ABSTRACT

While several studies have investigated the role of parental school choice in exacerbating school segregation, less attention has been paid to the role of institutional contexts and specific educational policies and regulations. However, since the institutional context sets the framework for both school autonomy regarding the admission process and the actual extent of school choice, it has a significant effect on parents’ choices. By comparing two educational contexts that have undergone opposite policy interventions regarding the role of parental choice in school allocation – Mülheim, Germany and Amsterdam, the Netherlands – we confirm the idea that expanding parental choice increases segregation levels. However we also suggest that the relationship between education policies and segregation patterns is very complex and dependent on the interactions of various aspects lying within and outside the education system. Both cases reveal that competition between schools and theirdiscretionary scope in admitting pupils also plays a key part.

虽然有些研究调查了家长择校在加剧学校隔离方面的作用,但对制度环境和具体教育政策法规作用的关注较少。然而,由于制度环境为学校的招生自主权和择校的实际程度设定框架,它对家长的选择有着重要影响。通过比较德国米尔海姆和荷兰阿姆斯特丹这两种教育环境——二者在学校分配中父母选择的作用方面历经相反的政策干预——我们证实了扩大家长选择会增加隔离程度的观点。不过,我们也认为教育政策和隔离模式之间的关系异常复杂,取决于教育系统内外各方面的相互作用。这两个案例都表明,学校之间的竞争以及它们在招生方面的自由裁量权也起到关键作用。

Introduction

While numerous research studies have pointed to parents’ selective school choices as being a key factor in exacerbating school segregation (Wilson and Bridge Citation2019; Perry, Rowe, and Lubienski Citation2022), education policies across the globe have increased parental choice within the last few decades (Forsey, Davies, and Walford Citation2008). School segregation, which commonly refers to the uneven distribution of children with different socio-economic, ethnic or other characteristics across schools, has thus become a widespread phenomenon in many (European) cities (Bernelius and Vilkama Citation2019; Bonal, Zancajo, and Scandurra Citation2019; Oberti and Savina Citation2019).

Patterns and dynamics of school segregation can vary substantially between cities and countries since they are the result of a complex interplay between the specific socio-spatial and institutional context – so called educational landscapes (Boterman et al. Citation2019) – as well as the ways in which parents navigate through these landscapes (Boterman and Ramos Lobato Citation2022). A wealth of studies has revealed that the socio-spatial context, including both the specific residential patterns in cities and the location of specific schools, is central for understanding school segregation (Bernelius and Vilkama Citation2019; Boterman Citation2019; Gamsu Citation2016). An equally vast number of studies has scrutinised parents’ divergent strategies and their underlying motivations to choose and to access certain schools comparing different – often urban – contexts (Kosunen Citation2014; Noreisch Citation2007; Vowden Citation2012). In comparative work, less attention has been paid so far to the institutional context in shaping segregation trends in countries and cities (Boterman and Ramos Lobato Citation2022). With the term institutional context, we refer to the institutional dimensions of the specific educational system including (national and/or local) educational policies and regulations, which guide and structure the extent of public funding, the extent and role of private schools or the school system’s differentiation. Allocation regulations, schools’ autonomy regarding the admission process, and the actual degree of parental choice are among the key institutional aspects affecting levels and patterns of school segregation (Boterman et al. Citation2019). It is the specific institutional context which both sets the framework for regulations and policies in widening or restricting parents’ scope of discretion and shapes the set of options they can realistically choose from (Boterman and Ramos Lobato Citation2022). Therefore, it has a significant effect on parents’ actual school choice practices (Noreisch Citation2007; Raveaud and van Zanten Citation2007; Ramos Lobato Citation2019).

The main aim of this article is to analyse how the institutional context and its specific educational policies and regulations shape parents’ school choice strategies – and, subsequently, influence local school segregation patterns. To do so, we chose a comparative perspective across two local educational contexts that underwent policy interventions regarding school allocation a couple of years ago. These policy interventions led in opposite directions: one introducing more parental choice where geography used to play a key role (Mülheim an der Ruhr,Footnote1 North-Rhine Westphalia, Germany) and the other one centralising parental choice and tying it closer to residential location where parental choice used to be very free (Amsterdam, the Netherlands).

Germany and The Netherlands provide interesting cases to compare the role of education policies in shaping local school segregation patterns. Their education systems share features such as public funding, low financial constraints, a variegated school supply as well as a high level of stratification, early tracking, and academic selection. At the same time, there are noticeable differences in terms of the level of parental choice and the levels and patterns of school segregation. (For more information on both education systems, see below). Both policy interventions affect the allocation regulations for primary schools, which, due to the selective tracking systems of secondary education in Germany and the Netherlands, parents increasingly understand as a crucial first step in their children’s educational career (Breidenstein, Krüger, and Roch Citation2020; Ramos Lobato and Groos Citation2019; Driessen, Sleegers, and Smit Citation2008). Therefore, it is likely that parents in both countries immediately react to policy interventions affecting their choice abilities and opportunities. By analysing and comparing both the motivations behind the policy changes as well as their local effects on parents’ actual school choice practices, our aim was to uncover the institutional mechanisms behind school segregation and to shed light on both the opportunities and limits of school policy interventions to combat it.

The social, spatial, and structural dimensions of school segregation

Patterns and levels of school segregation differ between countries, and even between cities in the same country. Nevertheless, the following mechanisms play a central role in shaping school segregation patterns at the local level in each educational landscape.

First, school segregation is the manifestation of the spatial dispersal of different social and ethnic groups in (urban) space (Boterman Citation2019; Kauppinen, van Ham, and Bernelius Citation2020). Furthermore, as school segregation is about the unbalanced distribution of children over schools and about the isolation or exposure to other social and ethnic groups, the specific composition of cities is also a key ingredient of the mix of school populations. Some cities are ethnically or socially much more diverse than others, which affects the dynamics of school choice and segregation. Depending on the social stratification and ethnic diversity of urban populations, the same ethnic or racial groups are not segregated in the same way across different urban contexts. For instance, the school segregation patterns of Black Americans are different in Midwest cities than in the Southern States (Logan, Oakley, and Stowell Citation2008); or Dutch children with a Turkish background have different segregation patterns in The Hague than in Utrecht (Boterman Citation2018). Also, at the neighbourhood level, where children live determines largely where they go to school. When there is only one state school per district and few alternatives, most pupils attend the school of their residential neighbourhood, such as in Helsinki, Finland (Bernelius and Vilkama Citation2019). Here, school segregation is almost a neat reflection of patterns of residential segregation. Interestingly, even in places with a large degree of parental choice, such as the Netherlands or Ireland, most pupils attends a nearby (primary) school (Ledwith and Reilly Citation2013; Boterman Citation2020). This close relationship between neighbourhood and school implies that school choice and residential choice are part of interrelated socio-spatial strategies (Bernelius and Vilkama Citation2019; Bridge Citation2006; Holme Citation2002). Not only do neighbourhoods inform school choice, but also residential mobility behaviour is often informed by school choice considerations (Kauppinen, van Ham, and Bernelius Citation2020; Boterman Citation2021). Catchment area mobility (that is, moving to specific neighbourhoods to be close to the ‘right’ schools), is a widespread phenomenon and is driven by class-based and racially-based considerations of avoidance and peer-group seeking (Bernelius and Vilkama Citation2019; Boterman Citation2021).

A second key factor in school segregation therefore is the degree to which parents can make choices and the kinds of choices made, within and outside their neighbourhoods. Educational landscapes differ substantially in terms of the options available to parents (Burgess et al. Citation2011), which is largely contingent on whether parents can choose beyond (public) schools outside their residential neighbourhood. If there is little choice within the public system, the ‘circuit’ of private education (Ball Citation2003) is a growing alternative for families who can afford it (Cordini, Parma, and Ranci Citation2019). Private schools are therefore a common feature of highly marketised school systems, such as the one in Chile (Valenzuela, Bellei, and de los Ríos Citation2014), but are also on the rise in social-democratic welfare states such as Denmark (Skovgaard Nielsen and Thor Andersen Citation2019). The expansion of private education and choice has an evident effect on segregation in schools, especially along social class lines (Perry, Rowe, and Lubienski Citation2022). Apart from private education, the expansion of choice-based education provision has also increased the alternatives among publicly funded schools. Charter schools – publicly funded, tuition-free, and independent schools established by teachers, parents, or community groups – and other specific pedagogical profiles have mushroomed in several countries and regions (Verger, Moschetti, and Fontdevila Citation2020). Although the effects of expansion of educational choice vary, generally it has increased the sorting and segregation of pupils (Renzulli and Evans Citation2005; Wilson and Bridge Citation2019), between and within districts (Reardon and Owens Citation2014), and by offering special classes, even within schools (Kosunen et al. Citation2020).

A closely related third factor in explaining school segregation is the differentiation of the supply side, the school landscape. In many national contexts, a variety of faith-based or otherwise denominationalFootnote2 schools exist within or next to the public sector. For instance, in Scotland, Germany, and the Netherlands, historically many state-funded schools provide education to various religious groups, notably Catholics and Protestants (Flint Citation2007). Additionally, state-funded and private schools may offer education based on alternative pedagogical traditions, such as Montessori or Steiner/Waldorf (Morris Citation2015; Karsten et al. Citation2006). The degree of differentiation in the school landscape on the supply side, and thus the range of options available to parents, is closely associated with more choice and subsequently with a greater segregation along ethnic and social class lines (Boterman Citation2018). In urban contexts, the availability of different types of schools, also due to more diverse student populations, is much greater and may further boost the role of parental choice in school segregation. Finally, the institutional context also sets the framework for the degree to which schools can autonomously decide upon their intake. Assignment and enrolment policies can be highly centralised or left to the schools’ discretion. The degree to which schools can set the rules and/or have the liberty to interpret those rules can significantly affect school segregation (Karsten et al. Citation2003; Lubienski et al. Citation2022). The more school autonomy, the more the interaction between parents and the school – represented by principals, secretaries, school boards or other bureaucrats – may be biased for and against specific types of parents (Ramos Lobato Citation2017; van Zanten and Kosunen Citation2013). Several studies have demonstrated that highly educated parents use their social and cultural capital to get access to desired schools (Boterman Citation2013; Hamnett and Butler Citation2013; Raveaud and van Zanten Citation2007). More generally, there is longstanding research that argues that the entire educational system favours the interests of the middle classes (Ball Citation2003; Bourdieu and Passeron Citation1990). School segregation is therefore also an outcome of unequal opportunities throughout the entire school selection, assignment, and enrolment process. The autonomy of schools to make official rules and to apply these and other rules, often unwritten, are therefore another key factor in explaining uneven school compositions.

Germany and the Netherlands: comparing the institutional landscape

Against the backdrop of increasing school segregation patterns in most European cities, a comparative analysis of two educational contexts can help to understand school segregation patterns and to refine the theoretical understanding of European educational dynamics. The comparative perspective of two local educational contexts that underwent opposite policy interventions regarding school allocation a couple of years ago allows the view to be widened from analysing only parents’ individual motivations (as extensively done in previous research studies) and to scrutinise the extent to which the institutional context parents operate in serves as a further source of explanation for their school choice practices. A comparative analysis can thus help to uncover the institutional mechanisms behind school segregation and to serve as the basis for further discussions on both the opportunities and limits of school policy interventions to combat school segregation. The already mentioned combination of both shared features of the educational contexts in Germany and the Netherlands (e.g. public funding, early tracking, and a high level of stratification) as well as noticeable differences regarding the level of parental choice forms an excellent basis for a comparative analysis of the role of education policies in shaping local school segregation patterns.

The policy interventions in both case studies affect the allocation regulations for primary schools. There are two noticeable differences between primary schools in both contexts. The first refers to the differentiation of primary school supply. In the Netherlands, 68% of all primary schools are non-public, which are historically are based on the Catholic (30%) or Protestant (30%) faiths, while in recent years, schools based on Islam or Hinduism have also been founded, mainly in the country’s larger cities (Merry and Driessen Citation2005; Boterman Citation2018). Another substantial number of schools is based on special didactical principles, such as Montessori or Steiner/Waldorf. I. In Germany, differentiation in primary education is not as pronounced as in the Netherlands. Private education is growing but considering they comprise only 3.5% in primary schools, they are still significantly less common than in the Netherlands (Klemm et al. Citation2018, 19). Often, private primary schools are based on a specific religious or pedagogical principle; state denominational primary schools exist only in the federal states of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and Lower Saxony.

The second difference refers to the general role (and level) of parental school choice in both countries. The most defining aspect of the Dutch educational system is both the parents’ right to select (primary) schools and the schools’ scope of discretion to admit pupils. Principals at non-public schools have the right to refuse pupils who do not conform to their ideology, their pedagogical profile or denomination. Furthermore, schools facing greater demand than they can accommodate often adopt priority enrolment procedures and eventually even lotteries to determine school admissions. Local policies for schools may differ slightly between municipalities. In Germany, primary school choice is not very common. To enable efficient planning and to guarantee short distances between home and school, access to primary schools has been organised through catchment areas for decades. However, in contrast to most other federal states, NRW abolished the catchment areas of public primary schools and introduced school choice in 2008.Footnote3 Since no admission criteria were introduced with this policy change, the final decision on the admission of pupils now rests with the school principal. (More information on the current allocation regulations can be found below).

Despite these differences, a common and important principle of both education systems refers to the funding. Almost all primary schools in the Netherlands are publicly funded – with equal funds for public and private schools (OECD Citation2014) – and generally (but not necessarily) accessible to all children (Boterman Citation2018). School fees are in principle voluntary and rarely exceed €200 per annum (PO Raad Citation2019). In Germany, they are financed exclusively from public funding, while private schools are ‘only’ predominantly publicly funded (on average 75%; Klemm et al. Citation2018, 29). All state schools in Germany are tuition-free. Based on the so-called ‘Sonderungsverbot’ (‘segregation ban’), even private schools are officially not allowed to claim excessive tuition fees that would promote a segregation of pupils based on their parents’ economic capital. However, this regulation seems to be ignored (in part) in most of the sixteen federal states (Klemm et al. Citation2018). Moreover, both education systems are known for their quite high levels of stratification, the early tracking, and academic selection, which are all identified as crucial factors hindering equity and educational equality (Van de Werfhorst and Mijs Citation2010; Merry and Boterman Citation2020). Education is compulsory from the age of five in the Netherlands, and six in Germany. Initially based on a welfare- and egalitarian-democratic ideology, in both countries, primary schools are the only comprehensive school type, in which all children of one age group are taught collectively. After joint schooling in primary school, tracking begins at age 11/12 in the Netherlands, and at age ten in Germany (in some federal states at age 12). While in the Netherlands, the transition is based on the teacher’s assessment of students’ academic capacities, transition regulations in Germany vary between the federal states. Predominantly, they depend on the primary school’s recommendation, whereby the final decision can be left up to the parents (e.g. in NRW) or lies with the school based on the fulfilment of specific performance criteria (e.g. in Bavaria). Although the structure of secondary education varies between Germany and the Netherlands, the different secondary tracks prepare for divergent educational and occupational pathways in both education systems. The transition from primary to secondary school has broad implications for children in both countries. Therefore, parents increasingly perceive the choice of the ‘right’ primary school as crucial and therefore risky – even though it is still at an early stage of a child’s educational career (Krüger, Roch, and Breidenstein Citation2020; Ramos Lobato and Groos Citation2019).

Methodology

Our aim with this article is to cast light on the institutional mechanisms behind school segregation by analysing and comparing two recent school policy changes in the Netherlands and Germany and their subsequent local effects. It is based on two independent studies which were originally not designed for comparative analysis, but both were conducted in the context of policy interventions in respect to school choice. We used the two case studies to compare the impact of school admission policies on segregation. This article thus analyses the experiences in both cases from a common framework and compares how policy changes in school choice played out in the two contexts. Similarities and differences between the policy reforms in the two case studies, their underlying intentions, and effects on local school segregation patterns were analysed against their own particular backgrounds as well as collectively discussed and compared.

The Dutch case study is embedded in a larger research project on school choice and school segregation in the Netherlands and draws also on earlier findings (see Boterman and Lobarto Citation2022). For this specific comparative article, we drew on a combination of policy documents and secondary data sources from the school boards and the City of Amsterdam to investigate the policy changes in Amsterdam's admission system. Furthermore, we used individual-level register data from Dutch Statistics (SSD), aggregated at the level of schools, to calculate changing school enrolment patterns and segregation levels in the city, before and after the introduction of the new system.

The German case study is embedded in a PhD project on school choice and school segregation in Mülheim, NRW and also draws on earlier findings (see Boterman and Lobarto Citation2022). To reflect on the policy changes regarding the North Rhine-Westphalian primary school admission regulations for this comparative article, a combination of local and regional policy documents as well as interviews with politicians and municipal and state public administration officers was used. Moreover, we drew on a quantitative database combining the compulsory primary school entrance test, a questionnaire for parents, and local statistics in Mülheim to calculate changing school choice patterns and segregation levels in the city, predominantly after the abolition of primary school catchment areas.

Recent policy reforms and their local effects in Amsterdam and Mülheim

The central relationship in the emergence of school segregation is the interaction between parents’ school choices and the schools’ specific admission policies (practices). There are several dimensions in the way this relationship is institutionalised. However, its key elements are the way in which geography constrains choice, which choice options are available to parents, and how their choices are processed by schools. Next, we discuss two quite opposite policy interventions as regards school admission practices and parents’ choice options in primary education and their consequences for school segregation in Amsterdam, the Netherlands and Mülheim, NRW, Germany.

From ‘free’ choice to ‘controlled’ choice: new admission policies in Amsterdam

Before the introduction of the centralised admission policy, the dynamics of school segregation in Amsterdam were related to specific institutional arrangements at both the national and municipal levels, and the resulting dynamics of choice and admission. First, as in the rest of the Netherlands, parents in Amsterdam could send their children to any primary school they desired, even in other municipalities. However, choice was not exercised to the same degree by all parents. Especially upper middle-class parents used the freedom of school choice to carefully select schools with higher test scores and that provide a socially homogeneous environment (Karsten et al. Citation2003; Boterman Citation2013). Some schools were/are in high demand, so several parents gamed the system and signed up for several schools at the same time to increase the chance of a successful admission. This caused some problems. First, some schools were unable to calculate the number of pupils who would eventually be attending. Second, schools had their own admission criteria and priority rules. Especially in the case of high-scoring schools in affluent neighbourhoods, the board would give priority to families living in the same postal code as the school (Boterman Citation2013). Third, the wide range of school types (faith-based, special pedagogical programme, etc.) presented additional complexity to both the predictability of the outcome of selection and admission for parents and school boards. To summarise, the former system offered space for manoeuvre for both schools and parents, while it was mainly those well-endowed parents with high levels of social and cultural capital who knew how to guarantee access to high-demand schools even outside their own postal code (Boterman Citation2013).

In the 2014/2015 school year, the school boards, which represent 211 of the 222 primary schools in the city, collectively and voluntarily agreed to reform their admission policies through a centralised enrolment system. The main aim was to make the admission process more transparent and predictable for both parents and schools (see also Sissing & Boterman, fc.). It sought to maintain as much parental choice as possible while creating a level playing field for both parents and schools. The idea of strengthening the relationship between neighbourhoods and schools is one of the central pillars of the new admission policy (BBO Citation2018). By creating a place-based priority system, the new legislation reduced some of the autonomy of individual schools as regards the admission process. However, even though it was built up from several pilot studies aimed at desegregation in Amsterdam (Paulle, Mijs, and Vink Citation2016), in the official aims and pillars of the new admission policy, no reference is made to segregation or the deliberate intention to create a more mixed school population.

The new policy is organised in three rounds per year of centralised signing up for schools by parents, who receive a form from the municipality on which they must rank their preferred schools. Based on the exact postal code of the home address of children, the eight closest schools are designated as ‘priority schools’. After submission of preferences, children are allocated to schools according to four algorithms: First, younger siblings of pupils at school; second, children who attended a pre-school connected to the primary school; third, children whose parents work at the school on a permanent contract; and fourth, children for whom the desired school in one of the eight priority schools will be guaranteed a spot. The admission is conducted in three rounds in which first, all priority children will be admitted to the school of their highest ranking, second, all non-prioritised children and third, all children from outside Amsterdam.

From catchment areas to free parental choice: new admission policies and their objectives in mülheim/NRW

Before the policy reform in 2008, access to primary schools in NRW was organised through catchment areas, as it is in other German federal states. One catchment area usually included one primary school and children were legally obliged to attend it. Comprehensive primary schools in Germany have a distinctly local character. For a long time, they have been perceived as the ‘egalitarian basis’ of the education system (Breidenstein, Krüger, and Roch Citation2014, 166), particularly as opposed to the highly segregated secondary school tracks. Nevertheless, there always had been at least some room for (illegal) choice, either by applying for permission under exceptional circumstances or for a school with a special pedagogical or religious profile (Riedel et al. Citation2010). In contrast to the Dutch case study, there was no substantial critique of or controversial discussion about the old enrolment system. However, as primary school profiles started to diversify (Altrichter et al. Citation2011) and particularly higher-educated parents became more strategic in selecting the ‘best’ primary schools for their children (Krüger, Roch, and Breidenstein Citation2020), the ‘one school for all’ ideal started to crumble. In NRW, this development culminated in the abolition of primary school catchment areas.

The policy reform’s main aim was to strengthen parental choice (MSW NRW Citation2005). It was part of a paradigm shift in North Rhine-Westphalian education policy towards an educational market with more competition, more transparency, and more choice. The intention behind was to improve the quality of education fundamentally ‘through an increased focus on performance and competition’ (MSW NRW Citation2005). Therefore, the abolition of catchment areas was only one element in a whole series of amendments within the NRW education act in 2006 (MSW NRW Citation2005; Ramos Lobato and Groos Citation2019). Like the Amsterdam case, the policy reform did not make any clear reference to school segregation or the intention to create a more mixed school population. Rather, the abolition of catchment areas was advertised as a tool to reduce inequity of choice arguing that even in the old system, not all children attended the catchment area schools, with mainly well-educated parents knowing how to enforce this exception. At the same time, potential economic or organisational constraints potentially limiting some parents’ real opportunities to choose a primary school outside their neighbourhood were not considered.

The policy reform introduced new allocation regulations and largely widened parents’ choice options. Theoretically, it enabled parents to register their children at any primary school. However, there still is a legal claim for a place in the nearest school ‘in accordance with the schools’ predefined capacities’ (Landtag NRW Citation2018; Schulgesetz NRW §46 Absatz 3). Thus, spatial proximity still plays a role, particularly for socio-economically less privileged parents, since travel expenses are only reimbursed when attending the nearest primary school (MSW NRW Citation2005). Apart from spatial proximity, criteria regulating the access to primary schools seem to be fuzzy. The final decision on the admission of pupils is up to the principals, who are also allowed to reject pupils if the school’s capacity is depleted (Schulgesetz NRW §46 Absatz 1). Therefore, although not intentionally implemented to expand school autonomy, this loophole not only increased (middle-class) parents’ room for manoeuvre in ensuring their children’s access to certain schools, but it might also have reduced the transparency of allocation and thereby widening the leeway for the schools in admitting (and selecting) pupils.

The impact of the policy reforms in Amsterdam and Mülheim: changing school choice and segregation patterns and different effects for schools

In both contexts, the new admission policies affected local school choice and segregation patterns – but in somewhat contrasting ways. While the introduction of parental choice in Mülheim resulted in increasing levels of school segregation, in the slightly more constrained choice system in Amsterdam, segregation levels continued to go down.

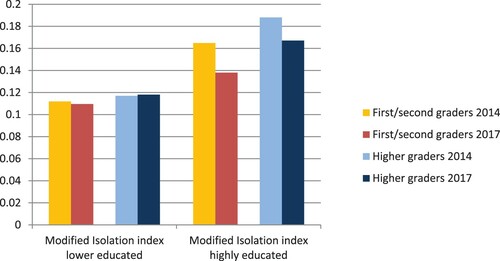

Taking the year before the introduction of the policy in Amsterdam (the 2015/2016 school year) as a starting point and focusing on the segregation levels of the first graders, the analysis demonstrates that the composition of primary schools changed (Cohen, Boterman, and Van Spijker Citation2018). Comparing the first graders (grade 1–2) with the pupils attending that school before the introduction of the new policies illustrates that the trends are differentiated between the grades: the lower grades are getting more mixed compared to the higher grades. This is confirmed in that shows the modified isolation indexFootnote4 for children of lower educated and highly educated parents. It illustrates that while the students in the lower grades attend schools in which they are slightly less exposed to their own group (both low and high), the children in higher grades demonstrate a lower exposure to their own group when they have parents with at least a university degree, but higher levels of isolation for the children of lower educated parents. These findings suggest that the new admission policies could have a modest desegregating effect. However, what needs to be stated is that these declining levels fit into a more consistent trend of declining levels of school segregation in Amsterdam, which would most likely manifest in the lower grades first.

Figure 1. School segregation levels in Amsterdam 2014–2017 (Cohen, Boterman, and Van Spijker Citation2018).

Interestingly, data on the proportion of pupils attending schools in their own neighbourhood () reveal that the new policies do not coincide with a greater role for the neighbourhood in school selection. Whereas in 2008, 55% of the children attended a neighbourhood school, this dropped to 51% in 2017. The same trend can be observed for children of highly educated parents. It thus seems that despite the explicit aim to create a greater bond between a neighbourhood and school, it did not cause a clear break with the existing downward trend.

Table 1. Attendance of schools in one’s own neighbourhood (data from SSB, Dutch Statistics 2018).

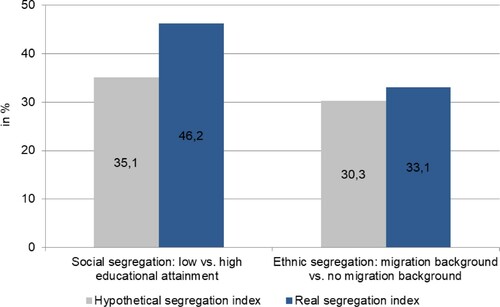

In Mülheim, the policy reform had a converse effect on primary school segregation. A comparison between the real dissimilarity indexFootnote5 (of children whose parents have a low educational attainmentFootnote6 and children with a migration backgroundFootnote7) and the hypothetical ones (reflecting the distribution if every child attended the nearest primary school) reveals that school segregation levels have increased substantially since the policy change – at least school social segregation (). Not only would school social segregation be considerably lower (35% instead of 46%) if school catchment areas still existed, it has also grown over the last few years. At the same time, school ethnic segregation was lower and has slightly decreased over the last years, while the difference between the hypothetical and real composition of schools is also only marginal (30% instead of 33%). One potential explanation is the growing level of poverty in Mülheim (particularly child poverty) in combination with the exacerbating processes of socio-economic polarisation (Ramos Lobato and Groos Citation2019).

Figure 2. School segregation levels in Mülheim 2012–2016 (adapted and updated from Groos Citation2015).

The growing segregation levels in Mülheim are a direct result of increasing school choice. Whereas in the old system, only 10% of the first graders attended a primary school outside their catchment area, this proportion tripled to almost 31% in 2016/2017 (). At the same time, the proportion of parents choosing a denominational school has decreased significantly. While this is partly due to the closure of one denominational school in Mülheim during this time, it also reflects the changing role of denominational schools in the local educational landscape, since they offered the only legal opt-out option before the abolition of catchment areas.

Table 2. Attendance of school inside or outside of former catchment area.

Most of those parents making use of choice are well educated (almost 50%, which is also the biggest group in numbers). The calculation of school choice for different social groups (measured by parents’ educational attainment) reveals that parents with a low educational attainment level select the school within the former catchment area most often, even though differences between groups were rather small (Ramos Lobato and Groos Citation2019). These differences were more pronounced when additionally accounting for the schools’ composition. Although most parents with a high educational attainment still prefer the local school as well, this is only true for schools with a comparatively privileged composition (characterised by low proportions of children dependent on social security benefits, or with a migration background). If the local school has a ‘disadvantaged’ composition, it is only chosen by one third of these parents but still by the majority of parents with a low educational level of attainment (Ramos Lobato and Groos Citation2019).

While the growing levels of school segregation in Mülheim are directly connected to an increase of (socially selective) choice, the slightly reduced segregation levels in Amsterdam do not seem to be necessarily related to less choice. In contrast, the first evaluations show that despite the slightly constrained freedom of choice, almost all children throughout all boroughs were accepted at one of their preferred schools. Most of them were admitted because they met one of the three non-geographical priority criteria (BBO Citation2016 & Citation2018). Thus, the new policy seems to have had only a limited effect on the school choice processes in the city. As almost all children are admitted to the schools desired by their parents, the only modest shift in local patterns of school segregation is not surprising.

Effects on school enrolment

In both case study areas, there is a clear geography behind the ways in which the new policies played out. In Amsterdam, in the period 2015–2018, most schools could accept all prospective pupils. By 2015/2016, 12% of the schools participating in the new admission system could not accommodate all demand but this dropped to include just a couple of schools in the later years. More relevant appears to be the substantial overcapacity, which is particularly concentrated in the boroughs of Noord and Nieuw West and lowest in the historical centre (BBO Citation2018, see ). This corresponds with more general patterns of housing market segregation in Amsterdam showing an increasing polarisation between peripheral boroughs and affluent inner-city boroughs (Boterman Citation2020). Furthermore, in the affluent borough of Amsterdam South, ten schools (out of 37 in that borough) do not participate in the centralised admission procedure, but maintain their own procedures allowing for much greater control of their intake. Therefore, it is not a coincidence that these schools face an over-demand and most likely that their exclusive status within Amsterdam’s educational landscape specifically affects the patterns and levels of segregation in the city.

Table 3. Capacity and admission at schools across Amsterdam’s boroughs.

Similar but partly more subtle spatial patterns of choice can be observed in Mülheim. When comparing overcapacities between schools, spatial patterns of demand and supply between neighbourhoods are not as straightforward as they are in Amsterdam. Differences are more pronounced at the school level () reflecting the existence of small-scale educational hierarchies, even within the more homogenous northern and southern neighbourhoods.

Table 4. Comparison between real and hypothetical composition of three most privileged and less privilegedTable Footnotea schools.

Thus, while some schools have been hit quite strongly by shrinking registration numbers and increasing proportions of children of benefit-recipients, others clearly benefit by free parental school choice (). The schools most affected, but not necessarily always, are those with a less privileged composition (e.g. lower levels of parental educational attainment, higher proportions of unemployment, and of children dependent on social security benefits).

Conclusions

Reflecting the increasing parental support for more ‘consumer’ choice in education (Forsey, Davies, and Walford Citation2008), education policies in many countries have prioritised parental school choice in recent years. Since several studies have illustrated that the local repercussions of this globally widespread idea are very often not as benign as suggested by their stated intentions (Makris Citation2018), parental choice is increasingly seen as the most significant factor in shaping school segregation patterns. In contrast, our article focused on the institutional context parents operate in when trying to uncover the institutional mechanisms behind school segregation. To gain a better understanding of the complex relationship between all these dimensions and mechanisms, a comparative perspective across different educational contexts is indispensable.

Based on a comparative analysis of two opposite policy reforms – introducing vs. reforming parental choice – and their local manifestations, our paper illustrates the effects of educational policies. By intervening in the institutional context of rules and incentives, which prohibits, enables or even encourages certain practices, education policies affect both parents’ and institutional actors’ room for manoeuvre. The introduction of parental choice in NRW, where for decades geography played a key role in school admission, sparked a surge of choice for schools outside the former catchment area, consequently culminating in increasing levels of school segregation. Correspondingly, in Amsterdam, modifying the choice opportunities of parents by coupling them to their place of residence seems to have mitigated school segregation levels.

However, the relationship between education policies and local segregation patterns is more complex than findings of ‘more choice leading to higher segregation levels, and less choice leading to lower segregation levels’, as suggested by Boterman and Ramos Lobato (Citation2022). While it is true that the organisation of parental choice has a crucial impact on school segregation, the way in which choice shapes local segregation patterns is additionally dependent on other aspects lying within and outside the education system. In Amsterdam, the new admission policies not only changed choice for parents but also made the admission process more transparent and predictable. By reducing the direct competition between schools and limiting the schools’ discretionary scope in admitting pupils, the reform may have impacted segregation levels. In NRW/Mülheim, the policy reform not only expanded parental choice but also changed the admission policies. By conveying the right to decide on the pupils’ admission to the principals without determining any clear criteria, the new legislation created a certain kind of fuzziness, which significantly increased the principals’ scope of discretion in selecting pupils (Ramos Lobato Citation2019) – potentially affecting school segregation patterns.

Parents’ school choices are not only a result of having the legal opportunity to choose but are equally dependent on the size of the set of choices embedded in the variation in the supply of schools. This is in particular the case in Amsterdam, where choice is strongly pronounced due to the highly differentiated system. In Mülheim/NRW, school choice is also informed by growing competition between increasingly differentiated primary schools, e.g. by varying school profiles and offers (Ramos Lobato Citation2017; Breidenstein, Krüger, and Roch Citation2020). Consequently, the former segregating role of denominational schools disappeared to a certain extent. While being the only opt-out option in the former catchment area system, in which choosing the denominational school was not necessarily a deliberate choice based on religious convictions, denominational primary schools today are only one of several options to avoid the neighbourhood schools.

Apart from the impact of different institutional aspects of the education system, school segregation in both case study areas is highly contingent on patterns of residential segregation. The mechanisms contributing to uneven distribution of pupils in schools are a result of a complex interplay between urban development, the institutional landscape, and parental choice. The effects of new modes of governing school segregation may have unforeseen consequences. For instance, spatially constraining choice could positively affect school segregation but might lead to an increase in residential segregation because the distance between home and school becomes the most important access criterion (see for instance Kauppinen, van Ham, and Bernelius Citation2020). Correspondingly, introducing school choice may change residential patterns as well. Moreover, introducing choice on par with school autonomy has different effects from when choice is coupled with a more centralised admission policy. Our analysis suggests that in dealing with educational inequalities of which school segregation is a key manifestation and often also a cause, it would be particularly important to deal with residential segregation at the same time. Social mix policies at the neighbourhood level should equally be much more aware of their consequences for school choice practices.

In this article, we demonstrated how education policies and the institutional mechanisms behind can shape local school segregation patterns. Even though (middle-class) parents’ selection strategies and their influential lobbying for free school choice is one of the more crucial dimensions in educational segregation and inequality, an at least similarly powerful factor is the political will to combat them. The parents’ right to select schools freely has always been one of the most defining aspects of the Dutch education system. Despite substantial criticism of the segregation it (co)produces (Karsten et al. Citation2003; Ladd, Fiske, and Ruijs Citation2009; Boterman 2019), unfettered school choice is a firmly embedded right that parents and schools value very highly. Suggesting limiting school choice, let alone abolishing it, is politically extremely sensitive (Paulle, Mijs, and Vink Citation2016). It may therefore not be a coincidence that the rationale given for the recent policy intervention did not mention desegregation directly, which is associated with curtailing choice. Instead, the policy intervention is presented as a way to strengthen the ties between the neighbourhoods and its schools. While this only marginally affects school choice, as evidenced by the higher than 95% acceptance rate at school, introducing a greater role for geography as well as more centralisation in admission policies still coincides with lower segregation levels. Moreover, it provides a foothold for new interventions that could mitigate segregation. Policies reducing choice directly are still difficult to implement, but the current policy intervention shows that indirect measures reducing the negotiating space for parents and schools may already take away some of the dynamics leading to segregation.

By way of contrast, in Germany, primary school choice is comparatively new. However, although the social-democratic coalition in NRW accused the ruling government of political patronage and one-sidedly favouring middle-class parents’ preferences when introducing free primary school choice in 2008, they did not dare to roll it back when they were elected in 2010. Rather, they preferred to ‘pass the buck’ to the local level leaving the decision whether to reintroduce catchment areas or not to the municipalities – in which the political majorities to withdraw parents’ rights could not be secured either (Ramos Lobato Citation2019). Once parents are equipped with the right to choose, this seems to have ‘opened a Pandora's box and generated needs difficult to withdraw’.Footnote8 This illustrates how politically sensitive the topic is – in both cases. A better understanding of the institutional mechanisms behind school segregation is thus crucial to shedding light on the opportunities and limits provided by school policy interventions to combat it, but this will remain insufficient without the indispensable political will and support behind it.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Willem Rogier Boterman

Willem Rogier Boterman is associate professor Urban Geography at the University of Amsterdam. He researchers the intersections of social class, geography and education.

Isabel Ramos Lobato

Isabel Ramos Lobato is postdoctoral researcher at Helsinki Institute of Urban and Regional Studies (URBARIA). She specializes in research on urban phenomena, such as socio-spatial segregation, education and neighbourhood change.

Notes

1 Mülheim an der Ruhr is henceforth referred to as ‘Mülheim’.

2 We refer to denominational schools as schools with a specific religious orientation.

3 This is possible since the sixteen states are responsible for education in Germany and can therefore decide upon their own regulations.

4 The modified isolation index calculates the weighted average proportion of pupils of a particular category (lower and highly educated parents) in schools minus the total proportion of that group at the aggregated level (here the city). Highly educated is defined as at least one parent completed college education (Bachelor). Lower educated refers to at most lower vocational training.

5 The dissimilarity index refers to the imbalance in the proportion of pupils of two groups (here those with parents with lower versus higher educational attainment and those with a migration background versus natives) in schools compared to the city’s average, ranging from 0 to 100. The index indicates the sum of the proportion of pupils of both groups required to bring all schools into balance with the city mean.

6 Parents are classified into three groups according to their educational attainment: the category ‘high educational attainment’ comprises all parents with at least a higher education entrance qualification (Abitur) or a university degree; ‘medium’ comprises all with a school-leaving qualification below the highest secondary school track, but with completed vocational education; and all parents without any completed vocational training (and without Abitur) are classified as ‘low educational attainment’.

7 According to the official statistics of the City of Mülheim, children with a ‘migration background’ are defined as such when they or their parents were not born in Germany or when one of the three does not have a German passport.

8 This is quote comes from an interview with a leading social-democratic (SPD) politician in NRW specialised in education policy. The interview was conducted by one of the authors as part of the original research project.

References

- Altrichter, Herbert, Johann Bacher, Martina Beham-Rabanser, Gertrud Nagy, and Daniela Wetzelhütter. 2011. “Neue Ungleichheiten durch freie Schulwahl? Die Auswirkungen einer Politik der freien Wahl der Primarschule auf das elterliche Schulwahlverhalten.” In Neue Steuerung – alte Ungleichheiten? Steuerung und Entwicklung im Bildungsbereich, edited by Fabian Dietrich, Martin Heinrich, and Nina Thieme, 305–326. Münster: Waxmann.

- Ball, Stephen J. 2003. Class Strategies and the Education Market: The Middle Classes and Social Advantage. London: Routledge.

- BBO. 2016. Jaarevaluatie Resultaten 1de jaar toelatingsbeleid Basisonderwijs Amsterdam Instroom schooljaar 2015–2016. Amsterdam: Breed Bestuurlijk Overleg.

- BBO. 2018. Jaarevaluatie Resultaten 3de jaar toelatingsbeleid Basisonderwijs Amsterdam Instroom schooljaar 2017–2018. Amsterdam: Breed Bestuurlijk Overleg.

- Bernelius, Venla, and Katja Vilkama. 2019. “Pupils on the Move: School Catchment Area Segregation and Residential Mobility of Urban Families.” Urban Studies 56 (15): 3095–3116.

- Bonal, Xavier, Adrián Zancajo, and Rosario Scandurra. 2019. “Residential Segregation and School Segregation of Foreign Students in Barcelona.” Urban Studies 56 (15): 3251–3273.

- Boterman, Willem Rogier. 2013. “Dealing with Diversity. Middle Class Family Households and the Issue of Black and White Schools in Amsterdam.” Urban Studies 50 (6): 1128–1145.

- Boterman, Willem Rogier. 2018. “School Segregation in the Free School Choice Context of Dutch Cities.” In Understanding School Segregation: Patterns, Causes and Consequences of Spatial Inequalities in Education, edited by Xavier Bonal, and Christián Bellei, 155–178. London: Bloomsbury.

- Boterman, W. R. 2019. “The Role of Geography in School Segregation in the Free Parental Choice Context of Dutch Cities.” Urban Studies 56 (15): 3074–3094.

- Boterman, Willem Rogier. 2020. “School Choice and School Segregation in the Context of Gentrifying Amsterdam.” Housing Studies, Online First, 1–22. doi:10.1080/02673037.2020.1829563

- Boterman, W. R. 2021. “Socio-Spatial Strategies of School Selection in a Free Parental Choice Context.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 46(4): 882–899.

- Boterman, Willem Rogier, Sako Musterd, Carolina Pacchi, and Costanzo Ranci. 2019. “School Segregation in Contemporary Cities: Socio-Spatial Dynamics, Institutional Context and Urban Outcomes.” Urban Studies 56 (15): 3055–3073.

- Boterman, Willem Rogier, and Isabel Ramos Lobato. 2022. “Local Segregation Patterns and Multilevel Education Policies.” In Handbook of Urban Social Policy, edited by Yuri Kazepov, Eduardo Barberis, and Roberta Cucca. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. doi:10.4337/9781788116152.

- Bourdieu, Pierre, and Jean-Claude Passeron. 1990. Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. London: Sage.

- Breidenstein, Georg, Jens Oliver Krüger, and Anna Roch. 2014. “‘Aber Elite würde ich’s vielleicht nicht nennen.‘ Zur Thematisierung von sozialer Segregation im elterlichen Diskurs zur Grundschulwahl.” Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaften 19: 165–180.

- Breidenstein, Georg, Jens Oliver Krüger, and Anna Roch. 2020. “Parents as ‘Customers’? The Perspective of the ‘Providers’ of School Education. A Case Study from Germany.” Comparative Education 56 (3): 409–422.

- Bridge, Gary. 2006. “It’s Not Just a Question of Taste: Gentrification, the Neighbourhood, and Cultural Capital.” Environment and Planning A 38 (10): 1965–1978.

- Burgess, Simon, Ellen Greaves, Anna Vignoles, and Deborah Wilson. 2011. “Parental Choice of Primary School in England: What Types of School Do Different Types of Family Really Have Available to Them?” Policy Studies 32 (5): 531–547.

- Cohen, Lotje, Willem Rogier Boterman, and Frederique Van Spijker. 2018. Monitor Diversiteit in het Basisonderwijs. Amsterdam: Onderzoek, Informatie en Statistiek Amsterdam.

- Cordini, Marta, Andrea Parma, and Costanzo Ranci. 2019. “‘White Flight’ in Milan: School Segregation as a Result of Home-to-School Mobility.” Urban Studies 56 (15): 3216–3233.

- Driessen, G., P. Sleegers, and F. Smit. 2008. “The Transition from Primary to Secondary Education: Meritocracy and Ethnicity.” European Sociological Review 24 (4): 527–542.

- Flint, John. 2007. “Faith Schools, Multiculturalism and Community Cohesion: Muslim and Roman Catholic State Schools in England and Scotland.” Policy & Politics 35 (2): 251–268.

- Forsey, Martin, Scott Davies, and Geoffrey Walford. 2008. The Globalisation of School Choice? Oxford: Symposium Books.

- Gamsu, S. (2016). Moving up and moving out: The re-location of elite and middle-class schools from central London to the suburbs. Urban Studies, 53(14), 2921–2938.

- Groos, Thomas. 2015. Gleich und gleich gesellt sich gern. Zu den sozialen Folgen freier Grundschulwahl. https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/de/publikationen/publikation/did/gleich-und-gleich-gesellt-sich-gern.

- Hamnett, Chris, and Tim Butler. 2013. “Distance, Education and Inequality.” Comparative Education 49 (3): 317–330.

- Holme, Jennifer Jellison. 2002. “Buying Homes, Buying Schools: School Choice and the Social Construction of School Quality.” Harvard Educational Review 72 (2): 177–206.

- Karsten, Sjoerd, Charles Felix, Guuske Ledoux, Wim Meijnen, Jaap Roeleveld, and Erik van Schooten. 2006. “Choosing Segregation or Integration? The Extent and Effects of Ethnic Segregation in Dutch Cities.” Education and Urban Society 38 (2): 228–247.

- Karsten, Sjoerd, Guuske Ledoux, Jaap Roeleveld, Charles Felix, and Dorothé Elshof. 2003. “School Choice and Ethnic Segregation.” Educational Policy 17 (4): 452–477.

- Kauppinen, Timo, Maarten van Ham, and Venla Bernelius. 2020. “Understanding the Effects of School Catchment Areas and Households with Children in Ethnic Residential Segregation.” Housing Studies, 1–25. doi:10.1080/02673037.2020.1857707.

- Klemm, Klaus, Lars Hoffmann, Kai Maaz, and Petra Stanat. 2018. Privatschulen in Deutschland. Trends und Leistungsvergleiche. http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/studienfoerderung/14189.pdf.

- Kosunen, Sonja. 2014. “Reputation and Parental Logics of Action in Local School Choice Space in Finland.” Journal of Education Policy 29 (4): 443–466.

- Kosunen, Sonja, Venla Bernelius, Piia Seppänen, and Miina Porkka. 2020. “School Choice to Lower Secondary Schools and Mechanisms of Segregation in Urban Finland.” Urban Education 55 (10): 1461–1488.

- Krüger, Jens Oliver, Anna Roch, and Georg Breidenstein. 2020. Szenarien der Grundschulwahl. Eine Untersuchung von Entscheidungsdiskursen am Übergang zum Primarbereich. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Ladd, Helen F., Edward Fiske, and Nienke Ruijs. 2009. “Parental Choice in the Netherlands: Growing Concerns about Segregation.” National Conference on School Choice, Vanderbilt University.

- Landtag Nordrhein-Westfalen (NRW). 2018. Schulgesetz für das Land Nordrhein-Westfalen. https://www.schulministerium.nrw.de/docs/Recht/Schulrecht/Schulgesetz/Schulgesetz.pdf.

- Ledwith, Valerie, and Kathy Reilly. 2013. “Accommodating All Applicants? School Choice and the Regulation of Enrolment in Ireland.” The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien 57 (3): 318–326.

- Logan, John R., Deirdre Oakley, and Jacob Stowell. 2008. “School Segregation in Metropolitan Regions, 1970–2000: The Impacts of Policy Choices on Public Education.” American Journal of Sociology 113 (6): 1611–1644.

- Lubienski, Christopher, Laura B. Perry, Jinaand Kim, and Yusuf Canbolat. 2022. “Market Models and Segregation: Examining Mechanisms of Student Sorting.” Comparative Education, 1–21. doi:10.1080/03050068.2021.2013043

- Makris, Molly Vollman. 2018. “The Chimera of Choice: Gentrification, School Choice, and Community.” Peabody Journal of Education 93 (4): 411–429.

- Merry, Michael S., and Willem R. Boterman. 2020. “Educational Inequality and State-Sponsored Elite Education: The Case of the Dutch Gymnasium.” Comparative Education 56 (4): 522–546.

- Merry, Michael S., and Geert Driessen. 2005. “Islamic Schools in Three Western Countries: Policy and Procedure.” Comparative Education 41 (4): 411–432.

- Morris, Rebecca. 2015. “Free Schools and Disadvantaged Intakes.” British Educational Research Journal 41 (4): 535–552.

- MSW NRW (Ministerium für Schule und Weiterbildung des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen). 2005. Abschaffung der Schulbezirke. https://www.kommunen-in-nrw.de/mitgliederbereich/mitteilungen/detailansicht/dokument/abschaffung-der-schulbe-zirke-1.html?cHash=ef2022c7b2e2405e89e874b32273cfbe.

- Noreisch, Kathleen. 2007. “School Catchment Area Evasion: The Case of Berlin, Germany.” Journal of Education Policy 22 (1): 69–90.

- Oberti, Marco, and Yannick Savina. 2019. “Urban and School Segregation in Paris: The Complexity of Contextual Effects on School Achievement: The Case of Middle Schools in the Paris Metropolitan Area.” Urban Studies 56 (15): 3117–3142.

- OECD. 2014. Education Policy Outlook – Netherlands. http://www.oecd.org/education/EDUCATION%20POLICY%20OUTLOOK_NETHERLANDS_EN%20.pdf.

- Paulle, Bowen, Jonathan Mijs, and Anja Vink. 2016. “Nieuw systeem, nieuwe kansen?: Ouders in Amsterdam-West over (de) segregatie in het basisonderwijs.” B en M: Tijdschrift voor Beleid, Politiek en Maatschappij 43 (3): 4-22.

- Perry, Laura B., Emma Rowe, and Christopher Lubienski. 2022. “School Segregation: Theoretical Insights and Future Directions.” Comparative Education, 1–15. doi:10.1080/03050068.2021.2021066

- PO Raad. 2019. https://www.poraad.nl/nieuws-en-achtergronden/vrijwillige-ouderbijdrage-blijft-stabiel, Website visited March 24th 2021.

- Ramos Lobato, Isabel. 2017. “‘I Do Not Want to Poach Pupils from Other Schools’ – German Primary Schools and Their Role in Educational Choice Processes.” Société Royale Belge De Géographie 2 (2-3). doi:10.4000/belgeo.19131.

- Ramos Lobato, Isabel. 2019. Free Primary School Choice, Parental Networks, and their Impact on Educational Strategies and Segregation (dissertation). Bochum: Ruhr-Universität Bochum.

- Ramos Lobato, Isabel, and Thomas Groos. 2019. “Choice as a Duty? The Abolition of Primary School Catchment Areas in North Rhine-Westphalia/Germany and Its Impact on Parent Choice Strategies.” Urban Studies 56 (15): 3274–3291.

- Raveaud, Maroussia, and Agnès van Zanten. 2007. “Choosing the Local School: Middle Class Parents’ Values and Social and Ethnic Mix in London and Paris.” Journal of Education Policy 22 (1): 107–124.

- Reardon, Sean F., and Ann Owens. 2014. “60 Years After Brown: Trends and Consequences of School Segregation.” Annual Review of Sociology 40: 199–218.

- Renzulli, Linda A., and Lorraine Evans. 2005. “School Choice, Charter Schools, and White Flight.” Social Problems 52 (3): 398–418.

- Riedel, Andrea, Kerstin Schneider, Claudia Schuchart, and Horst Weishaupt. 2010. “School Choice in German Primary Schools: How Binding are School Districts?” Journal for Educational Research Online 2 (1): 94–120.

- Skovgaard Nielsen, Rikke, and Hans Thor Andersen. 2019. “Ethnic School Segregation in Copenhagen: A Step in the Right Direction?” Urban Studies 56 (15): 3234–3250.

- Valenzuela, Juan Pablo, Cristian Bellei, and Danae de los Ríos. 2014. “Socioeconomic School Segregation in a Market-Oriented Educational System. The Case of Chile.” Journal of Education Policy 29 (2): 217–241.

- Van de Werfhorst, Herman G., and Jonathan J. Mijs. 2010. “Achievement Inequality and the Institutional Structure of Educational Systems: A Comparative Perspective.” Annual Review of Sociology 36: 407–428.

- van Zanten, Agnès, and Sonja Kosunen. 2013. “School Choice Research in Five European Countries: The Circulation of Stephen Ball’s Concepts and Interpretations.” London Review of Education 11 (3): 239–255.

- Verger, Antoni, Mauro C. Moschetti, and Clara Fontdevila. 2020. “How and Why Policy Design Matters: Understanding the Diverging Effects of Public-Private Partnerships in Education.” Comparative Education 56 (2): 278–303. doi:10.1080/03050068.2020.1744239.

- Vowden, Kim James. 2012. “Safety in Numbers? Middle-Class Parents and Social Mix in London Primary Schools.” Journal of Education Policy 27 (6): 731–745.

- Wilson, Deborah, and Gary Bridge. 2019. “School Choice and the City: Geographies of Allocation and Segregation.” Urban Studies 56 (15): 3198–3215.