ABSTRACT

Students’ perspectives of un/fairness in group work assessment are known to be related to the issues of varied contributions in group work and how to discern each student’s contribution or knowledge from the group’s joint work. Students’ perceptions of un/fairness in group work assessment are important since it relates to their motivation. This study aims to investigate upper secondary students’ perspectives on un/fairness in group work assessment. In the study, 129 upper secondary school students in Sweden between the ages of 15 and 16 years participated. The students were interviewed in 33 focus groups. The interviews were thematically analysed. The study’s findings illustrate how ambition, motivation and friendship relations in groups may vary and cause what students perceive as unfairness. Varied ambitions and motivations among group members also appear to breed situations where group members’ contributions to group work may vary, which also is perceived by students as unfair. Other factors that can contribute to a perception of unfairness are when knowledge levels vary among group members or friendship relations. How un/fairness is perceived also depends on the level at which the assessment is implemented, group or individual level. The greatest experience of unfairness is generated by implementing group assessment.

Introduction

Group work is a well-documented method for teaching and learning that has proven to have a great impact on developing students’ academic knowledge and social skills (Baines, Blatchford, and Kutnick Citation2016; Gillies Citation2016; Johnson and Johnson Citation2004). Despite the positive outcomes of using group work, teachers tend to avoid the method, where one suggested explanation is the complexity and challenge of assessing group work as described by teachers (Forslund Frykedal and Hammar Chiriac Citation2011, Citation2017). Assessing group work is indeed a complex and challenging task for teachers (Forsell et al. Citation2021; Forslund Frykedal and Hammar Chiriac Citation2011; Gedamu and Shewangezaw Citation2020; Ross, Rolheiser, and Hogaboam‐Gray Citation1998); not least ensuring that group work assessment is perceived as fair (Forsell et al. Citation2021; Gedamu and Shewangezaw Citation2020). Group work assessment is a process where students get assessed or graded based on knowledge or contribution developed in collaboration with others in a small group, as we define the concept in this article (Brookhart Citation2013; Forsell, Forslund Frykedal, and Hammar Chiriac Citation2020; Meijer et al. Citation2020).

Teachers describe how they may encounter heated emotions and reactions when students perceive unfair group work assessments, which often seem related to the issue of discerning each student’s knowledge or contribution to the group’s joint work (Forsell et al. Citation2021; Hammar Chiriac and Forslund Frykedal Citation2023). However, group work assessment is not a concept of unison since it can be implemented on both a group level, where all students in the group get the same assessment or grade (group assessment) or an individual level, where each student in a group is assessed or graded individually (individual group work assessment) (Forsell, Forslund Frykedal, and Hammar Chiriac Citation2020, Citation2021; Lotan Citation2003; Meijer et al. Citation2020). From the students’ perspective, perceived unfairness in group work assessment seems related to withholding and unequal contribution in group work (Gedamu and Shewangezaw Citation2019, Citation2020). A recurring standpoint from students’ perspectives is that group assessment is unfair when all group members get the same assessment or grade, despite having contributed unequally (Caple and Bogle Citation2013; Smith and Rogers Citation2014). It is perceived as unfair when students do not get credit for individual contributions or when they must compensate for other students who do not contribute but who all still get the same assessment or grade (Bala Gaur and Gupta Citation2013; Doran et al. Citation2013; Gedamu and Shewangezaw Citation2019, Citation2020; Hassanien Citation2006; Smith and Rogers Citation2014). However, students do accept unequal contributions to some degree if individual efforts are rewarded (Caple and Bogle Citation2013; Doran et al. Citation2013), i.e. when individual group work assessment is applied. Furthermore, research indicates that students’ perceptions of fairness may be raised when they are able to assess each other’s contribution to group work (Jin Citation2012; Poon Citation2011; Shiu et al. Citation2012; Smith and Rogers Citation2014). Some published research focuses on students’ perspectives on group work assessment, even though it is limited (Gedamu and Shewangezaw Citation2019), particularly research highlighting fairness.

Students’ perceptions of un/fairness (i.e. unfairness or fairness) in group work assessment is essential since it relates to students’ motivation (cf. Chory-Assad Citation2002; Holmgren and Bolkan Citation2014). However, fairness in assessment, in general, is a vague concept with several definitions (Rasooli, Zandi, and DeLuca Citation2019) and is described using such terms as unbiased, equity and justice. Furthermore, un/fairness in assessment is also bound to assessment systems and may vary between different nations (Waldow Citation2014). Most previous studies investigating students’ perspectives on un/fairness in group work assessment have focused on higher education. Two studies by Gedamu and Shewangezaw (Citation2019, Citation2020) have investigated students’ perspectives on group work assessment in upper secondary school in general. However, none of these previous studies has focused predominantly on the concept of un/fairness in group work assessment. Furthermore, previous research has primarily investigated students’ perspectives on un/fairness in group work assessment using surveys (Bala Gaur and Gupta Citation2013; Gedamu and Shewangezaw Citation2019; Jin Citation2012; Poon Citation2011; Smith and Rogers Citation2014). Some studies have used mixed methods where both surveys and focus group interviews have been conducted (Caple and Bogle Citation2013; Doran et al. Citation2013; Gedamu and Shewangezaw Citation2020, Hassanien, Citation2008; Shiu et al. Citation2012), but in these studies only two to six focus group interviews with students were conducted. Consequently, there is no research, as far as we know, that has exclusively investigated, in depth, students’ perspectives on un/fairness in group work assessment using focus group interviews. In particular, upper secondary school has been under-represented in previous research on students’ perspectives on group work assessment. Moreover, it is not even clear how to define fairness in assessment in general (Rasooli, Zandi, and DeLuca Citation2019), and due to the complexity of group work assessment, we argue that it is even more unclear how to define fairness in group work assessment. We thereby need more knowledge to understand the mechanisms of fairness in group work assessment, not the least from upper secondary school students’ perspectives on un/fairness in group work assessment.

Based on focus group interviews with students at upper secondary schools in Sweden, this study aims to investigate these students’ perspectives on un/fairness in group work assessment. More precisely, we examine the following research questions:

What prominent aspects of un/fairness in group work assessment do students in upper secondary school address?

Why does unfairness in group work assessment arise, from the perspectives of students in upper secondary school?

Context of the study

As part of a moving international trend, Sweden’s assessment system is criterion referenced (Wikström Citation2009). According to the Swedish curriculum for upper secondary school (Skolverket Citation2011),Footnote1 teachers are expected to base assessment and grading on students’ knowledge based on specific national grading criteria specified for each subject. Even if grades in Sweden are intended to represent students’ knowledge, research illustrates that this is not always the case since teachers tend, to some degree, to weigh effort in grading (Klapp Citation2019; Selghed Citation2004). The Swedish grading scale goes from F to A, where F means fail. E is the lowest grade within the framework of a pass and means that a student has acceptable knowledge. A is the highest grade, meaning they have reached the highest level of knowledge in the grading criteria. In the Swedish school system, grades are of great importance for students since they are the most important selection tool for further education.

The Swedish upper secondary school is a three-year-long education period, in which there are various programmes, ranging from theoretical programmes that are preparatory to further higher studies, to programmes that are vocational and of a more practical nature, although these programmes also include theoretical subjects, such as Swedish language (Skolverket Citation2011).

Theoretical framework

This study’s theoretical framework builds upon concepts and theories from both classroom assessment and social psychology.

Withholding of contribution and effort in groups

Research about group members’ contribution and effort started with Ringelmann’s discovery of how group members’ effort in pulling a rope decreased with the number of group members (Hogg and Vaughan Citation2018; Kravitz and Martin Citation1986). One conclusion from Ringelmann’s study was that group members perceived a loss of motivation when working in larger groups. Further research terms, such as social loafing and free riding, have been used to describe different types of withholding effort, shirking and contribution in group work (Bennett and Naumann Citation2005; Kidwell and Bennett Citation1993). In this study, we choose to use the term ‘withhold effort or contribution’ as synonymous to both the concepts of social loafing and free riding, aligned with the view that both these concepts concern a withholding of contribution (Bennett and Naumann Citation2005; Kidwell and Bennett Citation1993). From a meta-analysis of several studies on social loafing and free riding, Karau and Williams (Citation1993) generated the collective effort model of how withholding effort in groups can be reduced. For instance, the model emphasises the importance that students perceive their contribution and effort as valued and meaningful (Karau and Hart Citation1998; Karau and Wilhau Citation2020). Another crucial aspect concerns group work assessment, since the model emphasises that both the group and each individual’s performance should be assessed to reduce withheld contribution and effort in groups.

Levels and quality in group work assessment

Classroom assessment can be described as a process where teachers collect, interpret, and use evidence of students’ performance to make decisions for instruction and grading (McMillan Citation2018). We argue that group work assessment should follow this process and description since it is just as essential in group work assessment to collect and interpret evidence. However, group work assessment may be considered more complex (Forsell et al. Citation2021; Forslund Frykedal and Hammar Chiriac Citation2011; Gedamu and Shewangezaw Citation2020; Ross, Rolheiser, and Hogaboam‐Gray Citation1998), since it involves specific challenges and complexity. One aspect of group work assessment is that teachers also need to deal with different levels of assessment and sort out issues such as who has contributed to the work or discern each individual’s knowledge from the group (Forsell, Forslund Frykedal, and Hammar Chiriac Citation2020, Citation2021; Lotan Citation2003; Meijer et al. Citation2020). Previous research has illustrated how assessment may have certain effects on group collaboration, depending on what level group members perceive they will get assessed on. Group assessment can foster group collaboration (Deutsch Citation1949; Johnson and Johnson Citation2004; Meijer et al. Citation2020) and group accountability (Johnson and Johnson Citation2004). Individual group work assessment, on the other hand, can foster individual accountability (Karau and Wilhau Citation2020; Meijer et al. Citation2020; Slavin and Madden Citation2021), individual learning, and competition (Orr Citation2010).

There are different aspects of what constitutes quality in classroom assessment, where fairness and validity are two significant aspects (AERA, APA, and NCME (Citation2014); McMillan Citation2018). Just as we argue that group work assessment shares similarities to classroom assessment, we suggest that validity and fairness are basic aspects of quality in group work assessment as well. Previous studies have also concluded that there is a relationship between students’ motivation and perceived fairness (Chory-Assad Citation2002; Holmgren and Bolkan Citation2014). As previously defined, fairness is generally defined as giving students equal opportunities to perform and show knowledge (McMillan Citation2018), and as being unbiased (Rasooli, Zandi, and DeLuca Citation2019; Tierney Citation2013). There are also other descriptions of fairness in assessment, such as sound, equitable, constancy, ethical, feasible and accurate (Tierney Citation2013). These are obviously important aspects of fairness in assessment, yet these definitions do not include the perceived issue of un/fairness in group work assessment aligned with withholding or with unequal contribution (Gedamu and Shewangezaw Citation2019, Citation2020). Fairness and unfairness are two concepts that can be described as two sides of the same coin and are thereby related to each other. In this study, we therefore use ‘un/fairness’ when describing aspects that, to some degree, concern both fairness and unfairness since without unfairness, it is fair and the other way around. Validity in assessment is about the soundness and trustworthiness of the assessment (McMillan Citation2018). Generally, definitions of validity emphasise how validity concerns sound and trustworthy interpretations of the collected evidence from students’ performance (AERA, APA, and NCME Citation2014; Kane and Burns Citation2013; Messick Citation1989). In this study, both fairness and validity are relevant to understand how students’ perspectives of fairness in group work assessment can be understood in terms of quality in assessment. Further the concepts of validity and fairness are to some degree tangled, and AERA, APA, and NCME (Citation2014) conclude that ‘fairness is a fundamental validity issue’ (p. 49).

Method

Participants

In the study, 129 upper secondary school students aged 15–16 years participated. The students were interviewed in 33 focus groups, with three to five students in each group. The focus group interviews were conducted in six classes (A – F) in five upper secondary schools in Sweden. Classes D and E were both represented in the same school (). Among the classes, several programmes in Swedish upper secondary school were represented: social science programme, natural science programme, technology programme and health and social care programme (Skolverket Citation2011).

Table 1. Participants and focus group interviews conducted in the study.

The focus group interviews were conducted as part of a larger research project on group work assessment in which six teachers also participated. The students were recruited to the research project along with these teachers, who were the students’ class teachers. Before the interviews, all the students were informed both orally and in writing about the research project and gave their written consent to participate. The focus group interviews in this study were conducted at the very beginning of the research project.

Data collection

A main point of the focus group interview is to get a variety of perspectives rather than to get the participants to agree on or conclude with one solution or view (Brinkmann and Kvale Citation2014; Vaughn, Shay Schumm, and Sinagub Citation1996). Another advantage of interviewing groups is that it is an efficient method for collecting data from many participants at the same time (Frey and Fontana Citation1991).

The interviews were semi-structured and prepared by constructing an interview guide (Brinkmann and Kvale Citation2014; Vaughn, Shay Schumm, and Sinagub Citation1996). In this study, the focus group interviews focused on students’ previous experiences and perspectives on group work assessment. However, the analysis, based on the purpose of the study, focused specifically on students’ experience of un/fairness. Thereby the questions concerned un/fairness in group work assessment were in particular focus, such as: ‘Do you have any experience of unfair assessment in group work?’, ‘What made the assessment unfair?’ and ‘What is a fair assessment?’. Accordingly, not all questions in the interviews focused on un/fairness. Un/fairness was a recurring topic the students brought up when talking about other aspects of group work assessment. These sections in the interviews were also included as a basis for the analysis. Altogether the sample size of data was perceived to hold enough with information power (Braun and Clarke Citation2021, Citation2022) to analyse students’ perspectives on un/fairness in group work assessment. All focus group interviews were recorded and conducted in group rooms at the students’ schools. The focus group interviews were transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

Analysing the interviews was guided by the phases and guidelines described by Braun and Clarke (Citation2022), using a reflexive thematic analysis (TA) with an inductive approach. First, the process began with reading and familiarising ourselves with the transcripts of the interviews to get an overview of the dataset. In this phase the study’s aim was framed since it became evident that one prominent topic from students’ perspective concerned aspects of un/fairness. The process of TA continued thereby with coding all the transcripts guided by the aim to study students’ perspectives on un/fairness in group work assessment. The coding was conducted using the software MAXQDA12, which lets the user organise, code, and analyse qualitative data. Using MAXQDA12, all transcripts were imported into the software and systemically coded by analysing them from the beginning to the end. All the relevant excerpts in the interviews related to students’ perspectives on group work assessment were labelled with a code, summarising the excerpts. The codes were initially more semantic, which captured more explicit meanings; further coding processes implied more analytical latent codes that capture the essence of what is said (Braun and Clarke Citation2022). Consequently, part of the analysis started along with the coding process. When the transcripts were systematically coded, a phase of organising and sorting the codes began by exporting all the codes from MAXQDA12 into Excel. Further, using Excel, the codes were clustered in groups that shared meaning. For example, codes concerning unfairness in one group or codes concerning students’ perspectives on misleading assessments in another group. Groups of codes that shared meaning were further clustered into initial themes (Braun and Clarke Citation2022). Some examples of initial themes are ‘group composition’ or ‘expectations of assessment’. The analysis proceeded with a phase of further organising, reviewing, and refining the initial themes. Out from this process three main themes concerning un/fairness in group work assessment were created. In the process, it also became more apparent that the concepts of fairness and unfairness are two sides of the same coin, making them both equally relevant in the analysis. Subthemes were also created through a process of reviewing the excerpts corresponding to the codes. This process can be described as parallel to refining, defining, and naming themes and subthemes. Through the process of generating the themes, the ambition was to systematically go deeper into the transcript to create themes supported by rich data that could provide complexity, duality, and nuance to the themes (Braun and Clarke Citation2022). After the process of generating the themes, the TA proceeded by writing up the result, which can also be described as a process of further developing, deepening, and reviewing the themes.

Ethics

Throughout this study, both the ethical principles of the (American Psychological Association Citation2017) and the guidelines from the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet Citation2017) were applied. The study was approved by the Regional Research and Ethics Committee at Linköping University, Sweden (Dnr 2013/401–31, Dnr 2014/134–32 and Dnr 2016/209–32). All the participants were informed both orally and in writing about the study and agreed to participate by signing a written informed consent form. All names were changed to ensure confidentiality.

Results

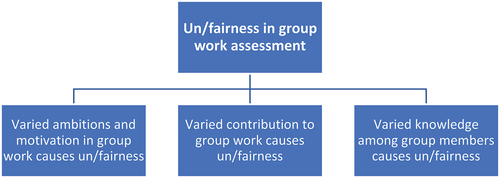

The thematic analysis of upper secondary students’ perspectives on un/fairness generated three themes (): (a) Varied ambition and motivation in the group causes un/fairness, (b) Varied contributions to group work causes un/fairness, and (c) Varied knowledge among group members causes un/fairness. Each theme highlights different aspects of un/fairness from students’ perspectives on group work assessment. Furthermore, the themes also relate to each other, as illustrated in this result section.

Figure 1. The thematic map of the overarching theme, followed by themes created in the thematic analysis.

Varied ambition and motivation in group work causes un/fairness

The first theme of students’ perspective on un/fairness in group work assessment revolves around group compositions, which from the student’s perspective was generally decided by teachers. Group composition generates different opportunities for students to perform in a group and, thereby, different conditions to demonstrate their knowledge. This will also impact the assessment since the group composition affects students’ opportunities to attain a desired assessment or grade. In particular, ambitious students find it unfair when they are placed in groups with less motivated or less ambitious peers. This discrepancy in ambition and motivation generates less favourable opportunities for ambitious students and is also perceived as a source of unfairness in group work assessment. Ambitious students describe that they need to work harder to compensate for the lack of motivation in their group. Accordingly, the unequal distribution of effort and contribution in the group due to different ambitions is perceived as unfair. One of the students in the focus group interviews described the unfairness as follows: ‘If you have someone unmotivated and someone motivated in the group, it [the assessment] will be unfair for the motivated.’ (Student 2, Group D1). Accordingly, students may have different objectives and ambitions regarding striving for knowledge, assessment, and grades. In group work, the group composition may create situations where more ambitious students who aim for a higher grade also need to work more to compensate for the students with lower ambitions. This is also about unfairness from the students’ perspective:

It is important to get a fair grade. If you know that you are able to, that you could get an A but because of someone else, what they have done or what they have written, the grade is lowered, then it feels unfair, because you know that you can do better. (Student 1, Group D1)

Consequently, in this situation, due to the opportunity the group composition offers, this student perceives limited chances to demonstrate their individual knowledge. Part of this situation is also that students get group assessments, which in this scenario causes the more ambitious students to work harder to raise the whole group’s performance. Uneven group compositions regarding ambition especially put a lot of responsibility on the ambitious students. When group assessment is implemented, students with higher ambitions than the rest of the group must make sure that the whole group succeeds in getting the assessment or grade that he or she is aiming for. The students describe group assessment as problematic in this sense, but the perspectives and attitudes towards group assessment are also related to group composition. The students draw a difference between being in a group where everyone contributes and works hard, and being in a group where one or a few group members contribute and work hard.

It depends on which group you end up in. If you know that your group is good, then you know that you will get a good assessment. Usually, they assess according to the group’s wholeness, and if the group works really well together, you know that the assessment will be good. On the other hand, if you work with a group that is a bit skewed, not everyone works, you know that the assessment will not be, that is, the grade or the assessment, will not be what you want. (Student 2, Group C1)

The student in the excerpt above finds group assessment to be fair just as long the group can perform and get the desired assessment. Perceived unfairness with group composition arises first when the group’s collaboration does not work, and group members contribute unequally.

A situation that may arise due to a group composition where group members have different ambitions is that students with high ambitions describe how they must control the group’s work and steer it in the desired direction. A consequence of this is that other group members’ feelings might get hurt.

Sometimes, people take the initiative and choose to do almost everything themselves because they want it to be good, then the atmosphere gets a little bad in the group, if that person acts like ‘No, but you are not as smart, you cannot do this’. (Student 1, Group D1)

Working in a group also entails social aspects and dealing with other group members’ emotions. But students also need to deal with their own emotions, such as not feeling adequate or, for some, highly ambitious students who describe that they may get nervous before group work about who they get to work with. To solve this situation with different ambitions and, from the students’ perspective, raise fairness, the students suggest that it would be better if they got to choose who to work with. A suggestion is that teachers group students based on their ambitions.

I think that for the assessment to be fair, you can either choose a group or the teacher divides the class into groups that they know works because then you can assess more on the whole group’s work if you know that this group works well, and everyone helps equally. (Student 5, Group D1)

On the other hand, as another student said: ‘Of course, the teachers feel that it is really horrible to put the bad students together.’ (Student 1, Group A1). Grouping low-performing students with other low-performing students may raise another ethical question of fairness: What opportunities do the low performing students get to learn and perform and get a desired assessment or grade?

Evidently, the students find themselves depending on the group’s composition to be able to perform. But how do the students accept this perceived unfair situation? Part of this issue is friendship relations, making it hard for students to draw the teacher’s attention to this unfair situation. Some students describe how they do not want to ‘snitch’ on their friends or ‘throw someone under the bus’, because that would cause a bad atmosphere in the group. One student summed it up: ‘It is an honour thing, not snitching on people.’ (Student 1, Group A6). Accordingly, keeping friendship relations intact is more important than fairness.

Student 1: There is nothing you can do.

Student 2: Should you have to go to the teacher and sell out your classmates and say: ‘no, this person does not work.’ It doesn’t feel so fun.

Student 1: In many cases, it is your friends.

(Group A1)

From the students’ perspective, the choice is between fairness and keeping good relations with their classmates. This is important and can also be understood in relation to the fact that Swedish students generally spend three years in upper secondary school in the same class. Keeping good relations with classmates during these years seems to be just as important as the grades. As one of the students in the study put it: ‘But then you must weigh up what is most important, your own grade or that you are going to continue to be friends with these people for a few more years.’ (Student 1, Group A6).

To summarise the theme, students experience unfairness when group members have different ambitions and motivations to work in the group. Then, it becomes easy for more ambitious students to take over and do more work. A consequence of this can be that it hurts the feelings of the other students. Another result can be that ambitious students become nervous about group work because they are afraid of not getting the grades for which they are aiming. One way to solve this would be to form groups where individuals can work at their level of ambition and/or ability, and know that the others in the group do the same. Friendships, however, do not make this a fair proposition. A dilemma arises for ambitious students: friendship or high grades?

Varied contributions in group work cause un/fairness

As seen in the previous theme, varied levels of ambition and motivation among group members can breed a situation where group members’ contributions to group work may vary. The second theme of un/fairness from students’ perspectives on group work assessment highlights the issue that group members may individually contribute differently to group work, which indeed is a prominent and recurring issue.

From the students’ viewpoints, unfairness related to varied contributions in group work is tangled with group assessment since it is perceived as unfair when all get the same assessment despite perceived unequal contributions to the group’s work. The students define contribution as effort and hard work in the collective tasks. As one student stated in a focus group interview: It is not fair for someone in the group who has worked hard (…) and then the one who has worked hard gets the same bad grade as the one who hasn’t worked that hard, so it is not fair. (Student 4, Group A2) (see ). As a further example, one student shared the following experience:

I was doing an assignment on C-level and one of our group skipped two or three lessons and still got an E. I don’t think that is really fair, because he had not been there. But he was just told ‘This is what you’re going to talk about at the presentation’. And then he performed it on an E, then got an E. I don’t think that is really fair when we have done the work and he just presents it. (Student 3, Group D5)

Part of the issue students describe as unfair with varied contributions in group work is indeed the implementation of group assessment; even though students often find themselves assessed as a group, they all receive the same assessment/grade described by the students as a mean value of all the group members’ performance. According to the students, group assessment facilitates varied contributions or efforts. From the students’ perspective, the root of this issue of unfairness lies in teachers’ lack of insight into individual contributions to group work. This perceived unfair situation also impacts students’ attitudes towards group work, generating negative feelings, frustration, and irritation when all group members receive the same assessment or grade, even if they have not contributed equally. As one student says:

Every other time you get disappointed, you think; what the hell, they did not do anything but still got the same as me. So, it would be a shame to say otherwise. You sit here and think you have done a great job and then someone who has not done anything comes along like, ‘Well, what did you get?’ I say I got a B and they say: ‘Yes, me too’. And I am like, ‘But you did not do anything.’ ‘No, but I still got the same grade.’ That makes you angry. (Student 2, Group B4)

Part of the issue with unfairness related to varied contributions to the group process is that students describe how it is difficult for teachers to observe the group’s process during ongoing group work, as the work often takes place in locations other than the classroom, such as group rooms or the school’s library. Instead of moving around and observing the students during group work, students describe how some teachers take the opportunity to work with their computers instead, while students work in groups.

Student: He does not even want to know who has written what.

Student: He does not know that.

Student: You could make notes in the written work identifying, for instance, that this person has written that part and this other person has written that part; it would be really easy, but he does not want to know who has written what.

(Group B3)Footnote2

Some students concluded that certain teachers were not interested or did not care about who contributed to the group work. Teachers who do not acknowledge each student’s contribution in group work assessment contribute to students’ perspective of un/fairness in group work assessment.

Students suggest that fairness could be increased by assessing and acknowledging students’ contributions to group work. One perspective on raising fairness is identifying and penalising group members who withhold contributions. According to students, a fairer group work assessment would involve lowering the grades of those students who withhold contributions to group work. As one student suggests: ‘It would be pretty fair if those who do not care get a lower grade, then and the ones who work get a higher grade.’ (Student 3, Group E4).

Some students describe how some teachers actively participate during group work, walking around, observing, asking questions, and taking notes. This is perceived as positive since each student’s contribution is acknowledged. The students’ request for increasing fairness through recognising individual contributions during group work is also related to individual group work assessment. Students in one focus group interview argued:

Interviewer: Okay, but what do you think a fair assessment would be then?

(…) Student 3: I guess it is somehow when you can assess each person individually (…), that you can easily see who has done what. Mm, maybe check like if we are working on the lesson, for example, we can check a little bit what each person has done, just check that everyone has done something.

(Group D6)

To gain more insight into the group’s processes, one explicit suggestion is to interact with students during group work and discuss each student’s contribution. The objective of interaction, in this case, is to gain a better understanding of who did what. This suggestion is also about acknowledging each student’s contribution, thereby increasing fairness.

To summarise the theme, students also experience unfairness when all students receive the group assessment grade, regardless of how much each individual has contributed to the group work. One reason for perceived unfairness is that the teacher does not have enough insight into each individual’s contribution to the work. It is difficult for teachers to observe group work because the groups are often spread out in different rooms. The students suggest that individual contributions to the group’s work should be assessed so that those who contribute will receive higher grades. This could be done by the teacher walking around, observing and talking to the group about each group member’s contribution, thereby increasing fairness.

Varied knowledge among group members causes un/fairness

A third theme of un/fairness in group work assessment from the students’ perspective focuses on the assessment of knowledge. This aspect of un/fairness relates to the students’ viewpoints that fairness in group work assessment is about getting an assessment or a grade that corresponds to individual knowledge. Part of this issue with un/fairness is group assessment, since it is perceived as unfair when group members with different levels of knowledge and who perform at different levels still get the same assessment or grade.

Everyone gets more or less the same assessment, or the same grade in a group project. While maybe everyone in the group is not on the same level, maybe there are some in the group who have done more work because they are more knowledgeable. (Student 1, Group A4)

From the students’ perspective, a group assessment of knowledge is perceived as a false assessment because it fails to reflect each group member’s knowledge. The students describe how, in fact, the knowledge among group members may differ, yet everyone receives the same assessment or grade. One student in the focus group interviews said: ‘One knows everything and three know nothing. In a way, it is a false grade.’ (Student 3, Group C6). The perspective on how this knowledge difference generates false grades is aligned with the Swedish curriculum for upper secondary school, which stipulates that grades should reflect each individual student’s knowledge. In the situation where students get group grades, this is not aligned with the curriculum but also described as unfair since less able students may take advantage of or obtain credit for other students who have knowledge. As one of the students in the study stated: ‘It is unfair when someone parasites on someone else’s grade.’ (Student 2, Group A1). Part of students’ perspectives of un/fairness in group work assessment is, accordingly, about when other students take advantage or credit for other students’ knowledge. If students get assessments or grades based on their actual individual knowledge, they instead perceive that fairness is increased. Giving individual group work assessments is about acknowledging each student’s knowledge and making each student accountable for the knowledge learnt from group work. In the focus group interviews, students share their experiences and suggest ways in which teachers could assess their knowledge individually in group work, thereby increasing perceived fairness. One suggestion the students make is to consider group work as a method for collaborative learning, followed by individual tests. The advantage of doing so would be, as one student said: ‘you can see what knowledge each student has, and if they have used this group or group work as a tool to prepare for a test.’ (Student 1, Group E2).

Another suggested method for conducting individual group work assessments of knowledge, as requested and experienced by the students, is for the teacher to conduct a conversation or questioning, alone or with other students. The purpose of this conversation is to assess, through questioning, what each student has learnt and what knowledge has been developed through group work. For example, one student describes an experience where a group work project was followed by a seminar: ‘That is, the group talks about the work they have done with the teacher, so then they also see who knows what.’ (Student 2, Group B1). The students further describe an alternative method of using a seminar after group work. In this method, the students describe how they presented the entire group’s work to new cross-groups after the initial group work. One student stated:

We did a group project where we produced a piece of written work and handed it in. But then after that we were mixed with people from different groups, and we sat and talked. Then you were alone and away from your group, so you really had the chance to show what you knew. (Student 4, Group A4)

Cross-group assessment was described as an opportunity for each student to demonstrate their knowledge. By enabling individual group work assessment of knowledge, the method also aligns with students’ perception of un/fairness.

Another suggestion from the students for individual group work assessment of knowledge is that teachers track each student’s part in the written piece of work produced within a group. This can be done using digital documents or by allowing the students to mark and identify in the written piece of work, who wrote what. This approach allows the teacher to assess each group member’s performance and knowledge.

To summarise the theme, students believe that fair assessment is about each individual being assessed based on their knowledge. If group members receive a group assessment, it will be unfair because the knowledge varies between different students. Furthermore, the students believe that individual group work assessment makes the individual more responsible for developing their knowledge and work, and getting grades that relate to that knowledge. It also makes the assessment fairer. The students suggest the following methods/approaches to make group assessments fairer: (a) group work followed by individual piece of written work, (b) conversations and questions by the teacher in each group, (c) cross-group presentation, and (d) in a written piece of work, each student can mark what part of the text they wrote, which allows the teacher to assess each individual’s knowledge.

Discussion

This study’s aim was to investigate upper secondary students’ perspective on un/fairness in group work assessment. The findings from this study support but also expand the sparse previous research on un/fairness in group work assessment (Forsell et al. Citation2021; Gedamu and Shewangezaw Citation2020).

As concluded in the introduction, fairness in assessment is generally a vague concept described in terms such as unbiased, equity and justice (Rasooli, Zandi, and DeLuca Citation2019). The findings also illustrate that the upper secondary students talked about unfairness and fairness as two sides of the same coin, even if situations of unfairness were more apparent. Although unfairness was stressed more often by the students, which may indicate that they often aligned group assessment with unfairness, the students’ statements were often followed by justifications on how to make group work assessment fairer. Furthermore, this study’s findings illustrate how fairness in group work assessment differs from fairness in assessment generally. A substantial difference when describing un/fairness in group work assessment is how the students brought up different group processes such as contribution to the group work, motivation among group members, and friendship relations. These group processes are not part of the definitions of fairness in assessment. Previous research of un/fairness in group work assessment (Caple and Bogle Citation2013; Gedamu and Shewangezaw Citation2019, Citation2020; Smith and Rogers Citation2014) has illustrated that students’ perspectives are related to the issue of varied or withheld contributions to group work, primarily when the group assessment is implemented. It is perceived as unfair when all students are given the same assessment or grade, even though each group member has contributed differently to the group’s work. One suggestion from students to raise fairness is to let teachers observe and acknowledge each student’s contribution to the group work. However, this may open a new dilemma for teachers, as students may request that individual contributions be considered in group work assessments. This may lower the validity of group work assessments since it does not comply with the curriculum requirements (Skolverket Citation2011). Weighting in contribution in assessment does not align with recommendations for group work assessment, where the focus should be on students’ knowledge and not contribution (Brookhart Citation2013).

Furthermore, this study’s findings expand the knowledge about un/fairness in group work assessment with two additional aspects that have not noticeably been pointed out in previous research (Caple and Bogle Citation2013; Gedamu and Shewangezaw Citation2019, Citation2020; Smith and Rogers Citation2014). These aspects concern varied levels of ambition and motivation among group members, and varied knowledge among group members. The first aspect suggests that the two external factors of ambition and motivation affect the chances for each group member to get an assessment or grade that they strive for. Ambitious and motivated students perceive it as unfair to be working with group members who do not perform at the same level or share the same ambition. Students believe it would be fairer if they got to choose who to work with. However, the suggestion raises an ethical issue for the teachers, since this solution may benefit ambitious and motivated students but may not be the best solution for students with low ambition and motivation (Lotan Citation2003). Another issue with letting students choose their groups is that friendship relations would likely affect the choice of who to work with. According to this study’s findings, friendship relations may make it difficult for students to raise issues of unfairness. As one of the students in the result says: ‘You do not want to throw someone under the bus’. Friendship relations are strong and valuable for the students and seem more important than unfair assessments or grades. This also gives answers why ambitious students do not want to acknowledge their teachers when some group members withhold their efforts (cf. Hammar Chiriac and Granström Citation2012)

The second additional aspect of un/fairness in group work assessment, varied knowledge among group members, highlights that even though the contribution is essential, it is not only about who has done what during group work, but also about who knows what. Students perceive it as unfair that all group members get the same assessment when it is evident that not all students in the group have obtained the same knowledge when the group work is complete. Accordingly, this aspect also concerns validity since it becomes uncertain whose knowledge the assessment corresponds to (cf. AERA, APA, and NCME Citation2014; Kane and Burns Citation2013; Messick Citation1989). When implementing group assessment, the teacher consequently assumes that all group members share the same knowledge, which is a dubious assumption since previous literature points out that students who work in groups most likely have different knowledge (Strijbos Citation2011, Citation2016; Webb Citation1997). And from the students’ perspective, the grade is ‘false’. Thus, a key element in understanding students’ perspectives on un/fairness in group work assessment is how the notion of unfairness is intertwined with group assessment. It is perceived as unfair to give all members in a group the same assessment or grade when ambition, motivation, contribution and knowledge may vary within groups. However, the suggestions from the students’ perspective to make group work assessment fairer is to discern each group member’s individual contribution or knowledge. This would also have a positive effect on the validity of the assessment since each student’s individual knowledge would correspond to each student’s assessment (cf. AERA, APA, and NCME (Citation2014); Kane and Burns Citation2013; Messick Citation1989).

Obviously, this study has focused on summative group work assessment, and less on students’ perspectives of un/fairness in formative group work assessment (McMillan Citation2018). Interestingly, students raised no issues concerning un/fairness in formative assessment in the focus group interviews, which raises the question of why. One interpretation may be that students generally tend to focus more on summative assessments. Another explanation might be that formative group work assessment may be perceived by the students as less problematic. A teacher may give students feedback during group work, which can be used by students both on an individual and a group level. From the students’ perspective, this is unlikely to be an issue that concerns un/fairness.

To sum up, the results of this study suggest that the definition of what un/fairness in group work assessment includes may be expanded from what we know based on previous research (Caple and Bogle Citation2013; Gedamu and Shewangezaw Citation2019, Citation2020; Smith and Rogers Citation2014). As fairness in classroom assessment is defined as giving equal opportunities to demonstrate knowledge (McMillan Citation2018) or being unbiased (Rasooli, Zandi, and DeLuca Citation2019; Tierney Citation2013), fairness in group work assessment is also about discerning and assessing each individual’s contribution and knowledge. The definition of un/fairness in group work assessment should include how each individual’s contribution can be assessed and how individual knowledge can be addressed. Also, the idea of giving everyone equal opportunities can be included based on the results that show the importance of the group’s composition, where ambition and motivation are decisive for opportunities to perform in group work. Thereby this study adds knowledge about how group processes such as contribution to the group work, motivation among group members, and friendship relations are important aspects of understanding un/fairness in group work assessment. This also implies that definitions of fairness in group work assessment are even more complex to make than in assessment in general. Furthermore, this study’s focus on upper secondary students’ perspective on un/fairness in group work assessment using focus groups interviews also contributes with new knowledge filling some gaps in the research field on group work assessment.

Limitations

As in all research, this study has some limitations worth discussing. Using focus group interviews enabled over 100 students to voice their views on fairness and unfairness in group work assessments. One can ask which students’ perspectives are represented in the study. It seems fairness and unfairness are primarily concerns for the more ambitious students, and there is thereby a risk that less ambitious students’ views are underrepresented. It is also possible that the less ambitious students tacitly benefited from some of the unfairness pointed out by the ambitious students and therefore were more quiet about unfairness in the focus group interviews. Group processes during the focus group interviews may also have affected the answers, and possibly left less room for dissenting opinions.

As in all studies that explore perspectives, there is the question of ecological validity, since what humans say they do is not always what they do. This study gives a relatively robust view of upper secondary school students’ perspectives on un/fairness in group work assessment. Still, it does not say anything about their actions in real situations. For instance, when students describe varied contributions in group work, is this a matter of a perspective that might get another or a nuanced perspective from another group member, or was the contribution observed in an actual situation?

Another limitation to discuss is the context of how national assessment systems differ (Waldow Citation2014). The results of this study should thereby be understood from the angle of the Swedish curriculum. However, since the trend is moving towards criterion-referenced assessment systems (Wikström Citation2009), this study’s results are likely relevant in nations other than Sweden. Furthermore, in Sweden teachers are instructed not to assess students’ effort and social skills but only knowledge. A consequence of this is that this study therefore focuses less on students’ development of social skills. Another limitation is the particular focus on students’ perspectives which thereby misses the teachers’ perspectives, making the latter a suggestion for future research.

Implications

With the expanded knowledge of what students in upper secondary school perceive as un/fair in group work assessment, this study offers some implications for teachers’ practice. Since it is essential for students to get each contribution in group work acknowledged in order to attain fairness in group work assessment, it may be a good idea to follow group work by observing and interacting with students. However, assessing contribution is another matter, and how the contribution is an objective for assessment may differ in different school systems. In this study’s context, teachers are not supposed to weigh contributions in grades, so it is also important to consider validity in assessment. Validity is particularly important to consider, since grades from upper secondary school are high stakes in Sweden due to their importance for students’ future education, it is fair to assume that group work assessment matters, since it is part of all the evidence on which teachers base their grades.

Another implication concerns the choice between giving group assessments or group grades, or individual assessments or grades. Considering fairness from students’ perspectives, and validity, assessing individual knowledge is preferable. Individual group work assessment will also likely affect group collaboration since individual accountability may reduce effort being withheld in group work (Karau and Wilhau Citation2020; Meijer et al. Citation2020; Slavin and Madden Citation2021). Increasing individual accountability and making each student responsible for their contribution may also even out the difference in students’ ambitions. If all students contribute and put effort into their work, it will likely give more equal opportunities for students to demonstrate their knowledge and increase their sense of fairness. In this sense, this study also offers further knowledge of how to put together groups. Students themselves request to work with others who share the same goals and ambitions. However, teachers may be careful with emphasising individual accountability too strongly since it also can have consequences for the group’s joint learning process as it may hinder collaboration in group work.

Conclusions

By elucidating upper secondary students’ perspective on un/fairness in group work assessment, this study contributes new information, filling some gaps with new knowledge to the research field on group work assessment. This study was the first study focusing on upper secondary students’ perspective on un/fairness in group work assessment using a qualitative research design, collecting data through focus group interviews and making the students’ voices heard. The findings highlight that the upper secondary students talked about unfairness and fairness as two sides of the same coin, i.e. one cannot exist without the other. However, unfairness was stressed more by the students, and the students’ statements were often followed by justifications on how to make group work assessment fairer. The study confirms previous research regarding the fact that variation in students’ contributions to group work is of great importance for perceived un/fairness in group work assessment. In contrast to previous research, other types of variation also emerge as important, such as students’ variation in ambition, motivation, knowledge, and friendship relations, all affecting students’ perception of un/fairness in group work assessment. This study’s findings thereby broaden the definition of un/fairness in group work assessment to also include varied motivation and varied knowledge among group members. However, the most important cause of perceived unfairness, according to the students, depends on the level at which the assessment is implemented, group or individual level. The greatest experience of un/fairness is generated by implementing group assessment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Johan Forsell

Johan Forsell MSS, Doctoral student in Education at the Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning at Linköping University, Sweden. His research interests lie within pedagogy and social psychology. His dissertation project focuses on group work assessment, studying students’ perspectives on group work assessment and teachers’ perspectives and practice of group work assessment.

Karin Forslund Frykedal

Karin Forslund Frykedal PhD, Professor of Education at the Department of Social and Behavioural Studies, University West, Sweden. Her scientific activity lies within educational research focusing on leadership, group processes and learning in educational groups. Her current research projects concern group work and group work assessment in educational contexts and pre-service teachers’ professional learning during their teacher education.

Per Andersson

Per Andersson PhD, Professor of Education at the Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning at Linköping University, Sweden. His research interests focus on educational assessment and particularly recognition of prior learning, professional development among teachers in vocational and adult education, and marketisation of adult education.

Eva Hammar Chiriac

Eva Hammar Chiriac PhD, Professor of Psychology at the Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning, Linköping University, Sweden. Her scientific activity lies within the social psychological research field with a strong focus on group research, mainly connected to groups, group processes, learning and education. Her current research project concerns group work assessment, school climate and relations in schools, and problem-based learning.

Notes

1. Since the time of data collection conducted during the years of 2017–2018 for this study, there have been updates in the curriculum, but the principles that grades should correspond to knowledge expressed in criteria is the same.

2. In this particular focus group interview, it is hard to tell which student is speaking and therefore the students in the quote are not numbered.

References

- AERA, APA, and NCME. 2014. Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association.

- American Psychological Association. 2017. Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Baines, E., P. Blatchford, and P. Kutnick. 2016. “Promoting Effective Group Work Int Theprimary Classroom.” In A Handbook for Teachers and Practioners, Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315730363.

- Bala Gaur, S., and T. Gupta. 2013. “Is Group Assessment a Bane or Boon in Higher Education? A Students–Teacher Perspective.” International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education 6 (3): 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/17543266.2013.795610.

- Bennett, N., & S. E. Naumann. 2005. “Withholding Effort at Work: Understanding Andpreventing Shirking, Job Neglect, Social Loafing, and Free Riding.” In Managing Organizational Deviance, edited by R. E. Kidwell & C. L. Martin, 113–130. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Braun, V., & V. Clarke. 2021. “To Saturate or Not to Saturate? Questioning Data Saturation As a Useful Concept for Thematic Analysis and Sample-size Rationales.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health 13 (2): 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2022. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Brinkmann, S., and S. Kvale. 2014. Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Brookhart, S. M. 2013. Grading and Group Work. Washington, DC: ASCD Arias.

- Caple, H., and M. Bogle. 2013. “Making Group Assessment Transparent: What Wikis Can Contribute to Collaborative Projects.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 38 (2): 198–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2011.618879.

- Chory-Assad, R. M. 2002. “Classroom Justice: Perceptions of Fairness As a Predictor of Student Motivation, Learning, and Aggression.” Communication Quarterly 50 (1): 58–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463370209385646.

- Deutsch, M. 1949. “An Experimental Study of the Effects of Co-Operation and Competition Upon Group Process.” Human Relations 2 (3): 199–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872674900200301.

- Doran, K. M., K. T. Ragins, C. P. Gross, and S. Zerger. 2013. “Medical Respite Programs for Homeless Patients: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 24 (2): 499–524. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2013.0053.

- Forsell, J., K. Forslund Frykedal, and E. Hammar Chiriac. 2020. “Group Work Assessment: Assessing Social Skills at Group Level.” Small Group Research 51 (1): 87–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496419878269.

- Forsell, J., K. Forslund Frykedal, E. Hammar Chiriac, and S. K. F. Hui. 2021. “Teachers’ Perceived Challenges in Group Work Assessment.” Cogent Education 8 (1). https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2021.1886474.

- Forslund Frykedal, K., and E. Hammar Chiriac. 2011. “Assessment of Students’ Learning When Working in Groups.” Educational Research 53 (3): 331–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2011.598661.

- Forslund Frykedal, K., and E. Hammar Chiriac. 2017. “To Make the Unknown Known: Assessment in Group Work Among Students.” Journal of Education Research 10 (2): 149–162.

- Frey, J., and A. Fontana. 1991. “The Group Interview in Social Research.” The Social Science Journal 28 (2): 175–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/0362-3319(91)90003-M.

- Gedamu, A. D., and G. L. Shewangezaw. 2019. “Selected Secondary School students’ Perspective of their Teachers’Group Work Assessment Practices.” Ethiopian Journal of Business and Social Science 2 (2): 38–56. https://doi.org/10.59122/73402tY.

- Gedamu, A. D., and G. L. Shewangezaw. 2020. “Teachers’ Beliefs and Practices of Cooperative Group Work Assessment: Selected Secondary School Teachers in Focus.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 45 (11): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.202v45n11.1.

- Gillies, R. 2016. “Cooperative Learning. Review of Research and Practice.” Australian Journal of Educationa L Research 41 (3): 39–54. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2016v41n3.3.

- Hammar Chiriac, E., and K. Forslund Frykedal. 2023. “Individual Group Work Assessment in Cooperative Learning: Possibilities and Challenges.” In Contemporary Global Perspectives on Cooperative Learning Applications Across Educational Contexts, edited by R. Gillies, N. A. Davidson, and B. Mills, 94–108. New York: Routledge.

- Hammar Chiriac, E., and K. Granström. 2012. “Teachers’ Leadership and students’ Experience of Group Work.” Teachers & Teaching 18 (3): 345–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2012.629842.

- Hassanien, A. 2006. “Student Experience of Group Work and Group Assessment in Higher Education.” Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism 6 (1): 17–39. https://doi.org/10.1300/J172v06n01_02.

- Hogg, M., and G. Vaughan. 2018. Social psychology. 8th ed. New York: Pearson.

- Holmgren, J. L., and S. Bolkan. 2014. “Instructor Responses to Rhetorical Dissent: Student Perceptions of Justice and Classroom Outcomes.” Communication Education 63 (1): 17–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2013.833644.

- Jin, X. 2012. “A Comparative Study of Effectiveness of Peer Assessment of individuals’ Contributions to Group Projects in Undergraduate Construction Management Core Units.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 37 (5): 577–589. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2011.557147.

- Johnson, D. W., and R. T. Johnson. 2004. Assessing Students in Groups. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press.

- Kane, M., and M. Burns. 2013. “The Argument-Based Approach to Validation.” School Psychology Review 42 (4): 448–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2013.12087465.

- Karau, S. J., and J. W. Hart. 1998. “Group Cohesiveness and Social Loafing: Effects of a Social Interaction Manipulation on Individual Motivation within Groups.” Group Dynamics: Theory, Research & Practice 2 (3): 185–191. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2699.2.3.185.

- Karau, S. J., and A. J. Wilhau. 2020. “Social Loafing and Motivation Gains in Groups: An Integrative Review.” In Individual Motivation within Groups: Social Loafing and Motivation Gains in Work, Academic, and Sports Teams, edited by S. J. Karau, 3–51. Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-849867-5.00001-X.

- Karau, S. J., and K. D. Williams. 1993. “Social Loafing: A Meta-Analytic Review and Theoretical Integration.” Journal of Personality & Social Psychology 65 (4): 681–706. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.4.681.

- Kidwell, R. E., and N. Bennett. 1993. “Employee Propensity to Withhold Effort: A Conceptual Model to Intersect Three Avenues of Research.” Academy of Management Review 18 (3): 429–456. https://doi.org/10.2307/258904.

- Klapp, A. 2019. Bedömning, betyg och lärande. [Assessment, grades and learning]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Kravitz, D. A., and B. Martin. 1986. “Ringelmann Rediscovered: The Original Article.” Journal of Personality & Social Psychology 50 (5): 936–941. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.50.5.936.

- Lotan, R. A. 2003. “Group-Worthy Tasks.” Educational Leadership 60 (6): 72–75.

- McMillan, J. H. 2018. Classroom Assessment: Principles and Practice for Effective Standard-Based Instruction. Boston: Pearson.

- Meijer, H., R. Hoekstra, J. Brouwer, and J. Strijbos. 2020. “Unfolding Collaborative Learning Assessment Literacy: A Reflection on Current Assessment Methods in Higher Education.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 45 (8): 1222–1240. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1729696.

- Messick, S. 1989. “Validity.” In Educational Measurement, edited by R. L. Linn, 13–104. 3rd ed. New York: American Council on education and Macmillan.

- Orr, S. 2010. “Collaborating or Fighting for the Marks? Students’ Experiences of Group Work Assessment in the Creative Arts.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 35 (3): 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602931003632357.

- Poon, J. K. L. 2011. “Students’ Perceptions of Peer Evaluation in Project Work.” ACE’11: Proceedings of the Thirteenth Australasian Computing Education Conference. CR-PIT, vol. 114, 87–94. Perth, Australia: Australian Computer Society.

- Rasooli, A., H. Zandi, and C. DeLuca. 2019. “Conceptualising Fairness in Classroom Assessment: Exploring the Value of Organizational Justice Theory.” Assessment in Education Principles, Policy & Practice 26 (5): 584–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2019.1593105.

- Ross, J. A., C. Rolheiser, and A. Hogaboam‐Gray. 1998. “Student Evaluation in Co‐Operative learning: Teacher Cognitions.” Teachers & Teaching 4 (2): 299–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354060980040207.

- Selghed, B. 2004. Ännu icke godkänt: Lärares sätt att erfara betygsystemet och dess tillämpning i yrkesutövningen. [Not Yet Passed: Teachers’ Way of Experiencing the Grading System and Its Application in Professional Practice] Malmö: Malmö Högskola.

- Shiu, A. T., C. W. Chan, P. Lam, J. Lee, and A. N. Kwong. 2012. “Baccalaureate Nursing students’ Perceptions of Peer Assessment of Individual Contributions to a Group Project: A Case Study.” Nurse Education Today 32 (3): 214–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2011.03.008.

- Skolverket. 2011. Läroplan för gymnasieskolan 2011, examensmål och gymnasiegemensamma ämnen. [Curriculum, Degree Objectives and Upper Secondary School Subjects 2011] Stockholm: Fritzes.

- Slavin, R. E., and N. A. Madden. 2021. “Student Team Learning and Sucess for All: A Personal History and Overview.” In Pioneering Perspectives in Cooperative Learning, edited by N. Davidson, 128–145. New York: Routledge.

- Smith, M., and J. Rogers. 2014. “Understanding Nursing students’ Perspectives on the Grading of Group Work Assessments.” Nurse Education in Practice 14 (2): 112–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2013.07.012.

- Strijbos, J. W. 2011. “Assessment of (Computer-Supported) Collaborative Learning.” IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies 4 (1): 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1109/TLT.2010.37.

- Strijbos, J. W. 2016. “Assessment of Collaborative Learning.” In Handbook of Social and Human Conditions in Assessment, edited by G. T. L. Brown and L. Harris. New York: Routledge.

- Tierney, R. D. 2013. “Fairness in Classroom Assessment.” In SAGE Handbook of Research on Classroom Assessment, edited by J. H. McMillan, 125–144. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

- Vaughn, S., J. Shay Schumm, and J. Sinagub. 1996. Focus Group Interviews in Education and Psychology. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Vetenskapsrådet.2017. God forskningssed. Vetenskapsrådet. [ Good research practice].

- Waldow, F. 2014. “Conceptions of Justice in the Examination Systems of England, Germany, and Sweden: A Look at Safeguards of Fair Procedure and Possibilities of Appeal.” Comparative Education Review 58 (2): 322–343. https://doi.org/10.1086/674781.

- Webb, N. 1997. “Assessing Students in Small Collaborative Groups.” Theory into Practice 36 (4): 205–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405849709543770.

- Wikström, C. 2009. “National Curriculum Assessment in England: A Swedish Perspective.” Educational Research 51 (2): 255–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131880902891925.