Abstract

Objective

Short-acting β2-agonist (SABA) over-reliance is associated with poor asthma outcomes. As part of the SABA Use IN Asthma (SABINA) III study, we assessed SABA prescriptions and clinical outcomes in patients from six Latin American countries.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, data on disease characteristics/asthma treatments were collected using electronic case report forms. Patients (aged ≥12 years) were classified by investigator-defined asthma severity (guided by the 2017 Global Initiative for Asthma) and practice type (primary/specialist care). Multivariable regression models analyzed the associations between SABA prescriptions and clinical outcomes.

Results

Data from 1096 patients (mean age, 52.0 years) were analyzed. Most patients were female (70%), had moderate-to-severe asthma (79.4%), and were treated by specialists (87.6%). Asthma was partly controlled/uncontrolled in 61.5% of patients; 47.4% experienced ≥1 severe exacerbation in the previous 12 months. Overall, 39.8% of patients were prescribed ≥3 SABA canisters in the preceding 12 months (considered over-prescription). SABA canisters were purchased over the counter (OTC) by 17.2% of patients, of whom 38.8% purchased ≥3 canisters in the 12 months prior. Of patients who purchased SABA OTC, 73.5% were prescribed ≥3 SABA canisters. Higher SABA prescriptions (vs. 1 − 2 canisters) were associated with an increased incidence rate of severe exacerbations (ranging from 1.31 to 3.08) and lower odds ratios of having at least partly controlled asthma (ranging from 0.63 to 0.15).

Conclusions

SABA over-prescription was common in Latin America, highlighting the need for urgent collaboration between healthcare providers and policymakers to align clinical practices with the latest evidence-based recommendations to address this public health concern.

Keywords:

Introduction

Asthma is one of the most common chronic diseases affecting over 330 million people worldwide, with increasing prevalence in many regions of the world; many patients in low- and middle-income countries do not have access to essential asthma medications (Citation1,Citation2). Asthma prevalence in Latin America is estimated at 17% (Citation3), but with wide within- and between-country differences (Citation4,Citation5), reflecting the geographical, cultural, economic, and political diversity of this region of 603 million inhabitants (Citation3). Asthma in Latin America has been associated with urbanization; adoption of a westernized lifestyle, with associated poor diet and reduced levels of physical activity; increasing industrialization and pollution; poverty; and widening socioeconomic inequalities (Citation4,Citation6–8). Despite global consensus on the goals of asthma management and availability of international treatment guidelines (Citation9), asthma remains poorly controlled in Latin America (Citation10,Citation11), particularly among the underprivileged populations living in cities (Citation4,Citation12). The causes of poor asthma control in Latin America are multifactorial, but include poor recognition of uncontrolled asthma by patients, underuse of appropriate medications, inadequate lung function monitoring and patient education, medication costs, and weak healthcare systems, including poor infrastructure and lack of access to medical care (Citation3,Citation10,Citation13,Citation14). Consequently, asthma exerts a considerable burden on patients, healthcare systems, and societies across Latin America (Citation10,Citation11,Citation14).

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are the cornerstone of maintenance asthma therapy, and since 2019, the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) has no longer recommended treatment with as-needed short-acting β2-agonists (SABAs) without concomitant ICS for patients aged ≥12 years (Citation9). Instead, GINA recommends as-needed low-dose ICS-formoterol as the preferred reliever across all therapy steps (Track 1) (Citation9). These treatment recommendations are also reflected in the updated 2020 Spanish Asthma Guidelines (GEMA) (Citation15). However, underuse of ICS is common in Latin America (Citation14,Citation16), with minimal improvements observed since the 2003 Asthma Insights and Reality in Latin America (AIRLA) survey which reported that only 6% of patients used ICS (Citation13). Indeed, results from the subsequent Latin America Asthma Insight and Management (LA AIM) survey, conducted in 2011, reported that 65% of patients felt that long-term use of maintenance medication was unnecessary in the absence of asthma symptoms and 61% believed that daily use of rescue inhalers was acceptable (Citation14). A subsequent analysis of the LA AIM survey also confirmed that use of maintenance medication had not improved across Latin American countries (Citation16). Thus, over-reliance on reliever medications, often at the expense of maintenance ICS medications, may explain the low asthma control rates in Latin America (Citation13,Citation14). Moreover, over-reliance on relievers may also increase the risk of septic shock in patients with asthma (Citation17), underscoring the need for caution when prescribing SABA relievers (Citation18). Thus, approaches to asthma management, including personalizing treatment regimens (Citation19), ensuring adequate coverage for ICS-containing medications, particularly following near-fatal exacerbations (Citation19,Citation20), facilitating appropriate referral to specialists (Citation21–23), and ensuring accurate assessment of disease control (Citation24) have been identified as key components of effective asthma care that may improve treatment outcomes.

An evaluation of asthma medication prescribing patterns, particularly the use of SABA, can assist clinicians, researchers, and healthcare policymakers in alleviating the growing burden of asthma in Latin America by advocating for a change in clinical practice and encouraging the adoption of current GINA treatment recommendations. However, the absence of comprehensive healthcare databases in Latin America has proved a major limitation and precluded an evaluation of medication trends across this continent. To address this, the SABA use IN Asthma (SABINA) International study (SABINA III) evaluated SABA prescription patterns and asthma-related outcomes across 23 countries in the Asia Pacific, Africa, the Middle East, Latin America and in Russia, using a harmonized approach, and captured clinical information through electronic case report forms. Here, we report on SABA prescription patterns in six countries from the Latin American cohort of the SABINA III study.

Methods

Study design

The methodology for SABINA III has been previously published (Citation25). This cross-sectional, multicountry, multicenter, observational study was conducted in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, and Mexico, in accordance with the recommended guidelines for observational studies (Citation26,Citation27). The primary objective was to examine SABA prescription patterns at an aggregated multicountry level in the asthma patient population. Secondary objectives were to determine the association between SABA prescriptions and health outcomes. Retrospective data were obtained from existing medical records, and patient data were collected during a study visit and entered on an electronic case report form (eCRF). Physicians entered data on exacerbation history, comorbidities, and information of medication prescriptions for asthma in the eCRF based on patient medical records. At the study visit, physicians also enquired whether patients had experienced exacerbations that were not captured in their medical records. Data for SABA over-the counter (OTC) purchase were based on patient recall and obtained directly from patients at the study visit, which was subsequently entered in the eCRF by the investigator. The study was approved by the ethics committee and institutional review board of each participating country (Supporting Information Table S1). Full details of the methodology are provided in the Supporting Information.

Table 1. Socio-demographics and disease characteristics of the SABINA III Latin American population by investigator-classified asthma severity and practice type.

Study population

Patients with asthma aged ≥12 years with ≥3 healthcare professional (HCP) consultations and medical records containing data for ≥12 months before the study visit were enrolled. Primary and specialist care potential study sites were selected using purposive sampling with the aim of obtaining a sample representative of asthma management within each participating country by a national coordinator, who also facilitated the selection of investigators.

Variables

Patients were categorized by SABA canister prescriptions (0, 1–2, 3–5, 6–9, 10–12, and ≥13 canisters) during the 12 months before the study visit, and over-prescription was defined as prescription of ≥3 SABA canisters/year (Citation28). Prescriptions for ICS canisters (alone and in combination with long-acting β2-agonists [LABAs]) in the 12 months before the study visit were categorized according to the average daily dose (low, medium, or high) (Citation29). Secondary variables included practice type (primary or specialist care), investigator-classified asthma severity (guided by GINA 2017 treatment steps) (Citation29), and asthma treatments prescribed in the previous 12 months.

Outcomes

Asthma-related health outcomes included asthma symptom control (GINA 2017 definition) (Citation29) and number of severe asthma exacerbations in the year before the study visit (per the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society recommendation) (Citation30).

Statistical analysis

The associations of SABA prescriptions with the incidence rate of severe exacerbations and odds of asthma symptom control (reference: uncontrolled asthma) were analyzed using negative binomial and logistic regression models, respectively. Patients with zero SABA prescriptions were excluded from the secondary analysis, as it was not possible to determine potential alternative reliever medications used. To ensure that the overall SABINA III study was adequately powered, the aim was to enroll up to 500 patients from each participating country, with 20 − 25 patients recruited from each participating site.

Results

Patient disposition

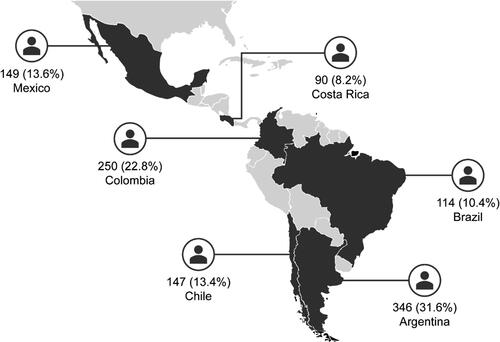

Of the 1100 patients enrolled, 1096 patients were included in the analysis and 4 were excluded because their asthma duration was less than 12 months (Supporting Information Figure S1). Most patients were recruited from Argentina (31.6%), followed by Colombia (22.8%) and Mexico (13.6%) (). The majority of patients were treated by specialists (87.6%; Supporting Information Figure S1).

Patient and disease characteristics

Overall, the mean (standard deviation [SD]) age of patients was 52.0 (16.6) years, with a similar proportion of patients aged ≥18–54 years (50.7%) and ≥55 years (48.2%). Most patients were female (70%), had a body mass index (BMI) of ≥25 kg/m2 (70.3%), and were never smokers (75.6%) (). A similar proportion of patients had primary/secondary school (46.1%) and high school/university and/or post-graduate education (50.4%). Just under half of all patients (47.1%) reported full healthcare reimbursement.

The majority of patients were classified with moderate-to-severe asthma (GINA steps 3 − 5; 79.4%). In primary and specialist care, 36.9% and 64.8% of patients, respectively, were classified by investigators as having severe asthma. Overall, across both primary and specialist care, a higher proportion of female patients compared with male patients were classified with moderate-to-severe asthma (75.7% vs. 24.3% in primary care and 70.9% vs. 29.1% in specialist care). The level of asthma symptom control was assessed as well controlled in 38.5% of patients, with a greater proportion of patients in specialist care having well-controlled asthma compared with those in primary care (39.8% vs. 30.8%). Patients reported a mean (SD) of 1.0 (1.7) severe exacerbations, with 47.4% and 12.7% experiencing ≥1 and ≥3 severe exacerbations, respectively, in the previous 12 months (). Overall, 67.8% of patients had ≥1 comorbidity.

Table 2. Asthma characteristics of the SABINA III Latin American population stratified by investigator-classified asthma severity and practice type.

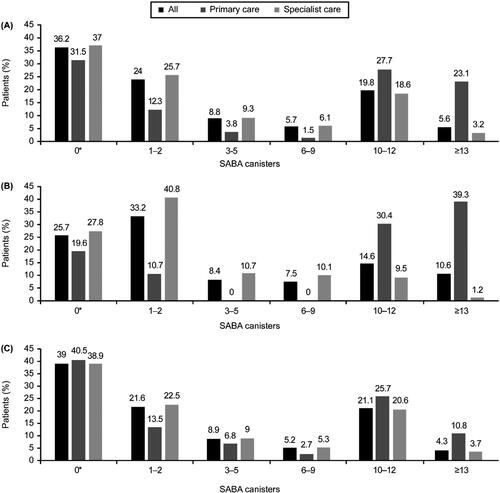

Asthma treatment in the 12 months before the study visit

Overall, 39.8% of patients were prescribed ≥3 SABA canisters in the preceding 12 months, which is regarded as over-prescription; 25.4% were prescribed ≥10 SABA canisters. Overall, 36.2% of patients received 0 SABA prescriptions (). Although only a small proportion of patients in this Latin American cohort were treated in primary care (11.8%), a higher proportion of these patients were prescribed both ≥3 and ≥10 SABA canisters (56.2% and 50.8%, respectively) compared with those in specialist care (37.3% and 21.9%, respectively). Across severities, a comparable proportion of patients with mild asthma and moderate-to-severe asthma were prescribed ≥3 SABA canisters (41.2% vs. 39.4%, respectively) and ≥10 SABA canisters (25.2% vs. 25.4%, respectively).

Figure 2. Proportion of patients receiving SABA prescriptions in the 12 months before the study visit according to investigator-classified asthma severity and practice type in the SABINA III Latin American cohort (N = 1096): (A) all patients, (B) patients with mild asthma, and (C) patients with moderate-to-severe asthma. *The category of patients classified as having 0 SABA canister prescriptions included patients using non–SABA relievers, non-inhaler forms of SABA, and/or SABA purchased OTC. OTC: over the counter; SABA: short-acting β2-agonist; SABINA: SABA use IN Asthma.

SABA monotherapy

Overall, 4.7% of patients, all of whom had mild asthma, were prescribed SABA monotherapy, with a mean (SD) of 7.2 (7.7) canisters in the previous 12 months (). Of these patients, 50% were prescribed ≥3 canisters and 34.6% were prescribed ≥10 canisters in the 12 months prior. A higher proportion of patients in primary care were prescribed SABA monotherapy compared with those treated by specialists (10% vs. 4.1%, respectively). Notably, 76.9% and 20.5% of patients were prescribed ≥10 canisters as SABA monotherapy in the preceding 12 months under primary and specialist care, respectively.

Table 3. Patients in the SABINA III Latin American cohort who (A) received prescriptions for SABA monotherapy, (B) received prescriptions for SABA in addition to maintenance therapy, and (C) purchased SABA without a prescription in the 12 months before the study visit.

SABA in addition to maintenance therapy

Overall, 59% of patients were prescribed SABA in addition to maintenance therapy in the previous 12 months, with a mean (SD) of 7.4 (7.2) canisters (). Altogether, 63.4% of patients were prescribed ≥3 canisters and 40.2% were prescribed ≥10 canisters. In primary care, 82.9% and 73.7% of patients were prescribed ≥3 and ≥10 canisters as SABA in addition to maintenance therapy, respectively, with approximately one-third of patients (30.3%) prescribed ≥13 canisters. In specialist care, 60.4% and 35.7% of patients were prescribed ≥3 and ≥10 canisters, respectively, with 5.3% receiving prescriptions for ≥13 canisters. Across disease severity, a higher proportion of patients in primary care were prescribed ≥10 canisters compared with those under specialist care (90.6% vs. 12% of patients with mild asthma and 61.4% vs. 39.8% of patients with moderate-to-severe asthma).

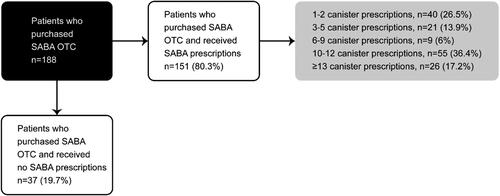

SABA obtained OTC without prescriptions

Overall, 17.2% of patients purchased SABA OTC, of whom 38.8% and 7.4% purchased ≥3 and ≥10 canisters of SABA, respectively (). Among patients who purchased SABA OTC, 80.3% were also prescribed SABA, as monotherapy or in addition to maintenance therapy (). Of patients with both SABA OTC purchase and SABA prescriptions, 73.5% were prescribed ≥3 SABA canisters, with 53.6% prescribed ≥10 SABA canisters in the preceding 12 months. Patients treated in primary care had more SABA OTC purchases than those in specialist care (29.2% vs. 15.6%, respectively).

Prescriptions of asthma maintenance medication

Overall, 24.2% of patients were prescribed ICS, with a mean (SD) of 11.1 (8.2) ICS canisters in the previous 12 months (). High-dose ICS was prescribed to 37.4% of patients, followed by medium-dose (31.7%) and low-dose (30.9%) ICS.

Table 4. Other categories of asthma treatment prescribed in the 12 months before the study visit to patients in the SABINA III Latin American cohort.

Most patients (79.9%) were prescribed ICS/LABA fixed-dose combinations as maintenance therapy, with 41.1% prescribed medium-dose ICS; 33.6% and 25.3% of patients were prescribed high-dose and low-dose ICS, respectively (). Some patients classified by investigators as having mild asthma were also prescribed ICS/LABA in primary and specialist care (7.1% and 20.1%, respectively).

Prescription of OCS bursts

During the 12 months before the study visit, an OCS burst was prescribed to 38.5% of patients (22.5% in primary care and 40.5% in specialist care). In primary care, approximately one-quarter of patients with mild and moderate-to-severe asthma were prescribed an OCS burst (25% and 20.5%, respectively). However, in specialist care, a higher proportion of patients with moderate-to-severe asthma were prescribed an OCS burst than those with mild asthma (45.3% vs. 18.3%, respectively, ).

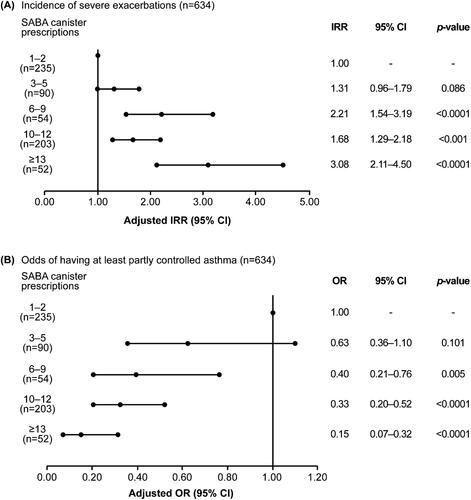

Association between SABA prescriptions and outcomes

In prespecified regression analyses (Supporting Information Figure S2), higher SABA prescriptions (6–9, 10–12, and ≥13 vs. 1–2 canisters) were associated with a significant increase in the incidence rate of severe exacerbations, with adjusted incidence rate ratios (confidence intervals [CIs]) ranging from 1.68 (1.29–2.18) to 3.08 (2.11–4.50; all p < .001; ). The association was not statistically significant for 3–5 versus 1–2 SABA canisters (CI, 0.96–1.79; p = .086). Similarly, with the exception of the category 3–5 SABA canisters (CI, 0.36–1.10; p = .101), the odds of having at least partly controlled asthma decreased significantly with higher SABA canister prescriptions, with adjusted odds ratios (CIs) ranging from 0.40 (0.21–0.76) to 0.15 (0.07–0.32; all p < .01; ).

Figure 4. Association of SABA prescriptions with (A) incidence of severe exacerbations in the 12 months before the study visit and (B) level of asthma control assessed during the study visit in the SABINA III Latin American cohort. Based on the co-variable significance in the models, IRRs are corrected by country, age, sex, BMI, smoking history, GINA step, and education level; ORs are corrected by country, age, sex, BMI, asthma duration, smoking history, comorbidity, GINA step, and education level. BMI: body mass index; CI: confidence interval; GINA: Global Initiative for Asthma; IRR: incidence rate ratio; OR: odds ratio; SABA: short-acting β2-agonist; SABINA: SABA use IN Asthma.

Comparison of results between SABINA Latin America and SABINA III

A comparison of key data on socio-demographic and disease characteristics, asthma treatments, and asthma-related clinical outcomes in the previous 12 months between the Latin American cohort and the overall SABINA III population is summarized in Supporting Information Table S2. The key differences are highlighted in the Discussion section.

Discussion

Findings from the Latin American cohort of the SABINA III study demonstrate that the burden of asthma remains high in this diverse continent. Crucially, 39.8% of patients were prescribed SABA in excess (≥3 canisters/year) of current treatment recommendations (Citation9), highlighting a continuing unmet need for asthma education in Latin America. Moreover, this study documented that higher SABA prescriptions (vs. 1–2 canisters) were associated with significantly increased severe exacerbation incidence rates and decreased the odds of having at least partly controlled asthma (with a few exceptions), underscoring the need for careful monitoring of SABA prescriptions. Indeed, a recent position statement on asthma management in Latin America noted that SABA over-reliance is an important public health concern (Citation3). Therefore, addressing this important issue will require the implementation of current evidence-based recommendations on SABA use and a change in healthcare policy, much in the same way that the Pan American Health Organization addressed antimicrobial resistance in 2018 (Citation31).

Overall, baseline patient and disease characteristics from this Latin American cohort were generally consistent with those observed in the SABINA III study population (Citation25). Notably, approximately 70% of patients were female and classified as overweight/obese (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2). This is not unexpected, given that a positive association has been observed between obesity and asthma prevalence, predominantly in females, in Latin America (Citation32), with obese patients having poor disease control and an increased risk of exacerbations (Citation33–35). Consequently, educational programs may be required to increase awareness of the benefits of a healthier lifestyle, including dietary changes and regular physical activity. Moreover, across both care settings, more than twice as many females as males were classified with moderate-to-severe asthma, which may be due to the fact that following puberty, asthma becomes more prevalent and severe in females (Citation36). Overall, most patients (79.4%) were classified with moderate-to-severe asthma, a finding in line with the fact that the majority of patients (87.6%) were treated by specialists. Therefore, this cohort of patients from Latin America likely represents a “better case scenario” in terms of how asthma is managed in this continent as most patients were treated under specialist care. Interestingly, over one-third of patients in primary care (36.9%) were classified with severe asthma, which may be indicative of delayed referral or a failure to refer patients to specialists (Citation21,Citation23). Thus, coordinating multidisciplinary care involving a closer collaboration between primary care physicians and specialists, in addition to optimizing appropriate referral pathways for severe asthma may benefit patients and improve treatment outcomes (Citation22,Citation37).

Of concern, although only a small number of patients were prescribed SABA monotherapy (4.7%), 50% and 34.6% of these patients were prescribed ≥3 and ≥10 SABA canisters, respectively, in the previous 12 months, placing them at high risk of severe exacerbations (Citation9). A similar worrying trend was also observed in the larger proportion of patients prescribed SABA in addition to maintenance therapy, with 63.4% prescribed ≥3 canisters and 40.2% ≥10 canisters in the preceding 12 months. Furthermore, although a greater percentage of patients were prescribed ≥3 SABA canisters in primary care than in specialist care (56.2% vs. 37.3%), over-prescription was common in both care modalities. However, prescription of ≥10 SABA canisters was more common in patients with mild asthma treated in primary care. This suggests an underestimation of patients with milder disease or inappropriate management of patients with ‘mild’ asthma, resulting in suboptimal symptom control (Citation38). Indeed, both primary care physicians (Citation39–41) and patients (Citation42) tend to overestimate the level of asthma control, resulting in under-treatment of asthma and over-reliance on SABA alone for rapid symptom relief during episodes of asthma worsening (Citation43). Overall, these findings are consistent with those of previous studies from Latin America that have reported an over-reliance on SABAs (Citation16,Citation44), with as many as 80% of patients in some countries across this continent using SABAs daily (Citation14). The fact that less than half of all patients (47.1%) had full healthcare reimbursement may have also contributed to SABA over-prescription, as a lack of healthcare insurance has been associated with poorer quality of asthma care, including a reduced likelihood of prescriptions for ICS (Citation45). Furthermore, factors such as free access to SABAs in some Latin American countries (Citation46) and the high cost of ICS/LABA combination inhalers (Citation1) may also have contributed to the high SABA prescribing patterns observed in this study.

Despite 80.3% of patients from this Latin American cohort receiving SABA prescriptions, nearly one-fifth (17.2%) of patients also purchased SABA OTC in the previous 12 months, with 38.8% purchasing ≥3 canisters. Moreover, it is alarming that of those patients with both SABA purchase and SABA prescriptions, 73.5% were already prescribed ≥3 SABA canisters and 53.6%, ≥10 SABA canisters in the preceding 12 months. As OTC purchase of SABAs is associated with a decrease in physician consultations, low rates of prescription-only medications and undertreatment of asthma (Citation47), there is an urgent need to improve access to affordable care and medications and regulate the availability of SABAs without prescription.

In line with the fact that the majority of patients had moderate-to-severe asthma, approximately 80% of patients were prescribed fixed-dose combination ICS/LABA; this was considerably higher than in previous reports from Latin America (Citation13,Citation48), and may reflect access to specialist care. Surprisingly, some patients classified as having mild asthma were prescribed ICS/LABA in both primary and specialist care (7.1% and 20.1%, respectively). In addition, 20.3% and 18% of patients with moderate-to-severe asthma in primary and specialist care, respectively, were prescribed ICS monotherapy. Such findings potentially indicate the undertreatment of these patients and/or the incorrect classification of disease severity. Thus, prescribing patterns for asthma medications in Latin America are not always in accordance with current GINA recommendations (Citation9), thereby warranting integration of existing treatment recommendations into clinical practice.

In line with earlier reports, (Citation10,Citation13,Citation14,Citation16,Citation49), the level of asthma control in this Latin American cohort was poor, with only 38.5% of patients reporting well-controlled asthma. Moreover, nearly 50% experienced at least 1 severe asthma exacerbation in the previous 12 months, a finding in line with results from a retrospective, hospital-based observational study of hospital admissions in 1994, 1999, and 2004 of 3038 patients from Spain and Latin America (Citation48). Possible explanations for these findings include a lack of peak expiratory flow measurements in the emergency room and insufficient objective monitoring of asthma between exacerbations (Citation48), coupled with socioeconomic barriers limiting access to care and affordable medications (Citation2,Citation3). Taken together and in line with findings from the overall SABINA III study population (Citation25) and additional SABINA studies conducted in the United Kingdom (Citation50), Italy (Citation51), Germany (Citation52), and North America and Europe (Citation53,Citation54), these findings demonstrate that prescribing practices in Latin America fall short of internationally recommended guidelines, highlighting the need for educational programs aimed at both patients and HCPs, including pharmacists. Indeed, in Brazil, the implementation of The Wheezy Child Program reduced hospitalization and emergency room visits (Citation55), while an educational program for socially deprived asthma patients resulted in reduction in symptoms, improved pulmonary function and quality of life, and a greater understanding of the difference between reliever and anti-inflammatory medication (Citation56). In addition, Argentina has focused on establishing SABA-free institutions (Citation3) and promoting ICS use, which has led to a decrease in asthma-related mortality (Citation57). However, while such programs have been shown to be feasible across Latin America and have met with some degrees of success, results from this Latin American cohort demonstrate the need for sustained and relevant educational initiatives.

Our study has a few limitations. Prescription data were used as a proxy for medication usage and may not always reflect actual SABA administration or provide information on medication adherence, potentially contributing to over- or underestimation of SABA use. In addition, due to its observational nature, the study may be prone to bias, e.g. therapies may be differently prescribed depending on disease severity (Citation58). Indeed, our data demonstrated that some patients classified as having either mild asthma or moderate-to-severe asthma were prescribed ICS/LABA and ICS monotherapy, respectively. Furthermore, the high levels of SABA prescription observed in this cohort may be, in part, explained by assessment of disease severity being based on the GINA 2017 recommendations (in place at the time this study was conceived and implemented). The study population, which predominantly consisted of patients treated at the specialist care level, may not be representative of the overall national patient population with asthma across Latin America or truly reflect the way asthma is currently being managed across the continent. In addition, this selection bias may have contributed to the greater number of patients with moderate-to-severe asthma being recruited into the study, which precluded a comparison across asthma severities. Finally, this study was not designed to identify factors potentially associated with the high prescription of SABA medication; however, such an analysis will be the subject of future research. Nevertheless, this study provides broadly generalizable real-world data in the target population from six Latin American countries and highlights that asthma continues to impose a heavy burden across the continent, reinforcing the need for asthma management based on current treatment guidelines.

Conclusions

Results from this Latin American cohort of the SABINA III study in almost 1100 patients indicate that approximately 40% of patients were prescribed ≥3 SABA canisters in the previous 12 months, which is considered over-prescription. In addition, of the 17.2% of patients who purchased SABA OTC, 38.8% purchased ≥3 canisters in the 12 months prior. Of patients with both SABA OTC purchase and SABA prescriptions, the majority already had prescriptions for ≥3 and ≥10 SABA canisters in the previous 12 months. Moreover, higher SABA prescriptions (vs. 1 − 2 canisters) were associated with poor health outcomes. These findings reveal the continued burden of poorly controlled asthma in Latin America and the need for HCPs and policymakers to work together to urgently implement evidence-based recommendations and promote educational efforts, particularly related to SABA prescriptions and the availability of SABA OTC, to improve asthma management across this continent.

Author’s contributions

All authors contributed to data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. The study was designed by Maarten J. H. I. Beekman. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and accept responsibility to submit the manuscript for publication.

Supplementary_material_CLEAN.docx

Download MS Word (396.5 KB)Acknowledgement

Writing and editorial support was provided by Cactus Life Sciences (part of Cactus Communications, Mumbai, India) in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3) and fully funded by AstraZeneca.

Declaration of interest

Felicia Montero-Arias has participated in clinical studies sponsored by AstraZeneca and Novartis. She has also participated in conferences and advisory boards sponsored by AstraZeneca and Novartis. Jose Carlos Herrera Garcia has participated in clinical studies funded by AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Boehringer Ingelheim. He has also served as a speaker in international congresses and as principal editor at Intech Open Library. Manuel Pacheco Gallego has served on speakers’ bureaus for AstraZeneca, Roche, Novartis, Novamed, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Scandinavia Pharma, and Janssen. Martti Anton Antila has participated in clinical studies funded by AstraZeneca, Sanofi Genzyme, EMS, Eurofarma, Janssen, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, AbbVie, and Humanigen. She has also participated in conferences and consultancy activities for Aché, AstraZeneca, Chiesi, Eurofarma, IPI-ASAC, and Sanofi. Patricia Schonffeldt has served on speakers’ bureaus for AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Teva Pharmaceuticals, ITF-Labomed, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Sanofi Genzyme. Walter Javier Mattarucco has served as a study investigator for AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, and Novartis. He has also served on speakers’ bureaus for AstraZeneca. Luis Fernando Tejado Gallegos is an employee of AstraZeneca. Maarten J.H.I. Beekman was an employee of AstraZeneca at the time this study was conducted.

Data availability statement

Data underlying the findings described in this manuscript may be obtained in accordance with AstraZeneca’s data sharing policy described at https://astrazenecagrouptrials.pharmacm.com/ST/Submission/Disclosure.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Global Asthma Network (GAN). The Global Asthma Report. Available from: http://www.globalasthmareport.org [accessed 22 March 2021]; 2018.

- Solé D, Aranda CS, Wandalsen GF. Asthma: epidemiology of disease control in Latin America - short review. Asthma Res Pract 2017;3(4):4.

- Nannini LJ, Luhning S, Rojas RA, Antunez JM, Miguel Reyes JL, Cano Salas C, Stelmach R. Position statement: asthma in Latin America. IS short-acting beta-2 agonist helping or compromising asthma management? J Asthma 2021;58(8):991–994. doi:10.1080/02770903.2020.1777563.

- Cooper PJ, Rodrigues LC, Cruz AA, Barreto ML. Asthma in Latin America: a public heath challenge and research opportunity. Allergy 2009;64(1):5–17. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01902.x.

- Mallol J, Solé, D, Asher I, Clayton T, Stein R, Soto-Quiroz M. Prevalence of asthma symptoms in Latin America: the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC). Pediatr Pulmonol 2000;30(6):439–444. doi:10.1002/1099-0496(200012)30:6<439::AID-PPUL1>3.0.CO;2-E.

- da Cunha SS, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Barreto ML, Genser B, Rodrigues LC. Ecological study of socio-economic indicators and prevalence of asthma in schoolchildren in urban Brazil. BMC Public Health 2007;7:205. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-7-205.

- Endara P, Vaca M, Platts‐Mills TAE, Workman L, Chico ME, Barreto ML, Rodrigues LC, Cooper PJ. Effect of urban vs. rural residence on the association between atopy and wheeze in Latin America: findings from a case-control analysis. Clin Exp Allergy 2015;45(2):438–447. doi:10.1111/cea.12399.

- Noal RB, Menezes AMB, Macedo SEC, Dumith SC, Perez-Padilla R, Araújo CLP, Hallal PC. Is obesity a risk factor for wheezing among adolescents? A prospective study in southern Brazil. J Adolesc Health 2012;51(Suppl 6):S38–S45. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.08.016.

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. Available from: http://ginasthma.org/ [accessed 22 May 2022]; 2022.

- Gold LS, Montealegre F, Allen-Ramey FC, Jardim J, Sansores R, Sullivan SD. Asthma control and cost in Latin America. Value Health Reg Issues 2014;5:25–28. doi:10.1016/j.vhri.2014.06.007.

- Neffen H, Gonzalez SN, Fritscher CC, Dovali C, Williams AE. The burden of unscheduled health care for asthma in Latin America. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2010;20(7):596–601.

- Hulett AC, Yibirin MG, Brandt RB, Garcia A, Hurtado D, Puigbo AP. Home/social environment and asthma profiles in a vulnerable community from Caracas: lessons for urban Venezuela? J Asthma 2013;50(1):14–24. doi:10.3109/02770903.2012.747205.

- Neffen H, Fritscher C, Schacht FC, Levy G, Chiarella P, Soriano JB, Mechali D, AIRLA Survey Group. Asthma control in Latin America: the Asthma Insights and Reality in Latin America (AIRLA) survey. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2005;17(3):191–197. doi:10.1590/s1020-49892005000300007.

- Maspero JF, Jardim JR, Aranda A, Tassinari C P, Gonzalez-Diaz SN, Sansores RH, Moreno-Cantu JJ, Fish JE. Insights, attitudes, and perceptions about asthma and its treatment: findings from a multinational survey of patients from Latin America. World Allergy Organ J 2013;6(1):19. doi:10.1186/1939-4551-6-19.

- Plaza V, Blanco M, Garcia G, Korta J, Molina J, Quirce S, en representación del Comité Ejecutivo de GEMA. Highlights of the Spanish Asthma Guidelines (GEMA), version 5.0. Arch Bronconeumol (Engl Ed) 2021;57(1):11–12. doi:10.1016/j.arbr.2020.10.010.

- Alith MB, Gazzotti MR, Nascimento OA, Jardim JR. Impact of asthma control on different age groups in five Latin American countries. World Allergy Organ J 2020;13(4):100113. doi:10.1016/j.waojou.2020.100113.

- Lai CC, Chen CH, Wang Y-H, Wang C-Y, Wang HC. The impact of the overuse of short-acting β2-agonists on the risk of sepsis and septic shock. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2021.11.029.

- Muñoz X, Romero-Mesones C, Cruz MJ. β2-Agonists in Asthma: the strange case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Arch Bronconeumol (Engl Ed) 2020;56(4):204–205. doi:10.1016/j.arbr.2019.07.010.

- Tanaka H, Nakatani E, Fukutomi Y, Sekiya K, Kaneda H, Iikura M, Yoshida M, Takahashi K, Tomii K, Nishikawa M, et al. Identification of patterns of factors preceding severe or life-threatening asthma exacerbations in a nationwide study. Allergy 2018;73(5):1110–1118. doi:10.1111/all.13374.

- Gonzalez-Barcala F-J, Calvo-Alvarez U, Garcia-Sanz M-T, Bourdin A, Pose-Reino A, Carreira J-M, Moure-Gonzalez J-D, Garcia-Couceiro N, Valdes-Cuadrado L, Muñoz X, et al. Characteristics and prognosis of near-fatal asthma exacerbations. Am J Med Sci 2015;350(2):98–102. doi:10.1097/MAJ.0000000000000518.

- Blakey JD, Gayle A, Slater MG, Jones GH, Baldwin M. Observational cohort study to investigate the unmet need and time waiting for referral for specialist opinion in adult asthma in England (UNTWIST asthma). BMJ Open 2019;9(11):e031740. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031740.

- Price D, Bjermer L, Bergin DA, Martinez R. Asthma referrals: a key component of asthma management that needs to be addressed. J Asthma Allergy 2017;10:209–223. doi:10.2147/JAA.S134300.

- Most JF, Ambrose CS, Chung Y, Kreindler JL, Near A, Brunton S, Cao Y, Huang H, Zhao X. Real-world assessment of asthma specialist visits among U.S. patients with severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021;9(10):3662–3671 e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2021.05.003.

- Gonzalez Barcala FJ, de la Fuente-Cid R, Alvarez-Gil R, Tafalla M, Nuevo J, Caamano-Isorna F. Factors associated with asthma control in primary care patients: the CHAS study. Arch Bronconeumol 2010;46(7):358–363. doi:10.1016/j.arbres.2010.01.007.

- Bateman ED, Price DB, Wang H-C, Khattab A, Schonffeldt P, Catanzariti A, van der Valk RJ, Beekman MJ. Short-acting β2-agonist prescriptions are associated with poor clinical outcomes of asthma: the multi-country, cross-sectional SABINA III study. Eur Respir J 2022;59(5):2101402.

- Motheral B, Brooks J, Clark MA, Crown WH, Davey P, Hutchins D, Martin BC, Stang P. A checklist for retrospective database studies-report of the ISPOR Task Force on Retrospective Databases. Value Health 2003;6(2):90–97. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4733.2003.00242.x.

- Public Policy Committee ISoP. Guidelines for good pharmacoepidemiology practice (GPP). Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2016;25(1):2–10.

- Cabrera CS, Nan C, Lindarck N, Beekman MJHI, Arnetorp S, van der Valk RJP. SABINA: global programme to evaluate prescriptions and clinical outcomes related to short-acting beta2-agonist use in asthma. Eur Respir J 2020;55(2):1901858. doi:10.1183/13993003.01858-2019.

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. Available from: http://ginasthma.org/ [accessed 22 March 2021]; 2017.

- Reddel HK, Taylor DR, Bateman ED, Boulet L-P, Boushey HA, Busse WW, Casale TB, Chanez P, Enright PL, Gibson PG, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: asthma control and exacerbations: standardizing endpoints for clinical asthma trials and clinical practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180(1):59–99. doi:10.1164/rccm.200801-060ST.

- Pan American Health Organization. Recommendations for Implementing Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs in Latin America and the Caribbean: Manual for Public Health Decision-Makers. Available from: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/49645 [accessed 22 March 2021].

- Cassol VE, Rizzato TM, Teche SP, Basso DF, Centenaro DF, Maldonado M, Moraes EZC, Hirakata VN, Solé D, Menna-Barreto SS, et al. Obesity and its relationship with asthma prevalence and severity in adolescents from southern Brazil. J Asthma 2006;43(1):57–60. doi:10.1080/02770900500448597.

- Novosad S, Khan S, Wolfe B, Khan A. Role of obesity in asthma control, the obesity-asthma phenotype. J Allergy (Cairo) 2013;2013:538642. doi:10.1155/2013/538642.

- Vortmann M, Eisner MD. BMI and health status among adults with asthma. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16(1):146–152. doi:10.1038/oby.2007.7.

- Ahmadizar F, Vijverberg SJH, Arets HGM, de Boer A, Lang JE, Kattan M, Palmer CNA, Mukhopadhyay S, Turner S, Maitland-van der Zee AH, et al. Childhood obesity in relation to poor asthma control and exacerbation: a meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2016;48(4):1063–1073. doi:10.1183/13993003.00766-2016.

- Zein JG, Erzurum SC. Asthma is different in women. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2015;15(6):28. doi:10.1007/s11882-015-0528-y.

- Yawn BP, Wechsler ME. Severe asthma and the primary care provider: identifying patients and coordinating multidisciplinary care. Am J Med 2017;130(12):1479. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.10.001.

- Ding B, Small M. Disease burden of mild asthma: findings from a cross-sectional real-world survey. Adv Ther 2017;34(5):1109–1127. doi:10.1007/s12325-017-0520-0.

- Baddar S, Jayakrishnan B, Al-Rawas O, George J, Al-Zeedy K. Is clinical judgment of asthma control adequate?: a prospective survey in a tertiary hospital pulmonary clinic. SQUMJ 2013;13(1):63–68. doi:10.12816/0003197.

- Boulet LP, Phillips R, O’Byrne P, Becker A. Evaluation of asthma control by physicians and patients: comparison with current guidelines. Can Respir J 2002;9(6):417–423. doi:10.1155/2002/731804.

- Chapman KR, Boulet LP, Rea RM, Franssen E. Suboptimal asthma control: prevalence, detection and consequences in general practice. Eur Respir J 2008;31(2):320–325. doi:10.1183/09031936.00039707.

- Price D, Fletcher M, van der Molen T. Asthma control and management in 8,000 European patients: the REcognise Asthma and LInk to Symptoms and Experience (REALISE) survey. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med 2014;24(14009):14009.

- Price D, David-Wang A, Cho S-H, Ho JC-M, Jeong J-W, Liam C-K, Lin J, Muttalif AR, Perng D-W, Tan T-L, et al. Time for a new language for asthma control: results from REALISE Asia. J Asthma Allergy 2015;8:93–103.

- Arias SJ, Neffen H, Bossio JC, Calabrese CA, Videla AJ, Armando GA, Antó JM. Prevalence and features of asthma in young adults in urban areas of Argentina. Arch Bronconeumol (Engl Ed) 2018;54(3):134–139. doi:10.1016/j.arbres.2017.08.021.

- Ferris TG, Blumenthal D, Woodruff PG, Clark S, Camargo CA, MARC Investigators. Insurance and quality of care for adults with acute asthma. J Gen Intern Med 2002;17(12):905–913. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.20230.x.

- Comaru T, Pitrez PM, Friedrich FO, Silveira VD, Pinto LA. Free asthma medications reduces hospital admissions in Brazil (Free asthma drugs reduces hospitalizations in Brazil). Respir Med 2016;121:21–25. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2016.10.008.

- Henry DA, Sutherland D, Francis L. The use of non-prescription salbutamol inhalers by asthmatic patients in the Hunter Valley, New South Wales. Newcastle Retail Pharmacy Research Group. Med J Aust 1989;150(8):445–449.

- Rodrigo GJ, Plaza V, Bellido-Casado J, Neffen H, Bazús MT, Levy G, Armengol J. The study of severe asthma in Latin America and Spain (1994-2004): characteristics of patients hospitalized with acute severe asthma. J Bras Pneumol 2009;35(7):635–644. doi:10.1590/s1806-37132009000700004.

- Neffen H, Moraes F, Viana K, Di Boscio V, Levy G, Vieira C, Abreu G, Soares C. Asthma severity in four countries of Latin America. BMC Pulm Med 2019;19(1):123. doi:10.1186/s12890-019-0871-1.

- Bloom CI, Cabrera C, Arnetorp S, Coulton K, Nan C, van der Valk RJP, Quint JK. Asthma-related health outcomes associated with short-acting β2-agonist inhaler use: an observational UK study as part of the SABINA global program. Adv Ther 2020;37(10):4190–4208. doi:10.1007/s12325-020-01444-5.

- Di Marco F, D’Amato M, Lombardo FP, Micheletto C, Heiman F, Pegoraro V, Boarino S, Manna G, Mastromauro F, Spennato S, et al. The burden of short-acting β2-agonist use in asthma: is there an Italian case? An update from SABINA program. Adv Ther 2021;38(7):3816–3830. doi:10.1007/s12325-021-01772-0.

- Worth H, Criée C-P, Vogelmeier CF, Kardos P, Becker E-M, Kostev K, Mokros I, Schneider A. Prevalence of overuse of short-acting beta-2 agonists (SABA) and associated factors among patients with asthma in Germany. Respir Res 2021;22(1):108. doi:10.1186/s12931-021-01701-3.

- Janson C, Menzies-Gow A, Nan C, Nuevo J, Papi A, Quint JK, Quirce S, Vogelmeier CF. SABINA: an overview of short-acting β2-agonist use in asthma in European countries. Adv Ther 2020;37(3):1124–1135. doi:10.1007/s12325-020-01233-0.

- Quint JK, Arnetorp S, Kocks JWH, Kupczyk M, Nuevo J, Plaza V, Cabrera C, Raherison-Semjen C, Walker B, Penz E, et al. Short-acting β2-agonist exposure and severe asthma exacerbations: SABINA findings from Europe and North America. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2022;S2213-2198(22)00285-9. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2022.02.047.

- Lasmar L, Fontes MJ, Mohallen MT, Fonseca AC, Camargos P. Wheezy child program: the experience of the belo horizonte pediatric asthma management program. World Allergy Organ J 2009;2(12):289–295. doi:10.1097/WOX.0b013e3181c6c8cb.

- de Oliveira MA, Faresin SM, Bruno VF, de Bittencourt AR, Fernandes AL. Evaluation of an educational programme for socially deprived asthma patients. Eur Respir J 1999;14(4):908–914. doi:10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14d30.x.

- Neffen H, Baena-Cagnani C, Passalacqua G, Canonica GW, Rocco D. Asthma mortality, inhaled steroids, and changing asthma therapy in Argentina (1990-1999). Respir Med 2006;100(8):1431–1435. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2005.11.004.

- Roche N, Reddel H, Martin R, Brusselle G, Papi A, Thomas M, Postma D, Thomas V, Rand C, Chisholm A, et al. Quality standards for real-world research. Focus on observational database studies of comparative effectiveness. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014;11(Suppl 2):S99–S104. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201309-300RM.