ABSTRACT

Feedback is dependent on how it is interpreted and used. The present study aimed to explore Swedish primary-school teachers’ and students’ shared concerns regarding classroom feedback interaction. 13 teachers and 23 students (7–9 years old) were interviewed. A grounded theory design was employed for coding and analysis. According to the findings, teachers’ and students’ mutual main concern was to construct clarity regarding what the other communicated. Both strived to construct clarity concerning conditions that they had to adapt to, from aspects as trustworthiness and understanding. The study contributes with an illustration of the relational aspect of classroom feedback in primary school.

Introduction

Feedback is considered to be an essential part of classroom assessment, especially stressed from a formative stance (Black and Wiliam Citation2009; Hattie and Timperley Citation2007; Shute Citation2008). But feedback interaction is also relational, and the effect of teacher feedback is dependent on how it is interpreted and used (Dann Citation2019; Eriksson, Boistrup, and Thornberg Citation2018, Citation2020; Hargreaves Citation2011). According to Dann (Citation2019), there is a need to understand the relational aspect of feedback and not only see feedback as connected to assessment, curriculum and measurable learning outcomes. She emphasises teacher-student dialogue as important for students to see themselves as learners. In order to develop a feedback which serves students’ active participation and learning in school, there is a need for knowledge about teachers’ and students’ views on their feedback interaction, and their shared concerns during feedback interaction. However, studies on student perspectives on feedback are few (Hargreaves Citation2013), and often on higher education (e.g. Evans and Waring Citation2011; Witt and Kerssen-Griep Citation2011). The younger the students are, the less studies seem to have been made.

Hammersley (Citation1990, 45) describes how a student striving to meet the teacher’s wishes, in the sense of giving a proper answer to a question, wonders why the teacher asks him/her that. The multifaceted question visualises the complexity in trying to understand the other. How teachers provide their students with feedback is related to their feedback purpose, their understanding of their students’ learning and needs, and their definition of situation (Brown, Harris, and Harnett Citation2012; Charon Citation2009; Eriksson, Boistrup, and Thornberg Citation2018; Irving, Harris, and Peterson Citation2011). The insights of the formative effect assessment can have on students’ learning has led to a strive for a more deliberating feedback dialogue where students take a more active part (Carless et al. Citation2011; Dann Citation2014; Gamlem Citation2015; Rodgers Citation2018).

Teachers’ sensitivity to students’ signals and ability to adjust feedback to those needs is vital, but not that easy according to research. For instance, Haug and Ødegaard (Citation2015) found in an intervention study that the more confident teachers became regarding interpretation of learning goals, the more sensitive they were to students’ responses. However, increased sensitivity did not seem to lead to any adjustments in the teachers’ feedback. In an ethnographic study presented by Black (Citation2004) the teacher adapted feedback and questions based upon assumptions and previous experiences regarding students’ individual abilities. This gave different students different opportunities to show their learning. Teachers’ responses to students’ signals seem dependent on the assessment discourse used, Boistrup (Citation2015) concludes in an ethnographic study on feedback interaction in mathematics classrooms (students aged 7–16 years old), For instance, in a ‘do it quick and do it right’ discourse, feedback was directive towards methods rather than communication, in opposite to in ‘reasoning takes time’, which was a deliberative discourse.

Not only teachers read the other and adjust once response in feedback interaction. In Rodgers (Citation2018) intervention study in K-5 classrooms, students were asked to give their teachers descriptive feedback about their own learning by putting to words their feelings on their experiences from different aspects. As the students were unfamiliar with describing how they experienced things, they initially rather described what they had learned. They gave the answers that they assumed that the teacher wanted to hear (cf. with the multifaceted question described by Hammersley Citation1990, 45). This can be interpreted as an expression of the unequal power distribution in the classroom that Black (Citation2004) emphasises. According to her, classroom learning much evolved around the student’s ability to read the lesson and learn how to act as a high-ability student to be perceived and addressed as one by the teacher. Murtagh (Citation2014) talks of a paradox concerning students’ view of feedback, where they, on one hand, see themselves as able to cultivate knowledge, and on the other hand, express liking rewards in form of the teacher expressing that a performance is ‘excellent’. She describes it as a paradox between an incremental and an entity approach to learning. In Rodgers (Citation2018) study, by practicing giving descriptive feedback the students became more aware of their own learning process. The teachers also found that they gained valuable information to adjust their teaching and feedback to the students’ needs.

How students understand, receive and are able to use feedback is affected by both the feedback and the students themselves (Lipnevich, Berg, and Smith Citation2016). Timeliness is emphasised as one thing that affects students’ understanding and use of feedback, where both direct and delayed feedback have their advantages (Shute Citation2008; Hattie and Timperley Citation2007). How accurate feedback is and is perceived by students is also of importance, with honesty as an aspect (Lipnevich, Berg, and Smith Citation2016). Feedback can also have a variation of foci and level of detail (Hattie and Timperley Citation2007; Shute Citation2008). Shute recommends feedback that provides for the student necessary information with task focus. Aspects of feedbacks comprehensibility and how well it aligns with students’ expectations also affect how students receive and make use of feedback (Lipnevich, Berg, and Smith Citation2016). Feedback is in all of these aspects more or less dependent on how the student understands it, which according to Lipnevich, Berg, and Smith (Citation2016) has to do with the student’s ability within the topic, prior experiences of feedback, and how receptive the student is to feedback. Hence, as students’ role in the effect of feedback is significant, ignoring students’ perspective would be a mistake.

Gaining a better understanding of teachers’ and students’ shared concerns regarding feedback interaction would contribute to a better understanding of classroom feedback. In the present paper, I explore and conceptualise what shared concerns teachers and students in Swedish primary school have in classroom feedback interaction. In this paper feedback is defined as information on performance or understanding, concerning both academic performances and behaviour. The definition includes both feed up (defining goals) and feed forward (focusing on how to reach those goals), as well as feedback on already made achievements (Hattie and Timperley Citation2007).

Sweden has a nine-year compulsory school in which all students get formal grades from the sixth school year. It is voluntarily for schools to give grades from the fourth school year, but not many do. Before grades, students receive written assessments once every school year. In curricula and syllabuses, learning goals for the end of the first, third, sixth and nineth schoolyears are specified (Skolverket Citation2019). The written assessment is the summative part of an individual development plan, which is mainly formative, focusing on the student’s strengths and further learning. The latter is written during parent/student/teacher meetings, where the student’s present knowledge, learning progress and further goals are discussed. Feedback in primary school has foremost the aim to help students’ further learning towards the nearest syllabus goals, and further if those are achieved. The present study focuses on teachers’ general feedback to students in everyday classroom interaction and addresses both feedback on behaviours as well as academic performances. While classroom feedback is mainly communicated verbally, things such as intonation and gestures can however affect how the feedback is understood by the student.

Theoretical framework

Symbolic interactionism (Blumer Citation1969) was used as an analytical tool, as it provided me with terms helpful for understanding and raising the data analysis to a theoretical level. According to symbolic interactionism, people define the situation they are in, based on thinking and social interaction (Charon Citation2009). Symbolic interaction, thinking, and definition of situation are according to symbolic interactionism the reasons to our actions, and people are active in relation to their surroundings, in what they do and are involved in (Charon Citation2009; Thomas and Thomas Citation1928). Studying feedback interaction in the classroom means studying how the participants attempt to understand and meet the demands, or requests, from the other part, labelled as the ‘significant other’ in symbolic interactionism (Charon Citation2009). According to this framework, classroom feedback can be considered as what Blumer (Citation1969) termed ‘joint action’. The concept refers to a collective form of action in which participants try to fit their own line of actions into the actions of others. In fitting their acts together, the participants need to identify the joint action in which they are about to engage (i.e. classroom feedback), and interpret and define each other’s acts in forming the joint action.

In order to achieve an as accurate picture as possible of the mutual concerns in feedback interaction, the students’ perspectives are just as important as the teachers’ (Mayall Citation2002; Woodhead and Faulkner Citation2008). The new sociology of childhood (Mayall Citation2002; Alderson Citation2005) served to help counterbalance an adult perspective.

Method

Context and participants

The present paper is based on interviews with 13 primary school teachers (10 females and 3 males) and focus group interviews with 23 students (11 girls and 12 boys) in grade 2 and 3 (aged 7–9) in Sweden. All the students attended a small primary school with a socioeconomically mixed and ethnically homogeneous Swedish makeup in the outskirts of a middle-sized city in the middle part of Sweden. The students had participated in a previous field study on feedback in four primary school classrooms (Eriksson, Boistrup, and Thornberg Citation2017). Participating primary school teachers were the four teachers from the previously mentioned field study, of which two were teachers of the students in the present study, and nine additional teachers. Adding teachers was made to ensure data saturation (cf. Charmaz Citation2014). The teachers were recruited from 11 different schools in 8 municipalities of various size, socio-economic and socio-geographical contexts, spread out in the middle parts of Sweden. They had teachers between 4 and 40 years, with 17 years as average.

The data were collected during previous interview studies on primary-school students’ (Eriksson, Boistrup, and Thornberg Citation2020) and teachers’ perspectives on feedback (Eriksson, Boistrup, and Thornberg Citation2018). During the analyses of data mutual concerns in the two groups were recognised, which raised new questions and led to the present study, based on a reanalysis of the interview data. Adding teachers in the prior study on teachers’ feedback rationales (Eriksson, Boistrup, and Thornberg Citation2018) had not changed, but merely confirmed recurrent patterns. That made me see a potential in using that data set together with the student interviews in order to explore and conceptualise what shared concerns teachers and students in primary school have concerning classroom feedback interaction.

Data collection

The teacher interviews were between 31 and 89 min long, with an average of 54 min, and addressed topics such as how the teachers perceived feedback, their rationales for giving feedback, what they found affected their feedback, how they prioritised when giving feedback, and the teachers’ expectations on their students. To investigate student perceptions of teacher feedback, seven focus groups of 3–4 students in each group were made. In accordance to the new sociology of childhood (Mandell Citation1991), I spent time with the students during lunches and breaks, and aimed at showing sincere interest in their perspectives, which helped me gain the students’ trust and access to their perspective. The focus groups took between 23 and 45 min, with an average at 30 min. Topics that were addressed were how the students perceived their role as students, their experiences of what they did during lessons and why, but mainly about their teachers’ feedback to them and others, and their own feedback needs.

In line with a grounded theory approach, the questions were initially wide, but soon narrowed down. This was done by the use of a variation of follow-up questions, asking participants to elaborate and exemplify, and by adding open questions in line with the conversation and the topics in the interview guide (Charmaz Citation2014; Glaser Citation1978; Mayall Citation2002). The student interviews were partially situated, based on observed feedback situations. As grades are not given in the earlier years of Swedish primary school, and the teachers’ assessment practice in year 1–3 mostly is informal, I made the active choice not to use terms such as ‘feedback’ in the student interviews. It was based on the strive to take a least adult role, and not risk using ‘adult’ terminology. The interviews were all recorded and then transcribed verbatim. The interview quotations presented in the findings were translated from Swedish into English by the author.

Data analysis

Data analysis was made according to constructivist grounded theory, through initial, focused and theoretical coding, constant comparisons, theoretical sampling and memo writing (Charmaz Citation2014). The initial coding was made close to data, partially with in vivo codes. As this was a reanalyse of data the coding rather early went into a phase of focused and theoretical coding. Mind maps were used to visualise the connections between codes, and evolved into a figure that illustrate the teachers’ and students’ shared concern, from their different perspectives. Glaser’s (Citation1978) code families the six C’s, The Strategy Family and Interactive Family helped visualise patterns during theoretical coding, illustrating relations between concerns. When comparing teacher and student interview data, a mutual dependency (from the Interactive Family) was prominent in feedback interaction, for instance in how the aspect of trustworthiness was addressed by teachers and students. From symbolic interactionism the concepts ‘significant other’ and ‘taking the role of the other’ were found useful in the theoretical coding, as their meanings were to a high extent present in the concerns that the participants addressed. ‘Definition of situation’, meaning that how a person perceives a situation makes it real (Thomas and Thomas Citation1928), another term central in symbolic interactionism, was also found useful during analysis. In the analysis it meant staying close and true to students’ reports, making their voices heard through how the categories were named, sometimes by the use of in vivo codes (Charmaz Citation2014; Glaser Citation1978; Mayall Citation2002).

Ethical principles

The study follows the ethical guidelines stated by The Swedish Research Council (Citation2017). Informed consent was obtained by all participants, and by the students’ guardians. Before interviews, the participants were reminded of the option to withdraw from the study at any time. All names used in the paper are fictitious to ensure confidentiality. Interviews were made on the participants’ terms. In order to strive to make student and teacher voices equal, and counterbalance an all adult perspective, the new sociology of childhood (Mayall Citation2002; Alderson Citation2005) guided the part of the data collection and analysis that concerned student perspectives.

Findings

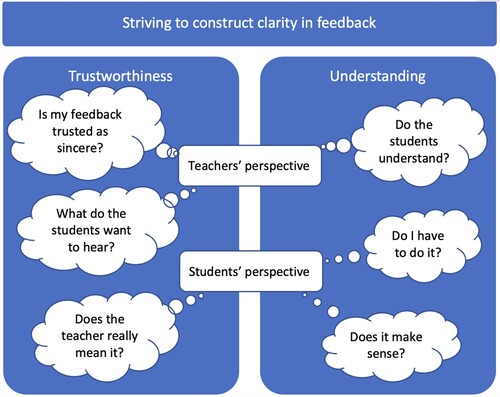

A recurrent pattern in teachers’ and students’ reports on classroom feedback was their concern of clarity regarding what the other communicated. In their descriptions, both teachers and students were occupied with the question of whether or to what degree the feedback was trustworthy and understandable, although, they addressed this from different perspectives. They described the other as someone they were dependent on, hence a significant other. The mutual dependency in their relationship took form in both teachers and students striving to construct clarity regarding the conditions that they had to adapt to in their different roles. In the following presentation of the findings, the constructed categories trustworthiness and understanding will be elaborated and addressed from both students’ and teachers’ perspective.

Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness in classroom feedback was addressed by the teachers as questions if their own feedback was trusted by the students as sincere, and what kind of feedback the students wanted and trusted. The students on the other hand expressed concern about whether they could trust that the teacher really meant what she said. The fact that both addressed the trustworthiness in their feedback communication was interpreted as an expression of the mutual dependency in the teacher–student relation.

Is my feedback trusted as sincere?

The teachers described how they had to interpret signs from their students in order to know whether the students trusted their feedback as sincere. What the teachers reported as signs of how students understood their feedback was partially things students said, but also facial expressions and how students acted. The teacher Teresa reflected:

You see at students if they think, ‘Well that wasn’t sincere. That was just something you said.’ [That they think] it wasn’t something I considered as important. Then there are those who think, ‘yeah, well, how good that you said that!’ (Teresa)

Teresa described how she thought students interpreted her feedback. It was analysed as her trying to take the role of students to gain a better understanding. Teresa addressed the need of making feedback sincere as she reflected on how students interpreted feedback. From her perspective, students might have different perspectives on what is sincere, and this could, at least in part, be linked to what kind of feedback they preferred. In addition, teachers were concerned about the association between their feedback and students’ self-assessment, and how this affected whether feedback was considered by students as sincere:

I get reminded when I hear a student say, ‘But Tilda, you always say that it’s good. You say it looks nice. But look! I don’t write nice.’ But she does. She writes readable. Yes, but to point out, to be more specific. (Tilda)

Tilda’s reflection was interpreted as that she realised that students might not find a ‘good’ trustworthy, and that it might irritate instead of encourage students. In order to be found trustworthy feedback had to correspond to the students’ own view of the quality of a text or performance. She also reflected over the need for praise to be more specific in order to be understood as sincere feedback. How students acted and reacted on their teachers’ feedback was interpreted as signs of how they understood their teachers’ feedback, and also to what degree the students interpreted it as trustworthy.

What do the students want to hear?

The common understanding among the teachers was that students wanted feedback to be trustworthy. To be able to adapt and individualise feedback in accordance with what students found trustworthy, the teachers tried to figure out what kind of feedback their students wanted to hear. Tina explained, ‘They like it when you’re pretty straight forward, because they want to know. ‘What can I improve?’, ‘What am I good at?’ So, everyone wants that actually, that’s what I think.’ The teachers emphasised what was interpreted as a conception of a general desire for sincere feedback among students, but they also reported how students differed in how they would like to receive teacher feedback individually. The teachers described how some students wanted to manage by themselves and did not want immediate feedback from their teacher, while others did. Tina captured the spectra:

I’ve had students that barely need any help. ‘But you don’t have to. I know you think I’m doing good. I don’t need it. I only need confirmation when I’ve finished something, and you’ve checked it.’ [teacher impersonating student voice] –. To those who feel the need of encouragement all the time and need it constantly, almost every fifth minute. (Tina)

As in the excerpt above, the teachers stated that while some students were confident in their own knowledge, other students wanted and anticipated immediate feedback from the teacher. Most teachers reported it as not always easy to interpret students’ signals, and to take students’ perspective. The teachers all agreed on it being easier after a while, when they know their students better.

You see by the response, and that’s what you instantly can check out and see on what level they want it to be. What is it that they find sincere? What feedback is it that they want to receive, and what feedback is it that they don’t want? (Teresa)

According to Teresa, teachers interpret what kind of feedback students prefer by reading their response. She also stressed a link between what students wanted and what students found trustworthy, which was recurrent in the teacher interview data, and hence interpreted as a common understanding among the interviewed teachers.

Does the teacher really mean it?

While the teachers were occupied with interpreting how their feedback was perceived by students and what students found trustworthy, the students concern was about the degree of trustworthiness in teacher’s feedback. The students generally described the teacher as someone who knew much more and better than the students. They also assumed the teacher as someone who had their best in mind. Still, the students sometimes doubted the teachers’ sincerity, wondering if the teachers really meant what they said. For instance, Stina and Sanna explained,

She usually says, ‘Good work!’, she always says that. (Stina, grade 3)

‘Good’, and so, what’s it called–. She always gives thumbs up. I’ve grown tired of that. (Sanna, grade 3)

In both excerpts above, the students emphasised that the teacher had a feedback strategy that she used too frequently in their opinion. The students clarified how some feedback, usually in form of praise, had lost its meaning to them, since it had been used too often by the teacher, and sometimes seemingly unjustified. According to analysis, the students wanted the teacher to do or say something else, or more so, they wanted feedback that they could trust as sincere.

Feedback in form of praise was especially questioned by the students, particularly when it lacked clarifications of what was being praised, and why. A disagreement between teacher and student regarding the students’ ability made the latter question the trustworthiness in the feedback. For instance, Sally (grade 2) described that she after waiting for help for quite a while was told by her teacher that, ‘You know this, this’ll be no problem for you’, and that she then was left by the teacher not knowing what to do. In general, feedback that did not correspondent with the student’s own experiences was seen with a sense of scepticism and seemed to create, and sometimes enhance, the student’s distrust.

Understanding

Except trustworthiness, the question of understanding was also recurrent in both teachers’ and students’ narratives. Both teachers and students seemed to ponder the students’ understanding of teacher feedback. From the teachers’ perspective it was about being understood, while the students considered how they should understand the teacher feedback.

Do the students understand?

The teachers in the study were not only occupied by the idea that their own feedback had to be perceived by the students as trustworthy. They were also concerned about whether they could trust students’ response in how they understand the teacher’s feedback.

The teachers emphasised the need of being sensitive for other signs than just what the student verbally communicated. Tanja, for instance, described that she sometimes had the feeling that ‘This student will soon raise his hand, because he didn’t understand what I was just saying’, and Ted expressed, ‘They say that they understand, but you can see at their body language that they don’t’. According to analysis, tone of voice, body language and facial expressions were emphasised by the teachers as often telling them more about their students’ understanding of feedback, than the students’ verbal responses. Recurrent in the teachers’ narrations was the need to be sensitive to different kinds of signals and to trust one’s instinct. The teachers emphasised that students’ body language, tone or facial expression could contradict what they verbally expressed. My interpretation was that the teachers did not fully rely on doing a correct interpretation about students’ understanding of feedback solely on their verbal response. Toini tried to picture it from a student perspective:

There are so many different strategies, and it’s like, sometimes students get blocked when they don’t understand, and get stressed, I think as well, when a teacher sits beside you or stands leaning over your shoulder trying to explain and asks, ‘Well, do you understand now?’ Eventually you say ‘Yes’ even though you don’t understand, because it’s so stressful that the teacher expects you to understand. (Toini)

According to Toini, students might give an inaccurate response just to get out of a stressful situation. She continued by explaining that students might be thinking about their own appearance, ‘One doesn’t want to look stupid’.

The teachers reported how they interpreted feedback situations in effort to grasp what the students understood, to provide feedback accordingly. For instance, to conclude whether students could follow group instructions and make sense of feedback delivered to the whole class. The teachers described how some students needed individual feedback in addition to whole-class and group feedback, as they did not seem to make use of the feedback given to the group.

The teachers reported it as not always easy to manage to adapt feedback to individual students. It called for the teacher to be receptive for signals from the students. Ted explained that sometimes you realise that ‘This doesn’t reach the students, I need to explain it some other way’. According to the analysis, adapting feedback to primary students also meant explaining things in a variation of ways, perhaps in different words. ‘There can be wide differences concerning in what way, how much and how clear you need to be in order for the student to understand’, Tove explained, stressing the differences in students’ needs for clarity in feedback.

Do I have to do it?

One aspect of the students’ interpretation of teachers’ feedback was to understand to what degree it restricted their own possibility to decide on how to do something. Teacher feedback could be deliberating, but also more steering. Seemingly independent on feedback form, students interpreted whether the teacher’s feedback was an instruction or suggestion.

So, she [the teacher] thought that I ought to manage it by myself, that–. Then I’ll have to try.

Do you try once more, and ask again if it doesn’t work?

Yes, but if she says ‘yes’ eventually, or if she says ‘no’ again, then you don’t just give up. You mustn’t give up. (Sonja, grade 2)

The students’ understanding of teacher feedback as mainly instructional was interpreted as linked to an unclarity on how to by themselves assess if some things they did in school were more important than others, or why they should do something. This unclarity was expressed in forms of questions such as, ‘What if we’re working with something really important, as knowing how to tell time. What if that’s really important?’ (Samuel, grade 2). When the students were asked how they decided if something was important, the aspect of the teacher having their best in mind often came up. If the teacher had asked them to do something, or, as it was in the workbook, it was probably important, and best for them to just do it. The students stressed some things as important based on usefulness. ‘When we’re grownups we need to know specific things for work’ (Signe, year 3). Another way the students justified a task or knowledge as important, was that the teacher had presented it to them as a knowledge requirement. However, the students found there were things they did in school that had not been clarified in degree of importance by the teacher. The excerpt above about telling time clearly demonstrates an insecurity expressed by the students. They were not always certain of the importance of something they were working with. This unclarity restricted the students’ space to decide. By opting something out or giving it lower priority, they risked losing out on something important.

The students interpreted that there sometimes was an amount of space for themselves to decide within the teachers’ instructions, but that space was regulated. Sixten (grade 3) explained, ‘You can write as much as you want, but you don’t have to only write like three lines or so.’ So, even when the teacher had told the students that there was a flexibility regarding amount of text, they understood it as a flexibility within restricting frames. Learning was the purpose of being in school according to the students, and what Sixten articulated was in line with a common understanding among the students, namely that it takes a lot of work to learn and to progress.

Does it make sense?

Most students assumed that their teacher knew better than them and had their best in mind. Thus, even though things not always made sense, if a teacher asked students to do something, they seemed to most often adapt. Sverker (grade 2), for instance, described that he had an individual reward system to motivate him to improve his social skills in interaction with other students. ‘I get stars if I’m nice. If Tessa [the teacher] thinks I’m nice.’ He told this with a sense of pride in his voice, but the teacher’s criteria for being nice was not clear to him, and he was unable to elaborate what ‘being nice’ meant, other that it included not always saying what came to his mind. So even though Sverker perceived the arrangement as good, he did not seem quite sure of what was expected from him.

Another example when students pondered whether teachers’ feedback made sense was when Siri (grade 3) more actively questioned how helpful her teacher’s feedback was. Siri reported how the teacher often handed her coins to help her count when she got stuck on math tasks and asked for help. ‘But then–. I don’t think you learn that much by it. /—/ I don’t understand anything with money, that’s when I’m supposed to do something.’ Siri then described how she had mechanically learnt how to use the manipulatives, and admitted that it helped a bit, but emphasised that it also made counting without money take more time. Thus, it appeared that Siri criticised the strategy suggested by the teacher and used it reluctantly. She seemed to make no sense of the teacher’s steering feedback, but simply followed it because the teacher had told her to.

According to the students, their teachers’ strategies were not always fair, such as helping certain students instantly, while leaving others to wait. However, even when the students experienced unfairness, they often tried to make sense of it. The students mostly did so by constructing a justification that explained why their teachers acted as they did. For instance, the teacher hasting between students and giving short steering feedback was, thus, interpreted as a motive to help as many as possible. Teachers strategy to help some students instantly and leave others to wait, was understood as some of them were in more need of help than others. The students emphasised that the teachers only had their best in mind, and in order to help them all learn had to prioritise. The students perceived that their teacher primarily focused on those students who had the greatest need for help, for instance, those who still were not fluent readers. This way of defining the situation affected much of how students reasoned about their understanding of teacher feedback.

Summary

According to analysis, teachers’ and students’ common main concern regarding classroom feedback was to construct clarity regarding what the other communicated, as illustrated in .

The left-hand side of the figure illustrates the aspect of trustworthiness from both teacher and student perspective, while the right-hand side illustrates the aspect of understanding. For the teachers, it was about interpreting what kind of feedback the students understood and found trustworthy, which set conditions for their feedback. For the students, it was about figuring out how teacher feedback should be interpreted and used. In order to do so the students also processed questions regarding trustworthiness and understanding.

Both teachers and students had the students’ learning in focus. In that process, understanding the other, in other words, taking the role of the significant other, was crucial for both of them. As teacher Tina put it:

You need to have a relation in which you kind of know one another. That you know like, that I know how this works, how–. The student also knows how I work. The same thing the other way around. I know how the student works. Among other things, I know whether they want praise or if they don’t want it. (Tina)

Knowing the other, as it is described by Tina, is interpreted as being sensitive for the signals that the other sends out.

Discussion

According to the current findings, teachers’ and students’ mutual main concern in classroom feedback interaction was to construct clarity regarding what the other communicated. Both teachers and students strived to construct clarity regarding the conditions that they had to adapt to, from the aspects of trustworthiness and understanding. From a student perspective, clarity in teachers’ feedback seems crucial in order for the students to see the use of, and make use of their teachers’ feedback, rather than questioning it. This is a finding in line with Murtagh (Citation2014), who concludes that there is a need for transparency for feedback to be effective.

In feedback interaction, definition of situation, and deciding how to act accordingly to it, was made by interpreting what was said and other cues from the significant other, and by taking the role of the other (Mead Citation1934). As Blumer (Citation1969) puts it, in the fitting of lines of action to each other into the joint action, not only do they need to identify what kind of joint action they are engaged in to interpret what is going on and to guide their own actions, but ‘participants in the joint action that is being formed still find it necessary to interpret and define one another’s ongoing acts’ (71). According to the current findings, the definition of situation could be described as a will for, and uncertainty of whether feedback is interpreted correctly. While the students tried to interpret the message of the feedback and its trustworthiness, the teachers tried to interpret how the feedback was received by the students. Striving to construct a shared meaning of feedback could be described as the teachers’ and students’ main concern (Glaser Citation1978) in their joint action (Blumer Citation1969) of classroom feedback. In the present study, teachers’ and students’ concerns of clarity and trustworthiness were found to be core processes of their co-construction of shared meaning. Clarity and trustworthiness seemed to be perceived by teachers and students as a necessity in successfully forming the joint action of classroom feedback. The interpretative interaction and constant striving to understand the other makes feedback relational, and so the question of quality in feedback. Hammersley’s (Citation1990, 45) multifaceted question ‘why does this person ask me this?’ is indeed present in students’ efforts of understanding their teachers’ feedback. The present study contributes with an illustration of the relational aspect of classroom feedback in primary school classrooms. Furthermore, and in line with previous research (e.g. Black Citation2004; Haug and Ødegaard Citation2015), the inequality in teacher-student feedback interaction is evident in this study as well. Black (Citation2004) highlights how students are dependent on, and tries to adapt to their teachers, and Hargreaves (Citation2011) describes how the teachers strive to give feedback understandable for the students.

The teachers emphasised the need for themselves to be trusted and their feedback to be found trustworthy by the students, findings in line with Hargreaves (Citation2011) and Lipnevich, Berg, and Smith (Citation2016). They also reported how they adapted their feedback depending on who was the receiver (personalities, needs, abilities, knowledge, and skills), and the student’s daily mood as well. The described need for being sensitive to students’ signals can be compared to Frelin (Citation2010), who emphasises teachers’ conscious attention as a significant component for a teacher-student relation to be educational. The students interpreted their teachers’ feedback based on a basic assumption that the teacher has everyone’s best interest in mind. In the primary students’ interpretations of teachers’ choice of feedback strategies, there seemed to be a widespread trust in the teacher. The students saw their teacher as the one knowing better, even when they did not completely agree, and their adaptations were reluctant. The teachers on the other hand expressed a need to adapt their feedback to meet students’ individual wants and needs.

Throughout the data, striving to understand the other part was evident as an essential part of the verbal interaction between teacher and student, and thus also a relevant factor when it comes to how feedback is given, interpreted and used. Several studies have found that there are ways to give feedback that are better than other, as they enhance students’ possibilities to learn more than other, and hence considered as more formative (Hattie and Timperley Citation2007; Shute Citation2008). However, since students’ goals are not necessarily the same as their teachers’, and as their interpretations of their teachers’ feedback is made based on an individual definition of situation, the outcome is not entirely given (cf. Hargreaves Citation2013). This makes ‘a best way’ to give feedback an ideal vision, since individuals’ interpretations, goals and expectations affect the outcome. When teachers give feedback to individual students, the students’ needs and interpretations regulate the feedback. The same works for a group of individuals. The teachers in the study all expressed that students interpreted their feedback differently, and thus formed the content based on their own perceptions (Thomas and Thomas Citation1928).

Conclusion

The aim of the present study was to explore and conceptualise what shared concerns teachers and students in primary school have concerning classroom feedback interaction. The common main concern was to construct clarity in what the other communicated, regarding trustworthiness and understanding. The present findings stress interdependency in the teacher–student relation, a mutual need to understand one another in their specific roles and actions. That relationship is prominent in teachers’ and students’ mutual concern to interpret the other’s signals and adapt, and thus, to fit their lines of actions into the actions of the other in co-constructing classroom feedback. However, according to Haug and Ødegaard’s (Citation2015) findings, the teachers’ adjustment does not seem to come easy.

Since the present paper is based on a limited set of data, the findings cannot be generalised to a discussion of feedback in general or even feedback in primary school. As the findings are contextual, they also limit transferability. Most participating teachers were not from the same school or region as the participating students. However, this study is not a comparison of one teacher’s feedback seen from her and her students’ perspectives. It is a comparison of how primary school teachers reflect on classroom feedback interaction and how primary school students reflect on classroom feedback interaction and the shared concerns these groups have regarding that communication. The study raises questions regarding similarities and differences in how feedback is perceived in different schoolyears, and also regarding primary students’ interpretation of teacher feedback in different countries, potential further steps to take. Studying specific classroom feedback situations through obser-views (Kragelund Citation2013) would also be a way to gain more insight in the feedback interaction that takes place in primary school classrooms.

The amount of studies on participant perspectives on feedback in primary school classrooms is low. To gain insights in feedback practice in primary school there is a need for both qualitative and quantitative studies, as they contribute with different kinds of knowledge. Findings constructed through grounded theory analysis are, according to Charmaz (Citation2014), interpretative portrayals, and as Glaser (Citation1978) states, provisionally. The limitations aside, the present study contributes with an illustration of the relational aspect of classroom feedback in primary school. The findings emphasise the need for teachers to clarify the purpose of school tasks and goals, making them more transparent and understandable for the students. An incentive specific for earlier years of primary school, where some students still are trying to grasp the meaning of school and what it means to be a student. The experiences and interpretations of feedback become parts of the primary students’ constructing of their own studenthood.

If we ask ourselves what kind of feedback would help teachers and students to meet in a mutual understanding of what is communicated, clarity seems to be the key according to the present findings. Shute (Citation2008) recommends task-focused feedback that is elaborated and gives enough, but not too much information, feedback that corrects, but foremost prevents misconceptions. It is a recommendation very much in line with what both teachers and students in the present study strive at. What is enough but not too much, just right, is however not easy to narrow down, as it is relational and dependent on how the individual student interprets the feedback. As Dann (Citation2019) emphasizes, there is a need of receptiveness and dialogue in order for feedback to help students improve their learning.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alderson, Priscilla. 2005. “Designing Ethical Research with Children.” In Ethical Research with Children, edited by Ann Farrell, 27–36. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Black, Laura. 2004. “Teacher-Pupil Talk in Whole-Class Discussions and Processes of Social Positioning Within the Primary School Classroom.” Language and Education 18 (5): 347–360. doi:10.1080/09500780408666888.

- Black, Paul, and Dylan Wiliam. 2009. “Developing the Theory of Formative Assessment.” Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability 21 (1): 5–31. doi:10.1007/s11092-008-9068-5.

- Blumer, Herbert. 1969. Symbolic Interactionism. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Boistrup, Lisa Björklund. 2015. “Governing Through Implicit and Explicit Assessment Acts: Multimodality in Mathematics Classrooms.” In Negotiating Spaces for Literacy Learning: Multimodality and Governmentality, edited by M. Hamilton, R. Heydon, K. Hibbert, and R. Stooke, 131–148. London: Bloomsbury books.

- Brown, Gavin T. L., Lois R. Harris, and Jennifer Harnett. 2012. “Teacher Beliefs About Feedback Within an Assessment for Learning Environment: Endorsement of Improved Learning Over Student Well-Being.” Teaching and Teacher Education 28 (7): 968–978. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2012.05.003.

- Carless, David, Diane Salter, Min Yang, and Joy Lam. 2011. “Developing Sustainable Feedback Practices.” Studies in Higher Education 36 (4): 395–407. doi:10.1080/03075071003642449.

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. 2nd ed. London: SAGE.

- Charon, Joel M. 2009. Symbolic Interactionism: An Introduction, an Interpretation, an Integration. 10th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Dann, Ruth. 2014. “Assessment as Learning: Blurring the Boundaries of Assessment and Learning for Theory, Policy and Practice.” Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice 21 (2): 149–166. doi:10.1080/0969594X.2014.898128.

- Dann, Ruth. 2019. “Feedback as a Relational Concept in the Classroom.” Curriculum Journal 30 (4): 352–374. doi:10.1080/09585176.2019.1636839.

- Eriksson, Elisabeth, Lisa Björklund Boistrup, and Robert Thornberg. 2017. “A Categorisation of Teacher Feedback in the Classroom: A Field Study on Feedback Based on Routine Classroom Assessment in Primary School.” Research Papers in Education 32 (3): 316–332. doi:10.1080/02671522.2016.1225787.

- Eriksson, Elisabeth, Lisa Björklund Boistrup, and Robert Thornberg. 2018. “A Qualitative Study of Primary Teachers’ Classroom Feedback Rationales.” Educational Research 60 (2): 189–205. doi:10.1080/00131881.2018.1451759.

- Eriksson, Elisabeth, Lisa Björklund Boistrup, and Robert Thornberg. 2020. “‘You Must Learn Something During a Lesson’: How Primary Students Construct Meaning from Teacher Feedback.” Educational Studies, doi:10.1080/03055698.2020.1753177.

- Evans, Carol, and Michael Waring. 2011. “Exploring Students’ Perceptions of Feedback in Relation to Cognitive Styles and Culture.” Research Papers in Education 26 (2): 171–190. doi:10.1080/02671522.2011.561976.

- Frelin, Anneli. 2010. Teachers’ Relational Practices and Professionality. Uppsala: Uppsala University.

- Gamlem, Siv M. 2015. “Feedback to Support Learning: Changes in Teachers’ Practice and Beliefs.” Teacher Development 19 (4): 461–482. doi:10.1080/13664530.2015.1060254.

- Glaser, Barney G. 1978. Theoretical Sensitivity: Advances in the Methodology of Grounded Theory. Mill Valley: Sociology Press.

- Hammersley, Martyn. 1990. Classroom Ethnography – Empirical and Methodological Essays. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

- Hargreaves, Eleanore. 2011. “Teachers’ Feedback to Pupils: ‘Like so Many Bottles Thrown out to Sea’?” In Assessment Reform in Education - Policy and Practice, edited by Rita Berry and Bob Adamson, 121–133. Dortrecht: Springer.

- Hargreaves, Eleanore. 2013. “Inquiring Into Children’s Experiences of Teacher Feedback: Reconceptualising Assessment for Learning.” Oxford Review of Education 39 (2): 229–246. doi:10.1080/03054985.2013.787922.

- Hattie, John, and Helen Timperley. 2007. “The Power of Feedback.” Review of Educational Research 77 (1): 81–112. doi:10.3102/003465430298487.

- Haug, Berit S., and Marianne Ødegaard. 2015. “Formative Assessment and Teachers’ Sensitivity to Student Responses.” International Journal of Science Education 37 (4): 629–654. doi:10.1080/09500693.2014.1003262.

- Irving, S. Earl, Lois R. Harris, and Elizabeth R. Peterson. 2011. “‘One Assessment Doesn’t Serve All the Purposes’ or Does It? New Zealand Teachers Describe Assessment and Feedback.” Asia Pacific Education Review 12 (3): 413–426. doi:10.1007/s12564-011-9145-1.

- Kragelund, Linda. 2013. “The Obser-View: A Method of Generating Data and Learning.” Nurse Researcher 20 (5): 6–10. doi:10.7748/nr2013.05.20.5.6.e296.

- Lipnevich, Anastasiya A., David A. G. Berg, and Jeffrey K. Smith. 2016. “Toward a Model of Student Response to Feedback.” In Handbook of Human and Social Conditions in Assessment, edited by Gavin T. L. Brown and Lois R. Harris, 169–185. London: Routledge.

- Mandell, Nancy. 1991. “The Least-Adult Role in Studying Children.” In Studying the Social Worlds of Children: Sociological Readings, edited by I. Waksler, 38–59. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Mayall, Berry. 2002. Towards a Sociology for Childhood – Thinking from Children’s Lives. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Mead, George Herbert. 1934. Mind, Self, and Society: From the Standpoint of a Social Behaviorist. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Murtagh, Lisa. 2014. “The Motivational Paradox of Feedback: Teacher and Student Perceptions.” The Curriculum Journal 25 (4): 526–541. doi:10.1080/09585176.2014.944197.

- Rodgers, Carol. 2018. “Descriptive Feedback: Student Voice in K-5 Classrooms.” The Australian Educational Researcher 45 (1): 87–102. doi:10.1007/s13384-018-0263-1.

- Shute, Valerie J. 2008. “Focus on Formative Feedback.” Review of Educational Research 78 (1): 153–189. doi:10.3102/0034654307313795.

- Skolverket. 2019. Läroplan för Grundskolan, Förskoleklassen och Fritidshemmet (Reviderad 2019). [Curriculum for the Compulsory School, Preeschool Class and School-age Educare (Revised 2019)]. Stockholm: Skolverket.

- The Swedish Research Council. 2017. CODEX: Regler och Riktlinjer för Forskning. Stockholm: The Swedish Resarch Council. http://www.codex.vr.se.

- Thomas, William Isaac, and Dorothy Swaine Thomas. 1928. The Child in America: Behaviour Problems and Programs. New York, NY: Knopf.

- Witt, Paul L., and Jeff Kerssen-Griep. 2011. “Instructional Feedback I: The Interaction of Face Work and Immediacy on Students’ Perceptions of Instructor Credibility.” Communication Education 60 (1): 75–94. doi:10.1080/03634523.2010.507820.

- Woodhead, Martin, and Dorothy Faulkner. 2008. “Subjects Objects or Participants? Dilemmas of Psychological Research with Children.” In Research with Children: Perspectives and Practices, 2nd ed, edited by Pia Christensen and Allison James, 10–37. London: Routledge.