?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Student performance data is increasingly used to monitor and evaluate teachers. This study examines whether the turnover intentions – if teachers would change schools given the chance – of teachers in socioeconomically disadvantaged classrooms are moderated by teacher appraisal practices based on student academic performance data at the school system-level. Three-level hierarchical modelling in 46 education systems is conducted based on the Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) from 2018. Results show that the effect of classroom socioeconomic composition on teacher turnover intentions increases as a function of performance-based teacher appraisal. However, this is only true when the appraisal is conducted by external authorities, and not so when conducted by the school management team. The models are then re-run by school consequences of appraisal such as dismissal, financial bonuses, or sanctions, and then by teacher characteristics, including gender, experience, and teaching subject. Experienced teachers in socioeconomically disadvantaged classrooms are more likely to change schools in school systems with more performance data-based teacher appraisal. These results underscore the potential pitfalls of performance data-based accountability systems for students in socioeconomically disadvantaged educational settings.

1 Introduction

Recent decades have seen a global push towards evermore educational accountability, where the perceived success of school leaders and teachers is increasingly tied to student performance data (i.e. how well students score on school-based or national and regional assessments) (OECD Citation2013a; Holloway, Sørensen, and Verger Citation2017; Smith and Kubacka Citation2017; Verger, Fontdevila, and Parcerisa Citation2019). As most schools are publicly funded, the argument for increases in accountability states that children – as well as the larger-society – are entitled to the ‘maximum-benefit’ of education (Brill et al. Citation2018). An overarching goal of the accountability discourse is the importance of continuously strengthening and improving education systems worldwide. While the use of student performance data for accountability purposes is now widespread, there is mounting concern that this practice puts undue stress on teachers and school leaders and distorts the democratic educational imperative (Ball Citation2003; Berryhill, Linney, and Fromewick 2014; Biesta Citation2007; Ball Citation2016; Jerrim and Sims Citation2021; Lee and Wong Citation2003; Valli and Buese Citation2007). Meanwhile, it has been shown that ‘teaching is increasingly a career of movement in and out’ (Skilbeck and Connell Citation2003, 32–33). This phenomenon has been observed in several countries and is a growing occurrence globally (Craig Citation2017). On the one hand, there is the issue of ‘macro’ mobility between the world of teaching and other professions, and on the other, there are ‘micro’ movements, concerning the mobility of teachers between schools (Vagi and Pivovarova Citation2017). Related to these latter ‘micro’ mobilities, an underexplored – particularly from a cross-national perspective – aspect of performance-based accountability is its relationship to the attrition of teachers in socioeconomically disadvantaged or ‘hard-to-staff’ settings. A wealth of research has demonstrated that schools with higher proportions of socioeconomically disadvantaged students deal with disproportionately higher turnover rates (Bonesrønning, Falch, and Strøm Citation2005; Feng Citation2009; Hanushek, Kain, and Rivkin Citation2004; Scafidi, Sjoquist, and Stinebrickner Citation2007), but less is known about the institutional correlates of such inequitable turnover.

The accountability drive continues despite mixed effects on student outcomes (Darling-Hammond Citation2004; Figlio and Loeb Citation2011; Hanushek and Raymond Citation2005; McNaughton, Lai, and Hsaio Citation2012; Ryan et al. Citation2017; van Geel et al. Citation2016; Wong, Cook, and Steiner Citation2010). It has been found that socioeconomic inequities between students widen under various accountability regimes (Strietholt et al. Citation2019). Historically, performance-driven accountability systems have neglected the issue of educational equity (Lee and Wong, Citation2003). Higher-achieving (and generally more socioeconomically advantaged) schools and students are rewarded while lower-achieving ones are punished. Darling-Hammond (Citation2004) asks:

Will investments in better teaching, curriculum, and schooling follow the press for new standards? Or will standards and tests built upon a foundation of continued inequality simply certify student failure more visibly and reduce access to future education and employment?

The aim of the present study is to empirically address this problem and investigate whether increased student performance data-based accountability practices (in this case, formal teacher appraisal) is linked to increased micro mobilities of teachers between schools. Three-level generalized linear regressions are employed to test whether the relationship between classroom socioeconomic composition and teacher turnover intention (a random classroom-level slope) is moderated by school system-level accountability.

1.1 The accountability paradox

Educational reforms are increasingly focused on the notion of ‘standards’ (Ball Citation2003, Citation2016; OECD Citation2013a, Citation2013b; UNESCO Citation2015a; Citation2015b; UNESCO Citation2017), but accountability as a concept is hard to pin down (Bovens Citation2007, Citation2010). Bovens (Citation2010) writes that while standards are in general seen as positive and normatively defined individual or organizational traits, they are to be distinguished from accountability mechanisms. This paper focuses on this latter definition of ‘accountability as a mechanism,’ an umbrella term for practices which aim to hold educational actors accountable for their performance.Footnote1 In relation to the use of student performance data, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD Citation2013a) lists practices such as the use and publication of achievement data (as in the case of school league tables), the assessment of teacher practices, as well as the consequences of teacher appraisal as possible accountability mechanisms. There is some variation in the implementation of accountability and school improvement practices schools and school systems (Verger, Fontdevila, and Parcerisa Citation2019). Rivas and Sanchez (Citation2022) discuss a ‘regulatory governance turn’ in Latin America, while Barbana, Dumay, and Dupriez (Citation2020) highlight the lower-stakes accountability regimes more common in continental Europe. Despite these distinctions, ‘there is always a tension between using data for school development and instructional goals, and using data for accountability goals’ (Schidkamp Citation2019, 260) or ‘soft’ versus ‘strong’ or ‘neo-liberal’ forms of accountability where teachers are viewed in terms of their utilitarian value (Maroy and Voisin Citation2017).Footnote2 There is also evidence of a convergence of test-based accountability reforms globally (Verger, Parcerisa, and Fontdevila Citation2018).

This paper focuses on a somewhat narrow dimension of accountability: the use of student performance-data to assess teachers and their teaching practices, and variations in the consequences of such assessments. Previous research suggests that such practices may have negative and unintended consequences for teachers as well as students at the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum (Ball Citation2003; Darling-Hammond Citation2004; Jerrim and Sims Citation2021; Polesel, Rice, and Dulfer Citation2013). Due to the focus on performance, teaching practices may be constrained in order to ‘teach to the test’ and educational experiences consequently narrowed. In addition, the difficulty of raising student achievement is not constant across schools. While some policies account for the external factors which influence achievement and vary across schools, others do not and hold each school and teacher to a similar standard (Darling-Hammond Citation2004).

Biesta (Citation2007) traces the accountability movement in education to a wider global cultural shift which has its roots in the capitalist logic of the market, where states become providers and citizens consumers. Such shifts are seen through increasingly marketized education systems which are often characterized by standards, accountability and decentralization (Verger, Parcerisa, and Fontdevila Citation2018). In theory, performance-based accountability is positioned as a sort of constraint on school marketization and autonomy. According to Brill et al. (Citation2018), ‘the rationale here is that when schools are granted more independence over the methods they use to achieve education outcomes, accountability increases in significance, as a more autonomous, school-led system depends even more heavily on a fair and effective accountability system’ (p. 2). In practice, however, such policies may end up compounding school market mechanisms as they are contingent upon the larger organizational context (Peters and van Nispen Citation1998). Ball (Citation2003) writes:

Such developments are deeply paradoxical. On the one hand, they are frequently presented as a move away from ‘low-trust’, centralized, forms of employee control. Managerial responsibilities are delegated, initiative and problem-solving are highly valued. On the other hand, new forms of very immediate surveillance and self-monitoring are put in place; e.g. appraisal systems, target-setting, output comparisons.

While most accept the need for school-improvement, few are satisfied with the ways in which it is carried out (Vanhoof and van Petegem Citation2007). Some argue that such ‘standards’-based reforms should be used primarily to strengthen curricula and inform better resource allocation and practice, while others argue that the problem stems from a fundamental ‘lack of effort’ on the part of educators, and that higher stakes consequences such as sanctions for those who fail to meet such standards are necessary (Darling-Hammond Citation2004; Maroy and Voisin Citation2017). The two perspectives can be summed up as the school-improvement perspective versus the accountability perspective and have also to do with ‘who determines the quality of education: the government or the school itself’ (Vanhoof and van Petegem Citation2007, 105). Traditionally, the accountability perspective was solely tied to external evaluations, and the school improvement perspective to school-based evaluations. However, school-based evaluations are becoming increasingly influenced by accountability, and the distinction between accountability (external evaluation) and school-improvement (internal evaluation) is no longer as clear. This is mirrored by the blurring between formative and summative teacher appraisal (Smith and Kubacka Citation2017). Two dimensions of accountability are therefore included in the present study: teacher appraisal conducted by external authorities or bodies (i.e. school inspectors, government authorities) and teacher appraisal conducted by the school management team.

1.2 Teacher turnover intentions and student socioeconomic composition

By now, the importance of teachers is well-accepted. This is especially true for socioeconomically disadvantaged students who have less access to at-home learning supports (Darling-Hammond Citation2000; Rivkin, Hanushek, and Kain Citation2005; Hattie Citation2003; Nilsen and Gustafsson Citation2016). Despite this, worldwide, the teaching profession faces challenges related to worsening working conditions, workload, and job stress, resulting in issues attracting and retaining individuals to the field, and even more so to socioeconomically disadvantaged settings (see for example Allen, Burgess, and Mayo Citation2018; Hanushek, Kain, and Rivkin Citation2004; Sass, Seal, and Martin Citation2011; Vagi and Pivovarova Citation2017; Valli and Buese Citation2007). Individuals who enter the profession with the goal of positively impacting society often leave feeling disillusioned (Perryman and Calvert Citation2020). This may be particularly true of novice teachers (Fantilli and Macdougall Citation2009; Hanushek and Rivkin Citation2010b, Citation2010a; Ingersoll Citation2001; Marinell et al. Citation2013), but research is scarce regarding other teacher characteristics associated with higher turnover rates. Issues related to attrition in low-socioeconomic status (SES) settings have been found in Sweden, Canada, the USA, Australia, Chile, and England (Allen, Burgess, and Mayo Citation2018; Carver-Thomas and Darling-Hammond Citation2017; Den; Elacqua, Hincapie, and Martinez Citation2019; Ingersoll Citation2002; Karsentil and Collin, 2013; Lindqvist et al., 2014; Loeb et al., 2005; Scafidi et al., Citation2007). A high teacher attrition rate hinders school climate and the success of students (Hanushek, Rivkin, and Schiman Citation2016). This may be because the school is forced to hire individuals with lower competency or qualification levels, the staff are not used to working alongside each other, or the school cannot fill the open spots and are forced to enlarge classes (Ingersoll Citation2001; Sorensen and Ladd Citation2020).

It therefore goes without saying that it is in the interest of education systems to keep teachers in hard-to-staff settings. In the context of this article, hard-to-staff signifies a socioeconomically disadvantaged context, and stems from previous work demonstrating issues of attrition in such settings (Bonesrønning, Falch, and Strøm Citation2005; Boyd et al. Citation2005; Darling-Hammond Citation1997; Hanushek et al., 2001; Scafidi, Sjoquist, and Stinebrickner Citation2007). This may be a school with a high proportion of socioeconomically disadvantaged (low-SES) students in more segregated school systems, or a classroom with a high proportion of low-SES students in case a system does not practice mixed ability grouping within schools. In both cases, the classroom setting is the most important. Allensworth, Ponisciak, and Mazzeo (Citation2009) outline several main reasons teachers cite their dissatisfaction: principal effectiveness, dysfunctional administration, challenging students, low salary, and limited autonomy due which may be due to additional accountability practices. Sims and Allen (Citation2018) note that often there are more job openings in such schools, and therefore teachers may take such positions with the intention to leave as soon as another opportunity comes along. In Turkey, for instance, teacher assignment is based on a seniority score, which is positively influenced by working in such schools (Özoğlu Citation2015). There is therefore likely a proportion of teachers who intend to leave such contexts regardless of school leadership or working conditions. As such, there may be a somewhat immovable link between classroom/school SES and teacher attrition across education systems. However, we know little about the institutional determinants of the remaining variation in teacher turnover.

1.2.1 Accountability and teacher turnover

While there is a host of literature discussing accountability and teacher appraisal practices (see for example Holloway, Sørensen, and Verger Citation2017), cross-national literature linking accountability to teacher turnover is scarce. There are several reasons that performance-based accountability may be tied to teacher turnover, but they are primarily due to increased workload, a lack of job autonomy and sense of purpose, and stress (Byrd-Blake et al. Citation2010; Feng, Figlio, and Sass Citation2018; Richards Citation2012; Ryan et al. Citation2017). Lower-performing schools already face greater administrative pressures in general (Browes Citation2021). A recent study by Jerrim and Sims (Citation2021) found a link between performance data-driven accountability and teacher stress cross-nationally. von der Embse et al. (Citation2016) find this link in four states in the USA. Using data from Florida, Feng, Figlio, and Sass (Citation2018) find that schools which fell into a low-performing category experienced a jump in the probability of teacher turnover relative to schools that missed the cutoff. This was particularly true for the ‘best’Footnote3 teachers in the school. With data from Chile, Elacqua, Hincapie, and Martinez (Citation2019) find that accountability practices (such as sanctions) result in higher teacher turnover rates in low-performing schools. In short, performance data-based accountability entails closer monitoring of the performance of teachers, a loss of job autonomy, longer hours and poor working conditions, and a school climate characterized by stress and ‘emotional contagion’ amongst the staff (Jerrim and Sims Citation2021). Other studies outline how accountability and teacher evaluation policies are often mismatched with teacher perspectives (La Londe Citation2017; Pizmony-Levy and Woolsey Citation2017). In one of the only cross-national studies on the topic, Smith and Holloway (Citation2020) use OECD TALIS data from 2013 and find a link between decreased teacher satisfaction with their current schoolFootnote4 and school testing culture. This study follows a similar line of questioning but expands the analysis to 46 countries participating in TALIS 2018, with a special focus on turnover intentions specifically in socioeconomically disadvantaged contexts.

The main hypothesis of this paper is that teachers working in classrooms with a high proportion of low-SES students face a more challenging uphill battle when it comes to influencing student achievement as compared to their peers working in more affluent or even mixed socioeconomic settings (Lazear Citation2001; Polesel, Rice, and Dulfer Citation2013). Therefore, if their evaluations are tied to student achievement data, they face a higher likelihood of stress and lower levels of autonomy over their profession, and therefore may be more likely to wish to work in a different school. Over and above this, I expand on previous research and investigate whether the consequences of appraisal interact with the classroom SES-turnover slope. Given that monetary sanctions and incentives are increasingly common consequences of appraisal in high-stakes accountability systems (OECD Citation2021), it is relevant to determine whether the relationship between accountability and teacher turnover intentions varies according to these consequences as past evidence on the importance of such incentives is mixed (Boyd et al. Citation2005; Falch Citation2011; Feng Citation2009; Hanushek, Kain, and Rivkin Citation2004; Jerrim and Sims Citation2021).

The study investigates the following research questions:

1. Are teachers’ odds of reporting that they wish to change schools positively related to the proportion of socioeconomically disadvantaged students in their target classroom?

2a. Is the marginal effect of classroom socioeconomic composition on teachers’ probability of wishing to change schools positively related to the level of achievement-data based accountability (teacher appraisal) in a school system?

2b. Does this relationship vary depending on who conducts the teacher appraisal?

3. Does the marginal effect of class SES composition on a teachers’ probability of changing schools vary as a function of teacher characteristics (gender, experience, subject-matter) or school consequences of assessment (dismissal, financial bonus, or material sanctions)?

2 Data and method

2.1 Data source

Data for this study come from the Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in 2018. The analysis incorporates between 40 and 46 systems (due to missingness on certain variables in the subgroup analyses). TALIS follows a two-stage stratified sampling procedure, and samples a nationally representative group of approximately 200 schools selected with a probability proportional to their size. Within each school, questionnaires are administered to the principal as well as a selection of approximately 20 teachers with equal probability based on the subjects taught at their school. displays the descriptive statistics for system-level variables and number of teachers and schools sampled in each country. For descriptive statistics of all variables, see Table A1 in the Appendix.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of system-level variables.

TALIS provides teacher weights that are inversely proportional to the probability of selecting a given teacher within a school to the TALIS sample. However, there are no senate weights provided by TALIS, which are sometimes necessary in cross-national analysis to ensure that estimates are not biased by a differing number of teachers sampled per education system. Therefore, both teacher and school senate weights are computed.Footnote5

2.2 Variables

For descriptive statistics of all variables, see in the Appendix. The dependent variable is a question asked to the teachers in the teacher questionnaire about their desire to change schools (see ). Here, ‘agree’ and ‘strongly agree’ are coded as 1, while ‘strongly disagree’ and ‘disagree’ are coded as 0.

Teachers were also asked about the socioeconomic composition of their target classrooms, asking them to indicate the proportion of socioeconomically disadvantaged students, ranging from 1 = none, 2 = 1% to 10%, 3 = 11% − 30%, 4 = 31% − 60%, 5 = more than 60%. The focus is on the classroom level so as not to exclude teachers working in socioeconomically heterogeneous schools, but where within-school teacher sorting may occur. Teacher-level control variables include experience (coded 1 if a teacher has less than 5 years of experience), subject matter specialization (coded 1 if a teacher does not have the relevant education for the subject matter they currently teach across mathematics, science, humanities, and other subjects), job satisfactionFootnote6 (scale fulfills metric invariance across countries), self-efficacy (scale fulfills metric invariance across countries), and gender (coded 1 as female).

The explanatory variable of interest comes from the principal questionnaire and is therefore at the school level before aggregation. Principals were asked, ‘Who uses the following types of information as part of the formal appraisal of teachers’ work in this school?’ (OECD Citation2019, 12). This study focuses on answers related to student-achievement data, such as students’ external results (e.g. national test scores) and school-based and classroom-based results (e.g. performance results, project results, test scores). For the present paper, only school management team (SMT) or external individuals or bodies were included.Footnote7 Each of these categories was coded separately as 1 for each school. Each was then aggregated to the country level, with school weights applied.

Principals were also asked to indicate the frequency with which any of the following occur in the school, following a formal teacher appraisal, material sanctions such as reduced annual increases in pay are imposed, salary increase or payment of a financial bonus, or a dismissal or non-renewal of contract. Frequency-related responses include ‘never,’ ‘sometimes,’ ‘most of the time,’ or ‘always.’ The variables for sanctions, financial bonus and dismissal were each coded as 1 if the principal did not select ‘never.’

Control variables include school type (coded as 1 if private school), school location (coded as 1 if school is in a rural or remote location or a small town), and the proportion of students from socioeconomically disadvantaged homes (1 = none, 2 = 1% to 10%, 3 = 11% − 30%, 4 = 31% − 60%, 5 = more than 60%) For more information on these variables, see OECD (Citation2019, 8). Last, the hierarchical models control for institutional settings via the Human Development Index (HDI, UNDP Citation2020a).

2.3 Method

Mplus (Muthén and Muthén Citation1998–2018) and RStudio were used for analyses. Mplus automatically employs either full information maximum likelihood (FIML) or multiple imputation (in the case of Bayesian analysis) to deal with missing values. In RStudio, multivariate imputation by chained equation (the ‘mice’ package, van Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn Citation2011) was conducted to account for missing variables into a newly imputed complete dataset. As auxiliary variables, the imputation model included dummy variable for each education system, school socioeconomic composition, location, type, as well as teacher characteristics including age, gender, experience, subject matter, self-efficacy, job-satisfaction and social-utility value.

For the first research question, for each country the relationship between classroom socioeconomic composition and a teacher’s odds of wishing to change schools is examined. For this, individual logistic regression models are run in RStudio with the ‘glm’ function, clustering the standard errors by school (Abadie et al. Citation2017) using the ‘ClubSandwich’ package (Pustejovsky Citation2021) and the heteroscedasticity consistent ‘CR0’ variance estimator to account for the nested data structure. The model is as follows:

Where refers to whether the teacher i in school j wishes to change schools and coefficient

.

refers to the socioeconomic composition of a classroom,

the teacher controls, and δ the school controls. Estimates are reported in odds ratios alongside the 95% confidence intervals. The odds ratios minus 1 divided by their standard errors (the t-value) is taken to plot the estimates alongside the country-level accountability measures.

For the final two research questions, three-level generalized regressions are estimated in Mplus (type = ‘THREELEVEL RANDOM’) following a cumulative model building procedure (Raudenbush and Bryk Citation2002; Sommet and Morselli Citation2017). The intra-class correlation coefficient of the dependent variable is 0.05. The model of interest estimates whether the relationship between wishing to change schools and classroom SES (the random slope) varies as a function of school-system level accountability practices:

Where the probability () that a teacher i in school j in country k wishes to change schools is estimated as a function of the overall likelihood that teachers wish to change schools across countries (α), classroom SES (

, teacher-level controls (

, school level controls (δ), country HDI (θ), and country-level accountability (π). The model includes a cross-level interaction (σ), a random effect at the school level (

and a random slope and intercept at the country-level (

As the system level variables represent the percentage of schools where teacher appraisal based on achievement-data is conducted externally or by the school management team, there is no need to center. Random slope models are quite useless if effects move in opposite directions, resulting in a null effect. Within-country two-level models are also estimated for this reason, and these results can be found in the Appendix. In a final step, the model is estimated again for subsamples of the teacher population: by gender, novice status, subject matter taught (mathematics/science against all other subjects), and whether their appraisal has consequences such as dismissal, financial bonus, or sanctions.

While there is debate about the usefulness of comparing educational systems which necessarily have a host of unobservable cultural and demographic differences (Nóvoa and Yariv-Marshal, 2003; Strietholt et al. Citation2019), educational policies often lack sufficient variability within countries, thereby complicating their assessment (Strietholt et al. Citation2014). Unobservable selection effects at school- and student-levels can also be accounted for when aggregating institutional variables to the country level, such as if a certain type of school is targeted for external teacher appraisal. Nevertheless, although the models control for HDI, it must be stressed that the results are correlational, and that other system-level unobserved variables may be present.

3 Results

3.1 Inequitable teacher turnover intentions within countries

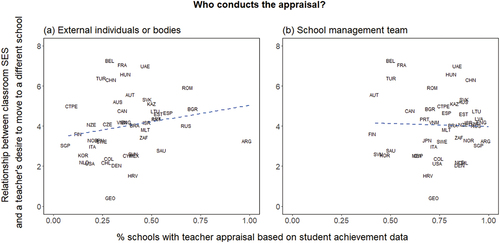

The first research question estimates the odds of a teacher wishing to change to a different school as a function of classroom socioeconomic composition for each country, with characteristics such as location and school type under control. illustrates this relationship.

Figure 2. Teacher turnover intentions and classroom socioeconomic composition .

In , countries are ranked by the size of their odds ratios. An odds ratio of 1 implies that a teacher is just as likely to wish to change schools at all levels of SES classroom composition (i.e. the null hypothesis). An odds ratio of 1.10 (such as in Japan or Portugal) signifies that the odds of a teacher wishing to change schools increase by 10 percentage points for every unit increase on the class SES disadvantage scale. By and large, a majority of education systems save for 11 (Georgia, Colombia, Sweden, Mexico, Italy, Japan, Brazil, Denmark, Norway, Croatia and Lithuania) display statistically significant odds ratios above 1. The educational systems with negligible relations between socioeconomic composition and teacher turnover intentions do not have any immediately obvious unifying characteristics, highlighting the fact that the determinants of teacher mobility are complex and not straightforwardly predicted.

The standard errors account for the hierarchical sample design by using a heteroskedasticity consistent variance estimator and clustering the standard errors at the school level. It should be highlighted that the estimates are displayed alongside very large confidence intervals and therefore a high degree of uncertainty. Nevertheless, the results confirm findings from national studies and demonstrate that socioeconomically motivated teacher turnover intentions are indeed a problem in most educational systems. The median odds ratio in the sample was 1.22 (Austria). Georgia (.95) and Colombia (1.02) displayed the smallest increases in odds as a function of each unit increase in classroom SES, while Romania (1.56), Latvia (1.51) and Canada (Alberta) (1.55) displayed the largest increases in odds as a function of classroom socioeconomic composition.

3.2 School system-level accountability as a moderating factor

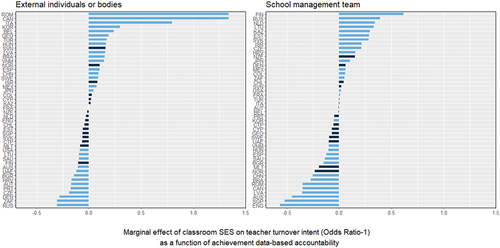

Based on the above findings, it is clear that few education systems (out of the pool of 46) have managed to avoid the problem of teacher turnover intent altogether. Is this relationship stronger in school systems with more performance-based teacher appraisal? displays the cross-national relationship between classroom SES-teacher turnover intent and the percentage of schools which practice teacher appraisal based on performance data.

Figure 3. Cross-national relationships between accountability and classroom SES-based turnover intentions.

At first glance, it appears that the main focus of this paper (the link between performance data-based teacher appraisal and teacher turnover intentions in low-SES contexts) is only confirmed in the cases where teacher appraisal is carried out externally (by school inspectors or government representatives, for example). Education systems show considerable differences in within-country variability depending on who conducts the teacher appraisal. In most education systems, a majority of schools appraise teachers according to performance data via the school management team. There are a few exceptions to this, including Finland, Austria, Slovenia, and South Korea, in which less than half of schools practice this type of appraisal. In contrast, much fewer educational systems practice performance data-based appraisal via external actors. Argentina (Buenos Aires), Bulgaria, Romania and Russia display the most widespread use. Although selection effects exist at the school level (for instance, if certain teachers are monitored for unobservable reasons endogenously related to teacher turnover intentions), these are removed accountability practices are aggregated to the system-level and turnover intention rates across countries are the subject of analysis. From , I conclude that the turnover-classroom SES relationship is positively related to the system level of external accountability. Inequitable turnover intentions are more frequent in countries where teacher practices are monitored externally using student performance data.

Three-level regressions then model this relationship empirically. displays the estimates from this model where turnover intentions are regressed on classroom socioeconomic composition (at the classroom level), controlling for the Human Development Index at the system-level. shows that for each added level of socioeconomic disadvantage, the odds of wishing to change to a different school increases. However, it does not seem to matter whether there are more than 30 percent of socioeconomically disadvantaged students in the classroom or more than 60 percent, as the odds ratios are not significantly different at the 95% level.

Figure 4. Three-level generalized linear estimates of teachers turnover intentions on classroom socioeconomic composition.

The findings so far demonstrate a clear link between turnover intentions and classroom socioeconomic composition that is found in a majority of the within-country logistic regressions and is also generalizable across the countries in the TALIS sample. Does this relationship hold when additional controls are added into the model? Moving to the successive hierarchical model results conducted in Mplus, shows the cumulative models and estimates for research questions 2a and 2b, which ask primarily whether the relationship between classroom SES and teacher turnover intent differs as a function of school accountability after including teacher level controls such as gender, experience, subject specialization, job satisfaction and self-efficacy, and school level controls such as school location, type, and socioeconomic composition. The point estimates represent the median of the posterior probability distributions for each parameter.

Table 2. Estimates from successive three-level generalized models.

Model 1 () shows that the effect of one unit increase in the classroom socioeconomic composition scale equates to about a 0.14 probability increase in turnover intentions averaged across all countries in the sample. In addition, novice teachers are significantly more likely to wish to change schools, as are teachers without a specialization in the subject matter they currently teach. Teachers with higher levels of self-efficacy were also more likely to wish to change schools, and there was an inverse relationship between job satisfaction and a teacher’s turnover intent. Moving to the school level, in line with the main hypothesis of this paper, teachers were more likely to report that they wish to change schools if a school had a higher proportion of low-SES students, and if they worked in a rural school. These results suggest that classroom socioeconomic composition matters alongside school characteristics.

Model 2 () shows the same three-level model, this time with the addition of a random slope (the relationship between classroom SES and teacher turnover intent). The variance of the random slope in model 2 varies significantly across education systems and therefore the estimation proceeds to the next step. In the final model (model 3) in , the cross-level interactions are introduced, where the level one slope is regressed on the level three predictor variables of those responsible for teacher appraisal based on student-achievement data and HDI. The results confirm the findings depicted in . In other words, they confirm that the effect of classroom SES on teacher turnover intent is stronger in school systems where teacher appraisal based on student achievement data is conducted externally. The coefficient represents a median probability increase of about 0.11 increasewith each classroom SES disadvantage category. Similar to the plot in , there was no change in the marginal effect in relation to teacher appraisal based on student achievement data conducted by the school management team. However, the relationship between classroom SES and teacher turnover intent was also stronger in higher-HDI countries. . Here, the median probability increase in the slope as a function of HDI was about 0.25. Last, the variance of the slope remains statistically significant in Model 3, which suggests that factors not captured by the model are relevant for explaining the slope variation.

To further investigate the null results for accountability conducted by the school management team, within-country models are estimated for this same research question (with school-level accountability). These results are in in the Appendix, and confirm that the relationship is both positive and negative and therefore no general cross-national pattern can be assumed.

3.3 Teacher characteristics and school consequences of appraisal

The three-level hierarchical generalized models are then re-run for different sub-groups of the data, by school-level consequences of formal teacher appraisal (dismissal, salary changes, and sanctions following formal teacher appraisal, see ), as well as by certain teacher characteristics (gender, experience, and subject area, see ). Only the estimates of the random slope regressed on teacher appraisal actors and HDI are presented here. For full cumulative models for each subgroup see in the Appendix. shows teachers who work in schools where formal teacher appraisal may have serious consequences for their careers. In each case, the estimates are positioned in contrast to those where such consequences are not a part of school practice. The relationship between the random slope and school accountability practices only varies in a few cases. There is a positive association between external teacher appraisal and the slope in schools where dismissal is not a consequence of teacher appraisal, especially in higher HDI countries. There is no difference in the relationship between accountability and the slope between teachers in schools with financial bonuses or sanctions. shows the model run for sub-groups based on teacher gender, experience, and subject matter. The positive moderating effect of external teacher appraisal on the random slope was larger for male teachers than for female teachers. Teachers with more than five years of experience were also more likely to report wishing to leave the school in school systems with more external teacher appraisal. Finally, there was no significant difference between teachers of mathematics and science teachers and teachers of other subjects.

Table 3. Estimates from three-level random slope models by school consequence subgroup.

Table 4. Estimates from three-level random slope models by teacher characteristic subgroup.

4 Discussion

Educational scholars of different backgrounds contest the role of performance-based accountability practices such as the formal appraisal of teacher effectiveness based on student test scores, but such practices continue to become more widespread. While some report on and advocate for the benefits of accountability in the school system for student learning (Figlio and Loeb Citation2011; Hanushek and Raymond Citation2005), others relay the potential risks of an unchecked focus on performance, particularly for teachers (Ball Citation2003; Darling-Hammond Citation2004; Ryan et al. Citation2017; Valli and Buese Citation2007). Increased accountability may lead to increased workload and a diminished sense of professional well-being and autonomy (Valli and Buese Citation2007). Despite this debate, student achievement-based accountability practices are becoming more widely practiced on a global scale. Jerrim and Sims (Citation2021) recently found a modest link between school system-level accountability and the degree of teacher and principal stress cross-nationally, and Smith and Holloway (Citation2020) find a link between performance data-based teacher appraisal and job satisfaction. This study expanded upon this line of questioning and confirmed that higher levels of performance data-based accountability are also linked to teachers’ intentions of changing schools, particularly if they are working in lower-SES environments. There is also an interest as to whether this effect varied across subgroups based on different school consequences of the appraisal and different teacher characteristics. Ultimately, this study is a first step in the cross-national investigation of the policy-level correlates of teacher attrition and turnover.

The results from the three-level models show that the marginal effect of classroom SES on a teacher’s turnover intent increases as a function of system-level accountability. However, this was only found for external appraisal.Footnote8 There was no difference in the association in school systems with higher levels of achievement-based teacher appraisal conducted by the school management team. In general, this finding also supports a clearer distinction between internal and external accountability as outlined previously by Vanhoof and van Petegem (Citation2007). External monitoring may not be achieving its intended consequence when it comes to appraisal. The first implication, therefore, is to limit appraisal to those with knowledge of the particular school context. Past work has suggested that principals may play a mediating role between school goals and external monitoring (Qian and Walker Citation2019). As such, teacher appraisal conducted by the school management team (which often involves the principal) may have a more ‘sincere’ and constructive quality (Qian and Walker Citation2019). Furthermore, Ehren, Paterson and Baxter (2019) outline several ways in which low levels of trust intertwine with accountability policies. First, a lack of expertise on the part of external monitors, second, a misunderstanding and lack of support for why educational actors fail to meet targets, and third, a lack of a shared sense of purpose and view regarding the accountability exercise.

There was also a difference in the marginal effect of classroom SES on teacher turnover intent (the slope) as a function of HDI, or the level of economic and social development in a country. This signifies that teachers in low-SES classrooms were more likely to report wishing to change schools if they lived in more economically developed countries. Past work from Chile has pointed out that in some cases, teachers in lower-SES settings are more likely to stay put throughout their careers (Meckes and Bascope Citation2012). This may be due to a lack of job opportunities in more remote (and often lower-income) settings, but it could also be – as mentioned earlier – that a greater proportion of teachers in higher-income countries enter the profession with intentions to change to more desirable educational settings later in their careers.

Regarding the analyses across subgroups, there was a mostly null pattern of results, with a few exceptions. The anti-compensatory relationship between accountability and teacher attrition was stronger for teachers in schools where dismissal was not a consequence of appraisal. There were no significant results regarding either financial bonus or material sanctions. These results were somewhat surprising, as the possibility of dismissal may entail a more punitive, high-stakes (and stressful) working environment. In such a case, we would expect to see a stronger relationship between the slope and system level accountability in schools where dismissal or material sanctions were imposed. However, Jerrim and Sims (Citation2021) similarly found that facing dismissal did not predict a stronger relationship between accountability and teacher stress cross-nationally. It could be that schools less likely to fire teachers as a consequence of their appraisal have greater issues related to teacher retention and hiring in the first place as compared to schools where firing is common practice. In this way, there may be some unobserved characteristics associated with the variables related to school consequences. There may also be an important mediating role of the perceived pressure of accountability mechanisms and past work has found that schools experience pressure differently (Verger, Ferrer-Esteban, and Parcerisa Citation2021). By breaking down each subgroup by school consequence, associations between turnover intentions and other school characteristics across contexts can be observed. For instance, in Model 2a (Appendix), the association between turnover intentions and school socioeconomic composition and location (rural or remote) remains despite the presence of financial bonus as a possible consequence of appraisal, indicating these are not sufficient to eliminate such potential turnover determinants. Last, female teachers are slightly less likely to report wishing to change schools than male teachers when sanctions are used as a consequence of appraisal.

A noteworthy finding in the teacher characteristic subgroup analyses demonstrated that experienced teachers were more likely to report wishing to change schools in higher accountability systems. This finding was also surprising, given that it goes against some past evidence on general patterns of teacher turnover (Fantilli and Macdougall Citation2009; Hanushek and Rivkin Citation2010b, Citation2010a; Ingersoll Citation2001; Marinell et al. Citation2013; Ryan et al. Citation2017), although these data largely come from a single country (the USA). As Hanushek and Rivkin (Citation2010b) point out, if more stringent accountability practices in socioeconomically disadvantaged schools tend to push out the least effective teachers, it could indeed be a positive thing for students if schools are able to replace them with better teachers. However, our findings are more in line with those of Feng, Figlio, and Sass (Citation2018) who find that accountability pushes out more experienced teachers. Given the link between teacher competence and experience after the first few years on the job (Rice Citation2003), this finding has negative implications for socioeconomically disadvantaged students in higher-accountability systems.

4.1 Limitations

There are several limitations to this analysis which constrain the findings. First, the findings may be vulnerable to selection effects at the system-level. For instance, school-systems with more challenging teaching conditions or a lower-quality teacher workforce may be more ‘in need’ of and therefore likely to implement external accountability checks. However, this is somewhat unlikely as the models control for HDI, but not every possible confounding factor can be accounted for related to the teacher job market and micro mobility. There was also a considerably higher amount of variation regarding the external accountability measure at the system level as compared to the school management team accountability measure.

It is again worth stressing that the findings are correlational. As such, no causal claims can be made of the present analysis or of the focused upon research questions. However, it does suggest a relationship between the two which warrants further investigation by researchers and policymakers alike. Although the results suggest that teacher attrition issues may be more prevalent in systems where their appraisal is conducted based on student-achievement data externally, the within-country results show that this is not the case for all education systems. In these models ( in Appendix), lower-level selection effects may be present, as schools with ‘school management teams’ may be more or less attractive to teachers than those with external accountability monitors for other unobserved reasons. Nationally-focused research will better answer such remaining questions.

5 Conclusions

While more research will need to replicate the findings with other data sources and variables, this study does have several preliminary implications for educational policymakers. Although the heterogeneity seen in the within-country analyses show that it is difficult to generalize without caveat the relationship between accountability and teacher turnover intentions across education systems, the pattern for external appraisal suggests a global trend. As pointed out by past work (Ball Citation2003; Jerrim and Sims Citation2021; Lee and Wong Citation2003), the long-run effects of increasing external accountability may not be obviously detrimental to students via clear-cut achievement changes but may hurt certain students on a larger scale via inequitable learning opportunities through issues with teacher attrition.

Monitoring teacher and school effectiveness via testing and performance data is repeatedly touted as a type of equalizer with regards to ‘quality assurance’ in schools (OECD Citation2021). In practice, such approaches likely further entrench educational inequities in many cases given that raising student achievement is much more difficult when students have lower levels of home educational resources and if accountability mechanisms are uncoupled from the local educational context. This study has provided new evidence that such regimes are more likely to push teachers out of more challenging educational settings. Policymakers may need to rethink the use of student performance results in the appraisal of teacher performance in socioeconomically disadvantaged schools and classrooms in favour of other forms of feedback. Moreover, appraisal and feedback should sooner come from those with more contextual school knowledge – such as the school principal or other teachers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Leah Natasha Glassow

Leah N Glassow is a lecturer and researcher at the Department of Education and Special Education at the University of Gothenburg. Her main research interests are in inequalities in teacher sorting and mobility, educational policy, and school equity.

Notes

1. The term ‘standards’-based reforms also refers to this type of accountability in the context of this study.

2. For more on accountability typologies, see Maroy and Voisin (2017).

3. Measured by value-added.

4. Turnover intentions is part of this scale.

5. Although these weights are computed, their use in Mplus is restricted as Mplus employs a Bayesian estimator for three-level models with categorical outcomes. In order to determine that our estimates are not biased by differing sample sizes within countries, a system-level variable is added indicating sample size and the slope regressed on this new variable. The slope is unrelated to the sample size in each country.

6. TALIS distinguishes between job satisfaction at the current school and job satisfaction with the profession. To control for whether teachers have a general feeling with the profession overall, we include the job satisfaction with the profession as a control.

7. Educational systems displayed almost zero within-country variability when appraisal was conducted by the principal.

8. Supplemental analyses (Appendix B) shows that this conclusion is not without caveat.

References

- Abadie, A., S. Athey, G.W. Imbens, and J. Wooldridge 2017. When Should You Adjust Standard Errors for Clustering? NBER Working Paper 24003.

- Allen, R., S. Burgess, and J. Mayo. 2018. “The Teacher Labour Market, Teacher Turnover and Disadvantaged Schools: New Evidence for England.” Education Economics 26 (1): 4–23. doi:10.1080/09645292.2017.1366425.

- Allensworth, E., S. Ponisciak, and C. Mazzeo. 2009. “The Schools Teachers Leave: Teacher Mobility in Chicago Public Schools.” Consortium on Chicago School Research 1–52.

- Ball, S. 2003. “The Teacher’s Soul and the Terrors of Performativity.” Journal of Education Policy 18 (2): 215–228. doi:10.1080/0268093022000043065.

- Ball, S. 2016. “Neoliberal Education? Confronting the Slouching Beast.” Policy Futures in Education 14 (8): 1046–1059. doi:10.1177/1478210316664259.

- Barbana, S., X. Dumay, and V. Dupriez. 2020. “Accountability Policy Forms in European Education Systems: An Introduction.” European Educational Research Journal 19 (2): 87–93. doi:10.1177/1474904120907252.

- Berryhill, J., J. A. Linney, and J. Fromewick. 2009. “The Effects of Education Accountability on Teachers: Are Policies Too Stress Provoking for Their Own Good?” International Journal of Education Policy and Leadership 4 (5): 1–14. doi:10.22230/ijepl.2009v4n5a99.

- Biesta, G. 2007. “Education, Accountability, and the Ethical Demand: Can the Democratic Potential of Accountability Be Regained?” Educational Theory; Urbana 54 (3): 233 250. doi:10.1111/j.0013-2004.2004.00017.x.

- Bonesrønning, H., T. Falch, and B. Strøm. 2005. “Teacher Sorting, Teacher Quality, and Student Composition.” European Economic Review 49 (2): 457–483. doi:10.1016/S0014-2921(03)00052-7.

- Bovens, M. 2007. “Analyzing and Assessing Accountability: A Conceptual Framework.” European Law Journal 13 (4): 447–468. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0386.2007.00378.x.

- Bovens, M. 2010. “Two Concepts of Accountability: Accountability as a Virtue and as a Mechanism.” West European Politics 33 (5): 946–967. doi:10.1080/01402382.2010.486119.

- Boyd, D., H. Lankford, S. Loeb, and J. Wyckoff. 2005. “Explaining the Short Careers of High Achieving Teachers in Schools with Low-Performing Students.” The American Economic Review 95 (2): 166–171. doi:10.1257/000282805774669628.

- Brill, F., H. Grayson, L. Kuhn, and S. O’donnell. 2018. What Impact Does Accountability Have on Curriculum, Standards and Engagement in Education? A Literature Review. Slough: National Foundation for Educational Research.

- Browes, N. 2021. “Test-Based Accountability and Perceived Pressure in an Autonomous Education System: Does School Performance Affect Teacher Experience?” Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability 33 (3): 483–509. doi:10.1007/s11092-021-09365-9.

- Byrd-Blake, M., M. Alofayan, J. Hunt, M. Fabunmi, B. Pryor, and R. Leander. 2010. “Morale of Teachers in High-Poverty Schools: A Post-NCLB Mixed Methods Analysis.” Education and Urban Society 42 (4): 450–472. doi:10.1177/0013124510362340.

- Carver-Thomas, D., and L. Darling-Hammond 2017. Teacher Turnover: Why It Matters and What We Can Do About It. Report from the Learning Policy Institute.

- Craig, C. 2017. “International Teacher Attrition: Multiperspective Views.” Teachers and Teaching 23 (8): 859–862. doi:10.1080/13540602.2017.1360860.

- Darling-Hammond, L. 1997. Doing What Matters Most: Investing in Quality Teaching. New York: National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future.

- Darling-Hammond, L. 2000. “Teacher Quality and Student Achievement: A Review of State Policy Evidence.” Educational Policy Analysis Archives 8: 1–44. doi:10.14507/epaa.v8n1.2000.

- Darling-Hammond, L. 2004. “Standards, Accountability, and School Reform.” Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education 106 (6): 1047–1085. doi:10.1177/016146810410600602.

- Elacqua, G., D. Hincapie, and M. Martinez 2019. The Effects of the Chilean School Accountability System on Teacher Turnover. IDB Working Paper Series Number 1075.

- Falch, T. 2011. “Teacher Mobility Responses to Wage Changes: Evidence from a Quasi Natural Experiment.” The American Economic Review 101 (3): 460–465. doi:10.1257/aer.101.3.460.

- Fantilli, R.D., and D.E. Macdougall. 2009. “A Study of Novice Teachers: Challenges and Supports in the First Years.” Teaching and Teacher Education 25 (6): 814–825. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2009.02.021.

- Feng, L. 2009. “Opportunity Wages, Classroom Characteristics, and Teacher Mobility.” Southern Economic Journal 75 (4): 1165–1190. doi:10.1002/j.2325-8012.2009.tb00952.x.

- Feng, L., D. Figlio, and T. Sass. 2018. “School Accountability and Teacher Mobility.” Journal of Urban Economics 103: 1–17. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2017.11.001.

- Figlio, D., and S. Loeb. 2011. “School Accountability.” In Handbooks in Economics, edited by Eric A. Hanushek, Stephen Machin, and Ludger Woessmann, 383–421. Vol. 3. North-Holland: Elsevier

- Hanushek, E. A., J. F. Kain, and S. G. Rivkin. 2004. “Why Public Schools Lose Teachers.” The Journal of Human Resources 39 (2): 326–354. doi:10.2307/3559017.

- Hanushek, E.A., and M. Raymond. 2005. “Does School Accountability Lead to Improved Student Performance?” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 24: 297 327. doi:10.1002/pam.20091.

- Hanushek, E.A., and S.G. Rivkin 2010a. Constrained Job Matching: Does Teacher Job Search Harm Disadvantaged Urban Schools? NBER Working Paper w15816.

- Hanushek, E.A., and S.G. Rivkin. 2010b. “The Quality and Distribution of Teachers Under the No Child Left Behind Act.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 24 (3): 133–150. doi:10.1257/jep.24.3.133.

- Hanushek, E.A., S.G. Rivkin, and J.C. Schiman. 2016. “Dynamic Effects of Teacher Turnover on the Quality of Instruction.” Economics of Education Review 55: 132–148. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2016.08.004.

- Hattie, J. 2003. Teachers Make a Difference, What is the Research Evidence? https://research.acer.edu.au/research_conference_2003/4

- Holloway, J., T.B. Sørensen, and A. Verger. 2017. “Global Perspectives on High-Stakes Teacher Accountability Policies: An Introduction.” Education Policy Analysis Archives 25: 85. doi:10.14507/epaa.25.3325.

- Ingersoll, R.M. 2001. “Teacher Turnover and Teacher Shortages: An Organizational Analysis.” American Educational Research Journal 38 (3): 499–534. doi:10.3102/00028312038003499.

- Ingersoll, R.M. 2002. Who Controls teachers’ Work. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Jerrim, J., and S. Sims. 2021. “School Accountability and Teacher Stress: International Evidence from the OECD TALIS Study.” Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability 34 (1): 5–32. doi:10.1007/s11092-021-09360-0.

- La Londe, P. G. 2017. “A Failed Marriage Between Standardization and Incentivism: Divergent Perspectives on the Aims of Performance-Based Compensation in Shanghai, China.” Education Policy Analysis Archives 25: 88. doi:10.14507/epaa.25.2891.

- Lazear, E.P. 2001. “Educational Production.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 126 (3): 777–803. doi:10.1162/00335530152466232.

- Lee, J., and K.K. Wong. 2003. “The Impact of Accountability on Racial and Socioeconomic Equity: Considering Both School Resources and Achievement Outcomes.” American Educational Research Journal 41 (4): 797–832. doi:10.3102/00028312041004797.

- Marinell, W.J., Coca, VM. 2013. Who Stays and Who Leaves? Findings from a Three-Part Study of Teacher Turnover in NYC Middle Schools. New York: The Research Alliance for New York City Schools: New York University.

- Maroy, C., and A. Voisin 2017. THINK PIECE on ACCOUNTABILITY: Think Piece on Accountability Background Paper Prepared for the 2017/8 Global Education Monitoring Report. [Research Report] UNESCO. 2017. halshs-01705982

- McNaughton, S., M. Lai, and S. Hsaio. 2012. “Testing the Effectiveness of an Intervention Model Based on Data Use: A Replication Series Across Clusters of Schools.” School Effectiveness and School Improvement 23 (2): 203–228. doi:10.1080/09243453.2011.652126.

- Meckes, L., and M. Bascope. 2012. “Uneven Distribution of Novice Teachers in the Chilean Primary School System.” Educational Policy Analysis Archives 20: 1–27. doi:10.14507/epaa.v20n30.2012.

- Muthén, L. K., and B. O. Muthén. 1998-2018. Mplus User’s Guide. Sixth ed Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

- Nilsen, T., and J.E. Gustafsson. 2016. Teacher Quality, Instructional Quality, and Student Outcomes: Evidence Across Countries, Cohorts, and Time. Hamburg: Springer Open and IEA.

- OECD. 2013a. School Governance, Assessments and Accountability. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- OECD. 2013b. Teachers for the 21st Century: Using Evaluation to Improve Teaching. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- OECD. (2019). TALIS 2018 technical report (pp12): OECD Publishing.

- OECD. (2021). Education GPS: Teacher Appraisal. Taken from: https://gpseducation.oecd.org/revieweducationpolicies/#!node=&filter=all

- Özoğlu, M. 2015. “Mobility-Related Teacher Turnover and the Unequal Distribution of Experienced Teachers in Turkey.” Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice 15: 891–909.

- Perryman, J., and G. Calvert. 2020. “What Motivates People to Teach, and Why Do They Leave? Accountability, Performativity and Teacher Retention.” British Journal of Educational Studies 68 (1): 3–23. doi:10.1080/00071005.2019.1589417.

- Peters, B., and F. van Nispen. 1998. Public Policy Instruments: Evaluating the Tools of Public Administration (New Horizons in Public Policy). Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Pizmony-Levy, O., and A. Woolsey. 2017. “Politics of Education and teachers’ Support for High-Stakes Teacher Accountability Policies.” Education Policy Analysis Archives 25: 87. doi:10.14507/epaa.25.2892.

- Polesel, J., S. Rice, and N. Dulfer. 2013. “The Impact of High-Stakes Testing on Curriculum and Pedagogy: A Teacher Perspective from Australia.” Journal of Education Policy 9 (5): 640–657. doi:10.1080/02680939.2013.865082.

- Pustejovsky, J. 2021. Cluster-Robust (Sandwich) Variance Estimators. CRAN. R-project.

- Qian, H., and A. Walker. 2019. “Reconciling Top-Down Policy Intent with Internal Accountability: The Role of Chinese School Principals.” Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability 31: 495–517. doi:10.1007/s11092-019-09309-4.

- Raudenbush, S. W., and A. S. Bryk. 2002. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Rice, J. 2003. Teacher Quality: Understanding the Effectiveness of Teacher Attributes. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute.

- Richards, S. 2012. “Teacher Stress and Coping Strategies: A National Spanshot.” The Education Forum 76 (3): 299–316. doi:10.1080/00131725.2012.682837.

- Rivas, A., and B. Sanchez. 2022. “Race to the Classroom: The Governance Turn in Latin American Education. The Emerging Era of Accountability, Control and Prescribed Curriculum.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 52 (2): 250–268. doi:10.1080/03057925.2020.1756745.

- Rivkin, S.G., E.A. Hanushek, and J.F. Kain. 2005. “Teachers, Schools, and Academic Achievement.” Econometrica 73 (2): 417–458. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0262.2005.00584.x.

- Ryan, S.V., N.P. von der Embse, L.L. Pendergast, E. Saeki, N. Segool, and S. Schwing. 2017. “Leaving the Teacher Profession: The Role of Teacher Stress and Educational Accountability Policies on Turnover Intent.” Teaching and Teacher Education 66: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2017.03.016.

- Sass, D.A., A.K. Seal, and N.K. Martin. 2011. “Predicting Teacher Retention Using Stress and Support Variables.” Journal of Educational Administration 49 (2): 200–215. doi:10.1108/09578231111116734.

- Scafidi, B., D. L. Sjoquist, and T. R. Stinebrickner. 2007. “Race, Poverty, and Teacher Mobility.” Economics of Education Review 26 (2): 145–159. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2005.08.006.

- Schidkamp, K. 2019. “Data-Based Decision-Making for School Improvement: Research Insights and Gaps.” Educational Research 61 (3): 257–273. doi:10.1080/00131881.2019.1625716.

- Sims, S., and R. Allen. 2018. “Do Pupils from Low-Income Families Get Low-Quality Teachers? Indirect Evidence from English Schools.” Oxford Review of Education 44 (4): 441–458. doi:10.1080/03054985.2017.1421152.

- Skilbeck, M., and H. Connell. 2003. Attracting, Developing Effective Teachers: Australian Country Background Report. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Smith, W.C., and J. Holloway. 2020. “School Testing Culture and Teacher Satisfaction.” Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability 32 (4): 461–479. doi:10.1007/s11092-020-09342-8.

- Smith, W.C., and K. Kubacka. 2017. “The Emphasis of Student Test Scores in Teacher Appraisal Systems.” Educational Policy Analysis Archives 25: 86. doi:10.14507/epaa.25.2889.

- Sommet, N., and D. Morselli. 2017. “Keep Calm and Learn Multilevel Logistic Modeling: A Simplified Three-Step Procedure Using Stata, R, Mplus, and SPSS.” International Review of Social Psychology 30 (1): 203–218. doi:10.5334/irsp.90.

- Sorensen, L.C., and H.F. Ladd. 2020. “The Hidden Costs of Teacher Turnover.” AERA Open 6 (1): 233285842090581. doi:10.1177/2332858420905812.

- Strietholt, R., W. Bos, J.E. Gustafsson, and M. Rosén. 2014. Educational Policy Evaluation Through International Comparative Assessments. New York: Waxmann.

- Strietholt, R., J.E. Gustafsson, N. Hogrebe, and V. Rolfe. 2019. “The Impact of Education Policies on Socioeconomic Inequality in Student Achievement: A Review of Comparative Studies.” In Socioeconomic Inequality and Student Outcomes: Cross-National Trends, Policies, and Practices, edited by Louis Volante, Sylke V. Schnepf, John Jerrim, and Don A. Klinger, 17–38, Singapore: Springer.

- UNDP 2020a. Human Development Report 2020: Reader’s guide. http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-report-2020-readers-guide

- UNDP 2020b. Methodology updates. http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdr2020_technical_notes.pdf.

- UNESCO. 2015a. Rethinking Education. Towards a Global Common Good?. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2015b. Education 2030. In Framework for Action: UNESCO. https://www.sdg4education2030.org/sdg-education-2030-steering-committee-resources.

- UNESCO 2017. Accountability in Education: Meeting Our Commitments. Global Education Monitoring Report: UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000259338.page=22

- Vagi, R., and M. Pivovarova. 2017. ““Theorizing Teacher mobility”: A Critical Review of Literature.” Teachers and Teaching 23 (7): 781–793. doi:10.1080/13540602.2016.1219714.

- Valli, L., and D. Buese. 2007. “The Changing Roles of Teachers in an Era of High-Stakes Accountability.” American Educational Research Journal 44 (3): 519–558. doi:10.3102/0002831207306859.

- van Buuren, S., and K. Groothuis-Oudshoorn. 2011. “Mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R.” Journal of Statistical Software 45 (3): 1–67. doi:10.18637/jss.v045.i03.

- van Geel, M. J. M., T. Keuning, A. J. Visscher, and G. J. A. Fox. 2016. “Assessing the Effects of a School-Wide Data-Based Decision-Making Intervention on Student Achievement Growth in Primary Schools.” American Educational Research Journal 53 (2): 360–394. doi:10.3102/0002831216637346.

- Vanhoof, J., and P. van Petegem. 2007. “Matching Internal and External Evaluation in an Era of Accountability and School Development: Lessons from a Flemish Perspective.” Studies in Educational Evaluation 33 (2): 101–119. doi:10.1016/j.stueduc.2007.04.001.

- Verger, A., G. Ferrer-Esteban, and L. Parcerisa. 2021. “In and Out of the ‘Pressure cooker’: Schools’ Varying Responses to Accountability and Datafication.” In World Yearbook of Education 2021: Accountability and Datafication in the Governance of Education, edited by Sotiria Grek, Christian Maroy, and Antoni Verger. New York: Routledge 219–239 .

- Verger, A., C. Fontdevila, and L. Parcerisa. 2019. “Reforming Governance Through Policy Instruments: How and to What Extent Standards, Tests and Accountability in Education Spread Worldwide.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 40 (2): 248–270. doi:10.1080/01596306.2019.1569882.

- Verger, A., L. Parcerisa, and C. Fontdevila. 2018. “The Growth and Spread of Large-Scale Assessments and Test-Based Accountabilities: A Political Sociology of Global Education Reforms.” Educational Review 71 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1080/00131911.2019.1522045.

- von der Embse, N., L.E. Sandilos, L. Pendergast, and A. Mankin. 2016. “Teacher Stress, Teaching-Efficacy, and Job Satisfaction in Response to Test-Based Educational Accountability Policies.” Learning and Individual Differences 50: 308–317. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2016.08.001.

- Wong, M., T. Cook, and P. Steiner 2010. No Child Left Behind: An Interim Evaluation of Its Effects on Learning Using Two Interrupted Time Series Each with Its Own Non- Equivalent Comparison Series. Northwestern University Working Paper.

Appendix

Table A1. Descriptive statistics.

Table C1. Teacher characteristics.

Table C2. School consequences of appraisal.

Figure B.

Note. Figure represents the coefficients for the interaction term classroom SES * achievement-based teacher appraisal (a dummy) regressed on teacher turnover intent. Statistically significant estimates shown in blue. Argentina and Norway are excluded due to no within-system variation in certain cases. Figure B shows the estimates from the within-country two-level logistic models. In these models, control variables include teacher gender, experience, self-efficacy, job satisfaction, school location, type, and socioeconomic composition. Positive estimates indicate an anti-compensatory general moderating effect of achievement-based teacher appraisal on SES-based turnover. The estimates are depicted as odds ratios minus one, and therefore signify marginal increases or decreases in the odds of wishing to change schools in percentage points. This is a random-intercepts model only, as in the majority of education systems, the teacher mobility intentions-classroom SES slope did not vary as a function of accountability at the school level.