Abstract

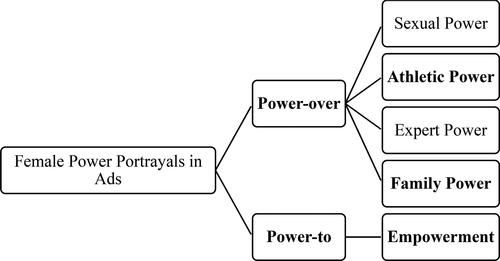

Although stereotypical female portrayals are still common in advertisements, in recent years it appears there has been a move toward portraying women in powerful positions in ads. This research investigates the recent trend in advertising that portrays women in positions of power and offers a typology of female power dimensions in ads. Building on previous literature on social power, feminine power, and current trends in advertising, a typology for female power is proposed and verified using two studies. In the first study, data from a pile sort of current print ads is collected and analyzed by cluster analysis and multidimensional scaling. In the second study, semi-structured interviews are employed to verify the proposed typology. Results verified that receivers perceive female power in advertisements in the following power dimensions: sexual power, expert power, family power, and empowerment (including athletic power).

Introduction

Advertising is thought to reflect current trends in culture while informing individuals about brands, products, services, and ideas (Pollay Citation1986). Thus, the manner in which females are portrayed in advertisements is important since it both reflects and indicates the expected roles of females in society.

Women have assumed increasingly powerful roles in society over the last 50 years. For example, in the twenty-first century, women fill jobs as police officers, lawyers, elected officials, and CEOs (Tolentino Citation2015). Although there are still differences in occupational roles and gender equity between men and women in the United States, there is evidence that suggests the country is moving toward a more gender-balanced power distribution. Thus, it would seem that advertising in today’s world should be reflective of this trend. Yet, some argue that women are still typically portrayed in ads in stereotypical fashions such as being housewives or secretaries (Lindner Citation2004). In fact, several recent studies contend that ad portrayals of women have not substantially changed over the past several decades (Knoll, Eisend, and Steinhagen Citation2011; Taylor, Miyazaki, and Mogensen Citation2013). Others, however, believe that there is some evidence that female ad portrayals may be evolving and are reflective of the trends noted above. For example, Varghese and Kumar (Citation2020) note an increase in advertising messages that display women’s talents and include pro-women messages. The authors concluded that various factors, such as activism and regulatory efforts, have led to more characteristic representations of women in ads (Varghese and Kumar Citation2020). Similarly, Windels et al. (Citation2020) studied ads containing femvertising-based messages (those that strive to empower women via pro-female messages) via content analysis and interviews and concluded that the ad environment is changing in that different elements of females are now being featured. Tsai, Shata, and Tian (Citation2021) conducted a content analysis of current print advertising and their results showed that female empowerment advertising is mostly focused on female consumers and it is portrayed through female models’ agentic power. Such conclusions are consistent with views of other researchers who note that the number of ads that feature females exercising power has been increasing in recent years (Gill Citation2008; Halliwell, Malson, and Tischner Citation2011). Given that there is some disagreement regarding the nature of female role portrayals in current ads and that role portrayal differences might (or might not) be based on female power, there is a need for researchers to investigate the power dimensions of female portrayals in today’s ad environment (cf. Hearn and Hein Citation2015).

Moreover, it is important to see how evolving ad portrayals of women are perceived by consumers. If ads are more likely to feature powerful portrayals of women, it is important to determine if portrayals are consistent with the perceptions of ad receivers. It is our contention that studies investigating the power portrayals of females in ads across a broadly-based myriad of recent publications could assist in shining a brighter light on society’s current views of women.

Accordingly, the primary objective of the present research is to investigate the portrayals of females in power in ads as they are perceived by the ad receivers. In doing so, the current research also presents a typology of the dimensions of female power portrayals in ads. The current study will hopefully help researchers better understand the bases of these portrayals in a more detailed and nuanced manner. Importantly, it represents a departure from previous studies that have defined power from a masculine point of view, and offers a definition of power that comes from a female perspective (Yoder and Kahn Citation1992).

Research in the past decade that studied gender portrayals in advertisements

Portrayals of women in advertising have been studied by researchers for some time (Grau and Zotos Citation2016). Much of this work has focused on the stereotypical portrayals of women in ads and suggests that females have been shown as being incompetent and/or insecure. Moreover, it emphasizes women’s roles as wives, mothers, lovers, homemakers, and sexual or decorative objects. One particularly important paper, Eisend (Citation2010), performed a meta-analysis of 64 research articles on gender stereotypes on TV and radio ads from 1986 to 2007 and suggested that stereotypical portrayals of women still exist, specifically in regard to their occupational status (e.g. engineer vs. homemaker).

Previous research on femvertising

In the past few years, research has begun investigating ‘femvertising’ (Champlin et al. Citation2019; Åkestam, Rosengren, and Dahlen Citation2017). Femvertising refers to advertising that challenges the stereotypical portrayal of women in ads by showing them in empowering positions (Åkestam, Rosengren, and Dahlen Citation2017). Examples of femvertising can be seen in Dove’s ad campaign in 2006 which was called Evolution (Åkestam, Rosengren, and Dahlen Citation2017). On its website, Dove describes this campaign as focusing on the encouragement of positive body images for women by revealing the truth about media and the distorted ideals of beauty. Other companies have looked at empowerment from angles other than beauty, such as athletic power (Klenkel Citation2019). For example, Ram trucks created the ‘Courage is Already Inside’ commercial which portrays women swimming, surfboarding, horseback riding, and challenging the overall societal expectations of female roles. Femvertising has been considered as one of the ad appeals that can be a successful strategy to target female customers (Åkestam, Rosengren, and Dahlen Citation2017).

Previous research showed that employing female empowerment in ads leads to less resistance toward the message contained within the ad and more positive attitudes toward the ad itself among female audiences (Åkestam, Rosengren, and Dahlen Citation2017). Others contend that femvertising can lead to a higher positive brand opinion, a stronger purchase intention, and greater emotional connection to the brand (Drake Citation2017). Based on their study, Abitbol and Sternadori (Citation2018) contend that there should be a fit between women-empowerment and consumers’ perception of the company for femvertising to be successful. Champlin et al. (Citation2019) extended the brand-cause-fit literature in the context of femvertising by studying the messaging strategies that are used by companies that have high vs. low brand-cause fit. These results indicate companies (such as Unilever) with high brand-cause fit (such as Dove) focus on excessive feminine traits, fixing issues of women (such as distorted body image), hardships of being a female, and starting a conversation about gender equality, whereas companies (such as Anheuser-Busch InBev) with low brand-cause fit (such as Bud Light) emphasize challenging stereotypes, low feminine attributes, the fact that men and women can do the same activities and having men as allies in this movement (Champlin et al. Citation2019).

Power and women

There is a recent trend in advertising in which ads portray women in non-traditional roles (Grau and Zotos Citation2016). Women have recently been portrayed as doctors, professors, athletes, business owners and other roles that were previously associated with men. In these ads, women are shown as having control over their own decisions and as being able to change other people’s behaviours and thoughts. Which are all examples of women portraying a different dimension of power. Research in the recent years looked into femvertising using different definitions including but not limited to a type of social movement marketing (Abitbol and Sternadori 2020), ads with pro-women messages (Windels et al. Citation2020), and ads that show women empowerment (Åkestam, Rosengren, and Dahlen Citation2017). However, a thorough investigation of how female power is demonstrated in ads and perceived by receivers has yet to be published.

Social power is defined as the ability to modify and control others’ states by providing rewards or administering punishments (Keltner, Gruenfeld, and Anderson Citation2003). Power can have different consequences for the power holder and the people around them. For example, individuals with greater levels of power have been shown to be more optimistic in risky situations (Anderson and Galinsky Citation2016). When an individual is perceived to have power, they are thought to be able to more readily persuade the audience to change existing views (Briñol et al. Citation2017).

Indeed, recent portrayals of females in ads show them as exercising social power. For example, a print ad for Reliant Medical Group portrays a female doctor who is a paediatrician, with her patients likely to follow her advice because of her expertise in the field. This female doctor in the ad appears to have power because of her knowledge and status.

Many ads studied in the context of femvertising show women in charge of their own thoughts and behaviours and able to lift themselves up. For example, one commercial by Lane Bryant (‘#ThisBody is Made to Shine’) shows women reading hateful comments about their bodies posted on social media, while being confident and uplifting.

Specifically, the feminist literature has categorized female power into two groups— ‘power-over’ and ‘power-to’ (Yoder and Kahn Citation1992). Power-over suggests that an individual has control and power over another person, a group of people, or an environment. Power-to, on the other hand, deals with the control one has over their own behaviours, feelings, and thoughts. Examples of power-to are self-control, will-power, and personal empowerment (Yoder and Kahn Citation1992). Importantly, women have been shown to believe the real source of power for them is power-to as opposed to power-over (Miller and Cummins Citation1992). That is, women tend to believe that society’s perspective of power differs from their own perspective. When women were asked to define power from society’s perspective they gave definitions consistent with power-over, but when they were asked to define power from their own point of view they defined power as personal empowerment (power-to) (Miller and Cummins Citation1992).

It is important to understand the difference in definitions of power and empowerment. In the previous literature, definitions of power mostly focus on ‘power-over’ or having capacity over others. However, in the feminine literature, empowerment or ‘power-to’ is considered as an important type of power. The perspective in this research sheds light on female portrayals in ads by offering clarifications about power, empowerment, and femvertising.

Borrowing from previous literature in both social and feminine power, this research defines female power as the ability to change the thoughts and behaviours of self and others. To better understand the dimensions of female power, the present paper will discuss studies that investigated female power as portrayed in advertising.

Lazar (Citation2006) investigated displays of feminine power as shown in advertisements, specifically focusing on post-feminist depictions. Lazar’s (Citation2006) study focused on ‘beauty ads’ promoting products that would help females be more attractive. Although they could be labelled as objectification, these ads attempt to show females enjoying their own beauty and influencing others by being attractive. This trend is in line with post-feminism thinking which supports sexually subjective women—women who take control over their own sexuality. Results suggest feminine power can be classified into four categories: (1) empowered—ads that attempt to promote products by making a female consumer appear to be more beautiful, which results in more power, (2) knowledge as power—ads with emphasis on the power of education of female models, (3) agentive power—ads that show women exercising freedom of choice in their life decisions, and (4) sexual power—ads in which women are shown to use their sexual potential to control their environment.

Gill (Citation2008) also studied power portrayals of females in advertising. She categorized female power dimensions in ads as being sexual, agentive, or vengeful. These categories are similar to those used by Lazar (Citation2006). The present research is based on these dimensions, and includes sexual, agentive, and vengeful power. Such an approach is consistent with Eisend (Citation2019), who believes that there is a dearth of research that investigates sexuality as a source of power for women. Moreover, it is consistent with post-feminism research that centred on ads suggesting sexual power is important in this context. To differentiate between sexual power and sexual objectification, one should keep in mind that sexual power is about sexual agency, which is defined as a ‘woman’s ability to act on her behalf sexually, express her needs and desires, and advocate for herself’. (Seabrook et al. Citation2017; p.241). For example, one of Levi’s ad portrays female sexual agency by featuring an illustration of a young woman wearing a crop top shirt and jeans and staring at the camera. The slogan reads: ‘Who do you want to unbutton?’ and the response is written in red font: ‘The boy who makes my morning latte’. This is an example of portraying a female who is making her own sexual decisions. In contrast, many ads show women in a sexually objectified manner. One example, an ad by BMW for used cars, shows a woman’s face and bare shoulders looking into the camera. The slogan reads: ‘You know you are not the first, but do you really care?’ This ad, comparing the young woman to a used car, is a clear illustration of objectification.

Sexual power depicts women as exercising their sexuality and attractiveness, moving from sexual objectification to sexual subjectification, and having power over (heterosexual) men because they are ‘alluring’ and ‘seductive’. This category is similar to sexual power discussed by Lazar (Citation2006) and Gill (Citation2008).

In prior years, women were not typically portrayed as being physically active in ads (Eisend Citation2019). A past print ad for Del Monte Foods, for example, featured a woman holding a bottle of ketchup with a tagline ‘you mean a woman can open it?’ implying women are not physically strong enough to open a regular bottle cap. Recent trends in ads challenge this premise by showing women as professional sports figures and as being physically strong (e.g. see Serena Williams in recent Nike ads). However, there still exists a difference between the portrayals of female versus male athletes. For example, female athletes are featured mainly in women’s magazines (Grau, Roselli, and Taylor Citation2007). A comparison of female models in fitness versus other types of magazines showed there is more emphasis on the performance in the former and on appearance in the latter (Wasylkiw et al. Citation2009). One study looked at specific messages by companies such as Nike towards women. A 1995 Nike ad has the tagline ‘If you let me play’, with the sentence going on to say, ‘I will be 60% less likely to get breast cancer’ (Arend Citation2015). However, a Nike ad in 2010 features fit women and professional female athletes and has a tagline stating, ‘I’m making myself’ (Arend Citation2015). This difference between sports ads for women in 1995 and 2010 serves as an example that women have become more physically powerful, and that it is being reflected in ad portrayals.

Physical power is offered as one of the dimensions of female power in ads. It is important to note that this dimension has not been identified in previous research as a source of power for females in ads.

Prior research suggests that an ad spokesperson’s expertise positively influences their persuasiveness (e.g. DeBono and Harnish Citation1988). This expertise can be a valuable source of power that is only in possession of a limited number of people. Power is a result of asymmetric control over valuable resources which leads to a personal or group ability to influence others (Rucker, Hu, and Galinsky Citation2014). Previous research showed that portraying an expert in an ad can increase the credibility of its message and decrease the risk perception for consumers (Biswas, Biswas, and Das Citation2006). Traditional gender portrayals in ads used to show men as a source of information and knowledge, however this trend has changed in recent years. For example, a recent print ad for the University of Miami features female professors with the tagline ‘We’re there for you’. Such an ad implies these women have authority because of their knowledge, expertise, and status. This portrayal of power is consistent with knowledge power as described by Lazar (Citation2006).

Expert/knowledge power depicts women as both resourceful and knowledgeable. They can guide others or influence others’ decisions because they have the required expertise.

As suggested above, femvertising, in part, deals with female empowerment messages in ads (Åkestam, Rosengren, and Dahlen Citation2017). As noted, empowerment differs from definitions of power in the previous literature. Power which is a result of asymmetric control over resources is about influencing other people, whereas empowerment (power-to) deals with the ability to change self (Yoder and Kahn Citation1992). Therefore, the current research adds another dimension of power; one called ‘personal empowerment’ that aligns closely to the aforementioned notion of ‘power-to’.

Personal empowerment depicts women as having the power to control one’s behaviour, thoughts, and feelings and perform self-enhancement activities. This type of power also resonates with agentive power mentioned by Lazar (Citation2006) and Gill (Citation2008). It is found in portrayals of women who have control over their choices. Such women in commercials are shown as self-determined and ‘calling the shots’.

In sum, four dimensions of female power were ascertained from reviewing previous literature in related areas and by investigating the contents of current ads. The four dimensions include sexual power, physical/athletic power, expert/knowledge power, and personal empowerment. Additionally, we conducted a pre-test to identify other potential female power dimensions that we had not yet identified. Specifically, the pre-test helped us to identify family power as another dimension (see below).

To investigate female power sources in advertisements and determine if they align with existing knowledge structures of consumers, our empirical efforts sought to shed light on the following question: What are the underlying dimensions of female power in print advertisements as perceived by consumers?

Methods

A sequence of studies was conducted to develop and verify a typology for female power in advertisements. First, a pre-test was done to verify the dimensions that were derived from previous research and new trends in advertising. In the next study, pile sort, cluster analysis, and multidimensional scaling were used to confirm the resulted typology. Finally, a series of interviews were conducted to qualitatively analyze and verify the proposed typography.

Pre-test

As noted above, we uncovered several female power dimensions by studying the literature and reviewing current advertisements. While we sought to empirically verify the existence of these dimensions, we felt it necessary to conduct a pilot study to make certain that other dimensions existed (note that an additional female power dimension, family power, emerged as a result of the pilot study).

A pre-test using 16 ads high in dimensions of power (4 athletic power, 2 expert power, 3 sexual power, 3 empowerment power, and 4 neutral/powerless) were administered to 28 students in a marketing class at a Midwestern university. This study was conducted in Qualtrics. Participants were informed of the definitions of power and the bases of power and then asked to sort ads into similar groups based on their power-dimension portrayals. Subjects were also asked to list their thoughts about each category and power dimension.

Results from these pre-tests showed participants perceived the four power dimensions proposed. However, as suggested above, one additional power dimension emerged from the results of this pre-test. The stimuli included some ads that were neutral in terms of female power, showing women in family settings or performing household chores. Participants put these ads into a category called ‘family power’ or ‘mom power’. Previous research regarding the power structure in families had defined men and women’s power in a domestic setting as the power to make a final decision for the family (Safilios-Rothschild Citation1970). Bowerman and Elder (Citation1964) categorized family power into two groups: (1) marital role (power in wife-husband relationships) and (2) parental role (power in parent-child relationships). Females can gain power in families through factors such as income, education, and occupational status (Heer Citation1963). They can also provide an organized home, good food, support, affection, encouragement, and praise (Safilios-Rothschild Citation1970). These are the major bases of power for females in family settings. It is worth mentioning that not every woman portrayed in a family setting in an ad is considered powerful. Several previous studies noted the abundance of females shown as passive homemakers or in traditional roles as wives or mothers where their in-home-setting presence is emphasized (Furnham and Paltzer Citation2010; Kacen and Nelson Citation2002). However, participants assigned family power to some of the women in the ads. For example, there is an ad which shows a family consisting of a husband and wife and their four children posing for a photo. One of the respondents mentioned: ‘This seems like all the kids kinda have these nice fancy clothes…The husband is just wearing an average jacket …so it seems like the woman has control over family, something as family power’. The same ad was described by another participant as ‘This is definitely family power because it’s a woman standing there with her entire family and she has a child in her arms… so she is kinda taking care of the family, specifically the child she is holding… all the children are under 18 and she is going to have to be making decisions for them’. It seems even if the mother is not portrayed as one of the breadwinners in the family here, her power in relation to making decisions for others is being recognized and acknowledged.

We define family power as the capability of a female in a domestic setting to provide support, encouragement, financial resources, and an organized home to other family members. This power can be specifically divided into two categories—marital role and parental role.

The emerging typology that was derived after the pre-test is presented in 1.

Main study 1

Design

Pile-sort tasking has previously been used in research to aid in understanding dimensions or patterns of different concepts. For example, Leonard and Ashley (Citation2012) have used pile sorts of print ads to understand the underlying dimensions of violence in ads. In pile sorting, subjects are asked to sort stimuli items (such as pictures, cards, statements, etc.) into piles based on similarity of items, leading to describe different dimensions. In such approaches, participants are asked to combine like items into a specific pile (Weller and Romney Citation1988). The present study utilizes an unconstrained pile sort where the number of piles is not specified; participants can have as few or as many piles as they choose (Collins and Dressler Citation2008). Although female power dimensions were explained to participants, they were not constrained in choosing the categories and could either choose from the proposed typology or create their own category. This method yields a symmetric matrix wherein each cell shows the subjective judgment of similarity or difference between items in the stimuli for each subject. Individual matrices are aggregated, and the resultant matrix is analyzed using multi-dimensional scaling.

Stimuli

Print ads chosen from magazines based on their audience comprised the stimuli for this study. Ads were selected from a variety of magazines, including those intended for female, male, and general audiences. Magazines were randomly selected from issues published in 2016, by using a random number generator.

Following the methods of Havlena and Holbrook (Citation1986), a first set of judges (8 individuals) picked the preliminary set of stimuli, and a second set of judges (7 individuals) rated and confirmed the stimuli. The first set of judges picked the ads with female power. If the second set of judges agreed with the first set, then those ads were included in the final stimuli. More details about this procedure are offered next. Judges were students at a major Midwestern university.

Eight magazines were given to each of the first set of judges. Each judge was told to select ads that depicted females in a powerful position and identify these ads with sticky notes on the page that contains the ads. These judges were instructed to consider only full-page print ads. After the first set of judges marked the print ads in the magazines, the second set of judges were asked to rate the preselected ads from the same magazines (those with sticky notes). The second set of judges were given eight magazines as well. They were asked to rate the ads with the sticky notes based on the level of the power of the female model and write their rating on the post-it notes. Ratings were from 1 = least to 5 = most female power.

Both sets of judges were provided with the authors’ definition of power. They were not asked about dimensions of power but were asked whether they see the female portrayed in the ad as powerful. Since individuals have different definitions of power in their minds (Keltner, Gruenfeld, and Anderson Citation2003), the objective of providing a generic definition of power was to ensure that all participants had a more unified understanding of the concept they were rating. Ads which were selected by the first group and rated high in female power by the second group of judges were selected for the final stimuli set that consisted of 50 ads, 40 of them (Leonard and Ashley Citation2012) showing different female power portrayals with at least five ads each per dimension, and 10 power-neutral ads (selected by the first group but rated low in power by the second group).

For general audience magazines, Time and People were selected based on their high circulation level according to Pew Research Center (Citation2015). The following female magazines were chosen based on their type of content and level of circulation: Better Homes and Gardens, Woman’s Day, and Good Housekeeping (women’s interests), Cosmopolitan (women’s relationships, fashion, and careers), Women’s Health (health, nutrition, and fitness), Glamour, Vogue, Style Watch, and In Style (fashion). The following male magazines were chosen based on their type of content and level of circulation: Men’s Fitness and Men’s Health (health, nutrition, and fitness), Esquire and Maxim (Men’s interests), GQ—Gentlemen’s Quarterly (men’s fashion, style, and culture). Name and publication dates of magazines are offered in . The objective here was to include various types of magazines with broad audiences.

Table 1. Name and publications date of magazines.

As a control, ten ads showing females in neutral power positions were included in the stimuli sample. Ads that included female portrayals that are neither powerful nor objectifying were considered neutral. The reason for including neutral female power ads was to investigate whether there are other potential power dimensions not recognized in the proposed theory. The 50 ads chosen for the final stimuli are available in . To reduce the confounding effects of brand names, brand names were covered in the final stimuli.

Table 2. Final stimuli, pile of 50 print ads.

Sample and participants

Previous research studies have used a maximum-variation sample (Marshall Citation1996) to represent a broad range of participants. This sampling strategy attempts to include subjects from a diverse demographic range to represent different, diverse viewpoints. For this study, being inclusive of different knowledge structures was important, so a maximum-variation sample (Marshall Citation1996) was used. In this sample, we focused on maximizing diversity in terms of age, gender, and education level since these demographic criteria are shown to influence individuals’ perception of female portrayals (Wise, King, and Merenski Citation1974). Twenty-five participants were recruited through flyers and snowball sampling. The number of participants used in our study is in close alignment with other research that used a similar methodology (Leonard and Ashley Citation2012). Twenty-five volunteers were chosen to participate in the study based on age, gender, and education level. To ensure the sample was demographically diverse, participants were asked three criteria prior to deciding their eligibility. The sample includes participants from both genders at different ages and different education levels. Each subject was compensated with a $20 Amazon or Target gift card for his or her participation. The number of print ads used in the study was also consistent with previous advertising studies that used similar methods (Leonard and Ashley Citation2012). shows the characteristics of the subjects in the sample.

Table 3. Characteristics of subjects in the sample (study 1).

Procedure

The pile-sort procedure was employed at the individual level. That is, pile sorts were performed on 50 ads by each individual participant. Participants were instructed on examples of the different dimensions of female power. However, they were asked to think of their own categorizations of female power when reviewing the ads. The reason that examples of definitions were offered was to provide more clarity on what is considered as power in the literature. They were asked to sort the print ads based on the female power dimensions they saw in a particular ad. Participants were instructed to place ads similar in dimensions of power portrayals into the same category but were not constrained in terms of categories. Ads were presented to participants in a random order and in print format. Participants were told to make a label for the categories they created. These labels were used later to interpret the resulting dimensions. There was no other conversation between participants and researcher through pile sort. Participants were not allowed to assign more than one category to each ad but they were asked to choose a category that was more salient to them. Pile sorts lasted between 10 to 26 minutes for these participants. Each pile sort was recorded after the participant left the interview room.

Analysis

Based on prior research that gathered pile-sort data, the present study used two different methods to analyze the data, multidimensional scaling and hierarchical cluster analysis (Leonard and Ashley Citation2012).

Multidimensional scaling

Multidimensional scaling (MDS) was previously used to determine the underlying dimensions and patterns in data sets based on measures of similarity (Burton and Romney Citation1975). In this method, researchers use different numbers of dimensions to achieve the best goodness of fit in the model and data, and at the same time reduce complexity. Increasing the number of dimensions may lead to better goodness of fit, but will likely increase the complexity of the model (Burton and Romney Citation1975). First, for each participant, a matrix of dissimilarity between ads was produced based on pile sorts. Previous research suggested using a dissimilarity matrix because of technical reasons (Giguère Citation2006). Columns and rows for each matrix consisted of names of ads. If two ads are placed into the same group, the cell corresponding to these two ads will show the value 0, otherwise the cell will have the value 1. An aggregated matrix was created by summing the 25 matrices for all participants. Off-diagonal numbers show the number of times ads were not included in the same category. The numbers on the diagonal were all 0 (Leonard and Ashley Citation2012).

MDS created dimension solutions based on the dissimilarity matrix. ALSCAL (SPSS 24) was used to perform the MDS. Solutions ranged from two to six dimensions. Stress level is used in MDS as a goodness of fit measure. As suggested by previous research, 0.05 ≤ STRESS≤.1 is a good fit (Giguère Citation2006). The solutions calculated by MDS provided the following stress levels (and R2) for two through six dimensions, respectively: .20 (.79), .12(.88), .08(.92), .06(.95), .05(.96). At four dimensions, the stress level falls between .05 and .1; in addition, the four-dimensional solution explained .92 of variance in the data. As a result, the four-dimensional configuration was chosen because of the good stress level and interpretability. Next, each dimension is interpreted and explained, based on the ads rated highly for this dimension.

Dimensions resulting from MDS

The analysis of the labels given to pile sorts and the nature of the ad used in understanding the dimensions are provided. Ads with higher weights on dimension one were categorized and labelled as demonstrating sexual power. For example, ad34 shows a woman seductively gazing at the camera and the caption reads, ‘just the right amount of wrong’. Another example is ad35, which shows a half-naked woman on sheets in a bed with a big smile. These ads and several others are rated highly in dimension one and negatively in the other three dimensions.

Dimension two encompassed ads that featured portrayals of females as professional and expert. For example, ad17 showing a female physician in a lab coat is associated highly positive with this dimension. Another example is ad23 which shows a man and woman standing strongly together as news anchors. Part of the captions reads, ‘They tell us what’s going to happen in Washington before Washington even knows’. This dimension deals with expert power that shows women as professionals or having certain expertise.

Dimension three encompassed ads which show females as being able to change their own thoughts and behaviours. For example, ad12 shows two women telling each other their life stories and the caption reads, ‘These women embody the compassion and courage inherent in all women, and the difference all women can and do-make every day. We believe their causes are a cause for celebration’. Another example is ad15, which features a woman with a curvy body shape. She is wearing a suit and laughing. This woman appears to be embracing her body shape and going forward in her career. These ads are labelled as empowering by participants. Interestingly, ads that show athletic power and physical strength also received high positive ratings for this dimension.

Dimension four features ads in which females are exercising family power. For example, ad2 shows a woman and her young daughter, both smiling, and the caption reads, ‘unique as we are’. Another example, ad5, shows an adult woman with a young girl leaning on her, both looking at the sky. All these ads were piled into the family power category by participants.

The four-dimensional result appears to be consistent with our proposed typology, suggesting the underlying dimensions of female power portrayals in ads include expert, sexual, and family power dimensions. Based on the data generated in the present study, it appears that the dimensions of empowerment and athletic power were not seen as being independent dimensions.

Hierarchical cluster analysis

Both hierarchical clustering and MDS can be used to understand patterns and similarities in data sets (Burton and Romney Citation1975). Hierarchical clustering (Garson Citation2014) is used to discover homogenous groups inside a dataset.

In this study, clusters show groups of ads that portray similar types of female power. Like previous research (Leonard and Ashley Citation2012), hierarchical cluster analysis was completed using the coordinates from MDS. The goal was to investigate ads that would form a homogenous subset following the four dimensions. Hierarchical cluster analysis in SPSS utilized Ward’s algorithm. Hierarchical cluster analysis for classifying the estimated sorting task results was completed to form potential grouping structures. This procedure was achieved for 2–10 clusters to identify the best cluster solution. Another method to choose the correct number of clusters is to calculate the Euclidean distance from each ad’s cluster centre for all nine solutions. Intragroup error is the average distance from the centroid (Leonard and Ashley Citation2012). The average distance from the centroid was 1.5 for two clusters, 1.28 for three clusters, 1.05 for four clusters, and .96 for five clusters. Since the improvement for moving from four to five clusters is less than the improvement for moving from three to four clusters, the best cluster solution is four clusters (Punj and Stewart Citation1983). Results for the present study follow.

Clusters resulting from cluster analysis

Cluster one: Family power. This cluster contains eight ads that show females in the family power dimension. All ads portray a mother (female parental figure) in a family, except for three ads. These three ads are also related to the family role of females. For example, ad1 shows a middle-aged woman of colour in sweatpants sitting on an old truck. The caption reads, ‘After retiring, Charlotte Tidwell put her pension–and her heart–into nourishing her community’. Nourishing in this caption seems the key word, which relates this image to a family power cluster.

Cluster two: Expert power. The 12 ads contained here suggest that the cluster be labelled as expert power or professional power. These ads portray women in one of the following contexts: wearing business suits in a happy, confident posture, portrayed as an authority in a high-tech office, wearing a lab coat as a physician or pharmacist, shown as a teacher in a classroom, or as exemplars of successful women in the real world. This cluster appears to demonstrate expert power.

Cluster three: This cluster includes 13 ads that demonstrate females exercising sexual power. All ads show attractive women in seductive clothing, postures, or associated with suggestive taglines. For example, ad32 shows a woman’s face with unrealistic green eyes, green nails, staring at the camera and touching her lips. The captions reads, ‘unleash your inner wildcat’. Alternatively, ad45 shows a woman standing in a denim jacket without a top underneath. The caption reads, ‘I can fear nothing’. These ads portray confident, strong women exercising sexual power.

Cluster four centres on empowerment and athletic power. Empowerment associates with having the capability to change self/others’ behaviour or thoughts. The 17 ads in this cluster include both empowerment and athletic power. However, as perceived by participants, athletic power can be recognized as having power over their own body. It also can be understood as being in control of one’s health, diet, and exercise routine to achieve an athletic objective. Therefore, it is reasonable that athletic power ads have been categorized in the same cluster as empowerment ads. Ads in this cluster either portrayed physically fit, strong women in sports (ad28, ad29, ad30, ad25, ad31, ad50), or women who can overcome pain and illness because they are in control (ad13, ad40), or ads that show females working with feminine-specific challenges, such as periods or pregnancy by portraying physically fit women (ad39, ad14), or just showing empowered women able and willing to change for better or embracing their present.

Main study 2

Study 1 focused on ad categorization and the analyzing of categories without delving into the thought processes of the participants. Moreover, in Study 1 while participants were prompted to create their own categories, information was provided to them regarding the categories. To provide additional support for the existence of the categories, an additional study was conducted where participants were asked to label the ads based on the female power dimension offering any pre-existing categories. Such a study was thought to reduce the danger of the research method having an influence on participants’ responses. Furthermore, the study assessed the thought processes of participants regarding their views of female power dimensions in ads.

Sample and participants

For the second study, in order to follow the premise of including different knowledge structures, maximum-variation sample (Marshall Citation1996) is used. Eighteen participants were recruited through flyers and snowball sampling. Participants were recruited until theoretical saturation emerged and no new significant pieces of data are uncovered through the interviews (Barry and Phillips Citation2016). The number of participants is consistent with other research that uses similar methodology (Hill and Johnson Citation2004). Similar to the first study, to ensure a diverse sample, participants were asked three criteria prior to deciding their eligibility. Each respondent was compensated with a $20 Amazon gift card for his or her participation. shows the characteristics of participants in the sample.

Table 4. Characteristics of subjects in the sample (study 2).

Stimuli

Since this study is conducted to validate the results from the first study, stimuli ads were picked from the set in study 1. All of the 50 ads were rated by three judges to ensure they were relevant in today’s advertising context. Based on judges’ evaluations’ twenty ads were chosen for the final stimuli. The number of ads are fewer than the first study since participants are asked to review each ad and offer their thoughts about female power in the ad in this study. The number of the ads is in close proximity to studies that employed similar research methods (cf. Barry and Phillips Citation2016).

Procedure

Interviews were done in an online platform (Zoom) to follow social distancing orders in place due to the COVID19 pandemic. Two links are created for this study. First, a survey is designed on Qualtrics which presents the twenty ads. In the survey, participants would review the ads and drag them into categories based on the type of the female power they see in the ad. Second, another website is created that shows the ad’s full size, as ad details might not show properly on Qualtrics. The interviewer started by introducing themselves and offering a short description of the study. They then shared the two links, including the Qualtrics survey and the website with ads in large size, and read the following script to the interviewee:

Power is defined as the ability to change self or others’ behaviours and thoughts. Do you perceive women in the below advertisements exercising power?

There are different types of power and they may be perceived differently by different people. Please categorize the ads that demonstrate the same types of female power into the same category. But note, there may be multiple types of power which suggest that you may have multiple piles. You can drag and drop the pictures into the categories in the survey link. The number of listed categories is arbitrary, so you may leave some of them empty. Please put the ones with no power under the ‘no power’ category. While categorizing ads, please describe the reason that you chose a certain category for that ad’.

All the interviews were recorded and transcribed. The transcriptions are analyzed to verify the dimensions that were proposed and confirmed in the first study. Interviews lasted between 16 to 51 minutes for these participants.

Analysis

Studying and analyzing the interview transcripts offered verification for the typography that was proposed before, in addition to some interesting insights for future research. In order to verify the typology, conceptual ordering (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998) was used to organize the data. Conceptual ordering deals with an ‘organization of the data into discrete categories according to their proprieties and dimensions’ (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998, p.19). Employing conceptual ordering helped organize the interview data into female power dimensions and find potentially new dimensions worth exploring. The responses were categorized based on the type of female power that participants considered for the ads. Specifically, systematic comparison (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998) was used to compare incidents in the data to the dimensions from the proposed typology. The study authors repeatedly reviewed the notes, made comparisons and drew conclusions. Following are examples that show support for the dimensions in the female power typology:

Family power

This dimension was mentioned several times by participants in different forms as a type of female power. Participants mentioned how a female can be shown as powerful by being reliable, nurturing, raising the next generation and teaching them the right values, and by just being a mother figure. Specifically, first, it was mentioned there is power in being caring and showing support for others. For example, R4 (male, 35–44 years) mentioned:

‘I feel that the ads for this category represent that the person in the ad is a caring, nurturing individual who either cares about her family or the environment or what people get to consume. So that’s the caring power in my perspective’.

Second, family power was illustrated in female’s role as a mother who interacts with others in the family. For example, R8 (female, 45–54) states:

‘It shows the power of motherhood. That’s what I assume of this. Right. So the power of motherhood, power of family life, how to raise the next generation, how to teach them values and beauty of the world and ethics and give them opportunities to build their skills and educate them properly. I guess that’s what family life for me stands for’.

Other participants expressed how they see a mother as a strong female portrayal R15 (female, 18–24 years) suggested:

‘I’ll make a new category. This is a different type of strength. I think it is a strength like motherly strength, if that makes sense…’ or R10 (female, 25–34 years):

‘I felt like she was powerful because I was seeing her as the little girl’s mother. I think mothers are strong’.

Overall, interview results confirmed the proposition that family power is perceived by audiences as one dimension of female power that is employed in advertising. It is worth noting that based on the literature there are two different power roles for females in the family: parental and marital (Bowerman and Elder Citation1964). However, the results from our interviews were focused on the parental role, in part due to the limited number of the ads and female portrayals in families in the stimuli set.

Expert power

Knowledge, professional appearance, education, and expertise were recognized as a source of power for female models in ads by participants. This perception might be the result of female’s physical surrounding in the ad. For example, R15 (female, 18–24 years) mentioned ‘this is the power of knowledge and like intelligence…she’s around a computer screen with a bunch of work and everything. She looks intelligent’. Or participants viewed the model’s profession as powerful since they appeared to be experts in their field, as was mentioned by R9 (female, 25–34): ‘I believe this is a pharmacist here. So I believe she’s educated. She has knowledge of the product she is trying to advertise or sell’. And R12 (male, 45–54 years): ‘This ad is showing the strength of knowledge of a female that has been to many years of school, has much knowledge, and is confident with that knowledge that she’s gained’.

As proposed in the typography, being perceived as expert or professional in a field gives the female model a power over receivers since they will be more willing to follow the suggestions of the expert figure. This female power dimension was supported by several examples from interviews.

Sexual power

Participants repeatedly created a female power category for attractiveness and sexuality in the interviews. For example, participant number 1 developed a category which they called ‘sensual/sexual power’ and in this category they put two ads. One of those ads is a woman that appears without clothes, in bed sheets and smiling at the camera, looking content and confident. The other ad shows a woman in a suit and a hat and the copy reads ‘just the right amount of wrong’. Other interviewees also categorized similar ads in groups they labelled as sexual power, sex appeal power, or attractiveness. As R2 (female, 18–24 years) indicated:

‘…they’re trying to attract, I would say males and also females, because there’s a lot of females that want to have a body like hers’. This participant acknowledges that being attractive give the female model a power to persuade others. She might have power over men since she is sexually attractive, but also she may have power over women since they might want to look like her and they may like to follow her.

Athletic/physical power

This power dimension was also repeatedly recognized by interviewees. Being sporty, outdoorsy, athletic, and in control of their body are some of the ways participants described this power dimension. As R5 (male, 35–44 years) mentioned: ‘this would be a strong woman because based on what we can see in the pictures, they are strong. They are doing exercises. They look to be on top of their lives and I want my daughter to be like them in strength’. It is important to note that this participant perceives the female model in the ad so powerful that they want their daughter to follow the model’s example.

Another participant described a category she created with two ads: ‘I just notice that they’re both doing physical stuff. It’s that they’re clearly good at what they’re doing. So there’s power in that. And it’s that they’re both sporty. It’s that she’s clearly surfing and she’s clearly fit’. It is evident that participants view being athletic and having physical strength as a source of power for the female models in ads.

Empowerment

Empowerment is considered a dimension of feminine power that resonates with ‘power-to’, meaning to have the power to improve self or being in control of one’s own decisions. This dimension was brought up by several participants in different ways. Participants referred to this power dimension as self-power, self-empowerment, convenience of freedom, internal power, self-confidence, and comfortable with who they are. This type of power seems to be perceived as how women feel about themselves and their capabilities. For example, R1 (male, 25–34 years) stated: ‘This is more of a self-power, one of internal perception of self. Power is not conveyed to anyone outside, I feel like’.

Being confident and active in making decisions are additional other ways empowerment can be portrayed, as R1 (male, 25–34 years) said: ‘Now that does convey that sort of power in terms of being able to be more outgoing, perhaps to take a risk. It’s more risky. It’s more of being able to be confident to move out of your comfort zone. So I think that is power in that sense. So it’s self-power in that sense’. Another example is for women to be able to improve themselves, as R2 (female, 18–24 years) mentioned: ‘because if I see a magazine and I see these images and these statements… women empowerment, to become… you know, better, to better themselves’.

Empowerment is also about having the power to be comfortable with who they are as women, as R11 (female, 55–64 years) said: ‘She is being more herself; being more comfortable with herself, and that is exuding a certain level of power and confidence too’.

It is important to note several participants suggested the existence of other dimensions of power. For example, one potential dimension appears to deal with age and its associated wisdom in older women. Others noted older women in the ads and suggested that they had power due to their age. Another possible dimension noted by study participants was the authenticity of female models in ads. Those women who appeared to be ‘real’ were considered to have power by a small subset of participants. Authenticity has been associated with the success of ads that promote positive roles for women (Grau and Zotos Citation2016). This notion was echoed by some of our interview participants. For example, one of our interviewees described a female model in the ad as follows: ‘She’s trying to come across as strong and powerful. But to me, it’s not maybe her authentic self. She’s putting on more of a play for the camera’.

Another important finding which emerged from interviews is that several ads contained portrayals that featured multiple dimensions of female power in one ad. For example, interviews suggested that ads could portray a woman as a CEO (expert/knowledge power) with a different body type than stereotypical models (empowerment). Our results showed that viewers could identify different female power dimensions in an ad depending on their own experience and background.

In sum, results from the interviews confirmed empowerment as one of the female power dimensions that was proposed in the typology. Although this type of power doesn’t portray exercising power over other people since it shows control over one’s thoughts and decisions, it is still perceived as power by receivers.

Discussion

While it seems that women have more powerful roles in society, the extent to which this notion has been reflected in advertising remains uncertain. Recent #MeToo, #MoreWomen, and #Timesup campaigns have attempted to persuade women to speak out against abuse and encourage them to be more involved in politics. Accordingly, the present research investigates the portrayals of females in ads to better understand the underlying dimensions of female power. Building upon theories of social power, feminism, and recent trends in advertising, a framework for female power is proposed and empirically verified. The framework generally categorized female power in two main groups — ‘power-over’ and ‘power-to’. Results from our study appear to be supportive of this aspect. Specifically, they indicate that consumers differentiate between these power dimensions and see them as different bases of female power. These include expert, sexual, family, and empowerment (including athletic power).

Grau and Zotos (Citation2016), in their review of recent research on gender roles, concluded that there has been a focus on research about ‘empowered women’. They also called these types of messages ‘Pro-women’ or ‘femvertising’. Grau and Zotos called for more research on femvertising and how this type of advertising can be more effective. The typology of female power portrayals and interview results that showcase receivers’ perceptions of these portrayals presented herein aim to help to understand this kind of advertising in more detail. Grau and Zotos (Citation2016) found that although women are still depicted in inferior ways compared to their abilities, there is a new trend in advertising that shows more positive female role portrayals. Results from the current research dig deeper into this notion and explained receivers’ perceptions of portrayals that demonstrate women in powerful positions.

Tsai, Shata, and Tian (Citation2021) identified a few sources of empowerment and social power and conducted a content analysis based on the identified sources. However, their review failed to differentiate between empowerment and power. Such a differentiation was noted in our data. Additionally, Tsai, Shata, and Tian (Citation2021) did not empirically verify the existence of power/empowerment dimensions prior to preforming the content analysis. The present study takes a more foundational approach in that it developed a conceptual framework to serve as a guide in its data-collection efforts.

Recently, a few research studies investigated femvertising- ads that promote female empowerment-content and impact on the society (Champlin et al. Citation2019; Åkestam, Rosengren, and Dahlen Citation2017). The present study attempted to clarify the differences between femvertising and portraying female power in ads. Our results suggested that receivers have the ability to differentiate between empowerment (power-to) and power (power-over). While previous research on femvertising focuses on empowerment, the current research sheds light on other ways that women have been portrayed exercising power in ads, such as being an expert, an athlete, or an influential parent.

Additional analysis suggested that consumers can distinguish between different dimensions of female power portrayals in ads; these differences confirm our proposed typology. A somewhat unexpected finding from the results indicated participants considered athletic power a subcategory of power-to (empowerment). It appears that athletic power is perceived as the person being in control of one’s mind and body to build a physically strong self, rather than having the capacity to change others’ behaviours.

Eisend (Citation2019) called for research that studies new gender-role attributes in advertisements. These attributes are traditionally associated with one gender, but recently they have been applied to both men and women in ads. The present study partially answered this by investigating how consumers perceive power as an attribute that can be associated with women in ads.

Thus, the current research takes a first step in better understanding female power in advertising. While most prior studies investigated power from a masculine point of view, this research defined female power from a different perspective. Such a perspective yielded power categories consistent with the perceptions of consumers. Importantly, this research also offered a fairly exhaustive typology of dimensions that underlie female power. Future research could study the extent to which these dimensions are featured in ads (via content analyses) and could determine the extent to which they are likely to influence differing market segments across multiple product categories. For example, ads that feature female sexual power are likely to lead to different levels of acceptance as compared to those which feature expert power, especially when the target markets differ in age. It is possible, for example, that young adult females would be more receptive of ads featuring sexual-power portrayals than would older females. Moreover, it is important to understand how these different dimensions might interact with each other. Future research could also investigate how consumers would perceive the simultaneous use of two or more power dimensions in an ad. For example, ad may show a mother mentoring her children while, at the same time, portraying her an expert-required position, such as a physician. In addition, a segmentation study might investigate how different segments of consumers (gender, age, education) respond to different portrayals of female power in ads. Our findings suggest there might be other sources of female power in ads such as female models’ age and authenticity. Thus, future research needs to look into factors that can improve ad authenticity, specifically in the female power context. We also felt that the existence of additional dimensions should be investigated in future research studies.

Practical implications

The typology for female power portrayals that is developed and empirically verified in this research can serve as a guide to advertising practitioners. Based on the results of the present studies, advertisers now have a reference to better understand the bases of female power dimensions and may be able to pick and choose the ones that will work best for their target market. Depending on the type of product or brand, one or more of the female power dimensions might be relevant to consumers. For example, an educational institution might want to try and choose expert power, whereas a fashion company might consider employing sexual power in their campaigns.

Liljedal, Berg, and Dahlen (Citation2020) showed that depicting women in job roles that are stereotypically associated with men may improve attitudes towards different advertising results such as attitudes toward the ad and the brand. In turn, advertisers should consider the positive effects of demonstrating women in powerful positions.

Another potentially important implication for practitioners deals with the authenticity of powerful female models they depict in their ads. Results of this research suggest that viewers differentiate between female models exercising a type of power versus simply appearing to promote a product or service. Advertising managers need to pay attention to authenticity of female portrayals.

Finally, advertisers could use more than one dimension of female power in their marketing activities depending on their desired message and target audience. Having female power typology in hand can guide advertisers in creating ad campaigns that include multiple female power dimensions. For example, they can decide which power dimensions can work best if employed together in a campaign depending on the brand and target audience.

Limitations

Future research might examine female portrayals in other media, such as online advertisements on Facebook and Instagram. Other media outlets might use different portrayals of female power compared to print ads in magazines. To have a better understanding of female power portrayals, it might be helpful to consider other sources of ads rather than magazines, and study other types of ads such as television commercials and digital ads. It has been proposed that digital marketing is the future. Since marketers can employ more novel ideas and reach more audiences in less time using digital marketing (Kannan Citation2017), it would be important to study digital ads for female power portrayals.

Magazines selected for this study were broad based; those chosen appealed to female audiences, male audiences, and/or the general population (per previous research – Kang Citation1997; Kacen and Nelson Citation2002; Lindner Citation2004). Although we tried to have many different types of magazines represented including fashion, style, culture, health, nutrition, careers, and general interest, there are magazine types that were not included in the stimulus set (e.g. automobile magazines). Such specialized magazines were not considered in the stimuli since it is shown there are fewer female portrayals in advertisements (Koernig and Granitz Citation2006). Yet, future research could study the portrayals of female power in male-targeted magazines.

Current research investigated the way consumers perceive female power portrayals in ads. Future research could investigate certain aspects of the ads that can impact female power perceptions. Female model image, copy, brand name, and product category might have different roles in how consumers perceive female power. Future research might investigate these factors and their interplay.

There have been numerous studies that investigated gender-role portrayals and there is a vast difference between different countries and cultures in female portrayals in advertising and audience perceptions of such portrayals (Furnham, Twiggy, and Tanidjojo Citation2000; Nassif and Gunter Citation2008). It is important to note that all of the ads in the stimuli were collected from magazines in the US and all participants in the different studies were recruited from the US. This limits the generalizability of our findings since the US is ranked highly in its masculinity (Hofstede Citation2001). Thus, when considering the results and implications of this study, one needs to bear in mind the cultural differences between the US and other countries.

In addition, important questions remain about how male power portrayals differ from females’ portrayals in ads. Future research may study male power portrayals and contrast them with the results of the present study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Melika Kordrostami

Melika Kordrostami (Ph.D., Iowa State University) is an Associate Professor of Marketing at California State University, San Bernardino. Her research projects deal with gender issues in marketing, branding, and cultural consumption. Her research has been published in different journals such as Journal of Marketing Management, Journal of Product & Brand Management and Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management.

Russell N. Laczniak

Russell N. Laczniak (Ph.D., University of Nebraska-Lincoln) is currently Emeritus Professor of Marketing in the Debbie and Jerry Ivy College of Business at Iowa State University. Dr. Laczniak formerly served as editor of the Journal of Advertising and as president and treasurer of the American Academy of Advertising. He received the Ivan L. Preston Award for his lifetime contribution to research from the American Academy of Advertising in 2014. Dr. Laczniak’s research deals with the interface of marketing communication and public policy/societal issues. His publications have appeared in the Journal of Consumer Psychology, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Journal of Advertising, Journal of Current Issues and Research in Advertising, Journal of Advertising Research, and others.

References

- Abitbol, A., and M. Sternadori. 2018. Championing women’s empowerment as a catalyst for purchase intentions: testing the mediating roles of OPRs and Brand loyalty in the context of femvertising. International Journal of Strategic Communication 13, no. 1: 22–41.

- Åkestam, N., S. Rosengren, and M. Dahlen. 2017. Advertising “like a girl”: toward a better understanding of “femvertising” and its effects. Psychology & Marketing 34, no. 8: 795–806.

- Anderson, C., and A.D. Galinsky. 2016. Power, optimism, and risk-taking. European Journal of Social Psychology 36, no. 4: 511–36.

- Arend, K. M. (2015). Female Athletes and Women’s Sports: A Textual Analysis of Nike’s Women-directed Advertisements (Doctoral dissertation, Bowling Green State University).

- Barry, B., and B.J. Phillips. 2016. The fashion engagement grid: understanding men’s responses to fashion advertising. International Journal of Advertising 35, no. 3: 438–64.

- Biswas, D., A. Biswas, and N. Das. 2006. The differential effects of celebrity and expert endorsements on consumer risk perceptions. The role of consumer knowledge, perceived congruency, and product technology orientation. Journal of Advertising 35, no. 2: 17–31.

- Bowerman, C. E., and G. H. Elder. Jr. 1964. Variations in adolescent perception of family power structure. American Sociological Review 29, no.4: 551–67.

- Briñol, P., R. E. Petty, G. R. Durso, and D. D. Rucker. 2017. Power and persuasion: processes by which perceived power can influence evaluative judgments. Review of General Psychology 21, no. 3: 223–41.

- Burton, M. L., and A. K. Romney. 1975. A multidimensional representation of role terms. American Ethnologist 2, no. 3: 397–407.

- Champlin, S., Y. Sterbenk, K. Windels, and M. Poteet. 2019. How Brand-cause fit shapes real world advertising messages: a qualitative exploration of ‘femvertising. International Journal of Advertising 38, no. 8: 1240–63.

- Collins, C. C., and W. W. Dressler. 2008. Cultural consensus and cultural diversity: a mixed methods investigation of human service providers’ models of domestic violence. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 2, no. 4: 362–87.

- DeBono, K. G., and R. J. Harnish. 1988. Source expertise, source attractiveness, and the processing of persuasive information: a functional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 55, no. 4: 541.

- Drake, V. E. 2017. The impact of female empowerment in advertising (femvertising). Journal of Research in Marketing 7, no. 3: 593–9.

- Eisend, M. 2010. A Meta-analysis of gender roles in advertising. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 38, no. 4: 418–40.

- Eisend, M. 2019. Gender roles. Journal of Advertising 48, no. 1: 72–80.

- Furnham, A., and S. Paltzer. 2010. The portrayal of men and women in television advertisements: an updated review of 30 studies published since 2000. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 51, no. 3: 216–36.

- Furnham, A., M. Twiggy, and L. Tanidjojo. 2000. An asian perspective on the portrayal of men and women in television advertisements: studies from Hong Kong and indonesian television. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 30, no. 11: 2341–64.

- Garson, G.D. 2014. Cluster Analysis. http://www.statisticalassociates.com/clusteranalysis.pdf

- Giguère, G. 2006. Collecting and analyzing data in multidimensional scaling experiments: a guide for psychologists using SPSS. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology 2, no. 1: 27–38.

- Gill, R. 2008. Empowerment/sexism: figuring female sexual agency in contemporary advertising. Feminism and Psychology 18, no. 1: 35–60.

- Grau, S. L., and Y. C. Zotos. 2016. Gender stereotypes in advertising: a review of current research. International Journal of Advertising 35, no. 5: 761–70.

- Grau, S. L., G. Roselli, and C. R. Taylor. 2007. Where’s tamika catchings? A content analysis of female athlete endorsers in magazine advertisements. Journal of Current Issues and Research in Advertising 29, no. 1: 55–65.

- Halliwell, E., H. Malson, and I. Tischner. 2011. Are contemporary media images which seem to display women as sexually empowered actually harmful to women? Psychology of Women Quarterly 35, no. 1: 38–45.

- Havlena, W. J., and M. B. Holbrook. 1986. The varieties of consumption experience: comparing two typologies of emotion in consumer behaviour. Journal of Consumer Research 13, no. 3: 394–404.

- Hearn, J., and W. Hein. 2015. Reframing gender and feminist knowledge construction in marketing and consumer research: missing feminisms and the case of men and masculinities. Journal of Marketing Management 31, no. 15–16: 1626–51.

- Heer, D. M. 1963. The measurement and bases of family power: an overview. Marriage and Family Living 25, no. 2: 133–9.

- Hill, R., and L.W. Johnson. 2004. Understanding creative service: a qualitative study of the advertising problem delineation, communication and response (APDCR) process. International Journal of Advertising 23, no. 3: 285–307.

- Hofstede, G. 2001. Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviours, institutions and organizations across nations. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Kacen, J., and M. Nelson. 2002. We’ve come a long way baby–or have we? Sexism in advertising revisited. In Proceedings of the 6th Conference on Gender, Marketing and Consumer Behaviour, 291–308.

- Kang, M. 1997. The portrayal of women’s images in magazine advertisements: Goffman’s gender analysis revisited. Sex Roles 37, no. 11–12: 979–96.

- Kannan, P. K. 2017. Digital marketing: a framework, review and research agenda. International Journal of Research in Marketing 34, no. 1: 22–45.

- Keltner, D., D. H. Gruenfeld, and C. Anderson. 2003. Power, approach, and inhibition. Psychological Review 110, no. 2: 265–84.

- Klenkel, M. 2019. Why The Rise of Femvertising is Good PR. PR News. Retrieved from: https://www.prnewsonline.com/prnewsblog/femvertising/

- Knoll, S., M. Eisend, and J. Steinhagen. 2011. Gender roles in advertising: measuring and comparing gender stereotyping on public and private TV channels in Germany. International Journal of Advertising 30, no. 5: 867–88.

- Koernig, S. K., and N. Granitz. 2006. Progressive yet traditional. Journal of Advertising 35, no. 2: 81–98.

- Lazar, M. M. 2006. Discover the power of femininity!” analyzing global “power femininity” in local advertising. Feminist Media Studies 6, no. 4: 505–17.

- Leonard, H. A., and C. Ashley. 2012. Exploring the underlying dimensions of violence in print advertisements. Journal of Advertising 41, no. 1: 77–90.

- Liljedal, K.T., H. Berg, and M. Dahlen. 2020. Effects of nonstereotyped occupational gender role portrayal in advertising: how showing women in Male-Stereotyped job roles sends positive signals about brands. Journal of Advertising Research 60, no. 2: 179–96.

- Lindner, K. 2004. Images of women in general interest and fashion magazine advertisements from 1955 to 2002. Sex Roles 51, no. 7–8: 409–21.

- Marshall, M. N. 1996. Sampling for qualitative research. Family Practice 13, no. 6: 522–6.

- Miller, C. L., and A. G. Cummins. 1992. An examination of women’s perspectives on power. Psychology of Women Quarterly 16, no. 4: 415–28.

- Nassif, A., and B. Gunter. 2008. Gender representation in television advertisements in britain and Saudi Arabia. Sex Roles 58, no. 11–12: 752–60.

- Pew Research Center. 2015. State of the News Media 2015. Retrieved from: http://www.journalism.org/2015/04/29/news-magazines-fact-sheet/

- Pollay, R. W. 1986. The distorted mirror: reflections on the unintended consequences of advertising. Journal of Marketing 50, no. 4: 18–36.

- Punj, G., and D. W. Stewart. 1983. Cluster analysis in marketing research: review and suggestions for application. Journal of Marketing Research 20, no. 134–48.

- Rucker, D. D., M. Hu, and A. D. Galinsky. 2014. The experience versus the expectations of power: a recipe for altering the effects of power on behaviour. Journal of Consumer Research 41, no. 2: 381–96.

- Safilios-Rothschild, C. 1970. The study of family power structure: a review 1960–1969. Journal of Marriage and Family 32, no. 4: 539–52.

- Seabrook, R. C., L. M. Ward, L. M. Cortina, S. Giaccardi, and J. R. Lippman. 2017. Girl power or powerless girl? Television, sexual scripts, and sexual agency in sexually active young women. Psychology of Women Quarterly 41, no. 2: 240–53.

- Strauss, A., and J. Corbin. 1998. Basics of qualitative research techniques (pp. 1–312). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Taylor, K.A., A.D. Miyazaki, and K.B. Mogensen. 2013. Sex, beauty, and youth: an analysis of advertising appeals targeting US women of different age groups. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 34, no. 2: 212–28.

- Tolentino, L. 2015. Women in Power. 4 Roles in Society that Show Women Can be as powerful as Men. Ms. JD. http://ms-jd.org/blog/article/women-in-power.-4-roles-in-society-that-show-women-can-be-as-powerful-as-me.

- Tsai, W. H. S., A. Shata, and S. Tian. 2021. En-gendering power and empowerment in advertising: a content analysis. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 42, no. 1: 19–33.

- Varghese, N., and N. Kumar. 2020. Feminism in advertising: irony or revolution? A critical review of femvertising. Feminist Media Studies 1–19. https://www.tandfonline.com/action/showCitFormats?doi=10.1080/14680777.2020.1825510

- Wasylkiw, L., A. A. Emms, R. E. Meuse, and K. F. Poirier. 2009. Are all models created equal? A content analysis of women in advertisements of fitness versus fashion magazines. Body Image 6, no. 2: 137–40.

- Weller, S.C., and A.K. Romney. 1988. Systematic data collection. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Windels, K., S. Champlin, S. Shelton, Y. Sterbenk, and M. Poteet. 2020. Selling feminism: how female empowerment campaigns employ postfeminist discourses. Journal of Advertising 49, no. 1: 18–33.

- Wise, G. L., A. L. King, and J. P. Merenski. 1974. Reactions to sexy ads vary with age. Journal of Advertising Research 14, no. 4: 11–6.

- Yoder, J. D., and A. S. Kahn. 1992. Toward a feminist understanding of women and power. Psychology of Women Quarterly 16, no. 4: 381–8.