Abstract

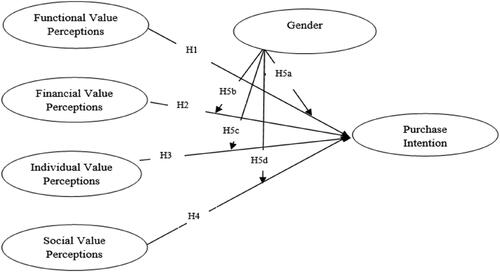

This study aimed to measure the effect of perceived value on purchase intention of luxury goods among Angolan consumers. It also explored the moderating effect of consumer gender. Data were collected through a survey distributed to 130 consumers in North and South Angola, employing Smart-PLS for analysis. The results indicated that perceived social value was the most important determinant of purchase intentions for luxury goods, followed by perceived individual value. The study showed that consumer gender moderated the relationship between and individual value perception and social value perception on purchase intention. The research contributes to the literature, and this study is the first empirical test of a value structure for luxury goods in the Angolan market, so it allowed to better understand the disposition of these consumers in purchase intention according to the perceived value of luxury. Theoretical and practical implications will be discussed.

Introduction

Luxury has accompanied people since the Egyptian age (Godey et al., Citation2013). In antiquity, the word "luxury" began to be addressed in classical works by Virgil or Cicero and in denunciations by religious and moral authorities (Chandon et al., Citation2016). The concept of luxury seems apparent everywhere and is used routinely in our daily lives (Hennigs et al., Citation2013). Luxury as we know it has traditionally been defined as products and services that only a tiny segment of the population can afford or is willing to buy class-oriented exclusivity (Granot et al., Citation2013). Luxury goods are conducive to pleasure and comfort but also challenging to obtain (Chattalas & Shukla, Citation2015).

The consumption of luxury goods involves purchasing a product that represents value to the individual (Wiedmann et al., Citation2009). Zeithaml (Citation1988) defines value as an overall assessment of a product’s or service’s subjective worth, considering all relevant evaluation criteria. A fundamental notion of understanding luxury goods customers’ behavior is perceived value (Timperio et al., Citation2016). The value derived from a product or service is one of the inherent motivators for consumer purchasing decisions (Chattalas & Shukla, Citation2015). Luxury brand value has a significant positive effect on brand purchase intention (Husain et al., Citation2022). However, the danger of doing so without first understanding the perspective of values is critical to choosing the right marketing tool.

Research on luxury value demonstrates that the debate unfolds along four key dimensions: perceptions of social, financial, individual, and functional value (Wiedmann et al., Citation2007; Hennigs et al., Citation2013; Bachmann et al., Citation2019; Klerk et al., Citation2019).

Although these value dimensions operate independently, they interact with each other and influence individual perceptions and behaviors of luxury values that can be used to identify further and segment different types of luxury consumers (Wiedmann et al., Citation2009).

This paper identifies the following gap in the existing literature: A need has been recognized by researchers to empirically investigate models to test the reliability and validity of latent variables in diverse cultural settings (Tsai, Citation2005; Christodoulides et al., Citation2009; Tynan et al., Citation2010; Jain & Mishra, Citation2018). Along with the growing global demand for luxury products, the question arises about the possible differences and similarities in consumers’ perception of luxury value in different parts of the world (Hennigs et al., Citation2013). However, luxury brands’ consumption is evolving in Africa’s emerging markets (Zici et al., Citation2021). The luxury market in the emerging markets of Asia-Pacific, Latin America, the Middle East and Africa accounted for 19% of the global luxury goods market in 2013 and is projected to reach 25% by 2025 (Makhitha, Citation2021).

However, few studies in Africa have sought to understand the effect of value perceptions on the purchase intention of luxury goods, except for studies by Klerk et al. (Citation2019); Makhitha (Citation2021) and Zici et al. (Citation2021) in South Africa. In addition, recent calls by academics point to the need for more marketing research in African regions (Lim et al., Citation2022).

Thus, in this study, the perceived value of a luxury is studied from the perspective of the Angolan consumer. According to Cohen (Citation2019), Angola is one of the five promising countries for luxury brands in sub-Saharan Africa. Angola’s luxury market is most developed in the automotive sector (Canguende-Valentim & Vale, Citation2022). The country has many dollar millionaires who spend lavishly in boutiques in Portugal and Spain (Rice, Citation2013). Angolan consumers prefer the Portuguese luxury market, accounting for 38% of purchases by non-European citizens (Lopes, Citation2021) spending an average of €1,800 on each purchase (Ferreira, Citation2016).

Two previous studies conducted on Angolan consumers were identified, one analyzed the intention to purchase luxury goods based on the theory of planned behavior (Canguende-Valentim & Vale, Citation2022), and the other study analyzed the intention to purchase counterfeit luxury goods based on the theory of perceived risk (Canguende-Valentim, Citation2022). However, so far, no study has been found that investigates the effect of the perceived value of luxury on Angolan consumers’ purchase intention. As a result, what Angolan consumers value in luxury is not known.

Given that value perception plays an essential role in the purchase intention of the luxury consumer (Celik & Erciş, Citation2018). Consumer demographic characteristics can also play an important role in understanding consumers. For example, their gender can affect purchase intentions, so it cannot be ignored. Thus, the aim of this study is twofold: to measure the effect of value perceptions on the purchase intention of luxury goods among Angolan consumers according to the functional, financial, individual and social dimensions of luxury value (Wiedmann et al., Citation2009); and to examine the moderating effect of consumer gender on the relationships between luxury value perception and purchase intention. Structural equation modeling will allow us to identify the magnitude of the impact of value perceptions on purchase intention.

Among the various categories of luxury goods, this research focused on luxury goods in general.

The results of this study will provide guidelines for luxury brand managers targeting the Angolan market and can help develop more effective market-specific strategies. Luxury value is a potent tool used by managers to build their brands’ competitive advantage (Noble & Kumar, Citation2010).

The study used "PLSpredict" to assess the predictive relevance of the study model due to its robustness. PLSpredict is the current predictive relevance technique (Shmueli et al., Citation2019). However, most previous studies seeking to understand the effect of luxury value perceptions on purchase intention have not used this most effective estimator.

This article is structured as follows: The next section presents the literature review and hypothesis development, tracked by the conceptual framework and methodology. The subsequent section describes the findings of the structural and measurement model, followed by the study’s discussion, conclusions, and implications. The last section discusses directions for future research.

Literature review and hypothesis development

Although routinely used daily to refer to products, services or a particular lifestyle, the term "luxury" does not generate a clear understanding (Wiedmann et al., Citation2009). Understanding why consumers buy luxury products, what they perceive and how their perception of luxury affects consumption behavior are the main tasks of luxury companies (Naumova et al., Citation2019). Although the luxury market has significantly expanded in the last decade, information on behaviors and perceptions of the value of a luxury is still lacking (Jung & Shen, Citation2011). Some research has explained that deal includes some critical dimensions, namely functional, financial, personal, and social perceptions (Shukla & Purani, Citation2012; Tynan et al., Citation2010; Vigneron & Johnson, Citation2004; Wiedmann et al., Citation2009). provides relevant studies that capture the range of luxury value perceptions.

Table 1. Some relevant studies on luxury value perceptions.

The need to study perceptions of luxury value in different cultural contexts is suggested by several researchers (Jain & Mishra, Citation2018). Several researchers have conducted studies in the context of China (Li et al., Citation2012; Wu & Yang, Citation2018), Korea (Choo et al., Citation2012), Taiwan (Hung et al., Citation2011), India (Shukla, Citation2012; Shukla & Purani, Citation2012; Sanyal et al., Citation2014; Jain et al., Citation2017; Jain & Mishra, Citation2018), Turkey (Celik & Erciş, Citation2018) and the United States of America and England (Chattalas & Shukla, Citation2015). However, empirical research is deficient from an African country’s luxury market perspective. Few African studies have sought to understand the effect of value perceptions on the intention to purchase luxury goods (Klerk et al., Citation2019; Makhitha, Citation2021; Zici et al., Citation2021).

In a study in South Africa that investigated black consumers’ perceptions of luxury brands, the results reveal that black consumers are most influenced by brands’ rarity and uniqueness, followed by brands’ financial and functional values (Makhitha, Citation2021).

In another study in South Africa, the authors tested the predictive role of culture and the mediating effect of individual values and value expressiveness in explaining luxury purchase intentions. The results indicated that higher-order cultural values - individualism and collectivism have a predictive influence on personal level values, self-enhancement, and materialism, which affect luxury brands ‘value expressiveness to predict luxury purchase intentions (Zici et al., Citation2021).

Regarding Angola, two studies conducted on luxury consumers were identified. One of the studies analyzed the intention to purchase luxury goods based on the planned behavior theory (Canguende-Valentim & Vale, Citation2022). The study revealed that attitude and subjective norms are the main factors in the intention to purchase luxury goods. Another study analyzed the intention to purchase counterfeit luxury goods based on the theory of perceived risk (Canguende-Valentim, Citation2022). The study revealed that the perception of social risk positively affects the attitude toward counterfeit luxury goods. Overall, the studies reported the strong impact of the social factor on luxury consumption among Angolan consumers.

However, no study investigated the effect of perceived luxury value on Angolan consumers’ purchase intention. This study aims to fill this gap, studying the impact of luxury value perceptions on purchase intention from the Angolan consumer’s perspective, which reinforces the importance of this study.

Overall, the empirical findings support the view that social, personal and functional value perceptions play essential roles in consumers’ luxury purchase intentions in both leading, highly developed luxury markets (Chattalas & Shukla, Citation2015).

In the following subsections, we advance hypotheses about the effect of the four underlying dimensions of functional, financial, individual, and social value perception (Wiedmann et al., Citation2009) on luxury purchase intentions.

Functional value perception

Functional value refers to the extent to which a product (good or service) has the desired characteristics, is useful or performs the desired function (Tynan et al., Citation2010). Functional value focuses on product aspects such as quality, specificity, usability, reliability, durability (Hennigs et al., Citation2013; Chattalas & Shukla, Citation2015) and uniqueness (Shukla, Citation2012; Wiedmann et al., Citation2009). Consumers expect a luxury product to be usable, of good quality and exclusive enough to satisfy their desire to differentiate themselves (Wiedmann et al., Citation2009). Therefore, each product is designed to perform specific functions to meet consumer needs (Chattalas & Shukla, Citation2015).

Thus, functional value can increase purchase intention among luxury consumers (Shukla & Purani, Citation2012). Furthermore, perceptions of functional value significantly predict luxury purchase intentions in several previous studies (Chattalas & Shukla, Citation2015; Celik & Erciş, Citation2018; Makhitha, Citation2021).

In the context of this research, the functional value may increase purchase intention among Angolan consumers; therefore, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H1. Perceived functional value positively affects Angolan consumers’ purchase intentions toward luxury products.

Financial value perception

The perception of financial value refers to monetary aspects, such as price, resale cost, discount, and investment (Hennigs et al., Citation2013). Although luxury consumers are willing to pay premium prices for luxury products, they still try to maximize benefits and minimize costs (Wu & Yang, Citation2018). A higher acquisition cost elevates the exclusivity and convenience of the luxury brand (Shukla & Purani, Citation2012).

Consumers use high prices to infer product quality and signal social status, and they also expect to get efficient value from luxury items in return (Shukla & Purani, Citation2012).

However, it is essential to realize that a product or service does not need to be expensive to be a luxury good, nor is it luxurious just because of its price (Wiedmann et al., Citation2009). Thus, the financial value may increase purchase intention among luxury consumers, as perceptions of financial value are a significant predictor of luxury purchase intentions in several studies (Shukla, Citation2012; Yang & Mattila, Citation2015; Wu & Yang, Citation2018; Makhitha, Citation2021).

In the context of this research, financial value can increase purchase intention among Angolan consumers; therefore, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H2. Perception of financial value has a positive effect on Angolan consumers’ purchase intentions towards luxury products.

Individual value perception

Based on the customer’s personal orientation toward luxury consumption, individual value perception refers to personal issues such as materialism, hedonism, and self-identity (Hennigs et al., Citation2013).

Personally motivated consumers focus on hedonistic values and self-awareness rather than other consumption expectations (Shukla, Citation2012; Tsai, Citation2005).

Luxury consumption is increasingly being used for self-directed pleasure and not just for the social motive of buying to impress others (Chattalas & Shukla, Citation2015). Thus, the perceived personal value may increase purchase intention among luxury consumers, as perceptions of personal value are a significant predictor of luxury purchase intentions in several studies (Shukla & Purani, Citation2012; Celik & Erciş, Citation2018).

In the context of this research, the perceived individual value may increase purchase intention among Angolan consumers; therefore, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H3. Individual value perception positively affects Angolan consumers’ purchase intentions toward luxury products.

Social value perception

The concept of social value orientation is rooted in research focusing on cooperation and competition (Chattalas & Shukla, Citation2015). Perceived social value refers to aspects such as conspicuousness and prestige and focuses on the perceived usefulness that individuals acquire from products or services recognized within social groups (Hennigs et al., Citation2013).

Social value perceptions are largely outward-directed consumption preferences related to the instrumental aspect of impression management (Shukla, Citation2012). Thus, a luxury brand associated with conspicuous signage may be highly preferred by consumers (Shukla, Citation2012).

The meaning of products is important to consumers and their social group members, and therefore, consumers generally buy products according to what they mean to them and their social reference groups (Chattalas & Shukla, Citation2015; Wiedmann et al., Citation2009), where the reference group has effects on conspicuous consumption of a product (Wiedmann et al., Citation2007). In today’s digital age, with global media (online and offline) and its increasing presence, individuals are constantly exposed to various situations that trigger social comparisons with friends, peers, consumer groups, brand communities and celebrities that subsequently influence their purchasing behavior, both offline and online (Pillai & Nair, Citation2021).

Consumers often purchase products according to what they mean to them and members of their social reference groups (Wiedmann et al., Citation2007, Citation2009; Tynan et al., Citation2010). Therefore, if consuming luxury goods is considered socially appropriate, consumers may adopt such behavior to conform to social standards (Chattalas & Shukla, Citation2015).

Many motivational forces affect consumer behavior in buying and consuming goods. For example, one of the most important motivations for consumers to purchase and consume is to gain status or social prestige (Chattalas & Shukla, Citation2015). Thus, perceived social value may increase purchase intention among luxury consumers, as perceptions of social value are a significant predictor of luxury purchase intentions in several studies (Hung et al., Citation2011; Shukla, Citation2012; Chattalas & Shukla, Citation2015; Celik & Erciş, Citation2018; Jain & Mishra, Citation2018).

In the context of this research, the perceived social value may increase purchase intention among Angolan consumers; therefore, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H4. Perceived social value positively affects Angolan consumers’ purchase intentions toward luxury products.

Moderating effect of consumer gender

Previous research has explored the moderating effects of consumer demographic characteristics such as gender, age, education level, marital status, and income level (Rid et al., Citation2014; Kim & Jang, Citation2017; Hwang & Lyu, Citation2018). For example, Hwang and Lyu (Citation2018) examined significant differences in luxury value based on the demographic characteristics of first-class passengers.

Gender is often identified as a variable representing different consumption styles and personal goals (Husain et al., Citation2022).

Therefore, the following hypotheses were formulated to capture the potential moderating role of gender in the different constructs of interest explored in the present study:

H5a. Consumer gender moderates the relationship between perceived functional value and luxury purchase intention.

H5b. Consumer gender moderates the relationship between perceived financial value and luxury purchase intention.

H5c. Consumer gender moderates the relationship between individual value perception and luxury purchase intention.

H5d. Consumer gender moderates the relationship between social value perception and luxury purchase intention.

Methodology

To investigate the effect of perceived value on luxury purchase intentions, we focus on the four underlying dimensions of value, namely financial, functional, individual, and social (Wiedmann et al., Citation2007, Citation2009), which were selected as the context of the Angola study. The convenience sampling method was adopted. Data collection was conducted in April and May 2021. Respondents were contacted in the region of North and South Angola through an online questionnaire (we provided a brief explanation of the concept of luxury based on Godey et al. (Citation2013)).

As suggested by previous researchers (Shukla, Citation2010, Citation2011; Jain, Citation2020), a qualifying question was included in the first section. All respondents were asked to mention the names of luxury brands they purchased. The rationale behind this question was to ensure that data is collected only from actual users of luxury brands (Jain & Mishra, Citation2018). In this study no particular luxury product was specified, the research focused on luxury goods generally.

In total, 153 questionnaires were answered, of which 130 were valid and included for analysis, according to .

Table 2. Survey respondents’ profiles (n = 130).

Scale development

The existing literature used established and validated scales to measure the effect of the dimensions of luxury value perception and purchase intention. The dimensions of luxury value (Hennigs et al., Citation2012) were used for perceived financial value, individual value and social value. The items of the functional perceived value scale were derived from (Shukla, Citation2012), and the purchase intention scale items were adapted from Wang et al. (Citation2005) and Bian and Forsythe (Citation2012). All items were measured on a five-point Likert scale, where "1" denoted "strongly disagree" and "5" indicated "strongly agree".

Data analysis

To achieve the objective of this study and test the hypotheses, the Smart PLS 3.3.3 program was used to perform structural equation modeling. The parameters were estimated using the partial least squares method. The moderating effect of gender was tested by PLS-SEM MGA, with results presented in . Structural equation modeling (SEM) is considered one of the best techniques to evaluate hypothetical relationships in a complex project (Hair et al., Citation2016). The ability to analyze observed and latent variables distinguishes SEM from more standard statistical techniques, such as analysis of variance (ANOVA) and multiple regression, which analyze only observed variables (Kline, Citation2016). According to Reinartz et al. (Citation2009), our sample (n = 130) is small, and the application of PLS-SEM is justified when the number of observations is less than 250 (Kurt et al., Citation2016).

Results

First, we report the results of the evaluation of the measurement model to assess the reliability of the indicators, reliability of the constructs, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Next, we provide the results after testing the proposed structural model.

Measurement model

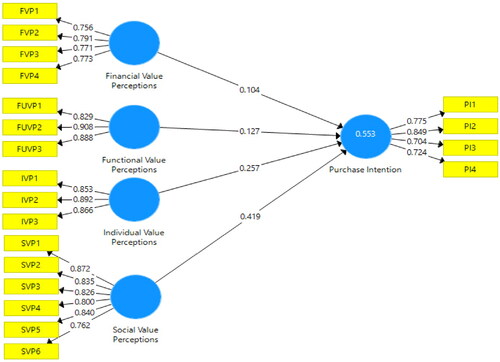

The first step in assessing the outcomes of PLS-SEM involves examining the measurement models (Hair et al., Citation2019). First, the indicator loadings were examined. Loadings above 0,7 are recommended, as they indicate that the construct explains more than 50 per cent of the variance of the indicator, providing acceptable item reliability (Hair et al., Citation2010). Twenty items were finally accepted after excluding the items (IVP4, IVP5, IVP6 and IVP7) with factor loadings below the recommended one. However, the factor loadings of all the observed variables included were higher than the recommended level, as shown in .

The second stage assessed the reliability of the internal consistency of the constructs. We evaluated the consistency of the constructs using Cronbach’s alpha, Dijkstra-Henseler’s individual reliability assessment (rho_A), and composite reliability (CR). These values help assess a construct’s consistency based on its indicators (Götz et al., Citation2010). The lower limit established for acceptance of construct consistency and reliability is generally between 0,6 and 0,7 (Hair et al., Citation2010). shows that all variables exceeded the minimum values for acceptance, and all constructs had Cronbach’s alpha, Dijkstra-Henseler rho and CR values greater than 0,7; they are considered reliable (Henseler et al., Citation2009).

The third stage of the measurement model assessment addresses the convergent validity of each construct measure. Convergent validity is the extent to which the construct converges to explain the variance of its items (Hair et al., Citation2019). The metric used to assess the convergent validity of a construct is the average variance extracted (AVE) for all items in each construct. The AVE value gives convergent validity, which must be at least 0,5 to be considered sufficient and explain, on average, more than half of the variance of the indicators (Henseler et al., Citation2009). shows that the AVE values for all constructs were above 0,5, indicating convergent validity in all cases.

Table 3. Factor loadings and indicators of internal consistency and reliability.

In the fourth stage, discriminant validity was assessed. Discriminant validity represents the extent to which a construct is empirically distinct from other constructs in the structural model. The study used the Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) criterion. As recommended by Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981), all constructs met the discriminant validity because the correlation coefficients were much smaller than the square roots of the AVE for the individual variables, supporting the good discriminant validity of the constructs in this study as shown in .

Table 4. Discriminant validity.

To evaluate the fit of the proposed model, the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) was calculated (Henseler et al., Citation2016). SRMR measures the difference between the observed correlation matrix and the correlation matrix implied by the model. Hu and Bentler (Citation1999) argue that a model fits well when SRMR is less than 0,08. In this study, the SRMR value was 0,069, indicating a good model fit.

The next step in evaluating the results of PLS-SEM is to evaluate the structural model (Hair et al., Citation2019).

Structural model

After checking the reliability and validity of the measurement model, the proposed structural model is examined. The model’s explanatory power is assessed using R square and Q square (Hair et al., Citation2019). O R2 ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater explanatory power (Hair et al., Citation2019). Falk and Miller (Citation1992) state that R2 values below 0,1 mean that the relationships formulated with the hypotheses have low explanatory power, although they may be statistically significant. The results of this study show that the structural model explained 55,3% of the total variance between FUP, FVP, IVP and SVP for PI.

Chin et al. (Citation2008) state that Q2 is the predictive sample reuse technique, it is evaluated along with both R,2 and they effectively present the predictive relevance of the model. Q2 is generated through a blindfold technique and reveals the usefulness of the data in terms of reassembling it in practice using the study model and PLS features; therefore, redundancy measures with cross-validation. According to Chin et al. (Citation2008), when the value of Q2 is greater than zero (0), the model is classified as having high predictive power. So, the value of Q2 = 0,509 shown in proposes that the study model has high predictive power.

Table 5. Predictive relevance.

Collinearity was examined to ensure that it does not influence the regression results (Hair et al., Citation2019). Multicollinearity was assessed by examining the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values. VIF values should be close to 3 and lower (Hair et al., Citation2019). This study showed no severe multicollinearity, as illustrated in .

Table 6. Structural model evaluation.

The statistical significance and relevance of the path coefficients were assessed. It analyzed the hypotheses for purchase intention. Of the four constructs predicted to influence purchase intention for luxury goods, the results showed that neither Functional Value Perceptions (H1: β = 0,127 and p = 0,185) or Financial Value Perceptions (H2: β = 0,104 and p = 0,132) was supported. However, Individual Value Perceptions (H3: β = 0,257 and p = 0,002) and Social Value Perceptions (H4: β = 0,419 and p = 0,000), were supported, with a 99% confidence interval, as shown in .

Table 7. Model resolution using PLS algorithm and bootstrapping.

Following the guidelines by Shmueli et al. (Citation2019), the PLS prediction of the model was evaluated. The PLS prediction indicates a highly symmetric distribution in prediction errors when the Q2 values are greater than zero (0). illustrates that the Q2 predictive value is greater than zero, suggesting that the PLS-RMSE values should be compared with the LM RMSE (Shmueli et al., Citation2019). After comparison, we noticed that PLS-SEM analysis produced a lower prediction error for all indicators as seen in PI1, PI2, PI3 and PI4 with 0,682, 0,860, 0,828 and 0,928, respectively. In contrast, LM (Linear Model) produced RMSE values of 0,717, 0,918, 0,879 and 0,955 respectively for the model estimation using PLS-RMSE. Thus, the negative values obtained in , after deducing the PLS-RMSE values from the LM-RMSE values, indicated a high predictive power of the model (Hair et al., Citation2019; Shmueli et al., Citation2019).

Table 9. Moderation analysis on gender.

Table 8. PLS Assessment of Manifest Variable (Original Model).

The moderating effect of gender was tested as part of the proposed research model, with the results presented in the following table. Two of the four hypotheses tested were supported, namely H5c (β = 0,488 and p < 0,01) and H5d (β = 0,614 and p < 0,01).

Discussion

This study empirically tested the effect of functional, financial, individual, and social value perception on luxury purchase intentions in the Angolan context. It also examined the moderating role of gender in the relationship between the perceived value of luxury and purchase intention. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first study that verifies the theoretical framework of luxury value perception from the perspective of the Angolan market. The results demonstrate the importance of this model in understanding the behavior of the Angolan luxury consumer.

The present research results indicate that perceived social value is the most important predictor of purchase intention, with perceived social value having a more significant impact on purchase intentions. The prediction that perceived social value would influence purchase intention for luxury goods (H4) was supported with a 99% confidence level. Our findings are consistent with results from previous studies (Sanyal et al., Citation2014; Chattalas & Shukla, Citation2015; Celik & Erciş, Citation2018; Jain & Mishra, Citation2018). Furthermore, this social component has greater relevance in our model, as our result for this construct had a higher impact (β = 0.419) than (β = 0.311) in Celik and Erciş (Citation2018) in Turkey. This result reveals that Angolans use luxury as a status symbol to demonstrate their achievements to others.

Social influence on individuals’ purchasing behavior is less influential in individualistic cultures compared to collectivistic cultures (Gentina et al., Citation2018). Angola is considered a collectivist society (Hofstede, Citation2020). According to Shukla and Purani (Citation2012), there seems to be a correlation between the cultural dimension of individualism/collectivism and different perceptions of luxury values.

The prediction that individual value perception (H3) would influence the intention to purchase luxury goods was supported. The finding shows that individual value perception influences the purchase intentions of Angolan consumers. It was found to be the second most significant factor. A similar result was found in several studies (Wong & Ahuvia, Citation1998; Chattalas & Shukla, Citation2015; Celik & Erciş, Citation2018).

Furthermore, we predicted that perceived functional value (H1) and perceived financial value (H2) would influence the intention to purchase luxury goods. However, we found no support for these predictions. A similar result was found in the study by Reyes-Menendez et al. (Citation2022) in Spain. Yu et al. (Citation2018) report that luxury products’ financial and functional characteristics are not as important for luxury brand perception as they were in the original models. Thus, when luxury products are purchased, economic motivation or pragmatic considerations are no longer important (Reyes-Menendez et al., Citation2022). In Makhitha (Citation2021) study in South Africa, support for perceived functional and financial value was found. Like Angola, South Africa is also located in sub-Saharan Africa.

Furthermore, the moderating role of gender was present in the relationship between individual value perception and social value perception on luxury purchase intention; however, hypotheses H5c and H5d were supported. The moderating role of gender was present in the relationship between individual value perception and luxury purchase intention (βdiff = 0,422 and p = 0,01), this was significant for female (β = 0,488 and p < 0,01) but not for male (β = 0,066 and p > 0,01). These findings indicate that female luxury consumers seem more prone to individual value perception in luxury purchase intention. On the other hand, gender also moderated the relationship between social value perception and luxury purchase intention (βdiff = −0,437 and p = 0,028), this was significant for male gender (β = 0,614 and p < 0,01), but not for female gender (β = 0,177 and p > 0,01). These findings indicate that male luxury consumers appear likelier to perceive social value in luxury purchase intention.

Conclusions and implications

This study aimed to empirically measure the effect of multiple dimensions of luxury value perception on purchase intentions in the Angolan market context. In addition, the study also explored the moderating effect of consumer gender on the relationship between perceived value and purchase intention.

This study revealed that perceived social value and perceived individual value are the main factors in the purchase intention of luxury goods. Perceived social value impacts purchase intentions more than perceived individual value.

This study further revealed that perceived functional value and perceived financial value are not factors in the purchase intention of luxury goods.

On the other hand, gender played a moderating role in the relationship between individual and social value perception on luxury purchase intention, respectively. Our findings have important theoretical and practical implications.

Theoretical implications

This study has developed a conceptual framework that can help us understand the effect of luxury value perception on purchase intentions in the context of the Angolan market. Examining this relationship allows us to understand consumers’ purchase intention disposition better.

This study contributes to the academic literature in several ways. First, given that little is known about Angolan luxury consumers, except that Canguende-Valentim (Citation2022) reported in his study that the perception of social risk has a positive relationship on attitude toward counterfeit luxury products for these consumers because the Marketing literature points to a negative relationship between perceived social risk and attitude. This study attempts to continue the dialogue with these consumers to reveal their perception of the value of luxury. Firstly, this research contributes to the literature by highlighting that perceived social value and perceived individual value significantly influence consumers’ purchase decision of luxury products. In the Angolan context, these results are in line with the studies of Jain and Mishra (Citation2018) in India and Jiang and Shan (Citation2018) in China, where conspicuous value (social value), hedonic value (individual value) were also the predictors in purchase intention among Indian and Chinese luxury consumers.

This result reaffirms that in collectivist societies like India, China and Angola, consumers purchase luxury brands to convey their social status and prestige. Furthermore, consumers from collectivist cultures are more willing to purchase luxury brands as they are more likely to engage in social comparisons (Pillai & Nair, Citation2021).

Secondly, the current study supports Eckhardt et al. (Citation2015) and Klerk et al. (Citation2019) results regarding individual value perception referring that people buy luxury goods to show their personal preferences and seek pleasure rather than to symbolize wealth.

Third, the current study supports the result of Reyes-Menendez et al. (Citation2022), indicating that functional and financial value may not be significant predictors of luxury goods consumption.

On the other hand, a different result was found in Klerk et al. (Citation2019) and Makhitha (Citation2021) studies in South Africa, where perceived financial value and perceived functional value were significant predictors of the intention to purchase luxury goods.

Regarding functional value perception, the result of this study contrasts with the study of Jiang and Shan (Citation2018) in China and Klerk et al. (Citation2019) in South Africa, where functional values were significant predictors in luxury purchase intention for Chinese and South African consumers respectively.

When comparing gender, the perception of individual value is significant for women, while the perception of social value is significant for men.

Practical implications

Based on the findings of this study, understanding the impact of perceived social value and perceived individual value on purchase intention would help companies formulate better marketing strategies to position their luxury brand in Angola and communicate with target consumers. Marketers need to focus on the social significance of their products and share how their products can benefit consumers in a way that reflects their social status in society (Salem & Salem, Citation2018).

However, companies can promote digital and social media campaigns that drive target audiences to compare themselves with socially prominent benchmarks. Such comparisons are expected to encourage purchase luxury intentions directly in collectivist countries, as they are more influenced by social pressures to maintain and improve their social position (Pillai & Nair, Citation2021).

Furthermore, the impact of individual value perceptions has significant strategic implications for luxury brand managers. It can give managers a distinct positional advantage in the consumer’s mind and create an opportunity for differentiation (Chattalas & Shukla, Citation2015).

Although our results suggest that functional and financial value may not be significant key drivers of luxury goods consumption in Angola, we want to emphasize that the results do not imply that these two dimensions of value are entirely ignored.

Marketers of luxury brands can segment female luxury buyers with aspects of individual value perception and male luxury buyers with elements of social value perception.

Limitations and direction for future research

It is necessary to consider some limitations of the study. Firstly, this study focused only on luxury goods. However, further research in this context could also focus on luxury services. Second, this study’s results indicate a weak relationship between financial value and purchase intention, as well as functional value and purchase intention. Future studies in this domain need to reevaluate these findings, considering larger samples than this study. Third, a cross-cultural study at African country level would be fascinating as this study found a different result from Makhitha (Citation2021) study in South Africa. Fourth, it will be potentially fruitful to investigate whether there are intergenerational differences in emphasis between consumer values in luxury products across different ethnicities (Lim et al., Citation2022).

References

- Bachmann, F., Walsh, G., & Hammes, E. K. (2019). Consumer perceptions of luxury brands: An owner-based perspective. European Management Journal, 37(3), 287–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2018.06.010

- Berthon, P., Pitt, L., Parent, M., & Berthon, J. P. (2009). Aesthetics and ephemerality: Observing and preserving the luxury brand. California Management Review, 52(1), 45–66. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2009.52.1.45

- Bian, Q., & Forsythe, S. (2012). Purchase intention for luxury brands: A cross cultural comparison. Journal of Business Research, 65(10), 1443–1451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.010

- Canguende-Valentim, C. F. (2022). Determining consumer purchase intention toward counterfeit luxury goods based on the perceived risk theory. In Handbook of Research on New Challenges and Global Outlooks in Financial Risk Management (pp. 316–339). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-8609-9.ch015

- Canguende-Valentim, C. F., & Vale, V. T. (2022). Examining the intention to purchase luxury goods based on the planned behaviour theory. Open Journal of Business and Management, 10(01), 192–210. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojbm.2022.101012

- Celik, B., & Erciş, A. (2018). Impact of value perceptions on luxury purchase intentions: moderating role of consumer knowledge [Paper presentation].4th Global Business Research Congress, May 24–25, 2018, September. https://doi.org/10.17261/Pressacademia.2018.855

- Chandon, J., Laurent, G., & Valette-Florence, P. (2016). Pursuing the concept of luxury: Introduction to the JBR Special Issue on “Luxury Marketing from Tradition to Innovation”. Journal of Business Research, 69(1), 299–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.08.001

- Chattalas, M., & Shukla, P. (2015). Impact of value perceptions on luxury purchase intentions: A developed market comparison Paurav Shukla. Luxury Research J, 1(1), 40–57. https://doi.org/10.1504/LRJ.2015.069806

- Chin, W. W., Peterson, R. A., & Brown, S. P. (2008). Structural equation modeling in marketing: Some practical reminders. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 16(4), 287–298. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679160402

- Choo, Choo, H. J., Moon, H., Kim, H., & Yoon, N. (2012). Luxury customer value. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 16(1), 81–101, https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/13612021211203041/full/pdf?title=luxury-customer-value.

- Christodoulides, G., Michaelidou, N., & Li, C. H. (2009). Measuring perceived brand luxury: An evaluation of the BLI scale. Journal of Brand Management, 16(5-6), 395–405. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2008.49

- Cohen, T. (2019). Africa: The luxury market of the future? Cpp Luxury. https://cpp-luxury.com/africa-the-luxury-market-of-the-future/

- Eckhardt, G. M., Belk, R. W., & Wilson, J. A. (2015). The rise of inconspicuous consumption. Journal of Marketing Management, 31(7–8), 807–826. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2014.989890

- Falk, R. F., & Miller, N. B. (1992). A primer for soft modeling. In A primer for soft modeling. University of Akron Press.

- Ferreira, D. (2016). Luxury. This market “Worth 10 Thousand Ronaldos”. Live Money. https://www.dinheirovivo.pt/economia/luxo-este-mercado-vale-10-mil-ronaldos

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

- Gentina, E., Huarng, K. H., & Sakashita, M. (2018). A social comparison theory approach to mothers' and daughters' clothing co-consumption behaviors: A cross-cultural study in France and Japan. Journal of Business Research, 89, 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.12.032

- Godey, B., Pederzoli, D., Aiello, G., Donvito, R., Wiedmann, K., & Hennigs, N. (2013). A cross-cultural exploratory content analysis of the perception of luxury from six countries. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 22(3), 229–237. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-02-2013-0254

- Götz, O., Liehr-Gobbers, K., & Krafft, M. (2010). Evaluation of structural equation models using the partial least squares (PLS) approach. In Handbook of partial least squares (pp. 691–711). Springer.

- Granot, E., Russell, L., T., M., & Brashear-Alejandro, T. G. (2013). Populence exploring luxury for the masses. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 21(1), 31–44. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679210102

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (P. P. Hall, Ed., 7th ed).

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Publications, Sage.

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hennigs, N., Wiedmann, K., & Christiane, K. (2013). Consumer value perception of luxury goods: A cross-cultural and cross-industry comparison. 77–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-8349-4399-6, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-8349-4399-6_5

- Hennigs, N., Wiedmann, K., Klarmann, C., Godey, B., Pederzoli, D., Janka, T., & Rodr, C. (2012). What is the value of luxury ? A cross-cultural consumer perspective. Psycholgy and Marketing, 29(December), 1018–1034. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/mar.20583

- Hennigs, N., Wiedmann, K., Schmidt, S., Langner, S., & Wüstefeld, T. (2013). Managing the value of luxury: The effect of brand luxury perception on brand strength. 341–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-8349-4399-6, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-8349-4399-6_19

- Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(1), 2–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New challenges to international marketing. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1474-7979(2009)0000020014

- Hofstede, G. (2020). Hofstede-insights. Hofstede-Insights.

- Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hung, K., Huiling Chen, A., Peng, N., Hackley, C., Amy Tiwsakul, R., & Chou, C. (2011). Antecedents of luxury brand purchase intention. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 20(6), 457–467. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610421111166603

- Husain, R., Ahmad, A., & Khan, B. M. (2022). The role of status consumption and brand equity: A comparative study of the marketing of Indian luxury brands by traditional and social-media. Global Business and Organizational Excellence, 41(4), 48–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/joe.22156

- Hwang, J., & Lyu, S. (2018). Understanding first-class passengers' luxury value perceptions in the US airline industry. Tourism Management Perspectives, 28(March), 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2018.07.001

- Jain, S. (2020). Assessing the moderating effect of A subjective norm on luxury purchase intention: A study of Gen Y consumers in India. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 48(5), 517–536. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-02-2019-0042

- Jain, S., Khan, M. N., & Mishra, S. (2017). Understanding consumer behavior regarding luxury fashion goods in India based on the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 11(1), 4–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/JABS-08-2015-0118

- Jain, S., & Mishra, S. (2018). Effect of value perceptions on luxury purchase intentions: An Indian market perspective. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 28(4), 414–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2018.1490332

- Jiang, L., & Shan, J. (2018). Heterogeneity of luxury value perception: A generational comparison in China. International Marketing Review, 35(3), 458–474. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-12-2015-0271

- Jung, J., & Shen, D. (2011). Brand equity of luxury fashion brands among Chinese and U. S. young female consumers. Journal of East-West Business, 17(1), 48–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/10669868.2011.598756

- Kim, D., & Jang, S. (. (2017). Symbolic consumption in upscale cafés: Examining Korean Gen Y consumers' materialism, conformity, conspicuous tendencies, and functional qualities. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 41(2), 154–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348014525633

- Klerk, H., Kearns, M., & Redwood, M. (2019). Controversial fashion, ethical concerns and environmentally significant behaviour: The case of the leather industry. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 47(1), 19–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-05-2017-0106

- Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practices of structural equation modelling. In Methodology in the social sciences (4th ed.). Guilford Press.

- Kurt, Y., Yamin, M., Sinkovics, N., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2016). Spirituality as an antecedent of trust and network commitment: The case of Anatolian Tigers. European Management Journal, 34(6), 686–700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2016.06.011

- Li, G., Li, G., & Kambele, Z. (2012). Luxury fashion brand consumers in China: Perceived value, fashion lifestyle, and willingness to pay. Journal of Business Research, 65(10), 1516–1522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.019

- Lim, W. M., Kumar, S., Pandey, N., Rasul, T., & Gaur, V. (2022). From direct marketing to interactive marketing: A retrospective review of the Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-11-2021-0276, https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JRIM-11-2021-0276/full/pdf?title=from-direct-marketing-to-interactive-marketing-a-retrospective-review-of-the-italicjournal-of-research-in-interactive-marketingitalic

- Lim, W. M., Ting, D. H., Khoo, P. T., & Wong, W. Y. (2012). Understanding consumer values and socialization – A case of luxury products. Management & Marketing Challenges for the Knowledge Society, 7(2), 209–220.

- Lopes, M. (2021). Estratégias de marketing para a internacionalização de marcas de moda de luxo portuguesas. Universidade Lusófona de Humanidades e Tecnologias.

- Makhitha, K. M. (2021). Research in business & social science black consumers perceptions towards luxury brands in South Africa. International Journal of Research in Business & Social Science, 10(4), 28–36.

- Naumova, O., Bilan, S., & Naumova, M. (2019). Luxury consumers' behavior: A cross-cultural aspect. Innovative Marketing, 15(4), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.21511/im.15(4).2019.01

- Noble, C. H., & Kumar, M. (2010). Exploring the appeal of product design: A grounded, value‐based model of key design elements and relationships. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 27(5), 640–657. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5885.2010.00742.x

- Park, M., Im, H., & Kim, H. Y. (2020). “You are too friendly!” The negative effects of social media marketing on value perceptions of luxury fashion brands. Journal of Business Research, 117, 529–542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.026

- Pillai, K. G., & Nair, S. R. (2021). The effect of social comparison orientation on luxury purchase intentions. Journal of Business Research, 134(January 2020), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.05.033

- Reinartz, W., Haenlein, M., & Henseler, J. (2009). An empirical comparison of the efficacy of covariance-based and variance-based SEM. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 24(6), 332–344.

- Reyes-Menendez, A., Palos-Sanchez, P., Saura, J. R., & Santos, C. R. (2022). Revisiting the impact of perceived social value on consumer behavior toward luxury brands. European Management Journal, 40(2), 224–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2021.06.006

- Rice, X. (2013). Africa's wealthy revel in luxury labels. https://www.ft.com/content/e61f123c-8713-11e2-bde6-00144feabdc0

- Rid, W., Ezeuduji, I. O., & Pröbstl-Haider, U. (2014). Segmentation by motivation for rural tourism activities in The Gambia. Tourism Management, 40, 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.05.006

- Roux, E., Tafani, E., & Vigneron, F. (2017). Values associated with luxury brand consumption and the role of gender. Journal of Business Research, 71, 102–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.10.012

- Salem, S. F., & Salem, S. O. (2018). Self-identity and social identity as drivers of consumers' purchase intention towards luxury fashion goods and willingness to pay premium price. Asian Academy of Management Journal, 23(2), 161–184. https://doi.org/10.21315/aamj2018.23.2.8

- Sanyal, S. N., Datta, S. K., & Banerjee, A. K. (2014). Attitude of Indian consumers towards luxury brand purchase: An application of 'attitude scale to luxury items'. International Journal of Indian Culture and Business Management, 23, 161–184.

- Shmueli, G., Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Cheah, J.-H., Ting, H., Vaithilingam, S., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using PLSpredict. European Journal of Marketing, 53(11), 2322–2347. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-02-2019-0189

- Shukla, P. (2010). Status consumption in cross‐national context: Socio‐psychological, brand and situational antecedents. International Marketing Review, 27(1), 108–129. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651331011020429

- Shukla, P. (2011). Impact of interpersonal influences, brand origin and brand image on luxury purchase intentions: Measuring interfunctional interactions and a cross-national comparison. Journal of World Business, 46(2), 242–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2010.11.002

- Shukla, P. (2012). The influence of value perceptions on luxury purchase intentions in developed and emerging markets. International Marketing Review, 29(6), 574–596. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651331211277955

- Shukla, P., Rosendo-Rios, V., & Khalifa, D. (2022). Is luxury democratization impactful ? Its moderating effect between value perceptions and consumer purchase intentions. Journal of Business Research, 139(May 2020), 782–793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.10.030

- Shukla, P., & Purani, K. (2012). Comparing the importance of luxury value perceptions in cross-national contexts. Journal of Business Research, 65(10), 1417–1424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.007

- Smith, J. B., & Colgate, M. (2007). Customer value creation: A practical framework. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 15(1), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679150101

- Stathopoulou, A., & Balabanis, G. (2019). The effect of cultural value orientation on consumers' perceptions of luxury value and proclivity for luxury consumption. Journal of Business Research, 102, 298–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.02.053

- Timperio, G., Tan, K. C., Fratocchi, L., & Pace, S. (2016). The impact of ethnicity on luxury perception: The case of Singapore's Generation Y. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 28(2) https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-04-2015-0060, https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/APJML-04-2015-0060/full/html

- Tsai, S. P. (2005). Impact of personal orientation on luxury-brand purchase value: An international investigation. International Journal of Market Research, 47(4), 427–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/147078530504700403

- Tynan, C., Mckechnie, S., & Chhuon, C. (2010). Co-creating value for luxury brands. Journal of Business Research, 63(11), 1156–1163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.10.012

- Vigneron, F., & Johnson, L. W. (2004). Measuring perceptions of brand luxury. Journal of Brand Management, 11(6), 484–506. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540194

- Wang, F., Zhang, H., Zang, H., & Ouyang, M. (2005). Purchasing pirated software: An initial examination of Chinese consumers. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 22(6), 340–351. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760510623939

- Wiedmann, K., Hennigs, N., & Siebels, A. (2007). Measuring consumers ' luxury value perception: A cross -cultural framework. Academy of Marketing Science Review 2007(7), https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Klaus-Peter-Wiedmann/publication/228344191_Measuring_consumers'_luxury_value_perception_A_cross-cultural_framework/links/0c960524146a1d3e28000000/Measuring-consumers-luxury-value-perception-A-cross-cultural-framework.pdf

- Wiedmann, K., Hennigs, N., & Siebels, A. (2009). Value-based segmentation behavior. Psychology and Marketing, 26(7), 625–651. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar

- Wong, N. Y., & Ahuvia, A. C. (1998). Personal taste and family face: Luxury consumption in Confucian and Western societies. Psychology and Marketing, 15(5), 423–441. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(199808)15:5<423::AID-MAR2>3.0.CO;2-9

- Wu, B., & Yang, W. (2018). What do Chinese consumers want ? A value framework for luxury hotels in China. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(4), 2037–2055. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-08-2016-0466

- Yang, W., & Mattila, A. S. (2015). Why do we buy luxury experiences? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(9), 1848–1867. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-11-2014-0579

- Yu, S., Hudders, L., & Cauberghe, V. (2018). Selling luxury products online: The effect of a quality label on risk perception, purchase intention and attitude toward the brand. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 19(1), 16–35.

- Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52(3), 2–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298805200302

- Zici, A., Quaye, E. S., Jaravaza, D. C., & Saini, Y. (2021). Luxury purchase intentions: The role of individualism-collectivism, personal values and value-expressive influence in South Africa Luxury purchase intentions: the role of individualism-collectivism, personal values and value-expressive influence in So. Cogent Psychology, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2021.1991728, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/23311908.2021.1991728.