Abstract

Consumers, employees and society at large seems to expect more and more that brands take a stand on societal issues. This notion is known as brand activism. This paper explores recent academic research on this issue, to provide guidance for brand managers and other marketers. The concept is defined and delineated, and the impact of brand activism on consumers, employees, investors and (last not but not least) the cause itself is discussed. The paper introduces the Aligned Activism Model, which outlines the key role of alignment between brand, issue, and consumers. This model provides actionable insights for marketers who seek to engage in brand activism. Suggestions for future research are provided for academics who seek to advance knowledge on brand activism.

Why brand activism?

In their 2022 global Trust barometer, Edelman signals a decline in trust in democracy and government, paired with a strong belief that business should do more to address societal problems. The report concludes that societal leadership has become a core function of business. Part of this role is that consumers and employees are expecting brands to take a stand on societal issues, a practice often referred to as brand activism. The present paper explores recent academic research on this topic, to provide guidance for brand managers and other marketers. After defining and delineating the concept, the impact of brand activism on consumers, employees, investors and (last not but not least) the cause itself is discussed. The final section introduces the Aligned Activism model, which outlines the key role of alignment between brand, issue, and consumers, and provides guidance for marketers who seek to engage in brand activism.

Brand activism has been defined as ‘the act of publicly taking a stand on divisive social or political issues by a brand or an individual associated with a brand’ (Mukherjee and Althuizen Citation2020, 773). There are two important elements in this definition. First, the emphasis on publicly – the brand is not working behind the scenes, ‘doing good while nobody is watching’. Brand activism means that the brand speaks up to make its opinion known to the world – using full-blown advertising campaigns, ad-hoc social media posts, PR-efforts, or a combination of those. Second, there is the focus on divisive social or political issues. This implies that there are proponents and opponents, which sets brand activism apart from corporate social responsibility (CSR), although it may be argued that it is perhaps more of a continuum than a dichotomy. Examples on the one end of the continuum include brands like Dove, Lululemon, and Gucci, advertizing their stance on the reversal of Roe v. Wade, a very divisive issue in contemporary American society. On the other end of the continuum, there are issues that more or less everybody agrees upon: it is hard to find a company that does not (claim to) reduce their environmental impact, for instance.

Hartmann, Marcos, and Apaolaza (Citation2023) recently called for more research on consumer responses to advertising that communicates brand stance taking on controversial social issues. I echo and extend this call, and would like to emphasize that there are two opposing mechanisms involved in this setting, which will both be addressed in this paper. On the one hand, there is the risk of misalignment: for any divisive issue, there is a percentage of the brand’s current and potential customers that will disagree with the brand’s stand. If the brand speaks out loud enough (and the issue is important enough), it runs the risk of losing those customers (Hydock, Paharia, and Blair Citation2020). On the other hand, divisiveness also has an upside: divisive issues are more identity-relevant and have greater signaling power. To put it differently: the more people disagree on a stance, the better it distinguishes between a desirable ingroup and an undesirable outgroup (Berger and Heath Citation2008).

The impact of brand activism on consumers

The impact of brand activism on consumer responses like buying intention and brand attitude has been examined in several studies. This response is largely determined by the extent to which the brand’s stance is aligned with the consumer’s opinion on the issue. All other things equal, consumers who agree with the brand will have a positive response to brand activism, while those who disagree with the brand will have a more negative response. Hydock, Paharia, and Blair (Citation2020) and Mukherjee and Althuizen (Citation2020) report experiments examining a wide range of countries (US, UK, France) and issues (including stances pro and contra topics like refugee rights, transgender bathrooms, abortion, gun control, LGBTQ rights and Brexit (for a UK sample). In these experiments, participants are presented with brand stances on social issues, communicated via ads, social media posts and press releases. The authors find no systematic differences between these different media, and show negative effects of brand activism on consumers who disagree with the brand, and positive effects for people who agree with the brand. Importantly, both authors find an asymmetry in these effects, such that the positive effects on people who agree are often weaker than the negative effects for people who disagree. A similar pattern was found by Jungblut and Johnen (Citation2022), who studied the effects of LGBTQ-focused advertising on consumer’s brand image. As noted by Hydock, Paharia, and Blair (Citation2020), this asymmetry is consistent with the negativity bias, which psychological research has found in many different settings (Baumeister et al. Citation2001). It is important to note, however, that this asymmetry may depend on several other factors, which are related to the underlying mechanism for the effects of brand activism on consumer responses. Existing literature suggests three possible mechanisms for these effects, that may operate in parallel: (1) brand identification, (2) emotional responses, and (3) consumer empowerment.

Brand identification

Consumers use brands to establish their identity and communicate it to others. Brand identification is the extent to which consumers see the brand as part of their selves, and experience cognitive and emotional connections with the brand (Escalas and Bettman Citation2003; Bernritter et al. Citation2017). Several studies support the role of brand identification as an underlying mechanism for brand activism effects (Hydock, Paharia, and Blair Citation2020; Mukherjee and Althuizen Citation2020). The role of brand identification may be even stronger when the brand becomes more closely associated with a particular issue. In this case, a social process occurs, where the brand is used to signal a certain (social) identity to others, and to express one’s group membership (or desired membership). In other words, when the brand becomes more closely related with an issue, consumers can use the brand to signal that they support this cause – think of Patagonia’s close association with nature and environment, which has turned the brand into symbol or badge for consumers who want to associate themselves with this cause and express this identity to others. As Berger and Heath (Citation2008) point out, this identity-expressive function is more important for high-involvement issues, such as issues that are identity-related to minority groups. Indeed, a recent study on Nike’s ad campaign supporting Colin Kaepernick found that evaluations of this campaign were especially positive among consumers who were highly involved with the advocated issue (Li, Kim, and Alharbi Citation2022).

Emotional responses

Garg and Saluja (Citation2022) found that consumers who agree with a brand’s stance feel happier with the brand, and are proud about ‘their’ brand’s engagement with the issue. The effects were reversed for consumers who disagreed with the issue. In a follow-up study, the authors found that these positive emotional responses were found only when the brand made an actual contribution to the issue. If the brand didn’t show actual involvement, and only paid ‘lip service’ to the issue, there was no significant response from people who agree with the brand. Consumers who disagreed with the brand’s stance always showed a negative response to brand activism, regardless of whether the brand made an actual contribution to the issue or not. In line with this finding, a study on consumer reactions to brand social media posts in support of Black Lives Matter showed that consumers were very critical of such responses, and demanded brands to take action on the issues involved (Yang, Chuenterawong, and Pugdeethosapol Citation2021).

Consumer empowerment

Hajdas and Kłeczek (Citation2021) proposed one more mechanism for brand activism effects. In a qualitative study, these authors explored the role of consumer empowerment. By taking a stance on a political issue, the brand provides consumers with an opportunity to actively engage with the issue – it enables them to ‘do something’. Brand activism provides consumers with a structural means of empowerment, especially when it enables them to support the organization or cause by financial or other means. In addition, it provides consumers with a sense of empowerment that boosts their self-esteem and gives them a sense of accomplishment. Kristofferson, White, and Peloza (Citation2014) found that such empowerment may have both positive and negative consequences: on the one hand, it may trigger a chain of commitment and consistency, as consumers feel the urge to act consistently with the commitment that they express by purchasing the product. On the other hand, consumers may feel that purchasing the activist brand (or perhaps even ‘liking’ or sharing the brand’s social media posts) relieves them from their responsibility to engage in further action, a phenomenon known as ‘slacktivism’.

The impact of brand activism on future and current employees

Research in related domains suggests that the impact of brand activism on current and future employees may be at least equal to its impact on consumers. In general, several advertising scholars have argued and shown that consumer advertising has a strong effect on current and future employees (e.g. Rosengren and Bondesson Citation2014). Schaefer, Terlutter, and Diehl (Citation2020) found that employee evaluations of their company’s CSR communications on social and environment-related issues have a significant impact on job satisfaction and organizational pride. To the best of my knowledge, there have not been any studies on the impact of activist advertising on employees. Some insights can be gathered however from studies that have examined current and future employees’ responses to CEO statements and other corporate messages.

The impact of brand activism on job seekers was studied for example by Roth et al. (Citation2022), in an experiment that presented participants with a corporate message that was either pro or contra gun control. Alignment between the organization’s stance and the participant’s opinion had a positive effect on the extent to which participants liked the organization and thought they would enjoy working for it. Appels (Citation2022) reports a set of four studies using more than 1100 actual job seekers from the US. His research shows that job seekers’ alignment with activist CEO statements leads to an increase in employer attractiveness and job pursuit intentions. Similar to research in the consumer domain, the negative effect of misalignment in these studies was stronger than the positive effect of alignment.

Perhaps even more than job seekers, brand activism influences current employees. A recent field study (Wowak, Busenbark, and Hambrick Citation2022) examined the behavior of employees of companies whose CEOs did or did not sign a highly publicized protest letter against the ‘bathroom bill’ in which the state of North Carolina rolled back a number of anti-discriminatory protections for the LGBTQ community. The results of this natural experiment showed that employees’ commitment to the organization was influenced significantly by the extent to which the CEOs actions were aligned with the political orientation of the employees. There was no evidence for negativity bias, perhaps because employees are much more personally involved with the opinion of the CEO than job seekers or consumers.

An interesting question here is whether it is good or bad that CEO activism deters nonaligned employees: on the one hand, an activist CEO might attract a team of employees that is more coherent and shares a strong common culture. On the other, it might be detrimental to the (political) diversity of the organization. In addition, although consumer research on brand activism found no substantial differences in responses to ads and CEO statements, it would be interesting to examine the extent to which this is also true for the effects of activism on current and future employees.

The impact of brand activism on investors

Two studies have investigated investor responses to brand activism. Bhagwat et al. (Citation2020) collected data on 293 events involving 149 US-based firms between January 2011 and October 2016, and examined the movement of stock prices after brand activism events like Twitter’s introduction of a special Black Lives Matter emoji, and JCPenney’s 2012 Mothers’ Day ad featuring two lesbian mothers. The study found that investors respond negatively to corporate activism, with activism leading to an average 0.4% drop in shareholder value. This effect was significantly stronger (more negative) when the company was perceived to have more conservative customers and employees (most of the activism was progressive), and when the event deviated more from government standpoints and policies.

Mkrtchyan, Sandvik, and Zhu (Citation2023) analyzed a more extensive set of 1402 events collected from January 2011 to December 2019, where S&P 500 firms and their CEOs communicated their opinions on socio-political issues. The data showed a rapid increase in the proportion of S&P 500 firms making such statements (from 1% in 2011 to 10% in 2016, and 38% in 2019). The most popular topics were LGBTQ equality, the environment, inclusion, and renewable energy. Contrary to Bhagwat and colleagues, this study found a significant positive market response to activism of 0.12-0.17%. Although the study focuses on CEO activism, additional analyses compared the effects of CEO statements to more general communications and advertisements by the firm. They found no differences between the two.

These two studies provide opposing insights on investor responses to brand activism: the first (Bhagwat et al. Citation2020) shows a significant negative effect, while the second (Mkrtchyan, Sandvik, and Zhu Citation2023) shows a significant positive effect. Some important differences between them should be noted. Number one, the first study is based on a much smaller sample of events than the second (293 vs 1402). As Mkrtchyan and colleagues point out, the number of activist events has increased dramatically over the years. In 2016 (the last year of data in Bhagwat et al.), 10% of CEOs engaged in activism. In 2019, this had increased to 38%. As a result, more than two-thirds of the data in the study of Mkrtchyan and colleagues was collected after 2016, suggesting that activism has become much more common.

Both studies provide insights on factors that moderate the effects of brand activism on investors, by conducting additional analyses examining the role of the extremity and intensity of the brand’s stance. Specifically, the studies found that investors respond less favorably when the stand that is taken is more extreme (Bhagwat et al. Citation2020), or when companies make statements that are more vivid and outspoken (Mkrtchyan, Sandvik, and Zhu Citation2023). Taken together, these results suggest that investors have become more favorable toward brand activism in recent years, but they remain wary of radical opinions.

The impact of brand activism on the issue

In advertising, our attention is almost automatically drawn to the impact of brand activism on consumers and brands. But what about the issue itself? Using data collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, Dastidar, Sunder, and Shah (Citation2023) examined the relationship between TV advertising related to COVID-19 (split into government/public advertising, and commercial brand advertising), and changes in social mobility data (using data that measured crowding/social distancing based on GPS localization data of cell phones). They found that brand’s COVID-19 advertising had a positive influence on social distancing behavior, when controlling for the effect of government policies (mask mandates, lockdowns). In contrast, government advertising had no effects on such behavior. Combined with restrictive policies, it even had a negative effect, suggesting that citizens reacted against government advice. Although this is just one particular case, these results suggest that brands can be effective advocates for social issues. One important caveat is the perceived motive for brand activism: Recent research by Ruttan and Nordgren (Citation2021) showed that companies’ instrumental use of social values (like diversity and environmentalism) in their advertising may decrease the extent to which these values are seen as sacred, which is paired with a lower willingness to donate to organizations promoting these values. More research is needed to establish the conditions under which such effects do or do not occur.

Eilert and Nappier Cherup (Citation2020) argue that there are three ways in which brands can help advance social causes: (1) raising awareness, (2) influencing attitudes, and (3) closing the intention-behavior gap. Raising issue awareness is a key element of making progress on social issues. Using their creative talents and their considerable reach, brands can be powerful agents in increasing awareness on social issues. In this way, brand can play an important role in remedying the shortage of knowledge among segments of the public that are difficult to reach by governments and NGOs. Once awareness is established, brands can play a role in influencing attitudes and closing the intention-behavior gap. Brands may achieve this by applying normative pressure or by facilitating desired behaviors. Normative pressure can be created by normalizing issues, for example by displaying a greater diversity of body shapes and sizes and genders in advertising. In other cases, it involves de-normalizing practices, for example by the removal of stereotypical depictions of race or gender on packaging or in stores (think for example of the redesign of Uncle Ben’s packaging). Finally, brands can facilitate change by providing consumers with access to alternatives, like vegan food options, or climate-friendly product variants.

The alignment activism model

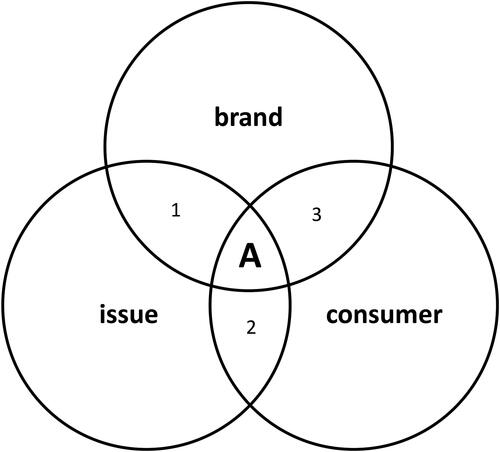

Managers who consider engaging in brand activism often raise the question of whether or not to speak out on a certain issue. The key issue here is whether the issue is aligned with the brand and its consumers. The same issue can be acceptable for brand X, but completely unacceptable for brand Y. Alignment can be approached from different angles, as shown in the figure below, which visualizes the Alignment Activism Model. This model proposes that brand and activism should be aligned on three dimensions. First, there is the internal dimension, which defines alignment as the degree to which the issue aligns with the brand’s ‘DNA’ or ‘best self’. Second, there is the external – consumer - perspective: consumer responses depend on the extent to which the brand’s stance is aligned with their own opinion. Third, there is the consumer’s perceptions of the brand’s activism: do consumers perceive that the activist message is aligned with the brand’s image, communication, and corporate practice? This latter dimension is often referred to as authenticity. Following these guidelines, responses to brand activism should be optimal in the A-spot, at the center of the model, which is found when brands engage in activism on an issue that is aligned with their purpose (or ‘best self’), that is aligned with the opinion and values of their (target) consumers, and that is communicated in a way that consumers perceive as authentic ().

Figure 1. The Aligned activism model.

1: Brand-issue alignment: the overlap between the brand’s “best self” and the issue.

2: Consumer-issue alignment: consumer attitude & involvement toward the issue.

3: Consumer Perceptions of the authenticity of the brand’s activism.

A: The A-Spot: a brand’s authentic activism regarding an issue that fits their “best self” and is aligned with the opinion of their (target) consumers.

Brand-issue alignment

Academic research on activism has been focused on the consumer and employee perspective, but has not examined brand-issue alignment from the perspective of the brand. I therefore rely on the big ideal model, developed by brand strategists at Ogilvy, as a starting point for discussing brand-issue alignment (Shaw and Mitchell Citation2011). The model defines a ‘big ideal’ as ‘the concise description of the ideal at the heart of a brand or a company identity - its deeply held conviction on how the world, or some particular part of it, should be’ (7). Shaw and Mitchell propose that the big ideal exists at the intersection of (1) the brand’s best self, and (2) a cultural tension. The ‘brand’s best self’ refers to the brand’s essence - the central element of the brand’s positioning (cf., Keller Citation2014). While the concept of ‘cultural tension’ is not explicitly defined by the authors, their examples indicate that it refers to social issues that evoke differences in opinion, and that there is a substantial number of people who find the issue important, perhaps even to the extent that it is central to their identity (I will return to this aspect later). The model proposes that brands formulate their big ideal at the intersection of the brand’s best self and a cultural tension. In other words, the big ideal is the brand’s answer to a cultural tension, an answer that the brand can (uniquely) provide because its best self enables it to do so. Perhaps the most notable application of this model is Dove’s long-running ‘campaign for real beauty’, which married Dove’s best self of being a ‘caring brand’ to the cultural tensions around (female) body self-esteem and the unreal standards of beauty communicated by the fashion and beauty industry. While the big ideal model provides a good starting point, more academic work is needed to theorize and examine how brands establish a brand purpose, and the role of alignment between brands and (social) issues (cf., Champlin et al. Citation2019)

Consumer-issue alignment

As noted earlier in discussion of the impact of brand activism on consumers, consumer-issue alignment is the key determinant of consumer responses to brand activism, although this effect is moderated by a negativity bias, meaning that the negative impact of brand activism on consumers who disagree with the brand’s stance may be larger than the positive impact on people who agree. This does not mean, however, that brand activism cannot have a positive impact on brands, as shown by Hydock, Paharia, and Blair (Citation2020).

These authors find that the net impact of brand activism on brand preference is determined by the ratio of the market share of the brand and the amount of support for the advocated issue. To illustrate, let’s consider a brand with a market share of 20% (which is quite large for many markets) taking a stance that is highly controversial and supported by half of the population (and opposed by the other half). The brand’s activism would have detrimental effects on half of its customer base (which is 10% of the market), but it would also appeal to half of the 80% who do not currently buy the brand (which is 40% of the market). Following this logic, brand activism is likely to have a positive impact on the brand as long as the ratio of proponents and opponents of the issue is larger than the ratio of buyers to non-buyers. The strength of the earlier discussed negativity bias determines how much larger this ratio needs to be.

An additional factor is consumers’ (value-relevant) involvement with the issue (Li, Kim, and Alharbi Citation2022). Value-relevant involvement is higher when the issue is more closely related to consumers’ identity - in other words, when the issue is related to the social and personal values that are central to them. At higher levels of value-relevant involvement, people’s opinions about an issue have a stronger influence on their behavior (Cho and Boster Citation2005). To make this concrete: for the parents of a girl who identifies as lesbian, or for an employee who identifies as non-binary, there is tremendous value in knowing that the brand they buy or (want to) work for supports the LGBTQ community. This value is likely to be much higher than its negative impact on people who disagree with this stance. Recent research (Jungblut and Johnen Citation2022) on the endorsement of equality for LGBTQ supports this notion: while this study confirmed the general existence of a negativity bias (i.e. consumers were more likely to boycott a brand if they disagreed with it than they were to ‘buycott’ (support) a brand if they agreed with it), they also found that this negativity bias disappeared at higher levels of political interest. More specifically, the positive responses of consumers who agree with the brand are stronger when the issue is more relevant to their values, while negative responses are not influenced by value-relevance.

Perceived authenticity

Several studies have shown that consumers will only respond favorably to brand activism if they perceive the activism to be authentic. Inauthentic activism will not lead to positive brand responses, and may even backfire (Hydock, Paharia, and Blair Citation2020; Chu, Kim, and Kim Citation2022). A review of the literature on brand activism and related areas such as Cause-Related marketing and CSR suggests three key factors determining whether brand activism is perceived as authentic: (1) fit with brand purpose and values, (2) alignment with corporate practice, and (3) right tone of voice.

Fit with brand purpose and values - while some consumers may be explicitly aware of a brand’s values and purpose, most will have a more implicit awareness, built by (often years of) exposure to its products, advertising, and other forms of communication. Consumers’ mental networks of brand associations include knowledge and opinions about brand values and morals. A strong fit between activism and brand values facilitates the development of mental associations between the cause and the brand. The positive consequences of this have been demonstrated in the cause-related marketing domain: Pracejus and Olsen (Citation2004) show that a high (versus low) fit between cause and brand can result in 5-10 times more donations in cause-related marketing campaigns. Brand-cause fit can be based on functional associations or brand image associations (Bigné et al. Citation2012). Functional associations relate to the product or service (e.g. the Spanish water-brand Auara that uses its profits to secure drinking water in developing countries), customers (Pampers long running campaign supporting the vaccines for babies in developing countries), or location (many brands focus their CSR activities to local charities). Image-related associations are based on brand personality and cultural identity. The designs of Dutch streetwear brand Patta for example, are strongly embedded in urban culture. Their Patta Academy provides training and advice to young people from urban areas in Amsterdam who want to start their own business.

Alignment with corporate practice - Brand activism is perceived as authentic if it is aligned with consumers’ perceptions of the brand’s behavior in the past. Terms like ‘greenwashing’ and ‘wokewashing’ have been used to describe instances where this is not the case. Hydock, Paharia, and Blair (Citation2020) found that perceived inauthenticity reduces the positive impact of activism on consumers who agree with the brand, but it does not reduce the negative impact on consumers who disagree with the brand. If there is a large enough gap between a brand’s activism and its internal values and behaviors, the activism will be seen as corporate hypocrisy. Social or political activism from a company with poor labor circumstances or non-sustainable business practice can negatively impact buying intention and willingness to pay (Wagner, Korschun, and Troebs Citation2020), but also employee wellbeing and retention (Scheidler et al. Citation2019).

The brand’s prior history of activism may also be relevant: does the brand show leadership on the issue (do they ‘own it’?), and have a reputation for speaking out? Indeed, the success of Nike’s ‘Dream Crazy’ campaign with Colin Kaepernick has been attributed to Nike’s history of supporting athletes of color, and speaking out against discrimination, from being the first to feature an HIV positive athlete in the eighties, to a large campaign against anti-Islam sentiment in 2017 (Avery and Pauwels Citation2018). Empirical evidence for the role of brand leadership is provided by a recent natural experiment. In June 2020, a large number of major brands - including 31% of the Fortune 100 - showed their support of the Black Lives Matter movement by posting black squares on their Instagram accounts. Analyses showed that participation in this event had a negative impact on consumers’ engagement with the Instagram channels of these brands, especially for brands that did not previously speak out on this topic, and that were not otherwise involved with the BLM movement (Wang et al. Citation2022). In a similar vein, Wallach and Popovich (Citation2023) found that consumers perceive brands as more authentic and credible when they are transparent about the fact that their sustainability efforts are not only beneficial to the planet, but also to the firm.

The right tone of voice - Authenticity is also key in finding the right tone of voice for the brand’s social or political message. This message authenticity can be structured along four dimensions: (1) preserving brand essence, (2) honoring brand heritage, (3) connecting to consumers’ everyday lives, and (4) being realistic (Becker, Wiegand, and Reinartz Citation2019).

The first two dimensions reflect the idea that brand activism should be aligned with the brand’s ‘best self’ – not only in terms of its brand essence, but also in the way the brand communicates its stance (cf., Eigenraam, Eelen, and Verlegh Citation2021). An example can be found in Ben & Jerry’s, which communicates its opinions on social political issues in a way that is consistent with its DNA: irreverent, passionate, and with a sense of humor – for example by introducing the ‘Pecan resist’ ice cream flavor in protest of Trump’s presidency, or ‘Empower Mint’ to support equal opportunities in education.

The latter two dimensions – being realistic and connecting to consumers’ everyday lives - emphasize the importance of translating big issues into concrete and common concepts and actions that consumers can relate to. Through storytelling, a brand can use narratives to transport consumers into the worlds and lives of others. Stories elicit emotional responses and fuel consumers’ motivation to contribute to the cause or engage in behavioral change (Bublitz et al. Citation2016). Examples of such storytelling can be found in Oreos’ ‘Proud Parent’ movie, which showed a young woman introducing her girlfriend to her parents, or John Deere’s ‘Gaining Ground’ documentary, which told the story of black farmers in the US fighting to maintain or reclaim land ownership. Such content is usually created in cooperation with nonprofits who provide their knowledge and expertise, as well as lend credibility to the initiative. Such collaborations can also help brands to be concrete and translate their words into actions. In a recent study, Wulf et al. (Citation2022) showed that the use of vague (as compared to concrete) claims in pride-related advertising messages is more likely to evoke perceptions of rainbow washing, which have negative impact on consumer attitudes towards ads and brands.

Conclusion and call to action

Brands are in a position to establish social change and make progress on social issues. They have an enormous reach and visibility among consumers and other stakeholders, possess ample capabilities in management and marketing, and have considerable marketing budgets at their disposal (cf., Stafford and Pounders Citation2021). An activist brand can use these resources to achieve societal goals set by its management. Advertising messages can be crafted to raise awareness for societal issues and influence people’s attitudes to build support. By making choices that align with their opinions, brands can influence what consumers see and hear on a daily basis, thereby influencing their beliefs about what is (and what is not) accepted in society. Brand activism goes beyond advertising: brands can adapt their product assortment, pricing and distribution, in order to nudge consumers toward choices and behaviors that make a difference on the challenges that face our society.

In addition to contributing to social transformation, brand activism can elicit favorable emotional responses in consumers and employees, and enhance the extent to which people feel attached to the brand and identify with it. Activism shows what a brand stands for, and injects meaning into the brand. To ‘unlock’ these benefits, and maximize the value of activism for the brand and the issue it chooses to advocate, brand activism should be (1) aligned with the brand’s purpose and values, (2) aligned with the values and opinions of its customers (or the consumers that the brand seeks to target), and (3) make its stance in a way that is authentic, in the sense that it is in line with the brand’s offerings and heritage, and with the behavior of the organization behind the brand. The Aligned Activism Model may help brands engage in activism that echoes the success of Nike’s ‘Dream crazy’ campaign featuring Colin Kaepernick – a campaign that centers on an issue that is aligned with Nike’s best self as a socially conscious sports (fashion) brand, that resonates with the brand’s customers and that is communicated in a way that fits Nike’s heritage (Avery and Pauwels Citation2018). It may also be used to analyze less successful campaigns, such as Bud Light’s collaboration with transgender influencer Dylan Mulvaney, which has been associated with a marked drop in brand sales and in market value of its parent company Anheuser-Busch (Holpuch Citation2023). In a laudable attempt to promote diversity and inclusion, the brand took a stance that does not seem to be aligned with the views of a large part of its customers, and that does not have strong associations with the brand’s essence or (advertising) history.

A research agenda for brand activism

Input from academic research is essential in order to develop knowledge that can be of help to brand managers seeking to implement activist strategies. Following Bergkvist and Langner (Citation2023), it is important to have a closer exchange between practitioners and academics. This helps combine relevance and rigor in advertising research. Specifically, four relevant areas may be distinguished.

First, we need more extensive knowledge on the factors determining the impact of brand activism on consumers and employees. For example, while authenticity is widely recognized as an important determinant of the impact of brand activism, there is little research in this area, especially in the field of advertising. Another factor that deserves more attention is the role of controversy/divisiveness: how important is it for brand activism to focus on divisive issues, and what is the influence of divisiveness on the success of activism? Content analysis could be useful to establish the extent to which the stances taken by brands are controversial, and the impact of controversiality on consumers and other stakeholders could be measured for example by capturing online engagement or monitoring sales. In experimental research, controversiality could be manipulated and related to emotional and cognitive responses (see Chen and Berger Citation2013 for an example). The aligned activism model could guide research that studies these and other underexplored questions in brand activism, by helping research focus on the roles of brand-issue alignment, consumer-issue alignment, and perceived authenticity.

Second, it is of crucial importance to better understand the impact of brand activism on the issues it centers on. The earlier discussed framework developed by Eilert and Nappier Cherup (Citation2020) provides a good starting point by detailing how brands can help advance causes by raising awareness, by influencing attitudes, and by closing the intention-behavior gap. Further research is needed to provide a solid empirical foundation for the different effects that are proposed. Such research would benefit from intensive collaboration between academia and practice: not only with brands and agencies, but also with NGOs and other societal stakeholders. Field experiments could be used to measure the impact of brand activism ‘in the wild’ and measure its impact on awareness and behaviors at a larger scale (See Gneezy Citation2017 for a broader discussion).

Third, it is crucial to develop a deeper understanding of the impact of brand activism on employees. Experience at Unilever suggests that a shift toward a purpose-driven business model has a positive impact on employee attraction and retention (Nair et al. Citation2022), but it remains to be established whether this effect is generalizable, and how it differs between company contexts. A related question is how to engage employees in brand activism, and how to approach the likely situation where no everyone in the organization agrees on the brand’s stance. How does an organization give room for diversity in opinions? How can employees with diverse opinions still recognize themselves in the brand? To answer such questions, advertising researchers need to broaden their scope and focus on the impact of brand activism on job seekers and employees. Collaboration with organizations embarking on activist campaigns could provide useful insights, not only by conducting surveys among their employees, but also by measuring ‘harder’ variables like employee turnover, applications, and engagement.

Fourth, as brand activism further evolves as a practice, it is important to evaluate and (re)consider the definition of brand activism. Bergkvist and Eisend (Citation2023) outline seven criteria for proper definitions in advertising research: (1) specify all the construct’s necessary characteristics, (2) refrain from using vague or ambiguous terms, (3) not be tautological, (4) avoid overlap with other (related) constructs, (5) avoid relying on examples to define the construct, (6) be parsimonious, and (7) avoid including (hypothesis about) relationships between different concepts. In this paper, I have adopted the established definition of Mukherjee and Althuizen (Citation2020), which meets most of these criteria, but scores weak on criterion 2, with its ambiguous use of the terms ‘public’ and ‘divisive’. When is an issue divisive? And how does it depend on the side that the brand takes? If 90% of a society agrees that human responsibility for climate change is real, is it divisive to communicate this stance? Or is it only divisive when a brand says that climate change is not real? And at what percentage do the answers to these questions change? Such issues need to be further theorized, especially because the answers are related to the extent to which there is an overlap between brand activism and other constructs like CSR (criterion 4). Finally, as pointed out by Bergkvist and Eisend, definitions may need to be adapted in response to changes in society and in marketing practice. For an emerging practice like brand activism, this observation is extremely relevant.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Appels, M. 2023. CEO sociopolitical activism as a signal of authentic leadership to prospective employees. Journal of Management: 014920632211102. forthcoming

- Avery, J., and K. Pauwels. 2018. Brand activism: Nike and Colin Kaepernick. Harvard Business Review, Case No. 519046.

- Baumeister, R.F., E. Bratslavsky, C. Finkenauer, and K.D. Vohs. 2001. Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology 5, no. 4: 323–70.

- Becker, M., N. Wiegand, and W.J. Reinartz. 2019. Does it pay to be real? Understanding authenticity in TV advertising. Journal of Marketing 83, no. 1: 24–50.

- Berger, J.A, and C. Heath. 2008. Who drives divergence? Identity-signaling, outgroup dissimilarity, and the abandonment of cultural tastes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 95, no. 3: 593–607. [InsertedFromOnline]

- Bergkvist, L., and M. Eisend. 2023. Changes in definitions and operationalizations in advertising research- justified or not? Journal of Advertising 52, no. 3: 468–76.

- Bergkvist, L., and T. Langner. 2023. A comprehensive approach to the study of advertising execution and its effects. International Journal of Advertising 42, no. 1: 227–46.

- Bernritter, S.F., A.C. Loermans, P.W. Verlegh, and E.G. Smit. 2017. ‘We’ are more likely to endorse than ‘I’: The effects of self-construal and brand symbolism on consumers’ online brand endorsements. International Journal of Advertising 36, no. 1: 107–20.

- Bhagwat, Y., N.L. Warren, J.T. Beck, and G.F. Watson. IV, 2020. Corporate sociopolitical activism and firm value. Journal of Marketing 84, no. 5: 1–21.

- Bigné, E., R. Currás-Pérez, and J. Aldás-Manzano. 2012. Dual nature of cause-brand fit: Influence on corporate social responsibility consumer perception. European Journal of Marketing 46, no. 3–4: 575–94.

- Bublitz, M.G., J.E. Escalas, L.A. Peracchio, P. Furchheim, S. Grau, A. Hamby, M.J. Kay, M.R. Mulder, and A. Scott. 2016. Transformative stories: A framework for crafting stories for social impact organizations. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 35, no. 2: 237–48.

- Champlin, S., Y. Sterbenk, K. Windels, and M. Poteet. 2019. How brand-cause fit shapes real world advertising messages: A qualitative exploration of ‘femvertising. International Journal of Advertising 38, no. 8: 1240–63.

- Chen, Z., and J. Berger. 2013. When, why, and how controversy causes conversation. Journal of Consumer Research 40, no. 3: 580–93.

- Cho, H., and F.J. Boster. 2005. Development and validation of value-, outcome-, and impression-relevant involvement scales. Communication Research 32, no. 2: 235–64.

- Chu, S.-C., H. Kim, and Y. Kim. 2022. When brands get real: The role of authenticity and electronic word-of-mouth in shaping consumer response to brands taking a stand. International Journal of Advertising : 1–28.

- Dastidar, A., S. Sunder, and D. Shah. 2023. Societal spillovers of TV advertising – social distancing during a public health crisis. Journal of Marketing 87, no. 3: 337–58.

- Edelman. 2022. The trust barometer. https://www.edelman.com/trust/2022-trust-barometer

- Eigenraam, A.W., J. Eelen, and P.W.J. Verlegh. 2021. Let me entertain you? The importance of authenticity in online customer engagement. Journal of Interactive Marketing 54: 53–68.

- Eilert, M., and A. Nappier Cherup. 2020. The activist company: Examining a company’s pursuit of societal change through corporate activism using an institutional theoretical lens. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 39, no. 4: 461–76.

- Escalas, J.E, and J.R. Bettman. 2003. You are what they eat: Influence of reference groups on consumers’ connections to brands. Journal of Consumer Psychology 13, no. 3: 339–48.

- Garg, N., and G. Saluja. 2022. A tale of two “ideologies”: Differences in consumer response to brand activism. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research 7, no. 3: 325–39.

- Gneezy, A. 2017. Field experimentation in marketing research. Journal of Marketing Research 54, no. 1: 140–3.

- Hajdas, M., and R. Kłeczek. 2021. The real purpose of purpose-driven branding: Consumer empowerment and social transformations. Journal of Brand Management 28, no. 4: 359–73.

- Hartmann, P., A. Marcos, and V. Apaolaza. 2023. Past, present, and future of research on corporate social responsibility advertising. International Journal of Advertising 42, no. 1: 87–95.

- Holpuch, A. 2023. Behind the backlash against Bud Light’s transgender influencer. New York Times, May 4, https://www.nytimes.com/article/bud-light-boycott.html (accessed June 2, 2023).

- Hydock, C., N. Paharia, and S. Blair. 2020. Should your brand pick a side? How market share determines the impact of corporate political advocacy. Journal of Marketing Research 57, no. 6: 1135–51.

- Jungblut, M., and M. Johnen. 2022. When brands (don’t) take my stance: The ambiguous effectiveness of political brand communication. Communication Research 49, no. 8: 1092–117.

- Keller, K.L. 2014. Designing and implementing brand architecture strategies. Journal of Brand Management 21: 702–15.

- Kristofferson, K., K. White, and J. Peloza. 2014. The nature of slacktivism: How the social observability of an initial act of token support affects subsequent prosocial action. Journal of Consumer Research 40, no. 6: 1149–66.

- Li, J.Y., J.K. Kim, and K. Alharbi. 2022. Exploring the role of issue involvement and brand attachment in shaping consumer response toward corporate social advocacy initiatives: The case of nike’s colin kaepernick campaign. International Journal of Advertising 41, no. 2: 233–57.

- Mkrtchyan, A., J. Sandvik, and Z. Zhu. 2023. CEO activism and firm value, March 28.

- Mukherjee, S., and N. Althuizen. 2020. Brand activism: Does courting controversy help or hurt a brand? International Journal of Research in Marketing 37, no. 4: 772–88.

- Nair, L., N. Dalton, P. Hull, and W. Kerr. 2022. Use purpose to transform your workplace. Harvard Business Review 100, no. 2: 52–5.

- Pracejus, J.W, and G.D. Olsen. 2004. The role of brand/cause fit in the effectiveness of cause-related marketing campaigns. Journal of Business Research 57, no. 6: 635–40.

- Rosengren, S., and N. Bondesson. 2014. Consumer advertising as a signal of employer attractiveness. International Journal of Advertising 33, no. 2: 253–69.

- Roth, P.L., J.D. Arnold, H.J. Walker, L. Zhang, and C.H. Van Iddekinge. 2022. Organizational political affiliation and job seekers: If I don’t identify with your party, am I still attracted? The Journal of Applied Psychology 107, no. 5: 724–45.

- Ruttan, R.L, and L.F. Nordgren. 2021. Instrumental use erodes sacred values. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 121, no. 6: 1223–40. [InsertedFromOnline]

- Schaefer, S.D., R. Terlutter, and S. Diehl. 2020. Talking about CSR matters: Employees’ perception of and reaction to their company’s CSR communication in four different CSR domains. International Journal of Advertising 39, no. 2: 191–212.

- Scheidler, S., L.M. Edinger-Schons, J. Spanjol, and J. Wieseke. 2019. Scrooge posing as mother teresa: How hypocritical social responsibility strategies hurt employees and firms. Journal of Business Ethics 157, no. 2: 339–58.

- Shaw, J., and C. Mitchell. 2011. What’s the big ideal? Ogilvy & Mather.

- Stafford, M.R, and K. Pounders. 2021. The power of advertising in society: Does advertising help or hinder consumer well-being? International Journal of Advertising 40, no. 4: 487–90.

- Wagner, T., D. Korschun, and C.C. Troebs. 2020. Deconstructing corporate hypocrisy: A delineation of its behavioral, moral, and attributional facets. Journal of Business Research 114: 385–94.

- Wallach, K.A, and D. Popovich. 2023. Cause beneficial or cause exploitative? Using joint motives to increase credibility of sustainability efforts. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 42, no. 2: 187–202.

- Wang, Y., M.S. Qin, X. Luo, and Y.E. Kou. 2022. How support for black lives matter impacts consumer responses on social media. Marketing Science 41, no. 6: 1029–44.

- Wowak, A.J., J.R. Busenbark, and D.C. Hambrick. 2022. How do employees react when their CEO speaks out? Intra- and extra-firm implications of CEO sociopolitical activism. Administrative Science Quarterly 67, no. 2: 553–93.

- Wulf, T., B. Naderer, J. Hohner, and Z. Olbermann. 2022. Finding gold at the end of the rainbowflag? Claim vagueness and presence of emotional imagery as factors to perceive rainbowwashing. International Journal of Advertising 41, no. 8: 1433–53.

- Yang, J., P. Chuenterawong, and K. Pugdeethosapol. 2021. Speaking up on black lives matter: A comparative study of consumer reactions toward brand and influencer-generated corporate social responsibility messages. Journal of Advertising 50, no. 5: 565–83.