Abstract

The rapid development of digital technologies and their increasing application in many areas of everyday life challenge all citizens to continuously learn digital skills. This also applies to older adults, among whom digital literacy is on average less well-developed than among younger adults. This article investigates why retired older adults participate in opportunities to learn digital skills. Multiple case design with both qualitative and quantitative methods was used to include the views of older adults from Austria, Finland, and Germany. The results of this interdisciplinary study indicated individual, social and technical reasons for their participation in digital skills training. Practical implications and recommendations for future studies are suggested.

Introduction

Demographic change, growing participation rates in general adult education (Eurostat Citation2017), and the emergence of the ‘third age’ have given rise to increased learning in late adulthood throughout Europe (Findsen and Formosa Citation2016). Educational gerontology, the scientific discipline concerned with learning in later years (Glendenning Citation2008), has consequently explored older adults’ capabilities, motivations, and outcomes of learning in various ways and contexts, including the use of digital technology. Currently, more research is needed to broaden the view of reasons why older adults seek digital support, and their reasons for using digital technology (Muñoz-Rodríguez et al. Citation2020, p. 14), to develop services to cater for their actual needs and ways of learning.

This article presents an extract of surveys and results from an interdisciplinary and transnational research project ACCESS - Supporting digital literacy and appropriation of ICT by older people. Different learning opportunities for retired older adults with low technical skills were implemented, explored, and evaluated. Learning opportunities refer to diverse local settings that were examined, considering both informal and non-formal learning approaches. By studying reasons for participation in opportunities for learning digital skills, it is possible to support older adults’ interest in learning digital skills as well as their participation in digital support activities. The results can also be used to support the planning and implementation of digital support for older adults (see also Pihlainen and Ng Citation2022). The guiding research questions of this article are: (1) What are the reasons of older adults for participating in digital skill learning opportunities? (2) How can this knowledge be used to motivate older adults to participate in digital skills learning?

Literature review

Reasons to learn in later life

A recent study on motivation to participate in senior university programmes found that instrumental motivation—meaning motivation to use the acquired knowledge in various contexts of everyday life—is a key factor in learning in later life (Ackermann and Seifert Citation2021). In contrast to learning in earlier life stages, learning in later life is not directed towards job performance (Withnall Citation2010), which highlights the need to understand the motivations of older learners in the context of their everyday lives and immediate values.

In terms of digitalisation, research has shown that older adults’ intrinsic motivation to learn is particularly high if the interaction with new technology is closely related to their social space and everyday life (BMFSFJ Citation2020). According to Maderer and Skiba (Citation2006), the goals of older learners can generally be categorised into three categories, i.e. person-centred goals (e.g. development or conservation of mental and physical competence or life satisfaction), fellow-centred goals (e.g. goals that address social responsibility or engagement) and attentiveness and matter-centred goals when older adults want to be confronted with new challenges in personally meaningful domains. Similar goals have been found in older adults learning digital skills (e.g. Tyler et al. Citation2020). Based on these changing reasons for learning in later life, research in educational gerontology has argued that motivations to learn in later life, and the ways adults learn in later life, are profoundly different than in younger years (Leen and Lang Citation2013), as younger adults might learn rather strategically for a specific certificate or their professional careers, while older adults, particularly those after retirement, might learn in more informal ways (e.g. through reading or self-directed learning) and for motivations that are closer to everyday-life (e.g. being able to speak a foreign language when travelling). These studies have therefore concluded that learning in later life should be studied with different theories and concepts than education in earlier life stages.

Benefits of learning for older adults

Research has also highlighted that engagement in education and learning in various fields—digital or not—can have profoundly positive effects on older adults’ quality of life, their outlook on life, and images of ageing (Jenkins and Mostafa Citation2015), particularly in the context of digital technologies. Numerous studies have provided considerable evidence demonstrating a positive association between involvement in online activities and well-being in later life (for reviews, see: Choi et al. Citation2012), Forsman and Nordmyr Citation2017), with some also demonstrating causality by applying longitudinal methods (e.g. Choi et al. Citation2012). Furthermore, digital technology promotes social inclusion (Seifert et al. Citation2018, Citation2021). It is an important part of modern communication (Chopik Citation2016, Quan-Haase et al. Citation2017), and of participation in the community and in society (Nimrod Citation2010, Sayago et al. Citation2013), e.g. by political participation and volunteering.

Obstacles to participation

In general, older adults are difficult to reach with non-formal learning opportunities, and non-users of digital technology have a low participation rate in non-formal learning (Gallistl et al. Citation2020). Especially in groups with low education, low income, poor health, a migrant background, or various disabilities, the use of digital technologies is less common, and digital training programmes for these groups hardly exist (Ehlers et al. Citation2020). Older adults’ health status, gender aspects as well as financial resources, and biographic experience of formal and non-formal learning influence the probability that older adults participate in learning environments (König et al. Citation2018, Garcia et al. Citation2021).

In this study, we refer to ‘reasons to learn digital skills’ that emphasise a wider approach to learning compared to ‘motivation’ (for motivation, see, e.g. Kaše et al. Citation2019, Tyler et al. Citation2020), which describes the psychological processes contributing to skill development. Reasons, in turn, can also capture the experiences of those older adults who come to digital training sessions even if they are not motivated. In general, there is a lack of literature on the reasons of older adults to participate in training programmes with the aim to increase digital skills, because research addressing the subject ‘ageing, technology and learning’ amounts to only a minor field of scientific activities (Jokisch and Wahl Citation2015).

Context

In this article, we will present studies with multiple disciplines and methods from three European countries (Finland, Germany, and Austria) with rather different policies regarding digital education in later life. The prevailing political structure influences the learning opportunities for older adults and therefore their participation possibilities, which is why we first present a short overview. In Finland, the Ministry of Finance (Citation2017) is responsible for developing public services to become user-oriented and primarily digital in the future and is especially focussed on increasing the digital literacy of older adults and other vulnerable groups (Ministry of Finance Citation2018). Therefore, there is a wide range of learning opportunities for older adults, that are provided mostly by non-governmental organisations as well as by cities and municipalities, companies, national institutions, universities, and adult education organisations.

In Austria and Germany, digitalisation and digital inclusion are important political topics, although they are seldom discussed in relation to demographic change. An analysis of the most important Austrian policy papers about older adults shows that the political goal for the older population lies mostly in an increase in quality of life, with only a marginal mention of digital inclusion (Gallistl et al. Citation2020). Quite recently, German policy-makers started to discuss digital inclusion in later life under the umbrella policy of life-long learning (BMFSFJ Citation2020). Therefore, in both countries, there are only scattered opportunities for older adults to learn how to use digital technologies, mostly organised by charities, ecclesiastical institutions, or adult education centres.

Methods

The multiple-case design was employed in this study to explore the research question in various contexts. The case studies were conducted as part of an interdisciplinary 3-year EU- project, ACCESS. We refer to a definition by Creswell (Citation2017), in which the case study method ‘explores in depth a program, event, activity, process, or one or more individuals. The case(s) are bounded by time and activity, and researchers collect detailed information using a variety of data collection procedures over a sustained period of time’. Multiple-case design (or collective case design) enables a deeper comprehension of the bounded cases compared to a single case, because of a possibility to trace processes, outcomes, environmental effects, and conditions across the cases (Mills et al. Citation2010). ‘Furthermore, it allows the researcher to have a deeper understanding of the explorative subject, the evidence generated from a multiple case study [design] is strong and reliable […]’ (Brink Citation2018, p. 243). For us, the multiple-case design allowed a multi-perspective and comprehensive approach in analysing older people’s reasons for participating in digital skill learning based on several data collection with different methods and in different societal contexts.

This study followed a parallel design in which all the case studies were selected in advance and were conducted within a limited period. We followed two stages in implementing the study and reporting the results: (1) Each case in the research was treated as a single case, and (2) Cross-case comparisons were conducted. The identified data layers were depicted, key variables were clarified, and by repeated analysis of the data, it was determined how they are structured in each case. Next, we describe each case study separately ().

Table 1. Data collected in country case studies.

The first case study was conducted by researchers of the Department of Sociology (IFS), University of Vienna, Austria, and draws on data from a qualitative study. Data was collected from five information and communications technology (ICT) beginners’ courses for older adults in Austria. In order to gain a deeper understanding of learning processes in older age, the research group conducted semi-structured interviews with participants and additionally asked them to be co-researchers by investigating their everyday lives regarding the following research questions: ‘Why is it important that older adults use digital technologies?’ and ‘Why is it difficult to use digital technologies in later life?’. To answer these questions, the interviewees kept a visual diary (Pilcher et al. Citation2016) and took photos of situations from their everyday lives. These photos were discussed after the semi-structured interviews. In total, the research group received 103 photos from the interviewees either via WhatsApp or printed. The interviews with nine-course participants lasted for between 36 and 118 min (Mean = 84 min) and were audio recorded and later transcribed verbatim in German. Because of the high proportion of female participants in the five courses, the sample consists of eight women and one man (61–81 years). Situation analysis (Clarke Citation2012) was used to analyse the data. Situational analysis is a qualitative method for data analysis, which defines a broad situation as the unit of analysis. Through inductive coding of the interview material, researchers identified central actors that shaped the observed situation (e.g. human actors, such as older learners and teachers, but also non-human actors, such as classrooms, pens, or technological devices). Through this circular mapping of situations, we identified central actors and topics in the interviews that formed the basis for the results presented in this article.

The second case study was conducted by researchers of the Department of Special Education at the University of Eastern Finland (UEF), Finland. The data was collected with a nation-wide questionnaire that was shared online and in paper format and in older adults’ organisations and adult education organisations. Older adults were asked to answer a multiple-choice question: What is your reaction to the following statements concerning your reasons to participate in digital skills teaching? The respondents were provided with an alternative ‘Other reason’ and a possibility to explain their choice in the case of an open-ended question. In this article, we present the results from the respondents who were over 65 years old (65–89, mean 72, N = 156). Of these, 71% were women and 29% were men. 65% of respondents studied in adult education organisations and 35% in peer guidance.

We also interviewed seven women and one man who participated in digital skills peer learning sessions. The mean age of the interviewees was 75.9 years (70–81 years). The digital skills of the older adults in interviews and questionnaire data varied from beginners to advanced. Seven interviews were conducted online and one face-to-face. All the interviews were audio recorded and later transcribed verbatim in Finnish. Questionnaire data was analysed using descriptive statistics in SPSS software, and interviews were analysed using thematic content analysis (Clarke and Braun Citation2014).

The third case study was conducted by the Research Association for Gerontology (FfG)/Institute for Gerontology at TU Dortmund, Germany. This case study refers to a quantitative survey in ICT-courses (smartphone, tablet, laptop, PC, etc.). The training was focussed on older people with little or no digital competencies. We cooperated with five providers of educational services for older people in North Rhine-Westphalia. They were selected for project participation because of their extensive experience in the field of ICT-learning for older people. In all, 214 older learners from more than 30 courses filled in a questionnaire. The average age was 72 years (range 51–89 years) and 74% of the respondents were women.

The fourth case study was conducted by researchers of the Department of Information Systems at the University of Siegen (USI), Germany. The data were collected within the context of a long-term participatory design (PD) study (Kensing and Blomberg Citation1998, Müller et al. Citation2015, Joshi and Bratteteig Citation2016) focussing on co-design of tools and methods to foster older adults’ digital literacy, specifically through their inclusion in participatory design processes.

The study was conducted by using ethnographically informed and longitudinal, action research-oriented methods in a small German city. These include activities for gaining experiences with digital devices to help older adults to become capable of engaging in co-design activities of the technologies and interventions to be developed. This co-design approach focuses on older adults’ learning processes, with ‘Experience-based Participatory Design Workshops’ (Hornung et al. Citation2017). Activities with co-researchers during the PD project occurred in two locations: (1) Visits of the researchers to a local senior computer club for ethnographic and action research activities. (2) Participation of older adults in regular series of on-site (at the University lab) and online workshops. Older participants were recruited by contacting a local senior computer club as well as by public events and newspaper advertisements.

In this text, the empirical material is presented as descriptions based on our ethnographic understanding of our data:

16 h of participatory observations at the local senior club, documented by taking field notes.

participatory design workshops were organised, taking place both onsite (before and after COVID-19 restrictions) and online (during COVID-19 restrictions). All the online sessions were recorded, producing over 50 h of recorded video material; all the onsite sessions were documented by taking field notes, making short videos, and taking photos. Relevant sections of the video recordings were transcribed and used for further analysis.

numerous informal interviews were conducted in conjunction with supporting the older participants in the use of digital technology.

The sample consisted of four men and thirteen women (aged 65–89). The digital literacy of the participants had a broad range, from complete beginners to highly experienced. The data was analysed in line with the ethnographic approach (Creswell and Poth Citation2018)—through repeated reading of the collected material, writing memos and reflecting on the material, and developing descriptions and themes connected to the participation of older adults and their learning to use digital tools.

Results

The variety of older people’s reasons to participate in digital skills training showed that older adults are a heterogenous group that cannot be reached with a one-fits-all learning strategy. The results of this multiple case study indicated three groups of reasons why older adults participated in digital skills training (see ). Social, individual, and technical reasons appeared in all three countries, but the emphasis on the groups of reasons differed somewhat between the case studies. In the following, we describe the reasons for each group in a detailed way based on the country's case studies.

Table 2. Older adults’ reasons to participate in digital skills learning opportunities.

Case study: Austria

In the Austrian case study, six reasons for older adults to participate in ICT courses could be identified. The first reason for the interview partners to engage in ICT was to have social contacts. Some wanted to make new friends, and others joined the course together with their friends and wanted to intensify their relationships. However, the social environment was not mentioned only regarding social contacts, but also regarding missing support, especially from relatives. Therefore, the second reason to attend the course was to obtain digital support. Either the respondents did not have a support network, e.g. grandchildren who might help them when having problems with digital devices, or they experienced the support of their relatives as unhelpful, patronising, and impatient.

The third reason to attend ICT-courses was to gain independence from the support of other people, e.g. their friends and family, and to be able to manage their everyday life. Some interview partners felt themselves to be a burden on their relatives and therefore tried to find support from outside the family by joining an ICT course. Hence, most interview partners regarded digital literacy as necessary for an independent and autonomous life.

The fourth reason for course participation, identified in the Austrian data, was the feeling of social pressure. All interviewees were surrounded by digital technology in their everyday lives. They possessed diverse digital devices, such as smartphones, cars, or stereos. Even though most participants described how interesting this new digital world was, they also shared many stories about situations in their everyday lives in which they felt forced to use digital technology, or failed to use it. For example, one participant had to acquire an email account because a service provider switched to online-only communication:

Well, I thought I don’t need it [an email account], but I realize over and over that it does not work without it. Since you always [hear]: “Do you not have an email account? Do you not have this?” For God’s sake: “No, I do not!” And now I registered everything. But we are forced to do it, because nobody wants to talk on the phone with someone anymore or somehow personally. Now I thought I have to start with it so I can keep up just a little bit (woman, 71 years).

Only one interviewee attended the course because he perceived engaging with ICT as a hobby, which was the fifth reason for participating in ICT-courses. He enjoyed talking and reading about ICT and trying new things on his computer together with his friend. However, most of the participants described the process of learning ICT as rather stressful and perceived it as something they had to do.

Finally, for one participant the reason to attend ICT courses, as well as language and handcraft courses, was to stay active and healthy in later life. For her, engaging in learning processes was a means to stay mentally fit in later life. ICT was only one of her many interests.

Although older adults are open to a lot of things, one does not get younger. And learning; if you stop learning for a long time, I don’t know. It is of course easier to say: ‘Why do I need English, I don’t travel anywhere’. Maybe this is true, but the brain has something to do, and I think this is better than just reading the traffic news (woman, 61 years).

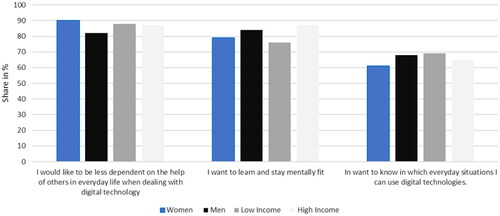

Case study: Finland

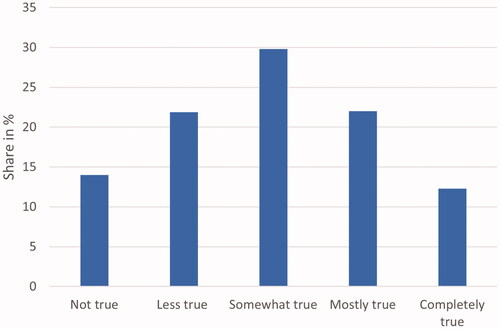

In a multiple-choice question in a questionnaire study, the reasons of Finnish older adults referred to social, individual, and technical aspects. Older adults claimed to participate in digital skills sessions because they wanted to stay active by keeping up-to-date in the use of digital devices, or they needed digital support (see ). Older adults also wanted to stay independent by strengthening their self-confidence to use digital devices or to stay active by learning something new through digital skills acquisition. These results were also reflected in an open-ended question. A 73-year-old man participating in an ICT course in adult education noted that ‘devices and programs develop. I want to keep up with development’. The same idea was reflected by a 70-year-old woman who participated in digital skills teaching in adult education: ‘to maintain the certainty to use (digital devices)’.

Figure 1. Older adults’ reasons to participate in digital skills learning (N = 148, 0 = I totally disagree, 5 = I totally agree).

However, many older adults experienced external pressure, being forced to learn digital skills because of external reasons, such as the rapid development of digital devices and services or personal changes in themselves or their closest ones. One 76-year-old woman learning digital skills in adult education explained that ‘due to the sickness of my husband, I have to take care of bank services and other issues’. The transfer from face-to-face to online services also increased pressure to learn digital skills: ‘People are forced to use ICT. For example, bank services must be dealt with online, otherwise they are really difficult’ (ICT learner in adult education, man, 66 years).

The interview data was in line with the results from the questionnaire. In the interviews, older adults often referred to the need for digital support because of the change from constant IT support provided by an employer during working life to the situation in retirement, when older adults needed to search for digital support suitable for their needs. For example, a 76-years old male tutee described that ‘to get more information—I left working life—and there are still these phones—and iPads—so (I participated in a digital skills peer tutoring session) to be better at using them’. Many older adults had precise needs when entering the digital skills learning sessions. Practical issues prompted them to ask for digital support and help and, therefore, continue using digital technologies. As one 81-year old female tutee put it: ‘I did this update—and it threw all these icons differently—so I thought I would go and ask how to turn it back to the old way’.

Some older adults explained that participating in digital skills learning situations was their hobby, that fulfilled their need to learn something new and brought meaningful, regular activity to their daily life. These older adults experienced that they belonged to a minority because they were intrinsically interested in learning digital skills: ‘I suppose it’s my endless curiosity in these matters, or my curiosity to figure things out. I was not resistant to change when these new devices became available, I was an exception in that sense’ (woman, 81 years). In conjunction with digital skills, many older adults emphasised social contacts in digital skills learning situations: ‘We have a very good, nice group of people and the meetings are fun’ (woman, 70 years). For some older adults, socialising seemed to be the main reason to join the sessions, and they absorbed new knowledge and digital skills almost without noticing.

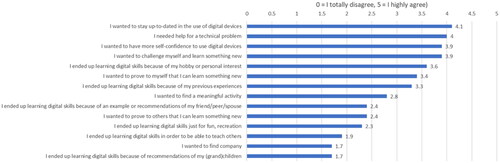

Case study: Germany A

In the German (FfG) quantitative survey the three most frequently mentioned reasons for participating in digital skill courses were related to social and individual factors (multiple answers were possible): (1) Gaining independence: 87% of the participants wanted to be less dependent on the help of others in using digital technology. (2) Staying active and mentally fit: 82% marked the motivation of wanting to learn something new and stay mentally fit. The third most frequently cited reason was to learn about everyday situations in which they can use digital technology: 69% were interested in this connection between technical possibilities and their concrete application in daily life.

Reasons related solely to technology were given somewhat less frequently: 55% of respondents indicated that they had bought or received a device as a gift and now wanted to learn how to use it. 32% listed the need for advice on the purchase or installation of a device as a motive, and 31% reported that they had a concrete problem/concern with a technical device they already used.

Social pressure played an important role for another large proportion of course participants: ‘People from my close environment think that I should deal with modern technology/a certain device’ (41%). This contrasted with a significantly smaller proportion of respondents, 24%, for whom digital literacy was linked to a positive image of age (‘If I can use modern technology, I feel younger’). Financial considerations were of similar importance: 21% said they participated in the course because it was offered free of charge. Social contact (‘I would like to get to know other people or meet them’) was a motive for 17%.

Regarding the three most often named reasons, the differences based on income and gender were comparatively modest. As can be seen in , differences between women and men and according to income were rather small. The share of women who said they wanted to be less dependent on the help of others in everyday life when dealing with digital technology was about ten percentage points higher, whereas a slightly higher share of men presented the reasons ‘I want to learn and stay mentally fit’, and ‘I want to know in which everyday situations I can use digital technologies’. The differences according to income were also rather small. There was almost no difference for the first reason. A higher share of those with high income said ‘I want to learn and stay mentally fit’, while those with low income more often named, ‘I want to know in which everyday situations I can use digital technologies’ as a reason.

Figure 2. Share of respondents who mentioned the three reasons (in %) divided by gender and income (N = 214).

At the third wave of the survey in January 2021, the former course participants were asked whether their interest in digital technology had increased due to COVID-19 pandemic. In all, 64.1% percent of the respondents indicated that this was true at least to a certain extent. Approximately 35.9% said that this statement was less or not true. These answers did not correlate with formal education level, age, or self-rated ICT-skills. However, the answers did show significant correlations with the openness of the respondents to digital technology/curiosity to try out new digital devices, with frequent application of course contents, and with the participants’ financial resources ().

Case study: Germany B

In the German (USI) study, the following themes were identified. First, the older adults joined the PD sessions for staying active and as a hobby: not only to learn about novel digital technologies but also to experiment and practice using digital devices in a safe situation. In addition, the older adults appreciated the chance to get to know and to engage with digital ‘future’ themes, on which they would probably not otherwise be able to receive information (e.g. future topics, such as robotics). In this respect, a crucial factor for the older learners to engage with devices and applications new to them was digital support, i.e. to have direct access to a person who was able, willing, and patient enough to provide suitably adapted support when they were engaging with the digital tools. This often stood in contrast to their experience with family members, who did not have the same resources as researchers. Understanding of the PD sessions as a safe context to experiment and practice was not established only during meetings, but mainly over a longer period as the older adults often joined several university projects over many years.

Second, learning to use technology represented a different way to enrich their social contacts. Going to the local computer club was often part of a daily routine—for the older adults, it was important to be able to come regularly on the same day of the week, as that allowed them to join the same group of people. For some older adults, learning was not the main reason to join this learning context, but rather it was socialising, for example, eating a cake together with others, or accompanying a significant other. Similar reasons were observed during the PD sessions—it was important for the older adults to join the PD sessions on a regular basis and to engage socially with all the participants. In addition, especially the intergenerational character of the PD session was highly appreciated by the older adults.

The third reason was the external pressure from society to learn digital skills. For many of the older adults, learning to use digital technology was not something they voluntarily focussed on but rather something they perceived as necessary. One of the participants said: ‘I do not want to use [digital technology], but I have to’ (female, 67 years). Anticipating problems in the future in connection with exclusion from relevant contexts due to increasing digitalisation, or limits in one’s own mobility, were strong reasons for many to start engaging with learning to use the digital devices as soon as possible.

The local computer club was a peer-led organisation—it was established and led by a group of older adults. This group of people spent extensive time on making the club work as a safe environment for older adults to learn technology as well as to develop their own competence within the digital world. Older adults perceived technology as a hobby, which was further reflected in the older adults joining the PD sessions to learn to use digital devices. Coming to the university in order to join the PD sessions was perceived as an ‘exciting’ experience, which was different from their regular daily lives.

Some older adults came to the local computer club only for receiving digital support: They wanted to get things fixed when they experienced problems with their devices, rather than for the purpose of longitudinal learning. The PD sessions were also organised in line with this need—they became spaces where it was possible not only to support the learning of the older adults about the use of new technologies but also to provide immediate feedback and support for the technologies the older adults used. In addition, instructions provided by the developers of the current digital technologies were often perceived as insufficient, and hence older adults had the need to find contexts in which they could make sense of how to use digital technologies in a meaningful way.

Discussion

This study shows that many older adults participated in digital skills training because they either wanted to intensify existing relationships with friends and family or to make new friends. This finding supports earlier studies that emphasise the social aspects of learning and the use of digital technology in older adults (e.g. Chopik Citation2016, Quan-Haase et al. Citation2017) and, simultaneously, the importance of digital technology for social inclusion (Seifert et al. Citation2018, Citation2021). For this group of older adults, digital technology appears to be a facilitator of social contact. Therefore, to encourage these older adults to learn digital skills, advertisements should emphasise the personal benefits, such as ‘staying in contact with relatives’, rather than the learning process ‘learn how to use a smartphone’. This fits with the general insight that especially older technology-distant people need guidance about possible connections between digital technology and their lifeworld (Schirmer et al. Citation2022).

Simultaneously, some older adults participated in digital skills learning opportunities because they wanted to gain independence in their everyday life and learn digital skills by themselves. In this highly digitalised world, many older adults feel dependent on the help of relatives and friends. Earlier studies (Springett et al. Citation2018, Pihlainen et al. Citation2021) have suggested that digital training sessions support both independence and positive interdependence of older adults, contributing to both their learning and well-being. Thus, social aspects as well as staying independent should be addressed more in digital skills training course programmes to better match older adults’ individual needs and preferences.

Older adults’ reasons to participate in digital skills training were also connected to personal, individual aspects. Many older adults wanted to stay active and up to date with digital technology development for the sake of learning and their own interest. Updating digital skills enables participation in the community or society (Nimrod Citation2010, Sayago et al. Citation2013), even though these wider goals were not actualised in the findings of this study. Lifelong learning is seen as part of independent, healthy and secure living (UNECE Citation2019), and learning digital skills is reflected in the increasing number of older adults using digital technologies (e.g. Official Statistics of Finland Citation2021). When older adults engage with digital technology as a hobby, they actualise intrinsic motivation that reflects their interests, enjoyment, and inherent satisfaction (Ryan and Deci Citation2020). Simultaneously, participation in digital skills training as a hobby can also reflect the social aspects of learning and free-time activities of older adults.

All learning is not, however, based on intrinsic motivation (see also Ryan and Deci Citation2020). Older adults may find themselves on a regular basis in precarious situations in which they need to face the rapidly increasing digitalisation of society. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, digital technology became the easiest and almost the only available solution to reduce the effects of social isolation as well as to obtain access to basic services, such as appointments, shopping, etc. (see e.g. Garcia et al. Citation2021). For those not digitally literate, conditions, such as the outbreak of a pandemic might have various negative consequences, ranging from slight inconvenience to full social exclusion. Hence, older adults need to find their own reasons to learn something that might not come automatically based on their own personal interests. Due to various needs stemming from external reasons, different types of sustainable systems to support learning of digital skills by older adults are necessary.

Many older adults experience a lack of resources in their social surroundings and need to engage with learning contexts, such as courses focussing on digital literacy or PD sessions. Most digital technologies are not accompanied by instructions that the older adults would be able to make sense of. This resonates with previous research emphasising that if the content and teaching approaches are connected to the older people’s needs, values, and desires, the learning of new digital skills is facilitated as it is integrated into the older adults’ lifeworld (Schirmer et al. Citation2022). Participatory design workshops as learning environments specifically provide joint imagination spaces where older adults may get a sense of different kinds of technologies in a safe environment, i.e. interaction and negotiation with and about digital tools under the guidance of researchers (Hornung et al. Citation2017). Feeling safe, therefore, can be a personal, unconscious reason for some older adults to participate in specific forms of activities to practice digital skills.

In addition, as older adults may have difficulties to keep their digital skills updated by themselves, learning to use new digital devices or services might be stressful. However, these involuntary stressful situations can be turned into learning opportunities if appropriate support is provided. This support needs to focus not only on learning to use, for example, a certain digital device but also to become aware of and stay interested in the characteristics and functionalities of ever-changing digital tools. This can be achieved if the methods used to support learning are interesting. For example, Blažič and Blažič (Citation2019) reported that by playing games on a touchscreen tablet, the older adults did not learn only the rules of the game itself, but also the rules for how to interact with a digital device. According to Blažič and Blažič (Citation2019), this kind of playful learning facilitates older adults to overcome negative attitudes, beliefs, and fear towards digital devices and services and consequent refusal to use them. ICT teachers and other people supporting the digital skills of older adults are encouraged to stimulate the personal interest of older adults in learning and interacting with digital devices.

Older adults’ reasons to participate in digital skills training are not only related to social, individual, and technical aspects but also to learning possibilities. Personal aspects, such as health, educational level, income, gender, migrant background, (dis)abilities, type and frequency of contact with ICT in the individual biography, and biographic experience of formal and non-formal learning in general influence older adults’ learning and use of digital technology (Ehlers et al. Citation2016). Simultaneously, physical location, timing, and expenses of digital support provision affect the older adults’ opportunities to learn digital skills. The provision of various ways to administer digital support may, therefore, enable older adults in various contexts to reach suitable and personally invigorating digital support.

Our findings show that the learning processes of older people in relation to digital competencies are socio-culturally framed in many ways. Thus, it is clear that the lived experiences of older adults are shaped by physical, psychological, and social realms that differ to some extent from those of other age groups (Findsen and Formosa Citation2011). This is closely related to national policies which relate learning opportunities to the life worlds of older people and thus recognise societal participation and inclusion as both frameworks and goals for equal living conditions (Hermans Citation2022).

A common factor, however, is the need to provide the support in a continuous way. As the digitalisation of society progresses, everyday digital technologies are updated on a regular basis (Cerna et al. Citation2022). Closely related to the topic of social contacts is the topic of social pressure. In an increasingly digitalised society, older people do not want to be ‘left behind’. Social pressure is processed individually, and some of the older people used these courses to be able to cope (Rohner et al. Citation2021). Social aspects illustrate how the various reasons for older adults to participate in digital skills learning are intertwined and simultaneous. It is important to recognise a variety of reasons motivating older adults and to consider different ways of supporting them.

This study employed a multiple-case design, the purpose of which was to investigate and report in-depth case descriptions (Creswell Citation2017). Instead of comparing the case studies (cf. Mills et al. Citation2010), the results of the case studies complemented each other and thus offered rich and diverse perspectives on the causes of older adults’ reasons to participate in digital skills learning. We aimed at building a more comprehensive overview of the research topic across three European countries; Finland representing Nordic countries and Germany and Austria Middle Europe. Thus, the data included versatile views from older adults’ reasons, particularly in highly digitalised countries. However, data from other countries would have provided a more comprehensive understanding of older adult’s reasons to obtain digital literacy skills.

In line with multiple case study designs (Creswell Citation2017), various data collection methods were used in this study. Interviews, for example, were conducted either online (Finland) or face-to-face (Austria), where the latter were implemented both in conjunction with the participatory design workshop activities (Germany B) and after the courses (Austria). Online interviews provided an opportunity to conduct interviews regardless of the physical location of interviewers and interviewees (Salmons Citation2014) which was beneficial economically to avoid long-distance travelling during the COVID-19 pandemic. Simultaneously, online interviews required the use of ICT that may restrict the participation of those older adults in online data collection who lack their own ICT devices. In further studies, phone interviews can be recommended instead of or besides online interviews to support wider participation in research of older adults who live geographically distant from the researchers.

Furthermore, although the case studies provide a wide spectrum of older adults’ experiences, the results are not representative or generalisable directly in other contexts, which is in line with many other qualitative or mixed methods multiple case studies (e.g. Creswell and Poth Citation2018). Still, as described our case studies do differ regarding the mode of collection and analysis as well as the number of respondents. In addition, the societal context in which the respondents live is very heterogeneous. Thus, the comparison across case studies is challenging. This limitation must be acknowledged when interpreting the results. Furthermore, a potential bias might exist, in that only those older adults participate in the study who have at least some degree of interest in digital technologies. Thus, we have no older people included in our studies with no interests or other reasons to not participate in our studies and therefore can also not say anything about them.

The present approach of analysing different case studies of older people’s appropriation of technology has also considered a setting of long-term participatory co-design with older people. There are many analogies to classical courses. This shows that courses should not only include the learning of concrete technology functionalities but should also offer open learning spaces to deal with technology topics that are not (yet) considered relevant in the participants’ current lifeworlds. In this respect, providers of classical learning opportunities can also learn from long-term participatory design projects. These set themselves the task of working intensively and didactically in addition to developing design possibilities, insofar as older adults’ appropriation processes are supported and observed at the same time to co-explore practice-relevant design recommendations for novel technologies. Digital sovereignty thus means not only being able to handle devices but also to participate in discourses regarding future technologies and to be able to assess them for oneself and one’s own everyday world (Baacke Citation1996). This also sheds light on the question of what role participatorily working research institutions can or even should take on in the future to be able to provide social participation in concrete research projects.

Conclusion

This study provided an overview of older adults’ reasons to participate in digital skills training. Reasons were related not only to the older adults’ individual reasons but also to social and external reasons. Simultaneously, the reasons reflected both positive aspects of engaging with digital technology as a hobby and negative aspects, such as social pressure to use digital technology. The study acknowledges the heterogeneity of older adults and their reasons to develop digital skills, necessitating the provision of a variety of learning environments.

Several recommendations for future research as well as the practitioners working with older people can be derived from the study: First, the described heterogeneity of older adults in particular with regard to digital technologies needs to be acknowledged. To support the older people in gaining digital skills no one-size-fits-all approaches should be applied. Second, social contacts often play an important role as ‘door-opener’ for participation in learning activities. Thus, specific emphasis should be put on developing safe and inspiring learning environments that enable such social contacts. This is increasingly important because digitalisation is relevant in all people’s lives, including older adults, even though for some of them an interest in learning and using digital technologies might not come automatically. Third, there is a group of older people that do not participate in digital skill training and is at risk of being digitally excluded from society. More knowledge is needed concerning these so-called ‘hard to reach’ older adults that do not participate in digital skills training. Future studies should explore their reasons for not participation and practitioners should strive to develop learning environments that also attract this group. However, we must also accept that some older people do not want to use digital technologies. Other older adults may not be able to do so, for example, due to neurodegenerative diseases. And still, we must make it possible for them to participate in society. Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic, as an accelerator for digital usage, induced a huge thirst for knowledge among older people when older adults were in effect forced to use computers. The long-term effects of this rapidly developing external reason should be studied in future studies.

Acknowledgements

We kindly thank Kristiina Korjonen-Kuusipuro for participating in data collection in Finland and all the older adults who participated in this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ackermann, T. and Seifert, A., 2021. Older adults’ engagement in senior university lectures and the effect of individual motivations. Frontiers in education, 6, 591481.

- Baacke, D., 1996. Medienkompetenz – Begrifflichkeit und sozialer Wandel. In: A. Rein, ed. Medien-kompetenz als Schlüsselbegriff. Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt, 112–124.

- Blažic, B.J. and Blažic, A.J., 2019. Overcoming the digital divide with a modern approach to learning digital skills for the elderly adults. Education and information technologies, 25 (1), 259–279.

- Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend [Federal Ministry of Economics, Family and Youth, 2020. Achter Altersbericht. Ältere Menschen und Digitalisierung und Stellungnahme der Bundesregierung. Vienna: Republic of Austria. Available from: https://www.achter-altersbericht.de/fileadmin/altersbericht/pdf/aktive_PDF_Altersbericht_DT-Drucksache.pdf

- Brink, R., 2018. A multiple case design for the investigation of information management processes for work-integrated learning. International journal of work-integrated learning, 19 (3), 223–235.

- Cerna, K., et al., 2022. Situated scaffolding for sustainable participatory design: learning online with older adults. Proceedings of the ACM on human-computer interaction, 6 (Group), 1–25.

- Choi, M., Kong, S., and Jung, D., 2012. Computer and internet interventions for loneliness and depression in older adults: a meta-analysis. Healthcare Informatics Research, 18 (3), 191–198. doi:10.4258/hir.2012.18.3.191

- Chopik, W., 2016. The benefits of social technology use among older adults are mediated by reduced loneliness. Cyberpsychology, behavior, and social networking, 19 (9), 551–556.

- Clarke, A., 2012. Grounded theory nach dem postmodern turn. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Clarke, V. and Braun, V., 2014. Thematic analysis. In: T. Teo, ed. Encyclopedia of critical psychology. New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media, 1947–1952.

- Creswell, J.W., 2017. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Creswell, J.W. and Poth, C.N., 2018. Qualitative inquiry and research design. Choosing among five approaches. 4th ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

- Ehlers, A., Bauknecht, J., and Naegele, G., 2016. Abschlussbericht zur Vorstudie “Weiterbildung zur Stärkung digitaler Kompetenz älterer Menschen”. Dortmund: Forschungsgesellschaft für Gerontologie e.V./Institut für Gerontologie an der TUDortmund.

- Ehlers, A., et al., 2020. Digitale Teilhabe und (digitale) Exklusion im Alter. Expertise für den Achten Altersbericht. Berlin: Deutsches Zentrum für Altersfragen. Available from: https://www.achter-altersbericht.de/fileadmin/altersbericht/pdf/Expertisen/Expertise-FFG-Dortmund.pdf

- Eurostat, 2017. Eurostat regional yearbook. 2017 ed. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3217494/8222062/KS-HA-17-001-EN-N.pdf/eaebe7fa-0c80-45af-ab41-0f806c433763?t=1505201643000

- Findsen, B. and Formosa, M., eds., 2016. Introduction. In: International perspectives on older adult education. Research, policies and practice. Lifelong learning book series, Vol. 22. New York: Springer, 1–10.

- Findsen, B. and Formosa, M., 2011. Lifelong learning in later life: A handbook on older adult education. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Forsman, A.K. and Nordmyr, J., 2017. Psychosocial links between Internet use and mental health in later life: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 36 (12), 1471–1518.

- Gallistl, V., et al., 2020. Configuring the older non-user – between research, policy and practice of digital exclusion. Social inclusion, 8 (2), 233–243.

- Garcia, K.R., et al., 2021. Improving the digital skills of older adults in a COVID-19 pandemic environment. Educational gerontology, 47 (5), 196–206.

- Glendenning, F., 2008. What is the future of educational gerontology. Ageing & society, 11, 209–216.

- Hermans, A. 2022. The digital era? Also my era! – Media and information literacy: A key to ensure seniors’ rights to participate in the digital era. Council of Europe. Available from: https://edoc.coe.int/en/internet/11069-the-digital-era-also-my-era-media-and-information-literacy-a-key-to-ensure-seniors-rights-to-participate-in-the-digital-era.html [Accessed 30 August 2022].

- Hornung, D., et al., 2017. Navigating relationships and boundaries: Concerns around ICT-uptake for elderly people. In: Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI'17). New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery, 7057–7069.

- Jenkins, A., and Mostafa, T. 2015. The effects of learning on wellbeing for older adults in England. Ageing & Society, 35 (10), 2053–2070.

- Jokisch, M. and Wahl, H.-W., 2015. Expertise zu Alter und Technik im deutschsprachigen Raum. Erstellt für: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gerontologie und Geriatrie (DGGG). Heidelberg: Unveröffentlichte Expertise.

- Joshi, S.G. and Bratteteig, T. 2016. Designing for prolonged mastery. On involving old people in participatory design. Available from: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/d5dd476c28cc8e2e06ed870d3d400c9e94bc23b0

- Kaše, R., Saksida, T., and Mihelič, K.K., 2019. Skill development in reverse mentoring: Motivational processes of mentors and learners. Human resource management, 58 (1), 57–69.

- Kensing, F. and Blomberg, J., 1998. Participatory design: issues and concerns. Computer supported cooperative work, 7 (3–4), 167–185.

- König, R., Seifert, A., and Doh, M., 2018. Internet use among older Europeans: An analysis based on SHARE data. Universal access in the information society, 17 (3), 621–633.

- Leen, E.A., and Lang, F.R., 2013. Motivation of computer based learning across adulthood. Computers in Human Behavior, 29 (3), 975–983. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.12.025

- Maderer, P. and Skiba, A., 2006. Integrative geragogy: Part 1: Theory and practice of a basic model. Educational gerontology, 32 (2), 125–145.

- Mills, A.J., Durepos, G., and Wiebe, E., 2010. Encyclopedia of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Ministry of Finance, 2017. AUTA-projektin loppuraportti (Final report of AUTA-project), Finland. Available from: https://vm.fi/documents/10623/6581896/AUTA+raportti.pdf/74d0c25e-fa60-43c6-8856-c418faef9085/AUTA+raportti.pdf

- Ministry of Finance, 2018. Digital support and the operating model for digital support. Finland. Available from: https://vm.fi/en/digital-support-and-the-operating-model-for-digital-support

- Muñoz-Rodríguez, J.M., Hernández-Serrano, M.J., and Tabernero, C., 2020. Digital identity levels in older learners: A new focus for sustainable lifelong education and inclusion. Sustainability, 12 (24), 10657.

- Müller, C., et al., 2015. Measures and tools for supporting ICT appropriation by elderly and non tech-savvy persons in a long-term perspective. In: ECSCW 2015: Proceedings of the 14th European Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 19–23 September 2015, Oslo, Norway. Cham: Springer, 263–281.

- Nimrod, G., 2010. Seniors’ online communities: A quantitative content analysis. The gerontologist, 50 (3), 382–392.

- Official Statistics of Finland, 2021. Use of the Internet for following the media and for communication has increased. Available from: https://www.stat.fi/til/sutivi/2020/sutivi_2020_2020-11-10_tie_001_en.html

- Pihlainen, K., Korjonen-Kuusipuro, K., and Kärnä, E., 2021. Perceived benefits from non-formal digital training sessions in later life: views of older adult learners, peer tutors, and teachers. International journal of lifelong education, 40 (2), 155–169.

- Pihlainen, K. and Ng, K., 2022. Hakeutuminen digitaitojen opetukseen ja vertaisohjaukseen (Directing oneselves to digital skills teaching and peer guidance). In: K. Korjonen-Kuusipuro, P. Rasi-Heikkinen, H. Vuojärvi, K. Pihlainen, and E. Kärnä, eds. Ikääntyvät digiyhteiskunnassa. Elinikäisen oppimisen mahdollisuudet (Older adults in digital society. Opportunities of lifelong learning). Helsinki: Gaudeamus.

- Pilcher, K., Martin, W., and Williams, V., 2016. Issues of collaboration, representation, meaning and emotions: utilising participant-led visual diaries to capture the everyday lives of people in mid to later life. International journal of social research methodology, 19 (6), 677–692.

- Quan-Haase, A., Mo, G.Y., and Wellman, B., 2017. Connected seniors: How older adults in East York exchange social support online and offline. Information, communication & society, 20 (7), 967–983.

- Rohner, R., et al., 2021. Learning with and about digital technology in later life: A socio-material perspective. Education sciences, 11 (11), 686.

- Ryan, R.M. and Deci, E.L., 2020. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary educational psychology, 61 (2020), 101860.

- Sayago, S., Forbes, P., and Blat, J., 2013. Older people becoming successful ICT learners over time: Challenges and strategies through an ethnographic lens. Educational gerontology, 39 (7), 527–544.

- Salmons, J., 2014. Qualitative online interviews: Strategies, design, and skills. 2nd ed. London: SAGE.

- Schirmer, W., et al., 2022. Digital skills training for older people: The importance of the ‘lifeworld’. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics, 101, 104695.

- Seifert, A., Hofer, M., and Rössel, J., 2018. Older adults’ perceived sense of social exclusion from the digital world. Educational gerontology, 44 (12), 775–785.

- Seifert, A., Cotten, S.R., and Xie, B., 2021. A double burden of exclusion? Digital and social exclusion of older adults in times of COVID-19. The journals of gerontology: series B, 76 (3), e99–e103.

- Springett, M., Keith, S., and Whitney, G. 2018. Game-based introductory learning: teaching digital skills to older citizens. In: Proceedings of the 32nd International BCS Human Computer Interaction Conference (HCI).

- Tyler, M., de George-Walker, L., and Simic, V., 2020. Motivation matters: Older adults and information communication technologies. Studies in the education of adults, 52 (2), 175–194.

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, 2019. Active ageing index. Analytical Report, ECE/WG.1/33. Available from: https://unece.org/DAM/pau/age/Active_Ageing_Index/ECE-WG-33.pdf

- Withnall, A. 2010. Improving learning in later life. Routledge: London & New York.