ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to closely examine the experiences of non-Indigenous academics in marking a single assessment task designed to promote cultural safety practice in a health professional programme. In recognition of institutional racism and significant health and wellbeing disparity in Indigenous wellbeing, cultural safety is recognised as essential knowledge across professions in tertiary education. An assessment task was designed to support students’ written critical reflection to promote their cultural safety practice. A collaborative autoethnography by four academics critically reflected on the tensions in marking this reflective assignment as non-Indigenous educators. Thematic analysis was conducted on transcriptions of the authors’ discussions and a framework was developed in response to repeating sites of tension. The Indigenous allyship assessment framework: sharing the load was framed around the central theme of Navigating the Unsettling. It specifically draws attention to navigating the Personal (Heightened Responsibility and Partial Knowledge), Pedagogical (Judge the Meaningful and Feedback Conversations) and Persons and Processes (systems) (Efficiency Culture and Cost of Marking) tensions. Our conclusion was that non-Indigenous educators need to consciously navigate unsettling challenges to do justice to assessment tasks to promote cultural safety.

Introduction

In this collaborative autoethnography, we explore our experiences of marking a single assessment task designed to promote culturally safe practice by health professional students. We are four non-Indigenous academics working to build our capacity as Indigenous allies and have used collaborative autoethnography as a formal strategy to improve our practice. We share our learning to add to the body of literature examining the (appropriate) discomfort of non-Indigenous academics (Carrol, Bascuñán, Sinke, & Restoule, Citation2020; Wolfe, Sheppard, Le Rossignol, & Somerset, Citation2017) navigating (colonised) tertiary education systems (Dudgeon & Fielder, Citation2006; Nakata, Citation2007) and to support other non-Indigenous colleagues seeking to develop their own capabilities in educating for culturally safe practice. All teaching and reflections described in this paper were completed on Wurundjeri and Dja Dja Warrong country in Australia. We would like to acknowledge the land we live and work on and Elders past and present who have educated us and informed our thinking. We would especially like to acknowledge the generous support of Associate Professor Shawana Andrews (Palawa woman and academic), who has supported our journey as allies and the development of the assessment task described here. We use the term Indigenous in this paper to respectfully represent collectively the many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities who are the First Peoples of Australia.

Cultural safety is a concept first developed in the early 90s by Irihapeti Ramsden, a Māori nurse working in New Zealand (Papps & Ramsden, Citation1996). Cultural safety has been widely adopted in education programmes for health professions (Fildes et al., Citation2021), education (Bullen & Roberts, Citation2021) and law (Wood, Citation2013) and is therefore relevant across the tertiary education sector (Page et al., Citation2019). There is a growing body of literature providing principles and guidelines on how best to teach cultural safety (Krusz et al., Citation2022; Public Health Indigenous Leadership in Education (PHILE) Network, Citation2016; Mackean et al., Citation2019). It has recently been defined in a healthcare context as ‘the ongoing critical reflection of health practitioner knowledge, skills, attitudes, practicing behaviours and power differentials in delivering safe, accessible and responsive healthcare free of racism … ’ as ‘ … determined by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals, families and communities’ (APHRA, Citation2020, p. 9). The importance of this approach has been recognised in the regulatory requirement that health professional students are educated about culturally safe practice in Australia (APHRA, Citation2020; Curtis et al., Citation2019; Milligan et al., Citation2021). This articulates the responsibility for programmes to ensure that all students graduate with the knowledge and capabilities to be responsive to the health and wellbeing needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities.

Critical reflection on personal attitudes and responses to Indigenous history, rights and activities is a foundational element of cultural safety. Critical reflection has been described as a process that specifically challenges and questions assumptions, power relations, and structural or systemic bias and their manifestations in one’s actions and practice (Ng et al., Citation2019). There is less advice on how best to assess learner knowledge and skills in this space, although written reflections are a common practice for the assessment of health professions (Delany et al., Citation2018). While there are recognised opportunities and challenges in asking non-Indigenous students to reflect on their privilege and role in structural racism in assessment tasks (Sjorberg & Mcdermott, Citation2016), we chose to set a reflective assessment task to help students with their meaning-making as they further develop their cultural safety capabilities.

We selected the Australian Physiotherapy Association’s (APA’s) second Reconciliation Action Plan (RAP) as the stimulus for the students’ reflection. As the students were in their final semester before graduation, we chose a professional document as a way of reminding students of the commitment of their profession to cultural safety. RAP2 was led and written predominantly by Indigenous Physiotherapists and therefore was also an opportunity for students to recognise Indigenous leadership within their profession. We were aware that Organizational RAPs have been critiqued as being tokenistic, a checklist and value signalling, rather than budgeted and regulated actions for meaningful impact (Foely, Citation2021; Goerke, Citation2019). However, the RAP was identified as a useful document to provoke students’ deeper engagement with the complexity of system-level issues affecting the health and wellbeing experiences of Indigenous people. We saw this as a way for students to question their personal bias and assumptions, understand the actions proposed by their profession, and consider strategies to disrupt personal, professional and structural racism.

It is important for educators designing novel assessment tasks on the margins of their knowledge (in this case non-Indigenous educators working to promote Indigenous ways of knowing) to closely observe and challenge personal bias, so that habits of mind and ‘automatic’ practices do not go unchecked. We decided to use collaborative autoethnography as a method to interrogate our own work on marking a critical reflection assignment, and as a strategy to improve our practice as educators and our efforts towards Indigenous allyship. To situate ourselves within the ‘white privilege’ discourse, we ‘colour ourselves in’ with some partial details of our history below. As an authorship team, we acknowledge the intersectionality of multiple privileges we benefit from and the discomfort from knowing that we have made, and will make mistakes, as we are trying to do better in critical allyship (Nixon, Citation2019). We have attempted to support cultural safety education while remaining critical of our own motives, bias, assumptions, and lens, and are committed to our own life-long learning in this space.

Louisa Remedios: Since migrating to Australia as a teenager, I have settled on many different lands in Australia and now reside on Wurundjeri country. With Anglo-Indian heritage, I reference my immigrant history as I grew up informed about the invasion and colonisation of India, and I have a growing awareness of structural racism in tertiary education. As an early academic, I reacted quietly to racism, staying invisible and ‘polite’. I now intentionally step (sometimes miss-step) into the ‘space of race’.

Jessica Lees: I am grew up in Wurundjeri country with an extended family heritage of Anglo-Australian ancestry. I am conscious on the unearned advantages my children and I receive from being part of the dominant Anglo-Australian culture. As an early career academic, I have a keen interest in learning about diverse cultural communities, especially those of First Nations peoples and I am committed to understand how I can support Indigenous causes, respect cultural practices and contribute meaningfully to societal transformation.

Carolyn Cracknell: I am a woman of English-Irish ancestry who grew up on territory of the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation and now live and work on Wurundjeri country. My tertiary studies were crucial in unsettling my ways of thinking that were heavily influenced by Western culture. Subsequently, I see higher education as a powerful place for the bias and assumptions of learners to also become ‘unsettled’. As a health professions educator teaching for six years, I still position myself as a learner in the space of cultural safety and allyship and commit to continual critical reflection of my own bias and actions.

Joanne Bolton: Since 2010 I have lived, worked and raised my children on Wurundjeri Country. I identify as Australian, and through marriage, with Ecuadorian culture and my three children experience the benefit of both. I have some experience of disadvantage through economic, social and disability paradigms which has informed my criticality of higher education systems over the past 10 years as a health professions educator.

The Four of Us: The four of us are cis-gender female academics teaching in a post-graduate entry-to-practice physiotherapy programme. With vastly different levels of experience in education, ranging from 5 to 30 + years, we have worked as a team, building cultural safety education into the programme with leadership, guidance and support from Indigenous colleagues. At the time of this writing, LR was a full-time senior academic and Director of Teaching and Learning and had designed (with advice from an Indigenous colleague) the assessment task and related teaching activities described in this paper. JL has previously taught in this subject and was on a casual contract and paid for marking this assessment, while CC was on a part-time fixed-term contract to support teaching and had coordinated and marked this assignment from its inception. JB was invited to join the team to provoke additional criticality due to her more extensive experience and knowledge in educating for cultural safety. She was employed on a part-time, fixed-term contract in a Faculty Academic Specialist role.

The context

The programme is a three-year post-graduate physiotherapy degree at a large metropolitan university hosting approximately 110 students per year. Approximately 20% of the cohort are international students, predominantly from North America and Canada. More rarely, there are one or two Indigenous students enrolled in the programme.

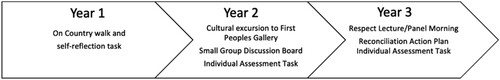

Our intention was to embed cultural safety into subjects across each year of the programme (Remedios et al., Citation2018). provides a visual representation of the teaching and learning activity across the three years. The Year 2 experience is discussed in detail by Bolton and Andrews (Citation2018). The cultural excursion to the First People’s Gallery, and the subsequent student discussions co-taught and scaffolded by an Indigenous and non-Indigenous (JB) educator was a substantial engagement with cultural safety for learners in the programme. Assessed tasks have been built into the second and third year of the programme with the grading of these assignments completed predominately by non-Indigenous academics including staff employed on casual contracts. This paper was based on our reflections on marking the final assessment task completed in the final semester of the programme.

The assessment task

First introduced in 2016, students were required to critically reflect on their Discipline’s Reconciliation Action Plan, Innovate (RAP 2) (Australian Physiotherapy Association (APA), Citation2017). This task was developed to address professional accreditation requirements for cultural competence and culturally responsive practice (Physiotherapy Board of Australia & Physiotherapy Board of New Zealand, Citation2015). Critical reflection was seen as essential to assist students to explore their own and others’ ways of knowing and thinking (Bay & McFarlane, Citation2011; Ng et al., Citation2019). The RAP document provided meaningful context by familiarising the students with the profession’s stated commitment to cultural safety, reinforcing professional and personal responsibility to build knowledge and skills for culturally safe practice. Our aims therefore were to build students’ critical reflection skills, knowledge of Indigenous ways of knowing and issues relevant to cultural safety for practice in their profession.

After a couple of years of running the assignment, we became concerned that students were using deficit language, generalising and stereotyping Indigenous individuals and communities and were not reading and reflecting on more contemporary critiques of the RAP. In response, we introduced the Triple R (Respect, Reconciliation and Reciprocity) Morning during which invited Indigenous and non-Indigenous academics shared their personal perspective on the RAP. In 2020, due to COVID-19, the Triple R morning ran online for two hours via Zoom. It involved mini presentations on individuals’ perspectives followed by discussion and debate on the role and risks of a RAP. To ensure that students listened to learn from the presenters, the reflection task required students to quote from at least three presenters to support their written reflections. We hoped this would build more contemporary and critical (or at least less stereotypical) reflections on respect, reconciliation, and reciprocity within a framework that recognised privilege and power.

As a team, we saw the potential of this assignment to provoke students’ deeper engagement with complex knowledges and skills, while recognising that academic training had not prepared us sufficiently to mark this ‘atypical’ assessment task. Marking this assignment therefore required us to engage more deeply with the complex knowledge and skills required for cultural safety and for Indigenous allyship. In 2020, we decided to develop our scholarship through a collaborative autoethnography, interrogating our marking experience more critically and systematically. Our agenda was to improve on both the academics' and students’ experience of this assessment task. Our aim in writing this paper is to share our learning with other non-Indigenous academics using assessment tasks to build cultural safety capabilities.

Methodology

This study takes an interpretivist and constructivist view in utilising a collaborative autoethnographic approach. Autoethnography research is utilised to study teaching practice to gain deeper understanding of the practice in a more systematic manner (Chawla & Atay, Citation2018). It promotes reflexivity in combination with action (Burke & Jimenez Soffa, Citation2018) with specific attention to self-study on the ‘entanglement’ of self and practice (Fletcher & Bullock, Citation2015). Collaborative autoethnography extends this by drawing on shared narrative as a means to balance individual stories with the experience of the collective (Blalock & Akehi, Citation2018).

Reflexive praxis using a collaborative auto-ethnographic framework is viewed as an effective means to systematically generate data regarding the researchers’ own practices to bring forward tacit knowledge about practice (Roy & Uekusa, Citation2020) that may otherwise go unnoticed and unregulated. In selecting the approach that perceives the self and practice as intertwined, we selected collaborative auto-ethnographic methodology to explore ourselves-in-practice, synthesise our experience about teaching and learning to gain insights for more robust pedagogical practice (Blalock & Akehi, Citation2018; Fletcher & Bullock, Citation2015). LaBoskey (Citation2004) highlights that an important aspect of autoethnographic method is to make evident the features of the practices that were effective, but also, to unpack the areas that were problematic.

To ensure the trustworthiness of our work, we drew on the five key characteristics described by LaBoskey (Citation2004): our reflections were self-initiated and focused; there was an aim to improve our practice; we used an interactive process; it included multiple qualitative methods; and we write with the intention of making the research process transparent. Additionally, the authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data generation

Our reflections were specific to the assessment task as completed in 2020. Three data generation processes were included in this project; (1) individual written reflections, (2) formal audio-recorded collaborative reflections and (3) a further iterative group reflection on the preceding two steps. The formal collaborative reflections were conducted on two occasions where the first three authors met to share their experiences of assessing the RAP assignment. These sessions were approximately one month apart and approximately two hours long. The meetings were audio recorded and transcribed for analysis.

Our reflections were far-ranging, highlighting multiple lessons and conflicts that are beyond the scope of a single paper. In interrogating our responses to marking the assessment, we focused on the difficulties, rather than the strengths of this task, as a way to improve our practice. We concentrated on themes that were emotionally affecting, triggering the most discomfort, and therefore were the most salient and useful lessons to share with colleagues.

Data analysis

An inductive thematic analysis (Clarke & Braun, Citation2017) approach was used to guide our analysis. Authors' (LR, JL and CC's) individual reflections were discussed as we, searched for meaning and the right words to capture core ideas. We then undertook a written response to the themes that resonated most powerfully for us, before the next meeting. On our fourth meeting we refined key themes from the collection of individual reflections and transcripts. The fourth author (JB) was invited to join the team at the final meeting to offer additional criticality and to provide an independent insight into the significance and value of the selected themes ().

Results and discussion: navigating the (Un)settling

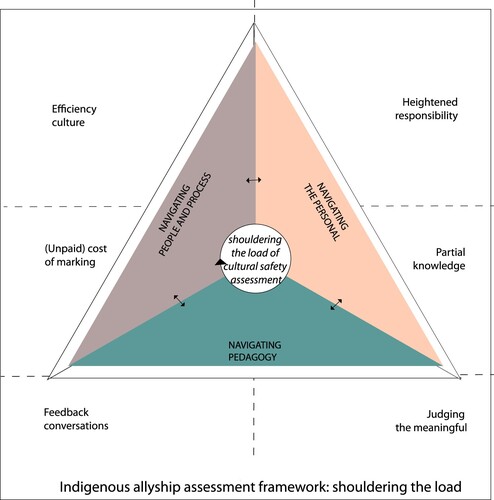

Our central understanding was the need to share the load of cultural safety education so that the burden did not rest exclusively on the shoulders of Indigenous colleagues. Our overarching theme was our shared efforts at Navigating the Unsettling experience of Indigenous allyship in the context of a specific educational practice. We conceptualise the term ‘navigation’ in both Western terms to find your position … and the position you need to go in (Oxford Dictionary, 2022) and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander worldviews, knowledge of the features of the world (Indigenous Knowledge Institute, University of Melbourne, Citation2022). Following the critical reflections, we reached an understanding of the work as a personal journey as assessment markers, navigating personal, pedagogical and systems (retitled as people and processes) barriers, finding out more about our ‘position’ and ‘features’ of the work. Our work can therefore be understood as having three primary themes: (1) Personal, (2) Pedagogical and (3) People and Processes (Systems). Within each primary theme, there are two subthemes: (1) Personal (1.a) Heightened Responsibility and (1b) Partial Knowledge; (2) Pedagogical (2.a) Judging the Meaningful and (2.b) Feedback Conversations; and (3) People and Processes (Systems), (3.a) Efficiency Culture and (b) Cost of marking. From this, we developed a framework () as a means for guiding us in ‘the position we need to go to’. In the three themes (Personal, Pedagogical, People and Processes (Systems)) are depicted within the triangle. It is a triangle to demonstrate the interlinked nature between the three themes. The dotted lines that extend beyond the triangle show the position of the relevant six subthemes. At the Personal Level, we found the Heightened Responsibility and the discomfort of Partial Knowing added to Pedagogical requirements to Judge the Meaningful and Feedback Conversations that influenced as we responded to the People and Processes (Systems) Efficiency Culture and Cost of Marking.

Theme 1: Navigating the personal

Heightened responsibility

As non-Indigenous academics we felt a heightened sense of responsibility for teaching essential content; ensuring learners graduated with cultural safety capabilities. We saw this as not just a professional responsibility, but as a personal one. While the four of us had built friendships around a shared passion for teaching and nurturing learners across a range of subjects (biomedical and psychosocial), we felt strongly that Indigenous health and wellbeing and this assessment needed more from us than other assessment tasks. While this assignment was part of a sequence of learning tasks (), it was the final assignment that engaged with First Nation history and experience, making it feel urgent to get the ‘teaching right’. This felt like the final, formal opportunity for us to shape views and attitudes related to power, privilege and racism, and ultimately to influence student practice capabilities. The urgency seemed entangled in the perceived risks of students’ doing harm if they operated as culturally unsafe clinicians. We recognised this as an overstatement of our own influence, but the weight of responsibility still felt significant and unsettling.

We also felt a responsibility to be more self-sufficient and less dependent on the small number of Indigenous colleagues who carried significant and wide-ranging responsibilities of their own. The tension between repeatedly asking for advice and the risk of not asking and making significant errors was troubling. This created (appropriately) a responsibility to build our own scholarship through more extensive reading and attendance at workshops; a requirement that was difficult to incorporate into our practice due to competing workloads and limited time fractions.

Partial knowledge

An issue we repeatedly discussed was the anxiety we felt at never knowing enough when it came to Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing. It felt like we were experiencing an amplified version of imposter syndrome, at both an intellectual and cultural level. Imposter syndrome has been coined to describe the feeling of intellectual inadequacy experienced by early career academics (Clance & Imes, Citation1978; Wilkinson, Citation2020). We acknowledged that imposter syndrome can become a feature of academic identity, especially for female academics. We debated the legitimacy of our working in this space, and if we were ‘qualified’ to do the task (judging quality and providing feedback) at all. These feelings are consistent with descriptions of inadequacy and self-doubt about the legitimacy of one’s position within academia reported in the literature (Bothello & Roulet, Citation2019).

We grappled with the fact that we were in a learning continuum ourselves regarding First Nation history (past, current and emerging) and knowledges, scholarship, and activism. Student cohorts are not one homogenous group, and we were aware that Indigenous students and non-Indigenous students with more advanced knowledge or experienced allies may be ahead of our own learning journeys. Conversely, we know that there were students who had little to no knowledge, and some who thought that they had no need for this knowledge. We understood that we could not do justice to teaching for culturally safe practice without a wider, deeper reading of literature that is critical, complex, and nuanced and which demands time to fully understand (know what) and translate into practice (also knowing how).

Our discomfort was in finding a balance between a drive to contribute to anti-racist praxis and a competing awareness of our privileged non-Indigenous perspectives. We found the cultural interface we were working in as non-Indigenous educators teaching in the field of Indigenous studies (Nakata, Citation2007) a challenge. As a group, we reflected on the tensions that arise from a conflict between our ‘skill level’ to contribute to the cultural safety dialogue, at the same time as committing to speaking up alongside Indigenous community and maintaining reflexivity in our allyship.

Theme 2: Navigating our pedagogy practice

Judging the meaningful

The emotional labour of judging and decision-making on the quality of reflections was also troubling for all of us. We had been marking this assessment task for four years and were still developing our skills in identifying a good standard of reflection within an assignment limited to 1000 words. We were conscious of the risks of ‘being unfair’ and ‘reinforcing racism’. We struggled with the challenges of discriminating between the authenticity of personal critical reflections and in identifying and responding appropriately to writing that appeared racist. We recalled a past instance when an Indigenous academic had read a couple of assignments and had readily identified racist assumptions that we had missed. This reinforced our concern with not ‘seeing’ problematic attitudes and approaches. We feared not only missing the racist content but inadvertently reinforcing it through good marks. We debated if an individual demonstrating racist attitudes who failed the assignment would benefit from the learning or would feel punished for their personal opinion. Judging what was meaningful and what was meaningless was a key pedagogical skill that needed development. It is one that requires shared learning (briefing of markers) before any marking of assessment tasks for cultural safety commences.

Feedback conversations

Providing feedback and not knowing if the feedback/feedforward we provided was heard by students was also a concern for us. We wanted students to value reflective practice as a way of meaning-making (a core capability for cultural safety practice) as well as to value the content they learned through the assigned task. As experienced markers, we were very aware that response to any ‘constructive’ (code for critical) feedback to students was likely to trigger emotional, potentially angry responses (especially if the marks were low), and could result in resistance, rather than learning (Ryan & Henderson, Citation2018). There may also be inherent resistance to critical reflection, where the deep thinking and exposure of undesirable bias and assumptions could be confronting. Being exposed to teacher’s critical judgments may add to reluctance to engage with reflection for change. In essence, we saw providing feedback for this assessment task as challenging because: (1) it was difficult to find the strengths-based language to provide feedback that was accurate and usable to promote further reflection, especially when we were tired and sensitive (and grumpy) due to poor choices in the students’ reflections, and (2) we had to find time to frame the language in a kind and respectful way that could be heard without causing distress. As is common with most assignments, the more poorly thought out the reflection, the more time we needed to spend providing meaningful feedback that would do no harm (we hoped). We had no idea if students would read and understand our (sometimes) painstakingly written feedback. We wanted our feedback to reframe inappropriate or racist comments in a way that promoted learning but wondered if we were writing monologues that were not heard and had no impact. Was more of us (our work, our time, our anxiety, our discomfort) really producing more for the learner (enabling listening, reflecting, learning and transforming)?

Theme 3: Navigating people and processes (the system)

‘Efficiency’ culture

The tacit and explicit requirement for ‘efficiency’ when marking assignments combined with part-time roles and routines of academic busyness also influenced our experience of this task. We were all used to marking periods as intense interruptions to our professional and personal routines, calling on us to sit still to determine the extent to which learners were able to showcase their learning. Some marking can be done ‘efficiently’ with rapid decision-making on marks and feedback (typically based on concrete marking criteria) with the speedy return of marks to students. The difference in ambition, scope and complexity of this assessment task made following rapid marking routines a challenge for us. We struggled to get the task done in the allocated time. How does one avoid becoming an ‘inefficient’ marker and still do justice to students’ learning? We highlighted this real tension between ideological ambition and institutional pressure.

Cost of marking

The budget for marking also had an impact on how we engaged with the task. In our context, marking by casual tutors is typically budgeted at departmental level on the number of students and the word count of each assignment. In this case, we did not account for the complexity of content and the importance of feedback for patient and practitioner safety outcomes in this funding model. Our conclusion was that not all assignments are created equal in what they ask of markers. In this instance, the standard set payment ratios of minutes per word count did not cover the true cost of time to understand the gaps in understanding, and to provide feedback in meaningful and strengths-based language for all learners, especially for those who needed it most.

Further discussion

This paper explored four non-Indigenous academics' critical reflections of one assessment task on cultural safety practice which resulted in the production of the Indigenous allyship assessment framework: sharing the load, that considers the personal, pedagogical and people and processes (systems) layers that need to be navigated. Incorporating mandatory assessment has been cited as a key curriculum design element academics can employ for driving learning in cultural safety (Forsyth et al., Citation2018), aligning with the ‘assessment for learning’ pedagogical position (Delany et al., Citation2018), which was the impetus for the development of this task. However, we have had to sit with the tension that as non-Indigenous peoples, should we have created an assessment task for learning in cultural safety? What is our place in this academic space? Shaun Wilson (Citation2008), an Opaskwayak Cree man from northern Manitoba, Canada believes that the key is not to focus on who undertakes the work, but on how it is undertaken (Brophy & Raptis, Citation2016, p. 238). It is the how that we sought to explore more deeply through this collaborative autoethnography.

In terms of how, there were three key components that underpinned our approach: relationships, critical reflexivity and developing our comfort with discomfort of never knowing enough. We felt this work would not have been possible without the guidance and support through our established relationships with Indigenous academics and leaders, and non-Indigenous allies. The importance of developing relationships is critical in the literature on Indigenous allyship; also described in some literature as ‘relational accountability’ (Brophy & Raptis, Citation2016; Lewis, Citation2016). In addition to relationships with others, we also benefited from our relationships with each other, and found this collaborative autoethnography process further supported our ‘critical friendship’, as we continue to do better and learn from our mistakes. Secondly, critical reflexivity, viewed as an examination of the assumptions, beliefs and values that underpin established practice and ways of thinking extended into a ‘cultural responsive praxis’ (Lewis, Citation2016, p. 193). Kathleen Aboloson (2011) in (Brophy & Raptis, Citation2016, p. 239) supports that one must deeply get to know themselves: who they are, where they are from and where they receive their learnings/knowledge. Finally, the recognition that we will never know enough was a thread throughout this work for all four of us, highlighted in the framework within partial knowledge and judging the meaningful. We recognise the need for cultural humility as allies, and that the learning and work is always incomplete, never as progressed as it should be or as transformative as we would wish. In exposing our own limitations, we have been (appropriately) humbled by how much further we need to navigate across all three domains of our framework. We felt that our desire to remove the discomfort was perhaps not possible, but rather a move to being comfortable with a level of discomfort is the reality of teaching at the cultural interface (Nakata, Citation2007) aligning with a ‘pedagogy of discomfort’ (Boler, Citation1999), and the capability required of educators teaching Indigenous health and culture to respond to often unfamiliar situations with confidence (Durey et al., Citation2017).

Limitations to our reflections

We recognise the limitations typically identified for collaborative autoethnographies outlined in the methods section. Autoethnography may come under criticism by some academics who do not hold introspection as a valuable means of data generation (Delmont, Citation2006). However, the collective approach is suggested to overcome these criticisms by drawing on multiple sources to provide rich qualitative data (Roy & Uekusa, Citation2020). Burke and Jimenez Soffa (Citation2018) suggest that working collectively is essential to equity practice in order to make time to rethink and reshape the discourses that influence what and how we teach. In this instance, our attempts to meet to reflect during standard academic teaching times were challenging, with discussions spread over months. A decision to spend two days on a reflection and writing retreat allowed us to bring the threads of previously recorded discussions together. While there are some advantages of a distanced and delayed reflection, we may have missed a fresh perspective with more immediate and meaningful lessons that would shape our practices.

We also noted a tendency to focus on the difficulties we were experiencing rather than on the excitement and ‘wins’ of working in this space. The primary theme of ‘struggling to get it right’ throughout this paper risks discouraging non-Indigenous educators from teaching for cultural safety, which is certainly not our intention. We wanted this collaborative autoethnography to push us to think and read more deeply and to inform our future work, and we hope, the future work of our colleagues.

Conclusions and invitations for practice

Our critical reflections through this collaborative autoethnography have allowed us to navigate the past, and through this, develop the Indigenous allyship assessment framework: sharing the load as a useful tool to assist us to navigate the future. We agreed to focus on three themes and six (sub)themes that most informed our practice and were likely to be of value to academics in navigating allyship thought assessment activities in health professional education. We highlight burdens and risks that we were not previously conscious of, but which had impact on us and our practice.

The three main domain areas of navigating the Personal, Professional and People and Processes (systems) have allowed us to identify and describe the 'reality' of our experiences to help us continue to grow as educators and to advocate for more support, funding and resourcing within our institutions. We invite our academic educator colleagues in higher education in other organisations to consider whether our findings resonate with their experiences of assessment for cultural safety practice in work they are currently involved with, or perhaps it may help ‘navigate’ new work in this space.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency. (2020). National Scheme’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Cultural Safety Strategy 2020-2025. https://nacchocommunique.files.wordpress.com/2020/02/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-cultural-health-and-safety-strategy-2020-2025-1.pdf

- Australian Physiotherapy Association. (2017). Reconciliation Action Plan: Innovate 2017-2019. https://australian.physio/sites/default/files/APA_RAP2022_vFweb2.pdf

- Bay, U., & Macfarlane, S. (2011). Teaching critical reflection: A tool for transformative learning in social work? Social Work Education, 30(7), 745–758. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2010.516429

- Blalock, A. E., & Akehi, M. (2018). Collaborative autoethnography as a pathway for transformative learning. Journal of Transformative Education, 16(2), 89–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344617715711

- Boler, M. (1999). Feeling power: Emotions and education (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203009499

- Bolton, J., & Andrews, S. (2018). I learnt more than from any lecture: Indigenous space and place for teaching Indigenous health to physiotherapy students. Physical Therapy Reviews, 23(1), 35–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/10833196.2017.1341744

- Bothello, J., & Roulet, T. (2019). The imposter syndrome, or the mis-representation of self in academic life. Journal of Management Studies, 56(4), 854–861. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12344

- Brophy, A., & Raptis, H. (2016). Preparing to be allies: Narratives of non-Indigenous researchers working in Indigenous contexts. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 62(3), 237–252. https://doi.org/10.55016/ojs/ajer.v62i3.56150

- Bullen, J., & Roberts, L. (2021). Transformative learning within Australian Indigenous studies: A scoping review of non-Indigenous student experiences in tertiary Indigenous studies education. Higher Education Research & Development, 40(1), 162–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1852184

- Burke, P. J., & Jimenez Soffa, S. (2018). The elements of inquiry: Research and methods for a quality dissertation (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351111072

- Carroll, S. M., Bascuñán, D., Sinke, M., & Restoule, J. P. (2020). How discomfort reproduces settler structures: Moving beyond fear and becoming imperfect accomplices. Journal of Curriculum and Teaching, 9(2), 9–19. http://doi.org/10.5430/jct.v9n2p9.

- Chawla, D., & Atay, A. (2018). Introduction: Decolonizing autoethnography. Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, 18(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708617728955

- Clance, P. R., & Imes, S. A. (1978). The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: Dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 15(3), 241–247. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0086006

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 297–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613

- Curtis, E., Jones, R., Tipene-Leach, D., Walker, C., Loring, B., Paine, S. J., & Reid, P. (2019). Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: A literature review and recommended definition. International Journal for Equity in Health, 18(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-019-1082-3

- Delany, C., Doughney, L., Bandler, L., Harms, L., Andrews, S., Nicholson, P., Remedios, L., Edmondson, W., Kosta, L., & Ewen, S. (2018). Exploring learning goals and assessment approaches for Indigenous health education: A qualitative study in Australia and New Zealand. Higher Education, 75(2), 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0137-x

- Delmont, S. (2006). Arguments against Autoethnography European Sociological Association conference; Advances in Qualitative Research Practice, Sept 2006. Issue 4 of Qualitative Researcher (ISSN: 1748-7315).

- Dudgeon, P., & Fielder, J. F. (2006). Third spaces within tertiary places: Indigenous Australian studies. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 16(5), 396–409. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.883

- Durey, A., Taylor, K., Bessarab, D., Kickett, M.n, Jones, S., Hoffman, J., … Scott, K. (2017). ‘Working together’: An intercultural academic leadership programme to build health science educators’ capacity to teach indigenous health and culture. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 46(1), 12–22. http://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2016.15

- Fildes, K., Beck, E., Bur, T., Burns, P., Chisholm, L., Dillon, C., Kuit, T., McMahon, A., Neale, E., Paton-Walsh, C., Powell, S., Skropeta, D., Stefoska-Needham, A., Tomlin, A., Treweek, T., Walton, K., & Kennedy, J. (2021). The first steps on the journey towards curriculum reconciliation in science, medicine and health education. Higher Education Research & Development, 40(1), 194–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1852393

- Fletcher, T., & Bullock, S. M. (2015). Reframing pedagogy while teaching about teaching online: A collaborative self-study. Professional Development in Education, 41(4), 690–706. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2014.938357

- Foely, D. (2021, May 27). The fundamental flaws of Reconciliation Action Plans. LinkedIn https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/fundamental-flaws-reconciliation-action-plans-dean-foley

- Forsyth, C., Irving, M., Short, S., Tennent, M., & Gilroy, J. (2018). Strengthening Indigenous cultural competence in dentistry and oral health education: Academic perspectives. European Journal of Dental Education, 23(1), e37–e44. https://doi.org/10.1111/eje.12398

- Goerke, V. (2019). The idea of Reconciliation in Australian universities and how it has been articulated through Reconciliation Action Plans, A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Monash University.

- Indigenous Knowledge Institute, University of Melbourne. (2022). Navigating our way through country. https://indigenousknowledge.unimelb.edu.au/curriculum/resources/navigating-our-way-through-country

- Krusz, E., Nona, F., Ferguson, M., Charlton, K., Angus, L., Thomas, P., & Fredericks, B. (2022). Toolkit for Embedding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Knowledges in UQ’s School of Public Health Curriculum.

- LaBoskey, V. K. (2004). The methodology of self-study and its theoretical underpinnings. In J. J. Loughran, M. L. Hamilton, V. K. LaBoskey, & T. Russell (Eds.), International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices (pp. 817–869). Springer international handbooks of education, vol 12. Springer.

- Lewis, P. (2016). Indigenous methodologies as a way of social transformation: What does it mean to be an ally? International Review of Qualitative Research, 9(2), 192–194. https://doi.org/10.1525/irqr.2016.9.2.192

- Mackean, T., Fisher, M., Friel, S., & Baum, F. (2020). A framework to assess cultural safety in Australian public policy. Health Promotion International, 35(2), 340–351. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daz011

- Milligan, E., West, R., Saunders, V., Bialocerkowski, A., Creedy, D., Rowe Minniss, F., Kerry Hall, K., & Vervoort, S. (2021). Achieving cultural safety for Australia’s first peoples: A review of the Australian health practitioner regulation agency-registered health practitioners’ codes of conduct and codes of ethics. Australian Health Review, 45(4), 398–406. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH20215

- Nakata, M. (2007). The cultural interface. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 36(S1), 7–14. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1326011100004646

- Ng, S., Wright, S., & Kuper, A. (2019). The divergence and convergence of critical reflection and critical reflexivity: Implications for health professions education. Academic Medicine, 94(8), 1122–1128. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002724

- Nixon, S. A. (2019). The coin model of privilege and critical allyship: Implications for health. BMC Public Health, 19(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7884-9

- Page, S., Trudgett, M., & Bodkin-Andrews, G. (2019). Creating a degree-focused pedagogical framework to guide Indigenous graduate attribute curriculum development. Higher Education, 78(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0324-4

- Papps, E., & Ramsden, I. (1996). Cultural safety in nursing: The New Zealand experience. International Journal for Quality in Health Care : Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care, 8(5), 491–497. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/8.5.491

- Physiotherapy Board of Australia & Physiotherapy Board of New Zealand. (2015). Physiotherapy practice thresholds in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand. https://physiocouncil.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Physiotherapy-Board-Physiotherapy-practice-thresholds-in-Australia-and-Aotearoa-New-Zealand.pdf

- Public Health Indigenous Leadership in Education (PHILE) Network. (2016). National Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander Public Health Curriculum Framework: 2nd Edition, PHILE, Canberra.

- Remedios, L., Andrews, S., Bolton, J., & Clements, T. (2018, February). Using Indigenous knowledges to guide physiotherapy students towards culturally safe practice. The Health Advocate, 46, 32–33.

- Roy, R., & Uekusa, S. (2020). Collaborative autoethnography: ‘Self-reflection’ as a timely alternative research approach during the global pandemic. Qualitative Research Journal, 20(4), 383–392. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-06-2020-0054

- Ryan, T., & Henderson, M. (2018). Feeling feedback: Students’ emotional responses to educator feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(6), 880–892. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2017.1416456

- Sjorberg, D., & Mcdermott, D. (2016). Deconstruction exercise. International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies, 9(1), 28–48. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcis.v9i1.143

- Wilkinson, C. (2020). Imposter syndrome and the accidental academic: An autoethnographic account. International Journal for Academic Development, 25(4), 363–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2020.1762087

- Wilson, S. (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Fernwood.

- Wolfe, N., Sheppard, L., Le Rossignol, P., & Somerset, S. (2017). Uncomfortable curricula? A survey of academic practices and attitudes to delivering Indigenous content in health professional degrees. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(3), 649–662. http://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1385595

- Wood, A. J. (2013). Incorporating Indigenous cultural competency through the broader law curriculum. Legal Educational Review, 23(1), 57–81. https://search.informit.org.doi/10.3316/aeipt.202300.