1.12; p = .028). However, the spoof and the control condition did not significantly differ from each other (p = .850). For a visualization of the difference between conditions, see .

Main effect on brand evaluation

As a next step, we analyzed the main effects of the experimental conditions on brand evaluation. The overall difference between the groups was not significant (F (2, 197) = 0.06; p = .955). Answering research question 3, the brand evaluation did not differ between the real brand condition (M = 4.44; SD = 1.21) and the control group (M = 4.48; SD = 1.02; p = .857). Answering research question 4, there was no difference in the brand evaluation between the real brand condition and the spoof condition (M = 4.50; SD = 1.04; p = .763). Also, the control condition and the spoof condition did not differ from each other (p = .905).

Mediation process

To examine the mediation process on brand evaluation via conceptual persuasion knowledge, we conducted a mediation analysis with PROCESS (Hayes Citation2018). In a first step, we treated the real brand condition as the reference group. As described in the examination of the main effect above, we found that participants’ conceptual persuasion knowledge was significantly lower in the control group compared to the real brand condition (b = −.40; LLCI = −0.78; ULCI = −0.01; p = .043). We furthermore found no direct effects of the control condition compared to the real brand condition on brand evaluation (control condition: b = .08; LLCI = −0.30; ULCI = 0.45; p = .674). Answering research question 5, participants’ conceptual persuasion knowledge was not connected to brand evaluation (b = .12; LLCI = −0.02; ULCI = 0.25; p = .094). Thus, participants’ heightened conceptual persuasion knowledge due to the presentation of a real brand did not mediate the effects on brand evaluation compared to the control condition (b = −.05; SE = .04; LLCI = −0.15; ULCI = 0.01). For an overview of the results see . To examine our research question 6, we ran the same model again. This time we treated the spoof condition as a reference group. As reported in the main effect analysis above, we found that the real brand condition showed higher levels of conceptual persuasion knowledge compared to the spoof condition (b = .44; LLCI = 0.05; ULCI = 0.82; p = .028). The spoof condition and the control group did not differ in the level of conceptual persuasion knowledge (b = .04; LLCI = −0.36; ULCI = 0.44; p = .850). In addition, we did not observe any main effects of the real brand condition (b = −.11; LLCI = −0.48; ULCI = 0.27; p = .576) or the control condition on brand evaluation compared to the spoof condition (b = −.03; LLCI = −0.41; ULCI = 0.35; p = .887). Furthermore, the indirect paths were not significant (real brand condition: b = .05; SE = .04; LLCI = −0.02; ULCI = 0.16; control condition: b = .01; SE = .02; LLCI = −0.05; ULCI = 0.08). For an overview see .

Table 1. Mediated analysis explaining conceptual persuasion knowledge and brand evaluation.

Table 2. Mediated analysis explaining conceptual persuasion knowledge and brand evaluation.

Discussion

Spoof placements are employed to reference existing, popular brands (Sutherland et al. Citation2011), as a humorous technique (Watercutter Citation2014), or as part of a marketing campaign (Yeshin Citation1998). In any case, spoof placements might be an interesting gateway for companies to awaken brand associations to their existing brand but still avoid regulations that are targeted and brand placements. Our study indicates for the first time how viewers treat spoof placement. Our results point to two main conclusions: First, we see that spoof placements elicit the same amount of conceptual persuasion knowledge as a condition showing no brand references. Therefore, spoof placements are not understood as a persuasive attempt to the extent of a real brand presentation and might not be processed as critically as real brand placements (e.g. van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2015). In a way, viewers are thus correctly judging the presented material. However, the example of Roc Donald’s above has also illustrated that spoof placements in fact are sometimes part of a marketing campaign (Yeshin Citation1998), and should consequently be characterized as such by the audience. Our results furthermore show that the control condition, showing a generic product description, and the spoof condition elicit similar levels of conceptual persuasion knowledge. Thus, our participants seem to have characterized the control condition as an advertising message at the same level as they did spoof placements. Both conditions significantly score below the real brand condition in the conceptual persuasion knowledge measure. However, this result indicates that both the generic product description and the spoof elicit some kind of understanding that a persuasive intent is imminent.

Second, we see that spoof placements can affect brand outcomes for the referenced brand. In particular, we observed that spoof placements create free-recall indications for the real brand they are referencing in over 50% of the viewers’ responses. Instead of rendering the name of the spoof brand, the spoof placement actually serves as a prime for the real brand’s name (Balasubramanian, Karrh, and Patwardhan Citation2006).

Regarding brand evaluations, we did not observe any direct or indirect effects for the brand Nintendo. Hence, we did not find that a brand reference directly increased the brand evaluation compared to a control group. This might, however, be attributed to the rather high evaluation of the brand Nintendo that was already apparent in the control condition (M = 4.47; SD = 1.03, measured on a 6-point scale). It is therefore possible that we hit a ceiling effect in the brand’s evaluation. The logic of spoof placements is built on the premises that the brand is already well known and popular (Naderer, Matthes, and Spielvogel Citation2019), so it hard to figure out whether a less popular brand would have performed differently.

In addition, we found no effect of the activation of conceptual persuasion knowledge and brand evaluation. Raising persuasion knowledge through real brand presentations does not mean the presented brand is assessed more negatively (Avramova, De Pelsmacker, and Dens Citation2018; Wei, Fischer, and Main Citation2008). Thus, while the real brand placement was recognized as advertising on a conceptual level, this did not lead to a decrease in the brand evaluation. This might be connected to the popularity of the integrated brand. Matthes and Naderer (Citation2016) suggest a possible positive reminder effect: The awareness of the presence of a brand the viewer likes might, following Matthes and Naderer’s reasoning, increase the viewers’ brand evaluation of said brand.

Future research and limitations

We would suggest that additionally including a measure of affective persuasion knowledge or affective reactance could be an interesting avenue for future research on spoofs (for examples of affective measures, see Avramova, De Pelsmacker, and Dens Citation2018; Boerman, Van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2014; van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2016). Particularly in view of the fact that spoofs are often parodies and are used in humorous ways, it would be interesting to investigate the level of affective reaction or the entertainment value of these placements to gain better insights into the processing of spoof presentations (Strick et al. Citation2012). Examining affective reactions would also help to better understand whether the results with regard to conceptual persuasion knowledge depend on the humorous processing of spoofs.

In addition to lacking affective measures as potential mediators, our study faces four main limitations. First, we only tested spoof effects for one type of brand or product category, one type of series genre, and one type of placement presentation. As we employed a brand or product category that is used for entertainment purposes and is not a necessity product, it would be interesting to replicate our study for other brands and product categories as well (Kamleitner and Jyote Citation2013). In addition, the humorous context of the series is a factor that might have translated on to the brand evaluation (Sutherland et al. Citation2011). This could indicate an affective priming effect (Zajonc Citation1980) that led to an increase of the brand evaluation in all three conditions. It would be of interest to evaluate spoof effects for other types of genres. Nevertheless, it must be mentioned that spoof placements are typically a tool that can be found in entertaining genres such as comedies (Naderer, Matthes, and Spielvogel Citation2019). This makes it difficult to disentangle the humorous context and mimicry effect a spoof placement. It might be valuable to find a spoof example in a series that is not associated with humor. In addition, from extant research, we know that different types of placement integrations perform differently with regard to their persuasive potential. Studies indicate that prominent placements differ from subtle placements in eliciting memory and brand evaluation effects, but this still depends on factors like plot integration, product type, the character the product placement is connected to, and of course, viewers’ preconditions (e.g. Dens et al. Citation2012; Kamleitner and Jyote Citation2013; Russell, Stern & Stern Citation2006; Verhellen, Dens, and De Pelsmacker Citation2013, Citation2016). Therefore, future research should dive deeper into these context factors in order to examine how spoof placements perform in comparison with real brands. In particular, eye-tracking appears to be a fruitful, yet neglected method for these questions (King et al., Citation2019)

Second, our examples in the beginning highlighted spoof placements that are also very relevant for content targeted at children. Our study, however, was conducted with an adult sample. As existing literature on embedded advertising indicates the difficulties of children and adolescents in grasping the persuasive intent of these advertising techniques (Buijzen, van Reijmersdal, and Owen Citation2010; Nairn and Fine Citation2008), it is particularly important to examine how children might react to spoof placements. We consequently encourage replicating our spoof placement study with a sample of children or adolescents.

Third, as outlined above, our results on persuasion knowledge indicate that even in the control condition, where we just presented a generic product description as a placeholder for the brand label, levels of persuasion knowledge were relatively high (M = 3.92; SD = 1.00; measured on a 6-point scale). It would be interesting to see if a control condition without any product presentation (generic or brand-specific) might have performed differently. With the present study, we wanted to present a design that was as internally valid as possible; therefore, we opted for the presented option of a generic product description. However, future research should include a control group with a clip from the same series or movie but without any kind of product. Still, building on other studies investigating persuasion knowledge and embedded advertising messages, we often find rather high levels of persuasion knowledge even in control conditions where no placements are visible (e.g. see Matthes and Naderer Citation2016). This indicates that even if no brands are shown in a control group, participants seem to report being aware of brands and sponsorship by default, just in case they might have missed a brand presentation. More research is needed to examine this premise, as it affects the question of what a threshold for activated persuasion knowledge might actually be.

Lastly, research should include additional measures when examining spoof effects. In the present study, we were not able to assess behavioral outcomes. However, it would be very relevant to examine whether spoof placements affect consumers in their actual brand choices (e.g. Auty and Lewis Citation2004). For future research, we furthermore suggest considering the long-term effect of spoof placements on explicit memory of the brand as an avenue worth exploring, as explicit memory traces might connect to lasting brand outcomes. Likewise, future research should measure brand familiarity, ideally, two or three weeks prior to the experiment in order to prevent priming effects.

Conclusion

We conclude that spoof placements have the potential to elicit awareness for the referenced real brand. However, they do not activate viewers’ conceptual persuasion knowledge to the same extent as a real brand placement does. From an advertiser’s point of view, planning a spoof campaign (Yeshin Citation1998) might be a successful way to create brand awareness and circumvent high levels of persuasion knowledge. However, from a normative perspective, such a reasoning seems highly questionable. As spoof placements are not explicitly prohibited or regulated, they might act as a loophole to place brands in content that restricts the use of brand placements (e.g. news programs or children’s programs). We thus recommend policy makers to carefully consider the role of spoof brands in the regulation of embedded brand presentations, particularly with respect to content targeted at children (Spielvogel, Naderer, and Matthes Citation2020).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Brigitte Naderer

Brigitte Naderer (PhD, University of Vienna) is a post-doctoral researcher at the Department of Media and Communication at the LMU Munich, Munich, Germany. Her research focuses on persuasive communication, media literacy, and effects of media use on children's and adolescents'well-being.

Jörg Matthes

Jörg Matthes (PhD, University of Zurich) is full professor of advertising research at the University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria. His research interests include advertising effects, public opinion for-mation, and empirical methods.

Simone Bintinger

Simone Bintinger (MA, University of Vienna) was a master student at the University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria. Her master thesis dealt with advertising effects of product placements.

References

- Auty, S., and C. Lewis. 2004. Exploring children's choice: The reminder effect of product placement. Psychology and Marketing 21, no. 9: 697–713.

- Audiovisual Media Services Directive (AVMSD). 2018. Directive 2018/1808 of the European Parliament and of the Council https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2018/1808/oj (Accessed 26 March 2020).

- Avramova, Y. R., P. De Pelsmacker, and N. Dens. 2018. How reading in a foreign versus native language moderates the impact of repetition-induced Brand placement prominence on placement responses. Journal of Brand Management 25, no. 6: 500–18.

- Balachander, S., and S. Ghose. 2003. Reciprocal spillover effects: A strategic benefit of Brand extensions. Journal of Marketing 67, no. 1: 4–13.

- Balasubramanian, S. K., J. A. Karrh, and H. Patwardhan. 2006. Audience response to Brand placements. An integrative framework and future research agenda. Journal of Advertising 35, no. 3: 115–41.

- Bhatnagar, N., L. Aksoy, and S. A. Malkoc. 2003. Embedding brands within media content: The impact of message, media, and consumer characteristics on placement efficacy. In The psychology of entertainment media, ed. L. J. Shrum, 110–127. Mahwah, New Jersey: Erlbaum Psych Press.

- Beaufort, M. 2019. How candy placements in films influence children’s selection behavior in real-life shopping scenarios–an Austrian experimental field study. Journal of Children and Media 13, no. 1: 53–72.

- Boerman, S. C., E. A. Van Reijmersdal, and P. C. Neijens. 2014. Effects of sponsorship disclosure timing on the processing of sponsored content: A study on the effectiveness of European disclosure regulations. Psychology & Marketing 31, no.3: 214–24. doi:10.1002/mar.20688.

- Boerman, S. C., E. A. van Reijmersdal, and P. C. Neijens. 2012. Sponsorship disclosure: Effects of duration on persuasion knowledge and Brand responses. Journal of Communication 62, no. 6: 1047–64.

- Buijzen, M., E. A. van Reijmersdal, and L. Owen. 2010. Introducing the PCMC model: An investigative framework for young people’s processing of commercialized media content. Communication Theory 20, no. 4: 427–50.

- Carpenter, S. 2018. Ten steps in scale development and reporting: A guide for researchers. Communication Methods and Measures 12, no.1: 25–44. doi:10.1080/19312458.2017.1396583.

- De Houwer, J., S. Thomas, and F. Baeyens. 2001. Associative learning of likes and dislikes: A review of 25 years of research on human EC. Psychological Bulletin 127, no. 6: 853–69.

- Dens, N., P. De Pelsmacker, M. Wouters, and N. Purnawirawan. 2012. Do you like what you recognize? Journal of Advertising 41, no. 3: 35–54.

- Evans, N. J., J. Phua, J. Lim, and H. Jun. 2017. Disclosing instagram influencer advertising: The effects of disclosure language on advertising recognition, attitudes, and behavioral intent. Journal of Interactive Advertising 17, no. 2: 138–49. no:

- Friestad, M., and P. Wright. 1994. The persuasion knowledge model: How people cope with persuasion attempts. Journal of Consumer Research 21, no. 1: 1–31.

- Gupta, P. B., and K. R. Lord. 1998. Product placement in movies: The effect of prominence and mode on audience recall. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 20, no. 1: 47–59.

- Ham, C., M. R. Nelson, and S. Das. 2015. How to measure persuasion knowledge. International Journal of Advertising 34, no. 1: 17–53. no:

- Hayes, A. F. 2018. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Hudson, S., D. Hudson, and J. Peloza. 2008. Meet the parents: A parents’ perspective on product placement in children’s films. Journal of Business Ethics 80, no. 2: 289–304.

- Hwang, Y., and S. H. Jeong. 2016. This is a sponsored blog post, but all opinions are my own’: The effects of sponsorship disclosure on responses to sponsored blog posts. Computers in Human Behavior 62: 528–35.

- Kamleitner, B., and A. K. Jyote. 2013. How using versus showing interaction between characters and products boosts product placement effectiveness. International Journal of Advertising 32, no. 4: 633–53.

- King, A. J., N. Bol, R. G. Cummins, and K. K. John. 2019. Improving visual behavior research in communication science: An overview, review, and reporting recommendations for using eye-tracking methods. Communication Methods and Measures 13, no.3: 149–77. doi:10.1080/19312458.2018.1558194.

- Knoll, J., H. Schramm, C. Schallhorn, and S. Wynistorf. 2015. Good guy vs. bad guy: The influence of parasocial interactions with media characters on Brand placement effects. International Journal of Advertising 34, no. 5: 720–43.

- Kroeber-Riel, W. 1984. Emotional product differentiation by classical conditioning (with consequences for the low-involvement hierarchy). In Advances in consumer research, ed. T. C. Kinnear, 538–543. Ann Arbor, MI: Association for Consumer Research.

- Liljander, V., J. Gummerus, and M. Söderlund. 2015. Young consumers’ responses to suspected covert and overt blog marketing. Internet Research 25, no. 4: 610–32.

- Matthes, J., and B. Naderer. 2016. Product placement disclosures: Exploring the moderating effect of placement frequency on Brand responses via persuasion knowledge. International Journal of Advertising 35, no. 2: 185–99.

- Matthes, J., C. Schemer, and W. Wirth. 2007. More than meets the eye. Investigating the hidden impact of Brand placements in television magazines. International Journal of Advertising 26, no. 4: 477–503.

- Matthes, J., W. Wirth, C. Schemer, and N. Pachoud. 2012. Tiptoe or tackle? the role of product placement prominence and program involvement for the mere exposure effect. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 33, no. 2: 129–45.

- Mittal, B. 1994. Public assessment of TV advertising: Faint praise and harsh criticism. Journal of Advertising Research 34, no. 1: 35–54.

- Moriarty, E. S., and S. Everett. 1994. Commercial breaks: A viewing behavior study. Journalism Quarterly 71, no. 2: 346–55.

- Muzellec, L., T. Lynn, and M. Lambkin. 2012. Branding in fictional and virtual environments: Introducing a new conceptual domain and research agenda. European Journal of Marketing 46, no. 6: 811–26.

- Naderer, B., J. Matthes, and I. Spielvogel. 2019. How brands appear in children's movies. A systematic content analysis of the past 25 years. International Journal of Advertising 38, no. 2: 237–57.

- Naderer, B., J. Matthes, and P. Zeller. 2018b. Placing snacks in children's movies: Cognitive, evaluative, and conative effects of product placements with character product interaction. International Journal of Advertising 37, no. 6: 852–70.

- Naderer, B., J. Matthes, F. Marquart, and M. Mayrhofer. 2018a. Children's attitudinal and behavioral reactions to product placements: Investigating the role of placement frequency, placement integration, and parental mediation. International Journal of Advertising 37, no. 2: 236–55.

- Nairn, A., and C. Fine. 2008. Who's messing with my mind? The implications of dual-process models for the ethics of advertising to children. International Journal of Advertising 27, no. 3: 447–70.

- Russell, C. A. 2002. Investigating the effectiveness of product placements in television shows: The role of modality and plot connection congruence on Brand memory and attitude. Journal of Consumer Research 29, no. 3: 306–18.

- Russell, C. A., B. B. Stern, and B. B. Stern. 2006. Consumers, characters, and products: A balance model of sitcom product placement effects. Journal of Advertising 35, no. 1: 7–21.

- Schemer, C., J. Matthes, W. Wirth, and S. Textor. 2008. Does “passing the courvoisier” always pay off? positive and negative evaluative conditioning effects of Brand placements. Psychology & Marketing 25, no. 10: 923–43.

- Spielvogel, I., Naderer, B., & Matthes, J. (2020). Disclosing product placement in audiovisual media services: a practical and scientific perspective on the implementation of disclosures across the European Union. International Journal of Advertising, 1–21. doi:10.1080/02650487.2020.1781478

- Strick, M., R. W. Holland, R. B. van Baaren, and A. Van Knippenberg. 2012. Those who laugh are defenseless: How humor breaks resistance to influence. Journal of Experimental Psychology Applied 18, no. 2: 213–23.

- Sutherland, L. A., T. MacKenzie, L. A. Purvis, and M. Dalton. 2011. Prevalence of food and beverage brands in movies: 1996–2005. Pediatrics 125, no. 3: 468–74.

- Sweldens, S., S. M. J. Van Osselaer, and C. Janiszewski. 2010. Evaluative conditioning procedures and the resilience of conditioned Brand attitudes. Journal of Consumer Research 37, no. 3: 473–89.

- van Reijmersdal, E. A. 2009. Brand placement prominence: Good for memory! bad for attitudes?. Journal of Advertising Research 49, no. 2: 151–3.

- van Reijmersdal, E. A., N. Lammers, E. Rozendaal, and M. Buijzen. 2015. Disclosing the persuasive nature of advergames: Moderation effects of mood on Brand responses via persuasion knowledge. International Journal of Advertising 34, no. 1: 70–84.

- van Reijmersdal, A. E., M. L. Fransen, G. van Noort, S. J. Opree, L. Vandeberg, S. Reusch, F. van Liesehout, and S. C. Boerman. 2016. Effects of disclosing sponsored content in blogs: How the use of resistance strategies mediates effects on persuasion. The American Behavioral Scientist 60, no. 12: 1458–74.

- Verhellen, Y., N. Dens, and P. De Pelsmacker. 2013. Consumer responses to brands placed in youtube movies: The effect of prominence and celebrity endorser expertise. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research 14, no. 4: 287–303.

- Verhellen, Y., Dens, N., and P. De Pelsmacker. 2016. Do I know you? how Brand familiarity and perceived fit affect consumers’ attitudes towards brands placed in movies. Marketing Letters 27, no. 3: 461–71.

- Watercutter, A. 2014. The 10 best apple gags from futurama and the simpsons. https://www.wired.com/2014/02/simpsons-futurama-apple-gags/

- Wei, M. L., E. Fischer, and K. J. Main. 2008. An examination of the effects of activating persuasion knowledge on consumer response to brands engaging in covert marketing. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 27, no. 1: 34–44.

- Wright, P., M. Friestad, and D. M. Boush. 2005. The development of marketplace persuasion knowledge in children, adolescents, and young adults. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 24, no. 2: 222–33.

- Yang, M., and D. R. Roskos-Ewoldsen. 2007. The effectiveness of brand placements in the movies: Levels of placements, explicit and implicit memory, and Brand-choice behavior. Journal of Communication 57, no. 3: 469–89.

- Yeshin, T. 1998. Integrated marketing communications. Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford.

- Zajonc, R. B. 1968. Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 9, no. 2, Pt.2: 1–27.

- Zajonc, R. B. 1980. Feeling and thinking: Preferences need no inferences. American Psychologist 35, no. 2: 151–75.