ABSTRACT

Every teacher’s classroom practice is embedded in a system of overlapping contexts that interact with their day-to-day decisions. In this paper, I focus on sociocultural context and how it interacts with teachers’ subjective responses to accountability instruments. Drawing on interviews with secondary school teachers in Finland and Singapore – education systems with contrasting but comparably effective approaches to teacher accountability – I find that one way in which sociocultural context interacts with teachers’ experiences of accountability instruments is by influencing the mental models of motivation that shape their responses to these instruments. This finding is relevant to two contentious areas in education policy. First, it suggests that teacher accountability policy is a socioculturally embedded matter, implying a need for caution rather than recommending specific forms of accountability across the board. Second, it adds to the growing body of evidence demonstrating that ‘best practices’ from high-performing education systems are contingent on implementation contexts.

摘要

每位教师的课堂实践都根植于一个与他们日常决策相互作用的多重环境系统。 在本文中,我关注社会文化环境,以及它如何与教师对问责工具的主观回应相互作用。芬兰与新加坡的教育体制都拥有对教师问责的有效方法,二者不同但具有对比性。通过对两国中学教师的访谈,我发现,社会文化环境与教师对问责工具的体验相互作用的一种方式,是通过影响教师动机的心理模型,塑造他们对这些工具的回应。这一发现与教育政策中两个有争议的领域有关。首先,它表明教师问责政策是一个根植于社会文化的议题,这意味着要审慎而不能一刀切地推荐具体的问责形式。其次,越来越多的证据表明,具有优异表现的教育体制之“最佳实践”取决于实施的背景,本文为这一观点增添佐证。

Introduction

Although teachers practice their craft within localised classroom, their practice is embedded in broader domains and is influenced by factors and trends within these domains. One such trend is the widespread (although not uniform) influence and perceived legitimacy of outcome-based accountability in education (Högberg and Lindgren Citation2021; Verger and Parcerisa Citation2017). Another is the increasingly widespread recognition, even in publications focused on international ‘best practices’ in education (e.g. Mourshed, Chijioke, and Barber Citation2010), that context matters in education policy.

However, this acknowledgement of context does not always manifest in action (Auld and Morris Citation2016). To give an example from accountability policy, a consistently implemented, ‘best practices’-inspired school quality assurance programme in Madhya Pradesh, India, had no effect on either teacher practice or student outcomes – yet a modified version of this programme is being rolled out nationally because it carries political legitimacy (Muralidharan and Singh Citation2020). Notably, a key reason for its ineffectiveness was contextual mismatch. Despite extensive piloting of the accountability instruments in local schools, teachers viewed the programme as another administrative box to tick rather than a tool for improving their core work (Muralidharan and Singh Citation2020; see also Müller and Hernández Citation2010). This illustrates the risks of addressing just the material and quantifiable aspects of context, without considering those aspects related to perceptions, beliefs, and other sociocultural patterns.

Crossley and Watson (Citation2003) suggest that this relative neglect of context in education policy may be due to inadequate integration in educational research between the policy-oriented strand that often discounts ‘the importance of contextual and cultural factors’ (120) and the theoretically-oriented strand that is often ‘divorced from the real world of educational policy and practice’ (121). Some scholars have integrated these two strands to make the case for incorporating sociocultural context into accountability policy, whether using tools from the theory-oriented strand to argue that current accountability policies emerge from deep political and sociocultural roots (e.g. Hopmann Citation2008; You Citation2017), or using datasets from the policy-oriented strand to argue that the results of these international large-scale student assessments that fuel interest in decontextualised ‘best practices’ are themselves contingent on sociocultural factors (e.g. Feniger and Lefstein Citation2014; Hwa Citation2021b). In this study, I complement these arguments by looking at the interplay between sociocultural context and teachers’ subjective responses to accountability policy.

To do so, I draw on interviews with secondary school teachers in Finland and Singapore, both of which are lionised as educational ‘reference societies’ (de Roock and Espeña Citation2018; Takayama, Waldow, and Sung Citation2013). Beyond their highly successful school systems, Finland and Singapore have distinct sociocultural contexts, which will be discussed below, and contrasting approaches to teacher accountability, which Högberg and Lindgren (Citation2021) would classify as ‘thin’ and ‘thick’ accountability regimes, respectively.Footnote1 In Finland, teachers are not subject to formal appraisals, and formal rewards and punishments are minimal (Sahlberg Citation2015). In contrast, Singaporean teachers’ work is managed within a national system of tiered performance standards and formal appraisals, with a structured career ladder and sizeable bonuses (Sclafani and Lim Citation2008).

The question driving this study is: How does sociocultural context affect teachers’ interactions with accountability instruments in Finland and Singapore? Among the range of sociocultural patterns that influence teachers’ subjective choices and actions, I focus on motivation-related patterns because popular arguments for teacher accountability reforms are often linked to motivation. For example, in the McKinsey report How the World’s Most Improved School Systems Keep Getting Better, one of the three ‘intervention clusters’ for moving an education system from ‘poor’ to ‘fair’ performance is ‘Providing scaffolding and motivation for low skill teachers and principals’, which includes giving ‘rewards (monetary and prestige) to schools and teachers who achieve high improvement in student outcomes against targets’ (Mourshed, Chijioke, and Barber Citation2010, 30). To preview the argument, I find that one way in which sociocultural context affects teachers’ interactions with accountability instruments is by influencing the mental models of motivation that shape their subjective responses to these instruments. One implication of this analysis is that compatibility with sociocultural context is pivotal to effective interactions between teacher accountability instruments and teacher motivation. As a Finnish interview participant said, ‘Our system fits us.’

This is not an argument about unidirectional causality, but rather about interactive embeddedness. Below, I draw on Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1979) ecological schema to map this embeddedness. Although teachers’ subjective responses are nested within sociocultural contexts, and although this analysis focuses on the influence of the latter on the former, it would be inaccurate to suggest that teachers play no role in shaping the sociocultural landscape (or in informing accountability policy). Over time, teachers’ choices and actions undoubtedly exert a cumulative and collective influence on both of these domains. However, I focus on the influence of sociocultural context on teachers’ subjective responses to accountability instruments because this analysis is situated within a larger body of research calling attention to the importance of context in policy.

Note also that descriptions of ‘sociocultural context in Finland’ and ‘sociocultural context in Singapore’ are not intended as an affirmation of methodological nationalism. Cultural patterns do not divide neatly along national borders, instead showing both within-country variation and cross-border influences (Anderson-Levitt Citation2012). I focus on national-level culture simply because I was interested in national-level differences in teacher accountability policy and lacked the resources to examine other levels of sociocultural variegation. Additionally, this national-level lens appeared to be meaningful to the teachers I interviewed, with participants speaking of constructs like ‘the Finnish mind’ and ‘a Singapore identity’.

Literature review

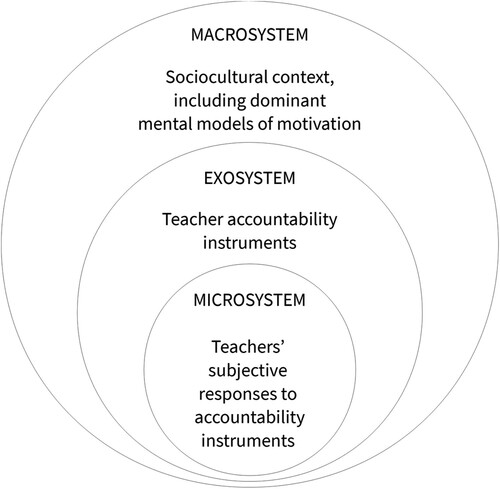

As noted above, the research question focuses on embeddedness and interactions between teachers’ subjectivity, teacher accountability instruments, and sociocultural contexts. To organise these constructs, I use a version of Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1979) ecological schema. Besides its analytical utility, I chose this schema because of its apposite origins at the intersection between theory and policy – as a developmental psychologist, Bronfenbrenner was an architect of the US government’s Head Start programme for low-income children (Bronfenbrenner’s Citation1979).

As shown in , I modify the schema to centre on the teacher rather than on the developing child. For simplicity’s sake, I include only the main constructs of interest. Thus, teachers’ subjective responses fall within the microsystem, teacher accountability instruments fall within the exosystem, and sociocultural context falls within the macrosystem. Each construct/level is described further below. (I exclude mesosystems, which comprise interactions between different microsystems, because the analysis involves single microsystem.) This use of Bronfenbrenner’s framework is not intended to be theory-building, not least because I do not engage with the nuances of his theory of human development. Rather, I use it simply to lend some structure to the analysis (For a similar use of Bronfenbrenner’s schema, see Ehren and Baxter Citation2021.).

Figure 1. Mapping of the main constructs in this study to Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1979) ecological schema.

Macrosystem: sociocultural context

In Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1979) schema, macrosystems are ‘consistencies … at the level of the subculture or culture as a whole, along with any belief systems or ideology underlying such consistencies’, such that it appears as though ‘the various settings had been constructed from the same set of blueprints’ (p. 26). Thus, the macrosystem encapsulates what I term sociocultural context, or dominant patterns of ideas and practices in social system that influence people’s interactions with their environments. This definition is intentionally broad to encapsulate any macro-level sociocultural features that interview participants view as salient to teacher accountability. It aligns with arguments from both realist-informed educational research (Maxwell Citation2012) and cultural psychology (Markus and Kitayama Citation2010) that culture is situated not in individuals but in systems of interactions between individuals, institutions, and ideas.

One example of the influence of macro-level sociocultural context on teachers’ micro-level practice is the influence of culture on teaching practice, as in Stigler and Hiebert’s (Citation1999) discussion of ‘cultural scripts’ underlying cross-country differences in classroom practice or in Alexander’s (Citation2001) Culture and Pedagogy. In Finland (Simola et al. Citation2017, chap. 6) and in Singapore (Heng and Song Citation2020), scholars have documented instances where sociocultural context hampered policies emphasising individualised/differentiated pedagogy. In this analysis, I focus on consistencies in what I call teachers’ mental models of motivation, described below.

Exosystem: teacher accountability instruments

Bronfenbrenner (Citation1979) defines exosystems as ‘settings that do not involve the developing person as an active participant, but in which events occur that affect, or are affected by, what happens in the setting containing the developing person’ (p. 25). In studying teachers and teacher accountability rather than child development, the relevant exosystem-level construct is teacher accountability instruments, which affect and are affected by teachers even though teachers are rarely active participants in their formulation. By teacher accountability instruments, I mean tools, practices, and structures that aim to orient teacher practice toward stakeholder expectations by collecting information about teacher practice and communicating this information to stakeholders, setting standards by which stakeholders judge teacher practice, and allocating consequences based on stakeholders’ judgements of teachers’ practice. This definition draws on Bovens’ (Citation2007) emphasis on the relational nature of accountability (in this case, between teachers and stakeholders, who can include fellow teachers) as well as Romzek and Dubnick’s (Citation1987) argument that managing expectations and standards is central to accountability.

Although recent years have seen substantial cross-country attention to outcomes-based accountability, teacher accountability instruments are also shaped by the country-level macrosystem in which they are embedded. For example, Hopmann (Citation2008) attributes the different emphases of accountability policies in the USA, Nordic countries, Germany, and Austria to ‘deeply engrained ways of understanding the relation between the public and its institutions’ (p. 425). Beyond accountability, comparative studies of the interplay between international policy trends, macrosystemic context, and exosystem-level education policy include analyses of higher education governance in Finland and Sweden (Holmén Citation2022) and transitions from colonial to post-colonial schooling in Singapore and Cyprus (Klerides Citation2021).

Besides its interactions with macro-level sociocultural contexts, exosystem-level accountability policy also interacts with teachers’ micro-level choices, actions, and perceptions. Scholars have documented the influence of accountability-related policy on teachers’ conceptions of their professional identity in Singapore (Liew Citation2012) and the USA (Holloway and Brass Citation2018), as well as England, France, and Denmark (Osborn Citation2006). I turn to these micro-level subjectivities next.

Microsystem: teachers’ subjective responses

A microsystem is ‘a pattern of activities, roles, and interpersonal relations experienced by the developing person in a given setting with particular physical and material characteristics’ (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979, 22). Bronfenbrenner thus emphasises not the objective characteristics of a setting, but rather the subjective experience of the person in question.

Similarly, in the microsystem of a teacher’s responses to accountability instruments, there is a basis in comparative education research for expecting the relationship between accountability instruments and teacher practice to depend on teachers’ subjective perspectives. As Broadfoot and Osborn (Citation1993) argue in their study of teachers in France and England:

All too often … directives are concerned with changing what teachers do without taking any account of how teachers’ thinking might need to change if such changes are to be seen as acceptable and thus become incorporated as part of teachers’ own internal professional goals. (127, emphasis original)

Teachers’ subjective responses (microsystem) to accountability instruments (formulated in the exosystem) are themselves influenced by sociocultural patterns (macrosystem) – just as culture influences teachers’ pedagogical practice, as noted above. For example, a teacher quality reform in Indonesia included a peer evaluation scheme, but hierarchical sociocultural expectations meant that teachers questioned colleagues’ authority to evaluate their work, believing that such authority should only be held by supervisors or headteachers (Broekman Citation2016). Similarly, some teachers in India challenged community accountability structures because they expected to be treated as high-status professionals beyond the purview of low-status villagers (Narwana Citation2015). Mizel’s (Citation2009) study of Israeli Bedouin schooling found that headteachers prioritised reporting students’ behavioural transgressions to the tribal sheikh over reporting on curriculum and lesson planning to the education ministry. Thus, macro-level sociocultural patterns can affect the implementation of exosystem-designed accountability instruments by influencing teachers’ micro-level responses.

Macro-level consistencies in mental models of micro-level motivation

One process (among others) through which the macrosystemic sociocultural context may influence teachers’ responses to accountability instruments relates to motivation, which many accountability reforms attempt to raise. For conceptual clarity, I adopt Schunk, Pintrich, and Meece’s (Citation2010) definition of motivation as ‘the process whereby goal-directed activity is instigated and sustained’ (4).

Although the general outlines of major theories of human motivation are commonly regarded to have cross-cultural validity, empirical studies in psychology have found that the factors emphasised in these theories manifest in diverse configurations, interpretations, and narratives across cultural contexts (King and McInerney Citation2016). For example, Ryan and Deci’s (Citation2000a) self-determination theory proposes that intrinsic motivation is sustained when the actor’s needs for autonomy, a sense of competence, and relatedness to others are fulfilled. Yet experimental work has found that Anglo-American children had higher intrinsic motivation when they were free to choose their own tasks, whereas Asian-American children had higher intrinsic motivation when the task was ostensibly chosen by their mothers or classmates (Iyengar and Lepper Citation1999). This implies that conceptions of ‘autonomy’ are contingent on culture. In turn, Vroom’s (Citation1964) expectancy theory centres on three motivational factors: expectancy, the belief that effort will lead to successful performance; instrumentality, the belief that successful performance will lead to desired outcomes; and valence, or the value that the actor expects to gain from these outcomes. Yet experimental work has found that East Asian undergraduates were more likely than their European American counterparts to increase their effort in a mathematics task upon being reminded that mathematics can be instrumental for valued goals (Shechter et al. Citation2011).

Studies of teachers’ beliefs and motivation also suggest that sociocultural context shapes teachers’ motivation-related beliefs and responses. In a cross-cultural analysis of teacher motivation in Western and Chinese contexts, Ho and Hau (Citation2014) concluded that some motivational processes function similarly across contexts (e.g. the association between high intrinsic motivation and positive teacher practices), whereas other aspects of motivation are culture-dependent (e.g. teachers’ goals and values). Similarly, Hufton, Elliott, and Illushin (Citation2003) found that teachers in the UK, the USA, and Russia differed in their beliefs about some aspects of student motivation, such as the extent to which students should be praised and criticised. More generally, Watt and Richardson (Citation2015) argue for greater cross-fertilisation between research on teacher motivation and teacher beliefs, including sociocultural beliefs.

In analysing the interview data, I found that the influence of sociocultural context on teachers’ subjective responses to accountability instruments could be distinctly traced via teachers’ implicit mental models of motivation (MMM). By MMMs, I mean the configurations of factors that teachers believe will support or inhibit the process by which goal-directed activity is instigated or sustained (drawing on the Schunk et al. Citation2010 definition of motivation quoted above). I focus on macro-level sociocultural consistencies (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979) related to motivation. This is not to imply that teachers’ subjective responses to accountability instruments can be reduced to motivation, nor that MMMs are the only relevant macrosystemic influence on such responses. Nonetheless, I emphasise teacher motivation because, from a policy standpoint, many teacher accountability instruments implicitly or explicitly aim to raise or reorient teacher motivation, as noted above. From a conceptual standpoint, motivation relates to goal-directed behaviour – which can be mapped onto to the expectations implicit in accountability instruments.

Research methods

To explore the relationship between these constructs, I use semi-structured individual interviews with 12 teachers from 11 secondary schools in Singapore as well as 12 teachers from 10 lower secondary schools in Finland. These levels of schooling were chosen to match the levels of students participating in PISA (age 15) and TIMSS (Grade 8), because I draw on PISA and TIMSS data for a related analysis on teacher accountability, teacher motivation, and sociocultural context (Hwa Citation2021b). I conducted the interviews in July–August 2018 (Singapore) and September 2018 (Finland).

For teacher-level variation, I spoke with teachers across a range of subjects, teaching experience, management roles, and of personal characteristics such as ethnolinguistic background and gender. For school-level variation, in Singapore, I interviewed teachers from a mix of ‘mainstream’ schools and autonomous/independent schools, which have more administrative flexibility and tend to have higher test scores and greater prestige. In Finland, teachers in the interview sample taught at not only public Finnish-speaking schools, but also private schools and Swedish-speaking schools. Their schools spanned eight municipalities, which mattered because (unlike in Singapore’s centralised school system) educational resources and governance can differ across municipal administrations. Participants were identified through personal and educational networks.

All 24 participants were interviewed using the same interview guide, which I had previously piloted with a Singaporean teacher, a Singaporean Ministry official, and a Finnish principal. In line with realist approaches to research, the aim of these interviews was to refine my working theory of teacher accountability instruments (Maxwell Citation2012). Accordingly, interview questions were framed around an initial conceptual framework for the larger project in which this study is embedded (Hwa Citation2019). Interviews were conducted in English at a location of the participant’s choosing and lasted an average of 61 min. In both countries, the interviews reached saturation, with additional participants adding details based on their particular experiences but broadly echoing what others had said. Subsequently, I transcribed the interviews and assigned pseudonyms to each participant. Transcripts were coded in QDA Miner Lite, beginning with a preliminary coding scheme and adding subcategories and codes inductively as the analysis proceeded.

Findings

Teachers’ subjective responses to accountability instruments

To begin with accountability instruments originating from a teacher’s exosystem, Finland has what Högberg and Lindgren (Citation2021) call a ‘thin’ accountability regime, with relatively few instruments for monitoring and managing teacher practice. According to Finnish interview participant Antero:

When they selected me to study teaching, of course they checked that my personality and who I am fits the job. And after that, I have been on my own. Nobody has come here to say that, ‘You must change. And you must do it like this, not like that.’ I am in charge here. (also quoted in Hwa Citation2021a, 240)

In contrast, Singaporean teachers experience a ‘thick’ accountability regime (Högberg and Lindgren Citation2021), with substantial top-down accountability centred on the Enhanced Performance Management System (EPMS) for high-stakes teacher appraisal. According to Singaporean participant Sonia:

The EPMS is something that drives all the teachers in Singapore. A lot of us peg ourselves to the targets set for us, set by us, according to this EPMS framework, just to ensure that we do not end up being penalised.

Differences notwithstanding, one commonality between the Singaporean and Finnish systems is that teachers’ responses to accountability instruments are contingent on their micro-level subjective perspectives. This is apparent in the diversity of teachers’ views about these instruments and, consequently, the heterogeneity of their responses to them. When discussing Finland’s light-touch approach to teacher accountability, Satu observed that:

The freedom for me is like, ‘I can do everything.’ (laughter) ‘I can make a hundred exercises for the students if I want to.’ And some of my colleagues think that even one exercise is too much. So the freedom has two sides.

It depends on individual teachers and their convictions. For me, I believe that nurturing the child’s character is more important. So if I need to, I would focus more on the child rather than on the lesson.

Sociocultural context and teachers’ mental models of motivation

Although teachers’ subjective responses to accountability instruments can differ considerably, there were clear macrosystemic consistencies in participants’ descriptions of their own and their colleagues’ subjective responses. I posit that one reason for this consistency is that teachers’ responses to accountability instruments are influenced by their mental models of motivation (MMMs), which are themselves influenced by dominant sociocultural patterns. Before examining the relationship between responses to accountability instruments and MMMs (in the next subsection), I first examine the relationship between participants’ MMMs and their accounts of the sociocultural contexts in which they are embedded.

In their descriptions of accountability instruments, there were clear differences between the MMMs that were dominant among Finnish and Singaporean participants. This finding emerged inductively. Having identified interview quotations where participants linked teacher motivation, accountability instruments, and sociocultural context, I reviewed a range of psychological theories of motivation with the aim of identifying an empirically validated framework to clarify and organise the analysis. However, none of the major theories (as identified by Schunk, Pintrich, and Meece Citation2010; Vroom and Deci Citation1992) emphasised motivational factors that were equally salient to the interview data from both countries – but two separate theories of motivation did overlap with the dominant MMMs that were implicit in the Finland and Singapore interviews, respectively.

When discussing motivation, Finnish participants often linked it to the competence, relatedness, and autonomy that Ryan and Deci (Citation2000a) regard as fundamental to intrinsic motivation. For example, when I asked Juhani how sociocultural context influences teacher accountability, he said:

There’s something called Finnish sisu or stubbornness. Teachers are the kind of persons who are stubborn enough to feel the needs that the surrounding society gives them, and they will meet them. And they are also flexible enough to do it in a way that is quite effective.

This intrinsically driven MMM is closely related to Finnish participants’ beliefs about the larger sociocultural context. After observing that Finnish teachers are more effective when they can work autonomously, Anneli added, ‘But that’s probably because our society is based on trust. In so many ways. So that’s why it works.’ This trust is not a carte blanche. Rather, it is based on the expectation that other members of society will likewise fulfil their complementary responsibilities. In Päivi’s words:

Finnish people know what’s wrong, and what’s right. And they are very interested if someone near them isn’t doing right. So I think teachers know very well if they’re doing right or wrong, and if the other teachers are doing right or wrong. It’s very much part of our culture.

Singaporean participants emphasised a different set of motivational factors. While saying that ‘remuneration […] is never a good way to assess the worth or value of a teacher’, Eleanor also noted that ‘Singapore’s a very expensive country to live in, so [remuneration] does matter to a large number of people’. To use Vroom’s (Citation1964) terminology, salaries and bonuses have a large positive valence for many Singaporeans. This valence, together with the belief that good performance is reliably instrumental in reaping such rewards, can influence teachers’ outlooks. According to Adeline, ‘Singaporean teachers are very typical civil servants, and they like to have their various KPIs [key performance indicators] and know that if they meet them, they might get rewarded’ (also quoted in Hwa Citation2021a, 331). Faced with this reward structure, teachers may redirect their effort in line with expectancies of performance, as Jane observed:

Some teachers may feel that certain areas are less debatable, like exam results, so they will chiong [i.e. rush towards, put effort into] that area. Then maybe you look at your CCA [cocurricular activity]: ‘Oh dear, it’s not possible.’ Whatever you do, it will be very hard [to win the inter-school competition], because maybe there’s another champion school in your zone already. So you strategise in this way.

Strikingly, echoes of expectancy theory appeared even in the observations of participants who themselves disavowed Singapore’s competitive, progression-oriented system. For example, Andy noted that Singapore’s oft-discussed kiasu mentality – a hard-nosed competitiveness, from the Chinese Hokkien term for ‘afraid of losing’Footnote2 – does not apply to him and his ‘band of merry colleagues who are just interested in developing the students’. However, he added that ‘we do recognise those who are deserving of credit because […] something about them enables them to go above and beyond for the students, and we don’t begrudge them if they are rewarded accordingly’. Thus, despite opting out of the meritocratic race, he endorsed its instrumentality, stating that superior performance is ‘deserving of credit’. This principle underpins the meritocracy that dominates Singapore’s sociocultural context (Tan Citation2018).

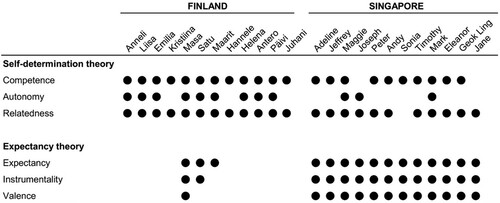

As noted above, the correspondence between Finnish participants’ MMM and Ryan and Deci’s self-determination theory as well as the correspondence between Singaporean participants’ MMM and Vroom’s expectancy theory was an observation that emerged inductively. To address the possibility that this observed divergence between Finnish and Singaporean participants’ MMMs arose from researcher bias (e.g. if my expectation that I would observe sociocultural differences primed me to over-read into the data), I reanalysed all interview quotes in which participants mentioned an accountability instrument having any sort of effect on teacher motivation. (I had extracted these quotes for a separate analysis, prior to noticing the difference in dominant MMMs.) In this reanalysis, I coded each time one of the quotes referred to a motivational factor in Ryan and Deci’s theory – autonomy, competence, and relatedness – or to a factor in Vroom’s theory – expectancy, instrumentality, and valence. This analysis is summarised in . While a few Finnish participants mentioned expectancy, instrumentality, and valence as factors that can influence teacher motivation, all of them mentioned competence and relatedness as such, and three-quarters mentioned autonomy. Moreover, while most Singaporean participants also mentioned competence and relatedness as influences (which is unsurprising given that all participants appeared to have high intrinsic motivation), every participant mentioned all three factors emphasised in Vroom’s theory. This suggests that the distinct MMMs described above are not merely an artefact of biased data analysis.

Figure 2. Summary of motivational factors mentioned by interview participants in discussing the effects of teacher accountability instruments on motivation.

To summarise, Finnish and Singaporean participants appeared to have different mental models of how motivation operates. This does not imply that Singaporean participants did not care about autonomy, nor that Finnish participants did not desire any high-valence outcomes. However, these constructs were not relevant to their implicit mental models of factors that affect motivation. These MMMs map onto distinct psychological theories of motivation, and cohere with the broader sociocultural contexts.

It is important to note that these mental models are not universally shared within each setting. Both Finnish and Singaporean participants described some colleagues whose individual MMMs appeared to be more coherent with the dominant MMM of the other context. However, participants viewed such teachers as exceptions to the norm.

Mental models of motivation and teachers’ responses to accountability instruments

Thus far, I have shown that Finnish and Singaporean teachers’ micro-level responses to accountability instruments are varied and subjective rather than uniform and mechanistic. Variation notwithstanding, I have also shown that the dominant MMMs within each context reflect macro-level sociocultural consistencies. In this subsection, I draw a connection between these two sets of findings by showing that teachers’ micro-level responses to exosystem-derived accountability instruments are shaped by macro-level MMMs. I show this connection by tracing the MMMs implicit in, firstly, participants’ descriptions of what works well in their country’s accountability systems and, secondly, their descriptions of divergences between teachers’ responses and policymakers’ apparent intent.

In Finland, initial teacher education plays a vital role in enabling the ‘thin’ in-service teacher accountability regime. Besides the selective admission process, as mentioned above by Antero, the rigorous training reinforces teachers’ motivation. Masa observed that:

Finnish teachers have a master’s degree. There’s this sort of professional pride […] and a level of respect that goes with being a teacher. […] And I think the combination of those factors means that the internal [desire to excel] from the teacher is more important than anything else.

Importantly, Finnish teachers are not only competent enough to fulfil their responsibilities, but they also feel competent. When describing how teachers respond to curricular change, Liisa said, ‘We know what we’re supposed to be doing, and then we do it.’ Later in the interview, Liisa’s observations about the national curriculum also indicated a sense of relatedness: the curriculum provides ‘a common ground for the students’. She also emphasised that ‘there’s no teacher who’s not aware of the curriculum’ – which was borne out across all my interviews with Finnish participants. Thus, teachers are united in following the same guidelines to serve students, reinforcing both collegial and societal relatedness.

Collegial relatedness among Finnish teachers is also maintained by the common pay structure. Anneli said that teachers ‘should get paid equally’ because they all held similar qualifications, so ‘the baseline is that every teacher is as competent as everybody else’. Similarly, Emilia noted that:

If you have a lot of rewards and people are evaluated against each other, then that makes a lot more competition, and that would eat away at collaboration. […] I wouldn’t say no to more money, (laughter) but I’m very happy that we don’t have a system of rewards and punishments, actually.

Singapore’s teacher accountability approach, centred on the EPMS, follows a different but equally coherent logic. According to Mark:

On one hand, most teachers view the EPMS […] like any rule that the government puts out, so they have to abide by it. But they do believe that it’s another example of the meritocracy in action. […] That the harder they work, the more strategic they are about their work, the higher their performance ranking, and the larger their performance bonus would be.

However, the accountability system also influences teachers for whom performance bonuses have little valence, at least in some cases. For example, Joseph believed that most teachers were in the profession ‘not for extrinsic reasons, but mainly for intrinsic reasons’. Instead, his teaching experience had ‘really made [him] really believe in what MOE wants’ because ‘over time you realise the value of your work’. Thus, his motivation is rooted in ‘the value of [his] work’, implying a different category of outcomes. Financial rewards may have low valence for Joseph, but he is driven by the valence of ‘what MOE wants’, i.e. a vision of shared productivity for Singapore’s survival. Four other Singaporean participants (Peter, Geok Ling, Jane, and Timothy) also accorded little value to EPMS rewards but likewise said that the Ministry’s expectations of teachers broadly overlapped with their own. Hence, the EPMS facilitates alignment between the teachers whose goals are chiefly altruistic, and those whose goals are chiefly pecuniary.

The EPMS is also designed to foster alignment between teacher appraisal standards nationwide. This matters because perceived unfairness in EMPS appraisals can be highly demotivating. In Maggie’s words, such unfairness makes you ‘feel that whatever effort you put in is not worth it [emphasis added]’. To use Vroom’s (Citation1964) terminology, teachers will only be motivated if they believe that good performance is instrumental for desirable rewards. Peter noted that reporting officers who are unfair or who do not convey their expectations clearly ‘can be quite demoralising for a teacher who’s put in a lot of effort, and then maybe is told that it’s not good enough, or just does not get any validation for it’. The Ministry invests considerable resources into forestalling a level of unfairness that could compromise EPMS instrumentality and, consequently, teacher motivation. For example, Jane noted that ‘they always call [performance grades] a collective decision’, and that school-level ranking meetings are externally moderated. Andy said he ‘personally’ felt that EPMS rankings were ‘a fair and consistent kind of measurement’, since his school principal had ‘gone to great lengths to actually explain that it’s done before a ranking panel’, rather than depending on a line manager’s vagaries. Most participants agreed that the grading system was flawed, but not unacceptably so.

Besides participants’ descriptions of teacher accountability instruments that were functioning as designed, their descriptions of divergences between policymakers’ intentions and teachers’ responses also reflected the socioculturally embedded MMMs. In Finland, despite teachers’ general compliance with the curriculum, their autonomy and sense of competence may be such that they disregard curricular changes that clash with their priorities. For example, Antero said he was ‘happy that the principal trusts [him] so much’ that he could deprioritise certain curricular goals he viewed as secondary. When asked whether accountability instruments make it easier or harder for him to be a good teacher, he evoked a national icon:

I’m a slightly old-fashioned teacher. I like the Finnish Formula 1 driver, Kimi Räikkönen, when he shouted in his team radio, ‘Shut up, I know what I’m doing.’ So I think in here [i.e. his classroom], too, I know what I’m doing. My focus is on the pupils. And I am on the right path.

In Singapore, several participants suggested that the dominant MMM, along with the EPMS orientation toward rewards and penalties (and Singapore’s competition-oriented meritocracy more generally) had hampered a major policy platform launched in the mid-2000s: a shift toward a more holistic, less exam-oriented view of education (H. L. Lee Citation2004). In Peter’s words: ‘MOE has taken steps towards shifting the focus away from grades. […] All of that is great in terms of what it seeks to achieve. But, honestly, it hasn’t changed that competitive culture in Singapore.’ This inertia was also mentioned by Sonia, Andy, and Eleanor (see also Hogan et al. Citation2013). Similarly, Adeline observed that:

it’s still very entrenched in the exam-based mindset that you need to do well in order to get good grades, to go everywhere. And even parents buy in to that mindset. […] A lot of teachers want to buy in to the shift away from exam-based education. […] We’re quite torn between, ‘Yes, we believe in this more holistic education’—but yet we know that, in the end, the students will be judged for their exam grades.

Discussion

These findings – about the extent to which teachers’ subjective responses to accountability instruments are influenced by mental models of motivation that are embedded within wider sociocultural contexts – are relevant to analyses of teacher motivation, teacher accountability, and the relationship between ‘best practices’ and implementation contexts. To begin with teacher motivation, examining teachers’ subjective responses to accountability instruments alongside their MMMs yielded meaningful observations about dense interrelations between the two. This affirms Watt and Richardson’s (Citation2015) proposition that research on teacher beliefs and research on teacher motivation can cross-fertilise. Regarding motivation specifically, it is worth remembering that psychological theories of motivation are themselves contextually embedded constructs. Perhaps it is no coincidence that Vroom’s articulation of expectancy theory, which is frequently cited in business management (Pinder Citation1992), resonated with the dominant MMM among participants in Singapore, where economic growth has long been a central theme of discourse about both education (S. K. Lee et al. Citation2008) and national identity (Tan Citation2018).

As for teacher accountability, although the data do not allow me to distinguish the direction of influence between accountability instruments and teachers’ subjective responses (unlike, e.g. Holloway and Brass Citation2018), the analysis nonetheless shows that the effective functioning of accountability instruments in these contexts is deeply embedded in context-specific subjectivities. This complements empirical work elsewhere demonstrating that sociocultural factors can render accountability instruments ineffective (e.g. Broekman Citation2016; Mizel Citation2009; Muralidharan and Singh Citation2020; Narwana Citation2015). In short, teacher accountability policy is not solely a technical matter, but also a sociocultural one.

By demonstrating the sociocultural embeddedness of teachers’ responses to accountability policy in Finland and Singapore, this study complements other analyses of the sociocultural specificity of both micro- and macro-level educational policy and practice in these and other celebrated education systems (e.g. Heng and Song Citation2020; Holmén Citation2022; Klerides Citation2021; Simola et al. Citation2017). This growing body of evidence matters because the case against acontextual borrowing of ‘best practices’ needs to be argued across educational research traditions (Crossley and Watson Citation2003) – not least because acknowledgements of contextual influence in policy discourse can sometimes to be rhetorical strategies rather than fundamental principles (Auld and Morris Citation2016).

Conclusion

In examining the embedded interactions between teachers, accountability instruments, and sociocultural context in Finland and Singapore, I find that one way in which sociocultural context affects teachers’ interactions with accountability instruments is by influencing the mental models of motivation that shape their subjective responses to these instruments. However, two nontrivial limitations of this study are its relatively small interview sample and its temporally flat, cross-sectional nature. The latter prevents me from analysing pathways of co-evolution of accountability instruments, sociocultural context, and teachers’ individual and collective motivational responses to both. Nonetheless, this study complements other research arguing against naïve borrowing of ‘best practices’. It does so by bringing sociocultural context into the analysis of the everyday workings of the hot-button issue of teacher accountability in two reference societies, and by drawing on different strands of literature on comparative education, teacher accountability, teacher beliefs, and the psychology of motivation to ground the argument.

Contrary to claims from ‘best practice’ advocates that context ‘is secondary to getting the fundamentals right’ (Mourshed, Chijioke, and Barber Citation2010, 11), the teacher interviews in this paper suggest that context itself is fundamental. ‘Best practices’ are not context-neutral. In the words of Helena, a Finnish interview participant:

We have been getting a lot visitors in the past years, because of the PISA results. And you can see that they come in here thinking, ‘Okay, can we copy this?’ And they usually leave, I think, with, ‘No, we can’t.’

Or, as scholar-policymaker Michael Sadler put it in his 1900 essay, ‘In studying foreign systems of Education, we should not forget that the things outside the schools matter even more than the things inside the schools, and govern and interpret the things inside’ (Bereday Citation1964, 310).

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Panayiotis Antoniou, Ricardo Sabates, Charleen Chiong, Jaakko Kauko, Rob Gruijters, Geoff Hayward, and William C. Smith, as well as the editorial board of this journal, for valuable feedback on different iterations of this analysis. This study would not have been possible without the Finnish and Singaprean teachers who generously shared their time and their experiences with me.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yue-Yi Hwa

Yue-Yi Hwa is a research fellow at the Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE) Programme at the Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford.

Notes

1 Högberg and Lindgren’s (Citation2021) empirical data included Finland but not Singapore. I classify Singapore’s accountability regime as ‘thick’ based on the typology in their analysis.

2 For a study of kiasuism among Singaporean parents in navigating primary school choice, see Debs and Cheung (Citation2021).

References

- Alexander, Robin J. 2001. Culture and Pedagogy: International Comparisons in Primary Education. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Anderson-Levitt, Kathryn M. 2012. “Complicating the Concept of Culture.” Comparative Education 48 (4): 441–454. doi:10.1080/03050068.2011.634285.

- Auld, Euan, and Paul Morris. 2016. “PISA, Policy and Persuasion: Translating Complex Conditions into Education “Best Practice”.” Comparative Education 52 (2): 202–229. doi:10.1080/03050068.2016.1143278.

- Bereday, George Z. F. 1964. “‘Sir Michael Sadler’s “Study of Foreign Systems of Education”’.” Comparative Education Review 7 (3): 307–314.

- Bovens, Mark. 2007. “Analysing and Assessing Accountability: A Conceptual Framework.” European Law Journal 13 (4): 447–468. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0386.2007.00378.x.

- Broadfoot, Patricia, and Marilyn Osborn. 1993. Perceptions of Teaching: Primary School Teachers in England and France. Cassell Education. London/New York: Cassell.

- Broekman, Art. 2016. “The Effects of Accountability: A Case Study from Indonesia.” In Flip the System: Changing Education from the Ground Up, edited by Jelmer Evers, and René Kneyber, 72–96. Oxford, NY: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315678573.

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Crossley, Michael, and Keith Watson. 2003. Comparative and International Research in Education: Globalisation, Context and Difference. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Debs, Mira, and Hoi Shan Cheung. 2021. “Structure-Reinforced Privilege: Educational Inequality in the Singaporean Primary School Choice System.” Comparative Education 57 (3): 398–416. doi:10.1080/03050068.2021.1926126.

- Ehren, Melanie, and Jacqueline Baxter. 2021. “Trust, Accountability, and Capacity: Three Building Blocks of Education System Reform.” In Trust, Accountability and Capacity in Education System Reform: Global Perspectives in Comparative Education, edited by Melanie Ehren, and Jacqueline Baxter, 1–29. Abingdon: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780429344855-11.

- Feniger, Yariv, and Adam Lefstein. 2014. “How Not to Reason with PISA Data: An Ironic Investigation.” Journal of Education Policy 29 (6): 845–855. doi:10.1080/02680939.2014.892156.

- Heng, Tang T., and Lynn Song. 2020. “‘A Proposed Framework for Understanding Educational Change and Transfer: Insights from Singapore Teachers’ Perceptions of Differentiated Instruction’.” Journal of Educational Change 20 (April), doi:10.1007/s10833-020-09377-0.

- Ho, Irene T., and Kit-Tai Hau. 2014. “‘East Meets West: Teacher Motivation in the Chinese Context’.” In Teacher Motivation: Theory and Practice, edited by Paul W. Richardson, Stuart A. Karabenick, and Helen M. G. Watt, 133–149. New York: Routledge.

- Hogan, David, Melvin Chan, Ridzuan Rahim, Dennis Kwek, Khin Maung Aye, Siok Chen Loo, Yee Zher Sheng, and Wenshu Luo. 2013. “Assessment and the Logic of Instructional Practice in Secondary 3 English and Mathematics Classrooms in Singapore.” Review of Education 1 (1): 57–106. doi:10.1002/rev3.3002.

- Högberg, Björn, and Joakim Lindgren. 2021. “Outcome-Based Accountability Regimes in OECD Countries: A Global Policy Model?” Comparative Education 57 (3): 301–321. doi:10.1080/03050068.2020.1849614.

- Holloway, Jessica, and Jory Brass. 2018. “Making Accountable Teachers: The Terrors and Pleasures of Performativity.” Journal of Education Policy 33 (3): 361–382. doi:10.1080/02680939.2017.1372636.

- Holmén, Janne. 2022. “The Autonomy of Higher Education in Finland and Sweden: Global Management Trends Meet National Political Culture and Governance Models.” Comparative Education 58 (2): 147–163. doi:10.1080/03050068.2021.2018826.

- Hopmann, S. T. 2008. “No Child, No School, No State Left Behind: Schooling in the Age of Accountability.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 40 (4): 417–456. doi:10.1080/00220270801989818.

- Hufton, Neil R., Julian G. Elliott, and Leonid Illushin. 2003. “‘Teachers’ Beliefs About Student Motivation: Similarities and Differences Across Cultures’.” Comparative Education 39 (3): 367–389. doi:10.1080/0305006032000134427.

- Hwa, Yue-Yi. 2019. “Teacher Accountability Policy and Sociocultural Context: A Cross-Country Study Focusing on Finland and Singapore.” Doctoral thesis, University of Cambridge. doi:10.17863/CAM.55349.

- Hwa, Yue-Yi. 2021a. “Contrasting Approaches, Comparable Efficacy? How Macro-Level Trust Influences Teacher Accountability in Finland and Singapore.” In Trust, Accountability and Capacity in Education System Reform: Global Perspectives in Comparative Education, edited by Melanie Ehren, and Jacqueline Baxter, 222–251. Abingdon: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780429344855-11.

- Hwa, Yue-Yi. 2021b. ““What Works” Depends: Teacher Accountability Policy and Sociocultural Context in International Large-Scale Surveys.” Journal of Education Policy, 1–26. doi:10.1080/02680939.2021.2009919.

- Iyengar, Sheena S., and Mark R. Lepper. 1999. “Rethinking the Value of Choice: A Cultural Perspective on Intrinsic Motivation.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 76 (3): 349–366. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.76.3.349.

- King, Ronnel B., and Dennis M. McInerney. 2016. “Culture and Motivation: The Road Travelled and the Way Ahead.” In Handbook of Motivation at School, 2nd ed., 275–299. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315773384-21.

- Klerides, Eleftherios. 2021. “Multi-Ethnic Societies in Transition to Independence: The Uneven Development of Colonial Schooling in Cyprus and Singapore.” Comparative Education 57 (4): 496–518. doi:10.1080/03050068.2021.1973191.

- Lee, Hsien Loong. 2004. “Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s National Day Rally 2004 Speech, Sunday 22 August 2004, at the University Cultural Centre, NUS – Our Future of Opportunity and Promise.” Speech, Singapore, August 22. http://www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/speeches/view-html?filename = 2004083101.htm.

- Lee, Sing Kong, Chor Boon Goh, Birger Fredriksen, and Jee Peng Tan, eds. 2008. Toward a Better Future: Education and Training for Economic Development in Singapore Since 1965. Washington, D.C./Singapore: World Bank/NIE.

- Liew, Warren Mark. 2012. “Perform or Else: The Performative Enhancement of Teacher Professionalism.” Asia Pacific Journal of Education 32 (3): 285–303. doi:10.1080/02188791.2012.711297.

- Markus, Hazel Rose, and Shinobu Kitayama. 2010. “Cultures and Selves: A Cycle of Mutual Constitution.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 5 (4): 420–430.

- Maxwell, Joseph A. 2012. A Realist Approach for Qualitative Research. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Mizel, O. 2009. “Accountability in Arab Bedouin Schools in Israel: Accountable to Whom?” Educational Management Administration and Leadership 37 (5): 624–644. doi:10.1177/1741143209339654.

- Mourshed, Mona, Chinezi Chijioke, and Michael Barber. 2010. How the World’s Most Improved School Systems Keep Getting Better. Dubai: McKinsey & Company. http://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/dotcom/client_service/social%20sector/pdfs/how-the-worlds-most-improved-school-systems-keep-getting-better_download-version_final.ashx.

- Müller, J., and F. Hernández. 2010. “‘On the Geography of Accountability: Comparative Analysis of Teachers’ Experiences Across Seven European Countries’.” Journal of Educational Change 11 (4): 307–322. doi:10.1007/s10833-009-9126-x.

- Muralidharan, Karthik, and Abhijeet Singh. 2020. “Improving Public Sector Management at Scale? Experimental Evidence on School Governance in India.” RISE Working Paper Series 20/056. Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE). doi:10.35489/BSG-RISE-WP_2020/056.

- Narwana, K. 2015. “A Global Approach to School Education and Local Reality: A Case Study of Community Participation in Haryana, India.” Policy Futures in Education 13 (2): 219–233. doi:10.1177/1478210314568242.

- Osborn, Marilyn. 2006. “‘Changing the Context of Teachers’ Work and Professional Development: A European Perspective’.” International Journal of Educational Research 45 (4–5): 242–253. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2007.02.008.

- Partanen, Anu. 2016. The Nordic Theory of Everything: In Search of a Better Life. New York: Harper.

- Pinder, Craig C. 1992. “Valence-Instrumentality-Expectancy Theory.” In Management and Motivation: Selected Readings, edited by Victor Harold Vroom and Edward L. Deci, 2nd ed., 90–102. Penguin Business. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Romzek, Barbara S., and Melvin J. Dubnick. 1987. “Accountability in the Public Sector: Lessons from the Challenger Tragedy.” Public Administration Review 47 (3): 227–238. doi:10.2307/975901.

- Roock, Roberto Santiago de, and Darlene Machell Espeña. 2018. “Constructing Underachievement: The Discursive Life of Singapore in US Federal Education Policy.” Asia Pacific Journal of Education 38 (3): 303–318. doi:10.1080/02188791.2018.1505600.

- Ryan, Richard M., and Edward L. Deci. 2000a. “Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being.” American Psychologist 55 (1): 68–78. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68.

- Ryan, Richard M., and Edward L. Deci. 2000b. “The Darker and Brighter Sides of Human Existence: Basic Psychological Needs as a Unifying Concept.” Psychological Inquiry 11 (4): 319–338. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_03.

- Sahlberg, Pasi. 2015. Finnish Lessons 2.0: What Can the World Learn from Educational Change in Finland? 2nd ed. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Schunk, Dale H., Paul R. Pintrich, and Judith L. Meece. 2010. Motivation in Education: Theory, Research, and Applications. 3rd ed. London: Pearson.

- Sclafani, Susan, and Edmund Lim. 2008. “Rethinking Human Capital in Education: Singapore as a Model for Teacher Development”. Washington, D.C.: Aspen Institute. http://eric.ed.gov/?id = ED512422.

- Shechter, Olga G., Amanda M. Durik, Yuri Miyamoto, and Judith M. Harackiewicz. 2011. “The Role of Utility Value in Achievement Behavior: The Importance of Culture.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 37 (3): 303–317. doi:10.1177/0146167210396380.

- Simola, Hannu, Jaakko Kauko, Janne Varjo, Mira Kalalahti, and Fritjof Sahlstrom. 2017. Dynamics in Education Politics: Understanding and Explaining the Finnish Case. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Stigler, James W., and James Hiebert. 1999. The Teaching Gap: Best Ideas from the World’s Teachers for Improving Education in the Classroom. New York: The Free Press.

- Takayama, Keita, Florian Waldow, and Youl-Kwan Sung. 2013. “Finland Has It All? Examining the Media Accentuation of “Finnish Education” in Australia, Germany and South Korea.” Research in Comparative and International Education 8 (3): 307–325. doi:10.2304/rcie.2013.8.3.307.

- Tan, Kenneth Paul. 2018. Singapore: Identity, Brand, Power. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108561273.

- Verger, Antoni, and Lluís Parcerisa. 2017. “A Difficult Relationship. Accountability Policies and Teachers: International Evidence and Key Premises for Future Research.” In International Handbook of Teacher Quality and Policy, 241–254. New York: Routledge. doi:10.5281/zenodo.1256602.

- Vroom, Victor Harold. 1964. Work and Motivation. Malabar, FL: Robert E Krieger.

- Vroom, Victor Harold, and Edward L. Deci. 1992. Management and Motivation: Selected Readings. 2nd ed. Penguin Business. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Watt, Helen M. G., and Paul W. Richardson. 2015. “A Motivational Analysis of Teachers’ Beliefs.” In International Handbook of Research on Teachers’ Beliefs, edited by Helenrose Fives, and Michele Gregoire Gill, 191–211. Educational Psychology Handbook. New York: Routledge.

- You, Yun. 2017. “Comparing School Accountability in England and Its East Asian Sources of “Borrowing”.” Comparative Education 53 (2): 224–244. doi:10.1080/03050068.2017.1294652.