ABSTRACT

This work illustrates what kinds of consumption emerge during a traumatic life event, theorising the interweaving of trauma and catharsis through the medium of art and craft consumption. The methodological context sits within a non-representational theory where the data are narrated through the purchases and findings, physical, emotional and cognitive engagement with art and craft materials, through to the eventual place, value and story of the made artefact itself. The work presents three main contributions: an empirical understanding of therapeutic art consumption within trauma; a methodological experiment in how using non-representational theory centred on creative processes can develop worthy modes of data collection, organisation, and analysis; and the theoretical development of a consumption framework towards a theory of cathartic consumption during trauma.

Introduction

Cancer is a spectre that has stalked my adult life. My much beloved brother Niall was diagnosed with terminal bone cancer at 28 and succumbed to it at 30. Two years later, my mother’s breast cancer (initially diagnosed some five years ago) returned with a vengeance, and she died quickly, overwhelmed with malignancies, just before her 57th birthday. My dad, who has never really recovered from losing his son and wife, died a few years later, at 64, again of cancer. When my mother died, so soon after my brother, I had just had my first child, I was in my early 20s and was left totally bereft. To say we were a close family would be an understatement. My mental and physical health deteriorated rapidly, I was diagnosed with PTSD and a mysterious autoimmune skin condition that turned into ulcerating psoriasis. Maybe not so mysterious – my whole body was literally weeping. You never get over a series of traumas like that, I remember thinking during that time ‘I will never be happy again’. Life following that became consumed with kids, study and work. I developed ways of burying and forging on, but deep sadness is always there. Happy moments in life are always bittersweet, empty chairs and wobbly toasts to absent friends. Sad and trying moments are accompanied by a deeply felt loneliness, even while surrounded by the love of my wonderful husband, sons and my remaining brother, Euan.

My own breast cancer was discovered just before my 52nd birthday, and it just seemed inevitable. I always felt very strongly that I would get it too, in fact I’m pretty sure I have survivor guilt, so there was even an element of relief. I was in the shower and suddenly, there it was. Following the shock of being diagnosed with breast cancer at the same age as my mum, my past trauma resurfaced. All the symptoms, flashbacks, sleepwalking, agoraphobia, anxiety and panic attacks – the whole gamut of PTSD – returned. The drug regime following my acute phase of treatment left me chronically ill, crippled with joint pain, and in the throes of a debilitating chemical menopause. I was trying to work, to have some kind of normality in my social and family life and hold everything together, while my own mortality was highly salient – I knew, after all, from three rounds of bitter experience, how the story might end.

If someone were to ask me what were the most important aspects of consumption that emerged during that time I would say without any hesitation, those related to arts and crafts. I have always loved making things but the busyness of life increasingly got in the way; my degree was undertaken, while a single mother with two small boys, the first in my family to get a degree (my dad was the first in his family to go to secondary school so there was a big inter-generational leap there – no family expertise to draw on). I subsequently won a full scholarship for my PhD but found I was teaching every day just to keep the wolf from the door so caved in and took a full-time lectureship at a college before I finished. Since then, the rigours of a full-time job in academia, with large administrative/leadership roles, would tax even the most ardent hobbyist. Then, during my initial sickness absence, I found myself slowly drawn back in and this has endured for the last five years.

My first job was in social services working with children on the at-risk register, so I understood the value of messy play for calming and generating healing talk and engagement. I realised pretty quickly that this reengagement with arts and crafts was a kind of self-therapy. I created an art space in my house, with an easel, shelves of materials and several pieces at different stages of completion. It has become a place of solace in my life, retreated to in order to struggle with and enjoy my engagement with art materials in times where the trauma resurfaces, or the stress gets too much. During my many retreats into my art space (and as a consumer researcher) I often thought about how we understand consumption-related responses to trauma and therapeutic consumption. I often reflect on how we might capture ‘the data’ of these encounters and began to understand the ‘data-set’ as co-emergences of the traumatised subject and the equally agentic (have you ever tried to get them to do what you want?) arts materials. I found that the somewhat linear or compartmentalised process models relating to the trauma journey did not adequately capture the conflicts, tensions and reiterative nature of ongoing trauma. This paper is then a response to a call for doing marketing differently, taking traditional consumer models of the trauma journey and experimenting with a dataset of art and craft engagements to craft some new ideas about how people consume therapeutically. The aim of this paper is not to find some alternative definitive new answers to this crisis of representation but to raise new (or at least more) questions, challenging the somewhat unidimensional representative practices of marketing and consumer thought.

Theoretical context: consumption, art, and catharsis

In this work, I would like to take therapeutic consumption seriously, and the conceptual vehicle chosen for this is catharsis. Therapeutic catharsis, I posit, encompasses shopping for and/or selecting materials, engaging in the processes of art making, presenting that art to an audience where the art materials, artist and audience co-emerge as part of the therapeutic/creative process, and eventual disposition or ‘settling-in-place’ of the artwork.

When I was first diagnosed, I read truckloads of articles about cancer, about death and dying, and I read literature about stage models relating to the threat or reality of death, particularly Kubler-Ross’ (Citation1969) classic stages of attitudes towards death and dying: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. I did think quite a lot about dying, and knew I was on a long physical and psychological journey, with a very uncertain end. I remember re-reading one of my favourite papers, Pavia and Mason (Citation2004) article about women's post-breast-cancer diagnosis, examining consumption as part of reflexive coping. I was particularly struck by their argument that consumption as a form of therapy (or in their words, a coping activity) can move beyond a temporary fix, towards encouraging future-orientation and forward-thinking in people with a heightened sense of mortality salience in this traumatic context. These writers discuss the modalities of consumption during the trauma journey through three stages of heightened, but ever-declining mortality salience ().

Figure 1. Stages process model adapted from Pavia and Mason (Citation2004).

Although these stages contain elements that hint at catharsis, these authors do not mention it, which is unsurprising as it seems largely absent (or tangential) in the consumer research canon. Celsi et al.’s (Citation1993) study of skydivers, for example, used catharsis within a dramaturgical framing of high-risk consumption, but explore it tantalisingly briefly, as ‘something’ that comes after a high-risk experience. Kozinets’ (Citation2002) study of the Burning Man Festival similarly introduces catharsis briefly, arguing that although the rituals involved obviously contain elements of catharsis, this is not a central part of his analysis. Similarly, catharsis is not attended to in the broader literature on consumer coping and stress (Moschis, Citation2007) that largely categorise consumer responses to stress in positive (confrontative consumption) and negative (avoidant consumption) dimensions. A more developed interrogation links catharsis to collective ritual in the context of heavy-metal music (Henry & Caldwell, Citation2007) employing a classical Aristotelian analysis to expound its potential for cathartic outcomes and positive re-evaluation of self.

Catharsis is not just a physical expression of feelings; it is a purging of emotions, often in a safe and controlled situation, leading to release and fresh perceptions and self-concepts. Aristotle (384 BC) posited that, when exposed to a dramatic emotional theatrical performance, catharsis would take place, leaving the audience refreshed and cleansed, but also stimulating them to rethink old situations, thus having an important critical function (Miall & Kuiken, Citation2002). Scheff (Citation1979) argues that humans seek out and enjoy activities, like literature or drama, that help to relive past traumas via the medium of spectatorship, which provides distance from confronting those emotions directly. However, in the therapy context, catharsis has been used to help people to confront and purge their emotions directly.

In psychotherapy, Breuer and Freud (Citation2009) developed a ‘cathartic method’ to purge ‘hysteria’ through the use of hypnosis, although they later abandoned this approach (Steckley, Citation2018). Moreno (Citation1946), the founder of psychodrama, focused on catharsis through spontaneous dramatic action, re-enacting scenes from the past to achieve a degree of distance and reflection on emotions as they erupt. More contemporary authors propose that catharsis forms a first therapeutic step towards more patient-responsible recovery initiatives, which are necessarily integrated into patients' ongoing everyday mental wellness regimes (Klopstech, Citation2005). This signals a shift between episodic catharsis (e.g. watching a tragic play) and a long-term cathartic journey (e.g. in a therapeutic context).

Although much debate about its therapeutic efficacy continues, catharsis endures across the many fields associated with therapy. Scheff (Citation1979, Citation1981), the contemporary canonical figure, defines catharsis as emotional discharge leading to the release of emotional tension. He argues that this has two elements: somatic and optimal distancing. The somatic element connects the physical and emotional, e.g. the physical symptom of tears following a loss or trauma. Where tears are suppressed, he argues, they remain contained within the body causing physical symptoms, and catharsis (through crying) allows for the physical release of an embodied suppression of grief. Optimal distancing relates to the degree of focus vis a vis trauma; too much distance from trauma and the person buries their emotions; too little distance, and the person becomes consumed by all-encompassing confrontation with grief. Optimal distancing is the balance between these two states, allowing expression of emotions, but without being overwhelmed, to observe and process the source of distressing emotions. According to Scheff, it is only at optimal distancing that the individual can experience enduring therapeutic catharsis.

This ‘physical-emotional-cognitive’ rendering of therapeutic catharsis defines the current state of the canon. However, the addition of materiality, or the use of material objects to facilitate the therapeutic catharsis process, is also evident. Working within the Gestalt tradition (Perls, Citation1942) Greenberg and Malcolm (Citation2002) used the ‘empty chair technique’, employing this material object within the therapeutic encounter to which challenging speech can be directed by the client. This is said to afford the necessary distance from self to achieve this physical-emotional-cognitive relation and assume the mantle of observer/outsider to one’s own strong emotions.

This employment of material artefacts as part of the therapeutic catharsis process is also evident in art therapy (Hogan, Citation2015). The basis of art therapy is to use the art/craft process to allow access to emotions and facilitate communication of these emotions within the therapeutic relationship (Rubin, Citation2012) facilitating the revealing and understanding of important interiorities (Hogan & Pink, Citation2010). Both the process of creation and the material artefact itself can be employed in the therapeutic relationship. For example, simple mark-making with pens on paper can result in unexpected images that then afford therapeutic discussion (Hass-Cohen, Citation2008). Art therapists often collect created pieces over time, and present them back to their creators, stimulating discussions of therapeutic progress, and further self-insights (Clark, Citation2016). Ogden and Fisher (Citation2015) explain how art therapy connects the physical activity of the body (the somatic), via the creative process to access impulses and feelings not readily accessible via ordinary therapy. Ordinary (i.e. talking) therapy, as it leads to cognition, is said to stimulate defence mechanisms. This physical activity (art/craft) – often not experienced since childhood – circumvents defensive barriers that keep buried negative emotions inaccessible. Art therapy within the creative expressive approach (expression of thoughts and feelings within the context of a therapeutic relationship; Appleton, Citation2001; Baker, Citation2006; Chu, Citation2010) is thought to engage a ‘bottom-up’ approach to trauma. This is firstly argued to circumvent the cognitive, by involving the physicality and material engagement of creativity, invoking emotional release; then, via this creative process, it allows a move into the cognitive realm to enable therapeutic progress through distance, discussion, analysis and reflection. Using this conceptual underpinning of catharsis as employed in therapeutic sessions, I engage with trauma to raise questions, presenting alternative modes of thinking about consumption and trauma, enhancing dominant trauma journey narratives and experimenting with non-representational methodologies for empirical data collection and analysis.

Method

What counts as data in this paper are the co-emergences of me and art during trauma. This is not easily rendered ‘as data’; the art is the data focus-thus ‘artnography’ rather than ethnography or autobiography: these data are captured through looking at the made pieces, touching them, feeling and thinking through my trauma, the processes of art-making, presenting, displaying, and writing about the work with a myriad of heterogeneous actors. Underpinning this experiment with ‘doing marketing differently’ I draw on non-representational theory (NRT; Thrift, Citation1996) as a methodological guide. NRT focuses on ‘doings’ including practice and performance (Ingold & Vannini, Citation2015) and is a process-oriented ontology focused ontologically on human and non-humans in a permanent state of becoming. NRT ‘has opened up new sets of problematics around the body, practice and performativity and inspired new ways of doing and writing … that aim to engage with the taking-place of everyday life’ (Anderson & Harrison, Citation2010, p. 1). Much work in marketing and consumer research is based on the phenomenological capture and categorisation of consumer experience in words and tables. However, as Tim Ingold states (Citation2017, p. 81) ‘we are suffering in academic life from a surfeit of words’ and despite the beauty and necessity of words per se, NRT seeks to ‘better cope with our self-evidently more than human, more than textual, multi-sensual world’ (Lorimer, Citation2005, p. 83). In marketing theory, NRT has emerged as a call to develop work which ‘does not seek to render explanations of culture through uncovering meanings and values that apparently await our […] interpretation, judgement, and ultimate representation’ (Lorimer, Citation2005, p. 84) but rather to represence ‘details of life that are seldom valued, quickly forgotten or that remain uncaptured altogether by traditional research methods’ (Hill et al., Citation2014, p. 384). What is less explored is the contribution NRT expresses through artistic practice (Barrett & Bolt, Citation2014; Boyd, Citation2011, Citation2017). The idea of represencing is important for the method practiced here, using created art and craft pieces to represence the doings-of-life within trauma. Art therapy theorist Susan Hogan (Citation2015) argues that completed art pieces stimulate multi-sensory triggers, making them temporarily ‘live’ and (re)present for the therapeutic encounter, and Stopa (Citation2009) argues they can encode in a pre-verbal, sensory and perceptual manner traumatic and buried experiences. How the work is constructed, handled, displayed, stored or destroyed can also become relevant, as it is an object embodied with emotions (Hogan & Pink, Citation2010, p. 159).

Art therapy is anti-interpretive (Hogan, Citation2015), there is no sense of static hidden meanings of therapeutic art pieces being revealed, but rather, the focus is on the process, feelings, emotions, memories that emerge, and the finished art piece can be used to represence these – thus, art, trauma and NRT seem synergistic. The three main characteristics of NRT (Hill et al., Citation2014) are (1) The onflow of the everyday which recognises the ‘processual register of experience’ (Dewsbury et al., Citation2002, p. 437). This current paper presents art and craft pieces in process since Summer, 2016 in ‘co-evolution’ (Thrift, Citation2008, p. 10) with the author following a re-subjectifying life change. Art-making opens spaces for the reworking of subjectivities (Boyd, Citation2017). It thus draws attention to ‘how life takes shape and gains expression in shared experiences, everyday routines, fleeting encounters, embodied movements, precognitive triggers, practical skills, affective intensities, enduring urges, unexceptional interactions and sensuous dispositions’ (Lorimer, Citation2005, p. 84). (2) The precognitive: here the concept of methexis becomes involved (Bolt, Citation2004). Methexis relates to the coming together of materials (bodies, art supplies, etc.) in the process of making art and crafting. There is no claim here that this art captures a cognitively worked out intentional meaning by a pre-existing subject, it is a coming together of impulse, trigger, urge, movement and material resistance. The pieces are not a concretised experience but are in an active and constituting relationship to the world, ‘encountering it, sensing it and remaking it’ (Barrett & Bolt, Citation2014, p. 192). (3) Affect and atmosphere: The NRT focus on affect is particularly relevant to art practice. Here, it is noted that ‘art is a deterritorialisation into the realm of affects. Art then might be understood as the name for a function, a magical and aesthetic function of transformation, less involved in a making sense of the world and more involved in exploring the possibilities of being in – and becoming with – the world’ (O’Sullivan, Citation2006, p. 52) As a series of encounters between bodily and art materials at the point of painful and frightening trauma, what Harrison (Citation2009, p. 1006) describes as the subject’s ‘adynamia, its impotentiality, its intermittence, misalignment, dislocation, and withdrawal’ the artefact is suffused with affect.

Interpretive analysis: thematic analysis structure

The findings are structured into five sections (feeling grief, feeling torn, feeling anger, feeling amused and feeling nothing) centring on art and craft pieces undertaken during this period. The artefacts emerge in the analysis as co-authors, our stories entwined around each other (and other others) through the creative process and the living-with (or not) each completed artefact.

Feeling grief: the imperfect scarf

My mum died 31 years ago of breast cancer, at 56. When she was having her final round of chemotherapy, I was pregnant with my first child, and we spent days in the hospital just knitting together. She knitted Gordon (my as-yet unborn son) the most beautiful Shetland shawl, in an ultra-fine 2-ply yarn, the whole shawl able to be passed through a wedding ring. The shawl was a mix of complex textural and cable patterns and mum taught me these, slipping the cable needle in and out of the stitches to fold the wool on itself and create deep, comforting textures. I was constantly with her, pregnant, knitting, passing the wool between our hands, sharing the learning and pleasure of this highly tactile creative act. Fast forward to me. My breast cancer was discovered just before my 52nd birthday. I’m not surprised I soon found myself browsing in a wool shop. Having not knitted for decades, I decided to just knit, I didn’t have a pattern I just wanted to knit. During the period and enabled by the deep meditative thinking that knitting seems to bring, I felt closer to my mum than at any time since her death, the wool winding round my fingers and the scarf growing, warming my lap, comforting me and making me feel she was with me, just at the end of this skein of wool. My first knit post-diagnosis was a scarf, using black wool with embedded silver sequins. We both love glitter and sparkle, and I was drawn to this wool in the shop. While making the scarf during this awfully uncertain and frightening time just after my diagnosis, I worked my way through several intricate folding, deep and textured cable patterns, starting one and stopping the other as I saw fit. A stream of cable-knitting consciousness. A tree of life is in the middle – like the tree of life she knitted into my son’s Shetland shawl. I remember her telling me all about it, the folktale narrating her act of creativity, which, in making a shawl, also doubles as an act of mothering – enveloping, wrapping up, warming and comforting. The knitting of a textured, comforting, but also glamorous scarf is not random. As I sat there, often with tears dripping off my face, I knitted my mother and wrapped her around me.

Without noticing at the time, I left the mistakes in. One example is a cable technique called ‘cells’ (how appropriate!), one of the lines is awry. I’d like to think this was an act of wilful mistake-making to challenge the perfectionism that I have unfortunately inherited from my mother. Don’t be mistaken, perfectionism is not thinking that everything you do has to be perfect, it is thinking that everything you do is far from perfect. The mistakes were not deliberate, me ignoring them once seen and discovered (and not unpicking my work to do it right) I might see as a self-challenge to my unhealthy obsessiveness – the ‘if it isn’t perfect, it is worthless’ mantra that has seen me chuck more things: relationships, friendships, work, etc. away. The internal anxiety over not having got everything just right, the nag always in my head that I’m not, and never will be, good enough. My life is, like hers probably was, self-narrated through persistent impostor syndrome. I’d like to think that this is a story of me deciding, post-cancer, to come to terms with myself, through the knitting of the less-than-perfect scarf, to learn to wind down a bit, even. However, three years ago when asked to produce a photograph of the scarf it dawned on me that I had never worn it at all, and indeed, I had no clue where it was. Try as I might I could not find it. At the time, I searched my phone for photographic evidence that I had not dreamt of the whole imperfect thing, but only found two photos, of course they were of the most perfect parts, the tree of life () and the nosegay pattern. Eventually, I did find it while cleaning out the garage last year, stuffed in a plastic bag with other too-good-to-throw-but-not-really-wanted items, covered in dust and bits of dried detritus. That pesky unconscious mind is not so easily disrupted.

Feeling torn: go away and forget you had cancer

I think it is a fine painting () – now. The impasto textures play on the light grey colours of my dressing gown and once red-dyed hair. I’m not sure many would notice the faint white scar around the areola of my left breast – the scar my oncologist once winked at, saying ‘it is beautiful’. The completed painting sits on my husband’s home office shelves, just behind Darth Vader, strategically camouflaged so as not to frighten visiting sons. Just after it was finished, I was out of breath, covered in globs of paints, with three broken-in-anger metal palette knives on the floor under my easel. I remember I showed a photo of this picture (then) to anyone who would look – whether they wanted to or not. It’s not every day the external examiner whips out a picture of her breasts at the post-exam-board dinner. Looking at the painting now makes me smile and shake my head at these memories. The process of the painting was a different story. Impasto is a difficult style, thick layers of paint slapped on with deliberate messy texture. You are not supposed to use acrylic paint, but I didn’t care about rules that day; however, because I didn’t use oil paint it is now chipping off but it is kept and treasured in its semi-hidden spot in its fragile, decaying state.

You may have rankled at the casual comment above, my oncologist winking at my scar, but it was a commonplace collegial appreciation, one doctor to another, of skill with scalpel and suture. The story of the painting of my scar – for it is a painting of a scar, not of my breasts – began I think with my first engagements with the machine of the NHS breast unit and my consultant breast surgeon (I will call him here ‘TitMan’), a breast-surgery expert. He told me I had cancer in March 2016, in the smart rooms of a private hospital (due to inevitable sub-contracting to the private sector that is used to manage NHS patient blockages and meet government targets – not because I can afford private healthcare). His approach was casual to say the least; he said the scar would be almost invisible – his primary focus – to make me ‘as good as before’, then I could ‘go away and forget you had cancer’. Besides the obvious feeling of being reduced to: lack of visible damage to my breast = retaining my worth as an individual, I was struck by this notion of going away and forgetting. Relating immediately to my family I dwelled instead on the question, ‘was it my turn to die?’ How on earth could I forget? As discussed above, the emotional and physical trauma of this diagnosis was tangible, PTSD, sickness, episodes of profound physical malaise that defied explanation. I was in shock, but I found myself being managed through my cancer journey, and I realised pretty quickly that I did not hold much agency here. I read as much as I could and felt really dissatisfied with my post-surgery treatment plan which seemed ultra-conservative. It wasn’t hard to work out the motivations. TitMan kept mentioning money, these expensive tests I had, the consultations, my fantastic surgery. Much better to go away and forget you had cancer. I was told – after citing a particular study to him – this is why we don’t like intelligent patients. As an academic we are used to being the ones doing the knowing, celebrated for intelligence and useful in a debate; but as a cancer patient, you are like a sausage in a sausage factory, subject to the brutal tearing of bodies by the spreadsheet treatment mantras of life-expectancy percentages (‘only 5% die within the first five years!’) ruling minimalist treatment regimens (‘you only need X, aren’t you lucky!’) that don’t account for the anecdotal, gut feeling, experiential knowledge we have of ourselves and our histories (‘ … yes, that’s what they told my mum too’). As well as the physical tearing of the surgery, that realisation that you are not special, you have no agency, you need to go away and forget you had cancer tore me psychologically. The painting, completed in an hour after one of my consultation meetings with TitMan, reflects my state of mind. It was an aggressive, almost feral act, tearing at the paint and canvas with gloveless fingers and knives, scraping fingers, breaking knives. Using acrylic instead of oil might signal a rebellion against authority and my lack of agency; but then, I have always been contermatious. However, what happened next was more interesting, in the context of being told to go away and forget I had cancer, displaying my painting, especially somewhat inappropriately, to others makes me remember wanting to be seen, to push my trauma and torn psyche and body into people’s faces, to shock and even disgust, and decidedly not to put on a pink t-shirt and smile a ‘yes sir’ cheerio wave to TitMan as I walked away and forgot.

Feeling anger: maybe she’s born with it, maybe its oestrogen?

The work shown in is a triptych with an enclosure. I’m only considering here the front piece. It is a self-portrait with me looking out from a swirl of chemical symbols for oestrogen, fashioned into a representation of my hair, and an origami vulva made from a page from the book ‘The Madwoman in the Attic’ (Gilbert & Gubar, Citation1979), painted with a bloodlike colour combination and pasted onto the collage with thick acrylic medium. Snake scales are sculpted onto the collage with moulding paste, and the hexagons from the chemical symbol are die cut from pages of the same book; particular passages deliberately left readable from within the palimpsest of colours, textures and media. The central focus is a drawing of my own eyes, glued to the collage, laminated with acrylic medium. I look angry and confrontational. I did this work over a period of around a year that followed the end of the acute phase of treatment and the beginning of the chronic phase. It’s a bit misleading to say that as I just kept adding to it constantly and in the end had to put it away, propped up against the wall, gathering dust as I couldn’t get past it. It has an interesting history of display, having been to two academic conferences, and being the illustrative cover for an academic book – again illustrating pushing my damaged body into the faces of unsuspecting people. I dumped TitMan, and my long-term breast cancer treatment was changed, following discussions (where I was listened to) about my family history, and a raft of further tests. This comprised a double drug regime, Zoladex injections every four weeks to stop my ovaries working, and an aromatase inhibitor pill every day. This combination results in a chemical menopause. Menopause can be a brutal experience as the ovaries gradually stop working over many years, bringing various side-effects. Here with this chemical variant, the ovaries are switched off within two weeks, but the rebalancing the body does, converting other hormones into oestrogens (in the body fat via the aromatase enzyme) is also stopped. Therefore, the body goes into a highly abnormal zero-oestrogen state. (My) Side effects: general accelerated ageing of body and mind; debilitating pain in the joints, particularly hips; universal dryness of mucous membranes, particularly throat and vaginal; weight gain; hair thinning; hot flushes and night sweats; loss of libido; depression and anxiety. No wonder I look pissed-off.

This is a common menopause experience in this drug regime post-breast-cancer, and it isn’t pretty; around 40% of patients stop taking the aromatase inhibitor element before the requisite treatment period has finished (Partridge et al., Citation2008; Van Herk-Sukel et al., Citation2010). I say it’s common, but it is not really discussed within the menopause support industry that seem to follow a (go away and forget you had … .?), menopause positivity discursive regime. A bit like the breast cancer pink positivity discursive regime, it seems society only wants us with no signs of ageing, perfect bodies and smiling compliant faces–who knew?

Oestrogen is a hot topic in academia, people publish papers about how women are affected by oestrogen levels and ignore the fact that all bodies have hormones and are affected by fluctuating hormone levels. However, these glorious tomes are generally reserved for women and those pesky biologically determining hormones that make us want to buy shoes or mate something. While in my two-year pain-inducing, self-altering oestrogen desert, I did this art piece. Looking at it now, two things strike me – it represences my fury at my disintegrating, recalcitrant body and I am reminded how much ‘buying things’ was involved with it.

If you ask my husband about the work, he would tell you a tale of being dragged to art shops in every place we visited, buying mundane and luxury items, from the beautiful glass brayer (to grind one’s own oil paint) from London’s labyrinthine L. Cornelissen art shop through the Pompeii red pigment from Rome’s higglety-piggelty art store Ditta G. Poggi, to budget student paints in every colour from Hobbycraft. As well as found items (like the mouldy garage-stored copy of The Madwoman in the Attic) I used a great deal of bought items to make this work. I make a point to go to an art shop in every city or town I visit and buy at least one thing. Buying stuff in an art shop is like buying something out of a mystery box, its not a finished thing and unlike, for example, buying shoes to go with an outfit (or in anticipation of finding an outfit that fits those lovely shoes) it seems so much more ephemeral, just a colour or texture you feel attracted to (with no clear purpose); a few balls of exciting yarn (sometimes not even enough to make anything); or a weird tool that piques your curiosity (but you don’t know how to use). Thinking about the feelings I have visiting these art shops it is excitement, curiosity, hope and inspiration – uplifting and therapeutic feelings, but also feeling challenged. I feel that there is a compulsion to actually use whatever I have bought, even if there is no plan in advance; I need to make something. There is also the fear involved in the empty canvas or needles – the (familiar to us academics) pressure to achieve, to create something original. Mixed-media collage (the medium of this work) is a wonderful receptacle for positive and challenging feelings. In terms of positivity, you can’t really do it wrong; it absorbs lots of different materials and it’s not a disaster if they don’t behave for you, you can paste over them. It assuages over-consumption guilt, that tube of very expensive professional cobalt-blue oil paint can give a little flash of colour that you will look at from across the room and smile, replacing the almost unbearable guilt of the unopened cap. At that time, in pain and with heightened anxiety and brain fog, the piece became a space where I could add and take away, attack with gusto or do a few nuanced strokes here and there, do a bit of cut and glue, a bit of modelling paste sculpture, a bit of reading the pages of the book to choose words, a bit of origami, a bit of stencilling, a bit of painting, a bit of assembling. However, as time went on, I realised that I did actually have to finish this work, to present a final finished piece that might make sense in the form of the aforementioned academic engagements. To do this I returned to the issue of oestrogen and named the piece, ‘Maybe she’s born with it? Maybe it’s oestrogen’ as a challenge, to think about oestrogen more seriously. I could now begin to craft a story around it and think about it in terms of its academic audience. The piece began to be suffused with the register of citations, conferences, deadlines and presentations. It now lives in several places, and imaginations, with its own life.

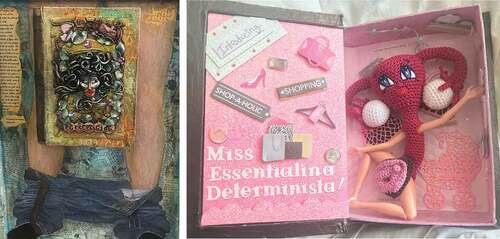

Feeling amused: essentialina determinista

Following on from the narrative and art piece above (), I’m now considering the enclosure part of the work. Upon opening the front panel there is an ancient-book-like form within, heavily embellished with sculptural elements, and in colours commensurate with the drama and depth of the front panel. A grim Medusa head sits in the centre of the book cover, with writhing hair snakes and an open mouth emitting (one might imagine) a tortured scream (see image on left, ). However, upon opening the book, within you find a glittering pink palace, and ‘Essentialina Determinista’, a pink humanoid figure made from hacked off Barbie parts and Amigurumi crochet (see image on right, ). The uterus head sports big blue eyes and a smiley face, with fallopian tube and ovary hair-bunches. The vagina body terminates with an outsize crocheted vulva. It is simultaneously disturbing and appealing. The hacked-off Barbie arms are wide-open, and she ‘ta-daaa’’s out of the deliberately aesthetically incommensurate book. During the process, my stepson walked into the kitchen to find me cutting the limbs off the (reclaimed) Barbie doll and saw nothing remarkable in this – which speaks volumes. Essentialina might be seen as the personification of the kind of menopause and breast cancer pink positivity mentioned above, shut away and silenced in her grim book-box, but when revealed flashing her cheery-blue-eyes and red-lipstick-smile. She lives front and centre on my work shelves. I’m struck now that crochet completely dominates my current yarn art endeavours. Knitting (see feeling grief) still seems too raw; I inevitably feel things I’m not comfortable with. Crochet has no longstanding attachments; it is a clean skin. It’s easy to do, fairly consequence-free, easy to ‘frog’ if a mistake is made, and easy to refashion. Amigurumi crochet is a form of yarn sculpture. I tried a few different versions of the uterus head, an afternoon’s work, to get the effect I was looking for. When she was finished, I gave a squeal of delight and laughter.

When completed I put her away in her pink glitter palace and kept her a secret. Essentialina’s revelation (as part of the Maybe she’s born with it? Maybe its oestrogen? presentation) came at the Academy of Marketing Conference in 2019, in the session designed around this special issue. I was relatively unprepared for the presentation, and anxiety heightened when I discovered I was the only person presenting. I was even more anxious when I saw who turned up, people known for their criticality. I decided to just start telling these stories, and within two minutes my tears started to fall. I have never cried while presenting, although I might have been tempted to. I was surprised by my tears, but I could not stop them, so I just soldiered on. In this encounter with an academic audience, I brought my tears to the performative in the presentation and made them part of my findings, but also discussed the value/appropriateness of such a physical manifestation of emotion in an academic setting. When presenting, I sensed a tense atmosphere in the room, some shuffled in their seats, some intellectualised – looking fascinated by the spectacle – some teared-up themselves. When the moment of revelation for Essentialina came, the tension shattered, people smiled, I laughed, Essentialina was the star, passed from hand to hand. My skill with sculpture, embroidery and crochet was marvelled-over. People stood up; more than one person hugged me, and then people started asking where lunch was. The session was over.

Feeling nothing: the art with no name

Looking back over the period in question I remember (indeed my house if full of) art and craft artefacts that don’t have a name, indeed they really don’t have any story to tell at all. As an enthusiastic storyteller, I tried really hard at this, I wondered how to talk about them in a meaningful way. I tried to weave an interesting narrative around a colourful crochet scrapghan (see image on the right, ) for example (I made several of these from leftover yarn and frogged yarn from other projects). The work is monotonous, but requires a degree of focus, the hands and eyes are occupied, but the keeping count and matching colours are approaching hypnotic. Similarly, I thought about how to make sense of my paint-dotting period, with dotted vases and random canvases with different coloured dots being created (see image on the left, ). Here, art and craft works co-narrate my occupation during this period to create ‘nice’ paintings and pretty things that did not require an iota of original thought, were devoid of challenging emotions and really did not need much expertise. The low culture tag oft (unfairly) attached to this kind of artistic endeavour actually comforted me. No need to think too much, to feel, to get frustrated. This kind of work also has the added benefit that it gathers plenty of positive affirmation, encouragement and support from friends and family via social media. However, this I think is more a scene where others’ feelings are being soothed rather than my own. I have found that friends and family (even when lovely and supportive, as mine are) feel most comfortable with you, as a cancer patient, engaging with and displaying activities like this (contrast this with the display recounted in feeling torn!). It affords a degree of comfort in that they do not have to try to find words to speak to you about your diagnosis and ongoing treatment, and you are evidencing yourself as ‘a survivor’ – someone who is doing something positive and emotionally non-challenging to progress (and evidence) your return to ‘normal’.

Discussion: cathartic consumption, ‘doing marketing differently’, and me

It is very difficult to write this discussion. Looking at the ‘data findings’ above, the weaving of personal and professional reflections is apparent, and so here, an attempt is made to offer some value in terms of a classic research contribution to understanding consumption and trauma ‘differently’; a further contribution in terms of the value of this study to those considering an NRT or an art-based approach to ‘doing marketing differently’; but also a more critical, and personal contribution in terms of ‘doing marketing differently’ from my own perspective as an academic person going through trauma. I have attempted to weave those stories together around the development of a new model of cathartic consumption during trauma.

The model developed to frame this discussion () shows two cathartic modalities: enduring catharsis – the long, slow trauma journey associated with a breast cancer diagnosis (or any trauma that is life-altering) and episodic catharsis – a series of cathartic ricochets over time between extremes of emotional distance (Scheff, Citation1981). Episodic catharsis punctuates the journey of enduring catharsis, acting as cathartic screw-threads that eventually become gradually less acute. This is a therapeutic journey, but one that recognises that the journey is not unproblematically smooth and linear, but involves peaks and troughs, iteracies and returns. These traversals into the theory of catharsis involve all consumption aspects: purchase and selection of materials; media choice; the often-painful engagement of materials towards creation; the life and value of the created artefact, its display and disposition. These traversals then imply both creative and personal trauma modalities. That is, the act of engaging with art and craft as a practice contains its own cathartic qualities (experiences of frustration, agitation, joy, destruction, relief, pride, etc.), punctuating cathartic engagement with underlying personal trauma around heightened mortality salience, fear, grief, anger and so on.

During periods of emotional confrontation, purgatory consumption takes place. The process of creativity and engagement with the object (including display of, disposition and writing about) represents a consuming of art and craft at the point of overwhelming feelings. The somatic element of catharsis is evident here in the form of tears and other bodily physical effects. The physicality of engagement with art materials (particularly in feeling torn) and the acts of (often inappropriate) display of my own physicality (in feeling torn and feeling angry) illustrate the artistic process and artefact created, including the process of writing and displaying, and how these co-narrate challenging represencing of emotional and physical outpourings. In feeling grief, the re-emergence of past trauma resulted in a scarf, which was knitted with a complex mix of pain and comfort, contained mistakes, and then was (perhaps-not-so) casually discarded. In feeling torn, the physicality of the impasto painting, unplanned and done so viciously that I broke several palette knives and tore my fingers, embodies feeling out-of-place, of being literally, psychologically and physically torn, reliving the habitus clivé as a patient-subject with a condescending and dismissive consultant. Purgatory consumption is a key element of traditional art therapy, although it has not been articulated in those terms. In terms of the methodology of NRT, the stories here evidence the powerful represencing potential of art and craft. This supports the notion in art therapy that art can be experienced as ‘live’, enacting what has been called imaginal exposure (Stopa Citation2009) drawing out productive but potentially retraumatising events. It is recognised in art therapy that facilitating the bringing up of challenging emotions and buried feelings can be hugely challenging and even psychologically dangerous for the client. This reminds me of the imperative that the attribution ‘art therapist’ is a protected professional nomenclature. Inflecting it back into ‘doing marketing differently’, using art and craft as a methodology, even beyond sensitive or traumatic contexts, raises ethical concerns, particularly given the proliferation of visual methods and techniques (e.g. collage, ZMET) popular in marketing and consumer research. This is a reminder of the ethical ramifications of research like this, which might represence an unhitherto understood set of traumas or other challenging considerations for the consumer research subject. It is worth noting here that during most of this period I was being supported by an NHS cancer rehabilitation therapist.

I have employed a neologism for the process of coming down from this extreme and unliveable point that relates to how this is facilitated, not only in terms of ‘coming down’ but also in making progress, facilitating enduring catharsis. The anodynamic consumption (from anodyne – soothing and quietening, and dynamic – moving forward) engages with the role of distancing, being objective. This is most clearly seen in feeling angry and feeling amused as the objectification machine of my various academic engagements performed a distance from the art, facilitating analysis and even eventually critical amusement. These episodes of consumption also relate to my discovery of art stores. Shopping for and sourcing mixed-media materials allows the consumer to experience in totality the wonders of the art and craft store, but also an opportunity for control-enhancing mastery of new skills and knowledge. Using meaningful found and recycled objects and re-arting them, combining them with the myriad of things that can be made and bought to enable mixed-media collage makes the art/craft store trip more spontaneous and exciting, leading to entanglements of creativity, exploration, learning and research, excitement and experimentation. Following on from this, the eventual discipline of the engagements between these processes and academia, speaking to an audience, presenting my work, becoming more collaborative rather than solitary, inviting others to consume my art, emotions and indeed myself, are all encompassed by anodynamic consumption. This final set of stories around the role of anodynamic consumption might be read as a story where represencing art with an academic audience progressed the enduring catharsis journey because the objectivity and emotional distance of academia provided a force that acted against the somatic, over-emoting of purgatory consumption. However, this works both ways, in terms of what might be called the everyday trauma of working in the individualising neoliberal university, invading this over-objective and detached academic space with represenced trauma via challenging non-normative forms of (non)representation might provide a critical intervention into consumer and marketing research, where emotionality and a shared group dynamic meet, and interfere with, its competitive entrepreneurialism, objectivity and individualism.

These periods of purgatory and anodynamic consumption are punctuated by what I have called convalescent consumption. Convalescence signifies a period of calm and rest, created here by what has been called in the art therapy literature an art/craft safe space (Stopa, Citation2009). This also, however, represents a suppression period, with a great deal of distance being enacted between this and the realms of cognition and emotion. This is most clearly seen in the feeling nothing section. I discuss here the repetitive dotting art, and making random crochet blankets, which requires just enough concentration to preoccupy thoughts and tamp emotions but not enough to require creative (thus risky) decision-making or expression. This type of repetitive work is similar to trauma-therapy techniques found in the increasingly popular progressive counting tradition (Greenwald, Citation2008) a therapeutic low-engagement (and thus less directly emotionally confrontational) distraction and distancing technique. Counting (and other repetitions) also form the backdrop of more longstanding traditions of psychological benefits, for example yoga and meditation. Consumption of more mundane, repetitive art and craft practice (like crochet scrapghan and dotting art) is largely not explored in the art therapy literature (indeed the suppression/repression that goes along with it seems largely pathologized). However, this not thinking about/feeling things practice, counting out loud and repeating mantras over and over again (like sc3, dc2 as found in crochet patterns) are here delineated as an important part of the trauma journey, a period of rest from the more challenging purgatory and anodynamic consumption periods. This finding also challenges the literature on consumer stress and consumption coping strategies that categorise coping strategies as either confrontative or avoidant, with avoidant consumption responses (as convalescent consumption as an ‘escape theory’ might be categorised, also see Hirschman, Citation1992) seen as a largely negative set of consumption activities (e.g. smoking, drinking, gambling, medicating; Moschis, Citation2007). Here, researchers examining ‘avoidant’ consumption strategies might find the more positive, productive activities circumscribed here as evidence of convalescent consumption as a useful focus.

Overall, the model above represents a development and enhancement of the typical models found in much research on consumption of trauma and other discontinuous changes, or consumer transformations. The addition of interruptions and iterations – in the form of the ricochets provided by understanding how episodic catharsis punctuates the enduring cathartic journey – adds an element of complexity and nuance that might prove useful to other scholars developing understandings of the role of consumption in these contexts. This might offer further insights using a more developed consideration of the different modalities of catharsis in high-risk consumption activities (e.g. Celsi et al., Citation1993) and life-transforming consumer experiences (e.g. Kozinets, Citation2002), as well as studies of consumer coping during stress or trauma.

A further contribution can be found at the interface of consumption, art and NRT. NRT and art share a focus on what has been called carnal knowledge (Barratt & Bolt, Citation2012), that is, intervening in the world through creative and material acts of a configuration of bodies and other material things that enable and extend conscious awareness (Boyd & Edwardes, Citation2019). In this study, the art and craft pieces were all emergent, as I also became emergent with them. The scarf in feeling grief for example, had no pre-purpose, this emerged only in the process of the entanglement of it becoming, and my becoming. This is storied here through wandering into a wool shop; buying the sparkly wool that just appealed to me; the connection with my mother’s last weeks of life via the complex cable patterns I started to do (I followed no pattern); the textural and temperature engagements as the scarf grew; the tears as the emotional connections formed in my head; and the unintentional and unremembered disposition of the scarf as ‘not-really-good-enough’ that made me connect with my own perfectionism and imposter syndrome during the academic writing process. Similarly, in feeling torn, feeling angry and feeling amused the work, and my engagement with the practice of art and craft is emergent: unplanned impasto painting; spontaneous multi-media collage; and experimental amigurumi sculpture, respectively. This series of engagements with what might be called ‘data’ highlights the value of this type of study in bringing together art and NRT around a consumption issue but from a different ontological perspective. Linear process models of consumer change begin and end with a worked-out subject agentically transforming and emerging as a worked-out subject in a ‘new normal’ subjectivity, via consumption. Combining NRT and art as a methodology instead understands an animated ecology where multiple human and non-human actors, including here sensing bodies situated within ‘more than human more than textual, multi-sensory worlds’ (Lorimer, Citation2005, p. 83) craft a messier account of permanent, tentative, multi-agentic becoming.

This paper, written within trauma, relates to an enduring cathartic journey, interspersed with a series of episodic cathartic ricochets between the far edges of distance (convalescent vs purgatory consumption) and the quest for the sweet spot of optimal distance (anodynamic consumption) where enduring therapeutic catharsis occurs. In terms of presenting this to an external audience as a piece of NRT research about consumption, the ‘data’ of my art and crafts practice work to illuminate NRT’s ‘processual register of experience’ (Dewsbury et al., Citation2002, p. 437), by represencing diverse trauma events as a methexis – the coming together of impulse, trigger, urge, movement and material resistance in the face of re-subjectification, avoiding the fantasy of capturing a cognitively worked-out intentional meaning by a pre-existing subject. In terms of NRT’s concern with affect, I hope I have given an impression to the reader of affect not as a personal feeling, or expression of pre-constructed emotions, but rather of forces through a body as it is affected in an active and constituting relationship to the world, ‘encountering it, sensing it and remaking it’ (Barrett & Bolt, Citation2014, p. 192). As such, the work strives to be ‘less involved in making sense of the world and more involved in exploring the possibilities of being in – and becoming with – the world’ (O’Sullivan, Citation2006, p. 52).

Conclusion and reflections

It has to be noted that the above is only one story through the data. It is a necessary artefact of the academic register to produce the golden apple of knowledge and truth that you have found in your heroic researcher quest in the world, the one that you will defend to your peers and students as the light, the truth, the way. Presenting marketing and consumer research differently is not like that. At times (often in fact) this piece veers into self-indulgent over-disclosure and uncomfortable over-exposure. Being self-indulgent and making the reader uncomfortable are inextricable aims of the piece. Where else, but on a special issue of representing differently, can you resist as an academic exposing yourself in a way completely at odds with the objective, rational and self-brand-managing academic (non)person we are expected to be? I’m not innocent here, one of the things this work made me realise and confront is how comforting in its suppressed emotionality academic endeavour is, and how I had often found pathological distance from my emotions by using my own academic persona to bury myself within. I remind myself that even though I consider myself a reflexive interpretive researcher, I had not realised how disembodied I had become, via my profession, until my body confronted me with its recalcitrant refusal to be silent. I couldn’t rationalise this one, I couldn’t negotiate cleverly, or construct a winning argument, I also could not research the shit out of it – paraphrasing The Martian – my ‘hab’ exploded. I propose that there is no innocent position from which to critique others, so my ambition for this work encompasses: an academic hope that it will stand as a serious academic contribution on cathartic consumption, offering theoretical insight into the role of consumption in the trauma and therapeutic recovery process; a personal hope that it will continue to act as a focus for my own therapeutic recovery journey; a collegial hope that those who encounter and read it who might also be in the midst of trauma find something of value and support here, and finally an idealistic hope that others might find its combination of art and craft material/process/artefact non-representational co-authorship an inspirational actor in their own endeavours of thinking about marketing and consumer research differently.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Shona Bettany

Shona Bettany is Professor of Marketing and Head of Department of Logistics, Marketing, Hospitality and Analytics at Huddersfield Business School, University of Huddersfield ([email protected]). She is a consumer ethnographer, focussing on consumer culture in all its guises but more specifically on material-semiotic approaches to consumption. These approaches have illuminated such topics as gender and sexuality, contemporary family consumption and animal-human relations. She is published in Marketing Theory; Sociology; Marketing Letters; European Journal of Marketing; Journal of Business Resarch; Consumption, Markets and Culture; Journal of Marketing Management and Advances in Consumer Research.

References

- Anderson, B., & Harrison, P. (2010). The promise of non-representational theories. In B. Anderson & P. Harrison (Eds.), Taking-place: Non-representational theories and geography (pp. 1–36). Ashgate.

- Appleton, V. (2001). Avenues of hope: Art therapy and the resolution of trauma. Art Therapy, 18(1), 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2001.10129454

- Baker, B. A. (2006). Art speaks in healing survivors of war: The use of art therapy in treating trauma survivors. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 12(1–2), 183–198. https://doi.org/10.1300/J146v12n01_10

- Barratt, E., & Bolt, B. (2012). Carnal knowledge: Towards a 'New Materialism' through the arts. London: Tauris.

- Barrett, E., & Bolt, B. (2014). Material inventions: Applying creative arts research. Tauris.

- Bolt, B. (2004). Art beyond representation. I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd.

- Boyd, C. (2011, January 31 – February 1). An event of therapeutic art-making and its nonrepresentational geographies draft [paper presentation]. IAG Cultural Geography Study Group Conference, Canberra, Australia.

- Boyd, C. (2017). Non-Representational geographies of therapeutic art making. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Boyd, C. P., & Edwardes C. (Eds.). (2019). Non-Representational theory and the creative arts. Springer.

- Breuer, J., & Freud, S. (2009). Studies on hysteria. Hachette UK.

- Celsi, R. L., Rose, R. L., & Leigh, T. W. (1993). An exploration of high-risk leisure consumption through skydiving. The Journal of Consumer Research, 20(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1086/209330

- Chu, V. (2010). Within the box: Cross-cultural art therapy with survivors of the Rwandan genocide. Art Therapy, 27(1), 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2010.10129563

- Clark, S. M. (2016). DBT-Informed art therapy: Mindfulness, cognitive behavior therapy, and the creative process. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Dewsbury, J.‐D. (2003). Witnessing space: ‘Knowledge without contemplation’. Environment & Planning A, 35(11), 1907–1932. https://doi.org/10.1068/a3582

- Dewsbury, J.‐D, Harrison, P., Rose, M., & Wylie, J. (2002). Introduction: Enacting geographies. Geoforum, 33(4), 437–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7185(02)00029-5

- Gilbert, S., & Gubar, S. (1979). The madwoman in the attic. Veritas paperbacks. https://doi.org/10.12987/9780300252972

- Greenberg, L. S., & Malcolm, W. (2002). Resolving unfinished business: Relating process to outcome. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(2), 406–416. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.70.2.406

- Greenwald, R. (2008). Progressive counting: A new trauma resolution method. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 1(3), 249–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361520802313619

- Harrison, P. (2009). In the absence of practice. Environment and Planning D, Society & Space, 27(6), 987–1009. https://doi.org/10.1068/d7907

- Hass-Cohen, N. (2008). Partnering of art therapy and clinical neuroscience. In N. Hass-Cohen & R. Carr (Eds.), Art therapy and clinical neuroscience (pp. 21–42). Jessica Kingsley.

- Henry, P., & Caldwell, M. (2007). Headbanging as resistance or refuge: A cathartic account. Consumption Markets & Culture, 10(2), 159–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253860701256265

- Hill, T., Canniford, R., & Mol, J. (2014). Non-Representational marketing theory. Marketing Theory, 14(4), 377–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593114533232

- Hirschman, E. C. (1992). The consciousness of addiction: Toward a general theory of compulsive consumption. The Journal of Consumer Research, 19(2), 115–179. https://doi.org/10.1086/209294

- Hogan, S. (2015). Art therapy theories: A critical introduction. Routledge.

- Hogan, S., & Pink, S. (2010). Routes to interiorities: Art therapy and knowing in anthropology. Visual Anthropology, 23(2), 158–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/08949460903475625

- Ingold, T. (2017). Correspondences. University of Aberdeen Press.

- Ingold, T., & Vannini, P. (2015). Non-Representational methodologies: Re-envisioning research (pp. vii–x). Routledge.

- Klopstech, A. (2005). Catharsis and self-regulation revisited: Scientific and clinical considerations. Bioenergetic Analysis, 15(1), 101–131. https://doi.org/10.30820/0743-4804-2005-15-101

- Kozinets, R. V. (2002). Can consumers escape the market? Emancipatory illuminations from burning man. The Journal of Consumer Research, 29(1), 20–38. https://doi.org/10.1086/339919

- Kubler-Ross, E. (1969). On death and dying. Touchstone.

- Lorimer, H. (2005). Cultural geography: The busyness of being ‘more-than-representational’. Progress in Human Geography, 29(1), 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132505ph531pr

- Miall, D. S., & Kuiken, D. (2002). A feeling for fiction: Becoming what we behold. Poetics, 30(4), 221–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-422X(02)00011-6

- Moreno, J. L. (1946). Psychodrama (Vol. 1). Beacon House. https://doi.org/10.1037/11506-000

- Moschis, G. P. (2007). Stress and consumer behavior. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 35(3), 430–444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-007-0035-3

- O’Sullivan, S. (2006). Art encounters Deleuze and Guattari: Thought beyond representation. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ogden, P., & Fisher, J. (2015). Sensorimotor psychotherapy: Interventions for trauma and attachment (Norton series on interpersonal neurobiology). WW Norton & Company.

- Partridge, A.H., LaFountain, A., Mayer, E., Taylor, B. S., Winer, E., & Asnis-Alibozek, A. (2008). Adherence to initial adjuvant anastrozole therapy among women with early-stage breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 26(4), 556–562. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5451

- Pavia, T. M., & Mason, M. J. (2004). The reflexive relationship between consumer behavior and adaptive coping. The Journal of Consumer Research, 31(2), 441–454. https://doi.org/10.1086/422121

- Perls, F. (1942). Ego, hunger, and aggression: The beginning of Gestalt therapy. Random House.

- Rubin, J. A. (2012). Approaches to art therapy: Theory and technique. Routledge.

- Scheff, T. J. (1979). Catharsis in healing, ritual and drama. University of California Press.

- Scheff, T. J. (1981). The distancing of emotion in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 18(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0085960

- Steckley, L. (2018). Catharsis, containment and physical restraint in residential child care. British Journal of Social Work, 48(6), 1645–1663. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcx131

- Stopa L. (Ed.). (2009). Imagery and the threatened self: Perspectives on mental imagery and the self in cognitive therapy. Routledge.

- Thrift, N. (1996). Spatial formations. Sage.

- Thrift, N. (2008). Non‐representational theory: Space, politics, affect. Routledge.

- Van Herk-Sukel, M.P., van de Poll-Franse, L.V., Voogd, A.C., Nieuwenhuijzen, G. A. P., Coebergh, J. W. W., & Herings, R. M. C. (2010). Half of breast cancer patients discontinue tamoxifen and any endocrine treatment before the end of the recommended treatment period of 5 years: A population-based analysis. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 122(3), 843–851. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-009-0724-3