ABSTRACT

This paper aims to conceptualise and operationalise an Employability Capital Growth Model (ECGM) via a systematic literature review of 42,558 manuscripts from Web of Science and Scopus databases published between 2016 and 2022 from the fields of graduate employability and career development incorporating applied psychology, business, education, and management. Two research questions are addressed. (1) How can literature addressing various forms of capital in the context of preparing university graduates for the labour market be integrated to offer a new ECGM? (2) How can various actors, i.e. (a) students and graduates, (b) educators, (c) careers and employability professionals, and (d) graduate employers, operationalise the ECGM? The systematic literature review resulted in a final corpus of 94 manuscripts for qualitative content analysis. Findings led to the construction of a new ECGM comprising nine forms of employability capital (social capital, cultural capital, psychological capital, personal identity capital, health capital, scholastic capital, market-value capital, career identity capital, and economic capital), external factors, and personal outcomes. Twenty-three opportunities for the operationalisation of the ECGM were also identified. The theoretical and conceptual contribution comes from constructing a new ECGM to bridge the fields of graduate employability and career development in the context of preparing individuals for the transition from university into the labour market. The practical contribution comes from operationalising the ECGM at the education-employment nexus. Consequently, developing various forms of capital and an awareness of external factors and personal outcomes can improve students’ and graduates’ employability, benefitting all actors operating in a career ecosystem.

Introduction

Discussions of the purpose and relevance of higher education are dominated by an employability agenda, particularly in the context of increasing tuition fees and competitive labour markets (Healy, Hammer, and McIlveen Citation2022). However, a lack of interdisciplinary research means different literature streams have tended to operate independently, leading to different, albeit often related, conceptualisations of employability (Römgens, Scoupe, and Beausaert Citation2020). Two such fields are graduate employability and career development, whereby ‘despite a clear alignment of research concerns and educational goals, there has been limited theoretical or practical exchange between the two fields’ (Healy, Hammer, and McIlveen Citation2022, 799).

A central conceptual theme in the employability discourse concerns human capital theory, which initially posited that acquiring skills and knowledge via education and training can enhance an individual’s productive capacity by positioning these dimensions as a form of capital (Becker Citation1964). However, conceptualisations of human capital theory from the 1960s as a single linear pathway between education and work ‘cannot explain how education augments productivity, or why salaries have become more unequal, or the role of status’ (Marginson Citation2019, 287). Critics of the economic theory also observe its inability to predict career success and are concerned that it re-enforces rather than helps to address pre-existing inequalities (e.g. Hooley, Sultana, and Thomsen Citation2019; Hooley Citation2020).

Consequently, there is emerging interest in how human capital can be reconceptualised to offer sustainable outcomes for individuals and organisations (Donald, Baruch, and Ashleigh Citation2020). One approach has been to reframe human capital when contextualised within an education setting as a composite of social capital, cultural capital, and scholastic capital (Useem and Karabel Citation1986), subsequently extended to include inner-value and market capital (Baruch, Bell, and Gray Citation2005). Building on this initial work, three established models of employability capital for preparing university students for transition into the labour market have been established and verified through empirical evidence (Tomlinson Citation2017; Clarke Citation2018; Donald, Baruch, and Ashleigh Citation2019).

Tomlinson’s (Citation2017) model positions graduate capital as an accumulation of human capital, social capital, cultural capital, identity capital, and psychological capital. Clarke’s (Citation2018) model offers six dimensions of graduate employability: human capital, social capital, individual attributes, individual behaviours, perceived employability, and labour market factors. Donald, Baruch, and Ashleigh’s (Citation2019) model extends the work of Useem and Karabel (Citation1986) and Baruch, Bell, and Gray (Citation2005) by offering social capital, cultural capital, psychological capital, scholastic capital, market-value capital, and skills capital. Donald and colleagues’ model encompasses these forms of capital under human capital, combining these with career ownership and career advice as dimensions of self-perceived employability.

Scholars worldwide have empirically validated aspects of all three of these models. For example, Tomlinson’s (Citation2017) model in Australia (Benati and Fischer Citation2021), and the UK (Tomlinson et al. Citation2022). Clarke’s (Citation2018) model in China (Ma and Bennett Citation2021) and Australia (Le Rossignol and Kelly Citation2023), and Donald, Baruch, and Ashleigh’s (Citation2019) model in India (Nimmi et al. Citation2021) and the UK (Donald, Baruch, and Ashleigh Citation2019).

However, Peeters et al. (Citation2019) observe that the conceptualisation of employability capital remains inconclusive. This view is supported by Römgens, Scoupe, and Beausaert (Citation2020), who claim that existing models can reinforce and complement each other since various aspects are emphasised more in different models and literature streams. Citation network analysis further supports this position, showing that the graduate employability and career development literature has a limited theoretical or practical exchange between the two fields (Healy, Hammer and McIlveen Citation2022). The variances in conceptualisation can be seen in the three dominant models. The inclusion of identity capital in Tomlinson’s (Citation2017) model addresses criticisms that human capital theory overlooks concerns of class conflict (Bowels and Gintis Citation1975). The coverage of labour market supply and demand in Clarke’s (Citation2018) model acknowledges external factors often absent in conceptualisations of employability capital (Peeters et al. Citation2019). External factors also capture the notion of ‘contingent employability’ (Suleman Citation2021, 548). Additionally, the acknowledgement of career ownership and career advice in Donald, Baruch, and Ashleigh’s (Citation2019) model, and the influence on perceived employability, alludes to the need for individuals to operationalise their different forms of capital to realise personal outcomes (Ho et al. Citation2022).

We are concerned that different groups of researchers are operating within their own silos and often applying different terms to the same concept (e.g. the overlap between human capital, educational capital, and scholastic capital). In response, this paper aims to conceptualise and operationalise an Employability Capital Growth Model (ECGM) for preparing individuals to transition from university into the labour market by reviewing literature from 2016 to 2022. The timespan captures the five years since Tomlinson’s, Clarke’s and Donald and colleagues’ models were published online (all in 2017), plus a year beforehand to cover articles whose publication date may have overlapped with the peer review process. Our focus is on research from applied psychology, business, education, and management to address calls for integrating different literature streams (Römgens, Scoupe, and Beausaert Citation2020; Healy, Hammer and McIlveen Citation2022).

Consequently, this paper aims to conceptualise and operationalise an Employability Capital Growth Model (ECGM) via a systematic literature review of 42,558 manuscripts from Web of Science and Scopus databases published between 2016 and 2022 from the fields of graduate employability and career development incorporating applied psychology, business, education, and management. Two research questions are addressed. (1) How can literature addressing various forms of capital in the context of preparing university graduates for the labour market be integrated to offer a new ECGM? (2) How can various actors, i.e. (a) students and graduates, (b) educators, (c) careers and employability professionals, and (d) graduate employers operationalise the ECGM? The theoretical and conceptual contribution comes from constructing a new ECGM to bridge the fields of graduate employability and career development in the context of preparing individuals for the transition from university into the labour market. The practical contribution comes from operationalising the ECGM at the education-employment nexus. Consequently, developing various forms of capital and an awareness of external factors and personal outcomes can improve students’ and graduates’ employability, benefitting all actors operating in a career ecosystem (Ho et al. Citation2022).

Method

The process of conducting a systematic literature review to ensure replicability and trustworthiness incorporates four phases: (1) designing the review, (2) conducting the review, (3) analysing, and (4) writing up the review (Snyder Citation2019; Williams et al. Citation2021).

Designing the review

A systematic literature review is considered a suitable approach when multiple researchers across different literature streams have studied a particular phenomenon but conceptualised the phenomenon in different ways (Snyder Citation2019; Williams et al. Citation2021). This is the case in the context of employability capital since the conceptualisation of the phenomena remains inconclusive (Römgens, Scoupe, and Beausaert Citation2020) across the fields of applied psychology, business, education, and management (e.g., Tomlinson Citation2017; Clarke Citation2018; Donald, Baruch, and Ashleigh Citation2019). Furthermore, the graduate employability and career development literature streams have limited theoretical or practical exchange of ideas (Healy, Hammer and McIlveen Citation2022). The target audience for our paper is (1) scholars across the fields of graduate employability and career development interested in the development and conceptualisation of employability capital theory, and (2) actors, including students and graduates, educators, careers and employability professionals, and graduate employers who may operationalise the proposed ECGM. A three-stage process was applied to offer the final corpus following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines (Page et al. Citation2021).

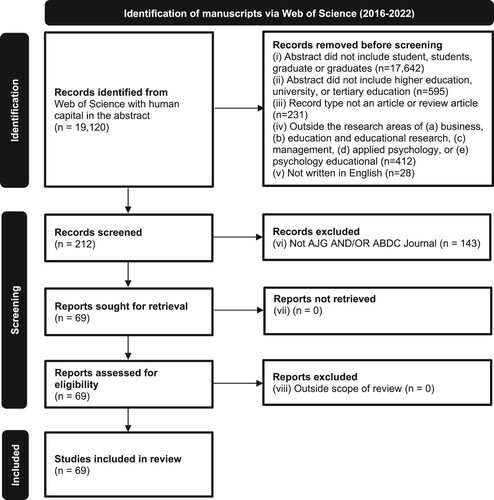

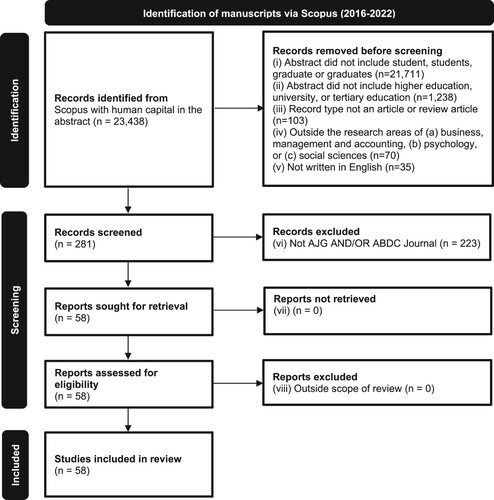

Stage one involved identifying potential literature for inclusion in the final cohort via a search of the Web of Science and Scopus databases. We opted for a date range of 2016–2022 to align with the research questions and covered the five years since the three established models of employability capital for preparing university students for transition into the labour market were published online in 2017 (Tomlinson Citation2017; Clarke Citation2018; Donald, Baruch, and Ashleigh Citation2019). For Web of Science, we searched abstracts for (Human Capital AND (Student OR Students OR Graduate OR Graduates) AND (Higher Education OR University OR Tertiary Education)). We then filtered by article type (Article or Review Article), by Web of Science Categories ((a)business, (b) education & educational research, (c) management, (d) psychology applied, and (e) psychology educational), and by language (English). For Scopus, we followed the same process, albeit using Scopus categories ((a) business, management, and accounting, (b) psychology, and (c) social sciences).

In stage two, the manuscripts were manually screened and excluded if the manuscript was not published in a journal included in the Academic Journal Guide (AGS) 2021 AND/OR the Australian Business Deans Council (ABDC) Citation2023 Journal Quality List. Our decision was informed by guidance from Williams et al. (Citation2021), who also used the ABDC journal list, suggesting it offers a suitable level of coverage (i.e. not limited to ‘top ranked’ journals only, but not including manuscripts from other journals where it is more difficult to determine quality). Stage three collated the remaining records from Web of Science and Scopus, and duplicate manuscripts were excluded, providing the final corpus for qualitative content analysis.

Conducting the review

The next step involved applying the three-step search and inclusion criteria whereby an initial 42,558 manuscripts were identified across Web of Science and Scopus. evidences the Web of Science process leading to 69 results. evidences the Scopus process leading to 58 results. The two sub-corpuses were combined to give 127 results, and 33 duplicates were removed, resulting in a final corpus (n = 94).

Figure 1. shows the PRISMA flow diagram, which we adopted to evidence our systematic review and identification of the sub-corpus from Web of Science of n = 69 manuscripts (based on the structure offered by Page et al. Citation2021).

Figure 2. shows the PRISMA flow diagram, which we adopted to evidence our systematic review and identification of the sub-corpus from Scopus of n = 58 manuscripts (based on the structure offered by Page et al. Citation2021).

Analysis

The two research questions and the systematic literature review drove the decision to adopt the approach of qualitative content analysis. The themes (forms of capital) and codes were of greater significance than the number of times they are mentioned, given the aim of integrating literature from the fields of graduate employability and career development. For research question one, conventional content analysis was adopted to derive the themes and codes directly from the manuscripts within the final corpus (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005). For research question two, directed content analysis adopted the four groups of (i) students and graduates, (ii) educators, (iii) careers and employability professionals, and (iv) employers as themes for operationalisation. Conventional content analysis subsequently populated these four groups via coding categories derived directly from the text data of the manuscripts within the final corpus.

The three researchers involved in this project initially coded the corpus individually and identified codes and themes relating to the development of a new ECGM (research question one) and operationalisation across four groups of students and graduates, educators, careers and employability professionals, and graduate employers (research question two). Coding was initially done manually by each of the three authors, and then codes and themes were compared. The inter-coder reliability score was the degree of alignment between the codes and themes identified by each of the researchers, which evidenced strong inter-coder reliability above 90 per cent (r = 0.92). The strong level of agreement combined with evidence of the process for the systematic literature review ( and ) ensured the four criteria of ‘credibility’, ‘transferability’, ‘dependability’, and ‘confirmability’ for establishing trustworthiness were met (Lincoln and Guba Citation1985). The research team subsequently agreed upon a final set of codes and themes relating to the two research questions.

Writing up the review

The final stage of the method to ensure replicability and trustworthiness involved writing up the findings (Snyder Citation2019; Williams et al. Citation2021). These are reported momentarily under the headings ‘Construction of the Employability Capital Growth Model’ and ‘Operationalisation of the Employability Capital Growth Model’, addressing research questions one and two, respectively.

Limitations of the method

The method section concludes with a brief discussion of the limitations, as is the norm for systematic literature reviews (Williams et al. Citation2021).

Our inclusion criteria restricted the year of publication (2016–2022) and the research areas (applied psychology, business, education or management). We also only searched two databases (Web of Science and Scopus), and we restricted our corpus based on language (published in English) and the need to be published in a journal featured on one or both of two journal lists (AJG Citation2021 and ABDC Citation2023). Consequently, future research may consider looking at different timespans, research areas, databases, search strings or publication languages. Additionally, other forms of literature may be of interest to explore (e.g. journals outside the two rankings lists, books, edited collections, grey literature, etc.) which were beyond the scope of our research.

Despite the limitations mentioned, the criteria that we adopted did adhere to guidelines for conducting a systematic literature review and ensuring that our work is replicable and trustworthy (Snyder Citation2019; Page et al. Citation2021; Williams et al. Citation2021).

Findings

Construction of the employability capital growth model

Research question one asked: How can literature addressing various forms of capital in the context of preparing university graduates for the labour market be integrated to offer a new ECGM?

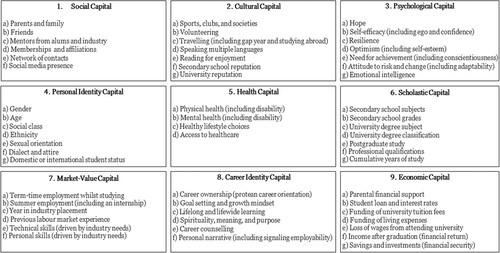

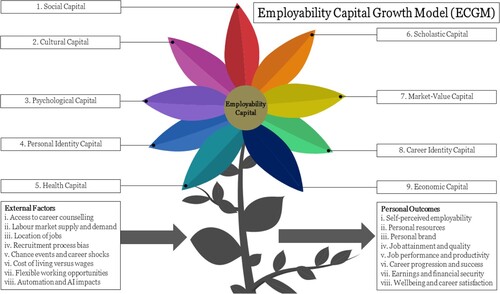

The qualitative content analysis identified nine forms of employability capital, external factors, and personal outcomes. offers a definition for each theme. summarises the nine themes as forms of employability capital and their respective codes. presents the ECGM constructed of the nine forms of employability capital, external factors, and personal outcomes. The codes for external factors and personal outcomes are provided in .

Table 1. Development of the Employability Capital Growth Model.

Operationalisation of the employability capital growth model

Research question two asked: How can various actors, i.e. (a) students and graduates, (b) educators, (c) careers and employability professionals, and (d) graduate employers operationalise the ECGM?

presents the definitions and associated codes from the qualitative content analysis for each theme.

Table 2. Operationalisation of the Employability Capital Growth Model.

Additional online materials

A Microsoft Excel file containing supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2023.2219270, offering a more detailed mapping of the various manuscripts within the corpus to the different themes and codes to ensure transparency and trustworthiness. The five tabs included in the file include (i) an outline of the method, (ii) the final corpus of n = 94 manuscripts, (iii) descriptive statistics (year of publication, name of journal, and article classification), (iv) qualitative content analysis for research question one, and (v) qualitative content analysis for research question two.

Discussion

The interconnected nature of different forms of employability capital

The ECGM acknowledges the interlinked nature of different forms of capital to offer personal resources (Tomlinson Citation2017; Ho et al. Citation2022; Pham Citation2021; Tajuddin et al. Citation2022) and reflects employability as ‘a multidimensional, lifelong, and life-wide phenomenon’ (Jackson and Bridgstock Citation2021, 724). The occupational context and employer preferences will also influence the relative significance of each form of capital when determining employability and employment outcomes. Taken together, our model considers the person, context, and time dimensions of a sustainable career (De Vos, Van der Heijden, and Akkermans Citation2020). The relational and processual acquisition of different forms of capital leads to the accumulation of personal resources (Tomlinson Citation2017), whereby time represents an ongoing change process played out across various employment contexts. Our model also incorporates three approaches to employability: ‘position (based on social background), possession (of human capital), and process (of career self-management)’ (Okay-Somerville and Scholarios Citation2017, 1275).

The literature review identified several links between different forms of capital. A student’s grade point average (GPA) and degree course are indicators of initial and life time earnings (Agopsowicz et al. Citation2020). A lack of family finances can act as a barrier to participating in higher education (Findlay and Hermannsson Citation2019), taking part in extracurricular activities whilst at university (Walker Citation2018), or pursuing a Master’s (Jung and Lee Citation2019). Gender, age, and social class have also been shown to impact student performance during their degree studies (Barra and Zotti Citation2017), whilst students who have to rely on ongoing employment alongside their studies are less likely to participate in internships (Jackson and Bridgstock Citation2021).

Their exclusion is problematic since internships and placements can increase networks (Jackson, Riebe, and Macau Citation2022) and enhance job quality after graduation (González-Romá, Gamboa, and Peiró Citation2018). Additionally, working-class graduates in Canada struggle to mobilise social and personal capital (Lehmann Citation2019), reflecting the impacts of personal identity capital on academic performance (Barra and Zotti Citation2017). Our findings capture how capital accumulation helps the further accumulation of capital (Gachino and Worku Citation2019) at each capital's form level and the composite level of employability capital. Consequently, ‘our agency goals can be thwarted by economic insufficiencies leaving students with unequal resources to act and to participate as citizens in higher education’ (Walker Citation2018, 566).

The literature also highlights some conflicts around the interactions between different forms of capital. One such example concerns the reputation of the university that an individual attends. Cheong et al. (Citation2018) observe how institutional reputation plays a strong role in choice of university and a moderate role in employability perceptions. Additionally, Cheong, Leong, and Hill (Citation2021) found that parents placed significance emphasis on the reputation of the university whilst employers placed greater emphasis on skills when determining perceptions of students’ employability. However, Mihut (Citation2022) found that skills match between applicants and jobs impacted the likelihood of being invited to interview, whereas university prestige did not. Yet, Souto-Otero and Bialowolski (Citation2021) observed how institutional prestige is the second most important factor to employers behind skills.

The interconnected nature of different actors

The literature evidences the interconnected and interdependent nature of different actors operating within a career ecosystem (Baruch Citation2013). Collaboration across university career services, educators, and employers can ensure awareness of each actor’s needs (Souto-Otero and Bialowolski Citation2021) and bridge the links between higher education and the labour market (Clarke Citation2018). Embedding deeper industry engagement into the learning activities can build networks and enhance course content design via guest lectures and experiential learning (Caballero, Álvarez-González, and López-Miguens Citation2020). There is also an opportunity to embed entrepreneurial and innovation aspects into the curriculum through partnerships between educators and industry to increase entrepreneurial intention (Jones, Meckel, and Taylor Citation2021). Embedding career development interventions into the curriculum can also enhance student engagement (Padgett and Donald Citation2023), whilst it is posited that academics can play a more influential role during a year-in-industry placement (Donald and Hughes Citation2023).

Career development interventions can also be run outside the curriculum. However, universities need to target their resources to support students most in need (Barra and Zotti Citation2017). Employers and career services need to be aware of gender, class, and ethnicity differences to make the university-to-work transition more equitable (Hooley, Hanson, and Clark Citation2022). One approach is to explicitly communicate the ‘rules of the game’ with a focus on the value of work experience, self-assessment activities, and personal narratives to signal employability to prospective employers (Singh and Fan Citation2021).

A further approach is to combine resources from various actors to provide students with tailored career advice, mentoring, and access to information to make informed decisions (Ho et al. Citation2022). Fostering a protean career orientation can facilitate students to identify and acquire different forms of capital and accumulate these over time (Ng, Wut, and Chan Citation2022), leading to enhanced self-perceived employability (Okay-Somerville and Scholarios Citation2017). Supporting students throughout their degree takes on increased significance, given that with each additional year of study, self-perceived employability decreases due to external market factors (Donald, Baruch, and Ashleigh Citation2019). Examples of these external market factors include an awareness of the competition for jobs (e.g. rejection decisions during the application and selection process) and the location of jobs (e.g. lack of jobs in the individual’s desired work location).

Theoretical and conceptual implications

Our ECGM () construction via a systematic literature review ( and ) advances an emerging interest in how human capital can be reconceptualised to offer sustainable outcomes for individuals and organisations (Donald, Baruch, and Ashleigh Citation2020). However, we avoid explicitly using the term ‘human capital’ in our ECGM for two reasons. First, critics of human capital theory (e.g. Hooley, Sultana, and Thomsen Citation2019; Marginson Citation2019; Hooley Citation2020) often frame their arguments on initial conceptualisations of human capital from the 1960s (e.g. Becker Citation1964) rather than on more recent incarnations of human capital as a composite of different forms of capital (e.g. Useem and Karabel Citation1986; Baruch, Bell, and Gray Citation2005; Donald, Baruch, and Ashleigh Citation2019). Secondly, albeit related to the first reason, definitions of human capital vary by field, resulting in various conceptualisations occurring in parallel (e.g. three conceptual models initially published online in 2017: Tomlinson Citation2017; Clarke Citation2018; Donald, Baruch, and Ashleigh Citation2019).

Consequently, we opt for the term ‘employability capital’, which we define as the accumulation of social capital, cultural capital, psychological capital, personal identity capital, health capital, scholastic capital, market-value capital, career identity capital, and economic capital. Our framing of employability capital () captures the stand-alone and interrelated dimensions of the various forms of capital. Moreover, our inclusion of external factors and personal outcomes ( and ) addresses the limitations of previous capital models that have failed to include these dimensions explicitly. Our approach also captures the temporal development of capital formation across one’s lifespan (Tomlinson and Jackson Citation2021).

We also offer clear definitions of each of the nine forms of employability capital, informed by a holistic interpretation from the fields of applied psychology, business, education, and management. This contributes by offering a shared platform to advance the framing and study of employability capital theory since researchers have used different terminology to refer to similar constructs, creating unnecessary barriers to inter- and intra-disciplinary research across graduate employability and career development (Römgens, Scoupe, and Beausaert Citation2020; Healy, Hammer and McIlveen Citation2022).

Practical implications

The practical contribution comes from operationalising the model at the education-employment nexus. We address the lack of attention in the literature on developing various forms of capital to improve students’ and graduates’ employability for the benefit of all actors (Ho et al. Citation2022). Educators, career and employability professionals, and employers must collaborate to raise awareness of each other’s needs when developing students to undertake the university-to-work transition (Souto-Otero and Bialowolski Citation2021).

From a curriculum perspective, employability capital can be developed via student-centred pedagogical practices (Nghia, Giang, and Quyen Citation2019), problem-based learning (Belderbos Citation2019), and opportunities for personal reflection (Ng, Wut, and Chan Citation2022). Incorporating guest lectures from alums and employers can help bridge the links between higher education and the labour market (Caballero, Álvarez-González, and López-Miguens Citation2020). A focus on entrepreneurial development can also enhance the opportunities available to students following graduation (Jones, Meckel, and Taylor Citation2021) by enhancing entrepreneurial intention (Westhead and Solesvik Citation2016). Embedding different forms of employability capital into the curriculum can also improve access to career guidance and advice for students early in their degree (Donald, Baruch, and Ashleigh Citation2019).

Careers and employability professionals can operationalise the ECGM by helping students and graduates to reflect on the forms of capital they need to develop via goal-directed behaviour (Souto-Otero and Bialowolski Citation2021). These individuals should be encouraged to take ownership of their careers (Okay-Somerville and Scholarios Citation2017), develop networks (Jackson, Riebe, and Macau Citation2022), commit to lifelong and lifewide learning (Ho et al. Citation2022), and understand the value of work experience (Tomlinson Citation2017). Additionally, university career services should engage with employers to help students create personal narratives to signal employability to prospective employers (Singh and Fam 2021; Jackson, Riebe, and Macau Citation2022). The approach can enable students to connect theory and practice via employability development opportunities (Pitan and Muller Citation2020). Targeting support to students who need it the most is essential since their perceived employability is impacted by access to university initiatives (Suleman Citation2021).

Finally, from the employer’s perspective, a deep and meaningful discussion is needed with universities to communicate current and future needs (Clarke Citation2018), recognising changes over time (Assaad, Krafft, and Salehi-Isfahani Citation2018). A holistic approach is also required to consider external factors to graduate employability, including an awareness of bias in the recruitment process to make employment outcomes more equitable (Hooley, Hanson, and Clark Citation2022). Understanding employer needs is essential since each employer will place different emphases on the different forms of capital that constitute employability capital (Ng, Wut, and Chan Citation2022). Employers themselves can play a greater role in shaping university education and providing work experience opportunities (Cheong, Leong, and Hill Citation2021).

Collaborative engagement across these actors can help graduates achieve outcomes of (i) self-perceived employability, (ii) personal resources, (iii) personal brand, (iv) job attainment and quality, (v) job performance and productivity, (vi) career progression and success, (vii) earnings and financial security, and (viii) wellbeing and career satisfaction. Employers can benefit from enhancing employability capital beyond university boundaries, including sustainable outcomes of productivity, innovation, and profitability (Jakubik Citation2020). Universities benefit from employment outcomes and associated status leading to the attraction of future students and the associated revenue they bring (Donald, Baruch, and Ashleigh Citation2019).

Future research

Future research could empirically test, validate, and modify the new ECGM proposed in this paper. The potential mediating and moderating roles of different forms of capital may be of interest to explore, coupled with a consideration of additional operationalisation opportunities. For example, forms of capital have previously been used as mediating variables in employability research (e.g. Ho et al. Citation2022). Quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods approaches that include various actors could be used. The exploration and comparison of views of different actors could help to highlight areas of agreement or conflict and opportunities to address these. Moreover, two-wave or longitudinal studies may help to identify changes over time, given the evolving nature of contemporary labour markets and the future of work. There may also be merit in engaging academics and practitioners who have historically used different approaches and models to accept or advance the new ECGM as a new foundation for collaborative, interdisciplinary, and intradisciplinary work.

Conclusion

The aim of our paper was to conceptualise and operationalise an Employability Capital Growth Model (ECGM). This was achieved via a systematic literature review of 42,558 manuscripts from Web of Science and Scopus databases published between 2016 and 2022 from the fields of graduate employability and career development incorporating applied psychology, business, education, and management. Two research questions were addressed. (1) How can literature addressing various forms of capital in the context of preparing university graduates for the labour market be integrated to offer a new ECGM? (2) How can various actors, i.e. (a) students and graduates, (b) educators, (c) careers and employability professionals, and (d) graduate employers operationalise the ECGM? The systematic literature review resulted in a final corpus of 94 manuscripts for qualitative content analysis. The theoretical and conceptual contribution comes from constructing a new ECGM to bridge the fields of graduate employability and career development in the context of preparing individuals for the transition from university into the labour market. The practical contribution comes from operationalising the ECGM at the education-employment nexus. Consequently, developing various forms of capital and an awareness of external factors and personal outcomes can improve students’ and graduates’ employability, benefitting all actors operating in a career ecosystem (Ho et al. Citation2022).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (103.5 KB)Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr Johanna Annala (Associate Editor at Studies in Higher Education) and the anonymous peer reviewers for their valuable advice and guidance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- *indicates that the reference forms part of the final cohort of the systematic literature review.

- Academic Journal Guide (AJG). 2021. https://charteredabs.org/academic-journal-guide-2021/

- *Agopsowicz, A., C. Robinson, R. Stinebrickner, and T. Stinebrickner. 2020. “Careers and Mismatch for College Graduates.” Journal of Human Resources 55 (4): 1194–1221. doi:10.3368/jhr.55.4.0517-8782R1.

- *Assaad, R., C. Krafft, and D. Salehi-Isfahani. 2018. “Does the Type of Higher Education Affect Labor Market Outcomes? Evidence from Egypt and Jordan.” Higher Education 75: 945–995. doi:10.1007/s10734-017-0179-0.

- Australian Business Deans Council (ABDC). 2023. https://abdc.edu.au/abdc-journal-quality-list/OtherInfo

- *Barra, C., and R. Zotti. 2017. “What we Can Learn from the use of Student Data in Efficiency Analysis Within the Context of Higher Education?” Tertiary Education and Management 23 (3): 276–303. doi:10.1080/13583883.2017.1329450.

- Baruch, Y. 2013. “Careers in Academe: The Academic Labour Market as an Ecosystem.” Career Development International 18 (2): 196–210. doi:10.1108/CDI-09-2012-0092.

- Baruch, Y., M. P. Bell, and D. Gray. 2005. “Generalist and Specialist Graduate Business Degrees: Tangible and Intangible Value.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 67 (1): 51–68. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2003.06.002.

- Becker, G. S. 1964. Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis with Special Reference to Education. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- *Belderbos, T. 2019. “The Employability of International Branch Campus Graduates: Evidence from Malaysia.” Higher Education Skills and Work-Based Learning 10 (10): 141–154. doi:10.1108/HESWBL-02-2019-0027.

- Benati, K., and J. Fischer. 2021. “Beyond Human Capital: Student Preparation for Graduate Life.” Education + Training 63 (1): 151–163. doi:10.1108/ET-10-2019-0244.

- Bowels, S., and H. Gintis. 1975. “The Problem with Human Capital Theory – A Marxian Critique.” The American Economic Review 65 (2): 74–82.

- *Caballero, G., P. Álvarez-González, and M. J. López-Miguens. 2020. “How to Promote the Employability Capital of University Students? Developing and Validating Scales.” Studies in Higher Education 45 (12): 2634–2652. doi:10.1080/03075079.2020.1807494.

- *Cheong, K.-C., C. Hill, Y.-C. Leong, and C. Zhang. 2018. “Employment as a Journey or a Destination? Interpreting Graduates’ and Employers’ Perceptions – a Malaysia Case Study.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (4): 702–718. doi:10.1080/03075079.2016.1196351.

- *Cheong, K.-C., Y.-C. Leong, and C. Hill. 2021. “Pulling in one Direction? Stakeholder Perceptions of Employability in Malaysia.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (4): 807–820. doi:10.1080/03075079.2019.1654449.

- *Clarke, M. 2018. “Rethinking Graduate Employability: The Role of Capital, Individual Attributes and Context.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (11): 1923–1937. doi:10.1080/03075079.2017.1294152.

- De Vos, A., B. I. J. M. Van der Heijden, and J. Akkermans. 2020. “Sustainable Careers: Towards a Conceptual Model.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 117: 103196. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2018.06.011.

- Donald, W. E., Y. Baruch, and M. J. Ashleigh. 2020. “Striving for Sustainable Graduate Careers: Conceptualization via Career Ecosystems and the new Psychological Contract.” Career Development International 25 (2): 90–110. doi:10.1108/CDI-03-2019-0079.

- Donald, W. E., and H. P. N. Hughes. 2023. “How academics can play a more influential role during a year-in-industry placement: A contemporary critique and call for action.” Industry and Higher Education. doi:10.1177/09504222231162059.

- *Donald, W. E., Y. Baruch, and M. J. Ashleigh. 2019. “The Undergraduate Self-Perception of Employability: Human Capital, Careers Advice and Career Ownership.” Studies in Higher Education 44 (4): 599–614. doi:10.1080/03075079.2017.1387107.

- *Findlay, J., and K. Hermannsson. 2019. “Social Origin and the Financial Feasibility of Going to University: The Role of Wage Penalties and Availability of Funding.” Studies in Higher Education 44 (11): 2025–2040. doi:10.1080/03075079.2018.1488160.

- *Gachino, G. G., and G. B. Worku. 2019. “Learning in Higher Education: Towards Knowledge, Skills and Competency Acquisition.” International Journal of Educational Management 33 (7): 1746–1770. doi:10.1108/IJEM-10-2018-0303.

- *González-Romá, V., J. P. Gamboa, and J. M. Peiró. 2018. “University Graduates’ Employability, Employment Status, and Job Quality.” Journal of Career Development 45 (2): 132–149. doi:10.1177/0894845316671607.

- Healy, M., J. L. Brown, and C. Ho. 2022a. “Graduate Employability as a Professional Proto-Jurisdiction in Higher Education.” Higher Education 83: 1125–1142. doi:10.1007/s10734-021-00733-4.

- Healy, M., S. Hammer, and P. Mcllveen. 2022b. “Mapping Graduate Employability and Career Development in Higher Education Research: A Citation Network Analysis.” Studies in Higher Education 47 (4): 799–811. doi:10.1080/03075079.2020.1804851.

- *Ho, T. T. H., V. H. Le, D. T. Nguyen, C. T. P. Nguyen, and H. T. T. Nguyen. 2022. “Effects of Career Development Learning on Students’ Perceived Employability: A Longitudinal Study.” Higher Education, doi:10.1007/s10734-022-00933-6.

- Hooley, T. 2020. “Career Development and Human Capital Theory: Preaching the Education Gospel.” In The Oxford Handbook of Career Development, edited by P. Robertson, T. Hooley, and P. McCash, 49–64. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge.

- Hooley, T., J. Hanson, and L. Clark. 2022. “Exploring Students’ and Graduates’ Attitudes to the Process of Transition to the Labour Market.” Industry and Higher Education, doi:10.1177/09504222221111298.

- Hooley, T., R. Sultana, and R. Thomsen, eds. 2019. Career Guidance for Social Justice: Contesting Neoliberalism. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge.

- Hsieh, H.-F., and S. E. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15 (9): 1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Jackson, D., and R. Bridgstock. 2021. “What Actually Works to Enhance Graduate Employability? The Relative Value of Curricular, co-Curricular, and Extra-Curricular Learning and Paid Work.” Higher Education 81 (4): 723–739. doi:10.1007/s10734-020-00570-x.

- *Jackson, D., L. Riebe, and F. Macau. 2022. “Determining Factors in Graduate Recruitment and Preparing Students for Success.” Education + Training, doi:10.1108/ET-11-2020-0348.

- *Jakubik, M. 2020. “Enhancing Human Capital Beyond University Boundaries.” Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning 10 (2): 434–446. doi:10.1108/HESWBL-06-2019-0074.

- *Jones, O., P. Meckel, and D. Taylor. 2021. “Situated Learning in a Business Incubator: Encouraging Students to Become Real Entrepreneurs.” Industry and Higher Education 35 (4): 367–383. doi:10.1177/09504222211008117.

- *Jung, J., and S. J. Lee. 2019. “Exploring the Factors of Pursuing a Master’s Degree in South Korea.” Higher Education 78 (5): 855–870. doi:10.1007/s10734-019-00374-8.

- *Lehmann, W. 2019. “Forms of Capital in Working-Class Students’ Transition from University to Employment.” Journal of Education and Work 32 (4): 347–359. doi:10.1080/13639080.2019.1617841.

- Le Rossignol, K., and M. Kelly. 2023. “A Career Ecosystem Approach to Developing Student Agency Through Digital Storymaking.” In Handbook of Research on Sustainable Career Ecosystems for University Students and Graduates, Edited by W. E. Donald, Chapter 9. Pennsylvania: IGI Global.

- Lincoln, Y. S., and E. G. Guba. 1985. Naturalist Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Ma, Y., and D. Bennett. 2021. “The Relationship Between Higher Education Students’ Perceived Employability, Academic Engagement and Stress among Students in China.” Education + Training 63 (5): 744–762. doi:10.1108/ET-07-2020-0219.

- *Marginson, S. 2019. “Limitations of Human Capital Theory.” Studies in Higher Education 44 (2): 287–301. doi:10.1080/03075079.2017.1359823.

- *Mihut, G. 2022. “Does University Prestige Lead to Discrimination in the Labor Market? Evidence from a Labor Market Field Experiment in Three Countries.” Studies in Higher Education 47 (6): 1227–1242. doi:10.1080/03075079.2020.1870949.

- *Ng, P. M. L., T. M. Wut, and J. K. Y. Chan. 2022. “Enhancing Perceived Employability Through Work-Integrated Learning.” Education + Training 64 (4): 559–576. doi:10.1108/ET-12-2021-0476.

- *Nghia, T. L. H., H. T. Giang, and V. P. Quyen. 2019. “At-Home International Education in Vietnamese Universities: Impact on Graduates’ Employability and Career Prospects.” Higher Education 78: 817–834. doi:10.1007/s10734-019-00372-w.

- Nimmi, P. M., K. A. Zakkariya, and P. R. Rahul. 2021. “Channelling Employability Perceptions through Lifelong Learning: An Empirical Investigation.” Education + Training 63 (5): 763–776. doi:10.1108/ET-10-2020-0295.

- *Okay-Somerville, B., and D. Scholarios. 2017. “Position, Possession or Process? Understanding Objective and Subjective Employability During University-to-Work Transitions.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (7): 1275–1291. doi:10.1080/03075079.2015.1091813.

- *Padgett, R. C., and W. E. Donald. 2023. “Enhancing Self-Perceived Employability via a Curriculum Intervention: A Case of ‘The Global Marketing Professional’ Module.” Higher Education Skills and Work-Based Learning 51 (1): 272–287. doi:10.1108/HESWBL-03-2022-0073.

- Page, M. J., D. Moher, P. M. Bossuyt, I. Boutron, T. C. Hoffmann, C. D. Mulrow, L. Shamseer, et al. 2021. “PRISMA 2020 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated Guidance and Exemplars for Reporting Systematic Reviews.” British Medical Journal 372 (1): 71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71.

- Peeters, E., J. Nelissen, N. De Cuyper, A. Forrier, M. Verbruggen, and H. De Witte. 2019. “Employability Capital: A Conceptual Framework Tested Through Expert Analysis.” Journal of Career Development 46 (2): 79–93. doi:10.1177/0894845317731865.

- Pham, T. 2021. “Reconceptualising Employability of Returnees: What Really Matters and Strategic Navigating Approaches.” Higher Education 81 (6): 1329–1345. doi:10.1007/s10734-020-00614-2.

- Pitan, O. S., and C. Muller. 2020. “Student Perspectives on Employability Development in Higher Education in South Africa.” Education + Training 63 (3): 453–471. doi:10.1108/ET-02-2018-0039.

- Römgens, I., R. Scoupe, and S. Beausaert. 2020. “Unraveling the Concept of Employability, Bringing Together Research on Employability in Higher Education and the Workplace.” Studies in Higher Education 45 (12): 2588–2603. doi:10.1080/03075079.2019.1623770.

- Singh, J. K. N., and S. X. Fan. 2021. “International education and graduate employability: Australian Chinese graduates’ experiences.” Journal of Education and Work 34 (5-6): 663–675. doi:10.1080/13639080.2021.1965970.

- Snyder, H. 2019. “Literature Review as a Research Methodology: An Overview and Guidelines.” Journal of Business Research 104: 333–339. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039.

- *Souto-Otero, M., and P. Bialowolski. 2021. “Graduate Employability in Europe: The Role of Human Capital, Institutional Reputation and Network Ties in Europeam Graduate Labour Markets.” Journal of Education and Work 34 (5-6): 611–631. doi:10.1080/13639080.2021.1965969.

- *Suleman, F. 2021. “Revisiting the Concept of Employability Through Economic Theories: Contributions, Limitations and Policy Implications.” Higher Education Quarterly 75 (4): 548–561. doi:10.1111/hequ.12320.

- *Tajuddin, S. N. A., K. A. Bahari, F. M. Al Majdhoub, S. B. Baboo, and H. Samson. 2022. “The Expectations of Employability Skills in the Fourth Industrial Revolution of the Communication and Media Industry in Malaysia.” Education + Training 65 (5): 662–680. doi:10.1108/ET-06-2020-0171.

- *Tomlinson, M. 2017. “Forms of Graduate Capital and Their Relationship to Graduate Employability.” Education + Training 59 (4): 338–352. doi:10.1108/ET-05-2016-0090.

- Tomlinson, M., and D. Jackson. 2021. “Professional Identity Formation in Contemporary Higher Education Students.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (4): 885–900. doi:10.1080/03075079.2019.1659763.

- Tomlinson, M., H. McCafferty, A. Port, N. Maguire, A. E. Zableski, A. Butnaru, M. Charles, and S. Kirby. 2022. “Developing Graduate Employability for a Challenging Labour Market: The Validation of the Graduate Capital Scale.” Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education 14 (3): 1193–1209. doi:10.1108/JARHE-04-2021-0151.

- Useem, M., and J. Karabel. 1986. “Pathways to top Corporate Management.” American Sociology Review 51 (2): 184–200. doi:10.2307/2095515.

- *Walker, M. 2018. “Dimensions of Higher Education and the Public Good in South Africa.” Higher Education 76 (3): 555–569. doi:10.1007/s10734-017-0225-y.

- *Westhead, P., and M. Z. Solesvik. 2016. “Entrepreneurship Education and Entrepreneurial Intention: Do Female Students Benefit?” International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 34 (8): 979–1003. doi:10.1177/0266242615612534.

- Williams, R. I., L. A. Clark, W. R. Clark, and D. M. Raffo. 2021. “Re-examining Systematic Literature Reviews in Management Research: Additional Benefits and Execution Protocols.” European Management Journal 39 (4): 521–533. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2020.09.007.