ABSTRACT

In recent years, researchers have highlighted the importance of students’ set of soft skills. However, although deemed important, the integration of those skills into educational systems’ policy remains ancillary in higher education. This is mainly due to the scant use of competency-based learning activities and the widely used instructional practices of back-to-basics across many higher education systems. This study set out to examine how undergraduate students perceive the extent to which competency-based learning accompanied by formative assessment feedback techniques are employed by their faculty, and the effect these methods have on their soft skills acquisition. Data were gathered from 303 Israeli undergraduate students of education, health management, and social work study tracks, and analyzed by using Partial Least Squares – Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). According to the empirical model, competency-based learning was found to be positively connected to personal, social, and methodological soft skills. Another finding showed that formative assessment feedback was highly and positively connected to competency-based learning, whereas merely low results were indicated between this factor and soft skills. These findings suggest that soft skills can be enhanced by constructivist learning activities that take place in meaningful and relevant vocational situations, accompanied by detailed feedback, based on specific assessment criteria, provided in a timely manner, constructive, and aimed at reinforcing students’ learning towards soft skill acquisition.

Introduction

Soft skills involve intrapersonal and interpersonal competencies essential for optimal functioning in general and in contemporary work environments (Succi and Canovi Citation2020). Several models have been proposed to define and classify soft skills, such as life skills (Ammani and Chitra Citation2020); twenty-first-century skills (Lepeley et al. Citation2021), key competencies for a successful life, and lifelong learning (OECD Citation2012). The term ‘soft skills’ usually refers to the emotional side of human beings (as distinguished from IQ, which is related to ‘hard skills’). Soft skills involve an optimal combination of emotion and thought and consist of the ability to identify, understand, use, and manage feelings (Khaouja et al. Citation2019). In recent years, researchers have highlighted the contribution of soft skills to areas such as physical and psychological health; interpersonal relationships; and effectiveness and success in academic studies as well as in a wide range of organizations, occupations, and levels and areas of employment (Dolev et al. Citation2021). Soft skills have been found to be supremely important for employees’ functioning and success in various fields, in a variety of professions, and in various organizations such as medical management, social work, and teaching (Pang et al. Citation2021; Schott et al. Citation2020; Yao et al. Citation2021). The work presented herein applies to the updated soft skills defined and described by the ModEs European Project (Haselberger et al. Citation2012; Succi and Canovi Citation2020), along three facets: personal, social, and methodological.

Several studies have explored the incorporation of soft skills into higher education curricula. For example, Green-Weir et al. (Citation2021) investigated the training and development of soft skill competencies among graduates of health administration programs. Their study revealed that these competencies were rarely taught in health administration settings, with discussion and structured exercises being the commonly adopted instructional strategies. The respondents reported that soft skill competencies were infrequently taught through these methods. Another study by Stalp and Hill (Citation2019) focused on the soft skill of collaborative work, demonstrating that incorporating active learning and technology in group projects could provide a conducive environment for students to learn and improve their soft skills. The importance of building meaningful relationships with peers was also highlighted in the study. Almeida and Morais (Citation2023) explored how higher education institutions responded to the challenge of integrating soft skills into their curricula. Although the number of subjects dedicated to teaching soft skills was limited, the study found that there was a growing concern to include soft skills in pedagogical and evaluation methodologies for each course. Small course sizes, legal obligations, and the challenge of finding effective evaluation methods were identified as inhibiting factors. Collectively, these studies indicated that teaching and assessing soft skills in higher education remain a challenge. This lack of a comprehensive instructional framework impedes the cultivation of students’ soft skills, which are crucial for adapting to changes. As Vista (Citation2020) noted, despite the recognized importance of soft skills, higher education systems have yet to establish competency-based learning environments that facilitate the acquisition of these skills.

This challenge lies at the core of the present investigation. This study set out to assess the extent to which college students believed their learning experiences had helped them acquire soft skills. It evaluates the extent to which competency-based learning accompanied by formative assessment feedback activities were employed by faculty in three different disciplines: education, health management, and social work. This study may provide valuable insights into the development of instructional, learning, and assessment activities that might enhance higher education students’ soft skills acquisition.

Literature review

Soft skills in higher education

The significant changes in the production system over the last few decades, mainly due to pervasive technological innovation, the incessant processes of globalization, and institutional transformations, have led to the need for highly skilled and competent professionals (Tang Citation2020). The shift from routine task-centered work activities to multiform and process-centered activities, along with the increasing number of people working in commerce and the service industry, has created a demand for workers, supervisors, and managers who possess the ability to interact positively with others and solve complex problems for which there is no set approach (Asonitou Citation2022).

Thus, education, especially higher education, has become the centerpiece of the employability skills agenda, as it is the level where advanced professional skills are developed. Nevertheless, several studies (e.g. Asonitou Citation2022) have raised serious concerns regarding the widening gap between graduates’ skills and capabilities and the requirements of the work environment in an increasingly mobile and globalized society.

As a result, there is a call to cultivate a set of non-academic attributes, such as the ‘ability’ to cooperate, communicate, and solve problems, often referred to as generic or soft skills in higher education (Chamorro-Premuzic et al. Citation2010). Soft skills, unlike academic or disciplinary knowledge, constitute a range of competencies that are independent of, albeit often developed by, formal curricula and rarely assessed explicitly. Thus, soft skills are often defined in terms of abilities and personal attributes that can be used in the wide range of working environments that graduates operate in throughout their lives (Qizi Citation2020). Consequently, there is a growing acceptance that soft skills may help students achieve not only academic but also occupational goals after graduating (Cornalli Citation2018).

Therefore, today's higher education graduates need to master not only professional skills but also various soft skills, including communication (Alshumaimeri and Alhumud Citation2021; Xie and Derakhshan Citation2021), social skills (Tseng, Yi, and Yeh Citation2019), leadership (Aldulaimi Citation2018), problem-solving, and critical thinking (Bezanilla et al. Citation2019). Hence, to achieve the aforementioned goals and improve the degree of employability of higher education graduates, educators need to develop students’ not only academic knowledge or ‘hard skills’ but also transversal or ‘soft’ skills through the revision of the curriculum and syllabuses in higher education (Tang Citation2019).

Recently, policymakers of higher education institutions and scholars have been focusing on the employment effects of graduates and the extent to which higher education programs prepare scholars adequately for their employability. For example, Tang (Citation2019) emphasized that higher education institutions are eventually expected to serve as human capital providers for the nation, making industry feedback extremely important in determining the characteristics that graduates must possess to function effectively in their workplace. Therefore, incorporating soft skills into regular learning outcomes for all scholars during their learning time in higher education institutions is a logical step towards meeting these demands.

Soft skills in health, welfare, and educational systems

By definition and their characterization, soft skills appear in a host of professions (Barrera-Osorio et al. Citation2020), but in clinical and medical fields, including medical management, welfare, and teacher education many such skills are considered core and prerequisite competencies. In the context of healthcare, skills such as critical thinking, problem-solving, effective communication, teamwork, time management, and leadership are essential and constitute part of the socio-organizational work environment of the medical team (Bos–van den Hoek et al. Citation2019). Thus, for example, communication skills are an integral part of the work of healthcare professionals on a daily basis because these professionals need to communicate with patients, relatives, colleagues, and administrative staff (Yao et al. Citation2021). Critical thinking and problem-solving are required because healthcare professionals face many critical situations in which they need to use their intellect, creativity, and logical reasoning skills (Wu and Wu Citation2020). Soft skills have been found, for example, to be correlated with medical leadership, effective functioning under pressure, positive interpersonal communication, and good teamwork (Tripathy Citation2020); improvement in doctor–patient relations, provision of empathic treatment to the patient, and an improvement in patients’ satisfaction and trust (Dimitrov and Vazova Citation2020); greater accuracy in medical diagnosis and subsequently in medical treatment, a reduction in patients’ situational anxiety, and an increase in the patient’s willingness to undergo treatment (Back et al. Citation2020).

For social workers, the acquisition of soft skills is deemed important as underscored by Shaffie et al. (Citation2019) who emphasized the formal social work education in advancing these skills through the curriculum. In their exploratory study, they described the Malaysian social workers’ experiences with soft skills acquisition as part of their professional socialization and stressed the importance of embedding soft skill competencies into the career of social workers so as to achieve both professional and social competence. This includes providing empathy and listening to patients (Millar et al. Citation2019), qualities often linked to the role of social workers. Silverman (Citation2018) introduced the competency of organizational empathy, referring to the understanding of the practice environment one occupies thereby giving the social worker greater opportunities for organizational influence, by increased collaboration and leadership abilities. In this same continuum, other empirical studies on professional social workers’ experience of empathy (e.g. Frank et al. Citation2020) provided evidence that empathy is established as a direct social perception of the other's experience and emphasized its importance in social work practice and education. The researchers argued that it is essential for curriculum designers to find ways to teach social empathy content to students, through experiential learning and intentional social connection, as it may serve as a pathway toward bridging the gap of socioeconomic difference.

In the context of teaching, several researchers explored the unique place of soft skills in teacher education programs and discussed the essence and significance of skills such as sociability, leadership, creativity, and empathy for the professional development of teachers. For example, Nguyen et al. (Citation2019) reviewed contemporary studies to identify contextual and methodological patterns of teacher leadership. Based on the analysis of 150 empirical studies, they highlighted the progress in teacher leadership from 2003 to 2017. Similarly, Schott et al. (Citation2020) systematically reviewed 93 articles and books on teacher leadership. In their study, they defined teacher leadership and presented its antecedents and outcomes. Considerable attention has been also given to empathy in recent years in educational psychology as a desirable teacher disposition and virtue (Bullough Jr Citation2019). Empathy is considered an important prerequisite for effective teaching and learning including high-quality teacher-student interactions (Aldrup et al. Citation2022); it was shown to be related to teachers’ values (e.g. bioethical values, Turgut and Yakar Citation2020); and improved students’ interpersonal and socio-emotional learning (Jaber et al. Citation2018).

Competency-based learning

Competency-based learning is an educational approach that emphasizes the acquisition of practical skills and abilities that are necessary for success in real-world contexts (Alt and Raichel Citation2018). To increase the productivity of students in the workplace, researchers discussed how higher education institutions can improve students’ set of soft skills by placing them in constructivist learning environments (Nghia Citation2019). Drawing on student-centered approaches to teaching and learning, competency-based learning is focused primarily on enhancing students’ skills and sense of agency (Hess et al. Citation2020). The learners become active when participating in inquiry practices (European Commission Citation2018). Teachers are required to situate students in authentic and relevant tasks (Care and Kim Citation2018), provide varied representations of the course content, enhance dialogue (e.g. in competency-based medical education, Sherbino et al. Citation2021), and scaffold each learner’s needs and interests (European Commission Citation2018).

Levine and Patrick (Citation2019) specified seven elements of competency-based learning: 1. Students are empowered to make decisions about their learning experiences; 2. assessment is meaningful, timely, relevant, and actionable evidence; 3. students receive support based on their learning needs; 4. students’ assessment is based on evidence of mastery; 5. students learn actively using varied pathways and pacing; 6. strategies to ensure equity for all students are embedded in the curricula; 7. rigorous, common expectations for learning are explicit, transparent, measurable, and transferable. van Der Vleuten and Schuwirth (Citation2019) underscored the importance of competency-based learning in medical education and suggested an integrative view on competency – integration of knowledge, skills, and attitudes to fulfill a multifaceted professional task. The learning outcomes of education should be specified, pertaining to the question of what the learners are able to do after completing the training program. They emphasized abilities, such as communication, collaboration, professionalism, and health advocacy, these abilities were found predictive of success in the labor market.

Students in competency-based learning environments are encouraged to self-regulate their learning processes (Zimmerman Citation1986) and to reflect on their own learning processes (Alt and Naamati-Schneider Citation2021). To do so, teaching methods should be tailored to suit different learners’ abilities, include values and ethics (e.g. in social work education, McGuire and Lay Citation2020), and should be changed from traditional teaching to a holistic approach to teaching (Alt and Raichel Citation2018). Revealing the entirety of the whole person’s qualities can be enhanced by facilitating activities in which students are required to use tools to develop consciousness and cope with difficulties and challenges. Such learning activities in which students feel safe to freely convey their arguments are central to fostering moral discussions and may elicit among the students an increased sense of self-appreciation, self-respect, and self-confidence (Alt and Raichel Citation2021).

Competency-based learning emphasizes the social and collaborative nature of the learning experience (Bhagavathula et al. Citation2021; Wijnia et al. Citation2016). Teamwork, coordination, and professionalism are deemed core skills for healthcare, nursing, social work, occupational therapy and public health students and practitioners who work with patients (Graves et al. Citation2020). These are considered also important skills for teachers’ collaborative professional development (Holmqvist and Lelinge Citation2021). The marketplace requires these competencies, urging educators to shift from centering mainly on profession-specific skills to preparing students for the realities of communicating with other professions in practice (Reynolds and Wilson Citation2018). Similarly, Radkowitsch et al. (Citation2022) have underscored the significance of collaborative competencies in medical education.

In recent years, there has been growing interest in how competence-based learning can be integrated into classroom teaching, and a number of studies have been conducted to investigate this issue. For example, Radkowitsch et al. (Citation2022) emphasized the importance of repeatedly engaging the learners with practices such as problem-based learning through simulations, and focusing the learners on practices (e.g. deliberate practice) that are particularly difficult to master. Simulation-based learning is suggested (Chernikova et al. Citation2020) as a powerful competency-based educational tool that mimics real-life situations, allowing learners to overcome the limitations of learning in real-life contexts. Simulations provide opportunities for learners to interact with authentic objects and alter some aspects of reality, facilitate learning and practice complex skills. Simulations involve critical thinking and problem-solving and require learners to take an active role in the skill development process. Simulations can involve technology aids to resemble reality more accurately, but their focus is on the reconstruction of realistic situations and genuine interactions that participants can engage in. Duration and authenticity are crucial factors in determining the effectiveness of simulation-based learning.

In other studies (Kahila et al. Citation2020), project-based learning environments are suggested to promote emotional and social skills to face negative emotions and collaborate with other students to attain a common goal. Project-based learning, wherein students get to actively explore authentic problems, might promote critical thinkers and collaborative learners. It may also encourage students’ creativity, adaptability, curiosity, sense of responsibility, and perseverance (Sistermans Citation2020).

Taken together, these studies suggest that competency-based learning can be successfully integrated into classroom teaching across a range of educational contexts. These studies also showed how these teaching and learning activities may spur competence development (Cörvers et al. Citation2016), involve students in decision-making regarding their learning progression, and develop a sense of agency through self-reflection (Alt et al. Citation2022). Indeed, competency-based learning has been identified as an effective approach to equipping students with the practical skills and abilities required for success in their chosen profession. However, Nehring et al. (Citation2019) contended that the limited implementation of competency-based learning activities can be attributed to the prevalence of summative assessment methods. Such methods, which are primarily associated with test-based accountability, have been shown to impede in-depth learning and fail to accurately measure the complex skills necessary for students to navigate challenging real-world situations. Therefore, a shift towards more comprehensive assessment methods is necessary to support the full integration of competency-based learning in education.

Formative assessment feedback

Competency-based learning frameworks had a profound effect on structuring curricula, but they also impacted the assessment method developments and their research (van Der Vleuten and Schuwirth Citation2019). Formative assessment is advised to be used to provide feedback. Formative assessment is a planned, ongoing process employed by students and teachers during the learning and teaching processes. Its aim is to use evidence of student learning to improve student learning outcomes and support them to become self-directed learners (Irons and Elkington Citation2021).

Feedback is a core component of the formative assessment process. It helps students identify their strengths and weaknesses, and teachers identify struggling students and address the problems immediately in order to enhance their achievements (Lee et al. Citation2020; McCarthy Citation2017). Feedback has been defined as ‘information provided by an agent … regarding aspects of one's performance or understanding’ (Hattie and Timperley Citation2007, 81). Providing feedback is widely acknowledged as a critical part of formative assessment affecting students’ learning outcomes (van der Kleij Citation2019).

Boud and Molloy (Citation2013b) associated feedback with the student-centered approach. Accordingly, feedback is regarded as a continuous process in which variation between the standards and the work itself is appreciated. Teachers need to provide feedback in a way that encourages and motivates the learner toward achieving their learning goals. Effective formative feedback should be considered a motivator that increases the general behavior of the learner (Ryan and Henderson Citation2018), it should be provided soon after task performance (Deeley Citation2018), and should be viewed as part of interactive and dialogic pedagogy.

Previous studies (Ajjawi and Boud Citation2016; van der Kleij Citation2019) listed several barriers to effective feedback. For example, the rising number of students pursuing higher education has led to a corresponding decrease in formative assessment feedback (Boud and Molloy Citation2013a; Henderson et al. Citation2019). Another barrier deals with students’ nonconstructive feedback experiences, raising a call for less generic and more individualized, and constructive feedback, containing information that could be utilized to improve their future work (Henderson et al. Citation2019). Yet, it bears mentioning that despite its well-documented influence on students’ achievement (McCallum and Milner Citation2021) higher education institutions are being criticized for inadequacies in the feedback they provide to students (Wu and Jessop Citation2018).

Recent research (Wang et al. Citation2021) suggested that feedback plays a significant role in facilitating learning across a wide range of instructional settings. Feedback not only allows learners to identify gaps in their knowledge and skills but also supports them in the acquisition of new knowledge and skills and in regulating their learning processes (Chou and Zou Citation2020). In competency-based learning, feedback is particularly essential as it is used to develop competencies, and learners perceive it as an integral part of instruction that validates their understanding and progress. By providing iterative formative assessments and feedback, learners are encouraged to practice skills repeatedly, reinforce their learning, and extend their knowledge and competencies (Besser and Newby Citation2020; Wang et al. Citation2021).

Competency-based medical education relies on formative assessments that aim to support learners in achieving the next level of mastery, rather than being a final evaluation (Lee and Chiu Citation2022). While written exams are commonly used to assess medical learners, assessments of skill performance, such as direct observation or patient registries, provide more compelling evidence of learning outcomes. Once areas for improvement are identified, effective feedback is essential to support learners’ professional development. To be effective, feedback should be routine, timely, specific, and nonthreatening, while also encouraging self-assessment (Holbrook and Kasales Citation2020). The ‘ask-tell-ask’ feedback approach aligns with this framework, whereby the observer first asks for the learner's self-assessment, provides their own assessment, and then asks the learner for questions and an action plan to address the identified issues. Effective assessment and feedback in competency-based medical education support learners in their professional development and provide evidence of their impact on the health outcomes of patients and communities (Lee and Chiu Citation2022).

This study

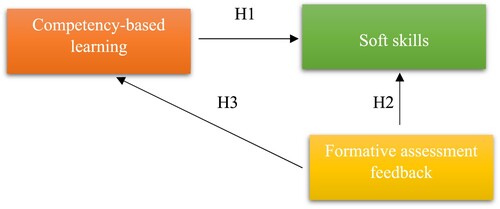

Drawing on the above-surveyed studies, this study sought to measure the extent to which college students believed their learning experiences throughout their studies had helped them acquire soft skills. Particularly, it aimed to assess how students perceive the extent to which competency-based learning environments and formative assessment feedback are employed by their faculty, and the bearing these methods have on their perceived personal, social, and methodological soft skills. The main research question was: to what extent would competency-based learning and formative assessment feedback impact students’ perceived acquired soft skills? It was hypothesized that competency-based learning environments would enhance the participants’ perceived soft skills (H1). It was also postulated that formative assessment feedback would enhance the participants’ perceived soft skills (H2). Based on the well-established link between formative assessment and competency-based learning (Irons and Elkington Citation2021; van Der Vleuten and Schuwirth Citation2019), we also assumed that the latter will be informed by formative assessment methods (H3). Background variables such as age, gender, and GPA will be addressed to examine how they may intersect with the examined constructs. Model 1 () is the theoretical structure of the proposed framework.

Method

Participants

Data for the analysis were gathered from 303 Israeli undergraduate students of education 35%; health management 47.5%; and social work 17.5% study tracks. The students’ mean age was M = 26.54 (SD = 7.51), 76% were females. Concerning ethnicity, 61% were Jews, and 39% were Arabs (Muslims). The distribution of years of study was as follows: 35.7% first-year students; 32.3% second-year students; 23.8% third-year students; and 8.2% fourth-year students. Thirty-two percent reported working in health/teaching/social work professions (Profession). GPA was checked on a five-point scale: 1 = 50-60; 2 = 61-70; 3 = 71-80; 4 = 81-90; 5 = 91-100. The most frequent category was 4 (reported by 53% of the participants), followed by 5 (22%).

Measurements

Soft Skills. This 20-item scale (Haselberger et al. Citation2012; Succi Citation2019; Succi and Canovi Citation2020) was originally designed to assess students’ perceptions regarding the importance of soft skills along three factors: (1) personal skills (PS, e.g. ‘Being Committed to Work – make a commitment to the organization and understand its specific characteristics’); (2) social skills (SS, e.g. ‘Communication Skills – transmit ideas, information and opinions clearly and convincingly, both verbally and in writing, while listening’); and (3) methodological skills (MS, e.g. ‘Analysis Skills – draw conclusions and forecasts for the future by acquiring relevant information from different sources’). In this study, the participants were asked to report the extent to which their academic institution enhanced their soft skills on a 6-point Likert-style ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to assess the construct validity of the scale, using confirmatory factor analysis. Data used for the SEM were analyzed with the maximum likelihood method. Three fit indices were computed in order to evaluate the model fit: χ2(df), (p-value should be higher than .05), the goodness-of-fit index (CFI) should be higher than 0.9, and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). RMSEA less than .05 corresponds to a ‘good’ fit and an RMSEA less than .08 corresponds to an ‘acceptable’ fit (Bentler Citation2006). Amos 22 software was used for SEM analysis. The goodness of fit of the data to the model yielded to sufficient fit results (χ2 = 446.08, df = 161, p = .000; CFI = .932; RMSEA = .07). The personal skills factor included seven items (α = .89); the social skills comprised of six items (α = .88); and the methodological skills factor included seven items (α = .92). Validity and reliability of the instrument were confirmed.

Competency-based Learning. Based on the framework of Wesselink et al. (Citation2007, Citation2010) and Sturing et al. (Citation2011), this 13-item scale was designed by Wijnia et al. (Citation2016) to capture the frequency of competency-based learning activities used by teachers during courses, as perceived by the students. The participants were asked to indicate to what extent the educational program they were enrolled in included principles such as ‘The guidance is adjusted to the learning needs of the student team’ or ‘The study program is structured in such a way that the students increasingly self-direct their learning’. A 6-point Likert-style format was used ranging from 1 = never to 6 = always (α = .93).

Formative Assessment Feedback. This eight-item scale was designed by McCarthy (Citation2017) to evaluate the frequency of formative assessment feedback principles used by teachers during courses, as perceived by the students. The participants were asked to indicate to what extent the educational program they were enrolled in included principles such as ‘feedback was provided frequently and within the timeframe of each task’ or ‘feedback was focused on the student’s academic performance’. A 6-point Likert-style format was used ranging from 1 = never to 6 = always (α = .92). Descriptive statistics of the research factors are provided in .

Table 1. Factors and descriptive statistics.

Procedure

Participants were recruited by research assistants from three large departments: Education, social work, and health management. The purpose of the study was explained as examining students’ learning experiences. Participants’ consent to fill out the questionnaire was attained. The anonymity of participants was reassured. The participants were assured that no specific identifying information about their academic affiliation would be processed. The research was approved by the college’s Ethics Committee.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using Partial Least Squares – Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM; Hair Jr et al. Citation2017), a method advised to be employed if the main objective of applying structural equation modeling is the prediction of target variables. SmartPLS 3 software was used.

Findings

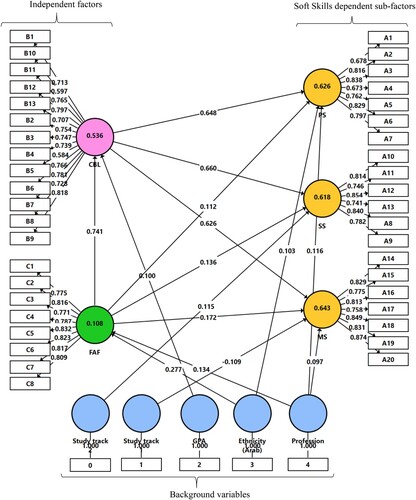

Model 2 () was constructed to check the research hypotheses. A preliminary analysis checked the effects of all the background variables on the model constructs. Based on these results, the following variables were entered into the model to enable controlling their effects on the main factors: GPA, profession (in-service employee); and ethnicity (Arab students). In addition, two dummy variables were entered into the model: study track 1 (1 = education; 2 = health management and social work); study track 2 (1 = social work; 2 = health management and education).

Figure 2. Model 2. Analysis results of research model by SmartPLS. Note: (1) personal skills (PS); social skills (SS); methodological skills (MS); competency-based learning (CBL); formative assessment feedback (FAF); profession (in-service employee); study track 1 (1 = education; 2 = health management and social work); study track 2 (1 = social work; 2 = health management and education); ethnicity (Arab students).

Model 2 includes these background variables and the following main constructs: soft skills with three sub-factors: personal skills (PS); social skills (SS); methodological skills (MS). Competency-based learning (CBL) and formative assessment feedback (FAF) are shown on the left as independent variables.

displays the bootstrap routine analysis results for Model 2 (). According to the results, competency-based learning was found highly contributive to the soft skills sub-factors, H1 was confirmed. Formative assessment feedback was found positively related to competency-based learning, with a high coefficient result, whereas merely low results were obtained between this factor and the soft skills sub-factors, hence H2 and H3 were approved. The indirect effects check showed significant results, indicating positive links between formative assessment feedback to the sub-factors of soft skills via competency-based learning. In relation to background variables, low coefficient results were detected between these variables and the main factors. The highest, yet low, result was shown between ethnicity and formative assessment feedback, accordingly, Arab students reported receiving formative feedback in their courses more than their Jewish counterparts.

Table 2. Significance analysis of the direct and indirect effects for Model 1.

Model evaluation

Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values were checked for collinearity. The results of all sets of predictor constructs in the structural model showed that the values of all combinations of endogenous and exogenous constructs are below the threshold of 5 (Hair Jr et al. Citation2017) ranging from 1.03–2.20. The coefficient of determination (R2) values for the endogenous factors ranged from 0.11–0.64 these values can be considered low to moderate (Hair Jr et al. Citation2017). The change in the R2 value (f2 effect size) showed that all the background variables had very low effect sizes, lower than 0.1 on the endogenous latent variables. The highest effect size results were found between competency-based learning and: social skills (f2 = 0.54), personal skills (f2 = 0.53), methodological skills (f2 = 0.52). Finally, the blindfolding procedure was used to assess the predictive relevance (Q2) of the path model. Values larger than 0 suggest that the model has predictive relevance for a certain endogenous construct (Hair Jr et al. Citation2017). The Q2 values ranged from .07 to .42. All three hypotheses were confirmed.

Discussion

This study explored the extent to which college students believed their learning experiences throughout their studies had helped them acquire soft skills. More specifically, it sought to evaluate how those students perceived the extent to which competency-based learning environments and formative assessment feedback were used by their faculty, and their potential effect on their perceived personal, social, and methodological soft skills.

First hypothesis

In the first hypothesis it was postulated that competency-based learning environments would enhance the participants’ perceived soft skills. According to the empirical model, this hypothesis was corroborated – competency-based learning was found positively connected to the soft skills sub-factors including personal, social, and methodological skills. These findings suggest that soft skills can be enhanced by constructivist learning activities that take place in meaningful and relevant vocational situations and deal with complex vocational core problems. Vocational training is deemed important in preparing students for the contemporary labor market (Chatigny Citation2022). These learning activities are adjusted to the student’s needs and encourage key lifelong learning skills of self-directed learning, required of healthcare providers (Robinson and Persky Citation2020), and teachers (Carpenter and Willet Citation2021). Silverman (Citation2018) echoed this argument in higher education contexts and strengthened the need for such instructional endeavors in the framework of social work education. First-year field students lack appropriate organizational knowledge, he argued, many of these new practitioners enter the ‘fog of practice’ and are in need of a strong mentor who can guide and show them how to thrive in the real world. To bridge the academe–practice knowledge gap, he suggested equipping the practitioner with collaboration and leadership skills by introducing competency of organizational empathy – understanding of the practice environment one occupies – into the curriculum.

According to Le et al. (Citation2022), project-based learning methodologies are recommended to equip students with the competencies required in the contemporary era. The authors contended that vocational education programs should impart skills that align with the demands of the twenty-first-century workforce. Owing to the impact of technological advancements on various facets of society, including education, the nature of work has become increasingly intricate. Consequently, graduates of vocational education programs must possess proficiencies in learning, literacy, and life skills.

Second hypothesis

The second assumption postulated that formative assessment feedback would enhance participants’ perceived soft skills. Our findings indicated a low, yet significant, direct link between this factor and the sub-factors of soft skills. Additionally, an indirect effect of formative assessment feedback on the measured soft skill perceptions through competency-based learning was shown. These results confirmed the second hypothesis and emphasized the crucial role of feedback in enhancing the way students perceive the extent to which they acquired soft skills during their studies.

These findings are consistent with past research (e.g. Wang et al. Citation2021), which underscored the vital role of feedback in identifying gaps in learners’ knowledge and skills and supporting the acquisition of new skills. Feedback is especially significant in fostering competencies, as learners perceive it as an indispensable component of instruction that validates their understanding and progress (Chou and Zou Citation2020). By providing iterative formative assessments and feedback, learners are encouraged to engage in repeated skill practice, consolidate their learning, and expand their knowledge and competencies (Besser and Newby Citation2020; Wang et al. Citation2021).

However, previous studies suggested that feedback should be regular, timely, specific, and nonthreatening while promoting self-assessment to be effective (Holbrook and Kasales Citation2020). The ‘ask-tell-ask’ feedback approach aligns with this framework, in which the observer initially solicits the learner's self-assessment, provides their assessment, and then inquires about the learner's questions and action plan to address identified issues. Effective feedback in competency-based medical education contributes to learners’ professional development and provides evidence of their impact on the health outcomes of patients and communities, making it an essential component (Lee and Chiu Citation2022).

Third hypothesis

Lastly, it was hypothesized that competency-based learning would be informed by formative assessment methods. Our findings confirmed this assumption by showing a direct link between these variables. This finding can be corroborated by previous studies suggesting a triangular framework for curriculum development (Dhanapala Citation2021). This framework is comprised of a series of learning activities and outcomes pertaining to the subject, purposed at improving student learning and outcomes by facilitating high-quality teaching, and assessment of learning outcomes. Hence a viable curriculum framework should relate to the interrelationships of teaching, learning, and assessment. Yan and Boud (Citation2021) proposed viewing assessment as learning in higher education and in school education. They highlighted the requirements of assessment tasks in providing students with learning activities and promoting their active role in them. This link between assessment and learning is distinguished from other assessment concepts, such as assessment-for-learning, as it is centered on the assessment tasks themselves as learning activities.

Background variables

In relation to the background variables measured in the empirical model, Arab students reported receiving formative feedback in their courses more than their Jewish counterparts. This can be explained by previous studies (e.g. Alt and Raichel Citation2021) which addressed the use of feedback in culturally diverse higher education learning environments. It is worth noting that the body of literature in this context is undermined by inconsistent findings and is notably scant in relation to Arab students in Israel. Nonetheless, the few studies that have dealt with this aspect in organizations focused on the perspective of feedback seeking, suggesting that feedback-seeking behavior by individuals might be shaped by their culture. In the context of higher education, Ryan and Henderson (Citation2018) drew attention to the unique aspect of students being able to receive feedback from an authoritative individual, such as a lecturer or tutor. In this form of social interaction, factors associated with power, discourse, identity, and emotion may arise. In a hierarchical organization such as a university, individuals may feel personally slighted when a more knowledgeable person points out insufficiencies in their work. Yet with only limited studies into feedback sought provided in culturally diverse learning environments, it seems difficult to rationalize our findings related to the low bearings of culture on assessment feedback.

Limitations and recommendations for future research

In this study, behaviors were not collected in actual environments, instead, student perceptions were measured using a self-reporting survey. Future studies may further benefit from an alternative measure that focuses more specifically on observed behaviors. For this purpose, approaches such as participatory design research might have the potential to substantively elaborate on the current study's findings.

This study's generalizability is limited by its geographic and disciplinary focus. Specifically, the research was conducted solely within one country and was restricted to students enrolled in education, health management, and social work programs. Therefore, caution should be exercised when extrapolating the findings to other regions or academic tracks. To validate the results fully and corroborate the factor structure and inter-factor relationships, a cross-cultural examination is necessary. Such a study would provide insight into whether the factors identified in this research are unique to the sample population or are a more universal characteristic of students in these academic fields. As such, further cross-cultural research is needed to enhance the study's external validity and provide more comprehensive insights into the topic under investigation.

Conclusions and implications

The present study provides some initial evidence indicating that competency-based learning and formative assessment feedback might influence the way higher education students believe they have acquired soft skills during their learning at college. To obtain these learning outcomes, this study proposes to focus instructional efforts on authentic and varied vocational situations and problems. It is advisable to detect and define core competencies for the study program and integrate knowledge, skills, and attitudes in the learning and assessment processes. Among these competencies required for work performance, instructional efforts should focus on acquiring citizenship competencies, lifelong learning, and communication skills. Students should be given opportunities to actively engage in self-regulated learning processes and should be involved in reflective processes. Instructional endeavors should be individualized and adjusted to students’ learning so as to improve students’ performances (Zhang et al. Citation2020). Innovative flexible learning environments (Valtonen et al. Citation2021) with active teaching and learning strategies (such as gaming, Alt Citation2023; McEnroe-Petitte and Farris Citation2020) should be fostered. Students should receive frequent assessment throughout the course, aimed at scaffolding their learning processes towards achieving the predefined learning outcomes (i.e. soft skills). Feedback should be detailed, addressing specific assessment criteria, constructive, provided in a timely manner, and as an incentive to the student to reinforce their learning towards soft skill acquisition.

Following the implementation of competency-based learning in many European countries to narrow the divide between the labor market and education (Wijnia et al. Citation2016), this study adds to previous studies by underscoring the importance of integrating these learning and assessment methods into healthcare, social work, and education studies. Training medical and managerial staff and developing soft skills such as self-awareness, self-management, tolerance of stressful situations, empathy, and interpersonal communication plays a decisive role in the success of medical and medical-management staff (Mangan et al. Citation2022).

This study points to an exciting new venue for further research, the findings of which are likely to have a bearing also on features of teacher education. Skills such as leadership, creativity, and empathy are deemed essential for the professional development of teachers (Bullough Jr Citation2019; Nguyen et al. Citation2019; Schott et al. Citation2020). Empathy is important to raise the quality of teacher-student interactions (Aldrup et al. Citation2022) and is linked to teachers’ set of values. Therefore, using methods that integrate knowledge, skills, and attitudes during instruction is of importance. Nonetheless, this study offers generic characteristics of the learning approach that might spur students’ soft skills. More specifically designed instructional methods that might nurture these competencies should be offered for future investigations and their ability to increase these lifelong learning outcomes should be assessed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ajjawi, R., and D. Boud. 2016. “Researching Feedback Dialogue: An Interactional Analysis Approach.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 42: 252–265. doi:10.1080/02602938.2015.1102863.

- Aldrup, K., B. Carstensen, and U. Klusmann. 2022. “Is Empathy the Key to Effective Teaching? A Systematic Review of Its Association with Teacher-Student Interactions and Student Outcomes.” Educational Psychology Review, 1177–1216. doi:10.1007/s10648-021-09649-y.

- Aldulaimi, S. H. 2018. “Leadership Soft Skills in Higher Education Institutions.” Social Science Learning Education Journal 03 (7): 01–08. doi:10.15520/sslej.v3i7.2219.

- Almeida, F., and J. Morais. 2023. “Strategies for Developing Soft Skills Among Higher Engineering Courses.” Journal of Education 203 (1): 103–112. doi:10.1177/00220574211016417.

- Alshumaimeri, Y. A., and A. M. Alhumud. 2021. “EFL Students’ Perceptions of the Effectiveness of Virtual Classrooms in Enhancing Communication Skills.” English Language Teaching 14 (11): 80–96. doi:10.5539/elt.v14n11p80.

- Alt, D. 2023. “Assessing the benefits of gamification in mathematics for student gameful experience and gaming motivation.” Computers and Education. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2023.104806.

- Alt, D., and N. Raichel. 2018. Lifelong citizenship: Lifelong learning as a lever for moral and democratic values. Brill and Sense Publishers.

- Alt, D., and N. Raichel. 2021. Equity and formative assessment in higher education: Advancing culturally responsive assessment. Springer.

- Alt, D., N. Raichel, and L. Schneider. 2022. “Higher education students’ reflective journal writing and lifelong learning skills: Insights from an exploratory sequential study.” Frontiers in Psychology. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.707168.

- Alt, D., and L. Schneider. 2021. “Health management students’ self-regulation and digital concept mapping in online learning environments.” BMC Medical Education. doi:10.1186/s12909-021-02542-w.

- Ammani, S., and V. B. Chitra. 2020. “Blended Learning of Soft Skills Through Life Skills in an Organization.” IUP Journal of Soft Skills 14 (4): 7–11.

- Asonitou, S. 2022. “Impediments and Pressures to Incorporate Soft Skills in Higher Education Accounting Studies.” Accounting Education 31 (3): 243–272. doi:10.1080/09639284.2021.1960871.

- Back, A., J. A. Tulsky, and R. M. Arnold. 2020. “Communication Skills in the age of COVID-19.” Annals of Internal Medicine 172 (11): 759–760. doi:10.7326/M20-1376.

- Barrera-Osorio, F., A. D. Kugler, and M. I. Silliman. 2020. Hard and Soft Skills in Vocational Training: Experimental Evidence from Colombia (No. w27548). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Bentler, P. M. 2006. EQS 6 Structural Equations Program Manual. Multivariate Software, Inc.

- Besser, E. D., and T. J. Newby. 2020. “Feedback in a Digital Badge Learning Experience: Considering the Instructor’s Perspective.” TechTrends 64: 484–497. doi:10.1007/s11528-020-00485-5.

- Bezanilla, M. J., D. Fernández-Nogueira, M. Poblete, and H. Galindo-Domínguez. 2019. “Methodologies for Teaching-Learning Critical Thinking in Higher Education: The Teacher’s View.” Thinking Skills and Creativity 33), doi:10.1016/j.tsc.2019.100584.

- Bhagavathula, S., K. Brundiers, M. Stauffacher, and B. Kay. 2021. “Fostering Collaboration in City Governments’ Sustainability, Emergency Management and Resilience Work Through Competency-Based Capacity Building.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 63), doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102408.

- Bos–van den Hoek, D. W., L. N. Visser, R. F. Brown, E. M. Smets, and I. Henselmans. 2019. “Communication Skills Training for Healthcare Professionals in Oncology Over the Past Decade: A Systematic Review of Reviews.” Current Opinion in Supportive & Palliative Care 13 (1): 33–45. doi:10.1097/SPC.0000000000000409.

- Boud, D., and E. Molloy. 2013a. “Rethinking Models of Feedback for Learning: The Challenge of Design.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 38: 698–712. doi:10.1080/02602938.2012.691462.

- Boud, D., and E. Molloy. 2013b. “What is the Problem with Feedback?” In Feedback in Higher and Professional Education, edited by D. Boud, and E. Molloy, 1–10. Routledge.

- Bullough Jr, R. V. 2019. “Empathy, Teaching Dispositions, Social Justice and Teacher Education.” Teachers and Teaching 25 (5): 507–522. doi:10.1080/13540602.2019.1602518.

- Care, E., and H. Kim. 2018. “Assessment of Twenty-First Century Skills: The Issue of Authenticity.” In Assessment and Teaching of 21st Century Skills: Research and Applications, edited by E. Care, M. Wilson, and P. Griffin, 21–40. Springer.

- Carpenter, J. P., and K. B. S. Willet. 2021. “The Teachers’ Lounge and the Debate Hall: Anonymous Self-Directed Learning in Two Teaching-Related Subreddits.” Teaching and Teacher Education 104), doi:10.1016/j.tate.2021.103371.

- Chamorro-Premuzic, T., A. Arteche, A. J. Bremner, C. Greven, and A. Furnham. 2010. “Soft Skills in Higher Education: Importance and Improvement Ratings as a Function of Individual Differences and Academic Performance.” Educational Psychology 30 (2): 221–241. doi:10.1080/01443410903560278.

- Chatigny, C. 2022. “Occupational Health and Safety in Initial Vocational Training: Reflection on the Issues of Prescription and Integration in Teaching and Learning Activities.” Safety Science 147), doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2021.105580.

- Chernikova, O., N. Heitzmann, M. Stadler, D. Holzberger, T. Seidel, and F. Fischer. 2020. “Simulation-based Learning in Higher Education: A Meta-Analysis.” Review of Educational Research 90 (4): 499–541. doi:10.3102/0034654320933544.

- Chou, C. Y., and N. B. Zou. 2020. “An Analysis of Internal and External Feedback in Self-Regulated Learning Activities Mediated by Self-Regulated Learning Tools and Open Learner Models.” International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 17 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1186/s41239-019-0174-x.

- Cornalli, F. 2018. Training and Developing Soft Skills in Higher Education. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Higher Education Advances (HEAd’18) (pp. 961-967). Editorial Universitat Politècnica de València. doi:10.4995/HEAd18.2018.8127.

- Cörvers, R., A. Wiek, J. de Kraker, D. J. Lang, and P. Martens. 2016. “Problem-based and Project-Based Learning for Sustainable Development.” In Sustainability Science, 349–358. Springer.

- Deeley, S. J. 2018. “Using Technology to Facilitate Effective Assessment for Learning and Feedback in Higher Education.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 43: 439–448. doi:10.1080/02602938.2017.1356906.

- Dhanapala, R. M. 2021. “Triangular Framework for Curriculum Development in the Education Sector.” OALib 08 (6): 1–10. doi:10.4236/oalib.1107490.

- Dimitrov, Y., and T. Vazova. 2020. “Developing Capabilities from the Scope of Emotional Intelligence as Part of the Soft Skills Needed in the Long-Term Care Sector: Presentation of Pilot Study and Training Methodology.” Journal of Primary Care & Community Health 11), doi:10.1177/2150132720906275.

- Dolev, N., L. Naamati-Schneider, and A. Meirovich. 2021. “Making soft skills a part of the curriculum of healthcare studies.” In Medical education for the 21st century. IntechOpen, edited by M. S. Firstenberg and S. P. Stawicki. doi:10.5772/intechopen.98671.

- European Commission. 2018. Commission staff working document accompanying the document proposal for a council recommendation on key competences for lifelong learning. https://ec.europa.eu/.

- Frank, J. M., L. B. Granruth, H. Girvin, and A. VanBuskirk. 2020. “Bridging the gap Together: Utilizing Experiential Pedagogy to Teach Poverty and Empathy.” Journal of Social Work Education 56 (4): 779–792. doi:10.1080/10437797.2019.1661904.

- Graves, J., R. Roche, V. Washington, and J. Sonnega. 2020. “Assessing and Improving Students’ Collaborative Skills Using a Mental Health Simulation: A Pilot Study.” Journal of Interprofessional Care, doi:10.1080/13561820.2020.1763277.

- Green-Weir, R. R., D. Anderson, and R. Carpenter. 2021. “Impact of Instructional Practices on Soft-Skill Competencies.” Research in Higher Education Journal 40), https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1296471.

- Hair Jr, J. F., G. T. M. Hult, C. M. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2017. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). 2nd ed. Sage.

- Haselberger, D., P. Oberheumer, E. Perez, M. Cinque, and D. Capasso. 2012. Mediating Soft Skills at Higher Education Institutions (MODES). Guidelines for the Design of Learning 100 Situations Supporting Soft Skills Achievement. European Commission. https://gea-college.si/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/MODES_handbook_en.pdf.

- Hattie, J., and H. Timperley. 2007. “The Power of Feedback.” Review of Educational Research 77: 81–112. doi:10.3102/003465430298487.

- Henderson, M., R. Ajjawi, D. Boud, and E. Molloy (eds.) 2019. The Impact of Feedback in Higher Education: Improving Assessment Outcomes for Learners. Springer Nature.

- Hess, K., R. Colby, and D. Joseph. 2020. Deeper Competency-Based Learning: Making Equitable, Student-Centered, Sustainable Shifts. Corwin.

- Holbrook, A. I., and C. Kasales. 2020. “Advancing Competency-Based Medical Education Through Assessment and Feedback in Breast Imaging.” Academic Radiology 27 (3): 442–446. doi:10.1016/j.acra.2019.04.017.

- Holmqvist, M., and B. Lelinge. 2021. “Teachers’ Collaborative Professional Development for Inclusive Education.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 36 (5): 819–833. doi:10.1080/08856257.2020.1842974.

- Irons, A., and S. Elkington. 2021. Enhancing Learning Through Formative Assessment and Feedback. Routledge.

- Jaber, L. Z., S. Southerland, and F. Dake. 2018. “Cultivating Epistemic Empathy in Preservice Teacher Education.” Teaching and Teacher Education 72: 13–23. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2018.02.009.

- Kahila, J., T. Valtonen, M. Tedre, K. Mäkitalo, and O. Saarikoski. 2020. “Children’s Experiences on Learning the 21st-Century Skills with Digital Games.” Games and Culture 15 (6): 685–706. doi:10.1177/1555412019845592.

- Khaouja, I., G. Mezzour, K. M. Carley, and I. Kassou. 2019. “Building a Soft Skill Taxonomy from job Openings.” Social Network Analysis and Mining 9 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1007/s13278-019-0583-9.

- Le, S. K., S. N. Hlaing, and K. Z. Ya. 2022. “21st-century Competences and Learning That Technical and Vocational Training.” Journal of Engineering Researcher and Lecturer 1 (1): 1–6. doi:10.58712/jerel.v1i1.4.

- Lee, G. B., and A. M. Chiu. 2022. “Assessment and Feedback Methods in Competency-Based Medical Education.” Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology 128 (3): 256–262. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2021.12.010.

- Lee, H., H. Q. Chung, Y. Zhang, J. Abedi, and M. Warschauer. 2020. “The Effectiveness and Features of Formative Assessment in US K-12 Education: A Systematic Review.” Applied Measurement in Education 33 (2): 124–140. doi:10.1080/08957347.2020.1732383.

- Lepeley, M. T., N. J. Beutell, N. Abarca, and N. Majluf (eds.) 2021. Soft Skills for Human Centered Management and Global Sustainability. Routledge.

- Levine, E., and S. Patrick. 2019. What is Competency-Based Education? An Updated Definition. Aurora Institute. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED604019.pdf.

- Mangan, J., J. Rae, J. Anderson, and D. Jones. 2022. “Undergraduate Paramedic Students and Interpersonal Communication Development: A Scoping Review.” Advances in Health Sciences Education, doi:10.1007/s10459-022-10134-6.

- McCallum, S., and M. M. Milner. 2021. “The Effectiveness of Formative Assessment: Student Views and Staff Reflections.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 46 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1080/02602938.2020.1754761.

- McCarthy, J. 2017. “Enhancing Feedback in Higher Education: Students’ Attitudes Towards Online and in-Class Formative Assessment Feedback Models.” Active Learning in Higher Education 18 (2): 127–141. doi:10.1177/1469787417707615.

- McEnroe-Petitte, D., and C. Farris. 2020. “Using Gaming as an Active Teaching Strategy in Nursing Education.” Teaching and Learning in Nursing 15 (1): 61–65. doi:10.1016/j.teln.2019.09.002.

- McGuire, L. E., and K. A. Lay. 2020. “Reflective Pedagogy for Social Work Education: Integrating Classroom and Field for Competency-Based Education.” Journal of Social Work Education 56 (3): 519–532. doi:10.1080/10437797.2019.1661898.

- Millar, A., J. Devaney, and M. Butler. 2019. “Emotional Intelligence: Challenging the Perceptions and Efficacy of ‘Soft Skills’ in Policing Incidents of Domestic Abuse Involving Children.” Journal of Family Violence 34 (6): 577–588. doi:10.1007/s10896-018-0018-9.

- Nehring, J. H., M. Charner-Laird, and S. A. Szczesiul. 2019. “Redefining Excellence: Teaching in Transition, from Test Performance to 21st Century Skills.” NASSP Bulletin 103 (1): 5–31. doi:10.1177/0192636519830772.

- Nghia, T. L. H. 2019. Building Soft Skills for Employability: Challenges and Practices in Vietnam. Routledge.

- Nguyen, D., A. Harris, and D. Ng. 2019. “A Review of the Empirical Research on Teacher Leadership (2003–2017): Evidence, Patterns and Implications.” Journal of Educational Administration 58: 60–80. doi:10.1108/JEA-02-2018-0023.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]. 2012. Better Skills, Better Jobs, Better Lives: A Strategic Approach to Skills Policies. OECD.

- Pang, Y., Q. Wu, J. Bi, and J. Wang. 2021. “Effectiveness of Hierarchical, Diversified Soft Skills Training in Clinical Nursing Training.” International Journal of Clinical Practice 75 (12), doi:10.1111/ijcp.14935.

- Qizi, K. N. U. 2020. “Soft Skills Development in Higher Education.” Universal Journal of Educational Research 8 (5): 1916–1925. doi:10.13189/ujer.2020.080528.

- Radkowitsch, A., M. Sailer, M. R. Fischer, R. Schmidmaier, and F. Fischer. 2022. “Diagnosing Collaboratively: A Theoretical Model and a Simulation-Based Learning Environment.” In Learning to Diagnose with Simulations. Examples from Teacher Education and Medical Education, edited by F. Fischer, and A. Opitz, 123–142. Springer.

- Reynolds, E., and G. M. Wilson. 2018. “The Power of Interprofessional Education to Enhance Competency-Based Learning in Health Informatics and Population Health Students.” The Journal of Health Administration Education 35 (3): 377.

- Robinson, J. D., and A. M. Persky. 2020. “Developing Self-Directed Learners.” American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 84 (3), doi:10.5688/ajpe847512.

- Ryan, T., and M. Henderson. 2018. “Feeling Feedback: Students’ Emotional Responses to Educator Feedback.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 43: 880–892. doi:10.1080/02602938.2017.1416456.

- Schott, C., H. van Roekel, and L. G. Tummers. 2020. “Teacher Leadership: A Systematic Review, Methodological Quality Assessment and Conceptual Framework.” Educational Research Review 31: 100352. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100352.

- Shafie, H., F. A. Majid, and I. S. Ismail. 2019. “Technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) in teaching 21st century skills in the 21st century classroom.” Asian Journal of University Education 15 (3): 24–33.

- Sherbino, J., G. Regehr, K. Dore, and S. Ginsburg. 2021. “Tensions in Describing Competency-Based Medical Education: A Study of Canadian Key Opinion Leaders.” Advances in Health Sciences Education 26 (4): 1277–1289. doi:10.1007/s10459-021-10049-8.

- Silverman, E. 2018. “Moving Beyond Collaboration: A Model for Enhancing Social Work’s Organizational Empathy.” Social Work 63 (4): 297–304. doi:10.1093/sw/swy034.

- Sistermans, I. J. 2020. “Integrating Competency-Based Education with a Case-Based or Problem-Based Learning Approach in Online Health Sciences.” Asia Pacific Education Review 21 (4): 683–696. doi:10.1007/s12564-020-09658-6.

- Stalp, M. C., and S. Hill. 2019. “The Expectations of Adulting: Developing Soft Skills Through Active Learning Classrooms.” Journal of Learning Spaces 8 (2).

- Sturing, L., H. J. A. Biemans, M. Mulder, and E. De Bruijn. 2011. “The Nature of Study Programmes in Vocational Education: Evaluation of the Model for Comprehensive Competence-Based Vocational Education in the Netherlands.” Vocations and Learning 4: 191–210. doi:10.1007/s12186-011-9059-4.

- Succi, C. 2019. “Are you Ready to Find a job Ranking of a List of Soft Skills to Enhance Graduates' Employability.” International Journal of Human Resources Development and Management 19 (3): 281–297. doi:10.1504/IJHRDM.2019.100638.

- Succi, C., and M. Canovi. 2020. “Soft skills to enhance graduate employability: comparing students and employers’ perceptions.” Studies in Higher Education 45: 1834–1847.

- Succi, C., and M. Canovi. 2020. “Soft Skills to Enhance Graduate Employability: Comparing Students and Employers’ Perceptions.” Studies in Higher Education 45 (9): 1834–1847. doi:10.1080/03075079.2019.1585420.

- Tang, K. N. 2019. “Beyond Employability: Embedding Soft Skills in Higher Education.” Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET 18 (2): 1–9.

- Tang, K. N. 2020. “The Importance of Soft Skills Acquisition by Teachers in Higher Education Institutions.” Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences 41 (1): 22–27.

- Tripathy, M. 2020. “Relevance of Soft Skills in Career Success.” MIER Journal of Educational Studies Trends & Practices 10: 91–102. doi:10.52634/mier/2020/v10/i1/1354.

- Tseng, H., X. Yi, and H. T. Yeh. 2019. “Learning-related Soft Skills among Online Business Students in Higher Education: Grade Level and Managerial Role Differences in Self-Regulation, Motivation, and Social Skill.” Computers in Human Behavior 95: 179–186. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.11.035.

- Turgut, D., and Z. Yakar. 2020. “Does Teacher Education Program Affect on Development of Teacher Candidates’ Bioethical Values, Scientific Literacy Levels and Empathy Skills?” International Education Studies 13 (5): 80–93. doi:10.5539/ies.v13n5p80.

- Valtonen, T., U. Leppänen, M. Hyypiä, A. Kokko, J. Manninen, H. Vartiainen, … L. Hirsto. 2021. “Learning Environments Preferred by University Students: A Shift Toward Informal and Flexible Learning Environments.” Learning Environments Research 24: 371–388. doi:10.1007/s10984-020-09339-6.

- van der Kleij, F. M. 2019. “Comparison of Teacher and Student Perceptions of Formative Assessment Feedback Practices and Association with Individual Student Characteristics.” Teaching and Teacher Education 85: 175–189. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2019.06.010.

- van Der Vleuten, C. P., and L. W. Schuwirth. 2019. “Assessment in the Context of Problem-Based Learning.” Advances in Health Sciences Education 24 (5): 903–914. doi:10.1007/s10459-019-09909-1.

- Vista, A. 2020. “Data-driven Identification of Skills for the Future: 21st-Century Skills for the 21st-Century Workforce.” Sage Open 10 (2), doi:10.1177/2158244020915904.

- Wang, H., A. Tlili, J. D. Lehman, H. Lu, and R. Huang. 2021. “Examining the key Influencing Factors on College Students’ Higher-Order Thinking Skills in the Smart Classroom Environment.” International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 18 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1186/s41239-020-00238-7.

- Wesselink, R., A. M. Dekker-Groen, H. J. A. Biemans, and N. Mulder. 2010. “Using an Instrument to Analyse Competence-Based Study Programmes: Experiences of Teachers in Dutch Vocational Education and Training.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 42: 813–829. doi:10.1080/00220271003759249.

- Wesselink, R., E. R. Van den Elsen, H. J. A. Biemans, and M. Mulder. 2007. “Competence-based VET as Seen by Dutch Researchers.” European Journal for Vocational Education and Training 40: 38–51.

- Wijnia, L., E. M. Kunst, M. van Woerkom, and R. F. Poell. 2016. “Team Learning and its Association with the Implementation of Competence-Based Education.” Teaching and Teacher Education 56: 115–126. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2016.02.006.

- Wu, Q., and T. Jessop. 2018. “Formative Assessment: Missing in Action in Both Research-Intensive and Teaching Focused Universities?” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 43 (7): 1019–1031. doi:10.1080/02602938.2018.1426097.

- Wu, H. Z., and Q. T. Wu. 2020. “Impact of Mind Mapping on the Critical Thinking Ability of Clinical Nursing Students and Teaching Application.” Journal of International Medical Research 48 (3), doi:10.1177/0300060519893225.

- Xie, F., and A. Derakhshan. 2021. “A Conceptual Review of Positive Teacher Interpersonal Communication Behaviors in the Instructional Context.” Frontiers in Psychology 12), doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.708490.

- Yan, Z., and D. Boud. 2021. “Conceptualising Assessment-as-Learning.” In Assessment as Learning: Maximising Opportunities for Student Learning and Achievement, edited by Z. Yan, and L. Yang, 11–24. Routledge.

- Yao, M., X. Y. Zhou, Z. J. Xu, R. Lehman, S. Haroon, D. Jackson, and K. K. Cheng. 2021. “Prevalence of Postural Hypotension in Primary, Community and Institutional Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” BMC Family Practice 22 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1186/s12875-020-01313-8.

- Zhang, J. H., L. C. Zou, J. J. Miao, Y. X. Zhang, G. J. Hwang, and Y. Zhu. 2020. “An Individualized Intervention Approach to Improving University Students’ Learning Performance and Interactive Behaviors in a Blended Learning Environment.” Interactive Learning Environments 28 (2): 231–245. doi:10.1080/10494820.2019.1636078.

- Zimmerman, B. J. 1986. “Becoming a Self-Regulated Learner: Which are the Key Subprocesses?” Contemporary Educational Psychology 11: 307–313. doi:10.1016/0361-476X(86)90027-5.