ABSTRACT

This article examines two ethnographers’ fieldwork with young people applying co-production film-making methods and three ways to approach youth-led filmmaking work for researchers and educators. Implicit to our argument is a belief, based on several multimodal projects, that filmmaking consolidates literacy skills and gives young people a more expansive, lived, and at times disruptive sense of literacy learning. In this special issue focusing on research into children’s language, literacy and literature, we give readers a way to take forward a living literacies approach to film work in 3–13 literacy teaching and learning.

Introduction

In this article, we explore filmmaking as a practice and process that can be woven into literacy teaching and learning. Filmmaking mediates people’s stories and ideas in dynamic, multimodal ways and by virtue of its mediated character, film work can present itself as more agentive compared with other forms of composition. In the article, we propose three models for teaching film based on a process over product argument that aligns with a living literacies (Pahl and Rowsell Citation2020) method of literacy teaching. Living literacies (Pahl and Rowsell Citation2020) approaches all meaning making as entangled with people’s everyday lives and located in social practices. To make our argument, we draw on Barry Barclay’s conceptions of filmmaking (Citation2015) combined with Sara Ahmed’s notions of non-performativity (Citation2006, Citation2012) and sticky emotions (Citation2014b).

We came into the process of writing the article through co-viewing. We devoted an afternoon to watching short film clips from our research studies that have stuck with us emotionally and that continue to sit with us as key fieldwork moments. As the afternoon progressed, we started sharing parts of mainstream films that sit and stick with us and gradually we came to see sitting and sticking as the golden thread for the article. Here, we share these research vignettes as a means of illustrating ways that filmmaking can function as both process and product. There are two terms integral to the article: sticking and sitting.

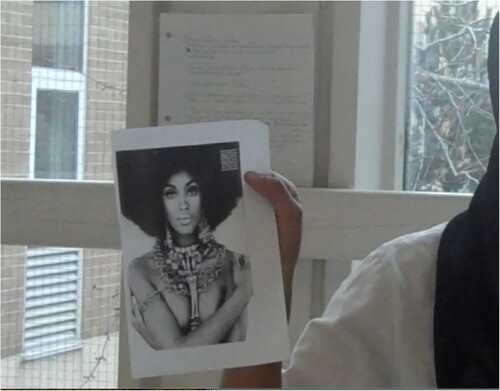

Sticking refers to personally poignant moments during filmmaking that stick with the filmmaker. Sticking happens when filmmaking moments anchor themselves in the production process. In Vignette 3, Jennifer shares a scene from two students’ short film about white hetero-normative images in fashion magazines. For Jennifer, what sticks as an anchored moment in the video is the image held up by one of the filmmakers of an elegant model with an afro that represents true and authentic diversity which is relatively absent from most fashion magazines.

Sitting signals how a particular filmmaking experience might stay with a filmmaker, and how messages or meaning resonate with them over time. Ryan later recollects leading a series of filmmaking workshops with a group of secondary school students who were told their final films would be shown to the rest of the school – only to be disappointed with a non-performative screening to a handful of senior staff members. Ryan reflects on why he feels this experience has stayed with him, and the importance of youth filmmakers having a say on who gets to see what they have made.

So it is that we came together as ethnographers with experience co-producing films with young people in communities, we have had many moments that stick and sit with us. Working with age groups from six to twenty (Jennifer) and from five to nineteen (Ryan), we have developed methodologies for incorporating filmmaking into research to not only document research experiences, but also (and fundamentally) to share stories that sit and stick with us.

Theorising youth filmmaking as praxis and process

To argue for disruptive, co-produced filmmaking spaces in literacy classrooms, we view the praxis of youth filmmaking as part of everyday lived experiences or living literacies (see Pahl and Rowsell Citation2020). Youth filmmaking is a practice of transforming meaning across modes (Gilje Citation2010; see also Bezemer and Kress Citation2008). It affords an exploration of places past, present and future; ‘a means for young people to reconstruct and reimagine both familiar and unfamiliar spaces’ (Blum-Ross Citation2013, 89). Filmmaking that involves young people – as participants and/or makers – is also unpredictable. This is particularly true of filmmaking in the literacy classroom; Pool, Rowsell and Sun reflect on a school-based research-creation project that did not go as planned (in the best possible way), calling for greater recognition of the ‘felt sensibilities of children’ in education (Citation2023, 146). The article approaches filmmaking from our own experiences working with young people on film projects and it is therefore informed and driven by our reflections on the process.

For minoritised youth, filmmaking can serve as a powerful and empowering vehicle for counter-storytelling (Mason and Unity Gym Project Citation2020; see also Bramley Citation2021, 290–296): a key tenet of Critical Race Theory which provides ‘students of colour a voice to tell their narratives involving marginalized experiences’ (Hiraldo Citation2010, 54). Counter-storytelling challenges majoritarian stories which uphold the hegemony of the dominant (and dominating) culture (see Love Citation2004). However, filmmaking can also replicate and reinforce existing power relations – even when it is explicitly attempting to challenge them. Rogers (Citation2016) reflects on a participatory video project with young people which, despite its best intentions, played into the same individualistic and deficit narratives which dominate discourse around young people. Others have raised similar concerns about youth filmmaking. Roy et al. (Citation2021) argue that ‘how stories are being told and by whom’ – as well as ‘how some connection might be made between those stories and potentially resistant third publics’ – should be considered throughout the filmmaking process (970). Similarly, Kennelly (Citation2018) views participatory youth filmmaking as having democratic potential – but adds that such an impact is dependent on creating a film that is ‘palatable and persuasive to middle class audiences and policy actors’ (207). Whilst these are valid critiques of youth filmmaking, this scholarship is primarily concerned with filmmaking as a means of production. In contrast, we argue that filmmaking as praxis and process is – or at the very least, can be – a disruptive and transformative literacy practice in and of itself.

What sits, what sticks in youth film-making

Scholarship around film as a creative practice often places emphasis (and, in our view, over-emphasis) on youth filmmaking as a means of acquiring skills and improving employability (see Parry, Howard, and Penfold Citation2020). Whilst it is encouraging to see film being recognised in UK-based research evaluations such as the Research Excellence Framework (REF), academic write-ups of film-based research projects are often primarily concerned with film as product, rather than process (e.g. Aquilia and Kerrigan Citation2018). Viewing filmmaking as a creative and/or practice-based research tool is, of course, a worthy academic endeavour. However, our work posits that the process of creating film, particularly when working with young filmmakers, is equally deserving of scholarly attention. Youth media production has the potential to ‘support storytelling that disrupts dominant narratives’ (Parry, Howard, and Penfold Citation2020, 410). When adopted critically, youth media practices can create ‘a community-driven, collective narrative to counter and disrupt societal perspectives and perhaps move towards understandings both within and across individuals and communities’ (Johnston-Goodstar, Richards-Schuster, and Sethi Citation2014, 344).

However, as we earlier alluded to, youth filmmaking can reinforce existing power structures and hierarchies as well – particularly when the purpose of the filmmaking process is being dictated to young people by adults. Hauge (Citation2014) documents how a group of young people in Nicaragua were approached by an International Development Association to make a film about a local water project but refused; ‘they did so precisely by not moving in the ways that the organisation wanted them to’ (477). Elsewhere, Hauge and Bryson (Citation2015) argue that participation is often ‘wished’ upon people – particularly when those people are seen as being relatively disempowered. There is, as Street (Citation2003) argues, a tendency to impose ‘western conceptions of literacy on to other cultures or within a country those of one class or cultural group onto others’ (77). If youth filmmaking is to be truly disruptive, the adults in the room need to take a step back and allow young people to create for themselves.

We see youth filmmaking as a hopeful endeavour which can not only ensure that young people are seen but also allow young people to redefine how they are seen. Working with Ahmed’s affective model of ‘stickiness’ – ‘some words stick because they become attached through particular affects’ (Ahmed Citation2014b, 60; emphasis in original) – the disruptive potential of youth filmmaking may allow for negative signs and stereotypes to become unstuck from those they are commonly applied to. Ahmed also warns us that ‘what gets unstuck can always get restuck and can even engender new and more adhesive form of sticking’ (Citation2014b, 100). In this sense, youth filmmaking should never be seen as a one-off activity, but a continued endeavour towards making new meanings and forging new and more hopeful identities.

Youth recording is not youth filmmaking

I (Ryan) have found the late Barry Barclay’s work, as a Māori filmmaker and a social commentator, invaluable in theorising film’s representational potential (see Bramley Citation2021, Citation2023). Whilst Barclay’s Our Own Image: A Story of a Māori Filmmaker (Citation2015) outlines his filmmaking philosophy as an indigenous media maker in New Zealand in the late twentieth Century, Indigenous media models can (and have been) applied effectively to non-Indigenous settings (Nemec Citation2021, 998–999). Indeed, Nemec argues that Indigenous and community media are both ‘considered as “alternative” to the mainstream because of their ability, as critical media, to potentially challenge the dominant discourse of both the organisations within the education system and wider institutional and structural frameworks’ (Citation2021, 999).

One of the ways Barclay (Citation2015) conceptualised filmmaking – which is particularly pertinent to our exploration of youth filmmaking as disruptive practice – is the notion of the filmmaker as a communicator. Filmmaking is more than just holding a camera, and Barclay was keen to distinguish the act of capturing film – the so-called ‘instant recordist’ (Citation2015, 27) – from the art of ‘programme-making’ (Citation2015, 29). Barclay was wary of Māori filmmakers (and particularly young Māori filmmakers) being asked by the majority culture to capture footage of their own communities, as he felt that they were rarely afforded the agency to influence how those recordings were edited:

Recording is not programme-making. Programme-making has to do with creating a metaphor from recordings taken in the field. The majority culture in New Zealand is quite happy to see an abundance of low-cost recording take place in the Māori community, but it is giving precious little help to those who have a desire to turn recordings into metaphors. It makes me angry to see so many of the talented newcomers trapped into accepting the recordist role graciously handed down to them by the system. (Barclay Citation2015, 29; emphasis added)

You’re having yourself on if you think the camera’s neutral. And you need in a way, I believe, to look at who you are making the film for, and exactly what kind of truth you’re telling. (Tuckett Citation2009, 00:18:32-00:18:43; emphasis added)

Advances in affordable digital technology have made filmmaking experiences more accessible for young communicators and audiences: Smartphone filmmaking (see Schleser Citation2021), VR filmmaking (see Balfour et al. Citation2022), and video game playthroughs on YouTube, also known as Let’s Play videos (see Dezuanni Citation2020), to name but a few. However, we recognise that access to digital technology is neither universal nor democratic. In addition to those who are without access to the internet and/or digital skills development opportunities, there is the so-called third level digital divide (see Livingstone, Mascheroni, and Stoilova Citation2023) – described by Van Deursen and Helsper (Citation2015, 30) as ‘gaps in individuals’ capacity to translate their internet access and use into favourable offline outcomes’. We ask teachers in literacy classrooms to take a step back when allowing their students to create their own films, but not to go as far as leaving the classroom altogether.

Disruptive co-produced filmmaking

Over the past few years, there have been many disruptive media movements and practices by youth on social media outlets like TikTok, Twitter/X, YouTube and Instagram to make a stance on issues that matter deeply to them (Dahya and King Citation2020; Hauge and Rowsell Citation2020; Soep Citation2014). To give due consideration of and respect for such work, we argue for the praxis over product philosophy to co-produced filmmaking which is hardly new or cutting-edge, but that needs reminding, foregrounding and theorising. To explore the sharp edge and disruptive snap of young people’s filmmaking, we turn to Sara Ahmed (Citation2014a, Citation2014b, Citation2017) and specifically two of her conceptual threads: non-performativity and sticky emotions. Ahmed advocates for feminism driven by intensely personal and intersectional convictions that disrupt power imbalances and deeply wrought colonial, racist legacies. In her work, Ahmed pierces through viscous discourses and rhetoric to confront discursively and multimodally couched racism, homophobia, transphobia and sexism. In her words, ‘feminist and antiracist consciousness involves not just finding the words, but through the words, how they point, realising how violence is directed: violence is directed toward some bodies more than others’ (Ahmed Citation2017, 34). Children and young people sense, feel and acknowledge how violence is directed, typically experienced through and in the things that they make (Ehret Citation2018).

There are ‘lip service moments’ as a part of gatekeeping or teaching in school that students recognise as precisely that, a statement with no real actions behind it. These moments sometimes happen when administrators or teachers say something to cover policies such as bullying or intolerance with no real intention of doing what they say they will do. Ahmed calls moments like this across varied contexts as non-performatives. An example is the number of times wokeism is referred during far-right speeches to debunk woke agendas. That is, in saying woke or wokeism (i.e. a social and political movement for social justice, inclusion and equality), non-woke believers limit the impact of a woke initiative that challenges racism, sexism and other forms of oppression. That is, wokeism is not (yet) a reality in many places and contexts and in stating that they are an accepted thing and taken-for-granted means that performing social justice can be done when the conditions are not necessarily in place to do so. As Ahmed expresses it, the fact that the discourse does not perform is the whole point: what it says is not what it intends (Ahmed Citation2006, 116). In fact, ‘naming can be a way of not bringing something into effect’ (Ahmed Citation2012, 117). Ahmed’s work on non-performativity (Citation2006, Citation2012) ties in well with Barclay’s discussion of the emergence of indigenous filmmaking and filmmakers in the New Zealand mainstream, in which he uses the analogy of ‘the new noble savage […] shown off in the drawing rooms of the white world’ (Citation2015, 27):

… the majority culture is pleased to fund one or two [Māori filmmakers] from time to time. But when you turn into a difficult native, the drawing room is likely to clear fast. (Barclay Citation2015, 27)

There is a stickiness of affect in the reported film projects that we foreground; rather than a detailed deconstruction or dissection of modal effects, we are much more concerned with modal praxis and affect. As Ahmed (Citation2014b) explains, the doing of emotions ‘is bound up with the sticky relation between signs and bodies: emotions work by working through signs and on bodies to materialise the surfaces and boundaries that are lived as worlds’ (191). Emotions adhere to ideas, activities, policies and they become saturated – sticky – with affect. This stickiness illustrates how ‘emotions “matter” for politics; emotions show us how power shapes the very surface of bodies as well as worlds’ (12). With all of the foregrounded research below, we worked with children, young people and adults as bodies moving with/through/by means of signs. Emotions adhere to visuals, objects, stances, music in a viscous blend of co-production praxis. Structured from more formal, maybe operational school film work (e.g. film as high aesthetic form) across a spectrum to quite open, free, contemporary and untethered film work, we hope that the reader understands the qualitative differences that we present of filmmaking experiences.

Filmmaking as living literacies

Literacy research can come alive through conversations, sharing, co-composing practices and stepping back from the distanced observer in research sites to document what people do. The intent of living literacies is to take an active stance on research processes when everyone in a project changes during a research process. To be engaged, fully present, and together, filmmaking can lead to this kind of co-construction from the bottom-up focusing on praxis over product. The driving force of a living literacies approach to teaching and research is the doing of literacy or literacy as a verb (Pahl and Rowsell Citation2020) and that assembles people, their habits, ruling passions (Barton and Hamilton Citation1998), their co-produced practices and pathways into filmmaking to produce a film.

Literacy has lived properties tied with seeing, creating, hoping, disrupting, knowing and making. Each of these verbs ignites a praxis of filmmaking that encourages filmmakers to co-produce identity-laden moving image texts (e.g. visually mediating a community in a certain way by foregrounding a visual combined with music). As literacy researchers who apply film methods, we find that literacy comes alive when working alongside young and old filmmakers. Stepping back and moving away from well-worn framings of literacy as an object of study toward a view of literacy that implies strands of living literacies (as seeing, creating, hoping, disrupting, knowing and making) animates literacy teaching. Filmmaking is well-suited to a living literacies approach because in making films children and young people can mediate their thoughts, convictions and disruptions beyond the restrictions and boundaries of words. Ryan successfully made a case in 2020 for the development and implementation of a new ‘Practice based PhD’ option in the University of Sheffield’s Faculty of Social Science based upon this principle. Doctoral students based in a Social Sciences department can now incorporate film, music, poetry, prose and other creative artefacts within their thesis, so long as those artefacts either serve a key illustrative purpose or embody the research project’s methodology in a substantive manner (University of Sheffield Citation2022).

A living literacies approach deconstructs visible, frequently colonial privilege and recognises how knowledge production structures from the global north inadequately account for the ways in which knowledge is produced and recognised. Film work allows for this type of breaking down of disciplinary categories and conventions and also allows for a negotiating and blending of filmmakers bound by the narrative. Both of us anchor film work in communities and see film work as emergent. Work by indigenous scholars has moved us into ways of de-centring mainstream white middle-class narratives (Smith, Tuck, and Yang Citation2019). Co-production and collaboration allow people to become the definers, not the defined, of their worlds. Film as the centre of this practice pays attention to how these nuances surface new conceptualisations of literacies, including the felt literacies of neighbourhoods (Kinloch Citation2015) and ways of knowing that are neither written nor oral but something in between across gestural, visual, oral and written modes (Finnegan Citation2015).

Methodological matters

This article is built on our own positionality as researchers who have incorporated visual and film-based approaches to research. We have adopted the use of autoethnographic narrative vignettes (Rådesjö Citation2017) to provide what Pitard refers to as ‘a wide-angle lens with a focus on the social and cultural aspects of the personal, revealing multiple layers of awareness, to understand the experience as lived’ (Citation2016, para. 9). We have both selected particular moments of our careers as researchers-who-use-film that we feel illuminate the sort of changes we would like to see in the way filmmaking is both taught and used in the literacy classroom. We have chosen vignette methodology for this paper as it ‘offers ways to connect research with practice’ in a manner that is often transformative (Skilling and Stylianides Citation2020, 541). Subsequently, each vignette ends with a brief ‘Connecting with Practice’ section, where we present our key takeaways from the process of reflection. We are mindful that it is not always ethically feasible to directly represent the voices of children and young people in research (Vignette 2 provides a particularly good example of this). However, if these experiences are never written down and shared, an opportunity to share our learning (and to learn from readers’ responses to these reflections in-turn) is lost. By using vignettes, we have been able to compare and contrast our varied experiences of film in different educational and cultural contexts – in a manner which comprehensively considers the ethical challenges and sensitivities of doing research which involves children and young people (Skilling and Stylianides Citation2020, 543).

In the vignettes that follow, we revisit film research over the past decade that informs our argument in this article. Even though Jennifer has incorporated film as a part of her research process for many years, she maintains that she is not a filmmaker; not in any classical sense of what a filmmaker is, does, and represents. To her, film is relational and a means to co-produce together and to sit next to young people figuratively and concretely speaking. On the other hand, Ryan does refer to himself as a filmmaker, but reluctantly so. Having never received formal training on how to make a film, he considers himself to be a self-taught filmmaker. Ryan still feels he sits on the margins as filmmaking as an art form, as many self-taught artists do (see Post Citation2017). Both authors fear that they might be perceived by others who specialise in filmmaking as epistemic trespassers; people who lack the necessary competence in a particular area but feel compelled to pass judgement on their peers nonetheless (Ballantyne Citation2019).

The series of vignettes that follow draw on Ryan and Jennifer’s discussions about their respective experiences of working alongside young people filmmaking, illustrating how filmmaking can provide relational, sharing spaces that align with a living literacies approach.

Our reflective vignettes: ‘Filmmaking as living literacies’

Vignette 1: filmmaking as documentation

This first vignette presents a simple way to incorporate film into learning by filming to document children’s meaning making. In this instance, two researchers (Jennifer and her co-researcher) filmed nine- and ten-year-olds as they planned and completed movement tableaux of their science content. From 2016 until 2018, Jennifer conducted a research study with collaborator Glenys McQueen-Fuentes in a Niagara school with year three students (aged 9–10). As part of a SSHRC Insight Development grant called Community Arts Zone, Jennifer and Glenys collaborated with the teacher on a unit of study that was not explicitly about film, but instead followed the science curriculum. Rather than teaching science content through direct teaching or reading and writing content, children learned about scientific processes and principles through movement exercises. Katherine (pseudonym), the year three teacher, was clear from the outset of the research that she was under pressure to complete provincial curricular content and objectives and that we had to work within her programme, so we chose science and specifically the respiratory and digestive systems as the subject for our movement work.

Over two weeks, Jennifer and Glenys observed Katherine’s classes, documented what happened in lessons, student dynamics and personalities, and how children occupied the classroom space. In this way it was less of an ethnography and more of an exploration of practice that led into action research. We thought of it as action research because Glenys taught alongside Katherine and Jennifer and Glenys took turns writing up fieldnotes. By the third week of the observations, we led sessions on movement. For context, Glenys trained with Jacques Lecoq who was a movement expert in Paris. From the Lecoq method, Glenys learned that movement is a universal language and that children (before entering school) are entirely comfortable with it, but once they reach school age and they are socialised into school rites and practices like sitting at desks and lining up, movement is much less prominent, and children become less ‘fluent’ in it.

During our six weeks of fieldwork in Frontier school (pseudonym), Jennifer and Glenys worked with children to think about movement as meaning making and as communication that sits somewhere between language and bodies. Connecting with living literacies, the movement work gave children a way of seeing their science content in a very different, more expansive way and the movement work also disrupted a sense that language is the only way to communicate.

Katherine, students and the researchers created long lists of active verbs based on the circulatory or digestive system. Then, students in small groups (3–5), chose any five of the listed verbs for their group, and using their whole bodies, translated each ‘circulation-or digestion-based’ verb into a ‘frozen picture’ or tableau that were stages of the circulation or digestive process. For example, for digestion, some of the most popular verbs were: chew, swallow, disintegrate, squeeze and expel. Students completed tableaux of digestive processes and they each created a short film that charted out their tableaux before connecting the tableaux through movement (as seen in ).

The movement work hinged on active verbs that children mimicked. Moving to verbs like chew, swallow, circulate, etc invited children to embody scientific processes. Rather than saying or memorising scientific concepts and processes, children acted them out as verb chains to inspire close analysis beyond words and more traditional framings. After filming their movement work and tableaux, we all watched the footage and children were able to see their science content in a different way. What you see in are a series of visuals that capture children standing in quiet contemplation; then, acting out respiratory processes; then, pretending that they are in the middle of the process; and finally, composing their own tableaux of the respiratory cycle.

This brief glimpse into movement and embodied research illustrates ways that film can be woven into teaching as more documentation than producing a short film. Children were accustomed to seeing me film them or Glenys taking photos or filming to capture particular movements. In this way, films were naturalistic and a part of all lessons. There are ethical issues here as there are with all research. During the research, ethics was a part of every discussion and became a living ethics protocol that needed to be revisited, negotiated and agreed-upon with each phase.

As a living literacy, filmmaking as documentation is a form of seeing, disrupting and hoping. Filmmaking can be a lens to understand embodied productions. Artistic and embodied forms allow viewers to see meanings in an alternative form. In the case of this research, it is an artistic form that is situated and collectively produced in a group.

Connecting with Practice: Filmmaking can serve to track key learning moments. As a reflective lens on meaningful moments, naturalistic filming captures what is enacted when pedagogy is filled with possibility. Filmmaking as documentation gives teaching an emergent quality and a chance for children to decide if they want to be filmed and if they do, how and to what end?

Vignette 2: filmmaking as youth-informed

In March 2019, during my (Ryan’s) Doctoral fieldwork placement at the West Yorkshire based social enterprise and media organisation, Kirklees Local TV, I led a series of three filmmaking workshops at a local school (see Bramley Citation2021, 153). These workshops were built in to a broader film project, ‘Windrush: The Years After – A Community Legacy on Film’: led by Kirklees Local TV, who had received a grant from the UK’s National Lottery Heritage Fund to ‘how the intersectionality of race, class and gender influence the every-day reality of being Black in Britain’ (Brown and Nicholson Citation2021, 109). Working alongside Heather Norris Nicholson – an oral historian and academic who has also written about British Women amateur filmmaking as a recreational and visual practice (Motrescu-Mayes and Nicholson Citation2018) – we trained a small group of 12–14 year-old Black students in basic videography and production skills. In parallel to the filmmaking training, we also set each pupil a homework task: to talk with members of their family about their heritage and identity, and come up with an idea for a short film that could be realistically recorded, on school grounds, during the final workshop.

We purposely kept the film brief relatively vague: the theme of the short film had to be related to the Windrush Generation in some shape or form, but beyond that, the students were told that they could essentially film whatever – and however – they wanted. Rather than filming the students myself (as the visiting artist), I encouraged the students to operate the camera and audio recording equipment themselves, inspired by the principles of the Participatory Video approach often used by collaborative ethnographers (Miño Puga Citation2018; Richardson Citation2022). The films the young participants recorded during the third and final workshop were creatively and thematically diverse: one pupil chose a poem that they felt related to them; another wrote a poem specifically for their film. One of the participants brought their parents in to be interviewed about their family history on camera. There was even an impromptu dance from one of the students during the second workshop (where we were testing the cameras); the dancing pupil insisted that we include this as one of the final films, and so we did.

However, not all of the students’ requests were granted. These Windrush films were not meant to be shared with the general public. However, we did originally intend to also show these films to the rest of the school, as a means of sharing the participants’ experiences with both their fellow students and their teachers; this is something that the participants themselves were keen on doing. Unfortunately, rather than being shown in a school-wide assembly, the school hosted the first (and only) screening of these films in a small meeting room, with only the young filmmakers themselves and a few members of senior leadership staff in attendance. Once the final film had ended, the adults in the room left almost immediately; whilst they praised the students for the films they had made – often ‘nodding’, which Ahmed describes as a non-performative act (Citation2019) – there was no space or time for further discussion.

I did not write about the school film screening in my thesis; perhaps I lacked the courage, or the conviction, to do so. I write about it now because even though three and a half years have passed since those workshops, I still feel angry that the films did not get the audience that the young filmmakers wanted. In order for filmmaking to be truly youth-informed, the young filmmakers should get to choose who does (and does not) see what they have created. Carefully considering who gets to see youth-produced film is important; Pahl and Pool give a cautionary tale of a film they made that including young people’s commentaries on a library service in Rotherham, which was deemed important by the local deputy Head for Libraries, but subsequently laughed at by an academic audience at a screening in London (Citation2017, 249–250). Whilst the young people’s Windrush films were not laughed at, the response from the audience was a non-performative one. Ahmed views non-performativity as one of the methods ‘used to try to stop someone from complaining, which is also about trying to contain the data of that complaint’ (Citation2019, para. 22). By nodding during the films and then quickly leaving afterwards, there was no space or time for a discussion of how the themes of the Windrush films could be explored further – the very themes that the young filmmakers felt were lacking from the curriculum (see Bramley Citation2021, 153).

Connecting with practice: Engaging children and young people in filmmaking presents rich developmental opportunities for living literacies, but we should consider giving these young filmmakers – or rather, communicators – a say on who gets to see their films and where. After all, ‘the art of programme making’ is more than just holding a camera (Barclay Citation2015, 29).

Vignette 3: filmmaking as disruptive and provocative

Our third vignette takes place in a secondary school and it features a filmmaking model that sits and sticks through provocation and disruption. From 2011 until 2013, I (Jennifer) conducted an ethnographic research study in a secondary school in the Toronto area with an English and media studies teacher and department head. It was an ethnographic perspective (Bloome and Green Citation2015) in that I conducted fieldwork one day a week over 8 weeks for both the autumn and spring terms. Ultimately, this does not amount to enough time to have an in-depth understanding about the school’s culture and this teacher’s pedagogy. Nonetheless, over two years, I got to know Ellie (pseudonym) well and had a rapport with her two groups of students (15 students/year over the two years). Adopting collaborative ethnography as outlined by Lassiter (Citation2005a), I deliberately and explicitly got to know Ellie and her students and frequently Ellie and I co-taught classes on a variety of topics and text genres. Unlike Lassiter (Citation2005a), I was unable to have a sustained, prolonged collaboration in the classroom, however, I observed and co-taught with Ellie enough to develop a sense of her priorities and teaching philosophy and I got to know a few students well over the course of conversations and watching them produce short films. Over the two years, I worked with Ellie on five units of study: (1) critical voices on fashion; (2) from memes to movies; (3) the journalistic voice; (4) visualising life and (5) product rants. This vignette explores the final unit on a short video two young people produced as a critique about fashion and hair styles. Ellie called this assignment a product rant. I remember three rants in particular having had conversations with each pair of students: one about how expensive trainers are; another one about mobile phones and not banning them; and, the spotlighted one in this section about the lack of diversity of hair styles in fashion magazines – particularly an absence of iconic hairstyles like afros or afro-textured hairdos.

To conduct the research, I took ethnographic fieldnotes and interviewed focal case study students at the end of each school year. Ethics and the ethical process were ongoing and iterative especially as we moved through each unit of study because each one had varying degrees of personal information shared and they visualised lives and subjectivities which demanded conversational consent. As an adult and a researcher, I occupied a particular position with some degree of power and what Lassiter describes as ‘a particular angle of vision’ (Lassiter Citation2005b, 105), so it seemed important throughout my journey with Ellie and her students to ask questions and to problematise experiences so that everyone felt at ease. It is unrealistic and misrepresentative to say that we were all on equal footing, but students were comfortable enough with me being around after a few visits to voice their concerns, questions and discuss alternatives.

The unit started with viewing activities of unboxing videos and product rants on YouTube. Ellie described rant videos as multimodal compositions about products that are critically framed by the writer or filmmaker. Rant videos resemble unboxing videos in that they describe products, but there is more of a stepping back and critiquing them. Ellie has a gift for drawing out students and during this activity, students spoke quite freely about if a rant was successful or not and if they were sufficiently convinced. After viewing, students then scripted their short films, collected assets and mapped out content. From my funding, I was able to buy flip cameras (no longer in production, flip cameras were small, inexpensive hand-held cameras) that pairs of students used to make their rants (there were 6 pairs and one group of three). Each pair was given an assignment brief and after writing up their scripts, they then found a place inside the classroom, in the school, or around the school grounds to film their rant. I want to briefly consider a short video by two year 10 students, Sumaya and Kiara (pseudonyms), who produced a short video about hair and specifically, the types of hair and hair styles that fashion magazines privilege over others. The film began with both females facing the viewer to say:

in the fashion and entertainment industry, it is known that hair should be a specific way. Every hairstyle says something unique about a person, but there are often hidden stereotypes. For instance, when do you ever see a Black woman with an afro? [the other female student jumped in the frame to say] NEVER (See for visual of this moment).

This vignette adheres to a living literacies approach by using film as a way for students to make a stance, be provocative, and disrupt norms, power, and control. A living literacies approach attends to the production of knowledge and this example illustrates how two young women produce knowledge by disrupting what popular culture and fashion say that they should be. They want their audience to see fashion in a different way and to disrupt the idea that there is only one story to what beauty and fashion can be. It is about the literacies of dissent which are rooted in a disruptive approach to the production of knowledge. These types of literacy practices are inherently dialogic, creative and disruptive.

Connecting with Practice: Film can be used with students to disrupt and to be activist in nature and purpose. Sometimes it is not possible to offer assignments that agree, support, and advocate ideas and creating a space in your classroom for disruption and what Ranciere (Citation2010) calls disensus recognises that children and young people need a space to disagree and assert their voice. The idea of dissensus, from Ranciere (Citation2010), can enable an understanding of art as a space of difference, a rupture in the settled norms of everyday life.

Concluding thoughts

We hope that our reflections on our work as sort-of filmmakers – working with young people or, to borrow Barclay’s term, young communicators (Citation2015) – encourages teachers in literacy classrooms to create space for their students to learn through and with filmmaking as both praxis and process. Enabling young communicators to not only capture the everyday through film, but to edit their films too, allows them to create metaphors from their experiences. Equally as important in our view is youth filmmaking’s potential to reimagine (rather than reinforce) stereotypical – and often negative – representations of young people. When given agency in a filmmaking process, young communicators are encouraged to think critically: to ask why certain emotions and sentiments stick to certain people, and the nature of filmmaking as sticky situatedness. Filmmaking allows us to consider how these sticky affects shape the way that people experience the world around them.

We believe that filmmaking in literacy classrooms should go beyond Filmmaking as Documentation (Vignette 1) wherever possible; Filmmaking as Youth-Informed (Vignette 2) allows communicators to consider who they are – not only in relation to their peers and surroundings, but in relation to the camera itself, and the modes of artistic expression it enables. Young communicators should be given the equipment, the training, and perhaps most importantly, the space to make their own filmic metaphors. Filmmaking as Youth-Informed (Vignette 2) goes some way towards achieving this, but only if the wishes of the young communicators are fully respected and, where possible, granted by the adults in the room. Better still, Filmmaking as Disruptive and Provocative (Vignette 3) removes the necessity for young communicators to negotiate what they can and cannot do with their teachers – thus freeing them up to have those difficult, formative, and even transformative discussions with one another.

We end this piece by returning to Barry Barclay’s conceptualisations of filmmaking, which continue to resonate with us. As the constitution of Te Manu Aute – the national organisation of Māori communicators (of which Barclay was a core and founding member) – declares:

Every culture has a right and a responsibility to present its own culture to its own people. That responsibility is so fundamental it cannot be left in the hands of outsiders, nor be usurped by them. (Barclay Citation2015, 7)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all of the aforementioned partners who trusted us to bring the camera into their schools and organisations. Our special thanks go to all of the children and young people who gave us their time, their experience, and most importantly, their trust.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahmed, Sara. 2006. “The Nonperformativity of Antiracism.” Meridians 7 (1): 104–126. https://doi.org/10.2979/MER.2006.7.1.104. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40338719.

- Ahmed, Sara. 2012. On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Ahmed, Sara. 2014a. Willful Subjects. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Ahmed, Sara. 2014b. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Ahmed, Sara. 2017. Living a Feminist Life. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Ahmed, Sara. 2019. “Nodding as a Non-Performative.” Feministkilljoys. April 29, 2019. https://feministkilljoys.com/2019/04/29/nodding-as-a-non-performative/.

- Aquilia, Pieter, and Susan Kerrigan. 2018. “Re-Visioning Screen Production Education through the Lens of Creative Practice: An Australian Film School Example.” Studies in Australasian Cinema 12 (2-3): 135–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/17503175.2018.1539543.

- Balfour, Michael, Jan Cattoni, Πϵρσϵφόνη Σέξτου, Anthony Herbert, Lynne Seear, Guy Lobwein, Margaret Gibson, and Jennifer Penton. 2022. “Future Stories: Co-Designing Virtual Reality (VR) Experiences with Young People with a Serious Illness in Hospital.” Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance 27 (4): 458–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569783.2022.2034496.

- Ballantyne, Nathan. 2019. “Epistemic Trespassing.” Mind; A Quarterly Review of Psychology and Philosophy 128 (510): 367–395. https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/fzx042.

- Barclay, Barry. 2015. Our Own Image. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Barton, David, and Mary Hamilton. 1998. Local Literacies: Reading and Writing in One Community. London: Routledge.

- Bezemer, Jeff, and Gunther Kress. 2008. “Writing in Multimodal Texts.” Written Communication 25 (2): 166–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088307313177.

- Bloome, David, and Judith Green. 2015. “The social and linguistic turns in studying language and literacy.” In The Routledge Handbook of Literacy Studies, edited by Jennifer Rowsell and Kate Pahl, 19–34. London, UK: Routledge.

- Blum-Ross, Alicia. 2013. “‘It Made Our Eyes Get Bigger’: Youth Filmmaking and Place-Making in East London.” Visual Anthropology Review 29 (2): 89–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/var.12007.

- Bramley, Ryan Josiah. 2021. “In Their Own Image: Voluntary Filmmaking at a Non-Profit Community Media Organisation.” PhD Thesis, University of Sheffield. https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/29258/1/White%20Rose%20E-Thesis%20Submission%2024th%20July%202021_Copyrighted%20Images%20Redacted.pdf.

- Bramley, Ryan Josiah. 2023. “‘A Community Legacy on Film’: Using Collaborative Documentary Filmmaking to Go Beyond Representations of the Windrush Generation as ‘Victims’.” Studies in Documentary Film 17 (2): 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/17503280.2022.2090701.

- Brown, Milton, and Heather Norris Nicholson. 2021. “Windrush: The Years After. A Community Legacy.” Oral History 49 (2): 109–121. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48670162.

- Dahya, Negin, and W. E. King. 2020. “Politics of Race, Gender, and Visual Representation in Feminist Media Education.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 41 (5): 673–690. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2020.1769934.

- Dezuanni, Michael. 2020. Peer Pedagogies on Digital Platforms: Learning with Minecraft Let’s Play Videos. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Ehret, Christian. 2018. “Moments of Teaching and Learning in a Children’s Hospital: Affects, Textures, and Temporalities.” Anthropology & Education Quarterly 49 (1): 53–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/aeq.12232.

- Finnegan, Ruth. 2015. Where Is Language? An Anthropologist’s Questions on Language, Literature and Performance. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Gilje, Øystein. 2010. “Multimodal Redesign in Filmmaking Practices: An Inquiry of Young Filmmakers’ Deployment of Semiotic Tools in Their Filmmaking Practice.” Written Communication 27 (4): 494–522. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088310377874.

- Hauge, Chelsey. 2014. “Youth Media and Agency.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 35 (4): 471–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2013.871225.

- Hauge, Chelsey, and Mary K. Bryson. 2015. “Gender and Development in Youth Media.” Feminist Media Studies 15 (2): 287–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2014.919333.

- Hauge, Chelsey, and Jennifer Rowsell. 2020. “Child and Youth Engagement: Civic Literacies and Digital Ecologies.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 41 (5): 667–672. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2020.1769933.

- Hiraldo, Payne. 2010. “The Role of Critical Race Theory in Higher Education.” The Vermont Connection 31 (1): 53–59. https://www.uvm.edu/~vtconn/v31/Hiraldo.pdf.

- Johnston-Goodstar, Katie, Katie Richards-Schuster, and Jenna K. Sethi. 2014. “Exploring Critical Youth Media Practice: Connections and Contributions for Social Work.” Social Work 59 (4): 339–346. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swu041. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24881365.

- Kennelly, Jacqueline. 2018. “Envisioning Democracy: Participatory Filmmaking with Homeless Youth.” Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue Canadienne de Sociologie 55 (2): 190–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/cars.12189.

- Kinloch, Valerie. 2015. Harlem on Our Minds. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Lassiter, Luke Eric. 2005a. The Chicago Guide to Collaborative Ethnography. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press.

- Lassiter, Luke Eric. 2005b. “Collaborative Ethnography and Public Anthropology.” Current Anthropology 46 (1): 83–106. https://doi.org/10.1086/425658.

- Livingstone, Sonia, Giovanna Mascheroni, and Mariya Stoilova. 2023. “The Outcomes of Gaining Digital Skills for Young People’s Lives and Wellbeing: A Systematic Evidence Review.” New Media & Society 25 (5): 1176–1202. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211043189.

- Love, Barbara J. 2004. “BrownPlus 50 Counter-Storytelling: A Critical Race Theory Analysis of the ‘Majoritarian Achievement Gap’ Story.” Equity & Excellence in Education 37 (3): 227–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665680490491597.

- Mason, Will, and Unity Gym Project. 2020. “#Unitydoc: Participatory Filmmaking as Counter-Storytelling.” Youth & Policy. https://www.youthandpolicy.org/articles/unitydoc/.

- Motrescu-Mayes, Annamaria, and Heather Norris Nicholson. 2018. British Women Amateur Filmmakers. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Nemec, Susan. 2021. “Can an Indigenous Media Model Enrol Wider Non-indigenous Audiences in Alternative Perspectives to the ‘Mainstream’.” Ethnicities 21 (6): 997–1025. https://doi.org/10.1177/14687968211029807.

- Pahl, Kate, and Steve Pool. 2017. “‘Can We Fast Forward to the Good Bits?’ Working with Film: Revisiting the Field of Practice.” In Community Filmmaking: Diversity, Practices and Places, edited by Sarita Malik, Caroline Chapain, and Roberta Comunian, 245–262. New York: Routledge.

- Pahl, Kate, and Jennifer Rowsell, eds. 2020. Living Literacies: Rethinking Literacy Research and Practice through the Everyday. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Parry, Rebecca, Frances Howard, and Louisa Penfold. 2020. “Negotiated, Contested and Political: The Disruptive Third Spaces of Youth Media Production.” Learning, Media and Technology 45 (4): 409–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1754238.

- Pitard, Jayne. 2016. “Using Vignettes Within Autoethnography to Explore Layers of Cross-Cultural Awareness as a Teacher.” Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research 17 (1): 11. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-17.1.2393.

- Pool, Steve, Jennifer Rowsell, and Yun Sun. 2023. “Towards Literacies of Immanence: Getting Closer to Sensory Multimodal Perspectives on Research.” Multimodality & Society 3 (2): 130–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/26349795231158741.

- Post, Colin. 2017. “Ensuring the Legacy of Self-Taught and Local Artists: A Collaborative Framework for Preserving Artists’ Archives.” Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America 36 (1): 73–90. https://doi.org/10.1086/691373. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26557057.

- Miño Puga, M. F. 2018. “The Manabí Project: Participatory Video in Rebuilding Efforts after the Earthquake.” Studies in Documentary Film 12 (3): 190–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/17503280.2018.1503860.

- Rådesjö, Megan. 2017. “Learning and Growing from ‘Communities of Practice’: Autoethnographic Narrative Vignettes of an Aspiring Educational Researcher’s Experience.” Reflective Practice 19 (1): 68–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2017.1361917.

- Ranciere, Jacques. 2010. Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics. Edited and Translated by Steven Corcoran. London: Continuum.

- Richardson, Pamela. 2022. “Participatory Video (Remote, Online): Participatory Research Methods for Sustainability - Toolkit #2.” GAIA - Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society 31 (2): 82–84. https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.31.2.4.

- Rogers, Matt. 2016. “Problematising Participatory Video with Youth in Canada: The Intersection of Therapeutic, Deficit and Individualising Discourses.” Area 48 (4): 427–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12141. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44131872.

- Roy, Alastair, Jacqueline Kennelly, Harriet Rowley, and Cath Larkins. 2021. “A Critical Discussion of the Use of Film in Participatory Research Projects with Homeless Young People: An Analysis Based on Case Examples from England and Canada.” Qualitative Research 21 (6): 957–974. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794120965374.

- Schleser, Max. 2021. Smartphone Filmmaking. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Skilling, Karen, and Gabriel J. Stylianides. 2020. “Using Vignettes in Educational Research: A Framework for Vignette Construction.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 43 (5): 541–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2019.1704243.

- Smith, L. Tuhiwai, E. Tuck, and K. W. Yang. 2019. Indigenous and Decolonizing Studies in Education: Mapping the Long View. New York: Routledge.

- Soep, Elisabeth. 2014. Participatory Politics: Next-Generation Tactics to Remake Public Spheres. Cambridge, MA: The Mit Press.

- Street, Brian. 2003. “What’s ‘New’ in New Literacy Studies? Critical Approaches to Literacy in Theory and Practice.” Current Issues in Comparative Education 5 (2): 77–91. https://doi.org/10.52214/cice.v5i2.11369.

- Tuckett, Graeme, dir. 2009. Barry Barclay: The Camera on the Shore. Te Mangai Paho.

- University of Sheffield. 2022. “Practice Based PhDs at the School of Education.” University of Sheffield. April 11, 2022. https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/education/postgraduate/phd/practice-based-phds-school-education.

- Van Deursen, Alexander J. A. M., and Ellen J. Helsper. 2015. “The Third-Level Digital Divide: Who Benefits Most from Being Online?” Communication and Information Technologies Annual 10 (1): 29–52. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2050-206020150000010002.