Abstract

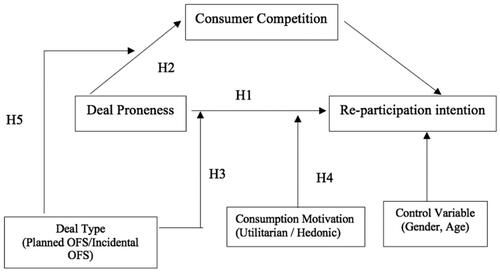

Online flash sales (OFS) have gained significant popularity in recent times. Interestingly, despite encountering service failures such as server errors, stockouts, and website crashes due to heavy online traffic, many consumers opt to re-participate in future OFSs offered by the same provider. Our study delves into the underlying reasons for such behavior. We formulated and tested our model based on scarcity theory and consumer deal proneness literature. We employed a 2 (deal type: planned vs. incidental) × 2 (consumer motivation: utilitarian vs. hedonic) between-subjects design. We used SPSS PROCESS Macro to test the moderation and moderated mediation effects. Findings indicate that deal-prone consumers tend to overlook service failures and choose to re-participate in online flash sales. Consumer competition mediates the relationship between deal proneness (DP) and re-participation intention (RPI). The effect of deal proneness on re-participation intention is decreased in incidental OFS compared to planned OFS, with the indirect effect moderated by the deal type. Additionally, consumption motivation moderates the main effect, with hedonic motivation significantly attenuating the effect compared to utilitarian motivation. Our research makes a significant contribution to the literature by highlighting the boundary conditions—namely deal type and consumer motivation—that influence the impact of deal proneness on re-participation intention in the context of OFS. This study offers a process-oriented view, highlighting the mediating role of consumer competition in the OFS landscape. We also illuminate new avenues by examining the impact of consumer motivation on the link between deal proneness and re-participation intention. Specifically, our findings related to the moderating effect of deal type present a fresh perspective to the existing body of knowledge. This study provides valuable insights for practitioners, particularly concerning segment targeting and the strategic incorporation of competition to bolster overall OFS participation. Moreover, our research underscores the importance for online retailers to pay heightened attention to service failures during incidental OFS, as these can significantly undermine their profitability.

Introduction

To grow sales revenue and profits, online Flash Sale (OFS) has become very popular with Internet business platforms such as Amazon, Flipkart, Snapdeal, Groupon, Paytm Mall, etc. During OFS, business platforms sell merchandise at deep discounts for a restricted period (Grewal et al., Citation2012). The deal typically ends at a pre-announced time or when all the items on sale are sold out, whichever occurs first (Shi & Chen, Citation2015).

Service failures at the pre-purchase stage, such as server errors, stockouts, website crashes, are widespread during OFS and adversely affect the profits of online retailers (Tan et al., Citation2016), besides upsetting customers. Interestingly, despite angry reactions and social media backlash following service failures during OFS, customers continue with their intention to participate in the subsequent OFS (Vakeel et al., Citation2018).

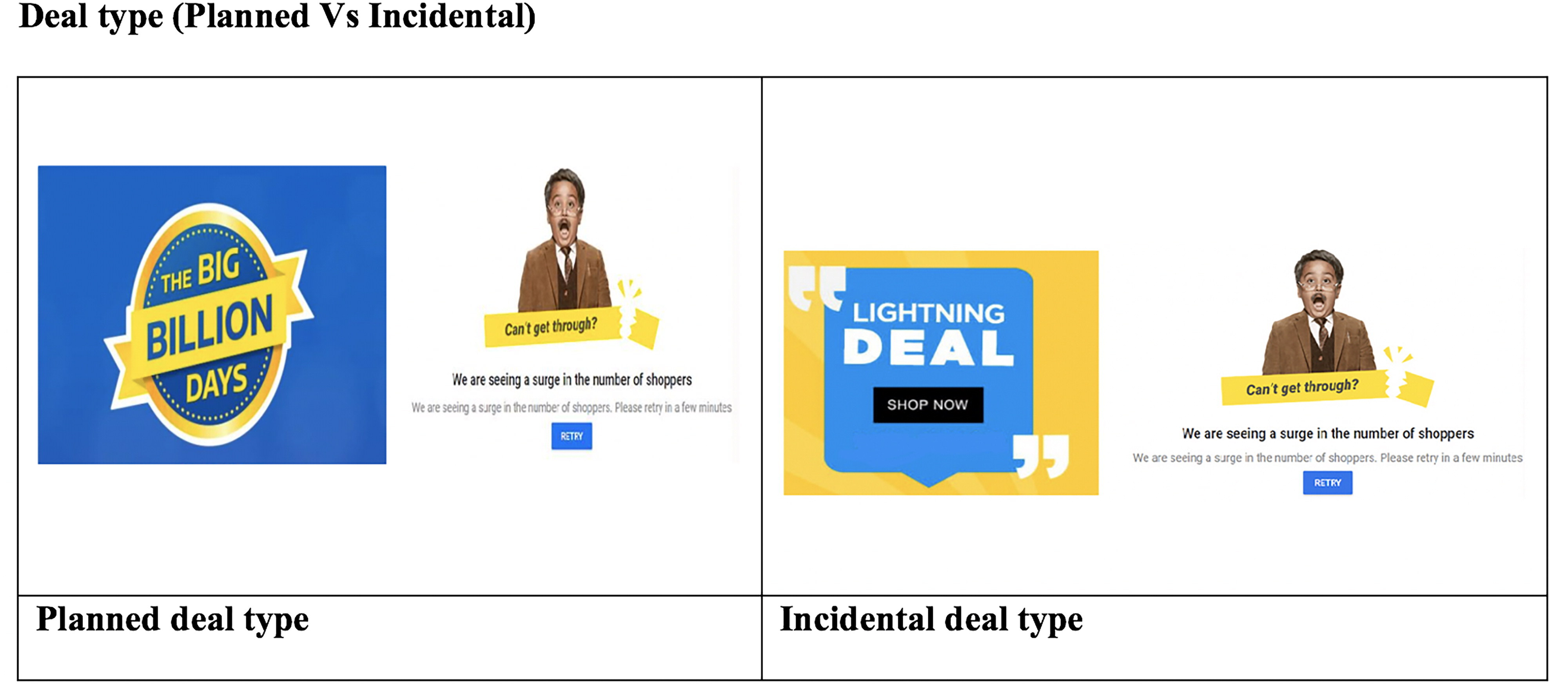

Impulse and planned sales promotional purchases result in different cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses (Kimiagari & Malafe, Citation2021). In the e-tail context, consumers are likely to encounter either planned OFS or incidental OFS. While Single’s Day sales, The Big Billion Days sales, etc., allow customers to plan their shopping, the lightning deals, daily deals, etc., are incidentally encountered when customers are moseying around in the online environment. However, prior research on service failure and re-participation in OFS has not investigated the impact of the deal type (planned vs incidental promotional offers) despite differences in cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses. Our study fills this gap.

Due to quantity and time restrictions associated with OFS, only a fraction of customers participating in OFS succeed in bagging the deal, triggering scarcity effects. Quantity-restricted promotions not only increase customer purchase intentions (Aggarwal et al., Citation2011) but could also trigger feelings of consumer competition (Nichols, Citation2012). However, prior research on service failure during online flash sales has not investigated the role of consumer competition in fostering re-participation intention. Our study fills this critical gap.

Given the ever-increasing pervasiveness of online shopping, Soergel (Citation2016) suggests that understanding the interaction of variables that drive consumer response is necessary. As electronic marketing becomes a central piece of marketing strategy, the need to develop new knowledge models and theories pertaining to internet commerce behavior has become necessary (Wagner et al., Citation2020). Our integrated model is novel in combining insights from scarcity effects, consumer competition, deal proneness, and consumer motivation in understanding re-participation intention in OFS.

This study’s theoretical and managerial contributions are as follows: First, we integrate insights from scarcity theory, consumer deal proneness, and service failure to provide a comprehensive explanation for this under-researched phenomenon of continuance intention in OFS despite service failure. Second, this study provides a process view by establishing the mediating role of consumer competition. Third, we investigate the moderation effects of deal type (incidental/planned) on re-participation intention in OFS. Fourth, we test moderated-mediation effects of deal type on the deal-proneness—consumer competition—re-participation intention link. Doing so enables us to understand the nature and the extent of consumer competition perceived in different types of OFS. Fifth, we investigate the moderation effects of consumer motivation (utilitarian/hedonic) on re-participation in OFS.

The findings of our study are significant from a managerial standpoint, as continued patronage despite service failure is critical for online business platforms to grow their sales revenue and profits. Customers abandoning online transactions due to service failures adversely affects the service provider’s bottom line (Tan et al., Citation2016).

Conceptual framework

Online flash sale

An online flash sale is similar to any brick-and-mortar flash sale, where occasionally, online retailers sell goods at deep discounts, as high as 50% or sometimes even more, for a short period (varying from a few minutes to a few hours) with a limited unit of stocks on sale (Liu et al., Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2020; Das et al., Citation2019; Vakeel et al., Citation2018, Grewal et al., Citation2012). E-tailing platforms use online flash sales to promote products and sell goods such as consumer electronics, apparel, etc., at massive discounts (Sujata et al., Citation2017). It provides an opportunity to customers and online retailers, where customers get to make huge savings, and retailers can generate more sales and clear inventory (Das et al., 2019)

An online flash sale is a time-pressured, failure-prone environment that gives the opportunistic customer a chance to secure significant financial gains. Flash sales are not just used as a business model but also feed into marketing and promotional purposes (Lamis et al., Citation2022). Depending on the sales period, the flash sale offered by online business platforms are also known as “deal of the day”, “daily deal”, “lightning deal”, and so on (Shi & Chen, Citation2015).

Service failure

Research shows that service failures such as server errors and stockouts during online flash sales result in disconfirmation between desired and actual service levels, leaving many customers angry. The discrepancy in the service expectation can be at two levels, one with the process and the other with the outcome (Smith et al., Citation1999). Obstruction of service delivery, such as a technical issue faced while purchasing a product online, is a process failure (Sivakumar et al., Citation2014). However, outcome failure results in the service provider’s inability to provide the core service—for instance, a cracked screen of a mobile handset bought online (Choi et al., Citation2021). Relative to outcome failures, process failures result in greater customer dissatisfaction (Smith et al., Citation1999).

All major business platforms, including (but not limited to) Amazon, Snapdeal, Macy, Flipkart, Target, and PayPal, have crashed during their biggest sales day of the year due to unprecedented traffic (Gustafson, Citation2015). Service failures encountered by business platforms such as the above during OFS vary from any other service failures as these failures cannot be recovered due to sudden surges in demand and time pressures (Smith et al., Citation1999). Yet, despite recurring disconfirmation, customers take part in online flash sales.

Intention to re-participation

The theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behavior demonstrate that consumers’ intentions directly impact their actual behavior (Agag & El-Masry, Citation2016). Behavioral intentions refer to a person’s likelihood of engaging in a specific behavior (McKnight et al., Citation2002). A strong association exists between actual behavior and behavioral intention (Casaló et al., Citation2010). Intention is widely acknowledged and accepted as an excellent proximal and powerful predictor of behavior (Venkatesh et al., Citation2022). As a result, we view the intention to re-participate in an online flash sale as a reliable indicator of a consumer’s re-participation in the online flash sale with a likely intention to purchase. Previous studies have extensively used the concept of ‘intention to purchase’ as a proxy to represent the actual buying behavior of customers on e-commerce platforms. Purchase intention signifies the willingness to purchase a product, whereas purchase behavior pertains to the actual purchase on an electronic platform (Chaudhuri et al., Citation2021).

Scarcity effects and consumer competition

Online flash sale is designed such that either a predefined number of units are sold or the sale duration (time window) is limited, or both. Therefore, only a limited number of customers can purchase the product, triggering scarcity effects. The psychological effects of unavailability are well documented in the literature. The Scottish philosopher and economist Adam Smith (1876, Citation1937) suggests, "the merit of an object, which is in any degree either useful or beautiful, is greatly enhanced by its scarcity, or by the great labor which it requires to collect any considerable quantity of it" (Lynn, Citation1992; pp. 172).

Consumers desire unavailable things as it bestow status and social position (Barton et al., Citation2022). There is ample evidence of consumers pushing, fighting, and wrecking retail stores and creating a riot-like scene in scarcity-fueled demand situations (Lynn, Citation1992).

Using scarcity effects to stimulate consumer demand has been widely prevalent in marketing (e.g., Redine et al., Citation2023). Sales promotions with a scarcity appeal cause aggressive behavior during shopping because of the increased competitiveness to obtain seemingly scarce goods (Harikrishnan et al., Citation2022; Peschel, Citation2021). During online flash sales, online business platforms craftily mix limited time scarcity (LTS) and limited quantity scarcity (LQS) to stimulate consumer demand (Cialdini, Citation2009). During online flash sales, the supplies are kept artificially low to create perceptions of scarcity (Cialdini, Citation2009; Kristofferson et al., Citation2016). Quantity-restricted promotions not only increase consumer purchase intention (Aggarwal et al., Citation2011) but also trigger feelings of consumer competition (Nichols, Citation2012).

Online flash sale – deal type

Internet business platforms have devised novel ways of price promotions (Wood et al., Citation2021). Some examples are Cyber Monday, Single’s Day promotion, the Big Billion Day sales, flash sales, and lightning deals by several online retailers. Events such as Single’s Day promotions are an online, one-day annual sales festival in which millions of products are sold at substantial price discounts. Two weeks prior to the D-day, promotion information is shared by the online retailers so that consumers can start planning for the promotion (Wang et al., Citation2019). Prior research (See Lennon et al., Citation2011) suggests that customers spend significant time and energy searching for information to create elaborate shopping plans. We categorize this as “planned deal type” as it allows consumers to plan their shopping.

Daily deals, lightning deals, etc., are online flash sales in which an internet business platform offers one or more products at a substantial discount for a few hours (Eisenbeiss et al., Citation2015) with significantly less frenzy and media spending compared to events such as Single’s day or The Big billion day sales. Several large online retailers offer them under unique names, such as: Value of the Day (Walmart), Deal of the Day/lightning deals (Flipkart), and Gold Box (Amazon). Since promotion information pertaining to this category of OFS is not widely available, it may not be possible for consumers to plan their shopping. Hence, we categorize this as an “incidental deal type”.

Consumption motivation

The differences between planned and unplanned purchase behavior are well-documented (See Gilbride et al., Citation2015). Unplanned purchase is characterized by an impulsive urge to buy (Dhandra, Citation2020). Prior research suggests that it is highly likely that hedonic items tend to be purchased in an unplanned manner as a greater positive affect is experienced compared to functional items (Inman et al., Citation2009). Prior research suggests the following six components of hedonic motivation: social, gratification, adventure, role, idea, and value. The perceived sense of enjoyment is generated by these six hedonic benefits, which form the hedonic value (Chiu et al., Citation2014). Hedonic motivations are related to fantasy, multisensory, and emotional worth (Akram et al., Citation2021; Lim et al., Citation2017).

Utilitarian motivation is characterized by buying with a functional temperament where the purchase’s crucial purpose is to satisfy a particular functional requirement (Amatulli et al., Citation2020); Akram et al., Citation2021). Utilitarian purchases are characterized by a lack of rush (Kukar-Kinney et al., Citation2016). Utilitarian benefits include shopping convenience, a wider range of product offerings, detailed product information, and financial savings in the form of lower prices and sales promotions (Chiu et al., Citation2014).

It is well-known that emotional states influence consumer shopping behavior (Shahpasandi et al., Citation2020). During online shopping, affective experience has a greater effect on customer’s emotional and behavioral responses (Barari et al., Citation2020), and emotional value significantly influences the intention to purchase (Zhang et al., Citation2020). Hedonic motivations are associated with a positive attitude toward coupon use, a more positive mood, and enhanced intention and actual purchase (Ieva et al., Citation2018). We investigate the role of consumption motivation on re-participation intention following a service failure during the online flash sale ().

Hypotheses development

Main effect of deal proneness

Deal proneness is “a general propensity to respond to promotion predominantly because they are in deal form” (Lichtenstein et al., Citation1990, pp. 55). According to Martínez and Montaner (Citation2006), a deal-prone customer is one who alters his purchase behavior and decisions to be benefited from the incentives offered by the promotions. Flash sale proneness is a distinct category of deal proneness in which customers exhibit readiness to purchase articles as they are available in the form of OFS (Vakeel et al., Citation2018).

Price promotions are known to result in anxiety about price variations, planning, and hedonic benefits such as enjoyment of deal hunting among customers (Pechtl, Citation2004). Like coupon-prone consumers eagerly scan for advertisements to locate price cuts, OFS-prone consumers pay attention to online flash sale announcements. They may actively browse through the website sections where deals of the day, lightning deals, and other deal-related information are usually available. For the deal-prone shopper, a deal is “an end in itself as well as means to an end” (Lichtenstein et al., Citation1990, pp. 56). As deal proneness is known to influence purchase intentions, consistent with previous studies positively (Vakeel et al., Citation2018), our hypothesis is:

H1: After encountering service failure, consumers’ deal proneness is positively associated with their intentions to take part in online flash sales.

Simple mediation: consumer competition

Early research on scarcity largely focused on events such as economic recession (Griskevicius et al., Citation2010), famine, and drought (Chakravarthy & Booth, Citation2004). However, the phenomenon of scarcity can be experienced in resource-rich, non-essential consumer goods as well (Lynn, Citation1991). Using scarcity effects to stimulate consumer demand is a common practice in marketing (Shi & Chumnumpan, Citation2020).

During promotion sales, the supplies are intentionally held low, thereby creating perceptions of scarcity (Kristofferson et al., Citation2016). Since only a predefined number of units are sold during OFS, consumers are likely to experience scarcity effects.

Quantity-restricted promotions not only increase consumer purchase intentions (Aggarwal et al., Citation2011) but also trigger feelings of consumer competition (Nichols, Citation2012). Consumer competition is “the act of consumer’s striving against other fellow consumers for achieving a desired economic or psychological reward” (Aggarwal et al., Citation2011, pp. 20). Daily deals are known to trigger social pressure, given the limited availability, as they display information to potential buyers about the number of units already sold (Kukar-Kinney, 2016). In addition to monetary savings, the deal restrictions enhance the feeling of winning a bargain (Schindler, Citation1989). Customers who are more prone to respond toward promotional sales are likely to perceive amplified competition from fellow customers (Peinkofer et al., Citation2016). Thus, scarcity perceptions increase purchase intentions as well as trigger feelings of consumer competition. Therefore, our hypothesis is:

H2: Consumer competition mediates the relationship between consumers’ deal proneness and intentions to take part in online flash sales.

Moderation effects of deal type

On the basis of the availability of promotional details of an online flash sales, it can be categorized as planned and incidental. OFS, such as Single’s Day sales, the big billion day sales, etc., share promotion details well in advance, enabling customers to direct their efforts to plan their participation in OFS (Wang et al., Citation2019). Advance information enables customers to draw up elaborate shopping plans (Lennon et al., Citation2011). Mano and Elliott (Citation1997) suggest that the essence of being a consumer is the ability to identify, accumulate, and calculate market information pertaining to goods and prices. Planned OFS, such as Cyber Monday, Single’s Day sales, the Big Billion Day sales, etc., allow consumers to gather and assess marketing information.

However, as promotional information pertaining to lightning deals, daily deals, etc., is not widely advertised, it may not be possible for consumers to plan their shopping. Consumers are more likely to encounter these deals incidentally during the course of their online shopping. Incidental deals are more frequent, and given the deal-abundant retail environment, customers are likely to encounter incidental deals more frequently.

Daily deals tend to attract new customers compared to existing ones (Constant Contact, Citation2013). Cao et al. (Citation2018) suggest that online daily deals are more popular with first-time customers. A significant number of daily-deal vouchers (80% or more) are purchased by first-time customers in the later part of the promotion cycle (Dholakia, Citation2012). Consumers suffer not only economic losses but also emotional distress when they fail to redeem vouchers on daily deal websites (Kukar-Kinney et al., Citation2016). Therefore, our hypothesis is:

H3: The relationship between consumers’ deal proneness and intentions to take part in online flash sales is moderated by deal type.

Moderation effects of consumption motivation

The impact of emotional states on consumer shopping behavior is well known (Shahpasandi et al., Citation2020). In the study conducted by Zhang et al. (Citation2020), they suggest that emotional value is one of the most important predictors of intention to purchase.

Customers with utilitarian motivations approach shopping with a work mentality, and purchases are primarily aimed at fulfilling a specific functional need (Amatulli et al., Citation2020). Utilitarian purchases are rarely associated with rush (Kukar-Kinney et al., Citation2016)). According to Li et al. (Citation2020), hedonic motives underline positive feelings such as pleasure and excitement, which consumers typically experience during online purchases.

Hedonic motivations result in the pursuit of the intrinsic value of a task, and customers with such motivations shop for the experience itself (Hamari et al., Citation2016). Consequently, it is more likely to result in higher deal proneness as consumers tend to participate in daily deals to overcome negative feelings in life and find relief in shopping (Faber & O’Guinn, Citation1992; Dholakia, Citation2012). For high deal-prone customers driven by hedonic motivations, shopping is a tension-reducing mechanism and makes them happy in the short run (Aboujaoude et al., Citation2003).

Bridges and Florsheim (Citation2008), in their review, suggest that hedonic values obtained from shopping are no different from the desires fulfilled by the pathological use of the Internet. They suggest that hedonic values obtained from shopping are commonly associated with compulsive shopping. Hence, interventions that encourage deal-shopping stickiness may also promote hedonic value and compulsivity. Therefore, our hypothesis is;

H4: Consumption motivation moderates the relationship between consumers’ deal proneness and intentions to take part in online flash sales.

Moderated mediation effects of deal type

Consumers inferring quantity and time-limited information in the online environment as a scarcity message is well documented (Cialdini, Citation2009). The competitive arousal model explains the role played by perceived rivalry and time pressure in fueling arousal, which in turn impacts individual decision-making (Ku et al., Citation2005). In the context of auctions, Ku et al. (Citation2005) found that competitive arousal resulted in overbidding. In the online auction context, the “desire to win” was enhanced by rivalry and time pressure (Malhotra, Citation2010; Wu et al., Citation2021).

Planned online flash sales such as the Single’s Day sale, the big billion day sales, the great Diwali sales, etc., are the largest sales day of the year. Online business platforms share promotion details well in advance, enabling customers to direct their efforts to plan for the online flash sale (Wang et al., Citation2019). Given that planned deals are less frequent compared to incidental deals and are accompanied with a media frenzy, planned deals are more likely to result in a “Social proof mechanism” (Cialdini & Goldstein, Citation2004) in which others’ opinions signal the value of the product. Sharing promotion details well in advance for the planned deals is also likely to result in “bandwagon reasoning” (Worchel et al., Citation1975), in which consumers assess a product’s worth on the basis of relative demand, inferring that the fellow consumers’ demand implies value. Therefore, our hypothesis is;

H5: Deal type moderates the indirect effect of consumer deal proneness on intentions to take part in online flash sales via consumer competition.

Research method

We use scenario-based experiment for the current study. As studies involving service failure, scenario-based experiments are considered to be appropriate as conducting studies in real settings involving real service failures could be difficult due to the ethical issues involved and the expenses involved (Jayasimha & Billore, Citation2016; Kim & Jang, Citation2014).

A 2 (Deal Type: Planned Deal, Incidental Deal) × 2 (Consumption Motivation: Hedonic, Utilitarian) between-subject experimental design was used. Since the primary objective is to test the boundary conditions for re-participation in online flash sale following a service failure, it was imperative to collect data from the individuals who have prior experience of participating in an OFS and have experienced a service failure. Hence, a purposive sampling method was used for data collection. The following two criteria were used to identify eligible respondents: (a) participants must have participated in an OFS in the last one year, and (b) participants must have had a service failure experience during an OFS. Internet was used as the medium to administer the survey to respondents as it is a cost-effective, quick, and convenient method of soliciting responses from participants (Zikmund, Citation1999). Authors floated the survey link on various online social media platforms as users of these platforms are more likely to use the OFS for their purchases.

We got 213 responses to our survey. After discarding incomplete and inconsistent responses, the final usable sample was 196. Respondents were aged between 18 and 35 years, and 56% of the respondents were male.

Scenario development

To identify appropriate stimuli, two doctoral students tracked five leading online business platforms for a period of 3 months. Literature on online flash sales and Deals-of-the-day (DOD) also helped in identifying suitable stimuli. The researchers segregated the deals on the basis of planned and incidental OFS based on the frequency of the OFS and pre-promotion information made available by the business platform that would enable the customers to plan their participation. The level of agreement between the two raters was 90%, which is acceptable (Isabella, Citation1990). The researchers also identified service failures associated with online flash sales during this period. Electronic gadgets (particularly mobile phones), fashion, and packaged consumer goods represented the most popular categories for online flash sales. Based on this, a process failure scenario for an online flash sale for mobile phones was developed and implanted in the survey (See Appendix A).

The scenario required the respondents to imagine participating in an online flash sale in which mobile phones were being sold at a huge discount. Even after spending a great deal of time, the participant was not able to get the deal due to an unprecedented surge in traffic to the website and resultant technical problems. The participant could not place the order, and finally, the website crashed. Subsequently, the respondents were informed that the same e-commerce platform has announced another new flash sale, and then their likelihood of re-participation was measured.

Pretest and manipulation check

A preliminary test involving 120 students with prior Online Food Service (OFS) experience was conducted. This pretest aimed to evaluate the realism and believability of the scenarios, as well as to assess the psychometric properties of the measurement scales used in the study. In response to their participation in the pretest, students were rewarded with cafeteria coupons valued at approximately two dollars upon successful completion. The assignment of participants to one of the four scenarios was conducted randomly. The social desirability bias was addressed by instructing the participants that the responses collected would be completely anonymous and would be used at an aggregate level. Further, the response bias was minimized by randomizing the items of the instrument (Nederhof, Citation1985).

Three-item measure (Bagozzi et al., Citation2016; Belanche et al., Citation2020) on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1= strongly agree and 7 = strongly disagree) was used to assess realism. Sample item included “The scenario is realistic”. The results confirmed the appropriateness of the scenarios for the study. Deal proneness (sample item; “participating and taking advantage of flash sale deals makes me feel good”) and re-participation intention were measured similar to the previous work of Vakeel et al. (Citation2018). Consumer competition (sample item; “I will be competing with others to buy mobile phone during the online flash sale”) was measured using a modified consumer competition arousal scale developed by Nichols (Citation2012) on a 7-point Likert scale (1= strongly agree and 7 = strongly disagree) (Lee et al., Citation2009). Two items from the original consumer competition scale were dropped during the face validity stage as the experts (two senior executives and two professors with expertise in psychometrics) who evaluated the items felt that these were inappropriate for the study context. During exploratory factor analysis (EFA), two items from the original consumer competition scale had to be dropped as they failed to meet the criterion of 0.60 factor loading (Hair et al., Citation1998).

One item measure, “The advance information enables me to plan my participation” (1 = strongly agree and 7 = strongly disagree), allowed us to check deal type manipulation. The value (M BigBillionDay = 6.1 vs. M Lightning Deal 1.8, p < 0.01) confirmed that the manipulation worked as expected. Manipulation of consumption motivation was in line with previous studies (see, Seo et al., Citation2016). Hedonic consumption motivation was described as “variety-seeking”, and utilitarian motivation was described as buying out of “necessity” (See Appendix A for details). Similar to Seo et al. (Citation2016), three items were used to assess consumer motivations (utilitarian vs hedonic). Participants who were in utilitarian purchase scenarios evaluated it as more utilitarian than ones in hedonic scenarios (Mutilitarian = 5.12 vs. Mhedonic = 1.70, p < 0.01). The results showed that the manipulation did work as planned.

Measurement model

In our main study, which involved 196 participants, we used the scales previously described in the pretest section. To measure deal proneness, we employed a 4-item scale (α = 0.831), and to measure re-participation intention, we used a 3-item scale (α = 0.762). Both scales were sourced from Vakeel et al. (Citation2018). Additionally, we adopted a 6-item scale for consumer competition (α = 0.859) from Nichols (Citation2012). Refer to .

Table 2. Scale items and psychometric properties.

The measurement model was assessed using partial least square (PLS) using SmartPLS-3.0. Results revealed an acceptable model fit as suggested by Henseler et al. (Citation2016) (Chi-square (164) = 315.673; Chi-square/df = 1.924; SRMR = 0.049; NFI = 0.890). Composite reliability values were in the range of 0.863 to 0.895, all above the prescribed value of 0.70, as suggested by Nunnally (Citation1978), indicating a good reliability of all the constructs. The value of Average Variance Extracted (AVE) was between 0.589 and 0.677, all above the recommended level of 0.50 as claimed by Henseler et al. (Citation2016), demonstrating good convergent validity of the measures used in the study (refer to ).

Table 1. Discriminant validity.

All the scales demonstrated adequate discriminant validity based on the criteria proposed by Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981). The values of Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) were also well under the conservative criterion of 0.85 (Henseler et al., Citation2015). The factor loadings of all the items on their respective factors were between 0.676 and 0.890, well above the acceptable value of 0.60 (Hair et al., Citation1998) (refer to ). The common method bias was assessed by conducting Harman’s Single Factor test. We loaded all our items to a single factor and found that the total variance explained was less than 50%, as recommended by Podsakoff et al. (Citation2003), indicating that there is no issue of common method biases in this study.

Manipulation checks

The manipulation checks conducted during this phase of research were very similar to the pretest stage. Deal type manipulation was as expected (M BigBillionBay = 5.9 vs. M Lightning Deal = 2.0, p < 0.01), and manipulation of consumption motivation (M utilitarian = 5.2 vs. M hedonic = 2.1, p < 0.01) revealed that even for the main study, the manipulations worked as expected.

Results

The hypothesis was tested using SPSS PROCESS macro (version 3.5; Hayes Citation2020). To test the effects of deal proneness on re-participation intention, we did a regression analysis. Gender and age were included as control variables. The result shows that deal proneness leads to re-participation intention (β = 0.685, t (195) = 12.726; p < .000) after controlling for gender (β = 0.093, t (195) = 0.831; p = .407) and age (β = −0.010, t (195) = −0.870; p = .385) in an OFS even after a service failure experience during previous OFS. This provides support for Hypothesis H1 (refer to ).

Table 3. Summary of results.

We used PROCESS model 4 to test for mediation effects through consumer competition. We investigated the indirect effect of deal proneness on re-participation intention through consumer competition (mediation hypothesis H2), the results showed (β = 0.2251, SEboot = 0.0697, CI = 0.0875, 0.3626) that this mediation path is significant at 95%, as zero does not lie between lower and upper confidence interval (Hayes, Citation2013, Citation2015; Montoya and Hayes Citation2017) providing support to our mediation hypothesis H2 (refer ).

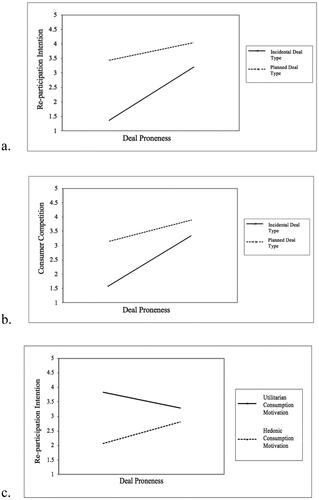

The moderation effect of deal type was tested using PROCESS model 1. Results revealed that the overall model was significant (F (3, 192) = 86.2332, p< .0000, R2 = 0.5740) along with significant interaction between deal proneness and deal type (β = −0.3235, SE = 00.1096, t (192) = −2.9521, p = .0036) supporting our hypothesis H3 (refer ). (a) presents the moderation effect of deal type.

Figure 2. Moderation effect of deal type and consumption motivation. Notes: (a) Moderation effect of deal type. (b) Moderation effect of deal type (on consumer competition mediation effect). (c) Moderation effect of consumption motivation.

The moderation effects of deal type on the mediation, i.e., on the mediation path through consumer competition (DP→CC→PI) was tested using PROCESS model 7 using a bootstrap sample of 10,000 at 95% bootstrap CI. Moderate mediation was investigated, where the indirect effects of deal proneness through consumer competition on re-participation intention were moderated by deal type (on the mediational path between deal proneness and consumer competition). The PROCESS macro generates an index of moderated mediation. The results revealed a significant interaction between deal proneness and deal type (β = −0.2640, SE = 0.1170, t (192) = −2.2559, p = .0252). The index of moderated mediation (Index= −0.0594, SEboot = 0.0310, CI = −0.1312, −0.0127) does not include zero within the range of 95% confidence interval. This supports our hypothesis H5 (refer to ). (b) presents the moderation effects of deal type on deal proneness and consumer competition.

The moderation effect of consumer motivation was tested using PROCESS model 1. Results revealed that the overall model was significant (F (3, 192) = 75.4993, p< .0000, R2 = 0.5412) along with significant interaction between deal proneness and deal type (β = 0.3411, SE = 0.1070, t (192) = 3.1869, p = .0017). This supports our hypothesis H4 (refer to ). (c) presents the moderation effect of consumption motivation.

Discussion

Summary

This research used scarcity effects and consumer competition as its foundation to empirically investigate the impact of service failure experience on consumer deal proneness and their re-participation intention in online flash sales. The process view provided by this study is novel. Taking part in online flash sales despite service failure is an interesting phenomenon. As consumers associate greater access convenience with online services (Keh & Pang, Citation2010) and as online flash sale has a critical role in driving sales revenue and profits of online business platforms, this study is contextually relevant. The findings of our research both supports as well extends the current research findings on service failure during online flash sale and re-participation intention. The validation of the positive relationship between consumers’ deal proneness and intentions to take part in online flash sales is in line with Vakeel et al. (Citation2018).

Perceiving other customers as competitors is not limited to brick-and-mortar retail stores during the black Friday sales but is also experienced during online flash sales. In the study conducted by Wu et al. (Citation2021), they validated that LQS (Limited Quantity Scarcity) had a greater impact on influencing consumers’ offline purchase intentions compared to LTS (Limited Time Scarcity). However, there is limited existing literature exploring the effects and benefits of LQS over LTS, specifically in the context of online shopping, because customers have dynamic visibility to both types of scarcity information while browsing the product online. By receiving regular updates regarding diminishing supply and being exposed to time constraints through a countdown of the remaining shopping time, buyers perceive a heightened sense of urgency that intensifies over time. This phenomenon is magnified during online flash sales, and therefore, it is critical to understand consumer behavior.

The moderating effects of deal type are an important one. Similar to brick-and-mortar retail (McConnell et al., Citation2000; Redine et al., Citation2023), even in the online environment, promotional offers can precipitate planned and impulse purchases. Past studies have noticed that there are cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses to impulsive and planned promotional events in brick-and-mortar retailing and online buying (Kimiagari & Malafe, Citation2021). During online flash sales, there is a notable distinction between planned and incidental participation by customers. However, the cognitive response is significantly stronger in planned flash sales compared to incidental ones. This heightened cognitive response often translates into a more substantial behavioral reaction, with some customers even discontinuing their participation. The reason behind this notable response could be attributed to the fact that planned flash sales are pre-announced, leading customers to eagerly await online deals. Consequently, if customers are unable to secure the desired deals after a prolonged waiting period, they experience a sense of disappointment, which contributes to intensified cognitive and behavioral responses.

Along similar lines, the impact of hedonic and utilitarian purchases can be seen, where the behavioral response is fundamentally different (Seo et al., Citation2016). The moderating effects of consumer consumption motivation reveal that consumers who participate in an online flash sale with a hedonic motivation, i.e., for fun or pleasure, tend to re-participate despite a service failure. However, the customers with utilitarian motivations having a work/task orientation tend to discontinue their participation.

Theoretical contributions

This study contributes to the literature on service failure, online flash sales, and online consumer behavior by integrating the insights from scarcity theory, deal proneness, deal type, and consumer motivation to offer an integrated view of consumer re-participation in online flash sales despite service failure. Past studies in this field have not paid enough attention to the online flash sale context. Our study not only fills this gap but also tests the veracity of the earlier findings (Vakeel et al., Citation2018). It also enhances the generalizability of the findings that deal-prone consumers overlook service failure during OFS and continue their intention to participate in the subsequent OFS. Our study also demonstrates that there are some boundary conditions to the above relationship.

This study contributes to service failure, customer intentions, and behavior in the online flash sale context by providing a process view of re-participation in OFS despite service failure. We empirically test the mediating role of consumer competition. Consumer competition is not limited to holiday sales in the brick-and-mortar retail context but is also experienced during the OFS. High deal-prone customers experience consumer competition (Peinkofer et al., Citation2016) triggered by scarcity effects, which in turn motivates re-participation in online flash sales despite service failure. Our study also found that the desire to win is exacerbated in the case of planned online flash sales due to their limited frequency and customers’ ability to master-plan their participation.

Literature confirms that the cognitive and affective outcomes associated with hedonic and utilitarian purchases are fundamentally different (Seo et al., Citation2016), and our research shows new paths and investigates the impact of consumer motivation on deal proneness and re-participation intention link. Deal-prone customers who participate for fun tend to ignore service failures compared to customers who approach shopping with a work mentality, and the shopping aims to satisfy a particular functional requirement (Amatulli et al., Citation2020).

Our research contributes novel insights to the existing literature regarding the moderating effects of deal type. Specifically, we found that planned OFS deals, which are typically less frequent but announced in advance, enable deal-prone customers to engage in more effective planning. These planned OFS deals present unique dynamics in customer behavior, distinguishing them from more spontaneous or incidental deal offerings. The prevalence of incidental OFS deals in an online retail environment already saturated with deals has led to a decrease in their novelty (Tuttle, Citation2011) and an increase in consumer aversion toward such deals (Patel, Citation2012). Consequently, following a service failure, our findings indicate that the intention to re-participate is weaker with incidental OFS compared to planned OFS. This suggests that the excessive availability and reduced distinctiveness of incidental OFS deals may diminish their appeal, particularly in the context of service recovery.

Managerial implications

The findings of the study are important, as continued patronage despite service failure is critical for online business platforms. Customers abandoning online transactions due to service failure could severely hurt the service provider’s bottom line. (Tan et al., Citation2016).

The finding of this study has several implications for managers regarding the segments they must target during online flash sales. Identifying and targeting customers who are high deal prone should be a priority for managers as such customers ignore the process to make the best out of the online flash sale. Second, if managers could successfully inject competition among customers in the form of preview to sales, pre-sale registration of members, and strategically use promotion mix elements to signal scarcity, customers could continue to participate in online flash sales despite service failure. Consumer competition triggered by scarcity effects plays an important role in re-participating in the flash sale despite previous process failure incidents. The website could share information about how many other customers have wish-listed a particular item wish-listed by the focal customer. This would help in signaling consumer competition. Third, live discount coupons for a predefined number of customers could also increase competition among the customers and, ultimately, the intention to re-participate. Fourth, the manager should provide an option like “Know When on Deal” where customers can pre-select the products that they want to buy but only when it is on a deal. This option will notify the buyers about the deal on products, which will increase the purchase intention of the products on daily deals, i.e., incidental deal type. Lastly, even high deal-prone customers are not agnostic to service failure all the time. Service failures during incidental online flash sales deserve greater attention from online retailers.

Limitations and future research opportunities

This study has a few limitations, which also serve as a basis for the future research direction. First, we tested the conceptual model through scenario-based experiments; hence, future research may explore and test the model using field experiments, which can further establish the findings. Second, the respondents of the study were majorly limited to a few major tier-1 and tier-2 cities of India; therefore, future research may look into a wider and more diverse sample size for more insights. Third, the respondents who form the sample of the studies are the ones who have participated in an OFS in the last one year and have had an experience of service failure while participating or purchasing a product during the OFS. Future research may explore the impact of repetitive service failure experience of the participants while participating in an OFS on the intention to re-participate. Fourth, only process failure was investigated in the current research; since process failure is considered more potent, our investigation was limited to such failures in the context of online flash sales. Future research may investigate the impact of product failures in the context of online flash sales. Fifth, hedonic purchases are associated with guilt. In the present work, the role of guilt was not investigated. This is also a plausible avenue for future research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aboujaoude, E., Gamel, N., & Koran, L. M. (2003). A 1-year naturalistic follow-up of patients with compulsive shopping disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 64(8), 946–950. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v64n0814

- Agag, G., & El-Masry, A. A. (2016). Understanding consumer intention to participate in online travel community and effects on consumer intention to purchase travel online and WOM: An integration of innovation diffusion theory and TAM with trust. Computers in Human Behavior, 60, 97–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.038

- Aggarwal, P., Jun, S. Y., & Huh, J. H. (2011). Scarcity messages. Journal of Advertising, 40(3), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091-3367400302

- Akram, U., Junaid, M., Zafar, A. U., Li, Z., & Fan, M. (2021). Online purchase intention in Chinese social commerce platforms: Being emotional or rational? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 63, 102669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102669

- Amatulli, C., De Angelis, M., & Donato, C. (2020). An investigation on the effectiveness of hedonic versus utilitarian message appeals in luxury product communication. Psychology & Marketing, 37(4), 523–534. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21320

- Bagozzi, R. P., Belanche, D., Casaló, L. V., & Flavián, C. (2016). The role of anticipated emotions in purchase intentions. Psychology & Marketing, 33(8), 629–645. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20905

- Barari, M., Ross, M., & Surachartkumtonkun, J. (2020). Negative and positive customer shopping experience in an online context. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 53(33), 101985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101985

- Barton, B., Zlatevska, N., & Oppewal, H. (2022). Scarcity tactics in marketing: A meta-analysis of product scarcity effects on consumer purchase intentions. Journal of Retailing, 98(4), 741–758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2022.06.003

- Belanche, D., Casaló, L. V., Flavián, C., & Schepers, J. (2020). Robots or frontline employees? Exploring customers’ attributions of responsibility and stability after service failure or success. Journal of Service Management, 31(2), 267–289. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-05-2019-0156

- Bridges, E., & Florsheim, R. (2008). Hedonic and utilitarian shopping goals: The online experience. Journal of Business Research, 61(4), 309–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.06.017

- Cao, Z., Hui, K. L., & Xu, H. (2018). When discounts hurt sales: The case of daily-deal markets. Information Systems Research, 29(3), 567–591. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2017.0772

- Casaló, L. V., Flavián, C., & Guinalíu, M. (2010). Determinants of the intention to participate in firm-hosted online travel communities and effects on consumer behavioral intentions. Tourism Management, 31(6), 898–911. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.04.007

- Chakravarthy, M. V., & Booth, F. W. (2004). Eating, exercise, and "thrifty" genotypes: Connecting the dots toward an evolutionary understanding of modern chronic diseases. Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md.: 1985), 96(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00757.2003

- Chaudhuri, N., Gupta, G., Vamsi, V., & Bose, I. (2021). On the platform but will they buy? Predicting customers’ purchase behavior using deep learning. Decision Support Systems, 149, 113622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2021.113622

- Chiu, C. M., Wang, E. T., Fang, Y. H., & Huang, H. Y. (2014). Understanding customers’ repeat purchase intentions in B2C e-commerce: The roles of utilitarian value, hedonic value and perceived risk. Information Systems Journal, 24(1), 85–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2575.2012.00407.x

- Choi, S., Mattila, A. S., & Bolton, L. E. (2021). To err is human (-oid): How do consumers react to robot service failure and recovery? Journal of Service Research, 24(3), 354–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670520978798

- Cialdini, R. B. (2009). Influence: Science and practice (Vol. 4). Pearson Education.

- Cialdini, R. B., & Goldstein, N. J. (2004). Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(1), 591–621. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142015

- Constant Contact. (2013). Research survey. https://news.constantcontact.com/press-release-new-constant-contact-study-links-multi-channel-marketing-small-business-success (accessed January 23, 2020).

- Das, S., Mishra, A., & Cyr, D. (2019). Opportunity gone in a flash: Measurement of ecommerce service failure and justice with recovery as a source of e-loyalty. Decision Support Systems, 125, 113130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2019.113130

- Dhandra, T. K. (2020). Does self-esteem matter? A framework depicting role of self-esteem between dispositional mindfulness and impulsive buying. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 55, 102135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102135

- Dholakia, U. M. (2012). How businesses fare with daily deals as they gain experience: A multi-time period study of daily deal performance. SSRN Electronic Journal, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2091655 or (accessed November 14, 2019). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2091655

- Eisenbeiss, M., Wilken, R., Skiera, B., & Cornelissen, M. (2015). What makes deal-of-the-day promotions really effective? The interplay of discount and time constraint with product type. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 32(4), 387–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2015.05.007

- Faber, R. J., & O’Guinn, T. C. (1992). A clinical screener for compulsive buying. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(3), 459–469. https://doi.org/10.1086/209315

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313

- Gilbride, T. J., Inman, J. J., & Stilley, K. M. (2015). The role of within-trip dynamics in unplanned versus planned purchase behavior. Journal of Marketing, 79(3), 57–73. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.13.0286

- Grewal, D., Roggeveen, A. L., Compeau, L. D., & Levy, M. (2012). Retail value-based pricing strategies: New times, new technologies, new consumers. Journal of Retailing, 88(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2011.12.001

- Griskevicius, V., Tybur, J. M., & Van den Bergh, B. (2010). Going green to be seen: Status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(3), 392–404. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017346

- Gustafson, K. (2015). Cyber Monday: Why retailers can’t keep their sites from crashing. www.cnbc.com/2015/11/30/cyber-monday-why-retailers-cant-keep-their-sites-from-crashing.html (accessed August 5, 2017).

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (1998). Multivariate data analysis. Prentice Hall.

- Hamari, J., Shernoff, D. J., Rowe, E., Coller, B., Asbell-Clarke, J., & Edwards, T. (2016). Challenging games help students learn: An empirical study on engagement, flow, and immersion in game-based learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 54, 170–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.045

- Harikrishnan, P. K., Dewani, P. P., & Behl, A. (2022). Scarcity promotions and consumer aggressions: A theoretical framework. Journal of Global Marketing, 35(4), 306–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2021.2009609

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. The Guilford Press.

- Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2014.962683

- Hayes, A. F. (2020). Statistical methods for communication science. Washington: Routledge.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modelling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modelling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(1), 2–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382

- Ieva, M., De Canio, F., & Ziliani, C. (2018). Daily deal shoppers: What drives social couponing? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 40, 299–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.03.005

- Inman, J. J., Winer, R. S., & Ferraro, R. (2009). The interplay among category characteristics, customer characteristics, and customer activities on in-store decision making. Journal of Marketing, 73(5), 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.73.5.19

- Isabella, L. A. (1990). Evolving interpretations as a change unfolds: How managers construe key organizational events. Academy of Management Journal, 33(1), 7–41. https://doi.org/10.2307/256350

- Jayasimha, K. R., & Billore, A. (2016). I complain for your good? Re-examining consumer advocacy. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 24(5), 360–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2015.1011204

- Keh, H. T., & Pang, J. (2010). Customer reactions to service separation. Journal of Marketing, 74(2), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.74.2.55

- Kim, J. H., & Jang, S. S. (2014). A scenario-based experiment and a field study: A comparative examination for service failure and recovery. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 41, 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.05.004

- Kimiagari, S., & Malafe, N. S. A. (2021). The role of cognitive and affective responses in the relationship between internal and external stimuli on online impulse buying behavior. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 61, 102567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102567

- Kristofferson, K., McFerran, B., Morales, A. C., & Dahl, D. W. (2016). The dark side of scarcity promotions: How exposure to limited-quantity promotions can induce aggression. Journal of Consumer Research, 43(5), ucw056. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucw056

- Ku, G., Malhotra, D., & Murnighan, J. K. (2005). Towards a competitive arousal model of decision-making: A study of auction fever in live and Internet auctions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 96(2), 89–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2004.10.001

- Kukar-Kinney, M., Scheinbaum, A. C., & Schaefers, T. (2016). Compulsive buying in online daily deal settings: An investigation of motivations and contextual elements. Journal of Business Research, 69(2), 691–699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.08.021

- Lamis, S. F., Handayani, P. W., & Fitriani, W. R. (2022). Impulse buying during flash sales in the online marketplace. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2068402. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2068402

- Lee, D., Paswan, A. K., Ganesh, G., & Xavier, M. J. (2009). Outshopping through the Internet: A multicountry investigation. Journal of Global Marketing, 22(1), 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/08911760802511410

- Lennon, S. J., Johnson, K. K., & Lee, J. (2011). A perfect storm for consumer misbehavior: Shopping on Black Friday. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 29(2), 119–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887302X11401907

- Li, J., Abbasi, A., Cheema, A., & Abraham, L. B. (2020). Path to purpose? How online customer journeys differ for hedonic versus utilitarian purchases. Journal of Marketing, 84(4), 127–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022242920911628

- Lichtenstein, D. R., Netemeyer, R. G., & Burton, S. (1990). Distinguishing coupon proneness from value consciousness: An acquisition-transaction utility theory perspective. Journal of Marketing, 54(3), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299005400305

- Lim, J. S., Heinrichs, J. H., & Lim, K. S. (2017). Gender and hedonic usage motive differences in social media site usage behavior. Journal of Global Marketing, 30(3), 161–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2017.1308615

- Liu, X., Zhou, Y. W., Shen, Y., Ge, C., & Jiang, J. (2021). Zooming in the impacts of merchants’ participation in transformation from online flash sale to mixed sale e-commerce platform. Information & Management, 58(2), 103409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2020.103409

- Lynn, M. (1991). Scarcity effects on value: A quantitative review of the commodity theory literature. Psychology & Marketing, 8(1), 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.4220080105

- Lynn, M. (1992). The psychology of unavailability: Explaining scarcity and cost effects on value. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 13(1), 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324834basp1301_2

- Malhotra, D. (2010). The desire to win: The effects of competitive arousal on motivation and behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 111(2), 139–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2009.11.005

- Mano, H., & Elliott, M. T. (1997). Smart shopping: The origins and consequences of price savings. Advances in Consumer Research, 24, 504–510.

- Martínez, E., & Montaner, T. (2006). The effect of consumer’s psychographic variables upon deal-proneness. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 13(3), 157–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2005.08.001

- McConnell, A. R., Niedermeier, K. E., Leibold, J. M., El-Alayli, A. G., Chin, P. P., & Kuiper, N. M. (2000). What if I find it cheaper someplace else?: Role of prefactual thinking and anticipated regret in consumer behavior. Psychology and Marketing, 17(4), 281–298. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(200004)17:4<281::AID-MAR2>3.0.CO;2-5

- McKnight, D. H., Choudhury, V., & Kacmar, C. (2002). The impact of initial consumer trust on intentions to transact with a web site: A trust building model. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 11(3–4), 297–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0963-8687(02)00020-3

- Montoya, A. K., & Hayes, A. F. (2017). Two-condition within-participant statistical mediation analysis: A path-analytic framework. Psychological Methods, 22(1), 6–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000086

- Nederhof, A. J. (1985). Methods of coping with social desirability bias: A review. European Journal of Social Psychology, 15(3), 263–280. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420150303

- Nichols, B. S. (2012). The development, validation, and implications of a measure of consumer competitive arousal (CCAr). Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(1), 192–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2011.10.002

- Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric methods. McGraw-Hill.

- Patel, K. (2012, February 27). Daily-deals: Do consumers still care? AdAge: Digital. https://adage.com/article/digital/daily-deals-consumers-care/233033 (accessed January 25, 2020).

- Pechtl, H. (2004). Profiling intrinsic deal proneness for HILO and EDLP price promotion strategies. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 11(4), 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0969-6989(03)00040-7

- Peinkofer, S. T., Esper, T. L., & Howlett, E. (2016). Hurry! Sale ends soon: The impact of limited inventory availability disclosure on consumer responses to online stockouts. Journal of Business Logistics, 37(3), 231–246. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbl.12136

- Peschel, A. O. (2021). Scarcity signalling in sales promotion: An evolutionary perspective of food choice and weight status. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 61, 102512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102512

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Redine, A., Deshpande, S., Jebarajakirthy, C., & Surachartkumtonkun, J. (2023). Impulse buying: A systematic literature review and future research directions. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 47(1), 3–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12862

- Schindler, R. M. (1989). The excitement of getting a bargain: Some hypotheses concerning the origins and effects of smart-shopper feelings. Advances in Consumer Research, 16, 447–453.

- Seo, J. Y., Yoon, S., & Vangelova, M. (2016). Shopping plans, buying motivations, and return policies: Impacts on product returns and purchase likelihoods. Marketing Letters, 27(4), 645–659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-015-9381-y

- Shahpasandi, F., Zarei, A., & Nikabadi, M. S. (2020). Consumers’ impulse buying behavior on Instagram: Examining the influence of flow experiences and hedonic browsing on impulse buying. Journal of Internet Commerce, 19(4), 437–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332861.2020.1816324

- Shi, S. W., & Chen, M. (2015). Would you snap up the deal?: A study of consumer behaviour under flash sales. International Journal of Market Research, 57(6), 931–957. https://doi.org/10.2501/IJMR-2015-072

- Shi, X., Li, F., & Chumnumpan, P. (2020). The use of product scarcity in marketing. European Journal of Marketing, 54(2), 380–418. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-04-2018-0285

- Sivakumar, K., Li, M., & Dong, B. (2014). Service quality: The impact of frequency, timing, proximity, and sequence of failures and delights. Journal of Marketing, 78(1), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.12.0527

- Smith, A. (1937). The wealth of nations. Random House. (Original work published 1876)

- Smith, A. K., Bolton, R. N., & Wagner, J. (1999). A model of customer satisfaction with service encounters involving failure and recovery. Journal of Marketing Research, 36(3), 356–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379903600305

- Soergel, A. (2016). As online sales boom, is brick-and-mortar on the way out? US News and World Report. www.usnews.com/news/articles/2016-12-20/with-online-sales-booming-is-brick-and-mortar-on-the-way-out (accessed January 25, 2020).

- Sujata, J., Menachem, D., & Viraj, T. (2017). Impact of flash sales on consumers & e-commerce industry in India [Paper presentation]. Annual International Conference on Qualitative & Quantitative Economics Research (pp. 11–19).

- Tan, C. W., Benbasat, I., & Cenfetelli, R. T, Copenhagen Business School. (2016). An exploratory study of the formation and impact of electronic service failures. MIS Quarterly, 40(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2016/40.1.01

- Tuttle, B. (2011). How daily-deals are losing their allure – For businesses and consumers alike. https://business.time.com/2011/08/30/how-daily-deals-are-losing-their-allure-for-businesses-and-consumers-alike/ (accessed January 19, 2020).

- Vakeel, K. A., Sivakumar, K., Jayasimha, K. R., & Dey, S. (2018). Service failures after online flash sales: Role of deal proneness, attribution, and emotion. Journal of Service Management, 29(2), 253–276. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-08-2017-0203

- Venkatesh, V., Speier-Pero, C., & Schuetz, S. (2022). Why do people shop online? A comprehensive framework of consumers’ online shopping intentions and behaviors. Information Technology & People, 35(5), 1590–1620. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-12-2020-0867

- Wagner, G., Schramm-Klein, H., & Steinmann, S. (2020). Online retailing across e-channels and e-channel touchpoints: Empirical studies of consumer behavior in the multichannel e-commerce environment. Journal of Business Research, 107, 256–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.10.048

- Wang, L., Yan, Q., & Chen, W. (2019). Drivers of purchase behavior and post-purchase evaluation in the Singles’ Day promotion. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 36(6), 835–845. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-08-2017-2335

- Wood, S., Watson, I., & Teller, C. (2021). Pricing in online fashion retailing: Implications for research and practice. Journal of Marketing Management, 37(11–12), 1219–1242. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2021.1900334

- Worchel, S., Lee, J., & Adewole, A. (1975). Effects of supply and demand on ratings of object value. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32(5), 906–914. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.32.5.906

- Wu, Y., Xin, L., Li, D., Yu, J., & Guo, J. (2021). How does scarcity promotion lead to impulse purchase in the online market? A field experiment. Information & Management, 58(1), 103283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2020.103283

- Zhang, Y., Xiao, C., & Zhou, G. (2020). Willingness to pay a price premium for energy-saving appliances: Role of perceived value and energy efficiency labelling. Journal of Cleaner Production, 242, 118555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118555

- Zikmund, W. G. (1999). Business research methods. The Dryden Press.

Appendix A.

Stimuli used in the study

Last time when you participated in (The Big Billion Days Sale/Lightning Deal) to purchase a handset, you had a very disappointing experience. It was an online flash sale in which mobile phones were being sold at a huge discount. Even after spending a great deal of time, you were unable to get the deal due to unprecedented surge in traffic to the website and other technical problems such as no response from the website, server time out, unable to land on the correct page etc. You could not place the order and finally, the website crashed.

Now a mobile phone brand has tied up with the same Indian e-commerce company and has announced new flash sale (The Big Billion Days Sale/Lightning Deal) on a different model of mobile phones at never before prices.

Product type (Utilitarian vs. Hedonic)

Utilitarian

You need a mobile phone, therefore you spend a great deal of time trying to buy the handset, but faced problems such as the ones listed below;

Hedonic You want to try a different mobile phone, therefore you spend a great deal of time trying to buy the handset, but faced problems such as the ones listed below.